- National Technique Innovation Center for Regional Wheat Production, Key Laboratory of Crop Physiology and Ecology in Southern China, Ministry of Agriculture, National Engineering and Technology Center for Information Agriculture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China

Salicylic acid (SA) can induce plant resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses through cross talk with other signaling molecules, whereas the interaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and abscisic acid (ABA) in response to SA signal is far from clear. Here, we focused on the roles and interactions of H2O2 and ABA in SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat plants. Exogenous SA pretreatment significantly induced freezing tolerance of wheat via maintaining relatively higher dark-adapted maximum photosystem II quantum yield, electron transport rates, less cell membrane damage. Exogenous SA induced the accumulation of endogenous H2O2 and ABA. Endogenous H2O2 accumulation in the apoplast was triggered by both cell wall peroxidase and membrane-linked NADPH oxidase. The pharmacological study indicated that pretreatment with dimethylthiourea (H2O2 scavenger) completely abolished SA-induced freezing tolerance and ABA synthesis, while pretreatment with fluridone (ABA biosynthesis inhibitor) reduced H2O2 accumulation by inhibiting NADPH oxidase encoding genes expression and partially counteracted SA-induced freezing tolerance. These findings demonstrate that endogenous H2O2 and ABA signaling may form a positive feedback loop to mediate SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat.

Introduction

As one of the major food crops, wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) frequently suffers from freezing stress, especially during jointing stage. Freezing affects the development of the young spikelet, hibits plant growth, and grain yield formation (Kosova et al., 2013). To overcome freezing stress constraint, plants have developed highly sophisticated and intricate defense mechanisms to enhance stresses tolerance, which are largely dependent on the delicate signaling cascades network, activation of the reactive oxygen scavenging systems, accumulation of the compatible solutes or osmosis protectants, expression of the cold-responsive genes (Ruellan et al., 2009).

Salicylic acid (SA) is a naturally occurring phenolic compound and key signaling molecule that plays an essential role in the regulation of diverse physiological processes in plants (An and Mou, 2011; Yang et al., 2013). SA has been widely investigated for its crucial role in mediating plant responses to pathogen infection, such as inducing host cell death and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) (Yoshimoto et al., 2009; Kalachova et al., 2013). Apart from this role, SA has received much attention due to its role in plants response to abiotic stresses (e.g., drought, extreme temperature, heavy metal, and salinity) (Miura and Tada, 2014; Guo et al., 2016). Previous studies have shown that low temperature could induce endogenous SA accumulation in plants (Scott et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2014). Pretreated with SA biosynthesis inhibitors significantly down-regulated the expression of cold-responsive genes in cucumber (Dong et al., 2014), decreased the capacity of antioxidant in watermelon (Fei et al., 2016), resulting in a reduction in cold tolerance. These findings demonstrated that endogenous SA plays an important role in plant response to low temperature stress. Exogenous SA can enhance plant tolerance to cold stress, through increasing antioxidant capacity and polyamine content in maize (Janda et al., 1999; Nemeth et al., 2002), and apoplastic antifreeze protein accumulation in wheat (Tasgin et al., 2003). However, the mechanism of SA-induced tolerance mediated by signaling molecules in response to freezing stress remain to be investigated.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), is considered as a second messenger in phytohormone signalings and is involved in the regulation of plant responses to abiotic stresses (Xia et al., 2009; Maruta et al., 2012). It appears that SA-induced H2O2 is necessary for SAR during pathogen infection (Chen et al., 1993). Moreover, the self-amplifying feedback loop between SA and H2O2 indicated that there is a synergistic interaction to mediate plant cell death in atg (autophagy) mutant (Yoshimoto et al., 2009) or during pathogen infection (Vlot et al., 2009). Exogenous SA-induced H2O2 can be produced through several pathways, including increasing the activity of cell wall Prx (Mori et al., 2001) or membrane-linked NADPH oxidase (Agarwala et al., 2005), inhibiting the activity of CAT or APX (Kang et al., 2003). However, the pathway of SA-induced endogenous H2O2 production remains largely elusive in wheat.

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a central component in plants response to freezing stress (Lang et al., 1994; Akter et al., 2014). Both ABA and SA signal transduction pathways are activated by cold, which implies their involvement in cold stress responses in rice (Zhao et al., 2015). Moreover, Pal et al. (2011) found that SA participates in ABA-induced cold acclimation in maize. Furthermore, ABA also plays a predominant role in exogenous SA-induced tolerance to salt stress in tomato (Horvath et al., 2015) and cadmium toxicity in wheat (Shakirova et al., 2016). These findings suggest that endogenous ABA may be involved in SA-induced resistance to freezing stress in wheat plants.

H2O2 mediates ABA-induced plant stomatal closure and tolerance to heat stress (Zhang et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2014). Evidence shows that ABA-induced H2O2 accumulation may be involved in an early expression of diverse antioxidative genes, which contribute to cold stress tolerance (Xuexuan et al., 2010). Interestingly, H2O2 can work in coordination with nitric oxide, ABA and ethylene in response to cold (Thakur and Nayyar, 2013). Overall, feedback or feed-forward interactions may presumably occur between ABA and H2O2 in plants response to low temperature stress.

Therefore, further investigation of the relationship between ABA and H2O2 in the process of SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat is of interest. Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to (1) understand the effect of exogenous SA on freezing tolerance, (2) clarify the roles of H2O2 and ABA in SA-induced freezing tolerance, and (3) identify the interaction between H2O2 and ABA in SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

Uniform seeds of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv. Yangmai 16) were selected and surface-sterilized with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min and washed several times with sterile distilled water. Seeds were sown into vermiculite and maintained at temperatures of 22°C/18°C (day/night), and 12 h photoperiod with photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 400 μmol m−2 s−1. After 14 days of growth, seedlings were transplanted to a container (40 cm × 35 cm × 18 cm) filled with Hoagland nutrient solution and grown in a controlled environment (with day/night temperature at 22°C/18°C), and 12 h photoperiod under with PAR 400 μmol m−2 s−1. The solution was renewed daily and aerated over the whole experimental period.

To identify the optimal concentration of exogenous SA, 0, 10, 100, and 1000 μM SA were sprayed on wheat leaves at the four-leaf stage three times, with an interval of 12 h. Freezing stress was applied at 12 h after SA pretreatment, and plants were challenged with freezing at −2°C/400 μmol m−2 s−1 for 24 h. To investigate the source of endogenous H2O2 induced by SA, leaves were treated with 5 mM SHAM (an inhibitor of cell wall peroxidase) or 100 μM DPI (an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase) for 8 h before treated the plants with 100 μM SA. To evaluate the crosstalk between H2O2 and ABA in SA-induced freezing stress, leaves were pretreated with 2 mM DMTU (a H2O2 and OH• scavenger) or 1 μM Flu (an ABA synthesis inhibitor) for 8 h before the treatment of 100 μM SA. After 12 h of SA treatment, plants were treated with freezing as described above. The last fully expanded leaves were used for the following measurements.

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were detected using an imaging pulse amplitude modulated fluorometer (CF Imager, Technologica, United Kingdom). Seedlings were dark adapted for 30 min at least before taking images and measuring dark-adapted maximum photosystem II quantum yield (Fv/Fm) was determined with the entire leaf. The ETR were determined and calculated as actinic irradiance × the quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦPSII) × 0.84 × 0.5, where 0.5 is the supposed proportion of absorbed quanta used by PSII reaction centers, actinic irradiance is 500 μmol m−2 s−1, and 0.84 is the leaf absorbance for wheat leaves, respectively.

Electrolyte Leakage Measurement and ABA Quantification

Electrolyte leakage (EL) was tested according to Janda et al. (1999). ABA concentration was determined according to the indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method described by Liu et al. (2016).

Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Malondialdehyde Content

The extractions of antioxidant enzymes were conducted according to Xia et al. (2009) with some modification. Briefly, 0.5 g of leaf samples were ground using a mortar and pestle with 5 mL precooled 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM ascorbic acid, and 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatants were used for enzymatic activity analysis. SOD (EC 1.15.1.1) activity was determined as described by Patra et al. (1978). The activities of CAT (EC1.11.1.6) and APX (EC 1.11.1.11) were determined by the decrease in A240 and A290 as described by Xia et al. (2009), respectively. Soluble protein content was tested using the Bradford (1976) method. The content of Malondialdehyde (MDA), an indirect measurement of lipid peroxidation, was determined as described by Xia et al. (2009).

H2O2 Detection and Quantification

Cytochemical detection of H2O2 was described by Zhou et al. (2013) using CeCl3 for localization at the subcellular level. The electron-dense CeCl3 deposits that are formed in the presence of H2O2 are visible by transmission electron microscopy. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) detection of H2O2 was followed to the method of Xia et al. (2011) with minor modifications. Intact leaves with the sheath were immersed in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) containing 25 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) for 6 h at 30°C in a growth chamber without light. After staining, leaves pieces were washed by same buffer and thin sections were cut by hand. The sections were examined with a confocal microscopy using excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm (model TCS-SP2 CLSM; Leica Lasertechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). H2O2 was measured using assay kits from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China.

Cell Wall Peroxidase (Prx) Activity

Cell wall Prx (ionically bounded) was extracted as described by Lin and Kao (2001) with NaCl solution. The activity of cell wall Prx was determined by monitoring the changes in A470 due to the oxidation of guaiacol as described by Adam et al. (1995).

Total RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from leaves using RNAiso Plus (Takara, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Two micrograms of total RNA were used as the template for first strand cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sangon, Shanghai, China). The real time quantitative PCR was performed using gene-specific primers and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) with a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ5 fluorescence real time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). The primers for Prx103, Prx108, Rboh (respiratory burst oxidase homolog) D, RbohF, NCED (9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase) 1, NCED2, CS (cold-specific) 120, COR (cold-regulate) 14, CBF (c-repeat binding factor) 3, RAB (response to ABA) 17, RAB18, and ABI (ABA insensitive) 5 were listed in Supplementary Table 1. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated using the delta–delta Ct method (Wang et al., 2018) using ADP-RF (ADP-ribosylation factor) as the reference gene as described previously (Paolacci et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis

All the data are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used on the data sets and tested for significant (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) treatment differences using Duncan’s multiple range test (SigmaPlot 10.0; Systat Software).

Results

Effects of Exogenous SA on Freezing Tolerance of Wheat Plants

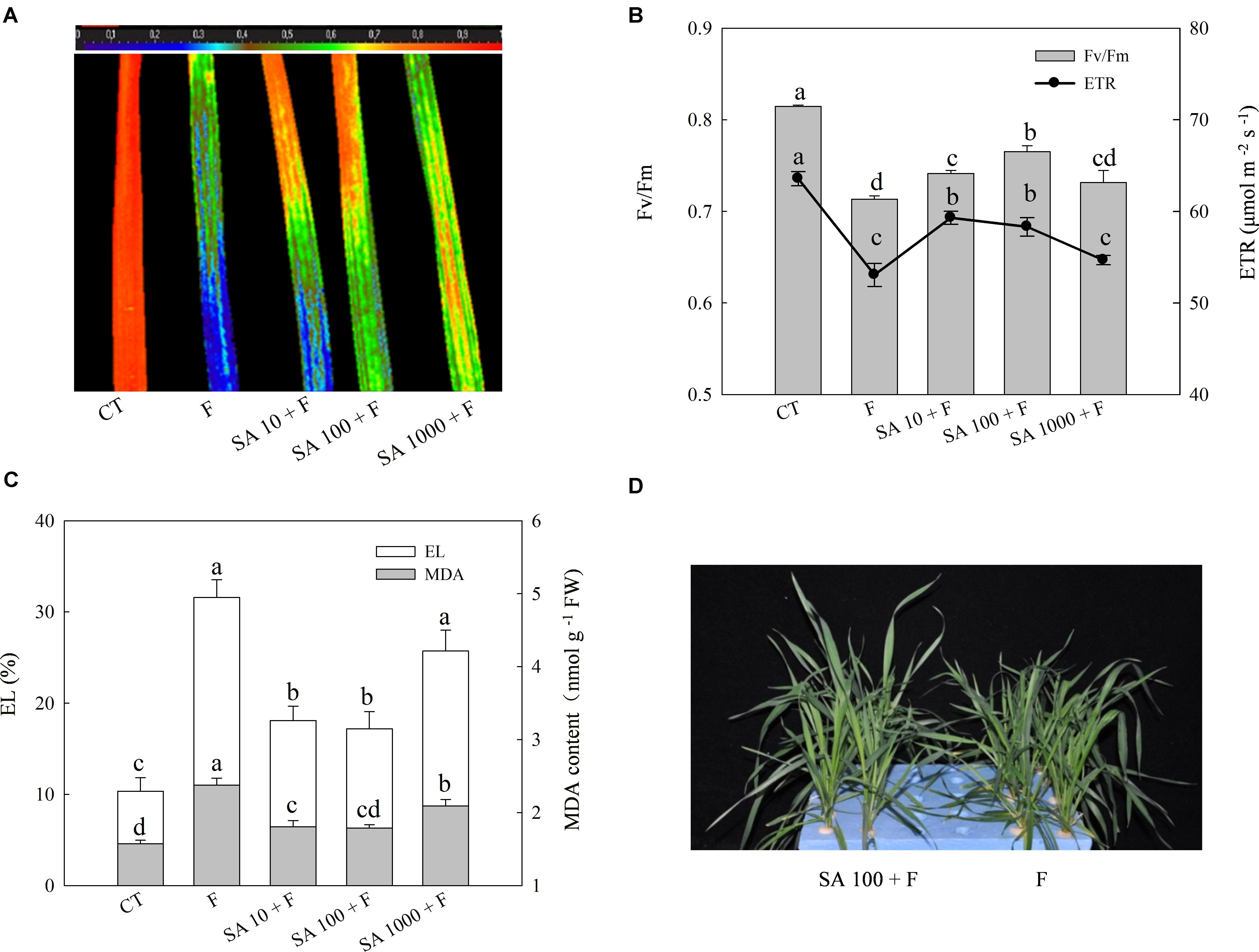

To evaluate the alleviation effects of exogenous SA on freezing tolerance, we sprayed the foliage of wheat plants with different concentrations of SA and then subjected the plants to freezing stress. The morphology, Fv/Fm, ETR, MDA content, and EL were used for evaluation of freezing tolerance. Freezing treatment resulted in prominent decrease of Fv/Fm and ETR, while SA pretreatment resulted in less reduction in Fv/Fm and ETR of wheat leaves resulted from freezing (Figures 1A,B). In addition, SA pretreatment effectively inhibited the increase of MDA content and EL following freezing (Figure 1C). We observed that 100 μM SA has a better alleviation effect on Fv/Fm reduction than other concentrations. After a few days freezing treatment, severe damage symptoms could be visually observed in water pretreatment plants, while those which were pretreated with 100 μM SA showed less severe symptoms than water pretreatment plants under freezing (Figure 1D). Therefore, 100 μM exogenous SA was chosen as the efficient concentration to enhance the capacity of freezing tolerance in wheat plants.

FIGURE 1. SA pretreatment improves freezing tolerance of wheat plants. (A) Image of the maximum PS II quantum yield (Fv/Fm). (B) The average value of Fv/Fm and electron transport rates (ETR). (C) Electrolyte leakage (EL) and MDA content. (D) The phenotype of wheat plants in response to water and SA (100 μM) under freezing stress. Plants treated with 0, 10, 100, and 1000 μM SA were challenged with freezing stress at –2°C for 1 day, and were denoted as F, SA10 + F, SA100 + F, SA1000 + F, respectively. CT indicates the control (no SA and no freezing stress). The color code depicted on the top of the image (A) ranges from 0 (blue) to 1.0 (red). Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

Exogenous SA Triggers H2O2 Accumulation in Leaves

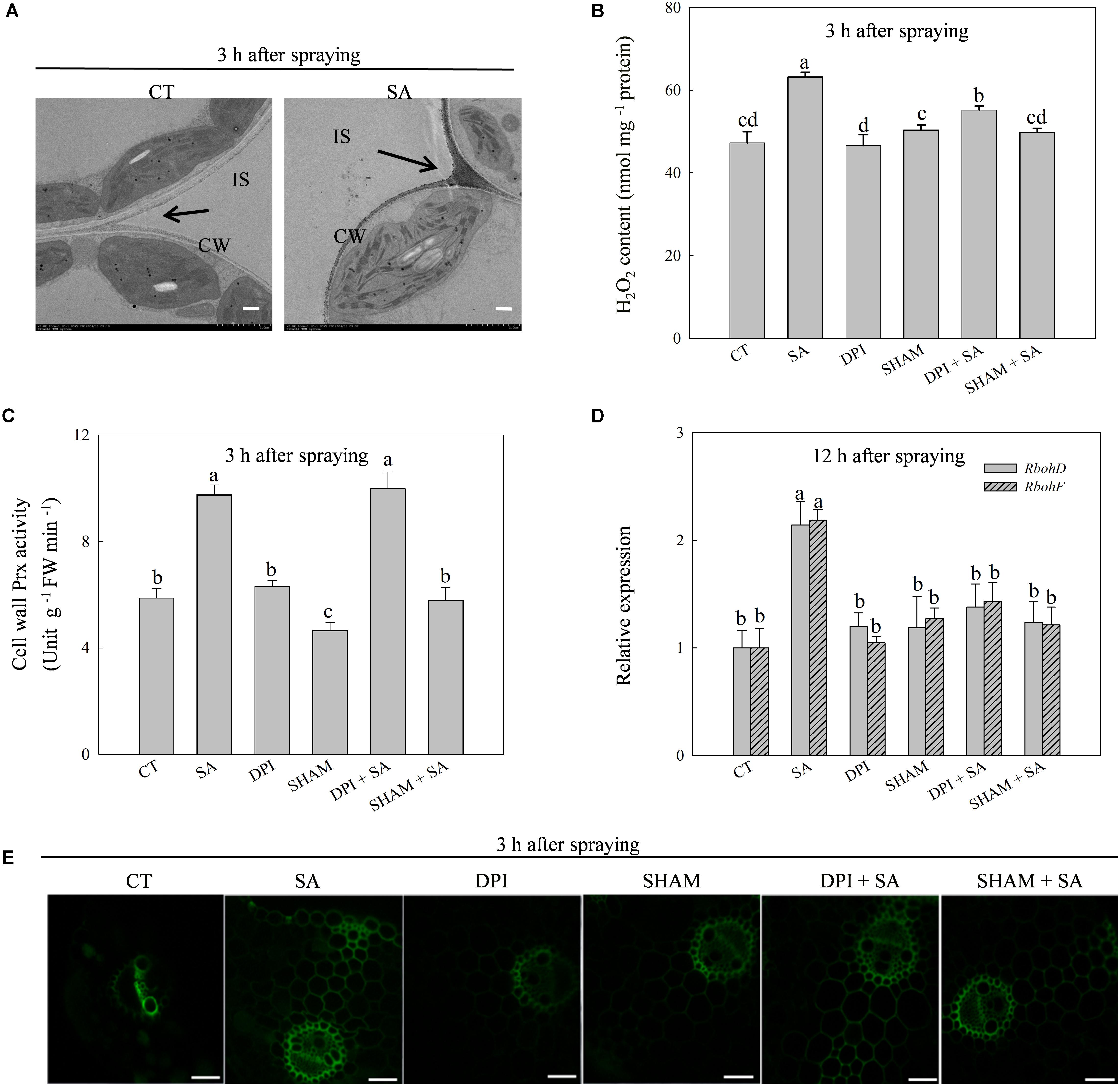

The production of H2O2 was triggered by exogenous SA and reached a peak at 3 h after SA treatment (Supplementary Figures 1A,B). The SA-induced H2O2 accumulated predominantly on the cell walls in the apoplast (Figure 2A). Exogenous SA significantly up-regulated the expression of Prx103 and Prx108, genes encoding cell wall Prx, which catalyzes the production of H2O2 in the apoplast, as well as the up-regulation of cell wall Prx activity (Supplementary Figure 2). The maximum cell wall Prx activity also appeared at 3 h after SA treatment. Expression of RbohD and RbohF, genes encoding membrane-linked NADPH oxidase, which also catalyzes the production of H2O2 in the apoplast, were induced by SA (Supplementary Figure 2). Significant differences in Rbohs expression between SA treated and control plants occurred at 12 h after SA treatment, which was much later than the expression of Prxs.

FIGURE 2. SA regulates H2O2 production in leaves of wheat plants. (A) Cytochemical localization of H2O2 in wheat leaves with CeCl3 staining and transmission electron microscopy. Arrows, CeCl3 precipitates; IS, intercellular space; CW, cell wall; Bars, 2 μm. The last fully expanded leaves were harvested at 3 h after water or 100 μM SA treatment. (B) Effects of DPI (diphenyleneiodonium, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase) and SHAM (salicylhydroxamic acid, an inhibitor of cell wall Prx) on SA-induced H2O2 production. (C) Effects of DPI on SA increased the activity of cell wall Prx. (D) Effects of SHAM on SA up-regulated expression of RbohD and RbohF. (E) Staining H2O2 with H2DCF-DA and detected by confocal laser scanning microscope system (CLSM). Bars, 200 μm. Plants pretreated with 100 μM DPI or 5 mM SHAM were treated with water or 100 μM SA. The last fully expanded leaves were used for the analysis of H2O2 content and cell wall Prx activity at 3 h, Rboh expression at 12 h after water or 100 μM SA treatment. Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

These results imply that SA-induced production of H2O2 originated from the cell wall Prx and then secondarily from membrane-linked NADPH oxidase. To verify this hypothesis, we pretreated leaves with SHAM (an inhibitor of cell wall Prx) or DPI (an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase) before SA treatment. As expected, DPI pretreatment did not affect SA-induced activation of cell wall Prx (Figure 2C), while SHAM and DPI pretreatments significantly down-regulated SA-induced expression of RbohD and RbohF (Figure 2D). In addition, DPI pretreatment only partially inhibited SA-induced H2O2 production, whereas SHAM pretreatment eliminated SA-induced H2O2 accumulation (Figure 2B). The results of H2O2 measuring by staining with H2CDFDA were consistent with the result of chemical assay (Figure 2E). These observations suggest that SA-induced extracellular H2O2 accumulation is initialed by cell wall Prx, and then by activating membrane-linked NADPH oxidase to produce more H2O2 in the apoplast.

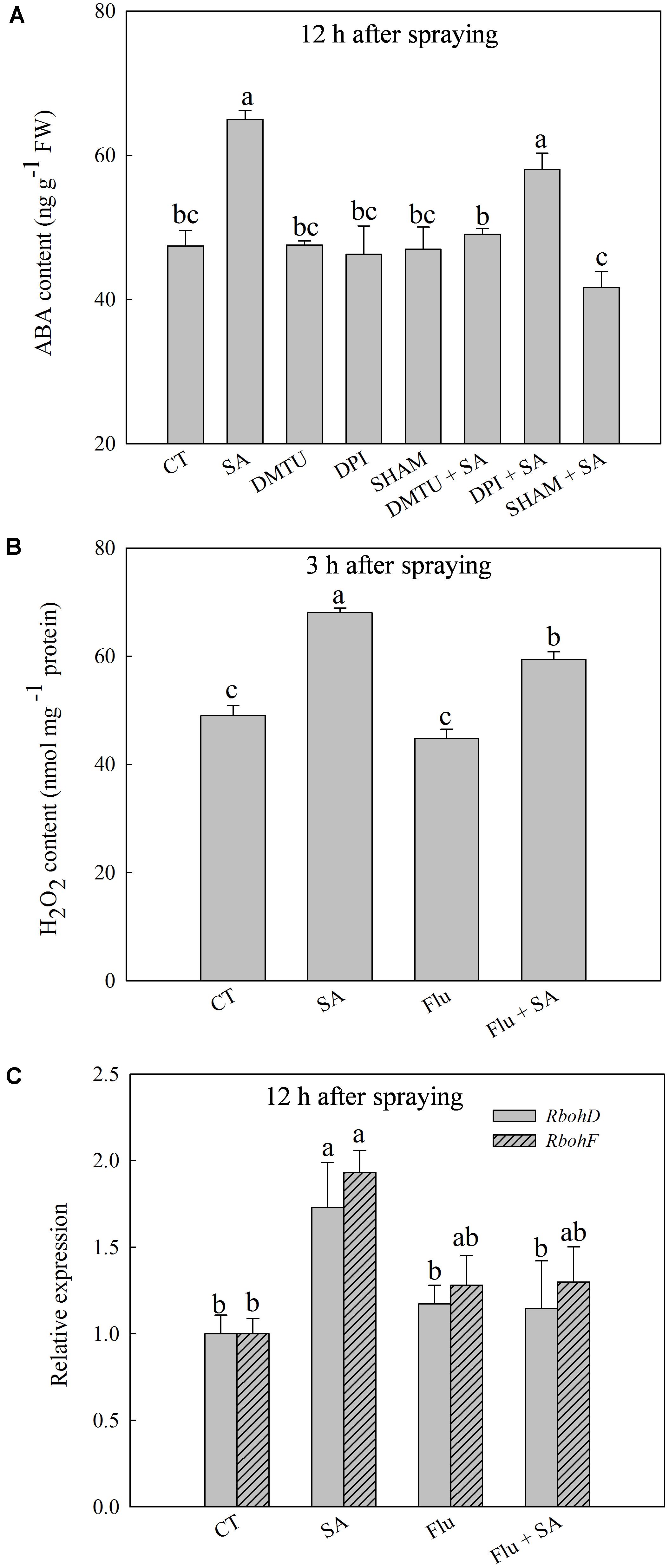

ABA Participates in SA-Induced H2O2 Production

Exogenous SA resulted in a significant increase of endogenous ABA content at 12 h after SA treatment (Supplementary Figure 1C), accompanied with the obviously up-regulated expression of NCED1 and NCED2 at 12 h after SA treatment (Supplementary Figure 1D). To explore the interactions of H2O2 and ABA in SA signal transduction, we analyzed the response of endogenous ABA or H2O2 to pretreatment with SHAM, DMTU (a H2O2 and OH• scavenger), DPI, or Flu (an ABA synthesis inhibitor) before SA application. SA-induced ABA accumulation was almost entirely blocked by SHAM or DMTU, while was only slightly inhibited by DPI (Figure 3A). Interestingly, Flu also obviously but partially inhibited SA-induced H2O2 accumulation (Figure 3B). In addition, Flu blocked SA-induced expression of RbohD and RbohF (Figure 3C). Basing on these observations, the H2O2 generated by cell wall Prx appears to act upstream of ABA in response to SA, while ABA could activate NADPH oxidase to release H2O2 in the apoplast.

FIGURE 3. The relationship between SA-induced H2O2 and ABA. (A) Effects of DMTU (dimethylthiourea, a scavenger of H2O2 and OH•), DPI or SHAM on SA-induced ABA accumulation. (B) Effects of Flu (fluorine, an inhibitor of ABA synthesis) on SA-induced H2O2 accumulation. (C) Effects of Flu on SA up-regulated expression of RbohD and RbohF. Plants pretreated with water, 2 mM DMTU, 100 μM DPI, or 5 mM SHAM were treated with water or 100 μM SA treatment. The last fully expanded leaves were collected for the analysis of H2O2 content at 3 h, ABA content and Rboh expression at 12 h after water or 100 μM SA treatments. Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

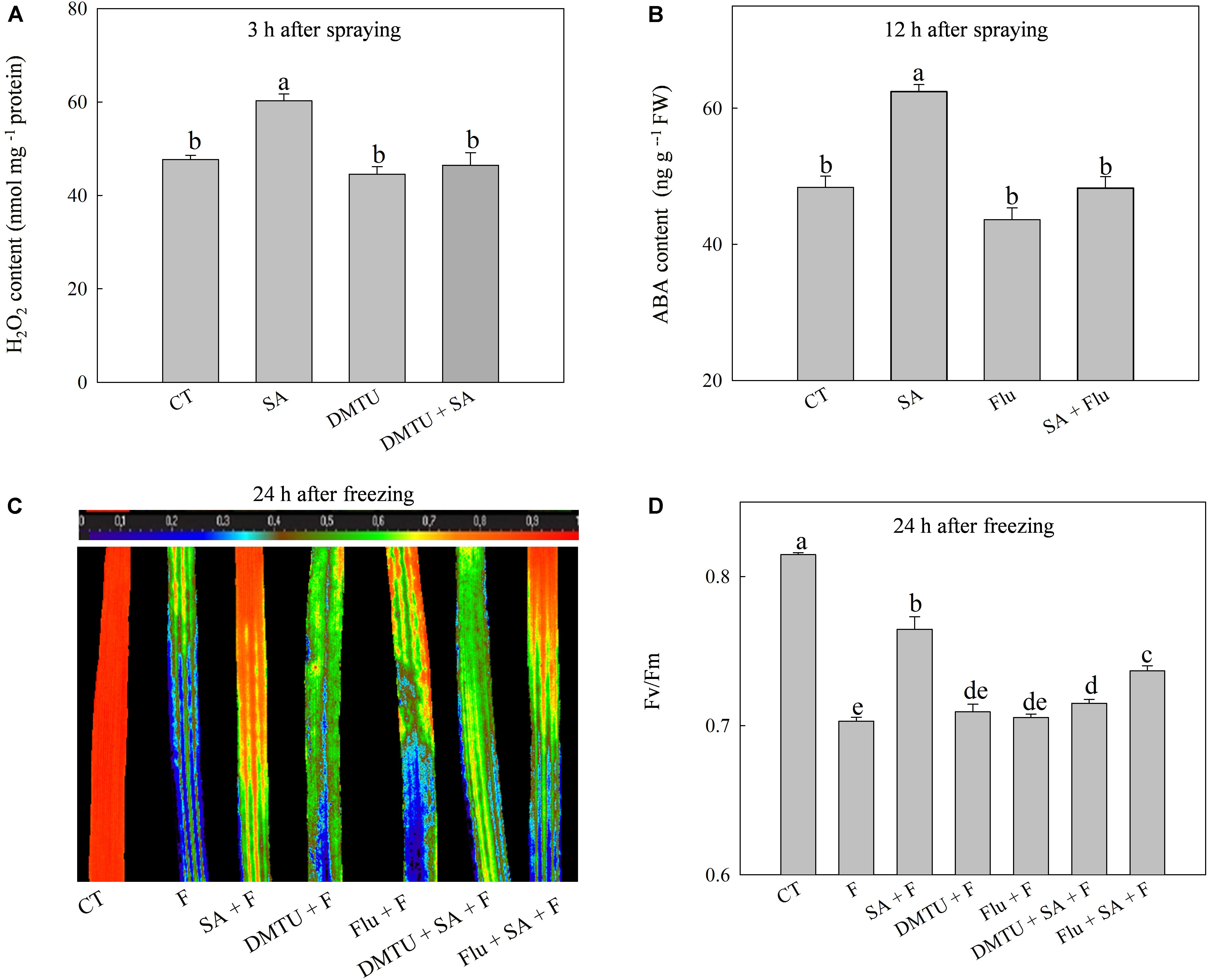

Endogenous H2O2 and ABA Play Different Roles in SA-Induced Freezing Tolerance

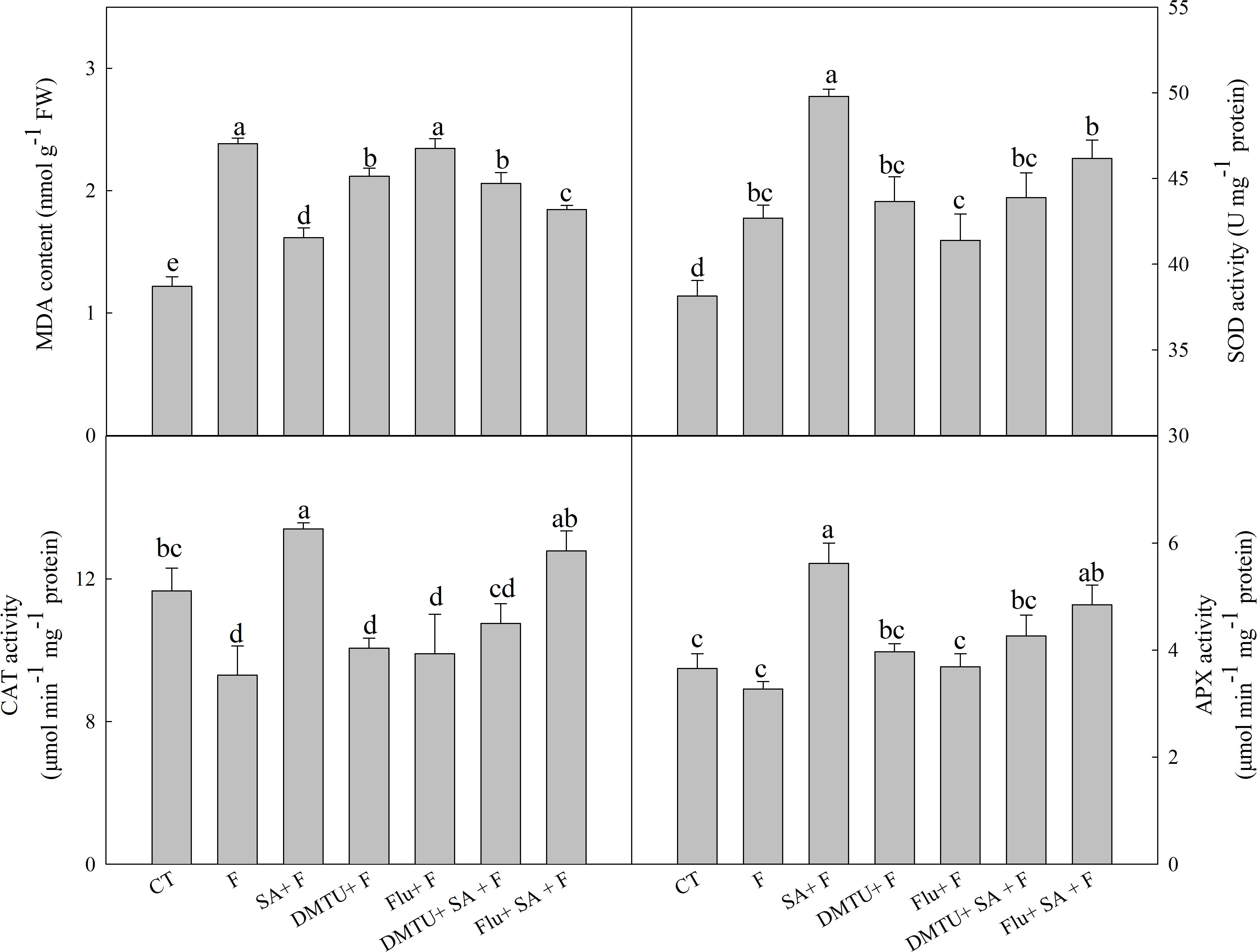

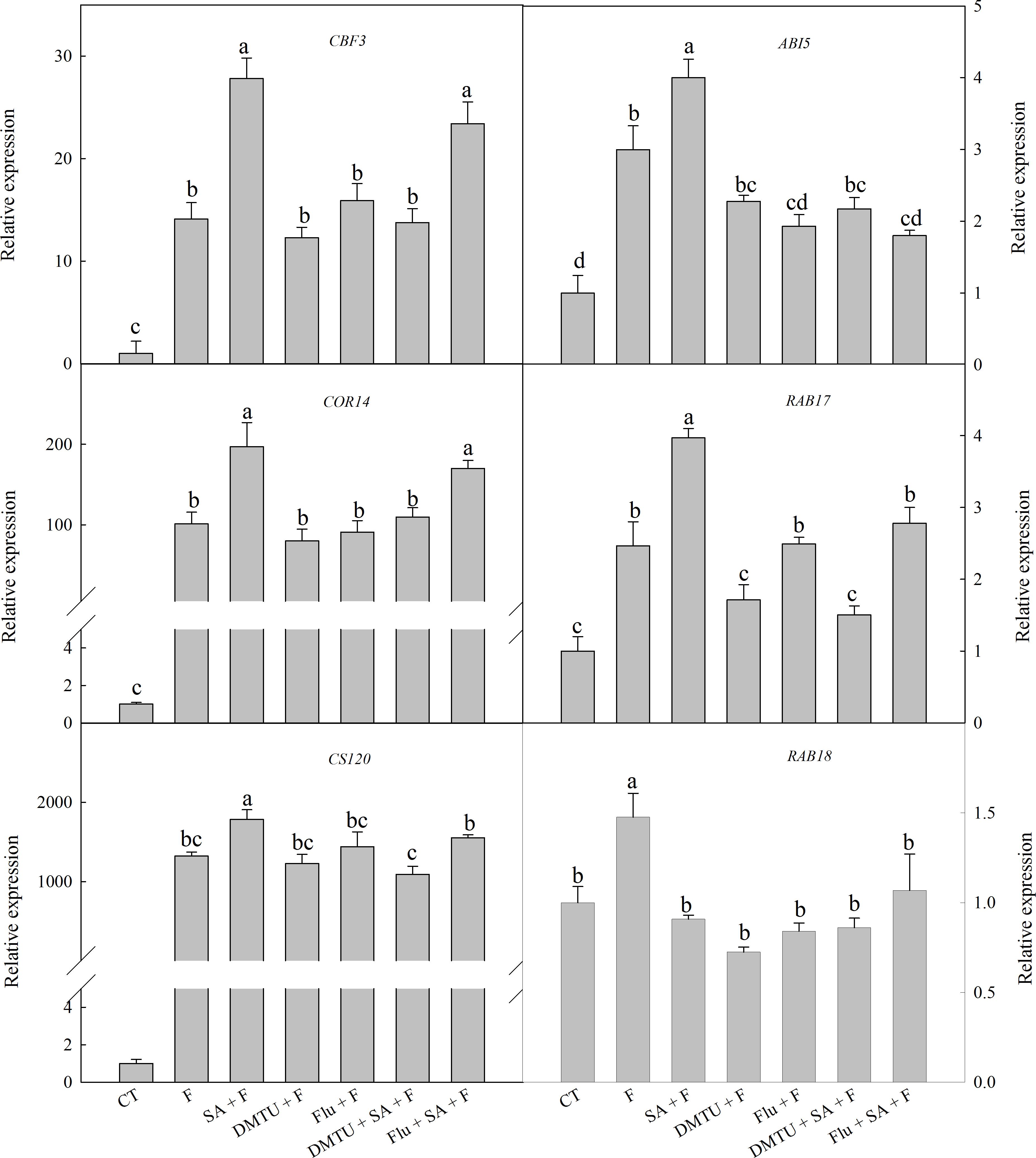

To confirm the functions of H2O2 and ABA in SA-induced wheat freezing tolerance, we investigated the effects of DMTU or Flu on freezing tolerance in wheat. DMTU and Flu pretreatments completely inhibited SA-induced accumulation of H2O2 and ABA, respectively (Figures 4A,B). However, the protective effect of exogenous SA was almost completely blocked by DMTU while only partially suppressed by Flu when plants were exposed to freezing (Figures 4C,D, 5). Likewise, DMTU substantially eliminated SA-induced activation of SOD, CAT, and APX and the expression of CBF3, COR14, CS120, ABI5, and RAB17 in freezing stressed plants (Figures 5, 6). However, Flu only slightly restrained the activation of SOD, CAT, and APX and the expression of CBF3, COR14, and CS120, but blocked the expression of ABI5 and RAB17 induced by SA in freezing stressed plants (Figures 5, 6). Exogenous application of ABA naturally alleviated the inhibition of PS II-induced by freezing while H2O2 showed no sign of this mitigative effect (Supplementary Figure 3). Collectively, these results demonstrate that both H2O2 and ABA are involved in SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat plants, and H2O2 may play an upstream role relative to ABA.

FIGURE 4. DMTU and Flu offset the SA-induced freezing tolerance. (A) Effects of DMTU on SA-induced H2O2 accumulation at 3 h after water or 100 μM SA treatment. (B) Effects of Flu on SA-induced ABA accumulation 12 h after water or 100 μM SA treatment. (C) Effects of DMTU or Flu on the images of Fv/Fm in SA treated plants under freezing stress. (D) Effects of DMTU or Flu on the average value of Fv/Fm in SA treated plants under freezing stress. Plants pretreated with water, 2 mM DMTU or 1 μM Flu were treated with water or 100 μM SA. After 12 h, the plants were challenged with freezing stress at –2°C for 1 day. Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

FIGURE 5. DMTU and Flu reduce the SA-induced increase of antioxidative capacity in wheat under freezing stress. Plants pretreated with water, 2 mM DMTU or 1 μM Flu were treated with water or 100 μM SA. After 12 h, the plants were challenged with freezing stress at –2°C for 1 day. Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

Discussion

SA Induces Freezing Stress Tolerance by Up-Regulating Antioxidant Capacity and Cold-Responsive Genes Expression in Wheat

Numerous researches have indicated that exogenous SA can enhance plant tolerance to freezing stress embodying maintenance of photosynthesis capacity, reduction of electrolyte leakage and MDA content (Janda et al., 1999; Fei et al., 2016). However, SA-induced stress tolerance could be plant growth stages, species and SA dose dependent (Fei et al., 2016). In this study, exogenous SA (at any concentrations of 10, 100, and 1000 μM) induced freezing tolerance by increasing Fv/Fm, decreasing electrolyte leakage and MDA content as compared to freezing only treatment in wheat (Figure 1), and 100 μM was the optimum concentration of those tested.

The antioxidant systems play crucial roles in reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging and show a positive correlation with plant freezing tolerance (Kang et al., 2013). Several studies illustrated that SA could enhance antioxidant capacity in various plant species, such as maize, rice, and cucumber (Kang and Saltveit, 2002). In this study, exogenous SA (100 μM) notably increased the activities of SOD, CAT, and APX, which was consistent with the lower MDA content in comparison with no pretreatment under freezing stress (Figure 5). The above results confirm that exogenous SA effectively relieves cell membrane damage induced by freezing at the level of antioxidant defense in wheat plants.

The accumulation of COR proteins are one of the critical mechanisms of the plant to cope with freezing stress (Kobayashi et al., 2008). COR14, CS120, RAB17, and RAB18 are typical of COR proteins (Ganeshan et al., 2008; Kobayashi et al., 2008). Induction of Cor genes by low temperature stress is regulated by CBF and ABA-responsive element binding protein (AREB) (Kobayashi et al., 2008). The activation of CBF genes expression is also ABA-dependent and ABA-independent (Zhou et al., 2011). Among the six selected genes in this study, the expression of CBF3, COR14, and CS120 are ABA-independent, while the expression of ABI5 (show highly homologous to AREB2), RAB17, and RAB18 are ABA-dependent (Houde et al., 1992; Tsvetanov et al., 2000; Kobayashi et al., 2008). In the present study, freezing dramatically up-regulated the expression of these cold-responsive genes, especially CBF3, COR14, and CS120, which were well accordance in with previous finding that CBF-COR pathway have a crucial role in constitutive freezing tolerance in plants (Chinnusamy et al., 2007). However, the effects of SA on these cold-responsive genes expression is still controversial. Miura and Ohta (2010) found that SA-accumulating mutant siz1 exhibits sensitivity to freezing, which is related to the down-regulated expression of CBF3. Nevertheless, PAC (paclobutrazol), a SA synthesis inhibitor, suppress the expression of CBF, COR47, and RAB18 in chilling stressed cucumber seedlings, and the decrement in the gene expression can be restored by exogenous SA (Dong et al., 2014). Most recently, Ding et al. (2016) found that exogenous SA up-regulated the expression of CBF1, which protect tomato fruit from chilling injury. In the present study, SA pretreatment significantly up-regulated the expression of CBF3, COR14, CS120, ABI5, and RAB17 (Figure 6), suggesting that SA enhanced wheat freezing tolerance by up-regulating the expression of both the ABA dependent and independent cold-responsive genes.

FIGURE 6. DMTU and Flu down-regulate the SA-induced expression of cold-responsive genes in wheat under freezing stress. Plants pretreated with water, 2 mM DMTU or 1 μM Flu were treated with water or 100 μM SA. After 12 h, the plants were challenged with freezing stress at –2°C for 1 day. Data are the means ± SD of three replicates. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are denoted by different lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

SA Triggers Extracellular H2O2 Production First Mediated by Cell Wall Prx and Further Magnified by the Membrane Linked NADPH Oxidase

There are three major pathways for the production of endogenous H2O2 under SA-induced abiotic and biotic stress tolerance. First, SA binds with CAT to suppress its activity, which leads to H2O2 accumulation (Chen et al., 1993; Kang et al., 2003). Second, SA activates membrane-linked NADPH oxidase mediating H2O2 production, which occurs in the apoplast (Kalachova et al., 2013). Third, SA induces extracellular H2O2 production via the SHAM-sensitive cell wall Prx (Mori et al., 2001; Khokon et al., 2011). However, the pathway of SA-induced endogenous H2O2 production in wheat remains unclear. In this study, SA-induced endogenous H2O2 accumulation was located on cell walls in the apoplast (Figure 2A). SA significantly enhanced cell wall Prx activity and up-regulated the expression of cell wall Prx and membrane-linked NADPH oxidase encoding genes (Supplementary Figure 2). Pretreated with SHAM (an inhibitor of cell wall Prx) and DPI (an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase) markedly reduced SA-induced H2O2 accumulation (Figures 2B,E). The above results suggest that both cell wall Prx and membrane-linked NADPH oxidase mediate SA-induced extracellular H2O2 accumulation in wheat. It should be noted that SHAM is also an inhibitor of the alternative oxidase (AOX), which is the terminal oxidase in the cyanide-resistant respiration pathway (Wei et al., 2015). The AOX pathway have an important role in decreasing the mitochondrial ROS level by reducing oxygen to water without conservation of energy in the form of ATP (Sugie et al., 2006). Here, SHAM treatment slightly increased the content of H2O2 as compared to water treatment (CT), indicating that SHAM may suppress the activity of AOX to induce ROS production (Figure 2B). However, pretreated with SHAM significantly decreased SA-induced H2O2 accumulation (Figure 2B). These findings reveal that SHAM reduced SA-induced H2O2 production by inhibiting cell wall Prx activity.

Recently, O’Brien et al. (2012) proposed that the cell wall Prx derived H2O2 production is the main source of ROS burst with the complementary sources of the NADPH oxidase-derived ROS production etc. In the present study, SA-induced H2O2 accumulation was completely blocked by SHAM and partially suppressed by DPI (Figures 2B,E). Pretreatment with DPI did not affect SA-induced cell wall Prx activity (Figure 2C), whereas SHAM completely blocked SA-induced expression of RbohD and RbohF (Figure 2D), indicating that SA-induced extracellular H2O2 production is first activated by cell wall Prx, and this original H2O2 further acted as a signal to activate NADPH oxidase to exaggerate the production of H2O2 in the apoplast.

The Crosstalk of Endogenous H2O2 and ABA in Response to SA

Several lines of evidences show that ABA induces apoplastic H2O2 production via NADPH oxidase to result in plant tolerance to heat and oxidation stress (Zhou et al., 2014). Exogenous brassinosteroids (BRs) induced ABA synthesis in wild type plants, but failed in the RBOH1-silenced mutants, demonstrating that H2O2 is pivotal in BRs-induced ABA biosynthesis (Zhou et al., 2014). Previous findings hint that there is a cross talk between H2O2 and ABA signals in response to external stresses and hormones. Here, pretreatment with SHAM and DMTU eliminated SA-induced accumulation of ABA (Figure 3A), indicating that H2O2 originated from the cell wall Prx can serve as a signal to mediate SA-induced ABA accumulation. However, DPI pretreatment had very little impact on SA-induced ABA synthesis (Figure 3A). Furthermore, inhibiting ABA synthesis by Flu markedly down-regulated SA-induced expression of RbohF and RbohD and the accumulation of H2O2 (Figures 3B,C). Thus, ABA signal can mediate SA-induced H2O2 originated from the membrane-linked NADPH oxidase. These results suggest that SA-induced ABA accumulation is dependent on the burst of H2O2 generated by cell wall Prx, and the induced ABA causes a further increase in H2O2 production in the apoplast by activating NADPH oxidase.

H2O2 and ABA Mediate SA-Induced Freezing Tolerance

The relationship between SA and H2O2 in plants response to biotic and abiotic stress is still not fully understood. An increasing body of evidence supports that SA can work in concert with H2O2 to mediate plant senescence, chilling tolerance and SAR (Kang et al., 2003; Vlot et al., 2009; Yoshimoto et al., 2009), whereas the others reported that SA-induced abiotic or biotic stress tolerance are H2O2 independent (Bi et al., 1995; Mora-Herrera et al., 2005). In this study, SA-induced freezing tolerance was accompanied with elevated H2O2 content (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figures 1A,B), and scavenging H2O2 by DMTU (DMTU + SA + F) eliminated SA-induced freezing tolerance as demonstrated by insignificant differences in Fv/Fm and activities of the antioxidant enzymes (Figures 4A,C,D, 5) and expression of cold-responsive genes as compared to SA pretreatment alone (SA + F, Figure 6). These results highlight the crucial role of H2O2 in SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat plants. Our results consistent with previous studies reported that apoplast ROS has an important role in mediating long-distance systemic signaling in plants in response to diverse environmental stimuli (Miller et al., 2009), and apoplast H2O2 can act as signal molecules in the activation of stress responses and induction of cold tolerance in cucumber (Xia et al., 2009) and freezing tolerance in wheat (Si et al., 2017). Exogenous H2O2 also has been shown to induce plants cold tolerance by up-regulating the activities of antioxidant enzymes and expression of cold responsive genes (Xia et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017). However, the findings of our study showed that pretreated with exogenous H2O2 had no alleviative effect on the inhibition of PS II caused by freezing stress. The contradiction between the previous and our results may be due to the different concentrations of applied H2O2 and temperatures of setting used in experiments (Xu et al., 2011; Si et al., 2017). Together, we suggested that exogenous SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat is mediated by apoplast H2O2, which derives first from the cell wall Prx and then from the NADPH oxidase.

Salicylic acid-induced plant stress tolerance has been considered to be mediated by endogenous ABA signal (Szepesia et al., 2009; Jesus et al., 2015). Exogenous SA induces ABA accumulation by up-regulating of ABA biosynthesis related genes (Horvath et al., 2015). Recently, Shakirova et al. (2016) found that endogenous ABA plays a key role in SA-induced cadmium stress tolerance in wheat. In this study, exogenous SA treatment resulted in significantly higher ABA content (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 1C), by up-regulating the expression of NCED1 and NCED2, key genes involving in ABA synthesis (Supplementary Figure 1D). Moreover, the ABA biosynthesis inhibitor Flu (Flu + SA + F) prominently reduced the alleviation effect of SA on freezing tolerance as indicted by the less significant difference in Fv/Fm, antioxidant enzymes activities (Figures 4B–D, 5) and the insignificant difference in the expression of ABA-responsive genes, such as ABI5 and RAB17 (Figure 6), as compared with SA + F. In addition, pretreatment with exogenous ABA showed lower inhibition of PS II under freezing than no pretreatment (Supplementary Figure 3), which in accordance with previous findings that exogenous ABA can effectively enhanced plants tolerance to freezing (Janowiak et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2017). Collectively, these results supported that the involvement of ABA in SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat plants, and H2O2 may play an upstream role relative to ABA.

Conclusion

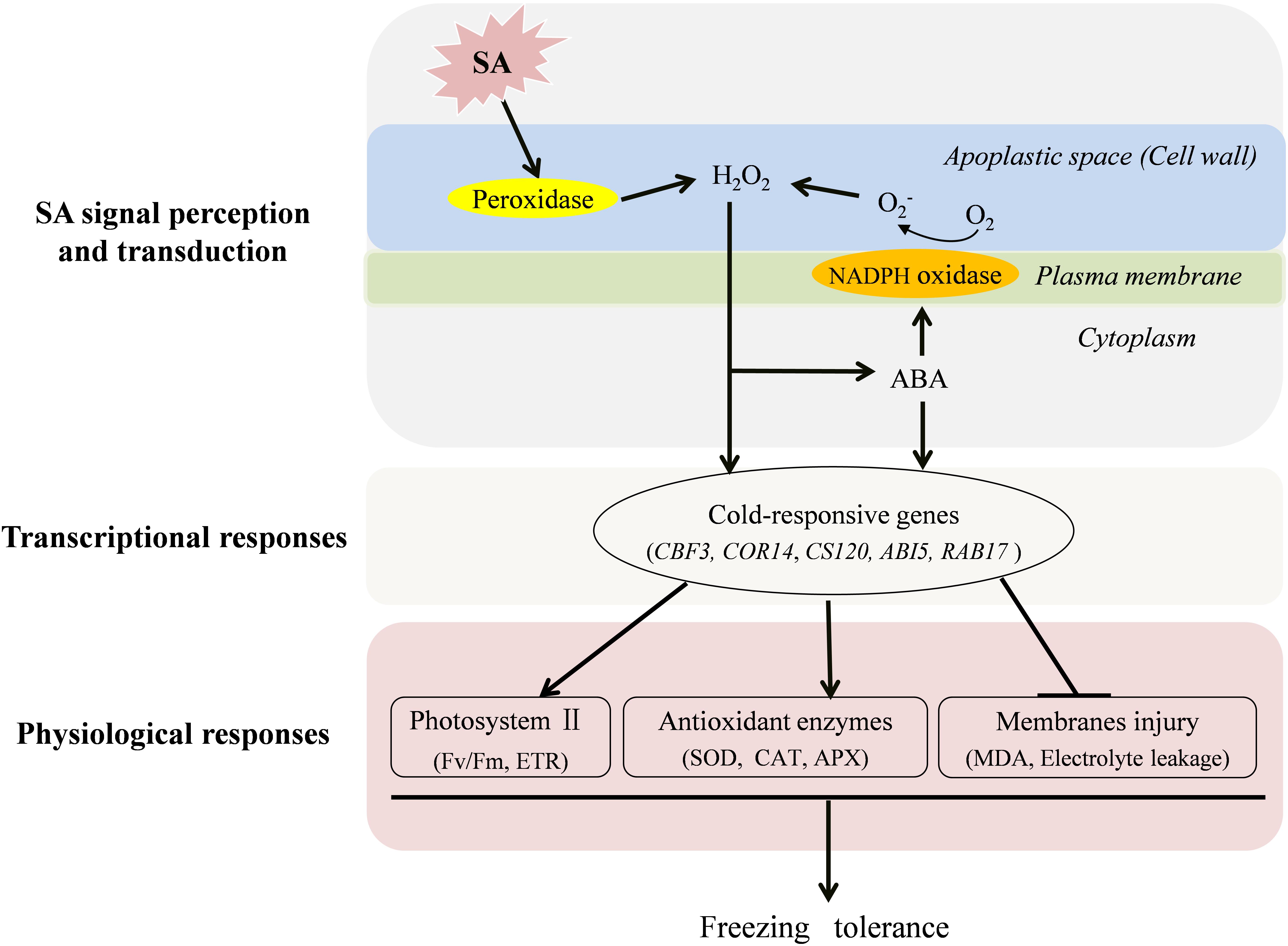

As concluded in Figure 7, both endogenous H2O2 and ABA play important roles in SA-induced freezing tolerance. Following the perception of a SA signal, cell wall Prx is activated to produce H2O2 in the apoplast. The increased H2O2 triggers ABA production, which in turn give rise to a further accumulation of H2O2 by activating NADPH oxidase leading to prolonged stress tolerance. Therefore, H2O2 and ABA may form a positive feedback loop to mediate SA-induced freezing tolerance in wheat plants. Finally, the increased H2O2 and ABA separately trigger their defense pathways to up-regulate expression of cold-responsive genes and activities of antioxidant enzymes to reduce the electrolyte leakage and cell membrane peroxidation and ultimately improve photosynthesis capacity (Fv/Fm and ETR) of wheat under freezing stress.

FIGURE 7. A conclusive model for the induction of freezing tolerance by exogenous SA in wheat plants. SA activates cell wall Prx to produce H2O2 in the apoplast, which functions as a signal molecule to induce the increase of antioxidative capacity, to trigger the expression of cold-responsive genes and ABA synthesis. The increased ABA further activates NADPH oxidase, which could induce more production H2O2 in the apoplast. In addition, ABA signal also plays a role in SA-induced antioxidant capacity, and expression of cold-responsive genes in wheat plants under freezing stress.

Author Contributions

WW, XW, and DJ conceived and designed the research. WW and MH conducted the experiments. JC, QZ, TD, and WC guided the experiments. WW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0300107), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31325020, 31401326, 31471445, and 31771693), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-03), Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production (JCIC-MCP), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01137/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ABA, abscisic acid; APX, ascorbate peroxidase; CAT, catalase; DMTU, dimethylthiourea; DPI, diphenyleneiodonium; ETR, electron transport rates; Flu, fluridone; Fv/Fm, maximum PS II quantum yield; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MDA, malondialdehyde; SA, salicylic acid; SHAM, salicylhydroxamic acid; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

References

Adam, A. L., Bestwick, C. S., Barna, B., and Mansfield, J. W. (1995). Enzymes regulating the accumulation of active oxygen species during the hypersensitive reaction of bean to Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Planta 197, 240–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00202643

Agarwala, S., Sairama, R. K., Srivastavaa, G. C., Tyagib, A., and Meena, R. C. (2005). Role of ABA, salicylic acid, calcium and hydrogen peroxide on antioxidant enzymes induction in wheat seedlings. Plant Sci. 169, 559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.05.004

Akter, K., Kato, M., Sato, Y., Kaneko, Y., and Takezawa, D. (2014). Abscisic acid-induced rearrangement of intracellular structures associated with freezing and desiccation stress tolerance in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 1334–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.05.004

An, C., and Mou, Z. (2011). Salicylic acid and its function in plant immunity. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 412–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01043.x

Bi, Y. M., Kenton, P., Mur, L., Darby, R., and Draper, J. (1995). Hydrogen peroxide does not function downstream of salicylic acid in the induction of PR protein expression. Plant J. 8, 235–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08020235.x

Bradford, M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Chen, Z., Silva, H., and Klessig, D. F. (1993). Active oxygen species in the induction of plant systemic acquired resistance by salicylic acid. Science 262, 1883–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.8266079

Chinnusamy, V., Zhu, J., and Zhu, J. K. (2007). Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.07.002

Ding, Y., Zhao, J., Nie, Y., Fan, B., Wu, S., Zhang, Y., et al. (2016). Salicylic acid-induced chilling- and oxidative-stress tolerance in relation to gibberellin homeostasis, CBF pathway, and antioxidant enzyme systems in cold-stored tomato fruit. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 64, 8200–8206. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b02902

Dong, C. J., Li, L., Shang, Q. M., Liu, X. Y., and Zhang, Z. G. (2014). Endogenous salicylic acid accumulation is required for chilling tolerance in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedlings. Planta 240, 687–700. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2115-1

Fei, C., Lu, J., Min, G., Kai, S., Kong, Q., Yuan, H., et al. (2016). Redox signaling and CBF-responsive pathway are involved in salicylic acid-improved photosynthesis and growth under chilling stress in watermelon. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1519. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01519

Ganeshan, S., Vitamvas, P., Fowler, D. B., and Chibbar, R. N. (2008). Quantitative expression analysis of selected COR genes reveals their differential expression in leaf and crown tissues of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) during an extended low temperature acclimation regimen. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2393–2402. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern112

Guo, B., Liu, C., Li, H., Yi, K., Ding, N., Li, N., et al. (2016). Endogenous salicylic acid is required for promoting cadmium tolerance of Arabidopsis by modulating glutathione metabolisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 316, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.05.032

Horvath, E., Csiszar, J., Gallw, A., Poor, P., Szepesi, A., and Tari, I. (2015). Hardening with salicylic acid induces concentration-dependent changes in abscisic acid biosynthesis of tomato under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 183, 54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.05.010

Houde, M., Danyluk, J., Laliberté, J. F., Rassart, E., Dhindsa, R. S., and Sarhan, F. (1992). Cloning, characterization, and expression of a cDNA encoding a 50-kilodalton protein specifically induced by cold acclimation in wheat. Plant Physiol. 99, 1381–1387. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1381

Huang, X., Shi, H., Hu, Z., Liu, A., Amombo, E., Chen, L., et al. (2017). ABA is involved in regulation of cold stress response in bermudagrass. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1613. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01613

Janda, T., Szalai, G., Tari, I., and Paaldi, E. (1999). Hydroponic treatment with salicylic acid decreases the effects of chilling injury in maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Planta 208, 175–180. doi: 10.1007/s004250050547

Janowiak, F., Maas, B., and Dörffling, K. (2002). Importance of abscisic acid for chilling tolerance of maize seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 159, 635–643. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-0638

Jesus, C., Meijon, M., Monteiro, P., Correia, B., Amaral, J., Escandon, M., et al. (2015). Salicylic acid application modulates physiological and hormonal changes in Eucalyptus globulus under water deficit. Environ. Exp. Bot. 118, 56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.06.004

Kalachova, T., Iakovenko, O., Kretinin, S., and Kravets, V. (2013). Involvement of phospholipase D and NADPH-oxidase in salicylic acid signaling cascade. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 66, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.02.006

Kang, G., Wang, C., Sun, G., and Wang, Z. (2003). Salicylic acid changes activities of H2O2-metabolizing enzymes and increases the chilling tolerance of banana seedlings. Environ. Exp. Bot. 50, 9–15. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00109-0

Kang, G. Z., Li, G. Z., Lu, G. Q., Xu, W., Peng, X. Q., Wang, C. Y., et al. (2013). Exogenous salicylic acid enhances wheat drought tolerance by influence on the expression of genes related to ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Biol. Plant. 57, 718–724. doi: 10.1007/s10535-013-0335-z

Kang, H. M., and Saltveit, M. E. (2002). Chilling tolerance of maize, cucumber and rice seedling leaves and roots are differentially affected by salicylic acid. Physiol. Plant. 115, 571–576. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150411.x

Khokon, M. A. R., Okuma, E., Hossain, M. A., Munemasa, S., Uraji, M., Nakamura, Y., et al. (2011). Involvement of extracellular oxidative burst in salicylic acid-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 434–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02253.x

Kobayashi, F., Maeta, E., Terashima, A., and Takumi, S. (2008). Positive role of a wheat HvABI5 ortholog in abiotic stress response of seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 134, 74–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01107.x

Kosova, K., Vítamvas, P., Planchon, S., Renaut, J., Vankova, R., and Prasil, I. T. (2013). Proteome analysis of cold response in spring and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) crowns reveals similarities in stress adaptation and differences in regulatory processes between the growth habits. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4830–4845. doi: 10.1021/pr400600g

Lang, V., Mantyla, E., Welin, B., Sundberg, B., and Palva, E. T. (1994). Alterations in water status, endogenous abscisic acid content, and expression of rab18 gene during the development of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 104, 1341–1349. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1341

Li, Z., Xu, J., Gao, Y., Wang, C., Guo, G., Luo, Y., et al. (2017). The synergistic priming effect of exogenous salicylic acid and H2O2 on chilling tolerance enhancement during Maize (Zea mays L.) seed germination. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1153. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01153

Lin, C. C., and Kao, C. H. (2001). Cell wall Prx activity, hydrogen peroxide level and NaCl-inhibited root growth of rice seedlings. Plant Soil 230, 135–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1004876712476

Liu, Y., Sun, J., Tian, Z., Hakeem, A., Wang, F., Jiang, D., et al. (2016). Physiological responses of wheat ( Triticum aestivum L.) germination to elevated ammonium concentrations: reserve mobilization, sugar utilization, and antioxidant metabolism. Plant Growth Regul. 81, 1–12.

Maruta, T., Noshi, M., Tanouchi, A., Tamoi, M., Yabuta, Y., Yoshimura, K., et al. (2012). H2O2-triggered retrograde signaling from chloroplasts to nucleus plays specific role in response to stress. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11717–11729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.292847

Miller, G., Schlauch, K., Tam, R., Cortes, D., Torres, M. A., Shulaev, V., et al. (2009). The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD mediates rapid systemic signaling in response to diverse stimuli. Sci. Signal. 2, 45–56. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000448

Miura, K., and Ohta, M. (2010). SIZ1, a small ubiquitin-related modifier ligase, controls cold signaling through regulation of salicylic acid accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.11.003

Miura, K., and Tada, Y. (2014). Regulation of water, salinity, and cold stress responses by salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 5:4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00004

Mora-Herrera, M. E., Lopez-Delgadoa, H., Castillo-Moralesc, A., and Foyer, C. H. (2005). Salicylic acid and H2O2 function by independent pathways in the induction of freezing tolerance in potato. Physiol. Plant. 125, 430–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00572.x

Mori, I., PInontoan, R., Kawano, T., and Muto, S. (2001). Involvement of superoxide generation in salicylic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 1383–1388. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce176

Nemeth, M., Janda, T., Horvath, E., Paldi, E., and Szalai, G. (2002). Exogenous salicylic acid increases polyamine content but may decrease drought tolerance in maize. Plant Sci. 162, 569–574. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00593-3

O’Brien, J. A., Daudi, A., Butt, V. S., and Bolwell, G. P. (2012). Reactive oxygen species and their role in plant defence and cell wall metabolism. Planta 236, 765–779. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1696-9

Pal, M., Janda, T., and Szalai, G. (2011). Abscisic acid may alter the salicylic acid-related abiotic stress response in maize. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 197, 368–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2011.00474.x

Paolacci, A. R., Tanzarella, O. A., Porceddu, E., and Ciaffi, M. (2009). Identification and validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR normalization in wheat. BMC Mol. Biol. 10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-11

Patra, H. K., Kar, M., and Mishra, D. (1978). Catalase activity in leaves and cotyledons during plant development and senescence. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 172, 385–390. doi: 10.1016/S0015-3796(17)30412-2

Ruellan, E., Vaultier, M., Zachowski, A., and Hurry, V. (2009). Cold signalling and cold acclimation in plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 49, 35–150. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)00602-2

Scott, I. M., Clarke, S. M., Wood, J. E., and Mur, L. A. J. (2004). Salicylate accumulation inhibits growth at chilling temperature in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 1040–1049. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.041293

Shakirova, F. M., Allagulova, C. R., Maslennikova, D. R., Klyuchnikova, E. O., Avalbaev, A. M., and Bezrukova, M. V. (2016). Salicylic acid-induced protection against cadmium toxicity in wheat plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 122, 19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.08.002

Si, T., Wang, X., Wu, L., Zhao, C., Zhang, L., Huang, M., et al. (2017). Nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide mediate wounding-induced freezing tolerance through modifications in photosystem and antioxidant system in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1284. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01284

Sugie, A., Naydenov, N., Mizuno, N., Nakamura, C., and Takumi, A. S. (2006). Overexpression of wheat alternative oxidase gene Waox1a alters respiration capacity and response to reactive oxygen species under low temperature in transgenic Arabidopsis. Genes Genet. Syst. 81, 349–354. doi: 10.1266/ggs.81.349

Szepesia, A., Csiszara, J., Gemesa, K., Horvatha, E., Horvatha, F., Simonb, M. L., et al. (2009). Salicylic acid improves acclimation to salt stress by stimulating abscisic aldehyde oxidase activity and abscisic acid accumulation, and increases Na+ content in leaves without toxicity symptoms in Solanum lycopersicum L. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 914–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.11.012

Tasgin, E., Atici, O., and Nalbantoglu, B. (2003). Effects of salicylic acid and cold on freezing tolerance in winter wheat leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 41, 231–236. doi: 10.1023/B:GROW.0000007504.41476.c2

Thakur, P., and Nayyar, H. (2013). Facing the Cold Stress by Plants in the Changing Environment: Sensing, Signaling, and Defending Mechanisms. New York, NY: Springer.

Tsvetanov, S., Ohno, R., Tsuda, K., Takumi, S., Mori, N., Atanassov, A., et al. (2000). A cold-responsive wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) gene wcor14 identified in a winter-hardy cultivar ‘Mironovska 808’. Genes Genet. Syst. 75, 49–57. doi: 10.1266/ggs.75.49

Vlot, A. C., Dempsey, M. A., and Klessig, D. F. (2009). Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 177–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202

Wang, X., Zhang, X., Chen, J., Cai, J., Zhou, Q., Dai, T., et al. (2018). Parental drought-priming enhances tolerance to post-anthesis drought in offspring of wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 9:261. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00261

Wei, L. J., Deng, X. G., Zhu, T., Zheng, T., Li, P. X., Wu, J. Q., et al. (2015). Ethylene is involved in brassinosteroids induced alternative respiratory pathway in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedlings response to abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci 6:982. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00982

Xia, X.-J., Wang, Y.-J., Zhou, Y.-H., Tao, Y., Mao, W.-H., Shi, K., et al. (2009). Reactive oxygen species are involved in brassinosteroid-induced stress tolerance in cucumber. Plant Physiol. 150, 801–814. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138230

Xia, X.-J., Zhou, Y.-H., Ding, J., Shi, K., Asami, T., Chen, Z., et al. (2011). Induction of systemic stress tolerance by brassinosteroid in Cucumis sativus. New Phytol. 191, 706–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03745.x

Xu, F. J., Jin, C. W., Liu, W. J., Zhang, Y. S., and Li, X. Y. (2011). Pretreatment with H2O2 alleviates aluminum-induced oxidative stress in wheat seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01008.x

Xuexuan, X., Hongbo, S., Yuanyuan, M., Gang, X., Junna, S., Donggang, G., et al. (2010). Biotechnological implications from abscisic acid (ABA) roles in cold stress and leaf senescence as an important signal for improving plant sustainable survival under abiotic-stressed conditions. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 30, 222–230. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2010.487186

Yang, W., Zhu, C., Ma, X., Li, G., Gan, L., Ng, D., et al. (2013). Hydrogen peroxide is a second messenger in the salicylic acid-triggered adventitious rooting process in mung bean seedlings. PLoS One 8:e84580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084580

Yoshimoto, K., Jikumaru, Y., Kamiya, Y., Kusano, M., Consonni, C., Panstruga, R., et al. (2009). Autophagy negatively regulates cell death by controlling NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling during senescence and the innate immune response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 2914–2927. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068635

Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Dong, F., Gao, J., Galbraith, D. W., and Song, C. P. (2001). Hydrogen peroxide is involved in abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol. 126, 1438–1448. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1438

Zhao, J., Zhang, S., Yang, T., Zeng, Z., Huang, Z., Liu, Q., et al. (2015). Global transcriptional profiling of a cold-tolerant rice variety under moderate cold stress reveals different cold stress response mechanisms. Physiol. Plant. 154, 381–394. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12291

Zhou, J., Wang, J., Li, X., Xia, X.-J., Zhou, Y.-H., Shi, K., et al. (2014). H2O2 mediates the crosstalk of brassinosteroid and abscisic acid in tomato responses to heat and oxidative stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4371–4383. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru217

Zhou, J., Wang, J., Shi, K., Xia, X. J., Zhou, Y. H., and Yu, J. Q. (2013). Hydrogen peroxide is involved in the cold acclimation-induced chilling tolerance of tomato plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 60, 141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.07.010

Keywords: endogenous signal, freezing tolerance, inhibitor, salicylic acid, wheat

Citation: Wang W, Wang X, Huang M, Cai J, Zhou Q, Dai T, Cao W and Jiang D (2018) Hydrogen Peroxide and Abscisic Acid Mediate Salicylic Acid-Induced Freezing Tolerance in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1137. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01137

Received: 15 May 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018;

Published: 03 August 2018.

Edited by:

Rudy Dolferus, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), AustraliaReviewed by:

Axel De Zelicourt, Université Paris-Sud, FranceTeruaki Taji, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Japan

Copyright © 2018 Wang, Wang, Huang, Cai, Zhou, Dai, Cao and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao Wang, eGlhb3dhbmdAbmphdS5lZHUuY24=; Dong Jiang, amlhbmdkQG5qYXUuZWR1LmNu

Weiling Wang

Weiling Wang Xiao Wang

Xiao Wang Mei Huang

Mei Huang Jian Cai

Jian Cai Qin Zhou

Qin Zhou Tingbo Dai

Tingbo Dai Dong Jiang

Dong Jiang