94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Plant Sci., 14 December 2017

Sec. Plant Genetics and Genomics

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02116

There is a strong positive relationship between nuclear genome size and cell size across the eukaryotic domain, but the cause and effect of this relationship is unclear. A positive coupling of cell size and DNA content has also been recorded for various bacteria, suggesting that, with some exceptions, this association might be universal throughout the tree of life. However, the link between cell size and genome size has not yet been thoroughly explored with respect to chloroplasts, or organelles as a whole, largely because of a lack data on cell morphology and organelle DNA content. Here, I speculate about a potential positive scaling of cell size and chloroplast genome size within different plastid-bearing protists, including ulvophyte, prasinophyte, and trebouxiophyte green algae. I provide examples in which large and small chloroplast DNAs occur alongside large and small cell sizes, respectively, as well as examples where this trend does not hold. Ultimately, I argue that a relationship between cellular architecture and organelle genome architecture is worth exploring, and encourage researchers to keep an open mind on this front.

Today, I am still intrigued by the massive range in chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA (ptDNA and mtDNA) size as I was as an undergraduate student. Indeed, organelle genome length can differ by more than three orders of magnitude (from a few kilobases to many megabases) across the eukaryotic domain (Smith and Keeling, 2015). And, like with other kinds of genome, this difference in size is largely due to the presence or absence of non-coding DNA. Over the years, I—and many others—have investigated the puzzle of organelle genome size variation from different angles, exploring, for example, the roles of mutation rate, genetic drift, and natural selection on ptDNA and mtDNA expansion (Smith, 2016). But this work has provided no clear answers, except for the realization that the forces influencing organelle genome architecture are complex, multifaceted, and can vary within and among lineages.

Recently, I’ve been asking myself the question: is there a relationship between cell size and chloroplast genome size? This might sound like both a sensible and a silly question. Sensible because there is an extensive body of literature showing a strong positive association between cell size and nuclear genome size in diverse eukaryotes, from plants to animals to protists (Gregory, 2001a; Beaulieu et al., 2008; Connolly et al., 2008); and the same trend holds for various bacteria (Cavalier-Smith, 1982; Shuter et al., 1983; Sabath et al., 2013). However, some might also consider the question silly for at first glance there appears to be no obvious connection between the diameter of a cell and the length of a chloroplast genome. Case in point: 95% of the more than 1,500 completely sequenced ptDNAs from land plants fall within the narrow size range of 120–170 kb despite the fact these genomes come from a remarkable diversity of species and lineages, including ones with drastically different cellular architectures.

But things get a bit more interesting when looking at algae. For instance, the unicellular prasinophyte green alga Ostreococcus tauri is the smallest free-living eukaryote ever observed (∼0.8 μm in diameter) (Courties et al., 1994) and, sure enough, it has one of the smallest known ptDNAs from a photosynthetic organism (71.7 kb, >80% coding, and one intron) (Robbens et al., 2007). Likewise, its close relative Micromonas commoda is also incredibly tiny (<2 μm in diameter) and has a highly reduced ptDNA (72.6 kb) (Worden et al., 2009). In fact, picoeukaryotes as a whole appear to have a propensity for miniaturized chloroplast genomes (Lemieux et al., 2014), as well as for very small mitochondrial and nuclear genomes (Derelle et al., 2006; Robbens et al., 2007; Worden et al., 2009).

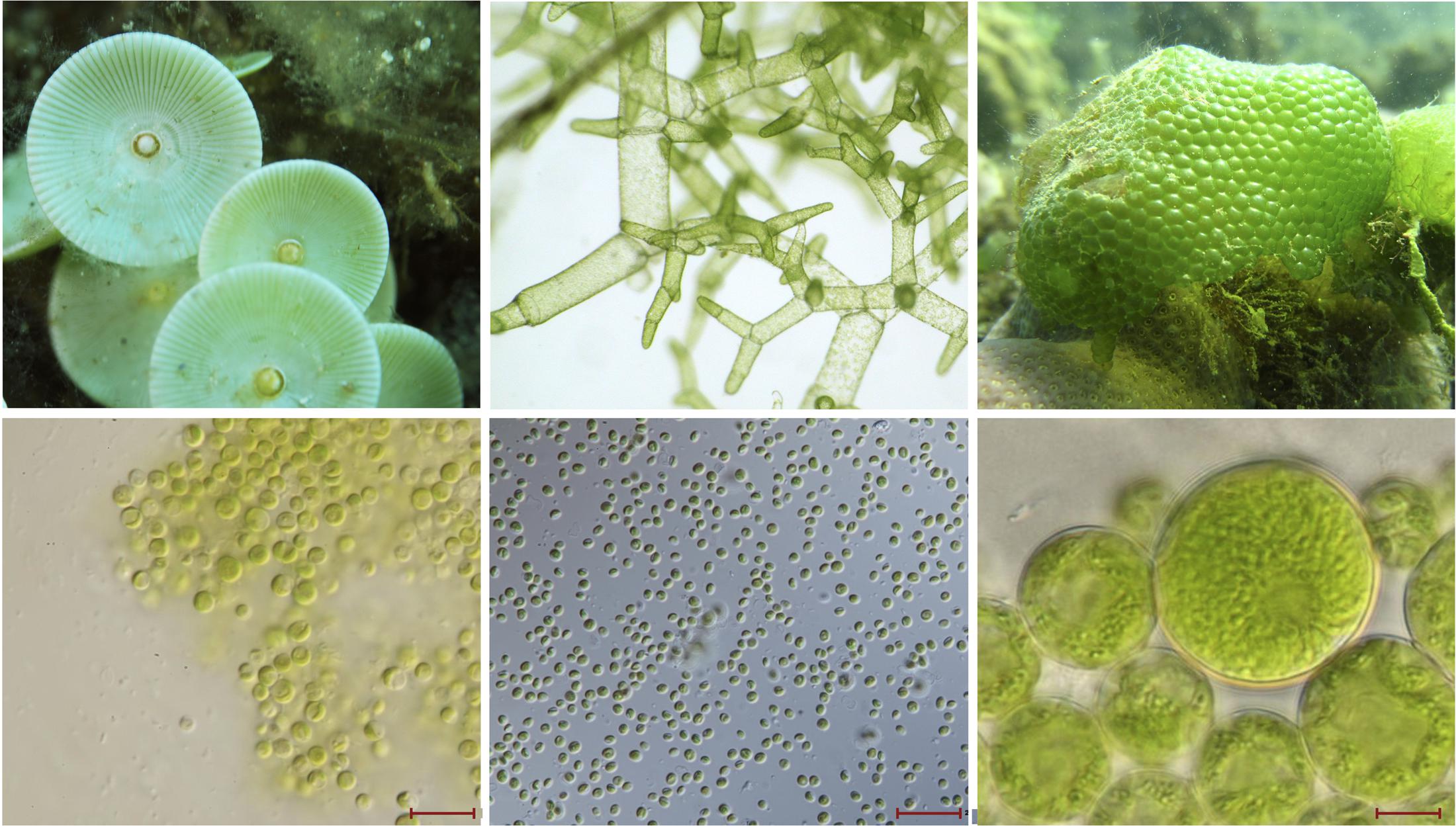

At the other end of the spectrum sits the gargantuan green alga Acetabularia acetabulum (mermaid’s wineglass). This single-celled marine ulvophyte is so massive it can be seen with the naked eye (Figure 1), making it among the largest of all unicellular eukaryotes (1–10 cm) (Mandoli, 1998). It also boasts one the biggest chloroplast genomes on record (∼2 Mb) (Palmer, 1985), but unfortunately the huge number of repeats in this ptDNA have hindered sequencing efforts (de Vries et al., 2013), and its exact size remains unknown (the same is also true for the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes). In addition to a massive cell and chloroplast genome, A. acetabulum also has a huge nucleus (Mandoli, 1998), but the size and number of its chloroplasts are unremarkable (Shephard, 1965). Ulvophytes from the order Cladophorales, such as Boodlea composita, Dictyosphaeria cavernosa, and Valonia ventricosa, can also have large cells (easily visible by the naked eye) (Figure 1), and have recently been shown to have highly fragmented, single-stranded linear ptDNAs, which are partly characterized and potentially very big (Del Cortona et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1. Images of macro- and micro-green algae. (Top) Left to right, large ulvophyte green algae, which are visible by the naked eye: Acetabularia sp. (image by Albert Kok), Boodlea composita (image by Frederik Leliaert), and Dictyosphaeria cavernosa (image by Frederik Leliaert). (Bottom) Left to right, images from Veselá et al. (2011): picoprasinophyte Picosystis salinarum (scale bar 10 μm), picoplanktonic trebouxiophyte Choricystis sp. (scale bar 20 μm), and trebouxiophyte Dictyochloropsis splendida (scale bar 10 μm).

For the longest time, A. acetabulum was the only act in town with an enormous chloroplast genome, but explorations of poorly studied red algal groups have uncovered other species and lineages with prodigious ptDNAs. One of these species is the unicellular rhodellophycean Corynoplastis japonica, whose plastid genome weighs in at a whopping 1.13 Mb, is >80% non-coding, and has 311 introns (Muñoz-Gómez et al., 2017), making it the biggest, most intron-rich ptDNA yet sequenced. The cell size of C. japonica, although not as extraordinary as A. acetabulum, is still quite large (18–33 μm in diameter) (Yokoyama et al., 2009), and an order of magnitude larger than those of O. tauri and M. commoda. The rhodophyte Bulboplastis apyrenoidosa is a close relative of C. japonica and it, too, has an immense plastid genome (0.61 Mb, 220 introns) (Muñoz-Gómez et al., 2017) as well as a moderately large cell (Kushibiki et al., 2012). Red algae can also have small, compact ptDNAs. The ultra-tiny unicell Cyanidioschyzon merolae (2 μm in diameter) has perhaps the most compact plastid genome of all photosynthetic eukaryotes (∼95% coding) (Ohta et al., 2003), as well as very coding dense nuclear and mitochondrial genomes (Ohta et al., 1998; Matsuzaki et al., 2004).

Based on this anecdotal evidence, one could be forgiven for thinking that ptDNA size is positively associated with cell size, at least in certain algae. The problem is that this is not an easy hypothesis to test. Plastid genome size data are lacking for many major algal groups, especially those with “complex” plastids (Burki, 2017), and in some cases when ptDNA size data are available, detailed cell diameter statistics are missing.

One algal lineage for which we are gaining more and more plastid genome data each year and for which there are significant information on cell size are prasinophyte green algae—again, the class to which O. tauri and M. commoda belong. Complete ptDNAs sequences are now available for at least 14 different prasinophytes, spanning six of the major clades (Lemieux et al., 2014; Turmel and Lemieux, 2018). Most of these species are picoplanktonic—organisms with a diameter of less than 3 μm (Figure 1)—and, not surprisingly, their ptDNAs are extraordinarily small and coding-dense, averaging about 80 kb in length. The smallest plastid genome from this cohort belongs to Prasinophyceae sp. CCMP 1205 (64.3 kb) (Lemieux et al., 2014), and although this species has not been formally described, it appears to have a very small cell (Le Gall et al., 2007). Conversely, non-picoplanktonic prasinophytes have much larger genomes and cell sizes (Lemieux et al., 2014). The freshwater prasinophyte Nephroselmis olivacea, for example, has a 200.8 kb plastid genome (Turmel et al., 1999) and a cell size that greatly exceeds that of its picoprasinophyte close relatives: 8–10 μm in diameter, and sometimes much larger (Suda et al., 1989).

Similar trends emerge from trebouxiophyte green algae. Plastome size in the Trebouxiophyceae has generally been unimpressive, but researchers have started identifying species with unexpectedly large (and small) ptDNAs (Turmel et al., 2015). In some instances, big ptDNAs are associated with big cells, and vice versa. As noted by others, the ptDNAs of picoplanktonic and nanoplanktonic taxa (Figure 1), such as Choricystis minor (94.2 kb), Marsupiomonas sp. NIES 1824 (94.3 kb), Pedimonas minor (98.3 kb), and Marvania geminata (108.5 kb), are the smallest among explored trebouxiophytes (Turmel et al., 2015). Species with larger cells (Figure 1), however, can have much longer ptDNAs. Take Dictyochloropsis reticulata (also called Symbiochloris handae), which can have cells as large as 26 μm in diameter (Škaloud et al., 2016) and houses a 289.4 kb plastid genome (Turmel et al., 2015). Similarly, Pleurastrosarcina brevispinosa (also called Chlorosarcina brevispinosa) is approximately 25 μm in diameter when mature (Chantanachat and Bold, 1962) and has a ptDNA in excess of 295 kb, the second largest currently found in the Trebouxiophyceae (Turmel et al., 2015). The largest plastome in the class belongs to Prasiolopsis sp. SAG 84.81 (306 kb), but cell morphology data are unavailable for this strain.

Of course, one can find examples where these trends do not hold. The phagomixotrophic prasinophyte Cymbomonas tetramitiformis is far from small (∼10 um in diameter) (Maruyama and Kim, 2013) but has a minute ptDNA (∼85 kb) (Satjarak et al., 2016). Most diatom and dinoflagellate algae do not have particularly large ptDNAs but can have very big cells (Finkel et al., 2009). The colonial chlamydomonadalean alga Tetrabaena socialis has a large ptDNA (>405 kb) (Featherston et al., 2016), but its cell size is unexceptional (∼10 μm in diameter). Its close multicellular relative Volvox carteri has an even longer plastome (∼525 kb) (Smith and Lee, 2010) and, likewise, the average somatic cell size is only 5–9 μm, but the asexual reproductive cells (gonidia) are much larger (13–90 μm) (Kirk et al., 1993). Closely affiliated with the Chlamydomonadales is another order—the Chaetopeltidales—with huge ptDNAs. The chaetopeltidalean species Koshicola spirodelophila and Floydiella terrestris have giant plastomes (384.9 and ∼520 kb, respectively), but unlike their chlamydomonadalean counterparts they do have hefty cells (up to 32 μm long and 55 μm wide) (Brouard et al., 2010; Watanabe et al., 2016).

Then there is the non-photosynthetic green algal genus Polytomella whose members appear to have completely forfeited their plastid genomes (Smith and Lee, 2014) but do not have overly small cells (about 10–15 μm in diameter) (Pringsheim, 1955). However, the forces responsible for extreme plastid genome reduction and outright plastome loss are arguably different than those involved in the expansion and contraction of non-coding ptDNA (Figueroa-Martinez et al., 2017). For all we know, the ancestral ptDNA of Polytomella species might have had an expanded architecture before being jettisoned. The colorless green alga Polytoma uvella, which is closely related to Polytomella (the two lineages lost photosynthesis independently of one another), has the most expanded ptDNA ever found in a non-photosynthetic species (∼230 kb, 75% non-coding DNA) (Figueroa-Martinez et al., 2017). P. uvella is also relatively large for a plastid-bearing colourless protist: up to 18 μm long and 14.5 μm wide (Moewus and Moewus, 1959).

So, after considering the points described above, I’m still left scratching my head, wondering if there isn’t, for some species, a link between cell size and chloroplast genome size. For now, detailed data on cell morphology and ptDNA length are too sparse to rigorously test such a hypothesis, nor would I necessarily want to argue in favor of one just yet. My aim is to simply point out that the relationship between cellular architecture and organelle genome architecture is worth exploring, and to encourage researchers to keep an open mind on this front.

Some readers might have noted that I skimmed over an important point regarding previous work on cell size and genome size: it is not so much that big cells have big genomes (and vice versa) but that big cell have big DNA contents (Gregory, 2001b). Because nuclear genomes often have low ploidy levels (e.g., haploid or diploid), the DNA content of nuclei is strongly positively correlated with genome size, and thus both these parameters scale positively with cell size (Gregory, 2001b). However, in highly polyploid systems it is possible to have a high DNA content occurring alongside a small or moderately sized genome. The gram-positive bacterium Epulopiscium fishelsoni exemplifies this point. It has a 3.8 Mb circular genome, which is present in about 200,000 copies, resulting in a DNA content in excess of 750 Gb (Mendell et al., 2008). E. fishelsoni is also one of the largest known prokaryotes, growing up to 600 μm in length (Bresler et al., 1998).

Chloroplasts and mitochondria are polyploid. The number of genomes per organelle can vary throughout a lifecycle, across tissues in multicellular organisms, and from species to species, but it is usually quite high (>10), sometimes extremely so (Kuroiwa et al., 1981; Raven, 2015; Cole, 2016). The cryptophyte alga Guillardia theta, for instance, carries between 130 and 260 copies of its 121.5 kb plastid genome (Hirakawa and Ishida, 2014), and some land plants have nearly a 1000 copies of the ptDNA in their chloroplasts (Raven, 2015, and reference therein). Even more impressive are the mitochondria from diplonemid and kinetoplastid protists, which can contain 1000s of copies of a fragmented mitochondrial genome leading to hyper-inflated mtDNA contents, whereby the mitochondria can contain more DNA than the nucleus (David et al., 2015). The mitochondrion of the kinetoplastid Perkinsella strain Gill-NOR1/I is so inflated with DNA that it takes up nearly the entire cell and can be >10 μm in diameter (David et al., 2015). Similarly, there are species with giant chloroplasts an elevated ptDNA contents (e.g., Vicia faba), and plastid genome copy number has long been known to rise in parallel with increases in chloroplast volume, and to go down alongside a reduction in volume (Kuroiwa et al., 1981). It is noteworthy in this context that the ptDNA copy number in the chloroplasts of Acetabularia is estimated to be small (1–4) (Kuroiwa et al., 1981).

Organelle ploidy level is not an easy parameter to calculate (Rooney et al., 2015), and can be influenced by many different factors, including evolutionary forces acting on genes involved in organelle biogenesis and organelle–nuclear gene interactions (Cole, 2016). Consequently, we still have a lot to learn about the DNA content and genome length of chloroplasts and mitochondria and how they might be connected to other cellular features, including cell size and organelle volume. It has been shown that the number of mitochondria and chloroplasts per cell can influence the rate of intracellular DNA transfer from organelles to the nucleus (Smith et al., 2011) and from plastids to mitochondria (Smith, 2011). Environmental conditions are also thought to influence organelle DNA architecture. For example, plastid genomic compaction in the endolithic ulvophyte seaweed Ostreobium quekettii and the palmophylalean green alga Verdigellas peltata is thought to have been shaped primarily by adaptation to low light conditions (Marcelino et al., 2016).

Much has been written about the processes responsible for the well-established link between DNA content and cell size and whether it is adaptive or non-adaptive (Cavalier-Smith, 1982; Gregory, 2001b; Lynch, 2007). Some have argued that genomic streamlining and its strong association with a small cell size and a high growth rate provides a metabolic advantage in certain situations (Hessen et al., 2010), and it has been noted that streamlined ptDNAs in picoplanktonic and nanoplanktonic chlorophytes could confer a selective advantage (Turmel and Lemieux, 2018). Others have suggested that DNA may have quantitative non-coding functions, potentially acting as a “skeleton” within the cell (Cavalier-Smith, 1982). And there is always the strong possibility that the forces influencing genome size are purely non-adaptive (Lynch, 2007). Finally, the likelihood that cell size is directly connected to important traits, such as photosynthetic rate, are also important considerations when evaluating potential relationships between cell size and genome size. If there does turn out to be a relationship between cell size and organelle DNA length/content in certain systems, it will likely only add further mystery and complexity to the long-standing debate about the evolution of genome size.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

DS is supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada.

Beaulieu, J. M., Leitch, I. J., Patel, S., Pendharkar, A., and Knight, C. A. (2008). Genome size is a strong predictor of cell size and stomatal density in angiosperms. New Phytol. 179, 975–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02528.x

Bresler, V., Montgomery, W. L., Fishelson, L., and Pollak, P. E. (1998). Gigantism in a bacterium, Epulopiscium fishelsoni, correlates with complex patterns in arrangement, quantity, and segregation of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 180, 5601–5611.

Brouard, J. S., Otis, C., Lemieux, C., and Turmel, M. (2010). The exceptionally large chloroplast genome of the green alga Floydiella terrestris illuminates the evolutionary history of the Chlorophyceae. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 240–256. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq014

Burki, F. (2017). The convoluted evolution of eukaryotes with complex plastids. Adv. Bot. Res. 84, 1–30. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2017.06.001

Cavalier-Smith, T. (1982). Skeletal DNA and the evolution of genome size. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 11, 273–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.11.060182.001421

Chantanachat, S., and Bold, H. C. (1962). Phycological studies. II. Some algae from arid soils. Univ. Texas Publ. 6218, 1–74.

Cole, L. W. (2016). The evolution of per-cell organelle number. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4:85. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00085

Connolly, J. A., Oliver, M. J., Beaulieu, J. M., Knight, C. A., Tomanek, L., and Moline, M. A. (2008). Correlated evolution of genome size and cell volume in diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 44, 124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00452.x

Courties, C., Vaquer, A., Troussellier, M., Lautier, J., Chrétiennot-Dinet, M. J., Neveux, J., et al. (1994). Smallest eukaryotic organism. Nature 370, 255–255. doi: 10.1038/370255a0

David, V., Flegontov, P., Gerasimov, E., Tanifuji, G., Hashimi, H., Logacheva, M. D., et al. (2015). Gene loss and error-prone RNA editing in the mitochondrion of Perkinsela, an endosymbiotic kinetoplastid. Mbio 6:e01498–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01498-15

de Vries, J., Habicht, J., Woehle, C., Huang, C., Christa, G., Wägele, H., et al. (2013). Is ftsH the key to plastid longevity in sacoglossan slugs? Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 2540–2548. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt205

Del Cortona, A., Leliaert, F., Bogaert, K. A., Turmel, M., Boedeker, C., Janouškovec, J., et al. (2017). The plastid genome in Cladophorales green algae is encoded by hairpin chromosomes. Curr. Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.004 [Epub ahead of print].

Derelle, E., Ferraz, C., Rombauts, S., Rouzé, P., Worden, A. Z., Robbens, S., et al. (2006). Genome analysis of the smallest free-living eukaryote Ostreococcus tauri unveils many unique features. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11647–11652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604795103

Featherston, J., Arakaki, Y., Nozaki, H., Durand, P. M., and Smith, D. R. (2016). Inflated organelle genomes and a circular-mapping mtDNA probably existed at the origin of coloniality in volvocine green algae. Eur. J. Phycol. 51, 369–377. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2016.1198830

Figueroa-Martinez, F., Nedelcu, A. M., Smith, D. R., and Reyes-Prieto, A. (2017). The plastid genome of Polytoma uvella is the largest known among colorless algae and plants and reflects contrasting evolutionary paths to nonphotosynthetic lifestyles. Plant Physiol. 173, 932–943. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01628

Finkel, Z. V., Beardall, J., Flynn, K. J., Quigg, A., Rees, T. A. V., and Raven, J. A. (2009). Phytoplankton in a changing world: cell size and elemental stoichiometry. J. Plankton Res. 32, 119–137. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbp098

Gregory, T. R. (2001a). The bigger the C-value, the larger the cell: genome size and red blood cell size in vertebrates. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 27, 830–843.

Gregory, T. R. (2001b). Coincidence, coevolution, or causation? DNA content, cell size, and the C-value enigma. Biol. Rev. 76, 65–101.

Hessen, D. O., Jeyasingh, P. D., Neiman, M., and Weider, L. J. (2010). Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004

Hirakawa, Y., and Ishida, K. I. (2014). Polyploidy of endosymbiotically derived genomes in complex algae. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 974–980. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu071

Kirk, M. M., Ransick, A., McRae, S. E., and Kirk, D. L. (1993). The relationship between cell size and cell fate in Volvox carteri. J. Cell Biol. 123, 191–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.191

Kuroiwa, T., Suzuki, T., Ogawa, K., and Kawano, S. (1981). The chloroplast nucleus: distribution, number, size, and shape, and a model for the multiplication of the chloroplast genome during chloroplast development. Plant Cell Physiol. 22, 381–396.

Kushibiki, A., Yokoyama, A., Iwataki, M., Yokoyama, J., West, J. A., and Hara, Y. (2012). New unicellular red alga, Bulboplastis apyrenoidosa gen. et sp. nov. (Rhodellophyceae, Rhodophyta) from the mangroves of Japan: phylogenetic and ultrastructural observations. Phycol. Res. 60, 114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1835.2012.00643.x

Le Gall, F., Rigaut-Jalabert, F., Marie, D., Garczarek, L., Viprey, M., Gobet, A., et al. (2007). Picoplankton diversity in the South-East Pacific Ocean from cultures. Biogeosciences 4, 2699–2732. doi: 10.5194/bgd-4-2699-2007

Lemieux, C., Otis, C., and Turmel, M. (2014). Six newly sequenced chloroplast genomes from prasinophyte green algae provide insights into the relationships among prasinophyte lineages and the diversity of streamlined genome architecture in picoplanktonic species. BMC Genomics 15:857. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-857

Mandoli, D. F. (1998). Elaboration of body plan and phase change during development of Acetabularia: How is the complex architecture of a giant unicell built? Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 49, 173–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.173

Marcelino, V. R., Cremen, M. C. M., Jackson, C. J., Larkum, A. W., and Verbruggen, H. (2016). Evolutionary dynamics of chloroplast genomes in low light: a case study of the endolithic green alga Ostreobium quekettii. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 2939–2951. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw206

Maruyama, S., and Kim, E. (2013). A modern descendant of early green algal phagotrophs. Curr. Biol. 23, 1081–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.063

Matsuzaki, M., Misumi, O., Shin-i, T., Maruyama, S., Takahara, M., Miyagishima, S. Y., et al. (2004). Genome sequence of the ultrasmall unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae 10D. Nature 428, 653–658. doi: 10.1038/nature02398

Mendell, J. E., Clements, K. D., Choat, J. H., and Angert, E. R. (2008). Extreme polyploidy in a large bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6730–6734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707522105

Moewus, F., and Moewus, L. (1959). Synchronization of the phases of the life cycle of Polytoma uvella (strain WH). Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 78, 163–172. doi: 10.2307/3224025

Muñoz-Gómez, S. A., Mejía-Franco, F. G., Durnin, K., Colp, M., Grisdale, C. J., Archibald, J. M., et al. (2017). The new red algal subphylum Proteorhodophytina comprises the largest and most divergent plastid genomes known. Curr. Biol. 27, 1677–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.054

Ohta, N., Matsuzaki, M., Misumi, O., Miyagishima, S. Y., Nozaki, H., Tanaka, K., et al. (2003). Complete sequence and analysis of the plastid genome of the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. DNA Res. 10, 67–77. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.2.67

Ohta, N., Sato, N., and Kuroiwa, T. (1998). Structure and organization of the mitochondrial genome of the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae deduced from the complete nucleotide sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 5190–5198. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5190

Palmer, J. D. (1985). Comparative organization of chloroplast genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 19, 325–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001545

Raven, J. A. (2015). Implications of mutation of organelle genomes for organelle function and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5639–5650. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv298

Robbens, S., Derelle, E., Ferraz, C., Wuyts, J., Moreau, H., and Van de Peer, Y. (2007). The complete chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA sequence of Ostreococcus tauri: organelle genomes of the smallest eukaryote are examples of compaction. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 956–968. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm012

Rooney, J. P., Ryde, I. T., Sanders, L. H., Howlett, E. H., Colton, M. D., Germ, K. E., et al. (2015). PCR based determination of mitochondrial DNA copy number in multiple species. Methods Mol. Biol. 1241, 23–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1875-1_3

Sabath, N., Ferrada, E., Barve, A., and Wagner, A. (2013). Growth temperature and genome size in bacteria are negatively correlated, suggesting genomic streamlining during thermal adaptation. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 966–977. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt050

Satjarak, A., Paasch, A. E., Graham, L. E., and Kim, E. (2016). Complete chloroplast genome sequence of phagomixotrophic green alga Cymbomonas tetramitiformis. Genome Announc. 4:e00551–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00551-16

Shephard, D. C. (1965). Chloroplast multiplication and growth in the unicellular alga Acetabularia mediterranea. Exp. Cell Res. 37, 93–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90160-6

Shuter, B. J., Thomas, J. E., Taylor, W. D., and Zimmerman, A. M. (1983). Phenotypic correlates of genomic DNA content in unicellular eukaryotes and other cells. Am. Nat. 122, 26–44. doi: 10.1086/284116

Škaloud, P., Friedl, T., Hallmann, C., Beck, A., and Dal Grande, F. (2016). Taxonomic revision and species delimitation of coccoid green algae currently assigned to the genus Dictyochloropsis (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 52, 599–617. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12422

Smith, D. R. (2011). Extending the limited transfer window hypothesis to inter-organelle DNA migration. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 743–748. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr068

Smith, D. R. (2016). The mutational hazard hypothesis of organelle genome evolution: 10 years on. Mol. Ecol. 25, 3769–3775. doi: 10.1111/mec.13742

Smith, D. R., Crosby, K., and Lee, R. W. (2011). Correlation between nuclear plastid DNA abundance and plastid number supports the limited transfer window hypothesis. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 365–371. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr001

Smith, D. R., and Keeling, P. J. (2015). Mitochondrial and plastid genome architecture: reoccurring themes, but significant differences at the extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 10177–10184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422049112

Smith, D. R., and Lee, R. W. (2010). Low nucleotide diversity for the expanded organelle and nuclear genomes of Volvox carteri supports the mutational-hazard hypothesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 2244–2256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq110

Smith, D. R., and Lee, R. W. (2014). A plastid without a genome: evidence from the nonphotosynthetic green algal genus Polytomella. Plant Physiol. 164, 1812–1819. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233718

Suda, S., Watanabe, M. M., and Inouye, I. (1989). Evidence for sexual reproduction in the primitive green alga Nephroselmis olivacea (Prasinophyceae). J. Phycol. 25, 596–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1989.tb00266.x

Turmel, M., and Lemieux, C. (2018). Evolution of the plastid genome in chlorophyte and streptophyte green algae. Adv. Bot. Res. (in press).

Turmel, M., Otis, C., and Lemieux, C. (1999). The complete chloroplast DNA sequence of the green alga Nephroselmis olivacea: insights into the architecture of ancestral chloroplast genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10248–10253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10248

Turmel, M., Otis, C., and Lemieux, C. (2015). Dynamic evolution of the chloroplast genome in the green algal classes Pedinophyceae and Trebouxiophyceae. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 2062–2082. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv130

Veselá, J., Škaloud, P., Urbánková, P., and Škaloudová, M. (2011). The CAUP image database. Fottea 11, 313–316. doi: 10.5507/fot.2011.029

Watanabe, S., Fuèíková, K., Lewis, L. A., and Lewis, P. O. (2016). Hiding in plain sight: Koshicola spirodelophila gen. et sp. nov. (Chaetopeltidales, Chlorophyceae), a novel green alga associated with the aquatic angiosperm Spirodela polyrhiza. Am. J. Bot. 103, 865–875. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500481

Worden, A. Z., Lee, J. H., Mock, T., Rouzé, P., Simmons, M. P., Aerts, A. L., et al. (2009). Green evolution and dynamic adaptations revealed by genomes of the marine picoeukaryotes Micromonas. Science 324, 268–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1167222

Yokoyama, A., Scott, J. L., Zuccarello, G. C., Kajikawa, M., Hara, Y., and West, J. A. (2009). Corynoplastis japonica gen. et sp. nov. and Dixoniellales ord. nov. (Rhodellophyceae, Rhodophyta) based on morphological and molecular evidence. Phycol. Res. 57, 278–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1835.2009.00547.x

Keywords: Acetabularia, cell size, DNA content, genome size, plastid genome

Citation: Smith DR (2017) Does Cell Size Impact Chloroplast Genome Size?. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2116. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02116

Received: 06 October 2017; Accepted: 28 November 2017;

Published: 14 December 2017.

Edited by:

Paula Casati, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), ArgentinaReviewed by:

Chris Organ, Montana State University, United StatesCopyright © 2017 Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David R. Smith, ZHNtaXQyNDJAdXdvLmNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.