- 1National Research Council – Tree and Timber Institute, Florence, Italy

- 2Department of Agrifood Production and Environmental Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

- 3National Research Council – Institute of Biometeorology, Florence, Italy

Physiological control of stomatal conductance (Gs) permits plants to balance CO2-uptake for photosynthesis (PN) against water-loss, so optimizing water use efficiency (WUE). An increase in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide ([CO2]) will result in a stimulation of PN and reduction of Gs in many plants, enhancing carbon gain while reducing water-loss. It has also been hypothesized that the increase in WUE associated with lower Gs at elevated [CO2] would reduce the negative impacts of drought on many crops. Despite the large number of CO2-enrichment studies to date, there is relatively little information regarding the effect of elevated [CO2] on stomatal control. Five crop species with active physiological stomatal behavior were grown at ambient (400 ppm) and elevated (2000 ppm) [CO2]. We investigated the relationship between stomatal function, stomatal size, and photosynthetic capacity in the five species, and then assessed the mechanistic effect of elevated [CO2] on photosynthetic physiology, stomatal sensitivity to [CO2] and the effectiveness of stomatal closure to darkness. We observed positive relationships between the speed of stomatal response and the maximum rates of PN and Gs sustained by the plants; indicative of close co-ordination of stomatal behavior and PN. In contrast to previous studies we did not observe a negative relationship between speed of stomatal response and stomatal size. The sensitivity of stomata to [CO2] declined with the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate limited rate of PN at elevated [CO2]. The effectiveness of stomatal closure was also impaired at high [CO2]. Growth at elevated [CO2] did not affect the performance of photosystem II indicating that high [CO2] had not induced damage to the photosynthetic physiology, and suggesting that photosynthetic control of Gs is either directly impaired at high [CO2], sensing/signaling of environmental change is disrupted or elevated [CO2] causes some physical effect that constrains stomatal opening/closing. This study indicates that while elevated [CO2] may improve the WUE of crops under normal growth conditions, impaired stomatal control may increase the vulnerability of plants to water deficit and high temperatures.

Introduction

Stomatal pores act as the interface between the plant and the atmosphere, regulating the uptake of CO2 for photosynthesis (PN) and the loss of water via transpiration. Photosynthesis rates are positively related to stomatal conductance (Gs; Wong et al., 1979; Flexas and Medrano, 2002), and effective stomatal control through morphological changes to the number of stomata and physiological regulation of stomatal aperture size allows the optimal balance of CO2-uptake and water-loss over a range of favorable and sub-optimal growth conditions (Flexas et al., 2002; Lauteri et al., 2014; Haworth et al., 2015). Physiological regulation of the size of the stomatal pore aperture ranges from ‘active’ to ‘passive’ stomatal behavior. Active stomatal behavior involves rapid alteration of stomatal aperture following an external stimulus as ions are actively pumped across guard cell membranes to alter guard cell turgor. Alternatively, where guard cell turgor, and as a result pore area, follows whole leaf turgor, stomatal behavior is considered to be passive (Chater et al., 2013). The development of crop species has involved the selection of more productive and faster growing varieties over multiple generations (Evans, 1980; Roche, 2015). These selected varieties often possess greater leaf area rates of PN than their less productive counterparts (Zelitch, 1982; Fischer et al., 1998; Gu et al., 2014). As a result, the vast majority of crops currently cultivated possess active stomatal physiological behavior that permits the levels of Gs required to sustain high PN, but also the capacity to respond rapidly to a change in environmental conditions (Kalaji and Nalborczyk, 1991; Haworth et al., 2015; Roche, 2015). However, it is unclear how active physiological stomatal behavior in crop plants can be affected by changes in the atmospheric concentration of [CO2], and whether growth at elevated [CO2] can induce a loss of stomatal control.

Rising atmospheric [CO2] is considered to have a beneficial effect on the carbon balance of plants though CO2-fertilization and reduced transpirative water-loss generally associated with lower Gs that results in an increase in water use efficiency (WUE; Centritto et al., 2002; Wullschleger et al., 2002; Haworth et al., 2016). Nonetheless, climate change will also result in an increase in the frequency, severity and duration of drought, and increased temperature events (Ciais et al., 2005). In these cases, effective stomatal control is crucial to the plant stress response (e.g., Bunce, 2000; Shah and Paulsen, 2003; Killi et al., 2016), particularly in fast-growing crop species with high maximum rates of Gs. It has been suggested that smaller stomata are able to open and close more rapidly, thus affording greater responsiveness to a change in growth conditions (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Drake et al., 2013). Plants with large numbers of small stomata are also able to maintain greater levels of Gs (de Boer et al., 2016), potentially as an adaptation to declining [CO2] over the Cenozoic (Franks and Beerling, 2009). It may therefore be expected that stomatal size, the speed of stomatal closure and maximal rates of PN and Gs are closely associated in fast-growing plants with active stomatal behavior. Nevertheless, the impact of growth at elevated [CO2] on the regulation of stomatal aperture is largely unknown.

Stomatal aperture is regulated by network of interlinked signals (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003) incorporating photosynthesis in the light (Messinger et al., 2006) and the physiological status of the plant (e.g., Lauteri et al., 2014). Beech (Fagus sylvatica), chestnut (Castanea sativa), and oak (Quercus robur) all exhibit an inverse relationship between Gs and leaf to air vapor pressure deficit (VPD) under light conditions when grown at ambient [CO2]. However, when grown in atmospheres enriched in [CO2] to 710 ppm, oak and chestnut showed reduced stomatal sensitivity to VPD, while beech no longer altered Gs to VPD (Heath, 1998). Growth at elevated [CO2] did not induce a reduction of Gs in beech, but also reduced the speed (∼-25% after 4 days) and tightness (∼-22% over a soil water potential range of -200 to -250 hPa) of stomatal closure in response to soil drying. This impaired stomatal control was associated with reduced stomatal sensitivity to the drought stress hormone ABA in the beech plants grown at elevated [CO2]. Furthermore, an increase in leaf area, alongside the loss of stomatal control incurred at high [CO2], made the beech trees more susceptible to drought stress when grown in atmospheres enriched in [CO2] (Heath and Kerstiens, 1997). The cycad Lepidozamia peroffskyana and broad-leaved conifer Nageia nagi both exhibit active stomatal control when grown at ambient [CO2] under well-watered conditions. However, when grown at elevated [CO2] of 1500 ppm, both species no longer adjusted Gs in response to an instantaneous change in external [CO2] (Ca; Haworth et al., 2013), indicative of a loss of stomatal control. Hollyfern (Cyrtomium fortunei) also showed a loss of stomatal sensitivity to Ca and impaired stomatal closure during darkness when grown in atmospheres of 2000 ppm [CO2] (Haworth et al., 2015). Such a loss of stomatal control at high [CO2] would impair the capacity of plants to limit water-loss associated with PN during episodes of high transpirative demand.

Effective stomatal control is not only important during light-driven assimilation of CO2, but also when conditions are not favorable for PN (Killi et al., 2016). At night many plants do not close their stomata to their full extent, resulting in transpirative water-loss in the absence of PN. Night-time Gs in Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus sideroxylon) is 30% of levels recorded in the day-time (Zeppel et al., 2012), and can be as high as 250 mmol m-2 s-1 in many plants (Caird et al., 2007), thus representing a significant loss of water. The ecological function of night-time Gs is unclear, but is hypothesized to be related to the maintenance of root mass-flow of water to ensure the uptake of mobile nutrients such as nitrogen (Caird et al., 2007). Under elevated [CO2] of 640 ppm and not experiencing drought, Eucalyptus exhibited a 17% increase in night-time Gs, but levels of Gs during the day-time were identical at ambient and elevated [CO2] (Zeppel et al., 2012); possibly as an adaptation to enhance nutrient uptake due to reduced root mass-flow of water under elevated [CO2] (Van Vuuren et al., 1997). Under optimal growth conditions, during the night plant water potential generally equilibrates with that of soil water potential (Hinckley et al., 1978; Donovan et al., 2001). Increased night-time Gs may impair the equilibration of leaf and soil water potentials, or in the case of promoting root mass-flow to enhance nutrient uptake may indicate some underlying nutrient deficiency in the plants. This increase in night-time Gs under elevated [CO2] may seem somewhat incongruous, as an increase in [CO2] is widely considered likely to reduce Gs (Centritto et al., 1999; Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007). However, a rise in [CO2] may impair stomatal function, resulting in stomatal pores that close more slowly and less tightly (e.g., Haworth et al., 2015), potentially accounting for observations of increased night-time Gs at elevated [CO2] (Zeppel et al., 2012). Measurement of the speed of the stomatal response of plants grown under elevated [CO2] to darkness (i.e., conditions no longer conducive to PN) and the tightness of stomatal closure (Haworth et al., 2015) may provide indications of any loss of stomatal function associated with high [CO2].

The loss of stomatal control represented by the reduced capacity and speed of stomatal closure at elevated [CO2] may render plants vulnerable to desiccation during episodes of drought or high transpirative demand. This is counter to the prevailing consensus that an increase in [CO2] would improve WUE (Centritto et al., 2002; Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007) and mitigate drought by reducing water-loss (Wall, 2001). A loss of stomatal control and increased vulnerability to drought and heat-waves would have severe implications for crops such as wheat (e.g., Stratonovitch and Semenov, 2015). However, there is comparatively little information regarding the impact of elevated [CO2] on stomatal control in crop species. Photosynthesis in the mesophyll layer and Gs are closely co-ordinated via Ci in the presence of red light (Messinger et al., 2006; Engineer et al., 2016). It is possible that any effect of elevated [CO2] may have an effect upon the regulation of stomatal aperture via a direct effect on PN. To study the mechanistic effects of elevated [CO2] on stomatal control in C3 crop plants we grew oat (Avena sativa), sunflower (Helianthus annuus), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and wheat (Triticum aestivum) under ambient (400 ppm) and elevated (2000 ppm) [CO2]. As comparatively little is known about how growth at elevated [CO2] can affect stomatal control, a higher [CO2] level was chosen for the elevated treatment than concentrations predicted by the IPCC (2007) models, but not in the context of atmospheric [CO2] over the last 200 million years (Berner, 2009), as this would clearly demonstrate whether growth at elevated [CO2] has a mechanistic effect on stomatal function. The effect of growth at elevated [CO2] on stomatal control (tightness of closure following a cessation of illumination and sensitivity to instantaneous changes in Ca: reported in a previous study, with the exception of wheat, of Haworth et al., 2015) and the interaction with photosynthetic physiology were investigated. We hypothesize that these fast-growing crop species with high rates of PN will exhibit a high degree of stomatal control, but that this stomatal control may become impaired at elevated [CO2]. This study aims to: (i) investigate potential correlations between stomatal pore size and the speed of stomatal closure, and whether species with ‘fast’ stomata possess greater maximum rates of Gs and PN; (ii) determine how stomatal control in crop plants with active physiological stomatal behavior is affected by growth at elevated [CO2] through analysis of speed and tightness of stomatal closure following the cessation of illumination and stomatal sensitivity to instantaneous increases in Ca; (iii) assess whether adjustment of the photosynthetic physiology may affect stomatal control at high [CO2] either through alteration of the ‘photosynthetic’ stomatal response to [CO2], or damage to the photosynthetic apparatus incurred by growth at elevated [CO2], and; (iv) explore the possible implications of any change in stomatal control for crop plants growing in a future high [CO2] and water-limited world.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth Conditions

The plants were potted in 6 dm3 square pots using a 5:1 mixture of commercial compost and vermiculite and placed in two large walk-in growth rooms with full control of light, temperature, [CO2] (one chamber maintained ambient atmospheric [CO2] of 400 ppm and the second an elevated [CO2] level of 2000 ppm) and humidity for 16-week (technical details of the plant growth chambers are given in Materassi et al., 2005). The plants were watered to pot capacity every 2 days and provided weekly with a commercial liquid plant fertilizer (COMPO Concime Universale, NPK 7-5-7, B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Zn: COMPO Italia, Cesano Maderno, Italy) to facilitate nutrient availability at free access rates. The growth chambers maintained conditions of 16 h of daylight (14 h at full PAR levels of 1000 μmol m-2 s-1 with two 1-h periods of simulated dawn/dusk where light intensity was incrementally increased/decreased), a day and night-time temperature regime of 25/18°C and constant relative humidity of 50%. To avoid potential chamber effects, the growth rooms were alternated every 2 weeks – no significant differences were observed in the measurements conducted under the same conditions in different growth chambers. Timings of day/night programs on the plant growth chambers were staggered to allow the maximum number of plants to be analyzed at the optimal time of the day/night program for photosynthetic activity (07:00–11:00 h), and thus avoid the influence of circadian stomatal behavior; particularly where stomata close at midday or during the early afternoon when leaf water potentials may decrease. Four replicates of each species were grown under ambient and elevated [CO2], and a minimum of three replicates were used for the measurement of stomatal sensitivity to Ca and closure in response to darkness.

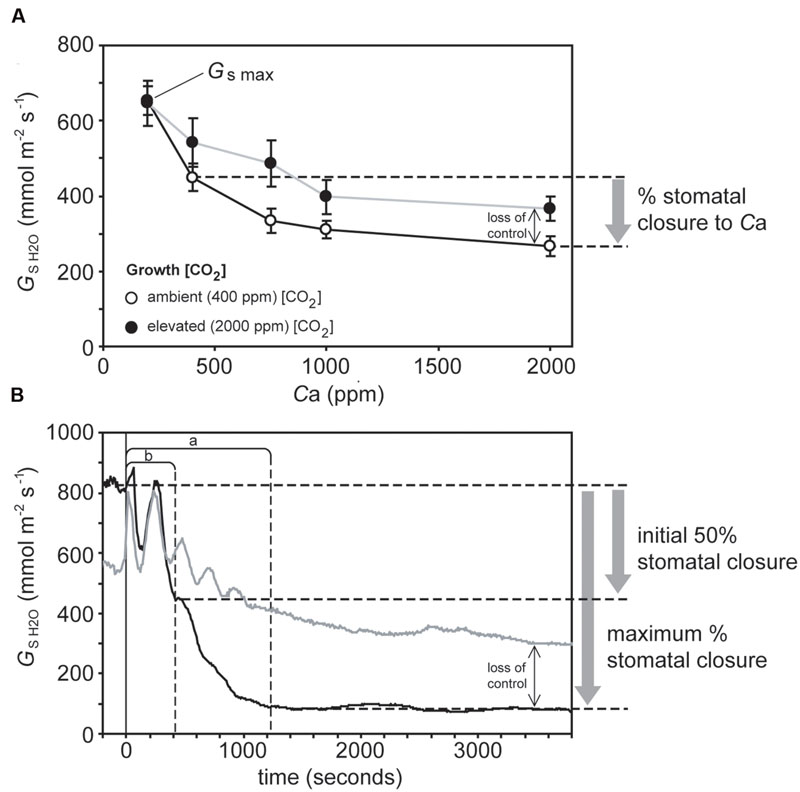

Leaf Gas-Exchange Analysis of Stomatal Control

A PP-Systems Ciras-2 attached to a PLC6(U) leaf cuvette and LED light unit (PP-Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) was used to gauge the physiological response of stomata to darkness and Ca. All physiological measurements were conducted on the same leaf per plant (no more than one measurement was performed on each plant over 48 h) in a well-ventilated air-conditioned room maintained at 25°C. The newest fully expanded leaf was consistently used for analysis (in grasses this was the leaf below the flag leaf) to avoid any age-related effects regarding stomatal functionality. To assess the physiological stomatal behavioral responses of the plants to Ca, the level of [CO2] within the leaf cuvette was increased in a number of stages (200, 400, 750, 1000, and 2000 ppm CO2) while temperature (25°C), VPD (1.6–1.8 KPa ± 0.1 KPa), and light intensity (2000 μmol m-2 s-1) remained constant. At each [CO2] step, the stomatal conductance of water vapor (Gs H2O) was allowed to stabilize and then remain stable for 5–10 min before being recorded. Maximum stomatal conductance (Gs max) was considered to be Gs H2O recorded at a [CO2] of 50 ppm to induce full stomatal opening (Centritto et al., 2003). Stomatal closure was expressed as the percentage of Gs H2O values at 2000 ppm CO2 relative to those recorded at an ambient [CO2] of 400 ppm (Figure 1). To measure the stomatal response to darkness, a leaf was placed in the leaf cuvette with a temperature of 25°C, PAR of 2000 μmol m-2 s-1 and 400 ppm [CO2]. After Gs H2O had remained stable for 15 min the lights in both the cuvette and the room were simultaneously switched off and Gs H2O was recorded every 10 s for a minimum of 1 h (Meidner and Mansfield, 1965). Vapor pressure deficit in the cuvette was maintained between 1.6 to 1.8 KPa ± 0.1 KPa throughout the measurement of the stomatal response to darkness. Stomatal closure in response to the cessation of illumination was expressed as the percentage Gs H2O after 1-h of darkness. The speed of stomatal closure is not uniform after the onset of darkness (Haworth et al., 2015); the reduction in Gs H2O per second over the first 50% reduction in Gs H2O, and also over the time to reach the maximum extent of stomatal closure was therefore determined (Figure 1). Measurements of stomatal pore length (SPL) of the plants under ambient and elevated [CO2] were taken from Haworth et al. (2015).

FIGURE 1. Illustration of gas exchange measurements in sunflower to determine: (A) Stomatal sensitivity to Ca – plants grown in atmospheres of 400 ppm (open symbols, black line) and 2000 ppm (closed symbols, gray line) were exposed to instantaneous increases in Ca. Stomatal conductance was allowed to stabilize at each Ca before data was logged. The difference between Gs values at Ca values of 400 and 2000 ppm [CO2] is used to infer stomatal closure. (B) Stomatal closure to darkness – the leaves of plants grown in atmospheres of 400 ppm (black line) and 2000 ppm (gray line) were placed in a cuvette, after Gs had remained stable for 10 min the light in the cuvette and room were simultaneously switched off (represented by the vertical black line). Fifty percent of the maximum and maximum stomatal closure are marked by dashed horizontal lines. The speed of stomatal closure at 50% and maximum stomatal closure are marked by dashed vertical lines labeled a and b, respectively. The lack of stability in Gs values immediately after the cessation of illumination may be an artifact related to changes in the temperature of the leaf cuvette affecting the measurement of relative humidity of the air within the cuvette. For clarity, the points taken to illustrate the determination of stomatal closure are only showed in relation to the plants grown at 400 ppm [CO2] (black lines). Plants grown at 2000 ppm (gray lines) are included to illustrate the impact of [CO2] on stomatal control, with the black arrow indicating the loss of stomatal control incurred by growth at elevated [CO2].

Leaf Gas-Exchange and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis of Photosynthetic Physiology

Response curves of PN to increasing internal sub-stomatal [CO2] (Ci) under a saturating light intensity of 2000 μmol m-2 s-1 (Ca sequence of 350, 250, 150, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1400, 1600, 1800, and 2000 ppm) at a standard cuvette temperature of 25°C were recorded on the same leaves used to assess stomatal control using the same Ciras-2 photosynthesis system. The maximum carboxylation rate of RubisCO (Vcmax), the maximum rate of electron transport for regeneration of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (Jmax) and mesophyll conductance to CO2 (GmCO2) were calculated from the PN/Ci response curves following Ethier and Livingston (2004). The ‘curve fitting’ method of Ethier and Livingston (2004) estimates GmCO2 from the response of PN to increasing partial pressure of CO2 in the sub-stomatal air-space assuming a constant GmCO2 across the range of Ci values (cf. Flexas et al., 2007). Total conductance to CO2 (GtotCO2) was calculated as:

Where GsCO2 is the stomatal conductance to CO2 – in the present manuscript to further aid differentiation between measurement of stomatal conductance to H2O and CO2, Gs H2O is expressed as mmol m-2 s-1, while Gs CO2 is expressed as mol m-2 s-1. The maximum rate of photosynthesis (PN max) was considered to be PN at a saturating light intensity of 2000 μmol m-2 s-1 and [CO2] of 2000 ppm. The maximum (Fv/Fm) and actual (ΦPSII: ΔF/F′m) quantum efficiency of photosystem II was recorded using a Hansatech FMS-2 (saturating pulse of 10,000 μmol m-2 s-2) and dark adaptation clips (Hansatech, King’s Lynn, UK) after 30 min of dark adaptation and exposure to actinic light of 1000 μmol m-2 s-1 for a minimum of 10 min after the first saturating pulse (Genty et al., 1989; Kalaji et al., 2014).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). To test [CO2] treatment effects a one-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in variance between samples. A two-way ANOVA was used to assess species and [CO2] effects on Gsmax (Figure 3). The relative change (Δ) in parameters was expressed as a percentage of the values recorded at 2000 ppm [CO2] relative to control values measured at 400 ppm [CO2]. Linear regression was used to investigate potential relationships between stomatal characteristics such as stomatal pore length and speed of stomatal closure and whether relative changes in stomatal behavior (i.e., Δ Gs change to [CO2] or darkness) were associated with the relative change in photosynthetic physiology.

Results

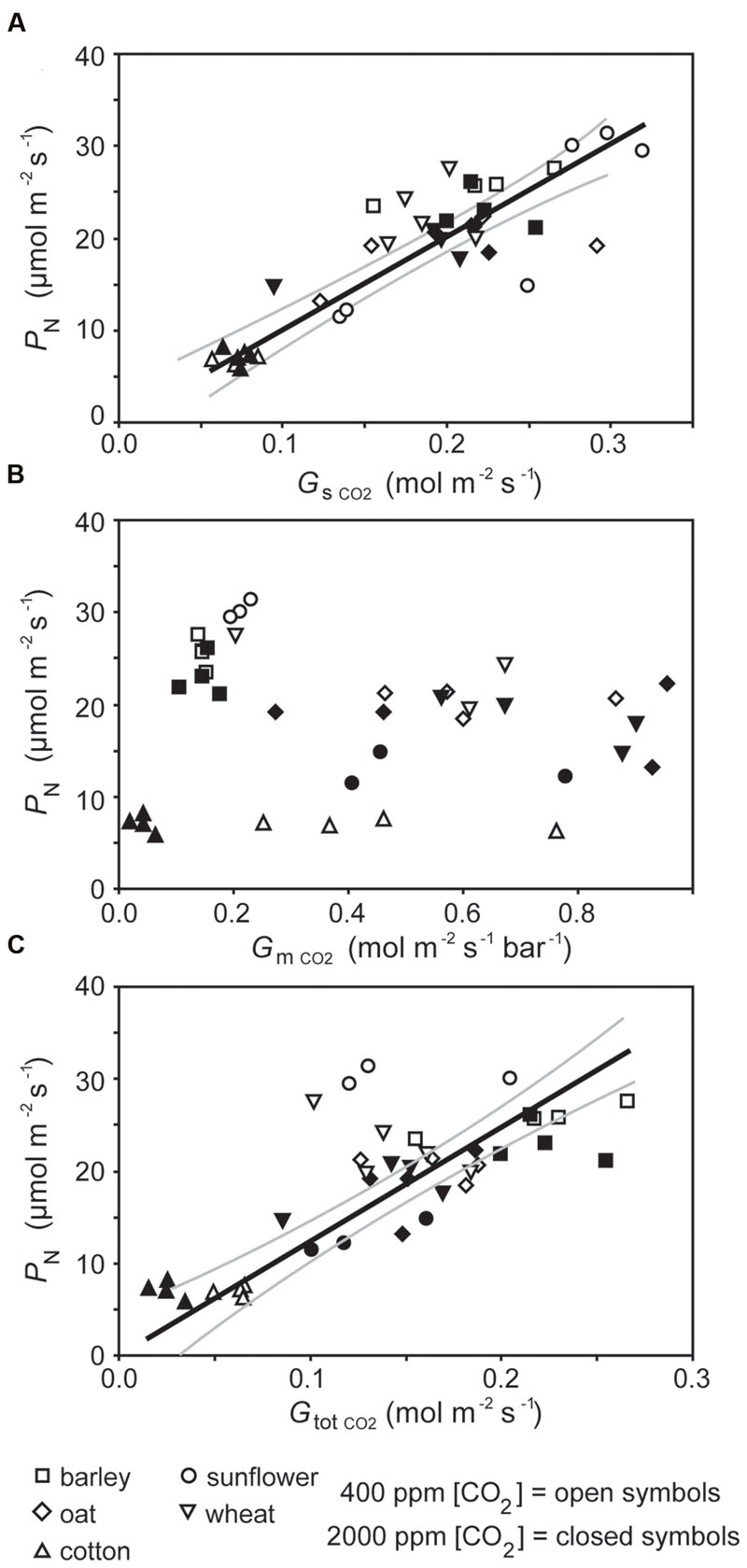

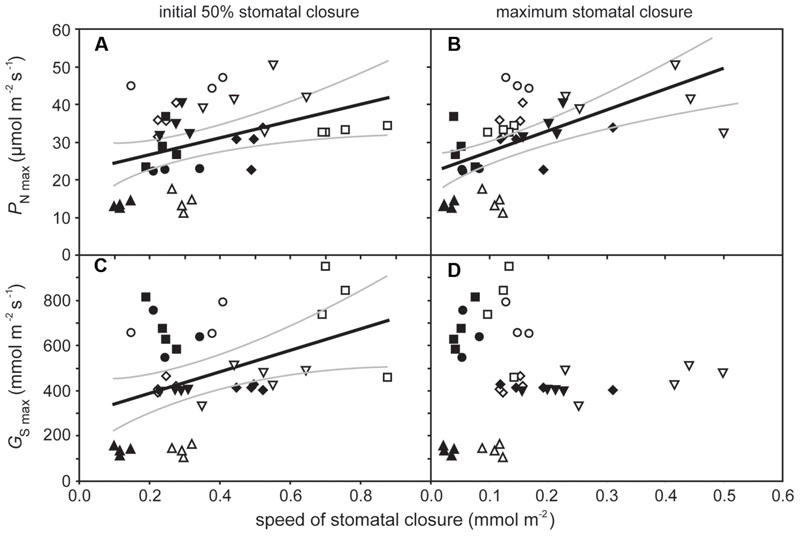

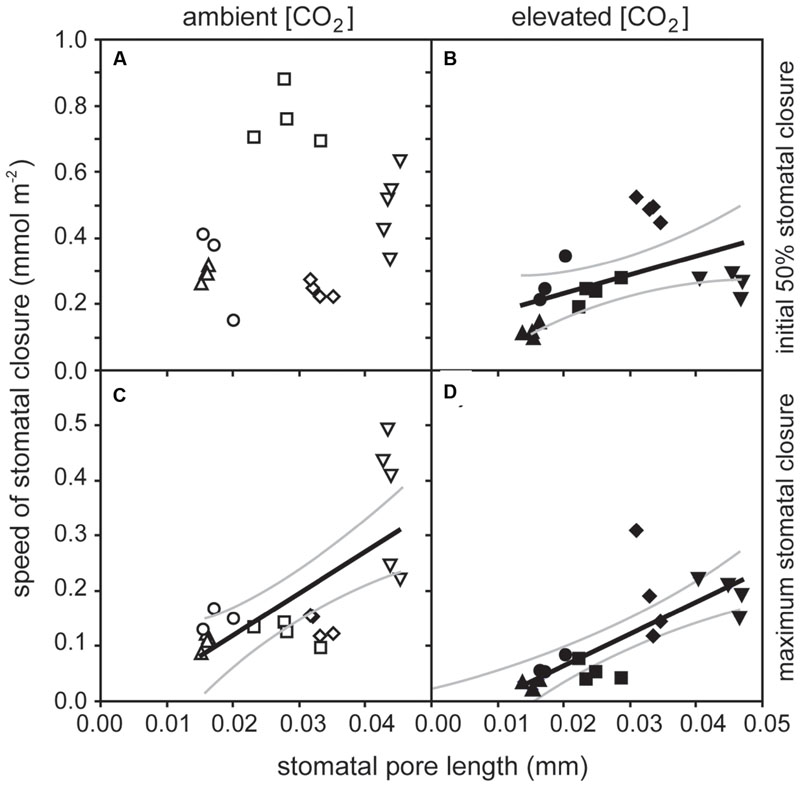

The rate of PN in the five crop species grown in atmospheres of ambient and elevated [CO2] was positively related to GsCO2 and GtotCO2 when measured at a common [CO2] level of 400 ppm (Figure 2). However, PN did not correlate to GmCO2 measured using the curve fitting approach. Stomatal conductance to water vapor was 18.5–48.9% lower at elevated [CO2] in four of the species when measured at their respective growth [CO2] levels. Cotton showed no change in Gs H2O when grown at 400 and 2000 ppm [CO2] (Table 1; Figure 2). Positive relationships were observed between the speed of stomatal closure to darkness and PN max (Figures 3A,B). The maximum rate of stomatal conductance was significantly correlated to the speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% reduction in Gs H2O (Figure 3C), but not to the maximum extent of stomatal closure (Figure 3D). In plants grown at an ambient [CO2] of 400 ppm, no relationship was observed between SPL and the speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% reduction in Gs H2O (Figure 4A). However, a positive relationship was observed between SPL and the speed of stomatal closure to the maximum extent of stomatal closure at ambient [CO2] (Figure 4C). Positive relationships were observed between the speed of stomatal closure and SPL in the five crop plants grown at elevated [CO2] (Figures 4B,D).

FIGURE 2. The relationship between photosynthesis (PN) and (A) stomatal conductance to CO2 (GsCO2; linear regression F1,37 = 107.922; P = 1.607 × 10-12; R2 = 0.863), (B) mesophyll conductance to CO2 (GmCO2; linear regression F1,37 = 0.052; P = 0.821), and (C) total conductance to CO2 (GtotCO2; linear regression F1,37 = 46.763; P = 4.659 × 10-8; R2 = 0.747). Solid black line indicates best fit, gray lines either side indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean.

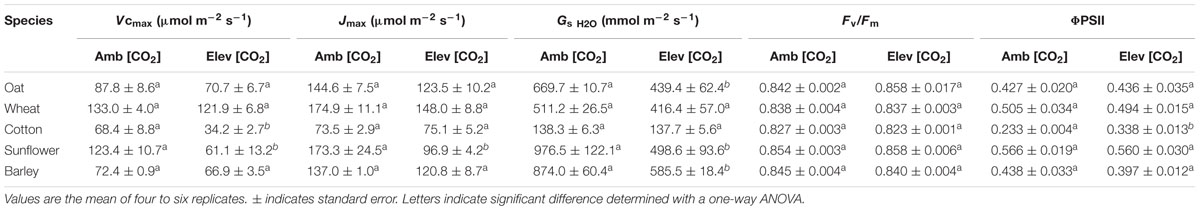

TABLE 1. The effect of growth at ambient (400 ppm) and elevated (2000 ppm) [CO2] on maximum rate of carboxylation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Vcmax), the maximum rate of electron transport required for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate regeneration (Jmax), stomatal conductance of water vapor (GsH2O) and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of the maximum (Fv/Fm) and actual (ΦPSII) quantum efficiency of photosystem II.

FIGURE 3. The relationship between maximum rates of photosynthesis (PN max) and speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% closure (A) (linear regression F1,37 = 6.814; P = 0.0130; R2 = 0.394) and to the maximum extent of stomatal closure, (B) (linear regression F1,37 = 17.654; P = 0.00016; R2 = 0.568); and the relationship between maximum rates of stomatal conductance (Gsmax) and speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% closure, (C) (linear regression F1,37 = 7.235; P = 0.0107; R2 = 0.404) and to the maximum extent of stomatal closure, and (D) (linear regression F1,37 = 0.058; P = 0.811). Solid black line indicates best fit, gray lines either side indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Symbols as in Figure 2.

FIGURE 4. The relationship between the stomatal pore length (SPL) and speed of stomatal closure to darkness: (A) speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% of closure versus SPL of plants grown at 400 ppm [CO2] (linear regression F1,37 = 1.358; P = 0.259); (B) speed of stomatal closure during the initial 50% of closure versus SPL of plants grown at 2000 ppm [CO2] (linear regression F1,37 = 0.0331; P = 5.378; R2 = 0.490); (C) speed of stomatal closure during the time taken to achieve maximum closure versus SPL of plants grown at 400 ppm [CO2] (linear regression F1,37 = 16.304; P = 0.0008; R2 = 0.689), and (D) speed of stomatal closure during the time taken to achieve maximum closure versus SPL of plants grown at 2000 ppm [CO2] (linear regression F1,37 = 24.190; P = 0.0001; R2 = 0.766). Solid black line indicates best fit, gray lines either side indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Symbols as in Figure 2.

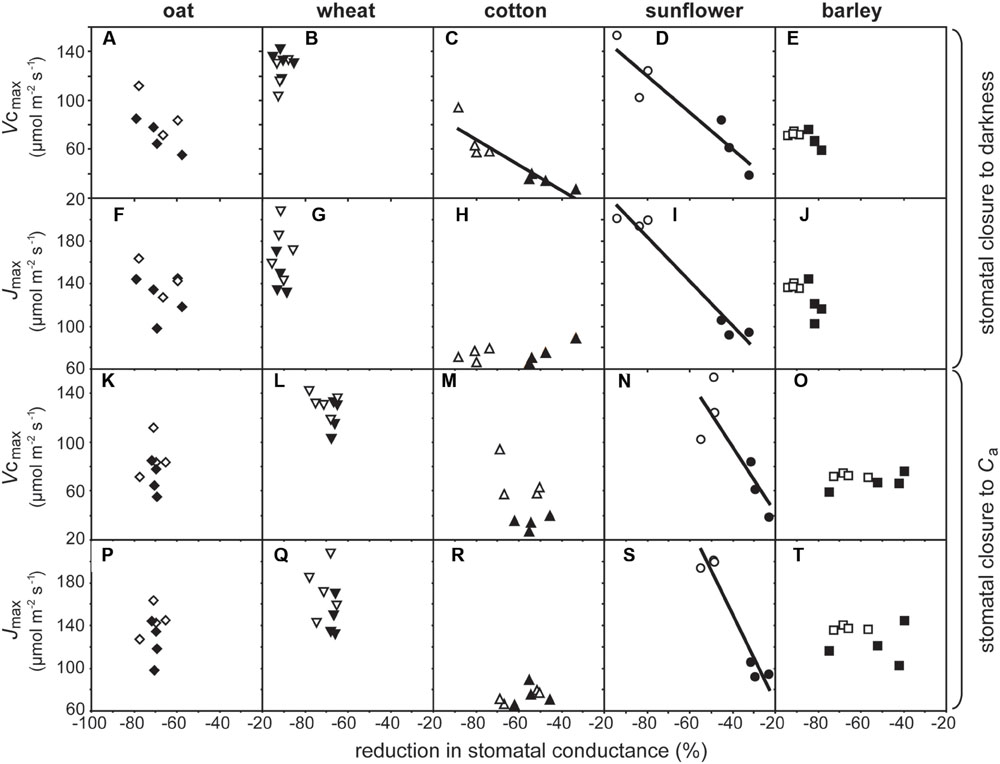

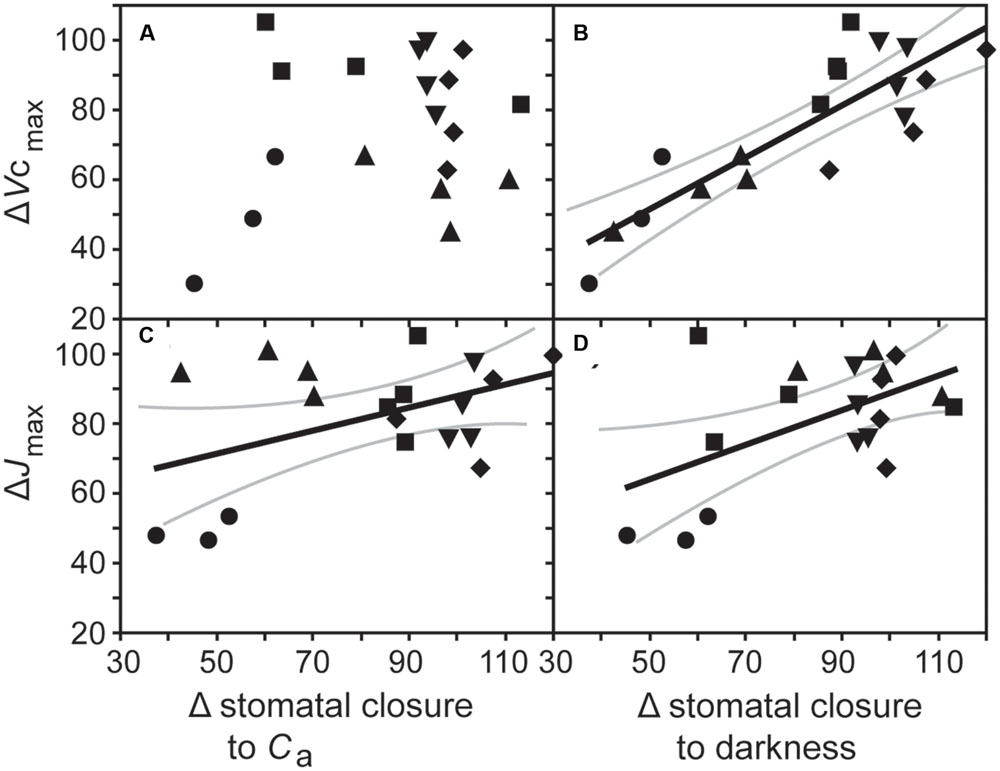

Growth at elevated [CO2] resulted in significant declines in Vcmax in cotton and sunflower (Table 1). This coincided with lower stomatal closure to darkness (Figure 5). Sunflower showed lower Vcmax and Jmax that coincided with impaired stomatal closure to darkness and stomatal sensitivity to Ca; however, ΔVcmax in all five species did not correlate to Δstomatal closure to Ca (Figure 6A). Oat, wheat, and barley did not exhibit any significant correlations between photosynthetic physiology and stomatal control (Figure 5). However, when the relative change in photosynthetic parameters was compared to the relative change in stomatal control a highly significant positive correlation was observed between ΔVcmax and Δstomatal closure to darkness (Figure 6B). In effect, those species that retain Vcmax (i.e., a ΔVcmax close to 100%) also tend to maintain stomatal closure (i.e., a Δstomatal closure to darkness close to 100%) at high [CO2]; while species that exhibit reduced Vcmax at high [CO2] also show lower ability to close stomata in response to the cessation of illumination. Less robust positive correlations were also observed between ΔJmax with Δstomatal closure to [CO2] (Figure 6C) and Δstomatal closure to darkness (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 5. The impact of growth at an elevated [CO2] of 2000 ppm on photosynthetic physiology and stomatal sensitivity to Ca and closure to darkness. Linear regression was used to calculate F and P values are as follows: (A) F1,6 = 2.889, P = 0.140; (B) F1,7 = 0.079, P = 0.787; (C) F1,6 = 29.981, P = 0.00155, R2 = 0.913; (D) F1,4 = 28.643, P = 0.00587, R2 = 0.877; (E) F1,6 = 0.312, P = 0.597; (F) F1,6 = 0.726, P = 0.427; (G) F1,7 = 0.0252, P = 0.878; (H) F1,6 = 1.430, P = 0.277; (I) F1,4 = 81.006, P = 0.0008, R2 = 0.953; (J) F1,6 = 5.604, P = 0.0557; (K) F1,6 = 0.0325, P = 0.863; (L) F1,7 = 1.549, P = 0.253; (M) F1,6 = 1.600, P = 0.253; (N) F1,4 = 9.705, P = 0.0357, R2 = 0.708; (O) F1,6 = 0.312, P = 0.597; (P) F1,6 = 0.108, P = 0.754; (Q) F1,7 = 0.378, P = 0.558; (R) F1,6 = 1.309, P = 0.296; (S) F1,4 = 46.374, P = 0.00243, R2 = 0.921; (T) F1,6 = 0.184, P = 0.682. Symbols as in Figure 2.

FIGURE 6. The relationship between the proportional change in the maximum rate of carboxylation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (ΔVcmax) with (A) the change in stomatal closure to a change in Ca from 400 to 2000 ppm [CO2] (Δstomatal closure to Ca; linear regression F1,17 = 0.819; P = 0.378), and (B) stomatal closure to darkness in plants grown at an elevated [CO2] of 2000 ppm (Δstomatal closure to darkness; linear regression F1,17 = 44.454; P = 3.966 × 10-6; R2 = 0.851), and the relationship between the proportional change in the maximum rate of electron transport required for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate regeneration (ΔJmax) with (C) Δstomatal closure to Ca (linear regression F1,17 = 7.244; P = 0.0154; R2 = 0.547), and (D) Δstomatal closure to darkness (linear regression F1,17 = 4.506; P = 0.0488; R2 = 0.458). Solid black line indicates best fit, gray lines either side indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Symbols as in Figure 2.

Discussion

Co-ordination of Photosynthesis and Stomatal Control

Photosynthesis of the crop plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2] when measured at a common [CO2] was closely related to stomatal and total conductance to CO2 (Figures 2A,C). However, Gm CO2 derived from the curve fitting method (Ethier and Livingston, 2004) did not show any significant relationship to PN either at a common Ca (Figure 2B) or the respective growth [CO2] levels of the plants (data not shown). The curve fitting approach calculates a single Gm value along the PN – Ci curve. The efficacy of this approach is reliant upon Gm remaining constant at a range of Ci values (Tazoe et al., 2009, 2011), however, measurement of Gm using the variable J method of Harley et al. (1992) across a Ci gradient suggests that rates of GmCO2 may not be uniform and instead vary with the availability of CO2 in relation to rates of PN and respiration (Flexas et al., 2007). The curve fitting method has been successfully applied to the determination of GmCO2 in plants grown at identical [CO2] but different levels of water availability (Miyazawa et al., 2008). However, no relationship was observed between PN and GmCO2 of the crop plants grown at different levels of [CO2] in the present study (Figure 2B). This may suggest that there is no effect of growth at elevated [CO2] on GmCO2 in the crop species analyzed as there were limited reductions in photosynthetic capacity of four of the five species due to the free availability of nutrients (Kitao et al., 2015), or a limitation in the effectiveness of the method due to the size of the cuvette employed (2 cm2; Pons et al., 2009). Movement of CO2 within the leaf is unlikely to have affected the PN – Ci curves (Pons et al., 2009), as the species analyzed in this study possess heterobaric leaves (Nikolopoulos et al., 2002).

The speed of stomatal closure showed a positive relationship to PN.max and Gs.max (Figure 3). This suggests that species with high potential rates of PN and Gs require a high degree of stomatal control to reduce transpirative water-loss and prevent desiccation when conditions are not conducive to PN. This relationship may be indicative of natural selective pressures induced by declining [CO2] during the Cenozoic (65 Ma to present; Haworth et al., 2011) and artificial selective pressures during the domestication of crop species (Evans, 1980; Roche, 2015) favoring highly effective physiological stomatal control alongside high rates of PN and Gs. The trend of declining [CO2] during much of the past 65 million years (Berner, 2006) is considered to have favored species with large numbers of small stomata as the most effective arrangement of the epidermal surface to achieve maximum rates of gas exchange (Franks and Beerling, 2009; de Boer et al., 2016) in conjunction with rapid stomatal opening and closing (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Raven, 2014). In contrast to previous observations of a negative relationship between stomatal size and the speed of the adjustment in the size of stomatal aperture in closely related species with identical stomatal complex morphology (Drake et al., 2013), this study showed a positive relationship between stomatal size and the speed of the stomatal response to darkness (Figure 4). However, this positive relationship reflects the diversity in stomatal complex morphologies of the five plants studied. The dicots, cotton, and sunflower, both have stomatal complexes composed of ‘kidney-shaped’ guard cells; whereas the monocot grasses, oat, wheat, and barley, have larger ‘dumb-bell’ type guard cells (Haworth et al., 2015). The dumb-bell stomatal complexes of grasses may open and close more rapidly than kidney-shaped stomatal complexes. Stomatal opening relies upon an increase in guard cell turgor as ions are pumped across cell membranes to reduce water potential; however, to effectively open the larger dumb-bell guard cell pairs there needs to be a corresponding loss of turgor in the surrounding cell epidermal subsidiary cells to accommodate an increase in stomatal aperture (Franks and Farquhar, 2007). This rapid control and co-ordination of changes in cell turgor may account for the generally faster rates of stomatal closure observed in the grasses analyzed in this study (Figure 4), and ability of grasses to support larger stomatal pore apertures than species with kidney-shaped stomatal complexes.

The Effect of Elevated [CO2] on Active Stomatal Behavior

Regulation of stomatal aperture size is achieved through a complex hierarchical sensory and signaling network (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Kim et al., 2010; Merilo et al., 2014). The results of this study (Figure 6) and others (e.g., Heath and Kerstiens, 1997; Heath, 1998; Zeppel et al., 2012) suggest that growth at elevated [CO2] may affect either the network of stomatal sensing/signaling or the physical function of stomata. Physiological stomatal control may occur via a signal from the mesophyll to the guard cells (Mott et al., 2008; Fujita et al., 2013), or as a result of metabolic changes within the guard cells (Talbott and Zeiger, 1998). It is not possible from the present dataset to definitively state whether the reduction in photosynthetic physiology and impaired stomatal function at high [CO2] are causally linked or co-incidental. Quantitative trait loci responsible for PN and stomatal control occur within the same region of the genome in sunflower (Hervé et al., 2001), indicating the importance of their co-ordination in plant responses to environmental change. The mesophyll is the site where the majority of PN occurs and mesophyll PN and Gs are closely linked (Messinger et al., 2006). The results of this study may suggest that the effects on photosynthetic capacity and stomatal control at high [CO2] are associated. Growth at high [CO2] can cause damage (Madsen, 1971), inhibition (Van Oosten et al., 1994), and feedback limitations (Sage et al., 1989) to the photosynthetic physiology. However, the species studied in this experiment all exhibit fairly rapid growth that would reduce the impact of sink limitations (Manderscheid et al., 2010), and did not experience any limitations in nutrient availability that might promote any reduction of photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2] (Farage et al., 1998). Three of the five crops showed no effect of growth at elevated [CO2] on PN – Ci curves, and none of the five crops exhibited lower Fv/Fm or ΦPSII values at the higher [CO2] that might indicate some impairment or loss of performance of PSII corresponding to damage to the thylakoid membranes (Shaw et al., 2014; Kalaji et al., 2016) that may account for the patterns observed in PN and stomatal control reported in this study.

An increase in [CO2] commonly induces a reduction in stomatal aperture in plants with active physiological stomatal control (Morison and Gifford, 1983; Haworth et al., 2013). Separation of the epidermis and mesophyll layers suggests that this is the result of a signal derived from the mesophyll such as sucrose or malate (Mott et al., 2008; Fujita et al., 2013) regulated by carbonic anhydrase within the mesophyll (Hu et al., 2010). An increase in transport of sucrose to the apoplastic space surrounding the guard cells may act as a signal to induce stomatal closure and limit water-loss during episodes where levels of photosynthetic sugar production exceed rates of transport from the photosynthetic organs (Outlaw, 2003). The plants grown at 2000 ppm [CO2] in this study exhibited stomatal sensitivity to an increase in Ca from 400 to 2000 ppm; however, the degree of closure in cotton and sunflower was lower, possibly indicating impairment of the mesophyll to guard cell signal, or physical damage to the stomata constraining the ability to close. The leaves of plants grown at high [CO2] frequently contain greater concentrations of soluble sugars due to CO2-fertilization and the accumulation of photosynthate if the capacity to transport sugars is exceeded (Van Oosten et al., 1994; Paul and Driscoll, 1997). Such an increase in soluble sugars in the apoplast at high [CO2] may impair the efficacy of a sucrose mesophyll derived signal, or the sensitivity of guard cells to apoplastic fluctuations in sucrose concentrations. The concentration of sugars such as sucrose derived from guard cell PN may also play a role in maintaining guard cell turgor after the influx of potassium ions responsible for stomatal opening (Talbott and Zeiger, 1998). Disruption to carbohydrate metabolism may also influence guard and subsidiary cell osmotic balance, thus affecting the mechanics of stomatal opening/closing (e.g., Franks and Farquhar, 2007) and possibly accounting for impaired stomatal control in sunflower and cotton (Figure 5).

Stomatal opening in response to sub-ambient [CO2] occurs in isolated epidermal strips without the mesophyll, but stomatal closure induced by [CO2] levels above ambient requires chemical contact between the mesophyll and epidermal layers, suggesting the operation of a diffusible signal (Fujita et al., 2013). No difference was observed in Gsmax values recorded at a Ca of 50 ppm [CO2] (two-way ANOVA: CO2, F1,38 = 1.580, P = 0.219; species F4,38 = 52.511, P = 7.160 × 10-13) of plants grown at 400 and 2000 ppm [CO2] (Figure 3C). However, Gs sensitivity to an instantaneous increase in [CO2] from 400 to 2000 ppm did alter between species; indicative of differential stomatal control mechanisms to sense and signal sub-ambient [CO2] (Fujita et al., 2013) and the photosynthetic control of [CO2] at higher levels of [CO2] (Messinger et al., 2006). The results of this study suggest that control of Gs by mesophyll PN via Ci is influenced via the effect of growth at elevated [CO2] on photosynthetic physiology in cotton and sunflower with kidney-shaped stomatal complexes (Figure 6). The similarity in stomatal response to a sub-ambient Ca of 50 ppm, but difference in stomatal sensitivity to super-ambient Ca may indicate that growth at elevated [CO2] does not affect the physical aspects of stomatal opening/closing but rather disrupts the photosynthetic control of Gs. In essence, the photosynthetic mesophyll to guard cell signaling mechanism appears to be operating in the same manner, but at high [CO2] the fine control of stomatal behavior is impaired. Stomatal aperture during PN is linked to Ci (Roelfsema et al., 2002). Stomatal conductance in cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium) showed a gradual change when PN was CO2-limited and a more dramatic reduction with Ci when PN was limited by the regeneration of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (Messinger et al., 2006). This may account for the lack of correlation between ΔVcmax and stomatal sensitivity to [CO2] (Figure 6A) and the negative correlation between ΔJmax and Δstomatal closure to [CO2] (Figure 6C) observed in this study; suggesting that alteration of photosynthetic capacity may influence the photosynthetic determination of stomatal aperture in response to fluctuations in Ci.

The pronounced reduction in the effectiveness of stomatal closure to darkness with Vcmax (Figure 6B) may also be suggestive of a link between PN and physiological stomatal behavior or impaired physical operation of the stomata. A diverse range of stomatal morphologies (Franks and Farquhar, 2007) and physiological behaviors (Haworth et al., 2013, 2015) are observed in evolutionarily diverse plants. The species utilized in this study all exhibit active physiological behavior (Haworth et al., 2015), but possess contrasting stomatal morphologies. The monocot grass species with dumb-bell guard cells generally retained the ability to close stomata, while the kidney-shaped stomata of the two dicots closed less effectively at high [CO2] (Figure 6C). Dumb-bell guard cells exhibit larger and faster changes in turgor than kidney-shaped guard cells (Franks and Farquhar, 2007). The guard cells of grasses do not possess chloroplasts (Brown and Johnson, 1962) and possibly reply upon the movement of potassium for stomatal opening (Fairley-Grenot and Assmann, 1992). To accommodate the rapid and large change in dumb-bell guard cell turgor, the surrounding subsidiary cells also undergo osmotic adjustment (Franks and Farquhar, 2007). This may suggest that the differential effect of elevated [CO2] on stomata of grasses and dicots found in this is due to differences in the biochemistry of stomatal opening related to the presence/absence of guard cell chloroplasts, stomatal signaling or photosynthetic control of stomatal aperture.

Implications of Reduced Stomatal Control at High [CO2]

The results of this study suggest that one unexpected impact of elevated [CO2] may be a loss of stomatal function in some C3 herbaceous crop species. This impaired stomatal control corresponded to reduced carboxylation capacity, consistent with linkage between Gs and PN. Growth at elevated [CO2] generally reduced Gs H2O (Table 1). This lower Gs H2O was not associated with a decrease in stomatal density, but a reduction in stomatal aperture via physiological stomatal control (Haworth et al., 2015). Under normal growth conditions this lower Gs H2O will result in reduced water-loss and correspondingly greater WUE, consistent with observations of enhanced WUE in other experimental studies of elevated [CO2] (Centritto et al., 2002; Wullschleger et al., 2002; Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007). However, loss of stomatal function at elevated [CO2] may impair the ability of crop plants with active physiological stomatal behavior to exert stomatal control in the event of a change in growth conditions. Specifically, the reduced ability of stomata to close at elevated [CO2] may have significant implications for the capacity of crops to tolerate drought and heat stress in the future (e.g., Killi et al., 2016) and warranting further experimental investigation.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of elevated [CO2] on stomatal control by using a very high [CO2] level of 2000 ppm. This concentration is beyond the range of the IPCC worst case scenario (IPCC, 2007), but not above levels of [CO2] that have occurred over Earth history since the origination of vascular plants (e.g., Berner, 2009; Haworth et al., 2011). To investigate the loss of stomatal function under more realistic levels of [CO2] for the next 50–100 years further work should be undertaken in controlled environment chambers and free air CO2 enrichment (FACE) systems. However, many FACE systems do not increase [CO2] at night for economic reasons, instead operating enrichment only during daylight hours when PN occurs. In terms of gauging the effect of elevated [CO2] on stomatal control it would be necessary for the plants to experience the most realistic simulation of future atmospheric conditions possible via continuous enrichment of [CO2] levels. The number and duration of heat-waves and drought events are predicted to increase in the future (e.g., Schär et al., 2004; Vautard et al., 2007). The capacity of crop plants to respond to and resist these adverse growth conditions is largely dependent upon effective stomatal control (Killi et al., 2016). At elevated [CO2], WUE may be higher and delay/mitigate the impact of drought (Wall, 2001; Wullschleger et al., 2002), but the results of our study and that of Heath and Kerstiens (1997) suggests that at severe drought the loss of stomatal function in C3 plants with kidney-shaped stomatal complexes could impair tolerance to drought. Further experimental work at [CO2] levels equivalent to those predicted in the next 100 years is required to assess whether the loss of stomatal control at high [CO2] may have negative implications for food security in a water-limited world.

Author Contributions

MH and AR: Designed the experiments. MH, DK, and AM: Conducted the experiments. MH, DK, and MC: Processed data. MH, DK, AM, AR, and MC: Wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from an EU Marie Curie IEF (2010-275626) and the EU FP7 project 3–4 (289582). The comments of two anonymous reviewers significantly improved this manuscript.

References

Ainsworth, E. A., and Rogers, A. (2007). The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01641.x

Berner, R. A. (2006). GEOCARBSULF: a combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5653–5664. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.11.032

Berner, R. A. (2009). Phanerozoic atmospheric oxygen: new results using the geocarbsulf model. Am. J. Sci. 309, 603–606. doi: 10.2475/07.2009.03

Brown, W. V., and Johnson, C. (1962). The fine structure of the grass guard cell. Am. J. Bot. 49, 110–115. doi: 10.2307/2439025

Bunce, J. A. (2000). Acclimation of photosynthesis to temperature in eight cool and warm climate herbaceous C3 species: temperature dependence of parameters of a biochemical photosynthesis model. Photosynth. Res. 63, 59–67. doi: 10.1023/A:1006325724086

Caird, M. A., Richards, J. H., and Donovan, L. A. (2007). Night-time stomatal conductance and transpiration in C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiol. 143, 4–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092940

Centritto, M., Loreto, F., and Chartzoulakis, K. (2003). The use of low [CO2] to estimate diffusional and non-diffusional limitations of photosynthetic capacity of salt-stressed olive saplings. Plant Cell Environ. 26, 585–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00993.x

Centritto, M., Lucas, M. E., and Jarvis, P. G. (2002). Gas exchange, biomass, whole-plant water-use efficiency and water uptake of peach (Prunus persica) seedlings in response to elevated carbon dioxide concentration and water availability. Tree Physiol. 22, 699–706. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.10.699

Centritto, M., Magnani, F., Lee, H. S., and Jarvis, P. G. (1999). Interactive effects of elevated [CO2] and drought on cherry (Prunus avium) seedlings II. Photosynthetic capacity and water relations. New Phytol. 141, 141–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00326.x

Chater, C., Gray, J. E., and Beerling, D. J. (2013). Early evolutionary acquisition of stomatal control and development gene signalling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 16, 638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.013

Ciais, P., Reichstein, M., Viovy, N., Granier, A., Ogée, J., Allard, V., et al. (2005). Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature03972

de Boer, H. J., Price, C. A., Wagner-Cremer, F., Dekker, S. C., Franks, P. J., and Veneklaas, E. J. (2016). Optimal allocation of leaf epidermal area for gas exchange. New Phytol. 210, 1219–1228. doi: 10.1111/nph.13929

Donovan, L., Linton, M., and Richards, J. (2001). Predawn plant water potential does not necessarily equilibrate with soil water potential under well-watered conditions. Oecologia 129, 328–335. doi: 10.1007/s004420100738

Drake, P. L., Froend, R. H., and Franks, P. J. (2013). Smaller, faster stomata: scaling of stomatal size, rate of response, and stomatal conductance. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 495–505. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers347

Engineer, C. B., Hashimoto-Sugimoto, M., Negi, J., Israelsson-Nordström, M., Azoulay-Shemer, T., Rappel, W.-J., et al. (2016). CO2 sensing and CO2 regulation of stomatal conductance: advances and open questions. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.08.014

Ethier, G. J., and Livingston, N. J. (2004). On the need to incorporate sensitivity to CO2 transfer conductance into the Farquhar–von Caemmerer–Berry leaf photosynthesis model. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 137–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01140.x

Evans, L. T. (1980). The natural history of crop yield: a combination of improved varieties of crop plants and technological innovations continues to increase productivity, but the highest yields are approaching limits set by biological constraints. Am. Sci. 68, 388–397.

Fairley-Grenot, K., and Assmann, S. (1992). Whole-cell K+ current across the plasma membrane of guard cells from a grass: Zea mays. Planta 186, 282–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00196258

Farage, P. K., McKee, I. F., and Long, S. P. (1998). Does a low nitrogen supply necessarily lead to acclimation of photosynthesis to elevated CO2? Plant Physiol. 118, 573–580. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.573

Fischer, R., Rees, D., Sayre, K., Lu, Z.-M., Condon, A., and Saavedra, A. L. (1998). Wheat yield progress associated with higher stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate, and cooler canopies. Crop Sci. 38, 1467–1475. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1998.0011183X003800060011x

Flexas, J., Bota, J., Escalona, J. M., Sampol, B., and Medrano, H. (2002). Effects of drought on photosynthesis in grapevines under field conditions: an evaluation of stomatal and mesophyll limitations. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 461–471. doi: 10.1071/PP01119

Flexas, J., Diaz-Espejo, A., Galmés, J., Kaldenhoff, R., Medrano, H., and Ribas-Carbo, M. (2007). Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1284–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01700.x

Flexas, J., and Medrano, H. (2002). Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C3 plants: stomatal and non–stomatal limitations revisited. Ann. Bot. 89, 183–189. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf027

Franks, P. J., and Beerling, D. J. (2009). CO2 forced evolution of plant gas exchange capacity and water-use efficiency over the Phanerozoic. Geobiology 7, 227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00193.x

Franks, P. J., and Farquhar, G. D. (2007). The mechanical diversity of stomata and its significance in gas-exchange control. Plant Physiol. 143, 78–87. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.089367

Fujita, T., Noguchi, K., and Terashima, I. (2013). Apoplastic mesophyll signals induce rapid stomatal responses to CO2 in Commelina communis. New Phytol. 199, 395–406. doi: 10.1111/nph.12261

Genty, B., Briantais, J.-M., and Baker, N. R. (1989). The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 990, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80016-9

Gu, J., Yin, X., Stomph, T. J., and Struik, P. C. (2014). Can exploiting natural genetic variation in leaf photosynthesis contribute to increasing rice productivity? A simulation analysis. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 22–34. doi: 10.1111/pce.12173

Harley, P. C., Loreto, F., Dimarco, G., and Sharkey, T. D. (1992). Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol. 98, 1429–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1429

Haworth, M., Elliott-Kingston, C., and McElwain, J. C. (2011). Stomatal control as a driver of plant evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 2419–2423. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err086

Haworth, M., Elliott-Kingston, C., and McElwain, J. (2013). Co-ordination of physiological and morphological responses of stomata to elevated [CO2] in vascular plants. Oecologia 171, 71–82. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2406-9

Haworth, M., Killi, D., Materassi, A., and Raschi, A. (2015). Co-ordination of stomatal physiological behavior and morphology with carbon dioxide determines stomatal control. Am. J. Bot. 102, 677–688. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400508

Haworth, M., Moser, G., Raschi, A., Kammann, C., Grünhage, L., and Müller, C. (2016). Carbon dioxide fertilisation and supressed respiration induce enhanced spring biomass production in a mixed species temperate meadow exposed to moderate carbon dioxide enrichment. Funct. Plant Biol. 43, 26–39.

Heath, J. (1998). Stomata of trees growing in CO2-enriched air show reduced sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit and drought. Plant Cell Environ. 21, 1077–1088. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00366.x

Heath, J., and Kerstiens, G. (1997). Effects of elevated CO2 on leaf gas exchange in beech and oak at two levels of nutrient supply: consequences for sensitivity to drought in beech. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 57–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-13.x

Hervé, D., Fabre, F., Berrios, E. F., Leroux, N., Al Chaarani, G., Planchon, C., et al. (2001). QTL analysis of photosynthesis and water status traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) under greenhouse conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1857–1864. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1857

Hetherington, A. M., and Woodward, F. I. (2003). The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424, 901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843

Hinckley, T. M., Lassoie, J. P., and Running, S. W. (1978). Temporal and spatial variations in the water status of forest trees. For. Sci. 24, 1–72.

Hu, H., Boisson-Dernier, A., Israelsson-Nordstrom, M., Bohmer, M., Xue, S., Ries, A., et al. (2010). Carbonic anhydrases are upstream regulators of CO2 controlled stomatal movements in guard cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 87–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb2009

IPCC (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kalaji, H., and Nalborczyk, E. (1991). Gas exchange of barley seedlings growing under salinity stress. Photosynthetica 25, 197–202.

Kalaji, H. M., Jajoo, A., Oukarroum, A., Brestic, M., Zivcak, M., Samborska, I. A., et al. (2016). Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 38, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11738-016-2113-y

Kalaji, H. M., Schansker, G., Ladle, R. J., Goltsev, V., Bosa, K., Allakhverdiev, S. I., et al. (2014). Frequently asked questions about in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence: practical issues. Photosynth. Res. 122, 121–158. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-0024-6

Killi, D., Bussotti, F., Raschi, A., and Haworth, M. (2016). Adaptation to high temperature mitigates the impact of water deficit during combined heat and drought stress in C3 sunflower and C4 maize varieties with contrasting drought tolerance. Physiol. Plant. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12490 [Epub ahead of print].

Kim, T.-H., Böhmer, M., Hu, H., Nishimura, N., and Schroeder, J. I. (2010). Guard cell signal transduction network: advances in understanding abscisic acid, CO2 and Ca2+ signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 561–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112226

Kitao, M., Yazaki, K., Kitaoka, S., Fukatsu, E., Tobita, H., Komatsu, M., et al. (2015). Mesophyll conductance in leaves of Japanese white birch (Betula platyphylla var. japonica) seedlings grown under elevated CO2 concentration and low N availability. Physiol. Plant. 155, 435–445. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12335

Lauteri, M., Haworth, M., Serraj, R., Monteverdi, M. C., and Centritto, M. (2014). Photosynthetic diffusional constraints affect yield in drought stressed rice cultivars during flowering. PLoS ONE 9:e109054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109054

Madsen, E. (1971). Cytological changes due to the effect of carbon dioxide concentration on the accumulation of starch in chloroplasts of tomato leaves. R. Vet. Agric. Univ. Yearb. 191–194.

Manderscheid, R., Pacholski, A., and Weigel, H.-J. (2010). Effect of free air carbon dioxide enrichment combined with two nitrogen levels on growth, yield and yield quality of sugar beet: evidence for a sink limitation of beet growth under elevated CO2. Eur. J. Agron. 32, 228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2009.12.002

Materassi, A., Fasano, G., and Arca, A. (2005). Climatic chamber for plant physiology: a new project concept. Riv. Ingegneria Agrar. (Italy) 4, 79–87.

Meidner, H., and Mansfield, T. A. (1965). Stomatal responses to illumination. Biol. Rev. 40, 483–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1965.tb00813.x

Merilo, E., Jõesaar, I., Brosché, M., and Kollist, H. (2014). To open or to close: species-specific stomatal responses to simultaneously applied opposing environmental factors. New Phytol. 202, 499–508. doi: 10.1111/nph.12667

Messinger, S. M., Buckley, T. N., and Mott, K. A. (2006). Evidence for involvement of photosynthetic processes in the stomatal response to CO2. Plant Physiol. 140, 771–778. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073676

Miyazawa, S.-I., Yoshimura, S., Shinzaki, Y., Maeshima, M., and Miyake, C. (2008). Deactivation of aquaporins decreases internal conductance to CO2 diffusion in tobacco leaves grown under long-term drought. Funct. Plant Biol. 35, 553–564. doi: 10.1071/FP08117

Morison, J. I., and Gifford, R. M. (1983). Stomatal sensitivity to carbon dioxide and humidity a comparison of two C3 and two C4 grass species. Plant Physiol. 71, 789–796. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.4.789

Mott, K. A., Sibbernsen, E. D., and Shope, J. C. (2008). The role of the mesophyll in stomatal responses to light and CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01845.x

Nikolopoulos, D., Liakopoulos, G., Drossopoulos, I., and Karabourniotis, G. (2002). The relationship between anatomy and photosynthetic performance of heterobaric leaves. Plant Physiol. 129, 235–243. doi: 10.1104/pp.010943

Outlaw, W. H. (2003). Integration of cellular and physiological functions of guard cells. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 22, 503–529. doi: 10.1080/713608316

Paul, M., and Driscoll, S. (1997). Sugar repression of photosynthesis: the role of carbohydrates in signalling nitrogen deficiency through source: sink imbalance. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 110–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-17.x

Pons, T. L., Flexas, J., von Caemmerer, S., Evans, J. R., Genty, B., Ribas-Carbo, M., et al. (2009). Estimating mesophyll conductance to CO2: methodology, potential errors, and recommendations. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2217–2234. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp081

Roche, D. (2015). Stomatal conductance is essential for higher yield potential of C3 crops. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 34, 429–453. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2015.1023677

Roelfsema, M. R. G., Hanstein, S., Felle, H. H., and Hedrich, R. (2002). CO2 provides an intermediate link in the red light response of guard cells. Plant J. 32, 65–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01403.x

Sage, R. F., Sharkey, T. D., and Seemann, J. R. (1989). Acclimation of photosynthesis to elevated CO2 in five C3 species. Plant Physiol. 89, 590–596. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.2.590

Schär, C., Vidale, P. L., Lüthi, D., Frei, C., Häberli, C., Liniger, M. A., et al. (2004). The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 427, 332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature02300

Shah, N., and Paulsen, G. (2003). Interaction of drought and high temperature on photosynthesis and grain-filling of wheat. Plant Soil 257, 219–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1026237816578

Shaw, A. K., Ghosh, S., Kalaji, H. M., Bosa, K., Brestic, M., Zivcak, M., et al. (2014). Nano-CuO stress induced modulation of antioxidative defense and photosynthetic performance of Syrian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 102, 37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.02.016

Stratonovitch, P., and Semenov, M. A. (2015). Heat tolerance around flowering in wheat identified as a key trait for increased yield potential in Europe under climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 3599–3609. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv070

Talbott, L. D., and Zeiger, E. (1998). The role of sucrose in guard cell osmoregulation. J. Exp. Bot. 49, 329–337. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/49.suppl_1.329

Tazoe, Y., von Caemmerer, S., Badger, M. R., and Evans, J. R. (2009). Light and CO2 do not affect the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in wheat leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2291–2301. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp035

Tazoe, Y., Von Caemmerer, S., Estavillo, G. M., and Evans, J. R. (2011). Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 580–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02264.x

Van Oosten, J. J., Wilkins, D., and Besford, R. T. (1994). Regulation of the expression of photosynthetic nuclear genes by CO2 is mimicked by regulation by carbohydrates–a mechanism for the acclimation of photosynthesis to high CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 17, 913–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1994.tb00320.x

Van Vuuren, M. M. I., Robinson, D., Fitter, A. H., Chasalow, S. D., Williamson, L., and Raven, J. A. (1997). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 and soil water availability on root biomass, root length, and N, P and K uptake by wheat. New Phytol. 135, 455–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00682.x

Vautard, R., Yiou, P., D’andrea, F., De Noblet, N., Viovy, N., Cassou, C., et al. (2007). Summertime European heat and drought waves induced by wintertime mediterranean rainfall deficit. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L07711. doi: 10.1029/2006GL028001

Wall, G. W. (2001). Elevated atmospheric CO2 alleviates drought stress in wheat. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 87, 261–271. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00170-0

Wong, S. C., Cowan, I. R., and Farquhar, G. D. (1979). Stomatal conductance correlates with photosynthetic capacity. Nature 282, 424–426. doi: 10.1038/282424a0

Wullschleger, S. D., Tschaplinski, T. J., and Norby, R. J. (2002). Plant water relations at elevated CO2–implications for water-limited environments. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 319–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00796.x

Zelitch, I. (1982). The close relationship between net photosynthesis and crop yield. Bioscience 32, 796–802. doi: 10.2307/1308973

Keywords: stomatal behavior, stomatal evolution, stomatal sensitivity, drought, photosynthetic down-regulation, food security

Citation: Haworth M, Killi D, Materassi A, Raschi A and Centritto M (2016) Impaired Stomatal Control Is Associated with Reduced Photosynthetic Physiology in Crop Species Grown at Elevated [CO2]. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1568. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01568

Received: 30 May 2016; Accepted: 05 October 2016;

Published: 25 October 2016.

Edited by:

Peter Thorburn, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, AustraliaReviewed by:

Hazem M. Kalaji, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, PolandAlex Wu, University of Queensland, Australia

Copyright © 2016 Haworth, Killi, Materassi, Raschi and Centritto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Haworth, aGF3b3J0aEBpdmFsc2EuY25yLml0

Matthew Haworth

Matthew Haworth Dilek Killi

Dilek Killi Alessandro Materassi3

Alessandro Materassi3 Mauro Centritto

Mauro Centritto