- 1United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Vegetable Crops Research Unit, Madison, WI, USA

- 2Department of Horticulture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA

The natural history of epiphytic plant species has been extensively studied. However, little is known about the physiology and genetics of epiphytism. This is due to difficulties associated with growing epiphytic plants and the lack of tools for genomics studies and genetic manipulations. In this study, tubers were generated from 223 accessions of 42 wild potato Solanum species, including the epiphytic species S. morelliforme and its sister species S. clarum. Lyophilized samples were analyzed for 12 minerals using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. Mineral levels in tubers of S. morelliforme and S. clarum were among the highest for 10 out of the 12 elements evaluated. These two wild potato relatives are native to southern Mexico and Central America and live as epiphytes or in epiphytic-like conditions. We propose the use of S. morelliforme and S. clarum as model organisms for the study of mineral uptake efficiency. They have a short life cycle, can be propagated vegetatively via tubers or cuttings, and can be easily grown in controlled environments. In addition, genome sequence data are available for potato. Transgenic manipulations and somatic fusions will allow the movement of genes from these epiphytes to cultivated potato.

Introduction

Epiphytes encompass an unusual group of plant species that grow on other plants, typically in the crowns of trees, without parasitizing them. They are considered one of the most threatened plant groups (Mondragon et al., 2015). The 27,614 species of vascular epiphytes account for 9% of extant vascular plant diversity (Zotz, 2013). Vascular epiphytes range from ferns to flowering orchids and bromeliads. The biology and ecology of these unique plants has been extensively studied (reviewed by Mondragon et al., 2015). However, the physiology and genetics of epiphytism has received much less attention.

There are two main types of vascular epiphytes (Cardelús and Mack, 2010). The first acquires nutrients through organic debris that accumulates on the branches of host plants. This decaying organic debris, called crown humus, accumulates slowly over many years, forming a medium in which epiphytes, such as some fern species, can root and absorb nutrients (Jenik, 1973). Other epiphytes, such as bromeliads, obtain nutrients from the atmosphere through foliar feeding.

The main constraints on epiphytic growth and function are water acquisition, mineral procurement and utilization, and light exposure (Benzing, 1990; Laube and Zotz, 2003). Optimal growth requires the uptake of adequate levels of all essential minerals. The quality of the nutrient medium in the forest canopy can be highly variable and dependent on altitude, climate, humidity, and position above ground level. However, it is generally assumed that epiphytic habitats tend to be low in nutrients and sporadic in water supply (Laube and Zotz, 2003; Zotz, 2004; Zotz and Richter, 2006; Winkler and Zotz, 2008; Cardelús, 2009; Cardelús et al., 2009; Zotz and Asshoff, 2010).

Epiphytes have evolved to grow in low input environments. Adaptations to low mineral environments include slow growth rate, small stature, asexual reproduction, sexual reproduction with a minimum expenditure of non-recoverable mineral nutrients in seed and fruit production, resistance to mineral loss by leaching, tolerance of low mineral levels in living tissue, the capacity to substitute one element for another in metabolism, the ability to exploit mineral sources normally unavailable to higher plants, and the ability to absorb and sequester minerals in dilute solutions (Benzing, 1990; Schmidt and Zotz, 2002; Winkler and Zotz, 2008). The latter strategy is of most interest to scientists seeking to improve nutrient use efficiency in plants. Despite an abundance of research detailing the unique adaptations of epiphytes and their environments, the literature on mineral uptake is largely descriptive, and the genetic and physiological mechanisms of these processes are not well-understood (Luttge, 1989; Benzing, 1990; Zotz and Hietz, 2001; Rains et al., 2003; Zotz, 2004).

An improved understanding of the molecular basis of mineral uptake in epiphytes would contribute to many fields, including conservation biology, germplasm development, crop breeding, and plant physiology. This paper presents two wild potato (Solanum section Petota) relatives as model systems for the identification and characterization of genes responsible for nutrient acquisition and accumulation.

Materials and Methods

In October, 2007, true potato seed from 134 accessions (populations) of 42 wild Solanum species was obtained from the U.S. Potato Genebank (NRSP-6). Fifty seeds of each accession were sown in soilless potting mix (Pro-Mix™) and 3 weeks later, 15 seedlings per accession were transplanted into individual 5 cm pots. After another 3 weeks of growth, seedlings were transplanted into 10 cm pots. They were grown under high intensity (1000 w high pressure sodium) lights with an 18 h photoperiod. Day/night temperatures were 20C/16C. Plants were watered as needed, typically daily. Osmocote slow release fertilizer (19-6-12) was incorporated into the potting mix during transplanting. In January, photoperiod was reduced to 12 h to induce tuberization. Six weeks later, the trial was harvested and the largest tuber from each of the 15 plants in an accession was collected and all 15 tubers were placed in a paper bag. After 3 days at room temperature, tubers were immersed in liquid nitrogen and then placed in a −80°C freezer. Tubers were lyophilized and ground using a mortar and pestle. Tuber tissue from the 15 plants in each accession was combined for mineral analysis. For each sample, 500 mg of dried tuber tissue and 5 mL of concentrated nitric acid were added to a 50-mL Folin digestion tube. The mixture was heated to 120–130°C for 14–16 h and then treated with hydrogen peroxide. After digestion, the sample was diluted to 50 mL. This solution was analyzed for mineral content using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Model IRIS Advantage, Thermo Jarrell Ash, Waltham, MA). The trial was repeated in 2008 with 89 additional accessions.

Results and Discussion

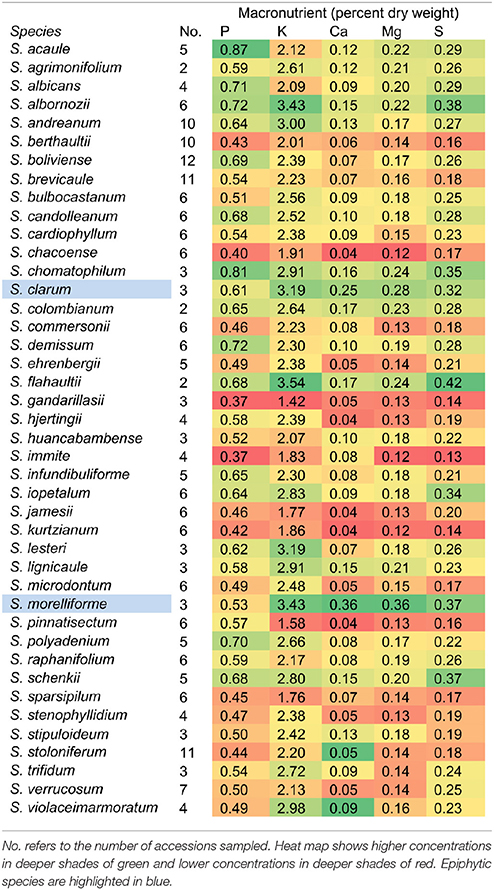

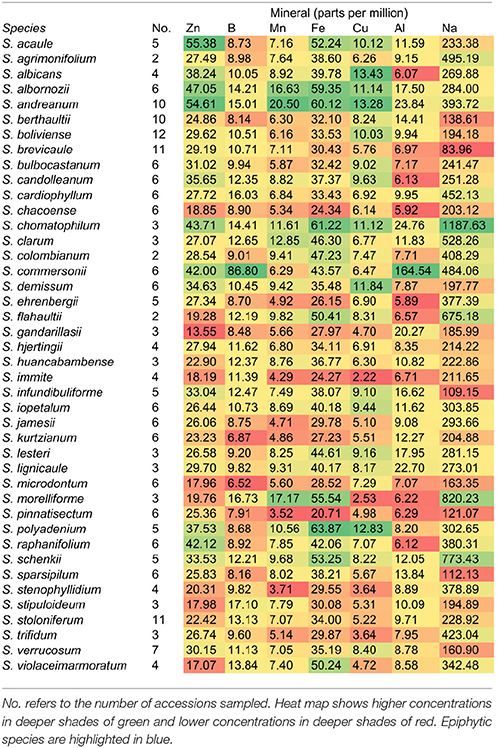

This study was initiated as a survey of mineral uptake capacity in a geographically and taxonomically diverse set of wild Solanum species. However, after the mineral data were collected and species were compared, S. morelliforme and S. clarum stood out as exceptional for tuber mineral content. Tuber mineral levels, averaged by species, are presented in Table 1. Supplementary Table 1 provides maximum and Supplementary Table 2 provides minimum tuber mineral levels. At this point, and realizing that these species are epiphytes or found in epiphytic-like conditions, we began to consider the possibility that they could serve as model species for studies of mineral nutrient uptake.

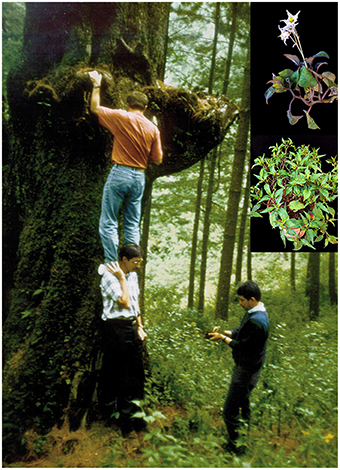

Solanum morelliforme Bitter & Muench is a diploid (2n = 24), self-incompatible, epiphytic member of Solanum section Petota. It is widespread throughout central Mexico (southern Jalisco to Querétato and Veracruz), south to southern Honduras, growing from 1870 to 3050 m in elevation, flowering and fruiting from July through October. A strikingly disjunct (approximately 4000 km) population was recently discovered in Bolivia, representing the first record of this species in South America, and the first species in the section growing in both North and Central America and in South America (Simon et al., 2011). Solanum morelliforme is distinctive with its simple leaves, relatively small stature (stems 2–3 mm wide at base, 0.1–0.5 m tall), epiphytic habit, and is impossible to be confused with any other wild potato. Solanum morelliforme is the only epiphytic wild potato, growing on horizontal branches of mature Arbutus L., cyprus, elm, juniper, pine, or oak trees, often rooted in moss and organic litter (Spooner et al., 2004; Figure 1). Field studies in Mexico and Central America (Spooner et al., 1998, 2000) showed that it is difficult to find in previously documented localities that had been logged and reforested, suggesting that its range is being reduced by deforestation.

Figure 1. Collecting epiphytic Solanum morelliforme. Inserts are photos of S. clarum (upper) and S. morelliforme.

Solanum morelliforme is most similar morphologically to S. clarum Correll, its sister species (Spooner et al., 2004). Solanum clarum is distributed in southern extreme Mexico and Guatemala, from 2740 to 3800 m in elevation, flowering and fruiting from July through November. Like S. morelliforme, S. clarum is a diploid (2n = 24). Although not technically an epiphytic species, it occasionally grows in trees but more commonly in epiphytic-like conditions, in shade, in upland pine and fir forests, frequently associated with Acaena elongata L., Alchemilla pectinata H. B. K., or Pernettya ciliata (Schltdl. & Charn) (Spooner et al., 2004).

The three S. clarum accessions and one S. morelliforme accession were collected in Guatemala. The remaining two S. morelliforme accessions originate from Mexico. Passport data reveal that one of the S. clarum accessions and two of the S. morelliforme accessions were growing as epiphytes when they were collected. They have many characteristics of plants adapted to mineral-deficient environments including small stature, asexual reproduction via tubers, small fruits bearing few seeds, and infrequent sexual reproduction (Spooner et al., 2004).

The two species proposed as models in this paper differ in that S. morelliforme is typically found in trees, while S. clarum may be in trees or in the litter surrounding trees. Attempts have been made to distinguish among gradations in the proportion of plants of an epiphytic species that are found growing in trees (Zotz, 2013). However, the environment on a fallen tree or the mossy low branches of a tree is often very similar to that of both the moss-covered ground and an intact mature tree.

Because nutrient supply is low and irregular in crown humus, epiphytes must possess highly efficient mineral uptake and utilization mechanisms (Benzing and Renfrow, 1974). In addition, when provided with the opportunity, they may take up minerals in excess of current needs and store them for future use, a phenomenon called luxury consumption (Benzing and Renfrow, 1980; Chapin, 1980; Benzing, 2000). Storage organs, such as the potato tubers evaluated in this study, provide a natural mechanism for accumulating and storing mineral nutrients.

Phosphorus is often a limiting nutrient for many vascular epiphytes in tropical forests Epiphytic bromeliads have been shown to efficiently take up phosphorus and then store it for later use (Winkler and Zotz, 2008; Zotz and Asshoff, 2010). The two Solanum epiphyte and epiphytic-like species in this study were also found to have high phosphorus levels in storage organs, compared to a wide array of wild potato species (Table 1).

While this paper has focused on epiphytic relatives of potato, the tuber mineral survey revealed non-epiphytic species that may also be useful in mineral nutrition studies. Solanum albornozii and S. flahaultii, for example, were among the highest ranked species for several minerals. A large amount of phenotypic variation, and presumably genotypic variation, is common within accessions in wild potato (Bamberg et al., 1996; Douches et al., 2001; Jansky et al., 2006, 2008, 2009; Spooner et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2010; Cai et al., 2011). This is expected, considering the wide range of habitats in which wild Solanum species grow.

Anatomical features for mineral uptake, such as tanks in bromeliads and aerial roots in orchids are not found in S. morelliforme and S. clarum. In non-epiphytic potato, calcium uptake has been studied intensively, revealing two types of enhanced mineral uptake mechanisms based on physiological rather than anatomical adaptations (Bamberg et al., 1993, 1998). In one system, plants are able to take up adequate nutrients from a low nutrient environment. In the second system, plants accumulate high levels of calcium from an environment with moderate levels of the mineral. Nutrient efficient plants may possess one or both of these mechanisms (Bamberg et al., 1993, 1998). Mineral uptake mechanisms have not yet been characterized in epiphytic potato. However, it appears that they must rely on physiological rather than anatomical mineral uptake mechanisms to survive in nutrient-poor crown humus.

An ideal model epiphytic plant species would have a short life cycle and be capable of rapid and reliable asexual reproduction. Many epiphytic species require 10–20 years to reach sexual maturity (Mondragon et al., 2015). Solanum clarum and S. morelliforme, however, reach maturity in a matter of months. They are easily propagated asexually via stem-leaf cuttings or as tissue culture plantlets, have small space requirements (they grow readily in peat-based potting mix in small pots), and do not require high intensity light for growth. All these features make them useful model organisms for studying the biology of epiphytes.

The potato genome has been sequenced (The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2011) providing the opportunity to carry out gene discovery studies related to nutrient acquisition and storage in epiphytic relatives. The identification of the genes responsible for efficient nutrient uptake can be used to find orthologous sequences in other species. In addition, these genes may be transferred into cultivated potato. Solanum morelliforme and S. clarum are likely sexually incompatible with cultivated potato. However, genetic transformation in potato is straightforward and transgenic technology is well-established (Millam, 2009). Alternatively, somatic fusion protocols are in place and have been used to introgress the genomes of tertiary gene pool species into cultivated potato (Austin et al., 1985, 1988).

The U.S. Potato Genebank (NRSP-6) maintains 23 accessions of S. morelliforme and 14 accessions of S. clarum. This germplasm is freely available upon request to NRSP-6. Information about these accessions can be found on the USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network (www.ars-grin.gov).

Author Contributions

SJ generated the research material, carried out the mineral analyses, and supervised the writing of the manuscript. DS initiated the research project, determined the species and accessions to be analyzed and edited the manuscript. JR carried out the literature review and wrote the majority of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00231

Supplementary Table 1. Maximum tuber mineral levels in 42 wild Solanum species. No. refers to the number of accessions sampled. Epiphytic species are highlighted in blue.

Supplementary Table 2. Minimum tuber mineral levels in 42 wild Solanum species. No. refers to the number of accessions sampled. Epiphytic species are highlighted in blue.

References

Austin, S., Baer, M. A., and Helgeson, J. P. (1985). Transfer of resistance to potato leaf roll virus from Solanum brevidens into Solanum tuberosum by somatic fusion. Plant Sci. 39, 75–81. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(85)90195-5

Austin, S., Lojkowska, E., Ehlenfeldt, M. K., Kelman, A., and Helgeson, J. P. (1988). Fertile interspecific somatic hybrids of Solanum: a novel source of resistance to Erwinia soft rot. Phytopathology 78, 1216–1220. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-78-1216

Bamberg, J. B., Longtine, C., and Radcliffe, E. B. (1996). Fine screening Solanum (potato) germplasm accessions for resistance to Colorado potato beetle. Am. J. Potato Res. 73, 211–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02854875

Bamberg, J. B., Palta, J. P., Peterson, L. A., Martin, M., and Krueger, A. R. (1993). Screening tuber-bearing Solanum (potato) germplasm for efficient accumulation of tuber calcium. Am. Potato J. 70, 219–226. doi: 10.1007/BF02849310

Bamberg, J. B., Palta, J. P., Peterson, L. A., Martin, M., and Krueger, A. R. (1998). Fine screening potato (Solanum) species germplasm for tuber calcium. Am. J. Potato Res. 75, 181–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02853571

Benzing, D. H. (1990). Vascular Epiphytes: General Biology and Related Biota. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511525438

Benzing, D. H. (2000). Bromeliaceae. Profile of an Adaptive Radiation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511565175

Benzing, D. H., and Renfrow, A. (1974). The mineral nutrition of Bromeliaceae. Bot. Gaz. 135, 281–288. doi: 10.1086/336762

Benzing, D. H., and Renfrow, A. (1980). The nutritional dynamics of Tillandsia circinnata in southern Florida and the origin of air plant strategy. Bot. Gaz. 141, 165–172. doi: 10.1086/337139

Cai, X., Spooner, D., and Jansky, S. (2011). A test of taxonomic and biogeographic predictivity: resistance to potato virus Y in wild relatives of the cultivated potato. Phytopathology 101, 1074–1080. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-11-0060

Cardelús, C. L. (2009). Litter decomposition within the canopy and forest floor of three tree species in a tropical lowland rainforest, Costa Rica. Biotropica 42, 300–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00590.x

Cardelús, C. L., and Mack, M. C. (2010). The nutrient status of epiphytes and their host trees along an elevational gradient in Costa Rica. Plant Ecol. 207, 25–37. doi: 10.1007/s11258-009-9651-y

Cardelús, C. L., Mack, M. C., Woods, C., DeMarco, J., and Treseder, K. K. (2009). The influence of tree species on canopy soil nutrient status in a tropical lowland wet forest in Costa Rica. Plant Soil 318, 47–61. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9816-9

Chapin, F. S. (1980). The mineral nutrition of wild plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 233–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.001313

Chung, Y. S., Holmquist, K., Spooner, D. M., and Jansky, S. H. (2010). A test of taxonomic and biogeographic predictivity: resistance to soft rot in wild relatives of cultivated potato. Phytopathology 101, 205–212. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-10-0139

Douches, D. S., Bamberg, J. B., Kirk, W., Jastrzebski, K., Niemira, B. A., Coombs, J., et al. (2001). Evaluation of wild Solanum species for resistance to the US-8 genotype of Phytophthora infestans utilizing a fine-screening technique. Am. J. Potato Res. 78, 159–165. doi: 10.1007/BF02874771

Jansky, S. H., Simon, R., and Spooner, D. M. (2006). A test of taxonomic predictivity: resistance to white mold in wild relatives of cultivated potato. Crop Sci. 46, 2561–2570. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.12.0461

Jansky, S. H., Simon, R., and Spooner, D. M. (2008). A test of taxonomic predictivity: resistance to early blight in wild relatives of cultivated potato. Phytopathology 98, 680–687. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-6-0680

Jansky, S. H., Simon, R., and Spooner, D. M. (2009). A test of taxonomic predictivity: resistance to the Colorado potato beetle in wild relatives of cultivated potato. J. Econ. Entomol. 102, 422–431. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0155

Jenik, J. (1973). Root systems of tropical trees. 8. Stilt roots and allied adaptations. Preslia (Prague) 45, 250–264.

Laube, S., and Zotz, G. (2003). Which abiotic factors limit vegetative growth in a vascular epiphyte? Funct. Ecol. 17, 598–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00760.x

Luttge, U. (1989). Vascular Plants as Epiphytes: Evolution and Ecophysiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74465-5

Millam, S. (2009). “Developments in transgenic biology and the genetic engineering of useful traits,” in Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology. ed L. S. Kaur (New York, NY: Academic Press), 669–686.

Mondragon, D., Valverde, T., and Hernandez-Apolinar, M. (2015). Population ecology of epiphytic angiosperms: a review. Trop. Ecol. 56, 1–39.

Rains, K. C., Nadkarni, N. M., and Bledsoe, C. S. (2003). Epiphytic and terrestrial mycorrhizas in a lower montane Costa Rican cloud forest. Mycorrhiza 13, 257–264. doi: 10.1007/s00572-003-0224-y

Schmidt, G., and Zotz, G. (2002). Inherently slow growth in two Caribbean epiphytic species: a demographic approach. J. Veg. Sci. 13, 527–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2002.tb02079.x

Simon, R., Fuentes, A. F., and Spooner, D. M. (2011). Biogeographic implications of the striking discovery of a 4,000 kilometer disjunct population of the wild potato Solanum morelliforme in South America. Syst. Bot. 36, 1062–1067. doi: 10.1600/036364411X605065

Spooner, D. M., Hoekstra, R., van den Berg, R. G., and Martínez, V. (1998). Solanum sect. Petota in Guatemala: taxonomy and genetic resources. Am. J. Potato Res. 75, 3–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02883512

Spooner, D. M., Jansky, S. H., and Simon, R. (2009). Tests of taxonomic and biogeographic predictivity: resistance to disease and insect pests in wild relatives of cultivated potato. Crop Sci. 49, 1367–1376. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2008.04.0211

Spooner, D. M., Rivera-Peña, A., van den Berg, R. G., and Schüler, K. (2000). Potato germplasm collecting expedition to Mexico in 1997: taxonomy and new germplasm resources. Am. J. Potato Res. 77, 261–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02855794

Spooner, D. M., Van Den Berg, R. G., Rodriguez, A., Bamberg, J., Hijmans, R. J., and Lara Cabrera, S. I. (2004). Wild potatoes (Solanum Section Petota; Solanaceae) of North and Central America. Syst. Bot. Monogr. 68, 1-209. doi: 10.2307/25027915

The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium (2011). Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature10158

Winkler, U., and Zotz, G. (2008). Highly efficient uptake of phosphorus in epiphytic bromeliads. Ann. Bot. 103, 477–484. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn231

Zotz, G. (2004). The resorption of phosphorus is greater than that of nitrogen in senescing leaves of vascular epiphytes from lowland Panama. J. Trop. Ecol. 20, 693–696. doi: 10.1017/S0266467404001889

Zotz, G. (2013). The systematic distribution of epiphytes: a critical update. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171, 453–481. doi: 10.1111/boj.12010

Zotz, G., and Asshoff, R. (2010). Growth in epiphytic bromeliads: response to the relative supply of phosphorus and nitrogen. Plant Biol. 12, 108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00216.x

Zotz, G., and Hietz, P. (2001). The physiological ecology of vascular epiphytes: current knowledge, open questions. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 2067–2078. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2067

Keywords: epiphyte, mineral uptake, Solanum clarum, Solanum morelliforme

Citation: Jansky SH, Roble J and Spooner DM (2016) Solanum clarum and S. morelliforme as Novel Model Species for Studies of Epiphytism. Front. Plant Sci. 7:231. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00231

Received: 28 September 2015; Accepted: 11 February 2016;

Published: 29 February 2016.

Edited by:

Marta Wilton Vasconcelos, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, PortugalReviewed by:

Hannetz Roschzttardtz, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, ChileGuodong Liu, University of Florida, USA

Copyright © 2016 Jansky, Roble and Spooner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shelley H. Jansky, c2hlbGxleS5qYW5za3lAYXJzLnVzZGEuZ292; c2hqYW5za3lAd2lzYy5lZHU=

Shelley H. Jansky

Shelley H. Jansky Jacob Roble

Jacob Roble David M. Spooner

David M. Spooner