95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 28 July 2015

Sec. Plant Systems and Synthetic Biology

Volume 6 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00575

This article is part of the Research Topic Plant Single Cell Type Systems Biology View all 13 articles

Genome-wide expression studies on nodulation have varied in their scale from entire root systems to dissected nodules or root sections containing nodule primordia (NP). More recently efforts have focused on developing methods for isolation of root hairs from infected plants and the application of laser-capture microdissection technology to nodules. Here we analyze two published data sets to identify a core set of infection genes that are expressed in the nodule and in root hairs during infection. Among the genes identified were those encoding phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enzymes including Chalcone-O-Methyltransferase which is required for the production of the potent Nod gene inducer 4′,4-dihydroxy-2-methoxychalcone. A promoter-GUS analysis in transgenic hairy roots for two genes encoding Chalcone-O-Methyltransferase isoforms revealed their expression in rhizobially infected root hairs and the nodule infection zone but not in the nitrogen fixation zone. We also describe a group of Rhizobially Induced Peroxidases whose expression overlaps with the production of superoxide in rhizobially infected root hairs and in nodules and roots. Finally, we identify a cohort of co-regulated transcription factors as candidate regulators of these processes.

Most legumes are able to interact with soil bacteria called rhizobia to form special root structures called nodules within which the bacteria are able to fix atmospheric nitrogen, a process which is fueled by host photosynthate. In Medicago truncatula, as with many legumes, the rhizobia infects the host root by colonizing special intracellular tubular invaginations called infection threads that form first in root hairs and then later in mature nodules. This process begins with rhizobial attachment near the tip of growing root hairs which then curl and entrap a rhizobial microcolony in an infection pocket, also called an infection focus. The infection thread then extends as a tubular structure from this pocket through the length of the root hair, becoming colonized by rhizobia as it grows (Fournier et al., 2008). The process of infection thread formation is then repeated in the underlying cell layers allowing the rhizobia access to the inner root layers which have divided to form the NP. Root hair infection involves the upregulation of 100s of genes that regulate several different processes including host-symbiont signaling and diverse developmental processes including cell growth and engagement of the cell cycle (Libault et al., 2010; Breakspear et al., 2014). While maturing the nodule forms several developmental zones: an apical meristem (Zone I), an infection zone containing cells that form infection threads (ZII), a nitrogen fixing zone comprised of giant cells filled with endocytosed nitrogen-fixing rhizobia (ZIII), an interzone (IZ), and a senescent zone, where no nitrogen fixation takes place (ZIV). The process of infection, from the initial entry of the rhizobia into the infection threads up until their release into symbiosomes, requires constant communication between the host and symbiont. At the heart of the dialog is the production of bacterial signaling compounds called Nod factors. Nod factors are produced in response to plant flavonoids, phenylpropanoid compounds which are secreted by the roots into the rhizosphere (Peters et al., 1986; Redmond et al., 1986; Maxwell et al., 1989; Kape et al., 1992; Phillips et al., 1994; Zuanazzi et al., 1998; Subramanian et al., 2007). The secreted flavonoids induce the expression of rhizobial nod genes required for the production of Nod factors through activation of the transcription factor NodD (Mulligan and Long, 1985; Rossen et al., 1985). The flavonoids produced by a given host are often specific to certain symbionts, only activating Nod genes in nodulation-competent rhizobia (Györgypal et al., 1988). In M. truncatula, several flavonoids capable of inducing Nod gene in its symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti have been identified and one of the most potent is 4,4′-dihydroxy 2′-methoxychalcone (Kapulnik et al., 1987; Maxwell et al., 1989; Orgambide et al., 1994). The enzyme Chalcone O-Methyltransferase (ChOMT) in the closely related M. sativa is required for production of this compound from isoliquiritigenin (4,2′,4′-trihydroxychalcone; Maxwell et al., 1992). Our recent study has shown that the M. truncatula ortholog, ChOMT1, and three other close homologs (ChOMT2, ChOMT3, and ChOMT4) were induced during infection of root hairs (Breakspear et al., 2014). Transcripts for two of these isoforms were also detected in the infection zone (Zone II) of mature nodules (Roux et al., 2014), but a spatio-temporal analysis of the expression of these genes during early infection is lacking.

One of the first physiological events occurring during nodulation is the generation of ROS (Cook et al., 1995; Ramu et al., 2002), which is coincident with enhanced flavonoid biosynthesis (van Brussel et al., 1990; Mathesius et al., 1998; Hassan and Mathesius, 2012). Earlier studies on the production and breakdown of ROS by rhizobia suggest that ROS levels must be maintained between certain limits for the symbiosis to be successful (Santos et al., 2000; Jamet et al., 2003, 2007). The expression of Rhizobial Induced Peroxidase 1 (RIP1) was shown to increase in response to rhizobial infection or Nod factors and was found to be correlated with the production of ROS during rhizobial infection (Cook et al., 1995; Ramu et al., 2002). Recently, transcriptomic analysis of root hairs revealed that RIP1 belongs to a family of 10 RIPs that are similarly strongly induced upon inoculation with rhizobia or Nod factors, further suggesting an important role for the modulation of ROS during nodulation (Breakspear et al., 2014).

In this study we compared published data from studies using single-cell types, i.e., microarray data for root hairs collected from seedlings inoculated with rhizobia (Breakspear et al., 2014) and RNAseq data for laser-capture microdissected nodules (Roux et al., 2014) to identify a core set of genes associated with infection. We then investigated the expression of two ChOMT genes and the generation of superoxides during the different stages of nodulation in infected root hair and nodule cells. Finally, we identified transcription factors induced during rhizobial infection of root hairs and preferentially expressed in the nodule infection zone as potential regulators of ROS and phenylpropanoid production.

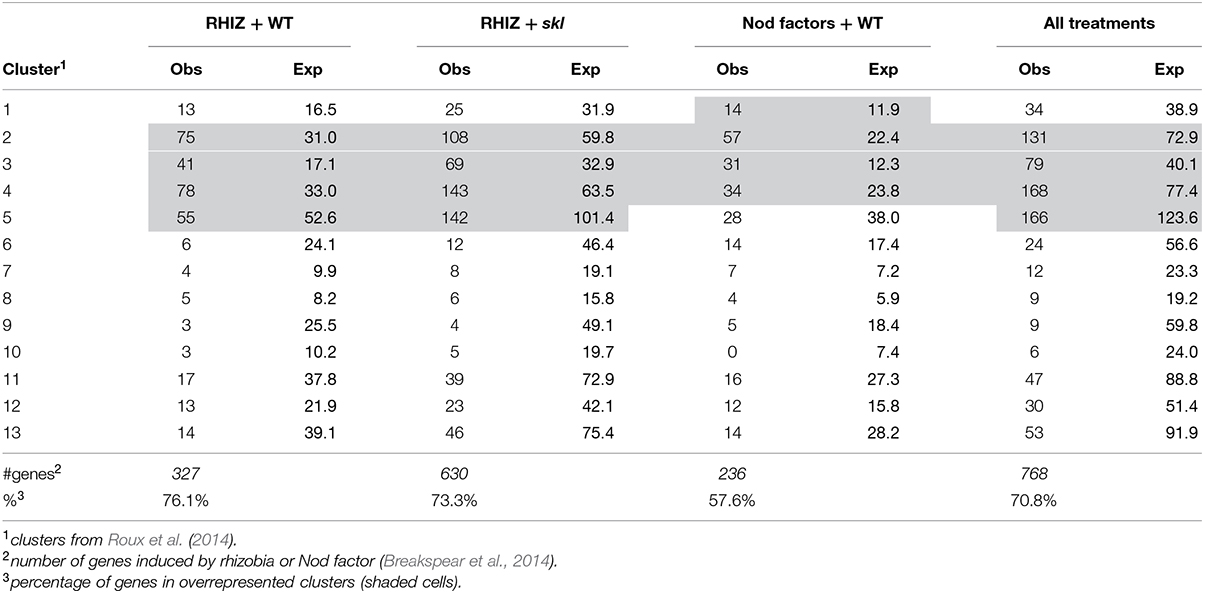

The first data set used for our analysis was from Roux et al. (2014). This study generated RNAseq data by laser-capture microdissection of M. truncatula cv. Jemalong A17 nodules harvested 15 days post inoculation with S. meliloti 2011. This was designated as data set A. A second data set was from a microarray analysis of root hairs of harvested from M. truncatula cv. Jemalong A17 seedlings 1, 3, and 5 days post inoculation with S. meliloti 1021 or treated with Nod factor (24 h post treatment; Breakspear et al., 2014), designated data set B. Roux et al. (2014) assigned all plant and bacterial genes that were differentially expressed between zones into 13 hierarchical clusters based on their expression across the sampled nodule zones. To compare the two data sets we identified all genes in dataset B that could be assigned to the above-mentioned clusters and compared their frequencies to that of all genes assigned to clusters in dataset A using a chi-squared test with the online GraphPad QuickCalc software http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/chisquared1.cfm.

Composite plants and seedlings were grown in controlled environment chambers with 16 h day length with a light intensity of 90–130 μmol m-2 s-1 and constant temperature of 20°C. For rhizobial inoculation a 24-h culture of S. meliloti 1021 rhizobia was spun down and resuspended in buffered nodulation medium to an optical density of 0.02 at 600 nm, and 3 mL of the culture was used to inoculate each of the growing M. truncatula plants.

For the promoter-GUS analyses, the promoter regions of ChOMT2 (Medtr3g021440; from -23 to -1803 bp) and ChOMT3 (Medtr7g011900; from -23 to -1885 bp) were amplified by PCR using Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB). The fragments were then cloned into pDONR207 and after sequence confirmation were transferred to the destination vector pKGWFS7 upstream of the GUS open reading frame using the GATEWAY cloning system (Life Technologies) as per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The vector was then transformed into M. truncatula (A17) using Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation as described previously (Breakspear et al., 2014). The composite plants with transgenic roots were then transferred to a soil mixture of Terragreen (Oil-Dri UK) and silver sand 1:1 mixture, inoculated with S. meliloti 1021, and watered as needed with distilled water. Nodulated roots were then stained for GUS activity at 1, 2, and 3 weeks post inoculation, as previously described (Breakspear et al., 2014).

For nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining, M. truncatula seedlings were grown in Terragreen (Oil-Dri UK) and silver sand mixture (1:1) for 7 days and then inoculated with S. meliloti 1021. At 14 days post inoculation the nodulated roots were cut off and stained in 0.1% NBT water solution (Promega UK) for 40 min in the dark at room temperature. Imbedding and sectioning of plant tissues was carried out as previously described (Guan et al., 2013).

Infection threads form in both root hairs and in cells of nodule ZII. To identify genes common to infection thread formation in these two cell types we compared genes that were induced either by rhizobia or by purified Nod factors in root hairs with the genes expressed in different nodule zones (Roux et al., 2014). To do this we used the RNAseq analysis described by Roux et al. (2014) which assigned genes to 13 clusters based on their expression across tissues sampled from each nodule zone using laser-capture microdissection. The advantage of this approach is that genes that are only expressed in the nodule but not in the root hair or vice versa are not considered. For example, the large family genes encoding for nodule-specific cysteine-rich (NCR) peptides, which are highly expressed in the nodule but are not expressed in root hairs, are thereby excluded. A total of 768 genes were identified that met the clustering criteria and were induced by at least one treatment in root hairs. When these genes were assigned to their clusters a disproportionate number of the rhizobially induced genes in the WT and sickle (skl) mutant belonged to clusters 2–5, which are genes that are primarily expressed in the nodule meristem (ZI) and distal ZII with some expression in proximal ZII (Table 1). Nod factor-induced genes displayed an overlapping pattern, with clusters 1–4 being over-represented, cluster one containing genes with the majority of their expression in the meristem (ZI) with some expression in distal ZII (Table 1). For each treatment and the combined treatments the observed frequencies in the different clusters were significantly different than the expected frequencies (Chi-squared tests, all p-values <0.0001). This analysis suggests that a core set of genes underlies infection processes in both tissue types.

TABLE 1. Comparison of the observed number of genes induced by rhizobial inoculation in root hairs belonging to different clusters of nodule expression (Roux et al., 2014).

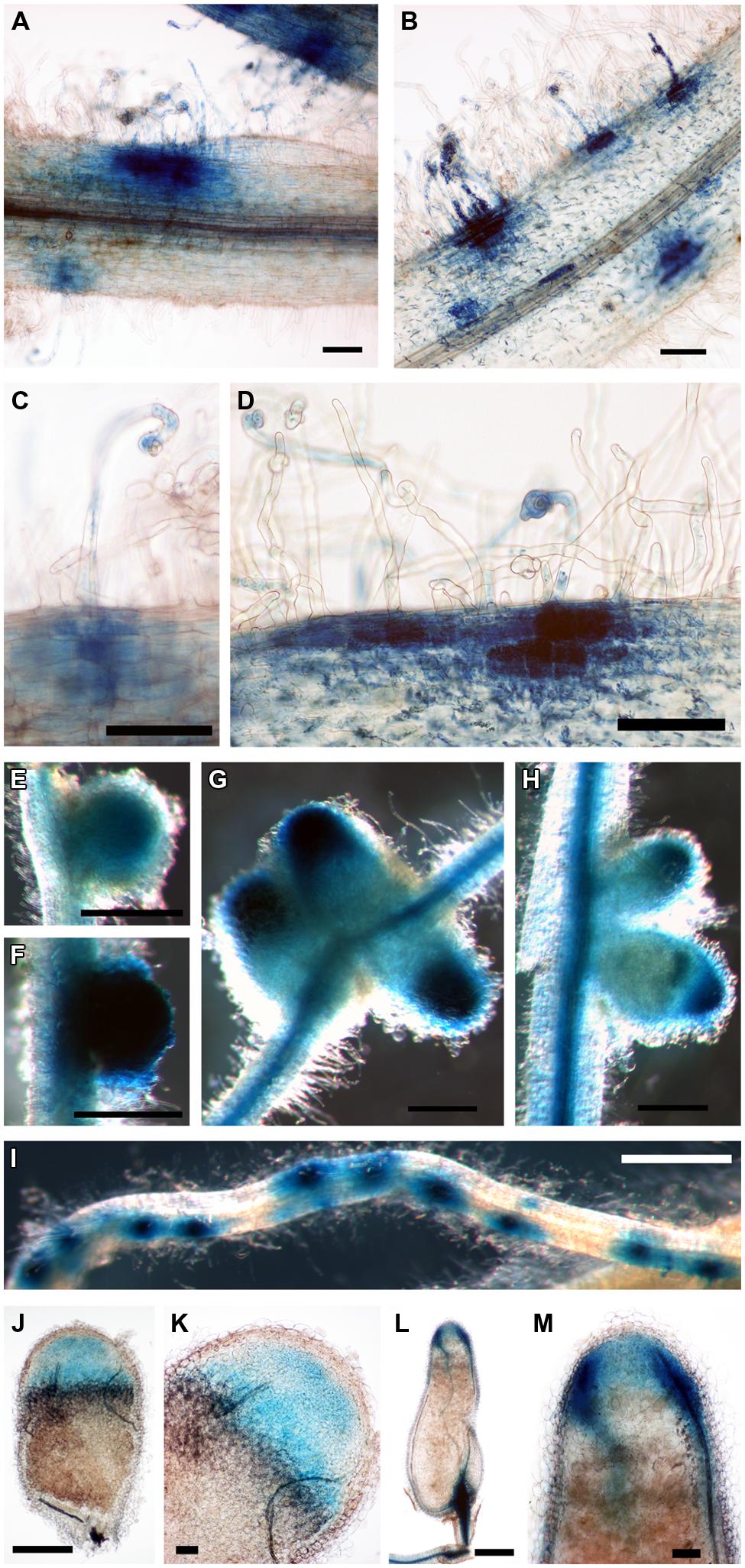

We then considered the genes that were induced by rhizobial infection and were found in the over-represented clusters 2–5 (Supplementary Table S1). Amongst these genes were several members of the isoflavonoid biosynthesis pathway analyzed in Breakspear et al. (2014) including Chalcone Reductase (CHR) which is required for the production of isoliquiritigenin and ChOMT which converts isoliquiritigenin to the even more potent nod gene inducer methoxychalcone. Four ChOMT genes are induced in root hairs after rhizobial infection (Breakspear et al., 2014), but their expression patterns during nodulation have not been investigated in detail. We investigated the expression of two of these genes, ChOMT2 and ChOMT3, during the early stages of infection and nodule formation using promoter-GUS analysis in A. rhizogenes transformed roots. We found that both genes were expressed in root hairs undergoing infection (Figures 1A–D) and throughout the NP (Figures 1E,F). As the nodule matured the expression of both genes was restricted to the apex (Figures 1G,H), and in root tips (data not shown). The expression of both genes was typically observed at numerous infection sites along the root (Figures 1A,B,D,I). Hand sectioning of the nodules revealed expression of ChOMT2 in the nodule meristem, the infection zone, with some expression in the IZ, closely matching the published LCM data (Figures 1J,K; Roux et al., 2014). ChOMT3 expression was also found in the nodule meristem and but was absent from the IZ and proximal infection zone (Figures 1L,M), again closely reflecting the data of Roux et al. (2014). Expression of both genes was absent in the nitrogen fixation zone. ChOMT3 expression was also strong in the apical part of the nodule vasculature, including the nodule vascular meristems (Figures 1L,M).

FIGURE 1. Expression of Chalcone O-Methyltransferase (ChOMT2) and ChOMT3 during nodulation of Medicago truncatula. (A,C,E,G,J,K) pCHOMT2:GUS transgenic roots 7–21 days post inoculation with Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. (B,D,F,H,I,L,M) pCHOMT3:GUS transgenic roots 7–21 days post inoculation with S. meliloti 1021. Bars are 100 μm (A,B,C,D,K,M), 500 μm (E,F,G,H,J,L), and 1000 μm (I). (J,K,L,M) are free-hand sections.

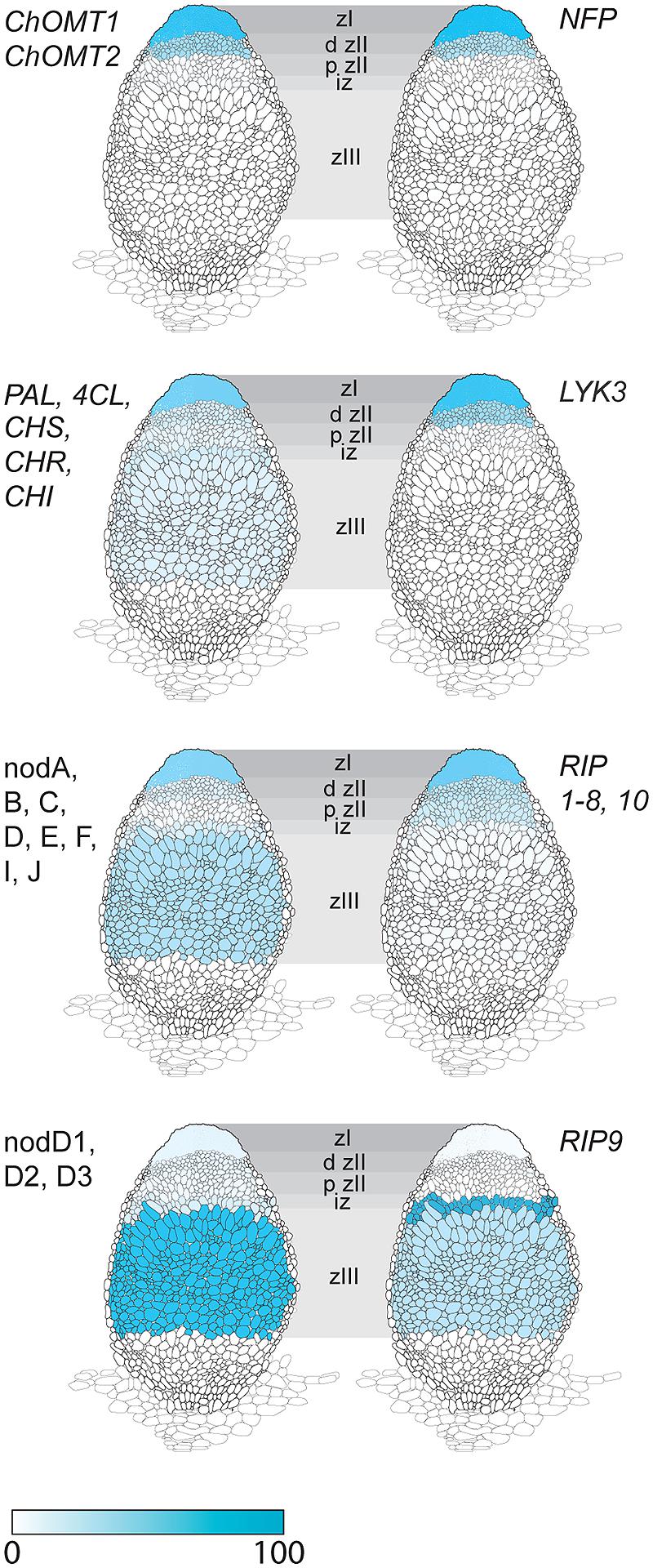

The expression of ChOMT2 and ChOMT3 corresponded well with the other genes encoding enzymes for isoliquiritigenin production which had an average of 65% of their total expression in ZI and ZII (Figure 2, Supplementary Table S1). However, some transcripts of these genes (∼10% of the total) were also detected in each of the remaining zones (IZ, ZIII). The expression of the rhizobial nod genes required for the biosynthesis and secretion of Nod factors which are known to be induced by flavonoids also had strong expression in ZI and proximal ZII (on average 55% of the total reads), however, as noted by Roux et al. (2014), they also showed expression (∼25% of total reads) in the nitrogen fixation zone (ZIII; Figure 2). Based on our results it seems unlikely that methoxychalcone is responsible for the induction of nod gene expression in ZIII. Instead this expression could be induced by isoliquiritigenin for which the required genes are expressed in ZIII (Figure 2). In contrast to the Nod factor biosynthesis and transport genes, the three nodD genes were mostly expressed in ZIII, with only one (nodD3) having some expression in the nodule apex (ZI; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Expression in different nodule zones of a family of Rhizobial Induced Peroxidases (RIPs) and genes involved in the induction of Nod factor biosynthesis by flavonoids. Genes for isoliquiritigenin biosynthesis: ChOMT1, ChOMT2; genes Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase (PAL), 4-Coumarate:coA Ligase (4CL), Chalcone Synthase (CHS), Chalcone Reductase (CHR), Chalcone Isomerase (CHI); Rhizobial nod genes for Nod factor biosynthesis and transport: nodA, B, C, D, E, F, I, J; S. meliloti nod (nodD1, D2, D3) genes for flavonoid-dependent activation of Nod factor biosynthesis; Nod factor receptor genes Nod Factor Perception (NFP) and LysM receptor-like kinase (LYK3); RIPs 1–10. Data, adapted from Roux et al. (2014), is represented as percent of total normalized transcripts for each gene or group of genes, see Supplementary Table S2 for details.

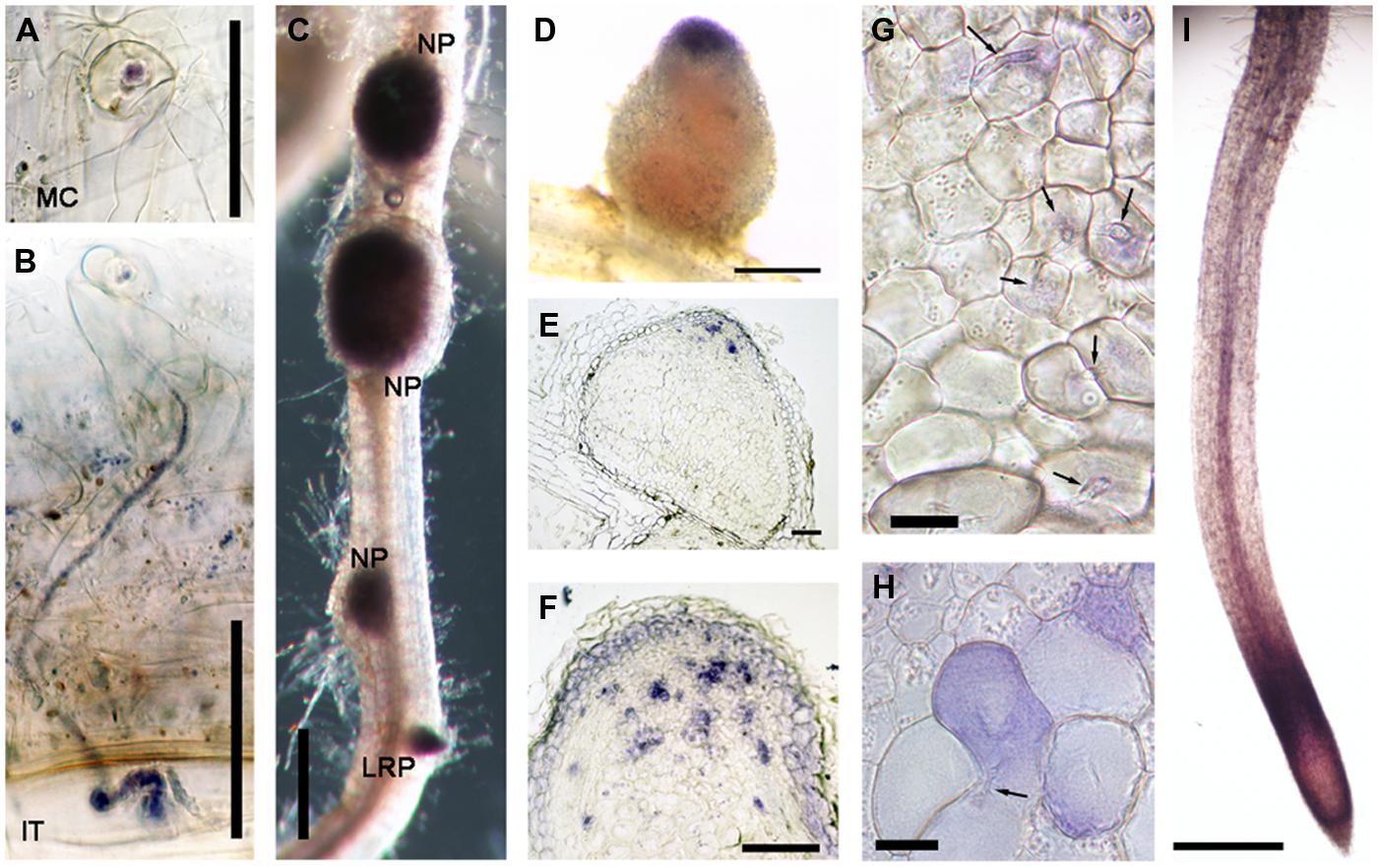

Another gene class identified in the overlap between the inoculated root hair and nodule data sets was type III peroxidases, which are apoplastic/cell wall localized enzymes have a role in cell wall remodeling (Francoz et al., 2015). The genes encoding this family of enzymes have been shown to be inducible by rhizobia and Nod factors in root hairs and designated as RIP1-10 (Breakspear et al., 2014). Most of the previously identified RIPs are also present in ZI and ZII (Figure 2, data from Roux et al., 2014). Unexpectedly one of them, RIP9, was more highly expressed than all the others combined (Supplementary Table S3) and had a dramatically different expression domain, being >90% expressed in the IZ and ZIII (Figure 2). Since secreted peroxidases are capable of generating reactive oxygen species, we monitored superoxide production at the different stages of nodulation using NBT staining (Doke, 1983). The stain was seen in microcolonies and in infection threads at the early stages of nodulation (Figures 3A,B). The nascent NP were also strongly stained (Figure 3C) and as nodules matured, the staining was mainly found in the nodule apex (Figure 3D). Nodule sectioning revealed staining in a patchwork of individual cells located mostly in ZII and sometimes in ZIII (Figures 3E,F). Closer inspection revealed that the staining was present in cells containing infection threads in ZII (Figure 3G) and also in ZIII (Figure 3H). There was also staining in a thin layer of non-infected cells near the nodule apex (Figure 3F). In addition, staining was also strong in root tips of both mature primary roots and emerging lateral roots (Figure 3G).

FIGURE 3. Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining of M. truncatula roots nodulated by S. meliloti 1021. (A) A microcolony within an infection focus. (B) An infection thread in a root hair. (C) Nodule primordia (NP) and a lateral root primordium (LRP). (D) An intact nodule (E,F,G,H) nodule sections, 10 μm thick (I) the primary root tip. In (G) and (H) arrows indicate infection threads. Plants harvested 14 dpi with S. meliloti 1021. Bars = 50 μm (A,B), 100 μm (E,F), and 500 μm (C,D,I), 20 μm (G,H).

The transcription factors controlling the expression of genes for flavonoid biosynthesis and ROS production in the nodule are currently not known. A large number of transcription factors (Table 2) were shared between the genes in nodule clusters 2–5 and genes induced in root hairs of infected plants (Table 3). These included the well-studied ERN1, ERN2, and NSP2 which are required for early infection events and nodule development (Oldroyd and Long, 2003; Kaló et al., 2005; Heckmann et al., 2006; Middleton et al., 2007; Cerri et al., 2012). In addition, four genes encoding CCAAT-box transcription factor subunits (NF-YA1, NF-YA2, NF-YC2, NF-YB7) were in this group. NF-YA1 and NF-YC2 are important for both rhizobial infection and nodule development (Combier et al., 2006, 2008; Zanetti et al., 2010; Soyano et al., 2013; Laporte et al., 2014), while NF-YA2 is a close homolog of NF-YA1. This co-regulation across root hair and nodule-zones suggests that the encoded subunits may act as part of heterocomplex along with NF-YB7 to regulate infection. Notably the nf-ya1 mutant forms nodules with either reduced or absent meristems that fail to release the bacteria from the infection thread into symbiosomes (Xiao et al., 2014). A summary of all data (Breakspear et al., 2014; Roux et al., 2014) for the entire family of M. truncatula CCAAT-box transcription factors is included in Supplementary Table S4.

The roles of the remaining transcription factors in nodulation have not been defined. Of note in this group are the nodule-specific GRF-Zinc finger gene N20, and the M. truncatula ortholog of Arabidopsis thaliana Zinc Finger Protein 6 (ZFP6). ZFP6 has been assigned a role in integration of gibberellic acid and cytokinin signaling (Zhou et al., 2013).

Current molecular genetic studies of nodulation rely heavily on gene expression data to provide insight into symbiotic processes. Candidate genes identified in this manner can then be followed up using reverse genetic studies such as the Tnt1 or LORE1 transposon mutant collections available in M. truncatula or Lotus japonicus, respectively (Tadege et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2011; Fukai et al., 2012; Urbański et al., 2012). Recently laser-capture has been used to target the specific regions of indeterminate nodules (Roux et al., 2014), including the infection zone which contain the cells becoming infected by rhizobia. A subsequent study, which transcriptionally profiled root hairs from seedlings undergoing infection (Breakspear et al., 2014), provides a unique opportunity to compare gene expression responses during infection of these two cell types. A disproportionate number of genes induced in root hairs of infected plants were expressed in the nodule apex. The majority of genes induced in root hairs in response to purified Nod factors were also expressed in the nodule apex (71% belonging to clusters 2–5), mirroring the analysis by Roux et al. (2014) who reported that 63.4% of genes induced by Nod factors in intact root samples in an earlier study (Czaja et al., 2012) belonged to clusters 1–4. This overlap suggests that a core set of genes required to support rhizobial infection in both epidermal and cortical (nodule) tissues are directly induced by Nod factor signaling.

Expression of the ChOMT genes required for the production of the nod-gene inducing flavonoid methoxychalcone was high in infected root hairs and within the nodule was restricted to the infection zone, matching the pattern of expression of rhizobial Nod factor synthesis/export genes and the Nod factor receptors Nod Factor Perception (NFP) and LysM receptor-like kinase (LYK3), (Figure 2; Roux et al., 2014). This is consistent with the detection of flavonoids in root hairs undergoing infection (Hassan and Mathesius, 2012) and is consistent with evidence showing that Nod factor production by the rhizobia is required at all stages of infection thread development (Marie et al., 1992; Den Herder et al., 2007). While ChOMT expression was restricted to ZII, transcripts for genes required to make the methoxychalcone precursor isoliquiritigenin as well as rhizobial nod genes were also detected in the N-fixation zone (ZIII; Figure 2; Roux et al., 2014). The authors further showed using promoter-GUS analysis that the expression of the nod genes coincided with the relatively infrequent infection threads observed in ZIII. The significance of these sporadic infections which can also be observed in mature determinate nodules of L. japonicus (unpublished results) remains to be determined. Our analysis suggests that the nod gene inducer in the N-fixing zone of the nodule is unlikely to be methoxychalcone since ChOMT expression is tightly confined to the nodule apex. On the other hand isoliquiritigenin seems to fit the role as several genes required for its synthesis, including CHR and Chalcone Isomerase, have moderate levels of expression in ZIII. Another function recently highlighted for flavonoids is their role as antioxidants, having roles in stomatal closure and drought response (Nakabayashi et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2014). It seems possible that these compounds could serve to help buffer against damage from ROS generated in cells undergoing infection. Two Vestitone Reductase genes needed for the production of medicarpin, one of which is expressed at infection sites in the epidermis (Breakspear et al., 2014), were also found to be expressed in ZI and the IZ (Supplementary Table S2). A potential role for medicarpin is selection against incompatible rhizobia and other opportunistic bacteria as previously discussed (Breakspear et al., 2014).

The expression of the nodD genes did not correspond with the Nod factor signaling domain that was clearly delineated by the expression of the Nod factor receptors, rhizobial nod factor biosynthesis genes, and the ChOMTs, with only one gene, nodD3, having about 30% of its expression in this domain and nodD1 and nodD2 being mainly expressed in ZIII. The lack of correspondence between nodD expression and the Nod factor signaling domain may reflect the fact that the nodD gene, at least in Rhizobium leguminosarum, is constitutively expressed and is not induced by flavonoids (Rossen et al., 1985). Furthermore, the NodD protein is present at relatively low levels in the rhizobia, suggesting that low constitutive expression is sufficient for its activity (Schlaman et al., 1991). While nodD expression is not induced by flavonoids, activation of nod genes by some NodD proteins is flavonoid-dependent; methoxychalcone strongly induces nod gene expression in rhizobia containing extra copies of nodD1 or nodD2 in S. meliloti (Hartwig et al., 1990). In contrast, NodD3 induction of nod gene expression is flavonoid-independent and requires the transcriptional regulator syrM (Mulligan and Long, 1989). Accordingly, in nodules syrM expression closely matches that of nodD3 Roux et al. (2014; Supplementary Table S2). A study which examined all three single nodD mutants showed a small reduction in nodulation in the nodD3 mutant only, but strongly reduced nodulation for all combinations of double mutants, suggesting all three isoforms are important in the interaction with M. truncatula (Smith and Long, 1998). Similar results were obtained with M. sativa (Honma and Ausubel, 1987). The available data suggest that nodD1 and nodD2 activation of nod gene expression in the infection zone occurs mainly through the action of methoxychalcone, but expression of these genes in ZIII may be mediated by another flavonoid, such as isoliquiritigenin, whilst NodD3 operates independently of flavonoids and is sufficient to sustain nodulation.

Also common to epidermal and cortical infection was the strong expression of a subset of RIPs. Type III peroxidases have been implicated in generation of apoplastic reactive oxygen species (Martinez et al., 1998; Bindschedler et al., 2006), with one important role being to promote cell wall hardening (Passardi et al., 2004). A corresponding role for these peroxidases has been proposed in the rigidification of the infection thread cell wall and matrix (Wisniewski et al., 2000). Expression of nine of the ten RIPs was strictly limited to Zones I and II of the nodule while another family member, RIP9, showed a complementary pattern, being very highly expressed (∼7 times higher than all other RIPs combined) in the IZ and ZIII. The expression of RIP9 therefore coincides with the low pO2 in the proximal zones of the nodule; Roux et al. (2014) report that the leghemoglobin genes required for microaerobic conditions are strongly and abruptly upregulated in the IZ and remain highly expressed in ZIII. Indeed, low oxygen availability in these zones might explain the need for a highly expressed, separately regulated peroxidase isoform. While the link between type III peroxidases with rhizobial infection is well established (Cook et al., 1995; Ramu et al., 2002; this study) functional analysis is confounded by the presence of multiple family members with similar expression patterns. RIP9 may therefore present an opportunity to use genetics to help study the role of these enzymes in nodulation.

Based on co-expression and co-regulation we identified candidate transcription factors involved in rhizobial infection. The group included ERN1, ERN2, NSP2, NF-YA1, and NF-YC2, all of which have been functionally implicated in rhizobial infection (Oldroyd and Long, 2003; Kaló et al., 2005; Combier et al., 2006, 2008; Heckmann et al., 2006; Middleton et al., 2007; Zanetti et al., 2010; Cerri et al., 2012; Soyano et al., 2013; Laporte et al., 2014). Two other genes encoding CCAAT-box subunits were also identified in the analysis, NF-YA1, a close homolog of NF-YA1, and NF-YB7. As these transcriptional regulators act in heterocomplexes having one of each A, B, and C subunits, it is tempting to speculate that these act together to control infection, with NF-YA1 and NF-YA2 acting interchangeably. Among the unstudied members of this group is a GRF zinc finger protein N20, which has expression that is highly nodulation-specific but with only weak aa sequence homology to other legumes. Also of interest is ZPF6 which encodes a C2H2 transcription factor that is required for trichome development, and has been proposed as an integrator of GA and cytokinin signaling in this process (Zhou et al., 2013). Also found were the transcription factors cytokinin response regulator RRA3, an ERF (Medtr3g090760) with homology to Arabidopsis Cytokinin Response Factor 4 (Table 2), and two genes encoding the GA biosynthetic enzymes, Ent-Kaurenoic Acid Oxidase 1 (KAO1) and Gibberellin 3-Oxidase 1 (GA3OX1; Supplementary Table S1), which were part of a larger set of GA and cytokinin related genes identified as upregulated after rhizobial inoculation (Breakspear et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015). This indicates that the regulation of these hormones, along with auxin, is important during infection in both root hairs and within the nodule.

This study illustrates the power of single-cell type approaches to study the key mechanisms that underlie a biological process. Through the study of gene expression associated with infection thread formation in two different tissues, tissue-specific and background effects can be eliminated and core processes exposed. Improvements can of course still be made; Roux et al. (2014) estimated a 10% rate of contamination of ZII transcripts in the ZI sample, which argues the need for sampling smaller areas of tissue. Furthermore, it can be difficult to discern different cell types, for instance between meristematic cells and cells of the distal infection zone (Limpens et al., 2013). Similarly, while root hair isolation methods used by Breakspear et al. (2014) or Libault et al. (2010) are technically less challenging than laser-capture microdissection, only a small percentage of root hairs in the sample are undergoing infection. Ultimately, a single cell-based approach offers the greatest resolution, having the potential to sub-classify cells from the same tissue. Such an approach would avoid the averaging out of highly localized phenomena such as the production of superoxide reported in this study. Another limitation of the described approach is evident from the analysis of the transcriptional regulators. It is clear that infection thread development is comprised of numerous processes occurring in parallel sometimes within the same cells which cannot easily be separated even using single-cell approaches. This can be addressed in three ways. The first is to use a developmental time series, as employed in Breakspear et al. (2014), which allowed partial resolution of events occurring before and during infection. The second is the use of relevant sensory or chemical inputs that can perturb individual components of the system. For instance a subset of the genes may be inducible by treatment with ROS, allowing them to be partitioned away from the larger set of co-regulated genes. In this respect the ever-growing gene expression atlases available for medicago and other plants present a useful resource (Benedito et al., 2008; Hruz et al., 2008). The third and most powerful approach is the use of mutants. Careful comparison of specific mutants defective in one or a few processes will provide a clearer picture of the transcriptional network underlying rhizobial infection.

Our work compares two different types of data sets and identifies a core set of infection genes common to infection in both root hairs and nodules with specific attention to transcription factors that can serve as a starting point for future studies. In addition we show for the first time the expression pattern of two genes encoding ChOMT isoforms, an enzyme that plays a key role in the symbiosis that so far has only been studied at the biochemical level. We confirmed expression of these genes in the nodule infection zone, and have extended this knowledge by showing that these genes are specifically induced in infected root hairs, and that one gene is expressed in the nodule vascular bundle. We show using NBT staining that superoxide is being produced specifically in cells undergoing infection in root hairs and the nodule further demonstrating the tight link between ROS production and the infection process.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grants BB/G023832/1 and BB/L010305/1 and the John Innes Foundation.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00575

Benedito, V. A., Torres-Jerez, I., Murray, J. D., Andriankaja, A., Allen, S., Kakar, K., et al. (2008). A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 55, 504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03519.x

Bindschedler, L. V., Dewdney, J., Blee, K. A., Stone, J. M., Asai, T., Plotnikov, J., et al. (2006). Peroxidase-dependent apoplastic oxidative burst in Arabidopsis required for pathogen resistance. Plant J. 47, 851–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02837.x

Breakspear, A., Liu, C., Roy, S., Stacey, N., Rogers, C., Trick, M., et al. (2014). The root hair ‘infectome’ of Medicago truncatula uncovers changes in cell cycle genes and reveals a requirement for auxin signalling in rhizobial infection. Plant Cell 26, 4680–4701. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133496

Cerri, M. R., Frances, L., Laloum, T., Auriac, M. C., Niebel, A., Oldroyd, G. E., et al. (2012). Medicago truncatula ERN transcription factors: regulatory interplay with NSP1/NSP2 GRAS factors and expression dynamics throughout rhizobial infection. Plant Physiol. 160, 2155–2172. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203190

Cheng, X., Wen, J., Tadege, M., Ratet, P., and Mysore, K. S. (2011). Reverse genetics in Medicago truncatula using Tnt1 insertion mutants. Methods Mol. Biol. 678, 179–190. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-682-5_13

Combier, J. P., de Billy, F., Gamas, P., Niebel, A., and Rivas, S. (2008). Trans-regulation of the expression of the transcription factor MtHAP2-1 by a uORF controls root nodule development. Genes Dev. 22, 1549–1559. doi: 10.1101/gad.461808

Combier, J. P., Frugier, F., de Billy, F., Boualem, A., El-Yahyaoui, F., Moreau, S., et al. (2006). MtHAP2-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of symbiotic nodule development regulated by microRNA169 in Medicago truncatula. Genes Dev. 20, 3084–3088. doi: 10.1101/gad.402806

Cook, D., Dreyer, D., Bonnet, D., Howell, M., Nony, E., and VandenBosch, K. (1995). Transient induction of a peroxidase gene in Medicago truncatula precedes infection by Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Cell 7, 43–55. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.1.43

Czaja, L. F., Hogekamp, C., Lamm, P., Maillet, F., Martinez, E. A., Samain, E., et al. (2012). Transcriptional responses toward diffusible signals from symbiotic microbes reveal MtNFP- and MtDMI3-dependent reprogramming of host gene expression by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal lipochitooligosaccharides. Plant Physiol. 159, 1671–1685. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195990

Den Herder, J., Vanhee, C., De Rycke, R., Corich, V., Holsters, M., and Goormachtig, S. (2007). Nod factor perception during infection thread growth fine-tunes nodulation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 129–137. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-2-0129

Doke, N. (1983). Involvement of superoxide anion generation in the hypersensitive response of potato tuber tissues to infection with an incompatible race of Phytophthora infestans and to the hyphal wall components. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 23, 345–357. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(83)90019-X

Fournier, J., Timmers, A. C., Sieberer, B. J., Jauneau, A., Chabaud, M., and Barker, D. G. (2008). Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol. 148, 1985–1995. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125674

Francoz, E., Ranocha, P., Nguyen-Kim, H., Jamet, E., Burlat, V., and Dunand, C. (2015). Roles of cell wall peroxidases in plant development. Phytochemistry 112, 15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.07.020

Fukai, E., Soyano, T., Umehara, Y., Nakayama, S., Hirakawa, H., Tabata, S., et al. (2012). Establishment of a Lotus japonicus gene tagging population using the exon-targeting endogenous retrotransposon LORE1. Plant J. 69, 720–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04826.x

Guan, D., Stacey, N., Liu, C., Wen, J., Mysore, K. S., Torres-Jerez, I., et al. (2013). Rhizobial infection is associated with the development of peripheral vasculature in nodules of Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 162, 107–115. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215111

Györgypal, Z., Iyer, N., and Kondorosi, A. (1988). Three regulatory nodD alleles of diverged flavonoid-specificity are involved in host-dependent nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. Mol. Gen. Genet. 21, 85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00322448

Hartwig, U. A., Maxwell, C. A., Joseph, C. M., and Phillips, D. A. (1990). Effects of alfalfa nod gene-inducing flavonoids on nodABC transcription in Rhizobium meliloti strains containing different nodD genes. J. Bacteriol. 172, 2769–2773.

Hassan, S., and Mathesius, U. (2012). The role of flavonoids in root–rhizosphere signalling: opportunities and challenges for improving plant–microbe interaction. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 3429–3444. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err430

Heckmann, A. B., Lombardo, F., Miwa, H., Perry, J. A., Bunnewell, S., Parniske, M., et al. (2006). Lotus japonicus nodulation requires two GRAS domain regulators, one of which is functionally conserved in a non-legume. Plant Physiol. 142, 1739–1750. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.089508

Honma, M. A., and Ausubel, F. M. (1987). Rhizobium meliloti has three functional copies of the nodD symbiotic regulatory gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 8558–8562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8558

Hruz, T., Laule, O., Szabo, G., Wessendorp, F., Bleuler, S., Oertle, L., et al. (2008). Genevestigator v3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinformatics 2008, 420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747

Jamet, A., Mandon, K., Puppo, A., and Herouart, D. (2007). H2O2 is required for optimal establishment of the Medicago sativa/Sinorhizobium meliloti and symbiosis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8741–8745. doi: 10.1128/JB.01130-07

Jamet, A., Sigaud, S., Van de Sype, G., Puppo, A., and Herouart, D. (2003). Expression of the bacterial catalase genes during Sinorhizobium meliloti–Medicago sativa symbiosis and their crucial role during the infection process. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 217–225. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.3.217

Kaló, P., Gleason, C., Edwards, A., Marsh, J., Mitra, R. M., Hirsch, S., et al. (2005). Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science 308, 1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1110951

Kape, R., Parniske, M., Brandt, S., and Werner, D. (1992). Isoliquiritigenin, a strong nod gene- and glyceollin resistance-inducing flavonoid from soybean root exudate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 1705–1710.

Kapulnik, Y., Joseph, C. M., and Phillips, D. A. (1987). Flavone limitations to root nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 84, 1193–1196. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.4.1193

Laporte, P., Lepage, A., Fournier, J., Catrice, O., Moreau, S., Jardinaud, M. F., et al. (2014). The CCAAT box-binding transcription factor NF-YA1 controls rhizobial infection. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 481–495. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert392

Libault, M., Farmer, A., Brechenmacher, L., Drnevich, J., Langley, R. J., Bilgin, D. D., et al. (2010). Complete transcriptome of the soybean root hair cell, a single-cell model, and its alteration in response to Bradyrhizobium japonicum infection. Plant Physiol. 152, 541–552. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148379

Limpens, E., Moling, S., Hooiveld, G., Pereira, P. A., Bisseling, T., Becker, J. D., et al. (2013). Cell-and tissue-specific transcriptome analyses of Medicago truncatula root nodules. PLoS ONE 8:e64377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064377

Liu, C., Breakspear, A., Roy, S., and Murray, J. D. (2015). Cytokinin responses counterpoint auxin signalling during rhizobial infection. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1019982. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1019982

Marie, C., Barny, M. A., and Downie, J. A. (1992). Rhizobium leguminosarum has two glucosamine synthases, GlmS and NodM, required for nodulation and development of nitrogen-fixing nodules. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01535.x

Martinez, C., Montillet, J. L., Bresson, E., Agnel, J. P., Daï, G. H., Daniel, J. F., et al. (1998). Apoplastic peroxidase generates superoxide anions in cells of cotton cotyledons undergoing the hypersensitive reaction to Xanthomonas campestris pv. malvacearum race 18. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11, 1038–1047. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.11.1038

Mathesius, U., Bayliss, C., Weinman, J. J., Schlaman, H. R. M., Spaink, H. P., Rolfe, B. G., et al. (1998). Flavonoids synthesized in cortical cells during nodule initiation are early developmental markers in white clover. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11, 1223–1232. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.12.1223

Maxwell, C. A., Edwards, R., and Dixon, R. A. (1992). Identification, purification, and characterization of S-adenosyl-L-methionine: isoliquiritigenin 2’-O-methyltransferase from alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 293, 158–166. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90379-B

Maxwell, C. A., Hartwig, U. A., Joseph, C. M., and Phillips, D. A. (1989). A chalcone and two related flavonoids released from alfalfa roots induce nod genes of Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 91, 842–847. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.3.842

Middleton, P. H., Jakab, J., Penmetsa, R. V., Starker, C. G., Doll, J., Kaló, P., et al. (2007). An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell 19, 1221–1234. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048264

Mulligan, J. T., and Long, S. R. (1985). Induction of Rhizobium meliloti nodC expression by plant exudate requires nodD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 6609–6613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6609

Mulligan, J. T., and Long, S. R. (1989). A family of activator genes regulates expression of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes. Genetics 122, 7–18.

Nakabayashi, R., Yonekura-Sakakibara, K., Urano, K., Suzuki, M., Yamada, Y., Nishizawa, T., et al. (2014). Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 77, 367–379. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12388

Oldroyd, G. E. D., and Long, S. R. (2003). Identification and characterization of nodulation-signaling pathway 2, a gene of Medicago truncatula involved in Nod factor signaling. Plant Physiol. 131, 1027–1032. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.010710

Orgambide, G. G., Philip-Hollingsworth, S., Hollingsworth, R. I., and Dazzo, F. B. (1994). Flavone-enhanced accumulation and symbiosis-related biological activity of a diglycosyl diacylglycerol membrane glycolipid from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4338–4347.

Passardi, F., Penel, C., and Dunand, C. (2004). Performing the paradoxical: how plant peroxidases modify the cell wall. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.09.002

Peters, N. K., Frost, J. W., and Long, S. R. (1986). A plant flavone, luteolin, induces expression of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes. Science 233, 977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.3738520

Phillips, D. A., Dakora, F. D., Sande, E., Joseph, C. M., and Zon, J. (1994). Synthesis, release and transmission of alfalfa signals to rhizobial symbionts. Plant Soil 161, 69–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02183086

Ramu, S. K., Peng, H. M., and Cook, D. R. (2002). Nod factor induction of reactive oxygen species production is correlated with expression of the early nodulin gene rip1 in Medicago truncatula. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15, 522–528. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.6.522

Redmond, J. W., Batley, M., Djordjevic, M. A., Innes, R. W., Kuempel, P. L., and Rolfe, B. G. (1986). Flavones induce expression of nodulation genes in Rhizobium. Nature 323, 632–635. doi: 10.1038/323632a0

Rossen, L., Shearman, C. A., Johnston, A. W., and Downie, J. A. (1985). The nodD gene of Rhizobium leguminosarum is autoregulatory and in the presence of plant exudate induces the nodA,B,C genes. EMBO J. 4, 3369–3373.

Roux, B., Rodde, N., Jardinaud, M. F., Timmers, T., Sauviac, L., Cottret, L., et al. (2014). An integrated analysis of plant and bacterial gene expression in symbiotic root nodules using laser-capture microdissection coupled to RNA sequencing. Plant J. 77, 817–837. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12442

Santos, R., Hérouart, D., Puppo, A., and Touati, D. (2000). Critical protective role of bacterial superoxide dismutase in Rhizobium–legume symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 38, 750–759. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02178.x

Schlaman, H. R., Horvath, B., Vijgenboom, E., Okker, R. J., and Lugtenberg, B. J. (1991). Suppression of nodulation gene expression in bacteroids of Rhizobium leguminosarum Biovar viciae. J. Bacteriol. 173, 4277–4287.

Smith, L. S., and Long, S. R. (1998). Requirements for syrM and nodD genes in the nodulation of M. truncatula by Rhizobium meliloti 1021. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11, 937–940. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.9.937

Soyano, T., Kouchi, H., Hirota, A., and Hayashi, M. (2013). NODULE INCEPTION directly targets NF-Y subunit genes to regulate essential processes of root nodule development in Lotus japonicus. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003352

Subramanian, S., Stacey, G., and Yu, O. (2007). Distinct, crucial roles of flavonoids during legume nodulation. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.06.006

Tadege, M., Wen, J., He, J., Tu, H., Kwak, Y., Eschstruth, A., et al. (2008). Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 54, 335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03418.x

Urbański, D. F., Małolepszy, A., Stougaard, J., and Andersen, S. U. (2012). Genome-wide LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion detection in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 69, 731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04827.x

van Brussel, A. A., Recourt, K., Pees, E., Spaink, H. P., Tak, T., Wijffelman, C. A., et al. (1990). A biovar-specific signal of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae induces increased nodulation gene-inducing activity in root exudate of Vicia sativa subsp. nigra. J. Bacteriol. 172, 5394–5401.

Watkins, J. M., Hechler, P. J., and Muday, G. K. (2014). Ethylene-induced flavonol accumulation in guard cells suppresses reactive oxygen species and moderates stomatal aperture. Plant Physiol. 164, 1707–1717. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233528

Wisniewski, J. P., Rathbun, E. A., Knox, J. P., and Brewin, N. J. (2000). Involvement of diamine oxidase and peroxidase in insolubilization of the extracellular matrix: implications for pea nodule initiation by Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13, 413–420. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.4.413

Xiao, T. T., Schilderink, S., Moling, S., Deinum, E. E., Kondorosi, E., Franssen, H., et al. (2014). Fate map of Medicago truncatula root nodules. Development 141, 3517–3528. doi: 10.1242/dev.110775

Zanetti, M. E., Blanco, F. A., Beker, M. P., Battaglia, M., and Aguilar, O. M. (2010). A C subunit of the plant nuclear factor NF-Y required for rhizobial infection and nodule development affects partner selection in the common bean-Rhizobium etli symbiosis. Plant Cell 22, 4142–4157. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079137

Zhou, Z., Sun, L., Zhao, Y., An, L., Yan, A., Meng, X., et al. (2013). Zinc Finger Protein 6 (ZFP6) regulates trichome initiation by integrating gibberellin and cytokinin signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 198, 699–708. doi: 10.1111/nph.12211

Keywords: infection threads, methoxychalcone, medicarpin, CCAAT-box, infection zone, nod genes, Nod factors, nodulation

Citation: Chen D-S, Liu C-W, Roy S, Cousins D, Stacey N and Murray JD (2015) Identification of a core set of rhizobial infection genes using data from single cell-types. Front. Plant Sci. 6:575. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00575

Received: 12 May 2015; Accepted: 13 July 2015;

Published: 28 July 2015.

Edited by:

Marc Libault, University of Oklahoma, USAReviewed by:

Ulrike Mathesius, Australian National University, AustraliaCopyright © 2015 Chen, Liu, Roy, Cousins, Stacey and Murray. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeremy D. Murray, John Innes Centre, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Norwich Research Park, Norwich, Norfolk NR4 7UH, UK,amVyZW15Lm11cnJheUBqaWMuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.