95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 23 January 2014

Sec. Plant Membrane Traffic and Transport

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00005

This article is part of the Research Topic A dynamic interplay between membranes and the cytoskeleton critical for cell development and signaling View all 10 articles

The actin cytoskeleton plays a key role in the plant morphogenesis and is involved in polar cell growth, movement of subcellular organelles, cell division, and plant defense. Organization of actin cytoskeleton undergoes dynamic remodeling in response to internal developmental cues and diverse environmental signals. This dynamic behavior is regulated by numerous actin-binding proteins (ABPs) that integrate various signaling pathways. Production of the signaling lipids phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidic acid affects the activity and subcellular distribution of several ABPs, and typically correlates with increased actin polymerization. Here we review current knowledge of the inter-regulatory dynamics between signaling phospholipids and the actin cytoskeleton in plant cells.

The plant actin cytoskeleton is a molecular scaffold that controls many aspects of cytoarchitecture including cytoplasmic streaming, movement and positioning of diverse organelles, or individual proteins. It also plays a prominent, albeit incompletely understood, role in endocytic and exocytic processes and has been implicated in cytokinesis, polar growth, and defense responses to pathogens (Higaki et al., 2007). Actin filaments are generated from monomeric actin subunits (G-actin) and arrayed into dynamic networks in plant cells; actin turnover and the formation of higher-order structures is tightly regulated by dozens of actin-binding proteins (ABPs). These proteins can be divided into several groups according to their binding properties and activities, e.g., monomeric G-ABPs; capping and severing proteins; side-binding proteins; and actin-nucleating factors (Staiger and Blanchoin, 2006; Henty-Ridilla et al., 2013).

To ensure proper spatial and temporal regulation of actin dynamics, the activity and binding properties of ABPs are further modulated by upstream-signaling molecules (reviewed, e.g., in Thomas et al., 2009; Blanchoin et al., 2010; Fu, 2010). Here we review the role of minor signaling membrane components, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), and phosphatidic acid (PA), that have been discovered as important regulators of actin dynamics in plant cells. In particular, we address the following subjects: (i) characteristics of PIP2 and PA that permit their function in cells; (ii) specific production of actin-regulating PIP2 and PA pools; (iii) current knowledge on the regulation of different ABPs mediated by direct interaction with PIP2 and/or PA; and (iv) putative crosstalk between PA and PIP2 in the regulation of actin dynamics.

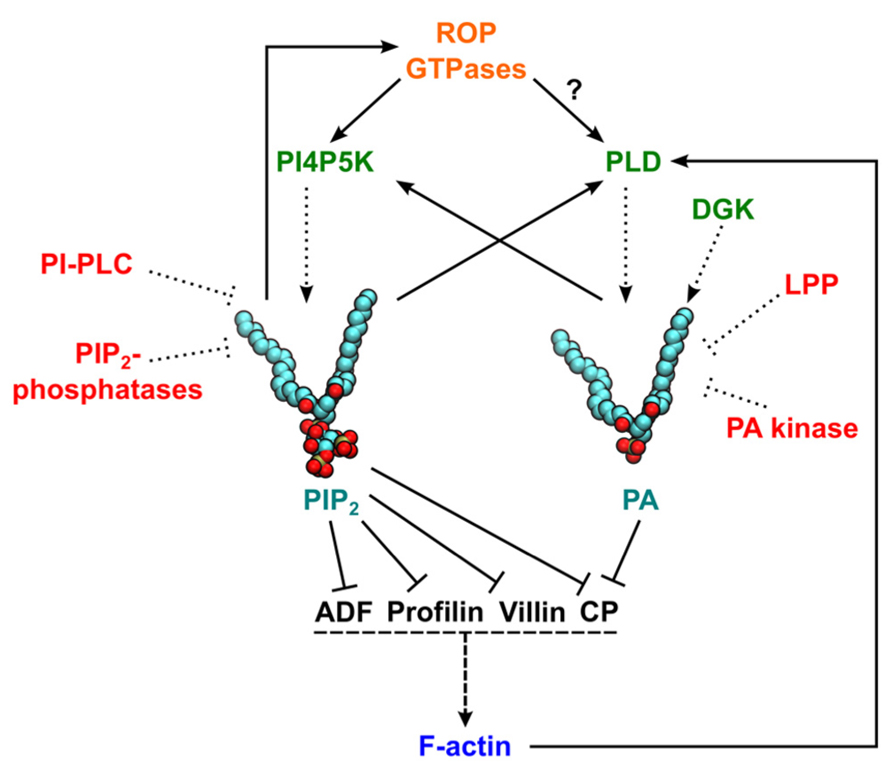

Although both PA and PIP2 are negatively charged (i.e., acidic) in the physiological pH range, they markedly differ in their structural and biophysical properties. PIP2 contains a bulky headgroup, with net charge ranging from –3 to –5 under physiological pH and an inverted conical shape that promotes positive curvature of membranes (Figure 1). Since total concentration of PIP2 in the plant plasma membrane is less than 1% (Munnik and Nielsen, 2011), PIP2 (together with other phosphoinositides, PPIs) is believed to function as an address label that defines membrane identity and as a landmark molecule for its protein partners, rather than having a general structural role in the lipid bilayer.

FIGURE 1. Schematic representation of actin regulation by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidic acid (PA). Solid lines represent pathways leading to activation (arrow ends) or inhibition (line ends). Dotted lines indicate pathways leading to PIP2/PA production/degradation. Dashed lines represent an induction of actin polymerization. A question mark indicates that experimental data are available only for non-plant cells. Enzymes generating PIP2 or PA are in green and proteins involved in phospholipid degradation or signaling attenuation are in red. In PIP2 and PA structural models, red and brown balls represent the oxygen and phosphorus atoms in headgroups, respectively, and carbon atoms are shown in cyan. ADF, actin-depolymerizing factor; CP, capping protein; F-actin, filamentous actin; DGK, diacylglycerol kinase; LPP, lipid phosphate phosphatases; PI4P5K, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase; PI-PLC, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C; PLD, phospholipase D; ROP, Rho of plants.

In contrast to the distinct structure of PIP2 that makes it very distinguishable in the membrane for its interaction partners, PA represents the simplest glycerophospholipid, consisting of a hydrophobic diacylglycerol (DAG) body and a single phosphate as the polar hydrophilic headgroup (Figure 1). PA is more abundant than PIP2 in the plant plasma membrane (usually between 5 and 10% of total phospholipids; Furt et al., 2010) and can change local properties of the lipid bilayer due to its cone-like shape, favoring negative membrane curvature (Kooijman et al., 2003; Testerink and Munnik, 2011). Interestingly, the specificity of PA interactions with its binding proteins is the result of a unique PA property called the electrostatic/hydrogen bond switch, where the negative charge of the PA headgroup is increased from –1 to –2 and stabilized upon formation of hydrogen bonds with arginine and lysine residues of effector proteins (Kooijman et al., 2007).

In addition to differences in polar headgroups, distinct membrane properties of PIP2 and PA may also result from different acyl compositions. In tobacco leaves, PA is predominantly made of palmitic and linoleic acid, whereas PIP2 contains mainly palmitic, stearic, and oleic acids (Furt et al., 2010).

Phosphoinositides biosynthesis begins with the formation of phosphatidylinositol (PI), which is produced by the condensation of cytidine-diphosphodiacylglycerol and D-myo-inositol in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Löfke et al., 2008). The inositol ring of PI can be further phosphorylated at D-3, D-4, and D-5 position by specific evolutionarily conserved lipid kinases (Brown and Auger, 2011). The key enzyme in PIP2 synthesis is phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PI4P5K). In Arabidopsis, 11 genes encoding PI4P5K isoforms were identified (Mueller-Roeber and Pical, 2002). These genes could be further divided into two subgroups based on their overall structure, one group containing AtPI4P5K1–9 and the other formed by AtPI4P5K10–11 (Ischebeck et al., 2010). PI4P5Ks have an essential role in root-hair growth, pollen development, and guard cell opening (Munnik and Nielsen, 2011). Intriguingly, a double mutant of PI4P5K10 and 11 has increased sensitivity to actin-monomer binding drug latrunculin B, whereas overexpression of these isoforms causes aggregation of apical actin fringe in tobacco pollen tubes (Ischebeck et al., 2011), suggesting that PIP2 produced by this group of PIP4P5Ks is specifically involved in the regulation of actin dynamics.

In addition to PPI formation, reduction in PPI levels is also likely to regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) is an enzyme that hydrolyzes PIP2 into DAG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3), and was shown to affect actin organization in Petunia pollen tubes by knockdown studies (Dowd et al., 2006). Moreover, two non-related families of phosphatases are present in plant genomes: inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases (5PTases), that can cleave both PIP2 and inositol polyphosphates, and PPI phosphatases containing SAC domain that preferentially cleave membrane PPIs. Interestingly, the fra3 mutant that has been identified as 5PTase15 implicated in controlling actin organization and secondary cell wall synthesis in fiber cells (Zhong et al., 2004). Actin disorganization was also shown in fra7 mutant, coding for SAC-bearing PPI phosphatase (Zhong et al., 2005).

In addition to ER-localized biosynthesis of PA that serves as a precursor for structural phospholipids and triacylglycerols, two distinct pathways can lead to formation of PA with signaling properties. The most studied pathway involves hydrolysis of structural phospholipids by phospholipase D (PLD), directly yielding PA. In comparison to yeast and animal genomes, the PLD family is expanded in plants with 12 genes in Arabidopsis and even more in other dicot and monocot genomes (Eliáš et al., 2002; Pleskot et al., 2012a). Interestingly, the PLDβ1 isoform from Arabidopsis and tobacco was found to interact directly with actin and is implicated in the regulation of actin polymerization (Kusner et al., 2003; Pleskot et al., 2010).

In addition to the PLD pathway, PA can be also produced by phosphorylation of DAG from the activity of diacylglycerol kinase (DGK). Intriguingly, “signaling” DAG in plant cells can be generated either from PIP2 via PI-PLC or from structural phospholipids via the activity of non-specific PLC (Munnik and Nielsen, 2011; Pokotylo et al., 2013), thus linking PPIs and PA signaling. The knowledge about plant DGKs is scarce and no molecular or genetic data are available that would support a role in actin regulation. However, several animal DGK isoforms have been implicated in actin regulation, and a plant DGK activity was found to be associated with F-actin in carrot cell cultures (Tan and Boss, 1992).

There are several different ways that PIP2 can affect actin polymerization, dynamics, and association with the membrane: through direct binding and regulation of distinct ABPs, indirectly through regulation of the activity and localization of ROP (Rho of plants) GTPases, or via recruiting scaffolding proteins to the plasma membrane (Zhang et al., 2012).

Actin-binding proteins were among the first proteins whose biological activity was shown to be regulated by PIP2 (reviewed in Zhang et al., 2012). There seems to be a clear distinction between inhibiting and activating properties of PIP2 in actin polymerization, such that all PIP2-sensitive G-actin-binding and actin-severing proteins are inactivated by PIP2, whereas for proteins acting in actin assembly or linking the filaments to the membrane, their interaction with PIP2 leads to increased actin polymerization and/or membrane attachment (Saarikangas et al., 2010). In contrast to the majority of PPI-binding non-cytoskeletal proteins, which have structurally well-defined PPI-binding motifs, like pleckstrin homology (PH), Phox homology (PX) or Fab-1, YGL023, Vps27, and EEA1 (FYVE) domains, most ABPs do not possess obvious structural modules, but they instead use patches of basic/aromatic amino acids, e.g., heterodimeric capping protein (CP) contains such clusters on the C-terminal parts of both subunits (Kim et al., 2007; Pleskot et al., 2012b, see also below for details).

A number of PPI-regulated ABPs have been studied in animal cells including members of ADF (actin-depolymerizing factor)/cofilin, profilin, twinfilin, CP, gelsolin, villin, α-actinin, vinculin, talin, spectrin, ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin), and actin nucleating protein families (Saarikangas et al., 2010). In plants, four distinct ABP classes (profilin, ADF/cofilin, CP, and villin) have been described to be regulated by PIP2 to date (Gungabissoon et al., 1998; Braun et al., 1999; Dong et al., 2001; Xiang et al., 2007).

Profilin is a globular protein of low molecular mass, which forms a 1:1 complex with G-actin (Kovar et al., 2000). Profilin suppresses spontaneous nucleation of actin and prevents assembly at the slow-growing, pointed end of actin filaments (Staiger and Blanchoin, 2006). In contrast to non-plant counterparts, plant profilin does not catalyze nucleotide exchange on actin (reviewed in Day et al., 2011). Profilin colocalizes with PIP2 at the tip of growing root hairs (Braun et al., 1999). Moreover, plant profilin directly binds PIP2(Kovar et al., 2001) and it could be speculated that similar to its animal homologs, profilin can then dissociate from profilin-G-actin complexes releasing free G-actin (Witke, 2004). Interestingly, plant profilin also inhibits the activity of PIP2-degrading enzyme, PI-PLC (Kovar et al., 2000).

Proteins of the ADF/cofilin family represent conserved ABPs across eukaryotes (Hussey et al., 2002). ADF/cofilin recycles actin monomers by severing and creating new filament ends (Andrianantoandro and Pollard, 2006; Henty et al., 2011). Zea mays (Zm) ADF3 directly binds and is inhibited by PIP2. Moreover, similar to the profilin-PIP2 interaction, the ZmADF3 binding of PIP2 suppresses the activity of PI-PLC (Gungabissoon et al., 1998). Similar findings were reported for ADF1 from lily pollen (Allwood et al., 2002), suggesting that PPI regulation is a common feature of plant ADF/cofilin isoforms.

Villin belongs to the ABP protein superfamily gelsolin/villin/fragmin and is composed of six gelsolin-homology domains at its core and a villin headpiece domain at its C-terminus. Arabidopsis contains five VILLIN genes, however, genes coding for gelsolin and fragmin are not present in model plant genomes. Interestingly, actin-severing activity of ABP29, a probable splice variant of the 135-kDa villin from lily, was shown to be inhibited by PIP2 (Xiang et al., 2007). However, the analogous regulation of full-length plant villin remains to be demonstrated.

Capping protein is a heterodimeric protein distributed across almost all eukaryotes (Pleskot et al., 2012b); it binds to the fast growing end of actin filaments, thus inhibiting polymerization. CP bound to actin filaments also protects against disassembly (Huang et al., 2003). Similar to animal cells, it was shown that the ability of Arabidopsis CP to bind actin fast-growing ends is inhibited PIP2 in vitro (Huang et al., 2006). However, unlike animal and yeast CPs, the Arabidopsis CP homolog has been also identified as a direct target of PA both in vitro and in vivo [see below for more details; (Huang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2012a)].

Rho of plants small GTPases are a plant-specific subfamily and sole members of the Rho/Rac/Cdc42 family of Ras-related G-proteins in plants, where they serve as “master switches” involved in diverse signaling and developmental pathways. Activated ROP variants are associated with the plasma membrane, where they are thought to control cell growth by coordinating actin organization and membrane trafficking (Mucha et al., 2011). Importantly, PIP2 was shown to colocalize with ROP GTPases at the apical plasma membrane of tobacco pollen tube and pollen ROP physically interacts with PI4P5K activity (Kost et al., 1999; Yalovsky et al., 2008). Importantly, type II plant ROP GTPases have a polybasic motif at the C-terminal part of the protein, which is necessary for plasma membrane localization (Lavy and Yalovsky, 2006). It is therefore tempting to speculate that this polybasic motif binds PIP2 directly, as described for many members of the human small GTPase family (Heo et al., 2006). Furthermore, it was recently shown that PIP4P5K regulates actin dynamics in pollen tubes by counteracting Rho-GDI (Rho-guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor), thereby regulating the pool of membrane-localized ROP GTPases (Ischebeck et al., 2011).

In the last decade, several studies describe changes in signaling PA levels that generate a pronounced effect on plant actin cytoskeleton organization (Lee et al., 2003; Motes et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2006; Apostolakos et al., 2008; Pleskot et al., 2010, 2012a). Given the profound effect of PA production on actin polymerization in eukaryotes, it is surprising that no ABPs regulated by PA were described in animal or yeast cells. Indeed, the PA effect on actin in animals appears to be mainly indirect, by controlling production of PIP2 through PI4P5Ks [(Roach et al., 2012); and see below]. In plant cells on the other hand, CP was found to be regulated by PA as well as PPIs in vitro (Huang et al., 2006). Furthermore, the critical role of PA in plant CP regulation was confirmed by utilizing cp knockdown mutants (Li et al., 2012a,b). Structural aspects of the AtCP inhibition by PA highlight a key role for the C-terminal part of CPα subunit, as demonstrated through molecular dynamics simulations (Pleskot et al., 2012b). The fact that a direct interaction between actin and PLDβ exists in plant cells (Pleskot et al., 2010) leads to the hypothesis of a positive feedback loop model for actin dynamics regulation by PLDβ and PA. Briefly, intracellular or intercellular signals cause activation of PLDβ and subsequently increase the local PA concentration. PA binds CP and prevents its binding to the fast growing end of actin filaments, thus promoting actin polymerization. Newly formed actin filaments promote PLDβ activity, leading to local enhancement of PA concentration and further enhancement of actin assembly (Pleskot et al., 2010, 2013).

During the last 20 years, multiple direct and indirect interactions between PIP2- and PA-centered signaling pathways and the regulation of actin dynamics have been revealed. Despite the fact that the regulation of actin dynamics is a point of convergence for many signaling pathways and exhibits complex feedback regulation (Figure 1), general conclusions can be drawn: The elevation of PIP2 and/or PA levels increases both density and complexity of the actin network and conversely the inhibition of PA/PIP2 production leads to actin filament disruption. Although many similarities can be found in ABP–phospholipid regulation between plant and animal cells, there is one principal difference: in plants, PIP2 levels are 10 times lower than PA levels (Drøbak, 1993; Zonia and Munnik, 2004). It is therefore tempting to speculate that many plant ABPs adapted to the distinct levels of PA and PIP2. It might be expected that additional ABPs interact with PA and/or PIP2 in plant cells, and this should be a topic for future exploration.

Many published reports on ABP–phospholipid regulation assume that the protein–lipid bilayer interaction is mono-specific, i.e., a single species of lipid is responsible for recruiting a given ABP to the membrane. However, work from animal and yeast cells has shown that a mono-specific reaction is the exception rather than the rule: for the majority of lipid effectors, membrane translocation probably depends both on a specific lipid but also on the surrounding lipid environment (Moravcevic et al., 2012). Indeed, several recent computational studies, albeit not on proteins involved in the regulation of the actin dynamics, show the involvement of other phospholipids for protein domains previously thought to function in a mono-specific way. Kooijman et al. (2007) experimentally described the positive effect of phosphatidylethanolamine on the PA binding by AtPDK1, AtCTR1, and Raf-1. Similar results were obtained for the binding of PPIs by PH, PX, and FYVE domains (Psachoulia and Sansom, 2008, 2009; Lumb et al., 2011). Several PA-binding proteins also have affinity for different PPIs. The binding of another signaling phospholipid could be mediated by the same domain, as in the case of AtPDK1 and p47phox PX domain, or through a completely distinct domain, for example the C1 and C2 domains of mammalian PKCε (Testerink and Munnik, 2011), but the molecular details are largely missing. Interestingly, the C1-domain, a canonical DAG-binding motif, binds more strongly to DAG embedded in the negatively charged membrane and DAG-mediated targeting of effector proteins thus seems to be also enhanced by synergistic binding to acidic phospholipids, such as PA and PIP2 (Colón-González and Kazanietz, 2006). From this point of view, dual regulation of plant CP by both PA and PIP2 (Huang et al., 2006) might represent just the tip of an iceberg.

A cooperative effect between PA and PIP2 in the regulation of the actin dynamics could be also indirect. Recently, Roach et al. (2012) described the ability of PA to activate PI4P5K and the authors showed the crucial importance of membrane targeting of PI4P5K by PA in the regulation of actin reorganization in animal cells. The activation of kinase activity by PA was shown for AtPI4P5K1 (Perera et al., 2005). Given the fact that several PLD isoforms are activated by PIP2(Li et al., 2009), one can expect that a vivid crosstalk between PA and PIP2 signaling to the actin cytoskeleton exists in all eukaryotic cells.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Work on multiscale analysis of phospholipid signaling in plant cells is supported by the Czech Grant Agency grant GACR 13-19073S to Martin Potocký. Work on capping protein and its role in stochastic actin dynamics in the lab of Christopher J. Staiger was funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Physical Biosciences Section of the Basic Energy Sciences Program under contract grant no. DE-FG02-09ER15526.

Allwood, E. G., Anthony, R. G., Smertenko, A. P., Reichelt, S., Drobak, B. K., Doonan, J. H., et al. (2002). Regulation of the pollen-specific actin-depolymerizing factor LlADF1. Plant Cell 14, 2915–2927. doi: 10.1105/tpc.005363

Andrianantoandro, E., and Pollard, T. D. (2006). Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol. Cell 24, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006

Apostolakos, P., Panteris, E., and Galatis, B. (2008). The involvement of phospholipases C and D in the asymmetric division of subsidiary cell mother cells of Zea mays. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 65, 863–875. doi: 10.1002/cm.20308

Blanchoin, L., Boujemaa-Paterski, R., Henty, J. L., Khurana, P., and Staiger, C. J. (2010). Actin dynamics in plant cells: a team effort from multiple proteins orchestrates this very fast-paced game. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.09.013

Braun, M., Baluška, F., von Witsch, M., and Menzel, D. (1999). Redistribution of actin, profilin and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate in growing and maturing root hairs. Planta 209, 435–443. doi: 10.1007/s004250050746

Brown, J., and Auger, K. (2011). Phylogenomics of phosphoinositide lipid kinases: perspectives on the evolution of second messenger signaling and drug discovery. BMC Evol. Biol. 11:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-4

Colón-González, F., and Kazanietz, M. G. (2006). C1 domains exposed: from diacylglycerol binding to protein-protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 827–837. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.001

Day, B., Henty, J. L., Porter, K. J., and Staiger, C. J. (2011). The pathogen-actin connection: a platform for defense signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49, 483–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095426

Dong, C.-H., Xia, G.-X., Hong, Y., Ramachandran, S., Kost, B., and Chua, N.-H. (2001). ADF proteins are involved in the control of flowering and regulate F-actin organization, cell expansion, and organ growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1333–1346. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010051

Dowd, P. E., Coursol, S., Skirpan, A. L., Kao, T.-H., and Gilroy, S. (2006). Petunia phospholipase C1 is involved in pollen tube growth. Plant Cell 18, 1438–1453. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041582

Drøbak, B. K. (1993). Plant phosphoinositides and intracellular signaling. Plant Physiol. 102, 705–709. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.705

Eliáš, M., Potocký, M., Cvrčková, F., and Žárský, V. (2002). Molecular diversity of phospholipase D in angiosperms. BMC Genomics 3:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-3-2

Furt, F., König, S., Bessoule, J.-J., Sargueil, F., Zallot, R., Stanislas, T., et al. (2010). Polyphosphoinositides are enriched in plant membrane rafts and form microdomains in the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 152, 2173–2187. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149823

Fu, Y. (2010). The actin cytoskeleton and signaling network during pollen tube tip growth. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00922.x

Gungabissoon, R. A., Jiang, C.-J., Drøbak, B. K., Maciver, S. K., and Hussey, P. J. (1998). Interaction of maize actin-depolymerising factor with actin and phosphoinositides and its inhibition of plant phospholipase C. Plant J. 16, 689–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00339.x

Henty, J. L., Bledsoe, S. W., Khurana, P., Meagher, R. B., Day, B., Blanchoin, L., et al. (2011). Arabidopsis actin depolymerizing factor4 modulates the stochastic dynamic behavior of actin filaments in the cortical array of epidermal cells. Plant Cell 23, 3711–3726. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090670

Henty-Ridilla, J. L., Li, J., Blanchoin, L., and Staiger, C. J. (2013). Actin dynamics in the cortical array of plant cells. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.10.012

Heo, W. D., Inoue, T., Park, W. S., Kim, M. L., Park, B. O., Wandless, T. J., et al. (2006). PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science 314, 1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389

Higaki, T., Sano, T., and Hasezawa, S. (2007). Actin microfilament dynamics and actin side-binding proteins in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.012

Huang, S., Blanchoin, L., Kovar, D. R., and Staiger, C. J. (2003). Arabidopsis capping protein (AtCP) is a heterodimer that regulates assembly at the barbed ends of actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44832–44842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306670200

Huang, S., Gao, L., Blanchoin, L., and Staiger, C. J. (2006). Heterodimeric capping protein from Arabidopsis is regulated by phosphatidic acid. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1946–1958. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0840

Hussey, P. J., Allwood, E. G., and Smertenko, A. P. (2002). Actin-binding proteins in the Arabidopsis genome database: properties of functionally distinct plant actin-depolymerizing factors/cofilins. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 357, 791–798. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1086

Ischebeck, T., Seiler, S., and Heilmann, I. (2010). At the poles across kingdoms: phosphoinositides and polar tip growth. Protoplasma 240, 13–31. doi: 10.1007/s00709-009-0093-0

Ischebeck, T., Stenzel, I., Hempel, F., Jin, X., Mosblech, A., and Heilmann, I. (2011). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate influences Nt-Rac5-mediated cell expansion in pollen tubes of Nicotiana tabacum. Plant J. 65, 453–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04435.x

Kim, K., McCully, M. E., Bhattacharya, N., Butler, B., Sept, D., and Cooper, J. A. (2007). Structure/function analysis of the interaction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate with actin-capping protein. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5871–5879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609850200

Kooijman, E. E., Chupin, V., de Kruijff, B., and Burger, K. N. J. (2003). Modulation of membrane curvature by phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid. Traffic 4, 162–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00086.x

Kooijman, E. E., Tieleman, D. P., Testerink, C., Munnik, T., Rijkers, D. T. S., Burger, K. N. J., et al. (2007). An electrostatic/hydrogen bond switch as the basis for the specific interaction of phosphatidic acid with proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11356–11364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609737200

Kost, B., Lemichez, E., Spielhofer, P., Hong, Y., Tolias, K., Carpenter, C., et al. (1999). Rac homologues and compartmentalized phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate act in a common pathway to regulate polar pollen tube growth. J. Cell Biol. 145, 317–330. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.317

Kovar, D. R., Drøbak, B. K., Collings, D. A., and Staiger, C. J. (2001). The characterization of ligand-specific maize (Zea mays) profilin mutants. Biochem. J. 358, 49–57. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580049

Kovar, D. R., Drøbak, B. K., and Staiger, C. J. (2000). Maize profilin isoforms are functionally distinct. Plant Cell 12, 583–598. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.583

Kusner, D. J., Barton, J. A., Qin, C., Wang, X., and Iyer, S. S. (2003). Evolutionary conservation of physical and functional interactions between phospholipase D and actin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 412, 231–241. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00052-3

Lavy, M., and Yalovsky, S. (2006). Association of Arabidopsis type-II ROPs with the plasma membrane requires a conserved C-terminal sequence motif and a proximal polybasic domain. Plant J. 46, 934–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02749.x

Lee, S., Park, J., and Lee, Y. (2003). Phosphatidic acid induces actin polymerization by activating protein kinases in soybean cells. Mol. Cells 15, 313–319.

Li, J., Henty-Ridilla, J. L., Huang, S., Wang, X., Blanchoin, L., and Staiger, C. J. (2012a). Capping protein modulates the dynamic behavior of actin filaments in response to phosphatidic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 3742–3754. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.103945

Li, J., Pleskot, R., Henty-Ridilla, J. L., Blanchoin, L., Potocký, M., and Staiger, C. J. (2012b). Arabidopsis capping protein senses cellular phosphatidic acid levels and transduces these into changes in actin cytoskeleton dynamics. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 1727–1730. doi: 10.4161/psb.22472

Li, M., Hong, Y., and Wang, X. (2009). Phospholipase D- and phosphatidic acid-mediated signaling in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.017

Löfke, C., Ischebeck, T., König, S., Freitag, S., and Heilmann, I. (2008). Alternative metabolic fates of phosphatidylinositol produced by phosphatidylinositol synthase isoforms in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 413, 115–124. doi: 10.1042/bj20071371

Lumb, C. N., He, J., Xue, Y., Stansfeld, P. J., Stahelin, R. V., Kutateladze, T. G., et al. (2011). Biophysical and computational studies of membrane penetration by the GRP1 pleckstrin homology domain. Structure 19, 1338–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.04.010

Moravcevic, K., Oxley, C. L., and Lemmon, M. A. (2012). Conditional peripheral membrane proteins: facing up to limited specificity. Structure 20, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.11.012

Motes, C. M., Pechter, P., Yoo, C. M., Wang, Y.-S., Chapman, K. D., and Blancaflor, E. B. (2005). Differential effects of two phospholipase D inhibitors, 1-butanol and N-acylethanolamine, on in vivo cytoskeletal organization and Arabidopsis seedling growth. Protoplasma 226, 109–123. doi: 10.1007/s00709-005-0124-4

Mucha, E., Fricke, I., Schaefer, A., Wittinghofer, A., and Berken, A. (2011). Rho proteins of plants – Functional cycle and regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.009

Mueller-Roeber, B., and Pical, C. (2002). Inositol phospholipid metabolism in Arabidopsis. Characterized and putative isoforms of inositol phospholipid kinase and phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Plant Physiol. 130, 22–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.004770

Munnik, T., and Nielsen, E. (2011). Green light for polyphosphoinositide signals in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.06.007

Perera, I. Y., Davis, A. J., Galanopoulou, D., Im, Y. J., and Boss, W. F. (2005). Characterization and comparative analysis of Arabidopsis phosphatidylinositol phosphate 5-kinase 10 reveals differences in Arabidopsis and human phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases. FEBS Lett. 579, 3427–3432. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.018

Pleskot, R., Li, J., Žárský, V., Potocký, M., and Staiger, C. J. (2013). Regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics by phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.04.005

Pleskot, R., Pejchar, P., Bezvoda, R., Lichtscheidl, I. K., Wolters-Arts, M., Marc, J., et al. (2012a). Turnover of phosphatidic acid through distinct signalling pathways affects multiple aspects of tobacco pollen tube tip growth. Front. Plant Sci. 3:54. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00054

Pleskot, R., Pejchar, P., Žárský, V., Staiger, C. J., and Potocký, M. (2012b). Structural insights into the inhibition of actin-capping protein by interactions with phosphatidic acid and phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8:e1002765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002765

Pleskot, R., Potocký, M., Pejchar, P., Linek, J., Bezvoda, R., Martinec, J., et al. (2010). Mutual regulation of plant phospholipase D and the actin cytoskeleton. Plant J. 62, 494–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04168.x

Pokotylo, I., Pejchar, P., Potocký, M., Kocourková, D., Krčková, Z., Ruelland, E., et al. (2013). The plant non-specific phospholipase C gene family. Novel competitors in lipid signalling. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 62–79. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.09.001

Psachoulia, E., and Sansom, M. S. P. (2008). Interactions of the pleckstrin homology domain with phosphatidylinositol phosphate and membranes: characterization via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 47, 4211–4220. doi: 10.1021/bi702319k.

Psachoulia, E., and Sansom, M. S. P. (2009). PX- and FYVE-mediated interactions with membranes: simulation studies. Biochemistry 48, 5090–5095. doi: 10.1021/bi900435m

Roach, A. N., Wang, Z., Wu, P., Zhang, F., Chan, R. B., Yonekubo, Y., et al. (2012). Phosphatidic acid regulation of PIPKI is critical for actin cytoskeletal reorganization. J. Lipid Res. 53, 2598–2609. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M028597

Saarikangas, J., Zhao, H., and Lappalainen, P. (2010). Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton-plasma membrane interplay by phosphoinositides. Physiol. Rev. 90, 259–289. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2009

Staiger, C. J., and Blanchoin, L. (2006). Actin dynamics: old friends with new stories. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.013

Tan, Z., and Boss, W. F. (1992). Association of phosphatidylinositol kinase, phosphatidylinositol monophosphate kinase, and diacylglycerol kinase with the cytoskeleton and F-actin fractions of carrot (Daucus carota L.) cells grown in suspension culture. Plant Physiol. 100, 2116–2120. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.4.2116

Testerink, C., and Munnik, T. (2011). Molecular, cellular, and physiological responses to phosphatidic acid formation in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 2349–2361. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err079

Thomas, C., Tholl, S., Moes, D., Dieterle, M., Papuga, J., Moreau, F., et al. (2009). Actin bundling in plants. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 940–957. doi: 10.1002/cm.20389

Witke, W. (2004). The role of profilin complexes in cell motility and other cellular processes. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.003

Xiang, Y., Huang, X., Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Liu, Q., Hussey, P. J., et al. (2007). ACTIN BINDING PROTEIN29 from Lilium pollen plays an important role in dynamic actin remodeling. Plant Cell 19, 1930–1946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048413

Yalovsky, S., Bloch, D., Sorek, N., and Kost, B. (2008). Regulation of membrane trafficking, cytoskeleton dynamics, and cell polarity by ROP/RAC GTPases. Plant Physiol. 147, 1527–1543. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122150

Zhang, L., Mao, Y. S., Janmey, P. A., and Yin, H. L. (2012). “Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5 bisphosphate and the actin cytoskeleton,” in Phosphoinositides II: The Diverse Biological Functions, eds T. Balla, M. Wymann, and J. D. York. (Netherlands: Springer), 177–215.

Zhong, R., Burk, D. H., Morrison, W. H., and Ye, Z.-H. (2004). FRAGILE FIBER3, an Arabidopsis gene encoding a type II inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, is required for secondary wall synthesis and actin organization in fiber cells. Plant Cell 16, 3242–3259. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.027466

Zhong, R., Burk, D. H., Nairn, C. J., Wood-Jones, A., Morrison, W. H., and Ye, Z.-H. (2005). Mutation of SAC1, an Arabidopsis SAC domain phosphoinositide phosphatase, causes alterations in cell morphogenesis, cell wall synthesis, and actin organization. Plant Cell 17, 1449–1466. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031377

Keywords: actin, actin-binding proteins, capping protein, cytoskeleton, phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, phospholipase D, signaling

Citation: Pleskot R, Pejchar P, Staiger CJ and Potocký M (2014) When fat is not bad: the regulation of actin dynamics by phospholipid signaling molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 5:5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00005

Received: 26 November 2013; Paper pending published: 19 December 2013;

Accepted: 04 January 2014; Published online: 23 January 2014.

Edited by:

Clément Thomas, Public Research Centre for Health, LuxembourgReviewed by:

Joshua Blakeslee, The Ohio State University, USACopyright © 2014 Pleskot, Pejchar, Staiger and Potocký. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Potocký, Institute of Experimental Botany, v. v. i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rozvojová 263, 165 02 Prague 6, Czech Republic e-mail:cG90b2NreUB1ZWIuY2FzLmN6

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.