95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 18 June 2013

Sec. Plant Pathogen Interactions

Volume 4 - 2013 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00204

This article is part of the Research Topic Induced plant responses to microbes and insects View all 32 articles

In nature, the root systems of most plants develop intimate symbioses with glomeromycotan fungi that assist in the acquisition of mineral nutrients and water through uptake from the soil and direct delivery into the root cortex. Root systems are endowed with a strong, environment-responsive architectural plasticity that also manifests itself during the establishment of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses, predominantly in lateral root proliferation. In this review, we collect evidence for the idea that AM-induced root system remodeling is regulated at several levels: by AM fungal signaling molecules and by changes in plant nutrient status and distribution within the root system.

When plants made the transition from freshwater to terrestrial environments more than 400 million years ago, fundamental morphological changes were needed for the acquisition of mineral nutrients from the soil instead of from the aqueous substratum. Preceding the development of complex root systems the alliance with symbiotic fungi such as the Glomeromycetes and Mucoromycotina is believed to have greatly assisted this transition (Humphreys et al., 2010; Bidartondo et al., 2012; Field et al., 2012, and citations therein). The aseptate hyphal network of the glomeromycotan fungi functions as a mineral nutrient-transfer pipeline from the soil-exploring extraradical mycelium to the intracellularly colonized plant cell. Extensively branched tree-like fungal haustoria, the arbuscules, form within living plant cells and are the site of mineral nutrient delivery. It is widely accepted that these hyphal conduits have served mineral nutrient uptake by ancestral rootless gametophytes and continue to do so on today’s complexly rooted sporophytes. Liverworts constitute the earliest diverging plant lineage known (for recent review, see Jones and Dolan, 2012), that supports the development of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses with Glomeromycetes. The fungus enters via the rhizoid, develops arbuscules within the green thallus parenchyma (Russell and Bulman, 2005; Ligrone et al., 2007; Hata et al., 2010) and confers nutritional benefit to the plant host (Humphreys et al., 2010). In higher plants, arbuscules develop in root cortex cells where they deliver inorganic phosphate to the plant (Javot et al., 2007a; Yang et al., 2012). The extant ability of AM fungal species to equivalently colonize thallus parenchyma and root cortex suggests the genetic repertoire of AM fungi to ascertain a seamless adaption from ancient to newly invented organs and the two participating plant cell types to represent sufficiently similar niches for colonization. Within the highly patterned “modern” root system, arbuscular colonization is restricted to cortex cells.

Root systems consist of individual modules with different function: the shoot-born dicotyledon tap roots and monocotyledon crown roots (CRs) are mainly involved in anchorage and support whereas lateral roots mediate nutrient uptake (McCully and Canny, 1988). Root system architecture displays a high developmental plasticity in response to environmental stimuli such as nutrient and humidity levels or temperature (Lopez-Bucio et al., 2003; Osmont et al., 2007; Hodge, 2009). Importantly, among other biota AM fungi influence root system architecture, most prominently, by enhancing lateral root formation. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on the selective colonization of root types by AM fungi and its impact on root architectural changes, which we propose is regulated at multiple levels.

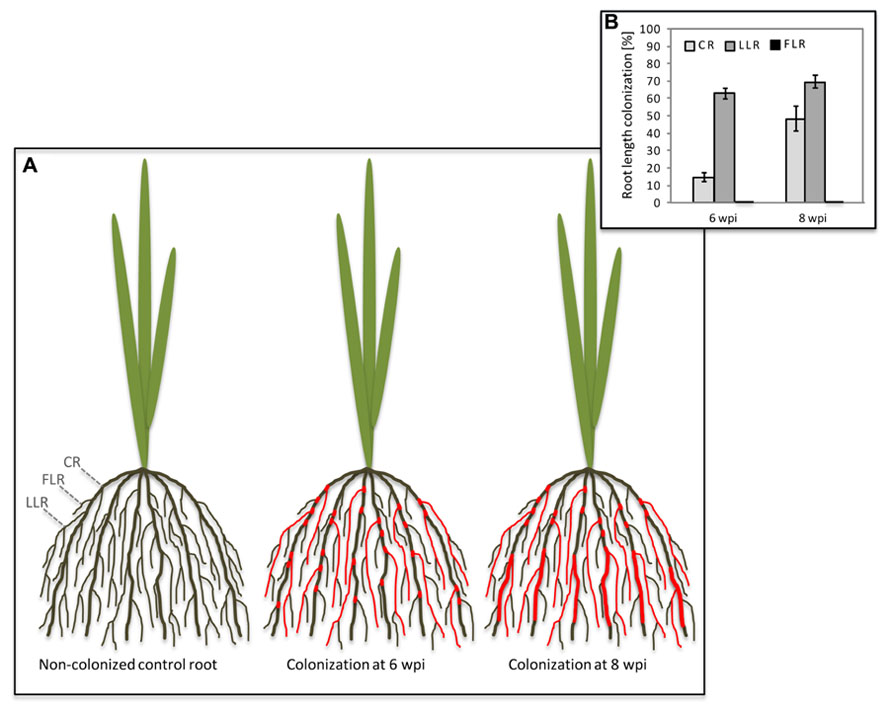

In both di- and monocotyledon root systems AM colonization is not evenly distributed since AM fungi preferentially colonize lateral roots and rather neglect dicotyledon primary roots or monocotyledon CRs (Figure 1; Hooker et al., 1992; Gutjahr et al., 2009a). Intuitively, this might be due to a higher sturdiness and lignin content in shoot-born roots with anchoring function that are more challenging to penetrate than the young expanding, and therefore softer tissue of growing lateral roots (Hepper, 1985; Amijee et al., 1993). Consistently, rigid CRs of rice are mainly colonized in patches close to lateral roots or emerging lateral root primordia (Gutjahr et al., 2009a). However, longer periods of plant co-cultivation with AM fungi increase the percentage of CR length colonized (Figure 1). It has been shown in maize that phosphate starvation stress leads to an increased transcription of genes involved in secondary cell wall biosynthesis (Calderon-Vazquez et al., 2008). Phosphate supply through AM fungi reduces starvation and might thus contribute to a decrease in secondary cell wall biosynthesis in CRs, thereby possibly facilitating further colonization when symbiotic phosphate transfer had conferred the effect. Also the colonization of the liverwort Conocephalum conicum leads to the disappearance of thallus cell wall autofluorescence at infected sites, indicating a localized decrease in cell wall phenolics (Ligrone et al., 2007). Similar to rice, also in soybean colonization was described to be particularly evident at points of lateral roots emergence. Corresponding spatial expression patterns of soluble acid invertase and sucrose synthase genes suggested an enhanced carbohydrate supply to the emerging and elongating laterals to account for this localized fungal root invasion (Blee and Anderson, 2002). Interestingly, lateral roots exhibit an increased responsiveness to AM fungal signaling molecules as evidenced by activation of a pENOD11-GUS transgene in Medicago hairy roots (Kosuta et al., 2003). Thus they might induce the symbiotic program more swiftly and promote colonization more readily than other root types.

FIGURE 1. Colonization of rice crown roots by Glomus intraradices upon prolonged co-cultivation. (A) Schematic illustration of the rice root system with crown roots (CRs), large lateral roots (LLRs) and fine lateral roots (FLRs). Colonization of the different root types is indicated by red color. At 6 weeks post-inoculation (wpi), CR show fungal colonization at the site of lateral root emergence; at 8 wpi, the CRs are normally colonized. (B) Percent root length colonization of rice CR, LLR, and FLR was determined at 6 and 8 wpi with Glomus intraradices. Mean values and SE of four biological replicates are shown.

An unequal distribution of AM colonization is particularly evident in rice root systems, that are equipped with two types of lateral roots, the strongly colonized large lateral roots (LLRs) and the fine lateral roots (FLRs), which lack cortex tissue (Rebouillat et al., 2009), and are therefore not able to host arbuscules (Gutjahr et al., 2009a). While absence of arbuscules from FLRs was predictable, the absence of fungal hyphopodium differentiation is surprising and implies that FLRs are not recognized by the fungus (Figure 1; Gutjahr et al., 2009a), possibly due to differences in either their surface composition or exudation of diffusible signals. Cutin monomers have recently been shown to induce hyphopodium formation on Medicago truncatula roots (Wang et al., 2012). Although not yet confirmed for rice, it is an attractive possibility that FLRs release insufficient amounts of cutin or related compounds. The chemical composition of the rhizodermal surface of any plant species is not well described but there is evidence from Arabidopsis that it differs among root zones (Kosma et al., 2012). This is exemplified by rhizoplane bacteria, that accumulate in species-specific patterns on the Arabidopsis root surface (Bulgarelli et al., 2012; Lundberg et al., 2012). These patterns are likely at least in part evoked by localized chemical surface composition or differential exudation patterns. Strigolactones are constitutively exuded from higher plant roots and rhizoids of bryophytic gametophytes (Akiyama et al., 2005; Delaux et al., 2012). They induce the metabolic activity of AM fungi and provide a directional cue to guide the fungus to colonizable tissue (Parniske, 2005; Besserer et al., 2006). PDR1 (pleiotropic drug resistance protein 1), a strigolactone ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-exporter in Petunia is expressed in hypodermal passage cells of lateral roots only (Kretzschmar et al., 2012). This might explain – at least for dicotyledons – why AM fungi are firstly attracted to lateral roots. It remains an intriguing open question whether an orthologous strigolactone transporter is expressed in outer cell layers of rice FLRs.

Numerous studies report root system changes in response to arbuscular mycorrhiza leading to an increased root branching and root system volume (reviewed in Hodge et al., 2009; Sukumar et al., 2013) but also reductions in root branching and length were detected (Hetrick, 1991). The basis of the observed differences is not clear but could be related to the studied plant species or the varying growth conditions. Diverging AM induced root system changes across different maize or soybean cultivars, grown under the same condition, suggested that at least part of the response is subject to genetic variation (Zhu et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2011). Although not systematically investigated an influence of the fungal genotype on the type and extend of root system remodeling can also be expected (Veresoglou et al., 2012). Yano et al. (1996) reported the induction of lateral root formation to be a highly localized response. AM inoculation of only one half of a split-root system of peanut and pigeon pea resulted in a higher number of lateral roots in the inoculated as compared to the non-inoculated half. However, systemic inhibitory or stimulatory effects on lateral root proliferation were not examined. The power of AM colonization over lateral root development was demonstrated in knock-down Lotus japonicus hairy root cultures of the putative transcription factor gene meristem and arbuscular mycorrhiza induced (LjMAMI) (Volpe et al., 2013). Here, colonization by AM fungi rescues the reduced lateral root growth phenotype and restores wild-type root system morphology. However, the most dramatic influence of AM colonization on root system architecture was found in the maize mutant lateral rootless1 (lrt1) that lacks embryonic lateral roots (Hochholdinger and Feix, 1998). Inoculation with AM fungi-induced bushy lateral roots even at elevated phosphate levels (Paszkowski and Boller, 2002). Taken together these data indicate that AM fungi trigger a signaling pathway that bypasses the default lateral root developmental control exerted by MAMI and/or LRT1.

Root system architectural changes in response to AM colonization are regulated on at least two levels as evidenced by their induction prior to or after establishment of AM colonization (Berta et al., 1990, 1995; Maillet et al., 2011; Mukherjee and Ane, 2011).

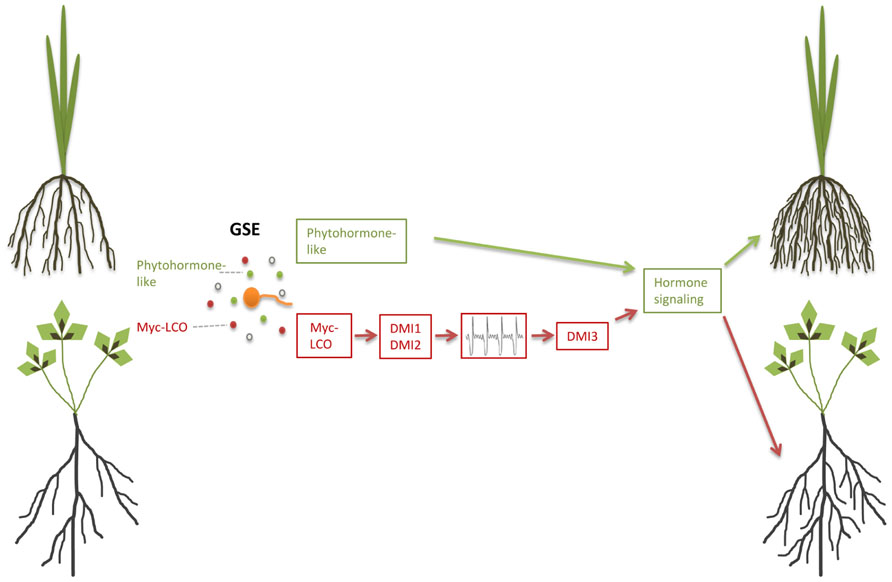

In the legume M. truncatula, germinating AM fungal spores that were separated from the root by a semipermeable membrane induced lateral root formation, indicating that diffusible signals released by these spores activate the lateral root developmental program (Olah et al., 2005). This is in agreement with the observation that the recently identified lipochitooligosaccharide Myc factors (Myc-LCOs) also induce lateral root formation in M. truncatula (Figure 2; Maillet et al., 2011). Intra-radical colonization of angiosperm roots is dependent on a signal transduction pathway, which includes Ca2+-oscillations as a second messenger and is also required for nodulation and accommodation of rhizobia and therefore named the common SYM pathway (for a recent review, see Singh and Parniske, 2012; Gutjahr and Parniske, 2013; Venkateshwaran et al., 2013). Lateral root induction by the presence of AM fungi was dependent only on DMI1 (POLLUX) and DMI2 (SYMRK), two genes that act upstream of Ca2+-spiking as part of the common SYM pathway (Olah et al., 2005). By contrast, Myc-LCO-mediated lateral root induction, additionally required the third common SYM gene DMI3 (CCamK), that acts downstream of Ca2+-spiking (Maillet et al., 2011) and is also required for rhizobial Nod factor-mediated lateral root induction (Olah et al., 2005). This raises the question whether germinating spore exudates (GSEs) also contain diffusible signaling molecules other than Myc-LCOs that do not require DMI3, but signal through alternative components downstream of DMI1 and DMI2 to induce lateral root formation in legumes. Lateral root development might be sustained by enhanced carbon accumulation that has been described in GSE-stimulated Lotus japonicus roots to be dependent on CASTOR, another SYM pathway component upstream of Ca2+-spiking (Gutjahr et al., 2009b).

FIGURE 2. Pre-symbiotic induction of lateral root formation in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Germinating spore exudates (GSE) contain Myc-LCOs and possibly phytohormone-like compounds. Perception of Myc-LCOs leads to lateral root induction in Medicago truncatula, which requires the common symbiosis signaling components DMI1, DMI2, and DMI3 (brown pathway). The green pathway hypothesizes phytohormone-like signaling to operate either downstream or independent of common symbiosis signaling in M. truncatula and rice, respectively.

Remarkably, the monocot rice does not require the common SYM genes CASTOR, DMI1 (POLLUX), and DMI3 (CCAMK) for lateral root induction by GSEs (Gutjahr et al., 2009a; Mukherjee and Ane, 2011). It is intriguing whether this is due to a fundamental genetic difference between monocotyledons and dicotyledons or whether legumes, due to their specific genetic layout, that grants the development of nodules, have incorporated the common SYM pathway into a regulatory network, that directs development of all root accessory organs. Congruent with the latter hypothesis, the Lotus japonicus mutant hypernodulation aberrant root formation 1 (har1), that hypernodulates and is hypercolonized by AM fungi, constitutively forms supernumerary lateral roots (Solaiman et al., 2000; Wopereis et al., 2000; Nishimura et al., 2002).

Lateral root formation is regulated by auxin in conjunction with other phytohormone signaling pathways (Nibau et al., 2008). Impairment of pre-symbiotic lateral root induction in hairy root culture of the auxin-resistant diageotropica tomato mutant suggests that Myc factor-dependent lateral root induction is similarly channeled into the auxin-controlled developmental outcome (Hanlon and Coenen, 2010). Ectomycorrhizal fungi such as Laccaria bicolor and Tuber melanosporum trigger the production of lateral roots prior to colonization through the stimulation of auxin signaling, likely due to their production and release of auxin and ethylene or other volatile compounds (Rupp et al., 1989; Karabaghli-Degron et al., 1998; Ivanchenko et al., 2008; Felten et al., 2009, Felten et al., 2010; Splivallo et al., 2009; Sukumar et al., 2013). Likewise it is possible that also AM fungi produce plant hormones such as auxin and ethylene or other volatile compounds in addition to Myc-LCOs (Figure 2), and this might for example explain SYM pathway-independent lateral root induction in rice, while in nodulating legumes common SYM-mediated lateral root induction might be epistatic to auxin signaling.

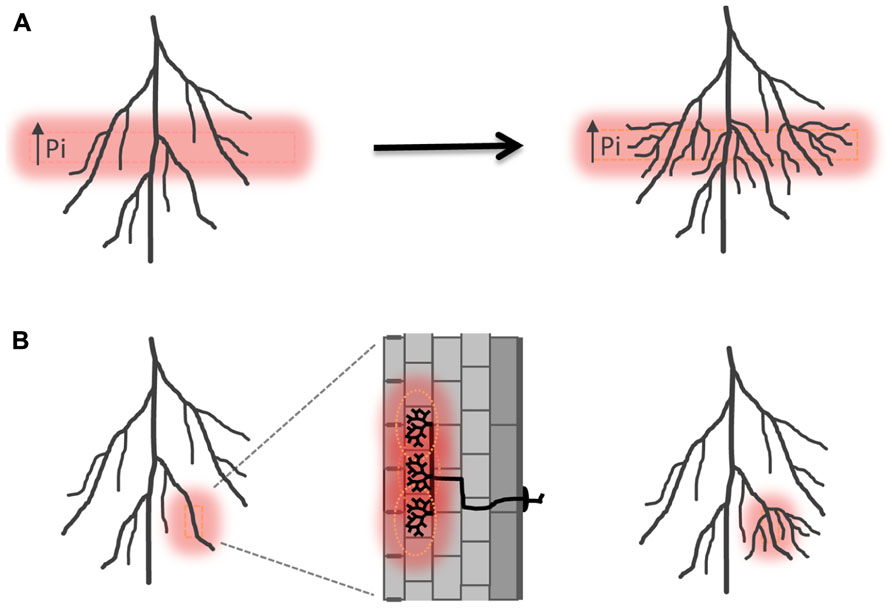

Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization preceding alterations in root system architecture has also been observed, e.g., in Allium porrum and Prunus cerasifera (Berta et al., 1990, 1995). Enhancement of lateral root formation after colonization has been related to nutritional effects. AM fungi deliver phosphate and nitrogen directly into the root cortex where the minerals are taken up by specific plant ion transporters localized in the peri-arbuscular membrane, a plant-derived membrane domain that surrounds the arbuscule branches (Harrison et al., 2002; Javot et al., 2007b; Kobae and Hata, 2010; Yang et al., 2012). The patchy distribution of AM colonization must lead to transient local increases of phosphate and/or nitrogen concentrations in the root, which may serve as a hallmark of symbiosis (Figure 3; Fitter, 2006). Plants can perceive localized differences in nutrient distribution also within the surrounding environment and respond with lateral root proliferation into phosphate or nitrogen-rich soil pockets (Figure 3; Drew, 1975; Linkohr et al., 2002). A nitrate transporter NRT1.1 has been identified in Arabidopsis thaliana, which acts as a nitrate transporter and sensor and triggers lateral root elongation into nitrate rich soil pockets (Remans et al., 2006). Besides nitrate it also facilitates auxin transport away from the lateral root meristem at low nitrogen conditions, leading to reduced lateral root outgrowth and elongation. In a patch of high nitrate concentration auxin transport by NRT1.1 is inhibited and auxin accumulates in lateral root tips leading to increased lateral root growth (Krouk et al., 2010). Thus NRT1.1 directly influences root system architecture via an orchestration of nitrate transport, -sensing as well as auxin transport. It will be highly interesting to determine if related mechanisms are at play in the regulation of root system architecture by mycorrhizal nutrient uptake. Mutants perturbed in mycorrhizal nutrient acquisition, e.g., defective in mycorrhiza-specific phosphate transporters such as Medicago PT4 or rice PT11 (Javot et al., 2007a; Yang et al., 2012), will provide a first means to study the impact of AM-mediate phosphate uptake on lateral root proliferation.

FIGURE 3. Induction of lateral root formation in response to locally high phosphate. (A) Schematic illustration of lateral root induction in high phosphate fertilized layers of the rhizosphere according to Drew (1975). (B) Hypothetical induction of lateral roots as a consequence of sensing a locally high concentration of phosphate within the tissue resulting from symbiotic phosphate uptake. Pi, inorganic phosphate.

In mycorrhizal roots, the symbiotic phosphate (possibly also nitrogen) uptake pathway dominates and involves suppression of the transporter genes involved in epidermal direct uptake (Smith et al., 2003; Smith and Smith, 2011; Yang and Paszkowski, 2011). It is a currently unexplored but attractive possibility that some transport proteins belonging to the direct epidermal nutrient uptake pathway are involved in nutrient sensing similar to NRT1.1 (Krouk et al., 2010). Downregulation of their expression during the switch from the direct to the mycorrhizal nutrient uptake pathway, might inhibit sensing of the nutrient status of the surrounding soil medium, and thus alter the root system architecture response to the local soil environment thereby enhancing the influence of mycorrhizal nutrient delivery on root system architecture.

Lateral root formation can be triggered by carbon supply in the growth medium, suggesting its dependence on sufficient carbon (Jain et al., 2007; MacGregor et al., 2008). There is evidence that in the AM symbiosis fungus-delivered phosphate is traded for plant-derived carbon (Kiers et al., 2011). However, the balance of this trade can depend on the plant–fungus species combination and competition among plants that are connected via the common hyphal network (Walder et al., 2012). As long as the carbon-cost imposed by the fungus is lower than the amount of sugar transported into a given colonized part of the root system, this redirection to colonized parts of the root system could perhaps provide a mechanism by which mycorrhiza-mediated mineral nutrient uptake promotes lateral root formation (Fitter, 2006; Yang and Paszkowski, 2011). A second mechanism for liberating carbon resources might be the putative reduction of secondary cell wall biosynthesis upon phosphate starvation release (Calderon-Vazquez et al., 2008). AM colonization has been reported to induce changes in the amount of phytohormones such as cytokinins, jasmonic acid (JA), certain auxins, abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene, salicylic acid (SA), strigolactones in roots (reviewed in Hause et al., 2007; Foo et al., 2013). These phytohormones are also involved in the regulation of root system architecture (Nibau et al., 2008; Fukaki and Tasaka, 2009; Koltai, 2011). It is currently unknown in how far the changes in phytohormone levels are related to AM-induced changes in root nutrient status evoked by mineral nutrient supply via the fungus or by an increase in root carbon sink strength. Nevertheless changes in phytohormone levels might contribute to root system remodeling in response to AM colonization either independently or as part of a nutrient signaling network.

Plant productivity strongly depends on an appropriately adapted root system architecture for the uptake of nutrients and water under adverse soil conditions. Thus modulation of the root system architecture in response to environmental conditions is considered an important target for genetic crop improvement (de Dorlodot et al., 2007). AM fungi represent an inherent component of natural and agricultural ecosystems and influence root system architecture prior and post-colonization. It is therefore of high interest to enhance knowledge about the molecular mechanisms that underpin these morphological modulations and to elucidate the cross-talk between the two regulatory “étappes” of root system remodeling.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Akiyama, K., Matsuzaki, K., and Hayashi, H. (2005). Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 435, 824–827. doi: 10.1038/nature03608

Amijee, F., Stribley, D., and Lane, P. (1993). The susceptibility of roots to infection by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in relation to age and phosphorus supply. New Phytol. 125, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03906.x

Berta, G., Fusconi, A., Trotta, A., and Scannerini, S. (1990). Morphogenetic modifications induced by the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus strain E3 in the root system of Allium porrum. New Phytol. 114, 207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00392.x

Berta, G., Trotta, A., Fusconi, A., Hooker, J., Munro, M., Atkinson, D., et al. (1995). Arbuscular mycorrhizal induced changes to plant growth and root system morphology in Prunus cerasifera. Tree Physiol. 15, 281–293. doi: 10.1093/treephys/15.5.281

Besserer, A., Puech-Pagés, V., Kiefer, P., Gomez-Roldan, V., Jauneau, A., Roy, S., et al. (2006). Strigolactones stimulate arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi by activating mitochondria. PLoS Biol. 4:e226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040226

Bidartondo, M., Read, D., Trappe, J., Merckx, V., Ligrone, R., and Duckett, J. (2012). The dawn of symbiosis between plants and fungi. Biol. Lett. 7, 574–577. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1203

Blee, K., and Anderson, A. (2002). Transcripts for genes encoding soluble acid invertase and sucrose synthase accumulate in root tip and cortical cells containing mycorrhizal arbuscules. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 197–211. doi: 10.1023/A:1016038010393

Bulgarelli, D., Rott, M., Schlaeppi, K., Ver Loren Van Thermaat, E., Ahmadinejad, N., Assenza, F., et al. (2012). Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature11336

Calderon-Vazquez, C., Ibarra-Laclette, E., Caballero-Perez, J., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2008). Transcript profiling of Zea mays roots reveals gene responses to phosphate deficiency at the plant- and species-specific levels. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2479–2497. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern115

de Dorlodot, S., Forster, B., Pagès, L., Price, A., Tuberosa, R., and Draye, X. (2007). Root system architecture: opportunities and constraints for genetic improvement of crops. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.012

Delaux, P.-M., Xie, X., Timme, R. E., Puech-Pages, V., Dunand, C., Lecompte, E., et al. (2012). Origin of strigolactones in the green lineage. New Phytol. 195, 857–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04209.x

Drew, M. (1975). Comparison of the effects of a localised supply of phosphate, nitrate, ammonium and potassium on the growth of the seminal root system, and the shoot, in barley. New Phytol. 75, 479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1975.tb01409.x

Felten, J., Kohler, A., Morin, E., Bhalerao, R. P., Palme, K., Martin, F., et al. (2009). The ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor stimulates lateral root formation in poplar and Arabidopsis through auxin transport and signaling. Plant Physiol. 151, 1991–2005. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147231

Felten, J., Legué, V., and Ditengou, F. A. (2010). Lateral root stimulation in the early interaction between Arabidopsis thaliana and the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor: is fungal auxin the trigger? Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 864–867. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147231.

Field, K. J., Cameron, D. D., Leake, J. R., Tille, S., Bidartondo, M. I., and Beerling, D. J. (2012). Contrasting arbuscular mycorrhizal responses of vascular and non-vascular plants to a simulated Palaeozoic CO(2) decline. Nat. Commun. 3, 835. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1831

Fitter, A. H. (2006). What is the link between carbon and phosphorus fluxes in arbuscular mycorrhizas? A null hypothesis for symbiotic function. New Phytol. 172, 3–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01861.x

Foo, E., Ross, J. J., Jones, T. W., and Reid, J. B. (2013). Plant hormones in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: an emerging role for gibberellins. Ann. Bot. 111, 769–779. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct041

Fukaki, H., and Tasaka, M. (2009). Hormone interactions during lateral root formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 69, 437–449. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9417-2

Gutjahr, C., Casieri, L., and Paszkowski, U. (2009a). Glomus intraradices induces changes in root system architecture of rice independently of common symbiosis signaling. New Phytol. 182, 829–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02839.x

Gutjahr, C., Novero, M., Guether, M., Montanari, O., Udvardi, M., and Bonfante, P. (2009b). Presymbiotic factors released by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita induce starch accumulation in Lotus japonicus roots. New Phytol. 183, 53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02871.x

Gutjahr, C., and Parniske, M. (2013). Cell and developmental biology of arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122413

Hanlon, M. T., and Coenen, C. (2010). Genetic evidence for auxin involvement in arbuscular mycorrhiza initiation. New Phytol. 189, 701–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03567.x

Harrison, M., Dewbre, G., and Liu, J. (2002). A phosphate transporter of Medicago truncatula involved in the acquisition of phosphate released by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Cell 14, 2413–2429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004861

Hata, S., Kobae, Y., and Banba, M. (2010). Interactions between plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 281, 1–48. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)81001-9

Hause, B., Mrosk, C., Isayenkov, S., and Strack, D. (2007). Jasmonates in arbuscular mycorrhizal interactions. Phytochemistry 68, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.09.025

Hepper, C. (1985). Influence of age of roots on the pattern of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal infection of leek and clover. New Phytol. 101, 685–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1985.tb02874.x

Hetrick, B. (1991). Mycorrhizas and root architecture. Experientia 47, 355–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01972077

Hochholdinger, F., and Feix, G. (1998). Early post-embryonic root formation is specifically affected in the maize mutant lrt1. Plant J. 16, 247–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00280.x

Hodge, A. (2009). Root decisions. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 628–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01891.x

Hodge, A., Berta, G., Doussan, C., Merchan, F., and Crespi, M. (2009). Plant root growth, architecture and function. Plant Soil 321, 153–187. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-9929-9

Hooker, J., Munro, M., and Atkinson, D. (1992). Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induced alterations in poplar root system morphology. Plant Soil 145, 207–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00010349

Humphreys, C. P., Franks, P. J., Rees, M., Bidartondo, M. I., Leake, J. R., and Beerling, D. J. (2010). Mutualistic mycorrhiza-like symbiosis in the most ancient group of land plants. Nat. Commun. 1, 103. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1105

Ivanchenko, M., Muday, G., and Dubrovsky, J. (2008). Ethylene-auxin interactions regulate lateral root initiation and emergence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 55, 335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03528.x

Jain, A., Poling, M. D., Karthikeyan, A. S., Blakeslee, J. J., Peer, W. A., Titapiwatanakun, B., et al. (2007). Differential effects of sucrose and auxin on localized phosphate deficiency-induced modulation of different traits of root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 144, 232–247. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092130

Javot, H., Varma Penmetsa, R., Terzaghi, N., Cook, D. R., and Harrison, M. J. (2007a). A Medicago truncatula phosphate transporter indispensable for the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1720–1725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608136104

Javot, H., Pumplin, N., and Harrison, M. (2007b). Phosphate in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: transport properties and regulatory roles. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 310–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01617.x

Jones, V. A., and Dolan, L. (2012). The evolution of root hairs and rhizoids. Ann. Bot. 110, 205–212. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs136

Karabaghli-Degron, C., Sotta, B., Bonnet, M., Gay, G., and Le Tacon, F. (1998). The auxin transport inhibitor 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) inhibits the stimulation of in vitro lateral root formation and the colonization of the tap-root cortex of Norway spruce (Picea abies) seedlings by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor. New Phytol. 140, 723–733. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00307.x

Kiers, E. T., Duhamel, M., Beesetty, Y., Mensah, J. A., Franken, O., Verbruggen, E., et al. (2011). Reciprocal rewards stabilize cooperation in the mycorrhizal symbiosis. Science 333, 880–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1208473

Kobae, Y., and Hata, S. (2010). Dynamics of periarbuscular membranes visualized with a fluorescent phosphate transporter in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots of rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 341–353. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq013

Koltai, H. (2011). Strigolactones are regulators of root development. New Phytol. 190, 545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03678.x

Kosma, D., Molina, I., Ohlrogge, J., and Pollard, M. (2012). Identification of an Arabidopsis fatty alcohol:caffeoyl-coenzyme A acyltransferase required for the synthesis of alkyl hydroxycinnamates in root waxes. Plant Physiol. 160, 237–248. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.201822

Kosuta, S., Chabaud, M., Lougnon, G., Gough, C., Dénarié, J., Barker, D., et al. (2003). A diffusible factor from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induces symbiosis-specific MtENOD11 expression in roots of Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 131, 952–962. doi: 10.1104/pp.011882.

Kretzschmar, T., Kohlen, W., Sasse, J., Borghi, L., Schlegel, M., Bachelier, J. B., et al. (2012). A petunia ABC protein controls strigolactone-dependent symbiotic signalling and branching. Nature 483, 341–344. doi: 10.1038/nature10873

Krouk, G., Lacombe, B., Bielach, A., Perrine-Walker, F., Malinska, K., Mounier, E., et al. (2010). Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev. Cell 18, 927–937. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.008

Ligrone, R., Carafa, A., Lumini, E., Bianciotto, V., Bonfante, P., and Duckett, J. (2007). Glomeromycotan associations in liverworts: a molecular, cellular and taxonomic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 94, 1756–1777. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.11.1756

Linkohr, B., Williamson, L., Fitter, A., and Leyser, H. (2002). Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system architecture of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 29, 751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01251.x

Lopez-Bucio, J., Cruz-Ramirez, A., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2003). The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 280–287. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00035-9

Lundberg, D., Lebeis, S., Herrera Paredes, S., Yourstone, S., Gehring, J., Malfatti, S., et al. (2012). Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 488, 86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11237

MacGregor, D. R., Deak, K. I., Ingram, P. A., and Malamy, J. E. (2008). Root system architecture in Arabidopsis grown in culture is regulated by sucrose uptake in the aerial tissues. Plant Cell 20, 2643–2660. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055475

Maillet, F., Poinsot, V., Andre, O., Puech-Pages, V., Haouy, A., Gueunier, M., et al. (2011). Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature 469, 58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09622

McCully, M., and Canny, M. (1988). Pathways and processes of water and nutrient uptake in roots. Plant Soil 111, 159–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02139932

Mukherjee, K., and Ane, J. (2011). Germinating spore exudates from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: molecular and developmental responses in plants and their regulation by ethylene. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 260–270. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-10-0146

Nibau, C., Gibbs, D., and Coates, J. (2008). Branching out in new directions: the control of root architecture by lateral root formation. New Phytol. 179, 595–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02472.x

Nishimura, R., Hayashi, M., Wu, G., Kouchi, H., Imaizumi-Anraku, H., Murakami, Y., et al. (2002). HAR1 mediates systemic regulation of symbiotic organ development. Nature 420, 426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature01231

Olah, B., Brière, C., Bécard, G., Dénarié, J., and Gough, C. (2005). Nod factors and a diffusible factor from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi stimulate lateral root formation in Medicago truncatula via the DMI1/DMI2 signalling pathway. Plant J. 44, 195–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02522.x

Osmont, K., Sibout, R., and Hardtke, C. (2007). Hidden branches: developments in root system architecture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.104006

Paszkowski, U., and Boller, T. (2002). The growth defect of lrt1, a maize mutant lacking lateral roots, can be complemented by symbiotic fungi or high phosphate nutrition. Planta 214, 584–590. doi: 10.1007/s004250100642

Rebouillat, J., Dievart, A., Verdeil, J., Escoute, J., Giese, G., Breitler, J., et al. (2009). Molecular genetics of rice root development. Rice 2, 15–34. doi: 10.1007/s12284-008-9016-5

Remans, T., Nacry, P., Pervent, M., Filleur, S., Diatloff, E., Mounier, E., et al. (2006). The Arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate rich patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 19206–19211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605275103

Rupp, L., Devries, H., and Mudge, K. (1989). Effect of aminocyclopropane carboxylic acid and aminoethoxyvinylglycine on ethylene production by ectomycorrhizal fungi. Can. J. Bot. 67, 483–485. doi: 10.1139/b89-068

Russell, J., and Bulman, S. (2005). The liverwort Marchantia foliacea forms a specialized symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the genus Glomus. New Phytol. 165, 567–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01251.x

Singh, S., and Parniske, M. (2012). Activation of calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CCaMK), the central regulator of plant root endosymbiosis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.04.002

Smith, S. E., and Smith, F. A. (2011). Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant nutrition and growth: new paradigms from cellular to ecosystem scales. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 227–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103846

Smith, S. E., Smith, F. A., and Jakobsen, I. (2003). Mycorrhizal fungi can dominate phosphate supply to plants irrespective of growth responses. Plant Physiol. 133, 16–20. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024380

Solaiman, M., Senoo, K., Kawaguchi, M., Imaizumi-Anraku, H., Akao, S., Tanaka, A., et al. (2000). Characterization of mycorrhizas formed by Glomus sp. on roots of hypernodulating mutants of Lotus japonicus. J. Plant Res. 113, 443–448. doi: 10.1007/PL00013953

Splivallo, R., Fischer, U., Göbel, C., Feussner, I., and Karlovsky, P. (2009). Truffles regulate plant root morphogenesis via the production of auxin and ethylene. Plant Physiol. 150, 2018–2029. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141325

Sukumar, P., Legué, V., Vayssièees, A., Martin, F., Tuskan, G. A., and Kalluri, U. C. (2013). Involvement of auxin pathways in modulating root architecture during beneficial plant–microorganism interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 909–919. doi: 10.1111/pce.12036

Venkateshwaran, M., Volkening, J. D., Sussman, M. R., and Ané, J.-M. (2013). Symbiosis and the social network of higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.11.007

Veresoglou, S. D., Menexes, G., and Rillig, M. C. (2012). Do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi affect the allometric partition of host plant biomass to shoots and roots? A meta-analysis of studies from 1990 to 2010. Mycorrhiza 22, 227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00572-011-0398-7

Volpe, V., Dell’Aglio, E., Giovannetti, M., Ruberti, C., Costa, A., Genre, A., et al. (2013). An AM-induced, MYB-family gene of Lotus japonicus (LjMAMI) affects root growth in an AM-independent manner. Plant J. 73, 442–455. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12045

Walder, F., Niemann, H., Natarajan, M., Lehmann, M. F., Boller, T., and Wiemken, A. (2012). Mycorrhizal networks: common goods of plants shared under unequal terms of trade. Plant Physiol. 159, 789–797. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195727

Wang, E., Schornack, S., Marsh, J., Gobbato, E., Schwessinger, B., Eastmond, P., et al. (2012). A common signaling process that promotes mycorrhizal and oomycete colonization of plants. Curr. Biol. 22, 2242–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.043

Wang, X., Pan, Q., Chen, F., Yan, X., and Liao, H. (2011). Effects of co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia on soybean growth as related to root architecture and availability of N and P. Mycorrhiza 21, 173–181. doi: 10.1007/s00572-010-0319-1

Wopereis, J., Pajuelo, E., Dazzo, F., Jiang, Q., Gresshoff, P., De Brujin, F., et al. (2000). Short root mutant of Lotus japonicus with a dramatically altered symbiotic phenotype. Plant J. 23, 97–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00799.x

Yang, S.-Y., Grønlund, M., Jakobsen, I., Grotemeyer, M. S., Rentsch, D., Miyao, A., et al. (2012). Nonredundant regulation of rice arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis by two members of the PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 gene family. Plant Cell 24, 4236–4251. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104901

Yang, S.-Y., and Paszkowski, U. (2011). Phosphate import at the arbuscule: just a nutrient? Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 1296–1299. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-11-0151

Yano, K., Yamauchi, A., and Kono, Y. (1996). Localized alteration in lateral root development in roots colonized by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Mycorrhiza 6, 409–415. doi: 10.1007/s005720050140

Keywords: arbuscular mycorrhiza, root system architecture, lateral root, plant nutrition, symbiosis, Glomeromycota

Citation: Gutjahr C and Paszkowski U (2013) Multiple control levels of root system remodeling in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 4:204. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00204

Received: 03 March 2013; Paper pending published: 20 March 2013;

Accepted: 31 May 2013; Published online: 18 June 2013.

Edited by:

Corné M. J. Pieterse, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Didier Reinhardt, University of Fribourg, SwitzerlandCopyright: © 2013 Gutjahr and Paszkowski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Caroline Gutjahr, Institute of Genetics, University of Munich, Biocenter Martinsried, 82152 Martinsried, Germany e-mail:Y2Fyb2xpbmUuZ3V0amFockBsbXUuZGU=; Uta Paszkowski, Department of Plant Sciences, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EA, UK e-mail:dXAyMjBAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.