95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol. , 29 June 2022

Sec. Invertebrate Physiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.938621

This article is part of the Research Topic Abiotic Stress and Physiological Adaptive Strategies of Insects View all 11 articles

The gene-drive system can ensure that desirable traits are transmitted to the progeny more than the normal Mendelian segregation. The clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) mediated gene-drive system has been demonstrated in dipteran insect species, including Drosophila and Anopheles, not yet in other insect species. Here, we have developed a single CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-drive construct for Plutella xylostella, a highly-destructive lepidopteran pest of cruciferous crops. The gene-drive construct was developed containing a Cas9 gene, a marker gene (EGFP) and a gRNA sequence targeting the phenotypic marker gene (Pxyellow) and site-specifically inserted into the P. xylostella genome. This homing-based gene-drive copied ∼12 kb of a fragment containing Cas9 gene, gRNA, and EGFP gene along with their promoters to the target site. Overall, 6.67%–12.59% gene-drive efficiency due to homology-directed repair (HDR), and 80.93%–86.77% resistant-allele formation due to non-homologous-end joining (NHEJ) were observed. Furthermore, the transgenic progeny derived from male parents showed a higher gene-drive efficiency compared with transgenic progeny derived from female parents. This study demonstrates the feasibility of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-drive construct in P. xylostella that inherits the desired traits to the progeny. The finding of this study provides a foundation to develop an effective CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-drive system for pest control.

During the Mendelian segregation, alleles generally have an equal chance (50:50) of being transmitted to progeny. Gene drives are selfish genetic elements that promote the spread of desirable traits across the populations by assuring that they are more often inherited than the Mendelian segregation (Akbari et al., 2015; Kandul et al., 2020). There are many examples of selfish genetic elements, either naturally occurring or synthetic, that can bypass the Mendelian segregation (Werren et al., 1988; Werren, 2011). The meiotic drive, sex-ratio distortion, and replicative transposition are typical examples of naturally occurring gene-drive elements (Ågren, 2016). The synthetic Medea drive system (Chen et al., 2007; Akbari et al., 2014), engineered underdominance systems (Buchman et al., 2018), and homing endonuclease gene-drive (HEGD) (Marshall and Hay, 2012; Esvelt et al., 2014; Gantz and Bier, 2015; Gantz et al., 2015; Champer et al., 2016) are included in synthetic gene-drive systems. The development of HEGD is accelerated by discovering the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Jinek et al., 2012; Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013).

Theoretical and practical use of CRISPR/Cas9 systems as a HEGD to change the genotype of insect species has been demonstrated (Esvelt et al., 2014; Unckless et al., 2015), which can potentially transmit the desired phenotype into a wild-type population of target species (Deredec et al., 2008; Unckless et al., 2017). In the CRISPR/Cas9-based gene drive (CCGD), the CRISPR/Cas9 construct contains the coding sequence of Cas9 endonuclease and a 20-bp gRNA targeting the specific site of the host genome. RNA-guided Cas9 causes a break of double-stranded DNA in the wild-type allele, which is repaired through either HDR or NHEJ (Karaminejadranjbar et al., 2018). The HDR-mediated repair drives the desired components into the next generation, while NHEJ mediated repair leads to the formation of resistant allele without transferring the desirable traits into the next generation (Champer et al., 2017; Champer et al., 2018). The consequences of resistant alleles depend on several factors, including the fitness cost associated with the drive and the type of gene-drive approach.

The CCGD system has been successfully developed in different organisms including bacteria (Valderrama et al., 2019), yeast (Dicarlo et al., 2015; Roggenkamp et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2018), mammals (Grunwald et al., 2019), and insects (Gantz and Bier, 2015; Gantz et al., 2015; Champer et al., 2017; Karaminejadranjbar et al., 2018; Kyrou et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). These studies show extremely-variable gene-drive efficiency, close to 100% in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 19%–62% in Drosophila melanogaster and 87%–99% in Anopheles. The variability in gene-drive efficiency depends on the timing and level of Cas9 expression, organism-specific factors, and the genomic targets (Champer et al., 2019). The CCGD has recently been used to control the pest population through a population-modification and population-suppression drives. In a population-modification drive, the release of transgenic mosquitoes in which the CCGD contains effector genes inhibiting the mosquito pathogen transmission results in the replacement of disease-sensitive mosquitoes with disease-resistant mosquitoes, which decreases the pathogen transmission (Buchman et al., 2018; Buchman et al., 2020). In the population-suppression drive, the homing-based gene-drive is developed to target the conserved sex-specific genes (Kyrou et al., 2018). Given these characteristics, both alteration and suppression drives can be used to control the pest population.

The germline-specific promoters and phenotypic marker genes play a significant role in the development of CCGD. The germline-specific promoters, including nanos promoter and vasa promoter to drive germline-specific Cas9 expression, have shown great potential to develop the CCGD in insects (Gantz and Bier, 2015; Gantz et al., 2015; Champer et al., 2017; Karaminejadranjbar et al., 2018; Kyrou et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Similarly, the phenotypic marker genes such as yellow and white are used as the target sites to assess and minimize the fitness cost caused by the CCGD. Furthermore, the phenotypic genes also provide an easy way to screen the progeny with resistant alleles through NHEJ (Gantz and Bier, 2015; Gantz et al., 2015; Champer et al., 2017; Champer et al., 2018). Therefore, we selected PxnanosO promoter to drive Cas9 and yellow gene as the target site for CCGD.

The diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella) is a globally-distributed lepidopteran pest that mainly attacks cruciferous crops and has developed resistance to all classes of insecticides, making it difficult to control (Furlong et al., 2013). Genetic-based approaches, especially CCGD for population suppression and modification, have only been developed in dipteran insect species (Gantz and Bier, 2015; Gantz et al., 2015; Champer et al., 2017; Karaminejadranjbar et al., 2018; Kyrou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020), not yet in other insect species. Previously, a CRISPR/Cas9-based split drive system has been successfully developed in Plutella xylostella. However, this split drive system failed to produce homing-based progeny (Xu et al., 2022). No homing-based progeny in the split-drive system might be because the two different transgenic lines (gRNA line and Cas9 line) cross each other. Keeping in view of these results, we developed a single CCGD construct for the first time in P. xylostella and evaluated its efficiency. The results provide a foundation for developing a CCGD system for population suppression or modification of P. xylostella.

The insecticide-susceptible strain Geneva 88 (G88) of P. xylostella used in this study was obtained from Cornell University in 2016 and subsequently established as a colony at the Institute of Applied Ecology, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. This strain was reared using a prepared artificial diet at 35%–50% RH, 16 h: 8 h (L:D) photoperiod, and 25 C in the growth chamber. After the larvae developed into pupae, the pupae were collected and transferred into the box for eclosion and mating. The adults were kept at 25 C and 80% RH and fed with 10% honey solution.

The genomic DNA of fourth instar larvae of P. xylostella was extracted using the MEGA Bio-Tek Tissue DNA kit (Omega, Norcross, United States), followed by purification after RNase treatment. The sequence of the candidate Pxyellow gene was obtained from P. xylostella genomic database (http://iae.fafu.edu.cn/DBM/index.php). The specific primers for PCR amplification were designed by using the NCBI database’s primer tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). The 2.3-kb fragment of the Pxyellow gene, including the gRNA target site, was PCR amplified with designed primer Yts-F and Yts-R (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction was prepared by using the Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and carried out with the following conditions of 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 10 s, 62 C for 20 s, 72 C for 2 min; then 72 C for 5 min; and 4 C forever. The PCR amplified products were purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States) following its protocol. The purified PCR product was sub-cloned into the PJET1.2 blunt-end vector (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and confirmed through Sanger sequencing.

The DNA fragment at exon 3 of Pxyellow gene was selected as the target site of gRNA based on the 5′-GG-(N)18-NGG-3′ principle (Hwang et al., 2013) by using the CRISPR gRNA Design tool-ATUM (https://www.atum.bio/eCommerce/cas9/input). The GG bases were added at the 5′ end of the gRNA target site to ensure the in vitro transcription stability by T7 RNA polymerase. A pair of long oligonucleotides were used to produce a DNA template of sgRNA for in vitro transcription (Bassett et al., 2013). The sgRNA-F oligonucleotide contained a T7 RNA polymerase binding site and the sgRNA target site, and the sgRNA-R oligonucleotide contained gRNA scaffold and overlap region of forward primer (Supplementary Table S1). PCR reaction was carried out by using the PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (TaKara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China) at the following conditions: 98 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 98 C for 10 s, 55 C for 20 s, 72 C for 30 s; then 72 C for 5 min and 4 C forever. This PCR product was purified with the Omega universal DNA Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States) by following its protocol. The purified PCR product was used for in vitro transcription of sgRNA with the HiScribe T7 Quick High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) by following its protocol.

Firstly, we obtained the germline-specific nanos gene sequence of Bombyx mori (NP_001093314) (Xu et al., 2019) from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and blasted it against the P. xylostella genomic database (http://iae.fafu.edu.cn/DBM/index.php) (You et al., 2013). The highly-similar gene PxnanosO (gene id: Px008918) was identified and selected. The PxnanosO promoter (PxnanosP) was amplified by using Nanos-F and Nanos-R primers (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction was prepared by using the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) and carried out with the following PCR conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 60 C for 20 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min; and then 4 C forever. This amplified PCR product was further purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The purified PCR product was sub-cloned into the PJET1.2 blunt-end vector (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and confirmed through sequencing. After sequence confirmation, we amplified PxnanosP from the PJET1.2 blunt-end vector with the same primers and conditions mentioned above.

The 4-kb Cas9 fragment was amplified from the plasmid PTD-T7-Cas9 (Huang et al., 2016) by using a pair of primers of Cas9-F and Cas9-R (SI, Supplementary Table S1) with the overlapping region of PxnanosP and SV40 PolyA tail. The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 58 C for 15 s, 72 C for 3 min; 72 C for 10 min; and then 4 C forever. The 4-kb amplified Cas9 product was further purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States).

The 250-bp Sv40 PolyA tail fragment was amplified from the GPXL-BacII-IE1-EGFP-SV40 vector (Asad et al., 2020) by using primers of Sv40-F and Sv40-R (Supplementary Table S1) with the overlapping region of Cas9 fragment and PJET1.2 vector. The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 58 C for 15 s, 72 C for 3 min; 72 C for 10 min; and then 4 C forever. The PCR amplified product of 250-bp Sv40 PolyA tail was further purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit.

These three fragments were assembled and cloned into the PJET1.2 blunt-end vector by using the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, #E5510) by following its protocol to obtain the PJET-Cas9 vector (Supplementary Figure S1).

All oligonucleotides containing overlapping regions for assembling fragments into vectors were designed by using the NEB Builder Assembling Tool of New England Bio Lab (http://nebuilder.neb.com/). The vector and insert fragment concentrations were calculated by using the New England Bio Lab tool NEBio Calculator (https://nebiocalculator.neb.com/#!/ligation). The mixture concentrations of all digestion reactions were calculated by using the New England Bio Lab tool, NEB Cloner (http://nebcloner.neb.com/#!/).

The Hr5IE1-EGFP-Sv40 fragment was amplified from the previously constructed vector GPXL-BacII-IE1-EGFP-SV40 (Asad et al., 2020). Two oligonucleotides (IE1-F and IE1-R) were used to amplify the Hr5IE1-EGFP fragment (Supplementary Table S1), which contains an overlapping region for insertion of this fragment at AbsⅠ cutting site of PJET-Cas9 vector (Supplementary Figure S1). The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, 58 C for 30 s, 72 C for 2 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. The amplified product of the Hr5IE1-EGFP-Sv40 fragment was further purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The PJET-Cas9 vector was linearized with the digestion of AbsⅠ (SibEnzyme, Russia). This digested product was purified by using the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). These two purified fragments (Hr5IE1-EGFP-Sv40 fragment and linearized PJET-Cas9 vector) were assembled with the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) by following the instruction of the manufacturer to obtain the PJET-Cas9-EGFP vector (Supplementary Figure S2). The insertion of Hr5IE1-EGFP-Sv40 fragment into the PJET-Cas9 vector was confirmed through colony PCR. The plasmid of positive clones was extracted with the Omega Mini Plasmid Extraction Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States) by following its protocol. The extracted plasmids of PJET-Cas9-EGFP vector were further used in double digestion with HF NotI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) and HF AgeI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States).

The PxU6 promoter was amplified from the previously-used U6:sgRNA expression vector (Huang et al., 2017). To link the gRNA sequence with U6, 20-bp gRNA and a sequence of terminal signals for the PxU6 gene were added to the reverse primer U6-R (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction mixture was prepared with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) by using two designed primers (U6-F and U6-R). The PCR reaction was carried out with following conditions: 95 C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, 61 C for 30 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. Another PCR reaction was performed with two oligonucleotides (gRNA-F and gRNA-R) containing the overlapping sequence for insertion of this fragment to the PJET-Cas9-EGEP vector. The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the same conditions used to amplify PxU6 promoter. This amplified product was further purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The PJET-Cas9-EGFP vector was digested with AgeI (New England Biolabs). The digested product was purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The two fragments (PJET-Cas9-EGFP vector and PxU6-gRNA) were assembled with the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, #E5510) by following the manufacturer’s instruction to obtain the PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA vector (Supplementary Figure S3). The plasmid of positive clones was extracted with the Omega Mini Plasmid Extraction Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The extracted plasmids were further used in double digestion with SpeI and AgeI enzymes (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States).

The 1-kb left and right regions from the gRNA target site of Pxyellow gene were selected as homologous arms. These two homologous arms were PCR amplified from the cloned Pxyellow gene with a pair of primers (LH-F & LH-R, RH-F & RH-R). The PCR reactions were carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 61 and 58 C for 30 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. These two amplified products were purified by gel electrophoresis and separately ligated into the PJET1.2 blunt vector. The ligated vector was confirmed through Sanger sequencing.

The left homologous arm (LHA) was PCR amplified by using the cloned fragment with two oligonucleotides (LHA-F and LHA-R) containing overlapping regions for assembling with the PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA vector (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 58 C for 30 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. The PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA vector was digested with SpeI and then purified with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The digested vector PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA and amplified left homologous arm were assembled with the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, #E5510). The insertion of LHA into PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA was confirmed through colony PCR. The plasmid of positive clones was extracted with the Omega Mini Plasmid Extraction Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States)

The confirmed vector containing LHA was further digested with the AgeI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) followed by purification with the Omega Gel Purification Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The right homologous arm (RHA) was PCR amplified by using the cloned fragment with two oligonucleotides (RHA-F and RHA-R) containing overlapping regions for assembling with the digested vector (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 60 C for 15 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. The right homologous arm and digested vector were again assembled with the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, #E5510) to obtain the PJET-Ca9-EGFP-gRNA-LRH vector (SI Supplementary Figure S4). The insertion of RHA was confirmed through colony PCR. The final gene-drive construct was named LHA-Ca9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA. The plasmid of positive clones was extracted with the Omega Mini Plasmid Extraction kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). The extracted plasmids were digested with HF NotI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) and HF AgeⅠ (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, United States) to confirm the insertion of LHA and RHA fragments into the PJET-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA vector.

The putative sequence of Pxku70 gene was obtained by blasting the X-ray repair protein 5-like mRNA (LOC101736121) sequence of Bombyx mori in the DBM genomic database (http://iae.fafu.edu.cn/DBM/index.php). The primers (Ku70-F and Ku70-R) were designed to amplify 610-bp fragment based on the obtained sequence (Supplementary Table S1). PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) at the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 28 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 60 C for 15 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. Furthermore, a pair of primers of T7Ku70-F and T7Ku70-R were designed to contain a T7 promoter in both primers (Supplementary Table S1). The PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) by using the previously-amplified product as the template at the same conditions explained above. The amplified product was used as the template for dsRNA synthesis with the T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi Kit (Promega) by following its protocol.

The injection mixture was prepared by mixing Cas9-N-NLS Nuclease (GenScript, United States), gRNA targeting Pxyellow, dsRNA targeting Pxku70, LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA vector with the injection buffer as previously described (Asad et al., 2020). The parafilm sheets of 12 cm2 coated with the cabbage leave extract were used to collect eggs, and the sheets were replaced every 30 min by new ones during the oviposition of female adults. The injections were performed within 1 h after oviposition by using the Olympus SZX16 microinjection system (Olympus, Japan). The injected embryos were placed in the hatching chamber at 25 ± 1 C, 60 ± 10% RH.

The hatched larvae from the injected eggs were maintained on the freshly-prepared diet. The G0 females and males were separated and outcrossed with wild-type adults of 1 G0 female with 2 wild-type males and 1 G0 male with 2 wild-type females. However, An equal number of transgenic and wild-type individuals (one transgenic cross with one wild-type individual) were used for the subsequent crosses of F2, F3, and F4 generations. The larval progeny of F1, F2, F3, and F4 were screened by the EGFP fluorescence under the fluorescent microscope equipped with an EGFP filter and stereoscope. The homozygous larvae exhibited a strong EGFP signal, and the heterozygous larvae showed a patchy EGFP signal (Chen et al., 2021).

The genomic DNA was extracted from adults of F1 generation after oviposition with the Omega Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Omega, Norcross, United States). A pair of primers (gTS-F and gTS-R) were used to amplify the gRNA target site (Supplementary Table S1). The amplified products were confirmed through Sanger sequencing. The insertion of the gene-drive cassette into the Pxyellow gene was confirmed through PCR by using the designed primers (Supplementary Table S1). PCR reaction was carried out with the Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China) and the extracted DNA of F1 EGFP-positive adults at the conditions: 95 C for 3 min; 32 cycles of 95 C for 15 s, 60 C for 15 s, 72 C for 1 min; 72 C for 5 min and then 4 C forever. The amplified products were confirmed through Sanger sequencing.

The Chi-square (χ2) analysis was performed by using the Graphpad 8.02 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, San Diego, CA, United States) to determine the significant difference between the gene-drive efficiency in different generations of transgenic P. xylostella and EGFP+ progeny derived from different parents at p < 0.05. The Z test was used to compare the NHEJ and HDR mutation rates in the progeny of different crosses at p < 0.05.

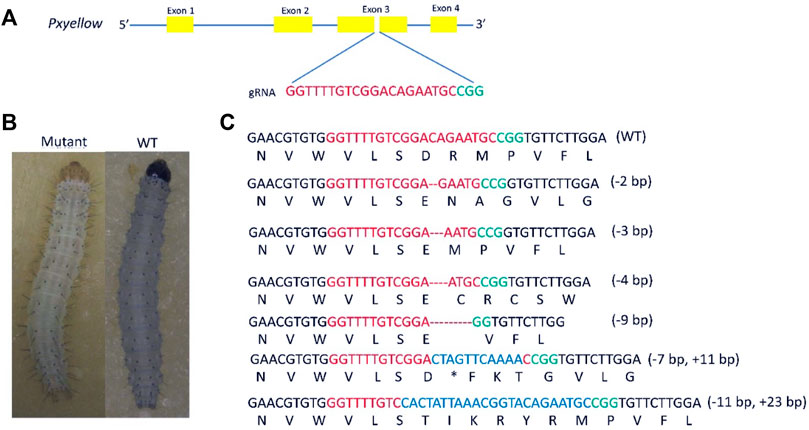

The Pxyellow gene (gene ID: Px007091) is body pigmentation gene and disruption of Pxyellow gene only leads to a change in body color (Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, the Pxyellow gene is a suitable target site for screening the mutant progeny in the CRISPR/Cas9-based gene-drive system in P. xylostella. The Pxyellow gene is located at scaffold 25, containing four exons and five introns. The sgRNA was designed and synthesized to target the Exon 3 of Pxyellow (Figure 1A). A total of 150 preblastoderm embryos were injected with the mixture of sgRNA and Cas9 protein, and 90 hatched (the hatching rate of 60%). The 60 G0 larvae showed yellow head compared with wild-type larvae, which was clearly observed at second and third instar larvae (Figure 1B), making the mutation rate 40% (60/150) in G0 individuals. The 439-bp DNA fragment flanking the target site was amplified from these mosaic G0 adults and sequenced.

FIGURE 1. Knockout of Pxyellow gene at the target site. (A), the schematic representation of Pxyellow gene. The orange boxes indicate the exon of Pxyellow gene, and blue lines indicate the introns. (B), phenotypic difference between Pxyellow mutant and wild type. (C), types of deletions and insertions at the target site. Red base pairs indicate the gRNA sequence and green indicate the PAM, sequence; the deletions are highlighted with dashes (--), and the inserted base pairs are highlighted with blue colors.

Out of these 60 G0 mutant individuals, 43 individuals showed indels at the target site (Supplementary Appendix Table S1). Four types of deletions (-2 bp, -4 bp. -3 bp and -9 bp) and two types of insertions (+11 bp and +14 bp) were observed in 43 individuals (Figure 1C).

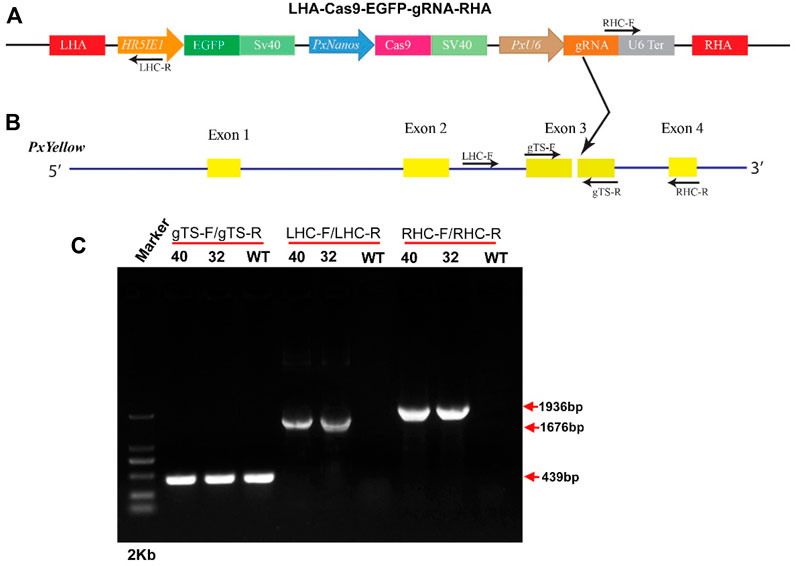

The 1.8-kb upstream sequence of the PxnanosO gene was cloned and used as a putative promoter. The immediate-early-stage 1 promoter with an enhancer 5 (HR5IE1) was used to drive the EGFP marker gene. This promoter has been successfully used as a transformation marker in different insect species, including P. xylostella (Grossman et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2012). The PxU6:3 promoter has been used to drive gRNA in P. xylostella (Huang et al., 2017). The LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA construct contained a Cas9 gene driven by Pxnanos promoter, an EGFP marker gene-driven by HR5IE1 promoter and a gRNA sequence (targeting the phenotypic marker gene Pxyellow) driven by PxU6 promoter (Figure 2A). The details about the construction and verification of LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA construct are listed in Supplementary information (Supplementary Figure S5). The detailed sequences of Pxnanos promoter, HR5IE1 promoter, EGFP marker gene, Cas9, PxU6 promoter gRNA, left and right homologous arms are also listed in (Supplementary Appendix Table S2).

FIGURE 2. Site-specific insertion of gene-drive construct. (A), schematic representation of gene-drive cassette (LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA). (B), schematic representation of Pxyellow gene. The small arrow with the label represents the position, orientation and name of primers used to confirm the integration of the gene-drive cassette into the Pxyellow target site. The red boxes represent the left homologous arm (LHA) and right homologous arm (RHA). The other components of plasmid LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA have been highlighted and labeled with different colors. The yellow boxes represent the 4 exons of Pxyellow gene. The dark gray lines represent the introns of Pxyellow gene. The black arrow represents the gRNA target site in Pxyellow locus. (C), Verification of the site-specific insertion of LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA construct by PCR.

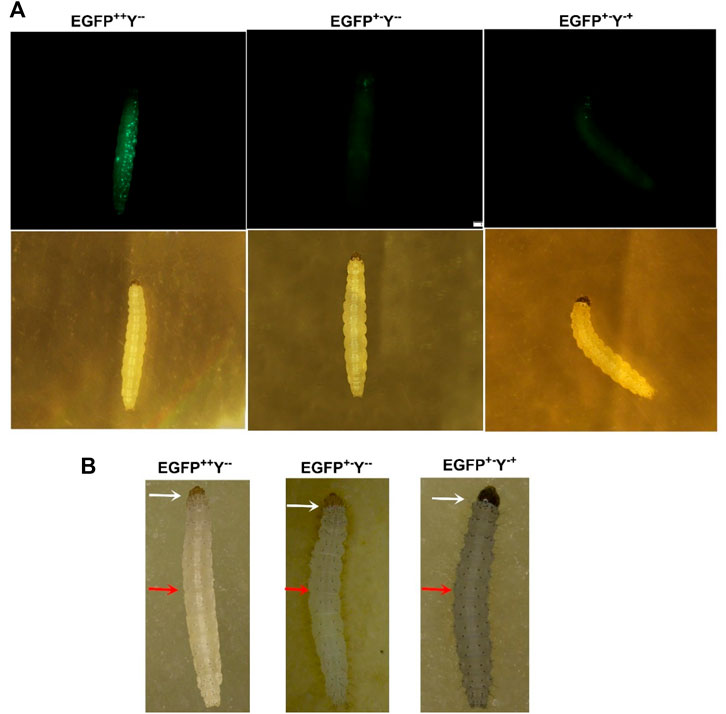

The transgenic P. xylostella was developed by injecting the mixture of plasmid LHA-Cas9-EGFP-gRNA-RHA, Cas9 protein, sgRNA, and Pxku70 dsRNA into embryos to insert the gene-drive cassette Cas9-EGFP-gRNA into the target site of Pxyellow (Figure 2B). A total of 5930 P. xylostella embryos were injected in five attempts, of which the mean G0 survival rate was 22.02% (Supplementary Table S2). The survived G0 male and female were individually outcrossed with wild-type to produce the F1 progeny. The integration of drive cassette in F1 was verified by the PCR products a 439-bp fragment amplified with primers gTS-F and gTS-R, a 1676-bp fragment amplified with primers LHC-F and LHC-R, and a 1936-bp fragment amplified with primers RHC-F and RHC-R (Figure 2C). The second and third instar larvae of the F1 generation were screened for green fluorescence (EGFP+) (Figure 3A) and abnormal yellow body and head pigmentation (Y−) (Figure 3B). One EGFP-positive female and one EGFP-positive male with yellow mutant phenotype were subsequently obtained from 28200 F1 individuals and named founder 32 and founder 40, respectively (Supplementary Table S3).

FIGURE 3. Larval phenotypes of transgenic P. xylostella harboring the gene-drive cassette. (A), larval images in the upper row taken in the presence of EGFP filter and larval images in the lower row taken with a bright-light filter. (B), larval images taken by a stereoscope. The white arrows indicate the head color, and the red arrows indicate the body color.

Furthermore, we scored three kinds of phenotypes with corresponding genotypes such as strong EGFP fluorescence and yellowish body (EGFP++Y−-), patchy EGFP fluorescence and yellowish body (EGFP+−Y--), and patchy EGFP fluorescence and wild-type body color (EGFP+−Y-+) due to non-mendelian segregation after crossing of homozygous EGFP++Y−-individuals with wild type (EGFP−-Y++) in different generations of both founders (Figure 3). According to the Mendelian segregation, all F1 progeny should be heterozygote with EGFP-positive and wild-type body color because yellow gene is recessive. The conversion of heterozygote to homozygote progeny indicates the homing of Cas9-EGFP-gRNA component to neighboring allele.

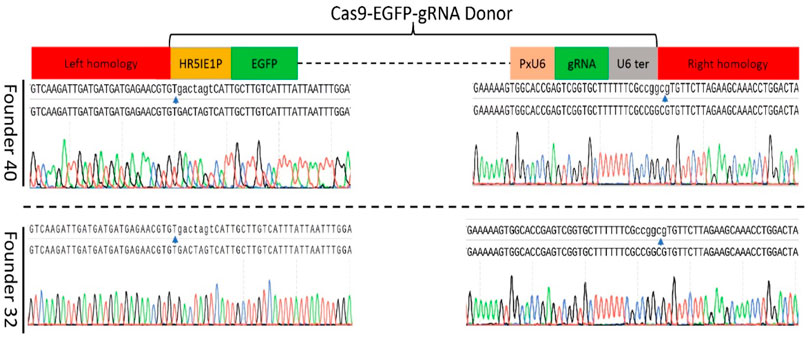

The target-specific insertion of the gene-drive cassette at Pxyellow locus was confirmed in both F1 founders through PCR amplification (Figure 2C). The sequencing of both diagnostic amplicons containing the left and right homologous regions and their adjacent sequences in the gene-drive cassette showed cassette insertion at the Pxyellow target site (Figure 4 and Supplementary Appendix Table S3).

FIGURE 4. Sequence confirmation of the precise insertion of the gene-drive construct into the Pxyellow locus. The PCR amplification and genomic DNA sequencing were performed to verify the precise insertion of gene-drive components at Pxyellow locus in two F1 founders (40 and 32). Sequence of 5′-end fragment amplified by LH-F and LH-R is presented at the left side, and sequence of 3′-end fragment amplified by RH-F and RH-R is presented at the right side in both founders. The blue arrows represent the junction between the Pxyellow coding sequence and gene-drive construct.

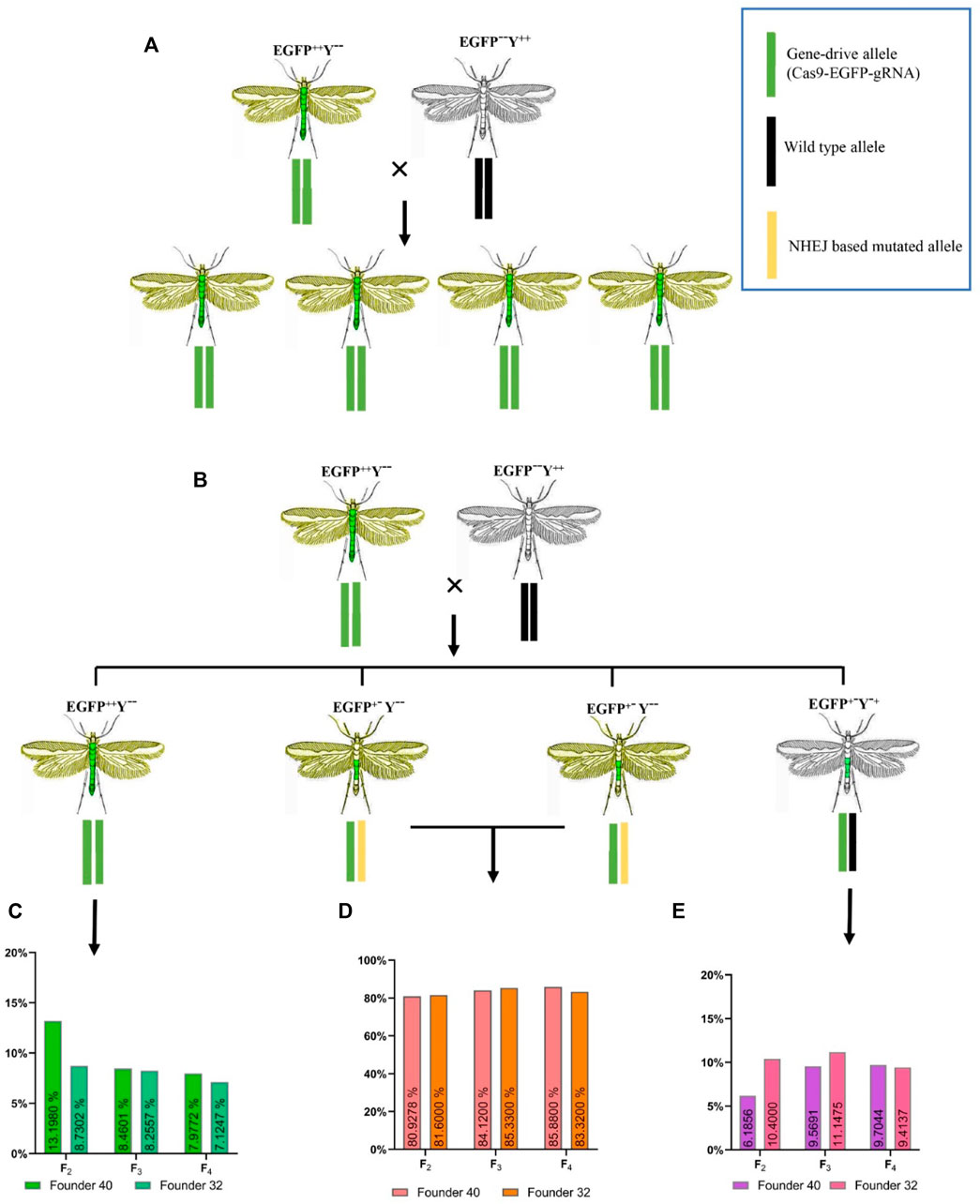

Under ideal homing endonuclease-based gene-drive conditions (100%), all progenies should show stable EGFP and yellowish phenotype (Figure 5A). Based on the above-mentioned genotypes, there were 13.19% individuals of EGFP++Y−-in F2 generation, 9.40% in F3 generation and 8.32% in F4 generation for founder 40. Similarly, for founder 32, there were only 8.25% individuals of EGFP++Y−-genotype in F2 generation, 8.91% in F3 generation and 7.82% in F4 (Figure 5B). These individuals of genotype EGFP++Y−-indicated the homing (gene-drive) of one inherited allele to neighboring wild-type allele through the HDR process. However, more than 85% of alleles were either mutated through the NHEJ process (Figure 5C) or uncut in F2, F3 and F4 generations from both founders (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5. Expected and obtained phenotypes with different genotypes. (A), expected genotypes and phenotypes for an ideal homing endonuclease-based gene-drive system; (B), obtained genotypes and phenotypes during this study; (C), the homing efficiency in different generations; (D), the resistant allele formation with one allele inherited and the second allele mutated without homing; (E), the resistant-allele formation with one allele inherited and the second allele uncut.

There was no difference in the homing efficiency among the different generations of both founders (founder 32, χ2 = 2.872, df = 2, p = 0.237; founder 40, χ2 = 0.232, df = 2, p = 0.891) or between the two founders (χ2 = 0.073, df = 1, p = 0.7870). These results indicated that all progeny derived from parent crosses contained the drive allele, from which only 7.82%–13.19% were converted into homozygous drive allele (EGFP++Y−-) due to HDR and the rest were converted into resistance allele (EGFP+−Y--, EGFP+−Y-+) due to NHEJ (Figure 5 C and D). This situation indicated that cleavage of the target site with Cas9 happened in somatic tissues rather than in the germline tissues, which caused the formation of resistance allele.

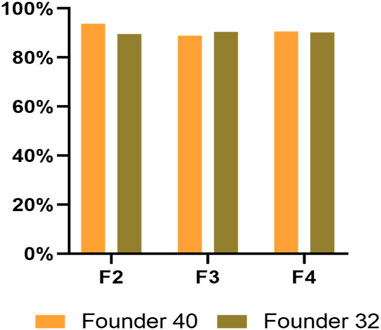

There was no difference in the Cas9/sgRNA cleavage efficiency of negibouring alleles between two founders (χ2 = 1.869, df = 1, p = 0.1715) or among different generations of both founders (founder 32, χ2 = 2.864, df = 2, p = 0.239; founder 40, χ2 = 3.473, df = 2, p = 0.176), which all showed the cleavage efficiency of above 88% in P. xylostella (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. The cleavage efficiency of Pxyellow target site in different generations from both founders.

Furthermore, the individuals with heterozygous EGFP+−Y--phenotype were randomly selected for genotype confirmation through PCR amplification. The PCR results showed the deletion of base pairs at the Pxyellow target site in heterozygote EGFP+−Y--mutants from both founders (Supplementary Figure S6). After cutting of genomic DNA by Cas9, EGFP+−Y--caused by NHEJ happened more frequently than EGFP++Y−-caused by HDR in F2 progeny (Z = -3.211, p = 0.001), in F3 progeny (Z = -2.521, p = 0.012) and in F4 progeny (Z = -2.521, p = 0.012).

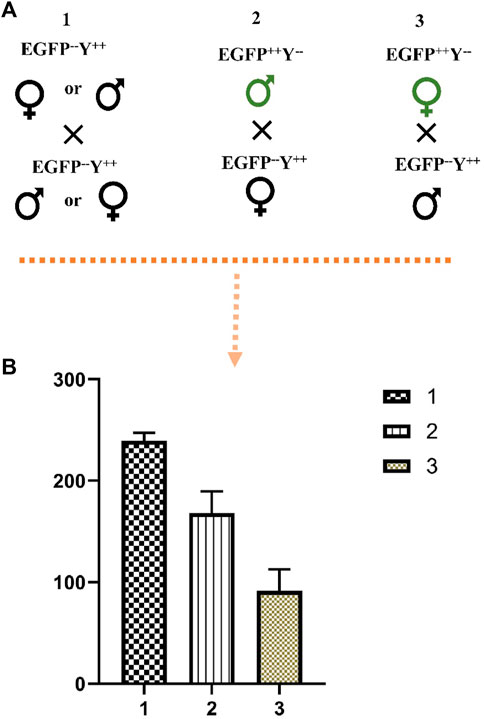

The cross between founder 40 (F1 EGFP++Y−-male) and wild-type female produced less progeny (125 adult/cross) than the cross between founder 32 (F1 EGFP++Y−-female) and wild-type male (194 adult/cross) (χ2 = 7.402, df = 1, p = 0.006) (Table 1).

For founder 40, crosses between F2 EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male produced less progeny (147.1 adult/cross) than crosses between F2 EGFP++Y−-male and wild-type female (240.28 adult/cross) (χ2 = 46.794, df = 1, p = 0.000); for founder 32, crosses between F2 EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male (196.6 adult/cross) produced less progeny than crosses between F2 EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male (215 adult/cross) (χ2 = 46.581, df = 1, p = 0.000) (Table 2.

For founder 40, crosses between F3 EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male produced less progeny (188.16 adult/cross) than crosses between F3 EGFP++Y−-male and wild-type female (257.4 adult/cross) (χ2 = 47.342, df = 1, p = 0.000); for founder 32, crosses between F3 EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male produced less progeny (182.5 adult/cross) than crosses between F3 EGFP++Y−-and wild-type female (264.7 adult/cross) (χ2 = 519.35, df = 1, p = 0.000) (Table 3).

The cross between wild-type male and female produced more progeny than the cross between EGFP++Y−-male and wild-type female (χ2 = 7.33, df = 1, p = 0.003); the cross between EGFP+Y− male produced more progeny than the cross between EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male (χ2 = 16.34, df = 1, p = 0.000) (Figure 7). Therefore, the above results indicated that knock-in of gene-drive cassette reduced the fecundity of females.

FIGURE 7. The effect of EGFP++Y−-parents on the number of progenies. (A), schematic representation of crosses, (B), the number of progenies produced from crosses of different parents; 1, cross between wild-type male and female; 2, cross between EGFP++Y−-male and wild-type female; 3, cross between EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male.

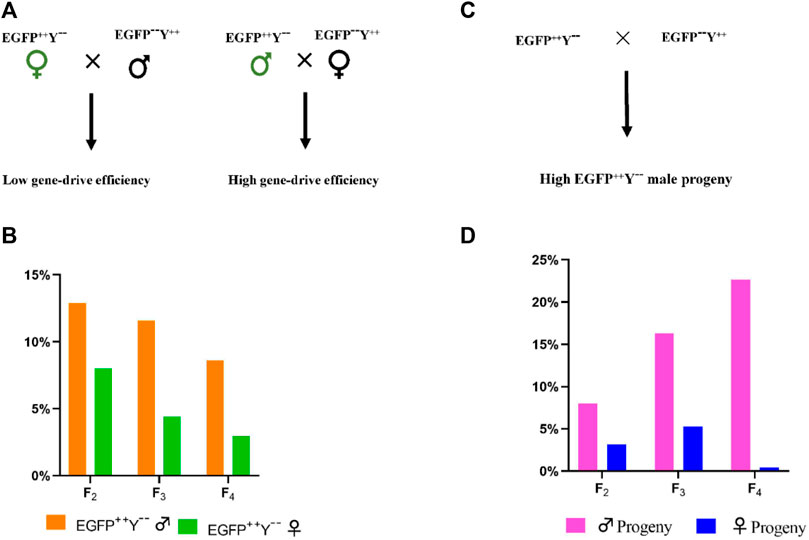

Crosses between EGFP++Y−-female and wild-type male produced less EGFP++Y−-progeny than crosses between EGFP++Y−-male and wild-type female (F2, χ2 = 7.994, df = 1, p = 0.004; F3, χ2 = 62.684, df = 1, p = 0.000; F4, χ2 = 104.791, df = 1, p = 0.000) (Figure 8A). Crosses between EGFP++Y−-and wild type produced less EGFP++Y−-females than EGFP++Y−-males (F2, χ2 = 7.641, df = 1, p = 0.005; F3, χ2 = 112.035, df = 1, p = 0.000; F4, χ2 = 939.138, df = 1, p = 0.000) (Figure 8B). Therefore, the gene-drive efficiency caused by parent males was much higher than that caused by parent females. The gene-drive efficiency was much higher in male progeny than in female progeny in P. xylostella.

FIGURE 8. The difference in gene-drive efficiency caused by the male and female parents. (A), schematic representation of EGFP++Y−-parents cross with wild-type parents, (B), the gene-drive percentage caused by EGFP++Y−-male and female parents; (C), representation of crosses, (D), percentage of male and female progeny with EGFP++Y−-genotype.

The Pxyellow gene was selected as the target site for the confirmation of phenotypic changes in P. xylostella. The CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of Pxyellow gene demonstrated the change of body and head capsule color from black to yellowish. The change in body and head capsule color was quite apparent in the second and third instar larvae. A similar kind of results are previously reported, in which the Pxyellow gene plays an essential role in body pigmentations in P. xylostella (Wang et al., 2020). To develop an effective gene-drive system to evaluate drive efficiency and fitness cost, it is an appropriate way to target endogenous phenotypic marker genes, which help in screening mutant progeny. A CCGD system has previously been developed in Drosophila melanogaster, in which phenotypic marker yellow and white genes are used as the target sites (Champer et al., 2017; Champer et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2019). Similarly, this system has been developed in mosquitos (Anopheles and Aedes), in which the white-eye phenotypic marker gene is used as the target site (Gantz et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020). The selection of the phenotypic marker gene provides an easy way to screen the mutant progeny.

The gene-drive cassette worked in lepidopteran pest, P. xylostella. The approximately 12-kb long construct could effectively create site-specific mutation. These results are consistent with the previous study conducted in An. gambiae, in which approximately 17-kb construct shows its feasibility to create site-specific cleavage (Gantz et al., 2015). Additionally, the overall cleavage efficiency of neighboring allele of 88.86–93.82%, gene-drive of 6.67%–12.59%, and resistant-allele formation of 80.93%–86.77% were observed. Surprisingly, the gene-drive efficiency was much lower than other insects. Certain factors might be involved in the low gene-drive efficiency, either gene-drive component or the target site, associated with the fitness cost. The differences in the gene-drive efficiency depend upon numerous factors, such as species-specific factors, variations in the Cas9 expression, and the genomic target site. The species-specific factor might contribute to the low gene-drive efficiency in P. xylostella because the enormous variations across the species were observed, such as close to 100% in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Dicarlo et al., 2015; Roggenkamp et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2018), 19%–62% in D. melanogaster (Champer et al., 2017; Champer et al., 2018; Karaminejadranjbar et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2019) and 87%–99% in An. gambiae (Gantz et al., 2015; Kyrou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020). Therefore, different species may have different gene-drive efficiencies.

The expression of Cas9 in somatic and germline tissues also plays a crucial role in gene-drive efficiency. In D. melanogaster, the germline-specific nanos and vasa promoters were used to drive Cas9 gene expression for the development of the CCGD system. The nanos promoter construct to drive Cas9 exhibits a high gene-drive efficiency and a low resistant-allele formation due to the low Cas9 expression in somatic tissues. In contrast, the construct containing vasa promoter to drive Cas9 exhibits a high resistant-allele formation and a low gene-drive efficiency due to the high Cas9 expression in somatic tissues (Champer et al., 2018). In An. stephensi, the vasa promoter used to drive the Cas9 expressions results in a high germline gene conversion through HDR-mediated repair (99%) (Gantz et al., 2015). Recently, the different germline-specific promoters of P. xylostella have been tested in the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated split-drive system. All these tested promoters show a high somatic cleavage with limited germline cleavage. However, no homing is observed in this CRISPR/Cas9 split drive (Xu et al., 2022). Therefore, the selection of germline-specific promoters to drive the Cas9 expression is critical. In our study, the PxnanosP showed a high frequency of resistant-allele formation rather than gene-drive in P. xylostella, which might be due to a high Cas9 expression driven by PxnanosP in somatic tissues.

Another factor that may contribute to the gene-drive efficiency is the genomic target site of gRNA. In D. melanogaster, the nanos promoter-based gene-drive construct targeting the two different genomic target sites, such as the white gene and cinnabar gene, exhibits different gene-drive efficiency (59% and 38%) (Champer et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2019). Similarly, the vasa promoter-based gene-drive construct targeting the two different genomic target sites, such as yellow gene and yellow gene promoter, showed 55% and 37% gene-drive efficiency, respectively (Champer et al., 2017). Hence, the different genomic target sites cause different gene-drive efficiencies. In our study, the yellow gene was targeted, which might contribute to a low gene-drive efficiency. Therefore, more targets should be identified and tested to achieve a high gene-drive efficiency.

The gene-drive efficiency caused by the parent male was much higher than that caused by parent female, and the gene-drive efficiency was much higher in male progeny than in female progeny in P. xylostella. Previous studies exhibit that the maternally-deposited Cas9 contributes to the development of resistant alleles in An. stephensi (Gantz et al., 2015). Similarly, in D. melanogaster, resistant-allele formation is due to the high maternal-deposition of Cas9 in eggs before fertilization or embryo development (Champer et al., 2017; Champer et al., 2018; Champer et al., 2019; Kandul et al., 2020). Therefore, the low gene-drive efficiency and high resistant-allele formation in progeny derived from transgenic females are due to the high level of maternally-deposited Cas9. The knock-in of gene-drive construct reduced the fecundity of transgenic females. The high Cas9 expression may have some side effects, reducing fecundity. Further studies are required to answer this question.

Toward the success of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene drive for pest control, it is essential to increase the gene-drive efficiency. The gene-drive efficiency is much lower in P. xylostella than in other insects. The problem of low gene-drive efficiency can be tackled with different approaches. The selection of suitable germline promoters can effectively drive Cas9 expression in germ cells and cause DSB followed by homing during gametogenesis (Hammond et al., 2016). Multiplex gRNAs targeting the different locus of a gene may increase the gene-drive efficiency (Champer et al., 2018). Suppression of NHEJ pathway genes may increase the rate of HDR (Zhu et al., 2015). As in B. mori, it has been described that the suppression of NHEJ-pathway genes, such as BmKu70 and BmKu80, increases the HDR-mediated repair (Zhu et al., 2015). Since the gene-drive efficiency is low, further studies are required to understand the mechanism of resistant-allele formation for increasing the gene-drive efficiency.

In general, our data demonstrated that the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-drive construct worked in P. xylostella through effectively copying the gene-drive components to the target site, and the NHEJ event happened more than the HDR. The progeny derived from mutant male parents showed a relatively-high gene-drive efficiency than those from mutant female parents. These results provided a foundation for further development of the CCGD system in P. xylostella, especially for the pest management program. Our results also provide a valuable information for future construction of highly improved and optimized CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-drive for genetic control of globally-distributed pest P. xylostella.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, MA, and GY; methodology, MA; formal analysis, MA, and DL; investigation, MA, DL, and JL, data curation, MA, DL, and JC writing—original draft preparation, MA; writing—review and editing, MA, DL, and GY; supervision, GY; funding acquisition, GY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (3172237), the Special Key Project of Fujian Province (2018NZ01010013); and “111” program (KRA16001A).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Authors are thankful to all lab members for their support to conduct the study.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.938621/full#supplementary-material

Ågren J. A. (2016). Selfish Genetic Elements and the Gene's-Eye View of Evolution. Curr. Zool. 62, 659–665. doi:10.1093/cz/zow102

Akbari O. S., Bellen H. J., Bier E., Bullock S. L., Burt A., Church G. M., et al. (2015). Safeguarding Gene Drive Experiments in the Laboratory. Science 349, 927–929. doi:10.1126/science.aac7932

Akbari O. S., Chen C.-H., Marshall J. M., Huang H., Antoshechkin I., Hay B. A. (2014). Novel Synthetic Medea Selfish Genetic Elements Drive Population Replacement in Drosophila; a Theoretical Exploration of Medea-dependent Population Suppression. ACS Synth. Biol. 3, 915–928. doi:10.1021/sb300079h

Asad M., Munir F., Xu X., Li M., Jiang Y., Chu L., et al. (2020). Functional Characterization of Thecis‐regulatory Region for the Vitellogenin Gene in Plutella xylostella. Insect Mol. Biol. 29, 137–147. doi:10.1111/imb.12632

Bassett A. R., Tibbit C., Ponting C. P., Liu J.-L. (2013). Highly Efficient Targeted Mutagenesis of Drosophila with the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Cell Rep. 4, 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.020

Buchman A. B., Ivy T., Marshall J. M., Akbari O. S., Hay B. A. (2018). Engineered Reciprocal Chromosome Translocations Drive High Threshold, Reversible Population Replacement in Drosophila. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 1359–1370. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00451

Buchman A., Gamez S., Li M., Antoshechkin I., Li H.-H., Wang H.-W., et al. (2020). Broad Dengue Neutralization in Mosquitoes Expressing an Engineered Antibody. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008103. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008103

Champer J., Chung J., Lee Y. L., Liu C., Yang E., Wen Z., et al. (2019). Molecular Safeguarding of CRISPR Gene Drive Experiments. eLife 8, e41439. doi:10.7554/eLife.41439

Champer J., Reeves R., Oh S. Y., Liu C., Liu J., Clark A. G., et al. (2017). Novel CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Drive Constructs Reveal Insights into Mechanisms of Resistance Allele Formation and Drive Efficiency in Genetically Diverse Populations. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006796–1006802. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006796

Champer J., Buchman A., Akbari O. S. (2016). Cheating Evolution: Engineering Gene Drives to Manipulate the Fate of Wild Populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 146–159. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.34

Champer J., Liu J., Oh S. Y., Reeves R., Luthra A., Oakes N., et al. (2018). Reducing Resistance Allele Formation in CRISPR Gene Drive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5522–5527. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720354115

Champer J., Zhao J., Champer S. E., Liu J., Messer P. W. (2020). Population Dynamics of Underdominance Gene Drive Systems in Continuous Space. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 779–792. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00452

Chen C.-H., Huang H., Ward C. M., Su J. T., Schaeffer L. V., Guo M., et al. (2007). A Synthetic Maternal-Effect Selfish Genetic Element Drives Population Replacement in Drosophila. Science 316, 597–600. doi:10.1126/science.1138595

Chen J., Luo J., Wang Y., Gurav A. S., Li M., Akbari O. S., et al. (2021). Suppression of Female Fertility in Aedes aegypti with a CRISPR-Targeted Male-Sterile Mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2105075118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2105075118

Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., et al. (2013). Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 339, 819–823. doi:10.1126/science.1231143

Deredec A., Burt A., Godfray H. C. J. (2008). The Population Genetics of Using Homing Endonuclease Genes in Vector and Pest Management. Genetics 179, 2013–2026. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.089037

Dicarlo J. E., Chavez A., Dietz S. L., Esvelt K. M., Church G. M. (2015). Safeguarding CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drives in Yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1250–1255. doi:10.1038/nbt.3412

Esvelt K. M., Smidler A. L., Catteruccia F., Church G. M. (2014). Emerging Technology: Concerning RNA-Guided Gene Drives for the Alteration of Wild Populations. eLife 3, e03401. doi:10.7554/eLife.03401

Furlong M. J., Wright D. J., Dosdall L. M. (2013). Diamondback Moth Ecology and Management: Problems, Progress, and Prospects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 517–541. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153605

Gantz V. M., Jasinskiene N., Tatarenkova O., Fazekas A., Macias V. M., Bier E., et al. (2015). Highly Efficient Cas9-Mediated Gene Drive for Population Modification of the Malaria Vector Mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, E6736–E6743. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521077112

Gantz V. M., Bier E. (2015). The Mutagenic Chain Reaction: a Method for Converting Heterozygous to Homozygous Mutations. Science 348, 442–444. doi:10.1126/science.aaa5945

Gong P., Epton M. J., Fu G., Scaife S., Hiscox A., Condon K. C., et al. (2005). A Dominant Lethal Genetic System for Autocidal Control of the Mediterranean Fruitfly. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 453–456. doi:10.1038/nbt1071

Grossman G. L., Rafferty C. S., Clayton J. R., Stevens T. K., Mukabayire O., Benedict M. Q. (2001). Germline Transformation of the Malaria Vector, Anopheles gambiae, with the piggyBac Transposable Element. Insect Mol. Biol. 10, 597–604. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1075.2001.00299.x

Grunwald H. A., Gantz V. M., Poplawski G., Xu X.-R. S., Bier E., Cooper K. L. (2019). Super-Mendelian Inheritance Mediated by CRISPR-Cas9 in the Female Mouse Germline. Nature 566, 105–109. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0875-2

Hammond A., Galizi R., Kyrou K., Simoni A., Siniscalchi C., Katsanos D., et al. (2016). A CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drive System Targeting Female Reproduction in the Malaria Mosquito Vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 78–83. doi:10.1038/nbt.3439

Huang Y., Chen Y., Zeng B., Wang Y., James A. A., Gurr G. M., et al. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Knockout of the Abdominal-A Homeotic Gene in the Global Pest, Diamondback Moth (Plutella xylostella). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75, 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.06.004

Huang Y., Wang Y., Zeng B., Liu Z., Xu X., Meng Q., et al. (2017). Functional Characterization of Pol III U6 Promoters for Gene Knockdown and Knockout in Plutella xylostella. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89, 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.08.009

Hwang W. Y., Fu Y., Reyon D., Maeder M. L., Tsai S. Q., Sander J. D., et al. (2013). Efficient Genome Editing in Zebrafish Using a CRISPR-Cas System. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 227–229. doi:10.1038/nbt.2501

Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., Charpentier E. (2012). A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 337, 816–821. doi:10.1126/science.1225829

Kandul N. P., Liu J., Buchman A., Gantz V. M., Bier E., Akbari O. S. (2020). Assessment of a Split Homing Based Gene Drive for Efficient Knockout of Multiple Genes. G3 (Bethesda) 10, 827–837. doi:10.1534/g3.119.400985

Karaminejadranjbar M., Eckermann K. N., Ahmed H. M. M., Sánchez C H. M., Dippel S., Marshall J. M., et al. (2018). Consequences of Resistance Evolution in a Cas9-Based Sex Conversion-Suppression Gene Drive for Insect Pest Management. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, 6189–6194. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713825115

Kyrou K., Hammond A. M., Galizi R., Kranjc N., Burt A., Beaghton A. K., et al. (2018). A CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drive Targeting Doublesex Causes Complete Population Suppression in Caged Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1062–1066. doi:10.1038/nbt.4245

Li M., Yang T., Kandul N. P., Bui M., Gamez S., Raban R., et al. (2020). Development of a Confinable Gene Drive System in the Human Disease Vector Aedes aegypti. eLife 9, e51701. doi:10.7554/eLife.51701

Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K. M., Aach J., Guell M., Dicarlo J. E., et al. (2013). RNA-guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826. doi:10.1126/science.1232033

Marshall J. M., Hay B. A. (2012). Confinement of Gene Drive Systems to Local Populations: a Comparative Analysis. J. Theor. Biol. 294, 153–171. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.10.032

Martins S., Naish N., Walker A. S., Morrison N. I., Scaife S., Fu G., et al. (2012). Germline Transformation of the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella L., Using the piggyBac Transposable Element. Insect Mol. Biol. 21, 414–421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2583.2012.01146.x

Roggenkamp E., Giersch R. M., Schrock M. N., Turnquist E., Halloran M., Finnigan G. C. (2018). Tuning CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drives in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3 (Bethesda) 8, 999–1018. doi:10.1534/g3.117.300557

Shapiro R. S., Chavez A., Porter C. B. M., Hamblin M., Kaas C. S., Dicarlo J. E., et al. (2018). A CRISPR-Cas9-Based Gene Drive Platform for Genetic Interaction Analysis in Candida Albicans. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 73–82. doi:10.1038/s41564-017-0043-0

Unckless R. L., Clark A. G., Messer P. W. (2017). Evolution of Resistance against CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Drive. Genetics 205, 827–841. doi:10.1534/genetics.116.197285

Unckless R. L., Messer P. W., Connallon T., Clark A. G. (2015). Modeling the Manipulation of Natural Populations by the Mutagenic Chain Reaction. Genetics 201, 425–431. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.177592

Valderrama J. A., Kulkarni S. S., Nizet V., Bier E. (2019). A Bacterial Gene-Drive System Efficiently Edits and Inactivates a High Copy Number Antibiotic Resistance Locus. Nat. Commun. 10, 5726–5732. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13649-6

Wang Y., Huang Y., Xu X., Liu Z., Li J., Zhan X., et al. (2020). CRISPR/Cas9-based Functional Analysis of Yellow Gene in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella. Insect Sci. 27, 1–6. doi:10.1111/1744-7917.12870

Werren J. H. (2011). Selfish Genetic Elements, Genetic Conflict, and Evolutionary Innovation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108 (Suppl. 2), 10863–10870. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102343108

Werren J. H., Nur U., Wu C.-I. (1988). Selfish Genetic Elements. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 297–302. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(88)90105-x

Xu J., Chen R. M., Chen S. Q., Chen K., Tang L. M., Yang D. H., et al. (2019). Identification of a Germline‐Expression Promoter for Genome Editing in Bombyx mori. Insect Science 26 (6), 991–999.

Xu X., Harvey-Samuel T., Siddiqui H. A., Ang J. X. D., Anderson M. E., Reitmayer C. M., et al. (2022). Toward a CRISPR-Cas9-Based Gene Drive in the Diamondback Moth Plutella xylostella. CRISPR J. 5, 224–236. doi:10.1089/crispr.2021.0129

You M., Yue Z., He W., Yang X., Yang G., Xie M., et al. (2013). A Heterozygous Moth Genome Provides Insights Into Herbivory and Detoxification. Nature Genetics 45 (2), 220–225.

Keywords: homology-directed repair, non-homologous-end joining, pxyellow, gene-drive efficiency, resistant-allele formation, diamondback moth

Citation: Asad M, Liu D, Li J, Chen J and Yang G (2022) Development of CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene-Drive Construct Targeting the Phenotypic Gene in Plutella xylostella. Front. Physiol. 13:938621. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.938621

Received: 07 May 2022; Accepted: 01 June 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Divya Singh, Chandigarh University, IndiaReviewed by:

Junaid Ali Siddiqui, South China Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Asad, Liu, Li, Chen and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guang Yang, eXhnQGZhZnUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.