94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol., 15 July 2022

Sec. Developmental Physiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.892828

This article is part of the Research TopicExploring Phenotypic Diversity in Ectothermic Reptiles and in Birds: Developmental Physiology Throughout the Lifespan and Across ScalesView all 7 articles

Caroline Cristina-Silva1†

Caroline Cristina-Silva1† Lara Amaral-Silva1†

Lara Amaral-Silva1† Kassia Moreira Santos1

Kassia Moreira Santos1 Gabriela Monteiro Correa1

Gabriela Monteiro Correa1 Welex Candido da Silva1

Welex Candido da Silva1 Marcia H. M. R. Fernandes2

Marcia H. M. R. Fernandes2 Glauber S. F. da Silva3

Glauber S. F. da Silva3 Luciane H. Gargaglioni1

Luciane H. Gargaglioni1 Maria C. Almeida4

Maria C. Almeida4 Kenia C. Bicego1*

Kenia C. Bicego1*Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channels are sensitive to warm ambient temperatures (Tas), triggering heat loss responses in adult rats in a Tas range of ∼26–30°C. In birds, however, the thermoregulatory role of TRPV4 has never been shown. Here, we hypothesized that stimulation of TRPV4 induces thermolytic responses for body temperature (Tb) maintenance in birds, and that this function is already present in early life, when the Ta range for TRPV4 activation does not represent a warm condition for these animals. We first demonstrated the presence of TRPV4 in the dorsal and ventral skin of chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) by immunohistochemistry. Then, we evaluated the effects of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747, and the TRPV4 antagonists, HC067047 and GSK2193874, on Tb and thermoeffectors at different Tas in 5-day-old chicks and 60-day-old adult chickens. For the chicks, RN1747 transiently reduced Tb both in thermoneutrality (31°C) and in a cold Ta for this phase (26°C), which relied on huddling behavior inhibition. The TRPV4 antagonists alone did not affect Tb or thermoeffectors but blocked the Tb decrease and huddling inhibition promoted by RN1747. For the adults, TRPV4 antagonism increased Tb when animals were exposed to 28°C (suprathermoneutral condition for adults), but not to 19°C. In contrast, RN1747 decreased Tb by reducing metabolic rate and activating thermal tachypnea at 19°C, a Ta below the activation range of TRPV4. Our results indicate that peripheral TRPV4 receptors are functional in early life, but may be inhibited at that time when the range of activation (∼26–30°C) represents cold Ta for chicks, and become physiologically relevant for Tb maintenance when the activation Ta range for TRPV4 becomes suprathermoneutral for adult chickens.

The maintenance of body temperature (Tb) in an endotherm exposed to ambient temperature (Ta) variation depends on the activity of neural circuits, which detect Ta in the peripheral thermoreceptors, integrate the thermal information in the brain, and recruit appropriate thermoeffectors for heat gain or heat loss (Bicego et al., 2007; Morrison, 2016). The thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels, called thermo-TRPs, emerged two decades ago as putative molecules involved in thermosensitivity (Patapoutian et al., 2003; Wang and Siemens, 2015). They are located on the cell membrane of a variety of cell types, such as neurons and epithelial cells, and have six transmembrane domains. In vitro studies of thermo-TRPs in mammals have shown that TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPM3 are activated by noxious heat, TRPA1 is activated by noxious cold, TRPM8 and TRPC5 are activated by innocuous cold, and TRPM2, TRPM4, TRPM5, TRPV3, and TRPV4 are activated by moderate heat (Guler et al., 2002; Clapham, 2003; Patapoutian et al., 2003). Functional evidence (in vivo) of a thermoregulatory role for thermo-TRPs, however, is available for only a few channels, including TRPM8, TRPV3 and TRPV4, in rodents (Peier et al., 2002; Almeida et al., 2012; Vizin et al., 2015; Wang and Siemens, 2015; Scarpellini et al., 2019). In vitro, TRPV4 channels are specifically stimulated at temperatures of 27–34°C (Guler et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2002; Kauer and Gibson, 2009). At least in rats they are expressed peripherally in the keratinocytes (Guler et al., 2002). In vivo, we have shown that peripheral TRPV4 receptors activate warmth-defense responses when adult rats are exposed to a range of Tas between ∼26 and 30°C (Vizin et al., 2015). Besides that, hypothalamic TRPV4 channels, which seems to be modulated by neurochemical signaling instead of changes in temperature, are also important for thermoregulatory responses to warm conditions in adult rats (Vizin et al., 2015; Scarpellini et al., 2019).

TRP channels are well preserved throughout evolution, and a phylogenetic analysis in birds, a vertebrate group that seems to have evolved endothermy following a different pathway from mammals (Legendre and Davesne, 2020), indicates that they have a copy of each gene coding for TRPs: V1, V2, V3, V4, V6, M2, M5, M8, and A1 (Saito and Shingai, 2006). Some studies in vitro show that similarly to mammals, chicken TRPM8 is activated in mild cold and by menthol (Chuang et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2009), whereas chicken TRPA1 is activated by noxious heat, contrary to what is found in mammals (Saito et al., 2014). Additionally, chicken TRPV1 also senses noxious heat (Jordt and Julius, 2002) and seems to be involved in the Tb drop during endotoxemic shock in chicks (Nikami et al., 2008). TRPV4 channels were described in the rictus associated with Herbst corpuscle mechanoreceptors in pigeons (Cabo et al., 2013). However, as far as we know there is no study showing the presence of any TRP channels in the skin or exploring their role in avian thermoregulation (in vivo).

In mammals and birds, along with development and growth, the maturation of thermogenesis and increase in insulation make the thermal comfort and thermoneutral zone shift overtime from warmer to colder Tas (Alberts, 1978; Nichelmann and Tzschentke, 2002; Mortola and Labbe, 2005). As a consequence, changes in thermoregulation are observed during the animal’s development, as thermosensitivity changes with aging, i.e., a Ta that is considered neutral in early life, is normally supraneutral for adults. In this way, precocial birds are excellent models for studying the development of thermogenesis since endothermy is already present as soon as they hatch and the shift in thermosensitivity can be observed by activation of heat loss/heat conservation thermoeffectors in early life (Mathiu et al., 1991; Khandoker et al., 2004; Mortola and Maskrey, 2011; Toro-Velasquez et al., 2014; Cristina-Silva et al., 2021; Amaral-Silva et al., 2022).

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that TRPV4 stimulation induces thermolytic responses for Tb maintenance in birds at warm Tas, and that this function is already present in early life, when the TRPV4 activation Ta range does not represent a suprathermoneutral condition. First, immunohistochemistry was used to detect TRPV4 channels in the dorsal and ventral skin of 60-day-old adult chickens. To assess the role of TRPV4 channels in thermoregulation in vivo, we treated 5-day-old chicks and 60-day-old chickens with a selective agonist (RN1747) and antagonists (HC067047 and GSK 2193874) of TRPV4 (Vincent et al., 2009; Everaerts et al., 2010). The effects of the TRPV4 agonist and antagonists were evaluated on Tb and the thermoeffectors, such as oxygen consumption (index of thermogenesis), pulmonary ventilation (index of thermal tachypnoea in heat) and huddling behavior (heat conservation mechanism in chicks) in different Tas.

Hatchlings from Gallus gallus domesticus, of the Carijo lineage (Plymouth rock), were locally supplied (Globoaves, Itirapina, SP, Brazil) and raised at the Department of Animal Morphology and Physiology (FCAV-UNESP). The chicks were kept in climatic chambers (Premium Ecologica, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) at 31–32°C (age-appropriate) with a light:dark cycle of 14:10 h (lights on at 6 a.m.) (Amaral-Silva et al., 2020, Amaral-Silva et al., 2021; Cristina-Silva, 2021). The experiments were conducted in 5-day-old chicks (60–70 g), a phase when thermogenesis is considered to be fully established (Nichelmann and Tzschentke, 2002; Tazawa et al., 2004; Amaral-Silva et al., 2020).

A separate group of Carijo hatchlings (Globoaves, Itirapina, SP, Brazil) were housed in climatic chambers of the FCAV-UNESP-Jaboticabal poultry sector, and raised at an appropriate Ta for each stage of development (first week, 31–32°C; second week, 25–28°C; third week, 20–22°C; forth through eighth weeks, 19–20°C; De Oliveira et al., 2006). A light:dark cycle of 14:10 h was kept the entire time. The experiments were then conducted when the birds achieved 55–65 days (2.5–3.5 kg), an age when birds were considered adults for this lineage.

All animals were provided standard food and water ad libitum. The experiments were carried out between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to avoid any influence of the daily Tb cycle. All procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the National Animal Experimentation Control Council (CONCEA-Brazil) and with the approval of the local Animal Care and Use Committee (CEUA-FCAV-UNESP-Jaboticabal).

After the end of the experiments, 60-day-old adult chickens were deeply anesthetized and skin from the dorsal and ventral regions of the body was sampled, allocated in embedding cassettes and immediately immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution (PFA, Sigma-Aldrich Brazil Ltda. Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) for 2 h. In sequence, the cassettes containing the skin were immersed in 70% alcohol solution for at least 2 days. The skin samples were then embedded in paraffin and the blocks were sliced in 40-µm transversal sections using a microtome (Leica RM2255, Wetzlar, HE, Germany).

For immunohistochemistry, the sections were deparaffinized and incubated for 30 min in an antigen retrieval solution (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 70°C. Subsequently, the slices were washed in 1.5% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, and were then incubated in 3% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich Brazil Ltda. Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) for 1 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. The slices were incubated at 25°C for 24 h with a rabbit anti-TRPV4 primary antibody (Abcam 39260; dilution 1:200; Cambridge, United Kingdom), followed by a 4-h incubation in darkness with a fluorescent anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488; dilution 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Waltham, MA, United States). Finally, the sections were placed on gelatin-coated slides. After drying, they were covered by coverslips glued with a specific fluorescence preservative (ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, EUA) and observed under a microscope (Axio Imager Z2; Carl Zeiss do Brasil Ltda. Sao Paulo, Brazil) at a wavelength of 488 nm. A negative control was prepared following the same steps, except for the absence of the primary antibody.

Chicks, free to walk around the brooder (Protocols 1 and 2, described below), had their Tb measured by a colonic sensor (Yellow spring Instrument, Co., Ohio, United States). The sensor was inserted 3 cm through the cloaca into the colon and was connected to a tele-thermometer (45TUC, Yellow spring Instrument Co., Ohio, United States). To avoid the influence of stress on Tb due to manipulation on the day of the experiment, the chicks were previously trained to the procedure from day 2 to day 4 (3 measurements/day, 1/hour). Chicks in the respirometry chamber (Protocol 4, described below) had their Tb monitored by telemetry using a temperature-sensitive tag (Biomark HPR Plus Reader, Boise, ID, United States) implanted in the coelomic cavity. For this, chicks were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% for induction and 1% for maintenance in pure O2, using a face mask). The tag was then inserted through the skin and abdominal muscle using an application needle (AnimalTAG, Sao Carlos, SP, Brazil). The small incision point was closed using surgical glue (Dermabond Topical Skin Adhesive; Johnson & Johnson, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil). Antibiotic (enrofloxacin, intramuscular; 10 mg kg−1; Bayer SA, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) and analgesic anti-inflammatory (flunixin meglumine, intramuscular; 2.5 mg kg−1; MSD Saude Animal, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) agents were prophylactically administered, and the chick stayed in observation until recovery. The entire procedure lasted about 10 min. The sensor was implanted 2–3 days before the experiments. At the day of the experiment, individual Tbs were recorded in real time by telemetry using a Biotherm reader (Biomark HPR Plus Reader, Boise, ID, United States) and uploaded to a computer (BioTerm software). Both sensors (colonic and abdominal) were calibrated against a certified thermometer (0.1°C precision). The Tbs measured by the colonic and abdominal sensors were highly correlated (R2 = 0.9782).

The Tb of adult animals (Protocols 5 and 6 described below) was monitored by temperature dataloggers (SubCue, Calgary, AB, Canada) implanted in the coelomic cavity via median laparotomy. To this end, animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (5% for induction using a face mask followed by intubation and maintenance with 1% in pure O2). A small incision in the skin and muscle layers at the ventral midline, just caudal to the breast muscle, allowed for the insertion of the sensor into the coelomic cavity. Subsequently, the abdominal muscles and skin were sutured in layers, the isoflurane flow was closed, and we waited until animal itself removed the anesthesia tube from the trachea by reflex. The chickens were prophylactically treated with antibiotic (enrofloxacin, intramuscular; 10 mg kg−1; Bayer SA, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) and with analgesic anti-inflammatory (flunixin meglumine, intramuscular; 2.5 mg kg−1; MSD Saude Animal, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) agents. The surgery was performed at least 2 days before the experiment. At the end of the experiments, chickens were deeply anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (250 mg kg−1; Sigma-Aldrich Brasil Ltda. Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) to remove the sensors. The data stored in the sensors was uploaded to the computer (Subcue software, Calgary, AB, Canada) and calibrated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Oxygen consumption (

Pulmonary ventilation (

The selective TRPV4 antagonist, HC-067047 {2-Methyl-1-[3-(4-morpholinyl) propyl]-5-phenyl-N-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxamide} (Everaerts et al., 2010; Shibasaki et al., 2015), was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom). It was dissolved in a solution of 10% ethanol in sterile saline, and the doses of 10, 50, and 100 μg kg−1 were chosen based on results we previously presented in rats (Vizin et al., 2015) and on pilot experiments using chickens. The selective TRPV4 antagonist, GSK 2193874 [3-(1,4′-Bipiperidin)-1′-ylmethyl]-7-bromo-N-(1-phenylcyclopropyl)-2-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-4-quinolinecarboxamide; Cheung et al., 2017), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Brazil Ltda (Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil). It was dissolved in a solution of 1% DMSO in sterile saline, and the doses of 100 and 500 μg kg−1 were chosen based on our previous study (Scarpellini et al., 2019). Both antagonists were applied intramuscularly (i.m.) in the leg (Vizin et al., 2015).

The selective TRPV4 agonist, RN1747 [1-(4-Chloro-2-nitrophenyl) sulfonyl-4-benzylpiperazine, Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom], was dissolved in propylene glycol at concentrations of 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mg ml−1 and applied topically to the skin for activation of cutaneous TRPV4 channels. Doses of 0.75, 1.87, and 3.75 mg kg−1 were applied to the dorsal skin in chicks and to the dorsal and ventral skin in adults. The liquid was carefully applied with the help of a needleless syringe and it was well spread on the animal’s surface with circular movements. Because of its viscous consistency, the solution did not flow out of the applied area. For the chicks, we applied ∼0.3 ml of the RN1747 solution and for the adults, a volume of ∼11.25 ml, with half of the volume applied to each portion of the skin (dorsal or ventral) (total of application in both ages: 3.75 ml kg−1). The choice of doses and application method were based on a previous study (Vizin et al., 2015).

Protocols 1-4 were performed in 5-day-old Carijo chicks, and Protocols five and six were performed in 60-day-old adult Carijo chickens. To investigate the effects of TRPV4 activation on thermoeffectors, we combined pharmacological blockage of TRPV4 (using specific antagonists) with both chemical (topical application of RN1747 in chicks and adults) and thermal (exposure of adults to 28°C) activation of the channel. The animals were kept at 30–31°C for at least 60 min in order to promote skin vasodilation and deliver the circulating antagonist (i.m. injected) to its presumed site of action (skin receptors) before being subjected to the thermal stimulus (26°C for chicks; 28 and 19°C for adults), as previously described in rats (Almeida et al., 2012; Vizin et al., 2015). The temperatures of 31 and 26°C were chosen for Protocols 1–4 because 31°C is thermoneutral for five- to 8-day-old chicks (Coleone et al., 2009; Amaral-Silva et al., 2021, 2022; Cristina-Silva et al., 2021) and 26°C is in the range of TRPV4 activation in vivo, but is considered to be cold for chicks (Vizin et al., 2015; Amaral-Silva et al., 2021, 2022; Cristina-Silva et al., 2021). Different animals were used for each protocol, and they were deeply anesthetized and killed immediately after the end of the experiments.

Chicks received: 1) topical application of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747 (0.2, 0.5 or 1.0 mg ml−1), or its vehicle (100% propylene glycol; 3.75 ml kg−1) on the dorsal skin; or 2) intramuscular (i.m.) injection of the TRPV4 antagonist, HC067047 (10, 50 or 100 μg kg−1), or its vehicle (90% saline +10% ethanol; 1 ml kg−1). Colonic temperature was measured just before and hourly up to 240 min after each treatment.

Chicks were injected with 50 μg kg−1 (i.m.) of HC067047 or its vehicle (1 ml kg−1). One hour later, they were topically applied with RN1747 (0.5 mg ml−1) or its vehicle (3.75 ml kg−1). This generated four treatment combinations: 1) vehicle of HC067047 + vehicle of RN1747 (sham); 2) HC067047 + vehicle of RN1747 (antagonist effect only); 3) vehicle of HC067047 + RN1747 (agonist effect only); 4) HC067047 + RN1747 (inhibition of TRPV4 chemical activation). Colonic temperature was measured before the first treatment and hourly for five consecutive hours in all groups. The antagonist and agonist doses were chosen based on the results of the Protocol 1. The experiment was conducted: 1) at a neutral Ta of 31°C during the whole period of Tb measurements; and 2) started at 31°C, which was maintained for 1 h after the antagonist injection (to facilitate access of the circulating drug to the skin, as explained above), and at the moment of the agonist topical application, the Ta was reduced to 26°C.

One day before the experiments, chicks were separated into groups of five individuals and kept in climatic chambers at 31°C. On the following day, chicks were injected with HC067047 (50 μg kg−1) or vehicle (90% saline +10% ethanol; 1 ml kg−1) and maintained at 31°C for 60 min. Then, they were topically applied with RN1747 (0.5 mg ml−1) or its vehicle (100% propylene glycol; 3.75 ml kg−1) and exposed to 26°C for the manifestation of cold-induced huddling behavior. The treatment combinations presented in Protocol two were repeated in this protocol (vehicle of HC067047 + vehicle of RN1747; HC067047 + vehicle of RN1747; vehicle of HC067047 + RN1747; and HC067047 + RN1747). Chicks were monitored using a webcam (LifeCam HD-3000, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, EUA) fixed about 1 m above the experimental chambers and programmed to take pictures with a 2-min interval from the time of pretreatment up to about 270 min after the topical treatment. The number of single chicks (ungrouped animals) was counted, and the area occupied by the five chicks in the group was measured using ImageJ (FIJI) to infer huddling behavior for heat conservation (Dantonio et al., 2015).

The selective TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874, was used in this protocol (Cheung et al., 2017; Scarpellini et al., 2019) to confirm the TRPV4 inhibition effect on the Tb of chicks and to verify the metabolic thermoeffectors affected. Resembling Protocols 2 and 3, chicks were pretreated with 50 μg kg−1 (i.m.) of the TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874, or its vehicle (1% DMSO; 1 ml kg−1), and after 60 min, were topically applied with 0.5 mg ml−1 of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747, or its vehicle (100% propylene glycol; 3.75 ml kg−1). This also generated four treatment combinations: 1) vehicle of GSK2193874 + vehicle of RN1747 (sham); 2) GSK2193874 + vehicle of RN1747 (antagonist effect only); 3) vehicle of GSK2193874 + RN1747 (agonist effect only); 4) GSK2193874 + RN1747 (inhibition of TRPV4 chemical activation). The chicks in this protocol were allocated for 30 min in the respirometer for habituation. After that, oxygen fraction was recorded continuously from 20 min before the pretreatment until 240 min after the topical treatment. Ventilation was recorded during 2 min every 20 min, when the respirometer was closed for baseline recordings (FiO2).

Sixty-day-old chickens, previously implanted with a Tb sensor, were exposed to 30°C for 50 min before the experiments (to facilitate the access of the circulating drug to the skin, as explained above). Tb was measured during this phase. After that, this protocol was conducted in two different ways: 1) animals were injected with 100 or 500 μg kg−1 of the TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874, or its vehicle (1% DMSO; 1 ml kg−1) and transferred to a respirometer at 28°C (warm for this age) for recordings of Tb,

After the initial warming phase at 30°C (see Protocol 5), 60-day-old chickens were topically applied with 0.5 mg ml−1 of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747, or its vehicle (100% propylene glycol; 3.75 ml kg−1) equally distributed on the ventral and dorsal skin. They were then transferred to a respirometer at 19°C for recordings of Tb,

All data are presented as mean ± standard error. The effects on the peak of delta Tb (calculated by subtracting the peak value of the treatments from the respective controls) of the animals that received different doses of the TRPV4 agonist and the antagonist were compared using one-way ANOVA. The effects of the TRPV4 agonist and antagonists on the variables evaluated in chicks (Tb,

Demonstration of the presence of TRPV4 channels (green immunostaining) in the ventral and dorsal skin of chickens is shown in fluorescence photomicrographs (Figure 1A,B, respectively). TRPV4 was expressed in the layers of the dermis and subcutis both in the ventral and dorsal sites. A negative control is presented in Figure 1C to confirm the absence of unspecific staining without the primary antibody, anti-TRPV4.

FIGURE 1. Representative photomicrographs of immunostaining for TRPV4 in the skin of adult chickens: ventral (A) and dorsal (B) cut of the skin; negative control without the primary antibody (C). TRPV4 is seen as a green staining. Arrow: Stratum corneum; 1: Epidermis; 2: Dermis; 3: Muscle.

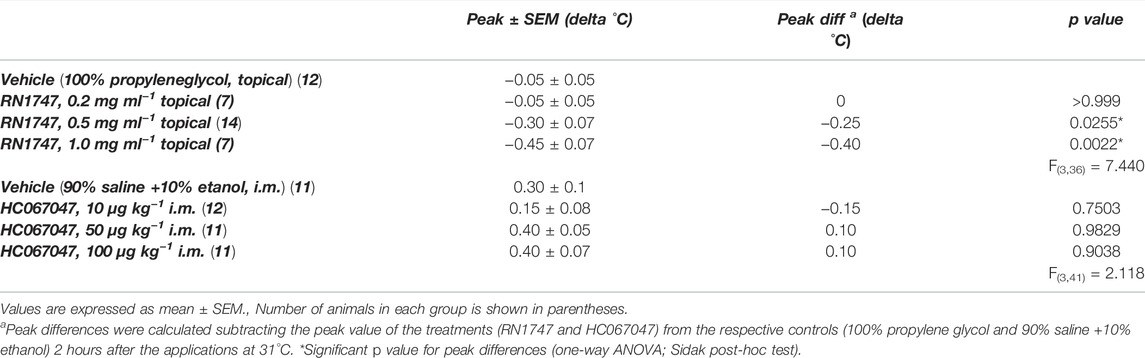

Protocol 1—The topical application of the selective agonist for TRPV4, RN1747, significantly reduced the peak of delta Tb (at 120 min for all) in 5-day-old chicks when applied in concentrations of 0.5 and 1.0 mg ml−1, but not when applied at 0.2 mg ml−1 (Table 1). On the other hand, the selective TRPV4 antagonist, HC067047, alone did not affect the chicks’ Tb in the three doses applied, 10, 50 and 100 μg ml−1 (peak at 120 min; Table 1).

TABLE 1. Peak of delta body temperature (Tb) of 5-day-old chicks under thermoneutral condition (Ta = 31°C) that received either topical administration (3.75 ml kg−1) of the TRPV4 agonist RN1747 (0.2, 0.5 and 1 mg ml−1) on the dorsal skin, or intramuscular (i.m.; 1 ml kg−1) injection of the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (10, 50 or 100 μg kg−1), compared to the respective vehicles (topical: propylene glycol; i.m.: 90% saline +10% ethanol).

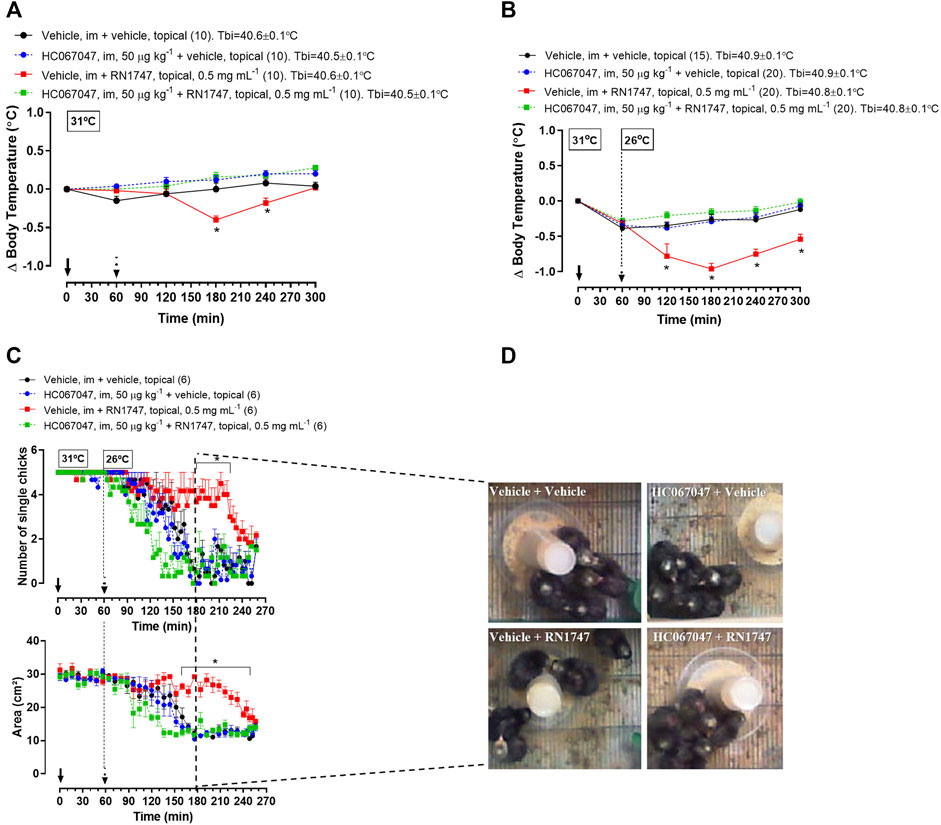

Protocol 2—RN1747 (0.5 mg ml−1) caused a decrease in Tb from 120 to 180 min following application (Figure 2A; 180–240 min; treatment effect: p < 0.0001, F(3, 36) = 10.42) when the chicks were in the thermoneutral condition. A more accentuated Tb decrease from 60 to 240 min following application of RN1747 (Figure 2B; 120–300 min; treatment effect: p < 0.001, F(3, 71) = 16.79) was observed when chicks were exposed to cold (26°C—activation range of TRPV4). The antagonist injection alone had no effect on Tb, which followed the same pattern as the control animals (vehicle i.m. + vehicle topical). However, the HC067047 effectiveness in inhibiting TRPV4 was demonstrated by the inhibition of the Tb decrease caused by the agonist, RN1747, at both thermoneutral and cold conditions (Figures 2A,B).

FIGURE 2. (A,B) Effect of pre-treatment with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (intramuscular injection, i.m.; 50 μg kg−1; vehicle is 90% saline +10% ethanol; 1 ml kg−1) on the body temperature change induced by the TRPV4 agonist RN1747 (topical application on the dorsal skin; 0.5 mg ml−1; vehicle is 100% propyleneglycol; 3.75 ml kg−1) in 5-day-old chicks under thermoneutral condition (Ta = 31°C; A) or exposed to cold (Ta = 26°C; B). Tbi, initial body temperature. C) Influence of the pre-treatment with HC067047 on the effect of RN1747 on the huddling behavior induced by cold exposure (Ta = 26°C) in 5-day-old chicks, as assessed by the number of single chicks (top plot) and the area occupied by the group of five chicks (bottom plot). D) Representative images of each treatment showing the area occupied by the animals at the time 180 min from the graphs in C (2 hours after the agonist application). All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. The continuous arrow indicates the moment of the antagonist injection and the dashed arrow indicates the time of the topical application of the agonist. The number of animals in each group is shown in parentheses. *p < 0.05, significant difference from the vehicle group at the same time point (two-way ANOVA; Sidak post-hoc test).

Protocol 3—The effect of the agonist and antagonist drugs on Tb was accompanied by the behavioral thermoregulation. Exposure to cold (26°C) induced huddling behavior in the 5-day-old chicks, which was observed by the reduction of the number of single chicks (Figure 2C; p < 0.001, F(3, 20) = 47.65) and the area occupied by the group of chicks (Figure 2C; p < 0.001, F(3, 20) = 59.08). Topical application of RN1747 inhibited the huddling behavior in response to cold, as it did not reduce the number of single chicks (Figure 2C; 170–220 min; p < 0.001, F(3, 20) = 11.39) or the area occupied by the group of chicks (Figure 2D; 160–250 min; p < 0.001, F (3, 20) = 50.21). Injection of HC067047 alone did not affect the chicks’ behavior, but its injection prevented the inhibition of huddling caused by the agonist, RN1747; thus, the chicks huddled in response to cold, similarly to the controls. The effects of cold and pharmacological activation/inhibition of TRPV4 in 5-day-old chicks’ behavior is exemplified in images in Figure 2D. It is possible to observe that the only group showing no huddling is the one that received the “vehicle + RN1747” treatment.

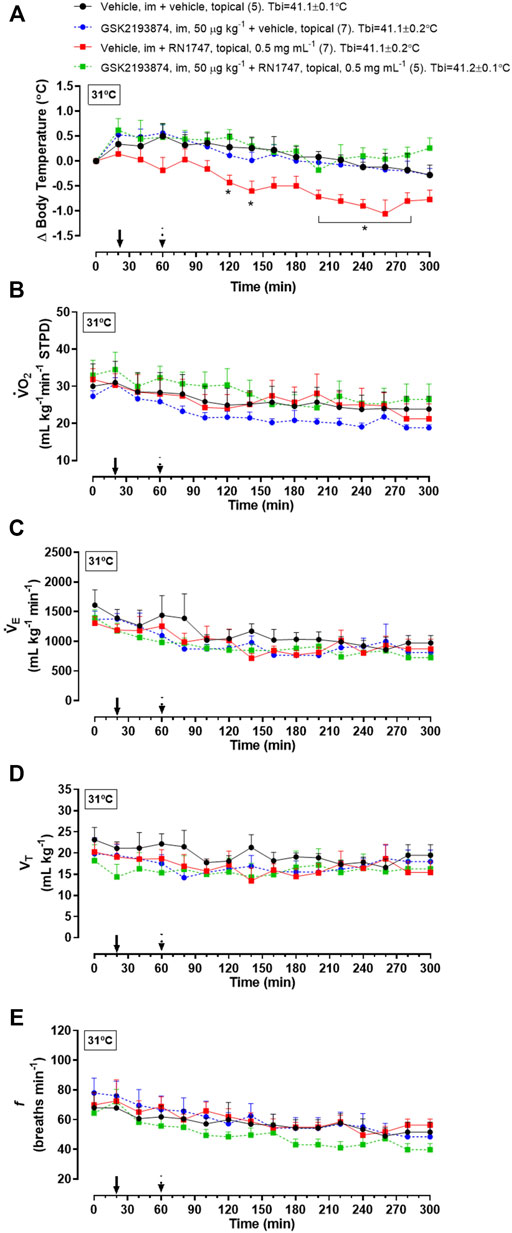

Protocol 4—Under thermoneutrality, the selective TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874, had a similar effect on Tb compared to the antagonist, HC067047. By itself, it did not affect Tb, but it prevented the Tb decrease caused by RN1747 (Figure 3A; 120–140 min; 200–280 min; treatment effect: p < 0.01, F(3,21) = 5.40), and the chicks’ Tb was comparable to that of the controls. Despite the Tb changes, no difference in

FIGURE 3. Effect of pre-treatment with the TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874 (intramuscular injection, i.m.; 50 μg kg−1; vehicle is DMSO 1%; 1 ml kg−1), on change in body temperature (delta; A), oxygen consumption (

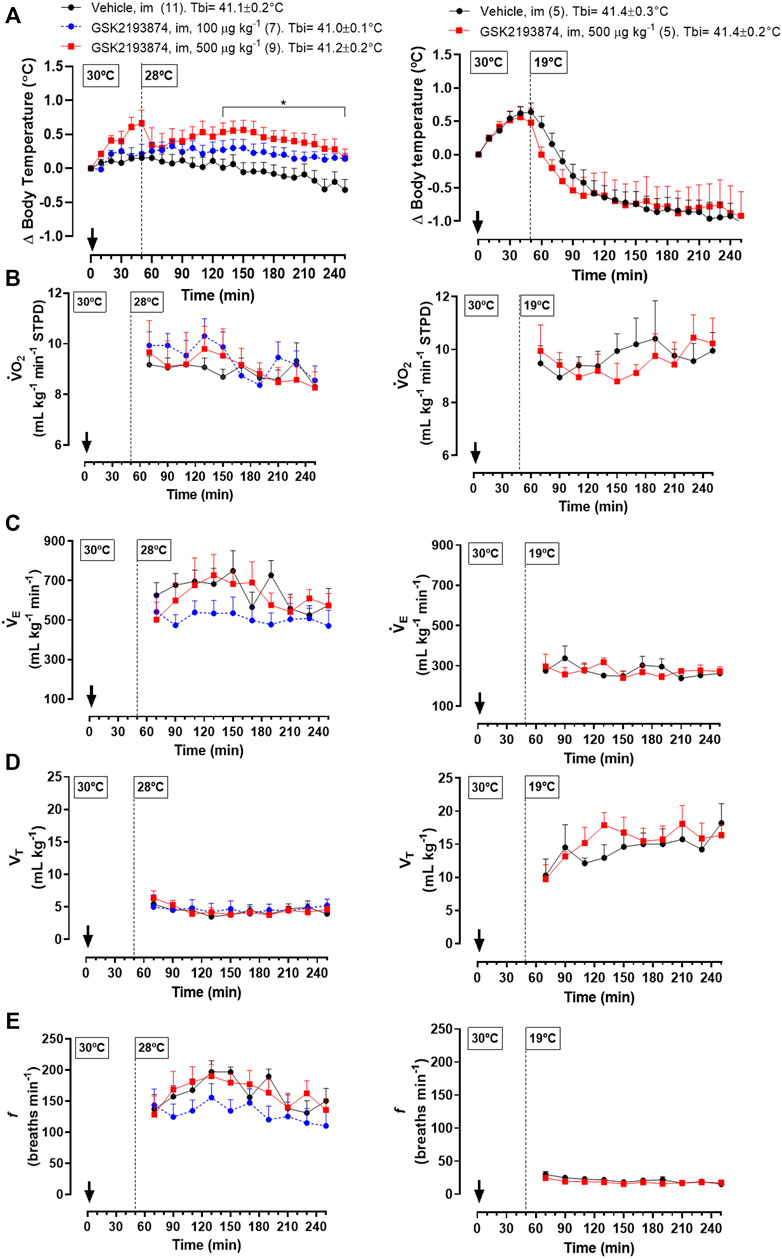

Protocol 5—Injection of 500 μg kg−1 (i.m.) of GSK 2193874 in adult chickens resulted in a higher Tb compared to the vehicle group at 28°C (Figure 4A left panel; 130–260 and 230 min; treatment effect: p = 0.01, F(2, 24) = 5.13). A lower dose of the antagonist (100 μg kg−1) did not affect Tb significantly. No difference in

FIGURE 4. Effect of intramuscular injection (i.m.; 1 ml kg−1) of the TRPV4 antagonist, GSK2193874 (100 and 500 μg kg−1), or vehicle (1% DMSO) on body temperature (Tb; A), oxygen consumption (

Different from the exposure to 28°C, chickens at 19°C and injected with the higher dose of GSK 2193874 (500 μg kg−1) did not differ in Tb from the vehicle group (Figure 4A, right panel; treatment effect: p = 0.90, F(1,8) = 0.02). In this condition, the antagonist also did not affect the thermoeffectors

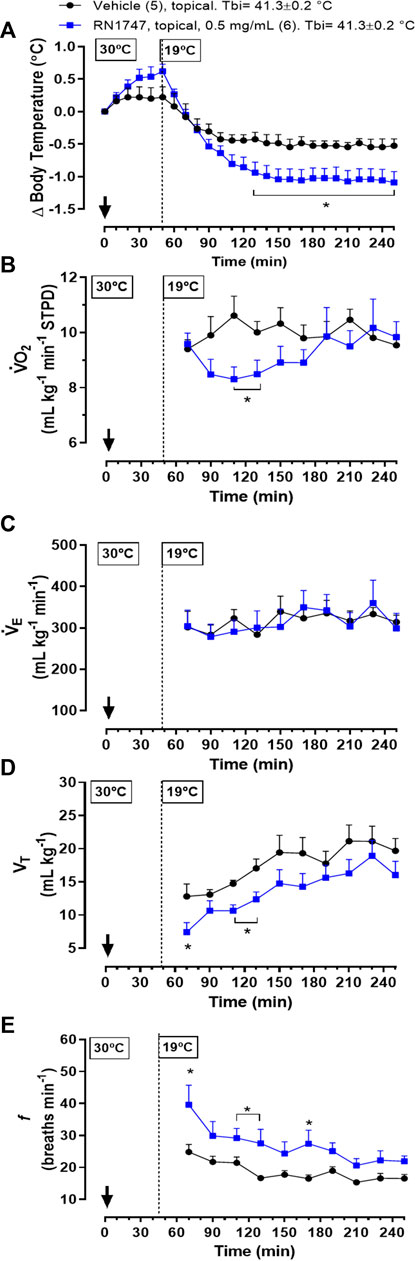

Protocol 6—Topical application of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747, in 60-day-old chickens at 19°C resulted in a significant drop in Tb when compared to the vehicle group (Figure 5A; 130–250 min; treatment effect: p = 0.03, F(1, 9) = 7.03). This Tb decrease in response to the agonist was preceded by a reduction in

FIGURE 5. Effect of topical application (both dorsal and the ventral skin surfaces; 3.75 ml kg−1; ∼6 ml each side) of the TRPV4 agonist, RN1747 (0.5 mg ml−1), or vehicle (100% propylene glycol) on body temperature (Tb; A), oxygen consumption (

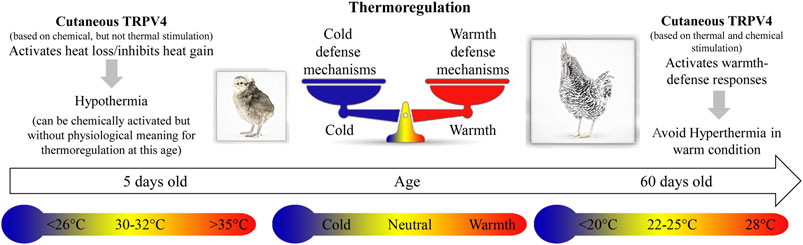

Our results show the first evidence of the presence of TRPV4 channels in the skin of the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the body, and their role in the activation of warmth-defense responses in birds. These thermosensors are functional in early life, despite having no physiological meaning for thermoregulation in chicks, which sense its temperature activation range (∼26–30°C) as cold to neutral (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. The cartoon illustrates the thermoregulatory effects of stimulation of cutaneous TRPV4 in chicken at different ages, 5 and 60 days old. In 5-day-old chicks, chemical stimulation of the TRPV4 receptors induces hypothermia, and specific antagonists inhibit this response. At this age, 30–32°C is considered thermoneutral, while 26°C or less and 35°C or more are below and above thermoneutrality, respectively. In 60-day-old chickens (adults), thermal stimulation (warm exposure; ∼28°C) of the TRPV4 receptors avoids hyperthermia. Moreover, at this age, chemical stimulation of TRPV4, even in cold condition (below 20°C), activates heat loss (warmth-defense) responses.

Immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of TRPV4 channels spread throughout the dermis of chickens. At least in humans, these channels are highly diffuse in skin, including vascular endothelial cells, eccrine sweat gland secretory cells, and keratinocytes (Kida et al., 2012; Fusi et al., 2014; Olivan-Viguera et al., 2018). In rats, evidence exists for the presence of TRPV4 in keratinocytes (Guler et al., 2002; Wang and Siemens, 2015). In this case, it is suggested that some humoral pathways promote communication between the keratinocytes in the epidermis and the nerve endings in the dermis, which is essential for the thermal information to be sent to the brain (Wang and Siemens, 2015). In chickens, TRPV4 may reside in primary afferent sensory neurons and/or other cell types that are connected to nerve endings, which make possible the transmission of afferent signals for thermoeffector activation.

Chemical stimulation of cutaneous TRPV4 (topical application of a selective agonist) resulted in a decrease of Tb in 5-day-old chicks when allocated in both thermoneutral (31°C) and cold (26°C) conditions. The hypothermia observed during TRPV4 stimulation occurred together with the inhibition of huddling in response to cold (26°C), a behavioral heat conservation mechanism well known in birds, including chicken chicks (Kleiber and Winchester, 1933; McKechnie and Lovegrove, 2001; Gilbert et al., 2010; Amaral-Silva et al., 2022). Both the Tb decrease and the prevention of huddling behavior were inhibited by pretreatment with the TRPV4 antagonist (HC067047) at a dose that did not affect behavior when injected alone, highlighting the specificity of TRPV4 in this response. Interestingly, a similar pattern is observed in adult rats, i.e., the selection of colder Tas upon chemical activation of cutaneous TRPV4, and the inhibition of cold-seeking behavior by HC067047 following exposure to 28–31°C (Vizin et al., 2015).

Despite the pharmacological evidence that 5-day-old chicks have functional TRPV4 channels, and that HC06747 blunted the agonistic effect, the inhibition of TRPV4 channels alone at 31°C or 26°C did not increase Tb, as observed in adult rats (Vizin et al., 2015; Scarpellini et al., 2019). This is probably because the TRPV4 thermosensors are not thermally activated at this age by either of the Tas used. Even though the chicks were exposed to Tas in the range that this thermoreceptor is shown to sense in vivo (Vizin et al., 2015), 31 and 26°C do not represent a warm Ta for the 5-day-old chicks. In fact, a Ta of 26°C triggers activation of thermogenesis instead of thermolysis in the first week of life in chicks (Amaral-Silva et al., 2021; Cristina-Silva et al., 2021; Amaral-Silva et al., 2022). Thus, these animals are not expressing any heat loss response, which would be inhibited by HC06747 in the case where TRPV4 was active, and Tb would be consequently increased by the lack of this response. We speculate that, at this age, TRPV4 channels may be chemically inhibited or present a very high activation threshold, becoming physiologically relevant only for older animals.

Later in life, when 28°C represents a supraneutral Ta for adult chickens, TRPV4 seems to be active and responsive, preventing hyperthermia in this condition. In support of this, when the adult chickens were exposed to mild cold (19°C), which does not activate TRPV4, the inhibition of these channels, using the same dose of antagonist as that which reduced Tb at 28°C, did not affect Tb. The hyperthermic response to the TRPV4 antagonist at 28°C did not involve thermogenesis, considering that GSK2193874 did not change O2 consumption. Besides that, the thermal tachypnea (high f and low VT, known to provide respiratory heat loss; Hammel and Pierce, 1968; Richards, 1970; Mortola and Maskrey, 2011) was also not affected by the inhibition of TRPV4. In this case, if GSK2193874 only inhibited cutaneous vasodilation, an impairment of heat dissipation through the body-ambient thermal gradient (∼41.1–28°C) would be enough to cause the observed Tb increase (Richards, 1970; Wolfenson et al., 1981). This suggests that TRPV4 might maintain regular Tb in chickens exposed to mild suprathermoneutral Tas by peripheral vasomodulation, which may be enough for thermoregulation in the range of Tas sensed by TRPV4. Although it was not measured here, there is evidence that cutaneous vasodilation is activated by chemical stimulation of TRPV4 in adult rats (Vizin et al., 2015) and humans (Fujii et al., 2019). In the latter, however, that response is partially, but not completely, inhibited by local microinfusion of HC067047 or GSK2193874 (Fujii et al., 2021). This issue remains to be confirmed in birds. Another matter for future investigation is the possibility that TRPV4 channels are present in the brain of chickens. If this was the case, an influence of GSK2193874 inhibiting brain TRPV4 channels would be speculated. At least in rats, TRPV4 channels located in the hypothalamus region seem to play a role in thermolytic responses together with those channels present in the skin (Vizin et al., 2015; Scarpellini et al., 2019). Regarding chickens, although one cannot rule out a possible central action of GSK2193874, its efficiency in inhibiting cutaneous TRPV4 channels was confirmed by blockade of the hypothermia induced by topical application of RN1747 in chicks (Figure 3).

When TRPV4 was chemically stimulated at 19°C, adult chickens decreased Tb, similarly to what was observed in chicks. This response in the adults relied on the activation of tachypnea, providing evaporative heat loss (Wolfenson et al., 1981; Arad and Marder, 1982), and also on metabolic rate inhibition, reducing heat gain (Amaral-Silva et al., 2021; Amaral-Silva et al., 2022). In this case, the pharmacological effect of the TRPV4 agonist may be more potent to stimulate the specific skin sensors for activating those thermoeffectors than stimulation by the warm condition at 28°C. A possibility exists that such a Ta is inside the common temperature range of activation of other temperature-sensitive receptors, for example TRPV3 (Luo and Hu, 2014; Wang and Siemens, 2015; Ishikawa et al., 2019), overlapping the influences of different thermoreceptors.

Our data indicate the presence of TRPV4 channels in the chicken’s dermis, which present a thermolytic role for Tb maintenance. Chicken TRPV4 thermosensors are functional in early life, when the range of TRPV4 activation (∼26–31°C) actually represents a cold to thermoneutral ambient condition. In this phase, these channels may remain suppressed, but become physiologically relevant only later in life, when the Tas they sense represent a warm condition for adult chickens and thermolysis is evoked to maintain Tb. If there is a specific thermoeffector activated by TRPV4 channels in warm conditions, or if they induce small modulations of different thermoeffectors for maintaining Tb, are still pending questions for birds.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by All procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the National Animal Experimentation Control Council (CONCEA-Brazil) and with the approval of the local Animal Care and Use Committee (CEUA-FCAV-UNESP-Jaboticabal).

Conception and designed experiments: CC-S, LA-S, and KB. Conducted experiments: CC-S, LA-S, KS, WS, MF, and GC. Analyzed and interpreted data: CC-S, LA-S, MA, LG, GS, and KB. Wrote the manuscript: CC-S, LA-S, MA, LG, GS, and KB. Edited and revised the manuscript: CC-S, LA-S, MA, WS, MF, LG, GS, and KB.

This work was financially supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP: Grants 15/04849-6 and 17/12627-9 to KB; Grant 2015/02991-0 to MA) and CAPES PrInt (Finance Code 001, Process: 88887.194785/2018-00). CC-S and LA-S were recipient of FAPESP Ph.D. Fellowships (respectively, 2017/17278-2 and 2017/00864-6). GC and KS were recipient of a Masters (CAPES-Brazil, Joint Graduate Program in Physiological Sciences—PIPGCF-UFSCar/UNESP) and a Ph.D. fellowship (CAPES-Brazil, Graduate Program in Animal Science—UNESP-Jaboticabal). WS was supported by FAPESP (TT3 fellowship 2018/01796-7 and 2019/06211-0).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

CC-S and LA-S were recipients of the FAPESP Ph.D. fellowships 2017/17278-2 and 2017/00864-6 respectively associated to the Joint Graduate Program in Physiological Sciences- PIPGCF, UFSCar/UNESP, Brazil, and the Animal Science Graduate Program, FCAV-UNESP, Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil. WS was recipient of a training TT3-FAPESP fellowship (2018/01796-7 and 2019/06211-0). We thank Euclides Roberto Secato for his excellent technical assistance and the veterinarians Virginia Tessarine Barbosa and Rafael Akira Sato for their assistance with anesthesia and surgery in adult chickens.

A, wave amplitude; CNS, central nervous system; f, respiratory rate; FeO2, excurrent fractional concentration of oxygen; FiO2, incurrent fractional concentration of oxygen; FRe, excurrent flow rate; PB, barometric pressure; PbH2O, water vapor pressure of the air inside the animal’s body; Pcal, calibration pressure; PcH2O, water vapor pressure in the chamber; POA, preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus; RQ, respiratory quotient; STPD, standard conditions of temperature, pressure and dry air; Ta, ambient temperature; Tb, body temperature; Tch, temperature inside the respirometry chamber; TRPA, transient receptor potential ankyrin; TRPC, transient receptor protein channel; TRPM, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M (melastatin); TRPV, transient receptor potential vanilloid; Ts, surface temperature; Vcal, calibration volume;

Alberts J. R. (1978). Huddling by Rat Pups: Group Behavioral Mechanisms of Temperature Regulation and Energy Conservation. J. Comp. Physiological Psychol. 92, 231–245. doi:10.1037/h0077459

Almeida M. C., Hew-Butler T., Soriano R. N., Rao S., Wang W., Wang J., et al. (2012). Pharmacological Blockade of the Cold Receptor TRPM8 Attenuates Autonomic and Behavioral Cold Defenses and Decreases Deep Body Temperature. J. Neurosci. 32, 2086–2099. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5606-11.2012

Amaral-Silva L. d., Gargaglioni L. H., Steiner A. A., Oliveira M. T., Bícego K. C. (2021). Regulated Hypothermia in Response to Endotoxin in Birds. J. Physiol. 599, 2969–2986. doi:10.1113/JP281385

Amaral-Silva L., Tazawa H., Bicego K. C., Burggren W. W. (2020). Metabolic and Hematological Responses to Endotoxin-Induced Inflammation in Chicks Experiencing Embryonic TCDD Exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 39, 2208–2220.

Amaral-Silva L., da Silva W. C., Gargaglioni L. H., Bícego K. C. (2022). Metabolic Trade-Offs Favor Regulated Hypothermia and Inhibit Fever in Immune-Challenged Chicks. J. Exp. Biol. 225. jeb243115, doi:10.1242/jeb.243115

Arad Z., Marder J. (1982). Comparative Thermoregulation of Four Breeds of Fowls (Callus Domesticus), Exposed to a Gradual Increase of Ambient Temperatures. Comp. Biochem. Physiology Part A Physiology 72, 179–184. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(82)90029-9

Bicego K. C., Barros R. C. H., Branco L. G. S. (2007). Physiology of Temperature Regulation: Comparative Aspects. Comp. Biochem. Physiology Part A Mol. Integr. Physiology 147, 616–639. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.06.032

Cabo R., Galvez A., Laura R., San José I., Pastor J. F., López-Muñiz A., et al. (2013). Immunohistochemical Detection of the Putative Mechanoproteins ASIC2 and TRPV4 in Avian Herbst Sensory Corpuscles. Anat. Rec. 296, 117–122. doi:10.1002/ar.22615

Cheung M., Bao W., Behm D. J., Brooks C. A., Bury M. J., Dowdell S. E., et al. (2017). Discovery of GSK2193874: An Orally Active, Potent, and Selective Blocker of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 8, 549–554. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00094

Chuang H.-h., Neuhausser W. M., Julius D. (2004). The Super-cooling Agent Icilin Reveals a Mechanism of Coincidence Detection by a Temperature-Sensitive TRP Channel. Neuron 43, 859–869. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.038

Clapham D. E. (2003). TRP Channels as Cellular Sensors. Nature 426, 517–524. doi:10.1038/nature02196

Coleone A. C., Torres K. A. A., Carnio E. C., Gargaglioni L. H., Macari M., Furlan R. L., et al. (2009). Role of Brain Nitric Oxide in the Thermoregulation of Broiler Chicks. Comp. Biochem. Physiology Part A Mol. Integr. Physiology 154, 204–210. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.005

Cristina-Silva C., Gargaglioni L. H., Bícego K. C. (2021). A Thermoregulatory Role for the Medullary Raphe in Birds. J. Exp. Biol. 224, 1–45. doi:10.1242/jeb.234344

Drorbaug J. E., Fenn W. O. (1955). A Barometric Method for Measuring Ventilation in Newborn Infants. Pediatrics 16, 81–87. doi:10.1542/peds.16.1.81

Dantonio V., Batalhão M. E., Fernandes M. H. M. R., Komegae E. N., Buqui G. A., Lopes N. P., et al. (2016). Nitric Oxide and Fever: Immune-to-Brain Signaling vs. Thermogenesis in Chicks. Pediatrics. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00453.2015

Everaerts W., Zhen X., Ghosh D., Vriens J., Gevaert T., Gilbert J. P., et al. (2010). Inhibition of the Cation Channel TRPV4 Improves Bladder Function in Mice and Rats with Cyclophosphamide-Induced Cystitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19084–19089. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005333107

Fujii N., Kenny G. P., Amano T., Honda Y., Kondo N., Nishiyasu T. (2019). Evidence for TRPV4 Channel Induced Skin Vasodilatation through NOS, COX, and KCa Channel Mechanisms with No Effect on Sweat Rate in Humans. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 858, 172462. doi:10.1016/J.EJPHAR.2019.172462

Fujii N., Kenny G. P., McGarr G. W., Amano T., Honda Y., Kondo N., et al. (2021). TRPV4 Channel Blockade Does Not Modulate Skin Vasodilation and Sweating during Hyperthermia or Cutaneous Postocclusive Reactive and Thermal Hyperemia. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiology 320, R563–R573. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00123.2020

Fusi C., Materazzi S., Minocci D., Maio V., Oranges T., Massi D., et al. (2014). Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) Is Downregulated in Keratinocytes in Human Non-melanoma Skin Cancer. J. Investigative Dermatology 134, 2408–2417. doi:10.1038/JID.2014.145

Gilbert C., McCafferty D., Le Maho Y., Martrette J.-M., Giroud S., Blanc S., et al. (2010). One for All and All for One: The Energetic Benefits of Huddling in Endotherms. Biol. Rev. 85, 545-69. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00115.x

Güler A. D., Lee H., Iida T., Shimizu I., Tominaga M., Caterina M. (2002). Heat-evoked Activation of the Ion Channel, TRPV4. J. Neurosci. 22, 6408–6414. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.22-15-06408.2002

Hammel H. T., Pierce J. B. (1968). Regulation of Internal Body Temperature. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 30, 641–710. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.30.030168.003233

Hunt R. F., Hortopan G. A., Gillespie A., Baraban S. C. (2012). A Novel Zebrafish Model of Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures Reveals a Role for TRPV4 Channels and NMDA-type Glutamate Receptors. Exp. Neurol. 237, 199–206. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.013

Ishikawa D., Vizin R., Souza C., Carrettiero D., Romanovsky A., Almeida M. (2019). Camphor, Applied Epidermally to the Back, Causes Snout- and Chest-Grooming in Rats: A Response Mediated by Cutaneous TRP Channels. Pharmaceuticals 12, 24. doi:10.3390/PH12010024

Jordt S.-E., Julius D. (2002). Molecular Basis for Species-specific Sensitivity to "Hot" Chili Peppers. Cell 108, 421–430. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00637-2

Kauer J. A., Gibson H. E. (2009). Hot Flash: TRPV Channels in the Brain. Trends Neurosci. 32, 215–224. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.006

Khandoker A. H., Fukazawa K., Dzialowski E. M., Burggren W. W., Tazawa H. (2004). Maturation of the Homeothermic Response of Heart Rate to Altered Ambient Temperature in Developing Chick Hatchlings (Gallus gallus Domesticus). Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiology 286, R129–R137. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00316.2003

Kida N., Sokabe T., Kashio M., Haruna K., Mizuno Y., Suga Y., et al. (2012). Importance of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) in Epidermal Barrier Function in Human Skin Keratinocytes. Pflugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 463, 715–725. doi:10.1007/S00424-012-1081-3

Kleiber M., Winchester C. (1933). Temperature Regulation in Baby Chicks. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 31, 158–159. doi:10.3181/00379727-31-7038P

Kluger M. J., Kozak W., Conn C. A., Leon L. R., Soszynski D. (1996). The Adaptive Value of Fever. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 10, 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70282-8

Koteja P. (1996). Measuring Energy Metabolism with Open-Flow Respirometric Systems: Which Design to Choose? Funct. Ecol. 10, 675. doi:10.2307/2390179

Legendre L. J., Davesne D. (2020). The Evolution of Mechanisms Involved in Vertebrate Endothermy. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190136. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0136

Luo J., Hu H. (2014). Thermally Activated TRPV3 Channels. Curr. Top. Membr. 74, 325–364. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800181-3.00012-9

Mathiu P. M., Dawson W. R., Whittow G. C. (1991). Development of Thermoregulation in Hawaiian Brown Noddies (Anous Stolidus Pileatus). J. Therm. Biol. 16, 317–325. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(91)90057-9

McKechnie A. E., Lovegrove B. G. (2001). Thermoregulation and the Energetic Significance of Clustering Behavior in the White-Backed Mousebird (Colius Colius). Physiological Biochem. Zoology 74, 238–249. doi:10.1086/319669

Morrison S. F. (2016). Central Neural Control of Thermoregulation and Brown Adipose Tissue. Aut. Neurosci. 196, 14–24. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2016.02.010

Mortola J. P., Labbè K. (2005). Oxygen Consumption of the Chicken Embryo: Interaction between Temperature and Oxygenation. Respir. Physiology Neurobiol. 146, 97–106. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2004.10.011

Mortola J. P., Maskrey M. (2011). Metabolism, Temperature, and Ventilation. Compr. Physiol. 1, 1679–1709. doi:10.1002/cphy.c100008

Myers B. R., Sigal Y. M., Julius D. (2009). Evolution of Thermal Response Properties in a Cold-Activated TRP Channel. PLoS One 4, e5741–7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005741

Nawaz A. H., Amoah K., Leng Q. Y., Zheng J. H., Zhang W. L., Zhang L. (2021). Poultry Response to Heat Stress: Its Physiological, Metabolic, and Genetic Implications on Meat Production and Quality Including Strategies to Improve Broiler Production in a Warming World. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 814. doi:10.3389/FVETS.2021.699081/BIBTEX

Nichelmann M., Tzschentke B. (2002). Ontogeny of Thermoregulation in Precocial Birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiology Part A Mol. Integr. Physiology 131, 751–763. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00013-2

Nikami H., Mahmoud M. E., Shimizu Y., Shiina T., Hirayama H., Iwami M., et al. (2008). Capsaicin Pretreatment Attenuates LPS-Induced Hypothermia through TRPV1-independent Mechanisms in Chicken. Life Sci. 82, 1191–1195. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2008.04.003

Olivan-Viguera A., Garcia-Otin A. L., Lozano-Gerona J., Abarca-Lachen E., Garcia-Malinis A. J., Hamilton K. L., et al. (2018). Pharmacological Activation of TRPV4 Produces Immediate Cell Damage and Induction of Apoptosis in Human Melanoma Cells and HaCaT Keratinocytes. PLoS One 13, e0190307. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0190307

De Oliveira R. F. M., Donzele J. L., Abreu M. L. T., Ferreira R. A., Vaz R. G. M. V., Cella P. S. (2006). Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on Performance and Yield of Noble Cuts of Broilers from 1 to 49 Days Old. R. Bras. Zootec. 35, 797–803. doi:10.1590/s1516-35982006000300023

Patapoutian A., Peier A. M., Story G. M., Viswanath V. (2003). ThermoTRP Channels and beyond: Mechanisms of Temperature Sensation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 529–539. doi:10.1038/nrn1141

Peier A. M., Reeve A. J., Andersson D. A., Moqrich A., Earley T. J., Hergarden A. C., et al. (2002). A Heat-Sensitive TRP Channel Expressed in Keratinocytes. Science 296, 2046–2049. doi:10.1126/science.1073140

Richards S. A. (1970). The Role of Hypothalamic Temperature in the Control of Panting in the Chicken Exposed to Heat. J. Physiol. 211, 341–358. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009282

Saito S., Banzawa N., Fukuta N., Saito C. T., Takahashi K., Imagawa T., et al. (2014). Heat and Noxious Chemical Sensor, Chicken TRPA1, as a Target of Bird Repellents and Identification of its Structural Determinants by Multispecies Functional Comparison. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 708–722. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu001

Saito S., Shingai R. (2006). Evolution of thermoTRP Ion Channel Homologs in Vertebrates. Physiol. Genomics 27, 219–230. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00322.2005

Scarpellini C. d. S., Cristina-Silva C., Biancardi V., Gargaglioni L. H., Almeida M. C., Bícego K. C. (2019). Hypothalamic TRPV4 Channels Participate in the Medial Preoptic Activation of Warmth-Defence Responses in Wistar Male Rats. Pflugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 471, 1191–1203. doi:10.1007/s00424-019-02303-1

Shibasaki K., Sugio S., Takao K., Yamanaka A., Miyakawa T., Tominaga M., et al. (2015). TRPV4 Activation at the Physiological Temperature is a Critical Determinant of Neuronal Excitability and Behavior. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 467, 2495–2507. doi:10.1007/s00424-015-1726-0

Tazawa H., Chiba Y., Khandoker A. H., Dzialowski E. M., Burggren W. W. (2004).Early Development of Thermoregulatory Competence in Chickens: Responses of Heart Rate and Oxygen Uptake to Altered Ambient Temperatures, Avian Poul. Biolog. Rev., 15, 166–176. doi:10.3184/147020604783638056

Telliez F., Bach V., Krim G., Libert J.-P. (1997). Consequences of a Small Decrease of Air Temperature from Thermal Equilibrium on Thermoregulation in Sleeping Neonates. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 35, 516–520. doi:10.1007/BF02525533

Toro-Velasquez P. A., Bícego K. C., Mortola J. P. (2014). Chicken Hatchlings Prefer Ambient Temperatures Lower Than Their Thermoneutral Zone. Comp. Biochem. Physiology Part A Mol. Integr. Physiology 176, 13–19. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.06.008

Vincent F., Acevedo A., Nguyen M. T., Dourado M., DeFalco J., Gustafson A., et al. (2009). Identification and Characterization of Novel TRPV4 Modulators. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 389, 490–494. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.007

Vizin R. C. L., Scarpellini C. d. S., Ishikawa D. T., Correa G. M., de Souza C. O., Gargaglioni L. H., et al. (2015). TRPV4 Activates Autonomic and Behavioural Warmth-Defence Responses in Wistar Rats. Acta Physiol. 214, 275–289. doi:10.1111/apha.12477

Wang H., Siemens J. (2015). TRP Ion Channels in Thermosensation, Thermoregulation and Metabolism. Temperature 2, 178–187. doi:10.1080/23328940.2015.1040604

Watanabe H., Vriens J., Suh S. H., Benham C. D., Droogmans G., Nilius B. (2002). Heat-evoked Activation of TRPV4 Channels in a HEK293 Cell Expression System and in Native Mouse Aorta Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (49), 47044–47051. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208277200

Wolfenson D., Frei Y. F., Snapir N., Berman A. (1981). Heat Stress Effects on Capillary Blood Flow and its Redistribution in the Laying Hen. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 390, 86–93. doi:10.1007/BF00582717

Keywords: peripheral thermoreceptor, chicken, thermoregulation, Metabolism, body temperature, thermolysis, huddling

Citation: Cristina-Silva C, Amaral-Silva L, Santos KM, Correa GM, da Silva WC, Fernandes MHMR, da Silva GSF, Gargaglioni LH, Almeida MC and Bicego KC (2022) Cutaneous TRPV4 Channels Activate Warmth-Defense Responses in Young and Adult Birds. Front. Physiol. 13:892828. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.892828

Received: 09 March 2022; Accepted: 14 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Huseyin Cagatay Yalcin, Qatar University, QatarReviewed by:

Shaun F. Morrison, Oregon Health and Science University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Cristina-Silva, Amaral-Silva, Santos, Correa, da Silva, Fernandes, da Silva, Gargaglioni, Almeida and Bicego. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kenia C. Bicego, a2VuaWFjYkB5YWhvby5jb20uYnI=, ay5iaWNlZ29AdW5lc3AuYnI=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.