94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Physiol., 11 April 2022

Sec. Integrative Physiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.888324

This article is part of the Research TopicInsights in Integrative Physiology: 2021View all 27 articles

Xue-Ying Zhang1

Xue-Ying Zhang1 De-Hua Wang1,2,3*

De-Hua Wang1,2,3*The endotherms, particularly the small mammals living in the polar region and temperate zone, are faced with extreme challenges for maintaining stable core body temperatures in harsh cold winter. The non-hibernating small mammals increase metabolic rate including obligatory thermogenesis (basal/resting metabolic rate, BMR/RMR) and regulatory thermogenesis (mainly nonshivering thermogenesis, NST, in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle) to maintain thermal homeostasis in cold conditions. A substantial amount of evidence indicates that the symbiotic gut microbiota are sensitive to air temperature, and play an important function in cold-induced thermoregulation, via bacterial metabolites and byproducts such as short-chain fatty acids and secondary bile acids. Cold signal is sensed by specific thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels (thermo-TRPs), and then norepinephrine (NE) is released from sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and thyroid hormones also increase to induce NST. Meanwhile, these neurotransmitters and hormones can regulate the diversity and compositions of the gut microbiota. Therefore, cold-induced NST is controlled by both Thermo-TRPs—SNS—gut microbiota axis and thyroid—gut microbiota axis. Besides physiological thermoregulation, small mammals also rely on behavioral regulation, such as huddling and coprophagy, to maintain energy and thermal homeostasis, and the gut microbial community is involved in these processes. The present review summarized the recent progress in the gut microbiota and host physiological and behavioral thermoregulation in small mammals for better understanding the evolution and adaption of holobionts (host and symbiotic microorganism). The coevolution of host-microorganism symbionts promotes individual survival, population maintenance, and species coexistence in the ecosystems with complicated, variable environments.

The endotherms regulate thermogenesis and/or heat dissipation to maintain relatively high, stable core body temperatures (Tb, around 37°C in many species) in the fluctuating environments. Small mammals living in the polar region and temperate zone, due to with high ratios of body surface area to volume, are faced with extreme challenges in harsh winter with the characteristics of low temperatures and food shortage. During evolution, these mammals have developed multiple strategies, by adjusting morphological, physiological, and behavioral phenotypes, to adapt to variable environments, especially fluctuations of air temperatures (Ta). A crucial physiological strategy for small mammals to cope with Ta fluctuations is changing metabolic rate for survival during seasonal acclimatization.

Some mammalian species are able to decrease metabolic rate and Tb, and enter torpor (such as Phodopus sungorus and P. rovorovskii) or hibernation (such as Spermophilus dauricus) to save energy and survive in winter (McNab, 2002; Chi et al., 2016; Ren et al., 2022). However, the non-hibernating small mammals (e.g., Lasiopodomys brandtii and Meriones unguiculatus) must increase metabolic rate including obligatory thermogenesis (basal/resting metabolic rate, BMR/RMR, with a difference of fasting for the former and no fasting for the latter before measurement) in the liver and other metabolic organs, and regulatory thermogenesis (mainly nonshivering thermogenesis, NST) in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and skeletal muscle to maintain thermal homeostasis in winter or during cold acclimation (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004; Zhang and Wang, 2006; Nowack et al., 2017; Bal et al., 2018). Both the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and thyroid hormones are required for regulating thermogenesis and Tb (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004; Mullur et al., 2014). These non-hibernating mammals need consume more food to compensate for the high energy expenditure due to cold-induced thermogenesis (Zhang and Wang, 2006). In fact, food resource is not available all the time and is even of severe shortage in wild winter. Therefore, these small mammals have also evolved behavioral strategies, for example huddling and coprophagy, to decrease energy expenditure and increase energy harvest.

In addition to the physiological and behavioral strategies of the rodents themselves, a myriad of evidence indicates that the complex communities of symbiotic microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract of animals can largely affect host phenotypes and fitness, such as energy metabolism, thermogenesis, immune function, endocrine activity and neuronal functions (Fetissov, 2017; Rastelli et al., 2019). This microbial community is specific to each host individual in spite of the existence of multiple bacterial taxa shared by the majority of hosts. The gut microbiota can degrade dietary fiber (nondigestible carbohydrates) into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs, mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate) and vitamins, and also contribute to metabolizing primary bile acids into secondary bile acids (SBAs) by enhancing deconjugation, dehydrogenation, and dehydroxylation via bacterial enzymes (Ridlon et al., 2006; Rastelli et al., 2019). It is verified that both SCFAs and SBAs are involved in stimulating gut hormone secretion and regulating appetite and thermogenesis. These metabolites and byproducts of microbiota can also directly interact with the enteric nervous system (ENS) and provide a link between the gut microbiota and host physiology and behavior (Worthmann et al., 2017). The experiments of gut microbiota transplant revealed that alteration in the gut microbiota induced variations in host phenotypes, further suggesting that the specific gut microbes are of importance for host fitness (Gould et al., 2018). Moreover, microbial communities codiversified with their host species, implying coevolution between the gut microbiota and their hosts (Ley et al., 2008; Groussin et al., 2017). Therefore, the evolution theory of host-microorganism symbioses assumes that microbial colonization in the mammalian intestinal tracts should be an evolution-driven process benefiting fitness of both sides. In this review, we summarize recent evidence about the physiological and behavioral strategies for maintaining Tb in response to changing Ta and the functions of the gut microbiota in host thermoregulation in small mammals for better understanding the evolution and adaption of holobionts.

Environmental cues play crucial roles in affecting animal’s physiological and behavioral plasticity. Among these cues, Ta, due to its seasonal, daily and sometimes irregular fluctuations, is remarkable in affecting thermogenesis, energy balance and survival in small mammals living in the arctic and temperate regions. Small mammals change metabolic rate in response to Ta fluctuations. The metabolic rate, measured in the resting, awake, and postabsorptive state and named as the BMR, is kept at a constant, minimal level within a specific temperature range, which is defined as the thermoneutral zone (TNZ) (Gordon, 2012). The idea of a thermoneutral “zone” has been questioned and a thermoneutral point (TNP) was proposed, blow which metabolic rates increase and above which Tb increases based on studies in mice (Škop et al., 2020). In wide rodents such as Mongolian gerbils, there is a temperature range within which both RMR and Tb were kept relatively stable (Pan et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2018). Energy expenditure (oxygen consumption) increases, due to cold-induced thermogenesis at Ta below the TNZ, and due to a Q10 effect (Mikane et al., 1999) or cooling mechanisms related with water balance and osmotic regulation at Ta above the TNZ (Kasza et al., 2019). Since thermal constraints across geographic gradients, each mammal species has formed species-specific TNZ, which may reflect the differences in the thermal biology among species (Bozinovic et al., 2014).

In eutherian mammals, BAT, has evolved as a specialized thermogenic organ and confers mammals an evolutionary consequence to survive the cold stress (Oelkrug et al., 2015). BAT depots are predominantly located in the intrascapular, dorso-cervical, subscapular and axillary regions, and sporadically in the pericardial and perirenal regions in rodents (Smith and Roberts, 1964; Symonds et al., 2015). The adipocytes in BAT contain dense mitochondria for high oxidative capacity and energy production, and dense vascularization helpful to transport nutrient and heat, as well as multilocular fat droplets to be mobilized into free fatty acids as fuel rapidly (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). Cold-induced BAT thermogenesis is mediated through stimulation of β3-adrenergic receptors (β3-AR)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) signaling and activation of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). UCP1 is almost exclusively located in the inner mitochondrial membrane of brown adipocytes, and plays the function of uncoupling the proton motive force from ATP production and dissipating the electrochemical energy as heat (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). It was observed that BAT mass, mitochondrial protein content, cytochrome c oxidase (COX) activity and UCP1 expression increased, during cold exposure or cold acclimation in non-hibernating small mammals, such as in Brandt’s voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii), Mongolian gerbils root voles (Microtus oeconomus) and plateau pikas (Ochotona curzoniae) (Wang et al., 2006; Zhang and Wang, 2006; Li and Wang, 2007). Cold-induced increases in sympathetic activation and UCP1 expression (browning) in white adipose tissue (WAT) can also help animals defense cold and maintain Tb (Bai et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2017). Our previous data confirmed that cold-induced phenotypic variations were initiated by increased release of norepinephrine (NE) and activation of cAMP-PKA-pCREB signaling pathway in BAT (Bo et al., 2019). Cold-induced lipolysis (catabolism of triglycerides) and glucose uptake via glucose transporter (GLUT4) in adipocytes provides the availability of free fatty acids and glucose as the sources of fuel for BAT thermogenesis (Townsend and Tseng, 2014; Garretson et al., 2016). Therefore, BAT plays its roles in regulating thermogenesis, and fatty acid and glucose metabolism.

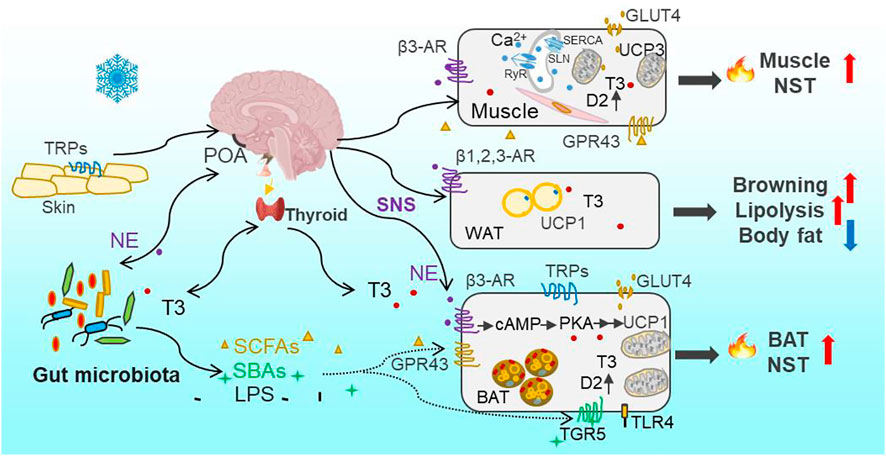

Besides BAT-dependent thermogenesis in eutherian mammals, increasing evidence has shown that skeletal muscle also contributes importantly to cold-induced adaptive thermogenesis, independent of shivering or contraction (Nowack et al., 2017; Bal et al., 2018; Bal and Periasamy, 2020). The role of skeletal muscle NST is particually crucial in several specific endothms, such as birds, monotremes, marsupials, and wild boars, which lack BAT (Rowland et al., 2015). Lineage tracing studies have revealed that skeletal muscle and BAT arive from the same precursor cells in the dermomyotome expressing Pax3/7 (the transcription factor) and myogenic factor 5 (Myf5, the determination factor) (Lang et al., 2005; Sgaier et al., 2005), whereas the precursor for mature white adipocytes lacks Myf5 expression (Sanchez-Gurmaches et al., 2012). Moreover, recent evolutionary studies imply that NST in skeletal muscle originated much earlier than BAT-driven thermogenesis in vertebrates (Rowland et al., 2015; Grigg et al., 2022). The mechanism for muscle NST is based on activities of sarcoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated Ca2+-leak and sarcolipin (SLN)-activated sarcoplasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) (Figure 1) (Periasamy and Huke, 2001; Zima et al., 2010; Bal et al., 2012; Chambers et al., 2022). SLN, via binding to SERCA, uncouples ATP hydrolysis from Ca2+ transportation and as a result increases heat production (Smith et al., 2002; Bal et al., 2012). In addition, the activation of mitochondrial UCP3 by intracellular levels of Ca2+ and fatty acids is also associated with muscle NST (Costford et al., 2007). Small mammals depend on increasing the adaptive thermogenesis deriving from BAT and skeletal muscle to maintain Tb relatively stable and survive in harsh winter.

FIGURE 1. Overview of cold-induced thermogenesis through Thermo-TRPs—SNS—gut microbiota—thermogenesis axis and thyroid—gut microbiota—thermogenesis axis. Cold is sensed by the thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels (Thermo-TRPs) on the skin and in the brain and other organs. Cold signal is transmitted through the sensory afferent nerve to the preoptic area (POA) in the hypothalamus and other thermoeffector efferent circuits, and leads to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to release norepinephrine (NE) and stimulate mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) through β3 adrenergic receptors (β3-AR) and activation of PKA signaling pathway in brown adipose tissue (BAT). In parallel with the direct effect of NE on thermogenesis, the gut microbiota community is reconstructed through sensing cold signal or neuroactive signal of NE and, consequently, leads to increases in bacterial metabolites (short-chain fatty acids, SCFAs) and byproducts (secondary bile acids, SBAs). Both SCFAs and SBAs, via acting on their respective G protein-coupled receptors GPR43 and TGR5, can stimulate BAT nonshivering thermogenesis (NST). Moreover, the circulating bioactive tri-iodothyronine (T3) level increases after the brain receives cold signal, and promotes obligatory (basal metabolic rate, BMR) and regulatory thermogenesis. T3-induced thermogenesis is also mediated by bacterial metabolites (SCFAs) and byproducts (such as SBAs and lipopolysaccharides, LPS). The binding of SBAs-TGR5 or LPS-TLR4 (Toll-like receptor 4) can activate UCP1 expression in BAT, and stimulate local type 2 deiodinase (D2) to induce the conversion from the prohormone thyroxine (T4) to bioactive T3 as well. The binding of NE with β1,2,3-AR in white adipose tissue (WAT) activates lipolysis (catabolism of triglycerides) into free fatty acids as one source of fuel for BAT thermogenesis, leading to the decrease in body fat content. Cold-induced glucose uptake via glucose transporter (GLUT4) in adipocytes and muscle can also provide glucose as fuel for BAT and muscle thermogenesis. Muscle NST is mainly based on activities of sarcoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated Ca2+-leak, sarcolipin (SLN)-activated sarcoplasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), and mitochondrial UCP3 as well. SLN, via binding to SERCA, can uncouple ATP hydrolysis from Ca2+ transportation and as a result increase heat production.

Cold signal is sensed by a group of cold-sensitive thermoreceptors, the thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels (Thermo-TRPs), such as TRPA1 (<17°C) and TRPM8 (10–26°C), on the skin and in muscle, viscera, spine and brain, and transmitted through the sensory afferent nerve to the preoptic area (POA) in the hypothalamus and other thermoeffector efferent circuits (Morrison and Nakamura, 2019). There are also warm-sensitive thermoreceptors, such as TRPM2 (>42°C), TRPV1 (>42°C) and TRPV2 (>52°C) on the skin and body core (Hoffstaetter et al., 2018). These TRPs are activated by high Ta and transfer thermal signal to the central relevant thermoregulatory network and, consequently, lead to BAT atrophy and heat dissipation (Vandewauw et al., 2018). A rescent study identified the expression of TRPV1 as a specific characteristic of vascular smooth muscle (VSM)-derived adipocyte progenitor cells and the contribution of these cells to cold-induced BAT recruitment (Shamsi et al., 2021). TRPV1 is also involved in temperature preference behavior-associated thermoregulation in Mongolian gerbils (Wen et al., 2021). TRPs have been widely studied for cold or warm sensation in specific TRP knock-out laboratory models (Peier et al., 2002; Vandewauw et al., 2018), but the responses of TRPs to Tas are diversified in wild mammal species and in diverse tissues. For example, during cold acclimation, the expression of TRPM8 in small intestine increased in mice (Wen et al., 2020), and TRPA1 and TRPV2 in BAT increased in Brandt’s voles, whereas TRPM2 decreased in Mongolian gerbils (unpublished data). TRPs can also be activated by ligands, such as capsaicin, menthol and bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides, LPS) (Peier et al., 2002; Baskaran et al., 2016; Boonen et al., 2018). Therefore, the functions of diverse TRPs should be widely investigated for better understanding how small mammals sense and tolerate extreme Ta particularly under the ecological contexts of heat waves and extremely cold weather.

Besides the central mechanism of thermoregulation, the peripheral gut microbial community is also involved in the regulation of host metabolic and thermal homeostasis. Several wild studies indicate that gut microbes vary with seasons, altitudes and geographies in small mammals (Maurice et al., 2015; Perofsky et al., 2019). The environmental factors such as diets, Ta and photoperiod influence the gut microbial community (Martinez-Mota et al., 2019; Suzuki et al., 2019; Khakisahneh et al., 2020). Our previous data identified that low Ta can directly drive gut microbial community assembly rather than cold-induced feeding effect, and intermittent fluctuations of low and high Ta altered the diversity and composition of gut microbiota (Bo et al., 2019; Khakisahneh et al., 2020). Cold-induced alteration in microbes induced increases in NE concentrations both in the intestine and BAT, and also increases in concentrations of bacterial metabolites and byproducts, such as SCFAs and SBAs in feces and blood (Worthmann et al., 2017; Bo et al., 2019). Consequently, these metabolites and byproducts, via their respective G protein-coupled receptors (such as GPR43/41, also named FFAR2/3) and the Takeda GPR (TGR5), promote host’s adaptive thermogenesis both in BAT and skeletal muscle (Figure 1). Besides, the increase in NE production could conversely induce reshaping of the gut microbial community, which was verified by pharmacological NE manipulation (Bo et al., 2019). In addition, early evidence has shown that both the microbiota and their hosts produce the same neuroactive compounds (such as pheromones, hormones and neuropeptides) and the receptors, which enable bidirectional communications between the hosts and symbiotic microorganisms (Roth et al., 1982; Lyte, 2014). Therefore, the interaction between host neurotransmitters and gut microbes contributes to host thermoregulation and thermal homeostasis under the changing environments. Cumulatively, available experimental data suggest that the disturbance of gut microbial community may be a mechanism by which changing global temperatures are imposing impacts on fitness of animals in wild-living populations.

Thyroid hormones, particularly the bioactive tri-iodothyronine (T3), have important roles in regulating developmental and metabolic processes (Mullur et al., 2014; Ortiga-Carvalho et al., 2014). The intracellular T3 in tissues and serum T3 are generally derived from the prohormone thyroxine (T4) through the catalytic action of type 2 deiodinase (D2). D2 is highly expressed in the brain, pituitary, and peripheral tissues such as BAT and skeletal muscle (Brent, 2012; Mullur et al., 2014). When bound to the nuclear receptors (α and β) of thyroid hormones, T3 can regulate multiple transcriptional expressions such as adipose triglyceride lipase (Atg5), COX, UCP1 and GLUT4 responsible for fatty acid oxidation, heat production and glucose uptake in BAT (Mullur et al., 2014; Yau et al., 2019). In muscle, T3 can also modulate the expression of GLUT4, SERCA and UCP3 (Solanes et al., 2005; Salvatore et al., 2014). Thyroid hormones are tightly controlled and maintained within a narrow range of circulating levels by a negative feedback mechanism involving hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone (the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, HPA axis) (Ortiga-Carvalho et al., 2014).

The external environment cues induce changes in internal hormones such as thyroid hormones, leptin (adipocytokine) and secretin (gut hormone), which can act as regulators for metabolism and thermogenesis (Zhang and Wang, 2006; Zhao and Wang, 2006; Li and Wang, 2007; Li et al., 2018; Khakisahneh et al., 2019). The circulating T3 and/or T3/T4 levels increased in winter and during low Ta or short-day acclimations in many mammal species such as in Brandt’s voles, Mongolian gerbils, Daurian ground squirrels (Spermophilus dauricus), and plateau pikas (Li et al., 2001). Cold-induced increased levels of serum T3 promote obligatory (BMR) and regulatory thermogenesis (rNST) by stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis, generating and maintaining ion gradients, increasing ATP production, and increasing the expression of uncoupling proteins (UCPs) in liver, muscle and BAT (Mullur et al., 2014; Shu et al., 2017). Additionally, UCP1-independent thyroid thermogenesis was established in UCP1-ablated mice (Dittner et al., 2019), implying the compensatory role of skeletal muscle thermogenesis for cold defense in small mammals.

In addition to the direct effect of T3 on metabolism and thermogenesis, thyroid function is closely related to the homeostasis of intestinal microbial community. The pathologically, chemically or surgically induced thyroid dysfunction (such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism) was associated with alterations in the diversity and composition of gut microbiota (Khakisahneh et al., 2022; Shin et al., 2020). For example, hyperthyroidism in human was followed by enrichments in gut pathogenic bacteria such as Clostridium and Enterobacteriaceae (Zhou et al., 2014). And the hyperthyroid gerbils exhibited increased abundances of pathogenic Helicobacter and Rikenella, and decreased abundances of beneficial Butyricimonas and Parabacteroides (Khakisahneh et al., 2022). Moreover, the previous data verified that microbiota transplant from normal donors to hyperthyroidism could buffer hyperthyroid-induced disorders in the microbial community and thermogenesis (Khakisahneh et al., 2022). Gut microbes through activation of D2 in the intestine and liver improve the conversion of bioactive T3 from inactive T4, thereby modulating local T3 levels and intestinal homeostasis (Kojima et al., 2019). The gut microbiota-derived SBAs can also activate D2 activity through TGR5 and increase cold-induced thermogenesis (Figure 1) (Watanabe et al., 2006; Worthmann et al., 2017). Moreover, bacterial LPS through binding Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) can stimulate T3 conversion by promoting D2 mRNA accumulation and enzyme activity in mouse mediobasal hypothalamus and rat astrocytes (Boelen et al., 2004; Lamirand et al., 2011). Collectively, the gut microbiota can sense hormones, and regulate thyroid hormone recycling and metabolism through bacterial metabolites and byproducts to modulate deiodinase activity (Virili and Centanni, 2015; Virili and Centanni, 2017; Lopes and Sourjik, 2018). Small mammals maintain metabolic and thermal homeostasis through the bidirectional communication between the thyroid and gut microbiota.

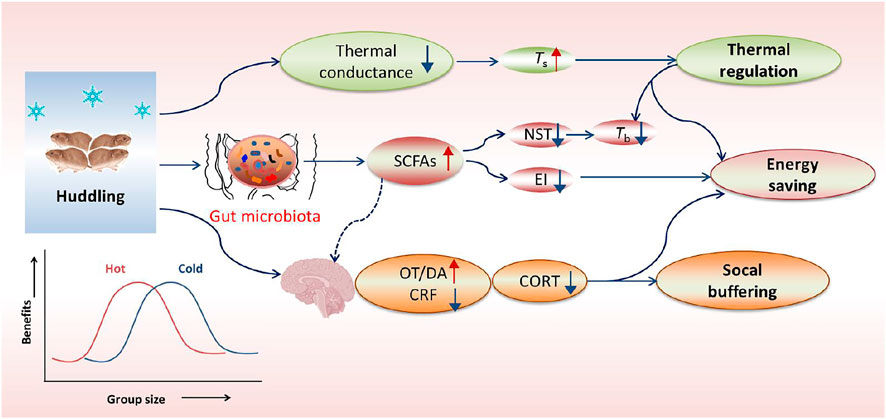

The group-living (gregarious or social) mammals have evolved cooperative (or social) behavior to optimize their fitness to survive in harsh environments. Huddling behavior is one type of highly-conserved cooperative behavioral strategies for social species to reduce thermoregulatory costs as well as predation risk (Ebensperger, 2001; Haig, 2008; Gilbert et al., 2010). In cold conditions, the gregarious rodents huddle together to reduce thermal conductance, and decrease NST and food intake, and as a consequence show an increased body surface temperature (Ts), but a reduced Tb (Figure 2), whereas the solitary species or non-huddling individuals increase thermogenesis to maintain Tb or entering hibernation to reduce temperature difference between the body and air (Nowack and Geiser, 2016; Sukhchuluun et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). The energetic benefit of huddling depends on group sizes and Ta in a reversed U-shaped form (Figure 2), and the optimal group size for energy saving varies with different temperatures (Gilbert et al., 2010). Increasing group size over the optimal size has little additional advantage to reduce energy metabolism, but indeed increases resource competition and disease risks among individuals (Gilbert et al., 2010; Škop et al., 2021). In addition, the benefit and intensity of huddling increase as Ta reduces, and decrease at high Ta and within TNZ (Gilbert et al., 2010). In conclusion, huddling is an active, complex social thermoregulation behavior, particularly beneficial for energy conservation for social species living in winter or exposing to low Ta.

FIGURE 2. Overview of huddling-related benefits in thermoregulation, energy saving and social buffering. In cold, the gregarious (social) rodents huddle together to reduce body surface area and thus decrease thermal conductance, but can keep a relatively high body surface temperature (Ts) and a low core body temperature (Tb). The social environment can facilitate gut microbial community with more beneficial bacteria and their metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), thereby inducing decreases in nonshivering thermogenesis (NST) and energy intake (EI). Additionally, social environments particularly social bonding or attachment can also buffer stress responses, which is mediated by increased neurotransmitters such as dopamine (DA) and oxytocin (OT), but reduced corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the limbic system and hypothalamus. The energetic benefit of huddling is dependent on group size and ambient temperatures (Ta), and it indicates a reversed U-shaped form, with an optimal group size for energy saving and other benefits.

Social environment (or sociability) can buffer stress responses and facilitate the gut microbial community. For example, social bonding or attachment in the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) reduces stress hormone corticosterone (CORT) and confers social buffering benefit, which is mediated by increased neurotransmitters such as dopamine (DA) and oxytocin (OT), but reduced corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the limbic system and hypothalamus (Figure 2) (Smith and Wang, 2014; Burkett et al., 2016). Our previous data in Brandt’s voles showed that huddling animals had a healthier gut microbial community with more SCFAs-producing bacteria in comparison with non-huddling voles, indicating the energy-saving benefit of huddling is mediated by improving microbial homeostasis (Figure 2) (Zhang et al., 2018). Social status also shaped the diverse microbial community between dominants and subordinates in mice and Tscherskia triton (Zhao et al., 2020; Agranyoni et al., 2021). Whether gut microbial community mediates sociability-induced physiological and behavioral differences was validated by fecal/caecal microbiota transplant (FMT/CMT) using antibiotics-treated or germ-free mice or wild rodents. The mice with absence of gut microbiota elevated the level of corticosterone (the stress hormone) and displayed social behavioral deficits during the assessment of reciprocal social interactions (Buffington et al., 2016). In addition, normal microbiota colonization (co-housing or oral gavage) could effectively correct social impairments of the mice lacking the gut microbiota (Buffington et al., 2016; Chu et al., 2019). More importantly, a specific bacterial species, Enterococcus faecalis, has been identified to restrain stress responses and promote social activity in the mice following social stress (Wu et al., 2021). These substantial data support crucial functions of the gut microbiota in regulating sociability-related behavioral divergence and fitness benefits.

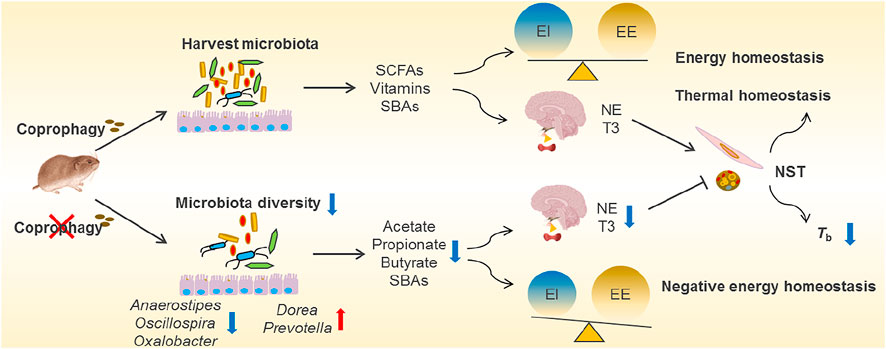

Coprophagy is the behavior of eating feces to help establish the intestinal microbiota, and to acquire protein and micronutrients, which is common in lagomorphs, rodents and other species (Soave and Brand, 1991). The term caecotrophy refers specially to soft faeces ingestion practiced by rabbits and small herbivores (small hindgut fermenters) (Hoernicke, 1981). The proximal colonic separation mechanism observed in many small herbivores can allow for retrograde fluid transport of digesta including bacteria from the proximal colon back into the caecum (Pei et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2007; Hagen et al., 2016). The accumulation of microorganisms in the caecum contributes to a high fermentation rate for bacterial synthesis of nutrients (Karasov et al., 2011). The high-fiber diets promote digesta retention time and production of more soft feces, and coprophagy increases in the periods with a higher energy demand, such as during pregnancy and lactation (Ebino et al., 1988; Hejcmanová et al., 2020). In many studies in rodents such as rats, mice, L. brandtii and Microtus fortis, prevention of coprophagy decreased body weight, and RMR and NST, suggesting that coprophagy contributes to energy balance and thermoregulation (Sukemori et al., 2003; Sassi et al., 2010; Kohl et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Bo et al., 2020). The energetic and thermal benefits of interspecific coprophagy for survival were observed in plateau pikas that eat yak feces to supplement energy intake in winter (Speakman et al., 2021). Besides, coprophagy in the voles increases neurotransmitters in the hypothalamus and hippocampus, and promotes cognitive performance (Bo et al., 2020). These data indicate that consumption of enough soft feces for herbivorous rodents is necessary to provide enough amounts of nutrients and energy for growth, thermoregulation, and neurodevelopment as well (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Overview of coprophagy-associated benefits in harvesting intestinal microbiota and maintaining energy and thermal homeostasis. Coprophagy prevention (CP) leads to loss of beneficial bacteria such as Anaerostipes, Oscillospira and Oxalobacter for production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate and butyrate), vitamins and secondary bile acids (SBAs), and results in the negative energy homeostasis (imbalance between energy intake, EI, and energy expenditure, EE). The deficiency in energy supply to the brain impairs the neuroendocrinology and leads to decreases in norepinephrine (NE) and tri-iodothyronine (T3) in CP animals, consequently leading to decreases in nonshivering thermogenesis (NST) in BAT and muscle and a drop in core body temperatures (Tb).

Supplement of nutrients and energy via coprophagy may be through harvesting the gut microbiota (self-inoculation). Prevention of coprophagy in Brand’s voles reduced α diversity of gut microbial community and altered the composition of the gut microbiota, particularly decreased relative abundance of Firmicutes, including the families of Clostridiaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, which all belong to highly cellulolytic bacteria (Bo et al., 2020). Accompanied by the reduced diversity of gut microbial community, coprophagy prevention also decreased the concentrations of bacterial metabolites, such as acetate, propionate and butyrate (Figure 3). Both the microbial community and the concentrations of SCFAs recovered after the voles were allowed coprophagy. Other evidence showed that the stomach of woodrats (Neotoma spp.) and mice harboured highly similar microbial community to large intestine, and the non-coprophagic mice altered the composition of microbiota and the profile of bile acid pool in the small intestine, but no changes were observed in the large intestine, indicating persistent self-reinoculation of microbiota via coprophagy (Kohl et al., 2014; Bogatyrev et al., 2020). In addition, supplementation of acetate reversed energetic, thermal and microbial homeostasis, and rescued neurological and cognitive deficits induced by coprophagy prevention in voles (Bo et al., 2020). However, it is worth mentioning that coprophagy may induce potential disease risk, since some pathogenic bacteria may be transmitted into the intestine from the feces or environments. All these findings reveal that coprophagy in herbivores promotes the stabilization of gut microbial community, and contributes to maintaining host energy balance, thermoregulation and neuronal function.

Animals and plants are actually holobionts which consist of their own genes and those of symbiotic microorganisms as well. The developments of sequencing instruments, omics technology and bioinformatics advance our understanding of these microorganisms. Growing evidence indicates that bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and animal organisms mediates host metabolic and thermal homeostasis in wild small mammals for environmental adaptations, which were summarized in this review. Besides, these microorganisms are involved in regulating host water and salt homeostasis (Nouri et al., 2022), immunity and disease defense (Rosshart et al., 2017), as well as population dynamics (Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021) in wild-living populations. All in together, the coevolution of host-microorganism symbionts promotes individual survival, population maintenance, and species coexistence in the ecosystems with complicated, variable environments.

More studies should be performed to explore the contributions of BAT and muscle in cold- and diet-induced thermogenesis. Also, the mechanisms by which microbial metabolites and byproducts regulate thermal sensation, neural conductance, and BAT and muscle thermogenesis need to be uncovered for an integrative understanding of thermoregulation in endotherms. Future studies will still focus on much deeper investigations of the functions of specific microbes from the microbial community in wild mammals and try to screen out beneficial microbiota candidates for the therapeutic potentials. Moreover, we will benefit from the combined techniques of culturomics, gene engineering and editing to identify unknown microbes, and operate targeted genetic modifications of specific intestinal microbes for improving resistance to viral and bacterial infections. In addition, further research will be strengthened to investigate the interaction and coevolution between gut microbiomes and their hosts in ecological and evolutionary contexts. As human activity perturbations and climate changes aggravate in magnitude, frequency and duration, and as the uses of antibiotics, pesticides and food additives grow, understanding their profound impacts on the real-time adaptation and long-term evolution of host–microorganism interactions will be getting more and more beneficial and have broader implications on biodiversity protection and future disease therapy.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

X-YZ wrote the manuscript; X-YZ and D-HW contributed to revision of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32090020 and 32070449), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research program (2019QZKK05010212), and Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDPB16).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agranyoni O., Meninger-Mordechay S., Uzan A., Ziv O., Salmon-Divon M., Rodin D., et al. (2021). GutMicrobiota Determines the Social Behavior of Mice and Induces Metabolic and Inflammatory Changes in Their Adipose Tissue. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 28. doi:10.1038/s41522-021-00193-9

Bai Z., Wuren T., Liu S., Han S., Chen L., McClain D., et al. (2015). Intermittent Cold Exposure Results in Visceral Adipose Tissue "browning" in the Plateau Pika (Ochotona Curzoniae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 184, 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.01.019

Bal N. C., Maurya S. K., Sopariwala D. H., Sahoo S. K., Gupta S. C., Shaikh S. A., et al. (2012). Sarcolipin Is a Newly Identified Regulator of Muscle-Based Thermogenesis in Mammals. Nat. Med. 18 (10), 1575–1579. doi:10.1038/nm.2897

Bal N. C., Periasamy M. (2020). Uncoupling of Sarcoendoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase Pump Activity by Sarcolipin as the Basis for Muscle Non-shivering Thermogenesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375 (1793), 20190135. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0135

Bal N. C., Sahoo S. K., Maurya S. K., Periasamy M. (2018). The Role of Sarcolipin in Muscle Non-shivering Thermogenesis. Front. Physiol. 9, 1217. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01217

Baskaran P., Krishnan V., Ren J., Thyagarajan B. (2016). Capsaicin Induces browning of white Adipose Tissue and Counters Obesity by Activating TRPV1 Channel-dependent Mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 2369–2389. doi:10.1111/bph.13514

Bo T.-B., Zhang X.-Y., Kohl K. D., Wen J., Tian S.-J., Wang D.-H. (2020). Coprophagy Prevention Alters Microbiome, Metabolism, Neurochemistry, and Cognitive Behavior in a Small Mammal. Isme J. 14, 2625–2645. doi:10.1038/s41396-020-0711-6

Bo T.-B., Zhang X.-Y., Wen J., Deng K., Qin X.-W., Wang D.-H. (2019). The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Interaction in Regulating Host Metabolic Adaptation to Cold in Male Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Brandtii). Isme J. 13, 3037–3053. doi:10.1038/s41396-019-0492-y

Boelen A., Kwakkel J., Thijssen-Timmer D., Alkemade A., Fliers E., Wiersinga W. (2004). Simultaneous Changes in central and Peripheral Components of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid axis in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Illness in Mice. J. Endocrinol. 182, 315–323. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1820315

Bogatyrev S. R., Rolando J. C., Ismagilov R. F. (2020). Self-reinoculation with Fecal flora Changes Microbiota Density and Composition Leading to an Altered Bile-Acid Profile in the Mouse Small Intestine. Microbiome 8, 19. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-0785-4

Boonen B., Alpizar Y., Meseguer V., Talavera K. (2018). TRP Channels as Sensors of Bacterial Endotoxins. Toxins 10, 326. doi:10.3390/toxins10080326

Bozinovic F., Ferri-Yáñez F., Naya H., Araújo M., Naya D. E. (2014). Thermal Tolerances in Rodents: Species that Evolved in Cold Climates Exhibit a Wider Thermoneutral Zone. Evol. Ecol. Res. 16, 143–152.

Brent G. A. (2012). Mechanisms of Thyroid Hormone Action. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3035–3043. doi:10.1172/jci60047

Buffington S. A., Di Prisco G. V., Auchtung T. A., Ajami N. J., Petrosino J. F., Costa-Mattioli M. (2016). Microbial Reconstitution Reverses Maternal Diet-Induced Social and Synaptic Deficits in Offspring. Cell 165, 1762–1775. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.001

Burkett J. P., Andari E., Johnson Z. V., Curry D. C., deWaal F. B. M., Young L. J. (2016). Oxytocin-dependent Consolation Behavior in Rodents. Science 351, 375–378. doi:10.1126/science.aac4785

Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2004). Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277–359. doi:10.1152/physrev.00015.2003

Chambers P. J., Juracic E. S., Fajardo V. A., Tupling A. R. (2022). Role of SERCA and Sarcolipin in Adaptive Muscle Remodeling. Am. J. Physiology-Cell Physiol. 322 (3), C382–C394. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00198.2021

Chi Q.-S., Wan X.-R., Geiser F., Wang D.-H. (2016). Fasting-induced Daily Torpor in Desert Hamsters (Phodopus Roborovskii). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 199, 71–77. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.019

Chu C., Murdock M. H., Jing D., Won T. H., Chung H., Kressel A. M., et al. (2019). The Microbiota Regulate Neuronal Function and Fear Extinction Learning. Nature 574, 543–548. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1644-y

Costford S. R., Seifert E. L., Bézaire V., F. Gerrits M., Bevilacqua L., Gowing A., et al. (2007). The Energetic Implications of Uncoupling Protein-3 in Skeletal Muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32 (5), 884–894. doi:10.1139/h07-063

Ding B.-Y., Chi Q.-S., Liu W., Shi Y.-L., Wang D.-H. (2018). Thermal Biology of Two Sympatric Gerbil Species: The Physiological Basis of Temporal Partitioning. J. Therm. Biol. 74, 241–248. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.03.025

Dittner C., Lindsund E., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2019). At Thermoneutrality, Acute Thyroxine-Induced Thermogenesis and Pyrexia Are Independent of UCP1. Mol. Metab. 25, 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2019.05.005

Ebensperger L. A. (2001). A Review of the Evolutionary Causes of Rodent Group-Living. Acta Theriol. 46, 115–144. doi:10.4098/at.arch.01-16

Ebino K. Y., Suwa T., Kuwabara Y., Saito T. R., Takahashi K. W. (1988). Coprophagy in Female Mice during Pregnancy and Lactation. Exp. Anim. 37 (1), 101–104. doi:10.1538/expanim1978.37.1_101

Fetissov S. O. (2017). Role of the Gut Microbiota in Host Appetite Control: Bacterial Growth to Animal Feeding Behaviour. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 13, 11–25. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2016.150

Garretson J. T., Szymanski L. A., Schwartz G. J., Xue B., Ryu V., Bartness T. J. (2016). Lipolysis Sensation by white Fat Afferent Nerves Triggers Brown Fat Thermogenesis. Mol. Metab. 5, 626–634. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2016.06.013

Gilbert C., McCafferty D., LeMaho Y., Martrette J. M., Giroud S., Blanc S., et al. (2010). One for All and All for One: the Energetic Benefits of Huddling in Endotherms. Biol. Rev. Camb Philos. Soc. 85, 545–569. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00115.x

Gordon C. J. (2012). Thermal Physiology of Laboratory Mice: Defining Thermoneutrality. J. Therm. Biol. 37, 654–685. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.08.004

Gould A. L., Zhang V., Lamberti L., Jones E. W., Obadia B., Korasidis N., et al. (2018). Microbiome Interactions Shape Host Fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115, E11951–E11960. doi:10.1073/pnas.1809349115

Grigg G., Nowack J., Bicudo J. E. P. W., Bal N. C., Woodward H. N., Seymour R. S. (2022). Whole‐body Endothermy: Ancient, Homologous and Widespread Among the Ancestors of Mammals, Birds and Crocodylians. Biol. Rev. 97 (2), 766–801. doi:10.1111/brv.12822

Groussin M., Mazel F., Sanders J. G., Smillie C. S., Lavergne S., Thuiller W., et al. (2017). Unraveling the Processes Shaping Mammalian Gut Microbiomes over Evolutionary Time. Nat. Commun. 8, 14319. doi:10.1038/ncomms14319

Hagen K. B., Dittmann M. T., Ortmann S., Kreuzer M., Hatt J.-M., Clauss M. (2016). Retention of Solute and Particle Markers in the Digestive Tract of Chinchillas (Chinchilla laniger ). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 100, 801–806. doi:10.1111/jpn.12441

Haig D. (2008). Huddling: Brown Fat, Genomic Imprinting and the Warm Inner Glow. Curr. Biol. 18, R172–R174. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.040

Hejcmanová P., Ortmann S., Stoklasová L., Clauss M. (2020). Digesta Passage in Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) on a Monocot or a Dicot Diet. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 246, 110720. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.110720

Hoernicke H. (1981). Utilization of Caecal Digesta by Caecotrophy (Soft Faeces Ingestion) in the Rabbit. Livestock Prod. Sci. 8 (4), 361–366.

Hoffstaetter L. J., Bagriantsev S. N., Gracheva E. O. (2018). TRPs et al.: a molecular toolkit for thermosensory adaptations. Pflugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 470, 745–759. doi:10.1007/s00424-018-2120-5

Karasov W. H., Martínez del Rio C., Caviedes-Vidal E. (2011). Ecological Physiology of Diet and Digestive Systems. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 69–93. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142152

Kasza I., Adler D., Nelson D. W., Eric Yen C.-L., Dumas S., Ntambi J. M., et al. (2019). Evaporative Cooling Provides a Major Metabolic Energy Sink. Mol. Metab. 27, 47–61. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2019.06.023

Khakisahneh S., Zhang X. Y., Nouri Z., Wang D. H. (2020). Gut Microbiota and Host Thermoregulation in Response to Ambient Temperature Fluctuations. mSystems 5 (5), e00514. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00514-20

Khakisahneh S., Zhang X.-Y., Nouri Z., Hao S.-Y., Chi Q.-S., Wang D.-H. (2019). Thyroid Hormones Mediate Metabolic Rate and Oxidative, Anti-oxidative Balance at Different Temperatures in Mongolian Gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 216, 101–109. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2018.11.016

Khakisahneh S., Zhang X. Y., Nouri Z., Wang D. H. (2022). Cecal Microbial Transplantation Attenuates Hyperthyroid‐induced Thermogenesis in Mongolian Gerbils. Microb. Biotechnol. 15 (3), 817–831. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13793

Kohl K. D., Miller A. W., Marvin J. E., Mackie R., Dearing M. D. (2014). Herbivorous Rodents (Neotoma spp.) Harbour Abundant and Active Foregut Microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2869–2878. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12376

Kojima Y., Kondo Y., Fujishita T., Mishiro‐Sato E., Kajino‐Sakamoto R., Taketo M. M., et al. (2019). Stromal Iodothyronine Deiodinase 2 ( DIO 2) Promotes the Growth of Intestinal Tumors in Apc Δ716 Mutant Mice. Cancer Sci. 110, 2520–2528. doi:10.1111/cas.14100

Lamirand A., Ramauge M., Pierre M., Courtin F. (2011). Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Induces Type 2 Deiodinase in Cultured Rat Astrocytes. J. Endocrinol. 208, 183–192. doi:10.1677/joe-10-0218

Lang D., Lu M. M., Huang L., Engleka K. A., Zhang M., Chu E. Y., et al. (2005). Pax3 Functions at a Nodal point in Melanocyte Stem Cell Differentiation. Nature 433, 884–887. doi:10.1038/nature03292

Ley R. E., Hamady M., Lozupone C., Turnbaugh P. J., Ramey R. R., Bircher J. S., et al. (2008). Evolution of Mammals and Their Gut Microbes. Science 320, 1647–1651. doi:10.1126/science.1155725

Li G., Wan X., Yin B., Wei W., Hou X., Zhang X., et al. (2021). Timing Outweighs Magnitude of Rainfall in Shaping Population Dynamics of a Small Mammal Species in Steppe Grassland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (42), e2023691118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2023691118

Li G., Li J., Kohl K. D., Yin B., Wei W., Wan X., et al. (2019). Dietary Shifts Influenced by Livestock Grazing Shape the Gut Microbiota Composition and Co-occurrence Networks in a Local Rodent Species. J. Anim. Ecol. 88 (2), 302–314. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12920

Li G., Yin B., Li J., Wang J., Wei W., Bolnick D. I., et al. (2020). Host-microbiota Interaction Helps to Explain the Bottom-Up Effects of Climate Change on a Small Rodent Species. Isme J. 14, 1795–1808. doi:10.1038/s41396-020-0646-y

Li Q., Sun R., Huang C., Wang Z., Liu X., Hou J., et al. (2001). Cold Adaptive Thermogenesis in Small Mammals from Different Geographical Zones of China. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 129, 949–961. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00357-9

Li X. S., Wang D. H. (2007). Photoperiod and Temperature Can Regulate Body Mass, Serum Leptin Concentration, and Uncoupling Protein 1 in Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Brandtii) and Mongolian Gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 80, 326–334. doi:10.1086/513189

Li Y., Schnabl K., Gabler S.-M., Willershäuser M., Reber J., Karlas A., et al. (2019). Secretin-Activated Brown Fat Mediates Prandial Thermogenesis to Induce Satiation. Cell 175 (6), 1561–1574. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.016

Liu H. C., Yang D. M., Long C., Liao P., Luo L., Tao S. L., et al. (2016). Effects of Caecotrophy Prevention on Food Digestion and Growth in Microtus Fortis. Acta Theriologica Sinica 36, 64–71. doi:10.16829/j.slxb.201601007

Liu Q.-S., Li J.-Y., Wang D.-H. (2007). Ultradian Rhythms and the Nutritional Importance of Caecotrophy in Captive Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Brandtii). J. Comp. Physiol. B 177, 423–432. doi:10.1007/s00360-006-0141-4

Lopes J. G., Sourjik V. (2018). Chemotaxis of Escherichia coli to Major Hormones and Polyamines Present in Human Gut. Isme J. 12, 2736–2747. doi:10.1038/s41396-018-0227-5

Martínez-Mota R., Kohl K. D., Orr T. J., Denise Dearing M. (2019). Natural Diets Promote Retention of the Native GutMicrobiota in Captive Rodents. Isme J. 14, 67–78. doi:10.1038/s41396-019-0497-6

Maurice C. F., Cl Knowles S., Ladau J., Pollard K. S., Fenton A., Pedersen A. B., et al. (2015). Marked Seasonal Variation in the Wild Mouse Gut Microbiota. Isme J. 9, 2423–2434. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.53

Mikane T., Araki J., Suzuki S., Mizuno J., Shimizu J., Mohri S., et al. (1999). O(2) cost of Contractility but Not of Mechanical Energy Increases with Temperature in Canine Left Ventricle. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 277, H65–H73. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.h65

Morrison S. F., Nakamura K. (2019). Central Mechanisms for Thermoregulation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 81, 285–308. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114546

Mullur R., Liu Y.-Y., Brent G. A. (2014). Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 94, 355–382. doi:10.1152/physrev.00030.2013

Nouri Z., Zhang X. Y., Khakisahneh S., Degen A. A., Wang D. H. (2022). The Microbiota-Gut-Kidney axis Mediates Host Osmoregulation in a Small Desert Mammal. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. doi:10.1038/s41522-022-00280-5

Nowack J., Geiser F. (2016). Friends with Benefits: the Role of Huddling in Mixed Groups of Torpid and Normothermic Animals. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 590–596. doi:10.1242/jeb.128926

Nowack J., Giroud S., Arnold W., Ruf T. (2017). Muscle Non-shivering Thermogenesis and its Role in the Evolution of Endothermy. Front. Physiol. 8, 889. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00889

Oelkrug R., Polymeropoulos E. T., Jastroch M. (2015). Brown Adipose Tissue: Physiological Function and Evolutionary Significance. J. Comp. Physiol. B 185 (6), 587–606. doi:10.1007/s00360-015-0907-7

Ortiga-Carvalho T. M., Sidhaye A. R., Wondisford F. E. (2014). Thyroid Hormone Receptors and Resistance to Thyroid Hormone Disorders. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 582–591. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.143

Pan Q., Li M., Shi Y.-L., Liu H., Speakman J. R., Wang D.-H. (2014). Lipidomics Reveals Mitochondrial Membrane Remodeling Associated with Acute Thermoregulation in a Rodent with aWide Thermoneutral Zone. Lipids 49, 715–730. doi:10.1007/s11745-014-3900-0

Pei Y. X., Wang D. H., Hume I. D. (2001). Selective Digesta Retention and Coprophagy in Brandt's Vole (Microtus Brandti). J. Comp. Physiol. B 171, 457–464. doi:10.1007/s003600100195

Peier A. M., Moqrich A., Hergarden A. C., Reeve A. J., Andersson D. A., Story G. M., et al. (2002). A TRP Channel that Senses Cold Stimuli and Menthol. Cell 108, 705–715. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9

Periasamy M., Huke S. (2001). SERCA Pump Level Is a Critical Determinant of Ca2+Homeostasis and Cardiac Contractility. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 1053–1063. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1366

Perofsky A. C., Lewis R. J., Meyers L. A. (2019). Terrestriality and Bacterial Transfer: a Comparative Study of Gut Microbiomes in Sympatric Malagasy Mammals. Isme J. 13, 50–63. doi:10.1038/s41396-018-0251-5

Rastelli M., Cani P. D., Knauf C. (2019). The Gut Microbiome Influences Host Endocrine Functions. Endocr. Rev. 40, 1271–1284. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00280

Ren Y., Song S., Liu X., Yang M. (2022). Phenotypic Changes in the Metabolic Profile and Adiponectin Activity during Seasonal Fattening and Hibernation in Female Daurian Ground Squirrels ( Spermophilus Dauricus ). Integr. Zool. 17 (2), 297–310. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12504

Ridlon J. M., Kang D.-J., Hylemon P. B. (2006). Bile Salt Biotransformations by Human Intestinal Bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 47, 241–259. doi:10.1194/jlr.r500013-jlr200

Rosshart S. P., Vassallo B. G., Angeletti D., Hutchinson D. S., Morgan A. P., Takeda K., et al. (2017). Wild Mouse Gut Microbiota Promotes Host Fitness and Improves Disease Resistance. Cell 171, 1015–1028. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.016

Roth J., Leroith D., Shiloach J., Rosenzweig J. L., Lesniak M. A., Havrankova J. (1982). The Evolutionary Origins of Hormones, Neurotransmitters, and Other Extracellular Chemical Messengers: Implications for Mammalian Biology. N. Engl. J. Med. 306, 523–527. doi:10.1056/NEJM198203043060907

Rowland L. A., Bal N. C., Periasamy M. (2015). The Role of Skeletal-Muscle-Based Thermogenic Mechanisms in Vertebrate Endothermy. Biol. Rev. 90 (4), 1279–1297. doi:10.1111/brv.12157

Salvatore D., Simonides W. S., Dentice M., Zavacki A. M., Larsen P. R. (2014). Thyroid Hormones and Skeletal Muscle-New Insights and Potential Implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10 (4), 206–214. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.238

Sanchez-Gurmaches J., Hung C.-M., Sparks C. A., Tang Y., Li H., Guertin D. A. (2012). PTEN Loss in the Myf5 Lineage Redistributes Body Fat and Reveals Subsets of white Adipocytes that Arise from Myf5 Precursors. Cel Metab. 16, 348–362. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.003

Sassi P. L., Caviedes-Vidal E., Anton R., Bozinovic F. (2010). Plasticity in Food Assimilation, Retention Time and Coprophagy Allow Herbivorous Cavies (Microcavia Australis) to Cope with Low Food Quality in the Monte Desert. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 155, 378–382. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.12.007

Sgaier S., Millet S., Villanueva M., Berenshteyn F., Song C., Joyner A. (2005). Morphogenetic and Cellular Movements that Shape the Mouse CerebellumInsights from Genetic Fate Mapping. Neuron 45, 27–40. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00802-5

Shamsi F., Piper M., Ho L.-L., Huang T. L., Gupta A., Streets A., et al. (2021). Vascular Smooth Muscle-Derived Trpv1+ Progenitors Are a Source of Cold-Induced Thermogenic Adipocytes. Nat. Metab. 3 (4), 485–495. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00373-z

Shin H., Ma Y., Chanturiya T., Cao Q., Wang Y., Kadegowda A. K. G., et al. (2017). Lipolysis in Brown Adipocytes Is Not Essential for Cold-Induced Thermogenesis in Mice. Cell Metab. 26 (5), 764–777. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.002

Shin N. R., Bose S., Wang J. H., Nam Y. D., Song E. J., Lim D. W., et al. (2020). Chemically or Surgically Induced Thyroid Dysfunction Altered GutMicrobiota in Rat Models. Faseb j. 34, 8686–8701. doi:10.1096/fj.201903091rr

Shu L., Hoo R. L. C., Wu X., Pan Y., Lee I. P. C., Cheong L. Y., et al. (2017). A-FABP Mediates Adaptive Thermogenesis by Promoting Intracellular Activation of Thyroid Hormones in Brown Adipocytes. Nat. Commun. 8, 14147. doi:10.1038/ncomms14147

Škop V., Guo J., Liu N., Xiao C., Hall K. D., Gavrilova O., et al. (2020). Mouse Thermoregulation: Introducing the Concept of the Thermoneutral Point. Cell Rep 31, 107501. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.065

Škop V., Xiao C., Liu N., Gavrilova O., Reitman M. L. (2021). The Effects of Housing Density on Mouse thermal Physiology Depend on Sex and Ambient Temperature. Mol. Metab. 53, 101332. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101332

Smith A. S., Wang Z. (2014). Hypothalamic Oxytocin Mediates Social Buffering of the Stress Response. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 281–288. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.017

Smith R. E., Roberts J. C. (1964). Thermogenesis of Brown Adipose Tissue in Cold-Acclimated Rats. Am. J. Physiology-Legacy Content 206, 143–148. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.206.1.143

Smith W. S., Broadbridge R., East J. M., Lee A. G. (2002). Sarcolipin Uncouples Hydrolysis of ATP from Accumulation of Ca2+ by the Ca2+-ATPase of Skeletal-Muscle Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Biochem. J. 361, 277–286. doi:10.1042/bj3610277

Solanes G., Pedraza N., Calvo V., Vidal-Puig A., Lowell B. B., Villarroya F. (2005). Thyroid Hormones Directly Activate the Expression of the Human and Mouse Uncoupling Protein-3 Genes through a Thyroid Response Element in the Proximal Promoter Region. Biochem. J. 386, 505–513. doi:10.1042/bj20041073

Speakman J. R., Chi Q., Ołdakowski Ł., Fu H., Fletcher Q. E., Hambly C., et al. . (2021). Surviving winter on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: Pikas Suppress Energy Demands and Exploit Yak Feces to Survive winter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (30), e2100707118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2100707118

Sukemori S., Ikeda S., Kurihara Y., Ito S. (2003). Amino Acid, mineral and Vitamin Levels in Hydrous Faeces Obtained from Coprophagy-Prevented Rats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 87, 213–220. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0396.2003.00415.x

Sukhchuluun G., Zhang X.-Y., Chi Q.-S., Wang D.-H. (2018). Huddling Conserves Energy, Decreases Core Body Temperature, but Increases Activity in Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Brandtii). Front. Physiol. 9, 563. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00563

Suzuki T. A., Martins F. M., Nachman M. W. (2019). Altitudinal Variation of the Gut Microbiota in Wild House Mice. Mol. Ecol. 28, 2378–2390. doi:10.1111/mec.14905

Symonds M. E., Pope M., Budge H. (2015). The Ontogeny of Brown Adipose Tissue. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 35 (1), 295–320. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105330

Townsend K. L., Tseng Y.-H. (2014). Brown Fat Fuel Utilization and Thermogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 25 (4), 168–177. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.004

Vandewauw I., De Clercq K., Mulier M., Held K., Pinto S., Van Ranst N., et al. (2018). A TRP Channel Trio Mediates Acute Noxious Heat Sensing. Nature 555, 662–666. doi:10.1038/nature26137

Virili C., Centanni M. (2017). "With a Little Help from My Friends" - the Role of Microbiota in Thyroid Hormone Metabolism and Enterohepatic Recycling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 458, 39–43. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.053

Virili C., Centanni M. (2015). Does Microbiota Composition Affect Thyroid Homeostasis? Endocrine 49, 583–587. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0509-2

Wang J.-M., Zhang Y.-M., Wang D.-H. (2006). Seasonal Thermogenesis and Body Mass Regulation in Plateau Pikas (Ochotona Curzoniae). Oecologia 149, 373–382. doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0469-1

Watanabe M., Houten S. M., Mataki C., Christoffolete M. A., Kim B. W., Sato H., et al. (2006). Bile Acids Induce Energy Expenditure by Promoting Intracellular Thyroid Hormone Activation. Nature 439, 484–489. doi:10.1038/nature04330

Wen J., Bo T., Zhang X., Wang Z., Wang D. (2020). Thermo-TRPs and Gut Microbiota Are Involved in Thermogenesis and Energy Metabolism during Low Temperature Exposure of Obese Mice. J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb218974. doi:10.1242/jeb.218974

Wen J., Bo T., Zhao Z., Wang D. (2021). Role of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid‐1 in Behavioral Thermoregulation of the Mongolian Gerbil Meriones unguiculatus. Integr. Zool. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12587

Worthmann A., John C., Rühlemann M. C., Baguhl M., Heinsen F.-A., Schaltenberg N., et al. (2017). Cold-induced Conversion of Cholesterol to Bile Acids in Mice Shapes the Gut Microbiome and Promotes Adaptive Thermogenesis. Nat. Med. 23, 839–849. doi:10.1038/nm.4357

Wu W.-L., Adame M. D., Liou C.-W., Barlow J. T., Lai T.-T., Sharon G., et al. (2021). Microbiota Regulate Social Behaviour via Stress Response Neurons in the Brain. Nature 595, 409–414. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03669-y

Yau W. W., Singh B. K., Lesmana R., Zhou J., Sinha R. A., Wong K. A., et al. (2019). Thyroid Hormone (T(3)) Stimulates Brown Adipose Tissue Activation via Mitochondrial Biogenesis and MTOR-Mediated Mitophagy. Autophagy 15 (1), 131–150. doi:10.1080/15548627.2018.1511263

Zhang X.-Y., Sukhchuluun G., Bo T.-B., Chi Q.-S., Yang J.-J., Chen B., et al. (2018). Huddling Remodels Gut Microbiota to Reduce Energy Requirements in a Small Mammal Species during Cold Exposure. Microbiome 6, 103. doi:10.1186/s40168-018-0473-9

Zhang X.-Y., Wang D.-H. (2006). Energy Metabolism, Thermogenesis and Body Mass Regulation in Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Brandtii) during Cold Acclimation and Rewarming. Horm. Behav. 50, 61–69. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.01.005

Zhang X. Y., Chi Q. S., Liu W., Wang D. H. (2016). Studies of Behavioral and Physiological Ecology in Mongolian Gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Sci. Sin Vitae 46, 120–128. doi:10.1360/n052015-00351

Zhao J., Li G., Lu W., Huang S., Zhang Z. (2020). Dominant and Subordinate Relationship Formed by Repeated Social Encounters Alters Gut Microbiota in Greater Long-Tailed Hamsters. Microb. Ecol. 79, 998–1010. doi:10.1007/s00248-019-01462-z

Zhao Z.-J., Wang D.-H. (2006). Short Photoperiod Influences Energy Intake and Serum Leptin Level in Brandt's Voles (Microtus Brandtii). Horm. Behav. 49, 463–469. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.10.003

Zhou L., Li X., Ahmed A., Wu D., Liu L., Qiu J., et al. (2014). Gut Microbe Analysis between Hyperthyroid and Healthy Individuals. Curr. Microbiol. 69, 675–680. doi:10.1007/s00284-014-0640-6

Keywords: gut microbiota, norepinephrine (NE), small mammals, thermoregulation, thyroid hormones

Citation: Zhang X-Y and Wang D-H (2022) Gut Microbial Community and Host Thermoregulation in Small Mammals. Front. Physiol. 13:888324. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.888324

Received: 02 March 2022; Accepted: 28 March 2022;

Published: 11 April 2022.

Edited by:

Geoffrey A. Head, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, AustraliaReviewed by:

Naresh Chandra Bal, KIIT University, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: De-Hua Wang, ZGVodWF3YW5nQHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.