95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol. , 28 April 2022

Sec. Aquatic Physiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.877178

This article is part of the Research Topic Nutritional Physiology of Aquacultured Species View all 12 articles

When fish are under oxidative stress, levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chronically elevated, which play a crucial role in fish innate immunity. In the present study, the mechanism by which betaine regulates ROS production via Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling was investigated in zebrafish liver. Our results showed that betaine enrichment of diet at 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg induced Wnt10b and β-catenin gene expression, but suppressed GSK-3β expression in zebrafish liver. In addition, the content of superoxide anion (O2·−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (·OH) was decreased by all of the experimental betaine treatments. However, betaine enrichment of diet at 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg enhanced gene expression and activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) and catalase (CAT) in zebrafish liver. In addition, Wnt10b RNA was further interfered in zebrafish, and the results of Wnt10b RNAi indicated that Wnt10b plays a key role in regulating ROS production and antioxidant enzyme activity. In conclusion, betaine can inhibit ROS production in zebrafish liver through the Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Due to various stress factors in the aquatic environment, fish are prone to stimulate inflammatory responses (Saurabh and Sahoo, 2008; Troncoso, et al., 2012). In addition, the antioxidant status is closely related to the innate immunity of fish species (Kuang, et al., 2012; Tort, et al., 2003). Generally speaking, the existence of various antioxidant enzymes, the generation and elimination of ROS in fish are in a state of dynamic equilibrium. However, if the homeostasis is disrupted, excess ROS can be produced in fish tissues. Excessive production of ROS is closely related to lipid peroxidation, cellular damage and protein oxidation (Cooke, et al., 2003; Martínez-Álvarez, et al., 2005; Maynard, et al., 2009). Furthermore, high levels of ROS exacerbate oxidative stress and induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Naik and Dixit, 2011). To protect animals from ROS-mediated damage, various antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) and catalase (CAT), play key roles in regulating the balance of ROS levels (Martínez-Álvarez, et al., 2005).

The chemical structural formula of betaine is (CH3)3N+–CH2COO−, which is a naturally occurring metabolite in animals (Craig, 2004). In addition, betaine, a by-product of sugar beet processing, is used commercially as a feed additive in aquaculture fish feeds (Eklund, et al., 2005). Today, betaine is widely used as an attractant in aquaculture. Moreover, betaine plays an important role in regulating cellular osmotic pressure (Nakanishi, et al., 1990). Previously, betaine was observed to accumulate in mammalian renal medulla cells and chicken fibroblasts under osmotic stress, thereby functioning to regulate osmotic pressure and monitor water content (Bagnasco, et al., 1986; Eklund, et al., 2005; Kidd, et al., 1997; Petronini, et al., 1992). In addition, betaine reduces the osmotic pressure of Atlantic salmon and improves the ability to maintain osmotic balance (Virtanen, et al., 1989). Addition of betaine to fish feed significantly improves feed utilization, survival, and fish growth (Craig, 2004; Liang, et al., 2001; Luo, et al., 2011; Wu and Davis, 2005).

Cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin is a decisive event in cells in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. In addition, the molecule GSK-3β is involved in the regulation of cytoplasmic β-catenin levels (Logan and Nusse, 2004; Veeman, et al., 2003; Zeng, et al., 1997). After the Wnt molecule binds to the receptor complex on the cell membrane, the activity of GSK-3β decreases and β-catenin accumulates, which further regulates the expression of target genes (Bhanot, et al., 1996; Molenaar, et al., 1996). In a previous study, it was observed that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1 cells (Qi, et al., 2016).

Under oxidative stress, ROS production in animals is chronically increased, disrupting cellular metabolism and fish immunity (Lushchak, 2014). Previously, betaine has been shown to have antioxidant properties in a variety of animals (Doğru-Abbasoğlu, et al., 2018; Heidari, et al., 2018; Wen, et al., 2019). However, the regulatory mechanism of betaine on ROS production via Wnt10b signaling remains unknown in fish species. Previous studies have shown that betaine increases stress resistance, and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a role in regulating oxidative stress (Kim, et al., 2014; Li, et al., 2019; Qi, et al., 2016; Zhang, et al., 2018). It is interesting to examine whether betaine regulates ROS production in fish through the Wnt10b signaling pathway. The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanism by which betaine modulates ROS production via Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling in zebrafish liver.

Betaine was purchased from Sunwin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Weifang, China). Casein and gelatin were used as protein sources. Four isoenergetic and isonitrogenic diets containing 0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 g/kg betaine were prepared according to Table 1. The ingredients were ground into powder then passed through a 120 μm sieve, and mixed with lard and linseed oil. Then, the appropriate amount of water (300 ml/kg dry ingredient) was added to the ingredients and blended with a tablet machine to form flakes. Finally, the flakes were dried in a ventilated oven at 40°C for 10 h, pulverized, sieved into small particles (200–300 μm), and stored at −20°C for later use.

Male zebrafish (AB strain, ∼3.2 cm) were cultured in 3.0 L flow-through glass jars with circulating dechlorinated water at 28°C on a 14 h light:10 h dark cycle. The fish were then fed ad libitum twice a day at 8:00 and 18:00 with commercial feed obtained from Sanyou Landscaping Feed Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for 2 weeks of acclimation. Two different experimental rearings were performed, the first involving betaine levels in the experimental diet and the second involving Wnt10b RNA interference.

First, experimental feeding on the four betaine level diets was performed as follows. 180 male zebrafish were assigned to 12 tanks (15 fish per tank) and each betaine level (0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine) was distributed into three tanks. The fish were fed ad libitum twice a day at 8:00 and 18:00. 6 weeks later, after zebrafish were anesthetized with 0.1 g/L MS 222, a liver sample was collected from five fish per tank for gene expression analysis. In addition, another liver sample was collected from five fish in each tank for biochemical indicator analysis. Three replicates were used for each betaine level treatment group.

First, the Wnt10b gene (AY182171.1) was cloned according to the primers listed in Table 2. Then, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was synthesized using the primers listed in Table 2 according to the previous method (Arockiaraj, et al., 2014). Experimental rearing for Wnt10b RNA interference (Wnt10b RNAi) was performed as follows. After 2 weeks of acclimation, 90 male zebrafish (∼3.8 cm) were allocated to six tanks for Wnt10b RNAi. For the RNAi group (3 tanks), fish were intraperitoneally injected with 500 ng of dsRNA diluted in DEPEC-treated water, while fish in the control group (3 tanks) were intraperitoneally injected with 5 μl of DEPEC-treated water. Then, the two groups of zebrafish were fed ad libitum a diet containing 0.4 g/kg betaine at 8:00 and 18:00 every day. After 6 days, the fish were sampled for analysis as the betaine treatment experiments.

Liver samples were homogenized and centrifuged at 5,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were collected for biochemical analysis. The supernatant ·OH, H2O2, O2·− levels, and CAT, SOD, GSH-PX activity were measured using commercial kits purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The protein concentration in the supernatant was detected at 595 nm according to the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). SOD activity was measured at 550 nm by measuring inhibition of the reduction rate of cytochrome c, and CAT activity was measured by analyzing residual H2O2 absorbance at 405 nm. Activity of GSH-PX was detected by analyzing the rate of NADPH oxidation at 412 nm. In addition, since H2O2 can form a stable complex with ammonium molybdate, the content of H2O2 was detected at 405 nm. The production of ·OH was detected according to the production of hydrogen peroxide, and the production of O2·− was measured at 550 nm by the xanthine oxidase method.

The primer sequences for various target genes and reference gene (β-actin) were shown in Table 3. Subsequently, real-time PCR was performed in a quantitative thermal cycler (ROCHE, Lightcycler 480, Switzerland) using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara, Japan). The program for quantitative RT-PCR was as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Finally, the relative gene expression level was detected by 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (sem). SPSS 16.0 was used to analyze statistical differences. Then, after testing for normality and homogeneity of variance between groups, the results were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. In addition, RNAi experiments were analyzed by t-test analysis using independent samples. Differences were set at p < 0.05.

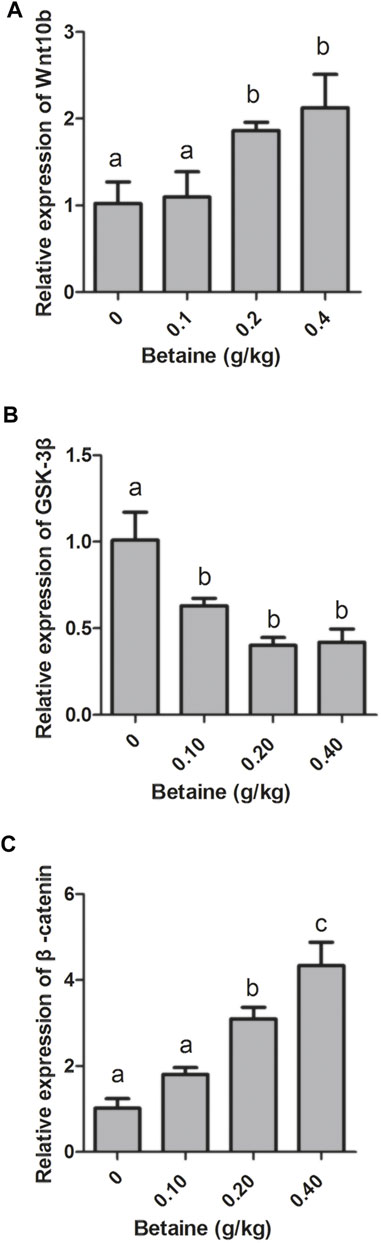

Compared with control, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly induced Wnt10b gene expression, while 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly decreased GSK-3β gene expression (Figures 1A,B). However, the gene expression of GSK-3β was not significantly different between 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments (Figure 1B). Furthermore, betaine enrichment of diet at 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg significantly enhanced β-catenin gene expression (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1. Effect of betaine on the mRNA expression of Wnt10b, GSK-3β, and β-catenin in the liver of zebrafish. (A) The mRNA expression of Wnt10b; (B) The mRNA expression of GSK-3β; (C) The mRNA expression of β-catenin. Values are expressed as means ± sem (n = 3). Statistically significant differences are denoted by different letters (p < 0.05).

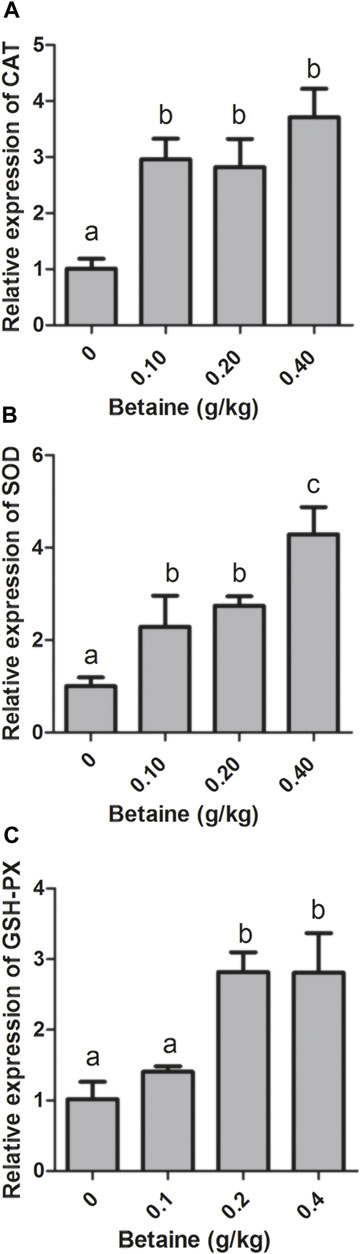

0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly induced CAT and SOD gene expression compared with control (Figures 2A,B). However, there was no significant difference in CAT gene expression between three betaine treatments (Figure 2A). In addition, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly induced GSH-PX gene expression (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2. Effect of betaine on the mRNA expression of CAT, SOD, and GSH-PX in the liver of zebrafish. (A) The mRNA expression of CAT; (B) The mRNA expression of SOD; (C) The mRNA expression of GSH-PX. Values are expressed as means ± sem (n = 3). Statistically significant differences are denoted by different letters (p < 0.05).

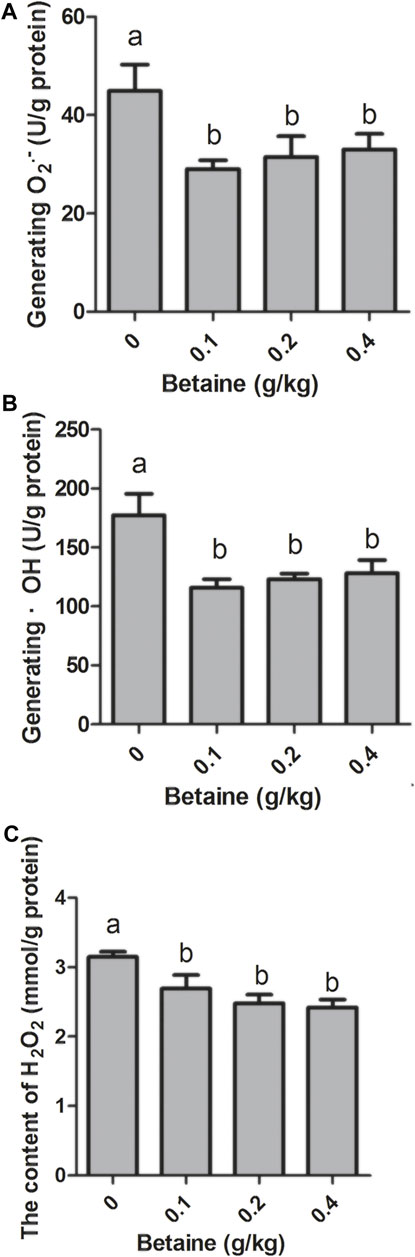

0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly reduced O2·− level, but there was no significant difference between 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments (Figure 3A). In addition, three betaine treatments significantly reduced the levels of ·OH and H2O2 (Figures 3B,C).

FIGURE 3. Effect of betaine on the level of ROS in the liver of zebrafish. (A) The level of O2·−; (B) The level of ·OH; (C) The level of H2O2. Values are expressed as means ± sem (n = 3). Statistically significant differences are denoted by different letters (p < 0.05).

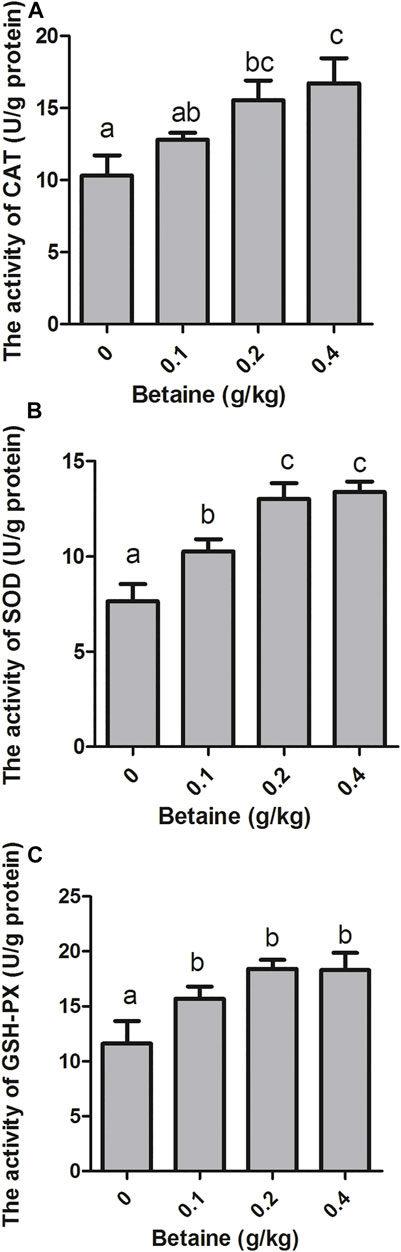

0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments significantly increased CAT activity, while no significant difference was observed between 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg betaine treatments (Figure 4A). Furthermore, betaine enrichment of diet at 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 g/kg significantly increased the activities of SOD and GSH-PX (Figures 4B,C).

FIGURE 4. Effect of betaine on the activities of antioxidant enzymes in the liver of zebrafish. (A) The activity of CAT; (B) The activity of SOD; (C) The activity of GSH-PX. Values are expressed as means ± sem (n = 3). Statistically significant differences are denoted by different letters (p < 0.05).

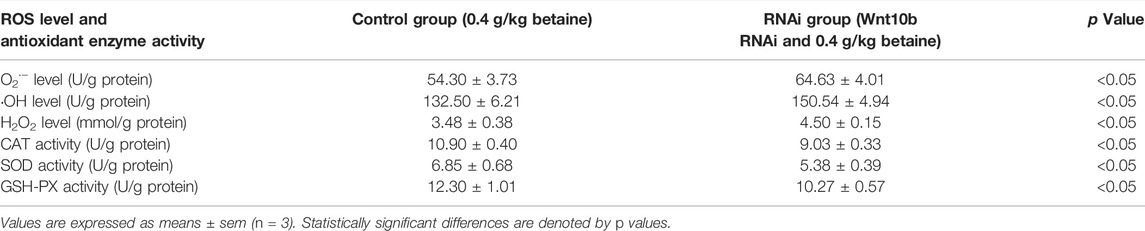

Interference of Wnt10b RNA significantly reduced Wnt10b gene expression and significantly increased GSK-3β gene expression (Table 4). In addition, Wnt10b RNAi significantly reduced the expression of β-catenin gene (Table 4).

Interference with Wnt10b RNA significantly reduced the gene expression of CAT and SOD compared to controls (Table 4). In addition, Wnt10b RNAi in zebrafish liver also significantly suppressed GSH-PX gene expression (Table 4).

Wnt10b RNAi treatment significantly increased the level of O2·− (Table 5). Interference of Wnt10b RNA also significantly increased the levels of ·OH and H2O2 (Table 5). Furthermore, Wnt10b RNAi treatment significantly reduced SOD, CAT and GSH-PX activities in zebrafish liver (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Effect of Wnt10b RNA interference on the level of ROS and activities of antioxidant enzymes in the liver of zebrafish.

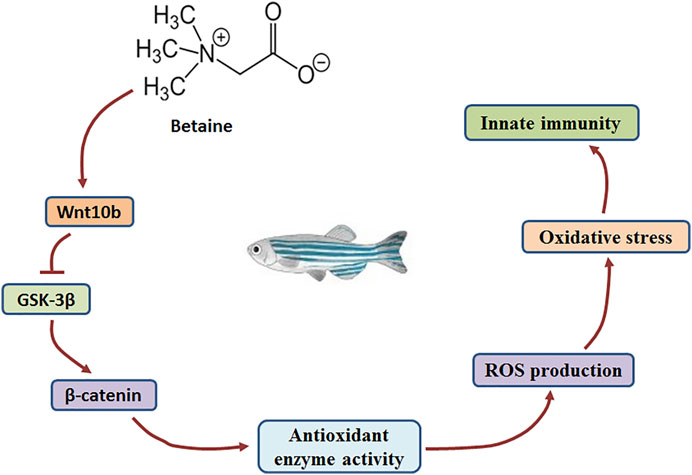

Wnt molecules play a key role in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Cossu and Borello, 1999; Ridgeway, et al., 2000; Taelman, et al., 2010; Valenta, et al., 2012). GSK-3β activity is hindered as Wnt molecules bind to receptors on the cell membrane (Taelman, et al., 2010). In addition, β-catenin levels are closely related to the activity of GSK-3β (Huelsken and Behrens, 2002). In the present study, gene expression of both Wnt10b and β-catenin was induced, but GSK-3β gene expression was decreased by betaine treatment in zebrafish liver. Our findings suggest that betaine can stimulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by inducing Wnt10b and inhibiting GSK-3β expression (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. The mechanism by which betaine regulates the production of ROS through Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling pathway in the zebrafish liver.

Under conditions of oxidative stress, ROS production in fish will be enhanced over time. However, overproduction of ROS can damage cellular components and interfere with cellular metabolism (Lushchak, 2014). Previously, betaine has been shown to have antioxidant properties in various animals. Betaine attenuates oxidative stress in the liver of rat fed with the high-fructose and thioacetamide diet (Doğru-Abbasoğlu, et al., 2018; Heidari, et al., 2018). In addition, betaine reduces the negative effects of heat stress-stimulated oxidative status in broilers (Wen, et al., 2019), and betaine alleviates heat stress in dairy cows (Hall, et al., 2016; Zhang, et al., 2014). In this study, different concentrations of betaine in diet reduced the levels of O2.−, ·OH and H2O2 within fish liver. Furthermore, the increasing betaine content in diet significantly induced the gene expression and activity of CAT, SOD and GSH-PX in zebrafish liver. In the current study, we also found that the higher content of betaine can better reduce the level of ROS and increase the activity of antioxidant-related enzymes, which is consistent with the results of previous studies on betaine.

To confirm that Wnt10b plays a key role in regulating ROS levels, fish were intraperitoneally injected with Wnt10b dsRNA and ROS production was further detected in zebrafish liver. The results showed that β-catenin gene expression was inhibited, and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was inhibited by Wnt10b RNAi. In addition, Wnt10b RNAi increased the levels of O2.−, ·OH and H2O2 in zebrafish liver, while decreasing the activities of SOD, CAT and GSH-PX. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was previously found to play a role in regulating oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1 cells (Qi, et al., 2016). Our findings also suggest that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a key role in regulating antioxidant-related enzyme activities and ROS levels. Therefore, for betaine-induced Wnt/β-catenin signaling, it clearly demonstrated that betaine can inhibit ROS production in zebrafish liver through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Figure 5).

In addition, betaine has three active methyl groups and plays a unique role in animal nutrition metabolism. Methyl groups are necessary for animal metabolism and cannot be synthesized by animals themselves. Therefore, betaine is one of the most efficient active methyl donors due to its unique structure (Kidd, et al., 1997). It has been previously found that if animals have enough betaine in their bodies, they can store more methionine for other metabolic activities (Lipiński, et al., 2012; Pereira, et al., 2018). Betaine is involved in regulating various physiological activities of animals (Zhang, et al., 2016). In addition, betaine has the ability to modulate osmotic changes and water imbalance during heat stress (Mahmoudnia and Madani, 2012; Zhou, et al., 2012). In the poultry industry, betaine can maintain the moisture of poultry cells and improve the ability of poultry to resist heat stress (Saeed, et al., 2017). In the current study, we observed that betaine reduced ROS levels and increased the activities of antioxidant-related enzymes. The ability of betaine to reduce ROS levels may also be related to osmoprotectant and methyl-donating properties. However, the specific mechanism needs to be further studied in future research.

In conclusion, a mechanism by which betaine modulates oxidative stress via Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling was discovered in zebrafish liver. Our findings suggest that betaine can induce Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling in zebrafish liver. ROS levels are reduced in zebrafish liver, but betaine enhances the activity of antioxidant-related enzymes. Furthermore, the results of Wnt10b RNAi indicated that the Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a key role in regulating ROS production and antioxidant-related enzymatic activities. Taken together, betaine can inhibit ROS production in zebrafish liver through Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Shandong University of Technology under the Guidelines for the Correct Conduct of Animal Experimentation (Science Council of China).

DL contributed to the conception and design of the work. AL, HY, YG, XZ and QP contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. AL, DL, XZ and QP drafted and critically revised the work.

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (31701845), Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (2019JZZY020710), and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (ZR2017MC066 and ZR2017BC005).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Arockiaraj J., Palanisamy R., Bhatt P., Kumaresan V., Gnanam A. J., Pasupuleti M., et al. (2014). A Novel Murrel Channa Striatus Mitochondrial Manganese Superoxide Dismutase: Gene Silencing, SOD Activity, Superoxide Anion Production and Expression. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 40, 1937–1955. doi:10.1007/s10695-014-9981-0

Bagnasco S., Balaban R., Fales H. M., Yang Y. M., Burg M. (1986). Predominant Osmotically Active Organic Solutes in Rat and Rabbit Renal Medullas. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 5872–5877. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(17)38464-8

Bhanot P., Brink M., Samos C. H., Hsieh J.-C., Wang Y., Macke J. P., et al. (1996). A New Member of the Frizzled Family from Drosophila Functions as a Wingless Receptor. Nature 382, 225–230. doi:10.1038/382225a0

Bradford M. M. (1976). A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Cooke M. S., Evans M. D., Dizdaroglu M., Lunec J. (2003). Oxidative DNA Damage: Mechanisms, Mutation, and Disease. FASEB J. 17, 1195–1214. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0752rev

Cossu G., Borello U. (1999). Wnt Signaling and the Activation of Myogenesis in Mammals. EMBO J. 18, 6867–6872. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.24.6867

Craig S. A. (2004). Betaine in Human Nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 539–549. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539

Doğru-Abbasoğlu S., Soluk-Tekkeşin M., Olgaç V., Uysal M. (2018). Effect of Betaine Treatment on the Regression of Existing Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation and Oxidative Stress in Rats Fed on High Fructose Diet. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 37, 563–570.

Eklund M., Bauer E., Wamatu J., Mosenthin R. (2005). Potential Nutritional and Physiological Functions of Betaine in Livestock. Nutr. Res. Rev. 18, 31–48. doi:10.1079/nrr200493

Hall L. W., Dunshea F. R., Allen J. D., Rungruang S., Collier J. L., Long N. M., et al. (2016). Evaluation of Dietary Betaine in Lactating Holstein Cows Subjected to Heat Stress. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 9745–9753. doi:10.3168/jds.2015-10514

Heidari R., Niknahad H., Sadeghi A., Mohammadi H., Ghanbarinejad V., Ommati M. M., et al. (2018). Betaine Treatment Protects Liver through Regulating Mitochondrial Function and Counteracting Oxidative Stress in Acute and Chronic Animal Models of Hepatic Injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 103, 75–86. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.010

Huelsken J., Behrens J. (2002). The Wnt Signalling Pathway. J. Cell Sci 115, 3977–3978. doi:10.1242/jcs.00089

Kidd M. T., Ferket P. R., Garlich J. D. (1997). Nutritional and Osmoregulatory Functions of Betaine. World's Poult. Sci. J. 53, 125–139. doi:10.1079/WPS19970013

Kim D. H., Sung B., Kang Y. J., Jang J. Y., Hwang S. Y., Lee Y., et al. (2014). Anti-inflammatory Effects of Betaine on AOM/DSS-induced colon Tumorigenesis in ICR Male Mice. Int. J. Oncol. 45, 1250–1256. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2515

Kuang S.-Y., Xiao W.-W., Feng L., Liu Y., Jiang J., Jiang W.-D., et al. (2012). Effects of Graded Levels of Dietary Methionine Hydroxy Analogue on Immune Response and Antioxidant Status of Immune Organs in Juvenile Jian Carp (Cyprinus carpio Var. Jian). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 32, 629–636. doi:10.1016/j.fsi.2011.12.012

Li C., Wang Y., Li L., Han Z., Mao S., Wang G. (2019). Betaine Protects against Heat Exposure-Induced Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells via Regulation of ROS Production. Cell Stress and Chaperones 24, 453–460. doi:10.1007/s12192-019-00982-4

Liang M.-q., Yu H., Chang Q., Chen C. (2001). Effects of Feeding Stimularnt on Intake and Growth of Red Seabream Pagrosomus Major. Zhongguo shui chan ke Xue = J. Fish. Sci. China 8, 58–61.

Lipiński K., Szramko E., Jeroch H., Matusevičius P. (2012). Effects of Betaine on Energy Utilization in Growing Pigs-A Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 12, 291–300.

Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Logan C. Y., Nusse R. (2004). The Wnt Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 781–810. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126

Luo Z., Tan X.-Y., Liu X.-J., Wen H. (2011). Effect of Dietary Betaine Levels on Growth Performance and Hepatic Intermediary Metabolism of GIFT Strain of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus Reared in Freshwater. Aquac. Nutr. 17, 361–367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2095.2010.00805.x

Lushchak V. I. (2014). Free Radicals, Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Stress and its Classification. Chemico-Biological Interactions 224, 164–175. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.016

Mahmoudnia N., Madani Y. (2012). Effect of Betaine on Performance and Carcass Composition of Broiler Chicken in Warm Weather-A Review. Int. J. Agrisci 2, 675–683.

Martínez-Álvarez R. M., Morales A. E., Sanz A. (2005). Antioxidant Defenses in Fish: Biotic and Abiotic Factors. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 15, 75–88. doi:10.1007/s11160-005-7846-4

Maynard S., Schurman S. H., Harboe C., de Souza-Pinto N. C., Bohr V. A. (2009). Base Excision Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage and Association with Cancer and Aging. Carcinogenesis 30, 2–10. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgn250

Molenaar M., van de Wetering M., Oosterwegel M., Peterson-Maduro J., Godsave S., Korinek V., et al. (1996). XTcf-3 Transcription Factor Mediates β-Catenin-Induced Axis Formation in Xenopus Embryos. Cell 86, 391–399. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9

Naik E., Dixit V. M. (2011). Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Drive Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. J. Exp. Med. 208, 417–420. doi:10.1084/jem.20110367

Nakanishi T., Turner R. J., Burg M. B. (1990). Osmoregulation of Betaine Transport in Mammalian Renal Medullary Cells. Am. J. Physiology-Renal Physiol. 258, F1061–F1067. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.4.F1061

Pereira R., Menten J., Longo F., Lima M., Freitas L., Zavarize K. (2018). Sources of Betaine as Methyl Group Donors in Broiler Diets. Iran J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 8, 325–332.

Petronini P. G., De Angelis E. M., Borghetti P., Borghetti A. F., Wheeler K. P. (1992). Modulation by Betaine of Cellular Responses to Osmotic Stress. Biochem. J. 282 (Pt 1), 69–73. doi:10.1042/bj2820069

Qi H.-H., Bao J., Zhang Q., Ma B., Gu G.-Y., Zhang P.-L., et al. (2016). Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Plays an Important Role in the Protective Effects of FDP-Sr against Oxidative Stress Induced Apoptosis in MC3T3-E1 Cell. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 4720–4723. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.08.043

Ridgeway A. G., Petropoulos H., Wilton S., Skerjanc I. S. (2000). Wnt Signaling Regulates the Function of MyoD and Myogenin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32398–32405. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004349200

Saeed M., Babazadeh D., Naveed M., Arain M. A., Hassan F. U., Chao S. (2017). Reconsidering Betaine as a Natural Anti-heat Stress Agent in Poultry Industry: a Review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49, 1329–1338. doi:10.1007/s11250-017-1355-z

Saurabh S., Sahoo P. K. (2008). Lysozyme: an Important Defence Molecule of Fish Innate Immune System. Aquaculture Res 39, 223–239. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01883.x

Taelman V. F., Dobrowolski R., Plouhinec J.-L., Fuentealba L. C., Vorwald P. P., Gumper I., et al. (2010). Wnt Signaling Requires Sequestration of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 inside Multivesicular Endosomes. Cell 143, 1136–1148. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034

Tort L., Balasch J., Mackenzie S. (2003). Fish Immune System. A Crossroads between Innate and Adaptive Responses. Inmunología 22, 277–286.

Troncoso I. C., Cazenave J., Bacchetta C., Bistoni M. d. l. Á. (2012). Histopathological Changes in the Gills and Liver of Prochilodus lineatus from the Salado River basin (Santa Fe, Argentina). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 38, 693–702. doi:10.1007/s10695-011-9551-7

Valenta T., Hausmann G., Basler K. (2012). The many Faces and Functions of β-catenin. EMBO J. 31, 2714–2736. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.150

Veeman M. T., Axelrod J. D., Moon R. T. (2003). A Second Canon. Dev. Cell 5, 367–377. doi:10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00266-1

Virtanen E., Junnila M., Soivio A. (1989). Effects of Food Containing Betaine/amino Acid Additive on the Osmotic Adaptation of Young Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. Aquaculture 83, 109–122. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(89)90065-3

Wen C., Chen Y., Leng Z., Ding L., Wang T., Zhou Y. (2019). Dietary Betaine Improves Meat Quality and Oxidative Status of Broilers under Heat Stress. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99, 620–623. doi:10.1002/jsfa.9223

Wu G., Davis D. A. (2005). Interrelationship Among Methionine, Choline, and Betaine in Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus. J. World Aquac. Soc. 36, 337–345.

Zeng L., Fagotto F., Zhang T., Hsu W., Vasicek T. J., Perry W. L., et al. (1997). The Mouse Locus Encodes Axin, an Inhibitor of the Wnt Signaling Pathway that Regulates Embryonic Axis Formation. Cell 90, 181–192. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80324-4

Zhang D., Jing H., Dou C., Zhang L., Wu X., Wu Q., et al. (2018). Supplement of Betaine into Embryo Culture Medium Can Rescue Injury Effect of Ethanol on Mouse Embryo Development. Sci. Rep. 8, 1761. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20175-w

Zhang L., Ying S. J., An W. J., Lian H., Zhou G. B., Han Z. Y. (2014). Effects of Dietary Betaine Supplementation Subjected to Heat Stress on Milk Performances and Physiology Indices in Dairy Cow. Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 7577–7586. doi:10.4238/2014.September.12.25

Zhang M., Wu X., Lai F., Zhang X., Wu H., Min T. (2016). Betaine Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus with an Advantage of Decreasing Resistance to Lamivudine and Interferon α. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 4068–4077. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01180

Zhou Y., Holmseth S., Hua R., Lehre A. C., Olofsson A. M., Poblete-Naredo I., et al. (2012). The Betaine-GABA Transporter (BGT1, Slc6a12) Is Predominantly Expressed in the Liver and at Lower Levels in the Kidneys and at the Brain Surface. Am. J. Physiology-Renal Physiol. 302, F316–F328. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00464.2011

Keywords: betaine, Wnt10b, β-catenin, reactive oxygen species, zebrafish

Citation: Li A, Gu Y, Zhang X, Yu H, Liu D and Pang Q (2022) Betaine Regulates the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species Through Wnt10b Signaling in the Liver of Zebrafish. Front. Physiol. 13:877178. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.877178

Received: 16 February 2022; Accepted: 17 March 2022;

Published: 28 April 2022.

Edited by:

Mohamed Salah Azaza, National Institute of Marine Science and Technology, TunisiaReviewed by:

Ines Ben Khemis, Institut National des Sciences et Technologies de la Mer, TunisiaCopyright © 2022 Li, Gu, Zhang, Yu, Liu and Pang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dongwu Liu, bGl1ZG9uZ3d1QHNkdXQuZWR1LmNu; Qiuxiang Pang, cGFuZ3FpdXhpYW5nQHNkdXQuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.