- Gene Regulation and Metabolism Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

Brown and beige adipocytes are specialized to dissipate energy as heat. Sgk2, encoding a serine/threonine kinase, has been identified as a brown and beige adipocyte-specific gene in rodents and humans; however, its function in brown/beige adipocytes remains unraveled. Here, we examined the regulation and role of Sgk2 in brown/beige adipose tissue thermogenesis. We found that transcriptional coactivators PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α activated by the β3 adrenergic receptor-cAMP-PKA pathway are recruited to the Sgk2 promoter, triggering Sgk2 transcription in response to cold. SGK2 elevation was closely associated with increased serine/threonine phosphorylation of proteins carrying the consensus RxRxxS/T phosphorylation site. However, despite cold-dependent activation of SGK2, mice lacking Sgk2 exhibited normal cold tolerance at 4°C. In addition, Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice induced comparable increases in energy expenditure during pharmacological activation of brown and beige adipose tissue with a β3AR agonist. In vitro loss- and gain-of-function studies further demonstrated that Sgk2 ablation or activation does not alter thermogenic gene expression and mitochondrial respiration in brown adipocytes. Collectively, our results reveal a new signaling component SGK2, although dispensable for cold-induced thermogenesis that adds an additional layer of complexity to the β3AR signaling network in brown/beige adipose tissue.

Introduction

While white adipocytes store energy as triglycerides, brown adipocytes located in interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT) transform the nutrient-derived chemical energy into heat through thermogenic respiration, which requires uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) in the mitochondria (Golozoubova et al., 2001; Nedergaard et al., 2001; Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). Beige adipocytes, an inducible form of thermogenic adipocytes, also emerge within subcutaneous white adipose tissue (WAT) after prolonged exposure to cold or β3-adrenergic receptor (β3AR) agonists (Granneman et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2012). The presence of brown and beige adipocytes in humans has also been established, and their stimulation by cold or β3AR agonists is associated with increased energy expenditure and enhanced disposal of circulating glucose and fatty acids, thus making them an attractive target for the treatment of obesity and diabetes (Cypess et al., 2009, 2013, 2015; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009; Blondin et al., 2020; O’Mara et al., 2020).

Brown and beige adipocytes show similar morphology and function with high expression of several markers such as Ucp1, Cidea, Dio2, Elovl3, Cox7a1, Ppargc1a, and Gyk (Himms-Hagen et al., 1994; Wu et al., 2012). Recently, Sgk2, serum-, and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 2, has been identified as an additional gene preferentially expressed in brown and beige adipocytes (Harms et al., 2014). Sgk2 gene expression is markedly elevated by cold in murine brown and beige adipocytes compared to white adipocytes (Rosell et al., 2014; Perdikari et al., 2018) and its transcripts are also enriched in human supraclavicular BAT compared to subcutaneous WAT (Perdikari et al., 2018; Toth et al., 2020). SGK2 belongs to the SGK serine/threonine kinase family that is highly homologous to the AKT kinase family (Pearce et al., 2010). Both SGK and AKT are activated by signals stimulating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and phosphorylate serine and threonine residues that lie within the consensus RxRxxS/T motifs (Alessi et al., 1996; Kobayashi et al., 1999; Manning and Cantley, 2007; Hemmings and Restuccia, 2012). Although they have overlapping substrates (Brunet et al., 2001; Sakoda et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2007), a growing body of evidence indicates that SGK and AKT are activated under distinct physiological cues, phosphorylate distinct proteins, and have different functions (Sakoda et al., 2003; Lang et al., 2006; Toker and Marmiroli, 2014). Several studies reported that SGK2, like the most studied isoform SGK1, modulates the function of membrane proteins such as Na+/H+ exchanger (Pao et al., 2010), organic anion transporter (Wang et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016), and Na+ channel (Friedrich et al., 2003) in kidney proximal tubule cells. Recent works also indicate that SGK2 plays a role in autophagy (Ranzuglia et al., 2020) and cancer biology supporting tumor progression (Chen et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). However, despite selective expression of SGK2 in brown and beige adipocytes compared to white adipocytes, its function in brown and beige adipocyte thermogenesis has not been examined to date.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the mechanism by which Sgk2 gene expression is upregulated in brown and beige adipocytes and the importance of SGK2 signaling in adaptive thermogenesis during cold stress or β3AR stimulation.

Materials and Methods

Animal Studies

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. Sgk2em1(IMPC)Mbp mice containing heterozygous deletion of the Sgk2 exon 4 were purchased from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers (MMRRC). The heterozygotes were mated to obtain homozygous Sgk2−/− mice and littermate Sgk2+/+ control mice. Genotyping was performed by PCR using ear punch DNA. All mice were housed in standard conditions (22–23°C; 12-h light/12-h dark cycle) and maintained on a regular chow diet (5,001, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) with ad libitum feeding.

For cohort 1, 9-week-old C57BL/6 female mice were randomly assigned to three groups and singly housed at near thermoneutrality (28°C; n=10) or exposed to 4°C for 5h (n=10) and 7days (n=7). For cohort 2, 8-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were randomly assigned to three groups and administered intraperitoneally with vehicle (n=8) or a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist CL316243 (1mg/kg body weight/day) for 5h (n=8) and 7days (n=5) during single-housing at 28°C. For cohort 3, 7-week-old Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− female mice were singly housed at 28°C or exposed to 4°C for 9days (n=6–8 per group). Core rectal temperature was measured at baseline and every 1h over the 8h-period of cold exposure. For cohort 4, 12-week-old Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− male mice (n=8 per genotype) were weighed and their body composition was measured using a Bruker Minispec Mouse Analyzer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA, United States). Mice were then placed in indirect calorimetry chambers (Sable Systems International, North Las Vegas, NV) and monitored for VO2 and VCO2 at 28°C. After 2days in chambers, mice were intraperitoneally injected with CL316243 (1mg/kg body weight/day) for 4days and continuously monitored for VO2 and VCO2. After removing from the chambers, mice were injected with CL316243 for additional 6days.

At the end of experiments, mice from cohorts 1–4 were euthanized to collect brown and inguinal white adipose tissue by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation that is in accordance with the established recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and animal study reporting adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using brown adipose tissue extracted from mice exposed to 4°C for 5h, as described previously (Chang et al., 2012, 2018). The cross-linked nuclear lysates were immunoprecipitated with PGC-1α antibody detecting both PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α or rabbit IgG. PCR was carried out to examine the binding of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α to the ERRE region of the Sgk2 promoter using following primers: 5'-CTATGGAAAGGGGGTGATTT (fwd), 5'-GGACCTTCCGGTTACTCATT (rev).

Brown and Beige Adipocyte Differentiation

For brown adipocytes, interscapular brown adipose tissue was dissected from 4-day-old mice and digested by collagenase type I. Stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells were collected by centrifugation at 700× g for 10min and cell suspension was filtered through a 50–70μm cell strainer. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended and seeded in complete DMEM medium, followed by immortalization with the retrovirus expressing SV40T antigen as described previously (Uldry et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). After selection with 1μg/ml of puromycin, the immortalized brown preadipocytes were grown to confluence in complete DMEM medium and incubated for 48h in induction medium containing 20nM insulin, 1nMT3, 0.5mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 0.5μM dexamethasone, and 0.125mM indomethacin (Chang et al., 2010; Jun et al., 2014). Thereafter, the cells were maintained in differentiation medium containing 20nM insulin and 1nMT3 until day 7.

For beige adipocytes, the subcutaneous inguinal fat pad was dissected from 5-week-old mice and it was minced and digested with collagenase D and diapase II. SVF cells were then isolated as described above and previously (Aune et al., 2013). SVF cells were grown to confluence in complete DMEM medium and incubated for 48h in induction medium containing 5μg/ml insulin, 1nMT3, 0.5mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 5μM dexamethasone, 0.125mM indomethacin, and 0.5μM rosiglitazone, as described previously (Aune et al., 2013). Thereafter, cells were maintained in differentiation medium containing 5μg/ml insulin and 1nMT3 with 0.5μM rosiglitazone for 2days and 1μM rosiglitazone for 4days.

Retrovirus Production and Infection

A retroviral pBABE-Sgk2-S356D plasmid was generated by subcloning a BamHI/XhoI-fragment of pcDNA3.1-Sgk2-S356D (Pao et al., 2010) into the BamHI/SalI sites of pBABE-neo (Addgene, Watertown, MA). Retrovirus expressing Sgk2-S356D was produced from GP-293 cells by co-transfecting pBABE-Sgk2-S356D with pVSV-G as described previously (Chang et al., 2010). Immortalized brown preadipocytes were then infected in retrovirus-containing medium supplemented with 8μg/ml of polybrene for 8h. After 48h, neomycin-resistant clones were selected and pooled.

Cellular O2 Consumption Rates

Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) of differentiated brown adipocytes were monitored using an Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) as described previously (Jun et al., 2014). Briefly, cells were placed in a magnetically stirred respirometric chamber containing the culture medium. OCR measurements were obtained at baseline and after injection of oligomycin, FCCP and antimycin A. The value of basal, leak, and maximal mitochondrial respiration was determined by subtracting non-mitochondrial respiration as described in the Oroboros Operator’s Manual.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from tissues or cells by homogenization in lysis buffer (Chang et al., 2010) and subjected to Western blot analysis using the following antibodies: anti-SGK2 (#5595), anti-phospho-AKT S473 (#9271), anti-AKT (#9272), anti-phospho-RxRxxS/T (#10001), anti-phospho-GSK3α/β (#9331), anti-GSK3α/β (#5676; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and anti-β actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA from tissues or cells was reverse-transcribed for quantitative real-time PCR analysis as described previously (Chang et al., 2010, 2012). Gene expression analysis was carried out using the Applied Biosystems 7900 (Applied Biosystems) and iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Relative mRNA expression of the genes of interest was determined using gene-specific primers after normalization to cyclophilin by the 2-ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences were obtained from the PrimerBank public resource (Wang and Seed, 2003). Sgk2 fwd: 5'- CCAATGGGAACATCAACC-3'; Sgk2 rev: 5'-CAGTAGGACCTTCCCGTAGT-3'.

Statistical Analysis

All line and bar graphs were created by using the Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) and student t test or two-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences between groups using the Prism 6 software. Data are presented as mean±SEM. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sgk2 Gene Expression Is Elevated by Cold-Stimulated β-Adrenergic Signaling in Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue

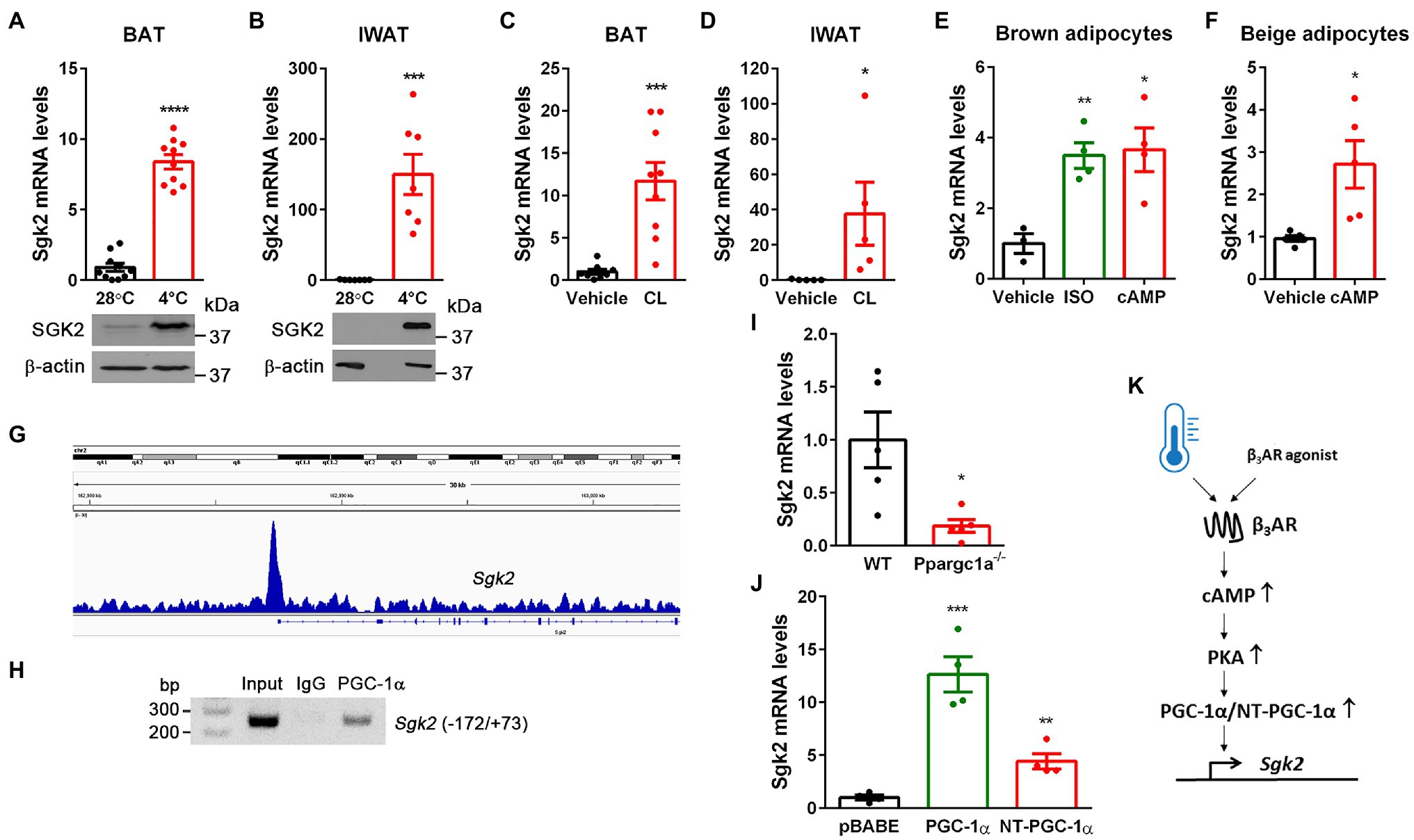

Previous genome-wide transcriptome analyses revealed enrichment of Sgk2 transcripts in cold-activated brown and beige adipocytes compared to white adipocytes in rodents and humans (Rosell et al., 2014; Perdikari et al., 2018; Toth et al., 2020). Indeed, acute cold exposure significantly elevated Sgk2 mRNA and protein levels in BAT (Figure 1A). Similarly, the Sgk2 mRNA and protein levels were markedly induced in inguinal WAT undergoing browning during prolonged cold exposure, although they are barely detectable in IWAT of mice housed at 28°C (Figure 1B). In addition, pharmacological stimulation of BAT and IWAT by a β3AR agonist CL316243 (Himms-Hagen et al., 1994, 2000; Granneman et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2012) mimicked the effect of cold on Sgk2 gene expression (Figures 1C,D). To further confirm the direct effect of βAR signaling on Sgk2 gene expression in brown and beige adipocytes, we differentiated brown preadipocytes (Uldry et al., 2006; Jun et al., 2014) into brown adipocytes and treated with a βAR agonist isoproterenol or a cell-permeable cAMP analog dibutyryl cAMP, which mimics the main intracellular regulatory mechanism activated by βAR stimulation. In line with in vivo data, isoproterenol and dibutyryl cAMP significantly increased Sgk2 gene expression in brown adipocytes (Figure 1E). Similarly, differentiation of stromal vascular cells isolated from IWAT into beige adipocytes and subsequent treatment with dibutyryl cAMP increased Sgk2 gene expression in beige adipocytes (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. Cold- and CL316243-dependent upregulation of Sgk2 gene expression is mediated by PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α. (A) Effect of cold on Sgk2 mRNA and protein levels in BAT. 9-week-old BL6 female mice were housed at 28°C (n=10) or exposed to 4°C for 5h (n=10). (B) Effect of cold on Sgk2 mRNA and protein levels in IWAT. 9-week-old BL6 female mice were housed at 28°C (n=7) or exposed to 4°C for 7days (n=7). (C) Effect of β3AR stimulation on Sgk2 expression in BAT. 8-week-old BL6 male mice were administered with vehicle (n=8) or a β3AR agonist CL316243 (n=8) for 5h. (D) Effect of β3AR stimulation on Sgk2 expression in IWAT. 8-week-old BL6 male mice were administered with vehicle (n=5) or CL316243 (n=5) for 7days. (E) Upregulation of Sgk2 expression by a βAR agonist or cAMP in brown adipocytes. Differentiated brown adipocytes (7days) were treated with vehicle, isoproterenol (5μM) or dibutyryl cAMP (0.5mM) for 4h (n=4 per group). (F) Upregulation of Sgk2 expression by cAMP in primary beige adipocytes. Differentiated beige adipocytes (7days) were treated with vehicle or dibutyryl cAMP (0.5mM) for 4h (n=5 per group). (G) Enrichment of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α on the Sgk2 promoter in cold-activated BAT. The PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α ChIP-seq peak (Chang et al., 2018) was visualized by the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v2.3. (H) PCR analysis of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α recruitment to the ERRE of the Sgk2 promoter. ChIP was carried out with PGC-1α antibody (Chang et al., 2018) in nuclear extracts of BAT isolated from mice exposed to 4°C for 5h. (I) Decreased induction of Sgk2 expression in Ppargc1a −/− brown adipocytes treated with dibutyryl cAMP (n=5 per group). (J) PGC-1α- and NT-PGC-1α-dependent upregulation of Sgk2 expression in Ppargc1a −/− brown adipocytes (n=4 per group). (K) Schematic presentation of transcriptional regulation of Sgk2 by cold or β3AR agonist. All data are presented as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 determined by Student’s t test.

Cold-Induced Transcriptional Coactivators, PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α, Promote Sgk2 Gene Expression

Stimulation of βAR in brown adipocytes signals through coupling to G-proteins, adenylyl cyclase, and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn activates CREB transcription factor, leading to increased Ppargc1a gene expression (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). We previously showed that the Ppargc1a gene produces a full-length PGC-1α and a shorter isoform NT-PGC-1α that are key transcriptional regulators of cold-induced thermogenesis in BAT (Zhang et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2010, 2012; Chang and Ha, 2017). Interestingly, our genome-wide analysis of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α binding in BAT by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq; Chang et al., 2018) revealed enrichment of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α on the Sgk2 gene promoter that contains an estrogen-related receptor (ERR) response element (ERRE; Figure 1G). To confirm this finding, we carried an independent ChIP assay with PGC-1α antibody recognizing both PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α (Chang et al., 2018). Indeed, PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α were recruited to the ERRE region of the Sgk2 gene promoter in cold-activated BAT (Figure 1H).

Next, to examine whether PGC-1α and/or NT-PGC-1α regulate Sgk2 gene expression, we used loss- and gain-of-function approaches. Ablation of both PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α (Ppargc1a −/−) in brown adipocytes blunted Sgk2 gene expression (Uldry et al., 2006; Jun et al., 2014; Figure 1I). Conversely, expression of either PGC-1α or NT-PGC-1α in Ppargc1a −/− brown adipocytes efficiently restored Sgk2 gene expression with a more pronounced effect by PGC-1α (Figure 1J). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that Sgk2 gene expression is upregulated by the well-established β3AR-cAMP-PKA-PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α pathway (Figure 1K).

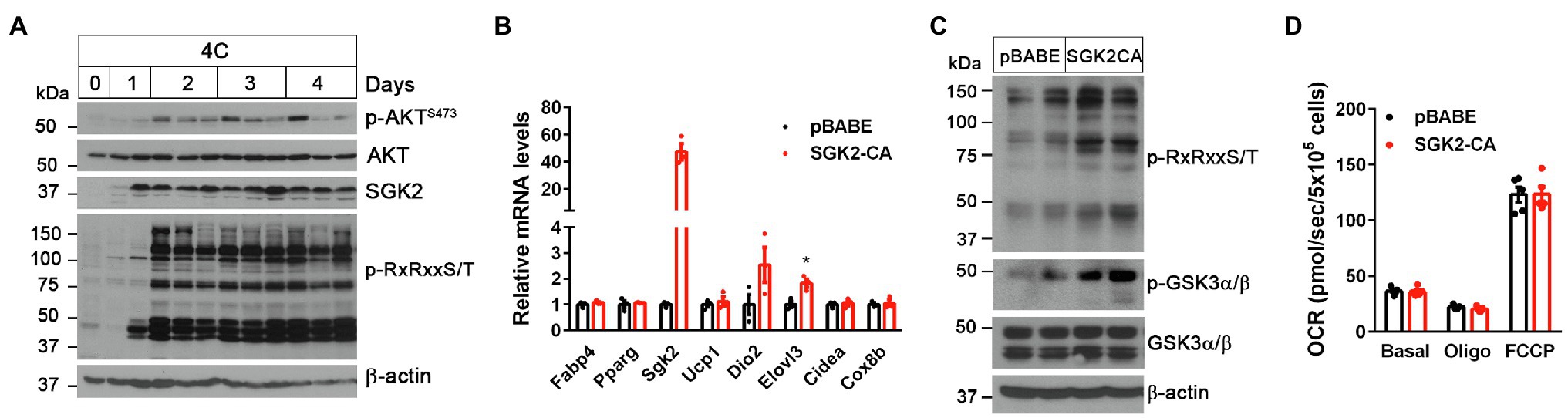

SGK2 Activation Induces Phosphorylation of Its Downstream Substrates Containing RxRxxS/T Motifs in Brown Adipocytes but Is Not Sufficient to Enhance Thermogenesis

SGK2 belongs to the SGK kinase family that is closely related to the AKT serine/threonine kinase (Pearce et al., 2010). Both SGK and ATK phosphorylate serine and threonine residues that lie within the consensus RxRxxS/T motifs (Alessi et al., 1996; Kobayashi et al., 1999; Manning and Cantley, 2007; Hemmings and Restuccia, 2012). During cold stress, AKT protein levels remained unchanged in BAT but its activity increased by cold, as reflected by mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of AKT on Ser473 in the C-terminal hydrophobic motif (Sarbassov et al., 2005; Albert et al., 2016; Figure 2A). In contrast to AKT, SGK2 protein levels were markedly elevated by cold in BAT. We were not able to assess its activity due to lack of SGK2 antibody detecting phosphorylation on Ser356 that is equivalent to the C-terminal phosphorylation site of AKT (Kobayashi et al., 1999; Pao et al., 2010). However, cold-induced phosphorylation of proteins carrying RxRxxS/T motifs was more closely associated with SGK2 protein levels rather than AKT activity (Figure 2A), suggesting that cold-induced SGK2 is an active serine/threonine kinase in BAT.

Figure 2. SGK2 activation induces phosphorylation of downstream substrates in brown adipocytes. (A) Cold-dependent activation of SGK2 signaling in BAT. 9-week old BL6 mice were exposed to 4°C for indicated times. (B) No change in expression of genes involved in brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis by SGK2 activation. Brown preadipocytes were transduced with retrovirus expressing an empty vector or SGK2-S356D, followed by differentiation into brown adipocytes for 7days (n=3 per group). (C) Effect of SGK2 activation on downstream signaling in brown adipocytes starved for serum for 8h. (D) Effect of SGK2 activation on mitochondrial respiration in brown adipocytes. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured in differentiated brown adipocytes (7days) at baseline and after addition of oligomycin and FCCP (n=5 per group). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 determined by Student’s t test.

To test if SGK2 phosphorylates its downstream targets in brown adipocytes, we expressed a constitutively active form of SGK2 (SGK2-S356D; Kobayashi et al., 1999; Pao et al., 2010) in brown adipocytes and examined changes in RxRxxS/T phosphorylation status in the absence of βAR stimulation. SGK2 activation did not alter brown adipogenesis, as evidenced by comparable expression of adipogenic marker genes (Fabp4 and Ppparg) and brown adipocyte-enriched genes (Ucp1, Dio2, Elovl3, Cidea, and Cox8b) between the groups (Figure 2B). As expected, SGK2-CA led to increased phosphorylation of its substrates carrying RxRxxS/T motifs in the absence of βAR signaling (Figure 2C). A recent study reported that cold exposure and β-adrenergic stimulation cause phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase, in a PKA-dependent manner, leading to inhibition of its negative effect on the MKK3/6-p38 MAPK-ATF2 signaling pathway downstream of β3AR (Markussen et al., 2018). Given that GSK3 isoforms α and β are the well-known AKT/SGK targets (Cross et al., 1995; Sakoda et al., 2003), we examined whether SGK2-CA phosphorylates GSK3α and GSK3β on serine residues in RARTTS21 and RPRTTS9, respectively (Cross et al., 1995; Sakoda et al., 2003), in brown adipocytes. Indeed, SGK2-CA increased phosphorylation of GSK3 with a more pronounced effect on GSK3α (51kDa; Figure 2C), suggesting that SGK2 induced by the βAR-PKA-PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α pathway could participate in phosphorylation and inhibition of GSK3α, which is a negative regulator of βAR signaling in BAT.

Next, we examined whether SGK2 activation enhances thermogenic activity in brown adipocytes by measuring mitochondrial respiration. Mitochondrial respiration by the electron transport chain (ETC) is critical for UCP1-mediated thermogenesis (Golozoubova et al., 2001; Nedergaard et al., 2001). The ETC creates a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane and UCP1 subsequently allows protons to return to the mitochondrial matrix, resulting in heat production (Golozoubova et al., 2001; Nedergaard et al., 2001). Despite increased phosphorylation of its downstream substrates including GSK3, SGK2 activation did not lead to an increase in mitochondrial respiration (Figure 2D). Oligomycin-insensitive leak respiration, which in part represents UCP1-mediated thermogenesis, and FCCP-induced maximum respiration were also comparable between the groups. It is likely that GSK3 inhibition itself by SGK2, without activation of βAR signaling, has no effect on thermogenic activity. Thus, these results indicate that activation of SGK2 alone is not sufficient to promote brown adipocyte thermogenesis.

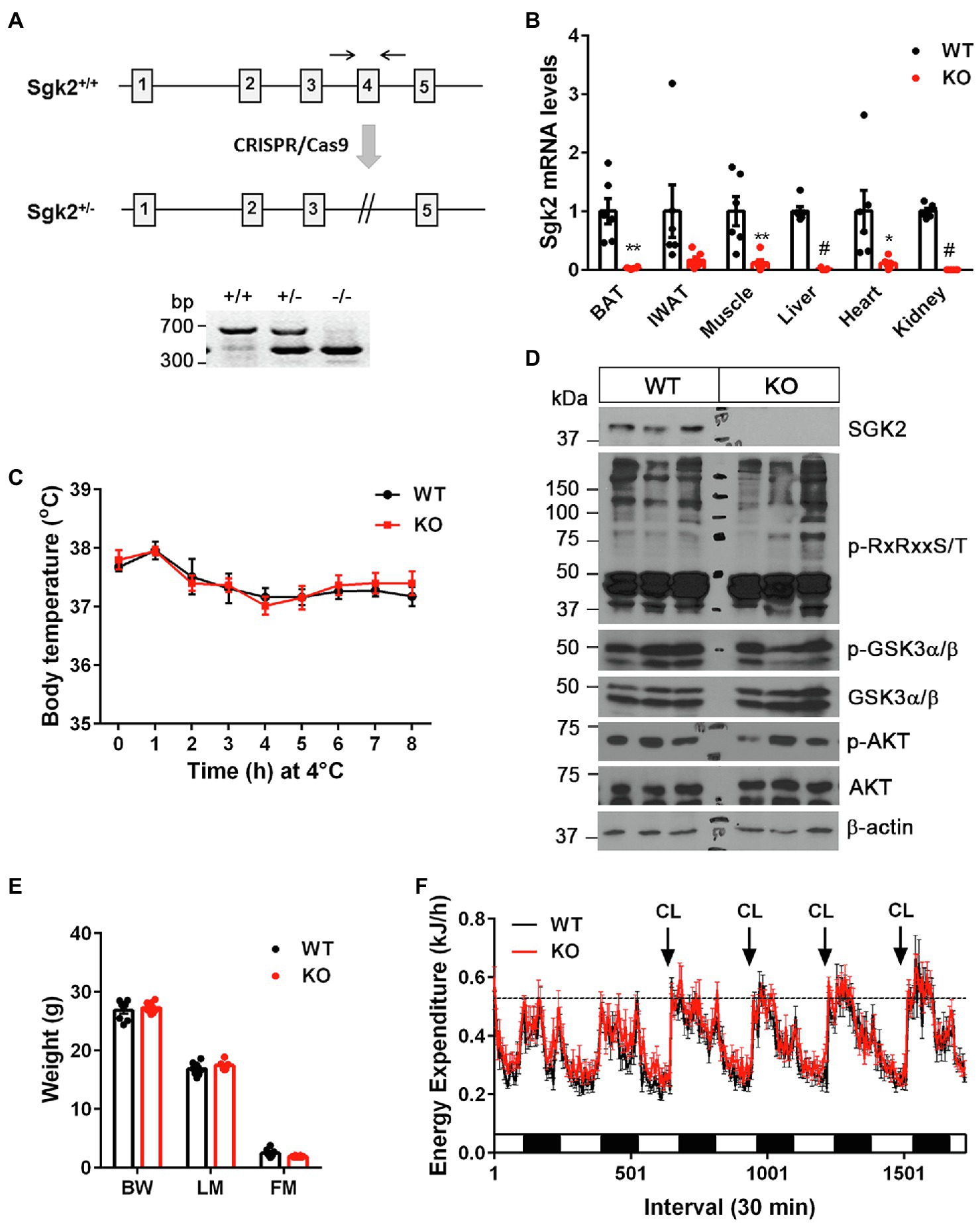

SGK2 Is Dispensable for Cold- and β3AR Agonist-Stimulated Thermogenesis

To investigate whether cold-induced SGK2 is required for cold-stimulated thermogenesis, we generated Sgk2−/− mice by mating heterozygous Sgk2em1(IMPC)Mbp mice containing deletion of the Sgk2 exon 4. The phenotype of Sgk2−/− mice has not been characterized to date. The mutant allele was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated form Sgk2+/+, Sgk2+/−, and Sgk2−/− mice (Figure 3A). The efficacy of gene targeting was further examined by qPCR analysis. As expected, Sgk2 transcripts were absent in all tissues including BAT, IWAT, muscle, liver, heart and kidney of Sgk2−/− mice (Figure 3B), clearly demonstrating the loss of Sgk2. Next, we exposed Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− female mice to 4°C for 8h and measured core body temperature to determine the effect of Sgk2 ablation on cold-induced thermogenesis. Despite marked elevation of SGK2 by cold, mice lacking Sgk2 were able to maintain body temperature during cold exposure (Figure 3C). Further analysis of cold-activated BAT revealed no changes in phosphorylation status of RxRxxS/T-containing proteins by Sgk2 ablation (Figure 3D). In addition, phosphorylation levels of GSK3α on Ser21 were relatively comparable in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− BAT, implying that other kinases are able to replace SGK2 function in cold-activated BAT.

Figure 3. Sgk2 ablation had no effect on cold- and CL316243-stimulated thermogenesis. (A) Generation of Sgk2 knockout mice. Top panel, a region of the mouse Sgk2 gene containing exons 1–5. The exon 4 was targeted for deletion by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Bottom panel, PCR analysis of ear punch samples from Sgk2+/+, Sgk2+/−, and Sgk2−/− mice using a primer pair described as two arrows. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis for detection of Sgk2 transcripts in Sgk2+/+ (WT) and Sgk2−/− (KO) female mice (n=6 per group). For IWAT, tissue samples were dissected from mice exposed to 4°C for 9days (n=6 per group). Data are presented as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, #p<0.0001 determined by Student’s t test. (C) Body temperature of 7-week-old Sgk2+/+ (n=8) and Sgk2−/− (n=6) female mice during 8h of cold exposure. Core body temperature were measured using a rectal thermometer at indicated times. (D) Western blot analysis of BAT dissected from 8-week-old Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− female mice exposed to 4°C for 9days. (E) Body weight (BW), lean mass (LM) and fat mass (FM) of 12-week-old Sgk2+/+ (n=8) and Sgk2−/− (n=8) male mice. (F) Energy expenditure of 12-week-old Sgk2+/+ (n=8) and Sgk2−/− (n=8) male mice prior to and during administration of a β3AR agonist CL316243.

To rule out the possibility that increased muscle shivering contributes to the thermoregulation of Sgk2−/− mice during cold exposure, we placed Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− male mice in indirect calorimetric chambers at thermoneutral temperature (28°C) and measured energy expenditure during pharmacological stimulation of brown and beige adipose tissue with a highly selective β3AR agonist CL316243. CL316243-dependent increases in energy expenditure represent brown and beige adipose thermogenesis (Himms-Hagen et al., 1994, 2000; Granneman et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2012). At 12weeks of age, Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice exhibited similar body weights and composition (Figure 3E). In addition, energy expenditure was comparable between Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice prior to introduction of the agonist (Figure 3F). Daily administration of CL316243 for 4days produced comparable increases in energy expenditure in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice (Figure 3F), indicating that SGK2 is not required for CL316243-stimulated thermogenesis in brown and beige adipose tissue. The thermogenic response of Sgk2−/− mice to physiological (cold) or pharmacological (β3AR agonist) stimulation was same regardless of the distinct use of sex of mice (Figures 3C,F). Locomotor activity and food intake over the 6-day period did not differ between the genotypes (Supplementary Figures 1A,B). It is well documented that CL316243-mediated activation of brown and beige adipose tissue upregulates genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, thermogenesis, mitochondrial electron transport activity, fatty acid oxidation, lipid metabolism, and glucose metabolism (Yu et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2012; Mottillo et al., 2014; Hao et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018). Thus, we examined the gene expression profiles of BAT and IWAT from Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice treated with CL316243 for 10days. In line with energy expenditure results, CL316243-induced gene expression was comparable in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice (Supplementary Figures 1C,D), demonstrating that SGK2 signaling is dispensable for CL316243-induced remodeling of brown and beige adipose tissue.

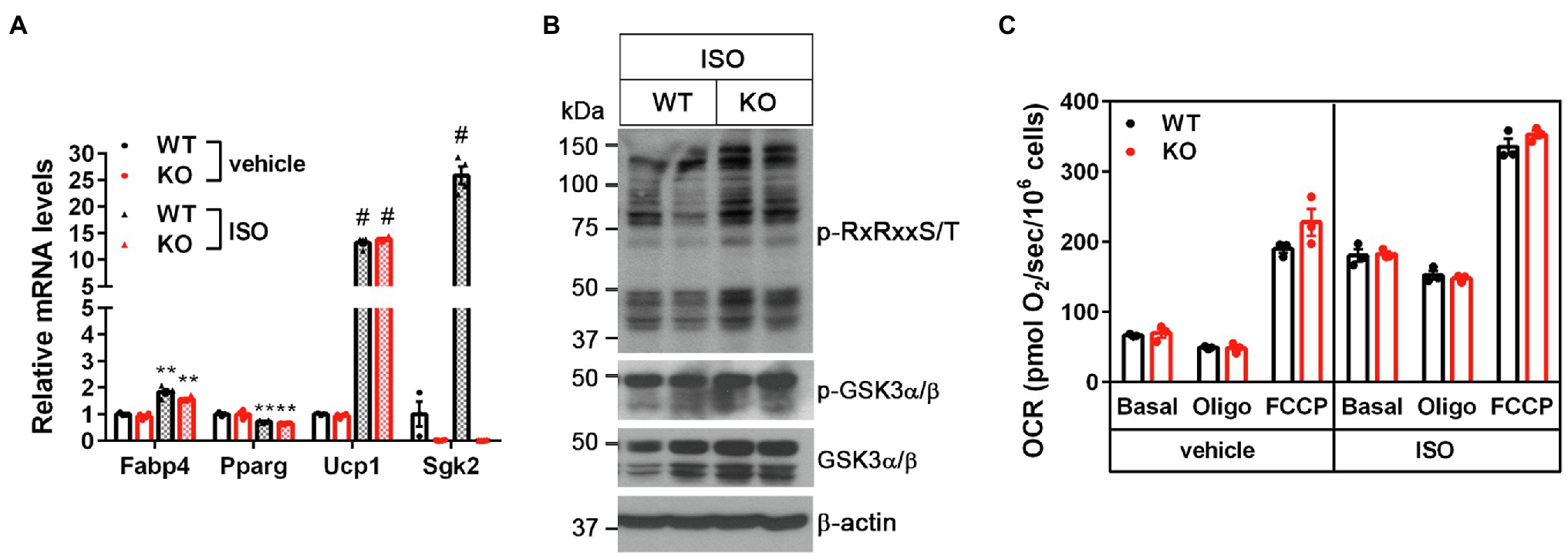

Loss of SGK2 Activity in Brown Adipocytes Has No Effect on Mitochondrial Respiration and Thermogenesis

To further determine the cell-autonomous effect of Sgk2 ablation in brown adipocytes, we isolated stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells from BAT of Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− mice and induced differentiation of immortalized brown preadipocytes into brown adipocytes. Brown adipogenesis was not affected by Sgk2 ablation, as evidenced by similar mRNA expression of Fabp4, Pparg, and Ucp1 in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− brown adipocytes (Figure 4A). Sgk2 ablation in brown adipocytes did not lead to decreased serine/threonine phosphorylation of RxRxxS/T-containing proteins in response to βAR stimulation (Figure 4B). Rather, serine/threonine phosphorylation levels were slightly higher in Sgk2−/− brown adipocytes (Figure 4B). In addition, GSK3α phosphorylation levels were not altered by Sgk2 ablation. Next, we assessed thermogenic activity of Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− brown adipocytes by measuring isoproterenol-stimulated mitochondrial respiration. Isoproterenol produced a comparable increase in mitochondrial respiration in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− brown adipocytes (Figure 4C). Leak respiration, which in part represents UCP1-mediated thermogenesis, and FCCP-induced maximum respiration were also comparable in Sgk2+/+ and Sgk2−/− brown adipocytes. Taken together, these results demonstrate that SGK2 activity is dispensable for βAR-stimulated mitochondrial respiration and thermogenesis. Given the same effect of Sgk2 ablation on thermogenesis in mice and cells, it is not likely that immortalization is affecting the data on the role of Sgk2 in brown adipocytes.

Figure 4. Sgk2 ablation does not alter βAR-stimulated mitochondrial respiration in brown adipocytes. (A) No change in brown adipogenesis by Sgk2 ablation. Sgk2+/+ (WT) and Sgk2−/− (KO) brown preadipocytes were differentiated into brown adipocytes for 7days and treated with or without isoproterenol for 4h (n=3–4 per group). (B) Effect of Sgk2 ablation on downstream signaling in isoproterenol-stimulated brown adipocytes. (C) Effect of Sgk2 ablation on mitochondrial respiration in differentiated brown adipocytes (7days) in the absence and presence of βAR stimulation. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured at baseline and after addition of oligomycin and FCCP (n=4 per group). All data are presented as the mean±SEM. **p<0.01, #p<0.0001 determined by Student’s t test.

Discussion

Sgk2 is a BAT-enriched gene that is highly expressed in cold-activated brown and beige adipocytes in rodents and humans (Harms et al., 2014; Rosell et al., 2014; Perdikari et al., 2018; Toth et al., 2020). The present study clearly delineates that Sgk2 gene expression is upregulated by PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α that are recruited to the ERRE of the Sgk2 promoter upon cold exposure. ERRα and ERRγ have been shown to bind on the Sgk2 promoter, triggering its transcription in the kidney (Tremblay et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2018). Given the ability of PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α to coactivate ERRs in BAT (Huss et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2012), we postulate that cold-induced PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α activate ERRs bound to the ERRE of the Sgk2 promoter, leading to increased expression of Sgk2 in cold-activated brown and beige adipose tissue.

Despite marked elevation of SGK2 in brown and beige adipose tissue by cold or β3AR agonists, mice lacking Sgk2 showed the normal ability to increase brown and beige adipose thermogenesis during cold exposure or β3AR stimulation. In vitro loss- and gain-of-function studies further demonstrated that Sgk2 ablation or activation does not alter mitochondrial respiration and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. These findings indicate that SGK2 signaling is not directly involved in promoting brown/beige adipose thermogenesis. However, GSK3 phosphorylation by SGK2 in part suggests its indirect role in regulating brown/beige adipose thermogenesis. Phosphorylation of GSK3 by cold or β3AR stimulation has been shown to inhibit its negative effect on the MKK3/6-p38 MAPK-ATF2 signaling pathway downstream of β3AR, leading to enhanced thermogenic gene expression in BAT (Markussen et al., 2018). Thus, cold-induced SGK2 may participate in the suppression of GSK3 activity, along with AKT (Cross et al., 1995) and PKA (Fang et al., 2000), although its contribution seems small because Sgk2 ablation resulted in no change in GSK3 phosphorylation levels in cold-activated BAT.

Several studies reported that Na+ influx is increased in brown adipocytes during the norepinephrine/βAR-stimulated depolarization (Girardier and Schneider-Picard, 1983; Connolly et al., 1986) although its physiological significance remains to be elucidated. Given the role of SGK2 in modulating Na+ channels in kidney cells (Friedrich et al., 2003; Pao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016), it would be interesting to determine if SGK2 regulates Na+ influx in brown/beige adipocytes during the βAR-stimulated depolarization.

In summary, our findings illustrate a new signaling component, SGK2, that adds an additional layer of complexity to the β3AR signaling network in brown/beige adipose tissue although it is dispensable for cold-induced thermogenesis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: (NCBI)’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE110056).

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Author Contributions

C-HP, JM, MP, HC, and JL carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. JSC conceived of the presented idea, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NIH R01DK104748 (JSC) and COBRE (NIH8 1P30GM118430-01). This work used the Genomics Core and Cell Biology and Bioimaging Core that are supported in part by COBRE (NIH8 1P30GM118430-01) and NORC (NIH P30-DK072476) center grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan C. Pao (Stanford University) and Bruce Spiegelman (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) for providing the pcDNA3.1-Sgk2-S356D plasmid and Ppargc1a-/- brown preadipocytes, respectively.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.780312/full#supplementary-material

References

Albert, V., Svensson, K., Shimobayashi, M., Colombi, M., Munoz, S., Jimenez, V., et al. (2016). mTORC2 sustains thermogenesis via Akt-induced glucose uptake and glycolysis in brown adipose tissue. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 232–246. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505610

Alessi, D. R., Caudwell, F. B., Andjelkovic, M., Hemmings, B. A., and Cohen, P. (1996). Molecular basis for the substrate specificity of protein kinase B; comparison with MAPKAP kinase-1 and p70 S6 kinase. FEBS Lett. 399, 333–338. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01370-1

Aune, U. L., Ruiz, L., and Kajimura, S. (2013). Isolation and differentiation of stromal vascular cells to beige/brite cells. J. Vis. Exp. 50191. doi: 10.3791/50191

Blondin, D. P., Nielsen, S., Kuipers, E. N., Severinsen, M. C., Jensen, V. H., Miard, S., et al. (2020). Human brown adipocyte thermogenesis is driven by beta2-AR stimulation. Cell Metab. 32, 287.e287–300.e287. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.005

Brunet, A., Park, J., Tran, H., Hu, L. S., Hemmings, B. A., and Greenberg, M. E. (2001). Protein kinase SGK mediates survival signals by phosphorylating the forkhead transcription factor FKHRL1 (FOXO3a). Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 952–965. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.952-965.2001

Cannon, B., and Nedergaard, J. (2004). Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003

Chang, J. S., Fernand, V., Zhang, Y., Shin, J., Jun, H. J., Joshi, Y., et al. (2012). NT-PGC-1alpha protein is sufficient to link beta3-adrenergic receptor activation to transcriptional and physiological components of adaptive thermogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9100–9111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320200

Chang, J. S., Ghosh, S., Newman, S., and Salbaum, J. M. (2018). A map of the PGC-1alpha- and NT-PGC-1alpha-regulated transcriptional network in brown adipose tissue. Sci. Rep. 8:7876. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36162-0

Chang, J. S., and Ha, K. (2017). An unexpected role for the transcriptional coactivator isoform NT-PGC-1alpha in the regulation of mitochondrial respiration in brown adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 9958–9966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.778373

Chang, J. S., Huypens, P., Zhang, Y., Black, C., Kralli, A., and Gettys, T. W. (2010). Regulation of NT-PGC-1alpha subcellular localization and function by protein kinase A-dependent modulation of nuclear export by CRM1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18039–18050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083121

Chen, J. B., Zhang, M., Zhang, X. L., Cui, Y., Liu, P. H., Hu, J., et al. (2018). Glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 2 promotes bladder cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion by enhancing beta-catenin/c-Myc signaling pathway. J. Cancer 9, 4774–4782. doi: 10.7150/jca.25811

Connolly, E., Nanberg, E., and Nedergaard, J. (1986). Norepinephrine-induced Na+ influx in brown adipocytes is cyclic AMP-mediated. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 14377–14385. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)66880-2

Cross, D. A., Alessi, D. R., Cohen, P., Andjelkovich, M., and Hemmings, B. A. (1995). Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378, 785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0

Cypess, A. M., Lehman, S., Williams, G., Tal, I., Rodman, D., Goldfine, A. B., et al. (2009). Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780

Cypess, A. M., Weiner, L. S., Roberts-Toler, C., Franquet Elia, E., Kessler, S. H., Kahn, P. A., et al. (2015). Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metab. 21, 33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.009

Cypess, A. M., White, A. P., Vernochet, C., Schulz, T. J., Xue, R., Sass, C. A., et al. (2013). Anatomical localization, gene expression profiling and functional characterization of adult human neck brown fat. Nat. Med. 19, 635–639. doi: 10.1038/nm.3112

Fang, X., Yu, S. X., Lu, Y., Bast, R. C. Jr., Woodgett, J. R., and Mills, G. B. (2000). Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 11960–11965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220413597

Friedrich, B., Feng, Y., Cohen, P., Risler, T., Vandewalle, A., Broer, S., et al. (2003). The serine/threonine kinases SGK2 and SGK3 are potent stimulators of the epithelial Na+ channel alpha,beta,gamma-ENaC. Pflugers Arch. 445, 693–696. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0993-8

Girardier, L., and Schneider-Picard, G. (1983). Alpha and beta-adrenergic mediation of membrane potential changes and metabolism in rat brown adipose tissue. J. Physiol. 335, 629–641. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014555

Golozoubova, V., Hohtola, E., Matthias, A., Jacobsson, A., Cannon, B., and Nedergaard, J. (2001). Only UCP1 can mediate adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis in the cold. FASEB J. 15, 2048–2050. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0536fje

Granneman, J. G., Li, P., Zhu, Z., and Lu, Y. (2005). Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue I: effects of beta3-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E608–E616. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00009.2005

Hao, Q., Yadav, R., Basse, A. L., Petersen, S., Sonne, S. B., Rasmussen, S., et al. (2015). Transcriptome profiling of brown adipose tissue during cold exposure reveals extensive regulation of glucose metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 308, E380–E392. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00277.2014

Harms, M. J., Ishibashi, J., Wang, W., Lim, H. W., Goyama, S., Sato, T., et al. (2014). Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab. 19, 593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.007

Hemmings, B. A., and Restuccia, D. F. (2012). PI3K-PKB/Akt pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4:a011189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011189

Himms-Hagen, J., Cui, J., Danforth, E. Jr., Taatjes, D. J., Lang, S. S., Waters, B. L., et al. (1994). Effect of CL-316,243, a thermogenic beta 3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. Am. J. Phys. 266, R1371–R1382. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1371

Himms-Hagen, J., Melnyk, A., Zingaretti, M. C., Ceresi, E., Barbatelli, G., and Cinti, S. (2000). Multilocular fat cells in WAT of CL-316243-treated rats derive directly from white adipocytes. Am. J. Phys. Cell Physiol. 279, C670–C681. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C670

Huss, J. M., Kopp, R. P., and Kelly, D. P. (2002). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) coactivates the cardiac-enriched nuclear receptors estrogen-related receptor-alpha and -gamma. Identification of novel leucine-rich interaction motif within PGC-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40265–40274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206324200

Jun, H. J., Joshi, Y., Patil, Y., Noland, R. C., and Chang, J. S. (2014). NT-PGC-1alpha activation attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity by enhancing brown fat thermogenesis and adipose tissue oxidative metabolism. Diabetes 63, 3615–3625. doi: 10.2337/db13-1837

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M., and Altman, D. G. (2010). Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412

Kim, J., Park, M. S., Ha, K., Park, C., Lee, J., Mynatt, R. L., et al. (2018). NT-PGC-1alpha deficiency decreases mitochondrial FA oxidation in brown adipose tissue and alters substrate utilization in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 59, 1660–1670. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M085647

Kobayashi, T., Deak, M., Morrice, N., and Cohen, P. (1999). Characterization of the structure and regulation of two novel isoforms of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase. Biochem. J. 344, 189–197. doi: 10.1042/bj3440189

Lang, F., Bohmer, C., Palmada, M., Seebohm, G., Strutz-Seebohm, N., and Vallon, V. (2006). (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1151–1178. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00050.2005

Lee, I. H., Dinudom, A., Sanchez-Perez, A., Kumar, S., and Cook, D. I. (2007). Akt mediates the effect of insulin on epithelial sodium channels by inhibiting Nedd4-2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29866–29873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701923200

Lin, J., Handschin, C., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2005). Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 1, 361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004

Liu, Y., Chen, J. B., Zhang, M., Zhang, X. L., Meng, J. L., Zhou, J., et al. (2019). SGK2 promotes renal cancer progression via enhancing ERK 1/2 and AKT phosphorylation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 2756–2767. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201904_17549

Manning, B. D., and Cantley, L. C. (2007). AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell 129, 1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009

Markussen, L. K., Winther, S., Wicksteed, B., and Hansen, J. B. (2018). GSK3 is a negative regulator of the thermogenic program in brown adipocytes. Sci. Rep. 8:3469. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21795-y

Mottillo, E. P., Balasubramanian, P., Lee, Y. H., Weng, C., Kershaw, E. E., and Granneman, J. G. (2014). Coupling of lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis in brown, beige, and white adipose tissues during chronic beta3-adrenergic receptor activation. J. Lipid Res. 55, 2276–2286. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M050005

Nedergaard, J., Golozoubova, V., Matthias, A., Asadi, A., Jacobsson, A., and Cannon, B. (2001). UCP1: the only protein able to mediate adaptive non-shivering thermogenesis and metabolic inefficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1504, 82–106. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00247-4

O’mara, A. E., Johnson, J. W., Linderman, J. D., Brychta, R. J., Mcgehee, S., Fletcher, L. A., et al. (2020). Chronic mirabegron treatment increases human brown fat, HDL cholesterol, and insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2209–2219. doi: 10.1172/JCI131126

Pao, A. C., Bhargava, A., Di Sole, F., Quigley, R., Shao, X., Wang, J., et al. (2010). Expression and role of serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 2 in the regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in the mammalian kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 299, F1496–F1506. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00075.2010

Pearce, L. R., Komander, D., and Alessi, D. R. (2010). The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2822

Perdikari, A., Leparc, G. G., Balaz, M., Pires, N. D., Lidell, M. E., Sun, W., et al. (2018). BATLAS: deconvoluting brown adipose tissue. Cell Rep. 25, 784.e784–797.e784. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.044

Ranzuglia, V., Lorenzon, I., Pellarin, I., Sonego, M., Dall’acqua, A., D’andrea, S., et al. (2020). Serum- and glucocorticoid- inducible kinase 2, SGK2, is a novel autophagy regulator and modulates platinum drugs response in cancer cells. Oncogene 39, 6370–6386. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01433-6

Rosell, M., Kaforou, M., Frontini, A., Okolo, A., Chan, Y. W., Nikolopoulou, E., et al. (2014). Brown and white adipose tissues: intrinsic differences in gene expression and response to cold exposure in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 306, E945–E964. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00473.2013

Sakoda, H., Gotoh, Y., Katagiri, H., Kurokawa, M., Ono, H., Onishi, Y., et al. (2003). Differing roles of Akt and serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase in glucose metabolism, DNA synthesis, and oncogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25802–25807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301127200

Sarbassov, D. D., Guertin, D. A., Ali, S. M., and Sabatini, D. M. (2005). Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307, 1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148

Toker, A., and Marmiroli, S. (2014). Signaling specificity in the Akt pathway in biology and disease. Adv. Biol. Regul. 55, 28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.04.001

Toth, B. B., Arianti, R., Shaw, A., Vamos, A., Vereb, Z., Poliska, S., et al. (2020). FTO Intronic SNP strongly influences human neck adipocyte browning determined by tissue and PPARgamma specific regulation: a Transcriptome analysis. Cell 9:987. doi: 10.3390/cells9040987

Tremblay, A. M., Dufour, C. R., Ghahremani, M., Reudelhuber, T. L., and Giguere, V. (2010). Physiological genomics identifies estrogen-related receptor alpha as a regulator of renal sodium and potassium homeostasis and the renin-angiotensin pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 22–32. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0254

Uldry, M., Yang, W., St-Pierre, J., Lin, J., Seale, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2006). Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 3, 333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.002

Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D., Vanhommerig, J. W., Smulders, N. M., Drossaerts, J. M., Kemerink, G. J., Bouvy, N. D., et al. (2009). Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1500–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718

Wang, X., and Seed, B. (2003). A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154

Wang, H., Xu, D., Toh, M. F., Pao, A. C., and You, G. (2016). Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK2 regulates human organic anion transporters 4 via ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. Biochem. Pharmacol. 102, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.024

Wu, J., Bostrom, P., Sparks, L. M., Ye, L., Choi, J. H., Giang, A. H., et al. (2012). Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 150, 366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016

Xu, D., Huang, H., Toh, M. F., and You, G. (2016). Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase sgk2 stimulates the transport activity of human organic anion transporters 1 by enhancing the stability of the transporter. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 7, 19–26.

Yu, X. X., Lewin, D. A., Forrest, W., and Adams, S. H. (2002). Cold elicits the simultaneous induction of fatty acid synthesis and beta-oxidation in murine brown adipose tissue: prediction from differential gene expression and confirmation in vivo. FASEB J. 16, 155–168. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0568com

Zhang, Y., Huypens, P., Adamson, A. W., Chang, J. S., Henagan, T. M., Lenard, N. R., et al. (2009). Alternative mRNA splicing produces a novel biologically active short isoform of PGC-1{alpha}. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32813–32826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037556

Keywords: brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes, beta-adrenergic receptor, thermogenesis, SGK2 kinase, PPARGC1A

Citation: Park C-H, Moon J, Park M, Cheng H, Lee J and Chang JS (2021) Protein Kinase SGK2 Is Induced by the β3 Adrenergic Receptor-cAMP-PKA-PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α Axis but Dispensable for Brown/Beige Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis. Front. Physiol. 12:780312. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.780312

Edited by:

Paula Oliver, University of the Balearic Islands, SpainReviewed by:

Francesc Villarroya, University of Barcelona, SpainAna Stancic, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Copyright © 2021 Park, Moon, Park, Cheng, Lee and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ji Suk Chang, amlzdWsuY2hhbmdAcGJyYy5lZHU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Chul-Hong Park

Chul-Hong Park Jiyoung Moon†

Jiyoung Moon† Jisu Lee

Jisu Lee Ji Suk Chang

Ji Suk Chang