- 1Pulmonary Function Testing Laboratory, Fundación Neumologica Colombiana, Bogotá, Colombia

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de La Sabana, Bogotá, Colombia

Background: Exercise intolerance, desaturation, and dyspnea are common features in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). At altitude, the barometric pressure (BP) decreases, and therefore the inspired oxygen pressure and the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) also decrease in healthy subjects and even more in patients with COPD. Most of the studies evaluating ventilation and arterial blood gas (ABG) during exercise in COPD patients have been conducted at sea level and in small populations of people ascending to high altitudes. Our objective was to compare exercise capacity, gas exchange, ventilatory alterations, and symptoms in COPD patients at the altitude of Bogotá (2,640 m), of all degrees of severity.

Methods: Measurement during a cardiopulmonary exercise test of oxygen consumption (VO2), minute ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), heart rate (HR), ventilatory equivalents of CO2 (VE/VCO2), inspiratory capacity (IC), end-tidal carbon dioxide tension (PETCO2), and ABG. For the comparison of the variables between the control subjects and the patients according to the GOLD stages, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test or the one-way analysis of variance test was used.

Results: Eighty-one controls and 525 patients with COPD aged 67.5 ± 9.1 years were included. Compared with controls, COPD patients had lower VO2 and VE (p < 0.001) and higher VE/VCO2 (p = 0.001), A-aPO2, and VD/VT (p < 0.001). In COPD patients, PaO2 and saturation decreased, and delta IC (p = 0.004) and VT/IC increased (p = 0.002). These alterations were also seen in mild COPD and progressed with increasing severity of the obstruction.

Conclusion: The main findings of this study in COPD patients residing at high altitude were a progressive decrease in exercise capacity, increased dyspnea, dynamic hyperinflation, restrictive mechanical constraints, and gas exchange abnormalities during exercise, across GOLD stages 1–4. In patients with mild COPD, there were also lower exercise capacity and gas exchange alterations, with significant differences from controls. Compared with studies at sea level, because of the lower inspired oxygen pressure and the compensatory increase in ventilation, hypoxemia at rest and during exercise was more severe; PaCO2 and PETCO2 were lower; and VE/VO2 was higher.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most prevalent chronic respiratory disease worldwide, even in cities located at high altitudes, and is the main cause in both men and women of the highest number of deaths and disability-adjusted life-years attributable to these chronic diseases (Caballero et al., 2008; Horner et al., 2017; Collaborators, 2020). Intolerance to exercise, desaturation, and dyspnea during exercise are common features in COPD patients that are related to quality of life and mortality (Nishimura et al., 2002; Oga et al., 2003; Casanova et al., 2008; Yoshimura et al., 2014).

In studies at sea level in patients with mild COPD, it has been shown that during exercise, compared to healthy subjects, oxygen uptake (VO2) and work rate (WR) are lower, and ventilatory equivalents for CO2 (VE/VCO2) and the dead space–to–tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) are higher, with similar values of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) and the alveolar–arterial oxygen tension gradient (A-aPO2) (Elbehairy et al., 2015). In patients with more advanced COPD, alterations in VE/VCO2 and VD/VT are more pronounced and are accompanied by hypoxemia, desaturation, widening of A-aPO2, and alveolar hypoventilation with CO2 retention (O’Donnell et al., 2002; Pinto-Plata et al., 2007; Neder et al., 2015).

At altitude, the barometric pressure (BP) decreases, and therefore the inspired oxygen pressure (PIO2) and arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) also decrease. The increase in ventilation with the decrease of the arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) is the main compensating mechanism that attenuates the drop in the PaO2 (West, 2004). In Bogotá, a city located at high altitude (2,640 m, BP 560 mm Hg), the PaCO2 at rest in healthy subjects decreases to approximately 33 mm Hg, and the PaO2 is 65 mm Hg, with values less than 60 mm Hg in the elderly (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2020) and even lower values in COPD patients (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2004).

Most of the studies evaluating ventilation and arterial blood gases (ABGs) during exercise in COPD patients have been made at sea level and in small populations of people ascending to or residents at very high altitudes. In a small sample of patients with moderate to severe COPD in Bogotá, we demonstrated lower VO2 at peak exercise in comparison to control subjects, alterations in ventilatory pattern, and higher hypoxemia in exercise than observed at sea level (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2004). The impact of Bogotá altitude on exercise capacity, dyspnea, and ABG alterations in exercise in COPD patients of all severity grades is not known. Our objective was to compare at the altitude of Bogotá, in a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), exercise capacity, ABG, symptoms, and ventilatory alterations among COPD patients of all degrees of obstruction severity.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This was a retrospective study in subjects referred between 2000 and 2019 to the Pulmonary Function Tests Laboratory of the Fundacion Neumologica Colombiana located in Bogotá (2,640 m) for a CPET. The institution’s research ethics committee approved the study and the use of the anonymous data sets (approval no. 202012-26004).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients had been referred to CPET for evaluation of exercise capacity, study of causes of dyspnea and exercise limitation, evaluation before pulmonary rehabilitation, or preoperative evaluation of benign extrathoracic pathologies. They were included if they had the ratio of forced expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) < 0.7, clinical stability for at least 6 weeks and were residents for more than 20 years in Bogotá, to exclude acute changes due to ascent to altitude. The severity of the obstruction was classified according to the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) using the post bronchodilator FEV1 (1: ≥80%; 2: 50–79%; 3: 30–49%, and 4: <30%) (Vogelmeier et al., 2017). Patients with permanent oxygen treatment or other respiratory diseases, chest wall disorders, and cardiovascular diseases other than cor pulmonale were excluded”. Control subjects, with normal spirometry, of the same age and sex, non-obese, non-smokers, untrained, and without a history of cardiopulmonary disease were included. The sample was taken during the same period of time in which patients with COPD were included, from subjects referred to CPET for evaluation of exercise capacity, exercise prescription, personalized medical check-ups, evaluation prior to work of high physical demand, or presurgical evaluation for benign extra thoracic diseases.

Functional Tests at Rest

Spirometry, maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV), and inspiratory capacity (IC) at rest were performed on a V-MAX 229d (Sensormedics Inc., Yorba Linda, CA, United States). A certified 3-L syringe was used for calibration. Flows and volumes were reported according to BTPS conditions (body temperature, ambient pressure, saturated with water vapor). Spirometry was done according to the standards of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society, and Crapo reference equations were used (Crapo et al., 1981; Miller et al., 2005).

Exercise Test

Exercise capacity was determined with a symptom-limited incremental test on a cycle ergometer. The test began with a 3-min rest period, followed by 3 min of pedaling without load, with a subsequent increase in workload every minute until the maximum tolerated level was reached (American Thoracic Society (ATS), and American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), 2003). The increment (10–25 W) was individually selected, depending on the reported exercise tolerance and resting functional impairment. A continuous electrocardiogram record was kept. The WR, VO2, CO2 production (VCO2), minute ventilation (VE), VT, respiratory frequency (fR), heart rate (HR), end-tidal carbon dioxide tension (PETCO2), and VE/VCO2 were recorded as mean values of 30 s throughout the test. For data analysis, the average was evaluated during 3 min of rest and in the last minute of peak exercise. VO2 values were compared with the reference values of Hansen et al. (1984) and Wasserman et al. (2012).

Arterial blood gases were taken at rest and during peak exercise. The A-aPO2 was calculated using the alveolar gas equation: FIO2 × (BP-47) − PaCO2 × [FIO2 + (1 − FIO2)/RER] − PaO2, where FIO2 (inspired fraction of oxygen) = 0.2093, mean BP ∼ 560 mm Hg, and RER = measured respiratory exchange ratio. The VD/VT was calculated with the PaCO2 and PETCO2. The anaerobic threshold (AT) was determined non-invasively using the v-slope method (American Thoracic Society (ATS), and American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), 2003). The sensation of dyspnea and muscle fatigue during the test were assessed using the Borg scale (Borg, 1982). Because differences in exercise capacity were expected between the GOLD stages, the dyspnea score was corrected for peak VE (Neder et al., 2015). IC was measured in all COPD patients at rest and at peak exercise.

Data Analysis

The normality of variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges for the quantitative variables and proportions for the qualitative variables were calculated. For the comparison of variables at rest and during exercise between control subjects and patients with COPD in all GOLD stages, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test or the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used, with the Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Two-tailed hypotheses were formulated with a significance level of less than 0.05. The statistical program SPSS version 15.0 was used.

Results

Subjects Characteristics

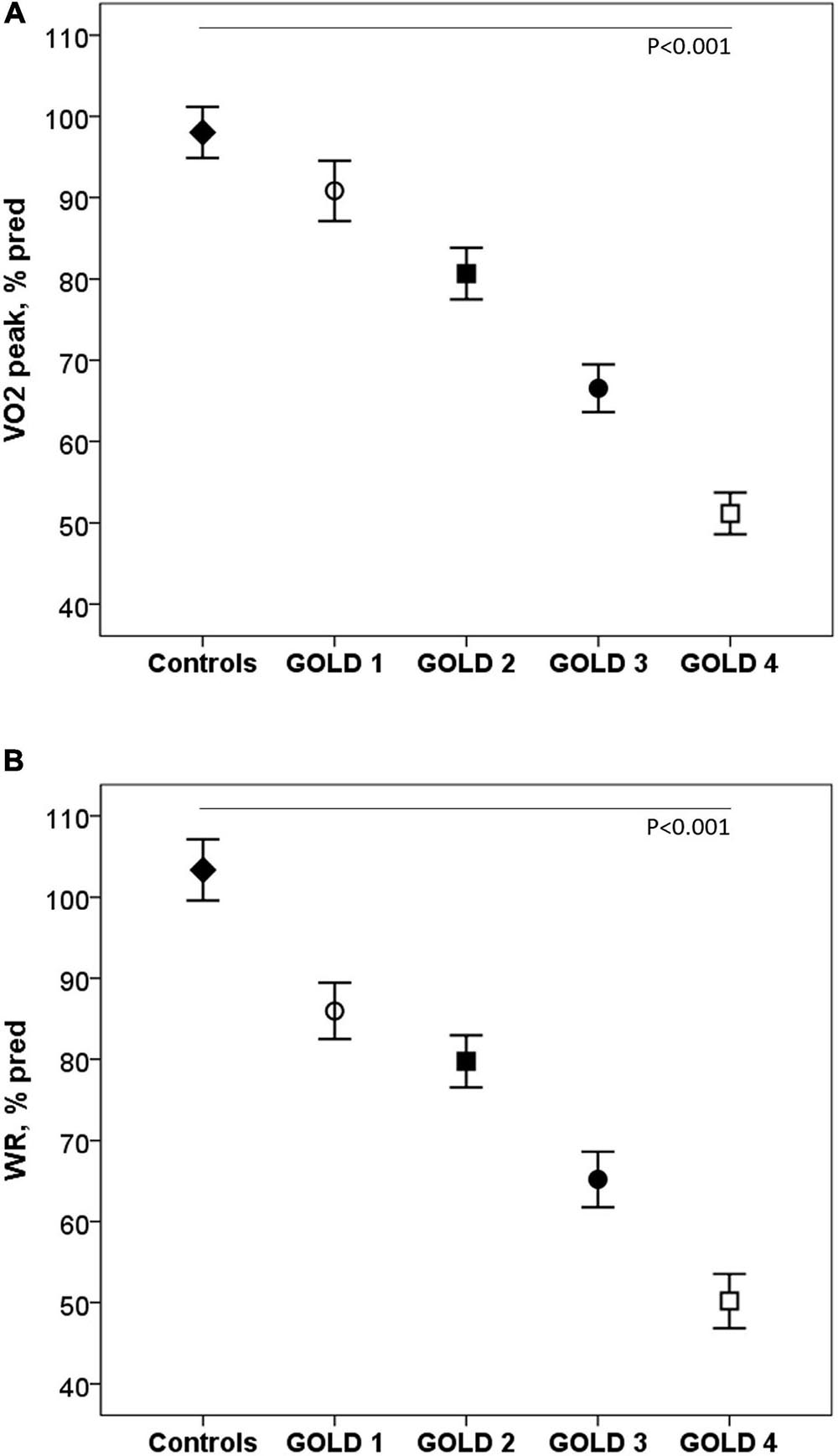

Four hundred forty-four COPD patients and 81 controls were included; 65% were men (Table 1). The mean age of the COPD patients was 67.5 ± 9.1 years and in controls 66.4 ± 4.5 years (p = 0.080). Body mass index (BMI) decreased and smoking increased from GOLD stage 1 to stage 4. Table 1 shows the decrease in MVV and IC, with the increase in obstruction (p < 0.001). Hemoglobin (Hb) values were significantly higher in the COPD patients at GOLD stages 2–4 than controls (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Subjects characteristics and resting functional variables in healthy controls and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients divided by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (n = 525).

Variables in Exercise

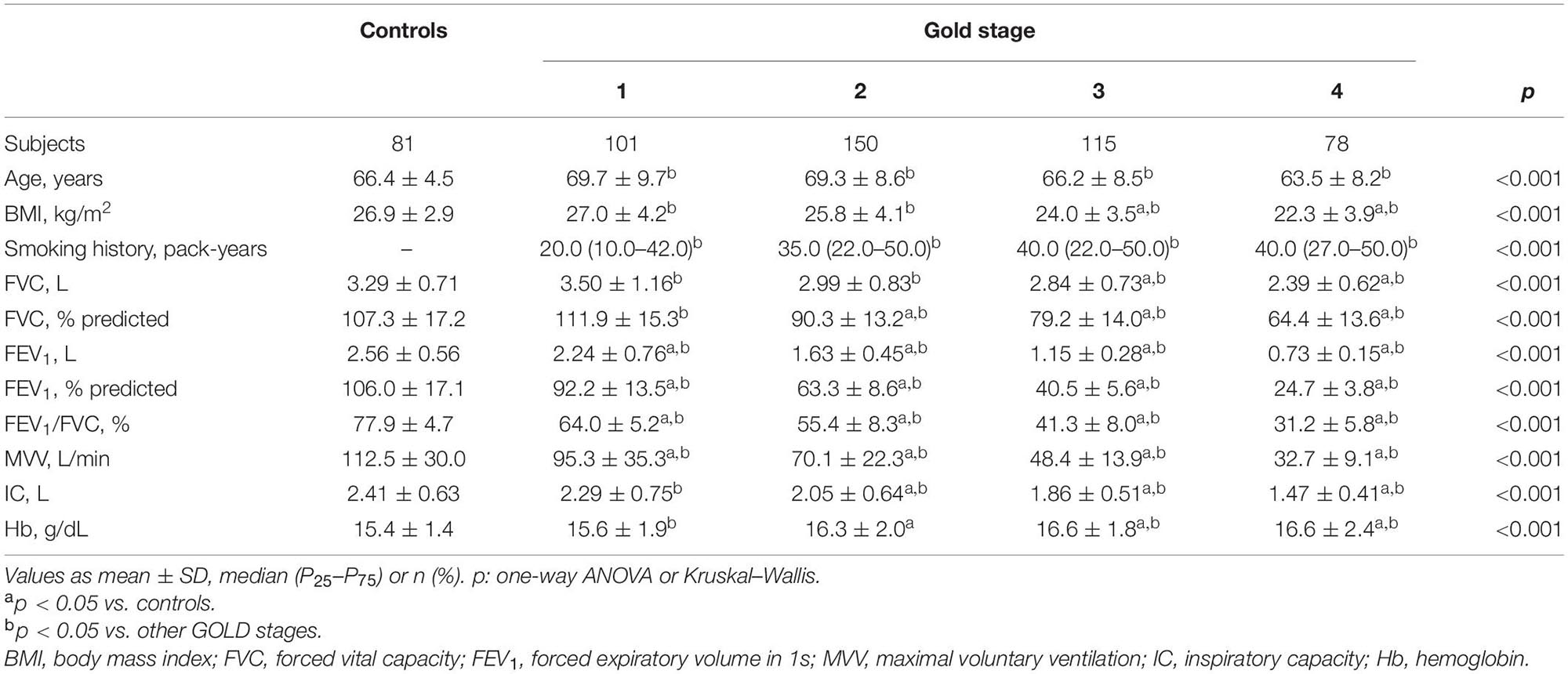

Exercise capacity decreased as the COPD severity increased. Compared with controls, COPD patients reached lower VO2 and workload (WR) at peak exercise, variables that progressively decreased as the COPD severity increased (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). The ΔVO2/ΔWR was lower in the patients GOLD stage 4 (p = 0.006). Peak HR and VO2/HR were also lower in COPD subjects and decreased with the severity of the obstruction (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Oxygen consumption (A) and work rate (B) at peak exercise in healthy controls and COPD patients by GOLD stages. VO2: Oxygen consumption; WR: work rate; GOLD: Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.◆, controls; ∘, GOLD 1; ■, GOLD 2; ∙, GOLD 3; □, GOLD 4. P: one-way ANOVA.

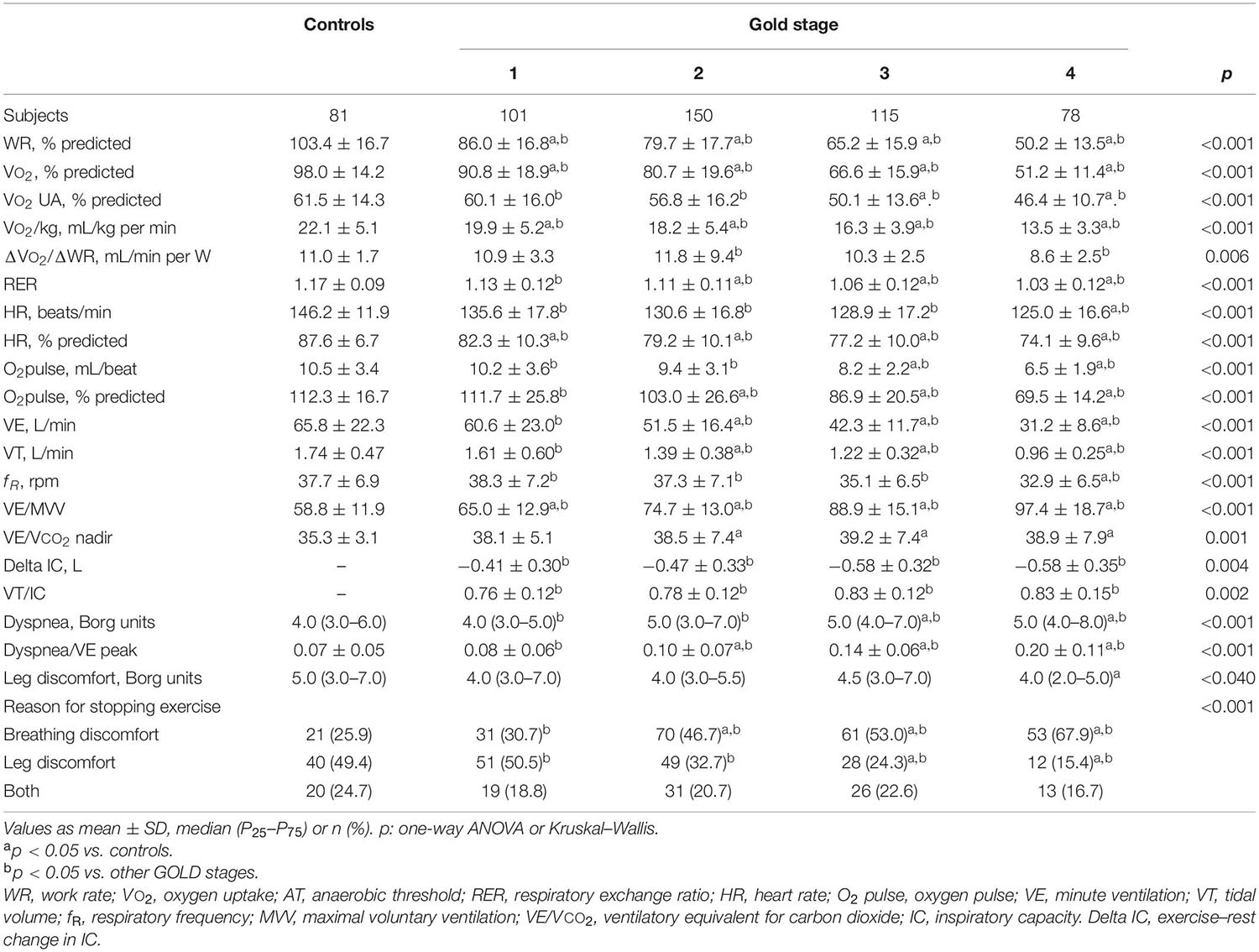

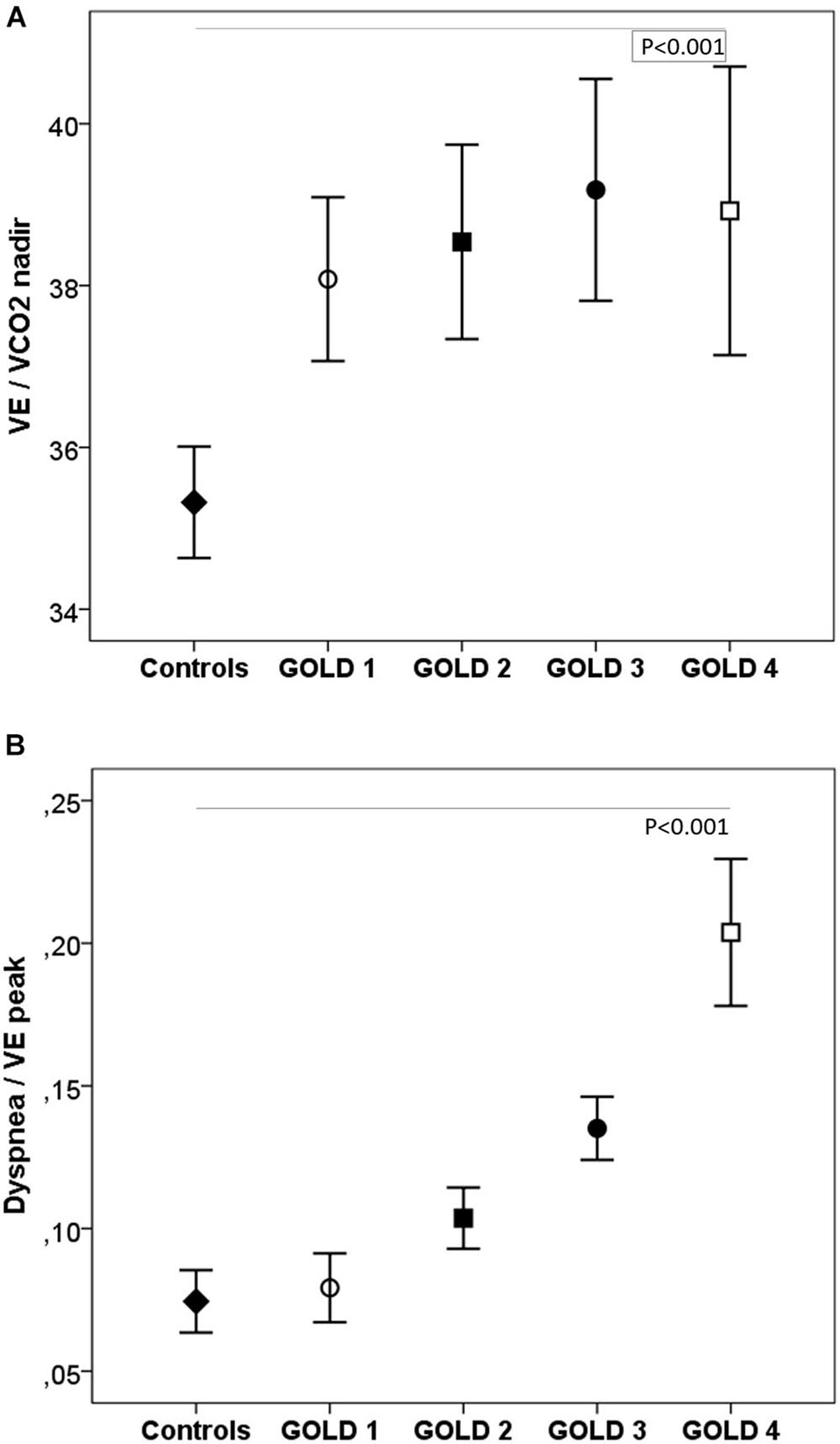

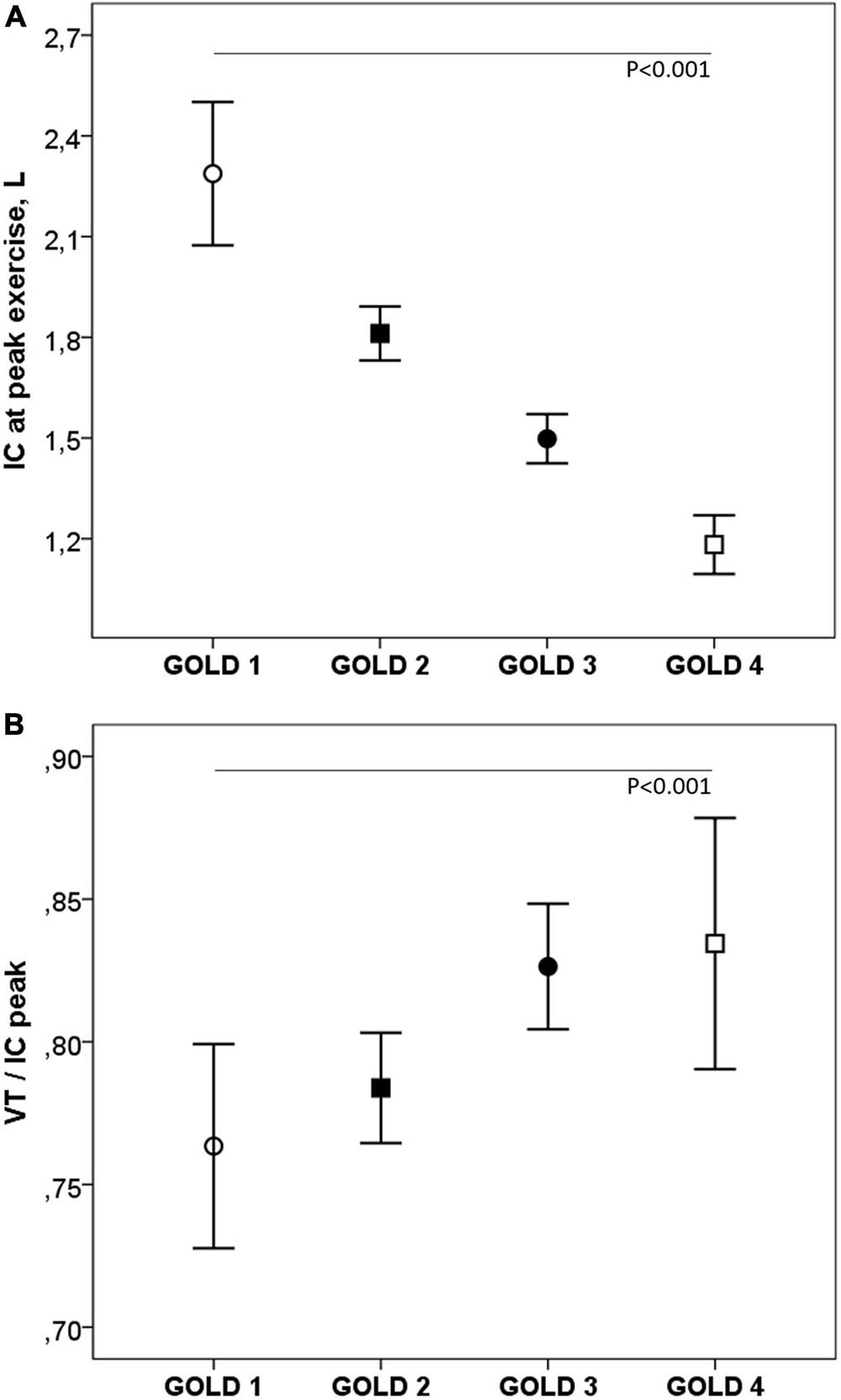

During exercise, as the GOLD stages increased, the VE and VT were lower and there was a progressive increase in VE/MMV. VE/VCO2 was higher in COPD patients than in controls with no differences between the GOLD stages (Table 2 and Figure 2). At peak exercise, as the severity of the obstruction increased, the IC decreased, and the delta IC and the VT/IC increased (Figure 3).

Table 2. Peak exercise variables in healthy controls and COPD patients divided by global initiative in chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) (n = 525).

Figure 2. Respiratory equivalents (A) and dyspnea (B) in healthy controls and COPD patients by GOLD stage. VE, minute ventilation; VE/VCO2, ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide. ◆, controls; ∘, GOLD 1; ■, GOLD 2; ∙, GOLD 3; □, GOLD 4. P, one-way ANOVA.

Figure 3. Inspiratory capacity (A) and VT/IC (B) at peak exercise in COPD patients by GOLD stage. IC, inspiratory capacity; VT, tidal volume. ∘, GOLD 1; ■, GOLD 2; ∙, GOLD 3; □, GOLD 4. P, one-way ANOVA.

ABGs, Dead Space, and PETCO2

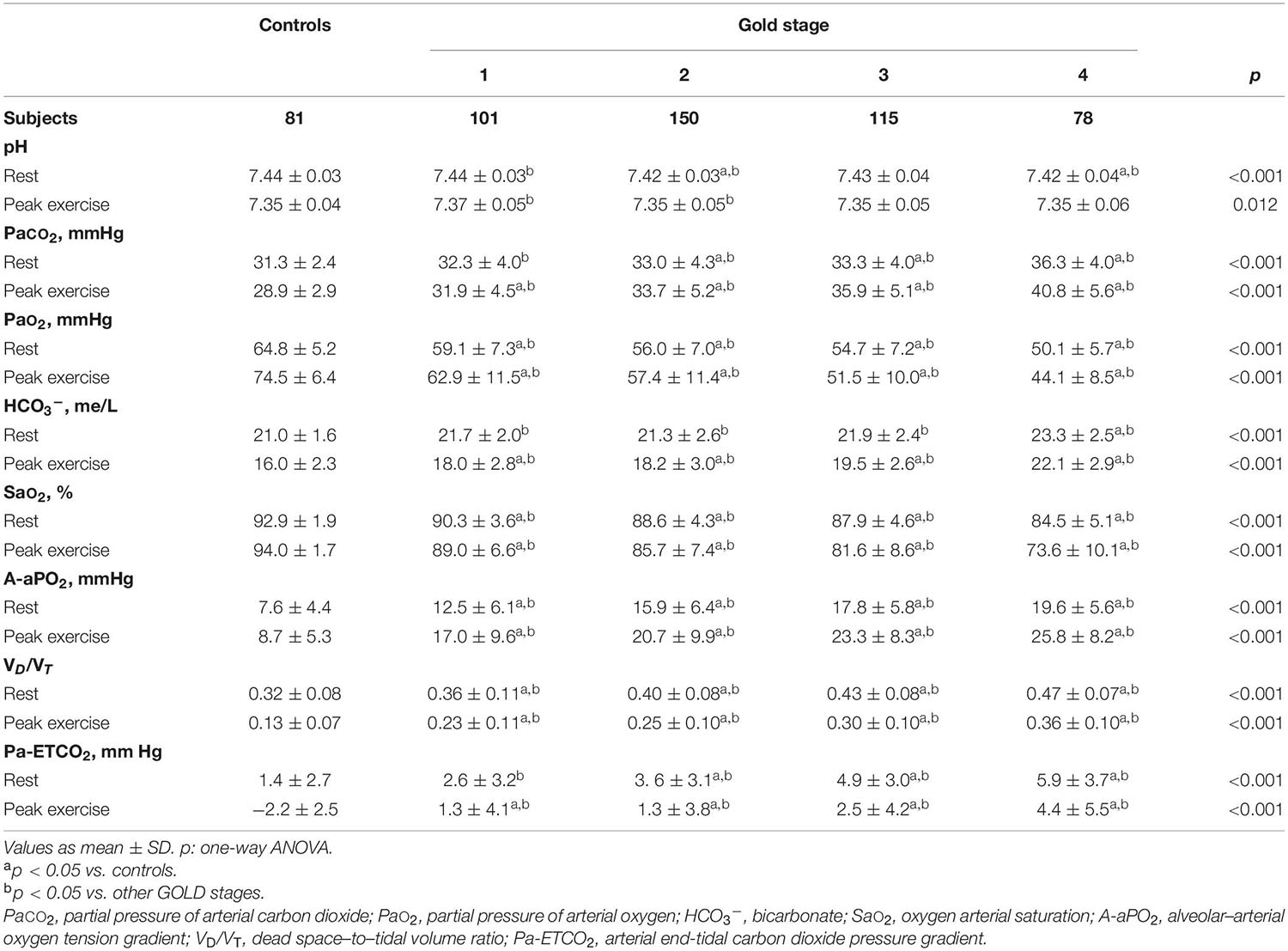

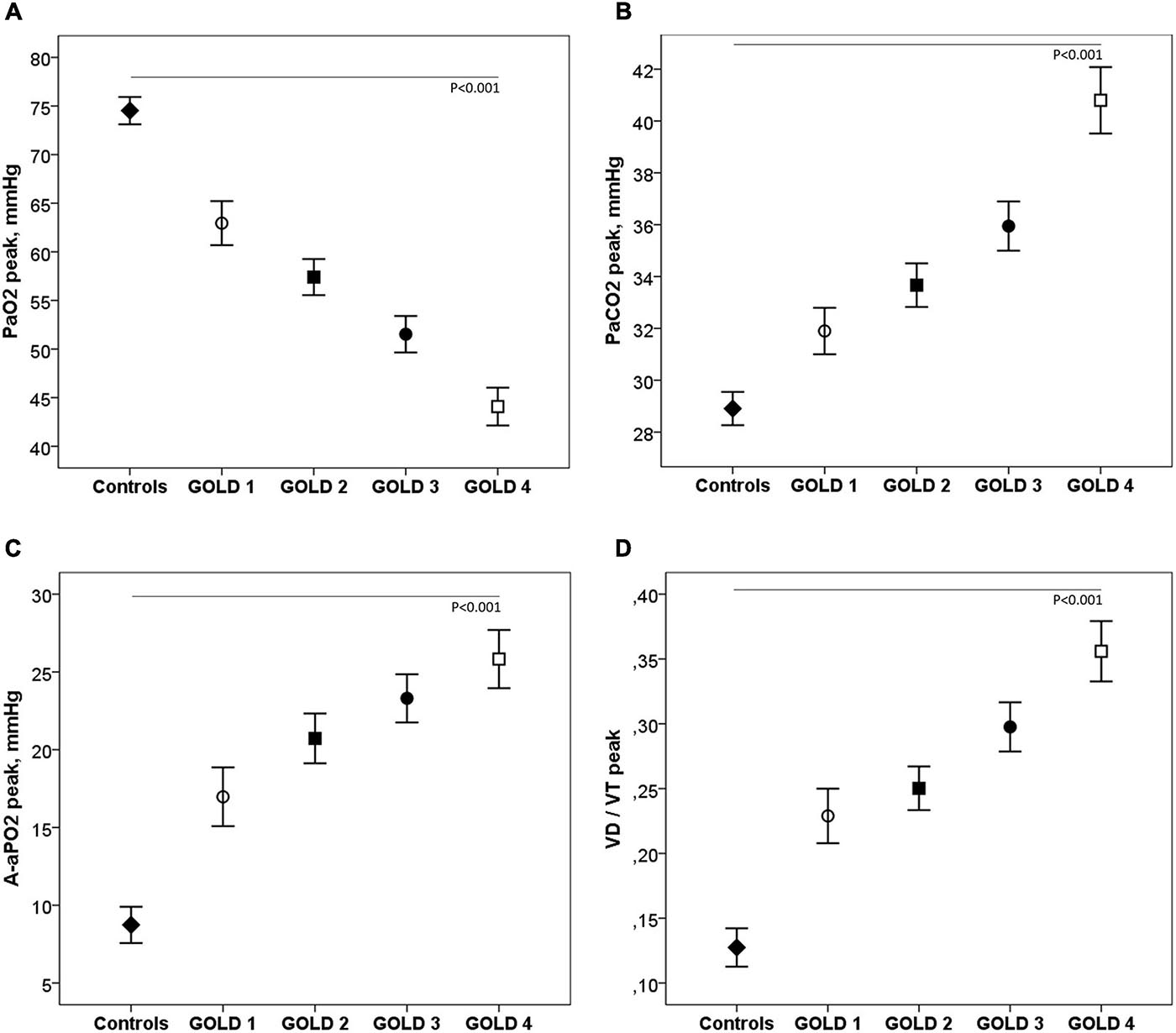

Table 3 shows the ABG and VD/VT values at rest and during exercise. In patients with mild COPD during exercise, PaO2 and saturation were significantly lower and A-aPO2 and VD/VT significantly higher than in controls. As the COPD severity increased, PaO2 decreased, and PaCO2, A-aPO2, and VD/VT increased, both at rest and at peak exercise (Figure 4).

Table 3. Gas exchange parameters at rest and peak exercise in healthy controls and COPD patients divided by the global initiative in chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) (n = 525).

Figure 4. Arterial blood gases (A–C) and VD/VT (D) at peak exercise in healthy controls and COPD patients by GOLD stage. ◆, controls; ∘, GOLD 1; ■, GOLD 2; ∙, GOLD 3; □, GOLD 4.

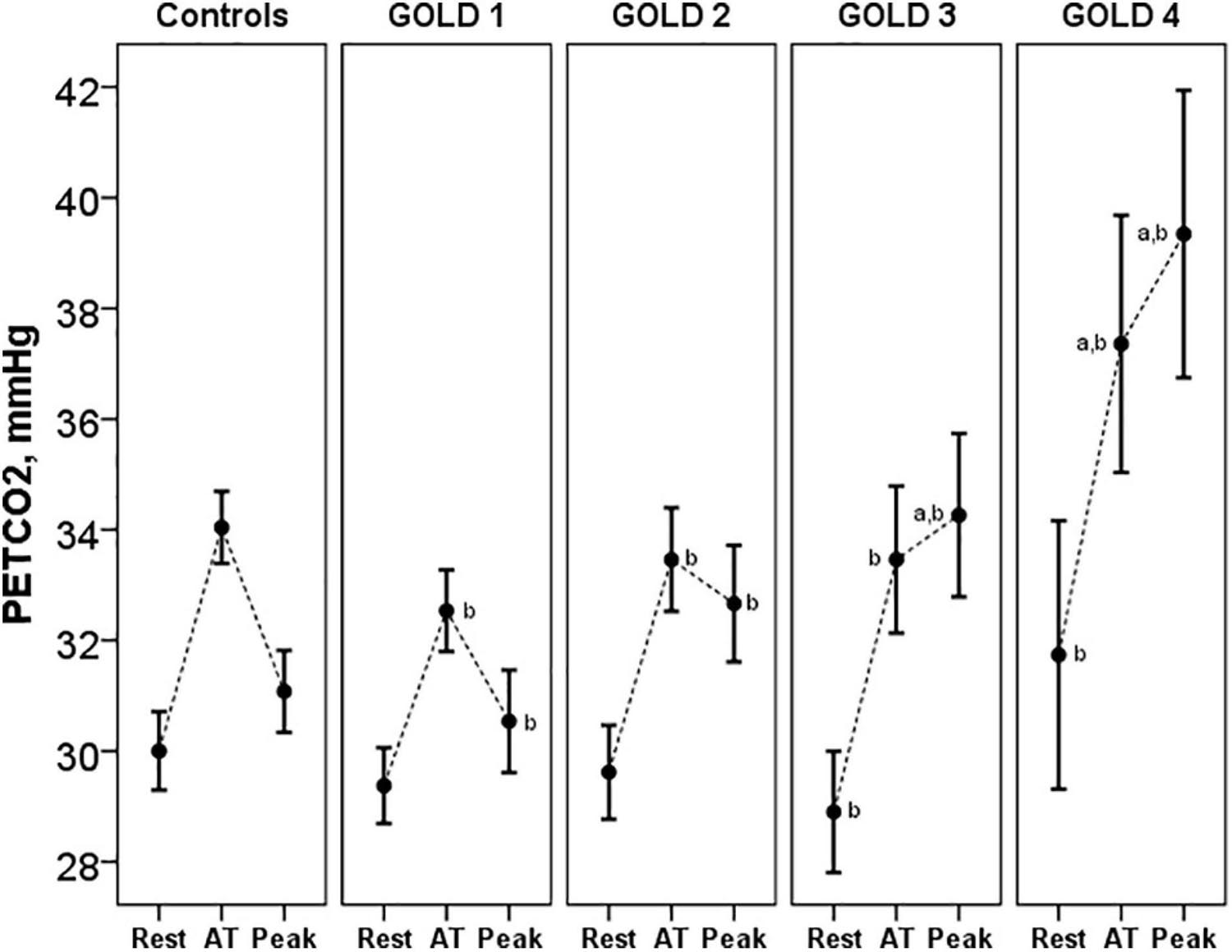

Pa-ETCO2 at rest and at peak exercise was higher in COPD patients and progressively increased from GOLD stage 1 to stage 4 (Table 3). In control subjects, PETCO2 increased during exercise from resting values to a higher value at the AT and then decreased in peak exercise toward resting values. This PETCO2 trajectory was similar in COPD GOLD stage 1. In more severe patients, the PETCO2 at AT was higher than in controls and GOLD stage 1 patients and failed to decrease, or even raised, at peak exercise (Figure 5).

Figure 5. PETCO2 at rest, AT and peak exercise in controls and COPD patients. ap < 0.05 vs. controls. bp < 0.05 vs. other GOLD stages. PETCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide tension; AT, anaerobic threshold.

Sensory Responses to Effort

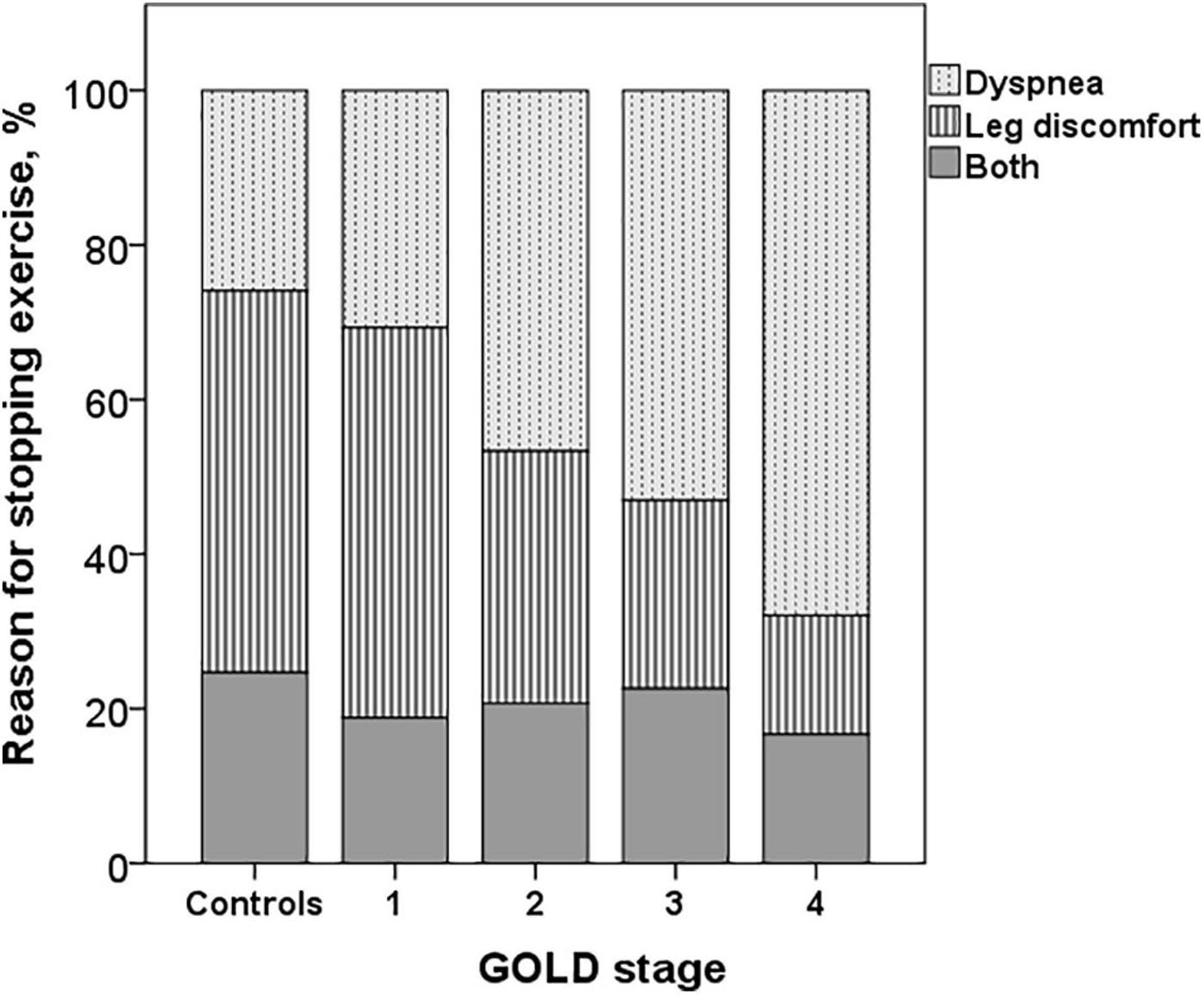

The dyspnea at peak exercise by the Borg scale and the dyspnea adjusted to VE increased significantly from GOLD stage 1 to stage 4 (Table 2 and Figure 2). The main symptom to stop the exercise in normal subjects and in patients with mild COPD was the fatigue of the lower limbs and the dyspnea in those with more severe obstruction (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Reasons for stopping exercise in controls and COPD patients. The dyspnea increased and the leg discomfort decreased from GOLD stages 1 to 4 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

The main findings of this study, with a significant number of COPD patients residing at high altitude, were the following: (1) progressive decrease in exercise capacity, increased dyspnea, dynamic hyperinflation (DH), restrictive mechanical constraints, and gas exchange abnormalities during exercise, across GOLD stages. (2) In patients with mild COPD, there were also lower exercise capacity and gas exchange alterations, with significant differences from controls in PaO2, A-aPO2, PaCO2, Pa-ETCO2, VE/VCO2, and VD/VT. (3) In comparison with studies at sea level, in these patients with COPD residing at altitude, due to the lower PIO2, hypoxemia at rest and during exercise was more severe, and because of the compensatory increase in ventilation, PaCO2 and PETCO2 were lower, and the VE/VO2 ratio higher.

Exercise Capacity

Although the progressive decrease in exercise capacity related to the severity of COPD has been previously reported, we highlight that despite hypoxemia, low saturation, and increased ventilatory requirements, VO2 and WR at peak exercise were similar to those described in studies at sea level, in patients of comparable age and severity of obstruction (Pinto-Plata et al., 2007; Vasilopoulou et al., 2012; Thirapatarapong et al., 2013; Neder et al., 2015), suggesting a process of adaptation to altitude in these subjects exposed to chronic hypoxia. In studies in COPD patients with acute exposure to hypoxia, ascending to an altitude similar to that of our study or using an altitude chamber, decrease in PaO2, SaO2, and PaCO2 at rest and in exercise has also been reported (Christensen et al., 2000; Kelly et al., 2009; Furian et al., 2018; Lichtblau et al., 2019). But contrary to our findings, in these subjects not chronically adapted to hypoxia, a significant decrease in exercise capacity has been described (Kelly et al., 2009; Furian et al., 2018).

Unlike studies that have shown a decrease in VO2 during exercise in healthy subjects after exposure to hypoxia for days or a few weeks (Fulco et al., 1998), relative preservation of exercise capacity has been observed in natives of the Andes and Tibet, probably related to ventilatory, circulatory, and peripheral adaptations (Favier et al., 1995; Marconi et al., 2006; Beall, 2007; Brutsaert, 2008; Calbet and Lundby, 2009). In studies in inhabitants of the Andes and Tibet, differences in adaptation to altitude have been observed, with higher levels of ventilation at rest and higher hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) in Tibetans and higher concentrations of Hb in Andeans at the same altitude (Beall, 2007).

The ventilatory response to hypoxia varies according to the duration of the hypoxic stimulus. In healthy subjects, an acute increase in HVR has been described after ascent to altitude, and if the exposure time to hypoxia is longer (hours to months), ventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia occurs, leading to further increases in ventilation. When the exposure to hypoxia is for years or throughout life, desensitization to hypoxia arises, in which the HVR is attenuated, and both ventilation and ventilatory sensitivity to changes in PaO2 decrease (Chiodi, 1957; Beall et al., 1997; Pamenter and Powell, 2016). In this attenuation of HVR, genetic and physiological adaptive mechanisms are involved that determine the differences between races (Brutsaert et al., 2005; Pamenter and Powell, 2016). In Andean people, this attenuation is greater and is possibly mediated by a reduction in the chemosensitivity of peripheral receptors (Pamenter and Powell, 2016). On the other hand, studies at sea level in COPD patients have also shown increased activity and sensitivity of carotid chemoreceptors that may be related to increased cardiovascular risk (Stickland et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2018). Although this elevated ventilatory response has not been shown to contribute to the ventilatory limitation in COPD patients at low altitude (Phillips et al., 2019), the role of HVR in high-altitude COPD patients exposed to chronic hypoxemia should be studied.

In this study, in controls and COPD patients, both at rest and during exercise, PaCO2 and PETCO2 were lower, and VE/VCO2 higher, compared to sea level, because of an increase in the alveolar ventilation (Chiodi, 1957; Dempsey and Forster, 1982). Also, the Hb values were higher, especially in advanced COPD stages, indicative of adaptation to altitude. In the same way, in a previous study in a large sample of healthy subjects, we also demonstrated a lower PaCO2 at rest and somewhat higher levels of Hb in comparison to studies at a lower altitude than Bogotá (Gassmann et al., 2019).

The administration of oxygen during exercise with correction of hypoxemia improves exercise capacity and reduces symptoms in patients with COPD at sea level (Ekstrom et al., 2016; Ward et al., 2017). In a crossover clinical trial in patients with moderate to severe COPD residing in the altitude of Bogotá, we demonstrated that the administration of oxygen during exercise significantly increased the endurance time, by reducing ventilatory demand, improving oxygen transport and cardiovascular performance (Maldonado et al., 2014). It should be noted that although with the FIO2 of 35% there was an increase in PaO2 and SaO2 greater than that achieved with that of 28%, this increase did not represent a significant advantage in terms of exercise duration, suggesting that the partial correction of severe hypoxemia of these patients with COPD is effective in improving the variables involved in exercise limitation.

Cardiovascular Response

Compared to controls, HR and VO2/HR at peak exercise were lower in COPD subjects and decreased with the severity of the obstruction (p < 0.001). Although the HR at rest and during exercise has been reported to be lower at altitude, most studies have been performed after an acute exposure or a short stay at altitude (Mourot, 2018). In a study at different altitudes (sea level up to 5,100 m) in 6,289 subjects in Peru, the HR values had a minimal variation in relation to the residence altitude (Mejia et al., 2019).

Low VO2/HR at peak exercise suggests an abnormal hemodynamic response to exercise due to cardiovascular impairment and/or physical deconditioning (Pinto-Plata et al., 2007; Vasilopoulou et al., 2012; Thirapatarapong et al., 2013). In a study using bioimpedance, it was shown during a constant load exercise test that the greater the severity of the GOLD stage, the greater the deterioration of cardiac output (Vasilopoulou et al., 2012). Also, it has been shown that as COPD severity increases, the ventilatory mechanics is more compromised, determining alterations in the intrathoracic pressure balance, which produces a decrease in systolic volume. Other probable causes of the low oxygen pulse are the reduction of the pulmonary capillary bed and the physical deconditioning that manifests itself with physiological alterations during exercise similar to cardiovascular disease (Montes de Oca et al., 1996; O’Donnell et al., 2014).

Ventilatory Response

As expected, the more severe the COPD, the greater the ventilatory limitation. Across GOLD stages, there was a lower increase in VE during exercise, due to a lower increase in VT. This could be explained by the progressive decrease, as the obstruction severity progressed, in baseline and peak IC, increase in delta IC due to DH, and increase in inspiratory constraints on VT expansion, shown by the progressive increase in VT/IC. Also, the VE/VVM increased with greater severity of obstruction. IC measurements in COPD patients are reproducible and useful for a more comprehensive assessment of respiratory mechanical limitations during exercise, but strategies are required to optimize results (Guenette et al., 2013; Milne et al., 2020). In these patients, IC measurements were taken at rest to familiarize them with the maneuvers, and instructions were given during exercise to achieve adequate inspiratory effort. To ensure that the respiratory pattern returned to the baseline, the graphs of the flow-volume curve were observed in real time, and the maneuvers were performed with intervals greater than 1 min.

The VE/CO2 nadir, a measure of ventilatory efficiency, was higher in COPD patients than in controls, but without differences between GOLD stages, similar to that described at sea level (Neder et al., 2015). The VE/VCO2 increase is related to different mechanisms, usually coexisting, which included mechanical ventilatory restrictions, gas exchange abnormalities, high VD/VT, enhanced chemosensitivity, and abnormal PaCO2 set point (Weatherald et al., 2018). In these patients with COPD residents at high altitude, we demonstrated DH, restrictive mechanical constraints, elevated VD/VT, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, and desaturation with high Pa-ETCO2 and A-aPO2. These alterations occurred even in mild COPD patients and progressively increased in more advanced stages.

The VD/VT at rest and peak exercise was also significantly higher in COPD patients than in controls and increased across all GOLD stages. The higher physiological dead space is consistent with increased Pa-ETCO2, which also progressively increased from GOLD stage 1 to stage 4. The increase in Pa-ETCO2 was even presented in GOLD stage 1 patients, as has been shown in studies at sea level (Elbehairy et al., 2015). In relation to the PETCO2 trajectory, in control subjects and in patients with COPD GOLD stage 1, PETCO2 increased from the resting values to a higher value at the AT and then decreased at peak of exercise toward resting values, similar to previous descriptions (Hansen et al., 2007). In more severe patients, the PETCO2 at AT was higher than in controls and GOLD stage 1 patients and failed to decrease, or even raised, at peak exercise. These patients with more severe ventilatory impairment may not be able to increase ventilation adequately in response to acidemia and therefore have stable or increasing PETCO2 after AT.

PaO2 was significantly lower in COPD patients than in controls and progressively decreased as the severity of the obstruction increased. Although we do not have direct comparisons with data at sea level, this PaO2 was lower than that described in studies at sea level in COPD patients of similar age and severity of obstruction (Pinto-Plata et al., 2007). This low PaO2 during exercise can be explained by several mechanisms: low PIO2 secondary to decreased BP, low V/Q ratio, and hypercapnia (Wagner, 2015). Although in hypoxemia secondary to low PIO2, A-aPO2 should be normal and PaCO2 low, these two variables can be altered when there are additional mechanisms that cause hypoxemia, as is the case in patients with COPD. Low PaO2 during exercise was accompanied by a significant increase in A-aPO2 in all COPD patients, even those with mild obstruction, indicating a V/Q imbalance. PaCO2 during exercise was also significantly higher in all COPD patients than in controls, especially in GOLD stages 3–4, which would indicate a greater component of alveolar hypoventilation in these more severe patients. The greater PaCO2 seen in the more advanced stages could be explained by increased ventilation–perfusion mismatch, severe mechanical limitation with expiratory flow limitation and DH, and modifications in the respiratory controller (Montes de Oca and Celli, 1998; O’Donnell et al., 2002; O’Donnell and Laveneziana, 2006; O’Donnell et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2015). According to studies carried out at sea level with the multiple inert gas method, the diffusion limitation mechanism as a cause of hypoxemia in COPD patients is unlikely (Wagner et al., 1977; Wagner, 2015), but studies should be carried out in patients with COPD at altitude.

As significant data in this study, the A-aPO2 in the control subjects was similar to the values described at sea level. In studies at higher altitudes, in inhabitants of the Andes and Tibet, a low A-aPO2 has also been described in healthy subjects (Moore, 2017). It has been postulated that low A-aPO2 could preserve PaO2 and SaO2 during exercise and that these low values could be explained by a greater diffusion capacity, larger lungs and, alternatively, by a lower V/Q imbalance in these subjects (Wagner et al., 2002; Lundby et al., 2004; Calbet and Lundby, 2009).

As already mentioned, in patients with mild COPD in the altitude, there were a lower exercise capacity and gas exchange alterations, with significant differences from controls in VO2, WR, PaO2, SaO2, A-aPO2 PaCO2, Pa-ETCO2, VE/VCO2, and VD/VT. Studies at sea level have shown alterations in A-aPO2, V/Q disbalance, and high VD/VT in patients with mild COPD at rest and during exercise (Barbera et al., 1991; Pinto-Plata et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Roisin et al., 2009; Elbehairy et al., 2015). Also, a compensatory increase in VE has been described to maintain alveolar ventilation and ABG homeostasis, leading to early mechanical limitation, exercise intolerance, and more dyspnea (Elbehairy et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2015). In contrast to this, patients with mild COPD at altitude already have a chronic compensatory increase in ventilation at rest due to the decrease in PIO2 and a lower PaO2; thus, probably the increase in ventilation during exercise is insufficient to maintain this arterial gas homeostasis.

Sensory Responses to Effort

The main symptom for stopping exercise in normal subjects and in COPD GOLD stages 1 and 2 was fatigue of the lower limbs, and in the most severe (GOLD stages 3 and 4), it was dyspnea, as has already been described (Killian et al., 1992). In advanced stages of the disease, there is a greater decrease in IC secondary to DH, increased dead space, inefficient ventilation and mechanical constraints on VT expansion, and more severe alterations in gas exchange (O’Donnell et al., 1997, 2014, 2016; O’Donnell, 2006; Laveneziana et al., 2011; Elbehairy et al., 2015), which could explain a greater perception of dyspnea and probably an earlier interruption of exercise with less fatigue of the lower extremities. We did not find differences in dyspnea measured by the Borg scale or in the dyspnea/VE ratio at peak exercise between patients with COPD GOLD stage 1 and controls, but we did not assess dyspnea as a function of VE and WR throughout the exercise, parameters for a better evaluation of the perceptual response during exercise in these patients (O’Donnell et al., 2019; Neder et al., 2021).

This is the study conducted at altitude, with the largest number of subjects included, which assesses exercise capacity, gas exchange alterations, ventilatory limitation, and symptoms during exercise in COPD patients chronically exposed to hypoxia. Strengths of this study are the inclusion of patients of all stages of GOLD severity and a significant number of control subjects that allowed comparisons between groups. Also, the measurement of ABG and the ventilatory variables allowed us to comprehensively evaluate the limiting mechanisms of exercise in these patients. As most of the studies on the limiting factors of exercise capacity in COPD patients have been conducted at sea level and in small populations of people acutely ascending to altitude, this study in subjects chronically exposed to hypoxia increases knowledge about the pathophysiology of exercise in COPD at altitude.

Although COPD patients had to be free of exacerbations and on regular treatment to enter the study, we did not have a complete registry of medications that could modify exercise capacity in these patients. Even though we had a representative group of healthy subjects of the same age and sex, which allowed us to compare exercise capacity and ventilatory variables and ABG, we did not perform IC measurements in these subjects for comparisons with COPD patients. We also did not have carbon monoxide diffusion tests, lung volumes, and pulmonary arterial pressure data to assess the relationship of these resting functional tests with gas exchange and exercise capacity.

Taking into account that pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common complication of COPD that affects exercise capacity (Fenster et al., 2015; Blanco et al., 2020), future studies should evaluate the impact of PH in patients with COPD at altitude. Although there are several studies in the literature that establish a relationship between mortality in COPD and some variables measured during CPET such as peak VO2 and respiratory equivalents (Cardoso et al., 2007; Cote et al., 2007, 2008; Oga et al., 2011; Yoshimura et al., 2014; Puente-Maestu et al., 2016; Neder et al., 2017), longitudinal studies should be carried out to evaluate the prognostic value of these variables, as well as the role of gas exchange alterations at rest and during exercise in patients with COPD living at altitude.

Conclusion

In this study with a significant number of COPD patients and normal subjects residing at high altitude, we were able to comprehensively assess exercise capacity, symptoms, ventilatory response, and gas exchange disturbances during exercise. In patients with COPD, we observed decreased exercise capacity, increased dyspnea, DH, and gas exchange alterations, in all GOLD stages, including COPD with mild obstruction. Unlike similar studies at sea level, the degree of hypoxemia both at rest and during exercise in all degrees of severity was higher at the altitude of Bogotá.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Comité de Ética en Investigación de la Fundación Neumológica Colombiana, Bogotá, Colombia. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, design of the study, the manuscript writing, and approved the submission of the final manuscript. MG-G and MB contributed to the data abstraction and analysis. MG-G drafted the initial manuscript and the guarantor of this work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank DM, who passed away during the development of this project, for his teachings and contributions in the field of respiratory physiology.

Abbreviations

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BP, barometric pressure; ABG, arterial blood gases; BMI, body mass index; MRCm, modified Medical Research Council scale; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; MVV, maximal voluntary ventilation; PaCO2, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; HCO3–, bicarbonate; SaO2, oxygen arterial saturation; A-aPO2, alveolar–arterial oxygen tension gradient; VD/VT, dead space–to–tidal volume ratio; PETCO2, end-tidal partial pressure for carbon dioxide; Pa-ETCO2, arterial–end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure gradient; WR, work rate; VO2, oxygen uptake; VCO2, carbon dioxide production; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; HR, heart rate; VO2/HR, oxygen pulse; VE, minute ventilation; VT, tidal volume; fR, respiratory frequency; VE/VCO2, ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide; IC, inspiratory capacity; AT, anaerobic threshold.

References

American Thoracic Society (ATS) and American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). (2003). ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 211–277.

Barbera, J. A., Roca, J., Ramirez, J., Wagner, P. D., Ussetti, P., and Rodriguez-Roisin, R. (1991). Gas exchange during exercise in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Correlation with lung structure. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 144, 520–525. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.520

Beall, C. M. (2007). Two routes to functional adaptation: tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 8655–8660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701985104

Beall, C. M., Strohl, K. P., Blangero, J., Williams-Blangero, S., Almasy, L. A., Decker, M. J., et al. (1997). Ventilation and hypoxic ventilatory response of Tibetan and Aymara high altitude natives. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 104, 427–447. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199712)104:4<427::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-P

Blanco, I., Valeiro, B., Torres-Castro, R., Barberan-Garcia, A., Torralba, Y., Moises, J., et al. (2020). Effects of Pulmonary Hypertension on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 56, 499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2019.10.015

Borg, G. A. (1982). Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14, 377–381.

Brutsaert, T. D. (2008). Do high-altitude natives have enhanced exercise performance at altitude? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 33, 582–592. doi: 10.1139/H08-009

Brutsaert, T. D., Parra, E. J., Shriver, M. D., Gamboa, A., Rivera-Ch, M., and Leon-Velarde, F. (2005). Ancestry explains the blunted ventilatory response to sustained hypoxia and lower exercise ventilation of Quechua altitude natives. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 289, R225–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00105.2005

Caballero, A., Torres-Duque, C. A., Jaramillo, C., Bolivar, F., Sanabria, F., Osorio, P., et al. (2008). Prevalence of COPD in Five Colombian Cities Situated at Low, Medium, and High Altitude (PREPOCOL Study). Chest 133, 343–349.

Calbet, J. A., and Lundby, C. (2009). Air to muscle O2 delivery during exercise at altitude. High Alt. Med. Biol. 10, 123–134. doi: 10.1089/ham.2008.1099

Cardoso, F., Tufanin, A. T., Colucci, M., Nascimento, O., and Jardim, J. R. (2007). Replacement of the 6-min walk test with maximal oxygen consumption in the BODE Index applied to patients with COPD: an equivalency study. Chest 132, 477–482. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0435

Casanova, C., Cote, C., Marin, J. M., Pinto-Plata, V., de Torres, J. P., Aguirre-Jaime, A., et al. (2008). Distance and Oxygen Desaturation During the 6-min Walk Test as Predictors of Long-term Mortality in Patients With COPD. Chest 134, 746–752.

Chiodi, H. (1957). Respiratory adaptations to chronic high altitude hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 10, 81–87. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1957.10.1.81

Christensen, C. C., Ryg, M., Refvem, O. K., and Skjonsberg, O. H. (2000). Development of severe hypoxaemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at 2,438 m (8,000 ft) altitude. Eur. Respir. J. 15, 635–639. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15463500

Collaborators, G. B. D. C. R. D. (2020). Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 585–596. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3

Cote, C. G., Pinto-Plata, V., Kasprzyk, K., Dordelly, L. J., and Celli, B. R. (2007). The 6-min walk distance, peak oxygen uptake, and mortality in COPD. Chest 132, 1778–1785. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2050

Cote, C. G., Pinto-Plata, V. M., Marin, J. M., Nekach, H., Dordelly, L. J., and Celli, B. R. (2008). The modified BODE index: validation with mortality in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 32, 1269–1274. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138507

Crapo, R. O., Morris, A. H., and Gardner, R. M. (1981). Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 123, 659–664.

Dempsey, J. A., and Forster, H. V. (1982). Mediation of Ventilatory Adaptations. Physiol. Rev. 62, 262–346. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.1.262

Ekstrom, M., Ahmadi, Z., Bornefalk-Hermansson, A., Abernethy, A., and Currow, D. (2016). Oxygen for breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who do not qualify for home oxygen therapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11:CD006429. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006429.pub3

Elbehairy, A. F., Ciavaglia, C. E., Webb, K. A., Guenette, J. A., Jensen, D., Mourad, S. M., et al. (2015). Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities in Mild Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Implications for Dyspnea and Exercise Intolerance. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 191, 1384–1394. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0157OC

Favier, R., Spielvogel, H., Desplanches, D., Ferretti, G., Kayser, B., and Hoppeler, H. (1995). Maximal exercise performance in chronic hypoxia and acute normoxia in high-altitude natives. J. Appl. Physiol. 78, 1868–1874. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1868

Fenster, B. E., Holm, K. E., Weinberger, H. D., Moreau, K. L., Meschede, K., Crapo, J. D., et al. (2015). Right ventricular diastolic function and exercise capacity in COPD. Respir. Med. 109, 1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.09.003

Fulco, C. S., Rock, P. B., and Cymerman, A. (1998). Maximal and submaximal exercise performance at altitude. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 69, 793–801.

Furian, M., Hartmann, S. E., Latshang, T. D., Flueck, D., Murer, C., Scheiwiller, P. M., et al. (2018). Exercise Performance of Lowlanders with COPD at 2,590 m: data from a Randomized Trial. Respiration 95, 422–432. doi: 10.1159/000486450

Gassmann, M., Mairbaurl, H., Livshits, L., Seide, S., Hackbusch, M., Malczyk, M., et al. (2019). The increase in hemoglobin concentration with altitude varies among human populations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1450, 204–220. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14136

Gonzalez-Garcia, M., Barrero, M., and Maldonado, D. (2004). Exercise limitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the altitude of Bogota (2640 m). Breathing pattern and arterial gases at rest and peak exercise. Arch. Bronconeumol. 40, 54–61.

Gonzalez-Garcia, M., Maldonado, D., Barrero, M., Casas, A., Perez-Padilla, R., and Torres-Duque, C. A. (2020). Arterial blood gases and ventilation at rest by age and sex in an adult Andean population resident at high altitude. Eur. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 2729–2736. doi: 10.1007/s00421-020-04498-z

Guenette, J. A., Chin, R. C., Cory, J. M., Webb, K. A., and O’Donnell, D. E. (2013). Inspiratory Capacity during Exercise: measurement, Analysis, and Interpretation. Pulm. Med. 2013:956081. doi: 10.1155/2013/956081

Hansen, J. E., Sue, D. Y., and Wasserman, K. (1984). Predicted values for clinical exercise testing. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 129, S49–55. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.2P2.S49

Hansen, J. E., Ulubay, G., Chow, B. F., Sun, X. G., and Wasserman, K. (2007). Mixed-expired and end-tidal CO2 distinguish between ventilation and perfusion defects during exercise testing in patients with lung and heart diseases. Chest 132, 977–983. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0619

Horner, A., Soriano, J. B., Puhan, M. A., Studnicka, M., Kaiser, B., Vanfleteren, L., et al. (2017). Altitude and COPD prevalence: analysis of the PREPOCOL-PLATINO-BOLD-EPI-SCAN study. Respir. Res. 18:162. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0643-5

Kelly, P. T., Swanney, M. P., Stanton, J. D., Frampton, C., Peters, M. J., and Beckert, L. E. (2009). Resting and exercise response to altitude in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 80, 102–107. doi: 10.3357/asem.2434.2009

Killian, K. J., Leblanc, P., Martin, D. H., Summers, E., Jones, N. L., and Campbell, E. J. (1992). Exercise capacity and ventilatory, circulatory, and symptom limitation in patients with chronic airflow limitation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146, 935–940. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.935

Laveneziana, P., Webb, K. A., Ora, J., Wadell, K., and O’Donnell, D. E. (2011). Evolution of dyspnea during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact of critical volume constraints. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 1367–1373. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-1128OC

Lichtblau, M., Latshang, T. D., Furian, M., Muller-Mottet, S., Kuest, S., Tanner, F., et al. (2019). Right and Left Heart Function in Lowlanders with COPD at Altitude: data from a Randomized Study. Respiration 97, 125–134. doi: 10.1159/000492898

Lundby, C., Calbet, J. A., van Hall, G., Saltin, B., and Sander, M. (2004). Pulmonary gas exchange at maximal exercise in Danish lowlanders during 8 wk of acclimatization to 4,100 m and in high-altitude Aymara natives. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287, R1202–R1208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00725.2003

Maldonado, D., Gonzalez-Garcia, M., Barrero, M., Jaramillo, C., and Casas, A. (2014). Exercise endurance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at an altitude of 2640 meters breathing air and oxygen (FIO2 28% and 35%): a randomized crossover trial. COPD 11, 401–406.

Marconi, C., Marzorati, M., and Cerretelli, P. (2006). Work capacity of permanent residents of high altitude. High Alt. Med. Biol. 7, 105–115. doi: 10.1089/ham.2006.7.105

Mejia, C. R., Cardenas, M. M., Benites-Gamboa, D., Minan-Tapia, A., Torres-Riveros, G. S., Paz, M., et al. (2019). Values of heart rate at rest in children and adults living at different altitudes in the Andes. PLoS One 14:e0213014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213014

Miller, M. R., Hankinson, J., Brusasco, V., Burgos, F., Casaburi, R., Coates, A., et al. (2005). Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 26, 319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805

Milne, K. M., Domnik, N. J., Phillips, D. B., James, M. D., Vincent, S. G., Neder, J. A., et al. (2020). Evaluation of Dynamic Respiratory Mechanical Abnormalities During Conventional CPET. Front. Med. 7:548. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00548

Montes de Oca, M., and Celli, B. R. (1998). Mouth occlusion pressure, CO2 response and hypercapnia in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 12, 666–671.

Montes de Oca, M., Rassulo, J., and Celli, B. R. (1996). Respiratory muscle and cardiopulmonary function during exercise in very severe COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 1284–1289.

Moore, L. G. (2017). Measuring high-altitude adaptation. J. Appl. Physiol. 123, 1371–1385. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00321.2017

Mourot, L. (2018). Limitation of Maximal Heart Rate in Hypoxia: mechanisms and Clinical Importance. Front. Physiol. 9:972. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00972

Neder, J. A., Arbex, F. F., Alencar, M. C., O’Donnell, C. D., Cory, J., Webb, K. A., et al. (2015). Exercise ventilatory inefficiency in mild to end-stage COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 377–387. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135514

Neder, J. A., Berton, D. C., Arbex, F. F., Alencar, M. C., Rocha, A., Sperandio, P. A., et al. (2017). Physiological and clinical relevance of exercise ventilatory efficiency in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 49:1602036. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02036-2016

Neder, J. A., Phillips, D. B., Marillier, M., Bernard, A.-C., Berton, D. C., and O’Donnell, D. E. (2021). Clinical Interpretation of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing: current Pitfalls and Limitations. Front. Physiol. 12:552000. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.552000

Nishimura, K., Izumi, T., Tsukino, M., and Oga, T. (2002). Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest 121, 1434–1440. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434

O’Donnell, D. E. (2006). Hyperinflation, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 180–184. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-093DO

O’Donnell, D. E., Bain, D. J., and Webb, K. A. (1997). Factors contributing to relief of exertional breathlessness during hyperoxia in chronic airflow limitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155, 530–535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032190

O’Donnell, D. E., D’Arsigny, C., Fitzpatrick, M., and Webb, K. A. (2002). Exercise hypercapnia in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of lung hyperinflation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 166, 663–668. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2201003

O’Donnell, D. E., Elbehairy, A. F., Faisal, A., Webb, K. A., Neder, J. A., and Mahler, D. A. (2016). Exertional dyspnoea in COPD: the clinical utility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur. Respir. Rev. 25, 333–347. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0054-2016

O’Donnell, D. E., and Laveneziana, P. (2006). Physiology and consequences of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 15, 61–67. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00010002

O’Donnell, D. E., Laveneziana, P., Webb, K., and Neder, J. A. (2014). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: clinical integrative physiology. Clin. Chest Med. 35, 51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.09.008

O’Donnell, D. E., Milne, K. M., Vincent, S. G., and Neder, J. A. (2019). Unraveling the Causes of Unexplained Dyspnea: the Value of Exercise Testing. Clin. Chest Med. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.02.014

O’Donnell, D. E., Webb, K. A., and Neder, J. A. (2015). Lung hyperinflation in COPD: applying physiology to clinical practice. COPD Res. Pract. 1:4. doi: 10.1186/s40749-015-0008-8

Oga, T., Nishimura, K., Tsukino, M., Sato, S., and Hajiro, T. (2003). Analysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of exercise capacity and health status. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 544–549. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-583OC

Oga, T., Tsukino, M., Hajiro, T., Ikeda, A., and Nishimura, K. (2011). Predictive properties of different multidimensional staging systems in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 6, 521–526. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S24420

Pamenter, M. E., and Powell, F. L. (2016). Time Domains of the Hypoxic Ventilatory Response and Their Molecular Basis. Compr. Physiol. 6, 1345–1385. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150026

Phillips, D. B., Collins, S. E., Bryan, T. L., Wong, E. Y. L., McMurtry, M. S., Bhutani, M., et al. (2019). The effect of carotid chemoreceptor inhibition on exercise tolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized-controlled crossover trial. Respir. Med. 160:105815. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105815

Phillips, D. B., Steinback, C. D., Collins, S. E., Fuhr, D. P., Bryan, T. L., Wong, E. Y. L., et al. (2018). The carotid chemoreceptor contributes to the elevated arterial stiffness and vasoconstrictor outflow in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Physiol. 596, 3233–3244. doi: 10.1113/JP275762

Pinto-Plata, V. M., Celli-Cruz, R. A., Vassaux, C., Torre-Bouscoulet, L., Mendes, A., Rassulo, J., et al. (2007). Differences in cardiopulmonary exercise test results by American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society-Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage categories and gender. Chest 132, 1204–1211. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0593

Poon, C. S., Tin, C., and Song, G. (2015). Submissive hypercapnia: why COPD patients are more prone to CO2 retention than heart failure patients. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 216, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.03.001

Puente-Maestu, L., Palange, P., Casaburi, R., Laveneziana, P., Maltais, F., Neder, J. A., et al. (2016). Use of exercise testing in the evaluation of interventional efficacy: an official ERS statement. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 429–460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00745-2015

Rodriguez-Roisin, R., Drakulovic, M., Rodriguez, D. A., Roca, J., Barbera, J. A., and Wagner, P. D. (2009). Ventilation-perfusion imbalance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging severity. J. Appl. Physiol. 106, 1902–1908. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00085.2009

Stickland, M. K., Fuhr, D. P., Edgell, H., Byers, B. W., Bhutani, M., Wong, E. Y., et al. (2016). Chemosensitivity, Cardiovascular Risk, and the Ventilatory Response to Exercise in COPD. PLoS One 11:e0158341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158341

Thirapatarapong, W., Armstrong, H. F., Thomashow, B. M., and Bartels, M. N. (2013). Differences in gas exchange between severities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 186, 81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.12.013

Vasilopoulou, M. K., Vogiatzis, I., Nasis, I., Spetsioti, S., Cherouveim, E., Koskolou, M., et al. (2012). On- and off-exercise kinetics of cardiac output in response to cycling and walking in COPD patients with GOLD Stages I-IV. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 181, 351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.03.014

Vogelmeier, C. F., Criner, G. J., Martinez, F. J., Anzueto, A., Barnes, P. J., Bourbeau, J., et al. (2017). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195, 557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP

Wagner, P. D. (2015). The physiological basis of pulmonary gas exchange: implications for clinical interpretation of arterial blood gases. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 227–243. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00039214

Wagner, P. D., Araoz, M., Boushel, R., Calbet, J. A., Jessen, B., Radegran, G., et al. (2002). Pulmonary gas exchange and acid-base state at 5,260 m in high-altitude Bolivians and acclimatized lowlanders. J. Appl. Physiol. 92, 1393–1400. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00093.2001

Wagner, P. D., Dantzker, D. R., Dueck, R., Clausen, J. L., and West, J. B. (1977). Ventilation-perfusion inequality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Invest. 59, 203–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI108630

Ward, S. A., Grocott, M. P. W., and Levett, D. Z. H. (2017). Exercise Testing, Supplemental Oxygen, and Hypoxia. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14, S140–S148. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201701-043OT

Wasserman, K., Hansen, J. E., Sue, D. Y., Stringer, W., Sietsema, K., Sun, X. G., et al. (2012). “Measurements during integrative cardiopulmonary exercise testing,” in Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: including pathophysiology and clinical applications. 5 ed. eds K. Wasserman, J. E. Hansen, D. Y. Sue, and W. W. Stringer (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins), 154–180.

Weatherald, J., Sattler, C., Garcia, G., and Laveneziana, P. (2018). Ventilatory response to exercise in cardiopulmonary disease: the role of chemosensitivity and dead space. Eur. Respir. J. 51:1700860. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00860-2017

West, J. B. (2004). The physiologic basis of high-altitude diseases. Ann. Intern. Med. 141, 789–800.

Keywords: exercise, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, altitude, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, gas exchange, hypoxia, dynamic hyperinflation, ventilatory inefficiency

Citation: Gonzalez-Garcia M, Barrero M and Maldonado D (2021) Exercise Capacity, Ventilatory Response, and Gas Exchange in COPD Patients With Mild to Severe Obstruction Residing at High Altitude. Front. Physiol. 12:668144. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.668144

Received: 15 February 2021; Accepted: 28 April 2021;

Published: 18 June 2021.

Edited by:

Andrew T. Lovering, University of Oregon, United StatesReviewed by:

Michael Furian, University Hospital Zürich, SwitzerlandDevin B. Phillips, Queen’s University, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Gonzalez-Garcia, Barrero and Maldonado. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mauricio Gonzalez-Garcia, bWdvbnphbGV6QG5ldW1vbG9naWNhLm9yZw==

Mauricio Gonzalez-Garcia

Mauricio Gonzalez-Garcia Margarita Barrero1

Margarita Barrero1