- 1Division of Neonatology, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL, United States

- 2Centro de Biofísica y Bioquímica, Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Caracas, Venezuela

- 3UMR 5525 UGA-CNRS-Grenoble INP-VetAgro Sup TIMC, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France

- 4Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

- 5Department of Research, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL, United States

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is characterized by progressive muscle wasting and the development of a dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), which is the leading cause of death in DMD patients. Despite knowing the cause of DMD, there are currently no therapies which can prevent or reverse its inevitable progression. We have used whole body periodic acceleration (WBPA) as a novel tool to enhance intracellular constitutive nitric oxide (NO) production. WBPA adds small pulses to the circulation to increase pulsatile shear stress, thereby upregulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and subsequently elevating the production of NO. Myocardial cells from dystrophin-deficient 15-month old mdx mice have contractile deficiency, which is associated with elevated concentrations of diastolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]d), Na+ ([Na+]d), and reactive oxygen species (ROS), increased cell injury, and decreased cell viability. Treating 12-month old mdx mice with WBPA for 3 months reduced cardiomyocyte [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d overload, decreased ROS production, and upregulated expression of the protein utrophin resulting in increased cell viability, reduced cardiomyocyte damage, and improved contractile function compared to untreated mdx mice.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is caused by the lack of expression of dystrophin, which forms part of the dystroglycan structural complex in the sarcolemma (Hoffman et al., 1987; Muntoni et al., 2003). The absence of dystrophin produces a dysfunctional regulation of intracellular Ca2+ in skeletal muscle of DMD patients (Lopez et al., 1987) and in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice, one of the most frequently used animal models of DMD (Allen et al., 2010a; Altamirano et al., 2014) as well as in cardiac muscle (Mijares et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017). Furthermore, a disturbed intracellular Ca2+ regulation has also been found in smooth muscle (Lopez et al., 2020) and neurons (Lopez et al., 2016) from dystrophic mice. In addition to their progressive debilitating skeletal muscle myopathy, DMD patients as they aged develop a lethal dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with arrhythmias, myocardial fibrosis, and congestive heart failure (Sanyal and Johnson, 1982; Kamdar and Garry, 2016; Mavrogeni et al., 2018), which is the leading cause of death in DMD patients (Mazur et al., 2012; Passamano et al., 2012).

Presently, there are no effective treatments for DMD. Although various therapeutic approaches have been developed, they have not had a meaningful impact on DMD patients’ long-term health (Schinkel et al., 2012; Zhang and Duan, 2012) or unexpectedly have aggravated the cardiomyopathy in those patients (Townsend et al., 2009). Corticosteroid therapy still represents the primary treatment option, but it has serious side effects, limited skeletal muscle improvement, and it has and few to no benefits in preventing or treating DMD cardiomyopathy (Malik et al., 2012; Bylo et al., 2020).

Alternative therapies to treat DMD have been proposed in animal models based on enhancing nitric oxide (NO) production by providing NO-substrate availability like but (Ramachandran et al., 2013; Vianello et al., 2013), using NO donors (Marques et al., 2005; Miglietta et al., 2015), phosphodiesterase inhibitors (Percival et al., 2012; de Arcangelis et al., 2016), however, the outcome from human clinical trials have shown no effect (Victor et al., 2017) or a modest patient improvement (Nelson et al., 2014; Hafner et al., 2019). Whole body periodic acceleration (WBPA) is a non-invasive and non-pharmacological approach that increases pulsatile shear stress to the vascular endothelium causing upregulation of the expression of both endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) and the subsequent release of NO in humans (Fujita et al., 2005; Sackner et al., 2005a, b) and animal models (Adams et al., 2009; Uryash et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Altamirano et al., 2014). We have previously demonstrated that WBPA is an effective therapy alleviating the alterations observed in skeletal, cardiac muscles, and cortical neurons from young dystrophin-deficient mdx and dystrophin/utrophin double knock out mice (Altamirano et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017, 2018).

This study we tested the hypothesis that WBPA can ameliorate or reverse the severity of cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice by reducing diastolic [Ca2+] and [Na+] and oxidative stress and upregulating utrophin expression, which leads to a reduction in cardiomyocytes damage, increased cell viability, and improved cardiomyocyte contractility. We provide evidence that a mechanism that is related to NO mediates the WBPA-provoked cardioprotection. Our results raise the hope for lessening dystrophic cardiomyopathy in humans by enhancing NO signaling using WBPA.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

WT (C57BL10) and dystrophic mdx (C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx) 12-month old (mos) mice (middle-aged) were obtained from breeding colonies at the Mount Sinai Medical Center were used as experimental models. Founders for these colonies were initially obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, United States). All animals were housed under constant temperature (21–22°C) and humidity (50–60%) with a 12:12 light-dark cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. 12 old-month mdx mice were used because changes in heart function appear to be well established at that time, as well as in older mdx mice (Adamo et al., 2010). Male WT (N = 32) and mdx (N = 89) mice 12-month of age were randomly assigned to four groups: (a) WT, untreated; (b) WT, treated with WBPA; (c) mdx, untreated; (d) mdx, treated with WBPA.

Cardiomyocyte’s Isolation and Inclusion Criteria

With the animal under deep anesthesia (isoflurane), thoracotomy was performed, heart was excised, and LV myocytes were enzymatically dissociated from WT and mdx mice 15 months WBPA-treated and untreated mice using the method described previously (Liao and Jain, 2007). All cardiomyocytes used in this study met the following criteria: (i) a well-defined striation spacing with good edges; (ii) no spontaneous contraction when perfused with a physiological solution containing 1.8 mM Ca2+; and (iii) Resting sarcomere length ≥1.75 μm, determined at the beginning of the experiment (Wussling et al., 1987).

Whole Body Periodic Acceleration Protocol

Awake unanesthetized mice placed in a rodent holder (Kent Scientific, CT, United States) positioned on a motion platform (SK-L180-Pro, Scilogex, CT, United States) at a frequency of 480 cycles per min (cpm) for 1 h daily, 5 days a week, for 12 consecutive weeks. Untreated mice were placed in the rodent holder for 1 h daily, 5 days a week, for 12 consecutive weeks without receiving WBPA treatment.

Preparation of Ion-Selective Microelectrodes

Double-barreled Ca2+-selective microelectrodes were prepared and backfilled with the neutral carrier ETH-129 (21193 Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) and then with pCa 7 solution as described previously (Lopez et al., 2000; Eltit et al., 2013). Double-barreled Na+-selective microelectrodes were prepared as above but backfilled with the Na+-sensitive ion cocktail (Sodium Ionophore I Cocktail A, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) based on the neutral ligand ETH-227, as described previously (Eltit et al., 2013). The characteristics and properties of the ion-selective microelectrodes were similar to those described previously (Lopez et al., 1983, 2000; Eltit et al., 2013). After taking measurements of diastolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]d) or diastolic sodium concentration ([Na+]d), all microelectrodes were recalibrated, and if the two calibration curves did not agree within 3 mV, data was discarded.

Recording of [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d

Isolated cardiomyocytes from WBPA-treated and untreated mice were impaled with either Ca2+ or Na+ double-barreled selective microelectrodes. The potentials from 3 M KCl microelectrode barrel (resting membrane potential – Vm) and Ca2+microelectrode barrel (VCa) or from Vm and Na+ microelectrode barrel (VNa) were recorded via high impedance amplifier (WPI, DUO-223 electrometer, Sarasota, FL, United States) (Mijares et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017). The potential from the Vm barrel was subtracted electronically from the VCa or VNa potential to produce a differential Ca2 potential (VDiffE) or Na+ (VDiffE) potential that represents the cell [Ca2+]d or [Na+]d. The potentials recorded were stored in a computer for further analysis. Experiments were carried at 37°C.

Measurement of Intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS accumulation was measured in cardiomyocytes from WBPA-treated and untreated mice using 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (DCDHF-DA, Abcam, MA, United States). The DCF fluorescence was detected by a microplate reader (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale CA, United States) at an excitation of 488/20 nm and 525/540 nm emission wavelengths. Intensity values are reported normalized to untreated WT values after subtracting background fluorescence.

Cardiomyocyte Damage

Myocardial injury was determined in WBPA-treated and untreated mice by measuring plasma levels of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) quantified by ELISA (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Blood samples were drawn before and after WBPA or control treatment from the tail vein.

Cardiomyocyte Viability

Cardiomyocyte viability from WBPA-treated and untreated 15 months-old mice was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Abcam, MA, United States). Data collected from WBPA-treated and untreated mdx and WT mice are represented as a reduction in MTT concentration relative to untreated WT cardiomyocytes.

Resting Sarcomere Length

Resting sarcomere length was determined in quiescent cardiomyocytes isolated from 15-month old mice after a 15-s stimulation through a pair of platinum electrodes (1 Hz, 1 ms pulse duration, ∼1.5x threshold voltage) at 37°C using the video-edge detection system (IonOptix, Milton, MA, United States) (Lopez et al., 2017).

Measurement of Myocyte Contractility

We carried out contractile studies on isolated cardiac myocytes from WBPA-treated and untreated mice using a video-based edge-detection system (IonOptix, Milton, MA, United States), as previously described (Lopez et al., 2017). The cardiomyocytes were field stimulated through a pair of platinum electrodes at a frequency of 2 Hz (2 ms pulse duration, ∼1.5x threshold voltage) at 37°C. The following indices were determined: (i) peak shortening (PS), (ii) maximal velocity of shortening (+dL/dt), (iii) maximal velocity of relengthening (-dL/dt).

Western Blotting of Cardiac Muscle

Another cohort of 15-month WBPA-treated (N = 3) and untreated (N = 3) dystrophin-deficient mdx mice were euthanized using CO2. Ventricular tissues were dissected, minced, and homogenized in modified radioimmunoassay precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer as described before (Altamirano et al., 2014). Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States). Proteins were separated on SDS gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with primary. Equal amounts of total protein were separated on 4–12% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE Gels (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, United States) and transferred to Immobilon-FL PVDF membrane (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, United States). The following primary antibodies were used; dystrophin and utrophin and then secondary fluorescent antibodies (Abcam, MA, United States). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States) was used as protein loading controls. Blots were visualized by Enhanced Chemifluorescence (ECF) (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corporation, Piscataway, NJ, United States) on Storm 860 Imaging System (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corporation, Piscataway, NJ, United States).

L-NAME Pretreatment

L-NAME is a non-selective inhibitor of NO-synthase used to induce NO synthesis deficiency (Furfine et al., 1997). In a different cohort of 12-month dystrophin-deficient mdx mice were then randomized in four groups: (A) mdx no treatment (N = 7 mice); (B) WBPA-treated mdx for 12 weeks (N = 7 mice); (C) mdx mice pre-treated with L-NAME for 1 week before and throughout the WBPA treatment protocol (12 weeks) (N = 9 mice); (D) mdx mice pre-treated with L-NAME for 13 weeks (N = 7 mice). L-NAME (1 g/L) was provided in drinking water (ad libitum), equivalent to a dose of 180 mg/kg. This L-NAME dose inhibits NOS activity and can be administered for prolonged periods (Lampson et al., 2012). The water was replaced three times per week with fresh L-NAME containing water, and all L-NAME treated mice were placed in individual cages to evaluate daily water intake. Upon completing the protocol, [Ca2+]d and intracellular ROS production were measured in cardiomyocytes from all four groups as markers of cardioprotection.

Solutions

Normal Tyrode solution was made up as follows (in mM): 140 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose (pH 7.4). The Tyrode solution was continuously bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 gas mixture.

Statistical Analysis

No explicit power calculation was conducted before experimentation; the sample sizes used were based on our previous studies using WT and dystrophic mouse models (Mijares et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017). For multiple groups comparison, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used, followed by Tukey’s tests and student t-test for the Western blotting experiments to determine the degree of significance. Reported results are presented as mean ± S.E.M., with N representing the number of mice used and n representing the number of cardiomyocytes in which measurements were carried out. GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States) was used for statistical analyses. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Results

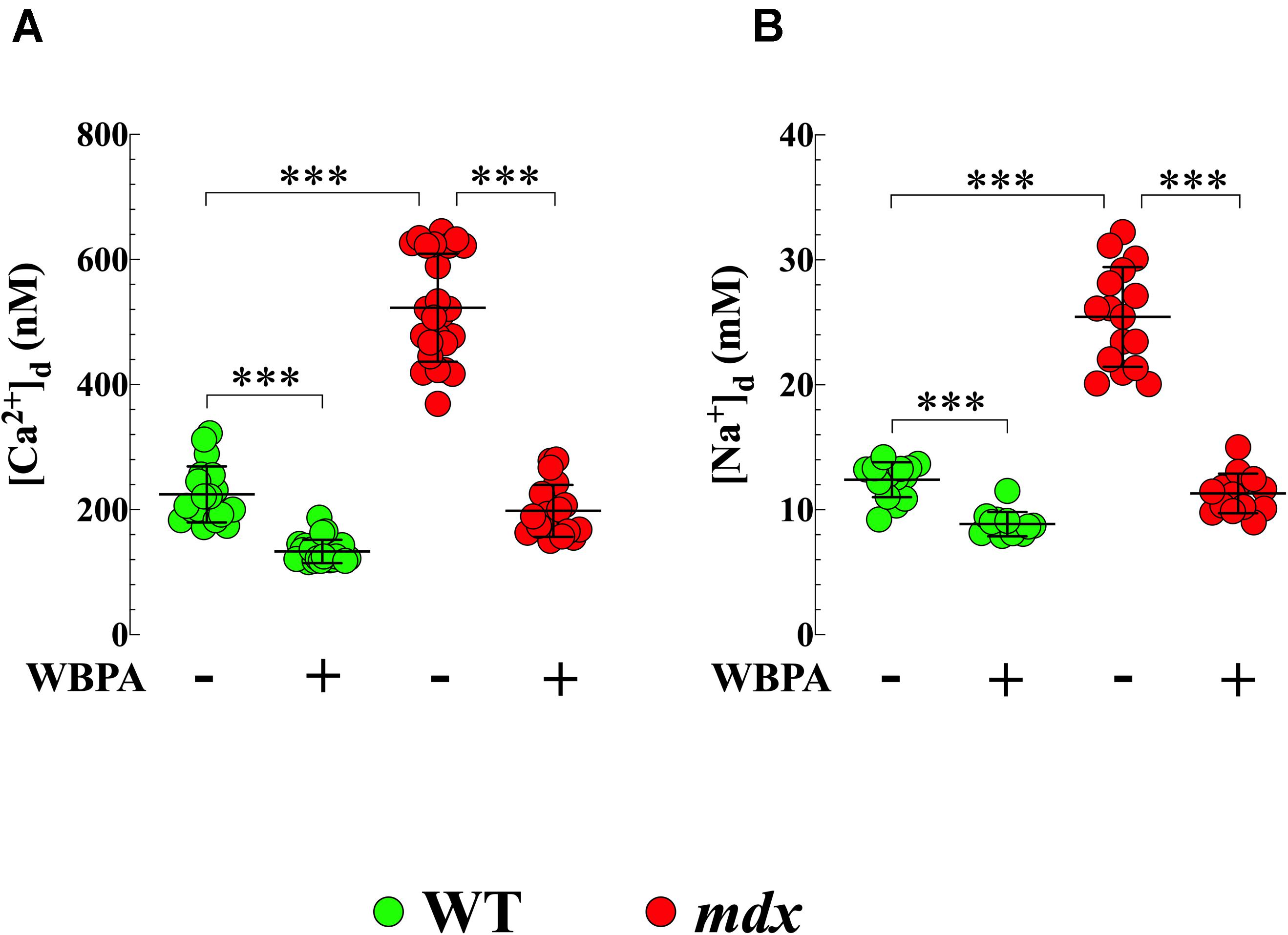

WBPA Normalized Aberrant [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d in mdx Cardiomyocytes

[Ca2+]d in cardiomyocytes from WT 15-month mice was 224 ± 45 nM while that in mdx cardiomyocytes was 523 ± 87 nM (p < 0.001 compared to WT) (Figure 1A). Treatment with WBPA significantly reduced [Ca2+]d in WT cardiomyocytes to 133 ± 19 nM, levels similar to those observed in young WT mice (3-month of age) (Mijares et al., 2014) (p < 0.001 compared to non-WBPA-treated WT) and in mdx cells from 523 ± 88 to 198 ± 42 nM (p < 0.001 compared to non-WBPA-treated mdx and p > 0.05 compared to non-WBPA-treated WT) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Whole body periodic acceleration lowered [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d in cardiomyocytes. [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d was measured in cardiomyocytes from 15-month treated and untreated, WT and mdx mice using ion-specific microelectrodes. Diastolic [Ca2+] (A) and [Na+] (B) were significantly higher in mdx than WT cardiomyocytes (2.4-fold and 2-fold, respectively). Whole body periodic acceleration (WBPA) reduced [Ca2+]d by 2.6-fold in mdx cardiomyocytes and by 1.7-fold in WT cardiomyocytes (A), while that [Na+]d was reduced by 2.2-fold in mdx cardiomyocytes and by 1.4-fold in WT cardiomyocytes (B). [Ca2+]d measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental condition, n = 19–21, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 4 mice, n = 25–19, respectively. [Na+]d measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 15–12, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 3 per experimental condition, n = 16–14, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, ***p ≤ 0.001.

We also found that [Na+]d was more elevated in cardiomyocytes from dystrophin-deficient mdx 15-month mice (25 ± 4 mM) compared to WT cardiomyocytes (12 ± 1.2 mM, p < 0.001) (Figure 1B). WBPA treatment significantly lowered [Na+]d in WT cardiomyocytes to 8.7 ± 1 mM, intracellular concentration comparable to those observed in young WT mice (Mijares et al., 2014) (p < 0.001 compared to non-WBPA-treated WT) and to 11 ± 2 mM in mdx cardiomyocytes (p < 0.001 compared to non-WBPA-treated mdx and p > 0.05 compared to non-WBPA-treated WT) (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that WBPA treatment reduced cardiomyocytes Ca2+ and Na+ overload found in 15-month WT and mdx mice.

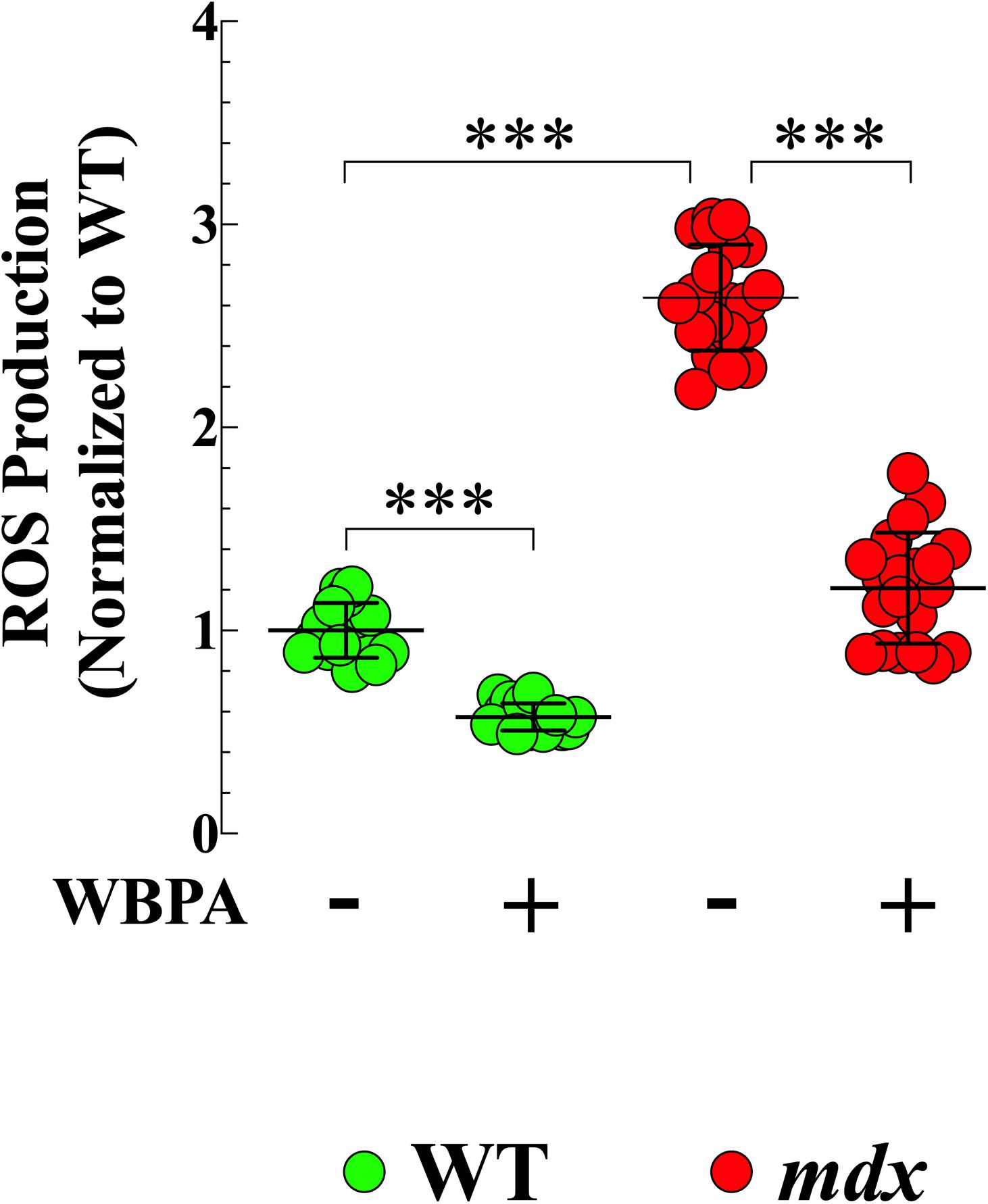

WBPA Decreased Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species in mdx Cardiomyocytes

Oxidative stress has been suggested is to be an important contributing factor to the muscle damage and weakness inherent to muscular dystrophy (Rodriguez and Tarnopolsky, 2003; Kaczor et al., 2007). We have shown previously that ROS production is elevated in young cardiomyocytes from mice lacking both dystrophin and utrophin and that WBPA partially improves intracellular ROS dyshomeostasis in those cells (Lopez et al., 2017). We found 2.6-fold increased production of ROS in 15-month mdx cardiomyocytes compared to WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 2). WBPA treatment reduced the levels of ROS in WT cardiomyocytes by 1.7-fold (p < 0.001) and in mdx cardiomyocytes by 2.7-fold (p < 0.001 compared to WBPA-untreated cardiomyocytes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Whole body periodic acceleration reduced ROS generation in cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes ROS production was evaluated in 15-month WBPA-treated and untreated WT and mdx dystrophin-deficient mice. Intracellular ROS was 2.6-fold higher in mdx cardiomyocytes than WT. WBPA treatment reduced intracellular ROS production by 2.7-fold in mdx cardiomyocytes and by 1.7-fold in WT cardiomyocytes compared to untreated mdx and WT cardiomyocytes. ROS measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 13–15, respectively. Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 17–20, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, ***p ≤ 0.001.

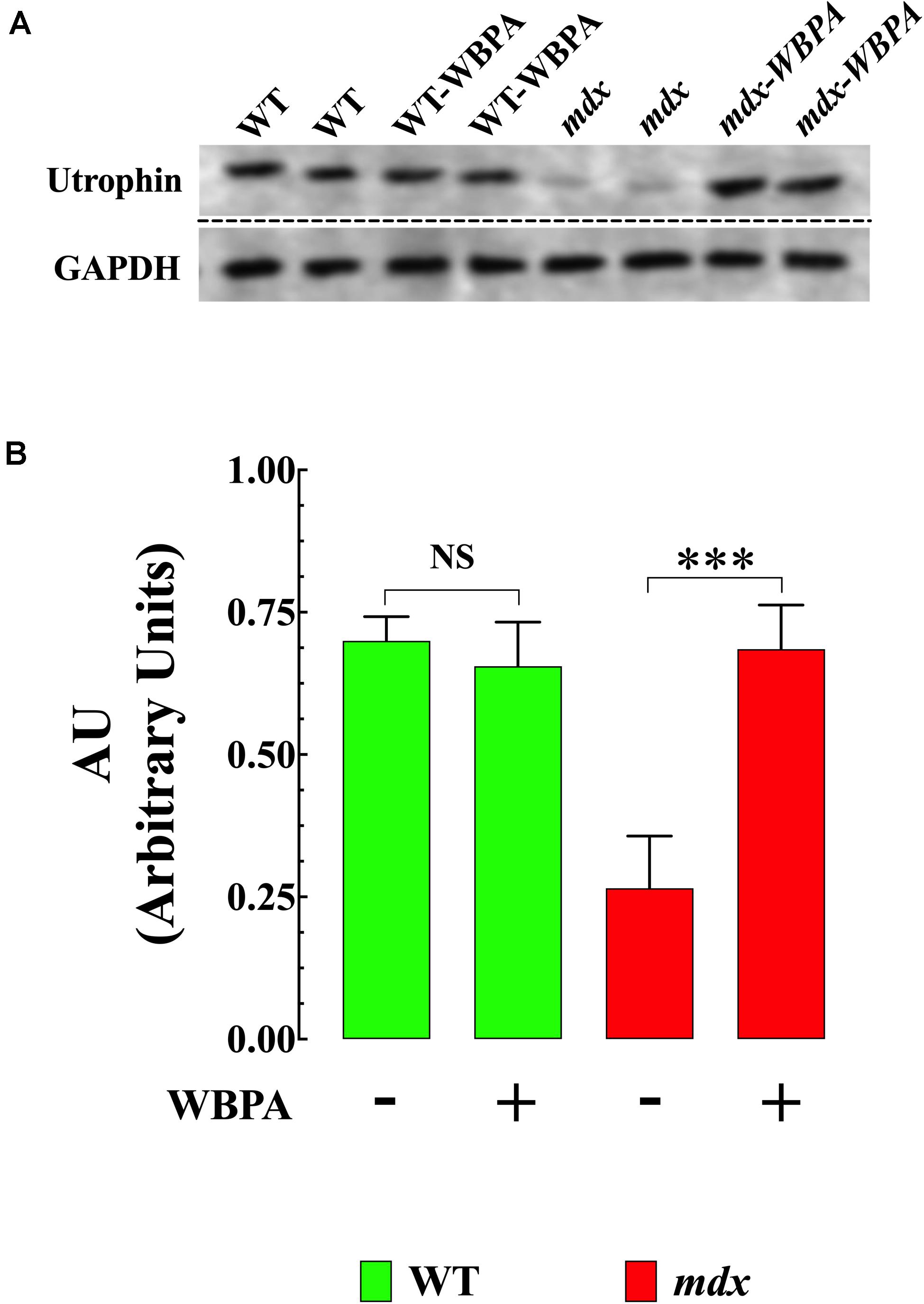

WBPA Promoted Upregulation of Utrophin

Previous studies have demonstrated that upregulation of utrophin (UTR) in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice results in the amelioration of pathology (Tinsley et al., 1998; Chaubourt et al., 1999; Cerletti et al., 2003). WBPA significantly upregulated utrophin expression (1.5-fold) in mdx heart compared to untreated mdx mice (Figures 3A,B). No significant effect was observed in WT cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. Whole body periodic acceleration enhanced expression of utrophin in mdx heart. (A) Representative Western blot showing the increase in utrophin expression in WBPA-treated mdx dystrophin-deficient heart homogenates compared to heart homogenates from untreated mdx mice. WBPA did not modify utrophin expression in WT. (B). Illustrated the densitometric analysis of Western blots proteins bands from WBPA-treated and untreated mdx heart. Data were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as mean ± S.D. Untreated mdx N = 3 mice and WBPA-treated mdx N = 3 mice. Paired t-test, ***p ≤ 0.001.

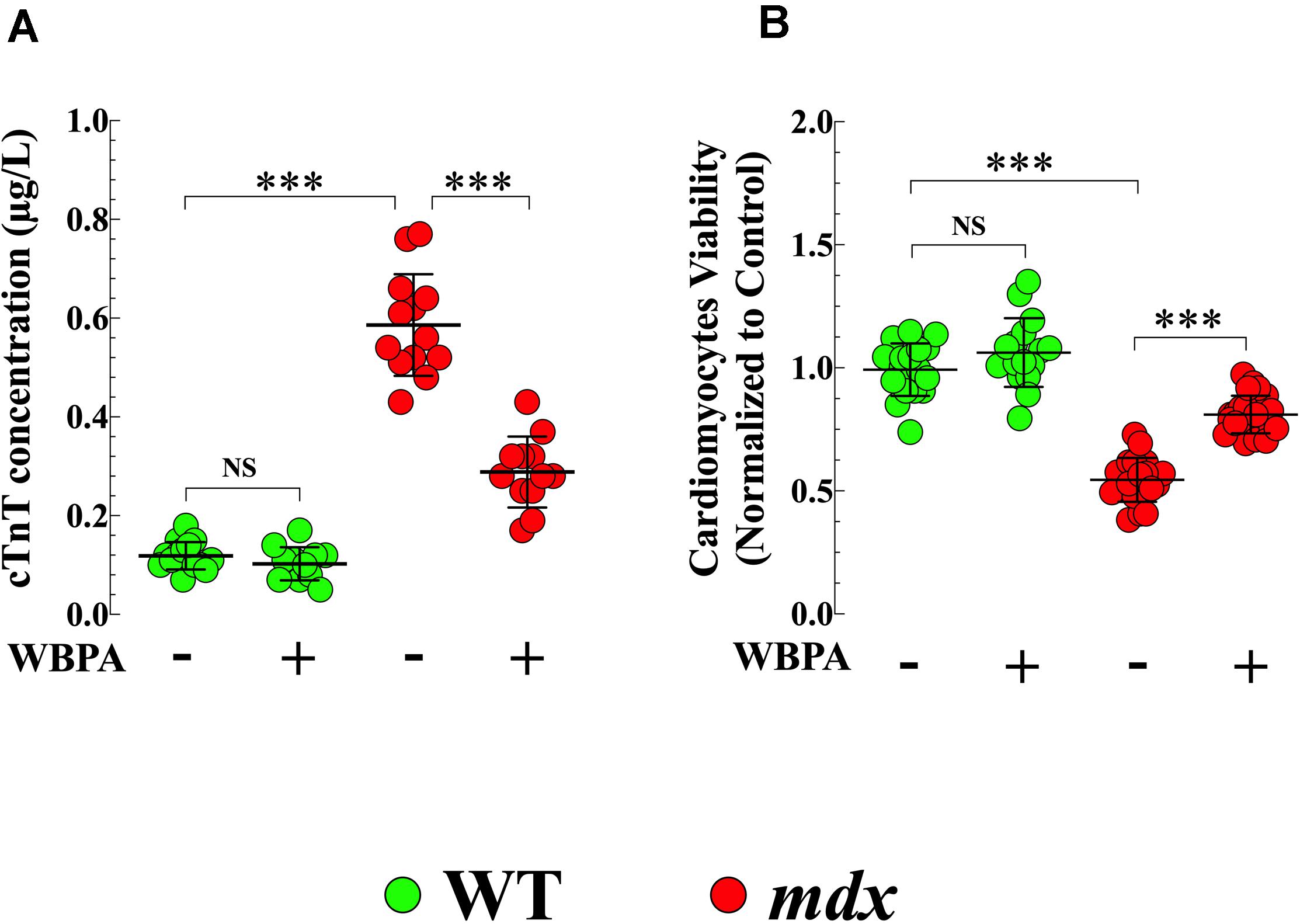

Attenuation of mdx Cardiomyocyte Damage by WBPA

Cardiac troponin T (cTnT) is an established blood biomarker with high sensitivity and specificity for myocardial injury (Wu et al., 2017). Plasma cTnT concentrations were significantly higher (4.9-fold, p < 0.001) in untreated mdx mice compared to WT (Figure 4A). WBPA treatment significantly reduced cTnT level by 2-fold (p < 0.001) in mdx mice, but it did not modify plasma levels of cTnT in WT mice (p = 0.89) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Whole body periodic acceleration reduced cTnT plasma level and increased cell viability. Measurements cTnT plasma level (A), and cardiomyocyte viability (B) were evaluated in 15-month WBPA-treated and untreated WT and mdx dystrophin-deficient mice. cTnT plasma level was 4.9-fold more elevated (A) in mdx than WT cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, mdx cardiomyocytes showed a reduction in cell viability by 1.7-fold compared to WT cardiomyocytes (B). WBPA lower cTnT plasma level by 2-fold (A), and increased cell viability by 1.4 compared to WBPA-untreated mdx (B). No effect of WBPA on cTnT release and cell viability was observed in WT cardiomyocytes (A,B). cTnT plasma level: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 5 mice per experimental conditions, n = 15–12, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 5 mice, per experimental conditions n = 13–12, respectively. Cell viability: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 18–16, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 5 mice, n = 20–24, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, ***p ≤ 0.001.

WBPA Improved mdx Cardiomyocytes Viability

In the heart, the absence of dystrophin causes cardiac muscle degeneration that compromises the integrity of the sarcolemma, resulting in progressive and irreversible cardiomyocyte degeneration that would induce cell death (Kamogawa et al., 2001). Untreated mdx cardiomyocytes showed 1.8-fold less viability compared to WT cardiomyocytes (p < 0.001) (Figure 4B). Treatment with WBPA increased the viability of mdx cardiomyocytes by 1.5-fold compared to untreated mdx cardiomyocytes (Figure 4B). Although WBPA increased viability slightly in WT cardiomyocytes, the difference was not significant (p = 0.161).

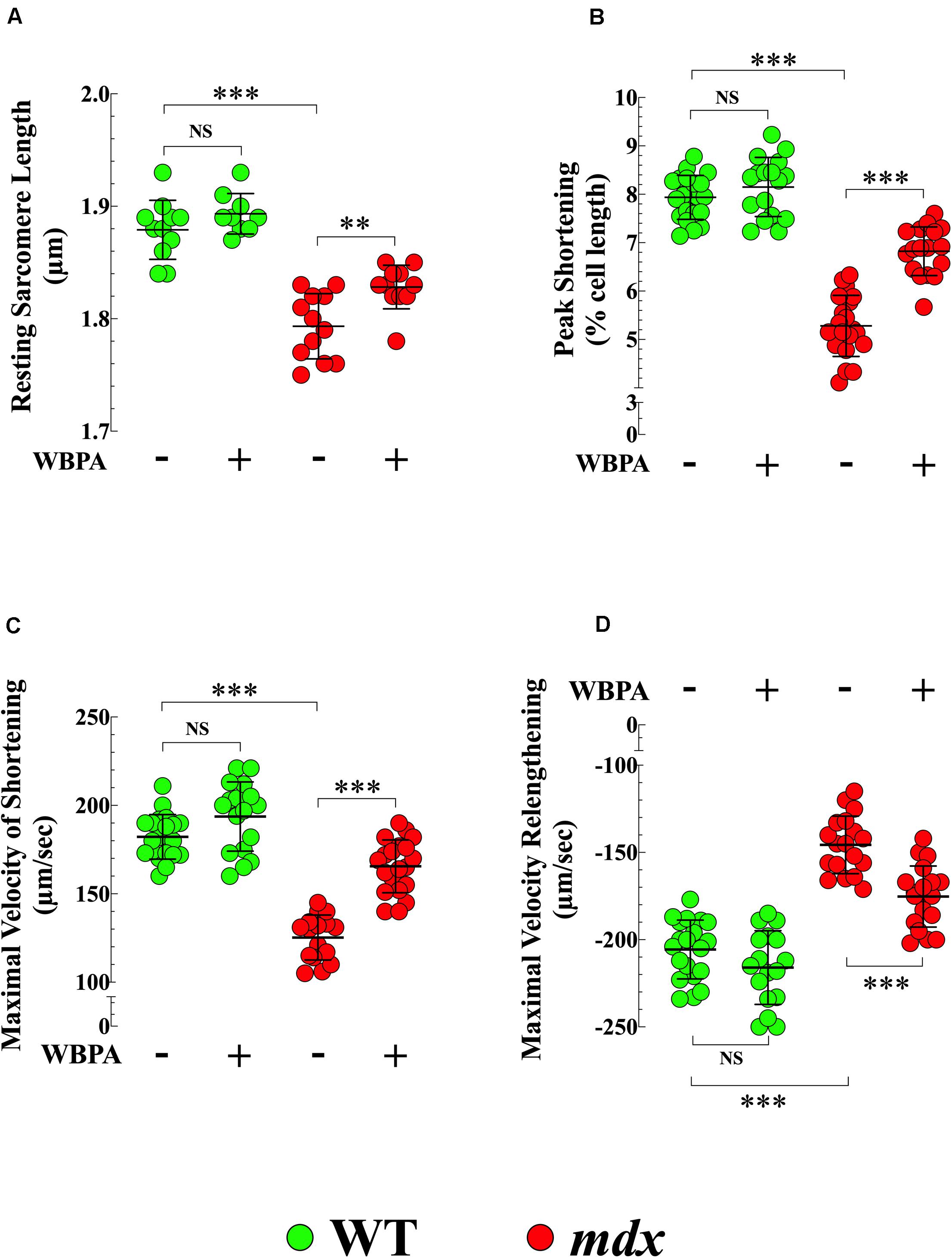

Effects of WBPA on the Reduced Contractility in mdx Cardiomyocytes

Cardiac contractile dysfunction is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DMD patients (Kamdar and Garry, 2016; Fayssoil et al., 2017). We found that the average diastolic sarcomere length was significantly different between 15-month WT and mdx cardiomyocytes (1.87 ± 0.01 vs. 1.79 ± 0.02 μm, p < 0.001) (Figure 5A), and that mdx cardiomyocytes exhibited a 1.5-fold decrease in peak shortening (PS) (p < 0.001), 1.5-fold decrease in maximal velocity of shortening (+dL/dt) (p < 0.001), and 1.4-fold decrease in the maximal velocity of relengthening (−dL/dt) (p < 0.001), compared with WT (Figures 5B–D). The WBPA treatment returned the diastolic sarcomere length of mdx cardiomyocytes to near WT values (1.82 ± 0.01 μm, p < 0.05) (Figure 5A) and significantly increased PS and +dL/dt by 1.3-fold (p < 0.001 and increased −dL/dt by 1.1-fold (p < 0.01) (Figures 5B–D). WBPA treatment did not significantly modify the contractile functions in WT cardiomyocytes, with the exception that +dL/dt that increased significantly (p < 0.03).

Figure 5. Whole periodic body acceleration improved reduced contractility of mdx cardiomyocytes. Contractility was studied in cardiomyocytes from 15-month treated and untreated, WT and mdx. The resting sarcomere length was smaller in dystrophin-deficient mdx cardiomyocytes compared to WT (A). Mdx cardiomyocytes showed a decrease of peak shortening (PS) (B), of maximal velocity of shortening (+dL/dt) (C), and of maximal velocity of relenthening (–dL/dt) (D) compared with age-match WT. The WBPA treatment returned the diastolic sarcomere length of mdx near WT cardiomyocytes values (A) and partially reversed the contractile dysfunction by significantly increasing PS (B), +dL/dt (C), and –dL/dt (D). WBPA treatment did not significantly modify the contractile properties in WT cardiomyocytes, (C). Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 4 mice per experimental conditions, n = 21–17, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx, N = 6 mice, per experimental conditions n = 17–20, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

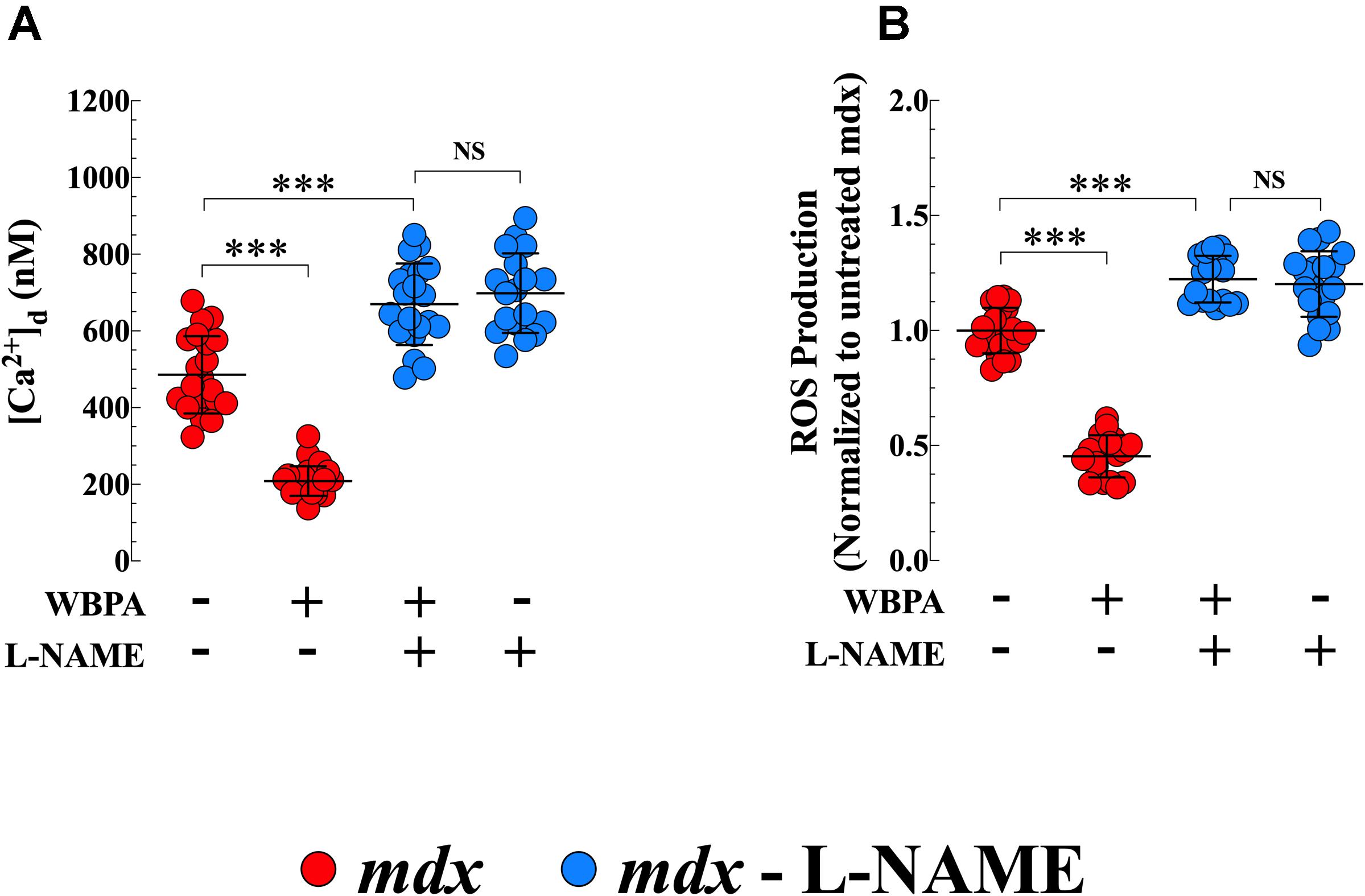

Involvement of NO in the Cardioprotective Effects of WBPA

L-NAME is widely used as an inhibitor of NOS activity (Palmer and Moncada, 1989). Pretreatment of mdx mice with L-NAME abolished the effects of WBPA on [Ca2+]d and intracellular ROS production in mdx cardiomyocytes (Figures 6A,B). Interestingly, inhibition of NOS synthase by L-NAME in mdx mice further increased cardiomyocyte [Ca2+]d by 1.4-fold and ROS generation by 1.2-fold compared to untreated mdx mice (Figures 6A,B).

Figure 6. L-NAME pretreatment abolished the cardioprotection induced by WBPA. Pretreatment of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice with L-NAME abrogated the beneficiary effect of WBPA on diastolic [Ca2+] (A) and intracellular ROS production (B). Interestingly, L-NAME pretreatment aggravated the [Ca2+]d overload and oxidative stress in mdx cardiomyocytes (A,B). [Ca2+]d measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx, N = 4 mice per experimental condition, n = 21–24, respectively; L-NAME and WBPA pretreated mdx N = 5 mice, n = 20; L-NAME pretreated mdx N = 4 mice, n = 18. ROS measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx, N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 20–18, respectively; L-NAME and WBPA pretreated mdx N = 4 mice, n = 17; L-NAME pretreated mdx N = 3 mice, n = 17. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that WBPA treatment provides cardioprotection and improves myocyte function in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice with established cardiomyopathy by reducing intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ overload, reducing intracellular ROS generation, enhancing the expression of utrophin, reducing cardiomyocyte damage, with the end result of improvement of cell viability and contractile function. Mechanistically, we provided evidence that the effect of WBPA on the heart is mediated through the nitric oxide pathway.

Cellular Dysfunction in mdx Cardiomyocytes From Mice With a Proven Cardiomyopathy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a degenerative disorder of striated and smooth muscle cells, characterized by the absence of the cytoskeletal protein dystrophin (Hoffman et al., 1987; Allen et al., 2010b). DMD patients show a dilated cardiomyopathy leading to heart failure, which is now the leading cause of mortality in DMD patients (Passamano et al., 2012). The early onset of dystrophic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is usually underdiagnosed because most dystrophic patients are asymptomatic in the disease’s initial phases. The development of DCM results from numerous mechanisms, one of which is an increase in diastolic [Ca2+] as seen in mdx, a mouse model of DMD (Williams and Allen, 2007a; Mijares et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017). The underlying mechanisms that led to this increase in [Ca2+]d are not yet fully understood; however, evidence points to S-nitrosylation of type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2) (Bellinger et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2015), resulting in SR-Ca2+ leak (Fauconnier et al., 2010), which contributes to the diastolic Ca2+ dysregulation observed in dystrophic cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, S-nitrosylation of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels (Chung et al., 2017) may enhance the Ca2+ influx provoking a further elevation of intracellular [Ca2+] as seen in mdx smooth muscle cells (Lopez et al., 2020). In addition, an increased Na+/Ca2+ exchanger function (Williams and Allen, 2007a), and ROS production (Williams and Allen, 2007b; Lopez et al., 2017) may also contribute to the intracellular calcium dyshomeostasis. Congruent with our previous reports (Mijares et al., 2014), we have confirmed that the lack of dystrophin in mdx cardiomyocytes with proven cardiomyopathy causes an age-dependent [Ca2+]d and [Na+]d overload (15-month > 12-month > 3-month) compared with age-matched WT cardiomyocytes. Abnormal intracellular Ca2+ regulation appears to play a major role in the molecular pathogenesis of DMD cardiomyopathy.

Reactive oxygen species are critical intracellular signaling molecules that control cellular metabolism, cell proliferation, cellular migration, cell death, and other cellular functions (Holmstrom and Finkel, 2014). Oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of several cardiovascular pathologies, such as cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, myocardial infarction, hypertension (Paravicini and Touyz, 2008; Nabeebaccus et al., 2011), and DCM (Williams and Allen, 2007b). Oxidation of the intracellular environment appears to initiate post-translational modifications of RyR2 channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and TRPC channels at the sarcolemma leading to an aberrant intracellular Ca2+, which results in activation of apoptotic and necrotic pathways and consequently, the loss of cardiomyocytes functions. We have found intracellular ROS production is significantly increased in mdx cardiomyocytes compared to WT. Exaggerated basal rate of ROS generation in dystrophic skeletal muscle is associated with protein oxidation causing inflammation and fibrosis (Valen et al., 2001), mitochondria damage (Jung et al., 2008), and sarco-endoplasmic reticulum stress (Bravo-Sagua et al., 2020), which further aggravates the already substantial diastolic Ca2+ overload. There is a close connection between intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and oxidative stress, and increasing evidence suggests close crosstalk between Ca2+ and ROS signaling systems, which fine-tunes cellular signaling networks (Gorlach et al., 2015). Thus, disruption of one system can severely impact the other, triggering a cascade of pathological signaling events, ultimately causing dysfunction, disease, or cell death. The mechanism by which high ROS production increases [Ca2+] is not fully understood; however, it seems to be mediated by augmented RyR leak and activation of plasmalemmal Ca2+ influx (Di et al., 2016). On the other hand, primary elevation of intracellular Ca2+ through RyR leak and/or an enhanced Ca2+ influx triggers ROS production by uncoupling mitochondrial function, reducing mitochondrial membrane potential (Hsu et al., 2016). The accumulated evidence suggests that the Ca2+ and ROS signaling pathways exhibit mutual and synergistic crosstalk with each other. Further experiments in mdx cardiomyocytes would be needed to corroborate this hypothesis.

The absence of dystrophin in mdx mice alters the dystrophin-associated protein complex making the plasma membrane more fragile to mechanical stress (Yasuda et al., 2005). The increased membrane fragility causes reduced cell viability (Lopez et al., 2017), which was demonstrated here both by reduced cardiomyocyte viability and elevated plasma cTNT levels.

The lack of dystrophin in the mdx mouse provokes the develops cardiac abnormalities causing progressive diastolic and systolic dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009) and subsequent cardiac contractile dysfunction (Sapp et al., 1996). In the present study, we found that mdx mice show a reduced contractile response compared to WT. The abnormal contractile response was manifested by a reduced peak shortening, maximal velocity of shortening, and relengthening. It had been shown that force amplitudes were markedly depressed in atrial and in papillary muscle cells from mdx mice compared with WT (Sapp et al., 1996; Janssen et al., 2005). A plausible explanation for the compromised contractile response in mdx cardiac cells could be the altered intracellular Ca2+ regulation.

WBPA Cardioprotection in mdx Mice With Cardiomyopathy

Extended lifespan in DMD patients has significantly increased recognition and development of cardiomyopathy. Although various curative and palliative therapeutic approaches, such as genetic and cellular, as well as pharmacologic therapies, are currently being investigated to treat DMD, these approaches are currently far from having a meaningful impact on the treatment of DMD patients (Bridges, 1986; Zincarelli et al., 2008; Popplewell et al., 2010; Wehling-Henricks et al., 2010; Schinkel et al., 2012; Zhang and Duan, 2012). Therefore, there are no effective treatments available for this devastating disease, and currently corticosteroids therapy still constitutes the primary treatment option for DMD patients, despite their serious side effects and a negligible effect in cardiomyopathy (Lu et al., 2005; Malik et al., 2012). Therefore, there is an increasing interest in developing DMD therapies that address dystrophin deficiency and target both cardiac and skeletal muscle. WBPA is an entirely different non-invasive and a non-pharmacologic approach that amplifies intracellular constitutive NO signaling (Wu et al., 2009; Uryash et al., 2015), provoking substantial benefit in excitable cells from mdx mice (Altamirano et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017, 2018). We have previously demonstrated that WBPA-elicited NO production alleviated the cardiomyopathy’s severity in mice lacking both dystrophin and utrophin protein expression (Lopez et al., 2017). In this study, we have extended previous findings presenting evidence that WBPA started at an age when the mice had an established cardiomyopathy provides cardioprotection in 15-month mdx mice.

In mdx mice, WBPA-elicited constitutive NO production decreased diastolic [Ca2+] and [Na+] overload. Although we do not precisely know the mechanisms by which WBPA improves Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis in mdx cardiomyocytes, could be linked to the NO-anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect (Uryash et al., 2015). It is well established that oxidative stress contributes to the cardiomyocyte damage in DMD (Jung et al., 2008). WBPA significantly increased the expression of endogenous antioxidants enzymes like glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase in the heart (Uryash et al., 2015). A reduction of oxidative stress may reduce the S-nitrosylation of the RyR2 diastolic SR Ca2+ leak (Fauconnier et al., 2010) and the TRPC channels resulting in a reduction of intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ overload. Furthermore, WBPA increases expression of p65 (major NF-κB subunit) and IκB-α (NF-κB repressor) in striated muscle (Altamirano et al., 2014). In this manuscript, we show that WBPA reduced ROS production in 15-month WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 3); those mice show an abnormal diastolic [Ca2+] [compared to 3-month WT (Mijares et al., 2014) and Supplementary Figure 1]. It is important to point out that WBPA did not modify [Ca2+]d and ROS generation in WT 3-month cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Figure 1). There is a close connection between intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and oxidative stress, and increasing evidence suggests close crosstalk between Ca2+ and ROS signaling systems, which fine-tunes cellular signaling networks (Gorlach et al., 2015).

Whole body periodic acceleration-elicited NO production induces upregulation of utrophin in mdx cardiomyocytes, which compensates for the absence of dystrophin in dystrophic muscle cells (Love et al., 1989). Utrophin is a fetal homolog of dystrophin expressed at the sarcolemma of immature striated muscle (Tome et al., 1994) and gradually is replaced by dystrophin in adult striated muscle cells (Karpati et al., 1993). The mechanisms by which NO induces upregulation of utrophin are not fully understood. One possibility is that WBPA-elicited production of NO would turn on the signal for fetal gene expression (Chaubourt et al., 1999). It is plausible to suggest that utrophin upregulation led to an increase of muscle function in dystrophic cardiomyocytes.

Here we demonstrated that a primary mechanism of action is through NOS mediated NO synthesis by showing that treatment of mdx mice with L-NAME, a non-selective inhibitor of NOS-synthase (Furfine et al., 1997), abolishes all beneficial effects WBPA on cardiomyocyte [Ca2+]d, and oxidative stress. Further studies are needed to study the downstream signaling involved in the cardioprotection caused by this essential bioregulatory molecule.

Study Limitations

Despite the novel finding that WBPA mitigates some of the aberrations observed in mdx with established cardiomyopathy, some study limitations must be pointed out. We report that physiological enhancement of NO by WBPA induced upregulation of utrophin in mdx cardiomyocytes which elicited a partial correction of some of the observed cardiomyocyte pathological abnormalities. However, mechanism/s by which WBPA induced its effects were not explored. Another limitation of this study is that we demonstrated that an NO antagonist (L-NAME) blocks the cardioprotective effect of WBPA of lowering diastolic [Ca2+] and ROS production, suggesting that NO-mediates the beneficial effect; however, the undelaying mechanism was not determined, and the effects of L-NAME on utrophin expression was not studied. We have also only addressed diastolic Ca2+ dysfunction and not systolic, which would allow for additional estimation of the cardioprotection induced by WBPA. Finally, this study did not address a longer time of exposure (more than 1 h) or greater number of days (more than 90 days) of WBPA.

Conclusion

Although the mechanism by which WBPA induced the observed cardioprotection has not been established yet, the observed benefits of WBPA could be related to the direct effect of NO on ionic channels (Meszaros et al., 1996; Zahradnikova et al., 1997), its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (Uryash et al., 2015), its ability to enhance cellular repair (Anderson, 2000; Filippin et al., 2011), as well as its potential to upregulate the expression of structural plasma membrane proteins like utrophin (Altamirano et al., 2014). Whatever the precise mechanism, from the data presented here, we conclude that WBPA represents a promising therapy for preventing and/or treating DMD cardiomyopathy. This conclusion is supported by the fact that 3-month treatment with WBPA slows the development of cardiomyopathy in mdx 15-month old mice by normalizing intracellular ion dyshomeostasis, reducing intracellular ROS production and cell injury, which enhances contractile function and increases cell viability. WBPA as a therapeutic approach to treat DMD has some advantages compared with current available treatments; (1) WBPA is not a pharmacological approach, therefore no toxicology and preclinical pharmacokinetic studies are required before its use in patients; (2) is easily translated from being a research platform to patients; (3) It is non-invasive, non-stressful and able to be used even in those with physical limitations; (4) No side effects have been observed in experimental models of DMD and other diseases (Adams et al., 2014; Altamirano et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2017, 2018; Sabater et al., 2019) as well as in various human clinical trials on non-DMD patients (Sackner et al., 2004; Kohler et al., 2007; Rokutanda et al., 2011; Sakaguchi et al., 2012; Serravite et al., 2014; Adams et al., 2020); (5) WBPA not only protects and improves function in cardiac cells but also has a similar effect in skeletal muscle (Altamirano et al., 2014) and in neurons (Lopez et al., 2018) all of which are affected in DMD.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the University of California, Davis (Protocol number: #17298) and Mount Sinai Medical Center (Protocol number: #14-22-A-04).

Author Contributions

AU, AM, and JRL performed the research. AU, AM, EE, JA, and JRL analyzed the data. JRL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the AFM-Téléthon – France (Grant No. 21543), Innovative Development Award, University of California, Davis, United States, Philippe Foundation Inc., Paris, France, and Florida Heart Research Foundation, Florida, United States.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. D. Allen for his comments on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.658042/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Effects of WBPA on [Ca2+]d and ROS generation in cardiomyocytes from young WT and mdx mice. [Ca2+]d and ROS production were evaluated in cardiomyocytes from 3-month WBPA-treated and untreated WT and mdx dystrophin-deficient mice. (A) [Ca2+]d was 1.2-fold more elevated in mdx cardiomyocytes than WT. WBPA treatment normalized [Ca2+]d in mdx cardiomyocytes compared to untreated WT (p = 0.08), with no effect on WT cardiomyocytes. (B) Intracellular ROS was 2.1-fold higher in mdx cardiomyocytes than WT. WBPA treatment normalized intracellular ROS production in mdx cardiomyocytes compared to untreated WT (p = 0.5), with no effect on WT. [Ca2+]d measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental condition, n = 17–18, respectively; Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 3 mice, n = 17–19, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, NS p > 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001. ROS measurements: Untreated and WBPA-treated WT, N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 15. Untreated and WBPA-treated mdx N = 3 mice per experimental conditions, n = 19–20, respectively. Values are expressed as means ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, NS p > 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

References

Adamo, C. M., Dai, D. F., Percival, J. M., Minami, E., Willis, M. S., Patrucco, E., et al. (2010). Sildenafil reverses cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19079–19083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013077107

Adams, J. A., Banderas, V., Lopez, J. R., and Sackner, M. A. (2020). Portable Gentle Jogger improves glycemic indices in type 2 diabetic and healthy subjects living at home: a pilot study. J. Diabetes Res. 2020:8317973. doi: 10.1155/2020/8317973

Adams, J. A., Uryash, A., Bassuk, J., Sackner, M. A., and Kurlansky, P. (2014). Biological basis of neuroprotection and neurotherapeutic effects of whole body periodic acceleration (pGz). Med. Hypotheses 82, 681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.02.031

Adams, J. A., Wu, H., Bassuk, J. A., Arias, J., Uryash, A., and Kurlansky, P. (2009). Periodic acceleration (pGz) acutely increases endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression in endomyocardium of normal swine. Peptides 30, 373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.10.014

Allen, D. G., Gervasio, O. L., Yeung, E. W., and Whitehead, N. P. (2010a). Calcium and the damage pathways in muscular dystrophy. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 88, 83–91. doi: 10.1139/Y09-058

Allen, D. G., Zhang, B. T., and Whitehead, N. P. (2010b). Stretch-induced membrane damage in muscle: comparison of wild-type and mdx mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 682, 297–313. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6366-6_17

Altamirano, F., Perez, C. F., Liu, M., Widrick, J., Barton, E. R., Allen, P. D., et al. (2014). Whole body periodic acceleration is an effective therapy to ameliorate muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. PLoS One 9:e106590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106590

Anderson, J. E. (2000). A role for nitric oxide in muscle repair: nitric oxide-mediated activation of muscle satellite cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 1859–1874. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1859

Bellinger, A. M., Reiken, S., Carlson, C., Mongillo, M., Liu, X., Rothman, L., et al. (2009). Hypernitrosylated ryanodine receptor calcium release channels are leaky in dystrophic muscle. Nat. Med. 15, 325–330. doi: 10.1038/nm.1916

Bravo-Sagua, R., Parra, V., Munoz-Cordova, F., Sanchez-Aguilera, P., Garrido, V., Contreras-Ferrat, A., et al. (2020). Sarcoplasmic reticulum and calcium signaling in muscle cells: homeostasis and disease. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 350, 197–264. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2019.12.007

Bridges, L. R. (1986). The association of cardiac muscle necrosis and inflammation with the degenerative and persistent myopathy of MDX mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 72, 147–157. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(86)90003-1

Bylo, M., Farewell, R., Coppenrath, V. A., and Yogaratnam, D. (2020). A review of deflazacort for patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Pharmacother. 54, 788–794. doi: 10.1177/1060028019900500

Cerletti, M., Negri, T., Cozzi, F., Colpo, R., Andreetta, F., Croci, D., et al. (2003). Dystrophic phenotype of canine X-linked muscular dystrophy is mitigated by adenovirus-mediated utrophin gene transfer. Gene Ther. 10, 750–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301941

Chaubourt, E., Fossier, P., Baux, G., Leprince, C., Israel, M., and De La Porte, S. (1999). Nitric oxide and l-arginine cause an accumulation of utrophin at the sarcolemma: a possible compensation for dystrophin loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 6, 499–507. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0256

Chung, H. S., Kim, G. E., Holewinski, R. J., Venkatraman, V., Zhu, G., Bedja, D., et al. (2017). Transient receptor potential channel 6 regulates abnormal cardiac S-nitrosylation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E10763–E10771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712623114

de Arcangelis, V., Strimpakos, G., Gabanella, F., Corbi, N., Luvisetto, S., Magrelli, A., et al. (2016). Pathways implicated in tadalafil amelioration of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Cell. Physiol. 231, 224–232. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25075

Di, A., Mehta, D., and Malik, A. B. (2016). ROS-activated calcium signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial barrier function. Cell Calcium 60, 163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.02.002

Eltit, J. M., Ding, X., Pessah, I. N., Allen, P. D., and Lopez, J. R. (2013). Nonspecific sarcolemmal cation channels are critical for the pathogenesis of malignant hyperthermia. FASEB J. 27, 991–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218354

Fauconnier, J., Thireau, J., Reiken, S., Cassan, C., Richard, S., Matecki, S., et al. (2010). Leaky RyR2 trigger ventricular arrhythmias in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1559–1564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908540107

Fayssoil, A., Abasse, S., and Silverston, K. (2017). Cardiac involvement classification and therapeutic management in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 4, 17–23. doi: 10.3233/JND-160194

Filippin, L. I., Cuevas, M. J., Lima, E., Marroni, N. P., Gonzalez-Gallego, J., and Xavier, R. M. (2011). Nitric oxide regulates the repair of injured skeletal muscle. Nitric Oxide 24, 43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.11.003

Fujita, M., Tambara, K., Ikemoto, M., Sakamoto, S., Ogai, A., Kitakaze, M., et al. (2005). Periodic acceleration enhances release of nitric oxide in healthy adults. Int. J. Angiol. 14, 11–14. doi: 10.1007/s00547-005-2013-2

Furfine, E. S., Carbine, K., Bunker, S., Tanoury, G., Harmon, M., Laubach, V., et al. (1997). Potent inhibition of human neuronal nitric oxide synthase by N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester results from contaminating N(G)-nitro-L-arginine. Life Sci. 60, 1803–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)00140-9

Gorlach, A., Bertram, K., Hudecova, S., and Krizanova, O. (2015). Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 6, 260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010

Holmstrom, K. M., and Finkel, T. (2014). Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801

Hafner, P., Bonati, U., Klein, A., Rubino, D., Gocheva, V., Schmidt, S., et al. (2019). Effect of combination l-citrulline and metformin treatment on motor function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2:e1914171. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14171

Hoffman, E. P., Brown, R. H. Jr., and Kunkel, L. M. (1987). Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 51, 919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4

Hsu, S. S., Chou, C. T., Liao, W. C., Shieh, P., Kuo, D. H., Kuo, C. C., et al. (2016). The effect of gallic acid on cytotoxicity, Ca(2+) homeostasis and ROS production in DBTRG-05MG human glioblastoma cells and CTX TNA2 rat astrocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 252, 61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.04.010

Janssen, P. M., Hiranandani, N., Mays, T. A., and Rafael-Fortney, J. A. (2005). Utrophin deficiency worsens cardiac contractile dysfunction present in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H2373–H2378. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00448.2005

Jung, C., Martins, A. S., Niggli, E., and Shirokova, N. (2008). Dystrophic cardiomyopathy: amplification of cellular damage by Ca2+ signalling and reactive oxygen species-generating pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 77, 766–773. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm089

Kaczor, J. J., Hall, J. E., Payne, E., and Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2007). Low intensity training decreases markers of oxidative stress in skeletal muscle of mdx mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.003

Kamdar, F., and Garry, D. J. (2016). Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2533–2546. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.081

Kamogawa, Y., Biro, S., Maeda, M., Setoguchi, M., Hirakawa, T., Yoshida, H., et al. (2001). Dystrophin-deficient myocardium is vulnerable to pressure overload in vivo. Cardiovasc. Res. 50, 509–515. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00205-X

Karpati, G., Carpenter, S., Morris, G. E., Davies, K. E., Guerin, C., and Holland, P. (1993). Localization and quantitation of the chromosome 6-encoded dystrophin-related protein in normal and pathological human muscle. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 52, 119–128. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199303000-00004

Kohler, M., Amann-Vesti, B. R., Clarenbach, C. F., Brack, T., Noll, G., Russi, E. W., et al. (2007). Periodic whole body acceleration: a novel therapy for cardiovascular disease. Vasa 36, 261–266. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.36.4.261

Lampson, B. L., Kendall, S. D., Ancrile, B. B., Morrison, M. M., Shealy, M. J., Barrientos, K. S., et al. (2012). Targeting eNOS in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 72, 4472–4482. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0057

Li, W., Liu, W., Zhong, J., and Yu, X. (2009). Early manifestation of alteration in cardiac function in dystrophin deficient mdx mouse using 3D CMR tagging. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 11:40. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-40

Liao, R., and Jain, M. (2007). Isolation, culture, and functional analysis of adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Methods Mol. Med. 139, 251–262. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-571-8_16

Lopez, J. R., Alamo, L., Caputo, C., Dipolo, R., and Vergara, S. (1983). Determination of ionic calcium in frog skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 43, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84316-1

Lopez, J. R., Briceno, L. E., Sanchez, V., and Horvart, D. (1987). Myoplasmic (Ca2+) in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Acta Cient. Venez. 38, 503–504.

Lopez, J. R., Contreras, J., Linares, N., and Allen, P. D. (2000). Hypersensitivity of malignant hyperthermia-susceptible swine skeletal muscle to caffeine is mediated by high resting myoplasmic [Ca2+]. Anesthesiology 92, 1799–1806. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200006000-00040

Lopez, J. R., Kolster, J., Uryash, A., Esteve, E., Altamirano, F., and Adams, J. A. (2016). Dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ in dystrophic cortical and hippocampal neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 603–618. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0311-7

Lopez, J. R., Kolster, J., Zhang, R., and Adams, J. (2017). Increased constitutive nitric oxide production by whole body periodic acceleration ameliorates alterations in cardiomyocytes associated with utrophin/dystrophin deficiency. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 108, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.06.004

Lopez, J. R., Uryash, A., Faury, G., Esteve, E., and Adams, J. A. (2020). Contribution of TRPC channels to intracellular Ca(2 +) dyshomeostasis in smooth muscle from mdx mice. Front. Physiol. 11:126. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00126

Lopez, J. R., Uryash, A., Kolster, J., Esteve, E., Zhang, R., and Adams, J. A. (2018). Enhancing endogenous nitric oxide by whole body periodic acceleration elicits neuroprotective effects in dystrophic neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 8680–8694. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1018-8

Love, D. R., Hill, D. F., Dickson, G., Spurr, N. K., Byth, B. C., Marsden, R. F., et al. (1989). An autosomal transcript in skeletal muscle with homology to dystrophin. Nature 339, 55–58. doi: 10.1038/339055a0

Lu, Q. L., Rabinowitz, A., Chen, Y. C., Yokota, T., Yin, H., Alter, J., et al. (2005). Systemic delivery of antisense oligoribonucleotide restores dystrophin expression in body-wide skeletal muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406700102

Malik, V., Rodino-Klapac, L. R., and Mendell, J. R. (2012). Emerging drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 17, 261–277. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.691965

Marques, M. J., Luz, M. A., Minatel, E., and Neto, H. S. (2005). Muscle regeneration in dystrophic mdx mice is enhanced by isosorbide dinitrate. Neurosci. Lett. 382, 342–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.023

Mavrogeni, S. I., Markousis-Mavrogenis, G., Papavasiliou, A., Papadopoulos, G., and Kolovou, G. (2018). Cardiac involvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and related dystrophinopathies. Methods Mol. Biol. 1687, 31–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7374-3_3

Mazur, W., Hor, K. N., Germann, J. T., Fleck, R. J., Al-Khalidi, H. R., Wansapura, J. P., et al. (2012). Patterns of left ventricular remodeling in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cardiac MRI study of ventricular geometry, global function, and strain. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 28, 99–107. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9781-2

Meszaros, L. G., Minarovic, I., and Zahradnikova, A. (1996). Inhibition of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor calcium release channel by nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 380, 49–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00003-8

Miglietta, D., De Palma, C., Sciorati, C., Vergani, B., Pisa, V., Villa, A., et al. (2015). Naproxcinod shows significant advantages over naproxen in the mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10:101. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0311-0

Mijares, A., Altamirano, F., Kolster, J., Adams, J. A., and Lopez, J. R. (2014). Age-dependent changes in diastolic Ca(2+) and Na(+) concentrations in dystrophic cardiomyopathy: role of Ca(2+) entry and IP3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 452, 1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.045

Muntoni, F., Valero De Bernabe, B., Bittner, R., Blake, D., Van Bokhoven, H., Brockington, M., et al. (2003). 114th ENMC International workshop on congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) 17-19 January 2003, Naarden, The Netherlands: (8th Workshop of the International Consortium on CMD; 3rd Workshop of the MYO-CLUSTER project GENRE). Neuromuscul. Disord. 13, 579–588. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(03)00072-5

Nabeebaccus, A., Zhang, M., and Shah, A. M. (2011). NADPH oxidases and cardiac remodelling. Heart Fail. Rev. 16, 5–12. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9186-2

Nelson, M. D., Rader, F., Tang, X., Tavyev, J., Nelson, S. F., Miceli, M. C., et al. (2014). PDE5 inhibition alleviates functional muscle ischemia in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 82, 2085–2091. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000498

Palmer, R. M., and Moncada, S. (1989). A novel citrulline-forming enzyme implicated in the formation of nitric oxide by vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 158, 348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80219-0

Paravicini, T. M., and Touyz, R. M. (2008). NADPH oxidases, reactive oxygen species, and hypertension: clinical implications and therapeutic possibilities. Diabetes Care 31(Suppl. 2), S170–S180. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s247

Passamano, L., Taglia, A., Palladino, A., Viggiano, E., D’ambrosio, P., Scutifero, M., et al. (2012). Improvement of survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: retrospective analysis of 835 patients. Acta Myol. 31, 121–125.

Percival, J. M., Whitehead, N. P., Adams, M. E., Adamo, C. M., Beavo, J. A., and Froehner, S. C. (2012). Sildenafil reduces respiratory muscle weakness and fibrosis in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Pathol. 228, 77–87. doi: 10.1002/path.4054

Popplewell, L. J., Adkin, C., Arechavala-Gomeza, V., Aartsma-Rus, A., De Winter, C. L., Wilton, S. D., et al. (2010). Comparative analysis of antisense oligonucleotide sequences targeting exon 53 of the human DMD gene: implications for future clinical trials. Neuromuscul. Disord. 20, 102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.10.013

Ramachandran, J., Schneider, J. S., Crassous, P. A., Zheng, R., Gonzalez, J. P., Xie, L. H., et al. (2013). Nitric oxide signalling pathway in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice: up-regulation of L-arginine transporters. Biochem. J. 449, 133–142. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120787

Rodriguez, M. C., and Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2003). Patients with dystrophinopathy show evidence of increased oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 1217–1220. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00141-2

Rokutanda, T., Izumiya, Y., Miura, M., Fukuda, S., Shimada, K., Izumi, Y., et al. (2011). Passive exercise using whole-body periodic acceleration enhances blood supply to ischemic hindlimb. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 2872–2880. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229773

Sabater, J. R., Sackner, M. A., Adams, J. A., and Abraham, W. M. (2019). Whole body periodic acceleration in normal and reduced mucociliary clearance of conscious sheep. PLoS One 14:e0224764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224764

Sackner, M. A., Gummels, E., and Adams, J. A. (2005a). Effect of moderate-intensity exercise, whole-body periodic acceleration, and passive cycling on nitric oxide release into circulation. Chest 128, 2794–2803. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2794

Sackner, M. A., Gummels, E., and Adams, J. A. (2005b). Nitric oxide is released into circulation with whole-body, periodic acceleration. Chest 127, 30–39.

Sackner, M. A., Gummels, E. M., and Adams, J. A. (2004). Say NO to fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: an alternative and complementary therapy to aerobic exercise. Med. Hypotheses 63, 118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.01.025

Sakaguchi, M., Fukuda, S., Shimada, K., Izumi, Y., Izumiya, Y., Nakamura, Y., et al. (2012). Preliminary observations of passive exercise using whole body periodic acceleration on coronary microcirculation and glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Cardiol. 60, 283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.05.006

Sanyal, S. K., and Johnson, W. W. (1982). Cardiac conduction abnormalities in children with Duchenne’s progressive muscular dystrophy: electrocardiographic features and morphologic correlates. Circulation 66, 853–863. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.66.4.853

Sapp, J. L., Bobet, J., and Howlett, S. E. (1996). Contractile properties of myocardium are altered in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 142, 17–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(96)00167-0

Schinkel, S., Bauer, R., Bekeredjian, R., Stucka, R., Rutschow, D., Lochmuller, H., et al. (2012). Long-term preservation of cardiac structure and function after adeno-associated virus serotype 9-mediated microdystrophin gene transfer in mdx mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 23, 566–575. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.017

Serravite, D. H., Perry, A., Jacobs, K. A., Adams, J. A., Harriell, K., and Signorile, J. F. (2014). Effect of whole-body periodic acceleration on exercise-induced muscle damage after eccentric exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 9, 985–992. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0512

Tinsley, J., Deconinck, N., Fisher, R., Kahn, D., Phelps, S., Gillis, J. M., et al. (1998). Expression of full-length utrophin prevents muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Nat. Med. 4, 1441–1444. doi: 10.1038/4033

Tome, F. M., Matsumura, K., Chevallay, M., Campbell, K. P., and Fardeau, M. (1994). Expression of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins during human fetal muscle development: a preliminary immunocytochemical study. Neuromuscul. Disord. 4, 343–348. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)90070-1

Townsend, D., Yasuda, S., Chamberlain, J., and Metzger, J. M. (2009). Cardiac consequences to skeletal muscle-centric therapeutics for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 19, 50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.04.006

Uryash, A., Bassuk, J., Kurlansky, P., Altamirano, F., Lopez, J. R., and Adams, J. A. (2015). Antioxidant properties of whole body periodic acceleration (pGz). PLoS One 10:e0131392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131392

Uryash, A., Wu, H., Bassuk, J., Kurlansky, P., Sackner, M. A., and Adams, J. A. (2009). Low-amplitude pulses to the circulation through periodic acceleration induces endothelial-dependent vasodilatation. J. Appl. Physiol. 106, 1840–1847. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91612.2008

Valen, G., Yan, Z. Q., and Hansson, G. K. (2001). Nuclear factor kappa-B and the heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 38, 307–314. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01377-8

Vianello, S., Yu, H., Voisin, V., Haddad, H., He, X., Foutz, A. S., et al. (2013). Arginine butyrate: a therapeutic candidate for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 27, 2256–2269. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-215723

Victor, R. G., Sweeney, H. L., Finkel, R., Mcdonald, C. M., Byrne, B., Eagle, M., et al. (2017). A phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial of tadalafil for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 89, 1811–1820. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004570

Wang, Q., Wang, W., Wang, G., Rodney, G. G., and Wehrens, X. H. (2015). Crosstalk between RyR2 oxidation and phosphorylation contributes to cardiac dysfunction in mice with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 89, 177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.009

Wehling-Henricks, M., Jordan, M. C., Gotoh, T., Grody, W. W., Roos, K. P., and Tidball, J. G. (2010). Arginine metabolism by macrophages promotes cardiac and muscle fibrosis in mdx muscular dystrophy. PLoS One 5:e10763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010763

Williams, I. A., and Allen, D. G. (2007a). Intracellular calcium handling in ventricular myocytes from mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H846–H855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00688.2006

Williams, I. A., and Allen, D. G. (2007b). The role of reactive oxygen species in the hearts of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H1969–H1977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00489.2007

Wu, F., Yu, B., Zhang, X., and Zhang, Y. (2017). Cardioprotective effect of Notch signaling on the development of myocardial infarction complicated by diabetes mellitus. Exp. Ther. Med. 14, 3447–3454. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4932

Wu, H., Jin, Y., Arias, J., Bassuk, J., Uryash, A., Kurlansky, P., et al. (2009). In vivo upregulation of nitric oxide synthases in healthy rats. Nitric Oxide 21, 63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.05.004

Wussling, M., Schenk, W., and Nilius, B. (1987). A study of dynamic properties in isolated myocardial cells by the laser diffraction method. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 19, 897–907. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2828(87)80618-1

Yasuda, S., Townsend, D., Michele, D. E., Favre, E. G., Day, S. M., and Metzger, J. M. (2005). Dystrophic heart failure blocked by membrane sealant poloxamer. Nature 436, 1025–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature03844

Zahradnikova, A., Minarovic, I., Venema, R. C., and Meszaros, L. G. (1997). Inactivation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor calcium release channel by nitric oxide. Cell Calcium 22, 447–454. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4160(97)90072-5

Zhang, W., ten Hove, M., Schneider, J. E., Stuckey, D. J., Sebag-Montefiore, L., Bia, B. L., et al. (2008). Abnormal cardiac morphology, function and energy metabolism in the dystrophic mdx mouse: an MRI and MRS study. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45, 754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.125

Zhang, Y., and Duan, D. (2012). Novel mini-dystrophin gene dual adeno-associated virus vectors restore neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression at the sarcolemma. Hum. Gene Ther. 23, 98–103. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.131

Keywords: Duchenne cardiomyopathy, calcium, oxidative stress, cardiac contractility, utrophin, l-name

Citation: Uryash A, Mijares A, Esteve E, Adams JA and Lopez JR (2021) Cardioprotective Effect of Whole Body Periodic Acceleration in Dystrophic Phenotype mdx Rodent. Front. Physiol. 12:658042. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.658042

Received: 26 January 2021; Accepted: 09 April 2021;

Published: 04 May 2021.

Edited by:

Guillermo Avila, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional (CINVESTAV), MexicoReviewed by:

Semir Özdemir, Akdeniz University, TurkeyGerardo García-Rivas, Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM), Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Uryash, Mijares, Esteve, Adams and Lopez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jose R. Lopez, bG9wZXpwYWRyaW5vQGljbG91ZC5jb20=; am9zZXIubG9wZXpAbXNtYy5jb20=

Arkady Uryash1

Arkady Uryash1 Alfredo Mijares

Alfredo Mijares Eric Esteve

Eric Esteve Jose R. Lopez

Jose R. Lopez