- 1Guangdong Engineering Research Center for Pesticide and Fertilizer, Institute of Bioengineering, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, China

- 2College of Horticulture and Plant Protection, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, China

Insect chemoreception involves many families of genes, including odourant/pheromone binding proteins (OBP/PBPs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), odourant receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), and sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs), which play irreplaceable roles in mediating insect behaviors such as host location, foraging, mating, oviposition, and avoidance of danger. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism of olfactory reception in Chilo sacchariphagus, which is a major pest of sugarcane. A set of 72 candidate chemosensory genes, including 31 OBPs/PBPs, 15 CSPs, 11 ORs, 13 IRs, and two SNMPs, were identified in four transcriptomes from different tissues and genders of C. sacchariphagus. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted on gene families and paralogs from other model insect species. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that most of these chemosensory genes exhibited antennae-biased expression, but some had high expression in bodies. Most of the identified chemosensory genes were likely involved in chemoreception. This study provides a molecular foundation for the function of chemosensory proteins, and an opportunity for understanding how C. sacchariphagus behaviors are mediated via chemical cues. This research might facilitate the discovery of novel strategies for pest management in agricultural ecosystems.

Introduction

Insects, the most diverse and successful group of animals on earth, have existed for more than 350 million years (Stork, 1993; Chen et al., 2018); they not only affect the natural environment but also influence human life and productivity in many ways. A sophisticated chemosensory system makes insect prominence among other animals for their survival and reproduction (Leal, 2013). Chemoreception plays a critical role in many insect behaviors, including behaviors to avoid harm from predators or the surrounding environment, behaviors to detect locations for oviposition or hosts, searching for food or mates, and interspecific communication (Stocker, 1994; Hildebrand, 1995; Grosse-Wilde et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2015). The recognition of chemical signals depends on peripheral chemosensory systems (Vieira and Rozas, 2011; Zhang et al., 2016). External chemical ligands are recognized by binding and membrane receptor proteins located in the antennae, which have many kinds of sensilla, and then translated into electrical signals to the central nervous system (Robertson et al., 2003; Ramdya and Benton, 2010). Chemoreception in insects is mediated via many proteins, including odourant binding proteins (OBPs), pheromone binding proteins (PBPs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), odourant receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), and sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) (Leal, 2013; Pelosi et al., 2014, 2018; Wicher, 2014; Butterwick et al., 2018; He et al., 2019b).

Insect OBPs, small water-soluble proteins with molecular masses of approximately 14 kDa that were first found in Antheraea polyphemus (Vogt and Riddiford, 1981), are present at high concentrations in the sensillum lymph (Vogt and Riddiford, 1981; Pelosi et al., 2006). OBPs act as a liaison between external chemicals and ORs (Leal, 2005), recognizing hydrophobic odourants and delivering them to olfactory receptors (ORs) on olfactory sensory neurone (OSN) membranes (Pelosi et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2009; Leal, 2013), which is the first and key step in the process of olfaction. CSPs, which were found to be soluble binding proteins (Gong et al., 2007), are abundant in the sensillum lymph (Vogt and Riddiford, 1981; Prestwich, 1996; Pophof, 2004; Grosse-Wilde et al., 2006; Lautenschlager et al., 2007; Leal, 2007; Laughlin et al., 2008; Kaissling, 2009) and also expressed in many organs and tissues, such as antennae, wings, legs, maxillary palps, and labial palps, with the function of affecting chemoreception (Jacquinjoly et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2005; González et al., 2009; Pelletier and Leal, 2011; Gu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). PBPs, a kind of special odor-binding protein that can dissolve and transport fat-soluble pheromones through hydrophilic lymph (Vogt and Riddiford, 1981; Wojtasek and Leal, 1999), are expressed around the time of eclosion (Gyorgyi et al., 1988).

Insect ORs, a member of a novel family of seven-transmembrane proteins located in the dendrite membrane of OSNs with a reversed membrane topology compared to that of G-protein coupled vertebrate ORs (intracellular N-terminus and extracellular C-terminus) (Clyne et al., 1999; Benton et al., 2006), were first found and identified in Drosophila melanogaster (Clyne et al., 1999; Vosshall et al., 1999). In the process of insect olfactory signal transduction, OR and ORCO form a complex of odourant-gated ion channels that play a fundamental role in the conversion of chemical signals to electrical signals (Larsson et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2008; Smart et al., 2008; Wicher et al., 2008; Butterwick et al., 2018; Fandino et al., 2019).

Ionotropic receptors, belonging to the ionotropic glutamate receptor (iGluR) family of ion channels with three transmembrane domains (M1, M2, and M3), have been shown to be involved in chemosensation (Benton et al., 2009; Croset et al., 2010; Abuin et al., 2011; Bengtsson et al., 2012; Andersson et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2020). Two or three IR genes were co-expressed in an IR-expressing neuron (Benton et al., 2009). IRs are extensively distributed in many insect species, including D. melanogaster, Cydia pomonella, Chrysoperla sinica, Bactrocera dorsalis, and Dendroctonus valens (Benton et al., 2009; Bengtsson et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015), and show relatively high homology across species (Chiu et al., 1999). In insects, IRs are thought to be used for sensing chemicals in the surrounding environment and function during the process of taste perception (Chiu et al., 1999; Benton et al., 2009; Croset et al., 2010).

Sensory neuron membrane proteins, located on dendrite cilia in insects, belong to the CD36 family of two-transmembrane domain membrane proteins (Rogers et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2016). Insect SNMPs can usually be divided into two subfamilies: SNMP1 and SNMP2, while in a recent study, SNMP3 has been found in lepidopteran. SNMP1, with specific expression on pheromone-specific OSNs in the insect antennae, was thought to have a pheromone detection function (Vogt et al., 2009); the function of SNMP2 has not yet been clarified; while is specifically SNMP3 is biased-expressed in the larval midgut, which may be involved in functioning immunity response to virus and bacterial infections the silkworm (Zhang et al., 2020).

Chilo sacchariphagus Bojeris, a lepidopteran of the Pyralidae family, is one of the most dangerous pests for sugarcane. Their larvae cause damage by mining the seedlings and stems of sugarcane; this species also harms sorghum, corn and other crops. C. sacchariphagus causes great economic losses to the sugar industry every year in China, as well as in South Africa, India, Swaziland, and other countries and regions (Bezuidenhout et al., 2008; Geetha et al., 2010). At present, research on the sugarcane cane borer is mainly focused on identifying resistant varieties, determining the resistance mechanisms of sugarcane and developing biological control techniques (including the utilization of Trichogramma chilonis Ishii, pheromones, and pathogenic nematodes) (Nibouche and Tibère, 2010; Nibouche et al., 2012; Sallam et al., 2016). Chemoreception plays an irreplaceable role in the foraging, mating, oviposition and other behaviors of C. sacchariphagus, which are vital for its survival in the natural environment. However, few reports have been published on this topic, including on the characterization and function of chemosensory genes and the mechanisms of chemosensory recognition.

In this study, we sequenced and analyzed the C. sacchariphagus adult antennal transcriptomes using the Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform. Seventy-two chemoreception-related genes were identified in total, including 31 OBP/PBPs, 15 CSPs, 11 ORs, 13 IRs, and two SNMPs, by analyzing the transcriptome data. Our aim was to identify chemoreception-related genes in this pest insect species, which is destructive to the sugarcane production and sugar industry in China, across Asia and in the Pacific and India. We intend to provide a theory for an improved understanding of how C. sacchariphagus recognizes, locates, forages, and mates.

Materials and Methods

Insects

The eggs of C. sacchariphagus, obtained from a wild field, were reared at 27 ± 1°C with 75 ± 5% relative humidity and a 14 L:10 D photoperiod at Guangdong Engineering Research Center for Pesticide and Fertilizer, Institute of Bioengineering, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, China. Larvae were reared on an artificial diet under the same conditions. After at least three generations, newly emerged male and female adult C. sacchariphagus were chosen as experimental subjects. After pupation, male and female pupae were separated and fed with 10% sugar solution. Antennae of unmated male and female individuals were collected 2 days after eclosion, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Antennae with intact structure were removed using tweezers.

cDNA Library Construction, Transcriptome Sequencing, Assembly and Functional Annotation

Twenty pairs of antennae and 20 body tissues (without antennae) from male and female of C. sacchariphagus were used for RNA extraction. For each sample, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNase-free DNase I (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) was used to remove contaminating genomic DNA. The quantity and quality of RNA were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and on a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, United States). RNA with high purity, concentration and integrity was chosen for cDNA library construction and final Illumina sequencing at Gene Denovo Biotechnology Company (Guangzhou, China). The cDNA was then tested for quality and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform as 150 bp paired-end reads.

The obtained raw reads were processed to remove adapters, primers, low-quality sequences, and ambiguous “N” nucleotides. Then, quality assessment of the clean data was carried out by Q30, and the GC content and sequence duplication level were calculated. Clean data were assembled into contigs using Trinity software and subsequently assembled into transcripts using the De Bruijn graph method. The assembled transcripts were further clustered to form unigenes by using the TGI Clustering Tool (Quackenbush et al., 2001; Pertea et al., 2003).

The annotation of all unigenes was performed by BLASTx against a pooled database containing protein entries from the National Center for Biotechnology Information non-redundant protein (NCBI-NR), Swiss-Prot, Gene Ontology (GO), Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases with an E-value < 10–5. After amino acid sequence prediction, annotation of unigenes was obtained using HMMER software (Eddy, 1998), and Gene Ontology (GO) annotations were determined by Blast2GO. In addition, WEGO (Ye et al., 2006) was utilized to perform GO functional classification and evaluate the distribution of gene functions at the macro level. Unigene functions were also predicted by aligning their sequences with the COG database.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The amino acid sequence alignment of the candidate chemosensory-related genes of C. sacchariphagus was performed using CLUSTALX 2.0 (Larkin et al., 2007). The candidate OBPs, PBPs, CSPs, ORs, IRs, and SNMPs of C. sacchariphagus were chosen for phylogenetic analysis along with genes from model organisms Lepidoptera (Manduca sexta and Bombyx mori), Diptera (D. melanogaster), and Hymenoptera (Apis mellifera) species. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method, as implemented in MEGA6.0 software. Node support was assessed using a bootstrap procedure with 1000 replicates (Tamura et al., 2013). Phylogenetic trees were colored and arranged using FigTree (Version: 1.4.2).

Expression Analysis by Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to verify the expression of candidate chemosensory genes. Tissue samples were collected from C. sacchariphagus adults 2 days after eclosion in three biological replicates, and total RNA was extracted as described above. One microgram of total RNA from the transcriptome samples was subjected to reverse transcription in a total reaction volume of 20 μL according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit, Takara, Japan) to obtain the first-strand cDNAs. With the manual for the SYBR Green I Master (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Lewes, United Kingdom), qRT-PCR was processed in 10 μL reaction volumes [1 μL cDNA (2 ng/μL), 5 μL SYBR Green I Master, 0.5 μL/primer, and 3 μL ddH2O] on a LightCycler® 480 real-time PCR system (Roche Diagnostics Ltd.) with the following program: denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and 20 s at 72°C. β-actin was used as the internal reference gene, and each gene was tested in triplicate. The relative expression levels of the candidate chemosensory genes normalized to the internal control gene were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Results

Overview of Transcriptomes

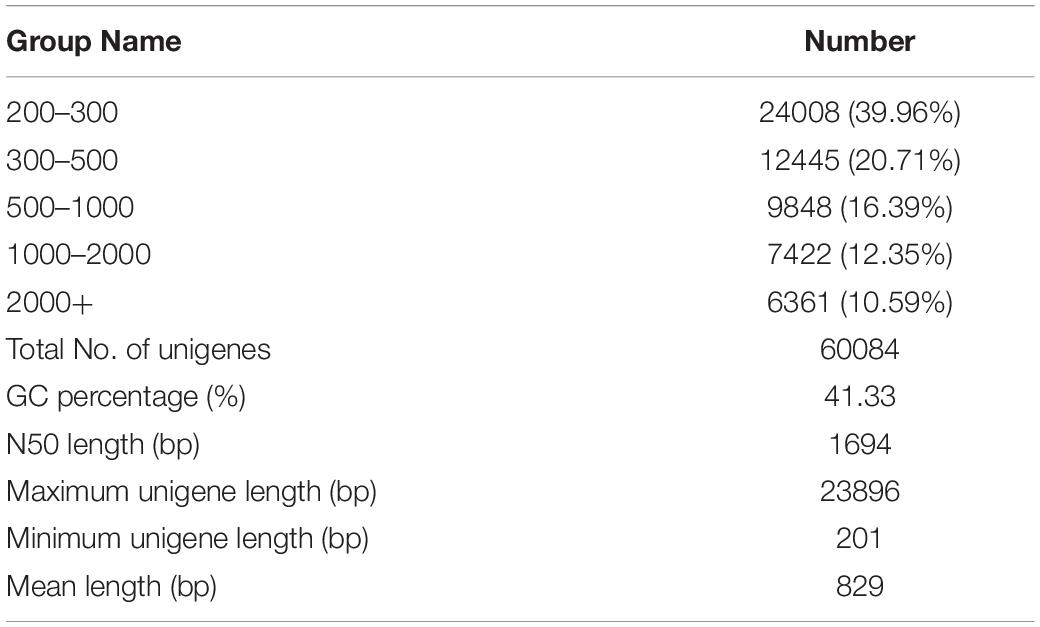

After sequencing and a subsequent quality control process, a total of 16.60 Gb of clean data were obtained from four libraries (CT: antennae of female, CS: body of female, XT: antennae of male, XS: body of male). All the transcriptome libraries generated 231891488 raw reads. A total of 57757438, 61860942, 64297952, and 47525880 clean reads were obtained for CT, CS, XT, and XS, respectively. Then, these clean reads were arranged into 41571, 45477, 41900, and 44065 unigenes for CT, CS, XT, and XS, respectively, with a mean length of 829 bp and N50 length of 1694 bp, using Trinity software (Table 1). The Q30 and GC content of each library were over 93.57% and 46.58%, respectively. Of the unigenes predicted, 24008 (39.96%) had a length between 200 and 300 bp, and 13785 (22.94%) were over 1000 bp in length (Supplementary Figure 1).

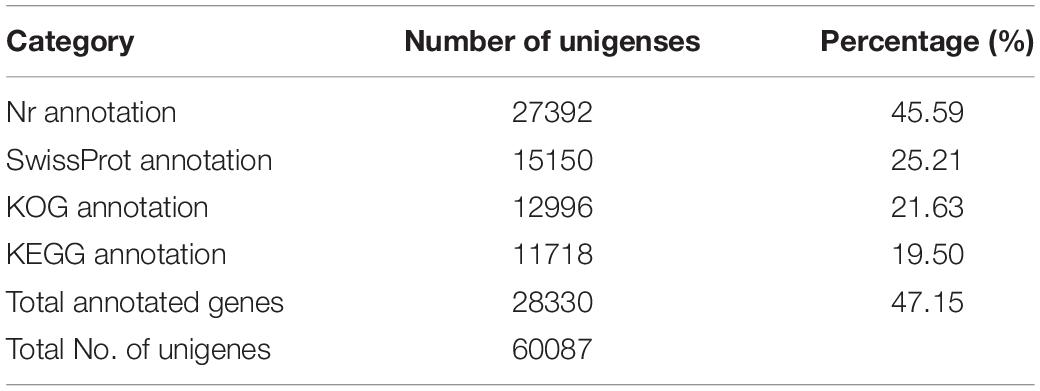

In total, 28330 unigenes (47.15%) were annotated (Table 2). A total of 27392 unigenes (45.59%) were annotated in the NR database, which accounted for the largest proportion of matches, followed by the Swiss-Prot (15150, 25.21%), KOG (12996, 21.63%), and KEGG (11718, 19.50%) databases. The identity levels of the annotation match were >80.00% for 17.87% of the sequences and between 60.00 and 80.00% for 29.04% of the sequences (Figure 1A). According to the NR annotation, 61.64% of the unigenes were annotated with sequences from Amyelois transitella (18.02%), B. mori (9.57%), Papilio xuthus (7.78%), Papilio machaon (6.62%), Operophtera brumata (4.15%), Plutella xylostella (3.66%), Papilio polytes (3.27%), Danaus plexippus (2.33%), Pararge aegeria (2.31%), Daphnia magna (2.11%), and Chilo suppressalis (1.64%), and 38.54% of the unigenes were annotated with sequences from other species (Figure 1B). Based on the E value distribution of the top hits in the NR database, 33.40% and 40.31% of the sequences showed strong (0 ≤ E-value ≤ 1.0E–100) and moderate (1.0E–100 ≤ E-value ≤ 1.0E–20) homology, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. NR classification data. (A) The identity distribution of the NR annotation results. (B) The species distribution of the NR annotation results. (C) The E-value distribution of the NR annotation results. NR, non-redundant protein database.

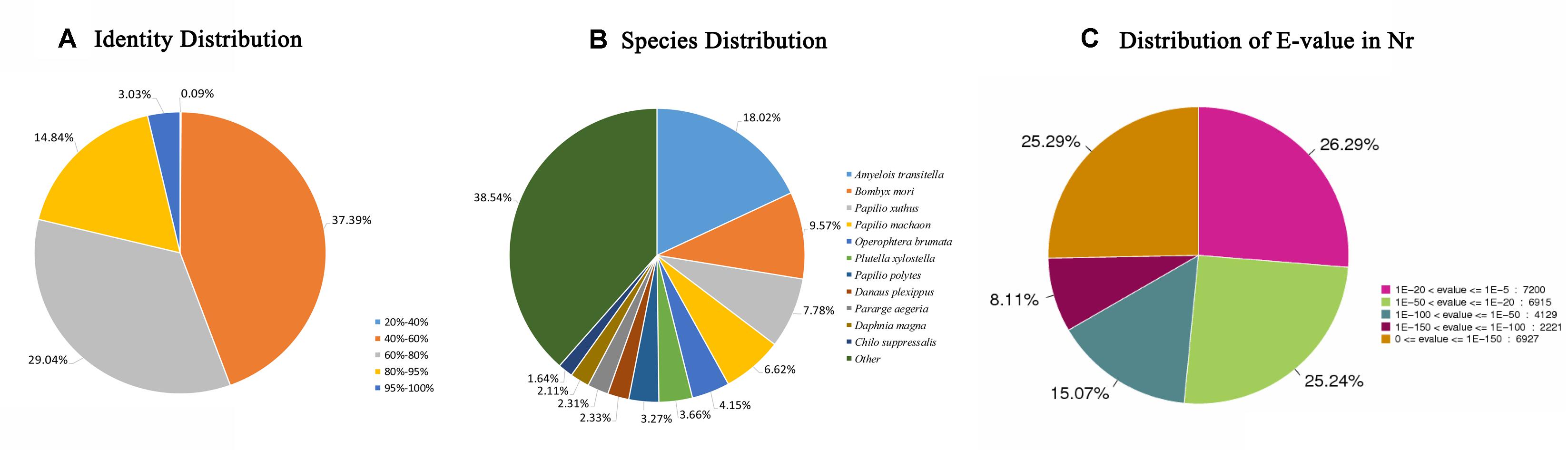

A total of 4662 unigenes were annotated with functional groups classified into 52 subcategories under three main GO categories (“biological process,” “cellular component,” and “molecular function”) via Blast2GO and WEGO software (Figure 2). Among 24 subcategories in the “biological process” category, “metabolic process” and “cellular process” were predominant terms. In the “cellular component” category, “cell part” and “cell” were the most abundant GO terms. Of the 11 subcategories under the “molecular function” category, two contained the largest groups, namely, “catalytic activity” and “binding.”

Figure 2. Histogram of Gene Ontology classification of C. sacchariphagus unigenes. The right y-axis represents the number of genes in each category. The left y-axis represents the percentage of a specific category of genes in that main category.

Identification of the Candidate Genes Related to Chemoreception

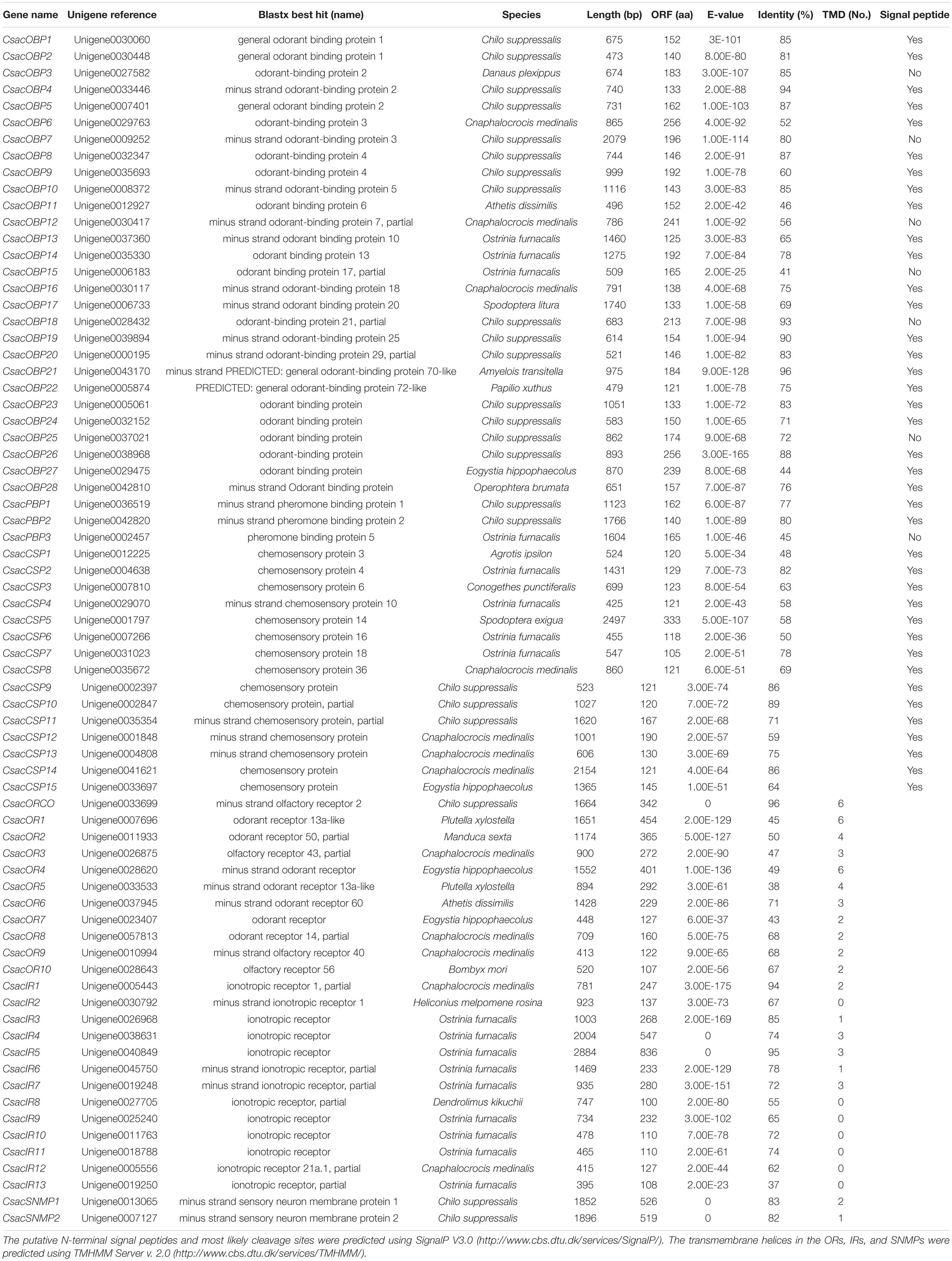

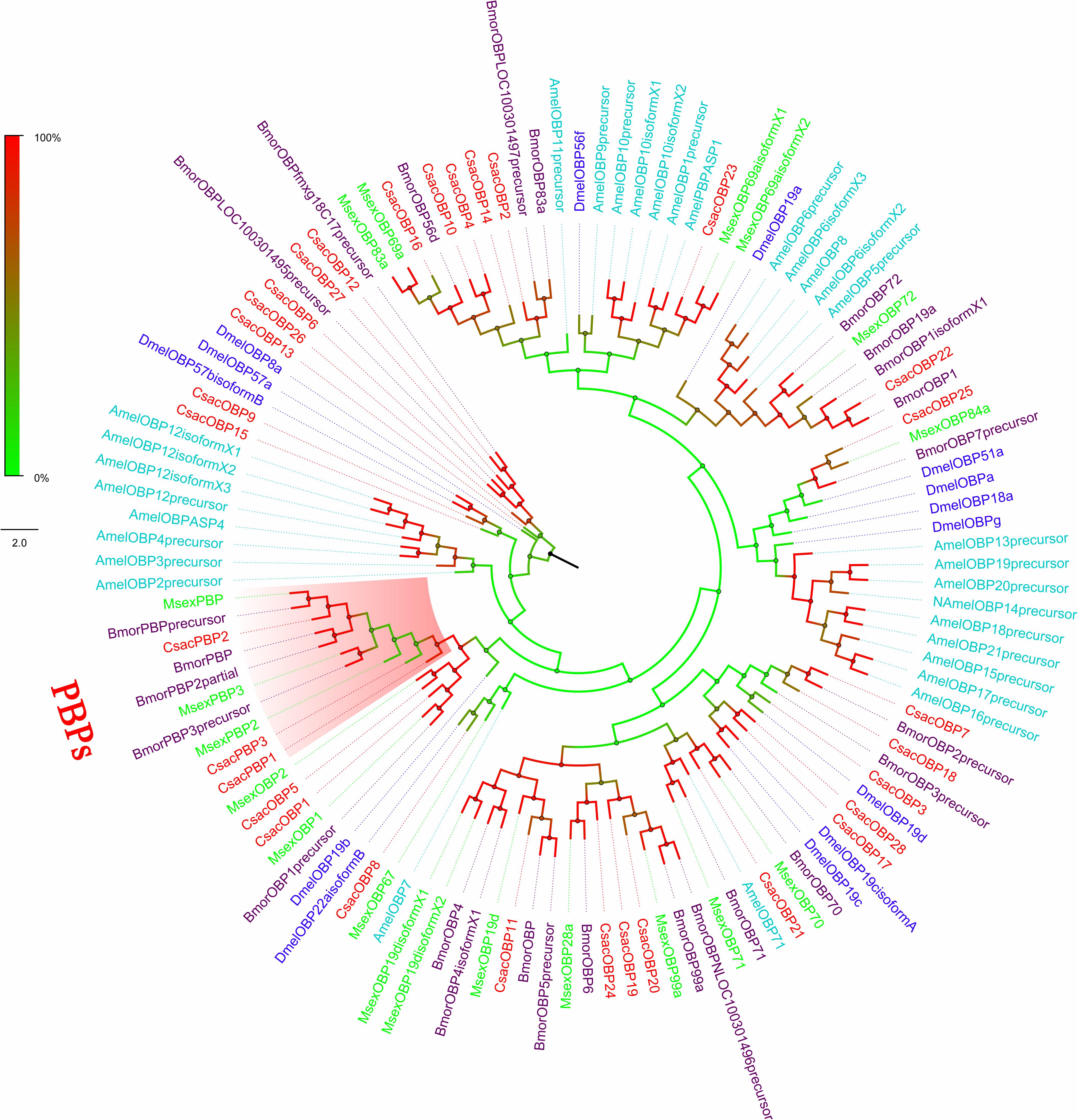

Within this transcriptome, 72 candidate genes related to chemoreception were identified, including 11 ORs, 31 OBPs/PBPs, 13 IRs, 15 CSPs, and two SNMPs. Twenty-eight different putative sequences encoding odourant binding proteins were identified. Most insect OBPs/PBPs were highly conserved, and 15 candidate OBPs/PBPs (CsacOBP1, CsacOBP2, CsacOBP3, CsacOBP4, CsacOBP5, CsacOBP7, CsacOBP8, CsacOBP10, CsacOBP18, CsacOBP19, CsacOBP20, CsacOBP21, CsacOBP23, CsacOBP26, and CsacPBP2) had an identity higher than 80% with OBPs/PBPs from Chilo suppressalis, Danaus plexippus, and Amyelois transitella (Table 3). According to the prediction, all the CsacOBPs/PBPs possess signal peptides with complete N-termini, except for CsacOBP3, CsacOBP7, CsacOBP12, CsacOBP15, CsacOBP18, CsacOBP25, and CsacPBP3. In the phylogenetic analysis of the OBPs/PBPs in different insect species, CsacOBPs/PBPs were spread across various branches, where they formed five small subgroups together with OBPs/PBPs from other insects (Figure 3). A specific branch consisting of five OBPs from C. sacchariphagus (CsacOBP2, CsacOBP4, CsacOBP10, CsacOBP14, and CsacOBP16) was divergent from the OBPs of other insects. The five CsacOBPs have a close relation to OBP83a, OBP56d, and OBPLOC100301497 precursor from B. mori and OBP83a and OBP69a from M. sexta. CsacOBP6, CsacOBP12, CsacOBP26, and CsacOBP27 formed a small branch that shared a close relationship to OBPfmxg18C7 precursor and OBPLOC100301495 precursor from B. mori; in addition, three OBPs from C. sacchariphagus (CsacOBP19, CsacOBP20, and CsacOBP24), two OBPs from M. sexta (MsexOBP99a and MsexOBP28a) and three OBPs from B. mori (BmorOBPLOC100301496 precursor, BmorOBP99a, and BmorOBP6) formed a small subgroup within this branch. However, a specific branch consisting of five closely related genes, CsacPBP2, MsexPBP, BmorPBP precursor, BmorPBP, and BmorPBP2 partial, was divergent from other OBPs/PBPs.

Table 3. Unigenes of candidate odorant receptors, ionotropic receptors, odorant binding proteins, sensory neuron membrane proteins, and chemosensory proteins.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic analysis of putative odourant/phenomenon binding proteins (OBP/PBPs) of C. sacchariphagus. The tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method. Genes from C. sacchariphagus are labeled in red. OBP/PBPs from D. melanogaster (Diptera) are labeled in dark blue, OBP/PBPs from B. mori (Lepidoptera) are labeled in purple, OBP/PBPs from M. sexta (Lepidoptera) are labeled in green, and OBP/PBPs from A. mellifera (Hymenoptera) are labeled in light blue.

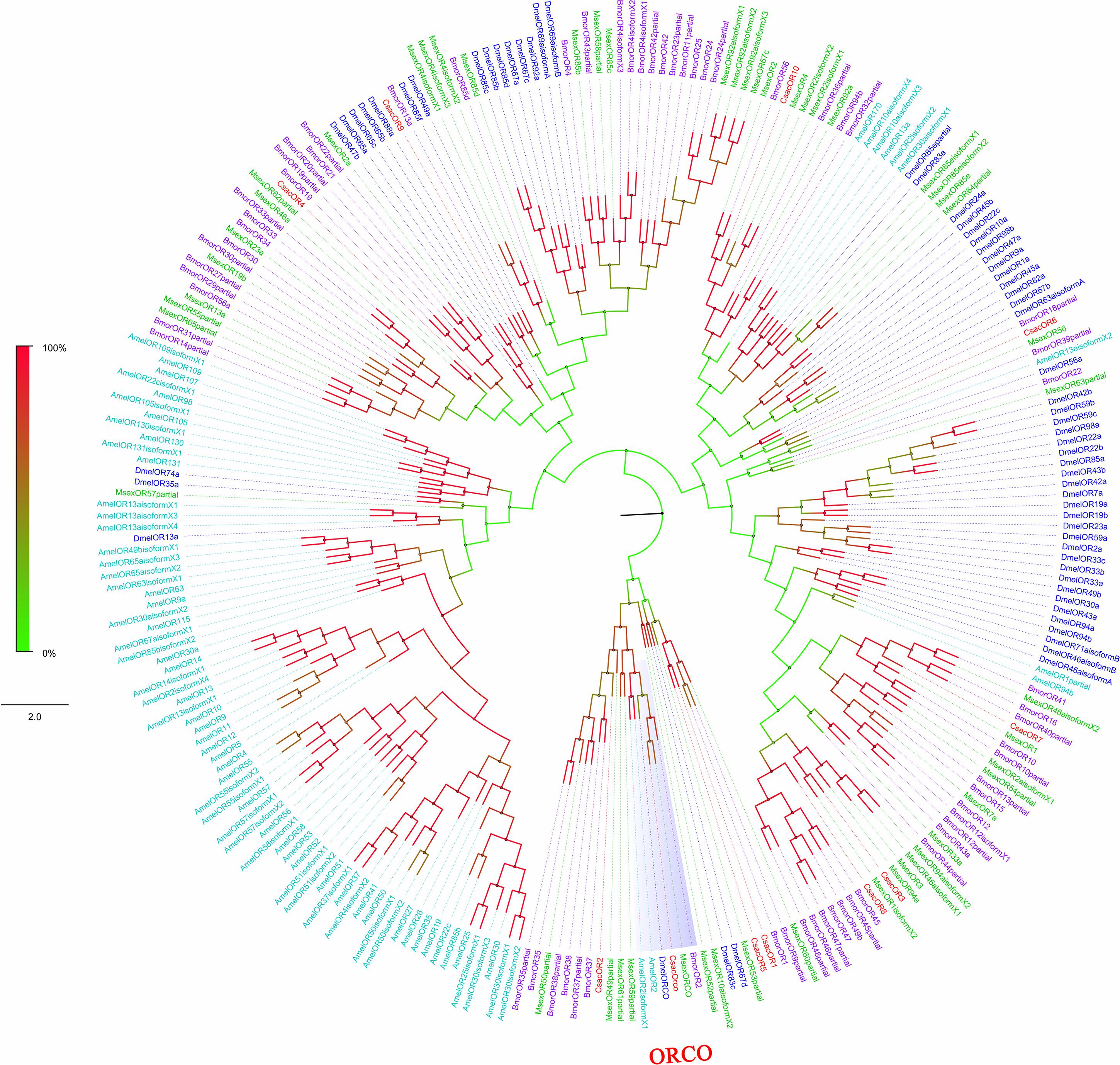

Among the 11 candidate ORs, four were of short length (no more than 100 amino acids), and the remaining seven possessed a deduced protein longer than 200 amino acids (Table 3). From the prediction, three sequences (CsacORCO, CsacOR1, and CsacOR4) were full-length OR genes with intact open reading frames with a general length of 1500 bp and 5–7 transmembrane domains, which are characteristic of typical insect ORs. Compared with OBPs, the results of BLASTx revealed that the identity of these candidate ORs with known insect ORs was relatively low. Only one candidate OR (CsacORCO) had an identity higher than 80% (96%) with its closest match, while the identities of the remaining ORs ranged from 38 to 71%. Two ORs, CsacOR1 and CsacOR5, formed a small branch that was closely related to BmorOR1 and BmorOR9 from B. mori and MsexOR60 from M. sexta, and these ORs formed a distinct subgroup (Figure 4). Most of the splits in the tree were supported by bootstrap values, and only a few splits were unreliable.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic analysis of putative olfactory receptors (ORs) of C. sacchariphagus. The tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method. Genes from C. sacchariphagus are labeled in red. ORs from D. melanogaster (Diptera) are labeled in dark blue, ORs from B. mori (Lepidoptera) are labeled in purple, ORs from M. sexta (Lepidoptera) are labeled in green, and ORs from A. mellifera (Hymenoptera) are labeled in light blue.

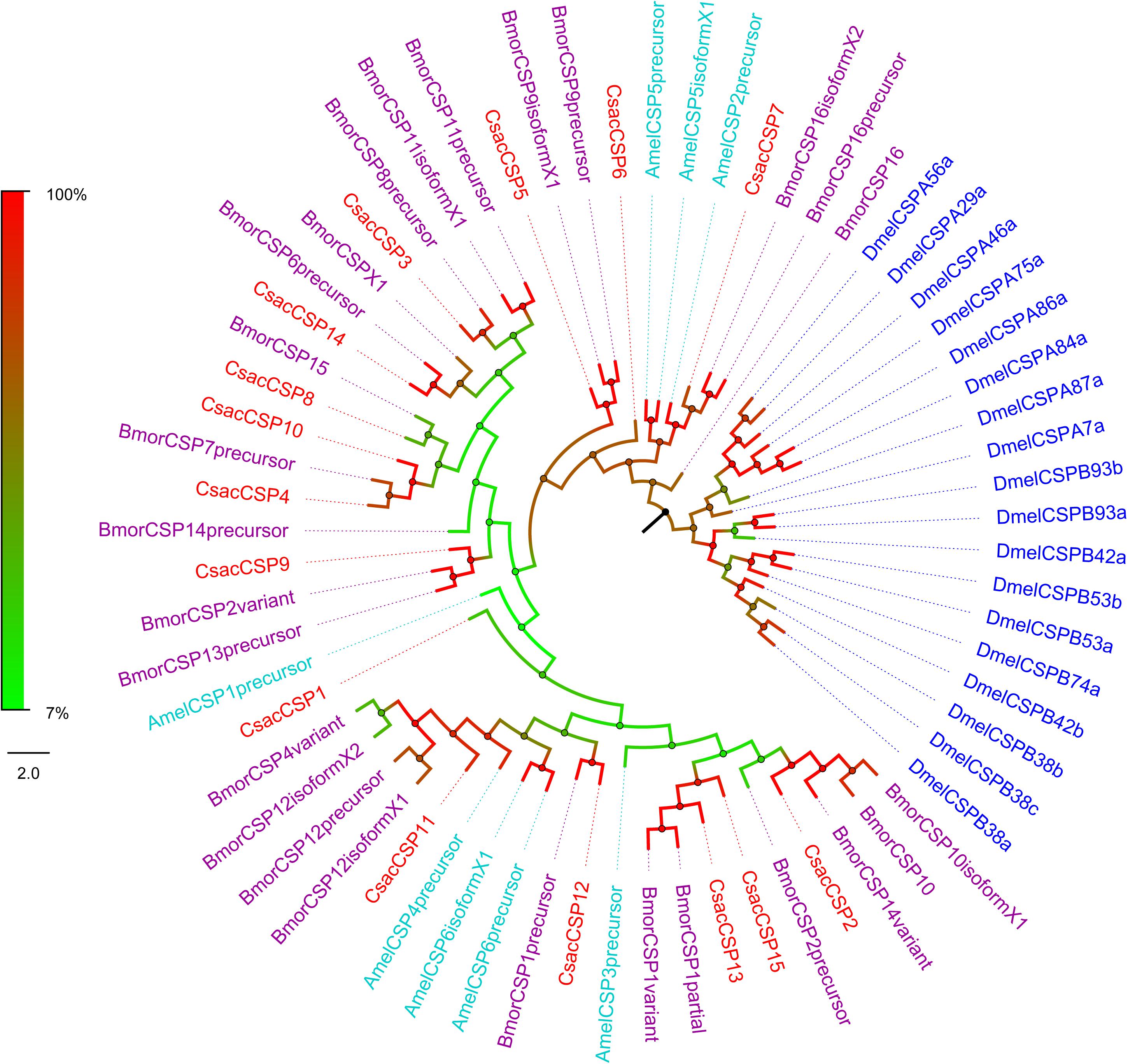

Bioinformatic analysis led to the identification of 15 different sequences encoding candidate CsacCSPs. Due to their complete N-termini, all the sequences had signal peptides. The identity of the 15 CsacCSPs ranged from 48 to 89% (Table 3). Neighbor-joining tree analysis showed that CsacCSP13 and CsacCSP15 formed a specific branch that was close to BmorCSP1 and BmorCSP1 variant from B. mori. Additionally, a specific branch consisting of two CSPs from C. sacchariphagus (CsacCSP4 and CsacCSP10) was divergent from the CSPs of other insects, and the two CsacCSPs have a close relationship to CSP7 precursor from B. mori (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Phylogenetic analysis of putative chemosensory proteins (CSPs) of C. sacchariphagus. The tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method. Genes from C. sacchariphagus are labeled in red. CSPs from D. melanogaster (Diptera) are labeled in dark blue, CSPs from B. mori (Lepidoptera) are labeled in purple, CSPs from M. sexta (Lepidoptera) are labeled in green, and CSPs from A. mellifera (Hymenoptera) are labeled in light blue.

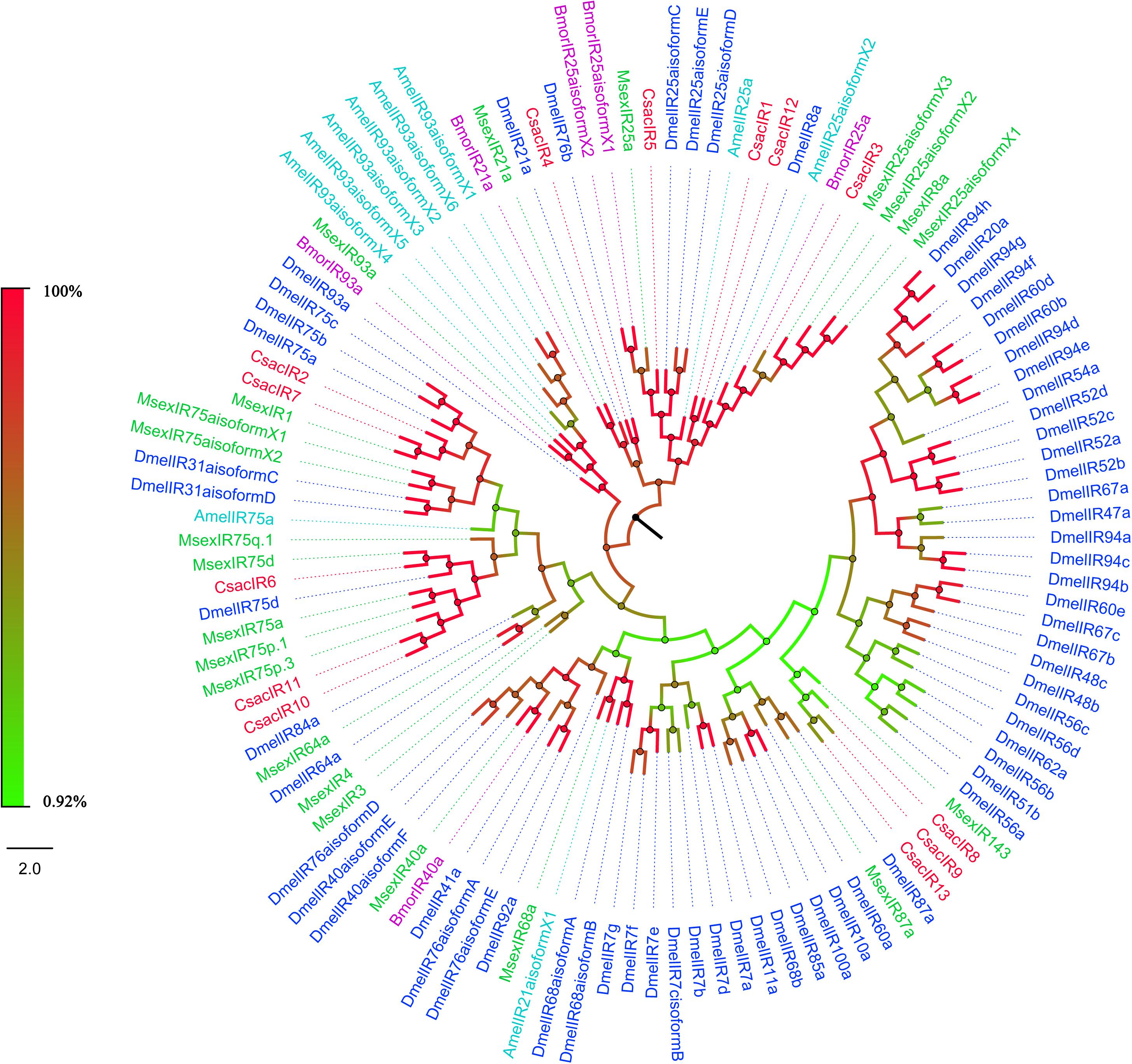

The putative IR genes in the C. sacchariphagus transcriptome were represented according to their similarity to known insect IRs. Bioinformatic analysis led to the identification of 13 candidate IRs, of which eight candidate IRs had higher than 70% identity with known insect IRs, and only two had identities lower than 60%. Compared with general insect IRs, which have three transmembrane domains, three IR candidates in C. sacchariphagus (CsacIR4, CsacIR5, and CsacIR7) were predicted to have three transmembrane domains by TMHMM2.0 (Table 3). In the phylogenetic analysis, CsacIR2, CsacIR7, and IRs from M. sexta (MsexIR1) and D. melanogaster (DmelIR75a, DmelIR75b, and DmelIR75c) formed a distinct subgroup, while CsacIR6, CsacIR10, and CsacIR11 formed a branch that shared a close relation to IR75d from D. melanogaster and IR75a, IR75p.1, and IR75p.3 from M. sexta; additionally, CsacIR1, CsacIR3, and CsacIR12 formed a specific branch consisting of DmelIR8a, AmelIR25a MsexIR8a, MsexIR25a, and BmorIR25a with their positions in phylogenetic tree and strong bootstrap support (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Phylogenetic analysis of putative ionotropic receptors (IRs) of C. sacchariphagus. The tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method. Genes from C. sacchariphagus are labeled in red. IRs from D. melanogaster (Diptera) are labeled in dark blue, IRs from B. mori (Lepidoptera) are labeled in purple, IRs from M. sexta (Lepidoptera) are labeled in green, and IRs from A. mellifera (Hymenoptera) are labeled in light blue.

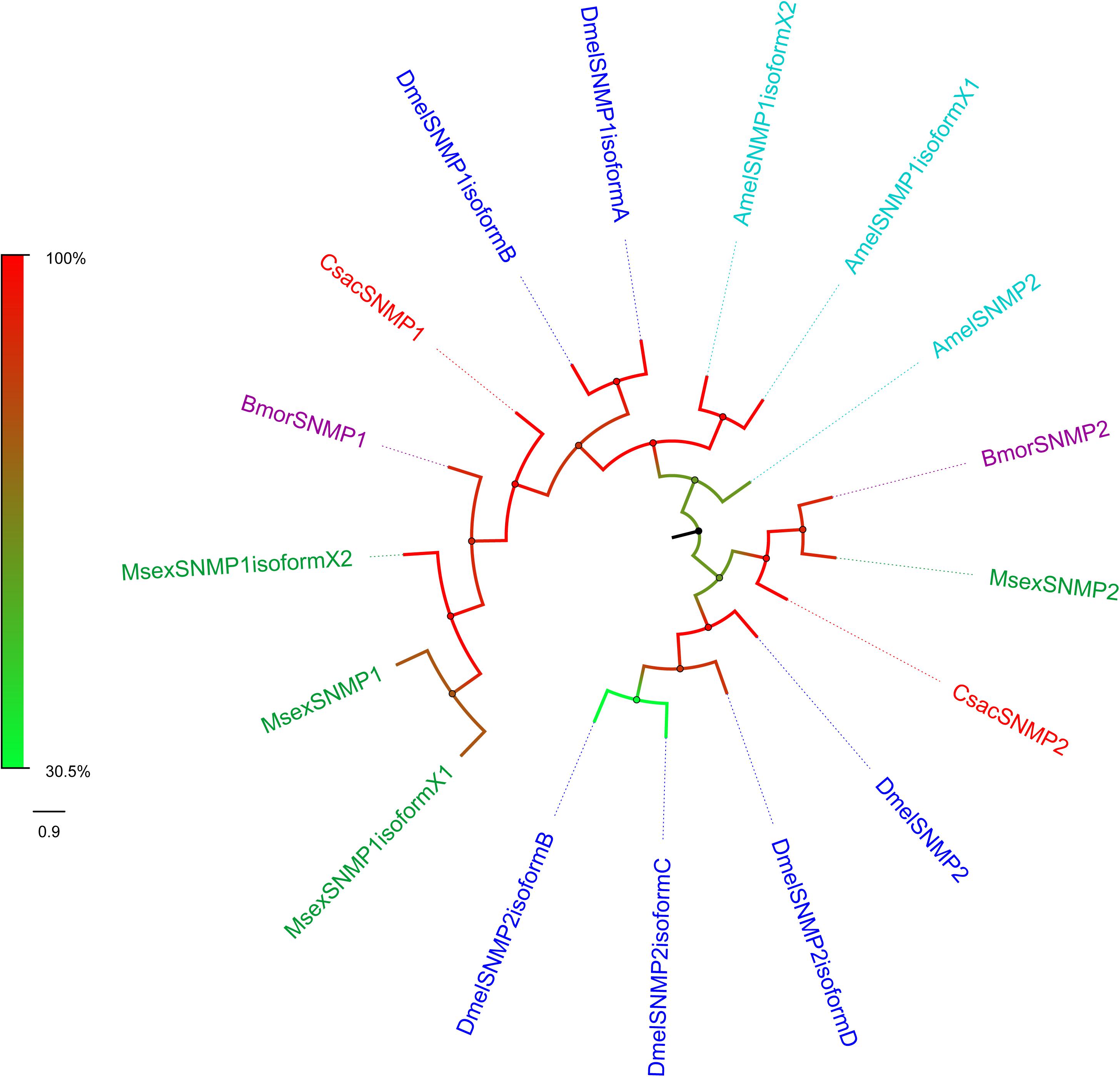

Sensory neuron membrane proteins were identified in pheromone-sensitive neurons in Lepidopteran insects and are thought to function in the process of pheromone recognition (Rogers et al., 2001). Two SNMPs (CsacSNMP1 and CsacSNMP2) were identified in our transcriptome. Both of them all have an identity of greater than 80% with SNMPs of Chilo suppressalis (Table 3). According to the phylogenetic analysis, both C. sacchariphagus candidate SNMPs clustered with their SNMP orthologs into separate subclades (Figure 7), among which CsacSNMP1, BmorSNMP1, and MsexSNMP1 formed a specific branch and CsacSNMP2 and SNMP2 from B. mori and M. sexta shared a close relationship.

Figure 7. Phylogenetic analysis of putative sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) of C. sacchariphagus. The tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method. Genes from C. sacchariphagus are labeled in red. SNMPs from D. melanogaster (Diptera) are labeled in dark blue, SNMPs from B. mori (Lepidoptera) are labeled in purple, SNMPs from M. sexta (Lepidoptera) are labeled in green, and SNMPs from A. mellifera (Hymenoptera) are labeled in light blue.

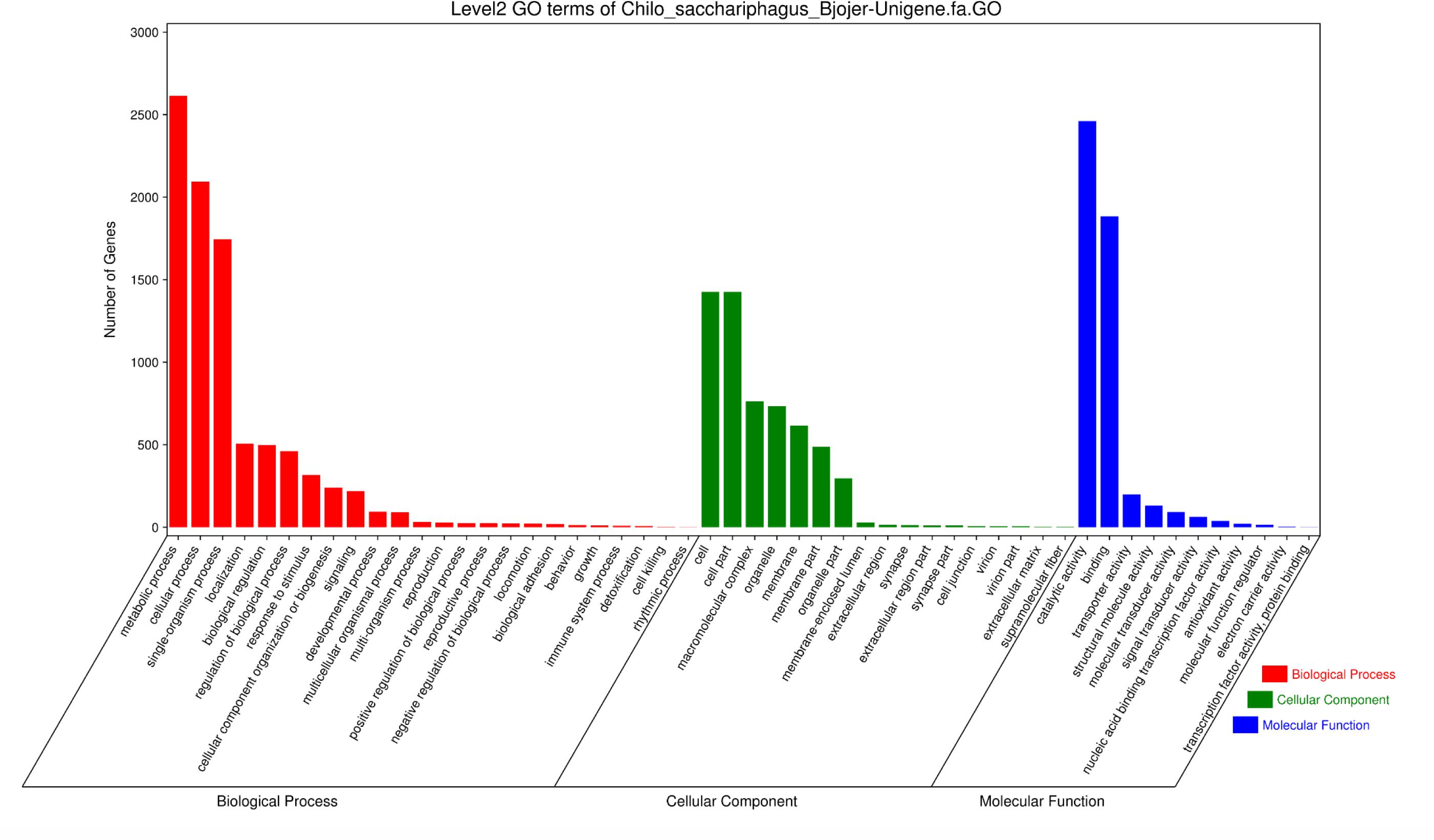

Tissue- and Sex-Specific Expression of Candidate Chemosensory Genes

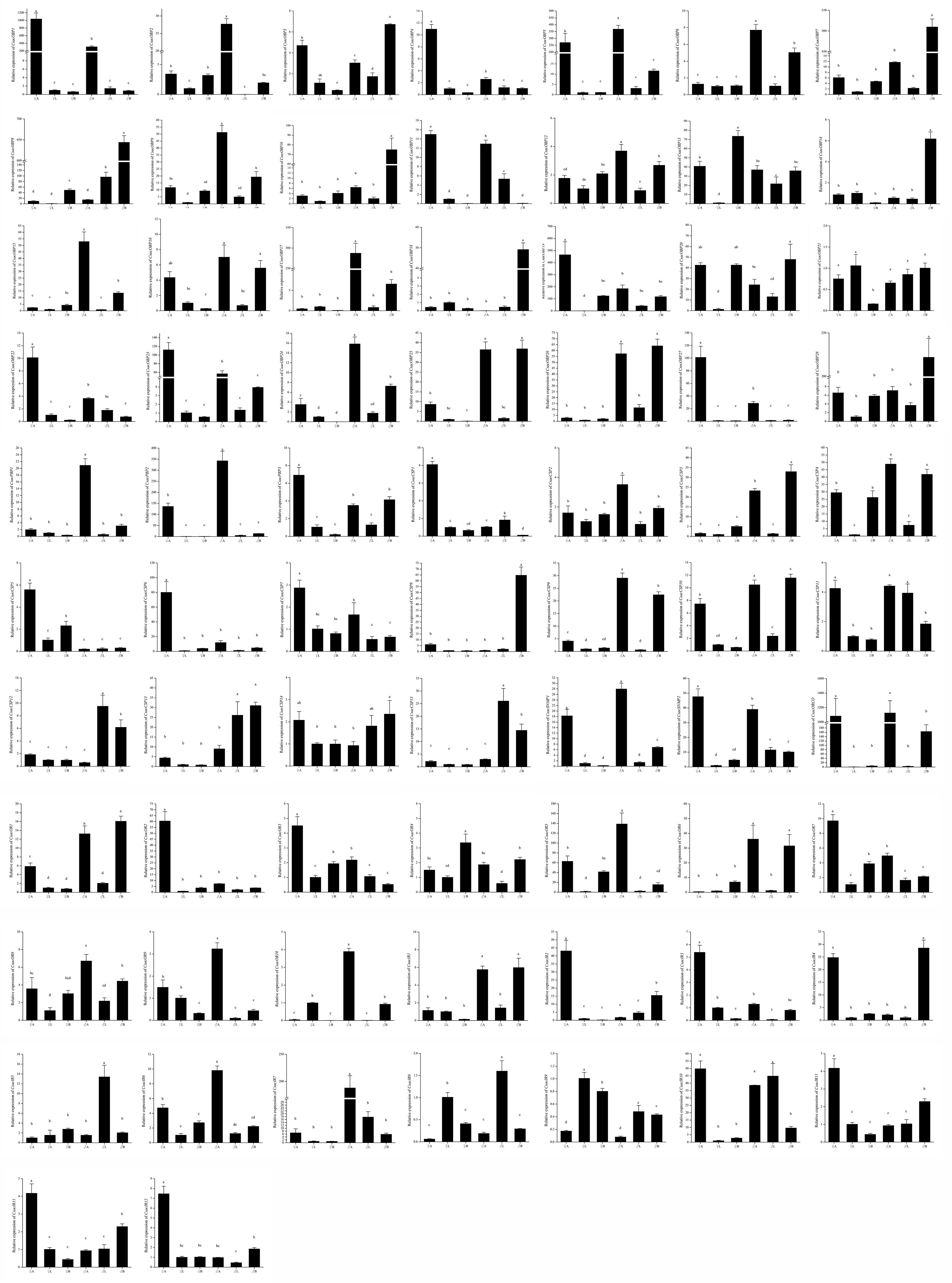

To validate and analyze the expression profiles of candidate chemosensory genes in different organs and tissues between male and female C. sacchariphagus, all candidate chemosensory genes encoding OBPs/PBPs, CSPs, ORs, IRs, and SNMPs were subjected to RT-qPCR with specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). The expression difference of chemosensory genes from transcriptome data was shown in heatmap (Supplementary Figure 2). The expression patterns of the 72 chemosensory genes were basically consistent with the FPKM values, and the data are presented as log2 values of fold changes in gene expression. According to the RT-qPCR results, a large number of chemosensory genes were antenna-predominant and showed different expression levels between males and females (P < 0.05). Among these genes, the expression levels of genes (CsacOBP2/5/6/9/12/15/17/24/25/26, CsacPBP1/2, CSP2/3/4/9/10, CsacOR1/5/6/8/9/10, IR1/6/7, and CsacSNMP1) were higher in male antennae than that in female antennae (Figure 8), whereas the opposite occurred was observed for the other genes expression (CsacOBP1/3/4/11/19/22/23/27, CsacPBP3, CsacCSP1/5/6/7, CsacOR2/3/7, CsacIR2/3/4/11/12, and CsacSNMP2) (Figure 8). In addition, some genes (CsacOBP3/7/8/10/13/14/18/20/25/26/28, CsacCSP3/4/8/9/10/11/12/13/15, CsacOR1/4/6, and CsacIR1/4/8/9/10) had a high expression in bodies (excluding antennae and legs) or legs (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Expression patterns of putative odourant/phenomenon binding proteins (OBP/PBPs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs), odourant receptors (ORs), and ionotropic receptors (IRs) in the different tissues of C. sacchariphagus as determined using RT-qPCR. ♀A, female antennae; ♂A, male antennae; ♀L, female legs; ♂L, male legs; ♀B, female body (without antennae and legs); ♂B, male body (without antennae and legs). Error bars indicate SEMs from the analysis of three replicates (P < 0.05). The lower case letters indicate that there are significant differences between the data.

Discussion

In this study, the transcriptome of the pest C. sacchariphagus was analyzed using Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 technology. We obtained 16.60 GB of clean data that was assembled into 60084 unigenes with a mean length of 829 bp and N50 length of 1694 bp. There were 60.67% unigenes with a length <500 bp after assembly, possibly due to the short-length sequencing capacity of Illumina sequencing. Among the 60084 unigenes, 28330 unigenes were annotated, and 52.85% of unigenes had no significant match in any of the databases searched. This phenomenon may be caused by the lack of genomic and transcriptomic information for this moth in the databases. This antennal and body transcriptome sequencing provides a dataset of chemosensory genes, including 28 OBPs, three PBPs, 15 CSPs, 11 ORs, 13 IRs, and two SNMPs.

Odourant/pheromone binding proteins interact with semiochemicals, hormones or other biologically active chemicals that enter the body through pores and then transport them to ORs located on the membranes of olfactory receptor neurons (Pelosi and Maida, 1995; Vogt, 1995; Kaissling, 1998). Fewer OBPs/PBPs were identified in this transcriptome of C. sacchariphagus (31) than in B. mori (44) or D. melanogaster (51) (Hekmat-Scafe et al., 2002; Gong et al., 2007). The difference in the number of OBPs might be related to the sequencing method, depth, the process of sample preparation or evolutionary differences across different species. These results are comparable to those reported for the transcriptomes of Spodoptera littoralis (33), Spodoptera exigua (34), and Helicoverpa armigera (26) (Liu N. Y. et al., 2012; Liu Y. et al., 2012; Poivet et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2019). This suggests that C. sacchariphagus OBPs show conservation in gene numbers. Some OBPs are conserved and have orthologous relationships with counterparts from other insects. Insect OBPs/PBPs, mainly expressed in the antennae, are considered to have an olfactory function. Analysis of OBP/PBPs expression profiles in different organs and tissues could reveal their likely functions. qRT-PCR results showed that 22 CsacOBPs/PBPs displayed antenna-enriched expression, indicating that these genes may play critical roles in the process of olfactory reception. Among these genes, 13 (CsacOBP2/5/6/9/12/15/17/24/25/26/27 and CsacPBP1/2) were mainly expressed in male antennae, suggesting that these genes may encode proteins involved in sex-specific behaviors, including selectively sensing and transporting sex pheromones released by females in the process of molecular recognition and searching for suitable mates (Gu et al., 2013; Jin et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016, 2019). Ten genes (CsacOBP7/8/10/13/14/16/18/20/21/28) without significant differences in expression levels between males and females may function as general odourant detectors rather than in pheromone recognition (Li et al., 2008; Pelletier and Leal, 2009; He et al., 2019a). Some genes (CsacOBP1/3/4/11/19/22/23/27) showed female antenna-biased expression, indicating that those OBPs may help to locate oviposition sites by recognizing chemicals from hosts, a model that is supported by previous studies of Pieris rapae (Renwick et al., 1992; Sato et al., 1999; Li et al., 2020).

Fifteen CSPs were identified in transcriptome sequencing. This number is almost equal to the number of CSPs in H. armigera (18), Heliothis assulta (17), S. littoralis (21), B. mori (20), and S. exigua (20) but much higher than that of D. melanogaster (4) (Wanner et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2010; Poivet et al., 2013; Leitch et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2019), indicating that the numbers of CSP genes differ among different species. CSPs exist in insect chemosensory and non-chemosensory organs and tissues, including antennae, legs, pheromone glands, and wings (Picimbon et al., 2001; Ban et al., 2003; Dani et al., 2011; Liu N. Y. et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2017). In our study, 10 CsacCSPs were significantly expressed in the antennae, and these CSPs might be thought to participate in general odourant recognition and perception (Pelosi et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2018). Four CSPs showed high expression in legs and might be associated with gustatory behaviors, such as detecting non-volatile chemicals (Jia et al., 2020).

In the qRT-PCR analysis, some identified CsacOBPs and CsacCSPs displayed high expression in male bodies, and we speculated that these genes are likely to be involved in different functions in non-sensory organs and tissues of the insect body. Some OBPs and CSPs in male insect seminal fluid might be related to binding and releasing pheromones. In D. melanogaster, OBPs were found to be components of the seminal fluid (Takemori and Yamamoto, 2009); LmigCSP91 was identified to have a high expression in reproductive organs in male Locusta migratoria and possessed a good affinity to a kind of pheromone that is produced in the same reproductive organs (Ban et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2013). Some OBPs are male specific and could be transferred into female bodies during the process of mating, indicating that these OBPs might function in sperm–egg communication (Findlay et al., 2008; Takemori and Yamamoto, 2009; Prokupek et al., 2010). In addition, CSPs are involved in releasing some molecules in male glands; for example, a CSP was found in large quantities in the ejaculatory apparatus, which secretes the male pheromone vaccenyl acetate (Dyanov and Dzitoeva, 1995).

Odourant receptors act as the most critical and determinate roles in insect peripheral olfactory reception (Dani et al., 2011; Leal, 2013). Eleven ORs were identified in our research, and this number was lower than the numbers identified in B. mori (72) (Gong et al., 2009), M. sexta (73) (Koenig et al., 2015), H. armigera (84) (Pearce et al., 2017), Heliconius melpomene (74) (Dasmahapatra et al., 2012), D. melanogaster (62) (Clyne et al., 1999; Gao and Chess, 1999; Robertson et al., 2003), Laodelphax striatellus (133) (He et al., 2020), Sogatella furcifera (135) (He et al., 2018), and A. mellifera (170) (Robertson and Wanner, 2006), suggesting that different sequencing methods and depths may affect the outcome of studies; the lack of genomic and transcriptomic information in the databases may influence the annotation results for C. sacchariphagus, and some ORs expressed at low levels may be difficult to detect (Li et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). In the neighbor-joining tree of ORs, CsacOR1 and CsacOR5 are orthologs of BmorOR1; CsacOR4 is the ortholog of BmorOR19; and CsacOR10 clustered close to BmorOR56. In B. mori, OR1 is the receptor of the pheromone bombykol; OR19 can sense linalool, which is related to selection of spawning environment; and OR56, specific and highly sensitive to cis-jasmone, is involved in the sensing of odor molecules released by plants and signal transduction (Wanner et al., 2007; Anderson et al., 2009; Tanaka et al., 2009). The qRT-PCR results showed that CsacOR1/5/10 were highly expressed in the male antennae, suggesting that they are highly specifically involved in the detection of sex pheromones, while CsacOR4 has a higher expression in the female body than in the male body, indicating that it is likely involved in the regulation of female-specific behaviors, such as the localization of oviposition sites and oviposition (Xu et al., 2020). The expression of CsacORCO, which was highly conserved in the OR tree, was significantly antenna-specific. The different expression levels of the ORs in different organs and tissues and different sexes suggested that they might perform different functions, which should be further studied in the future.

Thirteen IR genes were identified in this study from C. sacchariphagus. The number is similar to that of B. mori (18), H. armigera (12), and S. littoralis (12) (Croset et al., 2010; Olivier et al., 2011; Liu Y. et al., 2012). Most CsacIRs were clustered with orthologs in D. melanogaster, M. sexta, B. mori, and A. mellifera, indicating that IRs are relatively conserved in different insect species. In D. melanogaster, IR84a/8a, IR76b/IR41a, IR75a/IR8a, IR64a/IR8a have been reported to sense phenylacetaldehyde and phenylacetic acid, polyamines, acetic acid, and other acids, respectively (Ai et al., 2010; Grosjean et al., 2011; Hussain et al., 2016; Prieto-Godino et al., 2016). And in M. sexta, MsexIR8a has been shown the function of sensing carboxylic acids 3-methylpentanoic acid and hexanoic acid (Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, DmelIR21a/IR25a have been reported to be sensitive to cool temperatures (Ni et al., 2016). The CsacIR genes showed high sequence similarity to these functionally characterized DmelIRs, indicating that they may have similar functions.

In insects, SNMP1 is usually expressed in pheromone-sensitive OSNs and is important for pheromone perception (Jin et al., 2008; Nichols and Vogt, 2008; Vogt et al., 2009; Gomez-Diaz et al., 2016). However, SNMP2 functions remain unclear. In the present study, two SNMPs were identified in C. sacchariphagus. Both were conserved with respect to other holometabolous insect species. They exhibited a clear antenna-predominant expression, suggesting that CsacSNMP1 may be associated with pheromone reception.

In conclusion, 72 candidate chemosensory protein genes (31 OBP/PBPs, 15 CSPs, 11 ORs, 13 IRs, and two SNMPs) were first identified via transcriptome sequencing analysis in C. sacchariphagus, which is an important agricultural pest. This study will not only serve as a valuable resource for future research on the chemosensory system of C. sacchariphagus and other lepidopteran species but also contribute to the development of creative and sustainable pest management strategies involving interference with olfaction.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

JL, HL, JY, YA, and HW conceived, coordinated, and designed the research. YM, JL, and DS assembled and analyzed the transcriptome datasets. JL and HL performed experiments. JL, JY, YA, and HW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the GDAS’ Project of Science and Technology Development (Grant No. 2019GDASYL-0103040) and GDAS’ Project of Science and Technology Development (Grant No. 2020GDASYL-20200103056). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank M.D. students Anwen Liang (State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, Sun Yat-sen University) for technical assistance. Thanks to Prof. Qiang Zhou (State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, Sun Yat-sen University) for editorial assistance and comments on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.636353/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Length distribution of unigenes in transcriptomes of Chilo sacchariphagus.

Supplementary Figure 2 | The expression difference of chemosensory genes from transcriptome data.

Supplementary Table 1 | Primers used in qRT-PCR.

Abbreviations

OR, odorant receptor; IR, ionotropic receptor; PBP, pheromone binding protein; OBP, odorant binding protein; CSP, chemosensory protein; SNMP, sensory neuron membrane protein; GO, gene ontology; FPKM, fragments per kb per million fragments; FDR, false discovery rate.

References

Abuin, L., Bargeton, B., Ulbrich, M. H., Isacoff, E. Y., Kellenberger, S., and Benton, A. R. (2011). Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 69, 44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.042

Ai, M., Min, S., Grosjean, Y., Leblanc, C., Bell, R., Benton, R., et al. (2010). Acid sensing by the Drosophila olfactory system. Nature 468, 691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature09537

Anderson, A. R., Wanner, K. W., Trowell, S. C., Warr, C. G., Jaquin-Joly, E., Zagatti, P., et al. (2009). Molecular basis of female-specific odorant responses in Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.11.002

Andersson, M. N., Grossewilde, E., Keeling, C. I., Bengtsson, J. M., Yuen, M. M., Li, M., et al. (2013). Antennal transcriptome analysis of the chemosensory gene families in the tree killing bark beetles, Ips typographus and Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). BMC Genomics 14:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-198

Ban, L., Scaloni, A., Brandazza, A., Angeli, S., Zhang, L., Yan, Y., et al. (2003). Chemosensory proteins of Locusta migratoria. Insect Mol. Biol. 12, 125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00394.x

Ban, L. P., Napolitano, E., Serra, A., Zhou, X., Iovinella, I., and Pelosi, P. (2013). Identification of pheromone-like compounds in male reproductive organs of the oriental locust Locusta migratoria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 437, 620–624. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.015

Bengtsson, J. M., Trona, F., Montagné, N., Anfora, G., Ignell, R., Witzgall, P., et al. (2012). Putative chemosensory receptors of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella, identified by antennal transcriptome analysis. PLoS One 7:e31620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031620

Benton, R., Sachse, S., Michnick, S. W., and Vosshall, L. B. (2006). A typical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors in vivo. PLoS Biol. 4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040020

Benton, R., Vannice, K. S., Gomez-Diaz, C., and Vosshall, L. B. (2009). Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell 136, 149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001

Bezuidenhout, C. N., Goebel, R., Hull, P. J., Schulze, R. E., and Maharaj, M. (2008). Assessing the potential threat of Chilo sacchariphagus (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) as a pest in South Africa and Swaziland: realistic scenarios based on climatic indices. Afr. Entomol. 16, 86–90. doi: 10.4001/1021-3589-16.1.86

Butterwick, J. A., Del Mármol, J., Kim, K. H., Kahlson, M. A., Rogow, J. A., Walz, T., et al. (2018). Cryo-EM structure of the insect olfactory receptor Orco. Nature 560, 447–452. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0420-8

Chang, H., Liu, Y., Yang, T., Pelosi, P., Dong, S., and Wang, G. (2015). Pheromone binding proteins enhance the sensitivity of olfactory receptors to sex pheromones in Chilo suppressalis. Sci. Rep. 5:13093. doi: 10.1038/srep13093

Chen, H., Liu, J., Cui, K., Lu, Q., Wang, C., Wu, H., et al. (2018). Molecular mechanisms of tannin accumulation in Rhus galls and genes involved in plant-insect interactions. Sci. Rep. 8:9841. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28153-y

Chiu, J., DeSalle, R., Lam, H. M., Meisel, L., and Coruzzi, G. (1999). Molecular evolution of glutamate receptors: a primitive signaling mechanism that existed before plants and animals diverged. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 826–838. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026167

Clyne, P. J., Warr, C. G., Freeman, M. R., Lessing, D., Kim, J., and Carlson, J. R. (1999). A novel family of divergent seven-transmembrane proteins: candidate odorant receptors in Drosophila. Neuron 22, 327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81093-4

Croset, V., Rytz, R., Cummins, S. F., Budd, A., Brawand, D., and Kaessmann, H. (2010). Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064

Dani, F. R., Michelucci, E., Francese, S., Mastrobuoni, G., Cap-pellozza, S., Marca, G. L., et al. (2011). Odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in pheromone detection and release in the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Chem. Senses 36, 335–344. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq137

Dasmahapatra, K. K., Walters, J. R., Briscoe, A. D., Davey, J. W., Whibley, A., Nadeau, N. J., et al. (2012). Butterfly genome reveals promiscuous exchange of mimicry adaptations among species. Nature 487, 94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature11041

Dyanov, H. M., and Dzitoeva, S. G. (1995). Method for attachment of microscopic preparations on glass for in situ hybridization, PRINS and in situ PCR studies. Biotechniques 18, 822–826. doi: 10.1021/ic020451f

Eddy, S. R. (1998). Profile hidden markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755

Fandino, R. A., Haverkamp, A., Bisch-Knaden, S., Zhang, J., Bucks, S., Nguyen, T. A. T., et al. (2019). Mutagenesis of odorant coreceptor Orco fully disrupts foraging but not oviposition behaviors in the hawkmoth Manduca sexta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 15677–15685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902089116/-/DCSupplemental

Findlay, G. D., Yi, X., MacCoss, M. J., and Swanson, W. J. (2008). Proteomics reveals novel Drosophila seminal fluid proteins transferred at mating. PLoS Biol. 6:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060178

Gao, Q., and Chess, A. (1999). Identification of candidate Drosophila olfactory receptors from genomic DNA sequence. Genomics 60, 31–39. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5894

Geetha, N., Shekinah, E. D., and Rakkiyappan, P. (2010). Comparative impact of release frequency of, Trichogramma chilonis, Ishii against, Chilo sacchariphagus indicus, (Kapur) in sugarcane. J. Biol. Control 23, 343–351. doi: 10.18311/jbc/2009/3687

Gomez-Diaz, C., Bargeton, B., Abuin, L., Bukar, N., Reina, J. H., Bartoi, T., et al. (2016). A CD36 ectodomain mediates insect pheromone detection via a putative tunnelling mechanism. Nat. Commun. 7:11866. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11866

Gong, D. P., Zhang, H. J., Zhao, P., Lin, Y., and Xiang, Z. H. (2007). Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.11.012

Gong, D. P., Zhang, H. J., Zhao, P., Xia, Q. Y., and Xiang, Z. H. (2009). The odorant binding protein gene family from the genome of silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics 10:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-332

González, D., Zhao, Q., Mcmahan, C., Velasquez, D., Haskins, W. E., Sponsel, V., et al. (2009). The major antennal chemosensory protein of red imported fire ant workers. Insect Mol. Biol. 18, 395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00883.x

Grosjean, Y., Rytz, R., Farine, J. P., Abuin, L., Cortot, J., Jefferis, G. S., et al. (2011). An olfactory receptor for food-derived odours promotes male courtship in Drosophila. Nature 478, 236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10428

Grosse-Wilde, E., Kuebler, L. S., Bucks, S., Vogel, H., Wicher, D., and Hansson, B. S. (2011). Antennal transcriptome of Manduca sexta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7449–7454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017963108

Grosse-Wilde, E., Svatos, A., and Krieger, J. (2006). A pheromone-binding protein mediates the bombykol-induced activation of a pheromone receptor in vitro. Chem. Senses 31, 547–555. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjj059

Gu, S. H., Zhou, J. J., Wang, G. R., Zhang, Y. J., and Guo, Y. Y. (2013). Sex pheromone recognition and immunolocalization of three pheromone binding proteins in the black cutworm moth Agrotis ipsilon. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.12.009

Gu, X.-C., Zhang, Y.-N., Kang, K., Dong, S.-L., and Zhang, L.-W. (2015). Antennal transcriptome analysis of odorant reception genes in the red turpentine beetle (rtb), Dendroctonus valens. PLoS One 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125159

Gyorgyi, T. K., Roby-Shemkovitz, A. J., and Lerner, M. R. (1988). Characterization and cDNA cloning of the pheromone-binding protein from the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta: a tissue-specific developmentally regulated protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 9851–9855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9851

He, P., Chen, G. L., Li, S., Wang, J., Ma, Y. F., Pan, Y. F., et al. (2019a). Evolution and functional analysis of odorant-binding proteins in three rice planthoppers: Nilaparvata lugens, Sogatella furcifera, and Laodelphax striatellus. Pest Manag. Sci. 75, 1606–1620. doi: 10.1002/ps.5277

He, P., Durand, N., and Dong, S. L. (2019b). Editorial: insect olfactory proteins (from gene identification to functional characterization). Front. Physiol. 10:1313. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01313

He, P., Engsontia, P., Chen, G. L., Yin, Q., Wang, J., Lu, X., et al. (2018). Molecular characterization and evolution of a chemosensory receptor gene family in three notorious rice planthoppers, Nilaparvata lugens, Sogatella furcifera and Laodelphax striatellus, based on genome and transcriptome analyses. Pest Manag. Sci. 74, 2156–2167. doi: 10.1002/ps.4912

He, P., Wang, M. M., Wang, H., Ma, Y. F., Yang, S., Li, S. B., et al. (2020). Genome-wide identification of chemosensory receptor genes in the small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus. Genomics 112, 2034–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.11.016

Hekmat-Scafe, D. S., Scafe, C. R., McKinney, A. J., and Tanouye, M. A. (2002). Genome-wide analysis of the odorant-binding protein gene family in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 12, 1357–1369. doi: 10.1101/gr.239402

Hildebrand, J. G. (1995). Analysis of chemical signals by nervous systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 67–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.67

Hu, P., Wang, J., Cui, M., Tao, J., and Luo, Y. (2016). Antennal transcriptome analysis of the Asian longhorned beetle Anoplophora glabripennis. Sci. Rep. 6:26652. doi: 10.1038/srep26652

Hussain, A., Zhang, M., Ucpunar, H. K., Svensson, T., Quillery, E., Gompel, N., et al. (2016). Ionotropic chemosensory receptors mediate the taste and smell of polyamines. PLoS Biol. 14:e1002454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002454

Jacquinjoly, E., Vogt, R. G., François, M. C., and Nagnanle, M. P. (2001). Functional and ex-pression pattern analysis of chemosensory proteins expressed in antennae and pheromonal gland of Mamestra brassicae. Chem. Senses 26, 833–844. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.7.833

Jia, H. R., Niu, L. L., Sun, Y. F., Liu, Y. Q., and Wu, K. M. (2020). Odorant binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in Episyrphus balteatus (Diptera: Syrphidae): molecular cloning, expression profiling, and gene evolution. J. Insect Sci. 20:15. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieaa065

Jia, X. J., Zhang, X. F., Liu, H. M., Wang, R. Y., Zhang, T., and Gao, Y. L. (2018). Identification of chemosensory genes from the antennal transcriptome of Indian meal moth Plodia interpunctella. PLoS One 13:e0189889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189889

Jin, J. Y., Li, Z. Q., Zhang, Y. N., Liu, N. Y., and Dong, S. L. (2014). Different roles suggested by sex-biased expression and pheromone binding affinity among three pheromone binding proteins in the pink rice borer, Sesamia inferens (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Insect Physiol. 66, 71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.05.013

Jin, X., Brandazza, A., Navarrini, A., Ban, L., Zhang, S., Steinbrecht, R. A., et al. (2005). Expression and immunolocalisation of odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins in locusts. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 1156–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5014-6

Jin, X., Ha, T. S., and Smith, D. P. (2008). SNMP is a signaling component required for pheromone sensitivity in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10996–11001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803309105

Jones, W. D., Nguyen, T. A. T., Kloss, B., Lee, K. J., and Vosshall, L. B. (2005). Functional conservation of an insect odorant receptor gene across 250 millionyears of evolution. Curr. Biol. 15, 119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.007

Kaissling, K. E. (1998). Pheromone deactivation catalyzed by receptor molecules: a quantitative kinetic model. Chem. Senses 23, 385–395. doi: 10.1093/chemse/23.4.385

Kaissling, K. E. (2009). Olfactory perireceptor and receptor events in moths: a kinetic model revised. J. Comp. Physiol. A 195, 895–922. doi: 10.1007/s00359-009-0461-4

Koenig, C., Hirsh, A., Bucks, S., Klinner, C., Vogel, H., Shukla, A., et al. (2015). A reference gene set for chemosensory receptor genes of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 66, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.09.007

Larkin, M. A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N. P., Chenna, R., McGettigan, P. A., McWilliam, H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404

Larsson, M. C., Domingos, A. I., Jones, W. D., Chiappe, M. E., Amrein, H., and Vosshall, L. B. (2004). Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron 43, 703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019

Laughlin, J. D., Ha, T. S., Jones, D. N., and Smith, D. P. (2008). Activation of pheromone-sensitive neurons is mediated by conformational activation of pheromone-binding protein. Cell 133, 1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.046

Lautenschlager, C., Leal, W. S., and Clardy, J. (2007). Bombyx mori pheromone-binding protein binding non-pheromone ligands: implications for pheromone recognition. Structure 15, 1148–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.013

Leal, W. S. (2007). Rapid binding, releaseand inactivation of insect pheromones. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 148, S81–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.06.210

Leal, W. S. (2013). Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153635

Leitch, O., Papanicolaou, A., Lennard, C., Kirkbride, K. P., and Anderson, A. (2015). Chemosensory genes identified in the antennal transcriptome of the blowfly Calliphora stygia. BMC Genomics 16:255. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1466-8

Li, M. Y., Jiang, X. Y., Qi, Y. Z., Huang, Y. J., Li, S. G., and Liu, S. (2020). Identification and expression profiles of 14 odorant-binding protein genes from Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). J. Insect Sci. 20, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieaa087

Li, S., Picimbon, J. F., Ji, S., Kan, Y., Chuanling, Q., Zhou, J. J., et al. (2008). Multiple functions of an odorant-binding protein in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372, 464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.064

Li, Z. Q., Zhang, S., Luo, J. Y., Wang, S. B., Wang, C. Y., Lv, L. M., et al. (2015). Identification and expression pattern of candidate olfactory genes in Chrysoperla sinica by antennal transcriptome analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 15, 28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2015.05.002

Liu, N. Y., He, P., and Dong, S. L. (2012). Binding properties of pheromone-binding protein 1 from the common cutworm Spodoptera litura. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 161, 295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2011.11.007

Liu, N. Y., Zhang, T., Ye, Z. F., Li, F., and Dong, S. L. (2015). Identification and characterization of candidate chemosensory gene families from Spodoptera exigua developmental transcriptomes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 1036–1048. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.12020

Liu, Y., Gu, S., Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., and Wang, G. (2012). Candidate olfaction genes identified within the Helicoverpa armigera antennal transcriptome. PLoS One 7:e48260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048260

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2–Δ Δ Ct, method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Ni, L., Klein, M., Svec, K. V., Budelli, G., Chang, E. C., Ferrer, A. J., et al. (2016). The ionotropic receptors IR21a and IR25a mediate cool sensing in Drosophila. eLife 5:13254. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13254

Nibouche, S., Raboin, L. M., Hoarau, J. Y., D’Hont, A., and Costet, L. (2012). Quantitative trait loci for sugarcane resistance to the spotted stem borer Chilo sacchariphagus. Mol. Breed. 29, 129–135. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9531-0

Nibouche, S., and Tibère, R. (2010). Mechanism of resistance to the spotted stalk borer, Chilo sacchariphagus, in the sugarcane cultivar R570. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 135, 308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2010.00996.x

Nichols, Z., and Vogt, R. G. (2008). The SNMP/CD36 gene family in Diptera, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera: Drosophila melanogaster, D. pseudoobscura, Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti, Apis mellifera, and Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 398–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.11.003

Olivier, V., Monsempes, C., Francois, M. C., Poivet, E., and Jacquin-Joly, E. (2011). Candidate chemosensory ionotropic receptors in a Lepidoptera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 20, 189–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01057.x

Pearce, S. L., Clarke, D. F., East, P. D., Elfekih, S., Gordon, K. H. J., Jermiin, L. S., et al. (2017). Genomic innovations, transcriptional plasticity and gene loss underlying the evolution and divergence of two highly polyphagous and invasive Helicoverpa pest species. BMC Biol. 15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0402-6

Pelletier, J., and Leal, W. S. (2009). Genome analysis and expression patterns of odorant-binding proteins from the southern house mosquito Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. PLoS One 4:e6237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006237

Pelletier, J., and Leal, W. S. (2011). Characterization of olfactory genes in the antennae of the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 915–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.04.003

Pelosi, P., Iovinella, I., Felicioli, A., and Dani, F. R. (2014). Soluble proteins of chemical communication: an overview across arthropods. Front. Physiol. 5:320. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00320

Pelosi, P., Iovinella, I., Zhu, J., Wang, G., and Dani, F. R. (2018). Beyond chemoreception: diverse tasks of soluble olfactory proteins in insects. Biol. Rev. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 93, 184–200. doi: 10.1111/brv.12339

Pelosi, P., and Maida, R. (1995). Odorant-binding proteins in insects. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 111, 503–514. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)00019-5

Pelosi, P., Zhou, J. J., Ban, L. P., and Calvello, M. (2006). Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1658–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0

Pertea, G., Huang, X., Liang, F., Antonescu, V., Sultana, R., Karamycheva, S., et al. (2003). TIGR gene indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of largest datasets. Bioinformatics 19, 651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034

Picimbon, J.-F. J., Dietrich, K., Krieger, J., and Breer, H. (2001). Identity and expression pattern of chemosensory proteins in Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31, 1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00063-7

Poivet, E., Gallot, A., Montagné, N., Glaser, N., Legeai, F., and Jacquinjoly, E. (2013). A comparison of the olfactory gene repertoires of adults and larvae in the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis. PLoS One 8:e60263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060263

Pophof, B. (2004). Pheromone-binding proteins contribute to the activation of olfactory receptor neurons in the silkmoths Antheraea polyphemus and Bombyx mori. Chem. Senses 29, 117–125. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh012

Prestwich, G. D. (1996). Proteins that smell: pheromone recognition and signal transduction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 4, 505–513. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00033-8

Prieto-Godino, L. L., Rytz, R., Bargeton, B., Abuin, L., Arguello, J. R., Peraro, M. D., et al. (2016). Olfactory receptor pseudo-pseudogenes. Nature 539, 93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature19824

Prokupek, A. M., Eyun, S. I., Ko, L., Moriyama, E. N., and Harshman, L. G. (2010). Molecular evolutionary analysis of seminal receptacle sperm storage organ genes of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1386–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.01998.x

Quackenbush, J., Cho, J., Lee, D., Liang, F., Holt, I., Karamycheva, S., et al. (2001). The TIGR gene indices: analysis of gene transcript sequences in highly sampled eukaryotic species. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 159–164. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.159

Ramdya, P., and Benton, R. (2010). Evolving olfactory systems on the fly. Trends Genet. 26, 307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.04.004

Renwick, J. A. A., Radke, C. D., Sachdev-Gupta, K., and Städler, E. (1992). Leaf surface chemicals stimulating oviposition by Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) on cabbage. Chemoecology 3, 33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF01261454

Robertson, H. M., and Wanner, K. W. (2006). The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 16, 1395–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.5057506

Robertson, H. M., Warr, C. G., and Carlson, J. R. (2003). Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100(Suppl. 2), 14537–14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335847100

Rogers, M. E., Krieger, J., and Vogt, R. G. (2001). Antennal SNMPs (sensory neuron membrane proteins) of Lepidoptera define a unique family of invertebrate CD36-like proteins. J. Neurobiol. 49, 47–61. doi: 10.1002/neu.1065

Sallam, N., Achadian, E. M., Putra, L., Dianpratiwi, T., Kristini, A., Donald, D., et al. (2016). In search of varietal resistance to sugarcane moth borers in Indonesia. Int. Sugar J. 118, 450–452.

Sato, K., Pellegrino, M., Nakagawa, T., Nakagawa, T., Vosshall, L. B., and Touhara, K. (2008). Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature 452, 1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature06850

Sato, Y., Yano, S., Takabayashi, J., and Ohsaki, N. (1999). Pieris rapae (Ledidoptera: Pieridae) females avoid oviposition on Rorippa indica plants infested by conspecific larvae. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 34, 333–337. doi: 10.1021/cr9001676

Smart, R., Kiely, A., Beale, M., Vargas, E., Carraher, C., Kralicek, A. V., et al. (2008). Drosophila odorant receptors are novel seven transmembrane domain proteins that can signal independently of heterotrimeric G proteins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 770–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.05.002

Stocker, R. F. (1994). The organization of the chemosensory system in Drosophila melanogaster: a review. Cell Tissue Res. 275, 3–26. doi: 10.1007/bf00305372

Stork, N. E. (1993). How many species are there? Biodivers. Conserv. 2, 215–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00056669

Takemori, N., and Yamamoto, M. T. (2009). Proteome mapping of the Drosophila melanogaster male reproductive system. Proteomics 9, 2484–2493. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800795

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., and Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

Tanaka, K., Uda, Y., Ono, Y., Nakagawa, T., Suwa, M., Yamaoka, R., et al. (2009). Highly selective tuning of a silkworm olfactory receptor to a key mulberry leaf volatile. Curr. Biol. 19, 881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.035

Tang, R., Jiang, N. J., Ning, C., Li, G. C., and Wang, C. Z. (2020). The olfactory reception of acetic acid and ionotropic receptors in the oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata walker. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 118:103312. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103312

Vieira, F. G., and Rozas, J. (2011). Comparative genomics of the odorant-binding and chemosensory protein gene families across the Arthropoda: origin and evolutionary history of the chemosensory system. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 476–490. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr033

Vogt, R. G. (1995). “Molecular genetics of moth olfaction: a model for cellular identity and temporal assembly of the nervous system,” in Molecular Model Systems in the Lepidoptera, eds M. Goldsmith and A. S. Wilkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 341–367. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511529931.014

Vogt, R. G., Miller, N. E., Litvack, R., Fandino, R. A., Sparks, J., Staples, J., et al. (2009). The insect SNMP gene family. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.03.007

Vogt, R. G., and Riddiford, L. M. (1981). Pheromone binding and inactivation by moth antennae. Nature 293, 161–613. doi: 10.1038/293161a0

Vosshall, L. B., Amrein, H., Morozov, P. S., Rzhetsky, A., and Axel, R. (1999). A spatial map of olfactory receptor expression in the Drosophila antenna. Cell 96, 725–736. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80582-6

Walker, W. B., Roy, A., Anderson, P., Schlyter, F., Hansson, B. S., and Larsson, M. C. (2019). Transcriptome analysis of gene families involved in chemosensory function in Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). BMC Genomics 20:428. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5815-x

Wang, B., Liu, Y., and Wang, G. R. (2017). Chemosensory genes in the antennal transcriptome of two syrphid species, Episyrphus balteatus and Eupeodes corollae (diptera: syrphidae). BMC Genomics 18:586. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3939-4

Wanner, K. W., Anderson, A. R., Trowell, S. C., Theilmann, D. A., Robertson, H. M., and Newcomb, R. D. (2007). Female-biased expression of odourant receptor genes in the adult antennae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol. Biol. 16, 107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00708.x

Wanner, K. W., Willis, L. G., Theilmann, D. A., Isman, M. B., Feng, Q. L., and Plettner, E. (2004). Analysis of the insect os-d-like gene family. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 889–911. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000028457.51147.d4

Wei, H. S., Li, K. B., Zhang, S., Cao, Y. Z., and Yin, J. (2017). Identification of candidate chemosensory genes by transcriptome analysis in Loxostege sticticalis Linnaeus. PLoS One 12:e0174036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174036

Wicher, D. (2014). Olfactory signaling in insects. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 130, 37–54. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.002

Wicher, D., Schafer, R., Bauernfeind, R., Stensmyr, M. C., Heller, R., Heinemann, S. H., et al. (2008). Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature 452, 1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature06861

Wojtasek, H., and Leal, W. S. (1999). Conformational change in the pheromone-binding protein from Bombyx mori induced by pH and by interaction with membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30950–30956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30950

Wu, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, Z., Bin, S., He, H., and Lin, J. (2015). Discovery of chemosensory genes in the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. PLoS One 10:e0129794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129794

Xu, Q. Y., Wu, Z. Z., Zeng, X. N., and An, X. C. (2020). Identification and expression profiling of chemosensory genes in Hermetia illucens via a transcriptomic analysis. Front. Physiol. 11:720. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00720

Xu, Y. L., He, P., Zhang, L., Fang, S. Q., Dong, S. L., Zhang, Y. J., et al. (2009). Large-scale identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins from expressed sequence tags in insects. BMC Genomics 10:632. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-632

Ye, J., Fang, L., Zheng, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, Z., et al. (2006). WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 293–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031

Zhang, H. J., Xu, W., Chen, Q. M., Sun, L. N., Anderson, A., Xia, Q. Y., et al. (2020). A phylogenomics approach to characterizing sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) in Lepidoptera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 118, 103313. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103313

Zhang, J., Bisch-Knaden, S., Fandino, R. A., Yan, S., Obiero, G. F., Grosse-Wilde, E., et al. (2019). The olfactory coreceptor IR8a governs larval feces-mediated competition avoidance in a hawkmoth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 21828–21833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913485116

Zhang, J., Wang, B., Dong, S. L., Cao, D. P., Dong, J. F., Walker, W. B., et al. (2015). Antennal transcriptome analysis and comparison of chemosensory gene families in two closely related Noctuidae moths, Helicoverpa armigera and H. assulta. PLoS One 10:e0117054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117054

Zhang, L. W., Kang, K., Jiang, S. C., Zhang, Y. N., and Ding, D. G. (2016). Analysis of the antennal transcriptome and insights into olfactory genes in Hyphantria cunea (Drury). PLoS One 11:e0164729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164729

Zhang, Y. N., Ye, Z. F., Yang, K., and Dong, S. L. (2014). Antenna-predominant and male-biased csp19 of Sesamia inferens is able to bind the female sex pheromones and host plant volatiles. Gene 536, 279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.011

Zhou, J. J., Vieira, F. G., He, X. L., Smadja, C., Liu, R., Rozas, J., et al. (2010). Genome annotation and comparative analyses of the odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect. Mol. Biol. 19, 113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00919.x

Zhou, X. H., Ban, L. P., Iovinella, I., Zhao, L. J., Gao, Q., Felicioli, A., et al. (2013). Diversity, abundance and sex-specific expression of chemosensory proteins in the reproductive organs of the locust Locusta migratoria manilensis. Biol. Chem. 394, 43–54. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0114

Zhu, G. H., Xu, J., Cui, Z., Dong, X. T., Ye, Z. F., Niu, D. J., et al. (2016). Functional characterization of slitpbp3 in spodoptera litura by crispr/cas9 mediated genome editing. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.05.006

Zhu, G. H., Zheng, M. Y., Sun, J. B., Khuhro, S. A., Yan, Q., Huang, Y., et al. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene knockout reveals a more important role of PBP1 than PBP2 in the perception of female sex pheromone components in Spodoptera litura. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 115:103244. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103244

Keywords: Chilo sacchariphagus, transcriptome, chemosensory genes, gene expression, phylogenetic analysis

Citation: Liu J, Liu H, Yi J, Mao Y, Li J, Sun D, An Y and Wu H (2021) Transcriptome Characterization and Expression Analysis of Chemosensory Genes in Chilo sacchariphagus (Lepidoptera Crambidae), a Key Pest of Sugarcane. Front. Physiol. 12:636353. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.636353

Received: 01 December 2020; Accepted: 04 January 2021;

Published: 05 March 2021.

Edited by:

Xin-Cheng Zhao, Henan Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Liu, Liu, Yi, Mao, Li, Sun, An and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuxing An, eWFueGluZzg4OEAxMjYuY29t; Han Wu, YW50ZW5uYTEyMTdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Jianbai Liu1

Jianbai Liu1 Huan Liu

Huan Liu Jiequn Yi

Jiequn Yi