95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Physiol. , 29 December 2020

Sec. Clinical and Translational Physiology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.595486

This article is part of the Research Topic Acute Heart Failure: From Bench to Bedside View all 5 articles

Daniel A. Keir1

,2

Daniel A. Keir1

,2

James Duffin3

,4

,5

James Duffin3

,4

,5

John S. Floras1

John S. Floras1

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) induces chronic sympathetic activation. This disturbance is a consequence of both compensatory reflex disinhibition in response to lower cardiac output and patient-specific activation of one or more excitatory stimuli. The result is the net adrenergic output that exceeds homeostatic need, which compromises cardiac, renal, and vascular function and foreshortens lifespan. One such sympatho-excitatory mechanism, evident in ~40–45% of those with HFrEF, is the augmentation of carotid (peripheral) chemoreflex ventilatory and sympathetic responsiveness to reductions in arterial oxygen tension and acidosis. Recognition of the contribution of increased chemoreflex gain to the pathophysiology of HFrEF and to patients’ prognosis has focused attention on targeting the carotid body to attenuate sympathetic drive, alleviate heart failure symptoms, and prolong life. The current challenge is to identify those patients most likely to benefit from such interventions. Two assumptions underlying contemporary test protocols are that the ventilatory response to acute hypoxic exposure quantifies accurately peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity and that the unmeasured sympathetic response mirrors the determined ventilatory response. This Perspective questions both assumptions, illustrates the limitations of conventional transient hypoxic tests for assessing peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity and demonstrates how a modified rebreathing test capable of comprehensively quantifying both the ventilatory and sympathoneural efferent responses to peripheral chemoreflex perturbation, including their sensitivities and recruitment thresholds, can better identify individuals most likely to benefit from carotid body intervention.

The carotid bodies, located at the bifurcation of the carotid artery, contain chemosensitive cells (type I glomus cells) that respond to increased hydrogen ion concentration ([H+]) and decreased oxygen pressure (PO2) within their intracellular environment by releasing neuro-active agents to stimulate the carotid sinus nerve (Ortega-Sáenz and López-Barneo, 2020). The resulting increase in afferent input to the medulla elicits reflexive changes in both ventilation, to restore arterial PO2 (PaO2) and pH via a reduction in arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2; Prabhakar, 2013; Guyenet, 2014), and sympathetic discharge, to counter the direct vasodilatory effects of hypercapnia and hypoxia (Ainslie and Duffin, 2009; Keir et al., 2019).

The heightened sympathetic drive characteristic of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) reflects integration of compensatory baroreceptor reflex disinhibition, in response to a fall in cardiac output, and patient-specific activation of one or more excitatory stimuli arising from, for example, afferents in the atria, skeletal muscle, and kidneys (Floras and Ponikowski, 2015). The result is a net adrenergic response that exceeds homeostatic need; compromises cardiac, renal, and vascular function; and foreshortens lifespan (Floras and Ponikowski, 2015). Augmented carotid (peripheral) chemoreceptor sensitivity is one such maladaptive mechanism HFrEF (Floras and Ponikowski, 2015; van Bilsen et al., 2017). Consequently, there is an increasing interest in interventions that target the peripheral chemoreflex with the aim of moderating efferent sympathetic traffic, alleviating heart failure symptoms and prolonging life expectancy (Narkiewicz et al., 1999a; Niewinski et al., 2013; Paton et al., 2013; Schultz et al., 2013; Del Rio et al., 2015; Niewinski, 2017; Toledo et al., 2017; van Bilsen et al., 2017).

In a substantial proportion of patients with chronic HFrEF, either increased tonic chemoreceptor activity or augmented chemoreceptor reflex responsiveness to changes in PaO2 or PaCO2 (the latter stimulus applied as a pragmatic surrogate for [H+]), or both, contribute to upward resetting of the resting efferent sympathetic outflow (Di Vanna et al., 2007; Hering et al., 2007; Floras, 2009; Despas et al., 2012). For example, increased tonic activity, evident as an acute reduction in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) when the carotid body of afferent nerve activity is attenuated by inhalation of 100% O2, may be present in up to 40% of patients with HFrEF (van de Borne et al., 1996; Ponikowski et al., 2001; Andreas et al., 2003; Hering et al., 2007; Franchitto et al., 2010; Despas et al., 2012).

The subject of this perspective is not such tonic activation, but rather peripheral reflex gain or sensitivity, calculated conventionally as the ventilatory response to an acute hypoxic or hypercapnic stimulus. This has received much more attention in the HFrEF literature because of its high prevalence; the rapid fluctuations in PaCO2 and PaO2 that can occur consequent to changes in activity, behavior, and emotion; and the reported association of the hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) with prognosis. With respect to the latter, several groups have estimated that, relative to healthy subjects, peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity is augmented in up to 45% of patients with HFrEF (Narkiewicz et al., 1999b; Ponikowski et al., 2001; Giannoni et al., 2008). Such augmented hypoxic ventilatory responsiveness associates, independently, with HFrEF severity (Giannoni et al., 2008), the magnitude of MSNA (Ponikowski et al., 2001; Di Vanna et al., 2007), the presence of disordered breathing (Ponikowski et al., 1999; Solin et al., 2000; Marcus et al., 2014a,b), blunted baroreflex sensitivity (Ponikowski et al., 1997), and, in adjusted models, with foreshortened life expectancy (Ponikowski et al., 1999, 2001; Schultz and Li, 2007; Giannoni et al., 2009).

These findings have stimulated studies of the acute or chronic consequences of blunting chemoreceptor activity or carotid body resection. In a canine HFrEF model, carotid body chemoreceptor inhibition by infused dopamine increased resting hind-limb vascular conductance immediately (preceding the systemic effects of dopamine) and more so than in healthy dogs (Stickland et al., 2007). Carotid body denervation reduced resting and hypoxia-induced renal sympathetic nerve activity, disordered breathing patterns, and arrhythmia incidence in HFrEF rabbits (Marcus et al., 2014b) and rats (Del Rio et al., 2013) and improved their survival (Del Rio et al., 2013). Narkiewicz et al. (2016) reported reductions in ambulatory blood pressure and resting MSNA following unilateral carotid body resection in 8 of 15 patients with drug-resistant hypertension. Interestingly, those with a positive outcome (i.e., responders) had a greater preoperative ventilatory responsiveness to hypoxia. In a first-in-man HFrEF study of unilateral (n = 4) or bilateral (n = 6) carotid body resection, ventilatory responsiveness to decreased inspired O2 was 70% lower, 1 month after surgery, and resting MSNA fell by 9% (Niewinski et al., 2017). Such findings promoted the concept of carotid body excision as a therapeutic option to redress autonomic disequilibrium or the occurrences of central apnea.

Since eliminating oxygen sensing is not without risk (Smit et al., 2002; Timmers et al., 2003; Narkiewicz et al., 2016), the challenge is to identify those individuals most likely to benefit. Determining the HVR has been proposed for this purpose (Paton et al., 2013; Narkiewicz et al., 2016; Niewinski, 2017). Two assumptions underlying this strategy and the contemporary test protocols employed are: (1) that the ventilatory response to acute hypoxic exposure quantifies accurately peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity and (2) that the unmeasured sympathetic response is congruent with the determined ventilatory response. This perspective will question both assumptions, illustrate with two HFrEF patients as examples the limitations of conventional transient hypoxic tests for assessing peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity, and demonstrate how a modified rebreathing test (as detailed in the accompanying Supplementary Material) capable of comprehensively quantifying both the ventilatory and sympathoneural efferent responses to peripheral chemoreflex perturbation, including their sensitivities and recruitment thresholds, can better identify individuals with heart failure most likely to benefit from carotid body intervention.

Conventionally, in humans, peripheral chemoreceptor-specific responsiveness has been quantified by recording breath-by-breath ventilation (V̇E) and arterial O2 saturation (SaO2) during a transient hypoxic challenge. Popular in the HFrEF literature are protocols that lower O2 intermittently by nitrogen (N2) gas inhalation or continuously by rebreathing (Chua et al., 1996, 1997; Ponikowski et al., 1997, 1999; Niewinski et al., 2014). In the intermittent hypoxia test, a variety of exposure durations (~2–8 breaths of N2) are used to achieve a range of O2 saturations (70–100% SaO2). The peak in V̇E subsequent to each exposure duration is plotted against the nadir in SaO2. The slope of the linear regression applied to the resultant V̇E–SaO2 relationship defines the HVR in L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1 (Edelman et al., 1973). The same HVR relationship may also be constructed continuously by having participants rebreathe from a system that facilitates a smooth fall in O2 and simultaneous CO2 removal to prevent its accumulation (with the aim of minimizing O2 vs. CO2 specific responses; Rebuck and Campbell, 1974).

Applying either method, investigators report that relative to healthy age-matched controls, whose HVR is approximately ~0.35 L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1, the mean HVR of cohorts with HFrEF is on average more than two standard deviations greater (Chua et al., 1996, 1997), and consistently circa 0.75 L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1 (Ponikowski et al., 1999, 2001). Notably, compared to HFrEF patients with HVR below this value, patients with HVR values in excess of 0.77 L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1 (Giannoni et al., 2009) and 0.72 L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1 (Ponikowski et al., 2001) were found to have survival reduced by 12 and 36% over 4 and 3 years, respectively. Consequently, in patients with HFrEF, an “exaggerated” HVR response is now defined as a value ≥0.75 L∙min−1∙%SaO2 −1 (Giannoni et al., 2008, 2009; Niewinski, 2017). This threshold has been proposed for the selection of patients for carotid body interventions (Narkiewicz et al., 2016; Niewinski, 2017).

Importantly, because such transient hypoxic protocols fail to control for concurrent changes in PCO2, which will independently alter [H+] at the peripheral and central chemoreceptors (Nielsen and Smith, 1952; Hornbein and Roos, 1963; Cunningham et al., 1986; Guyenet, 2014), they often misrepresent peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity. For example, with intermittent delivery, the hypocapnia that accompanies longer N2 exposures will blunt the ventilatory response to hypoxia, leading to a lower calculated HVR. With the continuous delivery method, attempts have been made to maintain isocapnic conditions by removing excess CO2 during rebreathing. However, the choice of isocapnic PCO2 often is based on resting PCO2, which may reside above or below the PCO2 threshold at which the peripheral chemoreceptors initiate a ventilatory response to hypoxia (i.e., the ventilatory recruitment threshold, VRT; Duffin, 2007, 2011). Consequently, variation in the isocapnic PaCO2 at which patients are tested will alter HVR obscuring differences in peripheral reflex sensitivity between populations. To demonstrate these problems, in the next section, we report a single patient-participant experiment performed in our laboratory designed specifically to highlight the consequences of unstandardized PCO2 control when quantifying HVR.

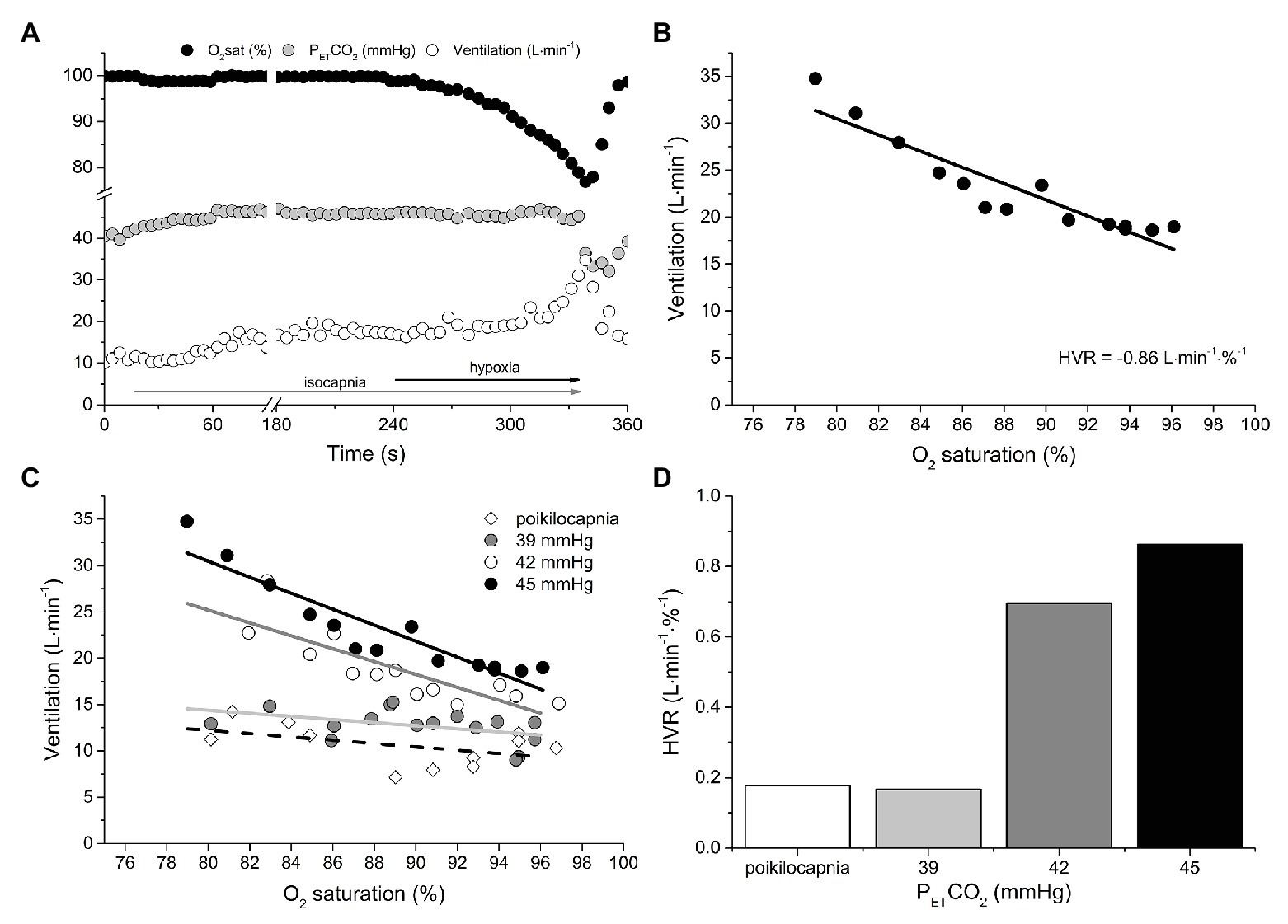

A 26-year-old male with dilated cardiomyopathy (NYHA class II, LVEF = 20%; BMI = 30 kg∙m−2) and on optimal guideline recommended heart failure therapy, underwent four transient hypoxic tests under a poikilocapnic condition, and at three isocapnic PCO2 tensions. He was seated and breathed through a facemask connected in series to a low dead space, low air resistance pulmonary filter, and a bidirectional volume turbine (UVM, VacuMed, Ventura, CA, USA). The volume turbine measured expired volumes and was directly attached on its distal end to a sequential gas delivery circuit (Duffin, 2011).

Respired air was continuously sampled at the mouth and analyzed for the fractional concentrations of O2 and CO2 (17500B, VacuMed, Ventura, CA, USA). Respiratory volumes and fractional gas concentrations were recorded at a frequency of 50 Hz via a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments Inc., Austin, TX, USA) and then transferred to a computer. Custom software aligned the gas concentrations and volume signals and executed a peak-detection program to determine the end-tidal partial pressures of O2 (PETO2) and CO2 (PETCO2), tidal volumes, breathing frequencies and V̇E on a breath-by-breath basis. Oxygen saturation (SaO2) was monitored at the ear using a pulse oximeter (Nonin 7500, Plymouth, MN, USA).

The sequential gas delivery circuit comprised a non-rebreathing valve, an expiratory gas reservoir, and an inspiratory gas reservoir supplied by a flow-controlled gas blender. A one-way crossover valve between the expiratory gas reservoir and the inspiratory limb permitted rebreathing of previously expired gas at the end of inspiration when ventilation exceeded the flow of fresh gas delivered into the circuit. In this way, the volume and composition of gas available for gas exchange was manipulated to allow precise control of alveolar ventilation and arterial blood gases independent of V̇E. To measure isocapnic HVR, the flow of fresh gas was fixed (which sets isocapnic PETCO2), and the fractional composition of O2 was lowered progressively over the course of 90 s to achieve a decrement in SaO2 from 95 to 80%.

The HVR was determined under three isocapnic conditions: (1) at resting PETCO2 (39 mmHg); (2) at +3 mmHg above resting PETCO2 (42 mmHg); and (3) at +6 mmHg above resting PETCO2 (45 mmHg). In a fourth test, HVR was measured without PETCO2 control (poikilocapnia). As increasing PETCO2 above resting levels will also increase central PCO2, a 4-min baseline period of isocapnic normoxia preceded each HVR test to ensure that ventilatory responses to PCO2 by the central chemoreceptors were complete before the induction of hypoxia. Further, to ensure that ventilatory drive from central chemoreceptors remained constant throughout hypoxic exposure, the HVR test was limited to 90 s to prevent hypoxia-mediated increases in cerebral blood flow from lowering central PCO2 (Duffin, 2007; Ainslie and Duffin, 2009).

Figure 1 provides an example of the breath-by-breath responses to the transient HVR test with PETCO2 maintained at 45 mmHg (Figure 1A) and the resultant HVR (Figure 1B). Figures 1C,D include the HVR data from all four tests. Note that the HVR varied with isocapnic PCO2 tension; with greater levels of isocapnia, the sensitivity of the peripheral chemoreceptors to hypoxia is increased, resulting in a greater HVR. In contrast, during the poikilocapnic test, PCO2 fell as V̇E rose, and the ventilatory response to hypoxia was nearly eliminated.

Figure 1. An example of the measurement of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity using the continuous transient hypoxic method in an isocapnic condition (A). The rise in ventilation (V̇E) is plotted against the fall in oxygen saturation to build a regression function (B). The slope of this function, or hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), is considered a measure of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity (liters per minute per % oxygen saturation). (C,D) show the effect of isocapnic CO2 tension (PCO2) on HVR. Note that the HVR varied with isocapnic PCO2 tension; with greater levels of isocapnia, the sensitivity of the peripheral chemoreceptors to hypoxia is increased, resulting in a greater HVR. In contrast, during the poikilocapnic test, PCO2 fell as V̇E rose, and the ventilatory response to hypoxia was nearly eliminated. See text for details.

This experiment demonstrates that, depending on the selected level of isocapnia, the same individual can have a different HVR. Note also that, with higher PETCO2, the regression lines are shifted upward, reflecting increasing ventilatory drive from central chemoreceptors. Had the transient hypoxia not been preceded by 4 min of normocapnic isocapnia, a contribution of the central chemoreceptor to V̇E would also be present in the HVR response. These observations question the validity of such an HVR test to label a peripheral chemoreflex as “exaggerated.” In this specific example, depending on which isocapnic PCO2 tension is used, the patient’s HVR is either above or below the proposed definition of “exaggerated” peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity, i.e., 0.75 L min−1∙%SaO2 −1.

Augmented ventilatory responses to isocapnic and poikilocapnic hypoxia are reportedly present in 30–60% of HFrEF patients (Narkiewicz et al., 1999b; Ponikowski et al., 1999, 2001; Hering et al., 2007; Giannoni et al., 2008, 2009; Despas et al., 2012). However, these data are derived almost exclusively from transient hypoxic tests. As we and others (Read et al., 1977; Duffin, 2011; Powell, 2012) have illustrated, under conditions of unstandardized PCO2 control, these tests cannot characterize peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity nor can they reliably discriminate between patients whose sensitivities differ. Also worth considering are that HFrEF patients often exhibit prolonged lung to carotid body circulatory times (Hall et al., 1996) and Cheyne-Stokes breathing patterns (van de Borne et al., 1996), which can further confound the HVR to transient hypoxia by obscuring the alignment of the independent (SaO2) and dependent (V̇E) variables. Consequently, because the HVR test result is dependent on the isocapnic PCO2, and methods to appropriately standardize PCO2 control during transient hypoxic tests have not been employed, we question whether the current normative data labeling peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in HFrEF as “augmented” are appropriate.

Within an individual, the HVR will depend on three variables: (1) the severity of the hypoxic stimulus (PO2); (2) the individual’s responsiveness to PO2 at the prevailing PCO2 (peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity); and (3) the proximity of the prevailing PCO2 to the PCO2 of the peripheral chemoreflex VRT. To determine peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity from HVR measurements, it requires (at least) two HVR tests at two isocapnic PCO2 tensions that are both above the PCO2 of the peripheral chemoreflex VRT. In this way, the change in HVR for the change in PCO2 gives a slope reflective of the peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity. For example, in Figure 1, it is evident that the peripheral chemoreflex VRT resides at a PCO2 between 39 and 42 mmHg. Therefore, the difference in HVR at 42 and 45 mmHg of PCO2 (0.87 vs. 0.71 L·min−1·%−1) divided by the change in PCO2 (45 vs. 42 mmHg) gives 0.05 L·min−1·%−1 mmHg−1, an estimate of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity, standardized for PCO2, that can be appropriately compared to other individuals. Note that, in this case, the two isocapnic HVR measurements are made at PCO2 tensions above the known VRT. However, the VRT is unknown in steady-state experiments and cannot be assumed to coincide with eupneic PCO2. Moreover, the HVR has to be measured: (i) after the central respiratory chemoreflex response to isocapnia establishes a steady state; and (ii) for a brief duration to minimize the impact of hypoxic ventilatory decline on HVR. Importantly, in HFrEF, methods to appropriately standardize PCO2 during transient hypoxic tests have not been employed.

To circumvent the issues associated with standardizing the effect of PCO2 on the peripheral chemoreflex response to hypoxia (i.e., HVR), we suggest the reverse, measuring the effect of hypoxia on the peripheral chemoreflex response to PCO2. This measurement recognizes that the carotid chemoreceptors are [H+] sensors with excitability to CO2 that is modulated by PO2 (Torrance, 1996); Duffin introduced a rebreathing protocol specifically designed to characterize the responsiveness of the peripheral chemoreflex in humans (Duffin, 2007). The ventilatory response to graded hypercapnia is measured twice, with end-tidal PO2 maintained throughout rebreathing at high (PETO2 > 150 mmHg) or low (PETO2 < 70 mmHg) tensions. In some species, central and peripheral respiratory drives have been shown to interact, as demonstrated by several laboratories (Day and Wilson, 2009; Smith et al., 2015), but this is not the case in humans in whom the hypoxic condition summates the contributions of the central and peripheral chemoreceptors to the net ventilatory drive (Clement et al., 1992, 1995; St Croix et al., 1996; Cui et al., 2012). Consequently, the difference between the hyperoxic and hypoxic test results yields the peripheral chemoreflex responsiveness (Duffin, 2007). Evidence of this physiological principle is presented in detail in the Supplementary Material.

The test is preceded by 3–5 min of volitional hyperventilation to reduce CO2 stores and initiate rebreathing from a PCO2 below the threshold PCO2 at which the chemoreceptors initiate an increase in ventilation (i.e., VRT). The inspiratory bag contains a PCO2 close to resting venous during hyperventilation (~35 mmHg) such that initiation of rebreathing, post-hyperventilation, causes rapid equilibration of inspired, alveolar, arterial, and venous PCO2 and temporal alignment of the stimulus (i.e., CO2) for both central and peripheral chemoreceptors (Read, 1967; Duffin, 2011). Throughout rebreathing, inspired CO2 is a function of the previously expired PCO2 creating a “ramp” function of PCO2 – the slope of the ventilatory response gives the sensitivity in L∙min−1∙mmHg−1. Importantly, the preceding hyperventilation period, which does not induce short-term potentiation of breathing (Rapanos and Duffin, 1997), permits identification of the VRT, and the rebreathing ramp duration (~4 min) is short enough to avoid hypoxic ventilatory decline (Duffin, 2007). The interested reader seeking a more detailed exposition of the body of literature validating the assumptions intrinsic to this rebreathing protocol is invited to read the accompanying Supplementary Material, as well as previous work by Duffin and others (Duffin, 2007, 2011; Ainslie and Duffin, 2009; Powell, 2012; Duffin and Mateika, 2013; Guyenet et al., 2018).

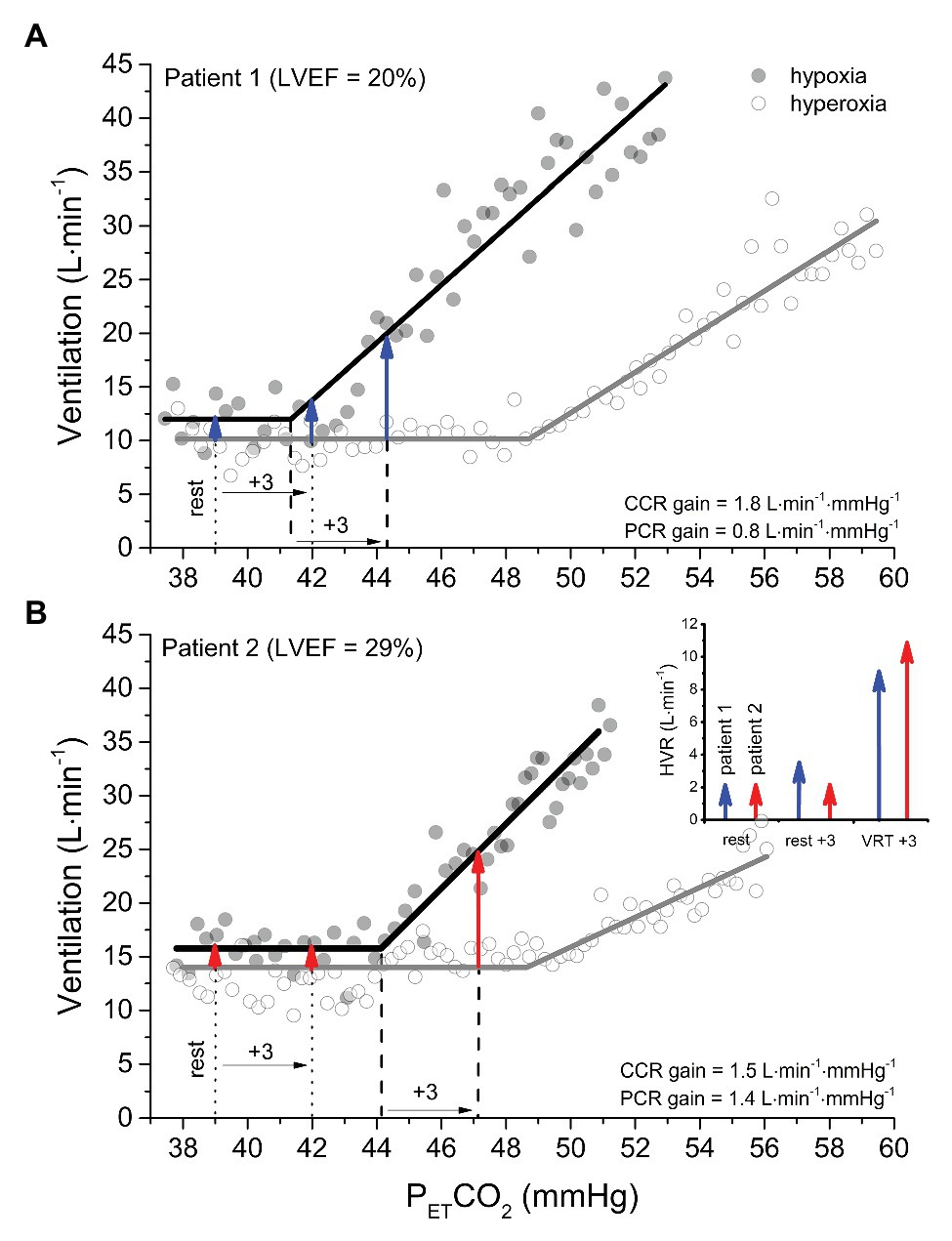

Figure 2A shows the ventilatory response to hyperoxic (PETO2 = 150 mmHg; O2sat = 100%) and hypoxic (PETO2 = 50 mmHg; O2sat = 83%) rebreathing in the same patient as depicted in Figure 1. Because a PETO2 of ~150 mmHg largely desensitizes the peripheral chemoreflex (Lloyd et al., 1957; Lahiri et al., 1993) without independently stimulating ventilation (Becker et al., 1996; also see Supplementary Material), the PCO2 at which V̇E begins to rise gives the VRT of the central chemoreflex (i.e., 49 mmHg) and the slope of the linear rise in V̇E, thereafter giving its sensitivity or gain (i.e., 1.8 L min−1 mmHg−1). The gain of the V̇E vs. PETCO2 response in the hypoxic trial reflects the additive effects of simultaneous central and peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation (i.e., 2.6 L∙min−1 mmHg−1) and, thus, the difference in gain between hypoxic and hyperoxic trials yields the peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity (0.8 L∙min−1∙mmHg−1).

Figure 2. A comparison of isoxic hyperoxic (PO2 = 150 mmHg) ventilatory responses to CO2 (white circles and gray lines) with isoxic hypoxic (PO2 = 50 mmHg) ventilatory responses to CO2 (black circles and black lines) between two patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Note that the gain (or sensitivity) is less in patient 1 (A) vs patient 2 (B). However, the ventilatory recruitment threshold (VRT) for the peripheral chemoreflex (PCR) occurs at a higher PCO2 in patient 2 vs. 1. The arrows provide an estimation of the HVR attributable to the PCR at isocapnic PCO2 corresponding to rest, +3 mmHg above rest, and + 3 mmHg above the VRT for patient 1 (blue arrows) and patient 2 (red arrows). After determining the ventilation at an isocapnic PCO2 in hyperoxia to measure the central chemoreflex (CCR) contribution, hypoxia is introduced, and the ventilation measured again at the isocapnic PCO2. Because patient 2 has a great VRT than patient 1, the HVR corresponding isocapnic PCO2 at rest and + 3 mmHg above rest incorrectly indicate that the PCR sensitivity of patient 1 is the same or greater than patient 2. By contrast, when hypoxia is introduced at an isocapnic PCO2 of +3 mmHg above the VRT, the HVR correctly reveals the PCR gain of patient 2 is greater than patient 1.

Under hypoxic conditions, the VRT of the peripheral chemoreflex is revealed (i.e., 41 mmHg). Equally important is that the PCO2 at the VRT from modified rebreathing does not translate equally to steady-state experiments due to the reinstitution of a central-arterial PCO2 difference, which, depending on its magnitude, can contribute to a 2–4 mmHg reduction in VRT (Mohan et al., 1999; Ainslie and Duffin, 2009). Rebreathing vs. steady-state differences notwithstanding, this feature of the peripheral chemoreflex is of critical importance in the evaluation of its sensitivity, because it dictates that HVR measured from an acute hypoxic stimulus depends on PCO2. For example, the resting PETCO2 of the patient-participant featured in Figure 1A is 39 mmHg, which is ~2 mmHg, i.e., below the VRT of the peripheral chemoreflex. Assuming that the difference between hypoxic and hyperoxic responses provides an estimate of the acute HVR at any given PCO2, if the patient was exposed to a bolus of hypoxic gas (e.g., PETO2 = 50 mmHg; O2sat = 83%) with PETCO2 isocapnic at 39 mmHg, one would expect very little change in V̇E (HVR < 2 L min−1; see the first blue arrow in Figure 2A). By contrast, the same hypoxic stimulus applied to this patient with PETCO2 isocapnic at 44 mmHg (+3 mmHg above VRT) would elicit an HVR that is 5-fold greater (~10 L min−1). These important aspects of the peripheral chemoreflex are internally consistent with the data presented in Figure 1D: the HVR of the patient is quite low with PETCO2 maintained below the VRT (i.e., 39 mmHg) but increases dramatically with PETCO2 maintained at +1 (42 mmHg) and + 4 mmHg (45 mmHg) above the peripheral chemoreflex VRT.

The blue arrows signifying HVR in Figure 2A assume for simplicity that the PCO2 at the peripheral and central chemoreceptors is identical. However, it is important to note that a central-arterial PCO2 difference of ~10 mmHg exists, which varies depending on PaCO2 via its effect on medullary blood flow (Ainslie and Duffin, 2009). For this reason, at any isocapnic PETCO2, the magnitude of HVR will reflect peripheral chemoreceptor sensitivity only after central chemoreceptor responses to the altered medullary PCO2 attain a steady state. Figure 1C demonstrates this effect: with higher isocapnic PCO2 tensions, the regression lines are shifted increasingly upward (even at normal arterial O2 saturation) due to heightened ventilatory drive from the central chemoreceptors. Such confounding factors must be considered when evaluating HVR.

Consideration of the VRT of the peripheral chemoreflex becomes even more important when the objective is to compare HVR between patients with a condition such as HFrEF, whether for prognostic or interventional purposes. Figure 2B displays the ventilatory response to a modified rebreathing test for a 43-year-old female with dilated cardiomyopathy (NYHA class II, LVEF = 29%; BMI = 37 kg∙m−2). Compared to the patient in Figure 2A, her resting PETCO2 is the same (39 mmHg), but both her peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity and VRT are higher (1.4 vs. 0.8 L∙min−1∙mmHg−1 and 44 vs. 41 mmHg, Patient 2 vs. Patient 1, respectively). The graph inset within Figure 2B illustrates the predicted HVR for both patients with PETCO2 maintained at rest, +3 mmHg above rest, and + 3 mmHg above VRT. Note that only when measured at a standard PETCO2 increment above each patients’ VRT will the HVR correctly indicate that the peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity of Patient 2 is greater than Patient 1. For these reasons, transient hypoxic HVR tests are only capable of identifying differences in peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity between patients when performed at the same PETCO2 increment above the peripheral chemoreflex VRT and after central chemoreceptor responses have been given time to stabilize.

Prior research has focused on ventilation as the primary efferent arm of the peripheral chemoreflex and few studies have examined both ventilatory and sympathetic responses to hypoxia in HFrEF. Recording simultaneously breath-by-breath V̇E and MSNA from the fibular nerve during modified rebreathing in healthy young men, we published the first in-human characterization of the sympathetic stimulus-response properties of central and peripheral chemoreflexes (Keir et al., 2019). In response to graded hypercapnia, we discovered that, like ventilation below a threshold PCO2, MSNA is unchanged in both hypoxic and hyperoxic conditions, while above this PCO2 threshold, MSNA rises linearly with PCO2.

The linear rises in MSNA and ventilation occurred simultaneously above similar PCO2 thresholds suggesting, in accordance with previous thinking (Guyenet, 2014), that chemoreflex-mediated ventilatory and sympathetic responses to peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation are initiated by common afferent input to the central nervous system. However, when the rates of rise in either V̇E and MSNA were plotted against changes in PETCO2, there was no correlation between such slope or sensitivities. Consistent with the notion that the carotid body acts via distinct pathways in the regulation of sympathetic and respiratory output (Zera et al., 2019), these findings challenge current beliefs that those who breathe vigorously with peripheral chemoreceptor activation incur an equally vigorous noradrenergic response (i.e., their sensitivities are not equivalent). Moreover, amplified hemodynamic swings plus stimulation of pulmonary stretch receptors, consequent to the ventilatory instability engendered by a hypersensitive chemoreflex, will perturb MSNA indirectly, via baroreceptor- and ancillary-reflex mechanisms. Inter-individual differences in carotid chemoreceptor-baroreceptor interactions may be one source of such variability in health and disease (Somers et al., 1991; Janssen et al., 2018; Heusser et al., 2020). Although derived from experiments involving healthy young men, without contrary data from human HFrEF patients, such findings caution against therapeutic targeting of the carotid body solely on the basis of ventilatory responsiveness to hypoxia.

Carotid body tonicity, inferred by the magnitude of the fall in either ventilation or MSNA in response to transient hyperoxia at eupneic PCO2, could also identify HFrEF patients who might benefit from carotid body intervention. However, to our knowledge, no longitudinal studies thus far have associated peripheral chemoreceptor tone to survival in this population. Importantly, a recent publication, involving cohorts with hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, subjected to steady-state hypoxia with PCO2 maintained eucapnic also documented discordance between reflex ventilatory and sympathoneural response to this stimulus (Prasad et al., 2020).

Several recent original contributions and reviews identify the peripheral chemoreceptors as a source of sympathetic excitation in HFrEF and as a therapeutic target (Niewinski et al., 2013, 2017; Paton et al., 2013; Schultz et al., 2013; Marcus et al., 2014b; Del Rio et al., 2015; Niewinski, 2017; Toledo et al., 2017). But, are present data and testing methods of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity sufficient to justify interventions as radical as carotid body resection or denervation? This focus on the carotid body as a therapeutic target is largely based on a reportedly high prevalence and independent prognostic value of augmented peripheral chemoreflex HVR (i.e., sensitivity) in the HFrEF population measured from brief hypoxic exposures (Chua et al., 1997; Ponikowski et al., 2001; Giannoni et al., 2009) rather than the sympathetic responsiveness per se. Importantly, this method of assessing peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity has known intrinsic limitations (Duffin, 2007, 2011; Powell, 2012), and the assumption of concordance between the ventilatory and sympathetic arms of the peripheral chemoreflex in HFrEF has been refuted in healthy individuals (Keir et al., 2019) and in those with OSA (Prasad et al., 2020). Investigations in HFrEF are underway (Keir et al., 2020). Before patients are recommended for well-intentioned interventions, such as carotid body ablation, on the basis of the current transient HVR test (Niewinski et al., 2013; Niewinski, 2017), it would be prudent first to establish the optimum testing methodology and to generate and validate normative and pathological test values. The advantages of the rebreathing test that we propose are that it addresses the critical importance of identifying, for each individual studies, the personal threshold at which PCO2 triggers the ventilatory and sympathetic peripheral chemoreflexes when endeavoring to calculate her or his peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity slope; it rectifies the deficiencies of other previously published methods, and having been adopted without difficulty by laboratories without prior expertise, it is demonstrably feasible in practice.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University Health Network Research Ethics Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All experiments were performed in the Clinical Cardiovascular Physiology Laboratory (6ES413), Department of Medicine, Toronto General Hospital. DK, JD, and JF contributed to the conception and design of the experiments. DK collected, analyzed, and interpreted data and drafted and revised the manuscript. JD and JF contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Experiments were funded by a project grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT 159491 to JF). DK is a recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. JF was supported by the Canada Research Chair in Integrative Cardiovascular Biology.

JD has equity in Thornhill Medical and receives salary support from Thornhill Medical. Thornhill Medical provided no other support for the study.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.595486/full#supplementary-material

Ainslie, P. N., and Duffin, J. (2009). Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. AJP Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296, R1473–R1495. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91008.2008

Andreas, S., Bingeli, C., Mohacsi, P., Luscher, T. F., and Noll, G. (2003). Nasal oxygen and muscle sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Chest 123, 366–371. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.366

Becker, H. F., Polo, O., Mcnamara, S. G., Berthon-Jones, M., and Sullivan, C. E. (1996). Effect of different levels of hyperoxia on breathing in healthy subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 81, 1683–1690.

Chua, T. P., Clark, A. I., Amadi, A. A., and Coats, A. J. (1996). Relation between chemosensitivity and the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 27, 650–657.

Chua, T. P., Ponikowski, P., Webb-Peploe, K., Harrington, D., Anker, S. D., Piepoli, M., et al. (1997). Clinical characteristics of chronic heart failure patients with an augmented peripheral chemoreflex. Eur. Heart J. 18, 480–486.

Clement, I. D., Bascom, D. A., Conway, J., Dorrington, K. L., O’Connor, D. F., Painter, R., et al. (1992). An assessment of central-peripheral ventilatory chemoreflex interaction in humans. Respir. Physiol. 88, 87–100. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90031-Q

Clement, I. D., Pandit, J. J., Bascom, D. A., Dorrington, K. L., O’Connor, D. F., and Robbins, P. A. (1995). An assessment of central-peripheral ventilatory chemoreflex interaction using acid and bicarbonate infusions in humans. J. Physiol. 485, 561–570. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020752

Cui, Z., Fisher, J. A., and Duffin, J. (2012). Central-peripheral respiratory chemoreflex interaction in humans. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 180, 126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.11.002

Cunningham, D. J. C., Robbins, P. A., and Wolff, C. B. (1986). “Integration of respiratory responses to changes in alveolar partial pressures of CO2 and O2 and in arterial pH” in Handbook of physiology section 3, the respiratory system. eds. A. P. Fishman, N. S. Chermiack, and J. G. Widdicombe (Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society), 475–528.

Day, T. A., and Wilson, R. J. A. (2009). A negative interaction between brainstem and peripheral respiratory chemoreceptors modulates peripheral chemoreflex magnitude. J. Physiol. 587, 883–896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160689

Del Rio, R., Andrade, D. C., Marcus, N. J., and Schultz, H. D. (2015). Selective carotid body ablation in experimental heart failure: a new therapeutic tool to improve cardiorespiratory control. Exp. Physiol. 100, 136–142. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.079566

Del Rio, R., Marcus, N. J., and Schultz, H. D. (2013). Carotid chemoreceptor ablation improves survival in heart failure: rescuing autonomic control of cardiorespiratory function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 2422–2230. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.079

Despas, F., Lambert, E., Vaccaro, A., Labrunee, M., Franchitto, N., Lebrin, M., et al. (2012). Peripheral chemoreflex activation contributes to sympathetic baroreflex impairment in chronic heart failure. J. Hypertens. 30, 753–760. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350136c

Di Vanna, A., Maria, A., Braga, F. W., Laterza, M. C., Ueno, L. M., Urbana, M., et al. (2007). Blunted muscle vasodilatation during chemoreceptor stimulation in patients with heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H846–H852. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00156.2007

Duffin, J. (2007). Measuring the ventilatory response to hypoxia. J. Physiol. 584, 285–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138883

Duffin, J. (2011). Measuring the respiratory chemoreflexes in humans. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 177, 71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.009

Duffin, J., and Mateika, J. H. (2013). Cross-Talk opposing view: peripheral and central chemoreflexes have additive effects on ventilation in humans. J. Physiol. 591, 4351–4353. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.256800

Edelman, N. H., Epstein, P. E., Lahiri, S., and Cherniack, N. S. (1973). Ventilatory responses to transient hypoxia and hypercapnia in man. Respir. Physiol. 17, 302–314.

Floras, J. S. (2009). Sympathetic nervous system activation in human heart failure: clinical implications of an updated model. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54, 375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.061

Floras, J. S., and Ponikowski, P. (2015). The sympathetic/parasympathetic imbalance in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 36, 1974–1982. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv087

Franchitto, N., Despas, F., Labrunée, M., Roncalli, J., Boveda, S., Galinier, M., et al. (2010). Tonic chemoreflex activation contributes to increased sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure-related anemia. Hypertension 55, 1012–1017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146779

Giannoni, A., Emdin, M., Bramanti, F., Iudice, G., Francis, D. P., Barsotti, A., et al. (2009). Combined increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia and hypercapnia as a prognosticator in heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.030

Giannoni, A., Emdin, M., Poletti, R., Bramanti, F., Prontera, C., Piepoli, M., et al. (2008). Clinical significance of chemosensitivity in chronic heart failure: influence on neurohormonal derangement, Cheyne-Stokes respiration and arrhythmias. Clin. Sci. 114, 489–497. doi: 10.1042/CS20070292

Guyenet, P. G. (2014). Regulation of breathing and autonomic outflows by chemoreceptors. Compr. Physiol. 4, 1511–1562. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140004

Guyenet, P. G., Bayliss, D. A., Stornetta, R. L., Kanbar, R., Shi, Y., Holloway, B. B., et al. (2018). Interdependent feedback regulation of breathing by the carotid bodies and the retrotrapezoid nucleus. J. Physiol. 596, 3029–3042. doi: 10.1113/JP274357

Hall, M. J., Xie, A., Rutherford, R., Ando, S., Floras, J. S., and Bradley, T. D. (1996). Cycle length of periodic breathing in patients with and without heart failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 376–381. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756809

Hering, D., Zdrojewski, Z., Kró, L. E., Kara, T., Kucharska, W., Somers, V. K., et al. (2007). Tonic chemoreflex activation contributes to the elevated muscle sympathetic nerve activity in patients with chronic renal failure. J. Hypertens. 25, 157–161. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280102d92

Heusser, K., Thöne, A., Lipp, A., Menne, J., Beige, J., Reuter, H., et al. (2020). Efficacy of electrical baroreflex activation is independent of peripheral chemoreceptor modulation. Hypertension 75, 257–264. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13925

Hornbein, T. F., and Roos, A. (1963). Specificity of H ion concentration as a carotid chemoreceptor stimulus. J. Appl. Physiol. 18, 580–584. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.3.580

Janssen, C., Grassi, G., Laude, D., and Van De Borne, P. (2018). Sympathetic baroreceptor regulation during hypoxic hypotension in humans: new insights. J. Hypertens. 36, 1188–1194. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001653

Keir, D. A., Duffin, J., Badrov, M. B., Alba, A. C., and Floras, J. S. (2020). Hypercapnia during wakefulness attenuates ventricular ectopy: observations in a yong man with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 13:e006837. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006837

Keir, D. A., Duffin, J., Millar, P. J., and Floras, J. S. (2019). Simultaneous assessment of central and peripheral chemoreflex regulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity and ventilation in healthy young men. J. Physiol. 597, 3281–3296. doi: 10.1113/JP277691

Lahiri, S., Rumsey, W. L., Wilson, D. F., and Iturriaga, R. (1993). Contribution of in vivo microvascular PO2 in the cat carotid body chemotransduction. J. Appl. Physiol. 75, 1035–1043. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1035

Lloyd, B., Jukes, M., and Cunningham, D. J. C. (1957). The relation between alveolar oxygen pressure and the respiratory response to carbon dioxide in man. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 43, 214–227.

Marcus, N. J., Del Rio, R., and Schultz, H. D. (2014a). Central role of carotid body chemoreceptors in disordered breathing and cardiorenal dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Front. Physiol. 5, 1–7. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00438

Marcus, N. J., Del Rio, R., Schultz, E. P., Xia, X. -H., Schultz, H. D., and Schultz, H. D. (2014b). Carotid body denervation improves autonomic and cardiac function and attenuates disordered breathing in congestive heart failure. J. Physiol. 592, 391–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266221

Mohan, R. M., Amara, C. E., Cunningham, D. A., and Duffin, J. (1999). Measuring central-chemoreflex sensitivity in man: rebreathing and steady-state methods compared. Respir. Physiol. 115, 23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(99)00003-1

Narkiewicz, K., Pesek, C. A., Van De Borne, P. J. H., Kato, M., and Somers, V. K. (1999b). Enhanced sympathetic and ventilatory responses to central chemoreflex activation in heart failure. Circulation 100, 262–267.

Narkiewicz, K., Ratcliffe, L. E. K., Hart, E. C. J., Briant, L. J. B., Chrostowska, M., Wolf, J., et al. (2016). Unilateral carotid body resection in resistant hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic Transl. Sci. 1, 313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.06.004

Narkiewicz, K., Van De Borne, P. J. H., Pesek, C. A., Dyken, M. E., Montano, N., and Somers, V. K. (1999a). Selective potentiation of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 99, 1183–1189.

Nielsen, M., and Smith, H. (1952). Studies on the regulation of respiration in acute hypoxia. Acta Physiol. Scand. 24, 293–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1952.tb00847.x

Niewinski, P. (2017). Carotid body modulation in systolic heart failure from the clinical perspective. J. Physiol. 595, 53–61. doi: 10.1113/JP271692

Niewinski, P., Janczak, D., Rucinski, A., Jazwiec, P., Sobotka, P. A., Engelman, Z. J., et al. (2013). Carotid body removal for treatment of chronic systolic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 2506–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.011

Niewinski, P., Janczak, D., Rucinski, A., Tubek, S., Engelman, Z. J., Jazwiec, P., et al. (2014). Dissociation between blood pressure and heart rate response to hypoxia after bilateral carotid body removal in men with systolic heart failure. Exp. Physiol. 99, 552–561. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075580

Niewinski, P., Janczak, D., Rucinski, A., Tubek, S., Engelman, Z. J., Piesiak, P., et al. (2017). Carotid body resection for sympathetic modulation in systolic heart failure: results from first-in-man study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 391–400. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.641

Ortega-Sáenz, P., and López-Barneo, J. (2020). Physiology of the carotid body: from molecules to disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 82, 127–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114427

Paton, J. F. R., Sobotka, P. A., Fudim, M., Engleman, Z. J., Hart, E. C. J., McBryde, F. D., et al. (2013). The carotid body as a therapeutic target for the treatment of sympathetically mediated diseases. Hypertension 61, 5–13. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00064

Ponikowski, P., Anker, S. D., Chua, T. P., Francis, D., Banasiak, W., Poole-Wilson, P. A., et al. (1999). Oscillatory breathing patterns during wakefulness in patients with chronic heart failure clinical implications and role of augmented peripheral chemosensitivity. Circulation 100, 2418–2424. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.24.2418

Ponikowski, P., Chua, T. P., Anker, S. D., Francis, D. P., Doehner, W., Banasiak, W., et al. (2001). Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity an ominous sign in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 104, 544–549. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093699

Ponikowski, P., Chua, T. P., Piepoli, M., Ondusova, D., Webb-Peploe, K., Harrington, D., et al. (1997). Augmented peripheral chemosensitivity as a potential input to baroreflex impairment and autonomic imbalance in chronic heart failure. Circulation 96, 2586–2594. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.8.2586

Powell, F. L. (2012). Measuring the respiratory chemoreflexes in humans by J. Duffin. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 181, 44–45. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.01.007

Prabhakar, N. R. (2013). Sensing hypoxia: physiology, genetics and epigenetics. J. Physiol. 591, 2245–2257. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.247759

Prasad, B., Morgan, B. J., Gupta, A., Pegelow, D. F., Teodorescu, M., Dopp, J. M., et al. (2020). The need for specificity in quantifying neurocirculatory vs. respiratory effects of eucapnic hypoxia and transient hyperoxia. J. Physiol. 598, 4803–4819. doi: 10.1113/JP280515

Rapanos, T., and Duffin, J. (1997). The ventilatory response to hypoxia below the carbon dioxide threshold. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 22, 23–36. doi: 10.1139/h97-003

Read, D., Nickolls, P., and Hensley, M. (1977). Instability of the carbon dioxide stimulus under the “mixed venous isocapnic” conditions advocated for testing the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 116, 336–339. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.2.336

Read, D. J. (1967). A clinical method for assessing the ventilatory response to carbon dioxide. Australas. Ann. Med. 16, 20–32. doi: 10.1111/imj.1967.16.1.20

Rebuck, A. S., and Campbell, E. J. M. (1974). A clinical method for assessing the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 109, 345–350. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.109.3.345

Schultz, H. D., and Li, Y. L. (2007). Carotid body function in heart failure. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 157, 171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.011

Schultz, H. D., Marcus, N. J., and Del Rio, R. (2013). Role of the carotid body in the pathophysiology of heart failure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 15, 356–362. doi: 10.1007/s11906-013-0368-x

Smit, A. A. J., Timmers, H. J. L. M., Wieling, W., Wagenaar, M., Marres, H. A. M., Lenders, J. W. M., et al. (2002). Long-term effects of carotid sinus denervation on arterial blood pressure in humans. Circulation 105, 1329–1335. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105744

Smith, C. A., Blain, G. M., Henderson, K. S., and Dempsey, J. A. (2015). Peripheral chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO2: role of carotid body CO2. J. Physiol. 593, 4225–4243. doi: 10.1113/JP270114

Solin, P., Roebuck, T., Johns, D. P., Walters, E. H., and Naughton, M. T. (2000). Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162, 2194–2200. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024

Somers, V. K., Mark, A. L., and Abboud, F. M. (1991). Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. J. Clin. Invest. 87, 1953–1957.

St Croix, C. M., Cunningham, D. A., Paterson, A., and Paterson, D. H. (1996). Nature of the interaction between central and peripheral chemoreceptor drives in human subjects. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 74, 640–646. doi: 10.1139/y96-049

Stickland, M. K., Miller, J. D., Smith, C. A., and Dempsey, J. A. (2007). Carotid chemoreceptor modulation of regional blood flow distribution during exercise in health and chronic heart failure. Circ. Res. 100, 1371–1378. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000266974.84590.d2

Timmers, H. J. L. M., Wieling, W., Karemaker, J. M., and Lenders, J. W. M. (2003). Denervation of carotid baro- and chemoreceptors in humans. J. Physiol. 553, 3–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052415

Toledo, C., Andrade, D. C., Lucero, C., Schultz, H. D., Marcus, N. J., Retamal, M., et al. (2017). Contribution of peripheral and central chemoreceptors to sympatho-excitation in heart failure. J. Physiol. 595, 43–51. doi: 10.1113/JP272075

Torrance, R. W. (1996). “Prolegomena: chemoreception upstream of transmitters” in Frontiers in arterial chemoreception. eds. P. Zapata, C. Eyzaguirre, and R. W. Torrance (New York: Plenum Press), 13–38.

van Bilsen, M., Patel, H., Bauersachs, J., Bohm, M., Borggrefe, M., Brutsaert, D., et al. (2017). The autonomic nervous system as a therapeautic target in heart failure: a scientific position statement from the Translational Research Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 1361–1378. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.921

van de Borne, P., Oren, R., Anderson, E. A., Mark, A. L., and Somers, V. K. (1996). Tonic chemoreflex activation does not contribute to elevated muscle sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Circulation 94, 1325–1328.

Keywords: carotid body, chemoreceptors, hypercapnia, hypoxia, sympathetic nervous system, ventilation

Citation: Keir DA, Duffin J and Floras JS (2020) Measuring Peripheral Chemoreflex Hypersensitivity in Heart Failure. Front. Physiol. 11:595486. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.595486

Received: 16 August 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020;

Published: 29 December 2020.

Edited by:

Alberto Giannoni, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, ItalyReviewed by:

Jerome A. Dempsey, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Keir, Duffin and Floras. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John S. Floras, am9obi5mbG9yYXNAdXRvcm9udG8uY2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.