94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol., 05 November 2020

Sec. Developmental Physiology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.592689

This article is part of the Research TopicPlacental Physiology and Placental Derived Stem Cells for Regenerative MedicineView all 5 articles

Placental insufficiency is implicated in spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) associated with intrauterine inflammation. We hypothesized that intrauterine inflammation leads to deficits in the capacity of the placenta to maintain bioenergetic and metabolic stability during pregnancy ultimately resulting in SPTB. Using a mouse model of intrauterine inflammation that leads to preterm delivery, we performed RNA-seq and metabolomics studies to assess how intrauterine inflammation alters gene expression and/or modulates metabolite production and abundance in the placenta. 1871 differentially expressed genes were identified in LPS-exposed placenta. Among them, 1,149 and 722 transcripts were increased and decreased, respectively. Ingenuity pathway analysis showed alterations in genes and canonical pathways critical for regulating oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, metabolisms of glucose and lipids, and vascular reactivity in LPS-exposed placenta. Many upstream regulators and master regulators important for nutrient-sensing and mitochondrial function were also altered in inflammation exposed placentae, including STAT1, HIF1α, mTOR, AMPK, and PPARα. Comprehensive quantification of metabolites demonstrated significant alterations in the glucose utilization, metabolisms of branched-chain amino acids, lipids, purine and pyrimidine, as well as carbon flow in TCA cycle in LPS-exposed placenta compared to control placenta. The transcriptome and metabolome were also integrated to assess the interactions of altered genes and metabolites. Collectively, significant and biologically relevant alterations in the placenta transcriptome and metabolome were identified in placentae exposed to intrauterine inflammation. Altered mitochondrial function and energy metabolism may underline the mechanisms of inflammation-induced placental dysfunction.

Preterm birth (delivery before or at 37 weeks of gestation) is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide (March of Dimes, 2015). 15 million babies are born prematurely annually resulting in an excess of 1 million deaths. It is estimated that premature births cost the American healthcare system at least $26 billion a year (Institute of Medicine, 2007). Spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) remains a significant and poorly understood perinatal complication. SPTB includes preterm spontaneous rupture of membranes, cervical weakness, and preterm labor. While the exact etiology of SPTB remains unknown, many factors may contribute, including placental dysfunction, cervical insufficiency, uterine distension, vascular disorders, and chorioamnionitis (Romero et al., 2014; Manuck et al., 2015).

Infection is detected in at least 25% of all preterm birth cases (Simmons et al., 2010; Thaxton et al., 2010). It has been reported that up to 70% of patients with extreme SPTB test positive for an infectious agent, suggesting that intrauterine infection and infection-associated inflammation play a critical role in SPTB (Watts et al., 1992; Onderdonk et al., 2008). How intrauterine infection/inflammation precisely induces parturition is unknown, however, emerging evidence supports the concept that preterm births complicated by chorioamnionitis are associated with placental insufficiency (Kourtis et al., 2014; Morgan, 2016; do Imperio et al., 2018). Therefore, elucidating underlying mechanisms for placental dysfunction may lead to a better understanding of the etiology of prematurity and the development of preventative treatment.

During pregnancy, the placenta facilitates nutrient transport and gas exchange, and supports growth and development of the fetus. It also produces and releases hormones into maternal and fetal circulation to regulate uterine function, maternal metabolisms, fetal growth and development. The placenta produces a wide variety of metabolites, and many of which are involved in energy production (Battaglia, 1992; Shekhawat et al., 2003). The placenta also protects the fetus against infections, toxins, xenobiotic molecules, and maternal diseases (Sultana et al., 2017). Therefore, a well-functioning placenta is crucial for normal gestation. We hypothesized that intrauterine inflammation leads to deficits in the capacity of the placenta to maintain bioenergetic and metabolic stability throughout the course of pregnancy ultimately resulting in SPTB.

To test this hypothesis, we assessed the transcriptome and metabolome in our well-established mouse model of intrauterine inflammation that leads to preterm delivery (Elovitz and Mrinalini, 2005). As infection that precipitates preterm birth is an acute process, the aim of our study was to identify novel pathways in the placenta that are altered in the setting of acute intrauterine inflammation that will provide insight into the underlying mechanisms driving SPTB.

The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments in this study. Details of the intrauterine inflammation model have been previously published (Elovitz and Mrinalini, 2005; Elovitz et al., 2011; Hester et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2019). CD-1 out-bred, timed pregnant mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Briefly, a mini-laparotomy was performed under isoflurane anesthesia on CD-1 timed pregnant mice at gestational day 17 (E17), with normal gestation being 19 days. The right lower uterus was exposed allowing visualization of the lower two gestational sacs. Mice then received intrauterine injections of liposaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (055:B5, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, L2880, 50 μg/100 μl phosphate buffered saline/animal) or PBS (100 μl/animal) (LPS, n = 4; PBS, n = 4) between two gestational sacs. Surgical incisions were closed using surgical staples and dams were allowed to recover for 6 h prior to placental tissue collection. LPS dose of 50 μg per animal does not result in maternal mortality and is the lowest dose that can induce preterm labor. The number of fetuses in each dam ranged from 11 to 16. Four placentas from each dam (two placentas from each side of injection point) were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen placenta of gestational day 17 pregnant animals using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen), followed by Qiagen RNeasy® Mini Columns following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity numbers greater than 7 were used for RNA-Seq Studies. Real-time q-PCR was used to determine the sex of the placenta using TaqMan probes for Xist as a positive control (Mm01232884_m1) and Sry (Mm00441712_s1) as a marker of male sex (Applied Biosystems). Four RNA-Seq libraries for each gender and experimental group were generated using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit with Ribo-Zero by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

RNA-Seq Libraries were paired-end sequenced to 100 bp on an Illumina HiSeq platform at either Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia or Next-Generation Sequencing Core at The University of Pennsylvania. RNA-seq data in.fastq files were aligned to reference mouse genome (mm10) and transcriptome using (STAR)1 (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) program. STAR was run in the 2-pass mode. The first pass mapped reads to known splice junctions in reference transcriptome during alignment while allowing for detection of novel junction sites. The second pass re-aligned reads to the reference genome and transcriptome, plus novel junction sites detected by the first pass. The alignment results were saved as indexed.bam files. Aligned reads in.bam files were loaded into R and mapped to known exons, transcripts, and genes. Read pairs uniquely mapped to the sense strand of known genes were count to obtain a gene-level read count. Read counts were converted to FPKM (fragment per kilobase per million reads) to represent gene expression level. One control sample was considered as an outlier according to the principal component analysis. This sample accounted for 39% of total variance in the control samples and had abnormally high expression of liver-specific proteins, such as albumin and apolipoproteins, suggesting a contamination with liver cells. Therefore, this sample was excluded from the analysis of differential gene expression. Differential gene expression between the LPS- and saline-treated groups was tested by the DESeq2 method. Differentially expressed genes were selected based on their fold changes, DESeq2 p-values and corresponding false discovery rate. Sequence data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE151728. Functional analysis was conducted using QIAGEN’s Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA®). Core analyses were performed on genes with FDR (q-value) < 0.05.

Primary metabolomic analysis was performed on the same placenta tissue used for RNA-Seq (n = 8 in each experimental group). Placental samples were collected, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C prior to metabolite extraction and analysis at Metabolon (Durham, NC, United States). The sample preparation process was carried out using the automated MicroLab STAR® system from Hamilton Company. The resulting extract was divided into two fractions; one for analysis by LC/MS/MS and one for analysis by GC/MS. Biochemicals were analyzed in four ways: (1) acidic positive ion conditions (water and methanol), optimized for hydrophilic compounds; (2) acidic positive ion conditions (water, methanol and acetonitrile), optimized for hydrophobic compounds; (3) basic negative ion conditions; (4) negative ionization. Samples were placed briefly on a TurboVap® (Zymark) to remove the organic solvent. Each sample was then frozen and dried under vacuum. Analytes were extracted and prepared using Metabolon’s standard solvent extraction method (DeHaven et al., 2012; Evans et al., 2014). The extracted samples were split into equal parts for analysis on complementary GC/MS (gas chromatography mass spectrometry) and LC/MS (liquid chromatography mass spectrometry) platforms.

The LC/MS portion of the platform was based on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC and a Thermo-Finnigan LTQ-FT mass spectrometer, which had a linear ion-trap (LIT) front end and a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer. For ions with signals greater than 2 million, accurate mass measurement was performed. Accurate mass measurements were made on the parent ion as well as fragments. The typical mass error was less than 5 ppm. Ions with less than two million signals required additional efforts to characterize. Fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) were typically generated, but when necessary, targeted MS/MS was employed.

The samples for GC/MS analysis were re-dried under vacuum desiccation for a minimum of 24 h prior to being derivatized under dried nitrogen using N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)-flouroacetamide (BSTFA). The GC column was 5% phenyl and the temperature ramp ranged from 40° to 300° C in a 16 min period. Samples were analyzed on a Thermo-Finnigan Trace DSQ fast-scanning single-quadrupole mass spectrometer using electron impact ionization. Compounds were identified by comparison to Metabolon library entries of purified standards or recurrent unknown entities.

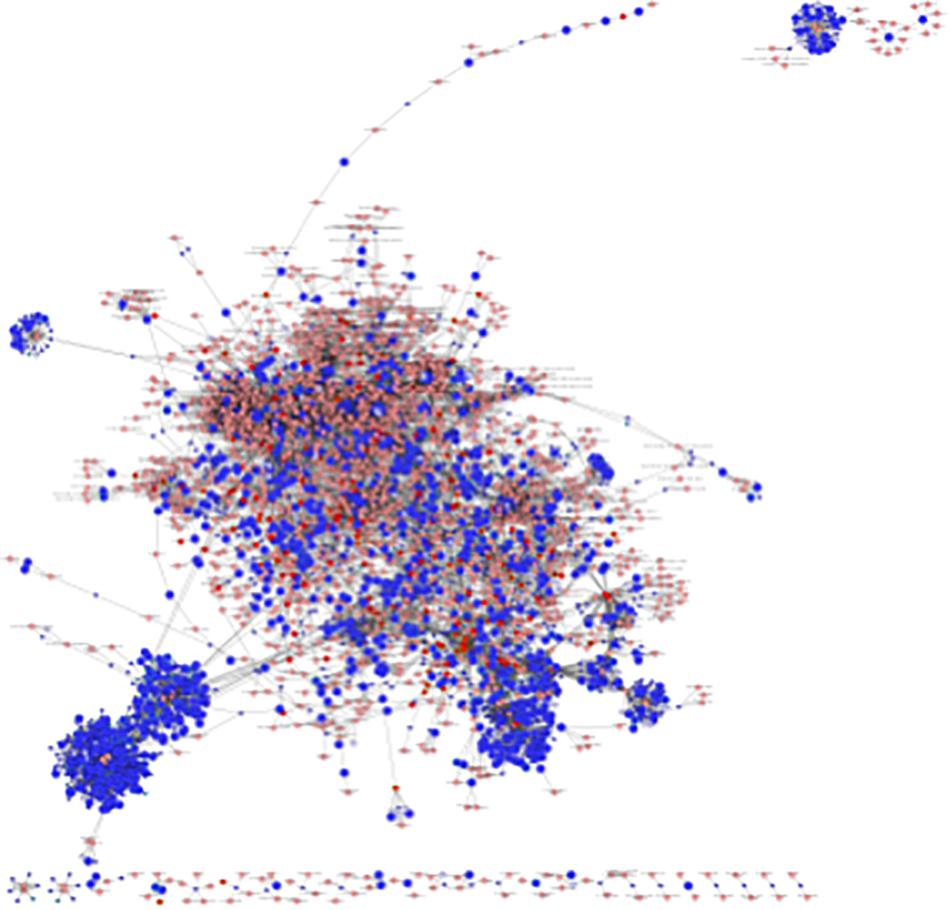

Differentially expressed genes and metabolites whose levels were significantly altered were analyzed using the MetScape3.1 (Karnovsky et al., 2012) in Cytoscape (v3.8.0). Mouse genes were mapped to their corresponding human homologs, and the interactome networks were generated based on known protein-protein and protein-metabolite interactions using human data. The metabolic pathways which were associated with protein-metabolite interactions were mapped onto each network.

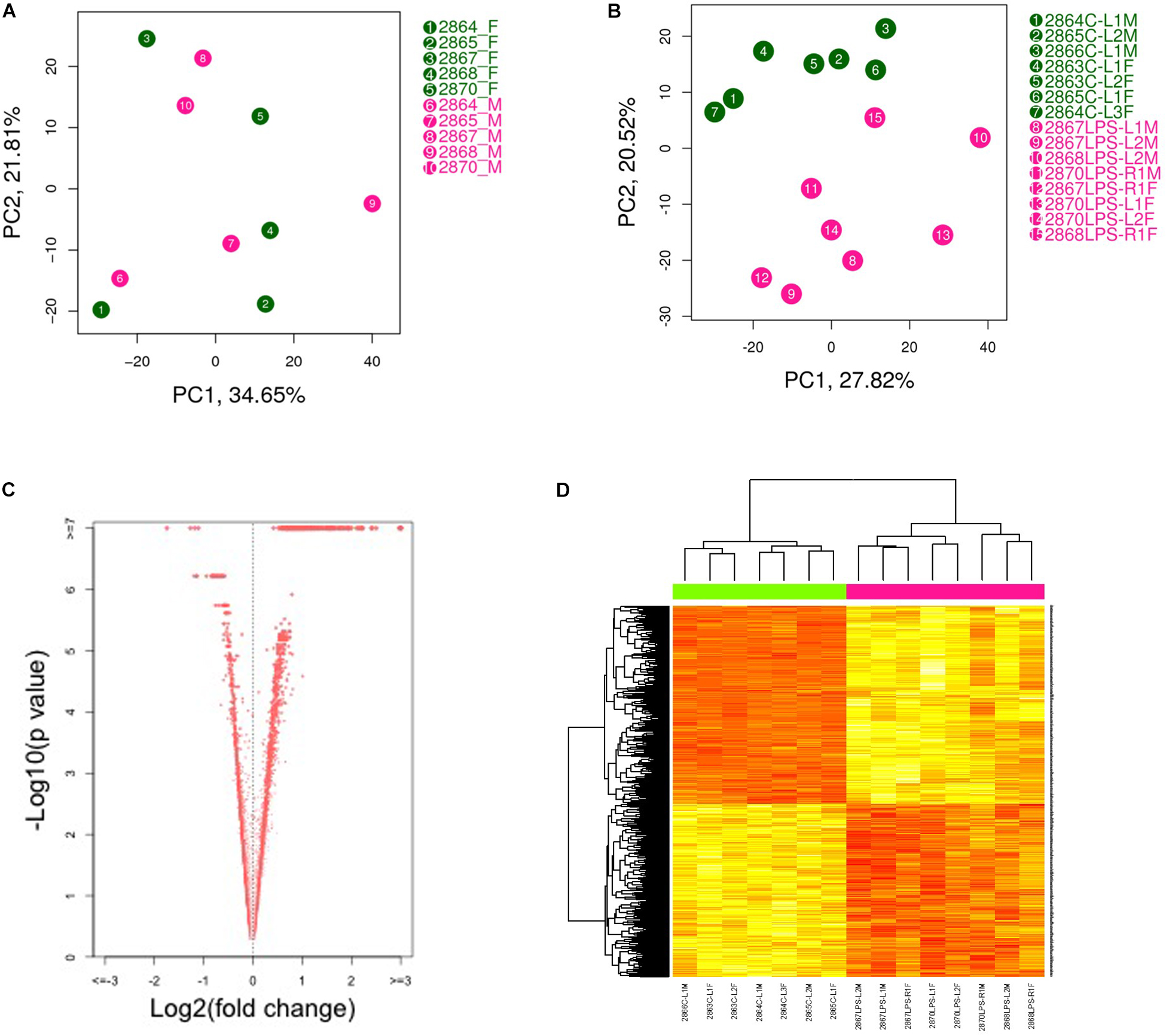

Principal component analysis (PCA) showed a strong confounding impact of treatment but not of fetal sex (Figure 1A). This suggests that LPS-induced transcriptome changes in placenta are not affected by sex hormones or sex chromosomes at this gestational age. As expected, the two treatment groups were readily distinguishable (Figure 1B). Thus, we combined the data generated from male and female placentas from the same dam for further analysis. Using an FDR (q-value) ≤ 0.05, 1871 transcripts were differentially expressed in placenta from LPS-exposed dam. Among them, 1149 transcripts were up-regulated and 722 transcripts were down-regulated (Figures 1C,D and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. Principal component analysis (PCA plot) of placental transcriptomes and differentially expressed genes. (A) PCA plots showed a strong impact of the litter but no significant differences between two genders. (B) PCA plot revealed significant separation between saline- and LPS-exposed groups. (C) Volcano plots identifying differentially expressed genes with an FDR (q-value) < 0.05. (D) Heat map of differentially expressed genes showing significant differences between saline- and LPS-exposed groups. Each row in the heat map corresponds to data point from a single gene, whereas columns correspond to individual samples. The branching dendrogram corresponds to the relationships among samples, as determined by clustering using differentially expressed genes. Up- and down-regulation of gene expressions are shown on a continuum from yellow to red, respectively. N = 7 for saline group and N = 8 for LPS group.

Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) revealed over 200 canonical pathways that were altered by intrauterine LPS treatment. As expected, many of these pathways were related to immune system changes, including: granulocyte/agranulocyte adhesion and diapedesis; communication between innate and adaptive immune cells; B cell/T-cell/dendritic cell maturation, differentiation, and activation; Th1 pathway; Th2 pathway; death receptor signaling; as well as many pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine-related signaling pathways (Supplementary Table S2). Beyond these alterations in immune system pathways that are likely to be directly due to LPS-induced intrauterine inflammation, many additional pathways were altered in LPS-exposed animals. As predicted by activation z-score, top pathways activated in LPS-exposed animals included renin-angiotensin signaling, p38 MAPK signaling, insulin resistance, retinoic acid mediated apoptosis signaling, PDGF signaling, NF-κB signaling, ceramide signaling, JAK/Stat signaling, PI3K/AKT signaling and sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling (Table 1). The top pathways inhibited in LPS-exposed animals included PPAR signaling, PPARα/RXRα activation, antioxidant action of vitamin C, PTEN signaling, and STAT3 pathway (Table 1).

Intrauterine inflammation altered multiple pathways that modulate vascular biology (Supplementary Table S3) including the renin-angiotensin signaling pathway which was highly activated (z-score = 3.77). Twenty genes comprising this pathway were differentially expressed, including Ccl2, Ccl5, Stat1, Tnf, Pik3r5, Nfkb1, and Nfkb2 (Supplementary Table S3). Other signaling pathways related to vascular function are listed in Supplementary Table S3 and include platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), P2Y purigenic receptor, sphingosine-1 phosphate, PI3K/AKT, and PTEN. PDGF is important in the pathogenesis of pregnancy-induced hypertension and is thought to regulate placenta vascular remodeling (Morita et al., 2001; Hoch and Soriano, 2003). This pathway was predicted to be activated (z-score = 2.84) in LPS-exposed placenta, and included genes such as Stat1, Eif2ak2, and Inpp5b. P2Y purigenic receptor signaling pathway, which mediates purine and pyrimidine signaling, was also activated (z-score = 2.84) (Motte et al., 1995). Genes in this pathway modulate endothelial production of vasodilator prostacyclin (PGI2) and nitric oxide (NO). P2ry2, Prkch, Myc, and Plcd3 were a few examples of genes whose expression was altered in this pathway.

In previous studies, we and others have reported that mitochondrial dysfunction and other metabolic abnormalities in the placenta are linked to SPTB in the human (Zhang et al., 2010; Crawford et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2018; Elshenawy et al., 2020). Consistent with these previous findings, IPA canonical pathway analysis revealed that intrauterine LPS treatment was associated with dysregulation of redox status/increased oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction in placenta (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S4). IPA can also predict altered downstream cellular processes and biological functions. Using this “diseases and biological functions” analysis, more than 130 genes differentially expressed in LPS-exposed animals were identified that play a role in free radical synthesis and metabolism, which were predicted to be increased in LPS-exposed placenta (p = 1.76E-28 ∼ 1.54E-14, Supplementary Table S5). IPA-Tox analysis uses “toxicity functions” in combination with “toxicity lists” to link gene expression to clinical pathology endpoints. Consistent with our canonical pathway analysis, IPA-Tox analysis further identified genes directly associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, such as Il1b, Tnf, Lcn2, Cd40, Pawr, and Timp3 (Supplementary Table S6). Expression changes in these genes have been shown to alter mitochondrial transmembrane potential, increase depolarization of mitochondria, increase damage of mitochondria, and increase oxidative stress. Finally, intrauterine inflammation appears to impair free-radical scavenging in the placenta. Vitamin C, a primary antioxidant, can quench ROS directly, and its oxidized form, dehydroascorbic acid, inhibits IKK, and NF-κB mediated signal transduction (Cárcamo et al., 2004). Interestingly, the antioxidant action of vitamin C was predicted to be inhibited in LPS-exposed animals (z-score = −3.0) which is consistent with activation of NF-κB. Txnrd1, Plcd1, and Pla2g7 were a few examples of genes whose expression was changed in this pathway (Supplementary Table S4).

Elevated levels of ROS can activate the NF-κB pathway which stimulates the innate immune response and results in production of cytokines that are detected in amniotic fluid samples preceding spontaneous preterm delivery (Zhang et al., 2010). Consistent with our findings of increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, NF-κB signaling was activated in LPS-exposed animals (z-score = 2.65). Forty-three genes comprising this pathway were differentially expressed (Supplementary Table S3). Among them, 36 genes in this pathway, including Eif2ak2, Il1b, Cd40, Il1rn, Tlr2, Tnfaip3, and Il1a were up-regulated (Supplementary Table S4).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling and PPARα/RXRα activation play a central role in regulating fatty acid oxidation and lipid/cholesterol metabolism, as well as maintain glucose and amino acid homeostasis (Zelcer and Tontonoz, 2006; Feldman et al., 2008; Tyagi et al., 2011; Hong and Tontonoz, 2014). Both pathways were both predicted to be inhibited (z-score = −3.40 and −1.50, respectively). Thirty-seven genes comprising these pathways were differentially expressed in LPS-exposed animals (Supplementary Table S7). The PPAR family of transcription factors PPARs also exert anti-oxidant effects, and are critically important to placental function (Stienstra et al., 2007; Matsuda et al., 2013). Consistent with our finding of altered PPAR signaling, fatty acid synthesis and metabolism were predicted to be increased as well. More than 180 differentially expressed genes were identified that regulate fatty acid synthesis, transport, and metabolism (p = 8.94E-25∼1.35E-18), such as Apoa1, Apoa2, Hnf4α, Lpl, and Fabp6 (Supplementary Table S5).

Additional lipid signaling pathways that were also altered including ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling which were both predicted to be activated in LPS-exposed animals (z-score = 2.18 and 1.50, respectively). A total of 29 genes comprising these pathways were differentially expressed, including Pik3r5, Pik3r1, Pik3cd, Smpd1, S1pr3, and S1pr1 (Supplementary Table S8). Ceramides can modulate mitochondrial function and oxidative phosphorylation (Kogot-Levin and Saada, 2014) and are major regulators of vascular integrity (Sattler and Levkau, 2009).

Glucose metabolism plays a fundamental role in placenta function. 293 differentially expressed genes were identified to regulate glucose metabolism (p = 3.13E-39), including Il6, Stat3, Ucp3, Nr4a1, Tgfb1, Ins2, and Irs3 (Supplementary Table S5). Many of these genes are involved in insulin signaling which was predicted to be activated (z-score = 3.30) by intrauterine inflammation in placenta. Genes that were dysregulated in this pathway include Irs3, Ins2, Socs1, Socs2, and Socs3 (Supplementary Table S8). Other insulin signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT were predicted to be activated in LPS-exposed animals (z-score = 1.53). Consistent with this finding, the inhibitor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) signaling, was inhibited (z-score = −1.89) (Supplementary Table S3). Twenty-nine genes comprising these pathways were differentially expressed, such as Nfkß1, Nfkß2, Inpp5b, Cdkn1α, and Pik3cd. These pathways regulate glucose and lipid metabolism and oxidative stress through modulating mitochondrial function (Bijur and Jope, 2003; Cheng et al., 2010; Goo et al., 2012). Via PI3K signaling, the placenta can fine-tune the supply of maternal nutrient resources to the fetus (Sferruzzi-Perri et al., 2016).

While the precise role of p38MAPK in the placenta is unclear, there are reports that activation of p38MAPK signaling is associated with premature rupture of membranes and subsequent preterm birth (Menon, 2016). This pathway was markedly altered by intrauterine inflammation and 26 genes in the p38 MAPK signaling pathway were differentially expressed leading to predicted activation by intrauterine LPS treatment (z-score = 3.40) (Supplementary Table S9). This pathway is triggered by stress stimuli such as oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, and death ligands (Cuenda and Rousseau, 2007).

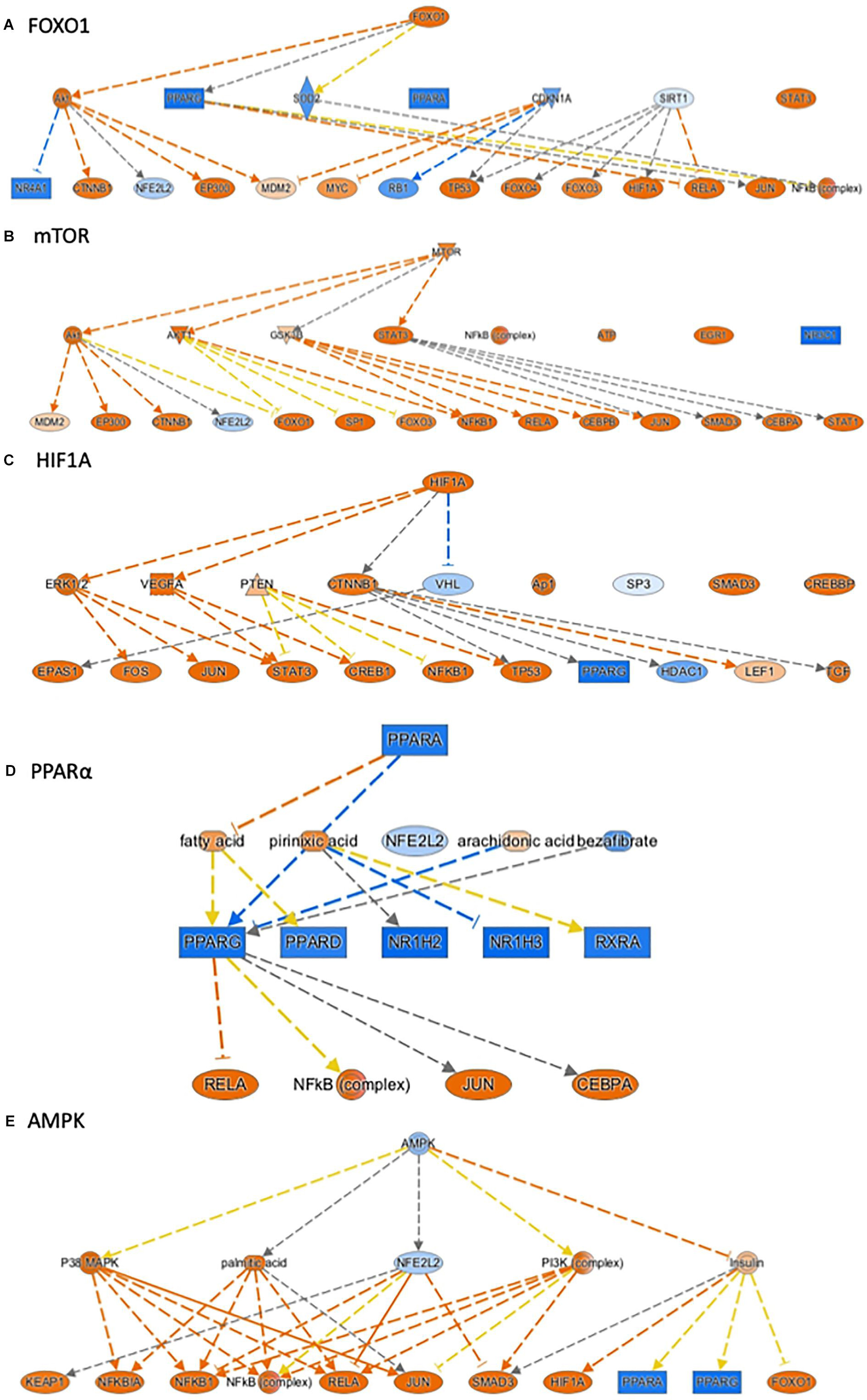

Ingenuity pathway analysis can identify upstream transcriptional regulators that can explain the changes in gene expression and biological activities. In addition to LPS and the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL1ß, and IFNγ, which may be induced in response to LPS treatment, we identified several upstream transcriptional regulators that are critical for nutrient-sensing and mitochondrial function in the placenta. The top activated upstream regulators included NFκB, STAT1, FOXO1, FOXO4, HIF1A, mTOR, the glucose sensor-GSK3, and APP (Table 2 and Figures 2A–D). STAT1 is a transcription activator and also localizes to the mitochondria and regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial encoded transcripts (Meier and Larner, 2014). FOXO1 and FOXO4 are two members of FOXO (forkhead box protein O) transcription factors and play crucial roles in regulating glucose metabolism, adipogenesis, energy homeostasis, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function (Nakae et al., 2001, 2003; Carter and Brunet, 2007; Daitoku and Fukamizu, 2007; Kim and Koh, 2017). mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) is a central coordinator of metabolism and regulates energy-sensing pathways partly through regulating mitochondrial function and AMPK activity (Tokunaga et al., 2004; Kennedy and Lamming, 2016). APP (amyloid β-precursor protein), a transmembrane glycoprotein. Interestingly, the human placenta abundantly expresses APP and APP-processing enzymes, which are up-regulated in preeclampsia (Buhimschi et al., 2014). β-Amyloid aggregates are also present in placentas of women with preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Important upstream regulators that were inhibited in placentas from LPS-exposed dams included PPARα (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha), AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), TRIM24 (tripartite motif containing 24), PTGER4 (prostaglandin E receptor 4), NKX2-3, and ACKR2 (atypical chemokine receptor 2) (Table 2 and Figure 2E). PPARα plays a major role in lipid metabolism/homeostasis regulation (Kersten et al., 1999). It also involves in embryonic and placental development and differentiation in response to nutritional stimuli (Matsuda et al., 2013). AMPK is a master metabolic regulator controlling glucose sensing and uptake, lipid metabolism, glycogen, cholesterol and protein synthesis, and induction of mitochondrial biogenesis (Winder and Hardie, 1999; Claret et al., 2007). Placental AMPK is important in regulating nutrient transport (Carey et al., 2014). AMPK also modulates acute inflammatory reactions and pro-labor mediators (Lim et al., 2015). PTGER4 is a receptor for prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a natural prostaglandin and a medicine commonly used in labor induction. PTGER4 also regulates lipid metabolism (Cai et al., 2015). Placenta is the richest source of ACKR2, which acts as a chemokine scavenger (Madigan et al., 2010). It has been shown that Ackr2 deficiency in mice leads to abnormal placenta structure, increases the incidence of stillbirth, and reduces neonatal survival (Teoh et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis® (IPA) annotated mechanistic networks regulated by critical upstream regulators. Differentially expressed genes regulated by FOXO1 (A), mTOR (B), HIF1A (C), PPARα (D), and AMPK (E). Orange-filled and blue-filled shapes indicate predicted activation and inhibition, respectively, red-filled and green-filled shapes indicate increased and decreased expression, respectively, orange-red lines indicate activation; blue lines indicate inhibition; yellow lines indicate findings inconsistent with state of downstream activity; gray lines indicate that the effect was not predicted.

The causal network analysis in IPA can expand predictions to identify potential novel master-regulators responsible for the changes in gene expression. Not surprisingly, the top hits for activated master regulators were regulators of the immune system, including toll-like receptors (TLRs), interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), interferon receptors, and interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 (IFIH1) (Supplementary Table S10). We also identified several additional interesting master regulators that were altered in LPS-exposed placenta (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) was highly activated with a z-score of 12.15. TBK1 is similar to IKB kinases and can mediate NF-κB activation (Pomerantz and Baltimore, 1999), which was consistent with our pathway analysis that NF-κB signaling was activated in LPS-exposed animals (z-score = 2.65). TBK1 modulated activities of 20 regulators, including NFκB complex, IKK complex, AKT, IRFs, JUN, and STAT1. MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein), which was predicted to be activated, is a membrane protein found in the outer mitochondrial membrane, peroxisomal membrane, and the mitochondrial associated membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (Dixit et al., 2010; Horner et al., 2011). Fifteen regulators were modulated by MAVS, including AP1, ATF2, CASP1, JNK, and NFκB complex. STIM1 was predicted as an activated master regulator (z = 9.85) and modulated 8 regulators in our dataset. STIM1 plays a crucial role in coordinating calcium signals, oxidative stress, and regulating mitochondrial shape and bioenergetics (Henke et al., 2012; Soboloff et al., 2012). Both STAT3 and STAT1 were predicted as activated master regulators. STAT3, a transcription activator, is also localized in the mitochondria and critical for the optimal activities of Complexes I and II of electron transport chain (Wegrzyn et al., 2009). STAT3 also regulates mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial permeability transition pore, ROS, and ATP production (Meier and Larner, 2014). In addition to modulating four common regulators, CASP9, ERK1/2, JUN, and MAPK, STAT3 and STAT1 modulated activities of another 18 and 16 regulators, respectively. RNF216 and TRIM21 were two master regulators predicted to be inhibited. They modulate activities of 6 and 9 regulators, respectively. RNF216 (ring finger protein 216) inhibits TNF- and IL1-induced NF-kB activation pathway, as well as functions as an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (Miah et al., 2011). TRIM21 (tripartite motif containing 21) is also an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase and negatively regulates the innate immune response (Higgs et al., 2008). Trim21 can regulate de novo lipogenesis by interacting with acetylated fatty acid synthase (FASN) and promoting FASN polyubiquitylation and destabilization (Lin et al., 2016).

Taken together, our RNA-seq data demonstrate that intrauterine inflammation causes marked abnormalities in mitochondria function, metabolism, vascular reactivity and key pathways regulating placenta development.

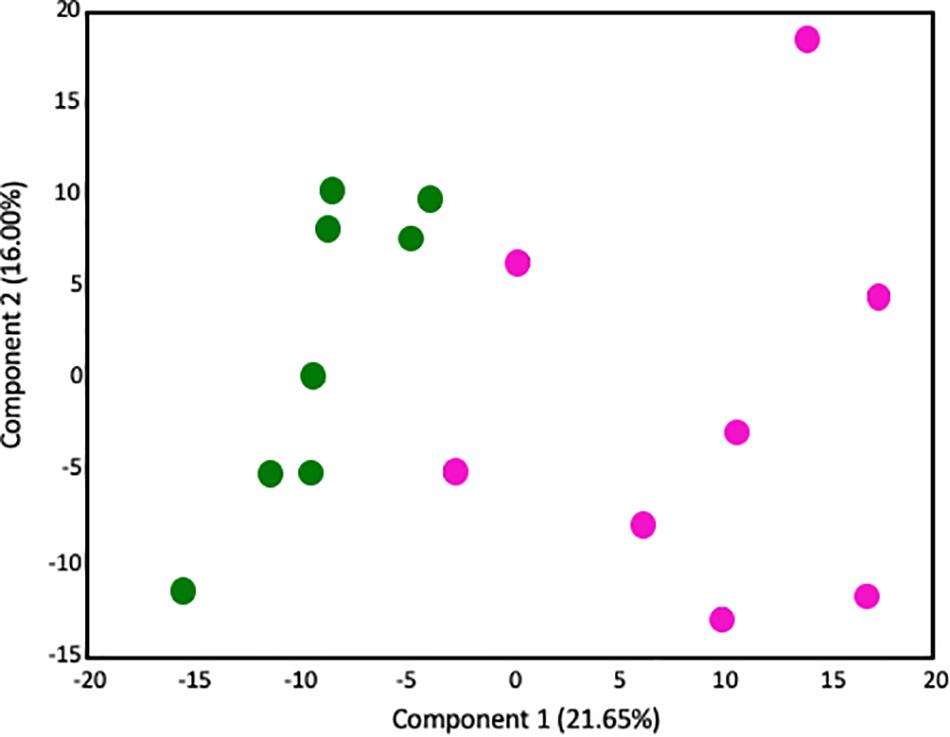

Given that our transcriptome results implicated significant changes in metabolism in the placenta, we next performed metabolic profiling in placenta to investigate whether changes in the transcriptome correlated with changes in the metabolome. There were no sex-specific effects. 547 biochemical compounds were detected in the placentas studied, of which 57 were significantly increased and 93 were significantly decreased in LPS-exposed placenta (a p-value < 0.05 and q-value < 0.1 was considered significant). Principal component analysis (PCA) identified a shift in the global metabolic profile in LPS placenta, indicating that the two groups were strongly distinguishable (Figure 3). Unbiased and supervised classification analysis using Random Forest (RF) analysis demonstrated that the placental metabolome differentiated the control and LPS groups with an overall predictive accuracy of 87%, indicating the pronounced differences in biochemical profiles between groups (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3. Principal components analysis demonstrates that the global metabolome from LPS-exposed placenta samples is overall distinguishable from the metabolome of control placenta samples. Control placentas: green circles (N = 8); LPS-exposed placenta: pink circles (N = 8). The X-axis (Comp1) represents 21.65% of the variability between samples and the Y-axis (Comp 2) represents 16.00% of the variability between samples.

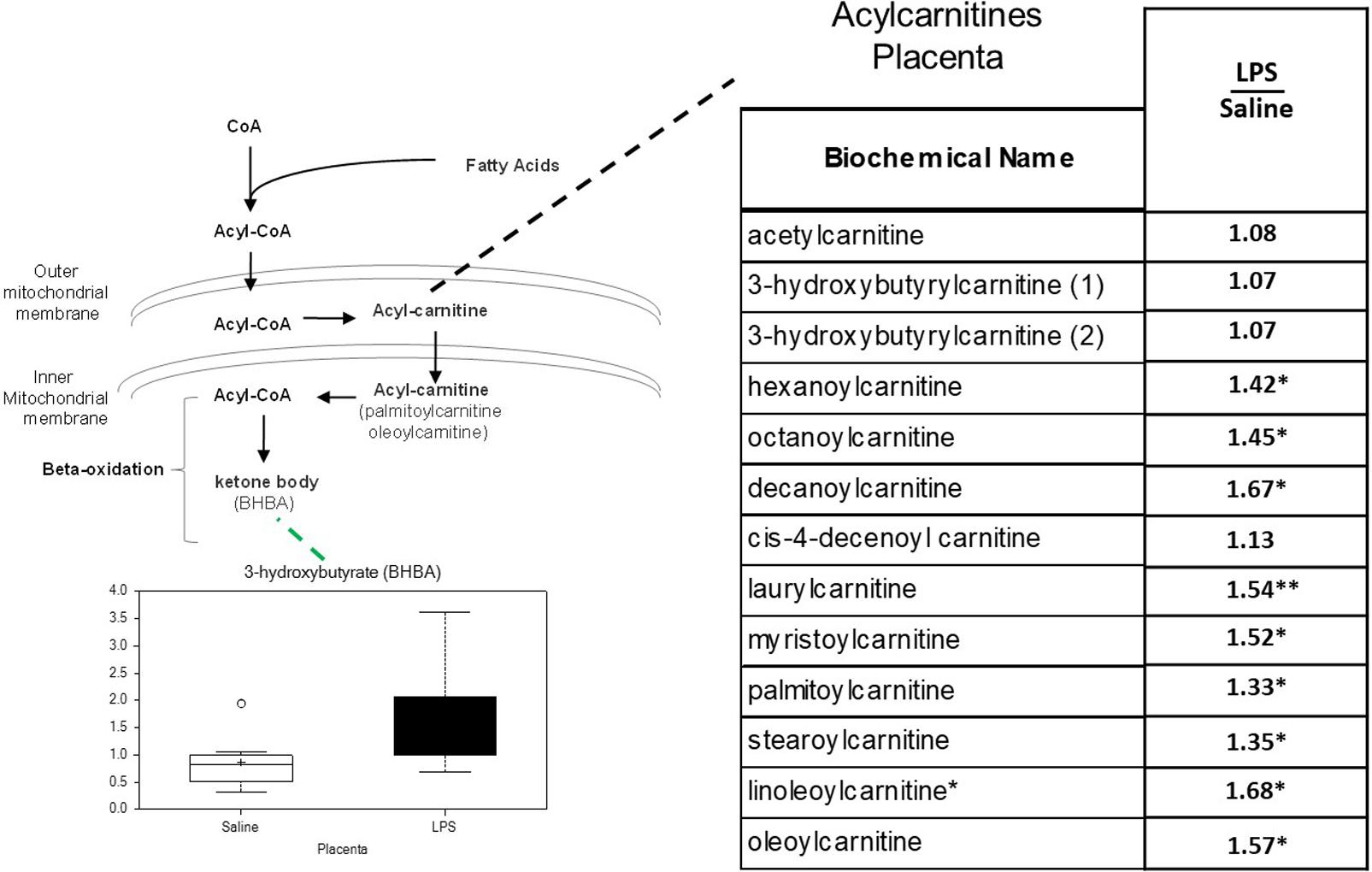

In previous studies of human placenta from SPTB pregnancies we noted marked abnormalities in lipid metabolites, in particular acyl-carnitines, compared to placenta from term pregnancies (Elshenawy et al., 2020). Similarly, significant increases were observed in several long-chain acylcarnitines in LPS placentas. Of the 14 acylcarnitines detected, 9 were significantly elevated, and none were decreased (p < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Acylcarnitine metabolism is disrupted in LPS Placenta. Relative values of differentially expressed metabolites in LPS placenta expressed as fold change of controls. ∗Significantly different between LPS and control placenta, p ≤ 0.05 and q ≤ 0.05. ∗∗Significantly different between LPS and control placenta, p ≤ 0.05 and q ≤ 0.1. Box plots of 3-hydroxybutryate in LPS (black boxes) and control (white boxes). N = 8 both groups.

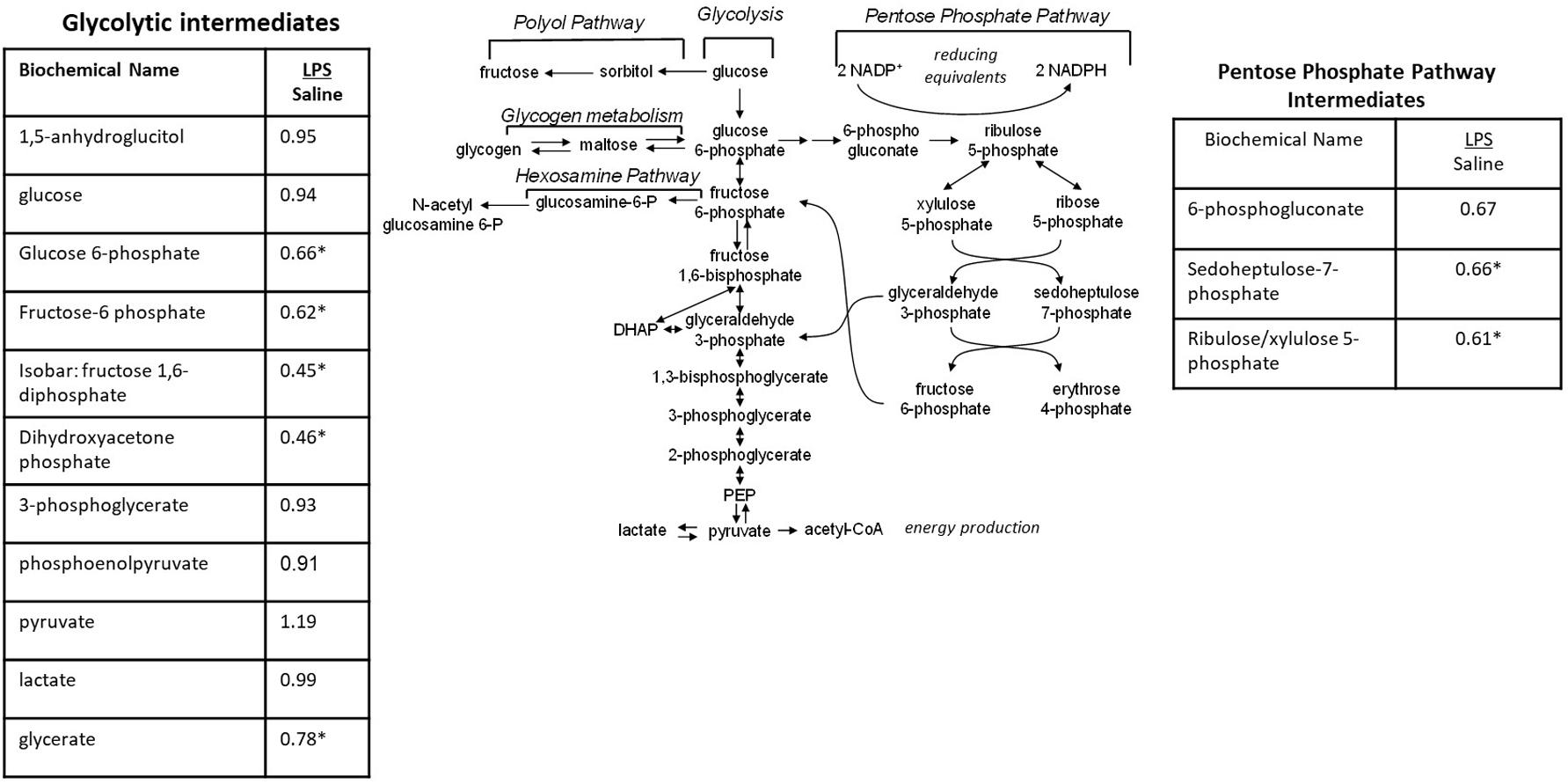

When the metabolic profiles of the LPS- and Saline-treated groups were compared, significant alterations were observed in several glucose-derived metabolites. As shown in Figure 5, the LPS-exposed animals exhibited significantly lower levels of metabolites involved in the glycolytic, pentose phosphate, and glycogen synthesis/degradation pathways. The affected pathways converge at glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) within the cell. G6P functions as an early stage component in the glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathways; it is also consumed and generated, respectively, when glycogen is synthesized and degraded.

Figure 5. Alterations in Glucose Utilization in LPS Placenta. Relative values of differentially expressed metabolites in LPS placenta expressed as fold change of controls. ∗Significantly different between LPS and control placenta, p ≤ 0.05 and q ≤ 0.05. N = 8 both groups.

Significant increases were observed in several metabolites involved in branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) metabolism in placenta of LPS pregnant mice. As shown in Table 4, branched-chain keto acids and hydroxycarboxcylic acids (2-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate, 3-hydroxyisobutyrate, 3-hydroxyisobutyrate, and alpha-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate) were particularly elevated. These changes are consistent with alterations in the BCAA catabolic pathway.

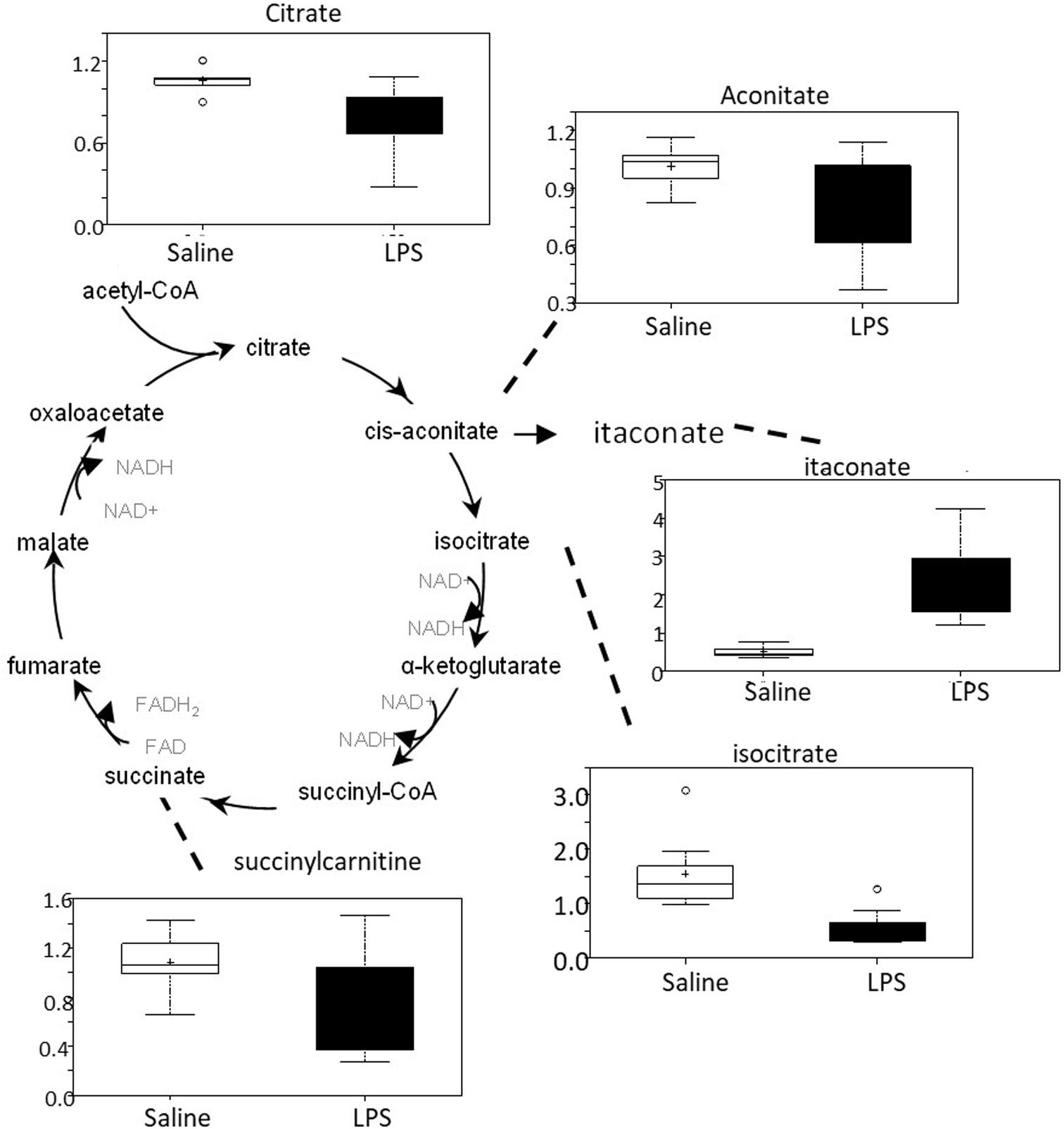

There was an overall decrease in several TCA cycle intermediates in LPS placenta compared to controls (citrate, aconitate, isocitrate, and succinylcarnitine) (Figure 6). These changes are consistent with alterations in carbon flow through the TCA cycle. It appears that the LPS-exposed mice shunted carbon flow in the cycle toward itaconate (methylenesuccinate) production. As shown in Figure 6, itaconate can be derived from the TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate. Itaconate inhibits isocitrate lyase, a key enzyme of the glyoxylate cycle (facilitates the conversion of acetyl-CoA to succinate). Itaconate can also inhibit glycolysis by inhibiting the formation of fructose 2,6 phosphate (which activates the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase 1).

Figure 6. TCA cycle activity is abnormal in LPS placenta. Box plots of TCA cycle metabolites in LPS (black boxes) and control (white boxes). N = 8 both groups.

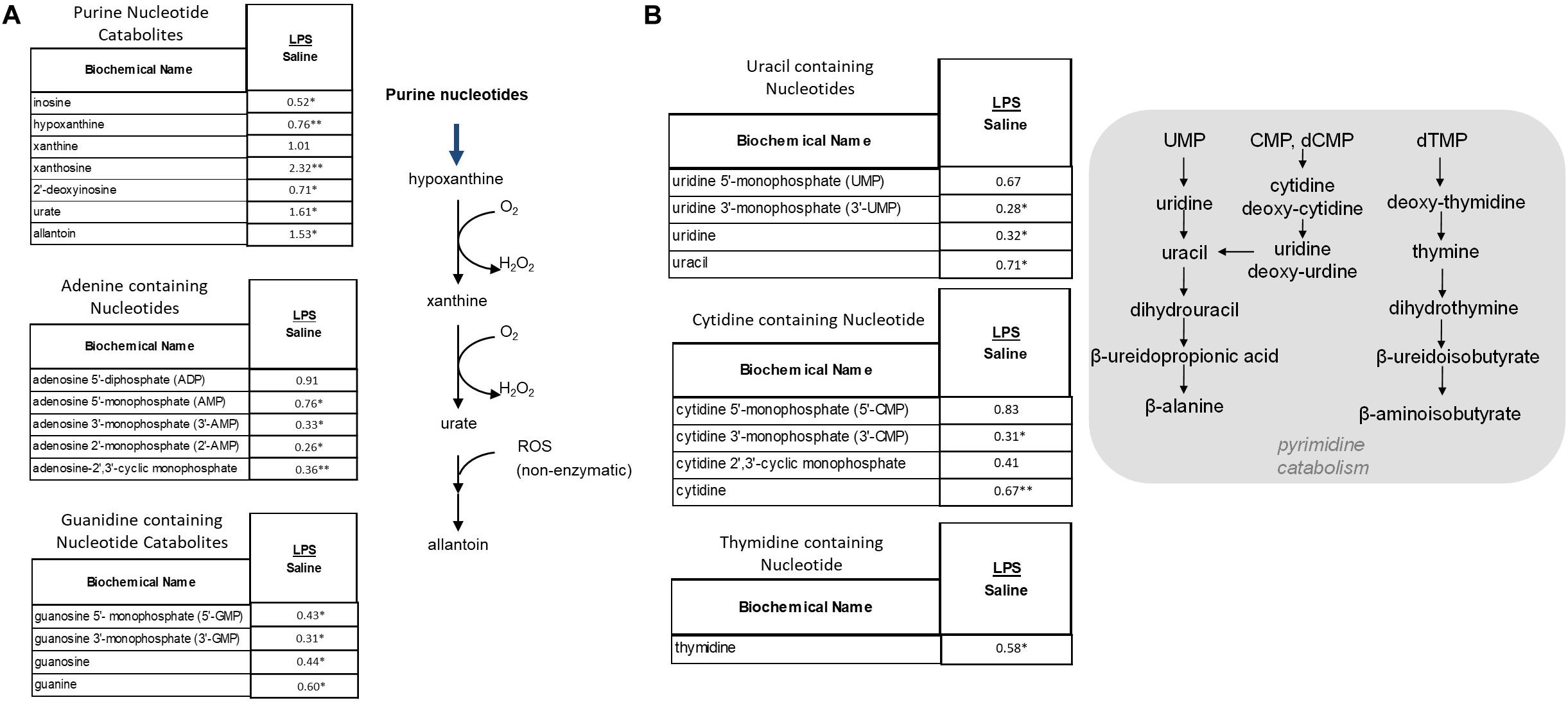

As shown Figure 7A, these metabolic pathways showed a shift toward increased purine breakdown. Large increases were observed in hypoxanthine, xanthine, and urate (Figure 7A). LPS placentas also exhibited large decreases in adenosine and guanidine containing nucleotides. Pyrimidine catabolites trended toward lower levels in placental tissues (Figure 7B). In addition to alterations in DNA and RNA turnover in placenta, it should also be noted that these changes may correlate in part with changes in energy homeostasis as certain nucleotides (e.g., ATP) play important roles in energy metabolism.

Figure 7. Alterations in Purine (A) and Pyrimidine (B) Metabolism in LPS Placenta. Relative values of differentially expressed metabolites in LPS placenta expressed as fold change of controls. ∗Significantly different between LPS and control placenta, p ≤ 0.05 and q ≤ 0.05. ∗∗Significantly different between LPS and control placenta, p ≤ 0.05 and q ≤ 0.1. N = 8 both groups.

LPS-exposed mice exhibited significant increases in corticosterone (1.76-fold increase over saline, q < 0.005) and 11-dehydrocorticosterone (2.34-fold increase over saline, q < 0.005) in placental. These changes are consistent with increased corticosterone production. Corticosterone, the principal glucocorticoid produced in mice, is involved in mediating energy regulation, immune reactions, and stress responses.

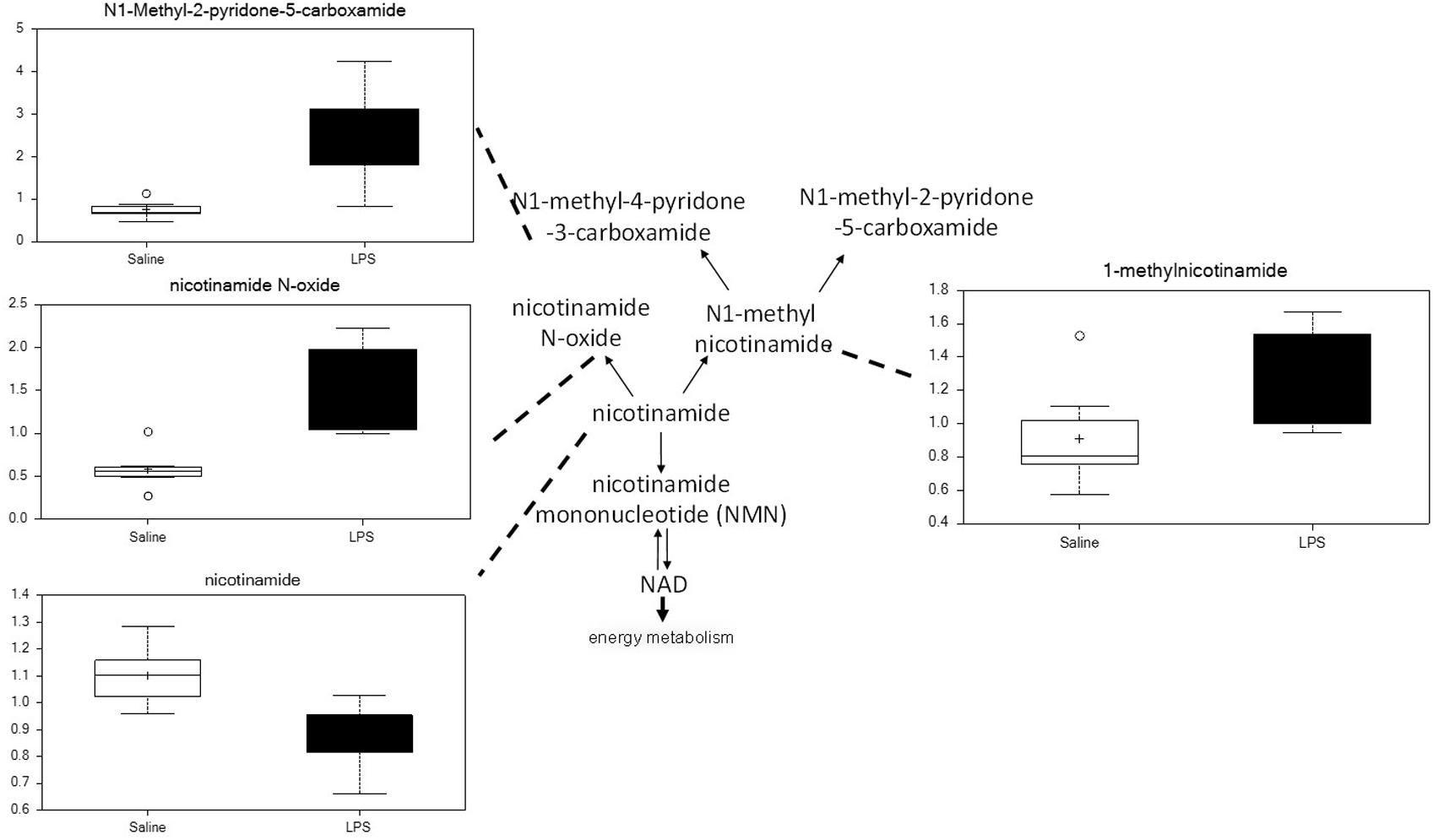

Placenta from LPS-exposed mice exhibited significant increases in several metabolites that are derived from nicotinamide. As shown in Figure 8, placenta of these animals contained higher levels of nicotinamide, nicotinamide N-oxide, 1-methylnicotinamide, and N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxyamide. These changes are consistent with increases in nicotinamide catabolism and likely correlate with the changes in energy metabolism discussed above.

Figure 8. Maternal LPS increases nicotinamide degradation in placenta. Box plots of nicotinamide metabolites in LPS (black boxes) and control (white boxes). N = 8 both groups.

Choline and several choline-derived metabolites in this study were markedly altered in LPS placenta (Table 5). Choline was significantly elevated, whereas cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine and glycerophosphorylcholine (intermediates in phosphatidylcholine synthesis and degradation) were lower in LPS placenta.

An interactome network model (Figure 9) integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic was generated which connected pathways via protein-protein or protein-metabolite interactions. Analysis of this interactome network demonstrated that several critical metabolic processes were altered in LPS-exposed placenta. Not surprisingly, these modules included processes associated with glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle, amino acid metabolism, purine, and pyrimidine metabolism, phosphatidylinositol phosphate metabolism, glycosphingolipid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism (Table 6). The differentially expressed genes and significantly changed metabolites associated within these modules in our datasets are listed in Table 6.

Figure 9. Visual representation of the interactome model. Interaction network of integrated transcriptome and metabolome was analyzed using MetScape 3.1. Dark blue squares represent differentially expressed genes in the placenta dataset; light blue squares represent inferred gene interactions; dark red squares represent significantly changed metabolites in the placenta dataset; light red squares represent inferred metabolite interactions; gray lines represent protein-protein or protein-metabolite interactions.

Using a model of intrauterine inflammation that is similar to human pregnancies complicated by acute chorioamnionitis (Elovitz and Mrinalini, 2005; Elovitz et al., 2011; Hester et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2019), we demonstrated that intrauterine LPS injection alters the placenta metabolome and is associated with marked changes in expression of genes involved in key pathways including vascular function and reactivity, mitochondria function and nutrient sensing, glucose and lipid metabolism, and ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling.

One of the more surprising findings in our study was the alteration of a large number of genes and pathways that regulate vascular function and reactivity including renin-angiotensin signaling (RAS) in placenta exposed to intrauterine inflammation. RAS was one of the most significantly activated pathways in LPS-exposed placenta. Renin-angiotensin signaling regulates systemic blood volume and maternal-fetal blood flow during pregnancy, and has multiple effects in vascular remodeling and reactivity. During pregnancy, estrogen up-regulates renin and angiotensinogen levels leading to increased activity for both systemic and local uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (Anton and Brosnihan, 2008; Clark et al., 2017). RAS activity is significantly higher in pre-eclamptic placentas (Singh et al., 2004), which is associated with hypertension, reduced maternal-fetal blood flow, limited nutrient and oxygen supply to the fetus, as well as intrauterine growth restriction (Clark et al., 2017). Furthermore, angiotensin II can directly decrease amino acid transporter activities in human placenta (Shibata et al., 2006). Thus, increased renin-angiotensin signaling activity may play a critical role in acute intrauterine inflammation-induced alterations of metabolic processes and poor fetal outcomes.

A number of other pathways regulating vascular function were also significantly altered in LPS placenta including sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and the PI3K/AKT/PTEN signaling pathway. Spingosine-1-phosphate signaling controls vascular tone, permeability, and modulation of α1-adrenergic induced vasoactivity (Hla, 2003; Maceyka et al., 2012). The major components of the PI3K/AKT/PTEN signaling pathway are abundantly expressed in placenta and among their myriad functions they also regulate vascular function, including vascular tone, angiogenesis, and control of adhesion in the placenta (Yang et al., 2003; Hamada et al., 2005; Jiang and Liu, 2009). Taken together, our finding that multiple pathways regulating vascular biology were markedly altered in LPS exposed placenta suggests that one of the major complications of intrauterine inflammation is the disruption of vascular tone and reactivity in the placenta which can have profound implications for placenta function and fetal outcomes.

Another key finding was altered acylcarnitine metabolism in LPS placenta. This is very similar to our observations in human placentas from SPTB suggesting that these lipid species play a fundamental role in placental failure associated with inflammation and preterm birth. Acylcarnitines are intermediate oxidative metabolites. They consist of a carnitine moiety that facilitates its transport across the mitochondrial membrane for β-oxidation (Batchuluun et al., 2018). In general, acylcarnitines transport long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria and generate acetyl CoA and ATP. High levels are secondary to either altered fatty acid transport and/or oxidation rates. Our finding of increased levels of 3-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) in the placenta suggests that impaired fatty oxidation rates are responsible for increased acylcarnitines in LPS placenta. BHBA is a ketone body that typically increases in concentration during ketogenic conditions and decreased β-oxidation. Indeed, in our previous studies of SPTB placenta, fatty acid oxidation rates were markedly decreased (Elshenawy et al., 2020). However, the direct function of acylcarnities in the placenta has not been well characterized. Human placenta expresses high levels of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation (Shekhawat et al., 2003). Acylcarnitines are thought to activate proinflammatory signaling, engage pattern recognition receptor (PRR)-associated pathways, and induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 leading to uncontrolled inflammation (Rutkowsky et al., 2014). Acylcarnitines can also induce mitochondrial dysfunction (Batchuluun et al., 2018). This ongoing oxidative stress and inflammation may ultimately lead to severe placental dysfunction and disruption of fetal membranes, resulting in preterm birth. Furthermore, elevated levels of free carnitine and several short-chain, medium-chain, and long-chain acylcarnitines in the circulation have been observed in adverse pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, both of which are associated with placental dysfunction (Koster et al., 2015; Batchuluun et al., 2018).

We identified multiple additional metabolic pathways that were altered in the placenta from dams exposed to intrauterine inflammation indicating that intrauterine inflammation has broad adverse effects on placenta metabolism. Placenta from dams exposed to intrauterine inflammation exhibited significant alterations in the availability and utilization of several energy sources including glucose, branched-chain amino acids, and fatty acids. These changes were accompanied by alterations in TCA cycle intermediates, nucleotide metabolites, oxidized lipids, and steroid metabolites. Notable changes were also apparent in nicotinamide catabolites, choline metabolites, and dipeptides. Localized intrauterine inflammation appeared therefore to have major impacts on both the transfer and utilization of metabolites in the intrauterine space. Metabolites that were altered in each class may play a role in placental dysfunction through energy failure, inflammation, early senescence, and maternal-fetal intolerance.

An additional important finding was the marked changes in branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism in LPS placenta. BCAA catabolism is mediated by two major enzymes: (1) branched-chain aminotransferase (BCAT) and (2) branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKD). BCAT is responsible for converting BCAAs to branched-chain keto acids (BCKAs) and BCKD is responsible for converting BCKAs to branched-chain acyl-CoA intermediates. The latter may be conjugated to carnitine and subsequently metabolized to either propionyl-CoA or acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria. When alterations are present in this pathway, however, branched-chain keto acids may accumulate and/or be converted to 2-hydroxycarboxylic acids (as observed in this study). The accumulation of these metabolites in this study therefore, suggest that intrauterine inflammation alters BCAA breakdown.

There was significant overlap between the transcriptome and metabolomic data. Both data sets showed abnormalities in mitochondrial function, nutrient sensing, and glucose and lipid metabolism in the placenta from dams exposed to intrauterine inflammation. Similarly, the metabolomics data showed significant alterations of many glucose-derived metabolites and lipid metabolites especially long-chain acylcarnitines, suggesting the dysregulation of glucose utilization and lipid metabolism in LPS placenta. Increased acylcarnitines in LPS placenta may further exacerbate inflammation, induce mitochondrial dysfunction, and increase oxidative stress, all of which were observed in transcriptome data by IPA analysis. Acylcarnitines can cause uncontrolled inflammation via up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (Rutkowsky et al., 2014). Indeed, the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (Ptgs2) was increased in LPS placenta. It was also predicted as an activated upstream regulator by IPA analysis. TCA cycle intermediates were altered in LPS-exposed mice. The formation of itaconate, a derivative from TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate by immunoresponsive gene 1 (Irg1), a gene that is highly expressed during infections (Michelucci et al., 2013), was significantly increased in LPS placenta. Consistent with increased itaconate, the expression of Irg1 was increased 10-fold in LPS placenta. Accumulation of purine and pyrimidine catabolites were also found in LPS-exposed mice in our metabolomics studies, which was supported by the alteration of pathways regulating pyrimidine ribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis and interconversion in the transcriptome data. Furthermore, the P2Y purigenic receptor signaling pathway that mediates purines and pyrimidines signaling was activated in LPS placenta.

Integrated interactome model provides greater confidence of the signaling and pathways identified in the transcriptome and metabolome individually. Consistent with our previous findings in human SPTB placenta, alteration of lipid metabolism in LPS-exposed placentas was identified in all three analyses of transcriptome, metabolome, and interactome, which further supports that aberrant fatty acid metabolism in the placenta is highly associated with preterm birth. In addition to the changes in glucose utilization and BCAA catabolism identified in metabolome, interactome model showed that metabolism for almost all amino acids were altered in LPS-exposed placentas. Collectively, acute intrauterine inflammation leads to alterations and/or deficits in the metabolism of glucose, amino acids, lipids, purine, and pyrimidine in placenta.

A well-functioning placenta plays a crucial role in normal pregnancy. Our current study has identified alterations in novel pathways and upstream regulators that may play an important role in the maintenance of normal bioenergetic metabolism. Results from our current study in the acute intrauterine inflammation mouse model have many similarities with results from our previous metabolomics study in human placentas from SPTB (Elshenawy et al., 2020). Since inflammation is one of the major causes of SPTB in human, our findings provide new insights into the underlying mechanisms of SPTB.

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI GEO accession GSE151728.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Y-CL and RS: conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, and project administration. Y-CL, GB, AG, and ME: methodology. Y-CL: validation. ZZ: formal analysis. Y-CL, ZZ, and RS: data curation. RS: supervision, writing - review and editing. RS and ME: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania (RS and ME).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.592689/full#supplementary-material

Anton, L., and Brosnihan, K. B. (2008). Systemic and uteroplacental renin–angiotensin system in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2, 349–362. doi: 10.1177/1753944708094529

Batchuluun, B., Al Rijjal, D., Prentice, K. J., Eversley, J. A., Burdett, E., Mohan, H., et al. (2018). Elevated medium-chain acylcarnitines are associated with gestational diabetes mellitus and early progression to Type 2 diabetes and induce pancreatic beta-Cell dysfunction. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 67, 885–897. doi: 10.2337/db17-1150

Battaglia, F. C. (1992). New concepts in fetal and placental amino acid metabolism. J. Anim. Sci. 70, 3258–3263. doi: 10.2527/1992.70103258x

Bijur, G. N., and Jope, R. S. (2003). Rapid accumulation of Akt in mitochondria following phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. J. Neurochem. 87, 1427–1435. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02113.x

Brown, A. G., Maubert, M. E., Anton, L., Heiser, L. M., and Elovitz, M. A. (2019). The tracking of lipopolysaccharide through the feto-maternal compartment and the involvement of maternal TLR4 in inflammation-induced fetal brain injury. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 82:e13189. doi: 10.1111/aji.13189

Buhimschi, I. A., Nayeri, U. A., Zhao, G., Shook, L. L., Pensalfini, A., Funai, E. F., et al. (2014). Protein misfolding, congophilia, oligomerization, and defective amyloid processing in preeclampsia. Sci. Transl. Med. 6:245ra292. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008808

Cai, Y., Ying, F., Song, E., Wang, Y., Xu, A., Vanhoutte, P. M., et al. (2015). Mice lacking prostaglandin E receptor subtype 4 manifest disrupted lipid metabolism attributable to impaired triglyceride clearance. FASEB J. 29, 4924–4936. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-274597

Cárcamo, J. M., Pedraza, A., Bórquez-Ojeda, O., Zhang, B., Sanchez, R., and Golde, D. W. (2004). Vitamin C is a kinase inhibitor: dehydroascorbic acid inhibits IkappaBalpha kinase beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6645–6652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6645-6652.2004

Carey, E. A., Albers, R. E., Doliboa, S. R., Hughes, M., Wyatt, C. N., Natale, D. R., et al. (2014). AMPK knockdown in placental trophoblast cells results in altered morphology and function. Stem Cells Dev. 23, 2921–2930. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0092

Carter, M. E., and Brunet, A. (2007). FOXO transcription factors. Curr. Biol. 17, R113–R114. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.008

Cheng, Z., Tseng, Y., and White, M. F. (2010). Insulin signaling meets mitochondria in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.06.005

Claret, M., Smith, M. A., Batterham, R. L., Selman, C., Choudhury, A. I., Fryer, L. G., et al. (2007). AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2325–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI31516

Clark, N. C., Pru, C. A., and Pru, J. K. (2017). Novel regulators of hemodynamics in the pregnant uterus. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 145, 181–216. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.12.007

Crawford, N., Prendergast, D., Oehlert, J. W., Shaw, G. M., Stevenson, D. K., Rappaport, N., et al. (2018). Divergent patterns of mitochondrial and nuclear ancestry are associated with the risk for preterm birth. J. Pediatr. 194, 40–46.e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.052

Cuenda, A., and Rousseau, S. (2007). p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 1358–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.010

Daitoku, H., and Fukamizu, A. (2007). FOXO transcription factors in the regulatory networks of longevity. J. Biochem. 141, 769–774. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm104

DeHaven, C. D., Evans, A. M., Dai, H., and Lawton, K. A. (2012). “Software techniques for enabling high-throughput analysis of metabolomic datasets,” in Metabolomics, ed. U. Roessner (London: IntechOpen).

Dixit, E., Boulant, S., Zhang, Y., Lee, A. S., Odendall, C., Shum, B., et al. (2010). Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 141, 668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.018

do Imperio, G. E., Bloise, E., Javam, M., Lye, P., Constantinof, A., Dunk, C., et al. (2018). Chorioamnionitis induces a specific signature of placental ABC transporters associated with an increase of miR-331-5p in the human preterm placenta. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 45, 591–604. doi: 10.1159/000487100

Elovitz, M. A., Brown, A. G., Breen, K., Anton, L., Maubert, M., and Burd, I. (2011). Intrauterine inflammation, insufficient to induce parturition, still evokes fetal and neonatal brain injury. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 29, 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.02.011

Elovitz, M. A., and Mrinalini, C. (2005). Can medroxyprogesterone acetate alter Toll-like receptor expression in a mouse model of intrauterine inflammation? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 193(3 Pt 2), 1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.043

Elshenawy, S., Pinney, S. E., Stuart, T., Doulias, P. T., Zura, G., Parry, S., et al. (2020). The metabolomic signature of the placenta in spontaneous preterm birth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 197–205. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031043

Evans, A. M., Bridgewater, B., Liu, Q., Mitchell, M. W., Robinson, R. J., Dai, H., et al. (2014). High resolution mass spectrometry improves data quantity and quality as compared to unit mass resolution mass spectrometry in high throughput profiling metabolomics. Metabolomics 4:132. doi: 10.4172/2153-0769.1000132

Feldman, P. L., Lambert, M. H., and Henke, B. R. (2008). PPAR modulators and PPAR pan agonists for metabolic diseases: the next generation of drugs targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors? Curr. Top Med. Chem. 8, 728–749. doi: 10.2174/156802608784535084

Goo, C. K., Lim, H. Y., Ho, Q. S., Too, H. P., Clement, M. V., and Wong, K. P. (2012). PTEN/Akt signaling controls mitochondrial respiratory capacity through 4E-BP1. PLoS One 7:e45806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045806

Hamada, K., Sasaki, T., Koni, P. A., Natsui, M., Kishimoto, H., Sasaki, J., et al. (2005). The PTEN/PI3K pathway governs normal vascular development and tumor angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 19, 2054–2065. doi: 10.1101/gad.1308805

Henke, N., Albrecht, P., Pfeiffer, A., Toutzaris, D., Zanger, K., and Methner, A. (2012). Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial shape and bioenergetics and plays a role in oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42042–42052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417212

Hester, M. S., Tulina, N., Brown, A., Barila, G., and Elovitz, M. A. (2018). Intrauterine inflammation reduces postnatal neurogenesis in the hippocampal subgranular zone and leads to accumulation of hilar ectopic granule cells. Brain Res. 1685, 51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.02.005

Higgs, R., Ní Gabhann, J., Ben Larbi, N., Breen, E. P., Fitzgerald, K. A., and Jefferies, C. A. (2008). The E3 ubiquitin ligase Ro52 negatively regulates IFN-beta production post-pathogen recognition by polyubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRF3. J. Immunol. 181, 1780–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1780

Hla, T. (2003). Signaling and biological actions of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Pharmacol. Res. 47, 401–407. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00046-x

Hoch, R. V., and Soriano, P. (2003). Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development 130, 4769–4784. doi: 10.1242/dev.00721

Hong, C., and Tontonoz, P. (2014). Liver X receptors in lipid metabolism: opportunities for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 433–444. doi: 10.1038/nrd4280

Horner, S. M., Liu, H. M., Park, H. S., Briley, J., and Gale, M. (2011). Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14590–14595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110133108

Institute of Medicine (2007). “Chapter 12: societal costs of preterm birth,” in Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention, eds R. E. Behrman and A. S. Butler (Washington, DC: National Academies Press).

Jiang, B. H., and Liu, L. Z. (2009). PI3K/PTEN signaling in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Adv. Cancer Res. 102, 19–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02002-8

Karnovsky, A., Weymouth, T., Hull, T., Tarcea, V. G., Scardoni, G., Laudanna, C., et al. (2012). Metscape 2 bioinformatics tool for the analysis and visualization of metabolomics and gene expression data. Bioinformatics 28, 373–380. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr661

Kennedy, B. K., and Lamming, D. W. (2016). The mechanistic target of rapamycin: the grand conductor of metabolism and aging. Cell Metab. 23, 990–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009

Kersten, S., Seydoux, J., Peters, J. M., Gonzalez, F. J., Desvergne, B., Wahli, W. et al. (1999). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1489–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI6223

Kim, S., and Koh, H. (2017). Role of FOXO transcription factors in crosstalk between mitochondria and the nucleus. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 49, 335–341. doi: 10.1007/s10863-017-9705-0

Kogot-Levin, A., and Saada, A. (2014). Ceramide and the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochimie 100, 88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.027

Koster, M. P., Vreeken, R. J., Harms, A. C., Dane, A. D., Kuc, S., Schielen, P. C., et al. (2015). First-trimester serum acylcarnitine levels to predict preeclampsia: a metabolomics approach. Dis. Markers 2015:857108. doi: 10.1155/2015/857108

Kourtis, A. P., Read, J. S., and Jamieson, D. J. (2014). Pregnancy and infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 371:1077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1408436

Lim, R., Barker, G., and Lappas, M. (2015). Activation of AMPK in human fetal membranes alleviates infection-induced expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-labour mediators. Placenta 36, 454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.01.007

Lin, H. P., Cheng, Z. L., He, R. Y., Song, L., Tian, M. X., Zhou, L. S., et al. (2016). Destabilization of fatty acid synthase by acetylation inhibits de novo lipogenesis and tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 76, 6924–6936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1597

Maceyka, M., Harikumar, K. B., Milstien, S., and Spiegel, S. (2012). Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and its role in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.003

Madigan, J., Freeman, D. J., Menzies, F., Forrow, S., Nelson, S. M., Young, A., et al. (2010). Chemokine scavenger D6 is expressed by trophoblasts and aids the survival of mouse embryos transferred into allogeneic recipients. J. Immunol. 184, 3202–3212. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902118

Manuck, T. A., Esplin, M. S., Biggio, J., Bukowski, R., Parry, S., Zhang, H., et al. (2015). The phenotype of spontaneous preterm birth: application of a clinical phenotyping tool. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212, 487 e481–487 e411. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.010

March of Dimes (2015). Mission Statement. Available online at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/mission.aspx (accessed October 27, 2015).

Martin, A., Faes, C., Debevec, T., Rytz, C., Millet, G., and Pialoux, V. (2018). Preterm birth and oxidative stress: effects of acute physical exercise and hypoxia physiological responses. Redox Biol. 17, 315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.04.022

Matsuda, S., Kobayashi, M., and Kitagishi, Y. (2013). Expression and function of PPARs in placenta. PPAR Res. 2013:256508. doi: 10.1155/2013/256508

Meier, J. A., and Larner, A. C. (2014). Toward a new STATe: the role of STATs in mitochondrial function. Semin. Immunol. 26, 20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.12.005

Menon, R. (2016). Human fetal membranes at term: dead tissue or signalers of parturition? Placenta 44, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.05.013

Miah, S. M., Purdy, A. K., Rodin, N. B., MacFarlane, A. W., Oshinsky, J., Alvarez-Arias, D. A., et al. (2011). Ubiquitylation of an internalized killer cell Ig-like receptor by Triad3A disrupts sustained NF-κB signaling. J. Immunol. 186, 2959–2969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000112

Michelucci, A., Cordes, T., Ghelfi, J., Pailot, A., Reiling, N., Goldmann, O., et al. (2013). Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 7820–7825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218599110

Morgan, T. K. (2016). Role of the placenta in preterm birth: a review. Am. J. Perinatol. 33, 258–266. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570379

Morita, H., Mizutori, M., Takeuchi, K., Motoyama, S., and Maruo, T. (2001). Abundant expression of platelet-derived growth factor in spiral arteries in decidua associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension and its relevance to atherosis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 144, 271–276. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440271

Motte, S., Communi, D., Pirotton, S., and Boeynaems, J. M. (1995). Involvement of multiple receptors in the actions of extracellular ATP: the example of vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 27, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(94)00059-x

Nakae, J., Kitamura, T., Kitamura, Y., Biggs, W. H., Arden, K. C., and Accili, D. (2003). The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev. Cell 4, 119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00401-x

Nakae, J., Kitamura, T., Silver, D. L., and Accili, D. (2001). The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 (Fkhr) confers insulin sensitivity onto glucose-6-phosphatase expression. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1359–1367. doi: 10.1172/JCI12876

Onderdonk, A. B., Hecht, J. L., McElrath, T. F., Delaney, M. L., Allred, E. N., Leviton, A., et al. (2008). Colonization of second-trimester placenta parenchyma. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, 51–52.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.068

Pomerantz, J. L., and Baltimore, D. (1999). NF-kappaB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO J. 18, 6694–6704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6694

Romero, R., Dey, S. K., and Fisher, S. J. (2014). Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765. doi: 10.1126/science.1251816

Rutkowsky, J. M., Knotts, T. A., Ono-Moore, K. D., McCoin, C. S., Huang, S., Schneider, D., et al. (2014). Acylcarnitines activate proinflammatory signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 306, E1378–E1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00656.2013

Sattler, K., and Levkau, B. (2009). Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a mediator of high-density lipoprotein effects in cardiovascular protection. Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 201–211. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp070

Sferruzzi-Perri, A. N., López-Tello, J., Fowden, A. L., and Constancia, M. (2016). Maternal and fetal genomes interplay through phosphoinositol 3-kinase(PI3K)-p110α signaling to modify placental resource allocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11255–11260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602012113

Shekhawat, P., Bennett, M. J., Sadovsky, Y., Nelson, D. M., Rakheja, D., and Strauss, A. W. (2003). Human placenta metabolizes fatty acids: implications for fetal fatty acid oxidation disorders and maternal liver diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284, E1098–E1105. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00481.2002

Shibata, E., Powers, R. W., Rajakumar, A., von Versen-Höynck, F., Gallaher, M. J., Lykins, D. L., et al. (2006). Angiotensin II decreases system A amino acid transporter activity in human placental villous fragments through AT1 receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 291, E1009–E1016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00134.2006

Simmons, L. E., Rubens, C. E., Darmstadt, G. L., and Gravett, M. G. (2010). Preventing preterm birth and neonatal mortality: exploring the epidemiology, causes, and interventions. Semin. Perinatol. 34, 408–415. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.09.005

Singh, H. J., Rahman, A., Larmie, E. T., and Nila, A. (2004). Raised prorenin and renin concentrations in pre-eclamptic placentae when measured after acid activation. Placenta 25, 631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.013

Soboloff, J., Rothberg, B. S., Madesh, M., and Gill, D. L. (2012). STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 549–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm3414

Stienstra, R., Duval, C., Müller, M., and Kersten, S. (2007). PPARs, Obesity, and Inflammation. PPAR Res. 2007:95974. doi: 10.1155/2007/95974

Sultana, Z., Maiti, K., Aitken, J., Morris, J., Dedman, L., and Smith, R. (2017). Oxidative stress, placental ageing-related pathologies and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 77:aji.12653. doi: 10.1111/aji.12653

Teoh, P. J., Menzies, F. M., Hansell, C. A., Clarke, M., Waddell, C., Burton, G. J., et al. (2014). Atypical chemokine receptor ACKR2 mediates chemokine scavenging by primary human trophoblasts and can regulate fetal growth, placental structure, and neonatal mortality in mice. J. Immunol. 193, 5218–5228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401096

Thaxton, J. E., Nevers, T. A., and Sharma, S. (2010). TLR-mediated preterm birth in response to pathogenic agents. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010:378472. doi: 10.1155/2010/378472

Tokunaga, C., Yoshino, K., and Yonezawa, K. (2004). mTOR integrates amino acid- and energy-sensing pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 313, 443–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.019

Tyagi, S., Gupta, P., Saini, A. S., Kaushal, C., and Sharma, S. (2011). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: a family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2, 236–240. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.90879

Watts, D. H., Krohn, M. A., Hillier, S. L., and Eschenbach, D. A. (1992). The association of occult amniotic fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome among women in preterm labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 79, 351–357. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00005

Wegrzyn, J., Potla, R., Chwae, Y. J., Sepuri, N. B., Zhang, Q., Koeck, T., et al. (2009). Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science 323, 793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551

Winder, W. W., and Hardie, D. G. (1999). AMP-activated protein kinase, a metabolic master switch: possible roles in type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. 277, E1–E10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E1

Yang, Z. Z., Tschopp, O., Hemmings-Mieszczak, M., Feng, J., Brodbeck, D., Perentes, E., et al. (2003). Protein kinase B alpha/Akt1 regulates placental development and fetal growth. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32124–32131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302847200

Zelcer, N., and Tontonoz, P. (2006). Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883

Keywords: placenta, transcriptome, metabolome, inflammation, spontaneous preterm birth, bioenergetic metabolism

Citation: Lien Y-C, Zhang Z, Barila G, Green-Brown A, Elovitz MA and Simmons RA (2020) Intrauterine Inflammation Alters the Transcriptome and Metabolome in Placenta. Front. Physiol. 11:592689. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.592689

Received: 07 August 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020;

Published: 05 November 2020.

Edited by:

Amanda Sferruzzi-Perri, University of Cambridge, United KingdomReviewed by:

Theresa Powell, University of Colorado, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Lien, Zhang, Barila, Green-Brown, Elovitz and Simmons. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebecca A. Simmons, cnNpbW1vbnNAcGVubm1lZGljaW5lLnVwZW5uLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.