- 1College of Veterinary Medicine, Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, TN, United States

- 2College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

The term myocardial contractility is thought to have originated more than 125 years ago and has remained and enigma ever since. Although the term is frequently used in textbooks, editorials and contemporary manuscripts its definition remains illusive often being conflated with cardiac performance or inotropy. The absence of a universally accepted definition has led to confusion, disagreement and misconceptions among physiologists, cardiologists and safety pharmacologists regarding its definition particularly in light of new discoveries regarding the load dependent kinetics of cardiac contraction and their translation to cardiac force-velocity and ventricular pressure-volume measurements. Importantly, the Starling interpretation of force development is length-dependent while contractility is length independent. Most historical definitions employ an operational approach and define cardiac contractility in terms of the hearts mechanical properties independent of loading conditions. Literally defined the term contract infers that something has become smaller, shrunk or shortened. The addition of the suffix “ility” implies the quality of this process. The discovery and clinical investigation of small molecules that bind to sarcomeric proteins independently altering force or velocity requires that a modern definition of the term myocardial contractility be developed if the term is to persist. This review reconsiders the historical and contemporary interpretations of the terms cardiac performance and inotropy and recommends a modern definition of myocardial contractility as the preload, afterload and length-independent intrinsic kinetically controlled, chemo-mechanical processes responsible for the development of force and velocity.

Introduction

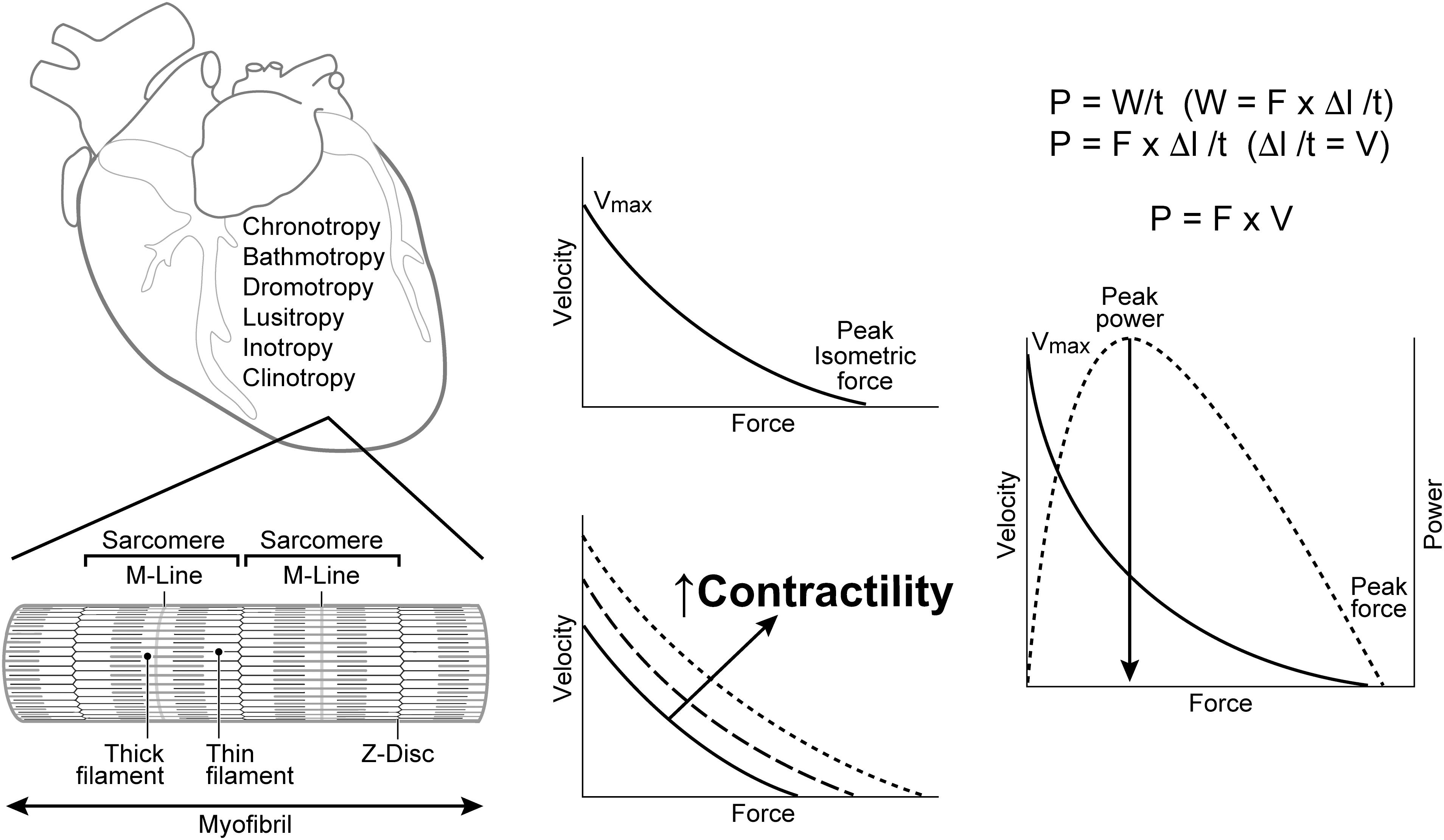

Understanding the significance and varied uses of terms that describe cardiac function requires familiarity with the methods and limitations inherent in conducting in vitro and in vivo muscle experiments and their translation to clinical practice (Hinken and Solaro, 2007; Silverman, 2007; Sivaramakrishnan et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2010; Milani-Nejad and Janssen, 2014; Ortega et al., 2015; Sequeira and van der Velden, 2015; Spinale, 2015; Sung et al., 2015; MacLeod, 2016; Noble, 2017; Sweeney and Hammers, 2018; Sweeney and Holzbaur, 2018). Muscle contraction enables animals to move and hollow organs with one-way valves, like the heart, to generate force and transfer blood from veins to arteries. The properties of the heart that permit its function are described in terms possessing the suffix “tropic” (i.e., affecting or influenced by): chronotropic, bathmotropic, dromotropic, inotropic, lusitropic, and occasionally clinotropic (Figure 1; Spinale, 2015; Mannhardt et al., 2017; Sweeney and Holzbaur, 2018). Of these, the adjective inotropic (i.e., affecting force) or abstract noun inotropy stand out as the primary focus of more than 15,000 PubMed citations (PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov) that have investigated the effects of various diseases, chemical compounds, devices or toxins on the ability of the heart to develop force (positive or negative inotropes) or to improve force development in patients with various types of heart failure (HF) (Asif, 2014; Francis et al., 2014; Sohaib and Aronow, 2015; Woody et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Terms used to describe the properties of cardiac cells include: chronotropy, bathmotropy, dromotropy, lusitropy, inotropy, and clinotropy. Left: Cardiac muscle fibers are comprised of repeating units of sarcomeres that are separated by Z-disks and contain the contractile proteins actin (thin filament) and myosin (thick filament). Center: Increases in cardiac contractility are usually represented by directionally similar changes in both force and velocity. Right: A power curve is generated as the product of force and velocity at each point along the F-V curve. V = Velocity; Vmax = maximal velocity at no load; F = Force; P = power; W = work; l = length; t = time; Δ = change; M-Line = attachment site for the thick filaments and center of the sarcomere; Z-Disk = the anchoring point for thin filaments that separate sarcomeres.

Of particular relevance to the current discussion is the identification and investigation of genetic mutations and compounds that change the heart’s inotropic state by altering sarcomeric protein cross-bridge (XB) kinetics (Spudich, 2011, 2014; Ait Mou et al., 2015; Tardiff et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2017; Nanasi et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). The small molecule myosin regulator, omecamtiv mecarbil, for example, enhances sarcomeric force development by increasing the number and synchrony of strongly bound myosin crossbridges (XB’s), thereby increasing sarcomeric force independent of changes in intracellular calcium concentration [Ca+2]i, calcium transients, shortening velocity or oxygen consumption (Malik et al., 2011; Tardiff et al., 2015; Utter et al., 2015; Hashem et al., 2017; Planelles-Herrero et al., 2017; Swenson et al., 2017; Kaplinsky and Mallarkey, 2018; Spudich, 2019; Kieu et al., 2019). Alternatively, compounds that reduce sarcomeric force without changing shortening velocity or the rate of myocardial relaxation (ex. para-nitroblebbistatin; mavacapten) are being studied as treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (Kawas et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2017; Kampourakis et al., 2018; Spudich, 2019).

Enter the ubiquitous term “contractility,” a term freely applied to describe the heart’s performance, or used as a synonym for inotropy. This conflation of terms creates misunderstandings and more importantly confuses descriptions of experimental results and test article effects.

Jewell summarized “the essence” of how muscle length regulates contraction more than 40 years ago by stating: “The end result of excitation-contraction coupling is the formation of tension-generating cross-bridges between overlapping parts of the thick (myosin) and thin (actin) filaments that make up the contractile system” (Jewell, 1977). Subsequent research has provided excellent descriptions of cardiac muscle cell electrophysiology, [Ca+2]i cycling (calcium induced- calcium release) and the sequence of processes responsible for cardiac muscle contraction (excitation-contraction coupling) (Bers, 2008; Janssen, 2010; Chung et al., 2015; Sequeira and van der Velden, 2015; Eisner et al., 2017; Sweeney and Hammers, 2018). Current investigations of cardiac muscle contraction are focused on the biochemistry (i.e., chemo-mechanical cycle), mechano-sensing and kinetic behavior of sarcomeric proteins since it is generally believed that cardiac muscle contraction: “has its roots in the individual molecular motors working in every muscle cell – the myosin molecule” (Hinken and Solaro, 2007; Janssen, 2010, 2019; Sela et al., 2010; Stehle and Iorga, 2010; Spudich, 2011; Sung et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Mamidi et al., 2019). This perspective provides historical and contemporary evidence for conveying definitions of the terms cardiac performance, inotropy and contractility.

Cardiac Function: Definitions of Cardiac Performance, Inotropy and Contractility

Cardiac Performance

Cardiac performance is the ability of the heart to pump blood into arteries and is expressed as cardiac output per unit time or as stroke volume per heartbeat. Factors that modulate the heart’s ability to pump blood (i.e., perform) include heart rate (Bristow et al., 1963; Ceconi et al., 2011), loading conditions (i.e., preload, afterload) (Milnor, 1975; Norton, 2001; Skrzypiec-Spring et al., 2007; Milan et al., 2011; Westerhof and Westerhof, 2013; O’Rourke et al., 2016), the myosin molecules contractile state (Spudich, 2011), ventricular geometry (Lieb et al., 2014), elastance (i.e., stiffness) (Fry et al., 1964; Gaasch et al., 1976; Suga et al., 1980; Sagawa, 1981; Suga, 1990; Palladino et al., 1998; Zhong et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2008; Walley, 2016; Kerkhof et al., 2018), ventricular-vascular coupling (Kass and Kelly, 1992; Antonini-Canterin et al., 2013; Walley, 2016) and prevailing neurohumoral activity, especially sympathetic-parasympathetic tone (Thomas, 2011; Gordan et al., 2015). Changes in preload and afterload have been described as “preload reserve” and “afterload matching,” respectively (Brutsaert and Sonnenblick, 1973; Ross et al., 1976; Ross, 1983; Walley, 2016; Schotola et al., 2017; Boudoulas et al., 2018). Key determinants of pump performance include heart rate, preload (volume of blood within a chamber), afterload (hindrance to ejection), and contractility. Pump performance may decrease (e.g., decrease in heart rate or preload; increase in afterload) or increase (e.g., increase in heart rate or preload; decrease in afterload) dependent upon changes in loading conditions but independent of contractility. Cardiac performance should be operationally defined as the heart’s ability to pump blood [ex. cardiac output (CO)].

Inotropy

The term “inotropic” is formed from the Greek word ino (sinew) and the suffix “tropic.” It is commonly employed in physiology to mean the force of muscular contraction. This usage most likely evolved from the Germanic translation of the term sinew to mean vigor, strength, or power. The terms inotropy, inotropism, inotropic, and inotrope have all been applied to describe the force or tension developed during muscle contraction. Most physiologists agree that the force generated by a contracting isolated muscle is dependent upon sarcomere length, [Ca+2]i, the velocity of sarcomere shortening when shortening against zero load, the type of myosin (α vs. β), and the state of phosphorylation of myosin (Sonnenblick, 1965a; Daniels et al., 1984; ter Keurs and de Tombe, 1993; Landesberg and Sideman, 2000; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2012; ter Keurs, 2012; Greenberg et al., 2014). Experimentally derived length-force, length-velocity, force-velocity, and length-force-velocity relationships obtained from isolated (in vitro) cardiac muscle fiber experiments have inextricably linked force with velocity (Sonnenblick, 1965a, b; Noble et al., 1969; Sonnenblick et al., 1969; Hugenholtz et al., 1970; Gulch and Jacob, 1975; Wikman-Coffelt et al., 1982; ter Keurs and de Tombe, 1993; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2012).

Inotropy is muscle fiber length dependent and is modified by heterometric autoregulation [Cyon-Frank-Starling mechanism (Zimmer, 1998, 2002; Katz, 2002; Amiad and Landesberg, 2016; Sequeira and van der Velden, 2017)], homeometric autoregulation [von Anrep effect in vivo; slow force response in vitro (Sarnoff et al., 1960; Cingolani et al., 2013; Clancy et al., 1968; Furst, 2015; Schotola et al., 2017)], the force-frequency relationship [Bowditch, treppe, staircase effect, chronotropic-inotropy (Bowditch, 1871; Noble et al., 1966; Anderson et al., 1973; Higgins et al., 1973; Gwathmey et al., 1990; Ross et al., 1995; Endoh, 2004; Janssen and Periasamy, 2007; Janssen, 2010; Puglisi et al., 2013)], and autonomic activity (Glick and Braunwald, 1965; Thames and Kontos, 1970; Ross et al., 1995). Inotropy decreases almost instantly, within one heartbeat, when parasympathetic activity increases, and more slowly, over 6–8 s, when sympathetic efferent activity changes (Olshansky et al., 2008). The term inotropy and its derivatives should be operationally defined as force.

Contractility

The term “contractility” is historically embedded in both the experimental and clinical cardiovascular literature and is formed from the adjective contractile and the suffix “ility” (i.e., quality), thereby forming the abstract noun contractility. The word contractile (derived from French: 1706) implies that something has the ability to shrink or shorten. Striated muscle cells and sarcomeres shrink because the contractile proteins (i.e., actin, myosin) slide past one another, developing a force that pulls the sarcomeric Z-bands closer together. The proximate source of contraction, however, arises from the cycling of actomyosin XBs that apply force to actin filaments (Sequeira and van der Velden, 2015: Sweeney and Holzbaur, 2018).

One editor in chief of a highly respected research journal has stated that, “the term contractility remains useful in order to permit succinct written and oral communication between and among scientists and clinicians” (Solaro, 2011). Others are not convinced and consider the term to be “hotly debated” (Sweeney and Hammers, 2018) and “ill-defined.”1 Many authors equate the term with inotropy (Anderson et al., 1973; Noble, 1973; Solaro, 2011; Spinale, 2015). One noted cardiovascular scholar went so far as to state, “If it weren’t for pressure-volume (P-V) loops and the end systolic pressure volume relationship (ESPVR), the term contractility would likely have disappeared” (Mirsky, 1974). The same author went on to state, “In view of the vagueness of the definitions, it may be worthwhile in the future to eliminate this term (i.e., contractility) entirely from the literature” (Mirsky, 1974). Shepherd and Vanhoutte proposed that cardiac contractility be defined as, “the intensity of the active state” that is evoked, “by the interaction between the actin and myosin molecules as a consequence of the integration of the biochemical and biophysical events resulting in the actomyosin interaction described only by a complex relationship between the force exerted by the muscle, the velocity of shortening, its length and the time of the contractile cycle at which these parameters are measured” (Shepherd and Venhoutte, 1979). Other noted muscle physiologists and clinical cardiologists have provided more detailed definitions by asserting that contractility implies the intrinsic ability of the heart, at a fixed heart rate, to generate force and shorten independent of preload and afterload (Noble, 1973; Strobeck and Sonnenblick, 1981; Burkhoff et al., 1987; Abraham et al., 2003; Bombardini, 2005). A focused group of molecular physiologists stated that, “Cardiac contractility can be defined as the tension developed and velocity of shortening (i.e., the “strength” of contraction) of myocardial fibers at a given preload and afterload. It represents a unique and intrinsic ability of cardiac muscle (contracting at a fixed heart rate) to generate a force that is independent of any load or stretch applied” (Wijayasiri et al., 2012). Integral to all current definitions of the term contractility is the tacit requirement that it is independent of loading conditions (Braunwald, 1971; Davidson et al., 1974; Katz, 1983; Kass et al., 1987; Penefsky, 1994; Bombardini, 2005; Schotola, et al., 2017) (See footenote 1).

Much of what is known about the contractile properties of the heart has been derived from in vitro experiments conducted on skeletal or cardiac muscle strips, fascicles, or fibers (Sonnenblick, 1965a; Katz, 1983; Gibbs, 1987; Katz, 2002: Batters et al., 2014) obtained from various mammalian species (Abbott and Mommaerts, 1959; Jewell, 1977; Sequeira and van der Velden, 2015; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2016; Sweeney and Hammers, 2018) in solutions where the [Ca+2]i was manipulated (Noble et al., 1969; Kentish and Stienen, 1994; Noble, 2017). Pairs of myosin heads encircle the thick myosin filament backbone in a helical or quasi-helical fashion and are described as existing in one of three transitional states: active, or when not active, disordered relaxed (DRX; approximately 50–60%) and super-relaxed (SRX: approximately 40–50%) (McNamara et al., 2015; Anderson et al., 2018). Only 10–30% of the total myosin S1 heads develop strong bonds and complete one or two XB cycles during the contractile period (low duty ratio) (Spudich, 2011; Batters et al., 2014). Various mechanical properties have been deduced from stretched (i.e., preloaded) cardiac muscle fibers stimulated to contract against varying (i.e., isotonic) or an infinite (i.e., isometric) load (i.e., afterload) (Sonnenblick, 1965a; Sonnenblick, 1965b; Noble et al., 1969; Daniels et al., 1984; McDonald, 2011). Notably, the tissues visco-elastic properties permit the sarcomeres (i.e., contractile units) in each muscle fiber to shorten and develop force (i.e., tension) regardless of the imposed loading conditions, whether or not the muscle fiber shortens (Gaasch et al., 1976; Suga, 1990; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2016). The force-velocity relation extrapolated to zero load (i.e., Vmax) has long been considered a load independent and “complete” (Sonnenblick et al., 1969) measure of cardiac contractility, particularly in isolated muscle strips (Ross et al., 1966; Sonnenblick et al., 1969; Hugenholtz et al., 1970; Mason et al., 1971; Parmley et al., 1972; Brutsaert and Sonnenblick, 1973; Kettunen et al., 1986) so long as it is “reflected by maximum force development as well as the velocity of shortening” (Strobeck and Sonnenblick, 1981). These studies have determined that muscle shortening velocity is inversely related to force generation; an increase in muscle (i.e., sarcomere) length, at any given load, increases shortening velocity; force and velocity development are tightly correlated with ATP utilization and oxygen consumption; and the maximal velocity of sarcomere shortening is, in part, dependent upon myosin composition and the degree of synchrony among the less than 30% of XBs that cycle during each resting cardiac contraction (Barany, 1967; Graham et al., 1968; Daniels et al., 1984; Sieck and Regnier, 1985; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2016).

Contemporary experimental studies of muscle contraction suggest that, “There is an apparent gap between basic and clinical science methods and measurements investigating cardiac contractile function, making it difficult to directly relate specific parameters of a XB cycle to the events in a cardiac cycle. But it is clear that ventricular contractile function is heavily dependent on XB kinetics” (Mamidi et al., 2018). Kinetic and cooperative load-dependent processes have determined that the myosin-actin attachment rate, overall cycle rate, the amount of time that myosin is attached to actin, and the total number of myosin heads in the active state (i.e., duty ratio) are all determinants of force (F) development, sliding velocity (Vmax) and the amount of ATP consumed (Stehle and Iorga, 2010; Swenson et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Sweeney and Holzbaur, 2018; Janssen, 2019). Harmonic force spectroscopy (HFS) experiments have provided further insights into how myosin’s length-dependent kinetics (detachment: kdet; recruitment: krec) control XB transitions and are modified by biologic alterations that include small regulatory molecule conversions (Piazzesi et al., 1997; Stelzer et al., 2006; Ford et al., 2010; Sung et al., 2015; Janssen, 2019). Myosin head detachment rate (i.e., kdet) has been identified as a key parameter influencing contractility because it determines the time myosin is bound to actin in a force producing state (Janssen, 2010; Greenberg et al., 2014; Sung et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018). The discovery of a host of cardiomyopathy mutations and a new generation of chemical compounds that modify myosin “motor” kinetics and chemo-mechanical processes (Malik et al., 2011; Spudich, 2014; Tardiff et al., 2015; Nanasi et al., 2016, 2018; Swenson et al., 2017; Kampourakis et al., 2018; Mamidi et al., 2018), which produce divergent effects on force and velocity suggest that revival of the term clinotropy (i.e., velocity) should be considered in order to more holistically define the term contractility as force (i.e., intoropy) and velocity (i.e., clinitropy) (MacLeod, 2016). Myocardial contractility should be defined as the load and length-independent, kinetically controlled, chemo-mechanical processes responsible for the development of force (inotropy) and velocity (clinotropy).

The Difference Between Cardiac Performance, Inotropy and Contractility in Normal and Diseased Hearts

Cardiac contractility should not be confused or conflated with cardiac performance (Braunwald, 1971; Ross, 1983; Sequeira and van der Velden, 2015). The primary functions of the ventricles are to pump blood (vis a tergo) and to draw blood (vis a fronte) from the atria (Chung et al., 2015; LaGerche and Claus, 2015; Wang et al., 2018). The ability of the heart to perform this task (i.e., create blood flow) is dependent upon heart rate and loading conditions (i.e., preload, afterload) and by how well and at what cost (i.e., O2 consumption) the left and right ventricles (LV and RV, respectively) produce pressure gradients.

Cardiac pump performance can deteriorate, improve or remain the same when cardiac contractility is normal or abnormal, depending upon the magnitude of changes in heart rate and loading conditions (i.e., preload; afterload) (Wiggers, 1951; Ross et al., 1976; Ross, 1983). This conclusion is highlighted by clinical scenarios wherein the heart’s pumping performance is enhanced by compensatory mechanisms (e.g., increased heart rate or preload, neuro-humeral activation) or drugs (e.g., antiarrhythmics, vasodilators), which improve cardiac output when cardiac contractility is decreased, or conversely, decrease cardiac output (i.e., increased afterload, blood loss, valvular stenosis or incompetence) when cardiac contractility is normal or enhanced (Triposkiadis et al., 2009; Florea and Cohn, 2014; Tint et al., 2019). For example, aortic or mitral valve insufficiency can reduce cardiac output when cardiac contractility is increased (Chatterjee and Parmley, 1977; Ross, 1983; Kittleson et al., 1984).

Myocardial contractility is not only the ability of the heart to develop force (i.e., inotropy) but also the ability to generate velocity (Sonnenblick, 1965a, b; Sonnenblick et al., 1969; Mason et al., 1971; de Tombe and Ter Keurs, 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Janssen, 2019). Genetic mutations and drugs that alter the cardiac actin-activated chemo-mechanical ATPase cycle and XB kinetics (i.e., kdet) may cause force and velocity to change independently (Anderson et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Nanasi et al., 2018).

Conclusion

Cardiac muscle contraction “has its roots in the individual molecular motors working in every muscle cell – the myosin molecule” (Liu et al., 2018). Myocardial contraction is mechanically manifested as the force and velocity generated during sarcomere shortening. It occurs when Ca+2 binds to troponin-C and reconfigures tropomyosin so that myosin heads fueled by the energy produced from ATP hydrolysis produce effective XB cycling.

The question of acceptability or usefulness of the term cardiac contractility should be based upon whether the word, contractility, can actually define a unique physiological process that is quantifiable. A multitude of methods have evolved for quantifying myocardial contractility, all of which are dependent upon the ability of sarcomeres to develop force and velocity (Urschel et al., 1980; Naiyanetr, 2013; Spinale, 2015; Kohli and Kovacs, 2017). Myocardial contractility should be defined as the load and length-independent, intrinsic, kinetically controlled, chemo-mechanical processes responsible for the development of force (inotropy) and velocity (clinotropy).

Author Contributions

WM reviewed the literature, organized and drafted the work and designed the figure. RH drafted and contributed key components to the discussion of inotropy.

Funding

Lincoln Memorial University, College of Veterinary Medicine.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

Abbott, B. C., and Mommaerts, W. F. (1959). A study of inotropic mechanisms in the papillary muscle preparation. J. Gen. Physiol. 42, 533–551. doi: 10.1085/jgp.42.3.533

Abraham, T. P., Laskowski, C., Zhan, W. Z., Belohlavek, M., Martin, E. A., Greenleaf, J. F., et al. (2003). Myocardial contractility by strain echocardiography: comparison with physiological measurements in an in vitro model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 285, H2599–H2604. doi: 10.1152/alpheart.00994.2002

Ait Mou, Y., Bollensdorff, C., Cazorla, O., Magdi, Y., and de Tombe, P. P. (2015). Exploring cardiac biophysical properties. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2015:10. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2015.10

Amiad, P. A. D., and Landesberg, A. (2016). The cross-bridge dynamics is determined by two length-independent kinetics: implications on muscle economy and Frank–Starling Law. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 90, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.007

Anderson, P. A., Manring, A., and Johnson, E. A. (1973). Force-frequency relationship: A basis for a new index of cardiac contractility? Circ. Res. 33, 665–671. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.6.665

Anderson, R. L., Trivedi, D. V., Sarkar, S. S., Henze, M., Ma, W., Gong, H., et al. (2018). Deciphering the super relaxed state of human β-cardiac myosin and the mode of action of mavacamten from myosin molecules to muscle fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E8143–E8152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809540115

Antonini-Canterin, F., Poli, S., Vriz, O., Pavan, D., Bello, V. D., and Nicolosi, G. L. (2013). The Ventricular-Arterial Coupling: from basic pathophysiology to clinical application in the echocardiography laboratory. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 23, 91–95. doi: 10.4103/2211-4122.127408

Asif, M. (2014). A review on study of various ionotropic calcium sensitizing drugs in congestive heart failure treatment. Am. J. Med. Case Rep. 2, 57–74. doi: 10.12691/ajmcr-2-3-5

Barany, M. (1967). ATPase activity of myosin correlated with speed of muscle shortening. J. Gen. Physiol. 50, 197–218. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.197

Batters, C., Veigel, C., Homsher, E., and Sellers, J. R. (2014). To understand muscle you must take it apart. Front. Physiol. 5:90. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00090

Bers, D. M. (2008). Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 70, 24–49. doi: 10.1148/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455

Bombardini, T. (2005). Myocardial contractility in the echo lab: molecular, cellular and pathophysiological basis. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 3:27. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-3-27

Boudoulas, K. D., Triposkiadis, K., and Boudoulas, H. (2018). Evaluation of left ventricular performance: is there a gold standard. Cardiology 140, 257–261. doi: 10.1159/000492109

Bowditch, H. P. (1871). Ueber die Eigenthuemlichkeiten der Reizbarkeit, welche die Muskelfasern des Herzens zeigen. Ber. Sachs. Ges. Akad. Wiss 23, 652–689.

Braunwald, E. (1971). On the difference between the heart’s output and its contractile state. Circulation 43, 171–174. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.2.171

Bristow, J. D., Ferguson, R. E., Mintz, R., and Rapaport, E. (1963). The influence of heart rate on left ventricular volume in dogs. J. Clin. Invest. 42, 649–655. doi: 10.1172/JCI104755

Brutsaert, D. L., and Sonnenblick, E. H. (1973). Cardiac muscle mechanics in the evaluation of myocardial contractility and pump function: problems, concepts, and directions. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 16, 337–361. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(73)80005-2

Burkhoff, D., Sugiura, S., Yue, D. T., and Sagawa, K. (1987). Contractility-dependent curvilinearity of end-systolic pressure-volume relations. Am. J. Physiol. 252, H1218–H1227. doi: 10.11152/ajpheart.1987.6.H1218

Campbell, K. B., Simpson, A. M., Campbell, S. G., Granzier, H. L., and Slinker, B. K. (2008). Dynamic left ventricular elastance: a model for integrating cardiac muscle contraction into ventricular pressure-volume relationships. J. Appl. Physiol. 104, 958–975. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00912.2007

Ceconi, C., Guardigli, G., Rizzo, P., Fancolini, G., and Farrari, R. (2011). The heart rate story. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 13, C4–C13. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/sur014

Chatterjee, K., and Parmley, W. W. (1977). The role of vasodilator therapy in heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 19, 301–325. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(77)90006-8

Chung, C. S., Shmuylovich, L., and Kovács, S. J. (2015). What global diastolic function is, what it is not, and how to measure it. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 309, H392–H406. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00436.2015

Cingolani, H. E., Pérez, N. G., Cingolani, O. H., and Ennis, I. L. (2013). The Anrep effect: 100 years later. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304, H175–H182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00508.2012

Clancy, R. L., Graham, T. P. Jr., Ross, J., Sonnenblick, E. H., and Braunwald, E. (1968). Influence of aortic pressure-induced homeometric autoregulation on myocardial performance. Am. J. Physiol. 214, 1186–1192. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.214.5.1186

Daniels, M., Noble, M. I., ter Keurs, H. E., and Wohlfart, B. (1984). Velocity of sarcomere shortening in rat cardiac muscle: relationship to force, sarcomere length, calcium and time. J. Physiol. 355, 367–381. doi: 10.1113/jphphysiol.1984.sp015424

Davidson, D. M., Covell, J. W., Malloch, C. I., and Ross, J. Jr. (1974). Factors influencing indices of left ventricular contractility in the conscious dog. Cardiovasc. Res. 8, 299–312. doi: 10.1093/cvr/8.3.299

de Tombe, P. P., and Ter Keurs, H. E. (2012). The velocity of cardiac sarcomere shortening: mechanisms and implications. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 33, 431–437. doi: 10.1007/s10974-012-9310-0

de Tombe, P. P., and Ter Keurs, H. E. (2016). Cardiac muscle mechanics: sarcomere length matters. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 91, 145–150. doi: 10.1016/jymce.2015.12.006

Eisner, D. A., Caldwell, J. L., Kistamas, K., and Trafford, A. W. (2017). Calcium and excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Circ. Res. 121, 181–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310230

Endoh, M. (2004). Force-frequency relationship in intact mammalian ventricular myocardium: physiological and pathophysiological relevance. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 500, 73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.013

Florea, G. V., and Cohn, N. J. (2014). The autonomic nervous system and heart failure. Cric. Res. 114, 1815–1826.

Ford, S. J., Chandra, M., Mamidi, R., Dong, W., and Campbell, K. B. (2010). Model representation of the nonlinear step response in cardiac muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 136, 159–177. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010467

Francis, G. S., Bartos, J. A., and Adatya, S. (2014). Inotropes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 2069–2078. doi: 10.1016/jack.2014.01.016

Fry, D., Griggs, D., and Greenfield, J. (1964). Myocardial mechanics: tension-velocity-length relationships of heart muscle. Circ. Res. 14, 73–85. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.1.73

Furst, B. (2015). The heart: pressure-propulsion pump or organ of impedance? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 29, 1688–1701. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.02.022

Gaasch, W. H., Levine, H. J., Quinones, M. A., and Alexander, J. K. (1976). Left ventricular compliance: mechanisms and clinical implications. Am. J. Cardiol. 38, 645–653. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(76)80015-x

Gibbs, C. L. (1987). Cardiac energetics and the Fenn effect. Basic Res. Cardiol. 82(Suppl. 2), 61–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11289-2_6

Glick, G., and Braunwald, E. (1965). Relative roles of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in the reflex control of heart rate. Circ. Res. 16, 363–375. doi: 10.1161/01/res/16/4/363

Gordan, R., Gwathmey, J. K., and Xie, L. H. (2015). Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World J. Cardiol. 7, 204–214. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204

Graham, T. P. Jr., Covell, J. W., Sonnenblick, E. H., Ross, J. Jr., and Braunwald, E. (1968). Control of myocardial oxygen consumption: relative influence of contractile state and tension development. J. Clin. Invest. 47, 375–385. doi: 10.1172/JCI105734

Greenberg, M. J., Shuman, H., and Ostap, E. M. (2014). Inherent force-dependent properties of β -cardiac myosin contribute to the force-velocity relationship of cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 107, L41–L44. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.005

Gulch, R. W., and Jacob, R. (1975). Length-tension diagram and force-velocity relations of mammalian cardiac muscle under steady-state conditions. Pflügers Arch. 355, 331–346. doi: 10.1007/bf00579854

Gwathmey, J. K., Slawsky, M. T., Hajjar, R. J., Briggs, G. M., and Morgan, J. P. (1990). Role of intracellular calcium handling in force-interval relationships of human ventricular myocardium. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 1599–1613. doi: 10.1172/JCI114611

Hashem, S., Tiberti, M., and Fornili, A. (2017). Allosteric modulation of cardiac myosin dynamics by omecamtiv mecarbil. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005826

Higgins, C. B., Vatner, S. F., Franklin, D., and Braunwald, E. (1973). Extent of regulation of the heart’s contractile state in the conscious dog by alteration in the frequency of contraction. J. Clin. Invest. 52, 1187–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI107285

Hinken, A. C., and Solaro, R. J. (2007). A dominant role of cardiac molecular motors in the intrinsic regulation of ventricular ejection and relaxation. Physiology 22, 73–80. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2006

Hugenholtz, P. G., Ellison, R. C., Urschel, C. W., Mirsky, I., and Sonnenblick, E. H. (1970). Myocardial force-velocity relationships in clinical heart disease. Circulation 41, 191–202. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.2.191

Janssen, P. M. (2010). Kinetics of cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation are linked and determined by properties of the cardiac sarcomere. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299, H1092–H1099. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00417.2010

Janssen, P. M., and Periasamy, M. (2007). Determinants of frequency-dependent contraction and relaxation of mammalian myocardium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 43, 523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.012

Janssen, P. M. L. (2019). Myocardial relaxation in human heart failure: why sarcomere kinetics should be center-stage. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 661, 145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.11.011

Jewell, B. (1977). A reexamination of the influence of muscle length on myocardial performance. Circ. Res. 40, 221–230. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.3.221

Kampourakis, T., Zhang, X., Sun, Y., and Irving, M. (2018). Omecamtiv mecarbil and blebbistatin modulate cardiac contractility by perturbing the regulatory state of the myosin filament. J. Physiol. 596, 31–46. doi: 10.1113/jp275050

Kaplinsky, E., and Mallarkey, G. (2018). Cardiac myosin activators for heart failure therapy: focus on omecamtiv mecarbil. Drugs Context 7:212518. doi: 10.7573/dic.212518

Kass, D. A., and Kelly, R. P. (1992). Ventriculo-arterial coupling: concepts, assumptions, and applications. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 20, 41–62. doi: 10.1007/bf02368505

Kass, D. A., Maughan, W. L., Guo, Z. M., Kono, A., Sunagawa, K., and Sagawa, K. (1987). Comparative influence of load versus inotropic states on indices of ventricular contractility: experimental and theoretical analysis based on pressure-volume relationships. Circulation 76, 1422–1437. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.6.1422

Katz, A. M. (1983). Regulation of myocardial contractility 1958–1983: an Odyssey. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1, 42–51. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80009-6

Katz, A. M. (2002). Ernest henry starling, his predecessors, and the “Law of the Heart”. Circulation 106, 2986–2992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR0000040594.96123.55

Kawas, R. F., Anderson, R. L., Ingle, S. R. B., Song, Y., Sran, A. S., and Rodriguez, H. M. (2017). A small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin acts on multiple stages of the myosin chemomechanical cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 16571–16577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.776815

Kentish, J. C., and Stienen, G. J. (1994). Differential effects of length on maximum force production and myofibrillar ATPase activity in rat skinned cardiac muscle. J. Physiol. 475, 175–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020059

Kerkhof, P. L., Kuznetsova, T., Ali, R., and Handly, N. (2018). Left ventricular volume analysis as a basic tool to describe cardiac function. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 42, 130–139. doi: 10.1152/advan.00140.2017

Kettunen, R., Timisjärvi, J., Kouvalainen, E., Rämö, P., and Linnaluoto, M. (1986). The automatic computation of pressure-derived maximal shortening velocity (Vmax) of the unloaded contractile element in the intact canine heart left ventricle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 127, 467–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb07930.x

Kieu, T. T., Awinda, P. O., and And Tanner, B. C. W. (2019). Omecamtiv mecarbil slows myosin kinetics in skinned rat myocardium at physiologic temperature. Biophys. J. 116, 2149–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.020

Kittleson, M. D., Eyster, G. E., Knowlen, G. G., Bari Olivier, N., and Anderson, L. K. (1984). Myocardial function in small dogs with chronic mitral regurgitation and severe congestive heart failure. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 184, 455–459.

Kohli, K., and Kovacs, S. J. (2017). The quest for load-independent left ventricular chamber properties: exploring the normalized pressure-volume loop. Physiol. Rep. 6:e13160. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13160

LaGerche, A., and Claus, P. (2015). Right ventricular suction: an important determinant of cardiac performance. Cardiovasc. Res. 107, 7–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv165

Landesberg, A., and Sideman, S. (2000). Force-velocity relationship and biochemical-to-mechanical energy conversion by the sarcomere. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 284, H1274–H1284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.h1274

Lieb, W., Philimon, G., Larson, M. G., Aragam, J., Zile, M. R., Cheng, S., et al. (2014). The natural history of left ventricular geometry in the community: clinical correlates and prognostic significance of change in LV geometric pattern. JACC Cardioavasc. Imaging 7, 870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.05.008

Liu, C., Kawana, M., Song, D., Ruppel, K. M., and Spudich, J. A. (2018). Controlling load-dependent kinetics of β-cardiac myosin at the single-molecule level. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 505–514. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0069-x

MacLeod, K. T. (2016). Recent advances in understanding cardiac contractility in health and disease. F1000Res. 5:F1000 Faculty Rev-1770. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8661.1

Malik, F. I., Hartman, J. J., Elias, K. A., Morgan, B. P., Rodriguez, H., Brejc, K., et al. (2011). Cardiac myosin activation: a potential therapeutic approach for systolic heart failure. Science 331, 1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1200113

Mamidi, R., Li, J., Doh, C. Y., Holmes, J. B., and Stelzer, J. E. (2019). Lost in translation: interpreting cardiac muscle mechanics data in clinical practice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 662, 213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.12.021

Mamidi, R., Li, J., Doh, C. Y., Verma, S., and Stelzer, S. E. (2018). Impact of the myosin modulator mavacamten on force generation and cross-bridge behavior in a murine model of hypercontractility. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7:e009627. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009627

Mannhardt, I., Eder, A., Dumotier, B., Prondzynski, M., Kramer, E., Traebert, M., et al. (2017). Blinded contractility analysis in hiPSC-Cardiomyocytes in engineered heart tissue format: comparison with human atrial trabeculae. Toxicol. Sci. 158, 164–175. doi: 10.1093/yoxscikfx081

Mason, D. T., Braunwald, E., Covell, J. W., Sonnenblick, E. H., and Ross, J. (1971). Assessment of cardiac contractility: the relation between the rate of pressure rise and ventricular pressure during isovolumic systole. Circulation 44, 47–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.1.47

McDonald, K. S. (2011). The interdependence of Ca2+ activation, sarcomere length, and power output in the heart. Pflugers Arch. 462, 61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0949-y

McNamara, J. W., Li, A., dos Remedios, C. G., and Cooke, R. (2015). The role of super-relaxed myosin in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biophys. Rev. 7, 5–14. doi: 10.1007/s12551-014-0151-5

Milan, A., Tosello, F., Fabbri, A., Vairo, A., Leone, D., Chiarlom, M., et al. (2011). Arterial stiffness: from physiology to clinical implications. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 18, 1–12. doi: 10.2165/11588020-000000000-00000

Milani-Nejad, N., and Janssen, P. M. (2014). Small and large animal models in cardiac contraction research: advantages and disadvantages. Pharmacol. Ther. 141, 235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.10.007

Miller, M. S., Tanner, B. C., Nyland, L. R., and Vigoreaux, J. O. (2010). Comparative biomechanics of thick filaments and thin filaments with functional consequences for muscle contraction. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010:473423. doi: 10.1155/2010/473423

Milnor, W. R. (1975). Arterial impedance as ventricular afterload. Circ. Res. 36, 565–570. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.5.565

Mirsky, I. (1974). “Basic terminology and formulae for left ventricular wall stress,” in Cardiac Mechanics: Physiological, Clinical and Mathematical Considerations, eds I. Mirsky, D. N. Ghista, and H. Sandler (New York, NY: John Welcome and Sons), 3.

Naiyanetr, P. (2013). “A review of cardiac contractility indices during LVAD support,” in Proceedings of the IFMBE World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, ed. M. Long (Berlin: Springer).

Nanasi, P., Komaromi, I., Gaburjakova, M., and Almassy, J. (2018). Omecamtiv Mecarbil: a myosin motor activator agent with promising clinical performance and new in vitro results. Curr. Med. Chem. 25, 1720–1728. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666171222164320

Nanasi, P., Váczi, K., and Papp, Z. (2016). The myosin activator omecamtiv mecarbil: a promising new inotropic agent. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94, 1033–1039. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0573

Noble, M. I. (1973). Problems in the definition of contractility in terms of myocardial mechanics. Eur. J. Cardiol. 1, 209–216.

Noble, M. I. (2017). Whatever happened to measuring ventricular contractility in heart failure? Card. Fail. Rev. 3, 79–82. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2017:17:1

Noble, M. I., Bowen, T. E., and Hefner, L. L. (1969). Force-velocity relationship of cat cardiac muscle, studied by isotonic and quick-release techniques. Circ. Res. 24, 821–833. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.6.821

Noble, M. I., Trenchard, D., and Guz, A. (1966). Effect of changing heart rate on cardiovascular function in the conscious dog. Circ. Res. 19, 206–213. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.1.206

Norton, J. M. (2001). Toward consistent definitions for preload and afterload. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 25, 53–61. doi: 10.1152/advances.2001.25.1.53

Olshansky, B., Sabbah, H. N., Hauptman, P. J., and Colucci, W. S. (2008). Parasympathetic nervous system and heart failure: pathophysiology and potential implications for therapy. Circulation 118, 863–871. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760405

O’Rourke, M. F., O’Brien, C., and Edelman, E. R. (2016). Arterial stiffening in perspective: advances in physical and physiological science over centuries. Am. J. Hypertens 29, 785–791. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw019

Ortega, J. O., Lindstedt, S. L., Nelson, F. E., Jubnas, S. A., Kusmerick, M. J., and Conley, K. E. (2015). Muscle force, work and cost: a novel technique to revisit the Fenn effect. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2075–2082. doi: 10.1242/jeb.114512

Palladino, J. T., Mulier, J. P., and Noordergraaf, A. (1998). “Defining ventricular elastance,” in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Hong Kong, 383–386.

Parmley, W. W., Chuck, L., and Sonnenblick, E. H. (1972). Relation of Vmax to different models of cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 30, 34–43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.6.1106

Penefsky, Z. J. (1994). The determinants of contractility in the heart. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Physiol. 109, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)90307-7

Piazzesi, G., Linari, M., Reconditi, M., Vanzi, F., and Lombardi, V. (1997). Cross-bridge detachment and attachment following a step stretch imposed on active single frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 498, 3–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021837

Planelles-Herrero, V. J., Hartman, J. J., Robert-Paganin, J., Malik, F. I., and Houdusse, A. (2017). Mechanistic and structural basis for activation of cardiac myosin force production by omecamtiv mecarbil. Nat. Commun. 8:190. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00176-5

Puglisi, J. L., Negroni, J. A., Chen-Izu, Y., and Bers, D. M. (2013). The force-frequency relationship: insights from mathematical modeling. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 37, 28–34. doi: 10.1152/advan.00072.2011

Ross, J. Jr., Franklin, D., and Sasayama, S. (1976). Preload, afterload, and the role of afterload mismatch in the descending limb of cardiac function. Eur. J. Cardiol. 4, 77–86.

Ross, J. Jr., Miura, T., Kambayashi, M., Eising, G. P., and Ryu, K. H. (1995). Adrenergic control of the force-frequency relation. Circulation 92, 2327–2332. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2327

Ross, J. (1983). Cardiac function and myocardial contractility: a perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1, 52–62. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80010-2

Ross, J., Covell, J., Sonnenblick, E., and Braunwald, E. (1966). Contractile state of the heart characterized by force-velocity relations in variably afterloaded and isovolumic beats. Circ. Res. 18, 149–153. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.2.149

Sagawa, K. (1981). The end-systolic pressure-volume relation of the ventricle: definition, modifications and clinical use. Circulation 63, 1223–1227. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.6.1223

Sarnoff, S. J., Mitchell, J. H., Gilmore, J. P., and Remensnyder, J. P. (1960). Homeometric autoregulation in the heart. Circ. Res 8, 1077–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.res.8.5.1077

Schotola, H., Sossalla, S. T., Renner, A., Gummert, J., Danner, B. C., Schott, P., et al. (2017). The contractile adaption to preload depends on the amount of afterload. ESC Heart Fail. 4, 468–478. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12164

Sela, G., Yadid, M., and Landesberg, A. (2010). Theory of cardiac sarcomere contraction and the adaptive control of cardiac function to changes in demands. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1188, 222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05104.x

Sequeira, V., and van der Velden, J. (2015). Historical perspective on heart function: the Frank-Starling Law. Biophys. Rev. 7, 421–447. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0184-4

Sequeira, V., and van der Velden, J. (2017). The Frank-Starling Law: a jigsaw of titin proportions. Biophys. Res. 9, 259–267. doi: 10.1007/s112551-017-0272-8

Shepherd, J. T., and Venhoutte, P. M. (1979). “Components of the cardiovascular system: how structure is geared to function,” in The Human Cardiovascular System: Facts and Concepts, eds T. J. Shepherd and P. M. Venoutte (New York, NY: Raven Press), 53–54.

Sieck, G. C., and Regnier, M. (1985). Invited Review: plasticity and energetic demands of contraction in skeletal and cardiac muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 90, 1158–1164. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.1158

Silverman, M. E. (2007). De Motu Cordis: the Lumleian Lecture of 1616: an imagined playlet concerning the discovery of the circulation of the blood by William Harvey. J. R. Soc. Med. 100, 199–204. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.4.199

Sivaramakrishnan, S., Ashley, E., Leinwand, L., and Spudich, J. A. (2009). Insights into human beta-cardiac myosin function from single molecule and single cell studies. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2, 426–440. doi: 10.1007/s12265-009-9129-2

Skrzypiec-Spring, M., Grotthus, B., Szelag, A., and Schulz, R. (2007). Isolated heart perfusion according to Langendorff—still viable in the new millennium. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 55, 113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2006.05.006

Sohaib, T., and Aronow, W. S. (2015). Use of inotropic agents in treatment of systolic heart failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 29060–29068. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226147

Solaro, R. J. (2011). Regulation of Cardiac Contractility. San Rafeal, CA: Morgan Claypool Life Sciences.

Sonnenblick, E. H. (1965a). Determinants of active state in heart muscle: force, velocity, instantaneous muscle length, time. Fed. Proc. 24, 1396–1409.

Sonnenblick, E. H. (1965b). Instantaneous force-velocity-length determinants in the contraction of heart muscle. Circ. Res. 16, 441–451. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.5.441

Sonnenblick, E. H., Parmley, W. W., and Urschel, C. W. (1969). The contractile state of the heart as expressed by force-velocity relations. Am. J. Cardiol. 23, 488–503. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90002-2

Spinale, F. G. (2015). Assessment of cardiac function–Basic principles and approaches. Compr. Physiol. 5, 1911–1946. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140054

Spudich, J. A. (2011). Molecular motors: forty years of interdisciplinary research. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 3936–3939. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0447

Spudich, J. A. (2014). Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: four decades of basic research on muscle lead to potential therapeutic approaches to these devastating genetic diseases. Biophys. J. 106, 1236–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.011

Spudich, J. A. (2019). Three perspectives on the molecular basis of hypercontractility caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Pflugers Arch. 471, 701–717. doi: 10.1007/s00424-019-02259-2

Stehle, R., and Iorga, B. (2010). Kinetics of cardiac sarcomeric processes and rate-limiting steps in contraction and relaxation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.020

Stelzer, J. E., Larsson, L., Fitzsimons, D. P., and Moss, R. L. (2006). Activation dependence of stretch activation in mouse skinned myocardium: implications for ventricular function. J. Gen. Physiol. 127, 95–107. doi: 10.1085/jgp.2005099432

Strobeck, J. E., and Sonnenblick, E. H. (1981). Myocardial and ventricular function. Part I: isolated muscle. Herz 6, 261–274.

Suga, H. (1990). Energetics of the time-varying elastance model, a visco-elastic model, matches. Mommaerts’ unifying concept of the Fenn effect of muscle. Jpn. Heart J. 31, 341–353. doi: 10.1536/jhj.31.341

Suga, H., Sagawa, K., and Demer, L. (1980). Determinants of instantaneous pressure in canine left ventricle. Time and volume specification. Circ. Res. 46, 256–263. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.2.256

Sung, J., Nag, S., Mortensen, K. I., Vetergaard, C. L., Sutton, S., Ruppel, K., et al. (2015). Harmonic force spectroscopy measures of load-dependent kinetics of individual human β-cardiac myosin molecules. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8931

Sweeney, H. L., and Hammers, D. W. (2018). Muscle contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10:a023200. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023200

Sweeney, H. L., and Holzbaur, E. L. (2018). Motor proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10:a021931. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021931

Swenson, A. M., Tang, W., Blair, C. A., Fetrow, C. M., Unrath, W. C., Previs, M. J., et al. (2017). Omecamtiv mecarbil enhances the duty ratio of human β-cardiac myosin resulting in calcium sensitivity and slowed sorce development in cardiac muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 3768–3778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m116.748780

Tang, W., Blair, C. A., Walton, S. D., Málnási-Csizmadia, A., Campbell, K. S., and Yengo, C. M. (2017). Modulating beta-cardiac myosin function at the molecular and tissue. Front. Physiol. 7:659. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00659

Tardiff, J. C., Carrier, L., Bers, D. M., Poggesi, C., Ferrantini, C., Coppini, R., et al. (2015). Targets for therapy in sarcomeric cardiomyopathies. Cardiovasc. Res. 105, 457–470. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv023

ter Keurs, H. E. (2012). The interaction of calcium with the sarcomeric proteins: role in function and dysfunction of the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H38–H50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00219.2011

ter Keurs, H. E., and de Tombe, P. P. (1993). Determinants of velocity of sarcomere shortening in mammalian myocardium. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 332, 649–664.

Thames, M. D., and Kontos, H. A. (1970). Mechanisms of baroreceptor-induced changes in heart rate. Am. J. Physiol. 218, 251–256. doi: 10.1152/lajplegacy.1970.218.1.251

Thomas, G. D. (2011). Neural control of the circulation. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 35, 28–32. doi: 10.1152/advan.00114.2010

Tint, D., Florea, R., and Micu, S. (2019). New generation cardiac contractility modulation device-filling the gap in heart failure treatment. J. Clin. Med. 8:855. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050588

Triposkiadis, F., Karayannis, G., Giiamouzis, G., Skularigis, J., Lourida, G., and Butler, J. (2009). The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54, 1747–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015

Urschel, C. W., Vokonas, P. S., Henderson, A. H., Liedtke, A. J., Horwitz, L. D., and Sonnenblick, E. H. (1980). Critical evaluation of indices of myocardial contractility derived from the isovolumic phase of contraction. Cardiology 65, 4–22. doi: 10.1159/000170791

Utter, M. S., Ryba, D. M., Li, B. H., Wolska, B. M., and Solaro, R. J. (2015). Omecamtiv mecarbil, a cardiac myosin activator, increases Ca2+ sensitivity in myofilaments with a dilated cardiomyopathy mutant tropomyosin E54K. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 66, 347–353. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000286

Walley, K. R. (2016). Left ventricular function: time-varying elastance and left ventricular aortic coupling. Crit. Care 20:270. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1439-6

Wang, Y., Yuan, C., Kazmierczak, K., Szczesna-Cordary, D., and Burghardt, T. P. (2018). Single cardiac ventricular myosins are autonomous motors. Open Biol. 8:170240. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170240

Westerhof, N., and Westerhof, B. E. (2013). A review of the methods to determine the functional arterial parameters stiffness and resistance. J. Hypertens. 31, 1769–1775. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283633589

Wiggers, C. J. (1951). Determinants of cardiac performance. Circulation 4, 485–495. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.4.4.485

Wijayasiri, L., Rhodes, A., and Cecconi, M. (2012). “Cardiac Contractility,” in Encyclopedia of Intensive Care Medicine, eds J. L. Vincent and J. B. Hall (Berlin: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00418-6.192

Wikman-Coffelt, J., Refsum, H., Hollosi, G., Rouleau, L., Chuck, L., and Parmley, W. W. (1982). Comparative force-velocity relation and analyses of myosin of dog atria and ventricles. Am. J. Physiol. 243, H391–H397.

Woody, M. S., Greenberg, M. J., Barua, B., Winkelmann, D. A., Goldman, Y. E., and Ostap, E. M. (2018). Positive cardiac inotrope omecamtiv mecarbil activates muscle despite suppressing the myosin working stroke. Nat. Commun. 9:3838. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06193-2

Zhong, L., Ghista, D. N., Ng, E. Y. K., and Lim, S. T. (2005). Passive and active ventricular elastances of the left ventricle. Biomed. Eng. Online 4:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-4-10

Zimmer, H. G. (1998). The isolated perfused heart and its pioneers. News Physiol. Sci. 13, 203–210. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.4.203

Keywords: chemomechanical cycle, contractility, INOTROPY, cardiac performance, myocardial function

Citation: Muir WW and Hamlin RL (2020) Myocardial Contractility: Historical and Contemporary Considerations. Front. Physiol. 11:222. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00222

Received: 25 October 2019; Accepted: 26 February 2020;

Published: 31 March 2020.

Edited by:

J-P. Jin, Wayne State University School of Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Charles S. Chung, Wayne State University School of Medicine, United StatesMike Regnier, University of Washington, United States

Copyright © 2020 Muir and Hamlin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William W. Muir, bW9ub3MzNjlAZ21haWwuY29t

William W. Muir

William W. Muir Robert L. Hamlin

Robert L. Hamlin