- Cardiovascular Innovation Institute, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, United States

In recent years, the role of RNA has expanded to the extent that protein-coding RNAs are now the minority with a variety of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) now comprising the majority of RNAs in higher organisms. A major contributor to this shift in understanding is RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), which allows a largely unconstrained method for monitoring the status of RNA from whole organisms down to a single cell. This observational power presents both challenges and new opportunities, which require specialized bioinformatics tools to extract knowledge from the data and the ability to reuse data for multiple studies. In this review, we summarize the current status of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) research in endothelial biology. Then, we will cover computational methods for identifying, annotating, and characterizing lncRNAs in the heart, especially endothelial cells.

Introduction

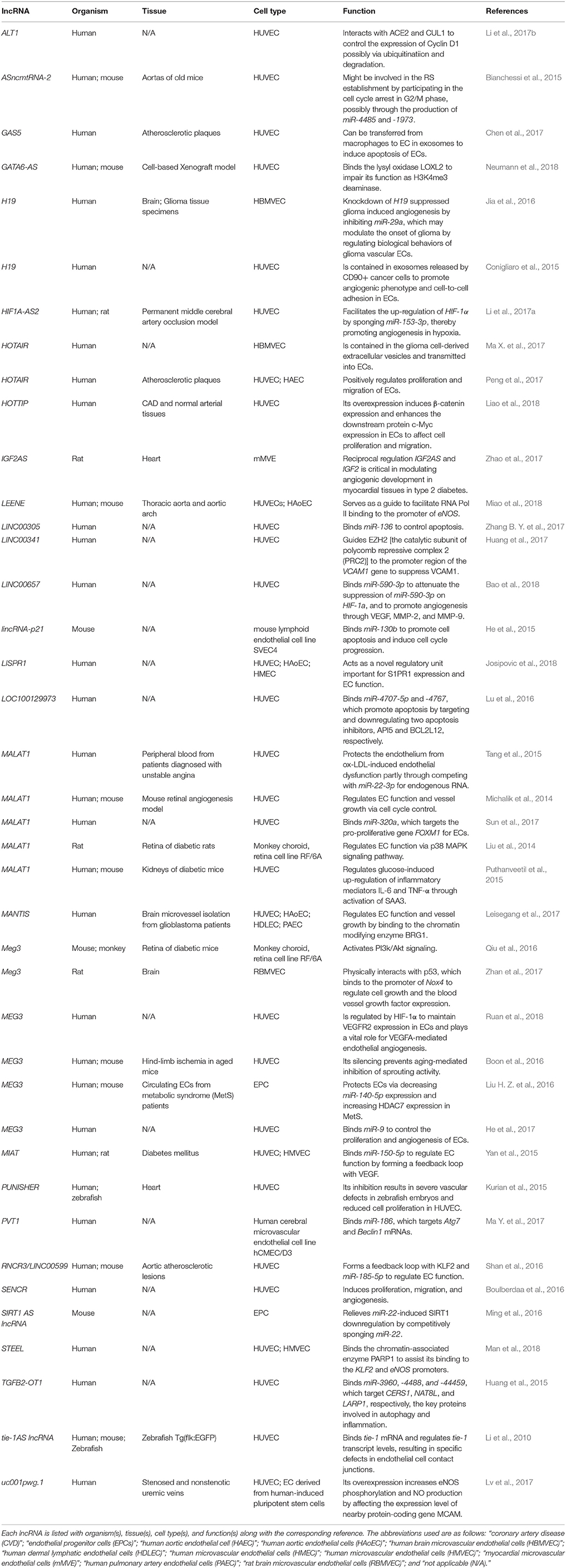

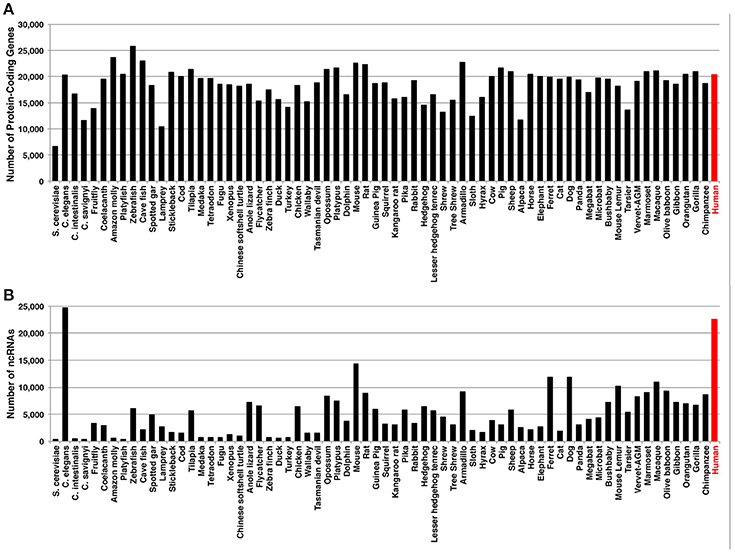

The development of next generation sequencing (NGS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has significantly improved the understanding of transcriptomes. For example, we now know that most of the human genome is transcribed (Lander et al., 2001), yet only a small percent of these RNAs code for protein (Weirick et al., 2016a). When the human genome was annotated (i.e., giving the definition to the genome by naming a particular gene and its corresponding exons), it was originally thought that the number of protein-coding genes in humans should be more than those of lower organisms (e.g., yeast, plants, fishes, amphibians) (Mercer et al., 2011; Ezkurdia et al., 2014). However, when the numbers of protein-coding genes are compared among species, the number of human genes is not more than those of lower organisms (Figure 1A). Given that humans are able to carry out more complex tasks than lower organisms, the question remains in the field: What aspect of our genome allows for the increased complexity? One school of thoughts is that proteins can be modified for various biological processes (e.g., phosphorylation of a protein for its activation). Another school suggests for the increased variety of isoforms resulting from one gene due to the alternative splicing events. In both schools, the ultimate final products are proteins as we know more about proteins than RNAs. Last school postulates that the increased number of ncRNAs (especially, lncRNAs) is at the base of the highest complexity in human, although it is highly subjective as the number of ncRNAs depends on how well the organism is studied as C. elegans has more lncRNAs than any other organisms (Figure 1B). At the moment, it is most likely that the combination of these schools of thoughts may yield important answers to the question.

Figure 1. Numbers of (A) protein-coding genes and (B) ncRNAs, including miRNAs and lncRNAs. The information is based on the Ensembl database (Accessed on May 5, 2017).

In recent years, many review articles about lncRNAs in the heart are published (Geisler and Coller, 2013; Archer et al., 2015; Devaux et al., 2015; Iyer et al., 2015; Ounzain et al., 2015a; Philippen et al., 2015; Rizki and Boyer, 2015; Uchida and Dimmeler, 2015; Ballantyne et al., 2016; Busch et al., 2016; Lorenzen and Thum, 2016; Uchida and Bolli, 2017; Viereck and Thum, 2017; Sallam et al., 2018). Furthermore, there are large amounts of screening data available for lncRNAs expressed in the heart (Ounzain et al., 2014, 2015b,c; Kurian et al., 2015) even single-cell RNA-seq data (Chan et al., 2016; Delaughter et al., 2016; King et al., 2017; Lescroart et al., 2018; Skelly et al., 2018). However, these data sets were mostly generated for specific purposes and have largely not been analyzed for lncRNAs. Here, we will focus on endothelial cells (ECs), an important cell type in cardiovascular medicine. Furthermore, we will cover computational methods for identifying, annotating, and characterizing lncRNAs in the heart, especially ECs.

lncRNAs in Endothelial Cells

Vessels deliver metabolites and oxygen to the tissue and export waste products to sustain the well-being of an organism (Asahara et al., 2011). After tissue injury [e.g., myocardial infarction (MI)], ECs migrate to the site of injury to re-establish the capillary network through a process called “angiogenesis” (Jakobsson et al., 2010; Oka et al., 2014). Furthermore, ECs contribute to the multicellular communications that maintain the balance between the regeneration and dysfunctional or maladaptive healing (Cines et al., 1998; Libby, 2012; Kluge et al., 2013; Eelen et al., 2018). Although advances have been made to understand angiogenesis, the recent emergence of lncRNAs has added another layer of complexity to the genetic network of angiogenesis. To date, a number of lncRNAs are identified and characterized (Table 1) as ECs can be found throughout the human body. For example, MALAT1 regulates endothelial cell function and vessel growth via cell cycle control (Michalik et al., 2014); the histone demethylase JARID1B controls the lncRNA MANTIS, which regulates EC function and vessel growth by binding to the chromatin modifying enzyme BRG1 (Leisegang et al., 2017); and several lncRNAs bind miRNAs to function as miRNA sponges (He et al., 2015, 2017; Huang et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016; Ming et al., 2016; Ma Y. et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017; Zhang B. Y. et al., 2017; Bao et al., 2018).

In addition to the above lncRNAs, we recently reported the presence of an emerging class of lncRNAs called “circular RNAs (circRNAs)” in ECs (Boeckel et al., 2015). CircRNAs are byproducts of splicing events (more specifically, “backsplicing”) of mostly protein-coding genes (Jeck et al., 2013; Jeck and Sharpless, 2014; Boeckel et al., 2015), are stable and localized predominantly in the cytoplasm (Nigro et al., 1991; Cocquerelle et al., 1993). When some circRNAs are knocked down, there are phenotypes observed, which may not be observed when the parental transcripts of circRNAs are knocked down (Boeckel et al., 2015; Gerstner et al., 2016). For example, the hypoxia-regulated circRNA cZNF292, which is derived by backsplicing of ZNF292 protein-coding gene, exhibits proangiogenic activities (Boeckel et al., 2015). Some studies suggest that circRNAs function as miRNA sponges (Hansen et al., 2013; Memczak et al., 2013; Geng et al., 2016; Liu Q. et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016). However, recent comprehensive bioinformatics analysis (Guo et al., 2014) and our biological validation experiments (Boeckel et al., 2015; Weirick et al., 2016b) indicate that circRNAs functioning as miRNA sponges are extremely rare. Along with lncRNAs, more studies are necessary to uncover the functions of circRNAs in ECs.

RNA-seq Data Analysis Using Bioinformatics

There are two major methods of generating libraries for RNA-seq, which are based on poly-A selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA)-depletion. Both methods are aimed at removing rRNAs, which constitute ~80% of total RNA followed by 15% transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and only 5% for all other RNAs, including protein-coding genes and lncRNAs (Lodish et al., 2000). The poly-A selection will result in the identification of protein-coding genes and lncRNAs with poly A tails (~60% of total lncRNAs; Cheng et al., 2005), while the rRNA-depletion can identify the rest of lncRNAs and circRNAs—in addition to those identified in the former method. The presence of circRNAs is detected only with the latter method as circRNAs arise from exons and/or introns that are spliced out, which are devoid of poly A tails.

Analysis of RNA-seq data usually involves a number of common computational steps to obtain the expression profiles of the RNA in a set of samples. At the start of a typical analysis pipeline, reads are trimmed to remove primers and low-quality regions of reads. Next, the reads are aligned to a genome in a “guided alignment.” In the case of the organism with no reference genome, a “de novo assembly” of the transcriptome is performed. However, de novo assembly is more error-prone and difficult to operate, thus we will simply focus on guided alignments. Traditionally, Tophat (Trapnell et al., 2012) has been the most popular aligner, but it is now being supplanted by newer programs (e.g., STAR, HISAT2), which offer greater speed and alignment accuracy (Engström et al., 2013; Conesa et al., 2016; Costa-Silva et al., 2017; Zhang C. et al., 2017).

Similar to protein-coding genes, lncRNAs undergo alternative splicing (AS) to produce isoforms (Deveson et al., 2017; White et al., 2017). The current understanding of AS is mainly based on EST-cDNA sequencing and short-read RNA-seq data. In the second-generation sequencing (e.g., Illumina-based short RNA-seq), long strands of cDNA must be broken into small segments to infer nucleotide sequences by amplification and synthesis (Metzker, 2010), which fall short of detecting intact full-length transcripts. To address this shortcoming, third-generation sequencing (also known as “long-read sequencing”) may be a solution. PacBio RS II (Pacific Biosciences, CA, U.S.A.) is the first commercialized third-generation sequencer, which utilizes a novel single molecule real-time (SMRT) technology (Schadt et al., 2010). Compared to second-generation sequencing, SMRT technology offers long read lengths (up to 92 kb), high consensus accuracy (free of systematic sequencing errors), and low degree of bias (even coverage across G+C content) (Nakano et al., 2017). When this technology is applied to any transcriptome (cDNA) sequencing (e.g., RNA-seq), it is called “Iso-Seq,” which can monitor AS (Abdel-Ghany et al., 2016). With Iso-Seq, the need for transcriptome assembly is eliminated as “one read = one transcript” with each transcript can be read from its 5′-end to poly A tail. Iso-Seq has been applied to various species and tissues (Singh et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2017; Hoang et al., 2017a,b; Jiang et al., 2017; Jo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Kuo et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Xue et al., 2017; Zhang S. J. et al., 2017; Zulkapli et al., 2017; Filichkin et al., 2018) but not yet to ECs.

The largely unbiased manner in which RNA-seq captures information is another interesting aspect of the technology, which enables new findings via re-analysis of published data. For example, most of the RNA-seq studies have been focused on analyzing expression of protein-coding genes. As lncRNA are also present in the data sets, these data offer a rich resource for studying lncRNA expression patterns. We have developed a number of bioinformatics tools to exploit these resources (Gellert et al., 2013; Weirick et al., 2015, 2016b, 2017), including some specifically designed to identify lncRNAs and to associate their expressions in various tissues and cell types, including ECs (e.g., our database ANGIOGENES; Müller et al., 2016). Although ECs can be found throughout the human body, there are only few databases available that contain the expression profiles for genes expressed in ECs (e.g., Causal Biological Network database Boué et al., 2015, dbANGIO4 Savas, 2012, and PubAngioGen Li et al., 2015). Our ANGIOGENE is one of the few that contain the expression profiles of both protein-coding genes and lncRNAs in various ECs based on RNA-seq data. Furthermore, ANGIOGENES covers humans, mice, and zebrafish to allow for the screening of lncRNAs in the positional conserved regions (not necessary sequence-conserved) (Weirick et al., 2015).

There are many transcripts whose sequencing reads are present in RNA-seq data but are not annotated in the public databases, including NONCODE (Zhao et al., 2016), which is one of the hallmark databases for lncRNAs. Our previous study (Weirick et al., 2016a) shows that 77,656 novel isoforms of annotated reference transcripts and 102,848 intergenic transcripts are identified with 58,789 (75.70%) and 101,993 (99.17%) being predicted as non-coding, respectively, from 12 human tissues (Nielsen et al., 2014), while there are 181,434 annotated transcripts (87.13% out of 208,244 transcripts in Ensembl version 77) are expressed in at least one of 12 tissues analyzed. Although we could validate the presence of novel lncRNAs by RT-PCR experiments, many novel lncRNAs contain repetitive elements, such as microsatellites (Bidichandani et al., 1998) and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINE), including ALU elements (Häsler and Strub, 2006). Thus, it is highly recommended to consult the available methods to characterize lncRNAs (Li et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017), including CAGE-seq to annotate the 5′-end of lncRNAs (Hon et al., 2017) and ribo-seq/ribosomal footprinting RNA-seq technology to understand the coding potential (Ruiz-Orera et al., 2014; Ji et al., 2015; Alvarez-Dominguez and Lodish, 2017) before proceeding to more functional experiments.

It is well-known that ECs are heterogeneous populations of cells as their activities and functions differ based on their physiological locations (Aird, 2012; Regan and Aird, 2012; Yuan et al., 2016). In order to understand such heterogeneity of ECs, it is important to perform single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) instead of bulk RNA-seq by using a piece of tissue or those in a culture dish. As the technique for scRNA-seq matures, the immediate problem is the data analysis, especially positioning each cell to a particular cell type in order to organize their molecular signatures matching to the anatomical location in which each cell was isolated from. For example, hearts contain multiple cell types (e.g., cardiomyocytes, ECs, fibroblasts, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells). In regards to ECs, their expression profiles may differ for those contained in the artery and vein. When such profiles are compared to ECs from other tissues (e.g., kidneys, lungs), there are some genes that are expressed at the similar level in all tissues while others are expressed specifically in ECs isolated from a particular tissue. In order to understand such hierarchical organization of cells, their corresponding cell types, and tissues, it is utmost importance that the ontology of each cell must be organized in relation to its corresponding cell type and tissue. To achieve this hierarchical and ontological organization, we recently introduced the usage of logic programing (Weirick et al., 2016b), which was applied to kidneys. Logic programming is a programming paradigm based on formal logic, using a set of logical sentences consisting of facts, rules, and queries (Eklund and Klawonn, 1992). For example, consider a transcript expressed in the renal cortex. The renal cortex is located within kidneys. When sequencing whole kidney under the same condition, the same transcript should be expressed. One could even descend to the level of cell types (e.g., ECs isolated from interlobular arteries, which are located within the kidney cortex). Similarly, all sequences expressed within these ECs are expressed in the kidney. Furthermore, it is well-known that high abundance sequences can overwhelm lower abundance sequences. Thus, logic programming can be useful for integrating RNA-seq data at different hierarchical levels and beyond. This can be accomplished by: (1) modeling the anatomical and experimental relationships; (2) creating rules to define various types of expression characteristics; and (3) using queries to determine expression characteristics of a given RNA. The analysis of RNA-seq data of ECs in the heart for lncRNAs, coupled with logic programming, should help to facilitate the further usage of the available RNA-seq data (e.g., single cell RNA-seq data from the heart) to test various hypotheses that were not originally intended when the data were generated. Such an approach should yield the identification of lncRNAs in a variety of conditions (e.g., expressed in atherosclerotic plaques but not in the healthy artery), which can be further validated in functional studies.

Detection of RNA Editing Patterns From RNA-seq Data

In addition to studying lncRNAs, re-analysis of publicly-available RNA-seq data is also useful for studying RNA editing. RNA editing is a post-transcriptional modification to alter the sequence of RNA molecules (Keegan et al., 2001; Hideyama and Kwak, 2011). The full extent and reasons for RNA editing is largely unknown. However, recent studies show that the editing in exons leads to an amino acid substitutions from altered codons (Alon et al., 2015; Liscovitch-Brauer et al., 2017), whereas editing in 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) may affect binding of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) or microRNAs (miRNAs) thereby modulating RNA stability and/or translation (Keegan et al., 2001). There are two types of RNA editing: adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) and cytidine to uridine (C-to-U). A-to-I is the most common form and occurs through RNA editing enzymes called “adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs),” which convert adenosine in double-stranded RNA into inosine (Savva et al., 2012). When reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA), an inosine is converted to guanine (“G”), which can be identified by comparison to the reference genome. A number of studies have been conducted to detect RNA editing events from RNA-seq data (Bahn et al., 2012; Park et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2012; Ramaswami et al., 2012, 2013; Solomon et al., 2013), including our recent study in ECs (Stellos et al., 2016). Because of the detection from RNA-seq data, several databases for RNA editing events have been constructed to provide evidence for the frequency of RNA editing in various conditions (Kiran and Baranov, 2010; Picardi et al., 2011, 2017; Laganà et al., 2012; Ramaswami and Li, 2014; Solomon et al., 2016; Gong et al., 2017). We recently reported that cathepsin S (CTSS), which encodes a cysteine protease associated with angiogenesis and atherosclerosis, is highly edited (Stellos et al., 2016). Such RNA editing enables the recruitment of stabilizing RBP human antigen R (HuR) to the 3′-UTR of CTSS transcript, thereby controlling CTSS mRNA stability and expression. The RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 levels and the extent of CTSS RNA editing are associated with changes in CTSS levels in patients with coronary artery diseases. Our study highlights the involvement of RNA editing in cardiovascular diseases, which has not yet been investigated (Uchida and Jones, 2018). Our finding was further supported by the recent large-scale, multi-center study analyzing RNA-seq data from the NIH Common Fund's Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) program, which reported that the aorta, coronary, and tibial arteries were the most highly edited tissue type among 53 body sites from 552 individuals analyzed (Tan et al., 2017).

In humans, RNA editing occurs mostly in repetitive Alu regions (Levanon et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2012), which can be found in lncRNAs as lncRNAs can also be edited (Picardi et al., 2014; Szczesniak and Makalowska, 2016; Gong et al., 2017). Although proposed but not tested extensively, the functions of lncRNAs may depend on their conformation (e.g., 3D structures), which can be affected by their primary sequences. This folding process can be influenced by a variety of factors, including (but not limited to) RNA modifications on lncRNAs, such as RNA editing. Given that RNA editing can be readily detected from RNA-seq data, more systematic analysis of RNA editing patterns is necessary, especially targeting lncRNAs in the heart (Uchida and Jones, 2018). For this purpose, several bioinformatics tools are available to detect editing within RNA-seq data, including GIREMI (Zhang and Xiao, 2015), JACUSA (Piechotta et al., 2017), RED (Sun et al., 2016), RED-ML (Xiong et al., 2017), REDItools (Picardi and Pesole, 2013), RES-Scanner (Wang et al., 2016), and our RNAEditor (John et al., 2017).

How Could We Translate the Concept of lncRNAs Into RNA Therapeutics

The one obvious usage of lncRNAs in medicine is using lncRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers as lncRNAs are more cell-type specifically expressed than protein-coding genes (Thurman et al., 2012; Gellert et al., 2013; Necsulea et al., 2014; Weirick et al., 2015). Although some progresses have been made, most of RNA-seq data analyzed so far does not consider lncRNAs due to the reasons mentioned above. Thus, without performing further RNA-seq experiments, it should be feasible to discover lncRNAs that capable of differentiating between diseased and healthy individuals by re-analyzing publicly-available RNA-seq data. For this purpose, bioinformatics tools mentioned above should be useful.

Author Contributions

All authors made contributions to survey the current status of lncRNA research. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the V. V. Cooke Foundation (Kentucky, U.S.A.); grant from the University of Louisville School of Medicine; an EVPRI Internal Research Grant from the Office of the Executive Vice President for Research and Innovation at the University of Louisville; University of Louisville 21st Century University Initiative on Big Data in Medicine; and the startup funding from the Mansbach Family, the Gheens Foundation and other generous supporters at the University of Louisville.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer KT and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

References

Abdel-Ghany, S. E., Hamilton, M., Jacobi, J. L., Ngam, P., Devitt, N., Schilkey, F., et al. (2016). A survey of the sorghum transcriptome using single-molecule long reads. Nat. Commun. 7:11706. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11706

Aird, W. C. (2012). Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006429. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006429

Alon, S., Garrett, S. C., Levanon, E. Y., Olson, S., Graveley, B. R., Rosenthal, J. J., et al. (2015). The majority of transcripts in the squid nervous system are extensively recoded by A-to-I RNA editing. Elife 4:e05198. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05198

Alvarez-Dominguez, J. R., and Lodish, H. F. (2017). Emerging mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function during normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Blood 130, 1965–1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-788695

Archer, K., Broskova, Z., Bayoumi, A. S., Teoh, J. P., Davila, A., Tang, Y., et al. (2015). Long non-coding RNAs as master regulators in cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 23651–23667. doi: 10.3390/ijms161023651

Asahara, T., Kawamoto, A., and Masuda, H. (2011). Concise review: circulating endothelial progenitor cells for vascular medicine. Stem Cells 29, 1650–1655. doi: 10.1002/stem.745

Bahn, J. H., Lee, J. H., Li, G., Greer, C., Peng, G., and Xiao, X. (2012). Accurate identification of A-to-I RNA editing in human by transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res. 22, 142–150. doi: 10.1101/gr.124107.111

Ballantyne, M. D., McDonald, R. A., and Baker, A. H. (2016). lncRNA/MicroRNA interactions in the vasculature. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 99, 494–501. doi: 10.1002/cpt.355

Bao, M. H., Li, G. Y., Huang, X. S., Tang, L., Dong, L. P., and Li, J. M. (2018). Long non-coding RNA LINC00657 acting as miR-590-3p sponge to facilitate low concentration oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced angiogenesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 93, 368–375. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.110650

Bianchessi, V., Badi, I., Bertolotti, M., Nigro, P., D'alessandra, Y., Capogrossi, M. C., et al. (2015). The mitochondrial lncRNA ASncmtRNA-2 is induced in aging and replicative senescence in Endothelial Cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 81, 62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.012

Bidichandani, S. I., Ashizawa, T., and Patel, P. I. (1998). The GAA triplet-repeat expansion in Friedreich ataxia interferes with transcription and may be associated with an unusual DNA structure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62, 111–121. doi: 10.1086/301680

Boeckel, J. N., Jae, N., Heumuller, A. W., Chen, W., Boon, R. A., Stellos, K., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of hypoxia-regulated endothelial circular, RNA. Circ. Res. 117, 884–890. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306319

Boon, R. A., Hofmann, P., Michalik, K. M., Lozano-Vidal, N., Berghäuser, D., Fischer, A., et al. (2016). Long noncoding RNA Meg3 controls endothelial cell aging and function: implications for regenerative angiogenesis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 2589–2591. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.949

Boué, S., Talikka, M., Westra, J. W., Hayes, W., Di Fabio, A., Park, J., et al. (2015). Causal biological network database: a comprehensive platform of causal biological network models focused on the pulmonary and vascular systems. Database (Oxford) 2015:bav030. doi: 10.1093/database/bav030

Boulberdaa, M., Scott, E., Ballantyne, M., Garcia, R., Descamps, B., Angelini, G. D., et al. (2016). A role for the long noncoding RNA SENCR in commitment and function of endothelial cells. Mol. Ther. 24, 978–990. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.41

Busch, A., Eken, S. M., and Maegdefessel, L. (2016). Prospective and therapeutic screening value of non-coding RNA as biomarkers in cardiovascular disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 4:236. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.06

Chan, S. S., Chan, H. H. W., and Kyba, M. (2016). Heterogeneity of Mesp1+ mesoderm revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 474, 469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.139

Chen, L., Yang, W., Guo, Y., Chen, W., Zheng, P., Zeng, J., et al. (2017). Exosomal lncRNA GAS5 regulates the apoptosis of macrophages and vascular endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 12:e0185406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185406

Cheng, B., Furtado, A., and Henry, R. J. (2017). Long-read sequencing of the coffee bean transcriptome reveals the diversity of full-length transcripts. Gigascience 6, 1–13. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix086

Cheng, J., Kapranov, P., Drenkow, J., Dike, S., Brubaker, S., Patel, S., et al. (2005). Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution. Science 308, 1149–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1108625

Cines, D. B., Pollak, E. S., Buck, C. A., Loscalzo, J., Zimmerman, G. A., McEver, R. P., et al. (1998). Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood 91, 3527–3561.

Cocquerelle, C., Mascrez, B., Hétuin, D., and Bailleul, B. (1993). Mis-splicing yields circular RNA molecules. FASEB J. 7, 155–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559

Conesa, A., Madrigal, P., Tarazona, S., Gomez-Cabrero, D., Cervera, A., McPherson, A., et al. (2016). A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 17:13. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0881-8

Conigliaro, A., Costa, V., Lo Dico, A., Saieva, L., Buccheri, S., Dieli, F., et al. (2015). CD90+ liver cancer cells modulate endothelial cell phenotype through the release of exosomes containing H19 lncRNA. Mol. Cancer 14:155. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0426-x

Costa-Silva, J., Domingues, D., and Lopes, F. M. (2017). RNA-Seq differential expression analysis: an extended review and a software tool. PLoS ONE 12:e0190152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190152

Delaughter, D. M., Bick, A. G., Wakimoto, H., McKean, D., Gorham, J. M., Kathiriya, I. S., et al. (2016). Single-cell resolution of temporal gene expression during heart development. Dev. Cell 39, 480–490. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.10.001

Devaux, Y., Zangrando, J., Schroen, B., Creemers, E. E., Pedrazzini, T., Chang, C. P., et al. (2015). Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 415–425. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.55

Deveson, I. W., Hardwick, S. A., Mercer, T. R., and Mattick, J. S. (2017). The dimensions, dynamics, and relevance of the mammalian noncoding transcriptome. Trends Genet. 33, 464–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.04.004

Eelen, G., de Zeeuw, P., Treps, L., Harjes, U., Wong, B. W., and Carmeliet, P. (2018). Endothelial cell metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 98, 3–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2017

Eklund, P., and Klawonn, F. (1992). Neural fuzzy logic programming. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 3, 815–818. doi: 10.1109/72.159071

Engström, P. G., Steijger, T., Sipos, B., Grant, G. R., Kahles, A., Ratsch, G., et al. (2013). Systematic evaluation of spliced alignment programs for RNA-seq data. Nat. Methods 10, 1185–1191. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2722

Ezkurdia, I., Juan, D., Rodriguez, J. M., Frankish, A., Diekhans, M., Harrow, J., et al. (2014). Multiple evidence strands suggest that there may be as few as 19,000 human protein-coding genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 5866–5878. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu309

Filichkin, S. A., Hamilton, M., Dharmawardhana, P. D., Singh, S. K., Sullivan, C., Ben-Hur, A., et al. (2018). Abiotic Stresses modulate landscape of poplar transcriptome via alternative splicing, differential intron retention, and isoform ratio switching. Front. Plant Sci. 9:5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00005

Geisler, S., and Coller, J. (2013). RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 699–712. doi: 10.1038/nrm3679

Gellert, P., Ponomareva, Y., Braun, T., and Uchida, S. (2013). Noncoder: a web interface for exon array-based detection of long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:e20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks877

Geng, H. H., Li, R., Su, Y. M., Xiao, J., Pan, M., Cai, X. X., et al. (2016). The circular RNA Cdr1as promotes myocardial infarction by mediating the regulation of miR-7a on its target genes expression. PLoS ONE 11:e0151753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151753

Gerstner, S., Köhler, W., Heidkamp, G., Purbojo, A., Uchida, S., Ekici, A. B., et al. (2016). Specific phenotype and function of CD56-expressing innate immune cell subsets in human thymus. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100, 1297–1310. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1A0116-038R

Gong, J., Liu, C., Liu, W., Xiang, Y., Diao, L., Guo, A. Y., et al. (2017). LNCediting: a database for functional effects of RNA editing in lncRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D79–D84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw835

Guo, J. U., Agarwal, V., Guo, H., and Bartel, D. P. (2014). Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biol. 15:409. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0409-z

Hansen, T. B., Jensen, T. I., Clausen, B. H., Bramsen, J. B., Finsen, B., Damgaard, C. K., et al. (2013). Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495, 384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993

Häsler, J., and Strub, K. (2006). Alu elements as regulators of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 5491–5497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl706

He, C., Ding, J. W., Li, S., Wu, H., Jiang, Y. R., Yang, W., et al. (2015). The ROLE OF LONG INTERGENIC NONCODINg RNA p21 in vascular endothelial cells. DNA Cell Biol. 34, 677–683. doi: 10.1089/dna.2015.2966

He, C., Yang, W., Yang, J., Ding, J., Li, S., Wu, H., et al. (2017). Long Noncoding RNA MEG3 negatively regulates proliferation and angiogenesis in vascular endothelial cells. DNA Cell Biol. 36, 475–481. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3682

Hideyama, T., and Kwak, S. (2011). When does als start? ADAR2-GluA2 hypothesis for the etiology of sporadic, ALS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4:33. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00033

Hoang, N. V., Furtado, A., Mason, P. J., Marquardt, A., Kasirajan, L., Thirugnanasambandam, P. P., et al. (2017a). A survey of the complex transcriptome from the highly polyploid sugarcane genome using full-length isoform sequencing and de novo assembly from short read sequencing. BMC Genomics 18:395. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3757-8

Hoang, N. V., Furtado, A., O'keeffe, A. J., Botha, F. C., and Henry, R. J. (2017b). Association of gene expression with biomass content and composition in sugarcane. PLoS ONE 12:e0183417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183417

Hon, C. C., Ramilowski, J. A., Harshbarger, J., Bertin, N., Rackham, O. J., Gough, J., et al. (2017). An atlas of human long non-coding RNAs with accurate 5' ends. Nature 543, 199–204. doi: 10.1038/nature21374

Huang, S., Lu, W., Ge, D., Meng, N., Li, Y., Su, L., et al. (2015). A new microRNA signal pathway regulated by long noncoding RNA TGFB2-OT1 in autophagy and inflammation of vascular endothelial cells. Autophagy 11, 2172–2183. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1106663

Huang, T. S., Wang, K. C., Quon, S., Nguyen, P., Chang, T. Y., Chen, Z., et al. (2017). LINC00341 exerts an anti-inflammatory effect on endothelial cells by repressing VCAM1. Physiol. Genomics 49, 339–345. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00132.2016

Iyer, M. K., Niknafs, Y. S., Malik, R., Singhal, U., Sahu, A., Hosono, Y., et al. (2015). The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat. Genet. 47, 199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192

Jakobsson, L., Franco, C. A., Bentley, K., Collins, R. T., Ponsioen, B., Aspalter, I. M., et al. (2010). Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103

Jeck, W. R., and Sharpless, N. E. (2014). Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2890

Jeck, W. R., Sorrentino, J. A., Wang, K., Slevin, M. K., Burd, C. E., Liu, J., et al. (2013). Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 19, 141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112

Ji, Z., Song, R., Regev, A., and Struhl, K. (2015). Many lncRNAs, 5'UTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. Elife 4:e08890. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08890

Jia, P., Cai, H., Liu, X., Chen, J., Ma, J., Wang, P., et al. (2016). Long non-coding RNA H19 regulates glioma angiogenesis and the biological behavior of glioma-associated endothelial cells by inhibiting microRNA-29a. Cancer Lett. 381, 359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.009

Jiang, X., Hall, A. B., Biedler, J. K., and Tu, Z. (2017). Single molecule RNA sequencing uncovers trans-splicing and improves annotations in Anopheles stephensi. Insect Mol. Biol. 26, 298–307. doi: 10.1111/imb.12294

Jo, I. H., Lee, J., Hong, C. E., Lee, D. J., Bae, W., Park, S. G., et al. (2017). Isoform sequencing provides a more comprehensive view of the panax ginseng transcriptome. Genes (Basel) 8:E228. doi: 10.3390/genes8090228

John, D., Weirick, T., Dimmeler, S., and Uchida, S. (2017). RNAEditor: easy detection of RNA editing events and the introduction of editing islands. Brief. Bioinformatics 18, 993–1001. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw087

Josipovic, I., Pflüger, B., Fork, C., Vasconez, A. E., Oo, J. A., Hitzel, J., et al. (2018). Long noncoding RNA LISPR1 is required for S1P signaling and endothelial cell function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 116, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.01.015

Keegan, L. P., Gallo, A., and O'Connell, M. A. (2001). The many roles of an RNA editor. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 869–878. doi: 10.1038/35098584

Kim, M. A., Rhee, J. S., Kim, T. H., Lee, J. S., Choi, A. Y., Choi, B. S., et al. (2017). Alternative Splicing Profile and Sex-Preferential Gene Expression in the Female and Male Pacific abalone haliotis discus hannai. Genes (Basel) 8:E99. doi: 10.3390/genes8030099

King, K. R., Aguirre, A. D., Ye, Y. X., Sun, Y., Roh, J. D., Ng, R. P. Jr., et al. (2017). IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction. Nat. Med. 23, 1481–1487. doi: 10.1038/nm.4428

Kiran, A., and Baranov, P. V. (2010). DARNED: a DAtabase of RNa EDiting in humans. Bioinformatics 26, 1772–1776. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq285

Kluge, M. A., Fetterman, J. L., and Vita, J. A. (2013). Mitochondria and endothelial function. Circ. Res. 112, 1171–1188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300233

Kuo, R. I., Tseng, E., Eory, L., Paton, I. R., Archibald, A. L., and Burt, D. W. (2017). Normalized long read RNA sequencing in chicken reveals transcriptome complexity similar to human. BMC Genomics 18:323. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3691-9

Kurian, L., Aguirre, A., Sancho-Martinez, I., Benner, C., Hishida, T., Nguyen, T. B., et al. (2015). Identification of novel long noncoding RNAs underlying vertebrate cardiovascular development. Circulation 131, 1278–1290. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013303

Laganà, A., Paone, A., Veneziano, D., Cascione, L., Gasparini, P., Carasi, S., et al. (2012). miR-EdiTar: a database of predicted A-to-I edited miRNA target sites. Bioinformatics 28, 3166–3168. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts589

Lander, E. S., Linton, L. M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M. C., Baldwin, J., et al. (2001). Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062

Leisegang, M. S., Fork, C., Josipovic, I., Richter, F. M., Preussner, J., Hu, J., et al. (2017). Long noncoding RNA MANTIS facilitates endothelial angiogenic function. Circulation 136, 65–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026991

Lescroart, F., Wang, X., Lin, X., Swedlund, B., Gargouri, S., Sànchez-Dànes, A., et al. (2018). Defining the earliest step of cardiovascular lineage segregation by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 359, 1177–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4174

Levanon, E. Y., Eisenberg, E., Yelin, R., Nemzer, S., Hallegger, M., Shemesh, R., et al. (2004). Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/nbt996

Li, A., Zhang, J., and Zhou, Z. (2014). PLEK: a tool for predicting long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs based on an improved k-mer scheme. BMC Bioinformatics 15:311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-311

Li, K., Blum, Y., Verma, A., Liu, Z., Pramanik, K., Leigh, N. R., et al. (2010). A noncoding antisense RNA in tie-1 locus regulates tie-1 function in vivo. Blood 115, 133–139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242180

Li, L., Wang, M., Mei, Z., Cao, W., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., et al. (2017a). lncRNAs HIF1A-AS2 facilitates the up-regulation of HIF-1alpha by sponging to miR-153-3p, whereby promoting angiogenesis in HUVECs in hypoxia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 96, 165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.113

Li, P., Liu, Y., Wang, H., He, Y., Wang, X., He, Y., et al. (2015). PubAngioGen: a database and knowledge for angiogenesis and related diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D963–D967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1139

Li, W., Wang, R., Ma, J. Y., Wang, M., Cui, J., Wu, W. B., et al. (2017b). A Human long non-coding RNA ALT1 controls the cell cycle of vascular endothelial cells via ACE2 and cyclin D1 pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 43, 1152–1167. doi: 10.1159/000481756

Liao, B., Chen, R., Lin, F., Mai, A., Chen, J., Li, H., et al. (2018). Long noncoding RNA HOTTIP promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration via activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 119, 2797–2805. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26448

Libby, P. (2012). Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2045–2051. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179705

Liscovitch-Brauer, N., Alon, S., Porath, H. T., Elstein, B., Unger, R., Ziv, T., et al. (2017). Trade-off between transcriptome plasticity and genome evolution in cephalopods. Cell 169, 191–202.e111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.025

Liu, H. Z., Wang, Q. Y., Zhang, Y., Qi, D. T., Li, M. W., Guo, W. Q., et al. (2016). Pioglitazone up-regulates long non-coding RNA MEG3 to protect endothelial progenitor cells via increasing HDAC7 expression in metabolic syndrome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 78, 101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.01.001

Liu, J. Y., Yao, J., Li, X. M., Song, Y. C., Wang, X. Q., Li, Y. J., et al. (2014). Pathogenic role of lncRNA-MALAT1 in endothelial cell dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Cell Death Dis. 5:e1506. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.466

Liu, Q., Zhang, X., Hu, X., Dai, L., Fu, X., Zhang, J., et al. (2016). Circular RNA related to the chondrocyte ECM regulates MMP13 expression by Functioning as a MiR-136 'Sponge' in human cartilage degradation. Sci. Rep. 6:22572. doi: 10.1038/srep22572

Liu, S. J., Horlbeck, M. A., Cho, S. W., Birk, H. S., Malatesta, M., He, D., et al. (2017). CRISPRi-based genome-scale identification of functional long noncoding RNA loci in human cells. Science 355:aah7111. doi: 10.1126/science.aah7111

Lodish, H., Berk, A., Zipursky, L., Matsudaira, P., Baltimore, D., and Darnell, J. (2000). Molecular Cell Biology, 4th Edn. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Lorenzen, J. M., and Thum, T. (2016). Long noncoding RNAs in kidney and cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 360–373. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.51

Lu, W., Huang, S. Y., Su, L., Zhao, B. X., and Miao, J. Y. (2016). Long noncoding RNA LOC100129973 suppresses apoptosis by targeting miR-4707-5p and miR-4767 in vascular endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 6:21620. doi: 10.1038/srep21620

Lv, L., Qi, H., Guo, X., Ni, Q., Yan, Z., and Zhang, L. (2017). Long Noncoding RNA uc001pwg.1 Is downregulated in neointima in arteriovenous fistulas and mediates the function of endothelial cells derived from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017:4252974. doi: 10.1155/2017/4252974

Ma, X., Li, Z., Li, T., Zhu, L., Li, Z., and Tian, N. (2017). Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR enhances angiogenesis by induction of VEGFA expression in glioma cells and transmission to endothelial cells via glioma cell derived-extracellular vesicles. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9, 5012–5021.

Ma, Y., Wang, P., Xue, Y., Qu, C., Zheng, J., Liu, X., et al. (2017). PVT1 affects growth of glioma microvascular endothelial cells by negatively regulating miR-186. Tumour Biol. 39:1010428317694326. doi: 10.1177/1010428317694326

Man, H. S. J., Sukumar, A. N., Lam, G. C., Turgeon, P. J., Yan, M. S., Ku, K. H., et al. (2018). Angiogenic patterning by STEEL, an endothelial-enriched long noncoding RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2401–2406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715182115

Memczak, S., Jens, M., Elefsinioti, A., Torti, F., Krueger, J., Rybak, A., et al. (2013). Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495, 333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928

Mercer, T. R., Gerhardt, D. J., Dinger, M. E., Crawford, J., Trapnell, C., Jeddeloh, J. A., et al. (2011). Targeted RNA sequencing reveals the deep complexity of the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 99–104. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2024

Metzker, M. L. (2010). Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626

Miao, Y., Ajami, N. E., Huang, T. S., Lin, F. M., Lou, C. H., Wang, Y. T., et al. (2018). Enhancer-associated long non-coding RNA LEENE regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase and endothelial function. Nat. Commun. 9:292. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02113-y

Michalik, K. M., You, X., Manavski, Y., Doddaballapur, A., Zörnig, M., Braun, T., et al. (2014). Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates endothelial cell function and vessel growth. Circ. Res. 114, 1389–1397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303265

Ming, G. F., Wu, K., Hu, K., Chen, Y., and Xiao, J. (2016). NAMPT regulates senescence, proliferation, and migration of endothelial progenitor cells through the SIRT1 AS lncRNA/miR-22/SIRT1 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478, 1382–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.133

Müller, R., Weirick, T., John, D., Militello, G., Chen, W., Dimmeler, S., et al. (2016). ANGIOGENES: knowledge database for protein-coding and noncoding RNA genes in endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 6:32475. doi: 10.1038/srep32475

Nakano, K., Shiroma, A., Shimoji, M., Tamotsu, H., Ashimine, N., Ohki, S., et al. (2017). Advantages of genome sequencing by long-read sequencer using SMRT technology in medical area. Hum. Cell 30, 149–161. doi: 10.1007/s13577-017-0168-8

Necsulea, A., Soumillon, M., Warnefors, M., Liechti, A., Daish, T., Zeller, U., et al. (2014). The evolution of lncRNA repertoires and expression patterns in tetrapods. Nature 505, 635–640. doi: 10.1038/nature12943

Neumann, P., Jaé, N., Knau, A., Glaser, S. F., Fouani, Y., Rossbach, O., et al. (2018). The lncRNA GATA6-AS epigenetically regulates endothelial gene expression via interaction with LOXL2. Nat. Commun. 9:237. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02431-1

Nielsen, M. M., Tehler, D., Vang, S., Sudzina, F., Hedegaard, J., Nordentoft, I., et al. (2014). Identification of expressed and conserved human noncoding RNAs. RNA 20, 236–251. doi: 10.1261/rna.038927.113

Nigro, J. M., Cho, K. R., Fearon, E. R., Kern, S. E., Ruppert, J. M., Oliner, J. D., et al. (1991). Scrambled exons. Cell 64, 607–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90244-S

Oka, T., Akazawa, H., Naito, A. T., and Komuro, I. (2014). Angiogenesis and cardiac hypertrophy: maintenance of cardiac function and causative roles in heart failure. Circ. Res. 114, 565–571. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300507

Ounzain, S., Burdet, F., Ibberson, M., and Pedrazzini, T. (2015a). Discovery and functional characterization of cardiovascular long noncoding RNAs. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 89, 17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.09.013

Ounzain, S., Micheletti, R., Arnan, C., Plaisance, I., Cecchi, D., Schroen, B., et al. (2015b). CARMEN, a human super enhancer-associated long noncoding RNA controlling cardiac specification, differentiation and homeostasis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 89, 98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.09.016

Ounzain, S., Micheletti, R., Beckmann, T., Schroen, B., Alexanian, M., Pezzuto, I., et al. (2015c). Genome-wide profiling of the cardiac transcriptome after myocardial infarction identifies novel heart-specific long non-coding RNAs. Eur. Heart J. 36, 353a–368a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu180

Ounzain, S., Pezzuto, I., Micheletti, R., Burdet, F., Sheta, R., Nemir, M., et al. (2014). Functional importance of cardiac enhancer-associated noncoding RNAs in heart development and disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 76, 55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.009

Park, E., Williams, B., Wold, B. J., and Mortazavi, A. (2012). RNA editing in the human ENCODE RNA-seq data. Genome Res. 22, 1626–1633. doi: 10.1101/gr.134957.111

Peng, Y., Meng, K., Jiang, L., Zhong, Y., Yang, Y., Lan, Y., et al. (2017). Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-induced HOTAIR activation promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration in atherosclerosis. Biosci. Rep. 37:BSR20170351. doi: 10.1042/BSR20170351

Peng, Z., Cheng, Y., Tan, B. C., Kang, L., Tian, Z., Zhu, Y., et al. (2012). Comprehensive analysis of RNA-Seq data reveals extensive RNA editing in a human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 253–260. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2122

Philippen, L. E., Dirkx, E., da Costa-Martins, P. A., and De Windt, L. J. (2015). Non-coding RNA in control of gene regulatory programs in cardiac development and disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 89, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.03.014

Picardi, E., D'erchia, A. M., Gallo, A., Montalvo, A., and Pesole, G. (2014). Uncovering RNA editing sites in long non-coding RNAs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2:64. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00064

Picardi, E., D'erchia, A. M., Lo Giudice, C., and Pesole, G. (2017). REDIportal: a comprehensive database of A-to-I RNA editing events in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D750–D757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw767

Picardi, E., and Pesole, G. (2013). REDItools: high-throughput RNA editing detection made easy. Bioinformatics 29, 1813–1814. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt287

Picardi, E., Regina, T. M., Verbitskiy, D., Brennicke, A., and Quagliariello, C. (2011). REDIdb: an upgraded bioinformatics resource for organellar RNA editing sites. Mitochondrion 11, 360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.10.005

Piechotta, M., Wyler, E., Ohler, U., Landthaler, M., and Dieterich, C. (2017). JACUSA: site-specific identification of RNA editing events from replicate sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 18:7. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1432-8

Puthanveetil, P., Chen, S., Feng, B., Gautam, A., and Chakrabarti, S. (2015). Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates hyperglycaemia induced inflammatory process in the endothelial cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 19, 1418–1425. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12576

Qiu, G. Z., Tian, W., Fu, H. T., Li, C. P., and Liu, B. (2016). Long noncoding RNA-MEG3 is involved in diabetes mellitus-related microvascular dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 471, 135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.164

Ramaswami, G., and Li, J. B. (2014). RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D109–D113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt996

Ramaswami, G., Lin, W., Piskol, R., Tan, M. H., Davis, C., and Li, J. B. (2012). Accurate identification of human Alu and non-Alu RNA editing sites. Nat. Methods 9, 579–581. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1982

Ramaswami, G., Zhang, R., Piskol, R., Keegan, L. P., Deng, P., O'connell, M. A., et al. (2013). Identifying RNA editing sites using RNA sequencing data alone. Nat. Methods 10, 128–132. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2330

Regan, E. R., and Aird, W. C. (2012). Dynamical systems approach to endothelial heterogeneity. Circ. Res. 111, 110–130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261701

Rizki, G., and Boyer, L. A. (2015). Lncing epigenetic control of transcription to cardiovascular development and disease. Circ. Res. 117, 192–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.304156

Ruan, W., Zhao, F., Zhao, S., Zhang, L., Shi, L., and Pang, T. (2018). Knockdown of long noncoding RNA MEG3 impairs VEGF-stimulated endothelial sprouting angiogenesis via modulating VEGFR2 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Gene 649, 32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.072

Ruiz-Orera, J., Messeguer, X., Subirana, J. A., and Alba, M. M. (2014). Long non-coding RNAs as a source of new peptides. Elife 3:e03523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03523

Sallam, T., Sandhu, J., and Tontonoz, P. (2018). Long noncoding RNA discovery in cardiovascular disease: decoding form to function. Circ. Res. 122, 155–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311802

Savas, S. (2012). A curated database of genetic markers from the angiogenesis/VEGF pathway and their relation to clinical outcome in human cancers. Acta Oncol. 51, 243–246. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.636758

Savva, Y. A., Rieder, L. E., and Reenan, R. A. (2012). The ADAR protein family. Genome Biol. 13:252. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-12-252

Schadt, E. E., Turner, S., and Kasarskis, A. (2010). A window into third-generation sequencing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, R227–R240. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq416

Shan, K., Jiang, Q., Wang, X. Q., Wang, Y. N., Yang, H., Yao, M. D., et al. (2016). Role of long non-coding RNA-RNCR3 in atherosclerosis-related vascular dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 7:e2248. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.145

Singh, N., Sahu, D. K., Chowdhry, R., Mishra, A., Goel, M. M., Faheem, M., et al. (2016). IsoSeq analysis and functional annotation of the infratentorial ependymoma tumor tissue on PacBio RSII platform. Meta Gene 7, 70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2015.11.004

Skelly, D. A., Squiers, G. T., McLellan, M. A., Bolisetty, M. T., Robson, P., Rosenthal, N. A., et al. (2018). Single-cell transcriptional profiling reveals cellular diversity and intercommunication in the mouse heart. Cell Rep. 22, 600–610. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.072

Solomon, O., Eyal, E., Amariglio, N., Unger, R., and Rechavi, G. (2016). e23D: database and visualization of A-to-I RNA editing sites mapped to 3D protein structures. Bioinformatics 32, 2213–2215. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw204

Solomon, O., Oren, S., Safran, M., Deshet-Unger, N., Akiva, P., Jacob-Hirsch, J., et al. (2013). Global regulation of alternative splicing by adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR). RNA 19, 591–604. doi: 10.1261/rna.038042.112

Stellos, K., Gatsiou, A., Stamatelopoulos, K., Perisic Matic, L., John, D., Lunella, F. F., et al. (2016). Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing controls cathepsin S expression in atherosclerosis by enabling HuR-mediated post-transcriptional regulation. Nat. Med. 22, 1140–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm.4172

Sun, J. Y., Zhao, Z. W., Li, W. M., Yang, G., Jing, P. Y., Li, P., et al. (2017). Knockdown of MALAT1 expression inhibits HUVEC proliferation by upregulation of miR-320a and downregulation of FOXM1 expression. Oncotarget 8, 61499–61509. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18507

Sun, Y., Li, X., Wu, D., Pan, Q., Ji, Y., Ren, H., et al. (2016). RED: a Java-MySQL software for identifying and visualizing RNA editing sites using rule-based and statistical filters. PLoS ONE 11:e0150465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150465

Szcześniak, M. W., and Makaĺowska, I. (2016). lncRNA-RNA interactions across the human transcriptome. PLoS ONE 11:e0150353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150353

Tan, M. H., Li, Q., Shanmugam, R., Piskol, R., Kohler, J., Young, A. N., et al. (2017). Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature 550, 249–254. doi: 10.1038/nature24041

Tang, Y., Jin, X., Xiang, Y., Chen, Y., Shen, C. X., Zhang, Y. C., et al. (2015). The lncRNA MALAT1 protects the endothelium against ox-LDL-induced dysfunction via upregulating the expression of the miR-22-3p target genes CXCR2 and AKT. FEBS Lett. 589, 3189–3196. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.046

Thurman, R. E., Rynes, E., Humbert, R., Vierstra, J., Maurano, M. T., Haugen, E., et al. (2012). The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature 489, 75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232

Trapnell, C., Roberts, A., Goff, L., Pertea, G., Kim, D., Kelley, D. R., et al. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016

Uchida, S., and Bolli, R. (2017). Short and long noncoding RNAs regulate the epigenetic status of cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7262. [Epub ahead of print].

Uchida, S., and Dimmeler, S. (2015). Long noncoding RNAs in cardiovascular diseases. Circ. Res. 116, 737–750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.302521

Uchida, S., and Jones, S. P. (2018). RNA Editing: Unexplored Opportunities in the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 122, 399–401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312512

Viereck, J., and Thum, T. (2017). Long Noncoding RNAs in pathological cardiac remodeling. Circ. Res. 120, 262–264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310174

Wang, J., Li, Z., Lei, M., Fu, Y., Zhao, J., Ao, M., et al. (2017a). Integrated DNA methylome and transcriptome analysis reveals the ethylene-induced flowering pathway genes in pineapple. Sci. Rep. 7:17167. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17460-5

Wang, J., Yao, L., Li, B., Meng, Y., Ma, X., and Wang, H. (2017b). Single-molecule long-read transcriptome dataset of halophyte halogeton glomeratus. Front. Genet. 8:197. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00197

Wang, M., Wang, P., Liang, F., Ye, Z., Li, J., Shen, C., et al. (2018). A global survey of alternative splicing in allopolyploid cotton: landscape, complexity and regulation. New Phytol. 217, 163–178. doi: 10.1111/nph.14762

Wang, Z., Lian, J., Li, Q., Zhang, P., Zhou, Y., Zhan, X., et al. (2016). RES-Scanner: a software package for genome-wide identification of RNA-editing sites. Gigascience 5:37. doi: 10.1186/s13742-016-0143-4

Weirick, T., John, D., Dimmeler, S., and Uchida, S. (2015). C-It-Loci: a knowledge database for tissue-enriched loci. Bioinformatics 31, 3537–3543. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv410

Weirick, T., John, D., and Uchida, S. (2017). Resolving the problem of multiple accessions of the same transcript deposited across various public databases. Brief. Bioinformatics 18, 226–235. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw017

Weirick, T., Militello, G., Müller, R., John, D., Dimmeler, S., and Uchida, S. (2016a). The identification and characterization of novel transcripts from RNA-seq data. Brief. Bioinformatics 17, 678–685. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv067

Weirick, T., Militello, G., Ponomareva, Y., John, D., Döring, C., Dimmeler, S., et al. (2016b). Logic programming to infer complex RNA expression patterns from RNA-seq data. Brief. Bioinform. 19, 199–209. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw117

White, E. J., Matsangos, A. E., and Wilson, G. M. (2017). AUF1 regulation of coding and noncoding RNA. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 8:e1393. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1393

Xiong, H., Liu, D., Li, Q., Lei, M., Xu, L., Wu, L., et al. (2017). RED-ML: a novel, effective RNA editing detection method based on machine learning. Gigascience 6, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix012

Xue, X. Y., Majerciak, V., Uberoi, A., Kim, B. H., Gotte, D., Chen, X., et al. (2017). The full transcription map of mouse papillomavirus type 1 (MmuPV1) in mouse wart tissues. PLoS Pathog. 13:e1006715. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006715

Yan, B., Yao, J., Liu, J. Y., Li, X. M., Wang, X. Q., Li, Y. J., et al. (2015). lncRNA-MIAT regulates microvascular dysfunction by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Circ. Res. 116, 1143–1156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305510

Yuan, L., Chan, G. C., Beeler, D., Janes, L., Spokes, K. C., Dharaneeswaran, H., et al. (2016). A role of stochastic phenotype switching in generating mosaic endothelial cell heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 7:10160. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10160

Zhan, R., Xu, K., Pan, J., Xu, Q., Xu, S., and Shen, J. (2017). Long noncoding RNA MEG3 mediated angiogenesis after cerebral infarction through regulating p53/NOX4 axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 490, 700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.104

Zhang, B. Y., Jin, Z., and Zhao, Z. (2017). Long intergenic noncoding RNA 00305 sponges miR-136 to regulate the hypoxia induced apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 94, 238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.099

Zhang, C., Zhang, B., Lin, L. L., and Zhao, S. (2017). Evaluation and comparison of computational tools for RNA-seq isoform quantification. BMC Genomics 18:583. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4002-1

Zhang, Q., and Xiao, X. (2015). Genome sequence-independent identification of RNA editing sites. Nat. Methods 12, 347–350. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3314

Zhang, S. J., Wang, C., Yan, S., Fu, A., Luan, X., Li, Y., et al. (2017). Isoform evolution in primates through independent combination of alternative RNA processing events. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2453–2468. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx212

Zhao, Y., Li, H., Fang, S., Kang, Y., Wu, W., Hao, Y., et al. (2016). NONCODE 2016: an informative and valuable data source of long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D203–D208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1252

Zhao, Z., Liu, B., Li, B., Song, C., Diao, H., Guo, Z., et al. (2017). Inhibition of long noncoding RNA IGF2AS promotes angiogenesis in type 2 diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 92, 445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.039

Zheng, Q., Bao, C., Guo, W., Li, S., Chen, J., Chen, B., et al. (2016). Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat. Commun. 7:11215. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11215

Keywords: bioinformatics, databases, lncRNAs, miRNAs, RNA-seq, RNA editing, RNA modifications

Citation: Weirick T, Militello G and Uchida S (2018) Long Non-coding RNAs in Endothelial Biology. Front. Physiol. 9:522. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00522

Received: 01 March 2018; Accepted: 24 April 2018;

Published: 14 May 2018.

Edited by:

Anna Zampetaki, King's College London School of Medicine, United KingdomReviewed by:

Konstantinos Theofilatos, King's College London, United KingdomSarah Raye Langley, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Copyright © 2018 Weirick, Militello and Uchida. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shizuka Uchida, aGVhcnQubG5jcm5hQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Tyler Weirick

Tyler Weirick Giuseppe Militello

Giuseppe Militello Shizuka Uchida

Shizuka Uchida