- School of Physics, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

We study the two-pion Hanbury Brown–Twiss correlation functions for a partially coherent source constructed with the emission points and momenta of the identical pions generated by a multiphase transport model. A coherent emission length is introduced, the effects of which on the two-pion interferometry results in central Au-Au collisions at

1 Introduction

Pion Hanbury Brown–Twiss (HBT) interferometry has been widely used in high-energy collisions to detect the space-time structure of particle-emitting sources [1–6]. Since HBT correlation disappears for coherent emission of bosons, the intercept of the pion HBT correlation function near-zero relative momentum is sensitive to the coherence of the particle emission and can also be affected by many other factors [1–6]. Recent measurements of two-pion HBT correlations in p-p, p-Pb, and Pb-Pb collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) [7–11] and those of Au-Au and Cu-Cu collisions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) [12–16] showed that the intercepts of the two-pion correlation functions near zero relative momentum are substantially less than 2. These observations and the suppression of the multi-pion correlation functions observed in the Pb-Pb collisions at the LHC [11, 17] indicate that the particle-emitting sources are perhaps partially coherent. However, there is no widely accepted explanation for these observations.

In Ref. 18, Bary and Zhang et al. analyzed the two- and multi-pion HBT correlations in a granular source with coherent pion emission droplets. They assumed that pions are emitted randomly from the evolving droplets in the granular source and that pion emissions from one droplet are coherent because of the closed emission points. They found that the intercepts of the pion HBT correlation functions at the relative momenta near zero have substantial decreases in the coherent granular source model. However, more detailed studies are needed to explain the experimental data. In this article, we study the two-pion HBT correlation functions for the partially coherent sources constructed with emission points and momenta of identical pions generated by a multiphase transport (AMPT) model [19, 20] for high-energy A-A and p-p collisions. Compared to a bulk evolution model, the AMPT as a cascade model can provide more detailed information about the particle production, interaction, and propagation in the source. It has been extensively employed in the simulation of high-energy p-p, p-A, and A-A collisions at the RHIC and LHC [19–32]. This study is our first step toward better understanding the relationship between HBT correlation and particle emission in the source.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present a brief introduction to the AMPT model and a description of the correlation function calculation for partially coherent sources. The HBT interferometry results for the sources in high-energy A-A and p-p collisions are presented in Section 3. Finally, a summary and discussion are provided in Section 4.

2 Model and Correlation Function Calculations

2.1 AMPT Model

The AMPT model has been extensively employed in the simulation of high-energy p-p, p-A, and A-A collisions at the RHIC and LHC [19–32]. The essential components of the AMPT model are initialization, parton transport, the hadronization mechanism, and hadron transport [20]. The initialization of the collisions is performed using the HIJING model [33]. Parton transport and hadron transport are described by the ZPC parton cascade model [34] and the ART model [35], respectively. In the string melting version of the AMPT model, which is used in this study, partons are hadronized by the quark coalescence mechanism [19, 20]. The model parameter μ of parton screening mass is taken to be 2.2814 fm−1, and the strong coupling constant αs is taken to be 0.47, corresponding to a parton-scattering cross section 6 mb [20]. The different values of the parton cross section were also used in analyzing the flow harmonics vn (n = 2, 3) by comparing them with experimental data [19–24]. Because of partonic scattering, the v2 results are great in the string melting AMPT model with a large parton scattering cross section [19, 20].

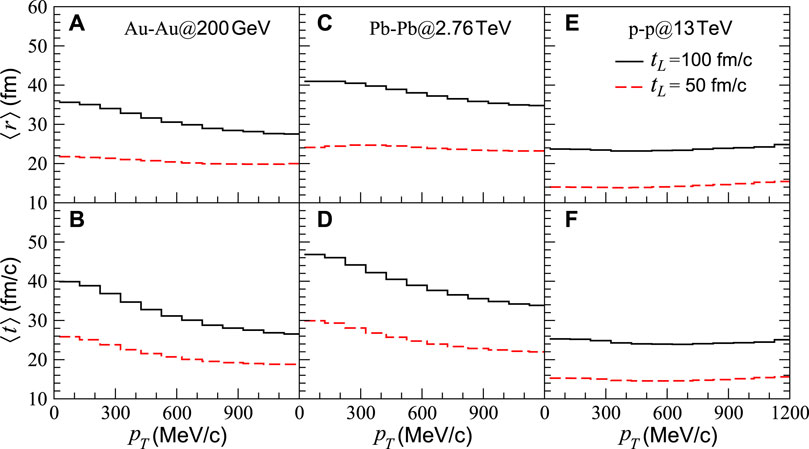

With the AMPT model, we can obtain the space-time emission points and momenta of identical pions and then calculate pion correlation functions. In Figure 1, we show the average spatial and temporal coordinates of the pion emissions versus pion transverse momentum in central Au-Au collisions at the RHIC energy

FIGURE 1. (A,B) Average spatial and temporal coordinates of pion emissions vs. pion transverse momentum in Au-Au collisions at

For the A-A collisions, both the average values of the spatial and temporal emission coordinates for tL = 100 fm/c decrease with increasing transverse momentum, and the average of spatial coordinates for tL = 50 fm/c is almost independent of transverse momentum. The average values of the spatial and temporal emission coordinates for tL = 50 fm/c are smaller than those for tL = 100 fm/c, and the average values of the spatial and temporal coordinates of the Pb-Pb collisions are larger than those of the Au-Au collisions. Compared to the average values in the A-A collisions, the results in the p-p collisions are smaller, and their variations with transverse momentum are flatter.

2.2 Calculation of Two-Pion Correlation Function

The two-pion HBT correlation function C(p1, p2) is defined as the ratio of the two-pion momentum distribution P(p1, p2) to the product of the single-pion momentum distribution P(p1)P(p2):

For a chaotic pion-emitting source, P(pi) (i = 1, 2) and P(p1, p2) can be expressed as [2]

where A(pi, Xi) is the magnitude of the amplitude for emitting a pion with momentum pi at the four-coordinate Xi, and

where pi is the four-momentum.

For small relative momentum, q = p1 − p2, we can use A(K, Xi), instead of A(pj, Xi) (i, j = 1, 2) [smoothed approximation, K = (p1 + p2)/2]. Then,

In high-energy nucleus–nucleus and proton–proton collisions at the RHIC and LHC, the systems are initially compressed in the beam direction (longitudinal or z direction) and then expanded longitudinally and transversely. Considering that the two pions emitted within a small longitudinal distance may be related, we assume that the pion emissions are coherent for the two pions with a relative longitudinal position

where

and

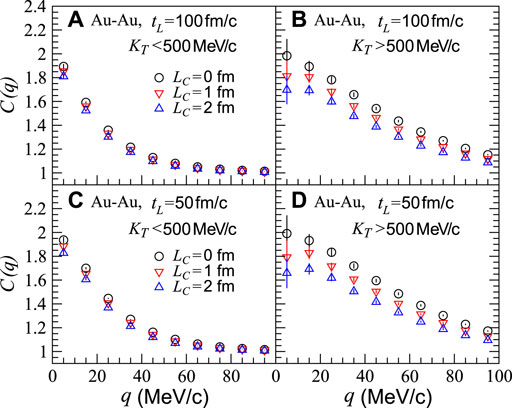

We show in Figures 2A,B the two-pion correlation functions C(q) for the pion-emitting sources with the coherent emission length LC = 0 (chaotic source), 1, and 2 fm in the Au-Au collisions at

FIGURE 2. Two-pion correlation functions C(q) for pion-emitting sources with different coherent emission length values, LC, in the transverse momentum ranges of KT < 500 MeV/c and KT > 500 MeV/c, respectively, in Au-Au collisions at

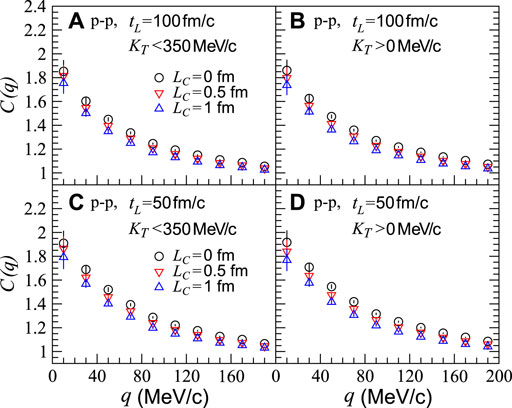

In high-energy p-p collisions, the statistics of the pions with high transverse momenta are smaller than those of the Au-Au collisions. In Figures 3A,B, we show the two-pion correlation functions in the p-p collisions at

FIGURE 3. Two-pion correlation functions C(q) for pion-emitting sources with different coherent emission length values, LC, in the transverse momentum ranges of KT < 350 MeV/c and KT > 0 MeV/c, respectively, in p-p collisions at

3 Interferometry Results

In two-pion HBT analyses, the usual correlation function formula is

where Rout, Rside, and Rlong are the Bertsch–Pratt variables [36, 37], which denote the components of the relative momentum q in the transverse “out” (parallel to the transverse momentum of the pion pair KT), transverse “side” (in the transverse plane and perpendicular to KT), and longitudinal (“long”) directions in the longitudinally comoving system (LCMS) frame [6], respectively. In Eq. 9, λ is the chaoticity parameter and Rout, Rside, and Rlong are the HBT radii in the out, side, and long directions, respectively. By fitting the calculated three-dimensional correlation functions for the partially coherent sources with Eq. 9, one can obtain the values of the HBT radii and the chaoticity parameter.

3.1 Au-Au Collisions

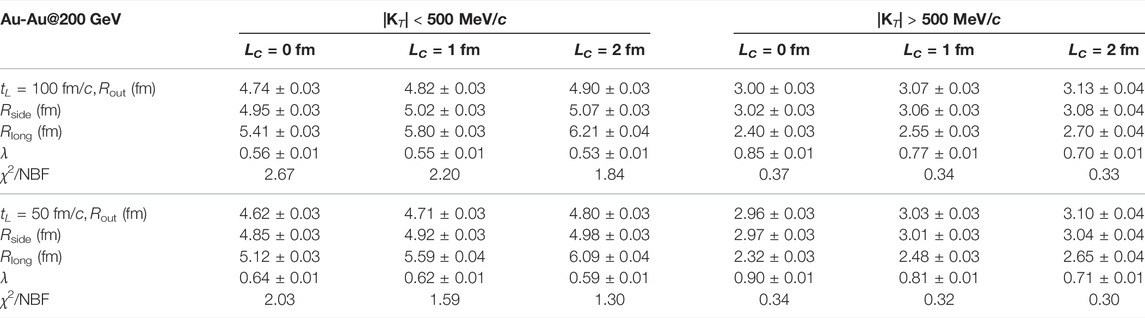

In Table 1, we present the fitted results of the HBT radii (Rout, Rside, and Rlong) and the chaoticity parameter λ in Eq. 9, for the sources with coherent emission lengths LC = 0, 1, and 2 fm in central Au-Au collisions at

TABLE 1. Fitted results of HBT radii and λ parameter in Eq. 9 for sources with LC = 0, 1, and 2 fm in central Au-Au collisions at

One can see that the HBT radii increase slightly with increasing LC, and the λ parameter decreases with increasing LC. The HBT radii in the higher transverse momentum range are smaller than those in the lower transverse momentum range because the average source sizes are small at high transverse momenta (Figure 1A). In the lower transverse momentum range, the λ results are smaller than those in the higher transverse momentum range. The main reason is that the scattering interactions in the particle-emitting source reduce the intercepts of the correlation functions[20, 38], and this influence is weaker in the higher transverse momentum range where most pions are emitted early. The results of χ2/NBF indicate that the sources in the lower transverse momentum range are more different from a Gaussian source. For the sources with tL = 50 fm/c, the HBT radii are slightly smaller than those of the sources with tL = 100 fm/c. However, the λ results are slightly larger than those of the sources with tL = 100 fm/c. It should be noted that the effect of coherent emission length on the chaoticity parameter λ becomes increasingly significant for sources with a smaller tL value, which reduces the λ value by approximately 11% (for LC = 1 fm) to 24% (for LC = 2 fm) in the higher transverse momentum range.

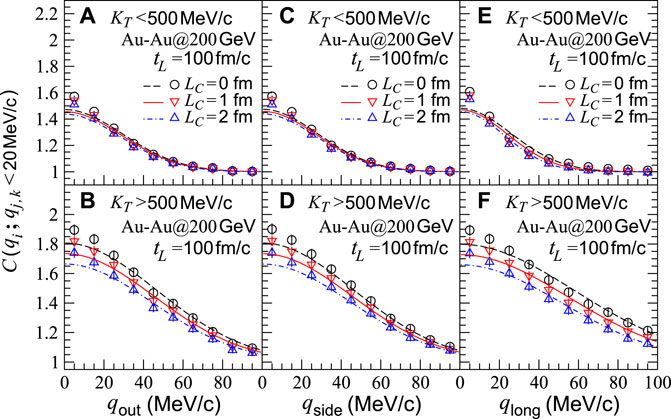

We show in Figure 4 the projections of the two-pion correlation functions C(qout, qside, qlong) in the out, side, and long directions, for the sources in central Au-Au collisions at

FIGURE 4. Two-pion correlation functions with respect to relative momenta qi,j,k (i, j, and k = out, side, and long) for sources in central Au-Au collisions at

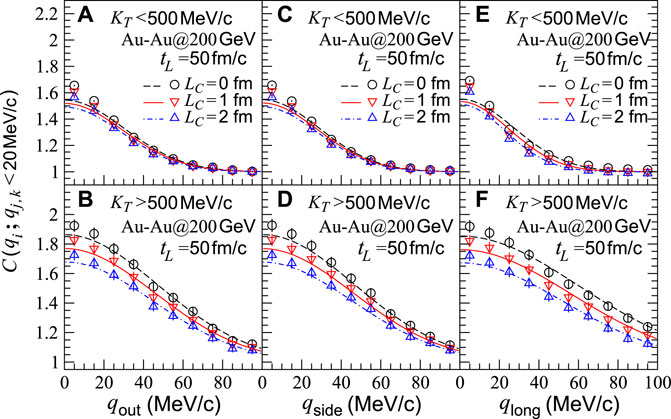

We show in Figure 5 the projections of the two-pion correlation functions C(qout, qside, qlong) in the out, side, and long directions, for the sources in central Au-Au collisions at

FIGURE 5. Two-pion correlation functions with respect to relative momenta qi,j,k (i, j, and k = out, side, and long) for sources in central Au-Au collisions at

3.2 Pb-Pb Collisions

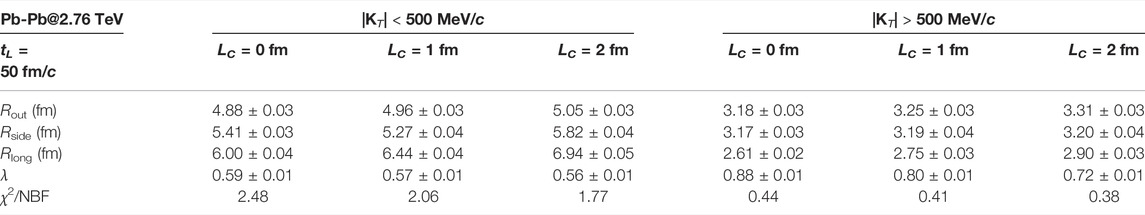

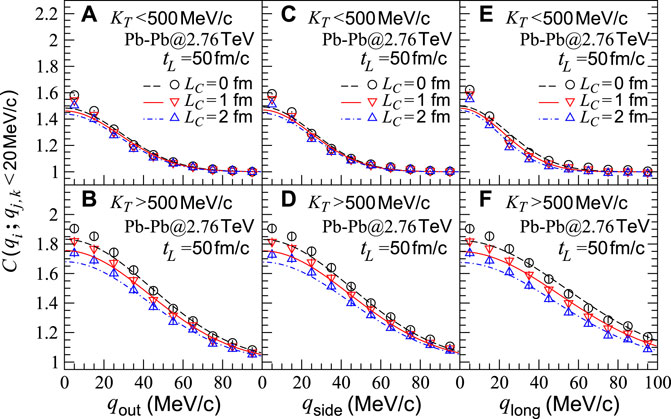

In Table 2, we present the fitted results of the HBT radii (Rout, Rside, and Rlong) and chaoticity parameter λ in Eq. 9 for the sources with the coherent emission lengths LC = 0, 1, and 2 fm in central Pb-Pb collisions at

TABLE 2. Fitted results of HBT radii and λ parameter in Eq. 9 for sources with LC = 0, 1, and 2 fm in central Pb-Pb collisions at

FIGURE 6. Two-pion correlation functions with respect to relative momenta qi,j,k (i, j, and k = out, side, and long) for sources in central Pb-Pb collisions at

3.3 p-p Collisions

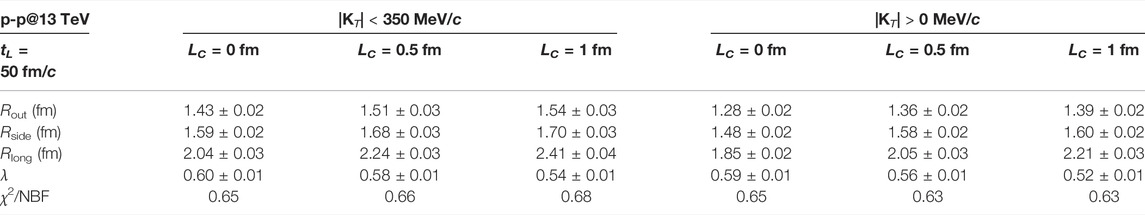

In Table 3, we present the fitted results of the HBT radii (Rout, Rside, and Rlong) and the chaoticity parameter λ in Eq. 9, for the sources with the coherent emission lengths LC = 0, 0.5, and 1 fm in p-p collisions at

TABLE 3. Fitted results of HBT radii and λ parameter in Eq. 9 for sources with LC = 0, 0.5, and 1 fm in p-p collisions at

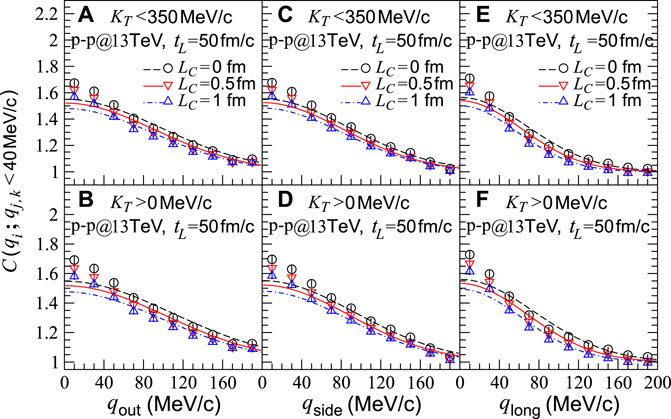

One can see that the HBT radii for the sources in the p-p collisions are small. The radii increase slightly with increasing LC, as is the sources in the nucleus–nucleus collisions. However, the effect of coherent emission length on λ parameter is small, and it reduces the λ value by approximately 8%. Because the average source size in the p-p collisions is almost independent of particle transverse momentum (Figure 1C), the effect of coherent emission length is almost the same in the two transverse momentum ranges. We show in Figure 7 the two-pion correlation functions with respect to relative momenta qout, qside, and qlong, for the sources in the p-p collisions and with tL = 50 fm/c. The lines are the fitted curves of Eq. 9.

FIGURE 7. Two-pion correlation functions with respect to relative momenta qi,j,k (i, j, and k = out, side, and long) for sources in p-p collisions at

4 Summary and Discussion

We construct a partially coherent source by introducing a coherent emission length for the identical pion emission points generated by the AMPT model. The effects of the coherent emission length on the two-pion interferometry results in central Au-Au collisions at

As a microscopic transport model, the AMPT model can provide the emission coordinates and momenta of particles in the source and has been extensively used in high energy nucleus–nucleus, proton–proton, and proton–nucleus collisions to explain experimental observables. The method used in this study was able to construct the partially coherent sources and affect the analysis results of two-pion HBT interferometry, especially the λ parameter. However, it does not affect the explanations that the AMPT model provides for other observables. The particle-emitting sources produced in high-energy particle collisions may perhaps be partially coherent. The coherent fraction of the systems is related to the source size, temperature, particle multiplicity in the collision, and so on. This study is a first step toward understanding the influence of particle coherent emission on two-pion HBT correlations. More detailed studies on the two- and multiparticle (pions and kaons) HBT correlations in partially coherent sources and a better understanding of the coherent emission mechanism by comparing model and experimental HBT results will be of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

W-NZ and S-YW contributed to conception and design of the study.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12175031).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zi-Wei Lin for useful discussions on the AMPT model.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2022.835592/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Gyulassy M, Kauffmann SK, Wilson LW. Pion Interferometry of Nuclear Collisions. I. Theory. Phys Rev C (1979) 20:2267–92. doi:10.1103/physrevc.20.2267

2. Wong CY. Introduction to High-Energy Heavy-Ion Collisions. Singapore: World Scientific (1994). Chap. 17.

4. Weiner R. Boson Interferometry in High-Energy Physics. Phys Rep (2000) 327:249–346. doi:10.1016/s0370-1573(99)00114-3

6. Lisa MA, Pratt S, Soltz R, Wiedemann U. Femtoscopy in Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions: Two Decades of Progress. Annu Rev Nucl Part Sci (2005) 55:357–402. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.55.090704.151533

18. Bary G, Zhang W-N, Ru P, Yang J. Analyses of Multi-Pion Bose-Einstein Correlations for Granular Sources with Coherent Pion-Emission Droplets *. Chin Phys. C (2021) 45:024106. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abcd8d

19. Lin ZW, Ko CM. Partonic Effects on the Elliptic Flow at Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions. Phys Rev C (2002) 65:034904. doi:10.1103/physrevc.65.034904

20. Lin ZW, Ko CM, Li BA, Zhang B, Pal S. Multiphase Transport Model for Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions. Phys Rev C (2005) 72:064901. doi:10.1103/physrevc.72.064901

21. Nasim M, Kumar L, Kumar P, Mohanty B. Energy Dependence of Elliptic Flow from Heavy-Ion Collision Models. Phys Rev C (2010) 82:054908. doi:10.1103/physrevc.82.054908

22. Xu J, Ko CM. Effects of Triangular Flow on Di-hadron Azimuthal Correlations in Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions. Phys Rev C (2011) 83:021903(R. doi:10.1103/physrevc.83.021903

23. Bzdak A, Ma G-L. Elliptic and Triangular Flow Inp-Pb and Peripheral Pb-Pb Collisions from Parton Scatterings. Phys Rev Lett (2014) 113:252301. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.113.252301

25. Li H, He L, Lin ZW, Molnar D, Wang F, Xie W. Origin of the Mass Splitting of Azimuthal Anisotropies in a Multiphase Transport Model. Phys Rev C (2017) 96:014901. doi:10.1103/physrevc.96.014901

26. Nagle JL, Belmont R, Hill K, Koop JO, Perepelitsa DV, Yin P, et al. Minimal conditions for collectivity in e+e− and p+p collisions. Phys Rev C (2018) 97:024909. doi:10.1103/physrevc.97.024909

27. Nie MW, Huo P, Jia J, Ma GL. Multiparticle Azimuthal Cumulants in p+Pb Collisions from a Multiphase Transport Model. Phys Rev C (2018) 98:034903. doi:10.1103/physrevc.98.034903

28. Haque MR, Nasim M, Mohanty B. Systematic Investigation of Azimuthal Anisotropy in Au+Au and U+U Collisions at $\sqrt{{s}_{{NN}}}=200\,\mathrm{GeV}$. J Phys G: Nucl Part Phys (2019) 46:085104. doi:10.1088/1361-6471/ab2ba4

29. Shao T, Chen J, Ko CM, Lin ZW. Enhanced Production of Strange Baryons in High-Energy Nuclear Collisions from a Multiphase Transport Model. Phys Rev C (2020) 102:014906. doi:10.1103/physrevc.102.014906

30. Magdy N, Lacey RA. Model Investigation of the Longitudinal Broadening of the Transverse Momentum Two-Particle Correlator. Phys Rev C (2021) 104:014907. doi:10.1103/physrevc.104.014907

31. Magdy N, Evdokimov O, Lacey RA. A Method to Test the Coupling Strength of the Linear and Nonlinear Contributions to Higher-Order Flow Harmonics via Event Shape Engineering. J Phys G: Nucl Part Phys (2021) 48:025101. doi:10.1088/1361-6471/abcb59

32. Zheng L, Zhang G-H, Liu Y-F, Lin Z-W, Shou Q-Y, Yin Z-B. Investigating High Energy Proton Proton Collisions with a Multi-phase Transport Model Approach Based on PYTHIA8 Initial Conditions. Eur Phys J C (2021) 81:755. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-021-09527-5

33. Wang X-N, Gyulassy M. Hijing: A Monte Carlo Model for Multiple Jet Production inpp,pA, andAAcollisions. Phys Rev D (1991) 44:3501–16. doi:10.1103/physrevd.44.3501

34. Zhang B. ZPC 1.0.1: a Parton cascade for Ultrarelativistic Heavy Ion Collisions. Comp Phys Commun (1998) 109:193–206. doi:10.1016/s0010-4655(98)00010-1

35. Li B-A, Ko CM. Formation of Superdense Hadronic Matter in High Energy Heavy-Ion Collisions. Phys Rev C (1995) 52:2037–63. doi:10.1103/physrevc.52.2037

36. Bertsch G, Gong M, Tohyama M, Bertsch GF. Pion interferometry as a probe of the plasma. Nuc Phys A (1989) 498:173c–179c. doi:10.1103/physrevc.37.1896

37. Pratt S, Csörgő T, Zimányi J. Detailed Predictions for Two-Pion Correlations in Ultrarelativistic Heavy-Ion Collisions. Phys Rev C (1990) 42:2646–52. doi:10.1103/physrevc.42.2646

Keywords: high-energy collisions, coherent emission length, two-pion correlation functions, HBT interferometry PACS numbers: 25.75.Gz, 25.75.-q, 21.65.jk

Citation: Wang S-Y and Zhang W-N (2022) Investigating Effect of Coherent Emission Length on Pion Interferometry in High-Energy Collisions Using a Multiphase Transport Model. Front. Phys. 10:835592. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.835592

Received: 14 December 2021; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 10 May 2022.

Edited by:

Khusniddin Olimov, Physical-Technical Institute of Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, UzbekistanReviewed by:

Ghulam Bary, Yibin University, ChinaNiseem Magdy, University of Illinois at Chicago, United States

Copyright © 2022 Wang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei-Ning Zhang, d256aGFuZ0BkbHV0LmVkdS5jbg==

Shi-Yao Wang

Shi-Yao Wang Wei-Ning Zhang

Wei-Ning Zhang