95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Phys. , 13 May 2021

Sec. Optics and Photonics

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.684958

This article is part of the Research Topic Femtosecond Laser Inscribed Passive and Active Guiding Structures in Transparent Materials View all 8 articles

Trivalent praseodymium (Pr3+) is the most established rare-earth ion for the direct generation of visible light. In our work, based on Pr-doped Lu3Al5O12 (LuAG) single crystal, cladding waveguides are fabricated by applying femtosecond laser inscription with different parameters. The main characteristics of the waveguides such as mode distributions, propagation losses are investigated. The investigations on confocal micro-photoluminescence enable us to illustrate femtosecond laser induced modifications in Pr:LuAG matrix. The waveguides are further pumped at a wavelength of 450 nm with an InGaN laser diode. Guided fluorescence emissions in visible range covering green, yellow-green, orange and red are obtained with a maximum slope efficiency of 4 × 10−4.

The development of visible light sources is of great interest due to their possible applications in a wide range of topical areas such as color display, imaging, biomedical diagnostics and chemical sensing [1–4]. With regard to this aim, rare-earth doped crystalline materials have shown powerful capability of direct emission of fluorescence and laser in the visible, allowing for light sources with significant advantages in terms of simple in alignment, high compactness and inherent robustness [5–8].

Garnet-based materials have been widely used as host matrixes owing to their outstanding physical and chemical properties. Of ten garnet host materials, Lu3Al5O12 (LuAG), an isomorphic material of YAG, is chosen for study. When compared with YAG, LuAG crystal exhibits comparable hardness (7.5 Mohs) and thermal conductivity (9.6 W/mK) together with higher melting point (2,010°C), making it suitable for ultrafast laser machining and high power pumping [9, 10]. Furthermore, the crystal is characterized by low thermal occupation factor for the lower laser level, which can be ascribed to the large manifold splitting [11]. More importantly, these features can be well preserved in rare-earth doped LuAG since the molar mass of Lu3+ is close to that of dopant ions [9, 10, 12, 13]. Among active rare-earth ions providing transitions in the visible, Pr3+ is the most established one because of its multiple transitions that allow emission in the red, orange, green and blue spectral domains in combination with high absorption cross sections (up to 10−19 cm2 at the dominant emission in the red) and long upper state lifetime (several ten microseconds) [5]. Further, the absorption lines of Pr3+ overlap well with the emission of InGaN laser diodes in the blue spectral range, which, benefiting from the development of novel pump sources based on semiconductor gain materials, gives rise to the extensive researches of visible light sources based on Pr3+ [14–20].

Waveguide structures, which can confine the light propagation in a dimension with order of microns, are considered to be the fundamental components of photonic integrated circuits. A large number of techniques have been employed with the aim of fabricating waveguide structures with high optical performances [21–23]. Femtosecond laser inscription (FLI) has emerged as an unprecedented three dimensional (3D) waveguide fabrication technology, which can be manifested in plentiful transparent materials [21, 24–27]. During the FLI process, high optical energy at the laser focus would be deposited inside the materials due to the nonlinear multi-photon absorption, resulting in a highly localized structural modification to the materials, one example of which is refractive index (RI) change that is responsible for the formation of waveguide structures [28, 29]. Depressed cladding waveguides produced by FLI have attracted increasing attention since they have flexible tubular structures that ensure high coupling efficiency between input laser mode and guiding mode [30, 31]. Such a morphology shows its unique ability of propagating both transverse polarizations [8, 32], which makes it an ideal platform for unpolarized pumping as light sources. More attractively, many of the optical effects in the waveguides can be enhanced by the high intra-cavity light energy, which, for instance, enables high emission at low excitation [21, 33].

In this work, we focus on fabrication and characterizations of the depressed cladding waveguides in Pr:LuAG crystals by using FLI. Wave-guiding performances and confocal micro-photoluminescence (μ-PL) properties of the cladding structures are investigated. The waveguides are further pumped by a 450 nm laser diode, realizing guided fluorescence with multiple wavelengths in visible spectral range.

The Pr:LuAG crystal (doped by 3 at% Pr3+ ions) is cut into a 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm cuboid, with six facets polished to optical quality. In order to fabricate cladding structures, the prepared Pr:LuAG crystal is mounted to a set of high precision x-y-z air bearing translation stages made by Aerotech® (ABL1000). The femtosecond (fs) laser is provided by an IMRA® FCPA µJewel D400, delivering 360 fs pulses with 500 kHz repetition rate. The output is centered at 1,047 nm and has a bandwidth of 10 nm (FWHM). The laser system produces linearly polarized light which is attenuated by a half-wave plate and polarizing beam splitter combination. The laser beam is focused by a 0.4 NA aspheric lens into the substrate. By using a transverse scanning geometry (i.e., the substrate is translated perpendicular to the laser beam axis) with a speed of 3 mm/s, a series of tracks are inscribed, forming tubular claddings with a central location of 300 μm beneath one of the 10 mm × 10 mm surfaces. The average laser power for inscription varies from 220 to 60 mW with a step of 20 mW, corresponding to pulse energy decreasing from 0.44 to 0.12 μJ. The diameters of fabricated structures are designed to be 35–15 μm with a varying step of 5 μm.

The guiding properties of these waveguides are investigated by applying a typical end-face coupling arrangement with a linearly-polarized diode laser at 633 nm, the polarization of which is controlled with a half-wave plate. A CCD camera is used to record the modal profiles of the output light. By directly detecting the incident and output beam powers, the propagation losses α of the cladding waveguides can be calculated as follows:

in which Pin and Pout correspond to the input and output laser powers, respectively. R, determined to be 0.0878 for Pr:LuAG crystal, is the Fresnel reflection coefficient at waveguide-air interface. L presents the length of the waveguide and η is the coupling efficiency that relates to the mode mismatch between the pump beam and the waveguide, which can be approximated by using the formula:

where ω1 is the mode width of the pump beam and ω2 is the mode size of the waveguide which, in our work, is assumed to be single-mode. For pump beam that is focused with convex lenses, the mode width ω1 can be calculated with the following equation:

where

The room-temperature confocal μ-PL properties of the fabricated structures in Pr:LuAG are investigated using a confocal microscope with a fiber-coupled system (WITec alpha 300R). A continuous wave (CW) radiation from a high performance single frequency diode pumped laser at 488 nm, being used as an excitation laser, is focused via a 100× microscope objective lens (NA = 0.9). The scattered PL light is dispersed by a 300 mm focal length spectrometer (UHTS 300) with a 150 grooves/mm grating. The signals are eventually detected using a CCD thermoelectrically cooled to −60°C.

With an end-face coupling system, the characterizations of guided fluorescence from the cladding waveguides are investigated, in terms of emission spectra, mode profiles and intensities. Pumping is achieved with the aid of a fiber coupled CW diode laser at 450 nm, meeting the absorption line of Pr:LuAG crystal in the blue spectral range. After being collimated, the pump beam is focused and coupled into the waveguide by a 25× microscope objective (NA = 0.40). The visible fluorescence emission from the waveguide is collected by another 10× microscope objective with 0.25 NA and then separated from the residual pump with a 460 nm long-pass filter. For comparison, the fluorescence generated from the bulk are also detected.

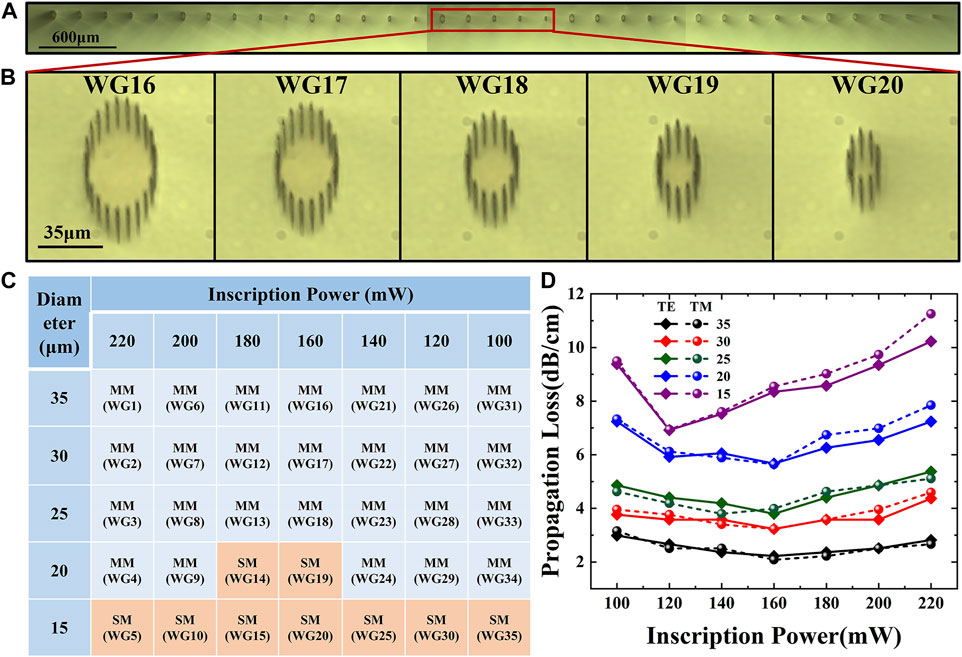

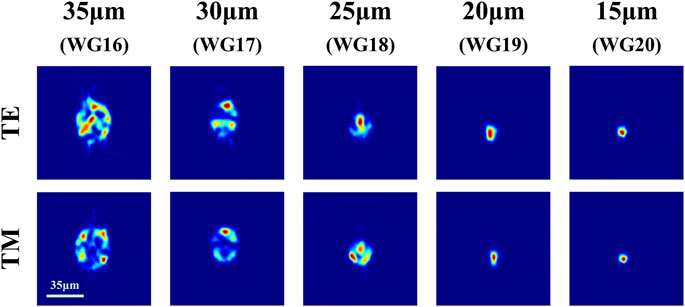

During the FLI process it is found that, with the laser power decreasing lower than 80 mW, no obvious modification is induced, leaving 35 cladding waveguides produced. These waveguides are numbered as WG1–WG35 from left to right in Figure 1A which is the cross sectional microscope images of the fabricated waveguides. For easy visualization, zoomed-in images of waveguides fabricated with an average laser power of 160 mW (WG16–WG20) are shown in Figure 1B. As can be clearly observed, circularly-shaped waveguide boundaries are produced deeply embedded in the substrate without any damage in the core regions. Therefore, the excellent properties of Pr:LuAG crystal are expected to be well preserved in the guiding areas. Mode distributions of 35 waveguides at 633 nm are experimentally captured. The mode numbers are proved to be reducing along with the reduction of the waveguide diameters, until 15 μm, at which point the structures become single-mode. Furthermore, single-mode guidance is also obtained from WG14 and WG19, the diameters of which are 20 μm. Increasing the mode size while maintaining single mode performance demonstrates the appropriateness of inscription laser powers of 180 and 160 mW. In Figure 1C, the mode patterns of all 35 waveguides are summarized and single-mode waveguides are highlighted in orange. Nonetheless, the waveguides inscribed with smaller sizes are found to be weakly guiding, leading to relatively high propagation losses as evidenced in Figure 1D which exhibits the loss-dependence on the fabricating parameters of 35 waveguides measured with both TE- and TM-polarized laser beams. As for waveguides with 35 μm diameter, the minimum value of propagation loss is estimated to be around 2.08 dB/cm, implying that the optimized laser power for waveguide inscription in Pr:LuAG is about 160 mW and lower losses could be expected with even larger structures. Additionally, it is reasonable to deduce that the actual mode mismatch η of multi-mode waveguide is higher than its calculated value owing to the assumption of single-mode profile; consequently, the waveguides produced in our work possess even lower propagation losses than the values measured experimentally. It is worth pointing out that these waveguides exhibit ability of propagating both transverse polarizations without significant difference on propagation losses, which further highlights the advantage of polarization independence of cladding structures. As an illustration of strong optical confinement, Figure 2 shows the mode distributions of WG16–WG20 under both TE and TM polarizations. For WG19 and WG20, Gaussian-type profiles are achieved, which is typical of all of the nine single-mode waveguides inscribed and measured.

FIGURE 1. (A) The end-face microscope images of cladding waveguides in Pr:LuAG. (B) Enlarged images of WG16-WG20. (C) Mode profiles observed from all 35 waveguides; MM and SM represent multi-mode and single-mode, respectively. Single-mode wavegudies are highlighted in orange. (D) Propagation losses of the cladding waveguides at 633 nm under TE and TM polarization.

FIGURE 2. Model profiles of the cladding waveguides WG16-WG20 at 633 nm under TE and TM polarization.

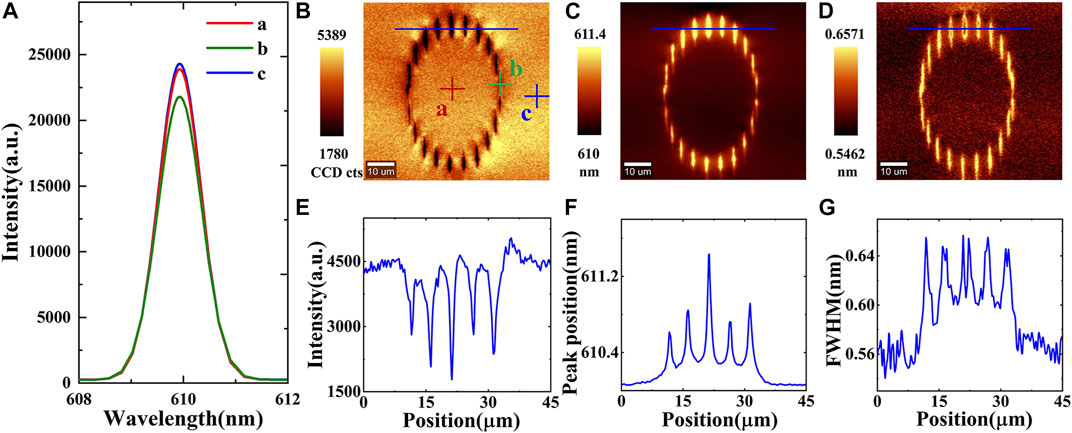

With WG16 as a representative, the confocal μ-PL properties of the Pr3+ ions are investigated as shown in Figure 3. Figure 3A depicts the Gaussian fitted μ-PL spectra of the 3P0→3F2 emission lines around 610 nm collected from the guiding core (point a in Figure 3B), the filament constituting the cladding (point b) and the Pr:LuAG bulk (point c). In order to obtain the detailed modification of luminescence properties and get complete knowledge on micro-structural changes over the whole waveguide cross-section, 2D mappings of the intensity, spectral shift and bandwidth of the emission lines are obtained from a wide area covering the modified and unmodified Pr:LuAG volumes, as shown in Figures 3B–D. Meanwhile, 1D distributions, as plotted in Figures 3E–G, are measured along the lines crossing the filaments indicated in Figures 3B–D. It can be concluded that, as compare with the bulk, the laser-induced filaments are characterized by 1) quenching in the luminescence intensity indicating the presence of the irreversible damages, lattice defects and imperfections, 2) red-shift of the emission line corresponding to extended lattices that leads to expansive stress in these areas, and 3) broadening of the spectra that further suggests the presence of lattice disorders. All of these features indicate a large degree of lattice modifications induced in filaments by fs-laser, which are responsible for the RI reduction in the cladding areas, and hence have considerable effects on the guiding properties of the waveguides. In addition, it is clear that the spectroscopic properties of the Pr3+ ions are well preserved in the guiding core, showing the potential of active applications of these structures for guided fluorescence or laser emissions.

FIGURE 3. (A) The μ-PL spectroscopy of WG16 obtained from the inner core (a), processing track (b) and bulk material (c). The 2D mappings and 1D profiles of intensity (B,E), peak position (C,F) and FWHM (D,G) of μ-PL spectra obtained from the WG16. 1D profiles are measured along the blue lines in (B–D).

Under 450 nm diode laser excitation, the spectra of guided fluorescence excited with fixed pumping power are collected from the 35 cladding waveguides and the bulk. The results, focusing on the 609 nm emission lines corresponding to 3P0→3H6 transition of Pr3+ ions, are depicted in Figure 4A. For easy comparison, Figure 4B plots the relative intensities of emission lines. It is obvious that, with fixed inscription power, the performance of guided fluorescence improves while the guiding core is enlarged, which is related to the reduction of propagation losses. As expected, the best performance is observed in WG16. Meanwhile, in comparison with the bulk, the fluorescence intensities are strengthened in the waveguides, revealing the strong optical confinement of the fluorescence in the guiding volumes, as further evidenced by the photograph of visible emission in WG16 (see inset of Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4. (A) Fluorescence spectra around 609 nm obtained from 35 waveguides and bulk material under 450 nm diode laser excitation. The inset of (A) shows the visible fluorescence generated in WG16. (B) The dependence of relative intensities of 609 nm emission lines on the fabrication parameters.

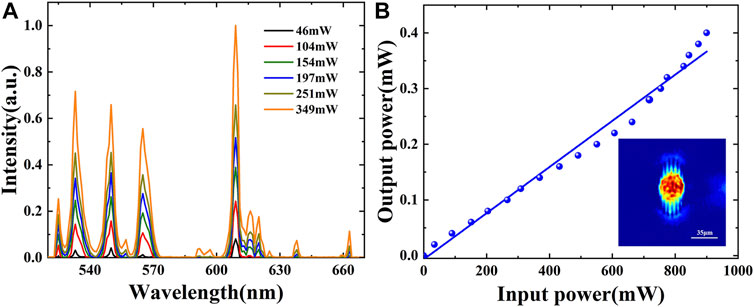

The overall fluorescence spectra generated from WG16 are further measured with increasing excitation power, as described in Figure 5A. The emission lines have been proved to be arised from the radiation transitions 4f-4f of Pr3+ ions [33]. Such an emission possesses a broad bandwidth covering green, yellow-green, orange, and red spectral ranges, with five dominated peaks centered at 525, 533, 550, 565, and 609 nm, corresponding to the main transition lines of 3P0→3H5, 1I6→3H5, 3P0→3H5, 3P0→3H5, and 3P0→3H6 of Pr3+ ions [5, 16–20]. Furthermore, as the excitation power is increased, the intensities of all emission lines are found to be increasing. Figure 5B plots the output fluorescence power obtained from WG16 as a function of incident power. The highest output power of 0.4 mW at 900 mW pumping is achieved. The linear fitting of the experimental results gives a slope efficiency of 4 × 10−4, which is comparable to that recorded from the cladding waveguides in Ti:Sapphire as previously reported in [8]. The inset of Figure 5B shows the intensity profile of the output signal originated from WG16, which further confirmed the strong optical confinement of the guided fluorescence.

FIGURE 5. (A) Overall spectra of the guided fluorescence from WG16 measured with increasing excitation power. (B) Dependence between the output fluorescence power and the input power from WG16. The blue balls represent the experimental results and the solid line is linear fitting of experiment data. The inset of (B) is the mode distribution of waveguide fluorescence obtained from WG16.

Table 1 lists the performances of waveguides in Pr3+ doped crystalline materials fabricated by using liquid phase epitaxy (LPE) and FLI. Compared with planar and double-line waveguides [35–38], the structures produced in our work are superior owing to their flexibility in shape and size that enables high coupling efficiency when connecting with the commercial fibers to construct fiber-waveguide-fiber integrated photonic circuits. More importantly, unlike the previously demonstrated waveguides that only support guidance or emission under certain polarization [15, 34–38], the waveguides fabricated here show unique ability of propagating both transverse polarizations at pumping and emission wavelength, meeting the requirement of unpolarized pumping as light sources or applications related to polarization independence. Furthermore, the guided fluorescence obtained in our work possess broad emission band which, in combination with the unique optical properties of LuAG crystal, suggests promising potential of these cladding waveguides as integrated fluorescence sources for visible applications.

In conclusion, we demonstrate for the first time to the best of our knowledge femtosecond-laser- inscribed waveguides in Pr:LuAG single crystal. The investigations on the guiding performance highlight the good properties of the fabricated waveguides especially in terms of single-mode guidance and polarization independence. The optimized laser power for waveguide fabrication in Pr:LuAG is found to be around 160 mW. Confocal micro-luminescence investigations evidence lattice damages, defects, imperfections and disorders in fs-laser induced filaments, with these effects being at the basis of the refractive index modification. Meanwhile, the spectral properties of Pr3+ ions are well preserved in the guiding core. Guided fluorescence in a tubular cladding geometry operates at a maximum output power of 0.4 mW under 900 mW of incident InGaN-laser-diode emission at 450 nm. The fluorescence shows broad bandwidth with five dominated peaks centered at 525, 533, 550, 565, and 609 nm. This study paves the way for the realization of miniature integrated platforms in Pr:LuAG crystal for possible applications as visible light sources in photonic integrated circuits.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YR, YC, and LS proposed research ideas and plans, LS, CW, ZC, RL, MM, and AK were responsible for experiments, LS was responsible for collecting and analyzing data, YR and LS did the writing of the paper. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This work is supported by National key Research and Development Project of China (2019YFA0705000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (11874243), Innovation Group of Jinan (2018GXRC010) and Local Science and Technology Development Project of the Central Government (No. YDZX20203700001766).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Chellappan KV, Erden E, Urey H. Laser-Based Displays: A Review. Appl Opt (2010) 49:F79–98. doi:10.1364/AO.49.000F79

2. Kowalevicz A, Ko T, Hartl I, Fujimoto J, Pollnau M, Salathe R. Ultrahigh Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography Using a Superluminescent Light Source. Opt Express (2002) 10:349–53. doi:10.1364/OE.10.000349

3. Kotani A, Witek MA, Osiri JK, Wang H, Sinville R, Pincas H, et al. EndoV/DNA Ligase Mutation Scanning Assay Using Microchip Capillary Electrophoresis and Dual-Color Laser-Induced Fluorescence Detection. Anal Methods (2012) 4:58–64. doi:10.1039/c1ay05366c

4. Fan F, Turkdogan S, Liu Z, Shelhammer D, Ning CZ. A Monolithic White Laser. Nat Nanotech (2015) 10:796–803. doi:10.1038/nnano.2015.149

5. Kränkel C, Marzahl D-T, Moglia F, Huber G, Metz PW. Out of the Blue: Semiconductor Laser Pumped Visible Rare-Earth Doped Lasers. Laser Photon Rev (2016) 10:548–68. doi:10.1002/lpor.201500290

6. Lv Y, Jin Y, Sun T, Su J, Wang C, Ju G, et al. Visible to NIR Down-Shifting and NIR to Visible Upconversion Luminescence in Ca14Zn6Ga10O35:Mn4+, Ln3+ (Ln=Nd, Yb, Er). Dyes Pigm (2019) 161:137–46. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.09.052

7. Zhang L, Guo T, Ren Y, Cai Y, Mackenzie MD, Kar AK, et al. Cooperative Up-Converted Luminescence in Yb,Na:CaF2 Cladding Waveguides by Femtosecond Laser Inscription. Opt Commun (2019) 441:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.optcom.2019.01.032

8. Ren Y, Jiao Y, Vázquez de Aldana JR, Chen F. Ti:Sapphire Micro-structures by Femtosecond Laser Inscription: Guiding and Luminescence Properties. Opt Mater (2016) 58:61–6. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2016.05.023

9. Cui Q, Zhou Z, Guan X, Xu B, Lin Z, Xu H, et al. Diode-pumped Continuous-Wave and Passively Q-Switched Nd:LuAG Crystal Lasers at 1.1 μm. Opt Laser Technol (2017) 96:190–5. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2017.05.032

10. Wang Y, Li Z, Yin H, Zhu S, Zhang P, Zheng Y, et al. Enhanced ∼3 μm Mid-Infrared Emissions of Ho3+ via Yb3+ Sensitization and Pr3+ Deactivation in Lu3Al5O12 Crystal. Opt Mater Express (2018) 8:1882–9. doi:10.1364/OME.8.001882

11. Hart DW, Jani M, Barnes NP. Room-Temperature Lasing of End-Pumped Ho:Lu3Al5O12. Opt Lett (1996) 21:728–30. doi:10.1364/OL.21.000728

12. Aggarwal RL, Ripin DJ, Ochoa JR, Fan TY. Measurement of Thermo-Optic Properties of Y3Al5O12, Lu3Al5O12, YAIO3, LiYF4, LiLuF4, BaY2F8, KGd(WO4)2, and KY(WO4)2 Laser Crystals in the 80-300K Temperature Range. J Appl Phys (2005) 98:103514. doi:10.1063/1.2128696

13. Gaumé R, Viana B, Vivien D, Roger J-P, Fournier D. A Simple Model for the Prediction of Thermal Conductivity in Pure and Doped Insulating Crystals. Appl Phys Lett (2003) 83:1355–7. doi:10.1063/1.1601676

14. Khurmi C, Thoday S, Monro TM, Chen G, Lancaster DG. Visible Laser Emission From a Praseodymium-Doped Fluorozirconate Guided-Wave Chip. Opt Lett (2017) 42:3339–42. doi:10.1364/ol.42.003339

15. Liu H, Luo S, Xu B, Xu H, Cai Z, Hong M, et al. Femtosecond-Laser Micromachined Pr:YLF Depressed Cladding Waveguide: Raman, Fluorescence, and Laser Performance. Opt Mater Express (2017) 7:3990–7. doi:10.1364/ome.7.003990

16. Metz PW, Reichert F, Moglia F, Müller S, Marzahl D-T, Kränkel C, et al. High-Power Red, Orange, and Green Pr3+:LiYF4 Lasers. Opt Lett (2014) 39:3193–6. doi:10.1364/OL.39.003193

17. Tanaka H, Kannari F. Power scaling of continuous-wave visible Pr3+:YLF laser end-pumped by high power blue laser diodes. In: OSA Laser Congress 2017; 2017 Oct 1–5; Nagoya, Aichi, Japan (2017). doi:10.1364/ASSL.2017.ATu1A.3

18. Sattayaporn S, Loiseau P, Aka G, Marzahl D-T, Kränkel C. Crystal Growth, Spectroscopy and Laser Performances of Pr3+:Sr0.7La0.3Mg0.3Al11.7O19 (Pr:ASL). Opt Express (2018) 26:1278–89. doi:10.1364/OE.26.001278

19. Fibrich M, Šulc J, Jelínková H. Pr:YAlO3 Laser Generation in the Green Spectral Range. Opt Lett (2013) 38:5024–7. doi:10.1364/ol.38.005024

20. Reichert F, Calmano T, Müller S, Marzahl D-T, Metz PW, Huber G. Efficient Visible Laser Operation of Pr,Mg:SrAl12O19 Channel Waveguides. Opt Lett (2013) 38:2698–701. doi:10.1364/OL.38.002698

21. Chen F, Vázquez de Aldana JR. Optical Waveguides in Crystalline Dielectric Materials Produced by Femtosecond-Laser Micromachining. Laser Photon Rev (2014) 8:251–75. doi:10.1002/lpor.201300025

22. Tan Y, Chen F, Stepic M, Shandarov V, Kip D. Reconfigurable Optical Channel Waveguides in Lithium Niobate Crystals Produced by Combination of Low-Dose O3+ Ion Implantation and Selective White Light Illumination. Opt Express (2008) 16:10465–70. doi:10.1364/OE.16.010465

23. Chen F. Optical Waveguides in Laser Crystals Produced by Energetic Ion Beam Irradiation. Sci Sin-Phys Mech Astron (2013) 43:810–20. doi:10.1360/132012-1025

24. Choi J, Schwarz C. Advances in Femtosecond Laser Processing of Optical Material for Device Applications. Int J Appl Glass Sci (2020) 11:480–90. doi:10.1111/ijag.14979

25. Jia Y, Wang S, Wang S, Chen F. Femtosecond Laser Direct Writing of Flexibly Configured Waveguide Geometries in Optical Crystals: Fabrication and Application. Opto-Electronic Adv (2020) 3:190042. doi:10.29026/oea.2020.190042

26. Choudhury D, Macdonald JR, Kar AK. Ultrafast Laser Inscription: Perspectives on Future Integrated Applications. Laser Photon Rev (2014) 8:827–46. doi:10.1002/lpor.201300195

27. Bharadwaj V, Jedrkiewicz O, Hadden JP, Sotillo B, Vázquez MR, Dentella P, et al. Femtosecond Laser Written Photonic and Microfluidic Circuits in Diamond. J Phys Photon (2019) 1:022001. doi:10.1088/2515-7647/ab0c4e

28. Tan D, Sharafudeen KN, Yue Y, Qiu J. Femtosecond Laser Induced Phenomena in Transparent Solid Materials: Fundamentals and Applications. Prog Mater Sci (2016) 76:154–228. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.09.002

29. Ródenas A, Torchia GA, Lifante G, Cantelar E, Lamela J, Jaque F, et al. Refractive Index Change Mechanisms in Femtosecond Laser Written Ceramic Nd:YAG Waveguides: Micro-Spectroscopy Experiments and Beam Propagation Calculations. Appl Phys B (2009) 95:85–96. doi:10.1007/s00340-008-3353-3

30. Jia Y, He R, Vázquez de Aldana JR, Liu H, Chen F. Femtosecond Laser Direct Writing of Few-Mode Depressed-Cladding Waveguide Lasers. Opt Express (2019) 27:30941–51. doi:10.1364/OE.27.030941

31. Ren Y, Vázquez de Aldana JR, Chen F, Zhang H. Channel Waveguide Lasers in Nd:LGS Crystals. Opt Express (2013) 21:6503–8. doi:10.1364/OE.21.006503

32. Ren Y, Zhang L, Xing H, Romero C, Vázquez de Aldana JR, Chen F. Cladding Waveguide Splitters Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Inscription in Ti:Sapphire Crystal. Opt Laser Technol (2018) 103:82–8. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.01.021

33. Yoshikawa A, Kamada K, Saito F, Ogino H, Itoh M, Katagiri T, et al. Energy Transfer to Pr3+ Ions in Pr:Lu3Al5O12 (LuAG) Single Crystals. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci (2008) 55:1372–5. doi:10.1109/TNS.2008.924051

34. Müller S, Calmano T, Metz P, Hansen NO, Kränkel C, Huber G. Femtosecond-Laser-Written Diode-Pumped Pr:LiYF4 Waveguide Laser. Opt Lett (2012) 37:5223–5. doi:10.1364/OL.37.005223

35. Starecki F, Bolaños W, Braud A, Doualan JL, Brasse G, Benayad A, et al. Red and Orange Pr3+:LiYF4 Planar Waveguide Laser. Opt Lett (2013) 38:455–7. doi:10.1364/OL.38.000455

36. Bolaños W, Brasse G, Starecki F, Braud A, Doualan JL, Moncorgé R, et al. Green, Orange, and Red Pr3+:YLiF4 Epitaxial Waveguide Lasers. Opt Lett (2014) 39:4450–3. doi:10.1364/OL.39.004450

37. Calmano T, Siebenmorgen J, Reichert F, Fechner M, Paschke AG, Hansen NO, et al. Crystalline Pr :SrAl12O19 Waveguide Laser in the Visible Spectral Region. Opt Lett (2011) 36:4620–2. doi:10.1364/OL.36.004620

Keywords: optical waveguide, femtosecond laser inscription, Pr:LuAG crystal, confocal micro-spectroscopy, fluorescence

Citation: Sun L, Wang C, Cui Z, Li R, Cai Y, Ren Y, Mackenzie MD and Kar AK (2021) Diode-Pumped Fluorescence in Visible Range From Femtosecond Laser Inscribed Pr:LuAG Waveguides. Front. Phys. 9:684958. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2021.684958

Received: 24 March 2021; Accepted: 28 April 2021;

Published: 13 May 2021.

Edited by:

Hongliang Liu, Nankai University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yicun Yao, Liaocheng University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Sun, Wang, Cui, Li, Cai, Ren, Mackenzie and Kar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yangjian Cai, eWFuZ2ppYW5jYWlAc2RudS5lZHUuY24=; Yingying Ren, cnl5d2x5QHNkbnUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.