- 1Institute of Physics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

- 2Nano Science and Technology Program, Taiwan International Graduate Program, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

- 3Department of Engineering and System Science, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

- 4BitSmart LLC, San Mateo, CA, United States

- 5Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

We carried out a detailed study to investigate the existence of an insulating parent phase for FeSe superconductors. The insulating Fe4Se5 with √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order shows a 3D-Mott variable-range-hopping behavior with a Verwey-like electronic correlation at around 45 K. The application of the RTA process at 450°C results in the destruction of Fe-vacancy order and induces more electron carriers by increasing the Fe3+ valence state. Superconductivity emerges with Tc ∼ 8 K without changing the chemical stoichiometry of the sample after the RTA process, resulting in the addition of extra carriers in favor of superconductivity.

Introduction

The FeAs-based [1] and FeSe-based [2] superconductors are among the most investigated materials in condensed matter physics since their discovery in 2008. The observation of a wide range of superconducting transition temperatures, with the highest confirmed Cooper pair formation temperature up to 75 K in monolayer FeSe films [3], provides a unique opportunity to gain more insight into the origin of high-temperature superconductivity. The multiple-orbital nature of the Fe-based materials, combined with spin and charge degrees of freedom, results in the observation of many intriguing phenomena such as structural distortion, magnetic or orbital ordering [4], and electronic nematicity [5,6]. There are suggestions that the orbital fluctuation may provide a new channel for realizing superconductivity [7, 8].

The parent compounds of FeAs-based materials exhibit structural transitions from a high-temperature tetragonal phase to a low-temperature orthorhombic phase, which is accompanied by an antiferromagnetic (AF) order [910]. Upon doping, both the orthorhombic structure and the AF phase are suppressed and superconductivity is induced. On the other hand, FeSe undergoes a tetragonal-to-orthorhombic transition at ∼ 90 K [2,11,12]. However, no magnetic order is formed at ambient pressure [12,13] and superconductivity below ∼8 K [2] is crucially related to this orthorhombic distortion. The nematic order coexists with superconductivity but not with long-range magnetic order which has led to arguments that the origin of the nematicity in FeSe is not magnetically but likely orbital-driven [14,15].

However, recent studies show that the nematic states in the FeSe systems are far more complex [16–20]. There exist strong high-energy spin fluctuations [20] which suggest that the nematicity and magnetism may be still intimately linked. It was also found that there are many interesting features in the band structures of the nematic state. More surprises came as one applied pressure to FeSe. The application of pressure leads to the suppression of structural transition, the appearance of a magnetically ordered phase at ∼1 GPa [13,21], and Tc increases to a maximum ∼37 K [22–27] at ∼6 GPa. An even more dramatic enhancement of Tc was achieved on monolayer FeSe grown on SrTiO3 substrate [28–31].

The above observations lead to questions that exist since the discovery of FeSe superconductors: what is the exact chemical stoichiometry of the compound and what is the exact phase diagram for the FeSe system? Earlier studies showed that the superconducting property of FeSe is very sensitive to its stoichiometry [2[12[32]. The fact that higher superconducting transition temperature exists in monolayer FeSe on SrTiO3 substrate suggests that the commonly accepted phase diagram, derived from assuming that FeTe is the nonsuperconducting parent compound of FeSe [33], is questionable. Studies have observed the trace of the superconducting feature with Tc close to 40 K in samples of nanodimensional form [34].

It has been a debate whether there exists an antiferromagnetic Mott insulating parent phase, similar to the cuprate superconductors, for FeSe superconductors [35–37]. Chen et al. first reported the existence of tetragonal β-Fe1-xSe with Fe-vacancy orders, characterized by analytical transmission electron microscopy [38]. The authors further argued the Fe4Se5 phase with √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order to be the parent phase of FeSe superconductors [38]. The Fe-vacancy order observed in the Fe4Se5 phase is identical to the Fe-vacancy order observed in the A2Fe4Se5 (A = K, Tl, Rb), which has been shown to be an antiferromagnetic [35, 39–42] and is the parent phase of the superconductor A2-xFe4+xSe5 [43,44]. The detailed studies of the Fe vacancy in K2Fe4+xSe5 reveal that its order/disorder is directly associated with superconductivity. A recent study shows that the Fe-vacancy-ordered Fe4Se5 nanowire is the nonoxide material with the Verwey-like electronic correlation [45]. It suggests that a charge-ordered state emerges below T = 17 K. The question remains unanswered is whether this Fe-vacancy-ordered phase is the parent compound of superconducting FeSe?

In this paper, we present the results of structure, electrical transport, and magnetic measurements on the polycrystalline sample of Fe4Se5 treated by rapid-thermal-annealing (RTA) process at a proper temperature and time. After RTA treatment, the sample shows superconductivity with Tc ∼ 8 K without changing its chemical stoichiometry. Our findings confirm that the Fe4Se5 with Fe-vacancy order is the parent compound of FeSe superconductors.

Experimental Techniques

Sample Preparation

Fe4Se5 nanosheets were prepared by a chemical coprecipitation method. First, 200 ml of ethylene glycol was mixed with NaOH and SeO2 powder and slowly heated up to 160°C for mixing well. The volume of 2.4 ml hydrazine hydrate was then added as the reducing agent. Then, at 160°C, the Fe precursor solution was added and reacted for 12 h in order to form Fe4Se5 nanosheets. The Fe precursor solution is made by dissolving the amount FeCl2 in ethylene glycol. The reaction was done under N2 gas purging to avoid the formation of oxide impurity. To clean the Fe4Se5 nanosheets, the reacted product was dispersed in acetone with absolute ethanol, and high-speed centrifugation is applied to precipitate the nanosheets and remove the capping ligand dissolved in the above organic solvent. The nanosheets were finally dried in a vacuum for 24 h and collected. The process for the rapid thermal annealing (RTA) is as follows: the as-grown Fe4Se5 nanosheets were heated at 450°C for 10 min in a tube furnace with 1 atm Ar gas inside to maintain a nonoxidation environment as a rapid thermal treatment process. After the rapid thermal treatment, an air-quenching process was taken by flowing room-temperature Ar gas through the tube. All the samples were stored in the oxygen-free glove box.

Analysis

The crystal structure observation of the Fe4Se5 samples was carried out by the high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, JEOL JEM-2100F) and 4-circle x-ray diffractometer with the incident beam (12.4 keV) of wavelength 0.82656 Å at beam-line BL13A and wavelength 0.61992 Å at beam-line TPS09A in NSRRC. The temperature-dependent structural information of Fe4Se5 samples was analyzed by the high-resolution neutron powder diffraction (high-resolution powder diffractometer Echidna with the wavelength of 2.4395 Å at ANSTO). The Fe4Se5 nanosheet powder was pressed into the pallet under 200 kg/cm2 at 100°C for 1 h for the following measurements: To identify the stoichiometry, the energy-disperse X-ray spectrometer (EDS) setup with the SEM (JEOL JSM-7001F Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope) was applied. To affirm the valence states of the Fe ions, the X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS, VG Scientific ESCALAB 250) measurements for the samples were performed. For polycrystalline bulk samples, the resistance was measured by using the standard four-probe method with silver paste for electrical contact and the Hall measurement by a Hall-bar configuration was done by the Quantum Design Physical Properties Measurement System (PPMS, Model 6000). The magnetic property was measured by the Quantum Design Superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID, VSM).

Experimental Results and Discussions

Structural Analysis of Fe4Se5

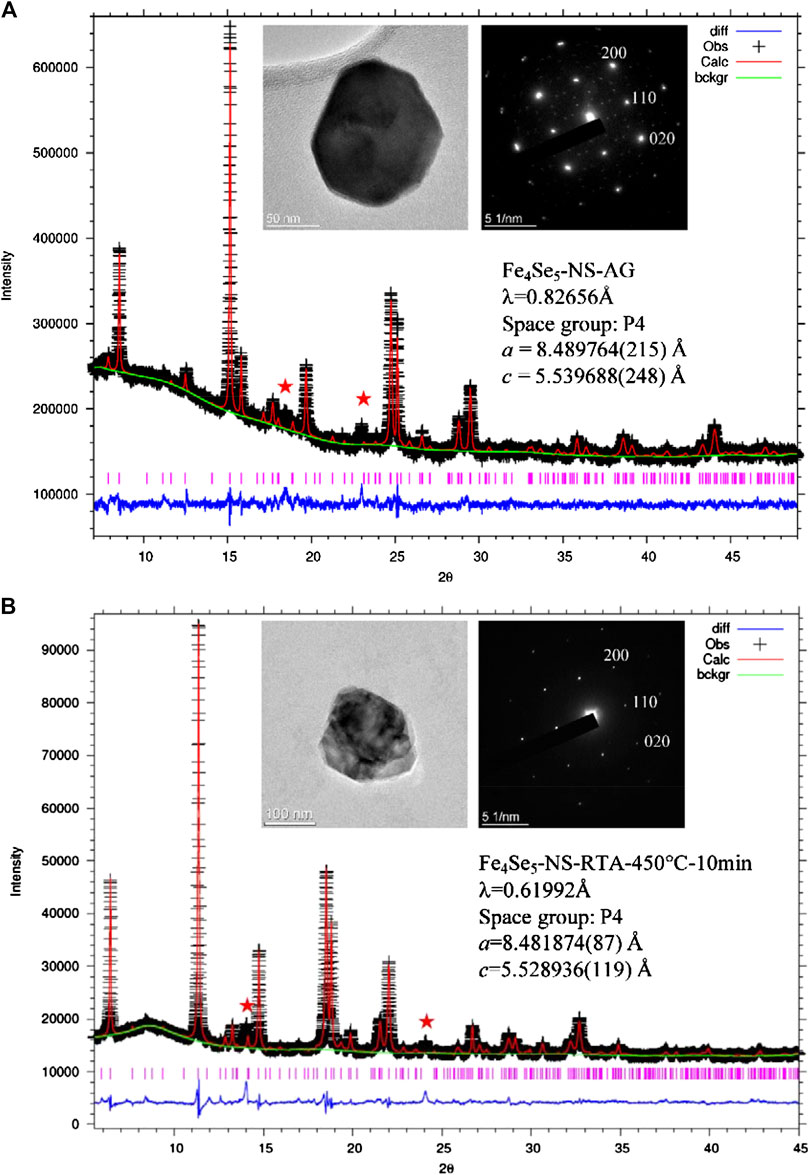

Figure 1A shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample at room temperature. The diffraction pattern, which exhibits superstructure peaks, is refined with a tetragonal P4 symmetry with √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order instead of the tetragonal P4/mmm symmetry as observed in FeSe [2]. The insets are the TEM image of as-grown Fe4Se5 nanocrystal and its TEM-SAED (selective area electron diffraction) patterns along the c-axis. The observation of extra diffraction points among the main diffraction points in the SAED pattern confirms the √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order in the as-grown Fe4Se5 nanocrystal [35]. After RTA treatment at 450°C, the superstructure peaks observed in XRD and TEM-SAED due to the √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order disappear, as shown in Figure 1B and its inset. The refinement results, using the same P4 symmetry, reveal that the occupations of Fe at vacancy 4d sites and the originally occupied 16i sites are almost the same, indicating that the Fe vacancies become disordered after RTA treatment. It is noted that the XRD patterns of the RTA treatment sample are nearly ten times smaller in the intensity response. This is due to the different synchrotron beamlines we used for our measurements. However, the difference does not affect the refined results.

FIGURE 1. X-ray diffraction patterns and their Rietveld refinement results of (A) the as-grown Fe4Se5 nanocrystals and (B) the sample after the RTA process at 450°C. The insets in (A) and (B) show the transmission electron microscope (TEM) images and selective area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the samples, respectively.

It is noted that the FeSe4 tetrahedron in as-grown Fe4Se5 is highly distorted due to the existence of the Fe-vacancy order. As the Fe vacancies disordered by the RTA treatment, the FeSe4 tetrahedron becomes more symmetric. The refined structure parameters are tabulated in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The EDS analysis confirms that the stoichiometries of samples keeps Fe4Se5 with Fe/Se ratio of 44.5 : 55.5 and 45.3 : 54.7 before and after the RTA treatment, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2 in the supplementary information.

Temperature Dependence of the Resistance and the Magnetic Susceptibility Measurement of Fe4Se5

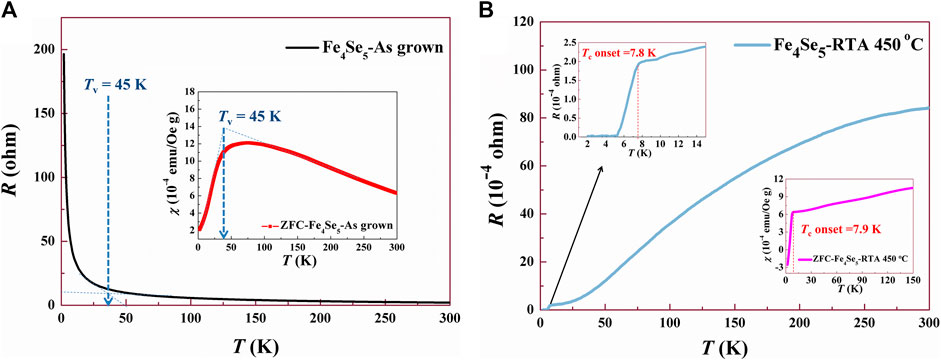

Figure 2A shows the temperature dependence of the resistance for the as-grown polycrystalline pellet sample made of Fe4Se5 nanosheets. The inset is the magnetic susceptibility of the as-grown sample from 300 to 2 K. The R-T results of Fe4Se5 exhibit a metal-insulator transition with the sharp rise in resistance at ∼45 K. The data can be well-fitted to the three-dimensional Mott variable-range-hopping model (3D-MVH): ρ(Τ) = ρ0 exp(T0/Τ)ν, where T0 is the variable-range-hopping characteristic temperature, and the exponent υ is 1/(d+1) with d = 3 (the fitting results are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. A transition temperature TV is marked as the onset temperature of 3D-MVH behavior). The variable-range-hopping characteristic temperature T0 calculated is ∼1,400 K for the as-grown sample. The magnetic susceptibility of the same sample shows paramagnetic behavior as the sample cools down from 300 K, and a sudden drop in susceptibility appears at about the same temperature as the resistance transition temperature (TV) ∼45 K. The sharp resistive rise and the diamagnetic drop are the two signatures for the Verwey transition observed in Fe3O4, which occurs at 125 K. These results are also in line with those reported results in the Fe4Se5 nanowire, which was recently demonstrated to exhibit the Verwey-like electronic correlation [45].

FIGURE 2. (A) Temperature-dependent resistance of the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample showing a metal-insulator transition TV with the onset of resistance rise at ∼45 K. The inset is the magnetic susceptibility from 300 to 2 K of the same sample, which shows a large drop in susceptibility with the onset temperature also at ∼45 K. (B) Temperature-dependent resistance of the Fe4Se5 sample after 450°C RTA process. The sample becomes metallic and shows superconducting transition with the onset Tc∼7.8 K, as highlighted in the upper-left inset. The lower-right inset is the magnetic susceptibility which further demonstrates the superconducting transition with Tc∼7.9 K.

Figure 2B shows the temperature-dependence resistance for the Fe4Se5 samples after 300° and 450 C RTA process. The sample after 300°C remains to behave like semiconductor. The sample treated at 450° and 300°C changes to metallic and becomes superconducting below ∼5 K with the onset superconductive critical temperature (Tc) ∼7.8 K, as evidenced in the upper-left inset of Figure 2B. The lower-right inset is the magnetic susceptibility, which further demonstrates the superconducting transition with onset Tc ∼ 7.9 K. The evolution to superconductivity in this RTA-treated sample is similar to that reported in the K2-xFe4+ySe5 system, where superconductivity appears after Fe vacancies becoming disordered through high-temperature annealing and rapid quenching processes [43[44].

XPS and Hall Measurement of Fe4Se5

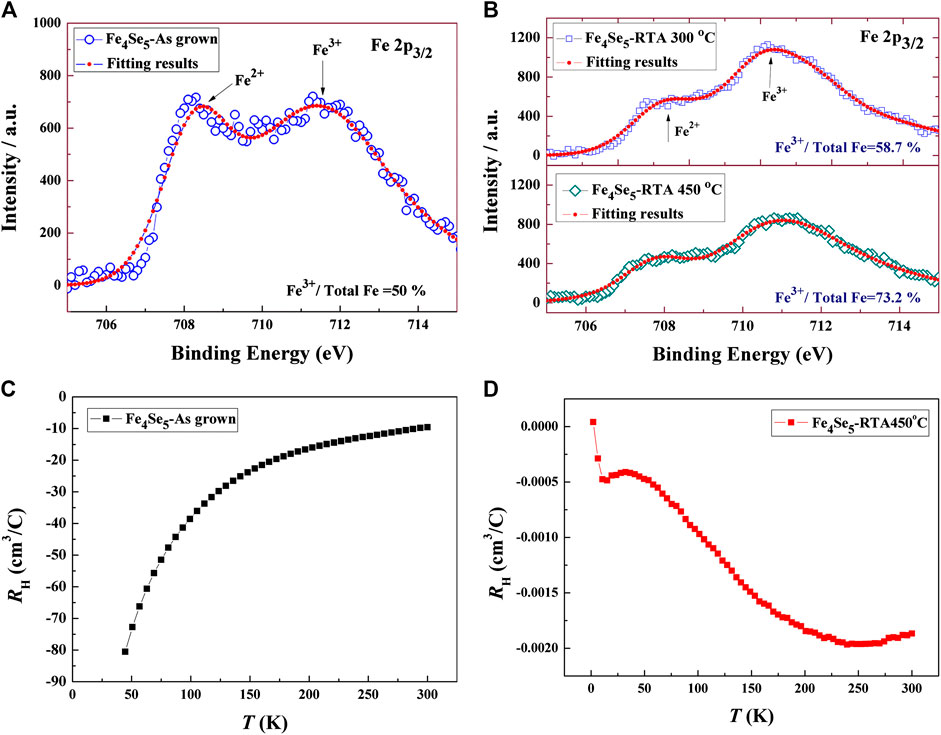

In order to gain more insight into the observed Verwey-like electronic correlation, XPS at room temperature and temperature-dependent Hall measurements on the samples were performed. Figure 3A is the observed XPS results for the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample. Figure 3A is the observed XPS results for the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample. The XPS spectrum clearly reveals two peaks showing the existence of mixed-valence states of Fe. The observed two peaks, at 708.5 and 711.5 eV, can be associated with the Fe2+ and Fe3+ states, respectively. The best data fitting gives the ratio between Fe2+ and Fe3+ close to 1 : 1. This result is similar to that observed in the magnetite Fe3O4.

FIGURE 3. Fe2p3/2 spectrum of XPS analysis for (A) the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample and (B) the 300° and 450°C RTA-treated Fe4Se5 sample. The temperature-dependent Hall coefficient for (C) the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample and (D) the 450°C RTA-treated Fe4Se5 sample.

Figure 3B displays the XPS results for samples with RTA treated at 300° and 450°C. After the RTA treatment, the Fe3+ state becomes dominant. The extracted Fe3+ ion to total Fe atoms ratio is 58.7% for 300°C RTA-treated and 73.2% for 450°C RTA-treated samples, respectively, indicating a substantial increase in electron carriers in these samples. It should be noted that the sample after 300°C still exhibits temperature-dependent behavior like semiconductor. There is no specific difference of Se 3d peak at 54.7 eV before and after the RTA process of the Fe4Se5 sample according to the XPS result, as shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

It is known that tetragonal FeSe is a metal with two-band based on the first-principles electronic structure calculation, for example, by T. Xiang et al., [46]. T. Xiang et al. also reported that the electronic structure of Fe4Se5 with √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy order is a pair checkboard antiferromagnetic insulator. The calculation shows that the Fe-vacancy-ordered Fe4Se5 has a single-band structure with n-type carrier dominated and a bandgap ∼290 meV. Berlijn et al. [47] investigated the effect of disordered Fe vacancies on the normal-state electronic structure of the alkali-intercalated FeSe system, where the KFe4Se5 exhibits exactly the same Fe-vacancy order as that in Fe4Se5. They found that the disorder of Fe-vacancy can effectively raise the chemical potential giving enlarged electron pockets without adding carriers to the system.

It is noted that, as reported by Chen et al. [38], there exists a series of FexSey compounds with x/y = 1/2, 2/3, 3/4, 4/5, etc. We have carried out a systematic study using the coprecipitation method to successfully prepare tetragonal Fe(1-x)Se with stoichiometry of Fe3Se4 and Fe4Se5. Based on the XPS results, the observed Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio is 2 and 1 for tetragonal Fe3Se4 and Fe4Se5, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4A and Figure 3A. These data imply that Fe3Se4 would be hole-doped and Fe4Se5 be electron-doped if there are additional carriers based on the simple charge balance picture by considering Fe3Se4 to be the combination of Fe(2+)Se and Fe2(3+)Se3, whereas Fe4Se5 is from 2(Fe(2+)Se) and Fe2(3+)Se3. Indeed, our Hall measurement results show at 300 K a hole concentration of 1.20 × 1019/cm3 for Fe3Se4 (Supplementary Figure S4B) and electron concentration of −6.52 × 1017/cm3 for Fe4Se5.

Both of the as-grown and RTA-treated Fe4Se5 show a single-band behavior with n-type carrier from the Hall resistivity measurements, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5. The Hall coefficient of the as-grown sample at room temperature is −9.59 cm3/C, corresponding to the electron carrier concentration of 6.52 × 1017 cm−3, and the carrier concentration decreases by about a factor of 8 at the transition temperature TV, as shown in Figure 3C.

After the Fe4Se5 sample is RTA-treated at 450 °C, the Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio becomes close to 3 : 1, which means that a large number of electrons are introduced and subsequently induced superconductivity. Indeed, the Hall measurement results, as shown in Figure 3D, show that the carrier concentration at 300 K increases to −3.34 × 1021/cm3 (Hall coefficient −1.87 × 10−3 cm3/C) for 450 C RTA-treated sample. The electron carrier concentration is about four orders of magnitude increase comparing with the as-grown Fe4Se5. Obviously, the RTA treatment disrupts the Fe-vacancy long-range order and leads to the increase of electron carriers.

Neutron Diffraction of Fe4Se5

It is well known that the Verwey transition in magnetite exhibits a structural transition accompanied by the sharp resistive and magnetic susceptibility changes. To examine whether such a structural change exists for the as-grown Fe4Se5, we have carried out the neutron diffraction at low temperatures.

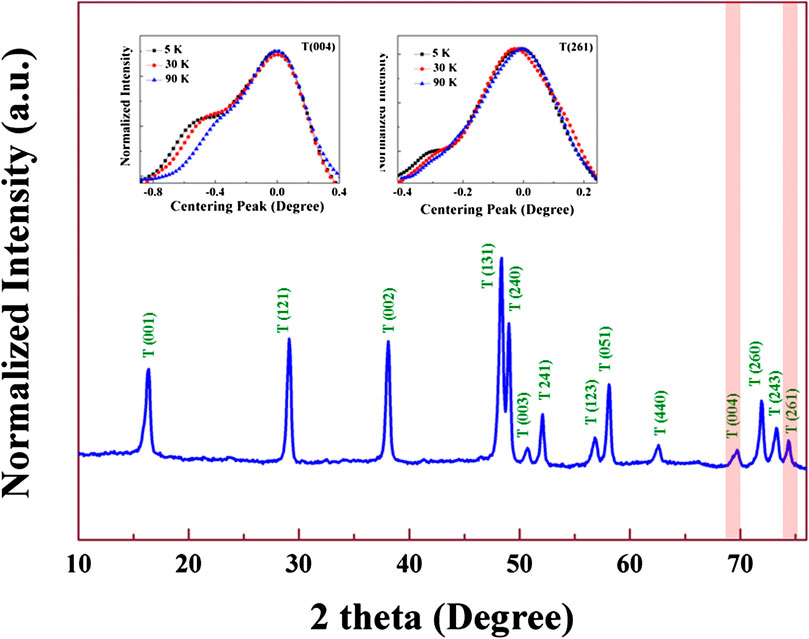

The detailed structural information of the as-grown Fe4Se5 sample measured by neutron diffraction at different temperatures is shown in Figure 4. At room temperature, the neutron data, consistent with XRD results, fit well with the P4-tetragonal symmetry. At low temperatures, a distortion appears at temperatures below 30 K. The data at 5 K, with evident peak emergence shown in the inset of Figure 4, indicates a possible structural change. This result further supports that the as-grown Fe4Se5 nanosheets, similar to the results observed in Fe4Se5 nanowire, show the Verwey-like correlation. The Verwey-like transition temperature of ∼45 K in nanosheets is higher than that observed in the nanowire, which was found to be ∼30 K. This shows the size dependence of TV, which is also noticed in Verwey transition [48–50]. Currently, we are waiting for the results of the detailed high-resolution XRD at low temperatures using a synchrotron source to determine exactly the low-temperature phase and the transition temperature.

FIGURE 4. The neutron diffraction patterns of as-grown Fe4Se5 nanosheet at 300 K. The tetragonal P4 symmetry is identified. The insets are the diffraction peaks of (004) and (261) at low temperatures showing the growth of additional peaks, indicating a structural change at low temperature.

Conclusion

We carried out a detailed study to investigate whether there exists an insulating parent phase for FeSe superconductors. Our studies unambiguously show that 1) the √5 × √5 Fe-vacancy-ordered Fe4Se5 is a Mott insulator with Verwey-like transition at low temperature; 2) Fe4Se5 is the parent compound of the FeSe superconductors. The application of the RTA process at 450°C disrupts Fe-vacancy order and induces more electron carriers by increasing the Fe3+ valence state. Superconductivity emerges with Tc ∼ 8 K without changing the chemical stoichiometry of the sample after the RTA process. Consistent with the observations in K2Fe4+xSe5, superconductivity is directly related to the disappearance of Fe-vacancy long-range order. In the Fe4Se5 case, no extra Fe doping is required as the random occupation of Fe atom in the vacancy sites, resulting in the addition of extra carriers in favor of superconductivity. More detailed evolution of superconductivity by varying the RTA temperature and time is currently underway in order to gain more insight into the exact phase diagram of the FeSe superconductors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

MJW and MKW designed research. KYY, TSL, and YRC performed research. MJW and KSCL contributed new reagents/analytic tools. KYY, TSL, PMW, YRC, KSCL, MJW, and MKW analyzed data and took part in physics discussions. KYY, MJW, TSL, PMW, and MKW wrote the paper.

Funding

The work is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology under Grant No. MOST108-2633-M-001-001 and Academia Sinica Thematic Research Grant No. AS-TP-106-M01.

Conflict of Interest

Author PMW is employed by the company BitSmart LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate very much the help from Dr. G. T Huang for synchrotron XRD measurements and Dr. C. P. Yen for the analysis of XPS results. We thank the technical support from NanoCore, the Core Facilities for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at Academia Sinica in Taiwan.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2020.567054/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Kamihara Y, Watanabe T, Hirano M, Hosono H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05-0.12) with Tc = 26 K. J Am Chem Soc. (2008). 130:3296. doi:10.1021/ja800073m

2. Hsu FC, Luo JY, Yeh KW, Chen TK, Huang TW, Wu PM, et al. . Superconductivity in the PbO-type structure α-FeSe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008). 105:14262. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807325105

3. Peng R, Xu HC, Tan SY, Cao H, Xia M, Shen XP, et al. . Tuning the band structure and superconductivity in single-layer FeSe by interface engineering. Nat Commun. (2014). 5:5044. doi:10.1038/ncomms6044

4. Yi M, Zhang Y, Shen ZX, Lu D. Role of the orbital degree of freedom in iron-based Superconductors. Npj Quantum Mater. (2017). 2:57. doi:10.1038/s41535-017-0059-y

5. Fernandes RM, Chubukov AV, Schmalian J. Magnetically driven suppression of nematic order in an iron-based superconductor. Nat Phys. (2014). 10:97. doi:10.1038/NPHYS2877

6. Yu R, Zhu JX, Si Q. Orbital selectivity enhanced by nematic order in FeSe. Phys Rev Lett. (2018). 121:227003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.227003

7. Saito T, Onari S, Kontani H. Orbital fluctuation theory in iron pnictides: effects of As–Fe–As bond angle, isotope substitution, and Z2-orbital pocket on superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B. (2010). 82:144510. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.82.144510

8. Kontani H, Onari S. Orbital-fluctuation-mediated superconductivity in iron pnictides: analysis of the five-orbital Hubbard–Holstein model. Phys Rev Lett. (2010). 104:157001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.157001

9. Yu W, Aczel AA, Williams TJ, Bud’ko SL, Ni N, Canfield PC, et al. . Absence of superconductivity in single-phase CaFe2As2 under hydrostatic pressure. Phys Rev B. (2009). 79:020511. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.020511

10. Goldman AI, Argyriou DN, Ouladdiaf B, Chatterji T, Kreyssig A, Nandi S, et al. . Lattice and magnetic instabilities in CaFe2As2: a single-crystal neutron diffraction study. Phys Rev B. (2008). 78:100506. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.100506

11. Margadonna S, Takabayashi Y, McDonald MT, Kasperkiewicz K, Mizuguchi Y, Takano Y, et al. . Crystal structure of the new FeSe1−x superconductor. Chem. Commun. (2008). 0:5607. doi:10.1039/b813076k

12. McQueen TM, Williams AJ, Stephens PW, Tao J, Zhu Y, Ksenofontov V, et al. . Tetragonal-to-orthorhombic structural phase transition at 90 K in the superconductor Fe1.01Se. Phys Rev Lett. (2009). 103:057002. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.057002

13. Bendele M, Amato A, Conder K, Elender M, Keller H, Klauss H-H, et al. . Pressure induced static magnetic order in superconducting FeSe1−x. Phys Rev Lett. (2010). 104:087003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.087003

14. Baek SH, Efremov DV, Ok JM, Kim JS, Brink JVD, Bchner B. Orbital-driven nematicity in FeSe. Nat Mater. (2015). 14:210. doi:10.1038/NMAT4138

15. Bohmer AE, Arai T, Hardy F, Hattori T, Iye T, Wolf T, et al. . Origin of the tetragonal-to-orthorhombic phase transition in FeSe:A combined thermodynamic and NMR study of nematicity. Phys Rev Lett. (2015). 114:027001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.027001

16. Chubukov AV, Fernandes RM, Schmalian J. Origin of nematic order in FeSe. Phys Rev B. (2015). 91:201105. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.91.201105

17. Glasbrenner JK, Mazin , Jeschke HO, Hirschfeld PJ, Fernandes RM, Valentł R. Effect of magnetic frustration on nematicity and superconductivity in iron chalcogenides. Nat Phys. (2015). 11:953. doi:10.1038/NPHYS3434

18. Wang F, Kivelson SA, Lee DH. Nematicity and quantum paramagnetism in FeSe. Nat Phys. (2015). 11:959. doi:10.1038/NPHYS3456

19. Yu R, Si QM. Antiferroquadrupolar and ising-nematic orders of a frustrated bilinear-biquadratic heisenberg model and implications for the magnetism of FeSe. Phys Rev Lett. (2015). 115:116401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.116401

20. Wang QS, Shen Y, Pan BY, Hao YO, Ma MW, Zhou F, et al. . Strong interplay between stripe spin fluctuations, nematicity and superconductivity in FeSe. Nat Mater. (2016). 15:159. doi:10.1038/NMAT4492

21. Bendele M, Ichsanow A, Pashkevich Y, Keller L, Strässle Th, Gusev A, et al. . Coexistence of superconductivity and magnetism in FeSe1−x under pressure. Phys. Rev. B. (2012). 85:064517. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.064517

22. Mizuguchi Y, Tomioka F, Tsuda S, Yamaguchi T, Takano Y. Superconductivity at 27 K in tetragonal FeSe under high pressure. Appl. Phys. Lett. (2008). 93:152505. doi:10.1063/1.3000616

23. Medvedev S, McQueen T, Troyan I, Palasyuk T, Eremets M, Cava R, et al. Electronic and magnetic phase diagram of β-Fe1.01 with superconductivity at 36.7 K under pressure. Nat. Mater. (2009). 8:630. doi:10.1038/NMAT2491

24. Margadonna S, Takabayashi Y, Ohishi Y, Mizuguchi Y, Takano Y, Kagayama T, et al. Pressure evolution of the low-temperature crystal structure and bonding of the superconductor FeSe (Tc = 37 K). Phys. Rev. B. (2009). 80:064506. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.064506

25. Garbarino G, Sow A, Lejay P, Sulpice A, Toulemonde P, Mezouar M, et al. High-temperature superconductivity (Tc onset at 34 K) in the high-pressure orthorhombic phase of FeSe. Europhys Lett. (2009). :86. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/86/27001

26. Masaki S, Kotegawa H, Hara Y, Tou H, Murata K, Mizuguchi Y, et al. Precise pressure dependence of the superconducting transition temperature of FeSe: resistivity and 77Se-NMR study. J Phys Soc Jpn. (2009). 78:063704. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.78.063704

27. Okabe H, Takeshita N, Horigane K, Muranaka T, Akimitsu J. Pressure-induced high-Tc superconducting phase in FeSe: correlation between anion height and Tc. Phys Rev B. (2010). 81:205119. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.81.205119

28. Wang QY, Li Z, Zhang WH, Zhang ZC, Zhang JS, Li W, et al. Interface-induced high-temperature superconductivity in single unit-cell FeSe films on SrTiO3. Chin Phys Lett. (2012). 29:037402. doi:10.1088/0256-307X/29/3/037402

29. Liu DF, Zhang WH, Mou DX, He JF, Ou YB, Wang QY, et al. Electronic origin of high-temperature superconductivity in single-layer FeSe superconductor. Nat Commun. (2012). 3:931. doi:10.1038/ncomms1946

30. He SL, He JF, Zhang WH, Zhao L, Liu DF, Liu X, et al. Phase diagram and electronic indication of high-temperature superconductivity at 65 K in single-layer FeSe films. Nat Mater. (2013). 12:605. doi:10.1038/NMAT3648

31. Tan SY, Zhang Y, Xia M, Ye ZR, Chen F, Xie X, et al. Interface-induced superconductivity and strain-dependent spin density waves in FeSe/SrTiO3 thin films. Nat Mater. (2013). 12:634. doi:10.1038/NMAT3654

32. McQueen TM, Huang Q, Ksenofontov V, Felser C, Xu Q, Zandbergen H, et al. Extreme sensitivity of superconductivity to stoichiometry in Fe1+δSe. Phys Rev B. (2009). 79(1):014522. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.014522

33. Liu TJ, Hu J, Qian B, Fobes D, Mao ZQ, Bao W, et al. From (π,0) magnetic order to superconductivity with (π,π) magnetic resonance in Fe1.02Te1−xSex. Nat Mater. (2010). 9:718. doi:10.1038/NMAT2800

34. Chang CC, Wang CH, Wen MH, Wu YR, Hsieh YT, Wu MK. Superconductivity in PbO-type tetragonal FeSe nanoparticles. Solid State Commun. (2012). 152:649. doi:10.1016/j.ssc.2012.01.030

35. Zhou Y, Xu DH, Zhang FC, Chen WQ. Theory for superconductivity in (Tl,K)FexSe2 as a doped Mott insulator. Europhys Lett. (2011). 95:17003. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/95/17003

36. Yu R, Zhu JX, Si Q. Mott transition in modulated lattices and parent insulator of (K; Tl) yFexSe2 superconductors. Phys Rev Lett. (2011). 106:186401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.186401

37. Zhao X, Ma F, Lu ZY, Xiang T. AFeSe2 (A = Tl, K, Rb, or Cs): iron-based superconducting analog of the cuprates. Phys Rev B. (2020). 101:184504. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.101.184504

38. Chen TK, Chang CC, Chang HH, Fang AH, Wang CH, Chao WH, et al. Fe-vacancy order and superconductivity in tetragonal β-Fe1-xSe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014). 111:63. doi:10.1073/pnas.1321160111

39. Bao W, Huang QZ, Chen GF, Green MA, Wang DM, He JB, et al. A novel large moment antiferromagnetic order in K0.8Fe1.6Se2 superconductor. Chin Phys Lett. (2011). 28:086104. doi:10.1088/0256-307X/28/8/086104

40. Zhao J, Cao H, Bourret-Courchesne E, Lee DH, Birgeneau RJ. Neutron-diffraction measurements of an antiferromagnetic semiconducting phase in the vicinity of the high-temperature superconducting state of KxFe2−ySe2. Phys Rev Lett. (2012). 109:267003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.267003

41. Liu RH, Luo XG, Zhang M, Wang AF, Ying JJ, Wang XF, et al. Coexistence of superconductivity and antiferromagnetism in single crystals A0.8Fe2−ySe2 (A = K, Rb, Cs, Tl/K and Tl/Rb): evidence from magnetization and resistivity. Europhys Lett. (2011). 94:27708. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/94/27008

42. Fang MH, Wang HD, Dong CH, Li ZJ, Feng CM, Chen J, et al. Fe-based superconductivity with Tc = 31 K bordering an antiferromagnetic insulator in (Tl,K) FexSe2. Europhys Lett. (2011). 94:27009. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/94/27009

43. Wang CH, Chen TK, Chang CC, Hsu CH, Lee YC, Wang MJ, et al. Disordered Fe vacancies and superconductivity in potassium-intercalated iron selenide (K2−xFe4+y Se5). Europhys Lett. (2015). 111:27004. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/111/27004

44. Wang CH, Lee CC, Huang GT, Yang JY, Wang MJ, Sheu HS, et al. Role of the extra Fe in K2−xFe4+ySe5 superconductors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019). 116:1104. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815237116

45. Yeh KY, Lo TS, Wu PM, Chang-Liao KS, Wang MJ, Wu MK. Magneto-transport studies of Fe-vacancy ordered Fe4+δSe5 nanowires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020). 116:1104. doi:10.1073/pnas.2000833117

46. Ma F, Ji W, Hu JP, Lu ZY, Xian T. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure of tetragonal α-FeTe and α-FeSe crystals: evidence for a bicollinear antiferromagnetic order. Phys Rev Lett. (2009). 102:177003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.177003

47. Berlijn T, Hirschfeld PJ, Ku W. Effective doping and suppression of fermi surface reconstruction via Fe vacancy disorder in KxFe2-ySe2. Phys Rev Lett. (2012). 109:47003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.147003

48. Zisese M, Blythe HJ. Magnetoresistance of magnetite. J Phys Condens Matter. (2000). 13:12. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/12/1/302

49. Bohra M, Agarwal N, Sigh V. A short review on Verwey transition in nanostructured Fe3O4 materials. J Nanomater. (2019). 1:18. doi:10.1155/2019/8457383

Keywords: FeSe superconductors, Verwey-like transition, Fe-vacancy order, Mott insulators, Mixed-valence state

Citation: Yeh K-Y, Chen Y-R, Lo T-S, Wu PM, Wang M-J, Chang-Liao K-S and Wu M-K (2020) Fe-Vacancy-Ordered Fe4Se5: The Insulating Parent Phase of FeSe Superconductor. Front. Phys. 8:567054. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.567054

Received: 29 May 2020; Accepted: 30 September 2020;

Published: 13 November 2020.

Edited by:

Jun Zhao, Fudan University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Yeh, Chen, Lo, Wu, Wang, Chang-Liao and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maw-Kuen Wu, bWt3dUBwaHlzLnNpbmljYS5lZHUudHc=

Keng-Yu Yeh

Keng-Yu Yeh Yan-Ruei Chen

Yan-Ruei Chen Tung-Sheng Lo1

Tung-Sheng Lo1 Ming-Jye Wang

Ming-Jye Wang Maw-Kuen Wu

Maw-Kuen Wu