- 1Institute of Computing Science and Technology, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Mathematics, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore, Pakistan

- 3Mazandaran Adib Institute of Higher Education, Sari, Iran

The purpose of this research study is to present and explore the key properties of some new operations on vague graphs, including rejection, maximal product, symmetric difference, and residue product. This article introduces the notions of degree of a vertex and total degree of a vertex in a vague graph. As well, this study outlines the specific conditions required for obtaining the degrees of vertices in vague graphs under the operations of maximal product, symmetric difference, and rejection. The article also discusses applications of vague sets in medical diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Graph theory is an extremely useful tool for solving combinatorial problems in a wide range of fields, including geometry, algebra, number theory, topology, operations research, biology, and social systems. Graph theory also has many applications of great scope, such as in networking, image capture, clustering, handling uncertainty, image segmentation, finding communities in networks, bioscience, information technology, operations research, and social science networks consisting of points connected by lines. In fact, graph theory studies connections between objects, such as vertices and edges and the various relations between them. Fuzzy graph theory is finding an increasing number of applications in modeling real-time systems, where the amount of information inherent in the system varies with different levels of precision. In 1965, Zadeh [1] first proposed the theory of fuzzy sets. The fuzzy graph, with the approximate reasoning, enables many combinatorial problems in fields, such as topology and algebra to be solved more easily. The concept of fuzzy graphs is discussed by Rosenfeld [2] as well as by Bhattacharya [3, 4]. Fuzzy graphs date back to the nineteenth century, and their use has grown tremendously in recent years [5, 6]. Gau and Buehrer [7] proposed the concept of vague set in 1993, which replaces the value of an element in a set with a subinterval of [0, 1]. Specifically, a true-membership function tv(x) and a false-membership function fv(x) are used to describe the boundaries of the membership degree. Descriptions of real-world problems can be improved by using the theory of vague sets. Researchers have applied this theory to several real-world situations, such as decision-making and fuzzy control. The theory of vague sets is also helpful for fault diagnosis and knowledge discovery. Interval-valued fuzzy sets have a case vague set, which has been applied in different fields of mathematics. Ramakrishna [8] introduced the concept of vague graph and also studied related properties. Vague graphs have numerous applications in geometry and operations research and are also useful in many areas of computer science. Rashmanlou and Borzooei [9] studied new concepts relating to vague graphs, product vague graphs [10], regularity of vague graphs [11], and vague competition graphs [12]. Krishna and Lavanya [13] developed new concepts of coloring in vague graphs. Besides the membership degree, the non-membership degree has been introduced as well, which is presented by Atanassove [14] in an intuitionistic fuzzy set, a type of extension of a fuzzy set. Parvathi and Karunambigai [15] discussed intuitionistic fuzzy graphs. Devi et al. [16] presented new concepts regarding intuitionistic fuzzy labeling graphs.

In this study we outline and explore the key properties of some new operations on vague graphs, including rejection, maximal product, symmetric difference, and residue product. We introduce new notions, such as degree of a vertex and total degree of a vertex in a vague graph. We also outline specific conditions for obtaining the degrees of vertices in vague graphs under the operations of maximal product, symmetric difference, and rejection. Furthermore, we explore applications of vague sets in medical diagnosis.

2. Preliminaries

In this section we introduce the key preliminary notions and definitions that are used in this study.

Definition 2.1 ([17]). A graph is an ordered pair G = (V, E), where V is the set of vertices of G and E is the set of all edges, arcs, or lines, which are two-element subsets of V (that is, an edge is related to two vertices and the relation is represented as an unordered pair {m, n} of those vertices).

Note that for an edge {m, n}, graph theorists usually use the somewhat shorter notation mn. Two vertices m and n in an undirected graph G are said to be adjacent in G if mn is an edge of G. An edge whose endpoints are the same is called a loop. A graph without loops is called a simple graph.

Definition 2.2 ([7]). A vague set M is a pair (TM; FM) of functions on a set V, where TM and FM are real-valued V → [0, 1] functions such that TM(m) + FM(m) < 1 for all m ∈ V. The interval [TM(m), 1 − FM(m)] is known as the vague value of m in M.

In this definition, for m in M, TM(m) is the lower bound for the degree of membership and FM(m) is the lower bound for the negative of the degree of membership. Therefore, the degree of membership of m ∈ M is given by the interval [TM(m), 1 − FM(m)].

Definition 2.3 ([8]). Let G = (V, E) be a crisp graph. A pair G = (M, N) is called a vague graph defined on the crisp graph G = (V, E) if M = (TM, FM) is a vague set on V and N = (TN, FN) is vague set on E ⊆ V × V such that TN(mn) ≤ min(TM(m), TM(n)) and FN(mn) ≥ max(FM(m), FM(n)) for each edge mn in E.

Definition 2.4 ([9]). A vague graph G is said to be strong if TN(mn) = min(TM(m), TM(n)) and FN(mn) = max(FM(m), FM(n)) for all m, n ∈ V.

Definition 2.5 ([9]). A vague graph G is said to be complete if TN(mn) = min(TM(m), TM(n)) and FN(mn) = max(FM(m), FM(n)) for all mn ∈ E.

Definition 2.6 ([11]). A vague graph G is said to be connected if and for all mi, mj ∈ V. Also, we have

and

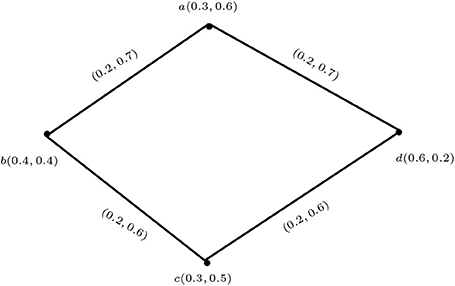

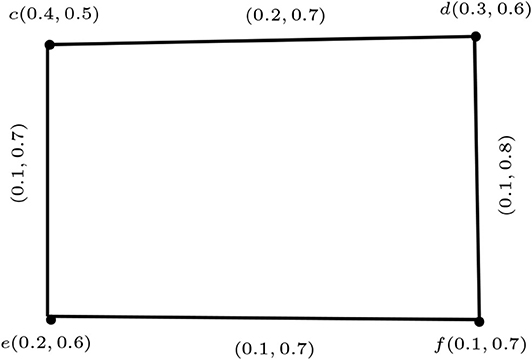

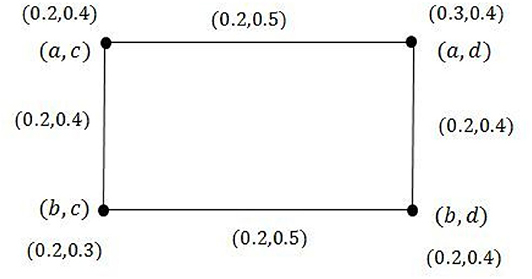

Example 2.7. Consider a vague graph G such that V = {a, b, c}, E = {ab, bc, cd, ad}, , and .

By routine computations, it is easy to show that G is a vague graph (Figure 1).

3. Operations on Vague Graphs

In this section we define four new kinds of operations on vague graphs: the maximal product, residue product, rejection, and symmetric difference. We show that the maximal product, residue product, or rejection of two vague graphs is again a vague graph.

Definition 3.1. The maximal product G1 * G2 = (M1*M2, N1*N2) of two vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is defined by

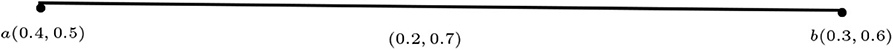

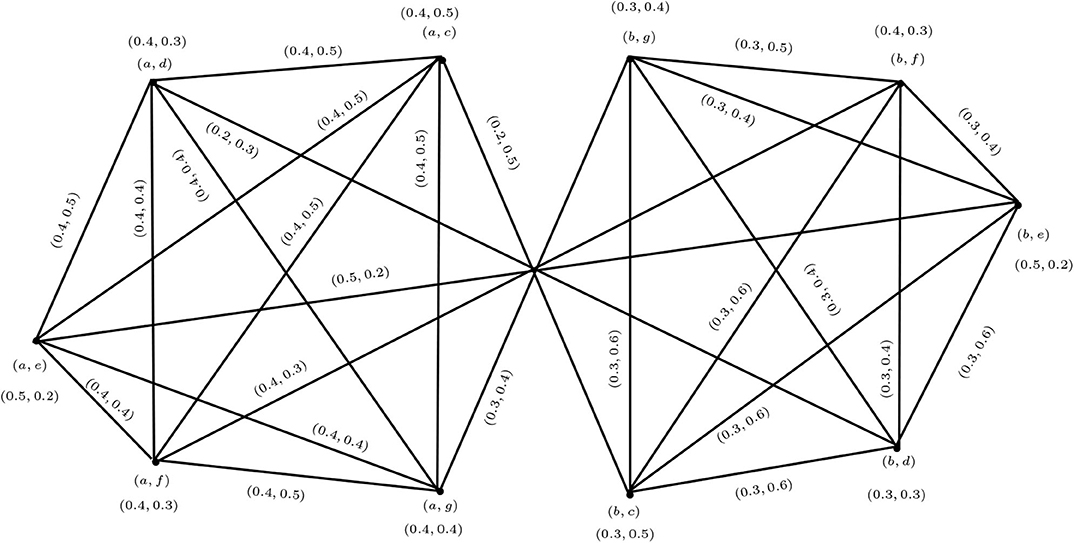

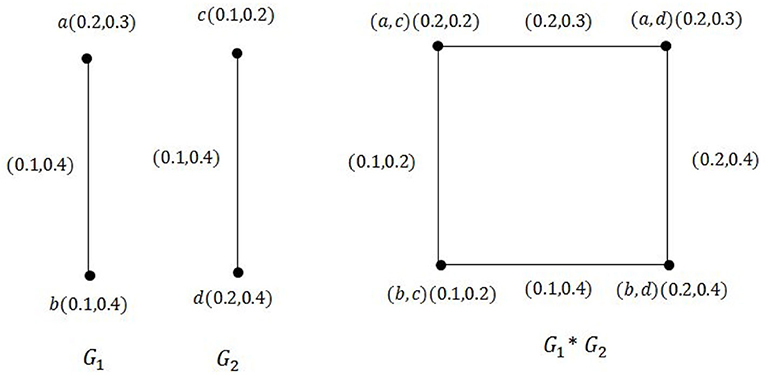

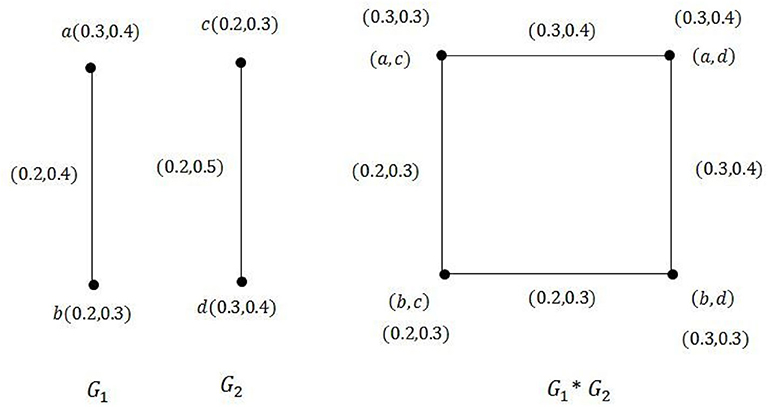

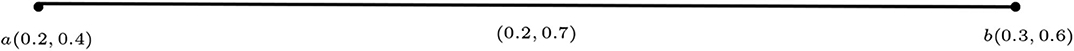

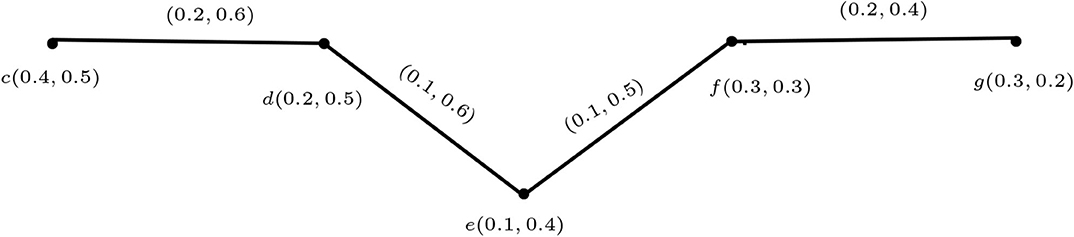

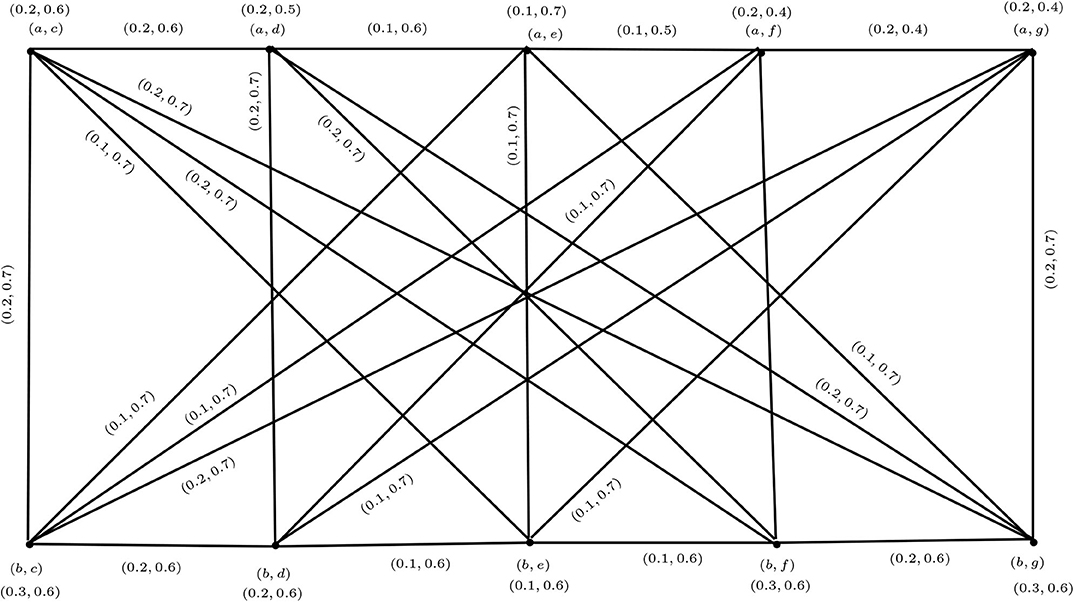

Example 3.2. Consider the two vague graphs G1 and G2 shown in Figures 2, 3. Their maximal product G1 * G2 is shown in Figure 4.

For the vertex (a, d), we find the membership and non-membership values as follows:

For the edge (a, d)(a, e), we find the following membership and non-membership values:

Now, for edge (a, g)(b, g) we have

Similarly, we can find the membership and non-membership values for all the remaining vertices and edges.

Proposition 3.3. The maximal product of two vague graphs G1 and G2 is a vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, and let ((m1, m2)(n1, n2)) ∈ E1 × E2. Then by Definition 3.1 we have two cases:

(i) If m1 = n1 = m, then

(ii) If m2 = n2 = z, then

Therefore, G1 * G2 is a vague graph. □

Theorem 3.4. The maximal product of two strong vague graphs G1 and G2 is a strong vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two strong vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, and let ((m1, m2)(n1, n2)) ∈ E1 × E2. Then, by Proposition 3.3, G1 * G2 is a vague graph. Now we have two cases:

(i) If m1 = n1 = m, then

(ii) If m2 = n2 = z, then

Therefore, G1 * G2 is a strong vague graph. □

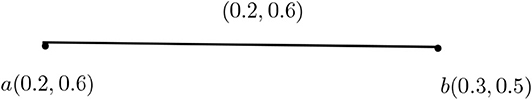

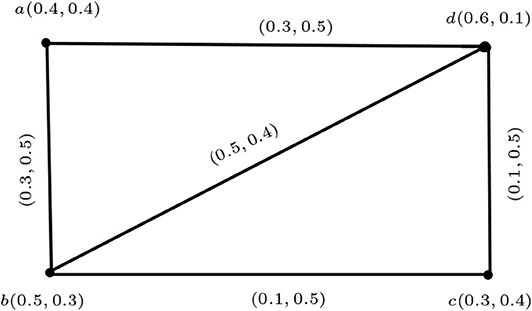

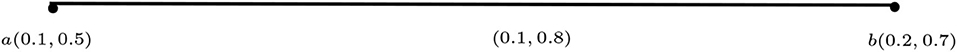

Example 3.5. Consider the strong vague graphs G1 and G2 as in Figure 5.

It is easy to see that G1 * G2 is a strong vague graph too.

Remark 3.1. If the maximal product of two vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is a strong vague graph, G1 and G2 need not be strong in general.

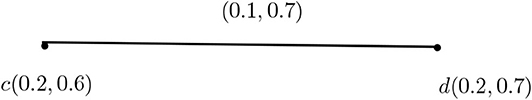

Example 3.6. Consider the vague graphs G1 and G2 as in Figures 6, 7. The maximal product of G1 and G2 is G1 * G2 shown in Figure 8.

We can see that G1 and G1 * G2 are strong vague graphs, but G2 is not strong: since TN2(m2, n2) = 0.1 but min{TM2(m2), TM2(n2} = min{0.2, 0.2} = 0.2, we have TN2(m2, n2) ≠ min{TM2(m2), TM2(n2}.

Theorem 3.7. The maximal product of two connected vague graphs is a connected vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two connected vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, where V1 = {m1, m2, …, mk} and V2 = {n1, n2, …, ns}. Then for all mi, mj ∈ V1 and for all ni, nj ∈ V2 (or for all mi, mj ∈ V1 and for all ni, nj ∈ V2). The maximal product of G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) can be taken as G = (M, N). Now, consider the k subgraphs of G with the vertex set {(mi, n1), (mi, n2), …, (mi, ns)} for i = 1, 2, …, k. Each of these subgraphs of G is connected, since the mi's are the same and G2 is connected, so that each ni is adjacent to at least one of the vertices in V2. Also, since G1 is connected, each xi is adjacent to at least one of the vertices in V1.

Hence, there exists at least one edge between any pair of the above k subgraphs. Thus, we have (or ) for all ((mi, nj)(mm, nn)) ∈ E. Therefore, G is a connected vague graph. □

Remark 3.2. The maximal product of two complete vague graphs is not a complete vague graph in general. This is because we do not include the case where (m1, m2) ∈ E1 and (n1, n2) ∈ E2 in the definition of the maximal product of two vague graphs.

Remark 3.3. The maximal product of two complete vague graphs is a strong vague graph.

Example 3.8. Consider the complete vague graphs G1 and G2 in Figure 5. A simple calculation yields that G1 * G2 is a strong vague graph.

Definition 3.9. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Theorem 3.10. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. If TM1 ≥ TN2, FM1 ≤ FN2, TM2 ≥ TN1, and FM2 ≤ FN1, then (dT)G1 * G2(m1, m2) = (d)G2(m2)TM1(m1) + (d)G1(m1)TM2(m2) and (dF)G1 * G2(m1, m2) = (d)G2(m2)FM1(m1) + (d)G1(m1)FM2(m2).

Proof: From the definition of a vertex in the cartesian product, we have

as claimed. □

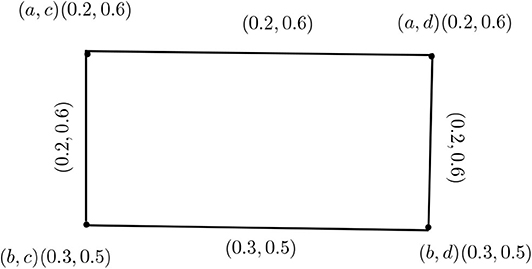

Example 3.11. Consider the vague graphs G1, G2, and G1 * G2 as in Figure 9. Since TM1 ≥ TN2, FM1 ≤ FN2, TM2 ≥ TN1, and FM2 ≤ FN1, by Theorem 3.10 we have

By direct calculations we obtain

It is clear that the degrees of vertices calculated using the formula in Theorem 3.10 and by the direct method are the same.

Definition 3.12. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Example 3.13. In this example we find the degree and the total degree of vertices (a, c) and (a, d) in Example 3.2:

Therefore, dG1 * G2(a, c) = (1.8, 1.5). In addition, by the definition of the total vertex degree in the maximal product,

Therefore, tdG1 * G2(a, c) = (2.2, 1.8).

We also have

Hence, dG1 * G2(a, d) = (1.7, 2.3) and tdG1 * G2(a, d) = (2.1, 2.6).

Similarly, we can find the degree and the total degree of all vertices in G1 * G2.

Theorem 3.14. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. If TM1 ≥ TN2, FM1 ≤ FN2, TM2 ≥ TN1, and FM2 ≤ FN1, then (tdT)G1 * G2(m1, m2) = (d)G2(m2)TM1(m1) + (d)G1(m1)TM2(m2) + max{TM1(m1), TM2(m2)} and (tdF)G1 * G2(m1, m2) = (d)G2(m2)FM1(m1) + (d)G1(m1)FM2(m2) + min{FM1(m1), FM2(m2)}.

Proof: From Definition 3.12 we have

and

as asserted.

Example 3.15. Consider the vague graphs G1, G2, and G1 * G2 in Figure 9. The total degree of the vertex in the maximal product is calculated by the following formula:

Using the formula we find that

On the other hand, by direct calculations we obtain

It is thus clear that the total degrees of vertices calculated using the formula and by the direct method are the same.

Definition 3.16. The rejection G1|G2 = (M1|M2, N1|N2) of two vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is defined as follows:

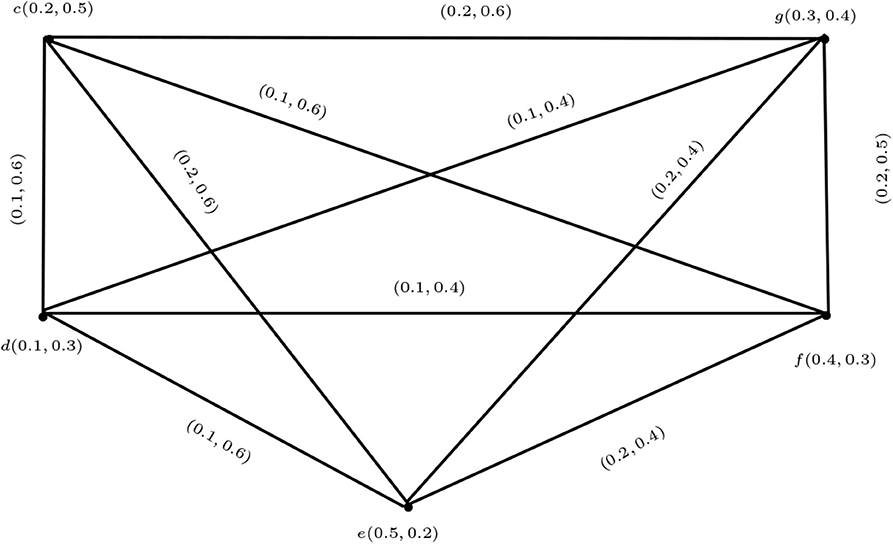

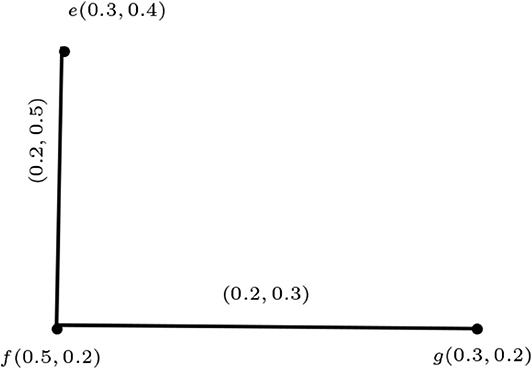

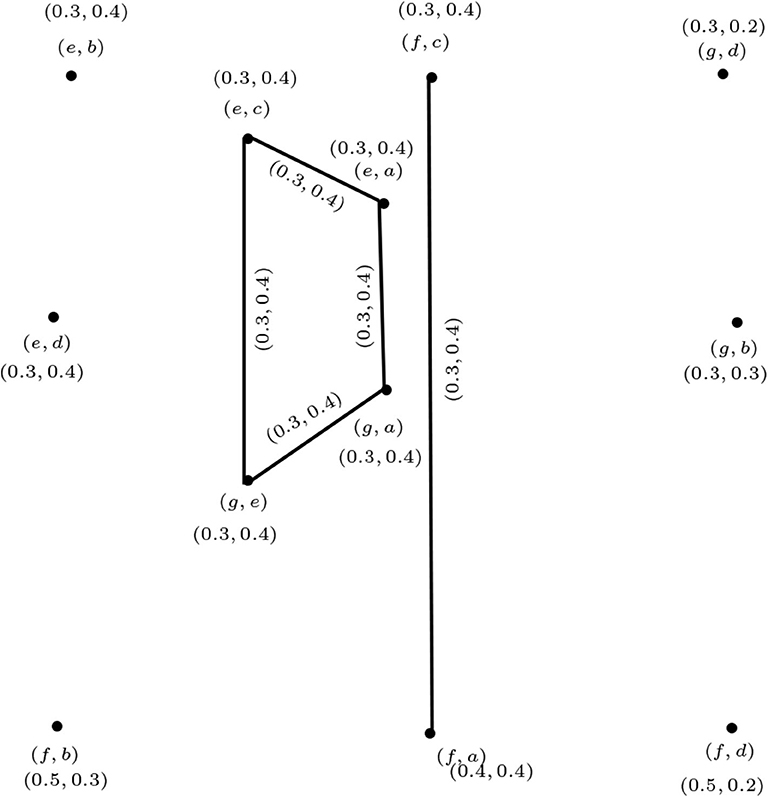

Example 3.17. Consider the vague graphs G1 and G2 in Figures 10, 11. The rejection of G1 and G2, i.e., G1|G2, is shown in Figure 12.

For the vertex (a, e), we find the membership and non-membership values as follows:

for a ∈ V1 and e ∈ V2.

For the edge (e, c)(e, a), the membership and non-membership values are given by

for e ∈ V2 and ac ∉ E1.

For the edge (e, c)(e, g) we have

for e ∈ V2 and cg ∉ E2.

Similarly, we can find the membership and non-membership values for all the remaining vertices and edges.

Proposition 3.18. The rejection of two vague graphs G1 and G2 is a vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, and let ((m1, m2)(n1, n2)) ∈ E1 × E2. Then by Definition 3.16 we have the following:

(i) If m1 = n1 and m2n2 ∉ E2, then

(ii) If m2 = n2 and m1n1 ∉ E1, then

(iii) If m1n1 ∉ E1 and m2n2 ∉ E2, then

Therefore, G1|G2 = (M1|M2, N1|N2) is a vague graph. □

Remark 3.4. The rejection of two complete vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is a complete vague graph.

Definition 3.19. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Definition 3.20. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Example 3.21. In this example we find the degree and total degree of the vertex (e, a) in Example 3.17:

Therefore, dG1|G2(a, c)= (0.6,0.8).

In addition, by the definition of the total vertex degree in the maximal product,

Therefore, tdG1|G2(a, c)= (0.9,1.2).

Similarly, we can find the degree and the total degree of all vertices in G1|G2.

Definition 3.22. The symmetric difference G1 ⊕ G2 = (M1 ⊕ M2, N1 ⊕ N2) of two vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is defined as follows:

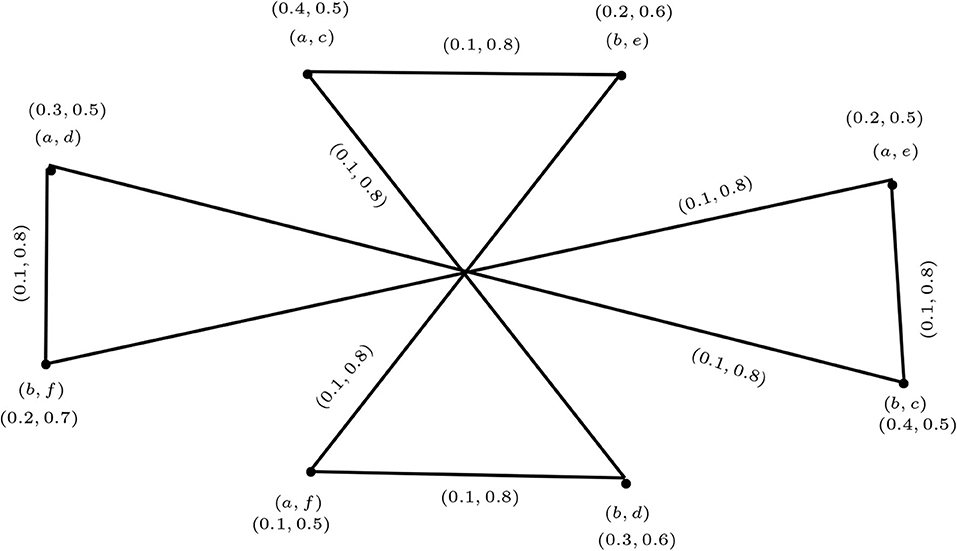

Example 3.23. Consider the vague graphs G1 and G2 as in Figures 13, 14. The symmetric difference of G1 and G2, i.e., G1 ⊕ G2, is shown in Figure 15.

For the vertex (a, f), we find the membership and non-membership values as follows:

for a ∈ V1 and f ∈ V2.

For the edge (a, d)(a, e), the membership and non-membership values are given by

for a ∈ V1 and de ∈ E2.

For the edge (a, d)(b, d) we have

for ab ∈ E1 and d ∈ V2.

For the edge (a, c)(b, f), the membership and non-membership values are

for ab ∈ E1 and cf ∉ E2.

In the same way, we can find the membership and non-membership values for all remaining vertices and edges.

Proposition 3.24. The symmetric difference of two vague graphs G1 and G2 is a vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, and let ((m1, m2)(n1, n2)) ∈ E1 × E2. Then by Definition 3.22 we have the following cases:

(i) If m1 = n1 = m, then

(ii) If m2 = n2 = z, then

(iii) If m1n1 ∉ E1 and m2n2 ∈ E2, then

(iv) If m1n1 ∈ E1 and m2n2 ∉ E2, then

Hence G1 ⊕ G2 is a vague graph. □

Remark 3.5. The symmetric difference of two connected vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is connected, because we include the case where (m1, m2) ∈ E1 and (n1, n2) ∈ E2 in the definition of the symmetric difference of two vague graphs.

Definition 3.25. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

and

Theorem 3.26. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. If TM1 ≥ TN2, FM1 ≤ FN2, TM2 ≥ TN1, and FM2 ≤ FN1, then for every (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we have (d)G1 ⊕ G2(m1, m2) = q(d)G1(m1) + s(d)G2(m2), where s = |V1| − (d)G1(m1) and q = |V2| − (d)G2(m2).

Proof: Using Definition 3.25,

and hence the result is proved. □

Example 3.27. Consider the two vague graphs G1 and G2 in Figure 9 and their symmetric difference in Figure 16. In Figure 9, TM1 ≥ TN2, FM1 ≤ FN2, TM2 ≥ TN1, and FM2 ≤ FN1. Then, the total degree of a vertex in the symmetric difference is calculated by the following formula:

Figure 16. G1 ⊕ G2 of the vague graphs in Figure 9.

Using the formula we find that

Hence, (d)G1 ⊕ G2(a, c) = (0.4, 0.9) and (d)G1 ⊕ G2(a, d) = (0.4, 0.9).

In the same way, we can show that (d)G1 ⊕ G2(b, c) = (d)G1 ⊕ G2(b, d) = (0.4, 0.9). Direct calculations give

It is obvious from the above that the degrees of vertices calculated using the formula and by the direct method are the same.

Definition 3.28. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

and

Example 3.29. In this example we find the degree and total degree of the vertex (a, e) in Example 3.23. We have

and, similarly,

Therefore

So

In addition, by Definition 3.28 we have

Therefore,

Similarly, we can find the degree and total degree of all vertices in G1 ⊕ G2.

Theorem 3.30. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs.

(i) If TM1 ≥ TN2 and TM2 ≥ TN1, then for all (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2,

(ii) If FM1 ≤ FN2 and FM2 ≤ FN1, then for all (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2,

Here s = |V1|−(d)G1(m1) and q = |V2|−(d)G2(m2).

Proof: For all (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we have

where s = |V1|−(d)G1(m1) and q = |V2|−(d)G2(m2). □

Example 3.31. In this example, we calculate the total degree of the vertices in Example 3.27.

The total degree of a vertex in the symmetric difference is given by

Using the above formula, we calculate

By direct calculations, we find

It is clear that the total degrees of vertices calculated using the formula and by the direct method are the same.

Definition 3.32. The residue product G1 • G2 = (M1 • M2, N1 • N2) of two vague graphs G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) is defined as follows:

Example 3.33. Consider the vague graphs G1 and G2 in Figures 17, 18. The residue product of G1 and G2, i.e., G1 • G2, is shown in Figure 19.

For the vertex (b, e), we find the membership and non-membership values as follows:

for b ∈ V1 and e ∈ V2.

For the edge (a, c)(b, d), we calculate the membership and non-membership values to be

for ab ∈ E1 and c ≠ d.

Similarly, we can find the membership and non-membership values for all the remaining vertices and edges.

Proposition 3.34. The residue product of two vague graphs G1 and G2 is a vague graph.

Proof: Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs on crisp graphs G1 = (V1, E1) and G2 = (V2, E2), respectively, and let ((m1, m2)(n1, n2)) ∈ E1 × E2. If m1n1 ∈ E1 and m2 ≠ n2, then

which completes the proof. □

Definition 3.35. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Definition 3.36. Let G1 = (M1, N1) and G2 = (M2, N2) be two vague graphs. For any vertex (m1, m2) ∈ V1 × V2 we define

Example 3.37. In this example we find the degree and total degree of the vertex (b, e) in Example 3.33:

Therefore,

The total degree of (b, e) is given by

Therefore,

Similarly, we can find the degree and total degree of all vertices in G1 • G2.

4. Application of Vague Sets to Medical Diagnosis

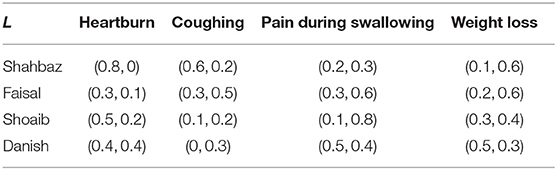

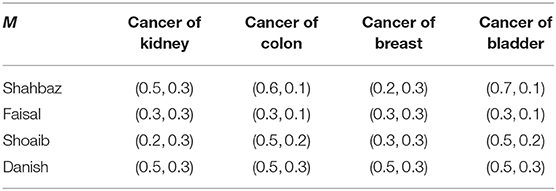

Following the approach outlined by De et al. [18], we will apply vague sets to medical diagnosis by using a max-min-max composition in terms of vague relations. First, we use vague sets to define the disease symptoms. Then, we describe medical knowledge in terms of vague relations. Finally, we determine a diagnosis on the basis of vague relations. Consider four patients named Shahbaz, Shoaib, Faisal, and Danish, and define the set of patients P = {Shahbaz, Shoaib, Faisal, Danish}. Let the set of symptoms under consideration be S = {heartburn, coughing, pain during swallowing, weight loss}. A vague relation L is available from set P to set S, and this is summarized in Table 1.

Cancer is a group of dangerous and prevalent diseases, and represents one of humankind's greatest medical challenges. Many people are diagnosed with late-stage cancer that is difficult or impossible to treat because of a lack of awareness of the disease symptoms. Mathematical models involving vague sets can be used to determine the most likely diagnosis given a set of symptoms that a patient presents with.

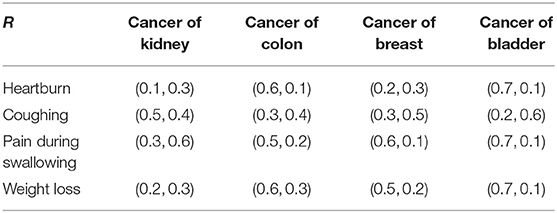

There are many different types of cancers; here we focus on a few of the more life-threatening kinds: (1) kidney cancer, (2) colon cancer, (3) breast cancer, and (4) bladder cancer. We define the set of diagnoses to be D = {cancer of kidney, cancer of colon, cancer of breast, cancer of bladder}. The vague relation R(S → D) from the set of symptoms to the set of diagnoses is given in Table 2. The composition M(P → D) of the vague relations L and R is shown in Table 3; it gives the diagnosis for each patient via the formulas

where pi denotes the patients, dk denotes the different diagnoses, ∧ = min, and ∨ = max.

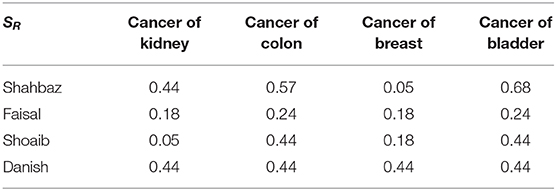

Shown in Table 4 is SR, the best version of diagnosis for this set of patients, which is determined by the formula SR = TR − FRπR. It is very important because the max-min-max rule alone fails to provide exact information.

5. Conclusion

Compared with fuzzy models, vague models offer greater compatibility and flexibility. A vague graph is a type of extension of a fuzzy graph, and is used widely in the field of computer science. We have defined four new operations of a vague graph, called the maximal product, rejection, symmetric difference, and residue product. We have discussed their properties and provided examples on finding the degree of a vertex and the total degree of vertices of graphs that meet specific conditions. We have formulated and proved theorems for these graphs by using the concept of degree of a vertex and total degree of a vertex of a graph. Furthermore, we have presented an application of vague sets to the medical diagnosis of four types of cancer. In future work we will explore further properties relating to vague graphs and bipolar vague graphs.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2019YFA0706402), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2018A0303130115), and the Guangzhou Academician and Expert Workstation (no. 20200115-9).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

2. Rosenfeld A. Fuzzy graphs. In: Zadeh LA, Fu KS, Shimura M, , editors. Fuzzy Sets and Their Application. New York, NY: Academic Press (2006). p. 77–95.

4. Bhattacharya P, Suraweera F. An Algorithm to compute the max-min powers and a property of fuzzy graphs. Pattern Recogn Lett. (1991) 12:413–20.

6. Nagoor Gani A, Basheer Ahamed M. Order and size in fuzzy graphs. Bull Pure Appl Sci. (2003) 22:145–8.

9. Borzooei RA, Rashmanlou H. New concepts of vague graphs. Int J Mach Learn Cybernet. (2015) 8:1081–92. doi: 10.1007/s13042-015-0475-x

10. Rashmanlou H, Borzooei RA. Product vague graphs and its applications. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. (2016) 30:371–82. doi: 10.3233/IFS-151762

11. Boorzooei RA, Rashmanlou H, Samanta S, Pal M. Regularity of vague graphs. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. (2016) 30:3681–9. doi: 10.3233/IFS-162114

12. Borzooei RA, Rashmanlou H, Samanta S, Pal M. New concepts of vague competition graphs. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. (2016) 31:69–75. doi: 10.3233/IFS-162121

13. Kumar K, Lavanya S, Broumi S, Rashmanlou H. New concepts of coloring in vague graphs with application. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. (2017) 33:1715–21. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-17489

15. Parvathi R, Karunambigai MG. Intuitionistic fuzzy graphs, computational intelligence, theory and applications. In: International Conference in Germany. Berlin (2006). p. 18–20.

16. Devi M, Ameenal Bibi K, Rashmanlou H. New concepts in intuitionistic fuzzy labeling graphs. Int J Adv Intell Paradigms. (2020).

Keywords: vague set, maximal product, rejection, symmetric difference, residue product, application

Citation: Shao Z, Kosari S, Shoaib M and Rashmanlou H (2020) Certain Concepts of Vague Graphs With Applications to Medical Diagnosis. Front. Phys. 8:357. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.00357

Received: 17 May 2020; Accepted: 27 July 2020;

Published: 11 November 2020.

Edited by:

Muhammad Javaid, University of Management and Technology, PakistanReviewed by:

Anouar Ben Mabrouk, University of Kairouan, TunisiaNdolane Sene, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Senegal

Copyright © 2020 Shao, Kosari, Shoaib and Rashmanlou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saeed Kosari, c2FlZWRrb3NhcmkzOEB5YWhvby5jb20=

Zehui Shao

Zehui Shao Saeed Kosari

Saeed Kosari Muhammad Shoaib

Muhammad Shoaib Hossein Rashmanlou3

Hossein Rashmanlou3