- 1Dental Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is an etiological agent frequently found in both chronic and aggressive periodontitis as well as peri-implantitis. This study assessed the effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT), as an alternative treatment modality, by nano-chitosan encapsulated indocyanine green (CNPs/ICG), as a photosensitizer, on the virulence features of cell-surviving aPDT against A. actinomycetemcomitans. The cell cytotoxicity effect of CNPs/ICG was evaluated on primary human gingival fibroblast cells. A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 33384 photosensitized with CNPs/ICG was irradiated with diode laser at a wavelength of 810 nm for 1 min (31.2 J/cm2), and then bacterial viability measurements were done. The biofilm formation ability, metabolic activity, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were assessed for cell-surviving aPDT. The effect of aPDT on the expression of the fieF virulent gene, encoding the ferrous-iron efflux pump, was evaluated by the quantitative real-time PCR. CNPs/ICG-aPDT resulted in a significant reduction of cell viability (91%), biofilm formation capacity (53%), and metabolic activity (48%) of A. actinomycetemcomitans when compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Moreover, fieF gene expression was downregulated by 14.8 folds after the strains were treated with aPDT. The virulence of A. actinomycetemcomitans strain reduced in cells surviving aPDT with CNPs/ICG, indicating the potential implications of aPDT for the treatment of A. actinomycetemcomitans infections in periodontitis and peri-implantitis in vivo.

Introduction

The periodontal pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is frequently found in various infections, particularly aggressive periodontitis and peri-implantitis [1]. A. actinomycetemcomitans possesses a numerous virulence factors that reinforce its survival in the oral cavity and are associated with colonization, biofilm formation, and invasion of the host tissue [2].

Previous studies have shown that complete eradication of microorganisms, as the main purpose of periodontal therapy, is not achieved with conventional therapies [3–5]. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) is currently used as a potential alternative strategy for considerably removal of microorganisms from the oral cavity [4].

aPDT includes light, a photosensitizer, and oxygen [5]. Various types of photosensitizers have been recently developed, among which indocyanine green (ICG) as an anionic photosensitizer has a higher in vitro efficacy against oral microorganisms [6]. Despite ICG potential therapeutic effects, the major disadvantage of ICG in aPDT is limited due to its instability in aqueous solutions that has been overcome by encapsulation of ICG molecules in nano-sized carriers [7].

A review of the literature suggests that chitosan has desirable features for ideal delivery of photosensitizers during aPDT compared to other polymers. Chitosan is a cationic aminopolysaccharide and water-soluble polymer that is both biodegradable and biocompatible, and is widely used in various pharmaceutical formulations [8]. Formulation of nanocarriers not only protects the active moiety against degradation agents and environmental factors, but also effectively delivers it to the specific action site and reduces the drug clearance time [9].

Previous papers have assessed the application of chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) as drug carriers for cancer therapy [10–12]; however, to the best of our knowledge, no study has attempted to characterize the effects of a combination of CNPs with a photosensitizer as a new therapeutic method on photodynamic treatment of A. actinomycetemcomitans as an etiological agent in periodontitis and peri-implantitis.

This study hypothesized that encapsulation of ICG into CNPs may significantly enhance aPDT. Therefore, in this study, a nanocarrier was developed by conjugating ICG to a natural polymer, low molecular- weight chitosan to monitor the metabolic activity of A. actinomycetemcomitans cells surviving aPDT using CNPs/ICG. Since the potential advantage of aPDT is the choice of a suitable target site for the photosensitizer to selectively kill the targeted bacteria without adversely affecting the surrounding tissues, a number of bioinformatic tools and biological databases was used for molecular modeling prediction and structure validation of FieF, encoding the ferrous-iron efflux pump, as one of the important virulence factors in A. actinomycetemcomitans and a target for CNPs/ICG.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of CNPs/ICG

In the present study, CNPs were synthesized using he ionotropic gelation method as per the procedure reported by Masarudin et al. [13]. Briefly, 50 mg of chitosan powder purchased from ACROS Organic (UK) with a low molecular weight (1–3 kDa) was dissolved in 50 mL deionized distilled water. Then, 1% acetic acid solution was added dropwise under magnetic stirring to create a homogeneous chitosan solution.

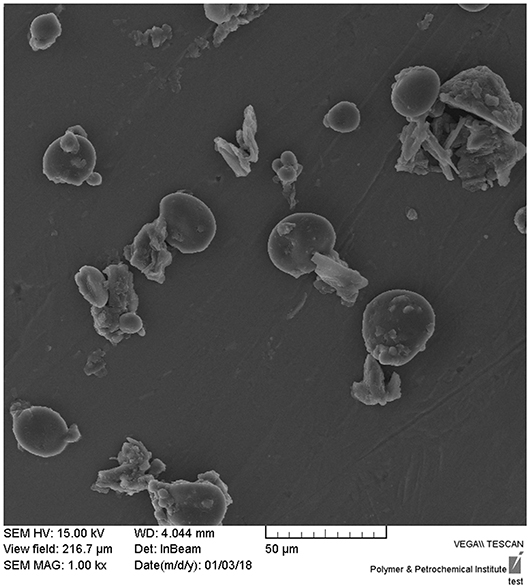

Afterwards, ICG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Co., Ltd; Shanghai, China) at a final concentration of 2.0 mg/mL was added to the above prepared chitosan solution and mixed at 1,000 rpm using a magnetic mixer and mixed at 1,000 rpm using a magnetic mixer for 10 min at pH 4.8. Sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP; [0.5% (w/v), 2 mL]) was then added dropwise and the mixture was stirred well for about 30 min. This compound was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (Eppendorf, Germany) for 30 min three times. The collected sediment CNPs/ICG was lyophilized and used for further experiments. Morphological analysis of CNPs/ICG was done using A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

Cell Cytotoxicity/Viability Effect of CNPs/ICG

The cytotoxic effect of CNPs/ICG was evaluated according to a previous study [14]. Primary human gingival fibroblast cells (HuGu; IBRC C10459) obtained from the Iranian Biological Resource Center (Tehran, Iran) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, HiMedia Labs, India) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom), L-glutamine (2 mM), 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution (10,000 Unit/mL penicillin, 10 mg/mL streptomycin), and 100 μg/mL amphotericin B, and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The medium was renewed every 72 h.

In the third subculture, a seeding density of 104 cells per well was placed in a flat-bottomed 96-well polystyrene cell culture microplate (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) and then incubated with CNPs/ICG for 24 h. After incubation, the cells were washed with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to remove non-adherent cells and media. Eventually, the cell cytotoxicity/ viability was determined using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom) at 570 nm according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

The A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 33384 strain was cultured at 37°C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions in a culture medium prepared using the brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to which the following compounds were added: 5% defibrinated sheep blood, 5 mg/L hemin, 1 mg/L menadione (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom), and 5 g/L yeast extract (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The strain was then inoculated into tubes containing BHI broth (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to reach a cell density of 1.5 × 108 cells/mL as verified by spectrophotometry (Eppendorf BioPhotometer, Hamburg, Germany) at 600 nm.

Light Source

The required light for aPDT experiments was provided through the DenLase Diode Laser Therapy System (Daheng Group Inc., China) equipped with a wavelength of 810 nm, yeilding an output of 200 mW during one min. The output power was measured by a power meter (Laser Point s.r.l, Milano, Italy).

Evaluation of Effects CNPs/ICG-aPDT on A. Actinomycetemcomitans

The effect of aPDT with CNPs/ICG was investigated on the planktonic and biofilm forms of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The test groups were subjected to:

A. ICG

B. ICG + Diode laser irradiation

C. CNPs/ICG

D. CNPs/ICG + Diode laser irradiation

E. Diode laser

F. Control group: Only bacterial suspension

Microbial Viability Assay

The antimicrobial effects of test groups on the planktonic growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans using microbial viability assay were evaluated in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) as described previously [15].

In groups A and C, 100 μL of 1,000 μg/mL ICG (Santa Cruz, USA) and 100 μL CNPs/ICG were separately added into wells of a 96-well round-bottomed sterile polystyrene microplate (TPP; Trasadingen, Switzerland) filled with 100 μL A. actinomycetemcomitans suspension at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL. The microplate was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 5 min in a microaerophilic atmosphere.

In groups B and D, the microplate wells were filled with ICG and CNPs/ICG similar to groups A and C, and were then exposed to diode laser irradiation at a wavelength of 810 nm and energy density of 31.2 J/cm2 for 1 min. The distance between the optical fiber and microplate surface was <1 mm.

In group E, the microplate wells were filled with 100 μL of the A. actinomycetemcomitans suspension at a concentration of 1.5 × 105 CFU/mL and then exposed to diode laser irradiation alone at a wavelength of 810 nm and an energy density of 31.2 J/cm2.

In group F, the microplate wells containing bacterial suspension at a concentration of 1.5 × 105 CFU/mL were used as the control group without ICG, CNPs/ICG, and diode laser irradiation.

Next, 10 μL of the content of each well was cultured in an enriched BHI agar plate whose components were described above. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions and the CFUs/mL was determined based on a method proposed by Miles and Misra [16].

Assessment of Biofilm Formation Ability of A. Actinomycetemcomitans

The anti-biofilm effects of the test groups were evaluated via the crystal violet assay according to a previous study [17]. As described in the previous section (Evaluation of effects CNPs/ICG-aPDT on A. actinomycetemcomitans), the bacterial suspension was transferred to microplate wells and received different treatments (A-F). After treatment, the microplate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h under microaerophilic conditions for biofilms to form. After this time, the content of the microplate wells was discarded and the wells were washed with PBS and air dried for 15 min. then, 100 μL of 95% ethanol was added to each well to fix the bacterial cells prior to staining. The content of the microplate was then emptied and 200 μL of 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet and added to each well. After 20 min, the wells were washed with PBS and filled with 150 μL of 33% acetic acid. The absorbance quantification of the solutions was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). In addition, a SEM was used to confirm the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans biofilms in each treated group.

Assessment of Metabolic Activity of Biofilm Formed by A. Actinomycetemcomitans

The metabolic activity of the biofilm formed by A. actinomycetemcomitans following treatment was determined by the XTT reduction assay. Briefly, the XTT (2,3-bis [2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide; Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom) solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared in PBS in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions prior to use. Then, 100 μL of the A. actinomycetemcomitans suspension at a concentration of 5 × 103 CFU/mL was seed into wells of a 96-well flat-bottomed sterile polystyrene microplate (TPP; Trasadingen, Switzerland). The microplate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h under microaerophilic conditions. Following each treatment explained in section Evaluation of Effects CNPs/ICG-aPDT on A. actinomycetemcomitans. (A-F), 50 μL of the XTT solution was added to each well. The microplate was then incubated in the dark at 37°C for 3 h. The wells containing 100 μL of the medium alone were used as the blank absorbance readings. Following incubation, the color intensity was determined by a microplate reader at 492 nm.

Selecting Target Site in A. Actinomycetemcomitans for aPDT

Based on the results of previous studies [18, 19], in silico approaches enhance our knowledge of the target site for increasing the efficiency of aPDT. In the current study, a number of bioinformatic tools and biological databases were used to predict the physicochemical properties, molecular modeling, and structure validation of the ferrous-iron efflux pump (FieF) as one of the target sites for CNPs/ICG mediated aPDT.

Retrieval and Molecular Modeling of FieF

The amino acid sequences of FieF from A. actinomycetemcomitans (GenBank: KYK95409) were retrieved from the National Center for Biological Information (NCBI; available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Alignment with the Protein-Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) was conducted in Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries to find an appropriate template.

Physicochemical Properties Prediction and Functional Characterization of FieF

Physicochemical properties of the FieF were determined using the UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org) and Expasy ProtParam server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam). The three-dimensional structure of the FieF was obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/VAST, and the phi-psi torsion angles for all residues in the FieF structure were determined using the Ramachandran plot (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/). In addition, a protein calculator (http://protcalc.sourceforge.net/) was used to compute the appropriate photosensitizer according to the FieF pH.

Analysis of the Virulence Associated Gene Expression Following Different Treatments by Relative Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

After treatment of the A. actinomycetemcomitans strain with test groups (A-F), the total RNA was directly extracted using the GeneAll Hybrid-R™ RNA purification kit (Geneall Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Residual genomic DNA contaminating RNA samples was removed using RNase-free DNase I treatment (Thermo Scientific GmbH, Germany) and complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were then synthesized through a Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers that were designed using the Primer3 software version 4.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/) were fieF-F, 5′-GTATAGCGCGCAGGTGAAAA-3′; fieF-R, 5′-GCTATGGTTATGATCCGCCG-3′; 16S Rrna-F, 5′- AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG−3′; 16S Rrna-R, 5′- AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA−3′. Finally, the qRT-PCR analysis was performed on a Line-GeneK Real-Time PCR system and the expression level of the target gene was analyzed using the method proposed by Livak and Schmittgen [20].

Data Evaluation and Statistical Analysis

The results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and P-values < 0.05 were considered significantly different. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Post Hoc Bonferroni tests were used for comparison between the test groups and the control group as well as the intergroup comparison.

Results

Successful synthesis of CNPs/ICG was confirmed via the SEM. As shown in Figure 1, the CNP was a nano-sized particle around 60–100 nm in diameter with a uniform shape.

Determination of Cell Cytotoxicity/Viability

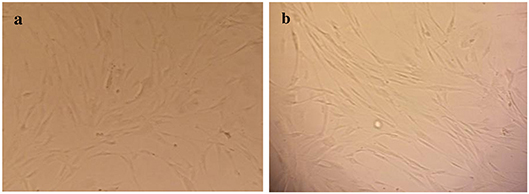

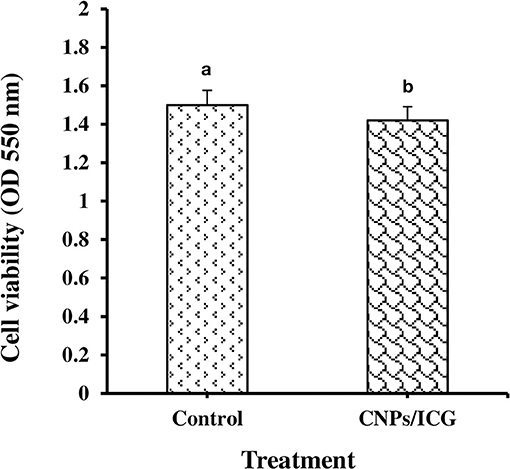

As shown in Figure 1, HuGu cells showed spindle-shaped morphological phenotypes and adhered to the surface of the culture microplate before treatment with CNPs/ICG (Figure 2a). When HuGu cells were subjected to CNPs/ICG, no changes were seen in the cell morphology (Figure 2b). In addition, there was no significant different in cell survival following exposure to CNPs/ICG compared to the control group (P > 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 2. Inverted micrograph of HuGu cells (original magnification, 40×; scale bar, 10 μm); (a) Showing a spindle-shaped cell, (b) HuGu cells treated with CNPs/ICG.

Figure 3. Determination of HuGu cell viability by MTT assay; (a) Non-treated HuGu cells, (b) HuGu cells treated with CNPs/ICG.

Different Treatments on A. Actinomycetemcomitans

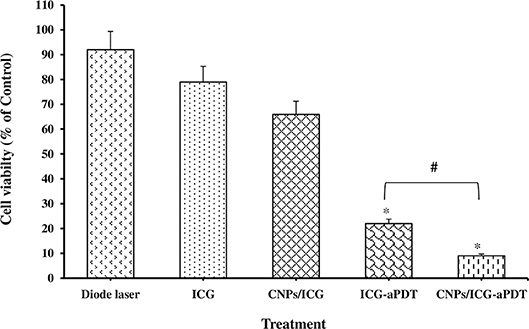

The effect of different treatments on the planktonic growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans is presented in Figure 4. The highest reduction in the bacterial viability of A. actinomycetemcomitans was seen after CNPs/ICG-aPDT (91%) and ICG-aPDT (78%) (both P < 0.05). In addition, there was a significant difference in the A. actinomycetemcomitans growth reduction between CNPs/ICG-aPDT and ICG-aPDT. Figure 4 shows that the bacterial growth reduction in the presence of diode laser (%), ICG (%), and CNPs/ICG (%) was not significant in comparison to the control group (untreated bacteria; P > 0.05). According to Figure 4, the reduction in the planktonic growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans after treatment with CNPs/ICG-aPDT and ICG-aPDT was significantly higher than treatment with diode laser, ICG, and CNPs/ICG (P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Percent of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans viability after exposed with test groups. Results are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between ICG-aPDT and CNPs/ICG-aPDT.

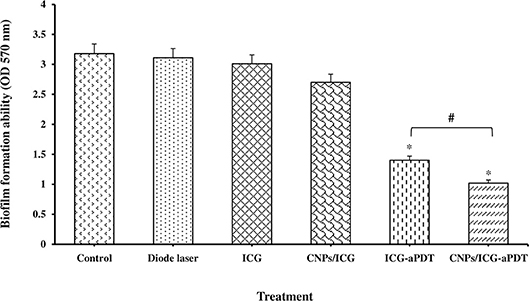

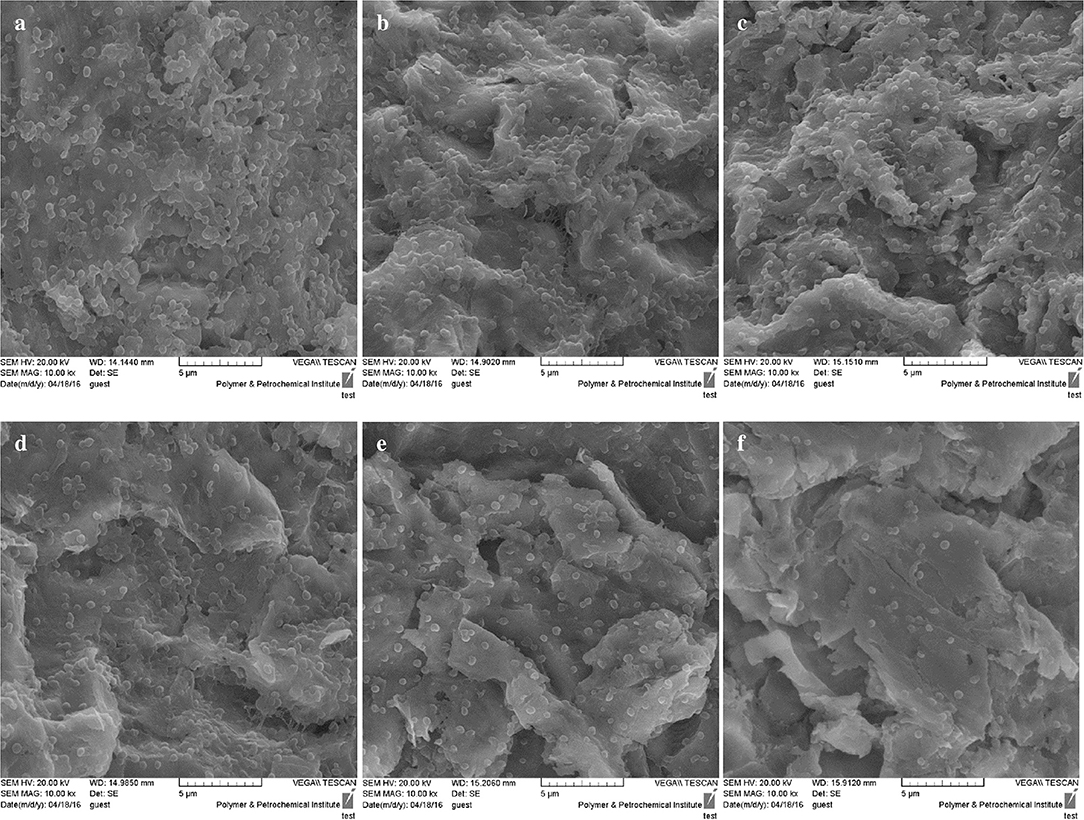

Figure 5 reveals that A. actinomycetemcomitans biofilm formation decreased significantly in the aPDT treated groups including ICG and CNPs/ICG significantly by up to 34% and 53%, respectively, compared to the control group (P < 0.05). In addition, a marked difference was seen between the inhibition of biofilm formation effect of ICG-aPDT and CNPs/ICG-aPDT (P < 0.05; Figure 5). Moreover, it was observed that biofilm formation ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans did not significantly decrease when the bacterial cells were treated with diode laser, ICG and CNPs/ICG alone (P > 0.05; Figure 5). The data in Figure 5 also indicate a significant reduction in the biofilm formation of A. actinomycetemcomitans after treatment with CNPs/ICG-aPDT and ICG-aPDT compared to treatment with diode laser, ICG, and CNPs/ICG (P < 0.05). Based on the results of SEM images, CNPs/ICG mediated aPDT inhibited the biofilm formation of A. actinomycetemcomitans more than other groups (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Biofilm formation ability of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans after exposed with test groups. Results are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between ICG-aPDT and CNPs/ICG-aPDT.

Figure 6. SEM images of biofilm formation ability of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans after exposed with test groups. (a) Control; (b) Diode laser; (c) ICG; (d) CNPs/ICG; (e) ICG-aPDT; (f) CNPs/ICG-aPDT.

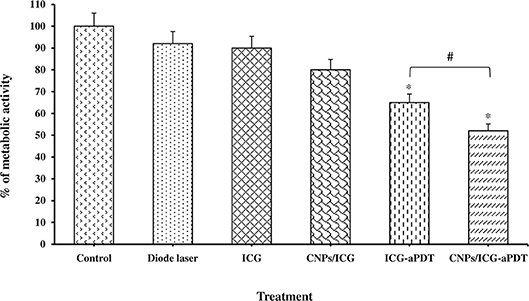

According to our results, a statistically significant difference was observed in the reduction of the metabolic activity of the biofilm formed by A. actinomycetemcomitans following treatment with CNPs/ICG-aPDT (48%) and ICG-aPDT (35%) compared to the control group (P < 0.05; Figure 7). It should also be noted that the metabolic activity of the biofilm formed by A. actinomycetemcomitans was less susceptible to treatment with diode laser, ICG, and CNPs/ICG alone with 8, 10, and 20% reduction in the metabolic activity following above treatments, respectively (all P > 0.05; Figure 7). Overall, as shown in Figure 7, the reduction in the metabolic activity of the biofilm formed by A. actinomycetemcomitans following treatment with CNPs/ICG-aPDT and ICG-aPDT was markedly different from treatment with diode laser, ICG, and CNPs/ICG alone (P > 0.05).

Figure 7. Biofilm formation ability of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans after exposed with test groups. Results are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between ICG-aPDT and NCPs/ICG-aPDT.

Selection and Expression of Virulence Genes

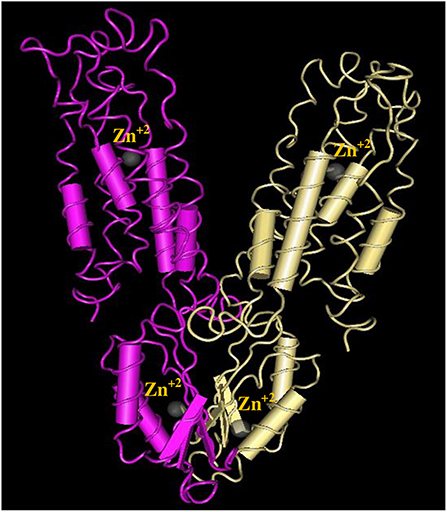

According to the NCBI GenBank, FieF has 306 amino acids. Using BLAST, similarity search against FieF identified in the structure of the zinc transporter YiiP displayed that it was similar to the protein structure with accession number of 2QFI. The total score of protein alignment between FieF and 2QFI was 277, with 96 and 48% query cover and identity, respectively.

FieF has a molecular weight of 33879.83 Da and an estimated theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of 6.40. The extension coefficient of the protein is 18,450, indicating how much light is absorbs by the protein at a definite wavelength, and its instability index (II) is 43.90. In addition, the estimated charge of FieF at pH 7.00 was −1.6 using a protein calculator.

The basic information of the initial structure showed that FieF had 23 positively charged (Arg + Lys) and 26 negatively charged residues (Asp + Glu). The amino acid composition of FieF is Ala (A) 11.8%, Arg (R) 4.6%, Asn (N) 2.0%, Asp (D) 4.9%, Cys (C) 0.0%, Gln (Q) 5.6%, Glu (E) 3.6%, Gly (G) 3.6%, His (H) 3.6%, Ile (I) 9.8%, Leu (L) 16.0%, Lys (K) 2.9%, Met (M) 3.3%, Phe (F) 4.9%, Pro (P) 2.6%, Ser (S) 7.8%, Thr (T) 5.2%, Trp (W) 0.7%, Tyr (Y) 1.6%, Val (V) 5.6%, Pyl (O) 0.0%, and Sec (U) 0.0%.

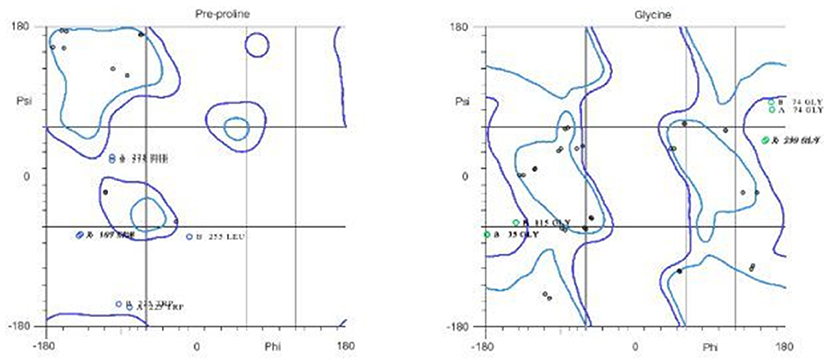

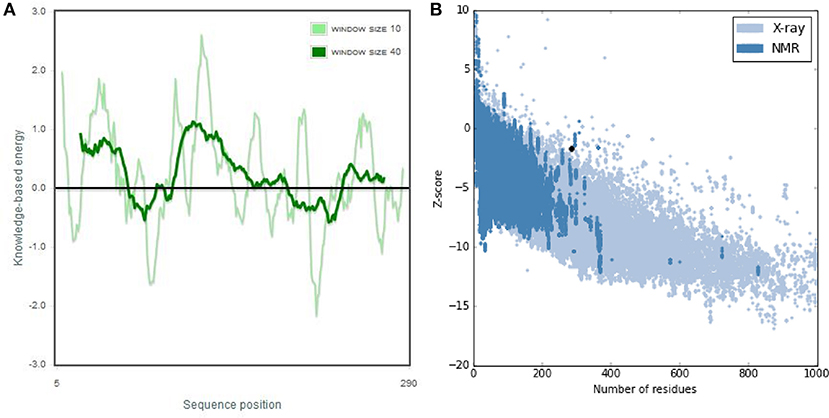

The 3D structure of FieF with 4 Zinc+2 ions is shown in Figure 8. According to the Ramachandran Plot analyses in Figure 9, 49.6% of all residues were in the favored regions and 29.6% of all residues were in allowed regions. Moreover, 20.8% of the residues were in the outlier region. According to Figure 10, the results of the ProSA-web indicated that the modeled structure of FieF in A. actinomycetemcomitans was reasonable and reliable as a therapeutic target for aPDT. Based on the basic information obtained from in silico analysis, the fieF gene in A. actinomycetemcomitans was considered a target site for CNPs/ICG-aPDT.

Figure 8. Three-dimensional structures of Fief with 4 Zinc+2 ions obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/VAST.

Figure 9. Residues in favored and allowed regions in the Ramachandran plot of Fief obtained from http://www.ebi.ac.uk/.

Figure 10. ProSA-web output of Fief shows the local model quality by plotting energies profile of amino acid and bindicating the Z score (or standard score) on a plot based on the entire protein chain in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) determined by X-ray crystallography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy; (A) Overall model quality, (B) Local model quality.

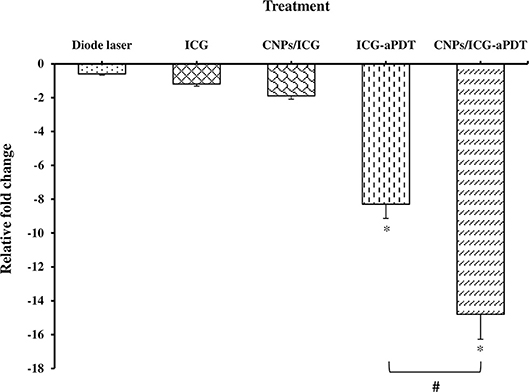

The qRT-PCR analysis showed that aPDT treatment with ICG and CNPs/ICG markedly reduced the expression level of A. actinomycetemcomitans fieF gene by −8.3 and −14.8 folds, respectively (P < 0.05; Figure 11). Moreover, there was a statistically significant reduction in the fieF gene expression following CNPs/ICG-aPDT compared to ICG-aPDT (P < 0.05). On the other hand, according to Figure 11, there was no significant fold decrease in fieF gene expression following treatment with diode laser (−0.6 fold), ICG (−1.2 fold), and CNPs/ICG (−1.9 fold) alone compared to the control group (P > 0.05). Following treatment with ICG- and CNPs/ICG-aPDT, the expression of fieF decreased significantly compared to treatment with diode laser, ICG, and CNPs/ICG alone (P > 0.05; Figure 11).

Figure 11. Effects of test groups on the virulence genes expression of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between ICG-aPDT and CNPs/ICG-aPDT.

Discussion

The present study focused on the application of the developed CNPs/ICG in photo-elimination of A. actinomycetemcomitans as a major periodontal pathogen. The current in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of CNPs/ICG showed no toxicity profile toward HuGu cells. The cytotoxicity of aPDT depends on the type and concentration of the PS, energy density of irradiation, and type of cells [21]. Generally, our findings regarding cytotoxicity against HuGu cells are consistent with the results of a recent study that showed ICG does not have toxic effects on HuGu cells at a concentration of 500–2,000 mg/mL. Similarly, Huang et al also reported chitosan nanoparticles have no cytotoxic effects at concentrations up to 0.741 mg/ml. [22] CNPs/ICG can be easily taken by bacterial cells due to the positive charge on their surface which interacts with the bacteria plasma membrane during aPDT. Our results showed that ICG, CNPs/ICG, and diode laser irradiation alone could not significantly prevent the planktonic growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans. However, simultaneous use of diode laser with ICG and CNPs/ICG was found to have the highest potency in inhibiting A. actinomycetemcomitans by 34 and 53%, respectively. Our findings are line with the results of other studies reporting improved antimicrobial effects of ICG based photodynamic properties through conjugation of ICG to nano-graphene oxide and polymer poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) [23, 24]. There are currently no fundamental detailed reports of the effects of using an additional nanocarrier in aPDT. It is therefore hypothesized that the enhancing effect is probably due to the reduced anionic surface charge of ICG in the CNPs/ICG structure. Since CNPs/ICG can attach to and penetrate the microbial cell envelope quite easily, it may cause a stronger microbial damage compared to treatment with ICG alone.

Similar results were also observed when the effect of CNPs/ICG-aPDT was examined on the bacterial biofilm formation ability and metabolic activity of A. actinomycetemcomitans cells.

CNPs/ICG mediated aPDT represented the highest levels of biofilm formation inhibition and reduction of metabolic activity in comparison with other groups (P < 0.05). Based on these results, the advantage of using CNPs as a biodegradable therapeutic carrier is that CNPs interact with and disrupt the microbial biofilm. This observation is in agreement with the earlier data indicating that chitosan coupling makes microbial biofilms susceptible to antibiotics due to its role in the disruption of the biofilm architecture. As a biomaterial, chitosan exhibits anti-biofilm effects and the ability of chitosan to damage biofilms formed by microorganisms has been documented. Chitosan has been shown to penetrate microbial biofilms due to its cationic charge, which results in disruption of the negatively charged cell membrane as microorganisms settle on the surface [25]. Chávez de Paz et al. demonstrated that chitosan nanoparticles were distributed in the biofilm structure, leading to the access of antimicrobial agents to microbial cells [26].

Since it is important to apply aPDT to sensitize and suppress the targeted gene in the microorganism selectively [18, 19], a number of bioinformatic tools and computer simulation molecular modeling were used to predict the hierarchical nature of the structure, physicochemical properties, and functional characteristics of FieF as one of the target sites for aPDT. FieF as an iron-efflux transporter is responsible for iron detoxification needed for the cell growth survival and biofilm formation [27]. According to the constituent elements of FieF as seen in Figure 7, FieF has four Zn2+ ions that are able to transport Zn2+ in a proton-dependent manner. The regulation of the fieF gene expression has not been well defined, but it does appear to be regulated by FieF [28]. As revealed by the results of this study, CNPs/ICG-aPDT treatment significantly downregulated the expression of the fieF gene 6.5 and 14.8 times more than ICG-aPDT and control group, respectively. Therefore, CNPs/ICG-aPDT and ICG-aPDT biofilm inhibitory effects might be partially contributed to interference with the A. actinomycetemcomitans fieF gene expression. Downregulation of the fieF gene in aPDT-treated A. actinomycetemcomitans strains may also result in attenuation of iron-efflux regulated virulence activities such as biofilm formation.

Thus, CNPs/ICG-aPDT described in this paper may demonstrate a versatile method to control the growth and virulence of oral pathogens responsible for various oral diseases. Nevertheless, it seems that in vivo examinations are necessary to establish an aPDT protocol and their findings can represent important progress in periodontitis and peri-implantitis therapy. Thereby, more advanced level of investigations is needed to ensure pharmaceutical efficacy of CNPs/ICG mediated aPDT.

Conclusion

This study revealed encapsulation of ICG into chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs/ICG) did not have cytotoxic effect on the HuGu cells while it enhanced its antimicrobial, anti-biofilm, and anti-virulence properties. CNPs/ICG-aPDT can decrease the virulence of A. actinomycetemcomitans by reduction of its growth rate, fieF gene expression and biofilm formation, which may result in deceleration of the process of disease progression.

Author Contributions

AB and MP proposed the original idea. All authors developed the protocol and abstracted and analyzed the data. MP wrote the manuscript and performed the additional experiments. AB edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences & Health Services grant No 96-01-30-34552.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Cortelli SC, Cortelli JR, Romeiro RL, Costa FO, Aquino DR, Orzechowski PR, et al. Frequency of periodontal pathogens in equivalent peri-implant and periodontal clinical statuses. Arch Oral Biol. (2013) 58:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.09.004

2. Benso B. Virulence factors associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans and their role in promoting periodontal diseases Virulence (2017) 8:111–4. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1235128

3. Pourhajibagher M, Monzavi A, Chiniforush N, Monzavi MM, Sobhani S, Shahabi S, et al. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of expression stability of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans fimbria-associated gene in response to photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. (2017) 18:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.02.009

4. Pulikkotil SJ, Toh CG, Mohandas K, Leong K. Effect of photodynamic therapy adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients: a randomized clinical trial. Aust Dent J. (2016) 61:440–5. doi: 10.1111/adj.12409

5. Pourhajibagher M, Chiniforush N, Shahabi S, Sobhani S, Monzavi MM, Monzavi A, et al. Monitoring gene expression of rcpA from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans versus antimicrobial photodynamic therapy by relative quantitative real-time PCR. Photodiagnosis. Photodyn Ther. (2017) 19:51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.04.011

6. Sasaki Y, Hayashi JI, Fujimura T, Iwamura Y, Yamamoto G, Nishida E, et al. New irradiation method with indocyanine green-loaded nanospheres for inactivating periodontal pathogens. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:e154. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010154

7. Chen J, Liu C, Zeng G, You Y, Wang H, Gong X, et al. Indocyanine green loaded reduced graphene oxide for in vivo photoacoustic/fluorescence dual-modality tumor imaging. Nanoscale Res Lett. (2016) 11:85. doi: 10.1186/s11671-016-1288-x

8. Naqvi S, Mohiyuddin S, Gopinath P. Niclosamide loaded biodegradable chitosan nanocargoes: an in vitro study for potential application in cancer therapy. R Soc Open Sci. (2017) 4:170611. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170611

9. Wu QX, Lin DQ, Yao SJ. Design of chitosan and its water soluble derivatives-based drug carriers with polyelectrolyte complexes. Mar Drugs (2014) 12:6236–53. doi: 10.3390/md12126236

10. Bhunchu S, Rojsitthisak P. Biopolymeric alginate-chitosan nanoparticles as drug delivery carriers for cancer therapy. Pharmazie (2014) 69:563–70. doi: 10.1691/ph.2014.3165

11. Ding YF, Li S, Liang L, Huang Q, Yuwen L, Yang W, et al. Highly biocompatible chlorin e6-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for improved photodynamic cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces (2018) 10:9980–7. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b01522

12. Wang C, Zhang Z, Chen B, Gu L, Li Y, Yu S. Design and evaluation of galactosylated chitosan/graphene oxide nanoparticles as a drug delivery system. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2018) 516:332–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.01.073

13. Masarudin MJ, Cutts SM, Evison BJ, Phillips DR, Pigram PJ. Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: application to the passive encapsulation of [14C]-doxorubicin. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. (2015) 8:67–80. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S91785

14. Arancibia R, Maturana C, Silva D, Tobar N, Tapia C, Salazar JC, et al. Effects of chitosan particles in periodontal pathogens and gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res. (2013) 92:740–5. doi: 10.1177/0022034513494816

15. Pourhajibagher M, Chiniforush N, Shahabi S, Ghorbanzadeh R, Bahador A. Sublethal doses of photodynamic therapy affect biofilm formation ability and metabolic activity of Enterococcus faecalis. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. (2016) 15:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.06.003

16. Miles AA, Misra SS. The estimation of bactericidal power of the blood. J Hyg. (1938) 38:732. doi: 10.1017/S002217240001158X

17. Pourhajibagher M, Chiniforush N, Ghorbanzadeh R, Bahador A. Photo-activated disinfection based on indocyanine green against cell viability and biofilm formation of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. (2016) 16:30180–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.10.003

18. Pourhajibagher M, Bahador A. In silico identification of a therapeutic target for photo-activated disinfection with indocyanine green: modeling and virtual screening analysis of Arg-gingipain from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. (2017) 18:149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.02.015

19. Pourhajibagher M, Bahador A. Evaluation of the crystal structure of a fimbrillin (FimA) from Porphyromonas gingivalis as a therapeutic target for photo-activated disinfection with toluidine blue O. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. (2017) 17:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.11.007

20. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (2001) 25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

21. Carrera ET, Dias HB, Corbi SCT, Marcantonio RAC, Bernardi ACA, Bagnato VS, et al. The application of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) in dentistry: a critical review. Laser Phys. (2016) 26:123001. doi: 10.1088/1054-660X/26/12/123001

22. Huang M, Khor E, Lim LY. Uptake and cytotoxicity of chitosan molecules and nanoparticles: effects of molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Pharm Res. (2004) 21:344–53. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000016249.52831.a5

23. Hu D, Zhang J, Gao G, Sheng Z, Cui H, Cai L. Indocyanine green-loaded polydopamine reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites with amplifying photoacoustic and photothermal effects for cancer theranostics. Theranostics (2016). 6:1043–52. doi: 10.7150/thno.14566

24. Sah E, Sah H. Recent trends in preparation of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles by mixing polymeric organic solution with antisolvent. J Nanomater. (2015) 2:1–22. doi: 10.1155/2015/794601

25. Piras AM, Maisetta G, Sandreschi S, Gazzarri M, Bartoli C, Grassi L. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with the antimicrobial peptide temporin B exert a long-term antibacterial activity in vitro against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Front Microbiol. (2015) 6:372. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00372

26. Chávez de Paz LE, Resin A, Howard KA, Sutherland DS, Wejse PL. Antimicrobial effect of chitosan nanoparticles on streptococcus mutans biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2011) 77:3892–5. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02941-10

27. Pi H, Helmann JD. Ferrous iron efflux systems in bacteria. Metallomics (2017) 9:840–51. doi: 10.1039/C7MT00112F

Keywords: nano-chitosan, indocyanine green, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, periodontitis, peri-implantitis

Citation: Pourhajibagher M, Rokn AR, Rostami-Rad M, Barikani HR and Bahador A (2018) Monitoring of Virulence Factors and Metabolic Activity in Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans Cells Surviving Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy via Nano-Chitosan Encapsulated Indocyanine Green. Front. Phys. 6:124. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2018.00124

Received: 30 June 2018; Accepted: 15 October 2018;

Published: 06 November 2018.

Edited by:

Hui Liu, Syneron-Candela, United StatesReviewed by:

Junming Ren, City of Hope National Medical Center, United StatesFei Geng, McMaster University, Canada

Jonathan P. Celli, University of Massachusetts Boston, United States

Copyright © 2018 Pourhajibagher, Rokn, Rostami-Rad, Barikani and Bahador. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abbas Bahador, YWJhaGFkb3JAc2luYS50dW1zLmFjLmly

Maryam Pourhajibagher1

Maryam Pourhajibagher1 Mehdi Rostami-Rad

Mehdi Rostami-Rad Abbas Bahador

Abbas Bahador