- 1Consortium for Fundamental Physics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

- 2Consortium for Fundamental Physics, Physics Department, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

- 3Department of Astronomy, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

We describe the evolution of Dark Matter (DM) abundance from the very onset of its creation from inflaton decay under the assumption of an instantaneous reheating. Based on the initial conditions such as the inflaton mass and its decay branching ratio to the DM species, the reheating temperature, and the mass and interaction rate of the DM with the thermal bath, the DM particles can either thermalize (fully/partially) with the primordial bath or remain non-thermal throughout their evolution history. In the thermal case, the final abundance is set by the standard freeze-out mechanism for large annihilation rates, irrespective of the initial conditions. For smaller annihilation rates, it can be set by the freeze-in mechanism which also does not depend on the initial abundance, provided it is small to begin with. For even smaller interaction rates, the DM decouples while being non-thermal, and the relic abundance will be essentially set by the initial conditions. We put model-independent constraints on the DM mass and annihilation rate from over-abundance by exactly solving the relevant Boltzmann equations, and identify the thermal freeze-out, freeze-in and non-thermal regions of the allowed parameter space. We highlight a generic fact that inflaton decay to DM inevitably leads to an overclosure of the Universe for a large range of DM parameter space, and thus poses a stringent constraint that must be taken into account while constructing models of DM. For the thermal DM region, we also show the complementary constraints from indirect DM search experiments, Big Bang Nucleosynthesis, Cosmic Microwave Background, Planck measurements, and theoretical limits due to the unitarity of S-matrix. For the non-thermal DM scenario, we show the allowed parameter space in terms of the inflaton and DM masses for a given reheating temperature, and compute the comoving free-streaming length to identify the hot, warm and cold DM regimes.

1. Introduction

There is overwhelming astrophysical and cosmological evidence for the existence of Dark Matter (DM) in our Universe (for a review, see 1). Assuming the standard ΛCDM (cosmological constant+Cold Dark Matter) picture of the Universe, the recent measurements from the Planck mission yield the current matter density in the Universe to be 4.9% in the form of baryonic matter and 26.6% as non-baryonic, non-luminous DM, while the remaining 68.5% is in the form of Dark Energy [2]. Despite all the compelling evidence from its gravitational interaction, the origin and nature of DM are still unknown, and resolving these issues is one of the main goals of modern cosmology as well as particle physics.

On the other hand, cosmological observations such as Planck [3] are strongly pointing toward an epoch of primordial inflation (for a review, see [4]), which is considered to be one of the best paradigms to create the seed perturbations for the DM particles to form the observed large-scale structures [5]. Inflation not only stretches the primordial perturbations on large scales but also dilutes all matter, and therefore, it is important that the inflaton must excite the Standard Model (SM) degrees of freedom (d.o.f) after the end of inflation for the success of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) [6].

Irrespective of the origin of the inflaton field, whose potential leads to inflation, the inflaton could decay into the SM d.o.f, and also directly to the DM particles. The process of creating the entropy happens after the end of inflation during reheating or preheating (for reviews, see 4, 7). If the inflaton is a SM gauge-singlet field ϕ, it can in principle couple and decay to DM particles χ with some unknown branching ratio1. As a concrete example, one can envisage a visible-sector inflation scenario within the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM), where inflation can be driven by the superpartners of quarks and leptons [9–11]. Thus, if the DM can have a significant coupling to the inflaton or the moduli field, it can be created rather efficiently from the direct decay of the inflaton or the moduli [12, 13]2. The initial abundance of such DM particles could be large enough to overclose the Universe, unless their interaction rate is sufficiently larger than the Hubble expansion rate in the early Universe, i.e., Γχ » H(t), to make them annihilate efficiently into the SM d.o.f. The requirement of not to overproduce the DM poses a stringent constraint on its mass and interaction rates. In fact, a small branching fraction of the inflaton energy density to DM particles can be sufficient to overclose the Universe [18].

In this paper, we seek a model-independent way to analyze the thermal and non-thermal properties of the DM directly produced from the inflaton decay, in terms of their masses, the initial inflaton branching ratio and the strength of DM coupling to the thermal bath. For this purpose, we will make the following minimal assumptions:

1. The inflaton decays into the SM d.o.f and the DM in a perturbative scenario; hence on kinematic grounds, mχ < mϕ/2. We do not consider non-perturbative DM production processes during the coherent oscillations of the inflaton, e.g., superheavy DM with mχ » mϕ for large enough amplitude of the inflaton field [8], or fragmentation of the inflaton condensate associated with a global symmetry [19, 20].

2. The process of reheating is instantaneous, and the SM d.o.f produced in the inflaton decay quickly thermalize to achieve a local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE), i.e., both chemical and kinetic equilibrium. Thus we can define a unique reheat temperature TR [21] at which the Universe is dominated by relativistic species. Since we assume the DM to be part of the decay products of the inflaton, its initial number density (nχ) will be determined in terms of the number density of the inflaton field (nϕ) and the branching ratio of the inflaton decay to DM (Bχ) which should be small in order to have the standard radiation-domination epoch immediately after reheating.

We should note here that the analysis presented in this paper based on the simplified picture mentioned above may not be completely valid if the reheating process is not instantaneous and a significant amount of DM is produced during reheating through inelastic scatterings between high energy inflaton decay products and the thermal plasma. However, a proper treatment of this issue must include the details of the thermalization process which involve some model-dependent subtleties. In particular, it is important to know when the inflaton decay products thermalize during the inflaton oscillations. This depends on how the DM interacts with the ambient thermal plasma, such as the SM d.o.f. These thermal interactions lead to some finite temperature effects on DM production rate which will be model-dependent and has to be studied separately. In addition, there exist certain physical situations where the thermalization of the inflaton decay products can happen very late, even beyond the complete decay of the inflaton. This issue has to be dealt again separately, because the DM can still be created before the epoch of thermalization, but instead of thermal corrections, there will be finite momentum effects due to the hard-hard, hard-soft and soft-soft scatterings between the inflaton decay products, all of which must be accounted for in a field-theoretically consistent manner. Besides these issues, there could also be an epoch of preheating during which the DM can be created abundantly, but again this has to be studied in a model-dependent setup. Our main goal in this paper is to study the DM abundance from the inflaton decay in a model-independent perspective, and in this regard, we make the simple assumption that the thermalization has happened instantly right at the time of reheating. A more exhaustive analysis of DM creation from the inflaton decay, addressing all the subtleties mentioned above, will be presented elsewhere.

With the assumptions made above, the evolution of the DM particle number density, can be completely described in a model-independent way by its thermally averaged interaction rate 〈 σ v〉 with the thermal bath. Depending on the size of 〈 σ v〉, we consider the following three possible scenarios:3

1. For large enough 〈 σ v〉, the DM particles will quickly reach LTE with the bath, thus losing their initial abundance, and follow the equilibrium distribution until their reaction rate eventually drops below the Hubble rate, after which they will freeze out as a ‘thermal relic’ with a constant comoving number density. This is the standard WIMP scenario [26] in which the final relic abundance is independent of the initial conditions or the details of the production mechanism. Depending on their mass and interaction rate, they could freeze out as a cold, warm, or hot relic [26]. It is well-known that 〈 σ v〉 ~ 10−26 cm3s−1 naturally gives the observed cold DM relic density [2], almost independent of the DM mass.

2. If the interaction of DM particles with the thermal bath is too small to bring them into full LTE, they will decouple from the bath soon after being produced. Hence, if they are produced abundantly, the final number density will remain large, thus leading to overclosure of the Universe. However, if their initial abundance is negligibly small, the interactions with the bath, although feeble, could still produce some DM particles whose final abundance freezes in at some point as the interaction rate eventually becomes smaller than the expansion rate. This is the FIMP (Feebly Interacting Massive Particle or Frozen-In Massive Particle) scenario [27].

3. For extremely small annihilation rates, the DM particles are never in thermal contact with the bath, and are practically produced decoupled in an out-of-equilibrium condition, and remain non-thermal throughout their evolution. This leads to a super-WIMP (SWIMP)-like scenario [28], where the final abundance is primarily determined by the initial conditions which, in our case, are set by the inflaton mass, reheat temperature and branching ratio [29, 30]4. Note that it is also possible to have a non-thermal DM with chemical equilibrium, provided the reheat temperature is smaller than the usual freeze-out temperature so that the DM decouples during reheating [25]. We do not consider this case here since we have assumed instant reheating.

For each of the above three scenarios, we study the evolution of the DM number density by numerically solving the Boltzmann equation, and obtain their final relic abundance as a function of their mass and interaction rate for cold, warm as well as hot relics. We highlight a generic fact that inflaton decay to DM inevitably leads to an overclosure of the Universe for a large range of parameter space, and provides a generic constraint for models of DM with an arbitrary coupling to the inflaton field. For a given reheat temperature and initial abundance, we show the overclosure region as a function of the DM mass and annihilation rate in a model-independent way. For the thermal WIMP case, we show the complementary constraints on the (mχ,〈 σ v〉) parameter space by taking into account various theoretical as well as experimental limits from unitarity, dark radiation, indirect detection, BBN, Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and Planck. For the non-thermal production of DM from inflaton decay, we show that a large fraction of the (mϕ, mχ) parameter space leads to an overclosure for a generic class of hidden sector models of inflation. This an important result in pinning down the nature of DM from particle physics point of view and on the allowed region of the inflaton-DM coupling and the branching ratio.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In section 2, we briefly review the evolution of DM as governed by the Boltzmann equation. In section 3, we discuss the production of DM from inflaton decay: thermal production (both freeze-out and freeze-in scenarios) in section 3.1, and non-thermal production in section 3.2. In section 4, we discuss various experimental/observational constraints on DM. In section 5, we present our numerical results for both thermal and non-thermal scenarios. Our conclusions are given in section 6.

2. Evolution of DM: A Brief Review

The microscopic evolution of the number density nχ for any species χ, and the departure from its thermal equilibrium value nχ,eq, can be computed exactly by solving the Boltzmann Equation [26]

where 〈 σ v〉 is the thermally averaged total annihilation rate, σ being the total (unpolarized) annihilation cross section, and v being the relativistic relative velocity between the two annihilating particles5. In the absence of Bose-Einstein condensation or Fermi degeneracy, one can neglect the quantum statistical factors, and write the number density as

where gχ is the number of internal (e.g., spin or color) degrees of freedom of χ, T is the temperature, and μχ is the chemical potential of species χ (energy associated with change in particle number) which we assume to be zero for the equilibrium number density nχ,eq. It is useful to express Equation (1) in terms of the dimensionless quantities Yχ = nχ/s and Yχ,eq = nχ,eq/s to scale out the redshift effect due to the expansion of the Universe. Here,

is the entropy density and gs is the effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom contributing to the total entropy density. Recall that in the early Universe with radiation domination, gs is same as the relativistic degrees of freedom gρ contributing to the energy density, and also appearing in the Hubble expansion rate:

where mPl = 1.22 × 1019 GeV is the Planck mass. Henceforth, we will not distinguish the two, and will take gρ = gs ≡ g which is valid for most of the thermal history of the Universe6. Assuming an adiabatic and isentropic (constant entropy per comoving volume) expansion of the Universe, Equation (1) can be rewritten as Srednicki al. [33] and Gondolo and Gelmini [34]

with the introduction of a new independent variable x = mχ/T. The current number density Yχ(x0) of the species χ is obtained by integrating Equation (5) from x = 0 to x = x0 ≡ mχ/T0, where T0 = 2.7255(6) K is the present temperature of the CMB photons [35]. Knowing Yχ(x0), we can compute the relic density of χ, conventionally defined as the ratio of its current mass density, ρχ(x0) = mχ s0 Yχ(x0), and the critical density of the Universe, ρc = 3H02/8π. Using the current values for the entropy density s0 = 2889.2 cm−3(T0/2.725 K)3, and the critical mass density ρc = 1.05375(13) × 10−5 h2 GeVcm−3 [36], we obtain

Equation (5) is a form of the Riccati equation for which there is no general, closed-form analytic solution. Therefore, the current density Yχ(x0) in Equation (6) has to be obtained either by numerically solving Equation (5) or by approximating it with an analytic solution in some special cases. In the standard ΛCDM cosmology, the thermal relics decouple from the thermal plasma in the radiation-dominated era after inflation, and the decoupling occurs at some freeze-out temperature TF when the annihilation rate Γχ = nχ 〈 σ v〉 drops below the Hubble expansion rate H. Depending on the exact value of xF = mχ/TF, one can have the following three scenarios:

2.1. Non-Relativistic Case

For xF ≳ 3, the DM particles are mostly non-relativistic when they decouple from the thermal plasma. This leads to the usual cold DM scenario with free streaming lengths of sub-pc scale [1], as favored by the standard theory of large-scale structure formation [37, 38]. Analytic approximate formulas for their relic abundance have been derived in the non-relativistic limit xF » 1 [34, 39–42]. The key point is that the actual abundance Yχ tracks the equilibrium abundance Yχ,eq during early stages of evolution (for x ≲ x*), while at late stages (x ≳ x*), Yχ,eq is exponentially suppressed and has essentially no effect on the final abundance Yχ(x0). Here x* is some intermediate matching point (not the freeze-out point xF, as commonly assumed) where the deviation from equilibrium starts to grow exponentially. After solving for x* iteratively as a function of mχ, 〈 σ v 〉 and g* (the relativistic degrees of freedom at x = x*), Equation (5) can be integrated from x = x* to x = xF dropping the Yχ,eq term, to finally obtain an improved analytic solution for the relic density (in the s-wave limit) [42]:

where the subscript * means the values evaluated at x = x*, and

The analytic result in Equation (7) agrees with the exact numerical result within ~ 3%, almost independent of the DM mass. Note that for an arbitrary l-wave annihilation, the above formalism can be repeated by Taylor-expanding 〈 σ v〉 in powers of v2r ~ 1/x.

2.2. Relativistic Case

In the other extreme limit, where the freeze-out occurs when the χ particles are still relativistic (xF « 1), their current relic abundance Yχ(x0) is approximated by the equilibrium abundance at freeze-out Yχ,eq(xF) [26, 43]. In this case, Equation (2) gives nχ,eq = (ζ(3)/π2)geffT3, where geff = gχ (3gχ/4) for bosonic (fermionic) χ, and ζ(x) is the Riemann zeta function. Using the entropy density in the relativistic limit as given by Equation (3), we obtain Yχ,eq(xF) = 0.28 geff/g (xF) which is insensitive to the details of freeze-out. From Equation (6), the present relic density is then given by

Relativistic DM particles in our Universe will lead to large damping scales ≳ 10 Mpc (roughly the size of typical galaxy clusters), thereby suppressing the growth of small-scale structures. They would predict a top-down hierarchy in the structure formation [44, 45], with small structures forming by fragmentation of larger ones, while observations have shown no convincing evidence of such effects, thereby imposing stringent upper limits on these “hot” DM species. For instance, the SM neutrino contribution to the non-baryonic DM relic density is currently constrained to be Ων h2 ≤ 0.0062 at 95% confidence level (CL) [36]. Thus, hot DM cannot yield the total observed DM density in our Universe [2], and if it exists,7 must coexist with other cold/warm components. For example scenarios of such multi-component DM, (see 18, 47–50).

2.3. Semi-Relativistic Case

In the intermediate regime xF ~ 1, the χ particles are semi-relativistic when they decouple from the thermal bath. The improved analytic treatment of Steigman et al. [42], as discussed in section 2.1, is not applicable in this case, since the thermally averaged cross section 〈 σ v〉 involves multiple integrals, and cannot be expanded in a Taylor series of the velocity-squared. One way is to approximate the cross section by interpolating between its relativistic and non-relativistic expressions. Following this approach, it was shown [51] that the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution can still be used to compute 〈 σ v〉, and the more appropriate Fermi-Dirac or Bose-Einstein distributions are only needed for the calculation of the freeze-out abundance Yχ,eq(xF). Note that although the current observations do not rule out the possibility of the whole DM density being comprised of warm DM species (see e.g., [52–54]), there exist strong constraints from observations of early structure, in particular from Lyman-α forest data [55, 56].

On the other hand, if the interaction of the DM particles with the thermal bath is not large enough, they may not come into full LTE before they decouple from the plasma. In such cases, their current relic density Yχ(x0) in Equation (6) will also depend on the initial abundance, and hence, on the production mechanism. This is discussed in the following section with a simple production mechanism.

3. DM from Inflaton Decay

As discussed in section 1, we assume that the DM particles χ directly couple to the inflaton field ϕ so that it can be produced in the perturbative inflaton decay for mχ < mϕ/2.8. The initial energy density stored in the inflaton field is ρϕ ≈ nϕ mϕ which is transferred to the decay products at the end of inflation, thereby (re)heating the Universe with a temperature TR. Assuming the Universe to be radiation dominated immediately after inflation, the total energy density is given by ρr = (π2/30)gT4R. 9 Hence, the initial DM number density is given by

where Bχ is the branching ratio of the inflaton decay to DM. Since we are interested in model-independent constraints on the DM parameter space, we keep our discussion general in terms of the branching ratio, without specifying its exact formula in terms of the DM-inflaton couplings, their masses, and the n-body decay kinematics (for n ≥ 2, depending on the specific DM candidates).

Once produced, depending on the strength of their interaction with the thermal plasma, they could either thermalize fully/partially with the thermal bath or could remain non-thermal throughout their evolution. In the former case, their current relic density will be determined by their freeze-out abundance, independent of the initial abundance set by the inflation parameters. This is also true for the freeze-in scenario, provided the initial abundance is small compared to the thermal abundance. In the non-thermal case, however, their final number density is essentially the same as their initial abundance, only redshifted by the Hubble expansion rate. These two different scenarios are discussed below in somewhat details, with some numerical examples.

3.1. Thermal DM

In this case, depending on their thermal annihilation rate 〈 σ v〉, the χ particles can either reach full LTE (i.e., both kinetic and chemical equilibrium) with the plasma before decoupling or decouple from the plasma before the full equilibrium could be established. The former case occurs for large annihilation rates, which enable the χ particles to attain equilibrium soon after their production. In this case, the χ particles follow the equilibrium distribution until they freeze out at a certain stage, depending on the exact value of the interaction rate. Thus, the initial abundance is irrelevant for their final relic density. In the latter case, the annihilation rates are not large enough to bring the χ particles into full LTE, and hence, their final abundance is determined by the annihilation rate as well as the initial abundance given by Equation (10). For given inflaton and DM masses, the final relic abundance Ωχ h2 will exceed the observed value for a large reheat temperature and/or large branching ratio of the inflaton to DM, thus overclosing the Universe. If the initial abundance is small, the DM particles can still be produced from the thermal plasma unless the interaction rate is utterly negligible. The dominant production in this case occurs at temperatures T ≳ mχ when the interaction rate is still larger than the Hubble rate, and as the interaction rate drops below the Hubble rate, the relic abundance will freeze-in. We discuss below both freeze-out and freeze-in scenarios for the DM produced from inflaton decay, and give a numerical example for each case to illustrate the magnitudes of the interaction cross section, as compared to the well-known thermal WIMP scenario.

3.1.1. Freeze-out

In this case, the final relic abundance of the DM species is set by the freeze-out abundance which is determined by the freeze-out temperature. This is obtained by solving the Boltzmann Equation (5) for Yχ. To calculate the freeze-out abundance more precisely, we track the evolution of the quantity Δχ = (Yχ − Yχ,eq)/Yχ,eq which represents the departure from equilibrium. From Equation (5), the evolution equation for Δ is obtained to be of the form

where Γχ, eq = nχ, eq 〈 σ v〉 = Yχ, eqs〈 σ v〉 is the equilibrium annihilation rate, and H(x) can be readily obtained from Equation (4). For a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, the equilibrium number density and thermally averaged annihilation cross section are respectively given by Gondolo and Gelmini [34]

where Kn(x) is the n-th order modified Bessel functions of the second kind, and is the center-of-mass energy. Strictly speaking, Equation (13) is only applicable for the non-relativistic case with x » 1. However, as noted in Scherrer and Turner [39] and Drees et al. [51], this is a good approximation (within 3% accuracy) even for the semi-relativistic case with x ~ 1. For the relativistic case x « 1, the final abundance is simply the equilibrium abundance, as given in Equation (9).

Following the strategy developed in Steigman et al. [42] to solve Equation (11) for Δ, we note that in the early stages of evolution, Yχ tracks Yχ,eq closely, and hence, Δ, dΔ/dx « 1. In this case, the left-hand side of Equation (11) can be safely dropped, thus leading to

As the χ particles start freezing out with increasing x, Δ increases exponentially, eventually becoming much larger than 1. Thus for some intermediate value of x = x*, Δ ~  (1), and for x > x*, it grows exponentially. We define x* when Δ(x*) ≡ Δ* = 1/2,10 and solve Equation (14) iteratively for x* as a function of mχ, 〈 σ v〉 and g*. For the logarithmic derivative of of g(T), we use the calculations of Laine and Schroeder [57] for the SM relativistic d.o.f. For the cases with no phase transition around T* = mχ/x*, g(T) is almost constant, and hence, this term can be ignored in Equation (14). Once the value of x* is found, we can determine T* = mχ/x* and Yχ(x*) = (3/2)Yχ,eq(x*) (corresponding to Δ* = 1/2). The actual freeze-out temperature TF is somewhere below T*, since at T = T*, (Γχ/H)* is still larger than 1 [42].

(1), and for x > x*, it grows exponentially. We define x* when Δ(x*) ≡ Δ* = 1/2,10 and solve Equation (14) iteratively for x* as a function of mχ, 〈 σ v〉 and g*. For the logarithmic derivative of of g(T), we use the calculations of Laine and Schroeder [57] for the SM relativistic d.o.f. For the cases with no phase transition around T* = mχ/x*, g(T) is almost constant, and hence, this term can be ignored in Equation (14). Once the value of x* is found, we can determine T* = mχ/x* and Yχ(x*) = (3/2)Yχ,eq(x*) (corresponding to Δ* = 1/2). The actual freeze-out temperature TF is somewhere below T*, since at T = T*, (Γχ/H)* is still larger than 1 [42].

For x > x*, Yχ » Yχ,eq, and hence, the Y2χ,eq term in Equation (5) can be dropped. Integrating from x = x* to x = x0, we obtain the present relic abundance:

which can be used in Equation (6) to compute Ωχ h2. To perform the integration in Equation (15), we need to know the x-dependence of 〈 σ v〉 using Equation (13) which is one of the key quantities that determine the current relic density. In general, one can find an ansatz for 〈 σ v〉 which smoothly interpolates between the non-relativistic and relativistic regimes. For simplicity, we will use the ansatz for an s-wave annihilation of two Dirac fermions [51]:

where αχ denotes the coupling constant of the four-fermion interaction, which we will treat as a free parameter. This approach works well for DM species that freeze out between 0.5 ≲ xF ≲ 15. For xF > 15 (roughly corresponding to mχ > 10 MeV), the particles are already non-relativistic at decoupling, and hence, one can expand 〈 σ v 〉 in a Taylor series in terms of the averaged relative velocity:

For s-wave annihilation, only the first term is considered, and in this case, Equation (15) simplifies further to finally yield the relic density given by Equation (7). We note that this approximation of using a constant value for 〈 σ v 〉 also works well in the semi-relativistic case, and induces an error of only about 6%, as compared to using the ansatz given by Equation (16).

From Equation (15), it is clear that the final abundance is inversely proportional to the thermal annihilation rate. Thus, the larger the cross section, the longer the DM particles stay in equilibrium with the thermal bath, and hence, the lower the final abundance. This is true for both cold and warm DM cases, while for the hot DM case, the freeze-out is insensitive to the interaction cross section, as discussed in section 2.2.

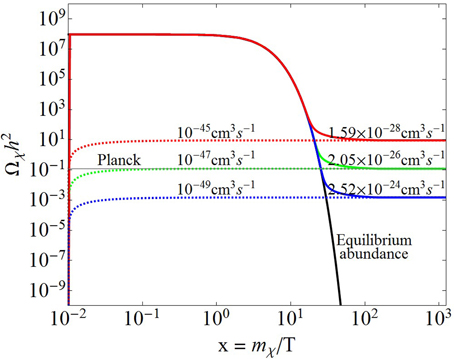

The dependence of the current relic abundance on the annihilation rate for the thermal DM which has frozen out is illustrated in Figure 1. Here we have chosen mχ = 100 GeV. The solid black line shows the equilibrium distribution which is constant in the extreme relativistic regime (x « 3), and exponentially suppressed in the non-relativistic regime (x » 3), as can also be seen from Equation (12) by taking the asymptotic limits of the Bessel function. For large enough annihilation rates, the DM particles quickly thermalize, thereafter following the equilibrium evolution until their freeze-out, and the final relic abundance is independent of the initial abundance. The observed relic density as measured by Planck, shown as the horizontal band, is obtained for the thermal annihilation rate of 〈 σ v〉 = 2 × 10−26 cm3s−1, as shown by the solid red line. As the annihilation rate decreases, the DM freezes out earlier (with smaller xF), thus giving a larger relic density.

Figure 1. The illustration of freeze-out and freeze-in scenarios in the evolution of thermal DM abundance as a function of x = mχ/T for different annihilation rates. Here we have chosen mχ = 100 GeV and for the initial conditions, mϕ = 1013 GeV, TR = 10 TeV, Bχ = 10−15. The horizontal band gives the observed relic density from Planck data [2].

3.1.2. Freeze-in

In this scenario, the DM particles are very weakly coupled to the bath, and hence, cannot reach full thermal equilibrium with the bath before decoupling. However, the feeble interactions with the thermal bath (either directly [27] or mediated by a portal [58]) could still populate the DM, until the interaction rate drops below the Hubble rate when the DM abundance will freeze in. In this case, the final abundance is directly proportional to the interaction strength; the larger the interaction cross section is, the more DM particles are produced. In this sense, freeze-in can be viewed as the opposite process to freeze-out.

The final relic density in the freeze-in scenario will in general be determined by both the interaction cross section and the initial abundance which in turn depends on the reheat temperature and the branching ratio of the inflaton in our case. Note that the decoupling in this case occurs for small values of xF, where the equilibrium abundance Yχ,eq is independent of x, as can be seen from Equation (12):

Also since the DM particles decouple very soon after being produced, the annihilation cross section as well as the number of relativistic degrees of freedom can be treated as constant with respect to x during this short period of time. Hence, the general Boltzmann Equation (5) can be approximated in this case to the following simple form:

where A and B are constants in x. Equation (19) has a simple analytic solution in terms of the initial values xi = mχ/TR and Yχ,in, where the latter can be obtained from Equations (10) and (3):

In the limit x → ∞, the expression for Yχ(x) simplifies further, and the final relic density can then be obtained using Equation (6). This has two contributions:

where the first term represents the non-thermal contribution which only depends on the initial abundance, and the other two terms represent the thermal contribution which also depend on the interaction rate. Note that the analytic expression (21) is valid as long as mχ « TR otherwise the thermal production will be delayed to lower values of temperature (or higher values of x) when the equilibrium distribution in Equation (19) may no longer be flat, but exponentially decaying. For the freeze-in scenario, it is usually assumed that the initial abundance is negligible, so that the final abundance is solely determined by the interaction strength in Equation (21), as in the freeze-out scenario. This is illustrated in Figure 1 for a typical choice of parameters: mχ = 100 GeV, mϕ = 1013 GeV, TR = 10 TeV, and Bχ = 10−15 so that the initial abundance given by Equation (20) is negligible. The different dashed lines in Figure 1 correspond to the freeze-in scenario with various interaction rates, and hence, different final abundances. Note that the final abundance increases with increasing interaction rate, in contrast with the freeze-out scenario (the solid lines) where the final abundance decreases with increasing interaction rate. As shown here, the observed relic abundance shown by the gray horizontal band can be obtained in the freeze-in scenario for an interaction rate of 10−47 cm3s−1, which is much smaller than the typical value of 2 × 10−26 cm3s−1, as in the freeze-out scenario.

We should mention here that there could be other thermal production mechanisms for the DM in specific models, depending on its interaction with the SM particles and/or the model construction for the beyond SM sector. For instance, a keV-scale sterile neutrino DM can be produced by the Dodelson-Widrow mechanism [59], which is very similar to the freeze-in mechanism discussed above.

3.2. Non-Thermal DM

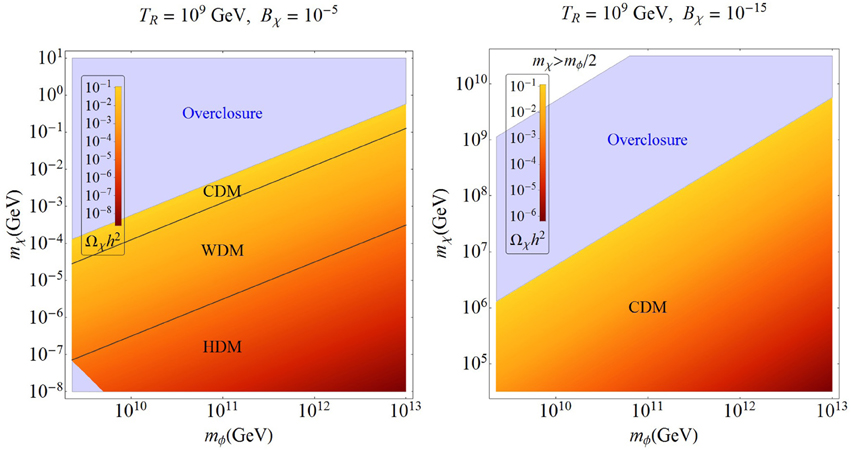

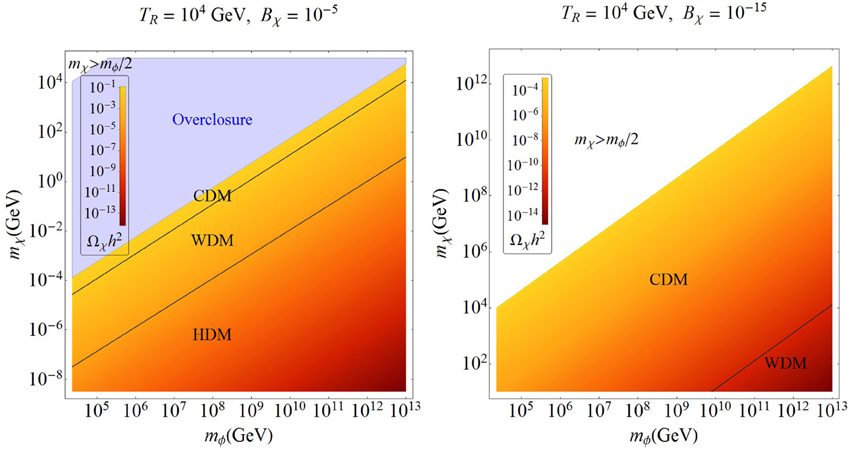

For very small cross sections, the DM particles are produced already decoupled from the thermal bath, and hence, the thermal production in Equation (21) is negligible compared to the initial abundance, which could be sizable for large branching ratios. In this case, the annihilation rate, and hence, the right-hand side of Equation (5) can be neglected, thus leading to dYχ/dx ≃ 0. Hence, the final relic abundance is completely determined by the initial one given by Equation (20). Using the general expression (6), this yields the non-thermal relic DM density

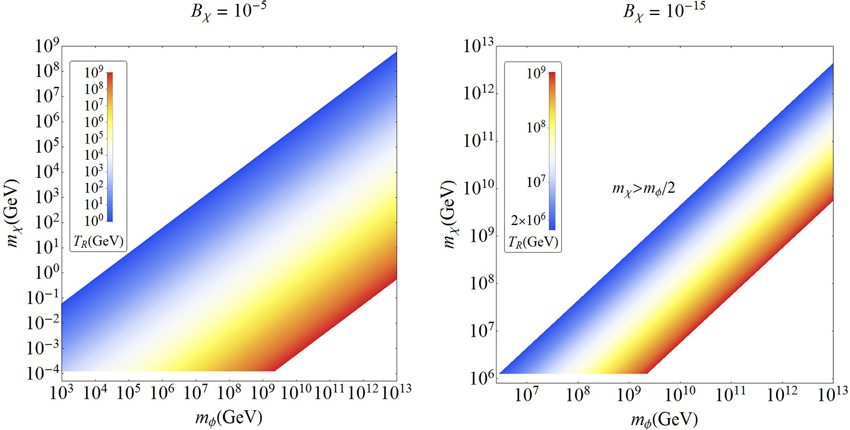

which can also be identified with the first term on the right-hand side of Equation (21). Thus for super-weak interaction rates, the final abundance only depends on the reheat temperature and inflaton branching fraction for given DM and inflaton masses11. Some illustrative cases for the non-thermal DM are shown in Figure 2 for two typical values of the branching ratio Bχ = 10−5 and 10−15. The choice of small values of Bχ will be justified below. The various contours show the reheat temperature values required to obtain the correct relic density Ωχ h2 = 0.12 for given values of the inflaton and DM masses. These plots were obtained by numerically solving the Boltzmann Equation (5) for a typical annihilation rate 〈 σ v〉 = 10−60 cm3s−1 (see section 5 for details) following the procedure mentioned above, but the results agree quite well with the approximate analytic formula given in Equation (22). From Figure 2 it is clear that as the inflaton branching fraction increases, the allowed range of the DM mass shifts to lower values in order to satisfy the observed relic density, in accordance with Equation (22). We have shown the results for the inflaton mass mϕ in the range 103 – 1013 GeV, the reheat temperature TR between 1 and 109 GeV and for the DM mass mχ ≤ mϕ/2. Note that a late-time entropy production would induce various cosmological effects, leading to a lower limit on the reheat temperature of about 1 MeV from BBN constraints [61, 62], which, when combined with the CMB and large scale structure data, improves to about 4 MeV at 95% CL [63]. However, for TR below the QCD phase transition scale, ΛQCD =  (100) MeV, the estimation of the number density of particles from inflaton decay suffers from large QCD uncertainties due to the non-perturbative hadronization effects. Hence, we have used a conservative value, which is one order of magnitude above the hadronization scale, as the minimum value of TR in Figure 2 (left panel)12.

(100) MeV, the estimation of the number density of particles from inflaton decay suffers from large QCD uncertainties due to the non-perturbative hadronization effects. Hence, we have used a conservative value, which is one order of magnitude above the hadronization scale, as the minimum value of TR in Figure 2 (left panel)12.

Figure 2. The colored contours show the reheat temperature values required to give the correct relic density for non-thermal DM as a function of the inflaton and DM masses, for a given inflaton branching ratio.

For mχ « mϕ, the non-thermal DM directly pair-produced from the inflaton decay will have a large velocity at the time of matter-radiation equality (teq), unless the reheat temperature is sufficiently high to make the velocity small due to redshift. The comoving free-streaming length of a non-thermal DM at matter-radiation equality is given by

where a(t) is the scale factor, tD is the time at inflaton decay, and

is the magnitude of the velocity of the DM particle. Integrating Equation (23), and requiring that λfs ≲ 1 Mpc, from Lyman-α constraints (for warm/cold DM), one obtains a lower limit on the reheat temperature [69]

Combining this with Equation (22), and requiring that Ωχ h2 ≤ 0.12 to satisfy the observed relic density for cold/warm DM relics, we derive an upper limit on the branching ratio of the inflaton decay to DM: Bχ ≲ 0.01(g/200)1/4. This is complementary to what is already expected from the fact that for a standard Cosmology, Bχ must be small in order to have a radiation-domination epoch immediately after reheating, followed by matter domination only at a late stage.

4. Experimental Constraints

In this section, we summarize the various experimental constraints on the DM properties relevant for our analysis.

4.1. Overclosure

For any DM candidate, we must ensure that it does not lead to an overclosure of the Universe. Thus, we set the upper limit on the relic density of our χ particles coming from inflaton decay using the observed value ΩCDMh2 = 0.1199 ± 0.0027 (68% CL; Planck + WP) [2], which combines the Planck temperature data with WMAP polarization data at low multipoles. We do not set a lower limit on Ωχ since for the cases in which the χ particles do not account for the total observed abundance, the remaining fraction can be obtained by invoking a hidden-sector/multi-component DM scenario (see e.g., 18, 47–50).

4.2. Unitarity

The partial-wave unitarity of the scattering matrix, together with the conservation of total energy and momentum, impose a generic upper bound on the cross section of thermal DM annihilation into the j-th partial wave [70]:

where vr = 2 is the relative velocity between the two annihilating particles in the center-of-mass frame with total energy . Assuming that the s-wave piece with j = 0 dominates in the partial-wave expansion, we obtain an upper bound on the thermally averaged annihilation rate 〈 σ v〉 as a function of the DM mass from Equation (13), where σ is replaced with (σ0)max from Equation (26). Since the current abundance of a non-relativistic thermal relic scales as Ωχ ∝ 1/〈 σ v〉, the observed DM relic density constrains the mass of the thermal relic to be mχ ≲ 130 TeV to satisfy the unitarity bound. Note however that this bound may not be applicable when the higher partial-waves are not suppressed, as is the case when the DM particles decouple from the thermal bath while still being relativistic.

4.3. Planck

Precision measurements of the CMB angular power spectrum by Planck put stringent constraints on the number of effective neutrino species (Neff), which parametrizes the total radiation energy density of the Universe:

where ργ = (π2/15)T4 is the energy density of photons, and the neutrino-to-photon temperature ratio Tν/Tγ = (4/11)1/3 assuming exactly three neutrino flavors and their instantaneous decoupling. In the standard cosmological model, Tν/Tγ is slightly higher than (4/11)1/3 due to partial reheating of neutrinos when electron-positron pairs annihilate transferring their entropy to photons, thus giving Neff = 3.046 [71]. Now if the DM species remains in thermal equilibrium with the neutrinos or electrons and photons after neutrino decoupling, and transfers its entropy to them during its annihilation after it decouples at a later stage, it can increase or decrease the value of Neff as we decrease the DM mass. Using the constraints on Neff from Planck [2], together with the helium abundance Yp, [72] derived a robust lower bound of 2-10 MeV on the thermal DM mass, depending on whether it is a fermion (Dirac/Majorana) or scalar (real/complex) and whether it was in equilibrium with neutrinos or with electrons and photons.

Another generic lower bound on the cold DM mass can be obtained using the CMB and matter power spectrum observations which place an upper bound on the DM temperature-to-mass ratio: T/mχ ≤ 1.07 × 10−14 (1+z)2 [73]. Evaluating this bound at matter-radiation equality with a redshift of zeq = 3391 [2] and Tγ,eq ≃ 0.77 eV [26], we obtain a lower limit of mχ ≳ 6.5 keV, which is much weaker than the limit derived in Boehm et al. [72] using Neff.

4.4. Dark Radiation

The Planck constraints on Neff can also be used to set an upper limit on the amount of dark radiation at decoupling. From Equation (27), the radiation energy density apart from the photon and SM neutrino contribution is given by

where Ωγ h2 = 2.471 × 10−5(T/2.725)4 is the CMB radiation density [36], and Δ Neff = Neff − 3.046. Using the 95% CL measured value of Neff = 3.30+0.54−0.51 from Planck+WMAP-9 polarization data+SPT high-multipole measurement+Baryon Acoustic Oscillation measurements from large scale structure surveys (Planck+WP+highL+BAO) [2], we obtain an upper limit on the amount of dark radiation from Equation (28): Ωdark h2 ≤ 4.46 × 10−6. This also sets the upper limit on the relic density of hot DM species. In order to obtain the mass range in which the thermal DM species decouple while being relativistic, we calculate their free-streaming length [74]:

where z is the redshift, and I0 = [ʃ∞0 f(0)(y)dy]/[ʃ∞0 y2f(0)(y)dy] is a dimensionless ratio, given in terms of the comoving energy distribution function f(y) = 1/exp[ + 1] with x = mχ/T and the superscript (0) refers to the current value of the distribution. From the Ly-α constraints, we require λfs(0) ≲ 1 Mpc for cold/warm DM candidates. For concreteness, we will impose the dark radiation upper limit from Equation (28) for the parameter space corresponding to λfs(0) > 2 Mpc.

4.5. BBN and CMB

The late annihilation of DM particles (after freeze out) can deposit hadronic and/or electromagnetic energy in the primordial plasma, thereby altering the history of nucleosynthesis (BBN) [75–77] and recombination (CMB) [78–85]. These effects depend only on the type and rate of energy injection into the thermal bath, thus allowing to set rather model-independent bounds on the annihilation rate, especially for DM masses in the MeV-GeV range. During nucleosynthesis, the injection of hadronic and/or electromagnetic energy can affect the abundance of nuclei via (i) raising the neutron-to-proton ratio and therefore the primordial 4He abundance, and (ii) high energy nucleons and photons disassociating nuclei. During recombination, the injected electromagnetic energy ionizes hydrogen atoms, which results in an increased number of free electrons, causing the broadening of the surface of last scattering, and results in scale-dependent changes to the CMB temperature and polarization power spectra, especially in the low multipole modes. The precision measurements of BBN and CMB from WMAP and Planck data have been used to set upper bounds on the DM annihilation cross section 〈 σ v 〉, as a function of the DM mass [75–77, 81–85].

4.6. Indirect Detection

After freeze-out, the relic annihilations of WIMP DM may be indirectly observed by searching for their annihilation products such as charged particles, photons and neutrinos (for a review, see 86). In fact, a number of indirect detection experiments have observed an excess of electrons and positrons in the charged cosmic ray flux, and this was recently confirmed with the precision measurements by AMS-02 [87]. Assuming a possible DM contribution to this positron excess and using the high quality of AMS-02 data, [88] has performed a spectral analysis to put stringent constraints on the DM annihilation cross section for various leptonic final states13. Similar constraints were obtained for the DM annihilation into hadronic final states [93, 94] in order to explain the absence of a corresponding excess in the cosmic-ray antiproton flux in the PAMELA data [95, 96].

The DM annihilation to various SM final states can also lead to an observable photon flux which can be produced either by direct DM annihilation (“prompt” gamma-rays) or by inverse Compton scattering and synchrotron emission of the electrons and positrons created in the DM annihilation. These photon signals are preferentially searched for in regions with high DM densities and/or regions with reduced astrophysical background. The Fermi-LAT, with its unprecedented sensitivity to gamma rays in the MeV-TeV energy range, has performed deep searches for line spectrum (mono-energetic gamma-rays due to direct DM annihilation) [97] as well as continuum spectrum (through DM annihilation into intermediate states)[98]14. They have derived additional constraints on the DM annihilation cross section from the isotropic diffuse gamma-ray emission in the galactic halo [100], nearby galaxy clusters [101], and nearby dwarf spheroidal galaxies [102]. Similar constraints were also derived from the galactic center region for various DM density profiles [103]. Complementing the Fermi-LAT range toward higher energies, the HESS collaboration has performed a number of DM searches up to multi-TeV DM masses [104–106].

The DM annihilation can also produce neutrinos which, like gamma-rays, can travel essentially unabsorbed through the galaxy, and can be observed at large neutrino detectors on Earth. Constraints on the DM annihilation rate were derived by the IceCube experiment from the upper limits on the high-energy neutrino fluxes from the galactic halo [107], galactic center [108], dwarf galaxies and clusters of galaxies [109]. These limits are currently somewhat weaker than the gamma-ray limits for low DM masses, but become competitive at larger DM masses. Combining the Fermi-LAT data on the diffuse gamma-ray and the IceCube data on diffuse neutrino flux, robust constraints were derived on the DM annihilation rate for heavy DM masses (1 TeV - 1010 GeV) [110].

5. Results and Discussion

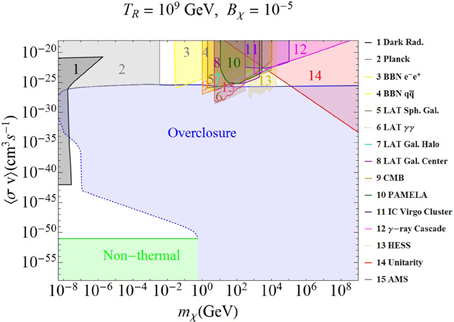

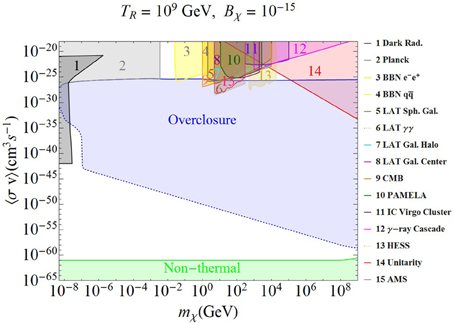

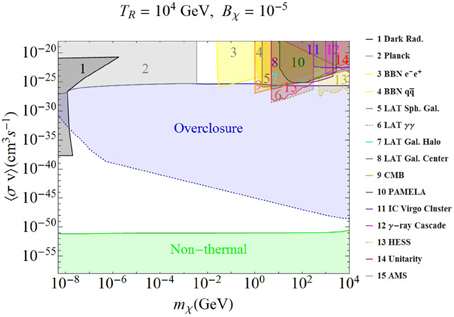

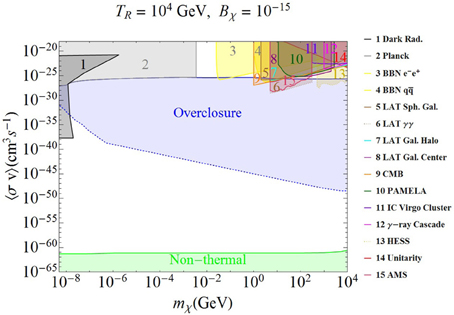

Using the model-independent approach outlined in section 3, we solve the Boltzmann equation (5) numerically for the evolution of DM produced from inflaton decay. Here we assume an s-wave annihilation, and take the annihilation rate 〈 σ v〉 to be a free parameter. 15 Both thermal and non-thermal regions are identified in the (mχ, 〈 σ v 〉) parameter space. Our results are shown in Figures 3–6 for a fixed inflaton mass mϕ = 1013 GeV. We consider two typical values of the reheat temperature TR = 109 GeV and 104 GeV, and branching ratios of the inflaton decay Bχ = 10−5 and 10−15 for our illustration purposes. We have considered the DM masses only below the reheating temperature, and do not analyze scenarios in which DM could be produced during preheating or reheating (e.g., the WIMPzilla scenario 114].

Figure 3. Model-independent constraints on the DM annihilation rate as a function of the DM mass for both thermal and non-thermal production mechanisms. Here we have chosen mϕ = 1013 GeV, TR = 109 GeV, and Bχ = 10−5 as the initial parameters for the DM evolution. The blue-shaded region is excluded from relic density constraints, and the observed relic density is obtained at its boundary (shown by the solid and dotted blue lines). The green-shaded region at the bottom represents the non-thermal DM scenario, while in the rest of the parameter space, the DM can be fully/partly thermalized with the primordial bath. The various colored-shaded regions in the thermal region are excluded (under certain assumptions) by the constraints given in section 4; see text for details.

Figure 4. The parameters and labels are the same as in Figure 3, except for Bχ = 10−15 to show the dependence on the initial conditions.

Figure 5. Same as Figure 3, except for TR = 104 GeV.

Figure 6. Same as Figure 3, except for TR = 104 GeV and Bχ = 10−15.

For each case shown in Figures 3–6, we calculate the current relic density of the thermal DM to show the overclosure region (blue-shaded) which rules out a wide range of the parameter space, irrespective of the initial choice of parameters. In the remaining allowed parameter space, we identify the region with very low annihilation rates belonging to the non-thermal DM scenario (green-shaded region) since for such extremely small interaction rates, the DM particles cannot achieve LTE, and decouple soon after being produced essentially with their initial abundance, as discussed in section 3.2. So the overclosure condition for non-thermal DM will be determined solely by the initial conditions, and this will be discussed in section 5.2.

5.1. Thermal Case

In the thermal DM regime, the region above the overclosure region with large annihilation rate belongs to the freeze-out scenario, while in the white region below the overclosure one with small annihilation rate belongs to either freeze-out or freeze-in scenario, depending on the initial conditions. The observed value of the relic density is obtained at the boundary between these regions with the overclosure region (shown by the solid and dotted blue lines). The thermal freeze-out region with large annihilation rate is severely constrained by many experimental searches, as discussed in section 4, some of which are shown by the shaded regions 1–15 in Figures 3–6, and also summarized below:

• Region 1 is excluded by the dark radiation constraint, as discussed in section 4.4. In this region, the comoving free-streaming length is greater than 2 Mpc, thus corresponding to a hot DM regime, while the relic density Ωχ h2 exceeds the upper limit of 4.46 × 10−6 derived from the Planck data [2].

• Region 2 is excluded by the recent Planck measurements of the effective number of neutrino species, as discussed in section 4.3, assuming that the DM interacts with neutrinos or electrons and photons after the neutrino decoupling. This sets a robust lower bound of order of MeV on the thermal DM mass with large interaction rates. The precise value of the lower bound depends on whether the DM is a scalar or fermion and on whether it couples to neutrinos or to electrons and photons. The bound shown by region 2 assumes a Majorana fermion DM coupling to neutrinos. Note that [72] had originally derived this limit for a cold DM candidate, but this is generically applicable as long as the interaction rate is large enough to keep the DM in LTE after the neutrino decoupling, thus transferring entropy at a late stage and affecting Neff.

• Regions 3 and 4 are excluded by the BBN data, as discussed in section 4.5, and assuming DM annihilation into electron-positron and quark-antiquark pairs respectively [77]. Similarly, the region 9 is excluded by constraints derived from a combination of the CMB power spectrum measurements from Planck, WMAP9, ACT, and SPT, and low-redshift datasets from BAO, HST and supernovae [85].

• Region 5 is excluded by the Fermi-LAT limit at 95% CL derived using the diffuse gamma-ray flux from a combined analysis of 15 dwarf spheroidal galaxies, for an NFW DM density profile and assuming DM annihilation into tau-antitau final states [102]. Region 7 is excluded by the 3σ Fermi-LAT limit obtained using the diffuse gamma-ray emission in the Milky Way halo, assuming an NFW DM distribution and for annihilation into bottom-antibottom quark pairs [100]. Region 8 is excluded by a similar analysis using the Fermi-LAT data from galactic center [103]. The corresponding limits for other SM final states are weaker, and are not shown here for clarity purposes.

• Region 6 is excluded by the Fermi-LAT 95% CL upper limit on the cross section of DM annihilation to two photons from a dedicated search for the gamma-ray line spectrum [97]. Region 13 is excluded from a complementary search for the line spectrum by HESS [106]. Note that these limits, although very stringent, can be evaded in most of the popular WIMP DM models, since the direct annihilation to photon final states is suppressed due to loop effects.

• Region 10 is excluded by the measurements of the antiproton flux from PAMELA, and assuming the DM annihilation to bb final states [94]. These limits are applicable only for hadronic final states. Similarly, region 15 is excluded by the 95% CL upper limits, derived from the AMS-02 data, on the DM annihilation cross section for e+e− final state [88]. The corresponding limits for other leptonic final states are somewhat weaker, and hence, are not shown here.

• Region 11 is excluded by the IceCube upper limit on the DM annihilation cross section for neutrino final states for the Virgo galaxy cluster including subhalos [109]. The corresponding limits for other final states as well as from searches in galactic halo [107] and galactic center [108] are somewhat weaker.

• Region 12 is excluded by the cascade gamma-ray constraints obtained using the Fermi-LAT diffuse gamma-ray background data up to very high energies [110]. The corresponding limits derived using the IceCube high-energy neutrino data are stronger at higher DM masses, but weaker than the unitarity constraint (see section 4.2).

• Region 14 is excluded by the unitarity constraints [70], as discussed in section 4.2, which sets an upper limit on the CDM mass of about 130 TeV for the allowed region, and rules out heavy thermal DM, even with annihilation rates many orders of magnitude below the thermal annihilation rate. This theoretical constraint is the most stringent one for very heavy DM, and is applicable as long as the DM is produced thermally.

Note that for the indirect detection constraints, we have shown only a few of them (typically the most stringent ones) for illustration purposes. Most of these limits have limited applicability, as they were derived assuming DM annihilation into a particular final state, and could be evaded in specific models where some of these annihilation channels might be suppressed due to various reasons. Also note that additional constraints on the annihilation cross section for a given DM mass might be derived using possible correlations with the DM direct detection cross section limits [115] and collider search limits from mono-jet [116, 117] and mono-photon [118, 119] final states with large missing energy. In the absence of a collider signal for DM, model-independent constraints can be derived on the mass and interactions of a generic WIMP DM candidate from direct and indirect detection searches [120].

The other allowed thermal DM parameter space, namely, the region with very low interaction rates such as the FIMP scenario, is hard to constrain from the existing experimental limits. Various experimental tests of the freeze-in mechanism by measurements at colliders or by cosmological observations were outlined in Hall and Jedamzik [27]. However, these signals depend very much on the particular freeze-in scenario under consideration, and hence, it is difficult to derive model-independent constraints in the (mχ,〈 σ v〉) parameter space, except for the generic dark radiation constraint as shown in Figures 3–6. Just to give an example of additional model-specific bounds, a keV-scale sterile neutrino DM, which has a small interaction rate due to its mixing with the active neutrinos, could radiatively decay to an active neutrino and a photon which will lead to a mono-energetic X-ray line [121], the absence of which puts severe constraints on such keV-scale DM models, including their production mechanisms [122].

5.2. Non-Thermal Case

Now we move on to discuss the non-thermal DM region (green-shaded) in Figures 3–6. As already discussed at length in section 3.2, the final relic density of these DM particles is solely determined by the initial conditions, which in our case, are set by the inflaton and DM masses, the reheat temperature and the branching ratio of the inflaton decay to DM. For fixed reheat temperature and inflaton branching ratio, we show in Figures 7, 8 the contours for relic density computed using Equation (22) in the (mϕ, mχ) plane. We also calculate the comoving free-streaming length using Equation (23), and identify the regions with λfs < 10 kpc as cold DM (CDM), with λfs > 2 Mpc as hot DM (HDM), and the rest as warm DM (WDM). Note that there is no well-defined boundary between these regions, and we have just chosen some typical values derived from various astrophysical data [56, 74] for our illustration purposes. We find that the observed DM relic density can be satisfied for a narrow parameter space in the CDM region (the boundary between the blue and orange regions), and the region above this is excluded due to overclosure constraints. For the HDM case with TR = 109 GeV and Bχ = 10−5 (Figure 7, left panel), an additional portion of the parameter space (blue-shaded region at bottom-left corner) is ruled out due to the dark radiation constraint, as discussed in section 4.4.

Figure 7. The color-coded contours show the relic density of non-thermal DM produced from inflaton decay as a function of the inflaton and DM masses for a fixed reheated temperature TR = 109 GeV and fixed inflaton branching ratios Bχ = 10−5 and 10−15. We identify the cold, warm and hot DM regions in each case by assuming that the corresponding free-streaming length given by Equation (23) should be <10 kpc, between 10 kpc - 2 Mpc, and above 2 Mpc respectively. The blue-shaded region for the CDM case is excluded by the overclosure constraint, as discussed in section 4.1. The additional blue-shaded region in the HDM case is ruled out by the dark radiation limit, as discussed in section 4.4.

Figure 8. The labels are the same as in Figure 7. Here TR = 104 GeV.

Similar to the thermal DM case, additional constraints can be derived for specific non-thermal DM candidates. For instance, a popular class of such candidates, known as the Weakly Interacting sub-eV particles (WISPs) such as axions and axion-like particles which often arise as the Nambu-Goldstone bosons associated with some global symmetry breaking, can be constrained from various low-energy experiments involving lasers, microwave and optical cavities, strong electromagnetic fields or torsion balances [123].

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have investigated the thermal and non-thermal properties of DM from inflaton decay in a model-independent manner, assuming that the reheating and thermalization of the ambient plasma have happened instantly at a given unique temperature. In the thermal DM scenario, the relic abundance of the DM species is determined by the freeze-out abundance, irrespective of the initial conditions or production mechanism, provided its interaction with the thermal bath is large enough to bring it into LTE soon after its production. For smaller interaction rates when the DM does not attain full LTE, but can still be produced from the thermal bath, one can also obtain the correct relic density through freeze-in mechanism. On the other hand, if the interaction rate is negligibly small so that the DM remains decoupled from the thermal bath from the beginning, the relic density is essentially determined by the initial conditions. Assuming that the DM has a non-zero coupling to the inflaton so that it can be directly produced from the inflaton decay, we have investigated all the above scenarios by tracking the evolution of the DM species from the very onset of its production. We have numerically solved the Boltzmann equation for DM number density, and have shown that the inflaton decay to DM inevitably leads to an overclosure of the Universe for a large range of parameter space, especially for non-thermal DM scenarios. This is an important constraint for hidden sector DM models with an arbitrary DM coupling to the inflaton. For the thermal DM scenario with large annihilation rates, we show the complementary constraints on the DM parameter space from various experimental searches. On the other hand, the other viable regions for both thermal and non-thermal DM candidates with very small interaction rate remain mostly unexplored.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Celine Boehm for useful discussions. The work of P. S. Bhupal Dev and Anupam Mazumdar is supported by the Lancaster-Manchester-Sheffield Consortium for Fundamental Physics under STFC grant ST/J000418/1.

Footnotes

1. ^Note that the DM particles can also be created from the scatterings of the inflaton quanta as it happens in the case of preheating [8], but here we will not discuss this scenario as the detailed computation of such processes requires both analytic and lattice simulations, and a precise definition of the reheat temperature of the Universe which goes well beyond the scope of the present paper.

2. ^During inflation, there could be many fields dynamically present [14]—some may assist during inflation, and some may obtain quantum-induced vacuum fluctuations to be displaced at very large vacuum expectation values, commonly known as “moduli” in string theory [15]. They typically couple very weakly via Planck-suppressed interactions. Their decay products could also create DM, (see e.g., 16, 17).

3. ^Again a concrete example is MSSM inflation in which case the lightest supersymmetric particle, e.g., gravitino or neutralino, could be excited directly from the inflaton decay or its decay products [22], besides the SM d.o.f. Since gravitinos mostly interact via Planck-suppressed interactions, their abundance will freeze out soon after their production and will be mainly determined by the reheat temperature, while neutralinos have weak interactions and can be quickly brought into kinetic equilibrium (though not necessarily chemical equilibrium) with the bath. Therefore irrespective of how the neutralinos were initially created, their final abundance is always set by the thermal decoupling temperature, as long as TR ≥ mχ [23]. On the other other, for low reheating temperatures below the standard freeze-out temperature TF ~ mχ/20, neutralinos could be a non-thermal DM candidate [24, 25].

4. ^An alternative example where the DM could still be produced from the thermal bath, while its relic abundance is fixed by the reheating temperature is the Non-equilibrium thermal DM scenario [31].

5. ^For the non-relativistic case, v is approximated by the relative velocity vr = |v1 − v2|, while in the general case, it is usually taken to be the Møller velocity v = . Here we use the manifestly Lorentz-invariant definition: v = v/(1 − v1 · v2) = /(p1 · p2), where p1, p2 are the four-momenta of the annihilating particles with mass m1 and m2 respectively [32].

6. ^gs and gρ differ only when there are relativistic species not in equilibrium with photons which happens in the SM for temperatures below the electron mass when the neutrinos have already decoupled from the thermal bath, and e± pair-annihilation transfers entropy only to the photons, thus making gs slightly higher than gρ today.

7. ^Recently, the presence of a hot DM component at 3σ CL has been proposed to resolve the inconsistencies of the Planck measurements with other observations, such as the current Hubble rate, the galaxy shear power spectrum and galaxy cluster counts [46].

8. ^This is the necessary condition required solely due to kinematic reasons, and could be sufficient, for instance, for fermionic DM coupling to the inflaton through a ϕχ χ term in the Lagrangian. For more complicated inflaton decay chains involving many particles, a more stringent kinematic condition may be required. Also we do not consider derivative couplings of the inflaton with DM, which could be the case for axion DM, for example.

9. ^Note that the assumption ρϕ = ρr = (π2/30)gTR4 which determines the reheat temperature may not be correct for all possible inflaton or moduli coupling to the M d.o.f. This definition is correct for large inflaton coupling to matter, i.e., αϕ ≥ 10−7 [21]. Typically the moduli coupling to the SM d.o.f and DM will be very small, i.e., αϕ ~ (mϕ/mpl)2. Therefore, a more rigorous treatment of the reheating scenario is required for the case of moduli decay.

10. ^As verified in [42], other alternative choices of Δ* change the final result only by about 0.1%.

11. ^Similar results were obtained in Campos et al. [60] for superheavy metastable DM candidates. Our result is valid for all non-thermal DM production mechanisms as long as it is a perturbative process.

12. ^One should also note that for TR below the electroweak phase transition scale, ΛEW =  (100) GeV, one cannot use the standard electroweak sphaleron processes to explain the observed baryon asymmetry, and must invoke a post-sphaleron baryogenesis mechanism[64–68].

(100) GeV, one cannot use the standard electroweak sphaleron processes to explain the observed baryon asymmetry, and must invoke a post-sphaleron baryogenesis mechanism[64–68].

13. ^A DM interpretation of the AMS-02 positron excess is still viable, if the DM annihilates to four-lepton final states [89–92].

14. ^There exists yet another class of spectral signature, namely, box-shaped gamma-ray spectrum, which arises if the DM annihilates/decays into intermediate particles which further decay into photons [99]. The cross-section limits derived using this feature are currently comparable to those obtained using the line-like spectral feature.

15. ^For a p-wave annihilation, 〈 σ v〉 depends on the temperature, and hence, cannot be taken as a free parameter in the Boltzmann equation. Our assumption also obliterates additional complications that could arise in special cases such as co-annihilation and resonant annihilation. However, these are highly model-dependent effects, and we cannot easily generalize our results to such scenarios. A more accurate, model-specific numerical analysis for the relic density can be done with publicly available codes [111–113].

References

1. Bertone G, Hooper D, Silk J. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints. Phys Rept. (2005) 405:279. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2004.08.031

2. Ade PAR, Aghanim N, Armitage-Caplan C, Arnaud M, Ashdown M, Atrio-Barandela F, et al. [Planck Collaboration], Planck 2013 results. XVI. cosmological parameters. (2013). Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1303.5076

3. Ade PAR, Aghanim N, Armitage-Caplan C, Arnaud M, Ashdown M, Atrio-Barandela F, et al. [Planck Collaboration], Planck 2013 results. XXII. constraints on inflation. (2013). Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1303.5082

4. Mazumdar A, Rocher, J. Particle physics models of inflation and curvaton scenarios. Phys Rept. (2011) 497:85. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2010.08.001

5. Liddle AR, Lyth D. Cosmological Inflation and Large-scale Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2000).

6. Iocco F, Mangano G, Miele G, Pisanti O, Serpico PD. Primordial Nucleosynthesis: from precision cosmology to fundamental physics. Phys Rept. (2009) 472:1. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2009.02.002

7. Allahverdi R, Brandenberger R, Cyr-Racine FY, Mazumdar A. Reheating in inflationary cosmology: theory and applications. Ann Rev Nucl Part Sci. (2010) 60:27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nucl.012809.104511

8. Kofman L, Linde AD, Starobinsky AA. Towards the theory of reheating after inflation. Phys Rev D (1997) 56:3258. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.56.3258

9. Allahverdi R, Enqvist K, Garcia-Bellido J, Mazumdar A. Gauge invariant MSSM inflaton. Phys Rev Lett. (2006) 97:191304. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.191304

10. Allahverdi R, Kusenko, A, Mazumdar A. A-term inflation and the smallness of neutrino masses. JCAP (2007) 0707:018. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2007/07/018

11. Allahverdi R, Enqvist K, Garcia-Bellido J, Jokinen A, Mazumdar A. MSSM flat direction inflation: slow roll, stability, fine tunning and reheating. JCAP (2007) 0706:019. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2007/06/019

12. Lyth DH, Stewart ED. Thermal inflation and the moduli problem. Phys Rev D (1996) 53:1784. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.53.1784

13. Moroi T, Randall L. Wino cold dark matter from anomaly mediated SUSY breaking. Nucl Phys B (2000) 570:455. doi: 10.1016/S0550-3213(99)00748-8

14. Liddle AR, Mazumdar A, Schunck FE. Assisted inflation. Phys Rev D (1998) 58:061301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.58.061301

15. de Carlos B, Casas JA, Quevedo F, Roulet E. Model independent properties and cosmological implications of the dilaton and moduli sectors of 4-d strings. Phys Lett B (1993) 318:447. doi: 10.1016/0370-2693(93)91538-X

16. Kohri K, Mazumdar A, Sahu N. Inflation, baryogenesis and gravitino dark matter at ultra low reheat temperatures. Phys Rev D (2009) 80:103504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.80.103504

17. Evans JL, Garcia MAG, Olive KA. The Moduli and Gravitino (non)-Problems in Models with Strongly Stabilized Moduli. JCAP (2014) 1403:022. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2014/03/022

18. Chialva D, Dev PSB, Mazumdar A. Multiple dark matter scenarios from ubiquitous stringy throats. Phys Rev D (2013) 87:063522. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.87.063522

19. Enqvist K, Kasuya S, Mazumdar A. Reheating as a surface effect. Phys Rev Lett. (2002) 89:091301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.091301

20. Enqvist K, Kasuya S, Mazumdar A. Inflatonic solitons in running mass inflation. Phys Rev D (2002) 66:043505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.66.043505

21. Mazumdar A, Zaldivar, B. Quantifying the reheating temperature of the universe. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1310.5143

22. Allahverdi R, Ferrantelli A, Garcia-Bellido J, Mazumdar A. Non-perturbative production of matter and rapid thermalization after MSSM inflation. Phys Rev D (2011) 83:123507. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.83.123507

23. Giudice GF, Kolb EW, Riotto A. Largest temperature of the radiation era and its cosmological implications. Phys Rev D (2001) 64:023508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.64.023508

24. Fornengo N, Riotto A, Scopel S. Supersymmetric dark matter and the reheating temperature of the universe. Phys Rev D (2003) 67:023514. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.67.023514

25. Gelmini GB, Gondolo P. Neutralino with the right cold dark matter abundance in (almost) any supersymmetric model. Phys Rev D (2006) 74:023510. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.74.023510

27. Hall LJ, Jedamzik K, March-Russell J, West SM. Freeze-in production of FIMP dark matter. JHEP (2010) 1003:080. doi: 10.1007/JHEP03(2010)080

28. Feng JL, Rajaraman A, Takayama F. Superweakly interacting massive particles. Phys Rev Lett. (2003) 91:011302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.011302

29. Allahverdi R, Drees M. Production of massive stable particles in inflaton decay. Phys Rev Lett. 89:091302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.091302

30. Allahverdi R, Drees M. Thermalization after inflation and production of massive stable particles. Phys Rev D (2002) 66:063513. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.66.063513

31. Mambrini Y, Olive KA, Quevillon J, Zaldivar B. Gauge coupling unification and non-equilibrium thermal dark matter. Phys Rev Lett. (2013) 110:241306. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.241306

32. Cannoni M. Relativistic 〈 σ vrel 〉 in the calculation of relics abundances: a closer look. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1311.4508

33. Srednicki M, Watkins R, Olive KA. Calculations of relic densities in the early universe. Nucl Phys B (1988) 310:693. doi: 10.1016/0550-3213(88)90099-5

34. Gondolo P, Gelmini G. Cosmic Abundances of Stable Particles: improved analysis. Nucl Phys. (1991) B360:145. doi: 10.1016/0550-3213(88)90099-5

35. Fixsen DJ. The temperature of the cosmic microwave background. Astrophys J. (2009) 707:916. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/707/2/916

36. Beringer J, Arguin JF, Barnett RM, Copic K, Dahl O, Groom DE, et al. Particle data group. Phys Rev. (2012) D86:010001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.86.010001

37. Peebles PJE. The Large-Scale Structure Of The Universe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1980).

38. Primack JR. Dark matter and structure formation. In: Dekel A and Ostriker JP, editors. Proceedings of the Jerusalem Winter School; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (1996).

39. Scherrer RJ, Turner MS. On the relic, cosmic abundance of stable weakly interacting massive particles. Phys Rev D (1986) 33:1585.

40. Kamionkowski M, Turner MS. Thermal relics: do we know their abundances? Phys Rev D (1990) 42:3310. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.42.3310

41. Griest K, Seckel D. Three exceptions in the calculation of relic abundances. Phys Rev D (1991) 43:3191. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.43.3191

42. Steigman G, Dasgupta B, Beacom JF. Precise relic WIMP abundance and its impact on searches for dark matter annihilation. Phys Rev D (2012) 86:023506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.86.023506

43. Cowsik R, McClelland J. An upper limit on the neutrino rest mass. Phys Rev Lett. (1972) 29:669. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.29.669

44. Bond JR, Efstathiou G, Silk J. Massive neutrinos and the large scale structure of the universe. Phys Rev Lett. (1980) 45:1980. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.1980

45. Bond JR, Szalay AS. The collisionless damping of density fluctuations in an expanding universe. Astrophys J. (1983) 274:443. doi: 10.1086/161460

46. Hamann J, Hasenkamp J. A new life for sterile neutrinos: resolving inconsistencies using hot dark matter. JCAP (2013) 1310:044. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2013/10/044

47. Zurek KM. Multi-component dark matter. Phys Rev D (2009) 79:115002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.79.115002

48. Feldman D, Liu Z, Nath P, Peim G. Multicomponent dark matter in supersymmetric hidden sector extensions. Phys Rev D (2010) 81:095017. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.81.095017

49. Winslow PT, Sigurdson K, Ng JN. Multi-state dark matter from spherical extra dimensions. Phys Rev D (2010) 82:023512. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.82.023512

50. Dienes KR, Thomas B. Dynamical dark matter: I. theoretical overview. Phys Rev D (2012) 85:083523. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.85.083523

51. Drees M, Kakizaki M, Kulkarni S. The thermal abundance of semi-relativistic relics. Phys Rev. (2009) D80:043505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.80.043505

52. Lin WB, Huang DH, Zhang X, Brandenberger RH. Nonthermal production of WIMPs and the subgalactic structure of the universe. Phys Rev Lett. (2001) 86:954. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.954

53. Hisano J, Kohri K, Nojiri MM. Neutralino warm dark matter. Phys Lett B (2001) 505:169. doi: 10.1016/S0370-2693(01)00395-1

54. Gelmini G, Yaguna CE. Constraints on minimal SUSY models with warm dark matter neutralinos. Phys Lett B (2006) 643:241. doi: 10.1016/j.physletb.2006.10.063

55. Boyarsky A, Lesgourgues J, Ruchayskiy O, Viel M. Lyman-alpha constraints on warm and on warm-plus-cold dark matter models. JCAP (2009) 0905:012. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2009/05/012

56. Viel M, Becker GD, Bolton JS, Haehnelt MG. Warm Dark Matter as a solution to the small scale crisis: new constraints from high redshift Lyman-alpha forest data. Phys Rev D (2013) 88:043502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.88.043502

57. Laine M, Schroeder Y. Quark mass thresholds in QCD thermodynamics. Phys Rev. (2006) D73:085009. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.73.085009

58. Blennow M, Fernandez-Martinez E, Zaldivar B. Freeze-in through portals. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1309.7348

59. Dodelson S, Widrow LM. Sterile-neutrinos as dark matter. Phys Rev Lett. (1994) 72:17. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.17

60. Campos AH, Lengruber LL, Reis HC, Rosenfeld R, Sato R. Bounds on direct couplings of superheavy metastable particles to the inflaton field from ultra high energy cosmic ray events. Mod Phys Lett. (2002) A17:2179. doi: 10.1142/S0217732302008915

61. Kawasaki M, Kohri K, Sugiyama N. Cosmological constraints on late time entropy production. Phys Rev Lett. (1999) 82:4168. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4168

62. Kawasaki M, Kohri K Sugiyama N. MeV scale reheating temperature and thermalization of neutrino background. Phys Rev D (2000) 62:023506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.62.023506

63. Hannestad S. What is the lowest possible reheating temperature? Phys Rev D (2004) 70:043506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.70.043506

64. Dimopoulos S, Hall LJ. Baryogenesis at the MeV Era. Phys Lett B (1987) 196:135. doi: 10.1016/0370-2693(87)90593-4

65. Cline JM, Raby S. Gravitino induced baryogenesis: a problem made a virtue. Phys Rev D (1991) 43:1781. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.43.1781

66. Babu KS, Mohapatra RN, Nasri S. Post-sphaleron baryogenesis. Phys Rev Lett. (2006) 97:131301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.131301

67. Babu KS, Dev PSB, Mohapatra RN. Neutrino mass hierarchy, neutron - anti-neutron oscillation from baryogenesis. Phys Rev D (2009) 79:015017. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.79.015017

68. Babu KS, Dev, PSB, Fortes ECFS, Mohapatra RN. Post-sphaleron baryogenesis and an upper limit on the neutron-antineutron oscillation time. Phys Rev D (2013) 87:115019. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.87.115019

69. Takahashi F. Gravitino dark matter from inflaton decay. Phys Lett. (2008) B66:100. doi: 10.1016/j.physletb.2007.12.048

70. Griest K, Kamionkowski M. Unitarity limits on the mass and radius of dark matter particles. Phys Rev Lett. (1990) 64:615.

71. Mangano G, Miele G, Pastor S, Pinto T, Pisanti O, Serpico PD. Relic neutrino decoupling including flavor oscillations. Nucl Phys B (2005) 729:221. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2005.09.041

72. Boehm C, Dolan MJ, McCabe C. A lower bound on the mass of cold thermal dark matter from planck. JCAP (2013) 1308:041. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2013/08/041

73. Armendariz-Picon C, Neelakanta JT. How cold is cold dark matter? JCAP (2014) 1403:049. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2014/03/049

74. Boyanovsky D. Free streaming in mixed dark matter. Phys Rev. (2008) D77:023528. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.77.023528

75. Jedamzik K. Big bang nucleosynthesis constraints on hadronically and electromagnetically decaying relic neutral particles. Phys Rev D (2006) 74:103509. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.74.103509

76. Hisano J, Kawasaki M, Kohri K, Moroi T, Nakayama K. Cosmic rays from dark matter annihilation and big-bang nucleosynthesis. Phys Rev D (2009) 79:083522. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.79.083522

77. Henning B, Murayama H. Constraints on light dark matter from big bang nucleosynthesis. (2012). Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:1205.6479

78. Galli S, Iocco F, Bertone G, Melchiorri A. CMB constraints on Dark Matter models with large annihilation cross-section. Phys Rev D (2009) 80:023505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.80.023505

79. Slatyer TR, Padmanabhan N, Finkbeiner DP. CMB constraints on WIMP annihilation: energy absorption during the recombination epoch. Phys Rev D (2009) 80:043526. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.80.043526