- 1Department of Pharmacognosy and Natural Products Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 2Faculty of Agriculture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

A review research was conducted to provide an overview of the ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants and traditional medical practices for the treatment of skin disorders in Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. The geographical and ecological characteristics of the Balkan Peninsula and Mediterranean Sea, along with the historical connection among those countries, gave rise to the development of a distinct flora and to the uses of common medicinal plants against various skin ailments, respectively. The review focuses on the detailed study of 128 ethnobotanical surveys conducted in these areas and the species used for skin ailments were singled out. The analysis showed that 967 taxa belonging to 418 different genera and 111 different families are used in the treatment of skin related problems. The majority of the plants belong to the families of Asteraceae (11.7%), Lamiaceae (7.4%), Rosaceae (6.7%), Plantaginaceae (5.4%), and Malvaceae (3.8%). Their usage is internal or external to treat ailments such as wounds and burns (22.1%), hemorrhoids (14.7%), boils, abscesses, and furuncles (8.2%). Beside specific skin disorders, numerous species appeared to be used for their antifungal, antimicrobial, and antiseptic activity (9.1%). Literature evaluation highlighted that, the most commonly used species are Plantago major L. (Albania, Turkey), Hypericum perforatum L. (Greece, Turkey), Sambucus nigra L. (Cyprus, Greece), Ficus carica L. (Cyprus, Turkey), Matricaria chamomilla L. (Cyprus, Greece), and Urtica dioica L. (Albania, Turkey), while many medicinal plants reported by interviewees were common in all four countries. Finally, to relate this ethnopharmacological knowledge and trace its expansion and diversification through centuries, a comparison of findings was made with the use of the species mentioned in Dioscorides’ “De Materia Medica” for skin disorders. This work constitutes the first comparative study performed with ethnobotanical data for skin ailments gathered in the South Balkan and East Mediterranean areas. Results confirm the primary hypothesis that people in Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey are closely related in terms of traditionally using folk medicinal practices. Nevertheless, more field studies conducted, especially in remote places of these regions, can help preserve the traditional medical knowledge, aiming at the discovery of new phytotherapeutics against dermatological diseases.

Introduction

Herbal therapies have been used for the treatment of skin conditions for centuries in the Balkan countries, while several plant compounds are still used in topical treatments (Jarić et al., 2018). The most frequent categories for which medicinal plants and their preparations are used are wounds, hemorrhoids, boils, and eczema, while they are also commonly applied for their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity contributing to skin healing. For example, Plantago major L. is the most cited species for the treatment of traumas, wounds, and boils while Urtica dioica L. is principally mentioned to be applied topically against eczemas. Among the preparation forms, ointment, decoction, compress, and poultice are some of the most representative and regularly comprise the basis for the formulation of commercial products employed widely to cure skin ailments (e.g., Histoplastin Red®, Contractubex Gel®). The Balkan Peninsula and the Mediterranean Sea appertain to an area characterized by a high plant biodiversity and an important tradition in folk medicine. The diversity of the flora and the presence of endemism are strongly connected to the geographical position, the climate, and the geological composition (Varga et al., 2019; Emre et al., 2021). Phytogeographical analysis of the study area shows that 51% of the taxa are “narrows” (restricted to the Balkan Peninsula and Italy or the Balkan Peninsula and Anatolia), and 49% are more widely distributed (Strid, 1986). Environmental heterogeneity is high in the Mediterranean basin and this contributes to the high vascular plant species richness, especially in the eastern Mediterranean, due to evolutionary history and past climate. In particular, Last Glacial Maximum climate may have significantly shaped the current longitudinal and altitudinal patterns of species and genetic diversity trend in the Mediterranean (Fady and Conord, 2010). More specifically, all four countries included in the present review are divided in different phytogeographical regions. The floristic regions of Greece are 13 and are represented by North East, North Central, Northern Pindos, East Central, Southern Pindos, Ionian Islands, Sterea Ellas, West Aegean Islands, Peloponnisos, Kiklades, North Aegean Islands, East Aegean Islands, Kriti, and Karpathos (Annotations [Internet], 2022). Turkey has various macro/micro climates and vegetation types along with three overlapping phytogeographic regions represented by the Euro-Siberian, the Mediterranean, and the Irano-Turanian (Özşahin et al., 2019). This combination of geology and geography with topographic and climatic variation (Çolak and Rotherham, 2006) results in unusual levels of plant diversity and endemism. The phytogeographical divisions of Cyprus are 8 and are defined by the following regions: Akamas peninsula, Troodos range, the South area around Limassol, Larnaca area, the east part of Central plain, the west part of Central plain, the northern slopes and peaks of Pentadactylos, and Karpasia peninsula (Hadjichambis et al., 2004). The phytogeographical districts of Albania are represented by district of Berat, district of Burrel, district of Delvinë, district of Dibër, district of Elbasan, district of Kolonjë, district of Korçë, district of Lezhë, district of Librazhd, district of Mat, district of Përmet, district of Pogradec, district of Pukë, district of Sarandë, district of Tepelenë, district of Tiranë, district of Tropojë, and district of Vlorë (Barina and Pifkó, 2011). Despite the rich diversity and importance of flora as well as the presence of endemism in the study area, only a small proportion of the classified plants have been investigated and chemically characterized (Hoffmann et al., 2020). However, during the last years the therapeutic potential of an important number of medical plants traditionally used in dermatology has been explored, and some of them have been developed and approved as drugs or medical devices for the treatment of skin disorders (Tabassum and Hamdani, 2014). In defiance of all the prodigious advancements in modern phytochemical and medical research, ethnopharmacology of traditional medicinal plants in the Balkan and Southeast Mediterranean Region could be served as an important tool, providing a comprehensive approach to health systems in the countries of the area, preserving cultural diversity and strengthening the traditional medicine itself. The traditional practices and the ethnobotanical knowledge deriving from herbal manuscripts, could be exploited and used as a founding pillar, leading to the discovery of new bioactive natural products for the treatment of various problematic skin conditions. The aim of this review is to reveal, compare and contrast the traditional medical practices and the ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants for the treatment of skin disorders in Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. This was accomplished through a profound literature research on the ethnopharmacological field studies conducted in these four countries and through the listing of the information reported in order to collect the plant uses against problematic skin conditions. As a second target and to associate the bulk of ethnopharmacological data and confirm its expansion and diversification through centuries, we drew a parallel between the uses of the medicinal species reported against skin disorders in the articles we studied, and the ones mentioned in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica for the same purpose.

Skin Disorders

The skin represents the largest organ of the integumentary system with a surface of 2 m2. Its main function is to protect the underlying tissues such as muscles, bones, and internal organs. The skin is made up of a series of tissues of ectodermal and mesodermal origin and as a sequel of the orifices it continues with the respective mucous membranes forming a layer without interruptions. It is also characterized by an important distensibility and resistance (Anastasi et al., 2012). The skin acts as a protective envelope to the body and is closely connected to the underlying fascial endoskeleton through blood vessels, nerves, retinacular ligaments, and lymphatics. It consists of the epidermis which is mainly made of epithelial and is the most superficial and biologically active of the skin’s layers. As the basal layer of the epithelium (stratum basale) is constantly renewing. The second skin layer is the dermis which is considered to be the “core” of the integumentary system and provides most of the mechanical strength to the skin. The dermis is composed by the papillary and the reticular, both composed by connective tissue with fibers of collagen. Finally, the hypodermis, also called the subcutaneous layer, mainly consists of loose connective tissue and connects the skin to the underlying fibrous tissue of the bones and muscles (Wong et al., 2016). Skin disorders represent a very common problematic event and can affect all individuals during their life. Even a slight and superficial wound can lead to more serious pathological states, and trigger conditions that are difficult to control such as secondary bacterial infections, failure or abnormal progression of the healing process that promotes chronic wounds or scar formation both aesthetically and functionally altered. Since ancient times, all populations-including the Balkans-used various medicinal plants as a remedy against problematic skin ailments. Traditional medical practices have represented for hundreds of years the only resource for skin care, and still today maintain a very important role thanks to the multitasking characteristics possessed by the phytocomplex (Gertsch, 2011). Skin diseases are classified in various ways. One of these is based on the next three factors: 1) site of involvement such as facial rashes, lesions on sun-exposed sites, 2) pathogenesis such as genetic abnormalities, infectious etiology, or autoimmune mechanisms, 3) main structure affected such as epidermal diseases, abnormalities of melanocytes, and vascular changes. These good-standing categorizations are getting enriched as the science of dermatology expands and evolves. The genetic predisposition and immune system represent two important factors that can affect the various classification methods. The most common symptoms that turn up and characterize a skin pathological condition, include pain which is manifested as stinging and/or burning, itch that may be sporadic or persistent, localized or generalized, as well as functional disability (Mphande, 2020).

Dioscorides and “De Materia Medica”

Over the last decades, research on medicinal plants has increasingly focused on the study of historical medico-botanical texts to identify plant species for further drug discovery and to comprehend the development of modern pharmacopoeias (Touwaide, 1992; Buenz et al., 2005; Leonti et al., 2010; Adams et al., 2011; Dal Cero et al., 2014). As a case in point, it is widely acknowledged that Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica has influenced and guided the development of Mediterranean and European traditional herbal medicine (Gurib-Fakim, 2006). Pedanius Dioscorides was born in Anazabra in the Cilicia Region of Anatolia in the first century A.D. It is known that he was a military physician in the Roman Army who travelled extensively in order to seek and explore medicinal substances to treat various ailments including skin diseases (Yildirim, 2013). Between AD 50 and 70, Dioscorides wrote his fundamental work that consists of a five-volume book in his native Greek, Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς (Peri hyles iatrikēs), known in Latin as De Materia Medica. Among many Greek manuscripts and texts, De Materia Medica, became the precursor to all modern pharmacopeias and transmitted the idea that investigation and experimentation performs a crucial role for pharmacology (Rooney, 2012). De Materia Medica is the most important text of botany and pharmacognosy, as well as the most detailed pharmacognostic guide that passed down from the ancient Mediterranean world, representing the prime historical source of information about the medicines used by the Greeks, Romans and other ethnic groups of antiquity. De Materia Medica incorporates 800 chapters in which Dioscorides monographed 600 different kinds of plants, 35 animals, and 90 minerals, summarizing the quintessence of medicinal remedies. Moreover, it includes detailed information about those drugs, such as their medical activities, methods of administration, habitat and methods of cultivation, botanical descriptions also illustrated by plant drawings, contraindications, dosages, veterinary, and non-medical uses (Gunther, 1968). In addition, Dioscorides drew on previous writings, his own experience as a physician as well as on local traditions in the Mediterranean and the Near East. Based on geographical references in the text, Dioscorides’ compilation is thought to be the fruit of extensive journeys while the predominant but contentious view is that he travelled extensively throughout Anatolia, Egypt, Arabia, Persia, Gallia, North Africa, and Caucasia (Staub et al., 2016). De Materia Medica is the most comprehensive and systematic work on simple drugs. It was translated into Syriac, Arabic, and Persian, as well as Latin and manually copied along with the botanical illustrations. It served as a corner stone for both western and eastern pharmaceutical and herbal knowledge, exerting a profound influence on the development of medicine in the Near East as well as in Europe. De Materia Medica of Dioscorides was closely and extensively studied by many medical writers and doctors of the Eastern and Western cultures. That is justified by the fact that the herbal remedies of Pedanius Dioscorides were transmitted to mediaeval Europe and the special characteristics of Arabic therapy was the widespread employment of drugs of all kinds (Yildirim, 2013). During the Middle Ages, the manual copies became more stylized and started to differ from the original botanical illustrations so, at the present time, the certainty about the accuracy of some species is diminished, hence the suggestions concerning the plant species described (Gaur et al., 2021). The information obtained by Dioscorides’ manuscript have undoubtedly influenced the traditional medical practices of the Balkans and the Mediterranean basin from the aspect of medicinal plants usage for the treatment of various skin diseases.

Background History of the Study Area

Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey have long-standing historical and cultural ties linked to their geographical position, constant presence of their communities in Eastern Mediterranean, trade, and population movements. They share relations since antiquity, however this review is focused on the development of distinct medicinal plants commonly used against various skin ailments from the time of Dioscorides (i.e., the Roman Empire), through the Byzantine and the Ottoman Empire, to modern era. After the fall of Roman Empire, Eastern Mediterranean region was under the control of Byzantium. During these centuries, medicinal plants’ therapeutic value was enriched by Arab herbal medicine, evolved, developed and preserved mainly through the transcription of herbals and codices by monks in monasteries (Isiksal, 2005; Azaizeh et al., 2006; Pan et al., 2014). The Ottoman Empire specifically at its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries CE, controlled not only southwestern Europe, mainland Greece, and the Balkans, but also parts of northern Iraq, Azerbaijan, Syria, Palestine, parts of the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, and parts of the North African strip, in addition to the major Mediterranean islands of Rhodes, Cyprus, and Crete (Khan, 2020). Under the Ottoman rule the populations coexisted and lived through their Byzantine heritage and were solidly influenced by each other regarding cultural issues including healing techniques and medicinal remedies. It is important to underline the interdependence of Cyprus, Albania, and Turkey with the Greek customs and traditions. In addition, the island of Cyprus was mainly part of the Byzantium, the Eastern Roman Empire. After the fall of Rome, the knowledge of Greek medicine survived in the Byzantium and during the times of the Ottoman Empire many Greek Orthodox monasteries featured well-organized hospitals of the Byzantine traditions. These hospitals employed pharmacists to gather medicinal plants and prepare remedies, originating from Greek folk medicinal practices (Littlewood et al., 2002). The only extensive manuscript of local origin in this respect, is “Iatrosophikon,” which is a monastic scripture from the Ottoman period that contains prescriptions written down by the monk Mitrophanous (1790–1867) at the Greek Orthodox monastery of Makhairas in Cyprus (Lardos, 2006). Another historical highlight related to the modern history of Greece and Albania that represents the base of the Greek-Albanian relationship is “Northern Epirus,” the status of the Greek minority in Albania (Dervishi, 2019). Northern Epirus is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, which today are part of Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek population in the region (Smith and Hurst, 1999). This population, which is present in the Albanian territory until nowadays, supports the interconnection of the two countries and continues the past cultural exchange. Moreover, during the 17th-19th centuries, Epirus became the most famous center of folk medicine in the Balkan Peninsula. In an environment of economic affluence accompanied by an impressive cultural and intellectual life, the art of herbal healing developed and flourished. The medicine practitioners of the area were called “Vikoyiatri” which means doctors that come from Vikos gorge, a mountainous area situated in Epirus (Vokou et al., 1993). During spring and summer, they used to travel all over the Balkans, up to Istanbul (Constantinople during the Byzantine times), Bulgaria, Romania, and Russia, while even the Sultan or other Turkish officers asked for their advice or help (Vokou et al., 1993). However, at the end of the 19th century with the introduction of “western drugs” in the pharmacopoeias they were considered as charlatans and their invaluable knowledge on herbal medicine faded away. The first official pharmacopoeia of the newly formed Greek state (1830) was written in Greek and Latin by Vouros I., Landerer X.J., and Sartori J. in 1837, and it was mainly a translation of the Bavarian one. Earlier efforts, including the General Pharmacopeia based on scripts of Dionysios Pyrros of Thessaly published in Istanbul by Brugnatelli in 1818, were not officially recognized. In 1831, Dionysios Pyrros published additionally a two-volume medical guide in which he described 450 medicines and 150 medicinal plants for the treatment of 362 ailments. Likewise, no recognition was made for the “Greek Pharmacopoeia” by Foteinos G., published in Ismir, Turkey, in 1835 (Karabelopoulos et al., 2004).

Methods

Some of the most important scientific databases such as Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google scholar were browsed to perform a literature search in order to identify all the published ethnobotanical field studies conducted in Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey (Figure 1) up until May 2020. The search was carried out by employing specific keywords or their combinations. The keywords used were “ethnobotanical,” “ethnobotany,” “ethnopharmacological,” “ethnopharmacology,” “ethnomedicinal,” and “ethnomedicine,” followed by the word “Balkans” or the name of each country studied. Only published field studies that included interviews with informants were considered, so published reviews such as the important work of Jarić et al. (2018) or the study of Iatrosofikon manuscript by Lardos (2006) were excluded from this review. Through the extensive literature search, data concerning 128 published ethnobotanical field studies were found and elaborated. Most of the studies (Paksoy et al., 2016) concerned traditional medicine in Turkey, 14 studies referred to Greece, 7 studies to Albania and 5 studies to Cyprus. The data relative to plant uses against skin disorders were manually retrieved from each study and recorded as multiple entries in an Excel file (.xlsx format). Afterwards, data for each species were merged in a single row with multiple columns including the botanical name, the vernacular name, the family, the country, and the region where the ethnobotanical study has been conducted, the plant part used, the preparation form with eventual details in case of a recipe and the ailments treated or the therapeutic effects. The skin diseases extracted from the publications were summarized and classified based on the terminology used in dermatology and grouped in 37 different categories (Table 1). In order to facilitate the data elaboration, plant subspecies were clustered with their corresponding species, when applicable. In addition, the botanical names of the plants reported were validated through the databases “The Plant List” (The Plant List [Internet], 2013) and “The Global Biodiversity Information Facility” (GBIF.org [Internet], 2020). If the original plant name from the references is a synonym of an accepted species, it is mentioned in parenthesis e.g., Centaurea cyanus L. (synonym of Cyanus segetum Hill), where Cyanus segetum Hill is the accepted species and Centaurea cyanus L. the synonym. Furthermore, synonyms of an accepted species, that was already reported in a study, are also mentioned in parenthesis, e.g., Allium ampeloprasum L. (= Allium porrum L.). Data curation and statistical analysis was performed in EXCEL.

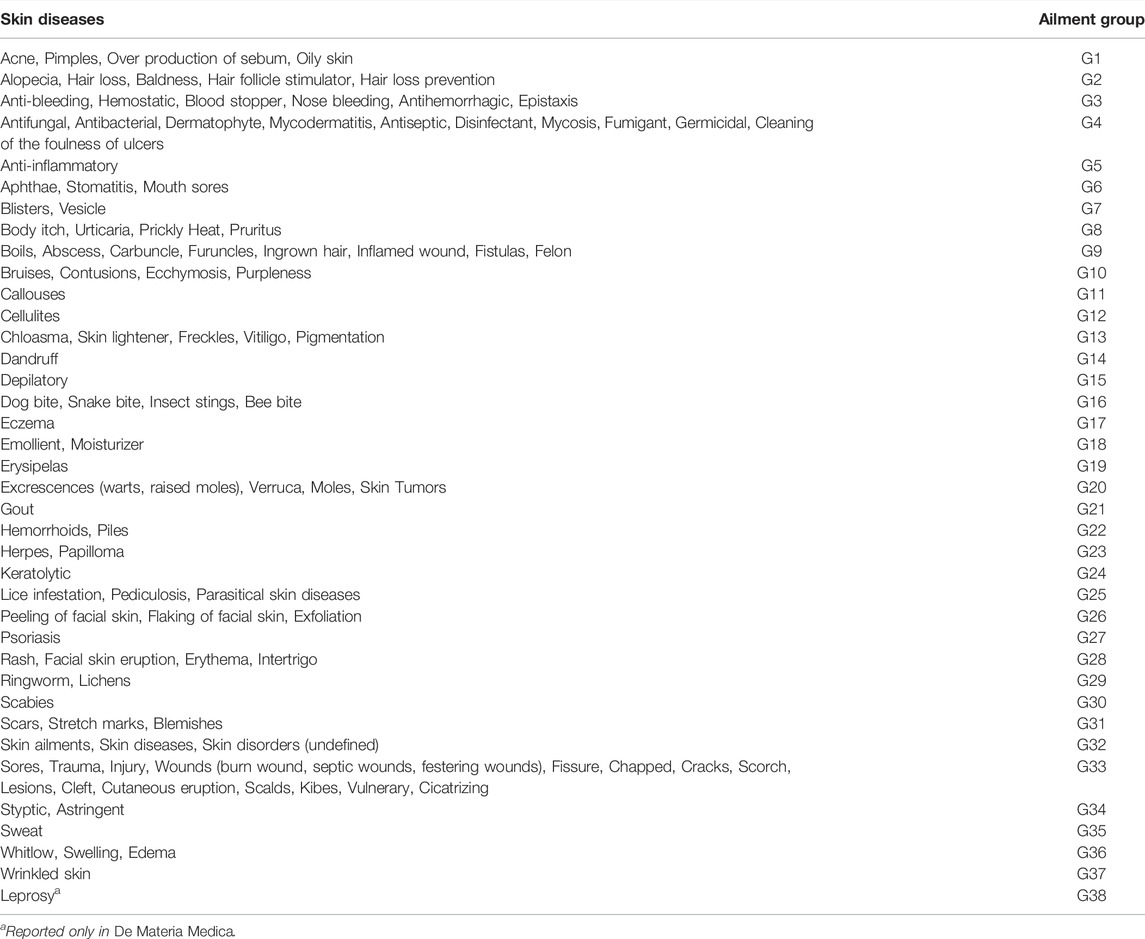

TABLE 1. Skin diseases extracted from literature data and grouped in 37 categories in alphabetical order.

Results and Discussion

Plant Species Reported in Ethnobotanical Research of the Study Area

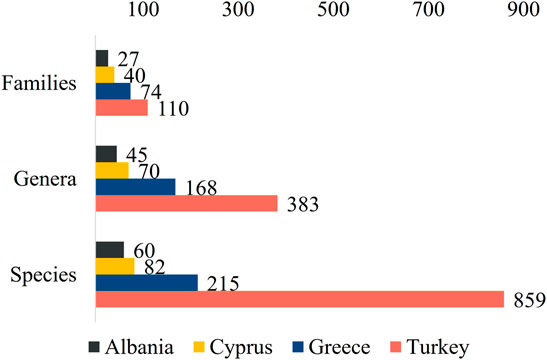

The bibliographical analysis indicated a total of 967 taxa belonging to 418 different genera and 111 different families that were used against skin related diseases. Specifically, 27 different families are reported in Albania, 40 in Cyprus, 74 in Greece, and 110 in Turkey (Figure 2).

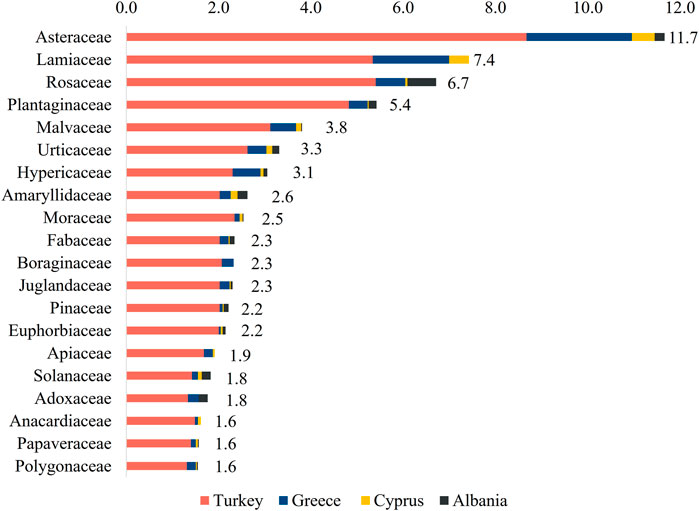

Out of 111 different families reported, the families mostly cited were Asteraceae (542 uses, 11.7%), Lamiaceae (345 uses, 7.4%), Rosaceae (312 uses, 6.7%), Plantaginaceae (252 uses, 5.4%), Malvaceae (177 uses, 3.8%), Urticaceae (154 uses, 3.3%), Hypericaceae (142 uses, 3.1%), Moraceae (118 uses, 2.5%), Fabaceae (109 uses, 2.3%), Boraginaceae (108 uses, 2.3%), Juglandaceae (107 uses, 2.3%), Pinaceae (103 uses, 2.2%), Euphorbiaceae (100 uses, 2.2%), Apiaceae (89 uses, 1.9%), Solanaceae (85 uses, 1.8%), Adoxaceae (82 uses, 1.8%), Anacardiaceae (75 uses, 1.6%), Papaveraceae (73 uses, 1.6%), and Polygonaceae (72 uses, 1.6%). The families Lamiaceae, Apiaceae, and Anacardiaceae were reported in three of the four countries (Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey), as well as Adoxaceae (Albania, Greece, and Turkey), Boraginaceae only in two countries (Greece and Turkey), while the rest are present in ethnobotanical studies conducted in all four countries (Figure 3).

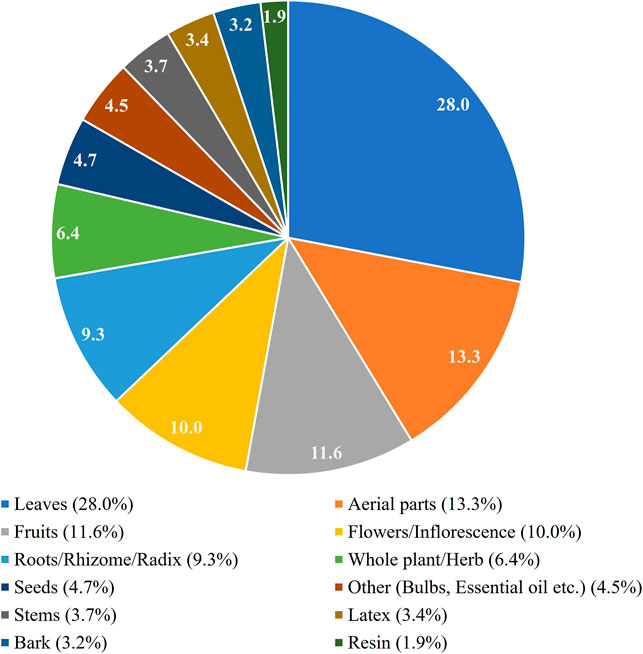

Many different ways of preparation were reported. The most cited ones were decoction or infusion, taken as a drink or used externally. Other methods reported were using plants to prepare a poultice, an ointment, a compress, or just using the plant externally. A total of 3,947 reports on plant parts were reported. The most cited plant parts used were the leaves (1105 reports , 28.0%), the aerial parts (525 reports, 13.1%), the fruits (457 reports, 11.6%), the flowers/inflorescence (396 reports, 10.0%), the roots/rhizome/radix (369 reports, 9.3%), the whole space plant/herb (252 reports, 6.4%), the seeds (184 reports, 4.7%),the stems (148 reports, 3.7%), the latex (133 reports, 3.4%), the bark (128 reports, 3.2%), and the resin (74 reports, 1.9%). Other parts used, including bulbs and essential oils had 176 reports (4.5%) (Figure 4.)

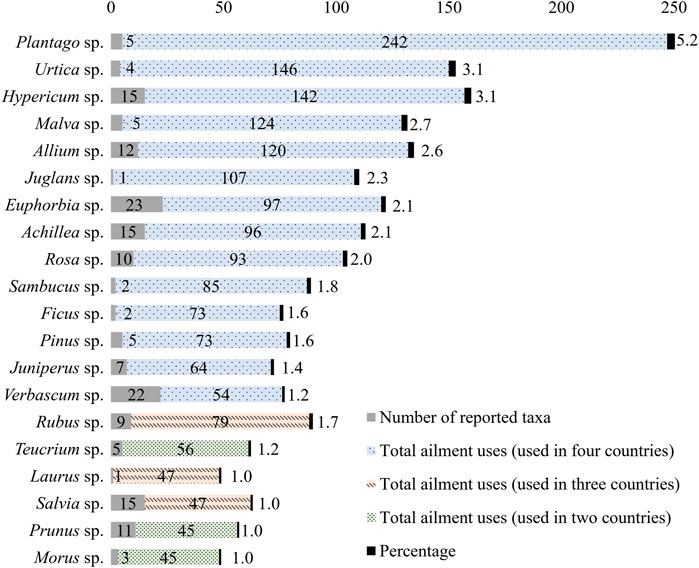

In Figure 5 the most cited genera in relation to their total use in skin related diseases are shown, along with the number of reported taxa of the same genus. These are Plantago L. sp. (5 taxa, 242 uses, 5.2%), Urtica L. sp. (4 taxa, 146 uses, 3.1%), Hypericum L. sp. (15 taxa, 142 uses, 3.1%), Malva L sp. (5 taxa, 124 uses, 2.7%), Allium L. sp. (12 taxa, 120 uses, 2.6%), Juglans L. sp. (1 taxon, 107 uses, 2.3%), Euphorbia sp. (23 taxa, 97 uses, 2.1%), Achillea L. sp. (15 taxa, 96 uses, 2.1%), Rosa L. sp. (10 taxa, 93 uses, 2.0%), Sambucus sp. (2 taxa, 85 uses, 1.8%), Ficus L. sp. (2 taxa, 73 uses, 1.6%), Pinus L. sp. (5 taxa, 73 uses, 1.6%), Juniperus L. sp. (7 taxa, 64 uses, 1.4%), Verbascum L. sp. (22 taxa, 54 uses, 1.2%), Rubus L sp. (9 taxa, 79 uses, 1.7%), Teucrium L. sp. (5 taxa, 56 uses, 1.2%), Laurus L. sp. (1 taxon, 47 uses, 1.0%), Salvia L. sp. (15 taxa, 47 uses, 1.0%), Prunus L. sp. (11 taxa, 45 uses, 1.0%), and Morus L. sp. (3 taxa, 45 uses, 1.0%). Genera Teucrium L. and Morus L. were reported in only two countries, Greece and Turkey, as well as Prunus L. sp. that was reported only in Albania and Turkey. Rubus L. sp. was reported in three of the countries (Albania, Greece, and Turkey), as well as Laurus L. sp. and Salvia L. sp. (Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey), while the rest were reported in ethnobotanical studies conducted in all four countries. Specifically, 45 different genera are reported in Albania, 70 in Cyprus, 168 in Greece, and 383 in Turkey.

The most cited plants species used for the treatment of skin ailments were Plantago major L. (140 uses, 3.0%), Juglans regia L. (107 uses, 2.3%), Urtica dioica L. (101 uses, 2.2%), Hypericum perforatum L. (81 uses, 1.7%), Plantago lanceolata L. (80 uses, 1.7%), Ficus carica L. (72 uses, 1.6%), Allium cepa L. (62 uses, 1.3%), Rosa canina L. (62 uses, 1.3%), Malva neglecta Wallr. (59 uses, 1.3%), Malva sylvestris L. (59 uses, 1.3%), Sambucus ebulus L. (48 uses, 1.0%), Laurus nobilis L. (47 uses, 1.0%), Juniperus oxycedrus L. (40 uses, 0.9%), Olea europaea L. (39 uses, 0.8%), Sambucus nigra L. (37 uses, 0.8%), Allium sativum L. (36 uses, 0.8%), Vitis vinifera L. (35 uses, 0.8%), Achillea millefolium L. (35 uses, 0.8%), Matricaria chamomilla L. (34 uses, 0.7%), and Rubus sanctus Schreb. (32 uses, 0.7%). It is important to underline that P. major, U. dioica, R. canina, and S. ebulus were reported in ethnobotanical studies in three of the four countries of the study area (Albania, Greece, and Turkey), as well as L. nobilis, and M. chamomilla (Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey). J. oxycedrus and R. sanctus were reported in ethnobotanical studies in two countries (Greece and Turkey), M. neglecta was reported only in Turkey, while the rest of the plants are used in all four countries (Figure 6).

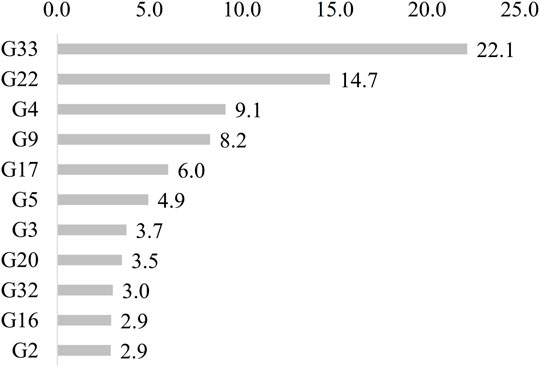

A total of 4,645 reports of skin related ailments were catalogued. The most cited categories identified in the studies were wounds etc. (G33, 1028 reports, 22.1%), hemorrhoids etc. (G22, 684 reports, 14.7%), antibacterial etc. (G4, 422 reports, 9.1%), boils etc. (G9, 383 reports, 8.2%), eczema (G17, 278 reports, 6.0%), anti-inflammatory (G5, 228 reports, 4.9%), antibleeding etc. (G3, 173 reports, 3.7%), excrescences etc. (G20, 162 reports, 3.5%), general skin ailments (G32, 139 reports, 3.0%), dog bites etc. (G16, 135 reports, 2.9%), and alopecia etc (G2, 134 reports, 2.9%) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Most cited ailment categories (G33 is Wounds etc., G22 is Hemorrhoids etc., G4 is Antibacterial etc., G9 is Boils etc., G17 is Eczema, G5 is Anti-inflammatory, G20 is Excrescences etc., G3 is Antibleeding etc., G32 is General skin ailments, and G16 is Dog bites etc.).

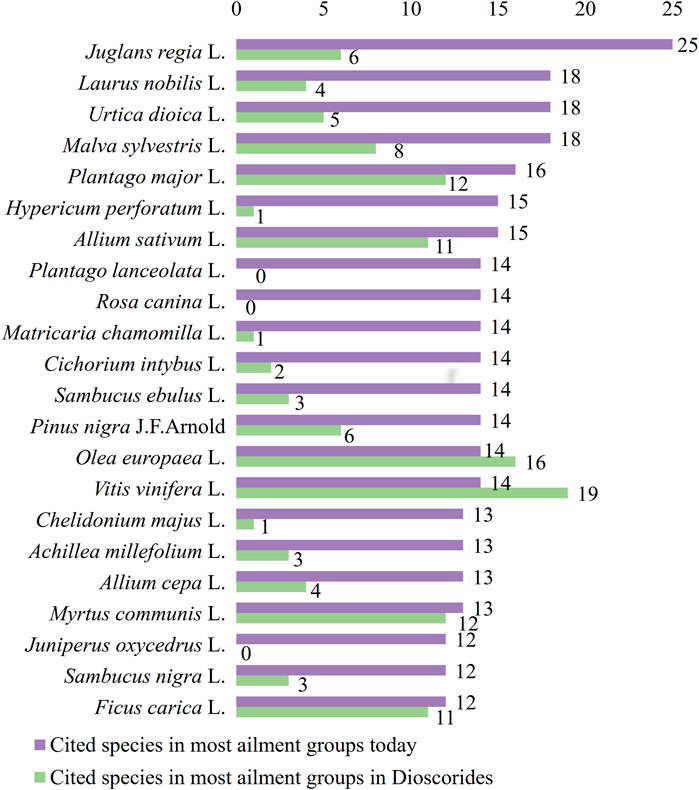

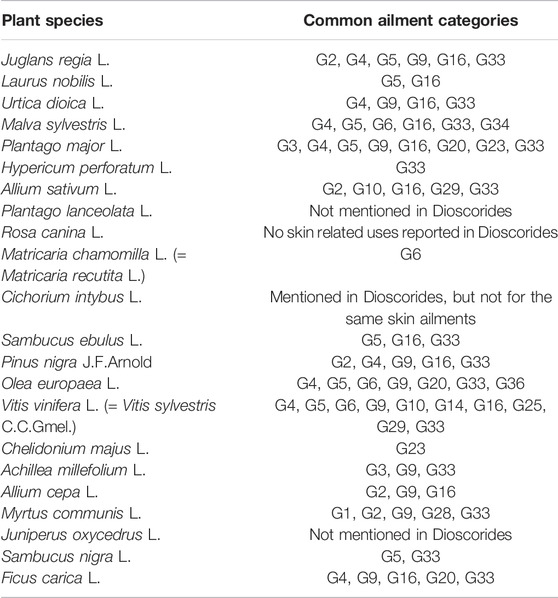

Finally, out of 37 different skin ailment groups, the plants used for the treatment of most of them were J. regia (25 different skin ailment groups), L. nobilis (18 groups), M. sylvestris (18 groups), U. dioica (18 groups), P. major (16 groups), A. sativum (15 groups), H. perforatum (15 groups), Cichorium intybus L. (14 groups), M. chamomilla (14groups), O. europaea (14 groups), P. nigra (14 groups), P. lanceolata (14 groups), R. canina (14 groups), S. ebulus (14 groups), V. vinifera (14 groups), A. millefolium (13 groups), A. cepa (13 groups), Chelidonium majus L. (13 groups), Myrtus communis L. (13 groups), F. carica (12 groups), J. oxycedrus (12 groups), and S. nigra (12 groups). Most of these plants comprise the most cited plants as well, with the exception of P. nigra which was reported only in Turkey, C. intybus which was reported in Greece and Turkey and H. perforatum and C. majus which were reported in ethnobotanical studies in all four countries (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Cited species in most ailment groups. Comparison between contemporary data and Dioscorides.

Plant Species Reported in Dioscorides “De Materia Medica”

The extensive study of Dioscorides’ manuscript, translated in English by Osbaldeston and Wood (Dioscorides et al., 2000) led to the discovery of 289 different entries in respect of treatments against skin related problems. Each entry contained suggested modern botanical names for the plants described by Dioscorides. The suggested plant names reported in each entry were validated by the databases and were eventually consolidated into 275 different entries, since several entries corresponded to the same plant species. The method of cataloguing each entry was performed in the same way as in the analysis of the field studies described above.

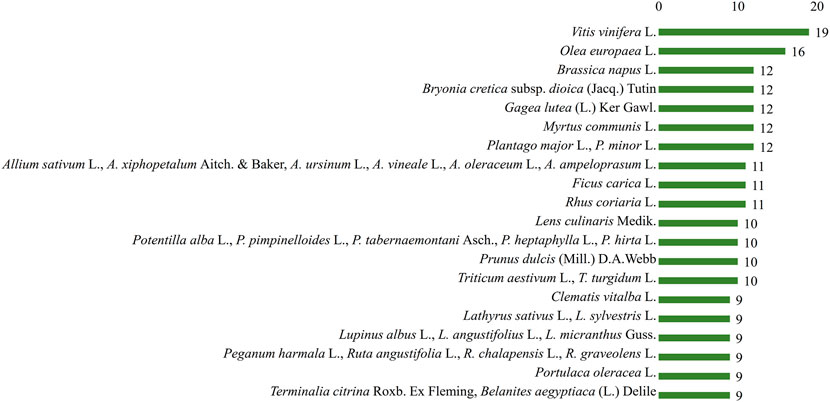

The suggested species with the highest number of reported uses among all the aliment categories (Figure 9) were V. vinifera L. (19 groups), O. europaea L. (16 groups), Brassica napus L. (12 groups), Bryonia cretica subsp. dioica (Jacq.) Tutin (12 groups), Gagea lutea (L.) Ker Gawl. (12 groups), M. communis L. (12 groups), P. major L., P. minor L.) (12 groups), A. sativum L., Allium xiphopetalum Aitch. & Baker, Allium ursinum L., Allium vineale L., Allium oleraceum L., Allium ampeloprasum L.) (11 groups), F. carica L. (11 groups), Rhus coriaria L. (11 groups), Lens culinaris Medik. (10 groups), Potentilla alba L., Potentilla pimpinelloides L., Potentilla tabernaemontani Asch., Potentilla heptaphylla L., Potentilla hirta L. (10 groups), Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A.Webb (10 groups), Triticum aesetivum L., Triticum turgidum L.) (10 groups), Clematis vitalba L. (9 groups), Lathyrus sativus L., Lathyrus sylvestris L. (9 groups), Lupinus albus L., Lupinus angustifolius L., Lupinus micranthus Guss. (9 groups), Peganum harmala L., Ruta angustifolia Pers., Ruta chalepensis L., Ruta graveolens L. (9 groups), Portulaca oleracea L. (9 groups), and Terminalia citrina Roxb. ex Fleming, Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (9 groups), while the preparation methods were similar to the ones used today.

The skin ailments described in De Materia Medica were also clustered in 37 different groups (Table 1), with the addition of the category “Leprosy” (G38), in order to obtain a better comparison with the skin ailment groups described in modern ethnobotanical field studies. The lack of data concerning Leprosy (G38) in the modern ethnobotanical studies can be attributed to the fact that leprosy greatly diminished in the study area around 1960 (Kyriakis et al., 1994; Lechat et al., 2002; Reibel et al., 2015).

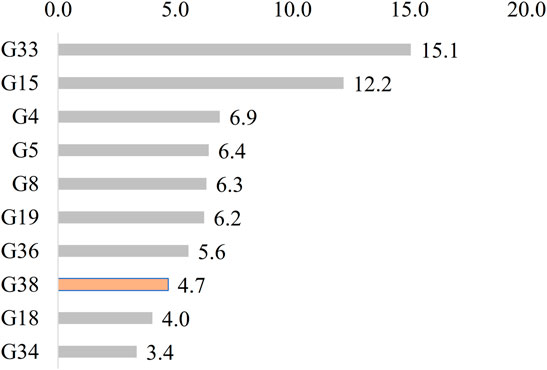

A total 1,042 reports were recorded. In Figure 10, the most cited ailment categories treated according to Dioscorides are shown. These are wounds etc. (G33, 157 reports 15.1%), dog bites etc. (G15, 127 reports, 12.2%), antibacterial etc. (G4, 72 reports, 6.9%), anti-inflammatory (G5, 67 reports, 6.4%), boils etc. (G8, 66 reports, 6.3%), excrescences etc. (G19, 65 reports, 6.2%), whitlow etc. (G36, 58 reports, 5.6%), leprosy (G38, 49 reports, 4.7%) which is highlighted in the chart, erysipelas (G18, 42 reports, 4.0%), and styptic (G34, 35 reports, 3.4%). Three groups, such as cellulites (G11), keratolysis (G23) and general skin ailments (undefined) (G32), are not mentioned in De Materia Medica.

FIGURE 10. Most cited ailment categories according to Dioscorides. Leprosy (G38) is only reported in Dioscorides.

It is important to mention that 19 of the 22 most reported plants used for the treatment of most of the skin ailment groups used in traditional medicine in the study area are also present in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica and employed for the treatment of some of these (Figure 8). These are J. regia L. (G2, G4, G5, G9, G16, and G33), L. nobilis L. (G5 and G16), U. dioica L. (G4, G9, G16, and G33), M. sylvestris L. (G4, G5, G6, G16, G33, and G34), P. major L. (G3, G4, G5, G9, G16, G20, G23, and G33), H. perforatum L. (G33), A. sativum L. (G2, G10, G16, G29, and G33), M. chamomilla L. (G6), S. ebulus L. (G5, G16, and G33), P. nigra J.F.Arnold (G2, G4, G9, G16, and G33), O. europaea L. (G4, G5, G6, G9, G20, G33, and G36), V. vinifera L. (G4, G5, G6, G9, G10, G14, G16, G25, G29, and G33), C. majus L. (G23), A. millefolium L. (G3, G9, and G33), A. cepa L. (G2, G9, and G16), M. communis L. (G1, G2, G9, G28, and G33), S. nigra L. (G5 and G33), and F. carica L. (G4, G9, G16, G20, and G33). Two plant species are not mentioned in the ancient manuscript (P. lanceolata L. and J. oxycedrus L.), one species (C. intybus L.) is mentioned but not for the same skin ailments, while one species (R. canina L.) is mentioned, but not for skin related diseases (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Species used in most ailment categories in the contemporary ethnobotanical studies which are also reported for the same uses in Dioscorides’ manuscript.

The results obtained during the extensive bibliographical analysis of the ethnobotanical field studies are presented in Table 3 in alphabetical order. Only 215 taxa used in traditional medicine in Greece are shown, along with their corresponding families. A comparison of the occurrence of these plants was also carried out between Greece, Albania, Cyprus, Turkey, and Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica. The number of their total uses against skin ailment categories in the study area was calculated.

TABLE 3. Taxa reported in Greek ethnobotanical field studies, cross-referenced with the other countries and De Materia Medica.

The percentage of common taxa reported between the ethnobotanical studies conducted in Greece and Albania is 14.4% (31 taxa), Greece and Cyprus is 22.8% (49 taxa), Greece and Turkey is 63.3% (136 taxa), while between Greece and those mentioned in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica is 48.8% (105 taxa). The percentage of common taxa reported between the ethnobotanical studies conducted in Greece and those conducted in Albania and Cyprus is low, even though they are countries with high historical and cultural connections, as aforementioned. This can be justified considering that since not many ethnobotanical studies have been carried out in Albania (7 studies) and Cyprus (5 studies), many plants have not yet been recorded, even though they may be used for the treatment of skin diseases nowadays. This conclusion can be strengthened by the fact that only 29 and 40 different families including 60 and 82 different taxa respectively have been reported in these two countries up to now.

On the other hand, even though the number of ethnobotanical studies conducted in Turkey (103 studies with 859 different taxa) is vastly higher than those conducted in Greece (13 studies with 215 different taxa), the percentage of common taxa reported is high. This could be due to geomorphological factors, floristic similarities, as well as historical and cultural reasons. Turkey is part of the continent of Asia and Europe, while Greece represents the tip of a peninsula appertaining to the continent of Europe. Greece, in spite of its small territory, has the richest flora in Europe, in terms of plant biodiversity per area unit and one of the richest worldwide. The wide geological history, the presence of different rock substrates (limestones, schists, and granite serpentine) and the complicated topography represent some of the factors that contribute to the floristic variety and diversity (Strid, 1986). The Greek flora consists of at least 6.700 species and subspecies and over 22% are endemic (Dimopoulos et al., 2016). Turkey, on the other hand, extends through a vast geographical area including coastal landmarks (Mediterranean and Black sea), dessert plains, lakes and highlands with mountain steppes (Kuzucuoğlu et al., 2019). A considerable number of the Greek mountain plants are also found in Turkey, while taxa restricted to the Balkan Peninsula and Anatolia constitute between 12 and 22% of the narrowly distributed taxa or between 4 and 9% of the total mountain flora of Greece. The Anatolian element is mostly represented in the North East and in Crete (22 and 21% of the “narrows” respectively) and is significantly smaller in the Pindhos and North Central (12%–14%). The percentage of “Turkish” species in the Greek mountain flora is thus roughly three times as high as the percentage of “Greek” species in the Turkish mountain flora. The migratory pressure from east to west is much greater than that from west to east (Strid, 1986). Moreover, inhabitants of the European part, as well as those of the Mediterranean coastline of Turkey have been in constant contact with people from the Balkans through trade and in relation to many historical facts. As such, there has been a reciprocal influence throughout the ages concerning traditional medicine and other cultural and social traditions. Inhabitants of East- and Southeastern Anatolia on the other hand were mostly influenced, both commercially and culturally, by Asian populations due to the constant flow of trade along the Silk Roads (MA, 2014). Since ethnobotanical studies included Turkish populations deriving from the whole Turkish domain, both European and Asian, it is somewhat expected that traditional medicine of Turkey is comprised by a blend of all these elements and cultures. Despite the different territorial size between Turkey and Greece, the floristic, historical, and cultural correlation lead to an important common number of species present in the ethnobotanical studies conducted in both countries.

Concerning the comparison between taxa reported in the ethnobotanical studies conducted in Greece and the suggested plants regarding the treatment of skin ailments reported in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, the percentage of common ones is 50%. Out of 215 different taxa reported in Greek ethnobotanical filed studies, 105 taxa were common, whereas 105 were not mentioned in De Materia Medica, yet 36 are only mentioned as genera. Moreover, 5 species occurring in the Greek studies are mentioned in the ancient manuscript but are not reported for skin related ailments. Furthermore, Greek traditional medicine, as well as other social and cultural aspects have been influenced by many different peoples, not only through commercial trade, but also due to occupation. From Byzantium to Francs and the Ottoman Empire, there has been a blending of all these different traditions and cultures through centuries. Additionally, Dioscorides refers to treatments against many skin ailments also present today, creating a strong bond between the past and the present. The comparison between the information obtained through the bibliographical analysis of the ethnobotanical research and Dioscorides’ manuscript, led to the conclusion that many of the remedies recommended against skin diseases in De Materia Medica, are also used as herbal therapies in the four countries for the treatment of the same skin conditions (Dioscorides et al., 2000) (Table 3). However, the data of this comparison will change over time, since few ethnobotanical studies have been carried out in the four countries on the topic up to now. The limited number of surveys should raise concern because many Greek populations, especially in remote areas, still possess this vital knowledge. Although their experience has not been recorded, it is transmitted through generations orally.

Conclusion

In the present review, an extensive literature search was performed concerning published ethnobotanical field studies conducted in Albania, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey up until May 2020, collecting data from 128 published articles concerning skin related ailments. This documentation can significantly contribute to the preservation of the ethnobotanical knowledge of the study area, since it is the first time that such a data collection was catalogued and statistically elaborated. Our findings suggest that traditional medicine plays an important role in the culture of Albanians, Cypriots, Greeks, and Turks and that the four populations, related historically and culturally, are demonstrated to have a common background on the use of medicinal plants against various skin diseases. The analysis showed that there is a substantial necessity to carry out more ethnobotanical field studies in this area but also in other countries of the Balkan Peninsula and the Mediterranean Sea to reveal more medical practices and treatment remedies not yet encountered. Moreover, the extended study of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica verifies the consensus that ancient herbals and their manuscripts have influenced and guided the development of Mediterranean and European traditional herbal medicine. This is confirmed by the number of species commonly mentioned and used in both ethnopharmacological surveys and Dioscorides’ plant descriptions. As a result, this can give rise to delving into other important herbal manuscripts enabling them as sources of evidence deriving from the past, and to evaluate the traditional medical practices described, not only against skin disorders, but also for the treatment of other ailments.

Author Contributions

AC, ZS, and NA contributed to the study conception and design. ET, VA, ED, and AV collected the information from the ethnobotanical studies and ancient manuscript. Data preparation and analyses were performed by ET and VA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ET, VA, and AC and all authors commented on different versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. NA collected the publication fee.

Funding

This research has been funded under the European H2020-MSCA-RISE-2018 (ID 823973) project “EthnoHERBS- Conservation of European Biodiversity through Exploitation of Traditional Herbal Knowledge for the Development of Innovative Products.”

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamidou, C. The Herbal Market of Xanthi ( Greece ): An Ethnobotanical Survey. Aristotle University Of Thessaloniki; 2012.

Adams, M., Alther, W., Kessler, M., Kluge, M., and Hamburger, M. (2011). Malaria in the Renaissance: Remedies from European Herbals from the 16th and 17th Century. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133 (2), 278–288. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.060

Ahmet Sargin, S. (2015). Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Bozyazı District of Mersin, Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 173, 105–126. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.009

Akaydin, G., Şimşek, I., Arituluk, Z. C., and Yeşilada, E. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Survey in Selected Towns of the Mediterranean Subregion (Turkey). Turk. J. Biol. 37 (2), 230–247. doi:10.3906/biy-1010-139

Akbulut, S., Karakose, M., and Özkan, Z. C. (2019). Traditional Uses of Some Wild Plants in Kale and Acıpayam Provinces in Denizli. Kastamonu Üniversitesi Orman. Fakültesi Derg., 72–81. doi:10.17475/kastorman.543529

Akgül, G., Yılmaz, N., Celep, A., Celep, F., and Çakılcıoǧlu, U. (2016). Ethnobotanical Purposes of Plants Sold by Herbalists and Folk Bazaars in the Center of Cappadocica (Nevşehir, Turkey). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 15 (1), 103–108.

Akyol, Y., and Altan, Y. (2013). Ethnobotanical Studies in the Maldan Village (Province Manisa, Turkey). Marmara Pharm. J. 17 (1), 21–25. doi:10.12991/201317388

Altundag, E., and Ozturk, M. (2011). Ethnomedicinal Studies on the Plant Resources of East Anatolia, Turkey. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 19, 756–777. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.195

Anastasi, G., Capitani, S., Carnazza, M., Cinti, S., De Caro, R., Donato, R., et al. (2012). Trattato di Anatomia Umana, 15–17. Milano, Italy: Edi-Ermes, 26.

Annotations [Internet] (2022). cybertaxonomy.org. 2022. Available from: https://portal.cybertaxonomy.org/flora-greece/annotations (cited May 27, 2022).1.

Ari, S., Temel, M., Kargioğlu, M., and Konuk, M. (2015). Ethnobotanical Survey of Plants Used in Afyonkarahisar-Turkey. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed 11 (84). doi:10.1186/s13002-015-0067-6

Axiotis, E., Halabalaki, M., and Skaltsounis, L. A. (2018). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in the Greek Islands of North Aegean Region. Front. Pharmacol. 9. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00409

Azaizeh, H., Saad, B., Khalil, K., and Said, O. (2006). The State of the Art of Traditional Arab Herbal Medicine in the Eastern Region of the Mediterranean: A Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 3 (2), 229–235. doi:10.1093/ecam/nel034

Barina, Z., and Pifkó, D. (2011). Contributions to the Flora of Albania, 2. Willdenowia 41 (1), 139–149. doi:10.3372/wi.41.41118

Brussell, D. E. (2004). Medicinal Plants of Mt. Pelion, Greece. Econ. Bot. 58, S174–S202. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2004)58[s174:mpompg]2.0.co;2

Buenz, E. J., Bauer, B. A., Osmundson, T. W., and Motley, T. J. (2005). The Traditional Chinese Medicine Cordyceps Sinensis and its Effects on Apoptotic Homeostasis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 96 (1–2), 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.029

Bulut, G., Doğan, A., Şenkardeş, İ., Avci, R., and Tuzlaci, E. (2019). The Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of Batman City and Kozluk District (Batman-Turkey). Agric. Conspec. Sci. 84 (1), 29–36.

Bulut, G., Haznedaroğlu, M. Z., Doğan, A., Koyu, H., and Tuzlacı, E. (2017). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Acipayam (Denizli-Turkey). J. Herb. Med., 64–81. 10(February 2016. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2017.08.001

Bulut, G. (2016). Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of Marmara Island (Balikesir - Turkey). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 85 (2). doi:10.5586/asbp.3501

Bulut, G., and Tuzlacı, E. (2015). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Bayramiç (Çanakkale- Turkey) Gizem. Marmara Pharm. J. 19, 268–282. doi:10.12991/mpj.201519392830

Bulut, G., and Tuzlaci, E. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Turgutlu (Manisa-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 149 (3), 633–647. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.07.016

Bulut, G., Bozkurt, M. Z., and Tuzlacı, E. (2017). The Preliminary Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Uşak (Turkey). Marmara Pharm. J. 21 (2), 305. doi:10.12991/marupj.300795

Cakilcioglu, U., Khatun, S., Turkoglu, I., and Hayta, S. (2011). Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Maden (Elazig-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 137 (1), 469–486. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.046

Çakilcioǧlu, U., Şengün, M. T., and Türkoǧlu, I. (2010). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants of Yazıkonak and Yurtbaşı Districts of Elaziǧ Province, Turkey. J. Med. Plants Res. 4 (7), 567–572.

Cakilcioglu, U., and Turkoglu, I. (2010). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Sivrice (Elazığ-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 132, 165–175. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.017

Cakilcioglu, U., Turkoglu, I., and Kürşat, M. (2007). Ethnobotanical Features of Harput (Elazig) and its Vicinity. Doğu Anadolu Bölgesi Araştırmaları 22–8.

Çakilcioǧlu, U., and Türkoğlu, İ. (2009). Plants Used for Hemorrhoid Treatment in Elaziǧ Central District. Acta Hortic. 826, 89–96. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2009.826.11

Charalampidou, C. Ethnobotany Research in the Prefecture of Kilkis. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; 2014.

Çolak, A. H., and Rotherham, I. D. (2006). A Review of the Forest Vegetation of Turkey: Its Status Past and Present and its Future Conservation. Biol. Environ. 106B (3), 343–354. doi:10.1353/bae.2006.0033

Dal Cero, M., Saller, R., and Weckerle, C. S. (2014). The Use of the Local Flora in Switzerland: A Comparison of Past and Recent Medicinal Plant Knowledge. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151 (1), 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.035

Dalar, A., Mukemre, M., Unal, M., and Ozgokce, F. (2018). Traditional Medicinal Plants of Ağrı Province, Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 226, 56–72. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2018.08.004

Demirci, S., and Özhatay, N. (2012). An Ethnobotanical Study in Kahramanmaras (Turkey); Wild Plants Used for Medicinal Purpose in Andirin. Kahramanmaraş. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 9 (1), 75–92.

Dervishi, G. (2019). Greek-Albanian Relations, the Past, the Present and the Future. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 10 (3), 24–35. doi:10.2478/mjss-2019-0038

Dimopoulos, P., Raus, T., Bergmeier, E., Constantinidis, T., Iatrou, G., Kokkini, S., et al. (2016). Vascular Plants of Greece: An Annotated Checklist. Supplement. Willdenowia 46 (3), 301–347. doi:10.3372/wi.46.46303

Dioscorides, P., Osbaldeston, T. A., and Wood, R. P. (2000). De Materia Medica : Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials Written in Greek in the First Century of the Common Era. Johannesburg: Ibidis.

Ecevit Genç, G., and Özhatay, N. (2006). An Ethnobotanical Study in Çatalca (European Part of Istanbul) II. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 3 (2), 73–89.

Emre, G., Dogan, A., Haznedaroglu, M. Z., Senkardes, I., Ulger, M., Satiroglu, A., et al. (2021). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Mersin (Turkey). Front. Pharmacol. 12, 664500. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.664500

Ertuǧ, F. (2000). An Ethnobotanical Study in Central Anatolia (Turkey). Econ. Bot. 54 (2), 155–182. doi:10.1007/bf02907820

Everest, A., and Ozturk, E. (2005). Focusing on the Ethnobotanical Uses of Plants in Mersin and Adana Provinces (Turkey). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed 1, 6. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-1-6

Ezer, N., and Mumcu Arisan, Ö. (2006). Folk Medicines in Merzifon (Amasya, Turkey). Turk J. Bot. 30 (3), 223–230.

Fady, B., and Conord, C. (2010). Macroecological Patterns of Species and Genetic Diversity in Vascular Plants of the Mediterranean Basin. Divers Distrib. 16 (1), 53–64. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00621.x

Fujita, T., Sezik, E., Tabata, M., Yesilada, E., Honda, G., Takeda, Y., et al. (1995). Traditional Medicine in Turkey VII. Folk Medicine in Middle and West Black Sea Regions. Econ. Bot. 49 (4), 406–422. doi:10.1007/bf02863092

Gaur, A., Augustyn, A., Zeidan, A., Batra, A., Zelazko, A., Eldridge, A., et al. Encyclopedia Brittanica. herbal [Internet]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/herbal (cited Jan 19, 2021).1.

GBIF.org [Internet] (2020). Available from: www.gbif.org/.

Gertsch, J. (2011). Botanical Drugs, Synergy, and Network Pharmacology: Forth and Back to Intelligent Mixtures. Planta Med. 77 (11), 1086–1098. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1270904

González-Tejero, M. R., Casares-Porcel, M., Sánchez-Rojas, C. P., Ramiro-Gutiérrez, J. M., Molero-Mesa, J., Pieroni, A., et al. (2008). Medicinal Plants in the Mediterranean Area: Synthesis of the Results of the Project Rubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 116, 341–357. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.045

Gözüm, S., and Ünsal, A. (2004). Use of Herbal Therapies by Older, Community-Dwelling Women. J. Adv. Nurs. 46 (2), 171–178. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02970.x

Güler, B., Erkan, Y., and Uğurlu, E. (2020). Traditional Uses and Ecological Resemblance of Medicinal Plants in Two Districts of the Western Aegean Region (Turkey). Environ. Dev. Sustain 22 (3), 2099–2120. doi:10.1007/s10668-018-0279-8

Güler, B., Kümüştekin, G., and Uğurlu, E. (2015). Contribution to the Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants of Turgutlu (Manisa--Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 176, 102–108. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.023

Güler, B., Manav, E., and Uğurlu, E. (2015). Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Bozüyük (Bilecik-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 173, 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.007

Günbatan, T., Gürbüz, İ., and Gençler Özkan, A. M. (2016). The Current Status of Ethnopharmacobotanical Knowledgein Çamlıdere (Ankara, Turkey)*. Turk J. Bot. 40 (3), 241–249. doi:10.3906/bot-1501-37

Güneş, S., Savran, A., Paksoy, M. Y., Koşar, M., and Çakılcıoğlu, U. (2017). Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Karaisalı and its Surrounding (Adana-Turkey). J. Herb. Med., 68–75.

Gunther, T. R. (1968). The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides. London, New York: Hafner Publising Company, 271–272.

Gürbüz, İ., Gençler Özkan, A. M., Akaydin, G., Salihoğlu, E., Günbatan, T., Demirci, F., et al. (2019). Folk Medicine in Düzce Province (Turkey). Turk J. Bot. 43, 769–784. doi:10.3906/bot-1905-13

Gürdal, B., and Kültür, S. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Marmaris (Muğla, Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 146 (1), 113–126. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.012

Gurib-Fakim, A. (2006). Medicinal Plants: Traditions of Yesterday and Drugs of Tomorrow. Mol. Asp. Med. 27 (1), 1–93. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.008

Güzel, Y., Güzelşemme, M., and Miski, M. (2015). Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used in Antakya: A Multicultural District in Hatay Province of Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 174, 118–152. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.042

Hadjichambis, A., Della, A., and Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D. (2004). Flora of the Sand Dune Ecosystems of Cyprus. Proc. 10th MEDECOS Conf., 1–7.

Han, M. İ., and Bulut, G. (2015). The Folk-Medicinal Plants of Kadişehri (Yozgat - Turkey). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 84 (2), 237–248. doi:10.5586/asbp.2015.021

Hanlidou, E., Karousou, R., Kleftoyanni, V., and Kokkini, S. (2004). The Herbal Market of Thessaloniki (N Greece) and its Relation to the Ethnobotanical Tradition. J. Ethnopharmacol. 91, 281–299. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.007

Hayta, S., Polat, R., and Selvi, S. (2014). Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants in Elazığ (Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 154 (3), 613–623. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.026

Hoffmann, J., Gendrisch, F., Schempp, C. M., and Wölfle, U. (2020). New Herbal Biomedicines for the Topical Treatment of Dermatological Disorders. Biomedicines 8 (2). doi:10.3390/biomedicines8020027

Honda, G., Yeşilada, E., Tabata, M., Sezik, E., Fujita, T., Takeda, Y., et al. (1996). Traditional Medicine in Turkey. VI. Folk Medicine in West Anatolia: Afyon, Kütahya, Denizli, Muğla, Aydin Provinces. J. Ethnopharmacol. 53 (2), 75–87. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01426-2

Isiksal, H. (2005). An Analysis of the Turkish-Greek Relations from Greek ‘Self’ and Turkish ‘Other’ Perspective: Causes of Antagonism and Preconditions for Better Relationships. Altern. Turk. J. Int. Relat. 1 (3).

Jarić, S., Kostić, O., Mataruga, Z., Pavlović, D., Pavlović, M., Mitrović, M., et al. (2018). Traditional Wound-Healing Plants Used in the Balkan Region (Southeast Europe). J. Ethnopharmacol. 211 (June 2017), 311–328. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.09.018

Kalankan, G., Özkan, Z. C., and Akbulut, S. (2015). Medicinal and Aromatic Wild Plants and Traditional Usage of Them in Mount Ida (Balikesir/Turkey). J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 9 (3), 25–33.

Karabelopoulos, D., and Oeconomopoulou, A. (2004). “Greek Medical Manuscripts of the Period of 16th -middle 19th Centuries,” in Proceedings of the 39th International Congress on the History of Medicine. Editor A. Musago-Soma (Bari, 140–145.

Karakaya, S., Polat, A., Aksakal, Ö., Sümbüllü, Y. Z., and İncekara, Ü. (2019). An Ethnobotanical Investigation on Medicinal Plants in South of Erzurum (Turkey). Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 18, 1–13. doi:10.32859/era.18.13.1-18

Karakaya, S., Polat, A., Aksakal, Ö., Sümbüllü, Y. Z., and Incekara, Ü. (2020). Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Aziziye District (Erzurum, Turkey). Turk J. Pharm. Sci. 17 (2), 211–220. doi:10.4274/tjps.galenos.2019.24392

Karaköse, M., Akbulut, S., and Özkan, Z. C. (2019). Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Torul District, Turkey. Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 26 (1), 29–37. doi:10.3329/bjpt.v26i1.41914

Karaman, S., and Kocabas, Y. Z. (2001). Traditional Medicinal Plants of K. Maras (Turkey). J. Med. Sci. 1 (3), 125–128. doi:10.3923/jms.2001.125.128

Karcı, E., Gürbüz, İ., Akaydın, G., and Günbatan, T. (2017). Folk Medicines of Bafra (Samsun-Turkey). Turk. J. Biochem. 42 (4), 381–399. doi:10.1515/tjb-2017-0172

Kargioǧlu, M., Cenkci, S., Serteser, A., Evliyaoǧlu, N., Konuk, M., Kök, M. Ş., et al. (2008). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Inner-West Anatolia, Turkey. Hum. Ecol. 36 (5), 763–777. doi:10.1007/s10745-008-9198-x

Kargıoğlu, M., Cenkci, S., Serteser, A., Konuk, M., and Vural, G. (2010). Traditional Uses of Wild Plants in the Middle Aegean Region of Turkey. Hum. Ecol. 38 (3), 429–450. doi:10.1007/s10745-010-9318-2

Karousou, R., and Deirmentzoglou, S. (2011). The Herbal Market of Cyprus: Traditional Links and Cultural Exchanges. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133, 191–203. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.09.034

Kaval, I., Behçet, L., and Cakilcioglu, U. (2014). Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants in Geçitli and its Surrounding (Hakkari-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 155 (1), 171–184. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.014

Khan, S. M. (2020). World History Encyclopedia. Ottoman Empire [Internet]. Available from: https://www.worldhistory.org/Ottoman_Empire/(cited Jan 20, 2021).1.

Kizilarslan, Ç., and Özhatay, N. (2012). An Ethnobotanical Study of the Useful and Edible Plants of İzmit. Marmara Pharm. J. 16 (3), 134–140. doi:10.12991/201216398

Korkmaz, M., Karakuş, S., Özçelik, H., and Selvi, S. (2016). An Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants in Erzincan, Turkey. Indian J. Traditional Knowl. 15, 192–202.

Korkmaz, M., Karakuş, S., Selvi, S., and Çakılcıoğlu, U. (2016). Traditional Knowledge on Wild Plants in Üzümlü (Erzincan-Turkey). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 15 (4), 538–545.

Korkmaz, M., and Si̇, Karakuş. (2015). Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants of Üzümlü District, Erzincan, Turkey. Pak. J. Bot. 47 (1), 125–134.

Kültür, S. (2007). Medicinal Plants Used in Kirklareli Province (Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 111, 341–364. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.035

Kuzucuoğlu, C., Çiner, A., and Kazancı, N. (2019). “The Geomorphological Regions of Turkey,” in Landscapes and Landforms of Turkey [Internet]. Editors C. Kuzucuoğlu, A. Çiner, and N. Kazancı (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 41–178. Available from. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03515-0_4

Kyriakis, K. P., Kontochristopoulos, G. J., and Panteleos, D. N. (1994). Current Profile of Active Leprosy in Greece; A Five-Year Retrospective Study (1988-1992). Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 62 (4), 547–551.

Lardos, A., and Heinrich, M. (2013). Continuity and Change in Medicinal Plant Use: The Example of Monasteries on Cyprus and Historical Iatrosophia Texts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 150, 202–214. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.026

Lardos, A. (2006). The Botanical Materia Medica of the Iatrosophikon-Aa Collection of Prescriptions from a Monastery in Cyprus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 104, 387–406. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.035

Lechat, M. F., Work- E, , Foundation, H., Honorable, G., Chandrashekhar, J., and Dongre, V. V. (2002). News and Notes: News and Notes. Addiction 97 (2), 233–236. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00123.x

Leonti, M., Cabras, S., Weckerle, C. S., Solinas, M. N., and Casu, L. (2010). The Causal Dependence of Present Plant Knowledge on Herbals-Ccontemporary Medicinal Plant Use in Campania (Italy) Compared to Matthioli (1568). J. Ethnopharmacol. 130 (2), 379–391. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.021

Littlewood, A., Maguire, H., and Wolschke-Buhlmahn, J. (2002). in Byzantine Garden Culture. Littlewood A. Editors H. Maguire, and J. Wolschke-Buhlmahn (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 54–57.

Ma, L. (2014). Sino-Turkish Cultural Ties under the Framework of Silk Road Strategy. J. Middle East. Islamic Stud. (in Asia) 8 (2), 44–65. doi:10.1080/19370679.2014.12023242

Malamas, M., and Marselos, M. (1992). The Tradition of Medicinal Plants in Zagori, Epirus (Northwestern Greece). J Ethnopharmacol 37, 197–203. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(92)90034-o

Mphande, F. A. (2020). Skin Disorders in Vulnerable Populations. Causes, Impacts and Challenges, 3–15. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-3879-7

Mükemre, M., Behçet, L., and Çakılcıoğlu, U. (2015). Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants in Villages of Çatak (Van-Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 166, 361–374. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.040

Nadiroğlu, M., Behçet, L., and Çakılcıoğlu, U. (2019). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Karlıova (Bingöl-turkey). Indian J Tradit Knowl 18 (1), 76–87. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.017

Özdemir, E., and Alpınar, K. (2015). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Western Part of Central Taurus Mountains: Aladaglar (Nigde - Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 166, 53–65. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.052

Özgen, U., Kaya, Y., and Houghton, P. (2012). Folk Medicines in the Villages of Ilıca District (Erzurum, Turkey). Turkish J Biol 36 (1), 93–106. doi:10.3906/biy-1009-124

Özgökçe, F., and Özçelik, H. (2004). Ethnobotanical Aspects of Some Taxa in East Anatolia, Turkey. Economic Botany 58 (4), 697–704. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058[0697:eaosti]2.0.co;2

Özşahin, E., and Eroğlu, İ. (2019). “Spatiotemporal Change of Anthropogenic Biomes ( Anthromes ) of Turkey,” in Theory and Practice in Social Sciences. Editors V. Krystev, R. Efe, and E. Atasoy (SofiaSt: Kliment Ohridski University Press), 241–252.

Özüdoru, B., Akaydin, G., Erik, S., and Yesilada, E. (2011). Inferences from an Ethnobotanical Field Expedition in the Selected Locations of Sivas and Yozgat Provinces (Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 137 (1), 85–98. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.050

Paksoy, M. Y., Selvi, S., and Savran, A. (2016). Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Ulukışla (Niğde-Turkey). Journal of Herbal Medicine 6 (1), 42–48. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2015.04.003

Pan, S. Y., Litscher, G., Gao, S. H., Zhou, S. F., Yu, Z. L., Chen, H. Q., et al. (2014). Historical Perspective of Traditional Indigenous Medical Practices: The Current Renaissance and Conservation of Herbal Resources. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 525340. doi:10.1155/2014/525340

Papageorgiou, D., Bebeli, P. J., Panitsa, M., and Schunko, C. (2020). Local Knowledge about Sustainable Harvesting and Availability of Wild Medicinal Plant Species in Lemnos Island, Greece. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 16. doi:10.1186/s13002-020-00390-4

Petrakou, K., Iatrou, G., and Lamari, F. N. (2020). Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants Traded in Herbal Markets in the Peloponnisos, Greece. J Herb Med 19, 100305. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100305

Pieroni, A., Cianfaglione, K., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., and Quave, C. L. (2014). Resilience at the Border: Traditional Botanical Knowledge Among Macedonians and Albanians Living in Gollobordo, Eastern Albania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 10 (31), 31. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-10-31

Pieroni, A., Dibra, B., Grishaj, G., Grishaj, I., and Gjon Maçai, S. (2005). Traditional Phytotherapy of the Albanians of Lepushe, Northern Albanian Alps. Fitoterapia 76, 379–399. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2005.03.015

Pieroni, A., Giusti, M. E., de Pasquale, C., Lenzarini, C., Censorii, E., Gonzáles-Tejero, M., et al. (2006). Circum-Mediterranean Cultural Heritage and Medicinal Plant Uses in Traditional Animal Healthcare: A Field Survey in Eight Selected Areas within the RUBIA Project. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-2-16

Pieroni, A., Ibraliu, A., Abbasi, A. M., and Papajani-Toska, V. (2014). An Ethnobotanical Study Among Albanians and Aromanians Living in the Rraicë and Mokra Areas of Eastern Albania. Genet Resour Crop Evol 61 (224), 477–500. doi:10.1007/s10722-014-0174-6

Pieroni, A., Muenz, H., Akbulut, M., Başer, K. H., and Durmuşkahya, C. (2005). Traditional Phytotherapy and Trans-cultural Pharmacy Among Turkish Migrants Living in Cologne, Germany. J Ethnopharmacol 102 (1), 69–88. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.018

Pieroni, A., and Sõukand, R. (2017). The Disappearing Wild Food and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Few Mountain Villages of North-Eastern Albania. J Appl Bot Food Qual 90, 58–67. doi:10.5073/JABFQ.2017.090.009

Pieroni, A., and Cattero, V. (2019). Wild Vegetables Do Not Lie: Comparative Gastronomic Ethnobotany and Ethnolinguistics on the Greek Traces of the Mediterranean Diet of Southeastern Italy. Acta Bot. Bras. 33, 198–211. doi:10.1590/0102-33062018abb0323

Pieroni, A. (2008). Local Plant Resources in the Ethnobotany of Theth, a Village in the Northern Albanian Alps. Genet Resour Crop Evol 55, 1197–1214. doi:10.1007/s10722-008-9320-3

Pieroni, A., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., Scaltriti, B., Cianfaglione, K., et al. (2014). Local Knowledge on Plants and Domestic Remedies in the Mountain Villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). J. Mt. Sci. 11 (1), 180–193. doi:10.1007/s11629-013-2651-3

Pieroni, A. (2017). Traditional Uses of Wild Food Plants, Medicinal Plants, and Domestic Remedies in Albanian, Aromanian and Macedonian Villages in South-Eastern Albania. Journal of Herbal Medicine 9, 81–90. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2017.05.001

Polat, R., Cakilcioglu, U., Kaltalioğlu, K., Ulusan, M. D., and Türkmen, Z. (2015). An Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants in Espiye and its Surrounding (Giresun-Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 163, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.008

Polat, R., Cakilcioglu, U., and Satıl, F. (2013). Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants in Solhan (Bingöl-Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 148 (3), 951–963. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.050

Polat, R. (2019). Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants in Bingöl (City Center) (Turkey). J Herb Med 16. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2018.01.007

Polat, R., and Satıl, F. (2012). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Edremit Gulf (Balıkesir-Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 139 (2), 626–641. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004

Reibel, F., Cambau, E., and Aubry, A. (2015). Update on the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Leprosy. Med Mal Infect 45 (9), 383–393. Available from:. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2015.09.002

Rooney, A. (2012). The History of Medicine. New York, United States: The Rosen Publishing Group, 12.

Şanda, M. A., and Küçüködük, M. (2018). “Local Names, Ethnobotanical Features and Threatened Categories of Some Plants in Oyuklu Mountain (Kalaba, Ada and Ihsaniye Village-Karaman),” in International Conference On Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (Stem) And Eucational Sciences, 125–133.

Sargin, S. A., Akçicek, E., and Selvi, S. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by the Local People of Alaşehir (Manisa) in Turkey. J Ethnopharmacol 150 (3), 860–874. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.040

Sargin, S. A., and Büyükcengiz, M. (2019). Plants Used in Ethnomedicinal Practices in Gulnar District of Mersin, Turkey. J Herb Med 15. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2018.06.003

Sargin, S. A., Selvi, S., and Büyükcengiz, M. (2015). Ethnomedicinal Plants of Aydıncık District of Mersin, Turkey. J Ethnopharmacol 174, 200–216. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.008

Sargin, S. A., Selvi, S., and López, V. (2015). Ethnomedicinal Plants of Sarigöl District (Manisa), Turkey. J Ethnopharmacol 171, 64–84. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.031

Sarper, F., Akaydin, G., Şimşek, I., and Yeşilada, E. (2009). An Ethnobotanical Field Survey in the Haymana District of Ankara Province in Turkey. Turkish J Biol 33 (1), 79–88. doi:10.3906/biy-0808-28

Sekeroglu, N., Alpaslan Kaya, D., Inan, M., and Kirpik, M. (2006). Essential Oil Contents and Ethnopharmacological Characteristics of Some Spices and Herbal Drugs Traded in Turkey. International J. of Pharmacology 2 (2), 256–261. doi:10.3923/ijp.2006.256.261

Sezik, E., Tabata, M., Yeşilada, E., Honda, G., Goto, K., and Ikeshiro, Y. (1991). Traditional Medicine in Turkey. I. Folk Medicine in Northeast Anatolia. J Ethnopharmacol 35 (2), 191–196. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(91)90072-l

Sezik, E., Yeşilada, E., Honda, G., Takaishi, Y., Takeda, Y., and Tanaka, T. (2001). Traditional Medicine in Turkey X. Folk Medicine in Central Anatolia. J Ethnopharmacol 75 (2–3), 95–115. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00399-8

Sezik, E., Yeşİlada, E., Tabata, M., Honda, G., Takaishi, Y., Fujita, T., et al. (1997). Traditional Medicine in Turkey VIII. Folk Medicine in East Anatolia; Erzurum, Erzíncan, Ağri, Kars, Iğdir Provinces. Econ Bot 51 (3), 195–211. doi:10.1007/bf02862090

Sezik, E., Zor, M., and Yesilada, E. (1992). Traditional Medicine in Turkey II. Folk Medicine in Kastamonu. International Journal of Pharmacognosy 30 (3), 233–239. doi:10.3109/13880209209054005

Simsek, I., Aytekin, F., Yesilada, E., and Yildirimli, Ş. (2004). An Ethnobotanical Survey of the Beypazari, Ayas, and Güdül District Towns of Ankara Province (Turkey). Econ Bot 58 (4), 705–720. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058[0705:aesotb]2.0.co;2

Smith, M. L. (1999). in Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor. Editor C. Hurst. 2nd ed. (London: Hurst Publishers), 1919–1922. 36.

Staub, P. O., Casu, L., and Leonti, M. (2016). Back to the Roots: A Quantitative Survey of Herbal Drugs in Dioscorides' De Materia Medica (Ex Matthioli, 1568), Phytomedicine [Internet]. Phytomedicine 23 (10), 1043–1052. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2016.06.016

Strid, A. (1986). The Mountain Flora of Greece with Special Reference to the Anatolian Element. Proc., Sect. B Biol. sci. 89 (1986), 59–68. doi:10.1017/s0269727000008903

Tabassum, N., and Hamdani, M. (2014). Plants Used to Treat Skin Diseases. Pharmacogn Rev 8 (15), 52–60. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.125531

Tabata, M., Sezik, E., Honda, G., Yeşilada, E., Fukui, H., Goto, K., et al. (1994). Traditional Medicine in Turkey III. Folk Medicine in East Anatolia, Van and Bitlis Provinces. International Journal of Pharmacognosy 32 (1), 3–12. doi:10.3109/13880209409082966

Tetik, F., Civelek, S., and Cakilcioglu, U. (2013). Traditional Uses of Some Medicinal Plants in Malatya (Turkey). J Ethnopharmacol 146 (1), 331–346. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.054

The Plant List [Internet] (2013). Available from: http://www.theplantlist.org/.

Toksoy, D., Bayramoglu, M., and Hacisalihoglu, S. (2010). Usage and the Economic Potential of the Medicinal Plants in Eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey. J Environ Biol 31 (5), 623–628.

Touwaide, A. (1992). The Corpus of Greek Medical Manuscripts: A Computerized Inventory and Catalogue. Prim Sources Orig Work 1 (3–4), 75–92. doi:10.1300/j269v01n03_07

Tsioutsiou, E. E., Giordani, P., Hanlidou, E., Biagi, M., De Feo, V., and Cornara, L. (2019). Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used in Central Macedonia, Greece. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2019, 4513792. doi:10.1155/2019/4513792

Tsioutsiou, E. E., Miraldi, E., Governa, P., Biagi, M., Giordani, P., and Cornara, L. (2017). Skin Wound Healing: From Mediterranean Ethnobotany to Evidence Based Phytotherapy. Athens Journal of Sciences 4, 199–212. doi:10.30958/ajs.4-3-2

Tuzlaci, E., and Alparslan, D. F. (2007). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, Part V: Babaeski (Kirklareli). J Pharm Istanbul Univ 39, 11–23. doi:10.16883/JFPIU.92638

Tuzlacı, E., and Aymaz, P. E. (2001). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, Part IV: Gönen (Balikesir). Fitoterapia 72 (4), 323–343. doi:10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00277-x

Tuzlacı, E., and Bulut, G. E. (2007). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, Part VII: Ezine (Çanakkale). J Pharm Istanbul Univ., 39–51. doi:10.16883/JFPIU.37197

Tuzlacı, E., and Doğan, A. (2010). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, IX: Ovacık (Tunceli). Marmara Pharm J 14 (3), 136–143. doi:10.12991/201014449

Tuzlacı, E., and Erol, M. K. (1999). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants. Part II: Egirdir (Isparta). Fitoterapia 70 (6), 593–610. doi:10.1016/s0367-326x(99)00074-x

Tuzlacı, E., and Ii̇, Ş. (2011). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, X: Ürgüp (Nevüehir). Marmara Pharm J 15 (2), 58–68. doi:10.12991/201115432

Tuzlacı, E., and Sadıkoğlu, E. (2007). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants. Part VI: Koçarlı (Aydın). J Fac Pharm Istanbul, 25–37.

Tuzlaci, E., and Tolon, E. (2000). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, Part III: Sile (Istanbul). Fitoterapia 71 (6), 673–685. doi:10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00234-3

Tuzlaci, E., Alparslan Işbilen, D. F., and Bulut, G. (2010). Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, VIII: Lalapasa (Edirne). mpj 1, 47–52. doi:10.12991/201014463

Ugulu, I., Baslar, S., Yorek, N., and Dogan, Y. (2009). The Investigation and Quantitative Ethnobotanical Evaluation of Medicinal Plants Used Around Izmir Province, Turkey. J Med Plants Res 3 (5), 345–367.

Ugurlu, E., and Secmen, O. (2008). Medicinal Plants Popularly Used in the Villages of Yunt Mountain(Manisa-Turkey). Fitoterapia 79 (2), 126–131. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2007.07.016

Ünsal, Ç., Vural, H., Sariyar, G., Özbek, B., and Ötük, G. (2010). Traditional Medicine in Bilecik Province (Turkey) and Antimicrobial Activities of Selected Species. Turkish J Pharm Sci 7 (2), 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.07.013

Uysal, I., Gücel, S., Tütenocakli, T., and Öztürk, M. (2012). Studies on the Medicinal Plants of Ayvacik-Çanakkale in Turkey. Pakistan J Bot 44 (SPL.ISS.1), 239–244.

Uzun, E., Sariyar, G., Adsersen, A., Karakoc, B., Otük, G., Oktayoglu, E., et al. (2004). Traditional Medicine in Sakarya Province (Turkey) and Antimicrobial Activities of Selected Species. J Ethnopharmacol 95 (2–3), 287–296. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.07.013

Uzun, M., and Kaya, A. (2016). Ethnobotanical Research of Medicinal Plants in Mihalgazi (Eskişehir, Turkey). Pharm Biol 54 (12), 2922–2932. doi:10.1080/13880209.2016.1194863

Varga, F., Šolić, I., Dujaković, M. J., Łuczaj, Ł., and Grdiša, M. (2019). The First Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of the Knin Area, Croatia. Acta Soc Bot Pol 88 (2). doi:10.5586/asbp.3622

Vokou, D., Katradi, K., and Kokkini, S. (1993). Ethnobotanical Survey of Zagori (Epirus, Greece), a Renowned Centre of Folk Medicine in the Past. J Ethnopharmacol 39, 187–196. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(93)90035-4

Wong, R., Geyer, S., Weninger, W., Guimberteau, J. C., and Wong, J. K. (2016). The Dynamic Anatomy and Patterning of Skin. Exp Dermatol 25 (2), 92–98. doi:10.1111/exd.12832

Yeşilada, E., Honda, G., Sezik, E., Tabata, M., Fujita, T., Tanaka, T., et al. (1995). Traditional Medicine in Turkey. V. Folk Medicine in the Inner Taurus Mountains. J Ethnopharmacol 46 (3), 133–152. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01241-5

Yeşilada, E., Honda, G., Sezik, E., Tabata, M., Goto, K., and Ikeshiro, Y. (1993). Traditional Medicine in Turkey. IV. Folk Medicine in the Mediterranean Subdivision. J Ethnopharmacol 39 (1), 31–38. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(93)90048-a

Yeşilada, E., Sezik, E., Honda, G., Takaishi, Y., Takeda, Y., and Tanaka, T. (1999). Traditional Medicine in Turkey IX: Folk Medicine in North-West Anatolia. J Ethnopharmacol 64 (3), 195–210. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00133-0

Yeşilyurt, E. B., Şimşek, I., Akaydin, G., and Yeşilada, E. (2017). An Ethnobotanical Survey in Selected Districts of the Black Sea Region (Turkey). Turk J Botany 41 (1), 47–62. doi:10.3906/bot-1606-12

Yildirim, B., Terzioglu, Ö., Özgökçe, F., and Türközü, D. (2008). Ethnobotanical and Pharmacological Uses of Some Plants in the Districts of Karpuzalan and Adigüzel (Van-Turkey). J Anim Vet Adv 7 (7), 873–878.

Yildirim, R. V. (2013). Studies on De Materia Medica of Dioscorides in the Islamic Era. Asclepio 65 (1), 1–7. doi:10.3989/asclepio.2013.07

Keywords: ethnopharmacology, skin, balkan peninsula, mediterranean, dioscorides, dermatological ailments, wound healing, anti-inflammatory

Citation: Tsioutsiou EE, Amountzias V, Vontzalidou A, Dina E, Stevanović ZD, Cheilari A and Aligiannis N (2022) Medicinal Plants Used Traditionally for Skin Related Problems in the South Balkan and East Mediterranean Region—A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 13:936047. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.936047

Received: 04 May 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022;

Published: 05 July 2022.

Edited by:

Judith Maria Rollinger, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Songül Karakaya, Atatürk University, TurkeyCynthia A. Danquah, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

Copyright © 2022 Tsioutsiou, Amountzias, Vontzalidou, Dina, Stevanović, Cheilari and Aligiannis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antigoni Cheilari, Y2hlaWxhcmlhbnRpQHBoYXJtLnVvYS5ncg==

†These authors share first authorship

Efthymia Eleni Tsioutsiou

Efthymia Eleni Tsioutsiou Vaios Amountzias

Vaios Amountzias Argyro Vontzalidou1

Argyro Vontzalidou1 Zora Dajić Stevanović

Zora Dajić Stevanović Antigoni Cheilari

Antigoni Cheilari Nektarios Aligiannis

Nektarios Aligiannis