- 1Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Collaborative Antwerp Psychiatric Research Institute (CAPRI), University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 2Scientific Initiative of Neuropsychiatric and Psychopharmacological Studies (SINAPS), University Psychiatric Centre Duffel, Duffel, Belgium

- 3Laboratory of Medical Biochemistry, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Introduction

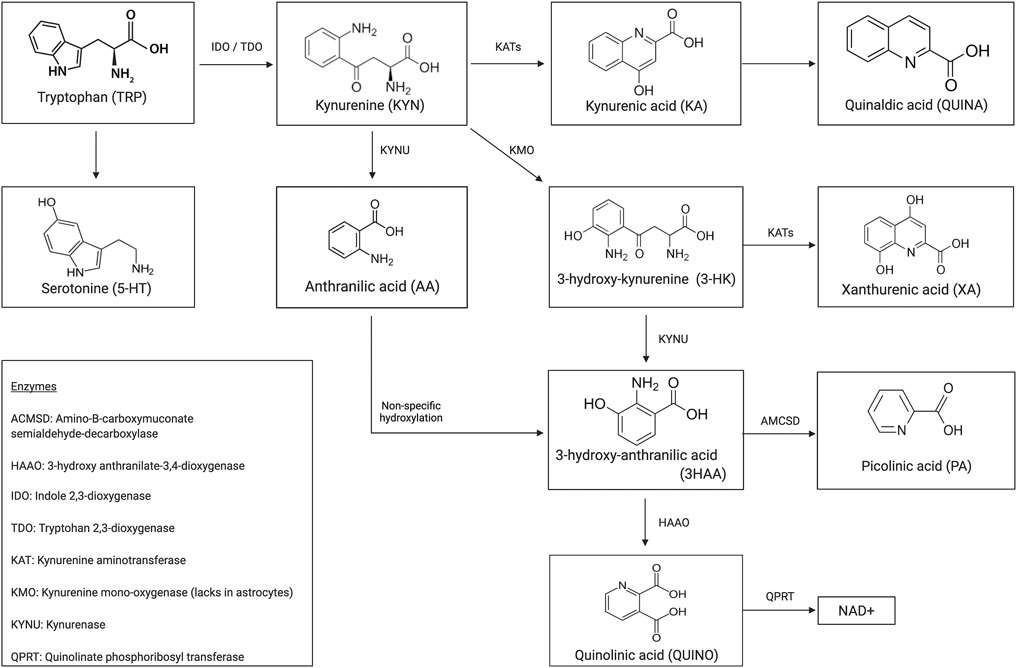

Immune dysregulation contributes extensively to the pathophysiology of multiple psychiatric illnesses (Coppens et al., 2019; Morrens et al., 2020a). Overall, 95% of the essential amino acid tryptophan (TRP) is degraded to kynurenine and either to its neurotoxic or neuroprotective immunogenic metabolites (see Figure 1 for a schematic illustration of the kynurenine pathway (KP)). A growing body of evidence testifies the neuromodulatory effects these microglia- or astrocyte-derived tryptophan catabolites (TRYCAT) have on the NMDA receptor. Hence, TRYCAT are hypothesized to link (systemic) immune responses to clinical symptomatology in psychotic and mood disorders.

A series of recent meta-analyses (Morrens et al., 2020b; Hebbrecht et al., 2021; Marx et al., 2021) confirm kynurenine pathway (KP) metabolite aberrances in these psychiatric illnesses in over 100 clinical studies. Unfortunately, the KP research field knows substantial though rarely contemplated pitfalls that warrant caution in the interpretation of findings. The current opinion piece will therefore zoom in on the conceptual validity of peripheral kynurenine metabolite quantification in psychiatric biomarker research. Furthermore, we will discuss the impact of sample heterogeneity, methodological reliability, and validity on study results. To conclude, the authors will put forward conceptual and methodological guidelines for future research into the kynurenine pathway and propositions for relevant future research avenues.

The Bloody Brain Barrier

The bulk of literature on TRYCAT in psychiatry concerns quantifying metabolite levels in peripheral blood as a proxy measure for central inflammatory processes. However, as summarized in a recent systematic review by Skorobogatov et al. (2021), only TRP and KYN and to some extent 3-HK fluently travel over the blood–brain barrier (BBB). It remains undefined whether peripheral production of non-crossing metabolites such as kynurenic acid (KA) and quinolinic acid (QUIN) could indirectly reflect central inflammatory processes, for instance, through induction by BBB-crossing macrophages or macrophage-secreted cytokines. Nonetheless, for the metabolites traveling to the periphery over the BBB, extrapolation of the significance of KYN metabolization remains cumbersome. Illustratively, Skorobogatov et al. (2021) describe a strong correlation between peripheral and central KYN concentrations in two studies (Yuwiler et al., 1977; Haroon et al., 2020), while such interrelations remain absent for TRP itself. According to Yuwiler et al. (Yuwiler et al., 1977) and Curzon et al. (Curzon 1979), the observed CNS-periphery discrepancies in a mixed population of Huntington disease patients and healthy controls might be (partially) explained by the fact that most TRYCAT are known to bind circulating albumin (even with high affinity in case of TRP and KYN) and that only unbound (free) metabolites can enter the brain (Cangiano et al., 1999). This protein binding is advantageous as it provides a compound reserve in case of a temporal lack of supply. However, factors influencing the rate of albumin binding may intervene in a truthful peripheral representation of the central TRP metabolism. For instance, many drugs such as ibuprofen and valproate, pathology-induced non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs), and other competing amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine, leucine, and valine) (Walker et al., 2019) can displace TRP from its binding site and in so doing directly affect central TRYCAT levels (Yang et al., 2014). Undoubtedly, this contributes substantially to TRYCAT aberrations found in medicated vs. unmedicated patients. Moreover, structural modifiers like glycation (Anguizola et al., 2016) or pH (Walser and Hill 1993) may cause conformational changes to the protein and thereby modify affinities. For detailed discussion, we refer to an excellent review by Feng Yang (Yang et al., 2014).

While their value as peripheral biomarkers for central neuroinflammatory processes remains questionable due to fickle BBB crossing and volatile albumin binding, peripheral TRYCAT levels may “retroactively” influence activity in the brain. In exemplum, decreased intracerebral KYN uptake following leucine competition for the active L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) inhibits depression-like behavior in mice (Walker et al., 2019). Additionally, the essential amino acid TRP inevitably needs to relocate from the periphery to the brain. Again, albumin binding plays a role as only unbound TRP and KYN can bind LAT1 to actively cross the BBB. Whether free or total TRP concentration is the major determinant for in cerebro bioavailability remains unelucidated. While centrally, KA is generated in brain astrocytes, skeletal muscle is its major peripheral source of production (Agudelo et al., 2014). As this metabolite is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier and the level of similarity/synchronicity between peripheral and central inflammatory processes is currently undetermined, its suggested anti-inflammatory neuroactive effects may not be directly extrapolatable from its peripheral concentration. At best, somatic metabolization of KYN to KA by kynurenine aminotransferases (KATs) results in lower levels of peripheral KYN available for import in the brain and subsequent central conversion to neurotoxic QUIN. This is indirectly evidenced by experiments with PGC-1a1 overexpression transgenic mice, which specifically upregulate KATs in skeletal muscle and subsequently show elevated blood concentrations of KA, lower (circulating KYN), and stress resistance (Agudelo et al., 2014). This may contribute to the decrease of symptoms observed in depressed patients following physical exercise training. In reverse, lower baseline KA levels in MDD and SZ patients could originate from decreased muscular production in poorly active patients. Higher levels of non-KA-conversed peripheral KYN increase in cerebro bioavailability and could as such induce depression-like behavior, as demonstrated in rodents (O’Connor et al., 2009).

Living the TRYCAT Lifestyle

As illustrated above, muscle movement plays a major role in KA production. A sedentary lifestyle will therefore unquestionably affect kynurenine metabolization (Alme et al., 2021). Previous work showing that most KYN metabolites correlate with BMI (Zahed et al., 2021) indicates that lifestyle influences tryptophan metabolism also at the level of food intake. The amount and type of alimentation strongly define both the essential amino acid’s bioavailability and its metabolization. Vitamins B2 and B6 are KP cofactors; consequently, vitamin deficiency impacts kynurenine metabolite levels (Yeh and Brown 1977). TDO and IDO are iron porphyrin metalloproteins; hence, their enzymatic activity is dependent on iron supply. Moreover, prolonged inadequate food intake may result in low levels of serum albumin and as such interfere with free/bound metabolite fractions and consequent peripheral quantification (cfr. supra). As psychiatric patients are renowned for their poor eating habits, it is not inconceivable that varying peripheral TRYCAT levels largely reflect dietary insufficiencies. In support, Fellendorf et al. (Fellendorf et al., 2021) recently found TRP-to-KYN conversion in bipolar disorder to be facilitated by overweight and not by psychiatric symptomatology. This in turn raises the question as to whether TRYCAT aberrations in psychiatry are driven by syndrome-specific phenomena vs. being a by-product of other pan-pathological states like chronic stress-induced glucocorticoid resistance or sickness behavior hallmarking major depression and other psychiatric disorders (Zunszain et al., 2011).

According to Zahed et al. (Zahed et al., 2021), most TRYCAT remain relatively unaffected by smoking, which only appears to decrease QUIN, AA, and 3-HAA (Zahed et al., 2021). This may however be consequent to unassessed gender bias as Naz et al. (2019) demonstrate KYN and KA (but not TRP) levels to be lower in male smokers vs. non-smokers but remain unaffected in female smokers. Last, recreational drugs also interfere with homeostatic KP metabolite levels. Alcoholic beverages contain metabolically significant concentrations of KA, which is easily resorbed via the digestive tract and is quantifiable in peripheral blood. Hence, drinking beer and wine will artificially increase plasma [KA] (Turska et al., 2019). Cocaine use, on the other hand, will lower the amount of KA in blood (Araos et al., 2019). As comorbid substance use disorders are highly prevalent (∼30% (Toftdahl et al., 2016)) in mental health disorders, at least part of the variation in KP metabolite concentrations in psychiatry may be attributable to the (mis)use of varying types of recreational drugs.

Consult Gostner et al. (2020) for further elaboration on the interplay between lifestyle factors and TRP metabolization (Gostner et al., 2020).

The Enzyme Enigma

Aberrations in KP metabolite levels have been largely attributed to deviant enzyme activity. However, the processing rate of these enzymes has rarely been directly assessed in psychiatric disorders. Instead, enzyme concentrations have mostly been approximated by gene expression analysis (Favennec et al., 2015) or by ratios of metabolite concentrations. Illustratively, the KYN/TRP ratio is suggested to reflect the TRP-to-KYN metabolizer IDO, and KAT activity is deemed deductible from [KA/KYN]. While peripheral metabolite ratios may reflect enzyme activities in closed systems such as cell cultures, assuming those correlations in blood, let alone in the brain, may stretch things too far. In support, non-correspondence of the KYN/TRP ratio with IDO activity was evidenced in patients with hemodialysis (Kato et al., 2010) and in children (Yarbrough et al., 2018). Again, albumin binding proves problematic as bound fractions do not reflect current production rates. Furthermore, several isoforms exist for most pathway enzymes. Does [KYN/TRP] reflect IDO1, IDO2, or TDO? Which of the two main KAT isozymes is represented by [KA/KYN]? Moreover, aberrations in renal clearance or in functionality of downstream enzymes may lead to upstream metabolite accumulation and will as such influence ratios independently of target enzyme activity. An elaborate critical appraisal of the KYN/TRP ratio as proxy for IDO activity can be found in the review by Abdulla et al. (Badawy and Guillemin 2019). Last, a recent review describes several alternative routes of KA synthesis via non-KATs and even enzyme-free mechanisms (Blanco Ayala et al., 2015; Ramos-Chávez et al., 2018). It is conceivable that similar alternative means of production also exist for other TRYCAT, which strongly dilutes the relevance of using metabolite ratios as a proxy for single (and mostly rather nonspecific) enzymes. As discrepancies between IDO1 mRNA and protein levels have been reported (Théate et al., 2015), this too proves to unreliably reflect KP enzyme activities and underscores the need for alternative quantification strategies.

Tryptophan Catabolization: Not the Model Pathway!

Research on organs/diseases that are not or only hardly accessible/mimicable in humans often relies on animal studies to expand the pathophysiological knowledge. Nonetheless, caution is recommended when interpreting animal experimentation on TRYCAT in psychiatry. Not only are mood and psychotic disorders hard to model in animals, but the KP shows marked discrepancies in humans versus animals (Yeh and Brown 1977). Illustratively, TDO expression in humans is 5 to 10 fold lower than in rodents, and IDO activity suppresses human but not mouse lymphocyte proliferation (Torres Crigna et al., 2020). The latter reveals that these interspecies differences also functionally affect KP immunomodulation. Moreover, the fact that QUIN transport over the BBB occurs in gerbils but not in rats indicates that it even diverges between different species families of the same order (Heyes et al., 1997).

Methodological Mayhem

KP research in the field of psychiatry is typically hallmarked by low sample sizes in heterogeneous study populations. Moreover, patient populations also differ from healthy controls regarding multiple demographic variables (BMI, smoking habits, etc.), which may in themselves impact TRYCAT levels. Specifically, all KYN metabolites increase with BMI and with age (except xanthurenic acid (XA) and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3HAA)), and most are higher in males (Pertovaara et al., 2006; Zahed et al., 2021).

Alternate discrepancies in the literature may arise from the use of distinct analytical technologies. TRYCAT are almost exclusively measured using chromatographic methods such as high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). These quantify total concentrations, while unbound concentrations may be more relevant (cfr. supra). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS) and HPLC are performed with similar frequencies and show disagreement in concentration ranges, with some publications differing up to a staggering 1,000 times (Hartai et al., 2007; De Picker et al., 2019; Ulvik et al., 2020). Moreover, the concentration of several relevant kynurenine metabolites flirts with or even falls below the technological lower limit of detection of these methodologies (LC-MS quantification of QA, AA; unpublished data), implying caution concerning the scientific conclusiveness on their pathophysiological involvement. Last, sample collection is easily overlooked, though it is a crucial source of variance in TRYCAT quantification literature. Demonstrably, TRP is 15% higher in serum than in plasma (Yu et al., 2011) [with higher reproducibility in plasma, presumably due to coagulation-induced variance in serum (Bi et al., 2020)] and strongly increased in hemolytic samples (Kamlage et al., 2014). Heparin, an anticoagulant routinely used for plasma collection, is to be strictly avoided as it introduces severe chemical noise in LC-MS analyses (Yin et al., 2013) and interferes in albumin-TRP binding (Badawy 2010).

Discussion

What Path(way) to Take Next?

Tryptophan degradation through the kynurenine pathway has been widely implicated in the pathophysiology of a multitude of psychiatric disorders. KP derangement could even be involved causatively as mutations in SLC7A5, the gene coding for LAT1, have been linked to autism spectrum disorders (Tărlungeanu et al., 2016). Nonetheless, the research field is hallmarked by several pitfalls which might at least partially be circumvented by the hereby proposed guidelines.

→When quantifying peripheral metabolites to evaluate in cerebro bioavailability, unbound fractions in addition to total or bound levels need to be described. Thereby, one should take heed in optimizing their study design to account for modulators influencing freely circulating compound concentrations such as meal intake and type of collection tube (preferably collect fasting blood samples in EDTA-coated plasma tubes) (Badawy 2010). Alternatively, interference of albumin binding should be checked statistically by introducing [serum/plasma albumin] as a model covariate (van den Ameele et al., 2018; De Picker et al., 2019).

→When resorting to animal experimentation for fundamental exploration of kynurenine metabolization, larger mammalian species should be opted over rodent strains as KP characteristics in those animals show a higher degree of overlap with humans (Wang et al., 2018). Preferably, however, an in-depth scrutiny of the KP should be done in situ in human populations, for instance, via live imaging techniques (PET tracing of microglia activity) (De Picker et al., 2019), widespread characterization of KP metabolites in a multitude of bodily compartments (blood cells, urine, saliva, etc.), or clinical trials with compounds known to mediate the KP in animal research or other human pathologies such as IDO or KMO inhibitors (O’Connor et al., 2009; Prendergast et al., 2018; Réus et al., 2018).

→Metabolite ratios should be avoided to infer KP enzyme activity. Instead, enzyme concentrations or activities should be directly quantified in the fluidic compartments and/or judicious selections of blood. Successful assaying of KATs (in serum and erythrocytes), kynureninase (in lymphocytes), and IDO enzymes (in peripheral blood mononuclear cells) has been published elsewhere (Carlin et al., 1989; Ubbink et al., 1991; Hartai et al., 2007). Of note, immunogenic stimulation by for instance IFN-γ, is advised as basal enzyme activities may fall below detection limits in homeostatic circumstances (Edelstein et al., 1989). When direct measurement proves unattainable, enzyme activity can be inferred through detection of surrogate markers produced by high-specificity enzymes that respond to the same stimuli. Illustratively, neopterin, a pro-inflammatory marker of immune cell activation, proxies as a marker for IDO activity as IFN-γ also activates the key enzyme of neopterin synthesis (Werner-Felmayer et al., 1990). In parallel, enzyme activity can be deduced from direct measurement of protein levels. In support, in vitro IDO1 activity shows high correlation with protein expression (Wolf et al., 2009).

→In recent years, other pathway metabolites have gained interest as potentially having functional relevance in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Picolinic and xanthurenic acid, for instance, may act as trait markers for i.a. schizophrenia and therefore deserve to be more elaborately scrutinized in future endeavors (Fazio et al., 2015; Ryan et al., 2020).

→The recent emergence of sensitive commercial ELISA kits allows to demonopolize valuable TRYCAT metabolite and enzyme quantifications away from dedicated fully equipped, time-consuming, and expensive HPLC/LC-MS service labs toward broad-scale implementation to any research group with a basic laboratory infrastructure. As such, high-throughput quantifications on large sample sizes are now within reach.

Author Contributions

VC wrote the paper. VC, RV and MM provided conceptual content and revised the text.

Funding

This work was fully funded by personal funds of the University of Antwerp and the University Psychiatric Centre Duffel.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agudelo, L. Z., Femenía, T., Orhan, F., Porsmyr-Palmertz, M., Goiny, M., Martinez-Redondo, V., et al. (2014). Skeletal Muscle PGC-1α1 Modulates Kynurenine Metabolism and Mediates Resilience to Stress-Induced Depression. Cell 159, 33–45. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.051

Alme, K. N., Askim, T., Assmus, J., Mollnes, T. E., Naik, M., Næss, H., et al. (2021). Investigating Novel Biomarkers of Immune Activation and Modulation in the Context of Sedentary Behaviour: a Multicentre Prospective Ischemic Stroke Cohort Study. BMC Neurol. 21, 318. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02343-0

Anguizola, J., Debolt, E., Suresh, D., and Hage, D. S. (2016). Chromatographic Analysis of the Effects of Fatty Acids and Glycation on Binding by Probes for Sudlow Sites I and II to Human Serum Albumin. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1021, 175–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.09.041

Araos, P., Vidal, R., O'Shea, E., Pedraz, M., García-Marchena, N., Serrano, A., et al. (2019). Serotonin Is the Main Tryptophan Metabolite Associated with Psychiatric Comorbidity in Abstinent Cocaine-Addicted Patients. Sci. Rep. 9, 16842. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53312-0

Badawy, A. A., and Guillemin, G. (2019). The Plasma [Kynurenine]/[Tryptophan] Ratio and Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase: Time for Appraisal. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 12, 1178646919868978. doi:10.1177/1178646919868978

Badawy, A. A. (2010). Plasma Free Tryptophan Revisited: what You Need to Know and Do before Measuring it. J. Psychopharmacol. 24, 809–815. doi:10.1177/0269881108098965

Bi, H., Guo, Z., Jia, X., Liu, H., Ma, L., and Xue, L. (2020). The Key Points in the Pre-analytical Procedures of Blood and Urine Samples in Metabolomics Studies. Metabolomics 16, 68. doi:10.1007/s11306-020-01666-2

Blanco Ayala, T., Lugo Huitrón, R., Carmona Aparicio, L., Ramírez Ortega, D., González Esquivel, D., Pedraza Chaverrí, J., et al. (2015). Alternative Kynurenic Acid Synthesis Routes Studied in the Rat Cerebellum. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9, 178. doi:10.3389/fncel.2015.00178

Cangiano, C., Cardelli, P., Peverini, P., Giglio, R. M., Laviano, A., Fava, A., et al. (1999). Effect of Kynurenine on Tryptophan-Albumin Binding in Human Plasma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 467, 279–282. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4709-9_35

Carlin, J. M., Borden, E. C., Sondel, P. M., and Byrne, G. I. (1989). Interferon-induced Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase Activity in Human Mononuclear Phagocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 45, 29–34. doi:10.1002/jlb.45.1.29

Coppens, V., Morrens, M., Destoop, M., and Dom, G. (2019). The Interplay of Inflammatory Processes and Cognition in Alcohol Use Disorders-A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 10, 632. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00632

Curzon, G. (1979). Relationships between Plasma, CSF and Brain Tryptophan. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 15, 81–92. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-2243-3_7

De Picker, L., Fransen, E., Coppens, V., Timmers, M., de Boer, P., Oberacher, H., et al. (2019). Immune and Neuroendocrine Trait and State Markers in Psychotic Illness: Decreased Kynurenines Marking Psychotic Exacerbations. Front. Immunol. 10, 2971. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02971

Edelstein, M. P., Ozaki, Y., and Duch, D. S. (1989). Synergistic Effects of Phorbol Ester and INF-Gamma on the Induction of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in THP-1 Monocytic Leukemia Cells. J. Immunol. 143, 2969–2973.

Favennec, M., Hennart, B., Caiazzo, R., Leloire, A., Yengo, L., Verbanck, M., et al. (2015). The Kynurenine Pathway Is Activated in Human Obesity and Shifted toward Kynurenine Monooxygenase Activation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 2066–2074. doi:10.1002/oby.21199

Fazio, F., Lionetto, L., Curto, M., Iacovelli, L., Cavallari, M., Zappulla, C., et al. (2015). Xanthurenic Acid Activates mGlu2/3 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors and Is a Potential Trait Marker for Schizophrenia. Sci. Rep. 5, 17799. doi:10.1038/srep17799

Fellendorf, F. T., Gostner, J. M., Lenger, M., Platzer, M., Birner, A., Maget, A., et al. (2021). Tryptophan Metabolism in Bipolar Disorder in a Longitudinal Setting. Antioxidants (Basel) 10, 1795. doi:10.3390/antiox10111795

Gostner, J. M., Geisler, S., Stonig, M., Mair, L., Sperner-Unterweger, B., and Fuchs, D. (2020). Tryptophan Metabolism and Related Pathways in Psychoneuroimmunology: The Impact of Nutrition and Lifestyle. Neuropsychobiology 79, 89–99. doi:10.1159/000496293

Haroon, E., Welle, J. R., Woolwine, B. J., Goldsmith, D. R., Baer, W., Patel, T., et al. (2020). Associations Among Peripheral and central Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites and Inflammation in Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 998–1007. doi:10.1038/s41386-020-0607-1

Hartai, Z., Juhász, A., Rimanóczy, A., Janáky, T., Donkó, T., Dux, L., et al. (2007). Decreased Serum and Red Blood Cell Kynurenic Acid Levels in Alzheimer's Disease. Neurochem. Int. 50, 308–313. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2006.08.012

Hebbrecht, K., Skorobogatov, K., Giltay, E. J., Coppens, V., De Picker, L., and Morrens, M. (2021). Tryptophan Catabolites in Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 12, 667179. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.667179

Heyes, M. P., Saito, K., Chen, C. Y., Proescholdt, M. G., Nowak, T. S., Li, J., et al. (1997). Species Heterogeneity between Gerbils and Rats: Quinolinate Production by Microglia and Astrocytes and Accumulations in Response to Ischemic Brain Injury and Systemic Immune Activation. J. Neurochem. 69, 1519–1529. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041519.x

Kamlage, B., Maldonado, S. G., Bethan, B., Peter, E., Schmitz, O., Liebenberg, V., et al. (2014). Quality Markers Addressing Preanalytical Variations of Blood and Plasma Processing Identified by Broad and Targeted Metabolite Profiling. Clin. Chem. 60, 399–412. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2013.211979

Kato, A., Suzuki, Y., Suda, T., Suzuki, M., Fujie, M., Takita, T., et al. (2010). Relationship between an Increased Serum Kynurenine/tryptophan Ratio and Atherosclerotic Parameters in Hemodialysis Patients. Hemodial. Int. 14, 418–424. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00464.x

Marx, W., McGuinness, A. J., Rocks, T., Ruusunen, A., Cleminson, J., Walker, A. J., et al. (2021). The Kynurenine Pathway in Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia: a Meta-Analysis of 101 Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 4158–4178. doi:10.1038/s41380-020-00951-9

Morrens, M., Coppens, V., and Walther, S. (2020). Do immune Dysregulations and Oxidative Damage Drive Mood and Psychotic Disorders? Neuropsychobiology 79, 251–254. doi:10.1159/000496622

Morrens, M., De Picker, L., Kampen, J. K., and Coppens, V. (2020). Blood-based Kynurenine Pathway Alterations in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Schizophr Res. 223, 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.007

Naz, S., Bhat, M., Ståhl, S., Forsslund, H., Sköld, C. M., Wheelock, Å. M., et al. (2019). Dysregulation of the Tryptophan Pathway Evidences Gender Differences in COPD. Metabolites 9, 212. doi:10.3390/metabo9100212

O’Connor, J. C., Lawson, M. A., André, C., Moreau, M., Lestage, J., Castanon, N., et al. (2009). Lipopolysaccharide-induced Depressive-like Behavior Is Mediated by Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase Activation in Mice. Mol. Psychiatry 14, 511–522. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002148

Pertovaara, M., Heliövaara, M., Raitala, A., Oja, S. S., Knekt, P., and Hurme, M. (2006). The Activity of the Immunoregulatory Enzyme Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase Is Decreased in Smokers. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 145, 469–473. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03166.x

Prendergast, G. C., Malachowski, W. J., Mondal, A., Scherle, P., and Muller, A. J. (2018). Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and its Therapeutic Inhibition in Cancer. Int. Rev. Cel Mol. Biol. 336, 175–203. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2017.07.004

Ramos-Chávez, L. A., Huitrón, R. L., Esquivel, D. G., Pineda, B., Ríos, C., Silva-Adaya, D., et al. (2018). Relevance of Alternative Routes of Kynurenic Acid Production in the Brain. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 5272741. doi:10.1155/2018/5272741

Réus, G. Z., Becker, I. R. T., Scaini, G., Petronilho, F., Oses, J. P., Kaddurah-Daouk, R., et al. (2018). The Inhibition of the Kynurenine Pathway Prevents Behavioral Disturbances and Oxidative Stress in the Brain of Adult Rats Subjected to an Animal Model of Schizophrenia. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 81, 55–63. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.10.009

Ryan, K. M., Allers, K. A., McLoughlin, D. M., and Harkin, A. (2020). Tryptophan Metabolite Concentrations in Depressed Patients before and after Electroconvulsive Therapy. Brain Behav. Immun. 83, 153–162. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2019.10.005

Skorobogatov, K., De Picker, L., Verkerk, R., Coppens, V., Leboyer, M., Müller, N., et al. (2021). Brain versus Blood: A Systematic Review on the Concordance between Peripheral and Central Kynurenine Pathway Measures in Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Immunol. 12, 716980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.716980

Tărlungeanu, D. C., Deliu, E., Dotter, C. P., Kara, M., Janiesch, P. C., Scalise, M., et al. (2016). Impaired Amino Acid Transport at the Blood Brain Barrier Is a Cause of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cell 167, 1481.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.013

Théate, I., van Baren, N., Pilotte, L., Moulin, P., Larrieu, P., Renauld, J. C., et al. (2015). Extensive Profiling of the Expression of the Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 Protein in normal and Tumoral Human Tissues. Cancer Immunol. Res. 3, 161–172. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.cir-14-0137

Toftdahl, N. G., Nordentoft, M., and Hjorthøj, C. (2016). Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders in Psychiatric Patients: a Nationwide Danish Population-Based Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 51, 129–140. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1104-4

Torres Crigna, A., Uhlig, S., Elvers-Hornung, S., Klüter, H., and Bieback, K. (2020). Human Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells Suppress Human, but Not Murine Lymphocyte Proliferation, via Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Activity. Cells 9. doi:10.3390/cells9112419

Turska, M., Rutyna, R., Paluszkiewicz, M., Terlecka, P., Dobrowolski, A., Pelak, J., et al. (2019). Presence of Kynurenic Acid in Alcoholic Beverages - Is This Good News, or Bad News? Med. Hypotheses 122, 200–205. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2018.11.003

Ubbink, J. B., Hayward Vermaak, W. J., and Bissbort, S. (1991). Rapid High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Assay for Total Homocysteine Levels in Human Serum. J. Chromatogr. 565, 441–446. doi:10.1016/0378-4347(91)80407-4

Ulvik, A., Midttun, Ø., McCann, A., Meyer, K., Tell, G., Nygård, O., et al. (2020). Tryptophan Catabolites as Metabolic Markers of Vitamin B-6 Status Evaluated in Cohorts of Healthy Adults and Cardiovascular Patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 111, 178–186. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqz228

van den Ameele, S., Fuchs, D., Coppens, V., de Boer, P., Timmers, M., Sabbe, B., et al. (2018). Markers of Inflammation and Monoamine Metabolism Indicate Accelerated Aging in Bipolar Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 9, 250. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00250

Walker, A. K., Wing, E. E., Banks, W. A., and Dantzer, R. (2019). Leucine Competes with Kynurenine for Blood-To-Brain Transport and Prevents Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depression-like Behavior in Mice. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1523–1532. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0076-7

Walser, M., and Hill, S. B. (1993). Free and Protein-Bound Tryptophan in Serum of Untreated Patients with Chronic Renal Failure. Kidney Int. 44, 1366–1371. doi:10.1038/ki.1993.390

Wang, J., Takahashi, R. H., DeMent, K., Gustafson, A., Kenny, J. R., Wong, S. G., et al. (2018). Development of a Mass Spectrometry-Based Tryptophan 2, 3-dioxygenase Assay Using Liver Cytosol from Multiple Species. Anal. Biochem. 556, 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2018.06.025

Werner-Felmayer, G., Werner, E. R., Fuchs, D., Hausen, A., Reibnegger, G., and Wachter, H. (1990). Neopterin Formation and Tryptophan Degradation by a Human Myelomonocytic Cell Line (THP-1) upon Cytokine Treatment. Cancer Res. 50, 2863–2867.

Wolf, B., Posnick, D., Fisher, J. L., Lewis, L. D., and Ernstoff, M. S. (2009). Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase Enzyme Expression and Activity in Polarized Dendritic Cells. Cytotherapy 11, 1084–1089. doi:10.3109/14653240903271230

Yang, F., Zhang, Y., and Liang, H. (2014). Interactive Association of Drugs Binding to Human Serum Albumin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 3580–3595. doi:10.3390/ijms15033580

Yarbrough, M. L., Briden, K. E., Mitsios, J. V., Weindel, A. L., Terrill, C. M., Hunstad, D. A., et al. (2018). Mass Spectrometric Measurement of Urinary Kynurenine-To-Tryptophan Ratio in Children with and without Urinary Tract Infection. Clin. Biochem. 56, 83–88. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.04.014

Yeh, J. K., and Brown, R. R. (1977). Effects of Vitamin B-6 Deficiency and Tryptophan Loading on Urinary Excretion of Tryptophan Metabolites in Mammals. J. Nutr. 107, 261–271. doi:10.1093/jn/107.2.261

Yin, P., Peter, A., Franken, H., Zhao, X., Neukamm, S. S., Rosenbaum, L., et al. (2013). Preanalytical Aspects and Sample Quality Assessment in Metabolomics Studies of Human Blood. Clin. Chem. 59, 833–845. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2012.199257

Yu, Z., Kastenmüller, G., He, Y., Belcredi, P., Möller, G., Prehn, C., et al. (2011). Differences between Human Plasma and Serum Metabolite Profiles. PLoS One 6, e21230. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021230

Yuwiler, A., Oldendorf, W. H., Geller, E., and Braun, L. (1977). Effect of Albumin Binding and Amino Acid Competition on Tryptophan Uptake into Brain. J. Neurochem. 28, 1015–1023. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10664.x

Zahed, H., Johansson, M., Ueland, P. M., Midttun, Ø., Milne, R. L., Giles, G. G., et al. (2021). Epidemiology of 40 Blood Biomarkers of One-Carbon Metabolism, Vitamin Status, Inflammation, and Renal and Endothelial Function Among Cancer-free Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 11, 13805. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93214-8

Keywords: psychiatry, kynurenine, tryptophan, depression, mood disorder, schizophrenia

Citation: Coppens V, Verkerk R and Morrens M (2022) Tracking TRYCAT: A Critical Appraisal of Kynurenine Pathway Quantifications in Blood. Front. Pharmacol. 13:825948. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.825948

Received: 30 November 2021; Accepted: 19 January 2022;

Published: 15 February 2022.

Edited by:

Marta P. Pereira, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), SpainReviewed by:

Pablo Gimenez Gomez, University of Massachusetts Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Coppens, Verkerk and Morrens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Violette Coppens, dmlvbGV0dGUuY29wcGVuc0B1YW50d2VycGVuLmJl

Violette Coppens

Violette Coppens Robert Verkerk

Robert Verkerk Manuel Morrens

Manuel Morrens