- 1Department of Pharmacy, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2Evidence-bBsed Pharmacy Center, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 3NMPA Key Laboratory for Technical Research on Drug Products In Vitro and In Vivo Correlation, Chengdu, China

- 4Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children, Ministry of Education, Chengdu, China

- 5West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 6Department of Pediatrics, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 7West China School of Pharmacy, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 8Laboratory of Molecular Translational Medicine, Center for Translational Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Background: More than half of adverse drug events in pediatric patients are avoidable and blocking medication errors at the prescribing stage might be one of the most effective preventive measures.

Objective: To form a tool (a series of criteria) for detecting potentially inappropriate prescriptions in children, promote clinical rational drug use and reduce risks of medication in children.

Methods: Potentially inappropriate prescription propositions for children were collected through a systematic review. Then, the Delphi technique was adopted to form the final criteria. Panelists were asked to use a 5-point Likert scale to rate their agreement with each potentially inappropriate prescription proposition and were encouraged to add new propositions based on their clinical experience and knowledge. After 2 rounds of Delphi survey and propositions were fully revised and improved, the final criteria for identifying potentially inappropriate prescriptions in children were formed.

Results: The final criteria for identifying potential inappropriate prescriptions in children has 136 propositions, which were divided into “criteria for children with non-specific diseases/conditions” (71 propositions: 68 for potentially inappropriate medication, 3 for potential prescribing omission) and “criteria for children with specific diseases/conditions” (65 propositions: 55 for potentially inappropriate medication, 10 for potential prescribing omission), according to whether the proposition was about identifying specific risks associated with one drug in children with a specific other diseases/conditions that do not exist in children with other diseases/conditions.

Conclusion: A tool for screening potentially inappropriate prescriptions in children is formed to detect potentially inappropriate medication and prescribing omission in pediatrics and is available to all medical professionals liable to prescribe or dispense medicines to children.

1 Introduction

Prescriptions are generally considered appropriate when medicines on prescriptions have a clear evidence-based indication, are well tolerated in the majority of patients and are cost-effective. Conversely, prescriptions that do not meet the above conditions are considered inappropriate prescriptions. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) are prescriptions with potential risks that outweigh the benefits, which are more likely to be ultimately determined to be inappropriate than other prescriptions after a thorough review by clinicians or pharmacists. PIP consists of two parts—potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) and potential prescribing omission (PPO). PIM is medication when the potential risks of adverse drug events outweigh the potential clinical benefits, especially when safer or more effective alternatives are available. The inappropriateness of PIM mainly includes prescribing errors (inappropriate medicine selection, dosage, duration, drug-disease interaction, drug-drug interaction or drug-food interaction, etc.) and overprescribing. PPO is the omission of prescribing medicines with significant benefits to the patient’s length or quality of life in the absence of contraindications, underprescribing of beneficial drugs (Gallagher et al., 2008a).

Over the past three decades, many implicit or explicit indicators or criteria were developed to help detect PIPs in the ederly (Kaufmann et al., 2014; O'Connor et al., 2012; Spinewine et al., 2007). (an indicators or criteria is considered explicit if it consists of a series of clear and specific propositions.) Compared with implicit indicators (e.g., medication appropriateness index (MAI) (Hanlon et al., 1992; Hanlon and Schmader, 2013)), explicit criteria (e.g., START/STOPP criteria (O'Mahony et al., 2015) and Beer criteria (By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel, 2019)) require less clinical knowledge and experience of users, and are easier to implement manual or automated prescription review (Gillespie et al., 2013; Huibers et al., 2019a). It has been found in the elderly population that some explicit PIP criteria (such as START/STOPP criteria) have good applicability and reliability (Gallagher et al., 2008b; Gallagher et al., 2011; O'Mahony, 2020), and their use in PIPs screening can significantly improve the rationality of drug use, reduce adverse drug reactions (ADRs), readmissions, falls and medicine costs in elderly patients (Hill-Taylor et al., 2016).

As the other special population, children’s prescription quality has always been the focus of many medical workers and researchers. Due to the difficulty in conducting clinical trials in children (difficulties in recruiting and organizing subjects), information on children’s medication is lacking and the safety, efficacy and economic interests of many drugs in children are unknown. A large number of off-label and high-risk pediatric prescriptions cause serious safe problems and greatly increase medication risk in children (from mild rashes to serious adverse reactions such as preventable death and prolonged hospitalization) (Balan et al., 2018; Shuib et al., 2021). In the pediatric population, the incidence of ADRs in inpatients is 9.53% and in outpatients is 1.46%; and the incidence of ADRs leading to hospital admission in children is 2.09% (Impicciatore et al., 2001). Unlike the elderly, the development of explicit PIP criteria for children is in its infancy, and there are only five PIP criteria for children (Prot-Labarthe et al., 2011; Barry et al., 2016; Corrick et al., 2019; Meyers et al., 2020; Sadozai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). Experts in France were the first to develop the PIP criteria for children. They released the POPI criteria (Pediatrics: Omission of Prescriptions and Inappropriate Prescriptions) in 2011 (Prot-Labarthe et al., 2011), then the United Kingdom (Barry et al., 2016; Corrick et al., 2019) and the US (Meyers et al., 2020) successively released their PIP criteria for children. We previously conducted a comprehensive systematic review on existing tools for identifying PIPs in children and their applicability in clinical practices (Li et al., 2022) and regrettably found that China has not yet developed a tool for detecting PIPs in children based on its actual clinical practice.

It is reported that children accounts for about 30% of the total population and pediatric diseases account for about 20% of all medical consultations in China. The incidence of ADRs in children in China is twice that in adults (in neonates is four times); About 7 000 children die of medication errors every year and the incidence of irrational drug use is 12%–32% (Tang, 2014; National Medical Products Administration, 2020; Cui et al., 2021; Zhao, 2021); Among children under the age of 14, approximately 30,000 children are deaf each year due to inappropriate medication (Zhao, 2021). Our study aimed to form a series of criteria for detecting PIPs in children, with a view to applying them to review and intervene in pediatric prescribing, to promote clinical rational drug use and reduce medication risk in children.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Forming preliminary children’s potentially inappropriate prescription criteria

2.1.1 Systematically searching and extracting children’s potentially inappropriate prescription propositions

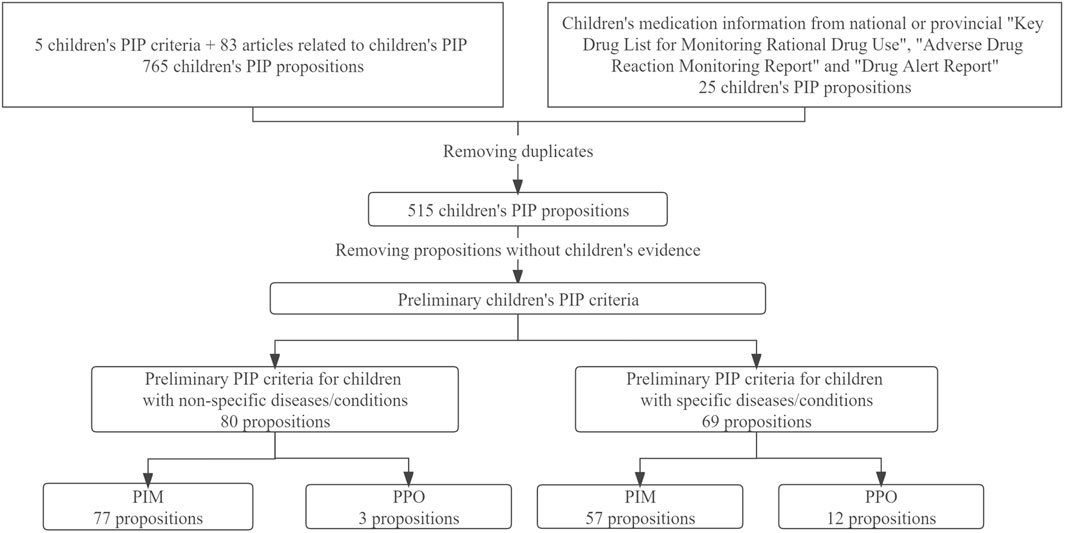

Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Library, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang Data were systematically searched to identify articles related to children’s PIP. Moreover, reference lists of included articles, children’s medication information from national or provincial “Key Drug List for Monitoring Rational Drug Use,” “Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Report” and “Drug Alert Report” were used as supplementary search sources to identify additional children’s PIP propositions. The retrieval time of databases was as of July 2021. Then, we reviewed all articles related to PIP in children (age <18 years) and extracted PIP criteria or propositions from them. The detailed search strategy, eligibility criteria and literature screening and selection results could be found in Supplementary Material S1.

2.1.2 Searching evidence related to included potentially inappropriate prescription propositions

For each PIP proposition, we searched for relevant evidence including clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, original clinical studies, expert consensus, National Children’s Formulary, drug package inserts and other supplemental materials provided by pharmaceutical companies, etc. The preliminary children’s PIP criteria were formed after removing PIP propositions that were not supported by children’s evidence or without children’s evidence.

2.2 Delphi method

We revised and validated the preliminary criteria by a two-round modified Delphi (Hasson et al., 2000) before finally forming the children’s PIP criteria. The purpose of conducting Delphi method is to achieve a convergence of opinion and a general consensus on a particular topic, by questioning experts through successive questionnaires.

2.2.1 Selection of the Delphi panel

The criteria for selecting the members of the expert panel were as follows: 1) Clinicians or pharmacists; 2) Deputy senior professional title or above; 3) Engaged in pediatric clinical work ≥10 years; 4) The workplace of the expert is a tertiary hospital 5) Interested in our study and able to complete 2 rounds of questionnaires on time.

The reason why we chose clinicians or pharmacists from tertiary hospitals and engaged in pediatric clinical work ≥10 years as panelists was that experts from tertiary hospitals might have better access to the latest and best evidence and knowledge, more experience with medication, and more diverse and complex patients than those from primary health care and those engaged in pediatric clinical practice for a short time in China.

2.2.2 Data collection and analysis

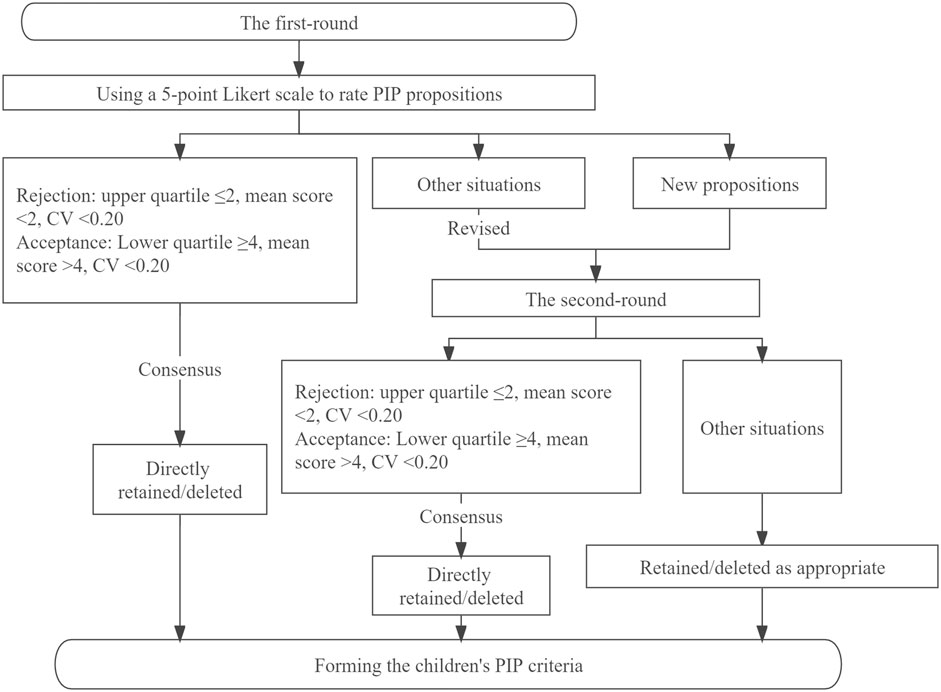

Electronic questionnaires were sent to the panelists by e-mail. The panelists were asked to comprehensively evaluate the clinical applicability and feasibility of the preliminary children’s PIP criteria, and use a 5-point Likert scale to rate their agreement for each PIP proposition. One point and 5 points respectively meant “completely disagree” and “completely agree”, and for propositions rated < 4 points, panelists were required to provide reasons why the proposition was unreasonable or unfeasible. Panelists could comment on existing PIP propositions or propose new PIP propositions based on their clinical experience, while encouraging them to cite appropriate evidence to support these new PIP propositions. Each of the panelists who had participated in the first round was sent the second-round questionnaire with feedback on the results of the first round (including the average panel rating and the full score rate). The panelists were then asked to re-rate revised propositions without consensus based on both their opinion and the group response to the previous round (Figure 1).

Criteria for reaching consensus were set before starting the Delphi survey. When the upper quartile ≤2 points, the mean score < 2 points and the coefficient of variation (CV) < 0.20, this indicated there was consensus by the Delphi panel members on rejection of the PIP proposition. When the lower quartile ≥4, the mean score > 4 points, CV < 0.20, this indicated there was consensus by the Delphi panel members on acceptance of the PIP proposition. Other situations indicated a lack of consensus among experts, and after revision, these propositions would along with new propositions proposed by panelists enter the second round. If consensus was not reached after the second round, the proposition was retained or deleted as appropriate based on the principles of scientificity and feasibility, and expert comments.

The calculation of the mean score (

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary children’s potentially inappropriate prescription criteria

A total of 787 propositions for children’s PIP were extracted, and 515 propositions were retained after removing duplicates. A total of 366 propositions without children’s evidence were excluded, then the preliminary children’s PIP criteria (149 propositions) were formed. According to whether the proposition could only be used to detect PIPs in children with specific diseases or conditions, propositions were divided into two parts—“PIP criteria for children with non-specific diseases/conditions” [e.g., “Tricyclic antidepressants desipramine and imipramine in children (PIM),” “Chloramphenicol in neonates” (PIM)”] and “PIP criteria for children with specific diseases/conditions” [e.g., “Codeine for children after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (PIM)”, “Loperamide for children <4 years or with acute infectious diarrhea (PIM)”, “Oral rehydration solution (ORS) for dehydrated children unless intravenous fluid therapy is indicated (shock, red flag symptoms despite ORS, persistent vomiting of ORS) (PPO)”]. Finally, there were a total of 80 preliminary PIP propositions in “PIP criteria for children with non-specific diseases/conditions”, including 77 PIM propositions and 3 PPO propositions; the “PIP criteria for children with specific diseases/conditions” consisted of 69 preliminary PIP propositions, including 57 PIM propositions and 12 PPO propositions (Figure 2).

3.2 Composition of the Delphi panel

In total, 19 pediatric specialists from tertiary hospitals were invited to participate in a Delphi panel to develop these criteria. In the end, A total of 16 specialists agreed to participate. The panel consisted of 11 clinicians and 5 pharmacists and they specialized in pediatric emergency and critical care, pediatric infection, pediatric hematology, pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric rheumatology, pediatric respiratory, pediatric neurology, and clinical pharmacy. Moreover, 11 specialists (69%) engaged in pediatric clinical work for more than 20 years.

3.3 Children’s potentially inappropriate prescription criteria

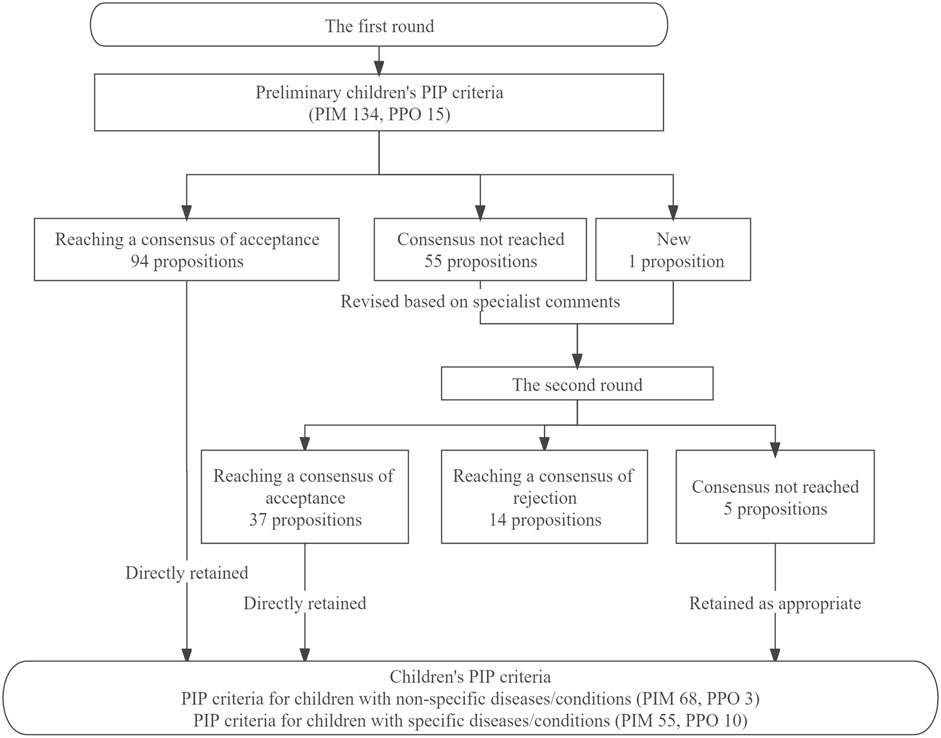

After the first-round Delphi survey, 94 propositions reached a consensus and were directly retained, and none of the propositions was directly rejected. Fifty-five propositions without consensus were revised according to specialists’ comments and entered into the second round together with 1 new proposition proposed by specialists in the first round, and 42 propositions were finally retained after reviewing specialists’ comments and suggestions. Figure 3 presented the results of the Delphi survey.

A total of 136 PIP propositions were included in the final children’s PIP criteria, 71 propositions for PIP criteria in children with non-specific diseases/conditions (PIM 68, PPO 3), and 65 propositions for PIP criteria in children with specific diseases/conditions (PIM 55, PPO 10).

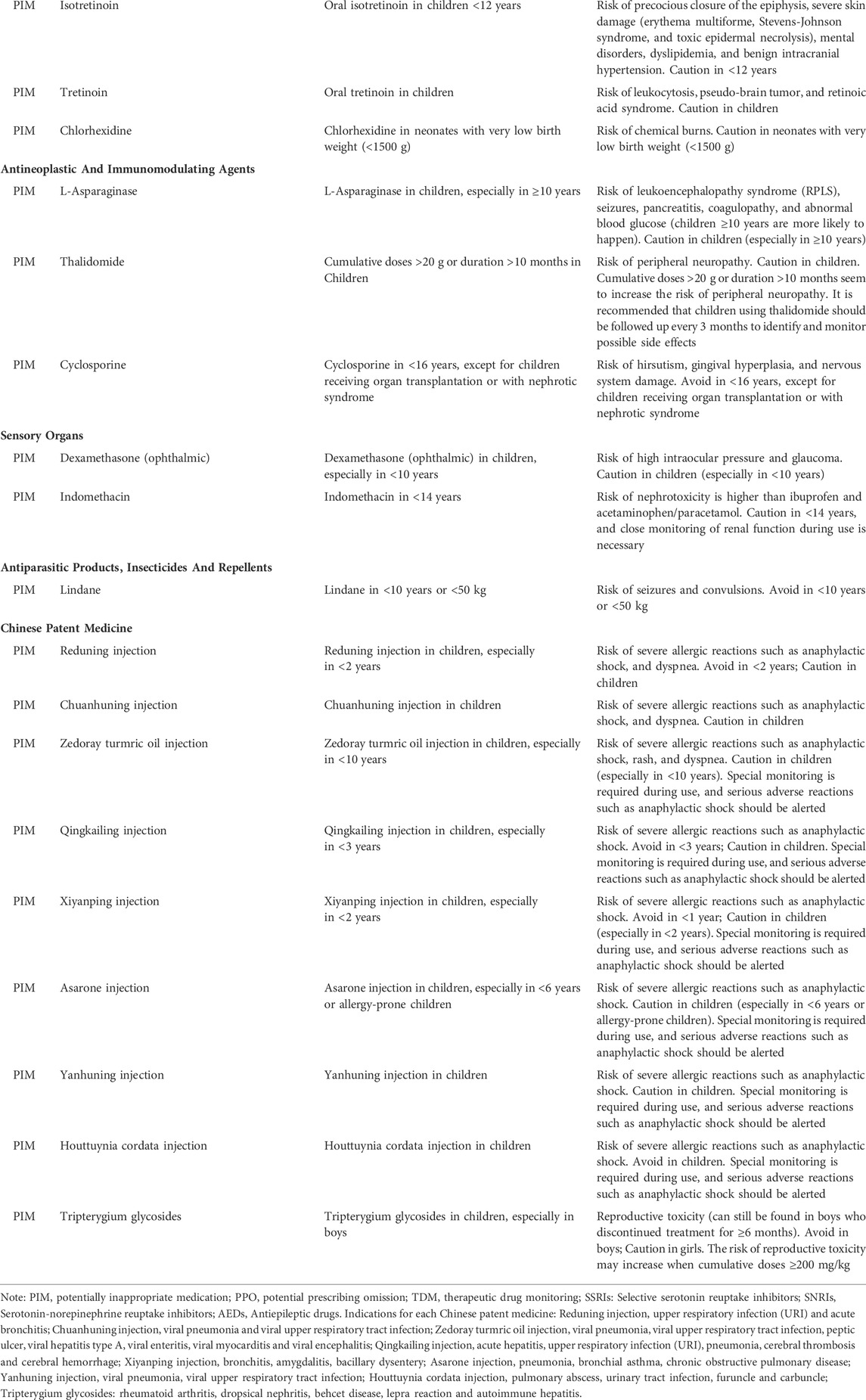

The PIP criteria in children with non-specific diseases/conditions included anti-infective drugs, nervous system drugs, Chinese patent medicines, digestive system drugs, respiratory system drugs, dermatological drugs, anti-tumor drugs and immune drugs, sensory organs drugs, cardiovascular system drugs, skeletal-muscular system drugs, antiparasitic drugs. The numbers of PIP propositions for anti-infective drugs and nervous system drugs were the two largest, with 22 and 15 propositions, respectively (Table 1).

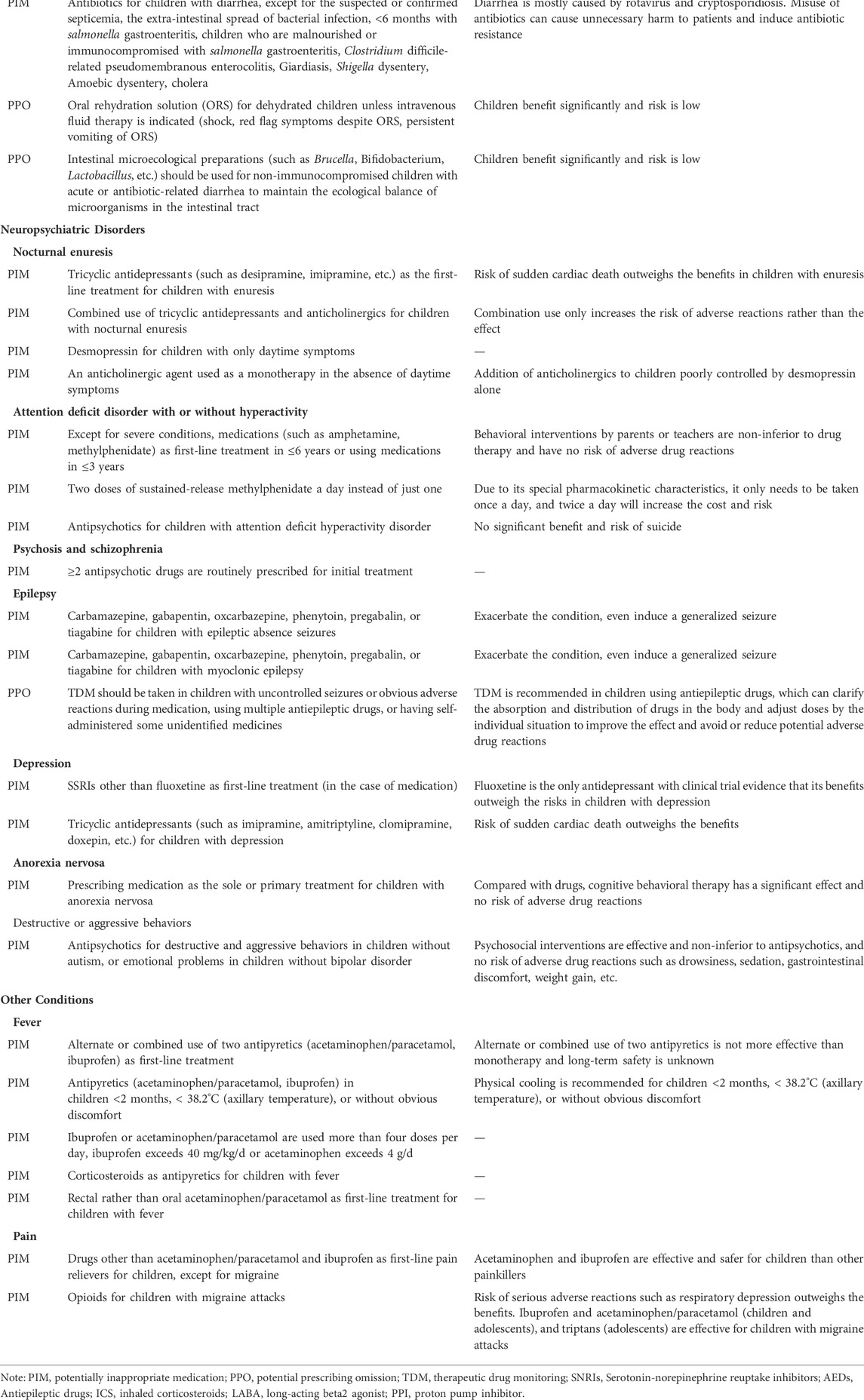

The PIP criteria in children with specific diseases/conditions are mainly used to detect PIPs in children with a certain disease or condition, covering disease problems including respiratory problems (e.g., respiratory infections and asthma), neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., nocturnal enuresis and attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity), dermatological problems (e.g., atopic eczema and acne vulgaris), digestive problems (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux and diarrhea), urinary problems (urinary infections), and other conditions (fever and pain). There were 17 propositions used to detect PIPs in children with respiratory diseases, which was the largest number (Table 2).

4 Discussion

Pediatric patients are uniquely vulnerable to ADRs due to the immature organs and systems that metabolize and excrete drugs, and some medicines need to be used more cautiously in children (Kaushal et al., 2010; Davis, 2011). Davis’s study results showed that more than half of adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients were avoidable, and blocking medication errors at the prescribing stage might be one of the most effective preventive measures (Davis, 2011). It is increasingly recognized that rational prescribing is an important issue for children (Choonara, 2013). We developed a set of criteria for detecting PIPs in children through a modified Delphi method, with the target user population being healthcare workers who treat children under 18 years of age. The criteria can be used as a quality control tool for pediatric prescribing to improve medication safety in children. Moreover, the criteria can be used to investigate the prevalence of PIPs in children and track its changes over time to help evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of relevant policies and measures.

4.1 Propositions with more controversy among panelists

There has been a heated debate among panelists as to whether “Nasal or oral decongestants for children with acute upper respiratory tract infection” should be included in the children’s PIP criteria. The Recommendation 1.3.3 in the “Sinusitis (acute): antimicrobial prescribing NICE guideline (NG79)” (Sinusitis, 2021) showed that “No evidence was found for using oral decongestants,” and the Recommendation 1.2.2 in the “Otitis media (acute): antimicrobial prescribing NICE guideline (NG91)” (NICE, 2021) also indicated that “Decongestants do not help symptom relief.” However, during the Delphi survey, some specialists commented that decongestants could relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life in children in time and the risk of short-term use might be small. Finally, considering the current evidence, specialists’ comments and actual clinical practice, we revised this proposition to “Nasal or oral decongestants >7 days for children with acute upper respiratory tract infection” and retained it.

No strong evidence was found to support the avoidance of fluoroquinolones in children. At present, there is no case report of severe and irreversible bone or cartilage damage in children caused by quinolones. Only the results of animal experiments showed that quinolones might permanently damage the soft tissues of the weight-bearing joints in young animals, causing the erosion of the weight-bearing joints or other joint diseases (Tatsumi et al., 1978; Gough et al., 1979). Moreover, in specific populations, such as children with complicated urinary tract infections, cystic fibrosis, and some community-acquired pneumonia cases, quinolones may have to be used (Jackson and Schutze, 2016). However, considering the Chinese National Children’s Formulary (Chinese National Formulary Editorial Committee, 2013) and the instructions of quinolones which clearly stated that “This product should be avoided in people under 18 years old,” this proposition was eventually retained in the children’s PIP criteria, with revising “Avoid in children” to “Caution in children.”

Aspirin is avoided in children with viral respiratory infections (flu and chickenpox) because of the risk of Raye’s syndrome. In the Delphi survey, some specialists questioned the authenticity of this association because the quality of the evidence was very low (Brunell et al., 1982; National surveillance for Reye syndrome, 1982; Surgeon General, 1982; Belay et al., 1999). However, this proposition was retained due to the serious harm of this adverse reaction (may lead to the death of children).

4.2 Comparison with existing children’s potentially inappropriate prescription criteria

The earliest PIP criteria for children is the POPI tool developed by French experts using the Delphi method (Prot-Labarthe et al., 2014), which is the basis for the POPI United Kingdom tool (Corrick et al., 2019) and the POPI Int tool (Sadozai et al., 2020) (both of them are formed after modifying the POPI tool). It consists of 105 PIP propositions that can be used by all medical professionals responsible for prescribing or dispensing medicines to children to detect potentially inappropriate medication and prescribing omission in pediatrics. Study results have shown the good applicability (Berthe-Aucejo et al., 2019a) and reliability (Berthe-Aucejo et al., 2019b) of this tool in French pediatric clinical practice. Thirty-one propositions in the POPI tool are consistent with our criteria (e.g., “Rectal rather than oral acetaminophen/paracetamol as first-line treatment for children with fever,” “Opioids for children with migraine attacks,” “Erythromycin as a prokinetic agent for children with nausea, vomiting or gastroesophageal reflux”, etc.), 24 propositions are different from our criteria (e.g., POPI: “Oral solutions of ibuprofen administered in more than three doses per day using a graduated pipette of 10 mg/kg (other than Advil),” “Loperamide before 3 years of age”; Our criteria: “Ibuprofen or acetaminophen/paracetamol are used more than four doses per day, ibuprofen exceeds 40 mg/kg/d or acetaminophen exceeds 4 g/d,” “Loperamide for children <4 years with acute infectious diarrhea,” etc.).

In 2020, after critical analysis, peer review, and public review, a list of drugs that are potentially inappropriate for use in pediatric patients has been developed and titled the “KIDs List” (Meyers et al., 2020), which contains 67 drugs and/or drug classes and 10 excipients. Twenty-three propositions in the list are consistent with our criteria [e.g., “Ceftriaxone; Kernicterus; Caution in neonates,” “Chloramphenicol; Gray baby syndrome; Avoid neonates, unless the blood concentration is monitored,” “Midazolam; Severe intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, or death; Avoid in neonates with very low birth weight (<1500 g),” etc.], 9 propositions are different from our criteria [e.g., KIDs List: “Azithromycin or erythromycin (oral and intravenous); Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; Avoid in neonates,” “Valproic acid and derivatives; Pancreatitis, fatal hepatotoxicity; Avoid in infants, caution in <6 years”; Our criteria: “Azithromycin or erythromycin (oral or intravenous); Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; Avoid in neonates ≤14 days,” “Valproic acid and its derivatives; Pancreatitis, fatal hepatotoxicity; Avoid in <2 years, especially in children with metabolic or mitochondrial diseases, or are taking other antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin”].

4.3 Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study relates to use of the Delphi technique. Although it is a commonly used method, the reliability of the Delphi method for achieving consensus has been debated. The information gathered using a Delphi method represents only the views of chosen experts about a specific practice at a particular time and the results may vary depending on the experts included in the panel. In this study, to ensure the reliability of the final results, we invited 16 specialists with extensive pediatric clinical experience (All have been engaged in pediatric clinical work for more than 10 years, and more than half of them more than 20 years) to participate in a Delphi panel. Moreover, we also provided panelists with the best currently available evidence for each proposition during the Delphi process to help them better evaluate and comment. Second, this standard can only be used as a screening tool for potentially inappropriate prescriptions, and cannot directly determine the final rationality of prescriptions in place of comprehensive clinical assessment, especially in some patients with complex conditions. Under special situations, children using the drugs in children’s PIP criteria may be necessary after the children’s overall clinical situation has been fully assessed (prescriptions are appropriate at this time). Moreover, these criteria do not mandate absolute contraindications to any drug use in children and are only intended to provide medication warnings to pediatric clinicians or pharmacists. Third, only drugs that have been marketed in China and Chinese pediatric clinical practice were considered in the criteria forming process. Therefore, these PIP criteria may not directly apply to pediatric patients in other countries. However, other countries can modify the criteria based on the national drug listing situation and current clinical guidelines to improve its applicability. Finally, these criteria have not been tested in an actual clinical practice setting and remain to be validated. We will conduct two studies in the future. One study will measure the reliability of the criteria by examining the degree of consistency of PIP assessment results among users (Kappa), and the other study will evaluate the capacity of the criteria to detect PIPs in pediatrics to measure the clinical applicability and feasibility of the criteria.

4.4 Subsequent research and practice directions

Like the “STOPP/START criteria” (Huibers et al., 2019b) and the “PIM-Check criteria” (Blanc et al., 2018a; Blanc et al., 2018b) for the elderly, integrating our children’s PIP propositions into the clinical decision support system through computer coding algorithms to realize the automated identification and quantification of children’s PIP, which may be expected to improve the rationality of drug use in pediatric patients, reduce medication risk, and also contribute to the continuous improvement of medical quality.

5 Conclusion

A tool for screening potentially inappropriate prescriptions in children is formed to detect potentially inappropriate medication and prescribing omission in pediatrics and is available to all medical professionals liable to prescribe or dispense medicines to children. Moreover, we will conduct two subsequent studies to evaluate the reliability and clinical applicability of this tool.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SL substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study, conducted the whole study (including the systematic review of children’s potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP) items, searching for evidence for each item and two rounds of Delphi surveys), organized and analyzed data and drafted the initial manuscript; LH substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study and conducted the whole study (including the systematic review of children’s potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP) items, searching for evidence for each item and two rounds of Delphi surveys); LZ conducted the systematic review of children’s potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP) items, including screening of abstracts and full text and extracting data; DY designed and conducted two rounds of Delphi surveys; Z-JJ and GC reviewed and revised the manuscript; LZ conceptualized the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Sichuan Province Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2020YFS0035).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to our panelists: DH Shi, QY Tang, ChY Wang, F Wang, J Yu, ShL Ma, J Hu, YX Zou, YY Sun, W Xie, DK He, ShH Bu, X Zhao, D Yu, Sh Gao, and L Qiu. Thanks to Sichuan Province Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2020YFS0035) for supporting this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1019795/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PIM, Potentially inappropriate medication; PIP, Potentially inappropriate prescription; PPO, Potential prescribing omission.

References

Balan, S., Hassali, M., and Mak, V. (2018). Two decades of off-label prescribing in children: A literature review. World J. Pediatr. 14 (6), 528–540. doi:10.1007/s12519-018-0186-y

Barry, E., O'Brien, K., Moriarty, F., Cooper, J., Redmond, P., Hughes, C. M., et al. (2016). PIPc study: Development of indicators of potentially inappropriate prescribing in children (PIPc) in primary care using a modified Delphi technique. Bmj Open 6 (9), e012079. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012079

Belay, E. D., Bresee, J. S., Holman, R. C., Khan, A. S., Shahriari, A., and Schonberger, L. B. (1999). Reye's syndrome in the United States from 1981 through 1997. N. Engl. J. Med. 340 (18), 1377–1382. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905063401801

Berthe-Aucejo, A., Nguyen, N., Angoulvant, F., Boulkedid, R., Bellettre, X., Weil, T., et al. (2019). Interrater reliability of a tool to assess omission of prescription and inappropriate prescriptions in paediatrics. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 41 (3), 734–740. doi:10.1007/s11096-019-00819-1

Berthe-Aucejo, A., Nguyen, P., Angoulvant, F., Bellettre, X., Albaret, P., Weil, T., et al. (2019). Retrospective study of irrational prescribing in French paediatric hospital: Prevalence of inappropriate prescription detected by pediatrics: Omission of prescription and inappropriate prescription (POPI) in the emergency unit and in the ambulatory setting. Bmj Open 9 (3), e019186. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019186

Blanc, A. L., Guignard, B., Desnoyer, A., Grosgurin, O., Marti, C., Samer, C., et al. (2018b). Prevention of potentially inappropriate medication in internal medicine patients: A prospective study using the electronic application PIM-check. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 43 (6), 860–866. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12733

Blanc, A. L., Spasojevic, S., Leszek, A., Théodoloz, M., Bonnabry, P., Fumeaux, T., et al. (2018). A comparison of two tools to screen potentially inappropriate medication in internal medicine patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 43 (2), 232–239. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12638

Brunell, P. A., Cherry, J. D., Ector, W. L., Gershon, A. A., Gotoff, S. P., et al. Committee on Infectious Diseases (1982). Aspirin and Reye syndrome. Pediatrics 69 (6), 810–812. doi:10.1542/peds.69.6.810

By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel (2019). American Geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67 (4), 674–694. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767

Chinese National Formulary Editorial Committee (2013). China national formulary (children’s Edition). Beijing: People's medical publishing house.

Choonara, I. (2013). Rational prescribing is important in all settings. Arch. Dis. Child. 98 (9), 720. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304559

Corrick, F., Choonara, I., Conroy, S., and Sammons, H. (2019). Modifying a paediatric rational prescribing tool (POPI) for use in the UK. Healthc. (Basel) 7 (1), E33. doi:10.3390/healthcare7010033

Cui, J., Zhao, L., Liu, X., Liu, M., and Zhong, L. (2021). Analysis of the potential inappropriate use of medications in pediatric outpatients in China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21 (1), 1273. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07300-8

Davis, T. (2011). Paediatric prescribing errors. Arch. Dis. Child. 96 (5), 489–491. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.200295

Gallagher, P., Lang, P. O., Cherubini, A., Topinkova, E., Cruz-Jentoft, A., Montero Errasquin, B., et al. (2011). Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 67 (11), 1175–1188. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1061-0

Gallagher, P., Ryan, C., Byrne, S., Kennedy, J., and O'Mahony, D. (2008). STOPP (screening tool of older person's prescriptions) and START (screening tool to Alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 46 (2), 72–83. doi:10.5414/cpp46072

Gallagher, P., Ryan, C., Byrne, S., Kennedy, J., and O'Mahony, D. (2008). STOPP (screening tool of older person's prescriptions) and START (screening tool to Alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 46 (2), 72–83. doi:10.5414/cpp46072

Gillespie, U., Alassaad, A., Hammarlund-Udenaes, M., Morlin, C., Henrohn, D., Bertilsson, M., et al. (2013). Effects of pharmacists' interventions on appropriateness of prescribing and evaluation of the instruments' (MAI, STOPP and STARTs') ability to predict hospitalization--analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Plos One 8 (5), e62401. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062401

Gough, A., Barsoum, N. J., Mitchell, L., McGuire, E. J., and de la Iglesia, F. A. (1979). Juvenile canine drug-induced arthropathy: Clinicopathological studies on articular lesions caused by oxolinic and pipemidic acids. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 51 (1), 177–187. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(79)90020-6

Hanlon, J. T., Schmader, K. E., Samsa, G. P., WeinbergerM., , Uttech, K. M., Lewis, I. K., et al. (1992). A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 45 (10), 1045–1051. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c

Hanlon, J. T., and Schmader, K. E. (2013). The medication appropriateness index at 20: Where it started, where it has been, and where it may be going. Drugs Aging 30 (11), 893–900. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0118-4

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., and McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 32 (4), 1008–1015. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

Hill-Taylor, B., Walsh, K. A., Stewart, S., Hayden, J., Byrne, S., and Sketris, I. S. (2016). Effectiveness of the STOPP/START (screening tool of older persons' potentially inappropriate prescriptions/screening tool to Alert doctors to the right treatment) criteria: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 41 (2), 158–169. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12372

Huibers, C., Sallevelt, B., de Groot, D. A., Boer, M. J., van Campen, J. P. C. M., Davids, C. J., et al. (2019). Conversion of STOPP/START version 2 into coded algorithms for software implementation: A multidisciplinary consensus procedure. Int. J. Med. Inf. 125, 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.12.010

Huibers, C., Sallevelt, B., de Groot, D. A., Boer, M. J., van Campen, J. P. C. M., Davids, C. J., et al. (2019). Conversion of STOPP/START version 2 into coded algorithms for software implementation: A multidisciplinary consensus procedure. Int. J. Med. Inf. 125, 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.12.010

Impicciatore, P., Choonara, I., Clarkson, A., Provasi, D., Pandolfini, C., and Bonati, M. (2001). Incidence of adverse drug reactions in paediatric in/out-patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52 (1), 77–83. doi:10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01407.x

Jackson, M. A., and Schutze, G. E. (2016). The use of systemic and topical fluoroquinolones. Pediatrics 138 (5), e20162706. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2706

Kaufmann, C. P., Tremp, R., Hersberger, K. E., and Lampert, M. L. (2014). Inappropriate prescribing: A systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1575-8

Kaushal, R., Goldmann, D. A., Keohane, C. A., Abramson, E. L., Woolf, S., Yoon, C., et al. (2010). Medication errors in paediatric outpatients. Qual. Saf. Health Care 19 (6), e30. doi:10.1136/qshc.2008.031179

Li, S., Huang, L., Chen, Z., Zeng, L., Li, H., Diao, S., et al. (2022). Tools for identifying potentially inappropriate prescriptions for children and their applicability in clinical practices: A systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 787113. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.787113

Meyers, R. S., Thackray, J., Matson, K. L., McPherson, C., Lubsch, L., Hellinga, R. C., et al. (2020). Key potentially inappropriate drugs in pediatrics: The KIDs list. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (3), 175–191. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-25.3.175

National Medical Products Administration (2020). National adverse drug reaction monitoring report, 2021. Available at: http://www.cdr-adr.org.cn/tzgg_home/202103/t20210326_48414.html (Accessed April 12, 2021).

National surveillance for Reye syndrome (1982). National surveillance for Reye syndrome, 1981: Update, Reye syndrome and salicylate usage. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 31 (5), 53–6–61.

NICE (2021). Otitis media (acute): Antimicrobial prescribing NICE guideline. [NG91]Published: 28 March 2018 Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng91/chapter/Recommendations#managing-acute-otitis-media (Accessed June 19, 2021).2018

O'Connor, M. N., Gallagher, P., and O'Mahony, D. (2012). Inappropriate prescribing: Criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging 29 (6), 437–452. doi:10.2165/11632610-000000000-00000

O'Mahony, D., O'Sullivan, D., Byrne, S., O'Connor, M. N., Ryan, C., and Gallagher, P. (2015). STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 44 (2), 213–218. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu145

O'Mahony, D. (2020). STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate medications/potential prescribing omissions in older people: Origin and progress. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 13 (1), 15–22. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1697676

Prot-Labarthe, S., Vercheval, C., Angoulvant, F., Brion, F., and Popi, Bourdon O. (2011). [POPI: A tool to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing practices for children]. Arch. Pediatr. 18 (11), 1231–1232. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2011.08.019

Prot-Labarthe, S., Weil, T., Angoulvant, F., Boulkedid, R., Alberti, C., and Bourdon, O. (2014). POPI (pediatrics: Omission of prescriptions and inappropriate prescriptions): Development of a tool to identify inappropriate prescribing. Plos One 9 (6), e101171. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101171

Sadozai, L., Sable, S., Le Roux, E., Coste, P., Guillot, C., Boizeau, P., et al. (2020). International consensus validation of the POPI tool (Pediatrics: Omission of Prescriptions and Inappropriate prescriptions) to identify inappropriate prescribing in pediatrics. Plos One 15 (10), e0240105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240105

Shuib, W., Wu, X. Y., and Xiao, F. (2021). Extent, reasons and consequences of off-labeled and unlicensed drug prescription in hospitalized children: A narrative review. World J. Pediatr. 17 (4), 341–354. doi:10.1007/s12519-021-00430-3

Sinusitis, N. I. C. E. (2021). (acute): Antimicrobial prescribing NICE guideline, 2017. [NG79]Published: 27 October 2017 Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng79/chapter/Recommendations#managing-acute-sinusitis (Accessed June 19, 2021).

Spinewine, A., Schmader, K. E., Barber, N., Hughes, C., Lapane, K. L., Swine, C., et al. (2007). Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: How well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 370 (9582), 173–184. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5

Surgeon General's advisory on the use of salicylates and Reye syndrome. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.. 1982;31(22):289–290.

Tang, J. (2014). Implement the "China children's development outline (2011-2020)" and the "twelfth five-year plan for national drug safety" to strengthen the supervision of children's rational and safe drug use. Hubei CPPCC (3), 13–14.

Tatsumi, H., Senda, H., Yatera, S., Takemoto, Y., Yamayoshi, M., and Ohnishi, K. (1978). Toxicological studies on pipemidic acid. V. Effect on diarthrodial joints of experimental animals. J. Toxicol. Sci. 3 (4), 357–367. doi:10.2131/jts.3.357

Keywords: children, inappropriate prescribing, inappropriate prescription, potentially inappropriate medication, prescribing omission, screening tool

Citation: Li S, Huang L, Zeng L, Yu D, Jia Z-J, Cheng G and Zhang L (2022) A tool for screening potentially inappropriate prescribing in Chinese children. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1019795. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1019795

Received: 15 August 2022; Accepted: 12 October 2022;

Published: 31 October 2022.

Edited by:

Catherine M. T. Sherwin, Wright State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Natasa Duborija-Kovacevic, University of Montenegro, MontenegroCasey Sayre, Roseman University of Health Sciences, United States

Copyright © 2022 Li, Huang, Zeng, Yu, Jia, Cheng and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liang Huang, aGxpYW5nXzEwMjJAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Lingli Zhang, emhhbmdsaW5nbGlAc2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

Siyu Li

Siyu Li Liang Huang

Liang Huang Linan Zeng

Linan Zeng Dan Yu6

Dan Yu6