95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 22 October 2021

Sec. Ethnopharmacology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.758583

This article is part of the Research Topic Herbal Medicines in Pain Management, Volume I View all 8 articles

In South Africa, traditional medicine remains the first point of call for a significant proportion of the population seeking primary healthcare needs. This is particularly important for treating common conditions including pain and inflammation which are often associated with many disease conditions. This review focuses on the analysis of the trend and pattern of plants used for mitigating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South African folk medicine. An extensive search was conducted using various scientific databases and popular ethnobotanical literature focusing on South African ethnobotany. Based on the systematic analysis, 38 sources were selected to generate the inventory of 495 plants from 99 families that are considered as remedies for pain and inflammatory-related conditions (e.g., headache, toothache, backache, menstrual pain, and rheumatism) among different ethnic groups in South Africa. The majority (55%) of the 38 studies were recorded in three provinces, namely, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, and Western Cape. In terms of the number of mentions, the most popular plants used for pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa were Ricinus communis L. (10), Aloe ferox Mill. (8), Pentanisia prunelloides subsp. latifolia (Hochst.) Verdc. (8), Dodonaea viscosa Jacq var. angustifolia (L.f) Benth. (8), (L.) W.T.Aiton. (7) Ruta graveolens L. (7), and Solanum aculeastrum Dunal. (7). The top five plant families represented were Asteraceae (13%), Fabaceae (8%), Apocynaceae (4.3%), Asparagaceae (4%), and Lamiaceae (4%). An estimated 54% of the recorded plants were woody (trees and shrubs) in nature, while the leaves (27%) and roots (25%) were the most dominant plant parts. The use of plants for alleviating pain and inflammatory-related conditions remains popular in South African folk medicine. The lagging ethnobotanical information from provinces such as North West, Gauteng, and Free State remains a gap that needs to be pursued meticulously in order to have a complete country-wide database.

Inflammation is one of the most fundamental and pronounced protective reactions of an organism (Iwalewa et al., 2007; Medzhitov 2008; Kuprash and Nedospasov 2016; Kishore et al., 2019). It is regarded as a biological function which is triggered after the mechanical tissue disruption or from the responses by the presence of a physical, chemical, or biological agent in the body (Ahmed 2011; Ashley et al., 2012). Since ancient times, the complex and diverse patterns of inflammation development and their role in various (minor to major) disease conditions remain of great interest to researchers (Rocha e Silva 1978; Medzhitov 2008; Ashley et al., 2012; Bernstein et al., 2018; Hashemzaei et al., 2020). From a historical perspective (Rocha e Silva 1978), the main four signs of inflammation include redness (rubor), swelling (tumor), heat with (calor), and pain (dolor). In addition, the loss or disturbance of function (functio laesa) is considered the fifth sign (Kuprash and Nedospasov 2016). These aforementioned signs are considered as clinical signs of inflammation which are known to generally involve a sequence of events (Agyare et al., 2013). As a medical condition, pain is an enormous problem with an estimated 20% of adults suffering from this globally and 10% are newly diagnosed with chronic pain yearly (Goldberg and McGee 2011). Based on recent data (James et al., 2018), the Global Burden of Disease Study reaffirmed that the high prominence of pain and pain-related conditions remain the leading cause of disability and disease burden globally. From an epidemiological perspective, the importance of pain and related conditions cannot be overemphasized as it is known as a common, complex, and distressing problem that has a profound impact on individuals and society at large (Goldberg and McGee 2011; Mills et al., 2019).

Despite the existence of conventional drugs/medicines for pain, inflammation, and related conditions, the high risk of side effects and exorbitant cost remain a major deterrent to many people especially in developing and underdeveloped countries (Heinrich 2013; Sreekeesoon and Mahomoodally 2014; Bernstein et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2019; Daniyal and Wang 2021). On this basis, research on alternative approaches especially pharmacological interventions has remained pertinent (Daniyal and Wang 2021). In sub-Saharan Africa, the rich biodiversity and relatively high level of plant endemism often translate to great dependence on botanicals for therapeutic purposes (Moyo et al., 2015; Alebie et al., 2017; Aumeeruddy and Mahomoodally 2020; Van Wyk 2020). An estimate of 4,576–5,000 plant species has been used as food and for the treatment of various diseases (Agyare et al., 2013; Van Wyk 2020). The use of plant-based remedies for the mitigation of pain, inflammation, and related conditions remains popular among different ethnic groups (Stark et al., 2013; Oguntibeju 2018; Daniyal and Wang 2021). As a result, the need for further research on plants with anti-inflammatory activities cannot be overemphasized (Agyare et al., 2013; Heinrich 2013; Oguntibeju 2018; Adebayo and Amoo 2019; Elgorashi and McGaw 2019).

From an ethnobotanical/ethnopharmacological context, the primary data generated from field studies are the foundation towards exploring plant resources for novel bioactive entities and herbal medicine for different diseases (Heinrich et al., 2018; Yeung et al., 2020). The importance of such knowledge is well recognized as they can contribute to improving human health and the fight against diseases on local and global levels (Heinrich 2013; Popović et al., 2016). South Africa is culturally diverse and divided into nine provinces with an estimate of over 55 million people. Across the different ethnic groups, the value of traditional medicine and the importance of medicinal plants is well recognized (Van Wyk 2002; Van Staden 2008; Van Wyk 2011). Currently, only a few research groups in South Africa have focused on ethnobotanical surveys despite the fragile nature and rapid disappearance of indigenous knowledge systems associated with the rich plant biodiversity (Viljoen et al., 2019). The aim of the current review is to analyze the existing literature on ethnobotanical studies/surveys, books, and grey literature that focused on plants used for pain, inflammation, and related conditions in South Africa. In addition to generating baseline data for future pharmacological and phytochemical investigations, this appraisal of literature is expected to identify the existing knowledge gap(s) and serve as an important reference for future research in the field.

We conducted a detailed literature search by retrieving information from different scientific databases such as ScienceDirect, Scopus, and PubMed. The literature search (covering up till January 2021) was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2015). Keywords and phrases that were used included anti-inflammation, inflammation, pain, ethnobotany, ethnobotanical survey, and South Africa. These were used individually and in various combinations. In order to expand the generated data, we explored and included benchmark ethnobotanical books relevant to the South African context and which are currently available in the library of the North-West University, South Africa.

To generate the inventory/data for Table 1 and Table 2 as well as Supplementary Table S1, the inclusion criteria were that 1) the literature has ethnobotanical or ethnopharmacological context, and articles should be ethnobotanical field studies/surveys reporting on plant(s) with an indication as used for treating pain, inflammation, and related conditions, 2) the study location must be South Africa, 3) study must focus on plants, and 4) study must be written in English. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were 1) articles with no scientific plant names, 2) review articles, and 3) articles focusing on animals and other natural resources used for treating pain, inflammation, and related conditions.

TABLE 1. Overview of literature documenting the use of medicinal plants for managing and treating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa.

TABLE 2. Ethnobotanical information of plants used for mitigating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa. Botanical names were verified using PlantZAfrica (pza.sanbi.org) and South African National Biodiversity Institute website (http://newposa.sanbi.org/sanbi/Explore) as well as the World Flora Online (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/). The listed 87 plants had ≥3 mentions and the full list of 495 plants recorded in the current study is presented in Supplementary Table S1. *Common name: A, Afrikaans; E, English; K, Khoi; KS, Khoisan (Khoe-San), SS, Southern Sotho; SL, Sepulana; NS, Northern Sotho; TW, Twana; X, Xhosa; V, Vhenda; Z, Zulu. #Part used; ns, not specified; Nm, number of mentions/citations.

Following the exclusion of duplicates, citations in abstract form, and non-English citations, the titles/abstracts of full papers were screened for relevance to the scope of the current review (Figure 1). This task was initially conducted by the first author and confirmed by the second author. From each article, the following information was collected: scientific names, family, plant parts, method of preparation, and inflammation or related conditions treated.

FIGURE 1. Flow diagram for selection of articles/books/theses included in the systematic literature review for compiling data in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Given the importance and the need for accurate scientific nomenclature for plants (Rivera et al., 2014), all scientific names and families were validated in reference to PlantZAfrica (pza.sanbi.org), South African National Biodiversity Institute website (http://newposa.sanbi.org/sanbi/Explore), and the World Flora Online (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/). The synonyms and common names were retrieved from PlantZAfrica and South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) Red List of South African Plants (redlist.sanbi.org/species). Based on the reference database we used for the verification of the botanical names, we opted for the use of family names Asteraceae (PlantZAfrica), Fabaceae (PlantZAfrica, World Flora Online), and Xanthorrhoeaceae (World Flora Online) instead of Compositae, Leguminosae, and Asphodelaceae, respectively.

Several relevant internet search engines were mined for information relating to ethnobotanical documentation of plants used for treating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa in the past few decades. Despite the hits from the initial search, the majority were discarded for diverse reasons such as duplicates and being outside the predefined inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Based on the systematic search, 38 pieces of literature (books 29%, theses 10%, and articles 61%) were included as primary data as summarized in Table 1 and detailed in Supplementary Table S1. All the data were extracted from literature documenting general ethnobotanical surveys/studies.

Even though about 19% of the studies in the current review were missing specific provinces in South Africa, the majority were linked to KwaZulu-Natal (27%), Limpopo (16%), and Western Cape (14%) provinces (Figure 2). A similar pattern was observed in terms of the high quantity of the plants associated with the different locations. Recently, Ndhlovu et al. (2021) identified the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, and Limpopo provinces as regions with a high record of plants used for the management and treatment of childhood diseases in South Africa. Based on extensive bibliometric analysis of medicinal plant research in South Africa (Viljoen et al., 2019), KwaZulu-Natal was designated as one of the most research active provinces and considered as a “sweet-spot” which may be attributed to the rich plant heritage and indigenous knowledge practice among the Zulus that are the dominant ethnic group.

FIGURE 2. Distribution of literature and plants indicated as a remedy for pain and inflammatory-related conditions across provinces in South Africa. EC = Eastern Cape, FS = Free State, KZN = KwaZulu-Natal, LM = Limpopo, MP = Mpumalanga, NC = Northern Cape, and WC = Western Cape.

Evidence from the appraisal of ethnobotanical surveys has revealed the existing gaps across provinces and South African ethnic groups in terms of documenting plants (and associated indigenous knowledge) used for different conditions such as cancer (Twilley et al., 2020), malaria (Cock et al., 2019), childhood diseases (Ndhlovu et al., 2021), respiratory diseases (Cock and Van Vuuren 2020a, b), and animal diseases (McGaw et al., 2020).

Based on the 38 pieces of literature included in the current review, 495 plants are used for managing pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South African traditional medicine (Supplementary Table S1). Approximately 18% (87 plants) of the recorded plants had ≥3 mentions/citations suggesting their relative popularity as a remedy for pain and inflammatory-related conditions (Table 2). Particularly, Ricinus communis L. (10), Aloe ferox Mill. (8), Pentanisia prunelloides subsp. latifolia (Hochst.) Verdc. (8), Dodonaea viscosa Jacq var. angustifolia (L.f) Benth. (8), Gomphocarpus fruticosus (L.) W.T.Aiton. (7) Ruta graveolens L. (7), and Solanum aculeastrum Dunal. (7) were the top seven plants with the highest number of mentions/citations.

Symptoms such as swelling, disturbance of normal functions of different body parts, and pains are the hallmark of inflammations (Kuprash and Nedospasov 2016). Even though inflammation is often not a primary cause, it plays an important role in the development of many diseases which has resulted in more targeted efforts at suppressing inflammation as a means of improving clinical conditions (Hotamisligil 2006; Kuprash and Nedospasov 2016). In traditional medicine, healing is holistic in nature whereby symptoms are often the focus during treatment of many diseases (Iwalewa et al., 2007; Adebayo and Amoo 2019; Cock et al., 2019; Elgorashi and McGaw 2019; Twilley et al., 2020; Khumalo et al., 2021). This possibly accounted for the high number of plants prescribed for managing pains and inflammatory-related conditions (Supplementary Table S1). Apart from the use of the term “pain(s)” reliever associated with many of the identified plants, other widely mentioned conditions were headache (142), toothache (114), backache (80), abdominal pain (17), menstrual/period pains (27), rheumatism (78), stomachache (64), swelling/inflammation (113), and sprain (14).

Apart from the use of a single plant, a combination of plants was common for treating pain and inflammation-related conditions. Some examples involved the combination of Athrixia phylicoides DC. and Athrixia elata Sond. as decoctions for relieving sore feet (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk 1962). Brackenridgea zanguebarica powdered roots are rubbed on after treatment with Aloe chabaudii Schönland to relieve swollen ankles (Arnold and Gulumian 1984). As recorded by Bryant (1966), the root decoction of Gunnera perpensa L. is used in conjunction with other plants such as Alepidea amatymbica Eckl. & Zeyh. and Crinum species as a remedy for pain in rheumatic fever and stomachache. This phenomenon of combining two or more plants for treating different diseases conditions has been well demonstrated in African traditional medicine (Alebie et al., 2017; Ahmed et al., 2018). Apart from the combination with other plants, Bhat (2014) indicated that Aloe arborescens Mill. leaves are mixed with chicken feed as anti-inflammatory herb among the indigenous people of Eastern Cape, South Africa.

In terms of preparation, decoctions and infusions were the dominant methods used for preparing the plants used for treating pain and inflammatory-related conditions (Supplementary Table S1). These aforementioned methods are generally regarded as the most common preparation methods in traditional medicine as evident in recent studies (Boadu and Asase 2017; Alamgeer et al., 2018; Masondo et al., 2019; Aumeeruddy and Mahomoodally 2020; Ndhlovu et al., 2021). When compared to other preparation methods, the relatively shorter duration required for making medicinal plant decoctions is surely the desired benefit (Aumeeruddy and Mahomoodally 2020). Despite the popularity of decoctions and infusions, variations (e.g., duration of boiling, types, and volume of solvents) often exist in their preparations among traditional healers and locations, which remain a concern for standardization and reproducibility (Boadu and Asase 2017). Other methods of preparation and application have been recorded for mitigating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa. For instance, the application of leaf as a compress remains common among different ethnic groups for pain and backache (Supplementary Table S1). Particularly, warm leaves of Ricinus communis L. are wrapped around the stomach as a remedy for stomachache (Mbanjwa 2020). In addition, fresh leaves of Centella asiatica Urb. are used as ear plugs to relieve ear pain (Van Wyk et al., 2008) while dried ground root-bark of Zanthoxylum capense (Thunb.) Harv. is directly applied for toothache (Hutchings et al., 1996).

Other trends observed were the variations in the use of specific plants for children relative to adults and on the basis of gender (Supplementary Table S1). Infusion made from the bark of Berchemia zeyheri (Sond.) Grubov. is administered as enemas for pains and for rectal ulceration in children (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk 1962). Whole plant decoction made from Acanthospermum hispidum DC. and warm leaves of Ricinus communis L. is used to treat stomachache in children (Bhat 2013; Mbanjwa 2020). Asparagus laricinus Burch. and Berkheya bipinnatifida (Harv.) Roessler is known as an effective remedy for different types of pains in children among the Zulus (Mhlongo and Van Wyk 2019). In Limpopo, Rhoicissus tridentata (L.f.) Wild & R.B.Drumm. powdered roots are added to porridge to relieve stomach pain in children (Arnold and Gulumian 1984). Maceration of the powdered roots of Cassine transvaalensis (Burtt Davy) Codd is drunk to relieve stomachache in male (Arnold and Gulumian 1984). Evidence from the current review revealed that several plants (e.g., Aloe arborescens Mill, Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd., Chironia baccifera L., Gnidia capitata L.f., Mentha spicata L., and Pelargonium hypoleucum Turcz.) are frequently used for relieving menstrual pains in females (Hutchings et al., 1996; Philander 2011; Nortje and Van Wyk 2015; Mbanjwa 2020). However, the cultural implications and explanations for these significant observations are not explicitly documented.

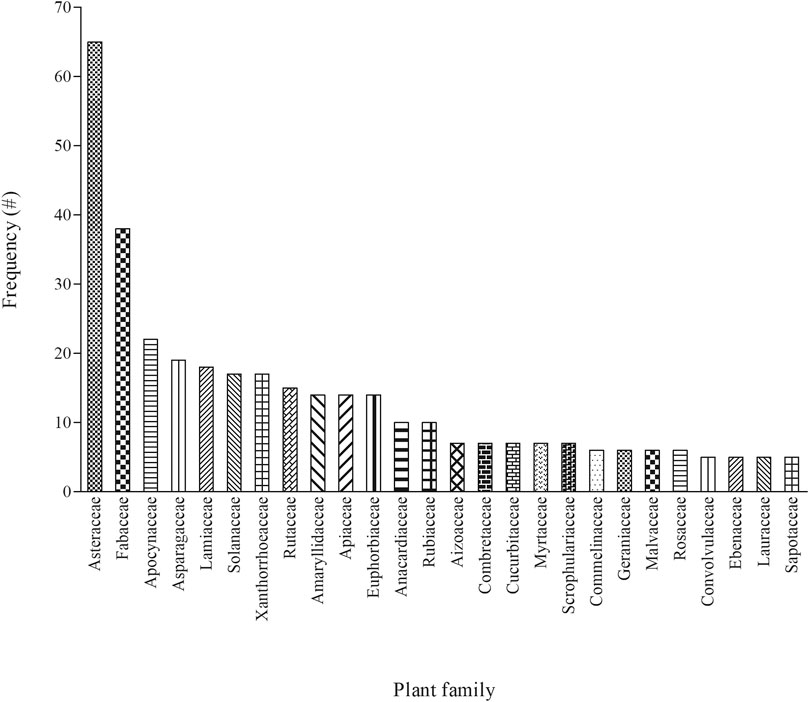

The 495 recorded plants were distributed into 99 families with Asteraceae (13%), Fabaceae (8%), Apocynaceae (4.3%), Asparagaceae (4%), and Lamiaceae (4%) having the highest number of plant species. Other highly represented families included Xanthorrhoeaceae, Solanaceae, Rutaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Apiaceae, and Amaryllidaceae (Figure 3). The majority of these aforementioned families remain dominant in African traditional medicinal flora (Van Wyk 2020). On the other hand, 64 of the 99 families (e.g., Acanthaceae, Araceae, Brassicaceae, Clusiaceae, Ruscaceae, and Portulacaceae) were poorly represented having an average of 1–2 plants per family (Supplementary Table S1). The high utilization of plant families such as Fabaceae and Asteraceae in folk medicinal flora has been well pronounced for different disease conditions. For instance, a detailed review of ethnobotanical surveys revealed that Asteraceae is the most cited family used for treating childhood diseases in South Africa (Ndhlovu et al., 2021), medical ethnobotany of Lesotho (Moteetee and Van Wyk 2011), medicinal plants used as blood purifiers in southern Africa (van Vuuren and Frank 2020), and managing respiratory infections and related symptoms in South Africa (Semenya and Maroyi 2018; Cock and Van Vuuren 2020a) as well as in Pakistan (Alamgeer et al., 2018).

FIGURE 3. Distribution of families with five or more plants (n ≥ 5) indicated as a remedy for pain and inflammatory-related conditions among different ethnic groups in South Africa, # = number of mentions.

Fabaceae is regarded as the most dominant plant family used for treating malaria in Ethiopia (Alebie et al., 2017). Based on Moerman’s approach, Muleba et al. (2021) identified Fabaceae as the overutilized families for medicinal purpose in Mpumalanga province of South Africa. Following a detailed family-level floristic analysis of medicinal plants, the African folk medicine is dominated by Fabaceae, Asteraceae, and Rubiaceae, which are considered as the top three dominant families in African medicinal flora (Van Wyk 2020). In the current review, both Asteraceae and Fabaceae accounted for approximately 21% (102) of the plants used for treating pain and inflammatory-related conditions in South Africa (Figure 3). As one of the largest plant families globally, the high abundance (about 32 913 species) and distribution of the Asteraceae probably translate to higher availability and utilization as medicinal flora in African folk medicine (Van Wyk 2020). Given that some members of the Asteraceae occur as weeds and early colonisers in fields especially after anthropogenic activities (Daehler 1998), this may be responsible for the ease of access and availability especially in home garden as medicine among local communities (Alamgeer et al., 2018). In addition, the presence of therapeutic chemicals such as alkaloids and terpenoids has been proposed as the driving factor for the utilization of families such as Fabaceae and Apocynaceae in folk medicine (Van Wyk 2020).

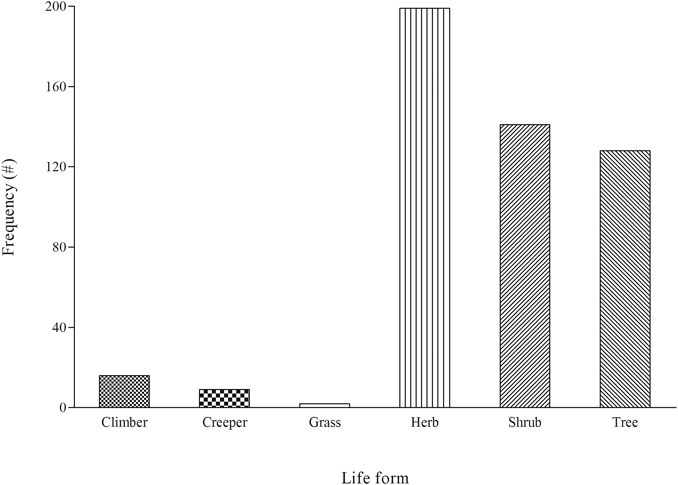

In terms of life-form, approximately 54% of the recorded plants were woody consisting of trees and shrubs while herbs contributed 40% (Figure 4), a similar pattern with the dominance of woody plants and herbs in South African traditional medicine (Maroyi 2017; Asong et al., 2019). Given the wide variation in rainfall patterns in South Africa (Kruger and Nxumalo 2017), the type and life-form of plants occurring across the different ecological zones are predictable. Furthermore, the presence and occurrence of the plant species often determine their utilization for medicinal and other purposes among local communities (Muleba et al., 2021).

FIGURE 4. An overview of life-form for plants indicated as a remedy for pain and inflammatory-related conditions among different ethnic groups in South Africa, # = number of mentions.

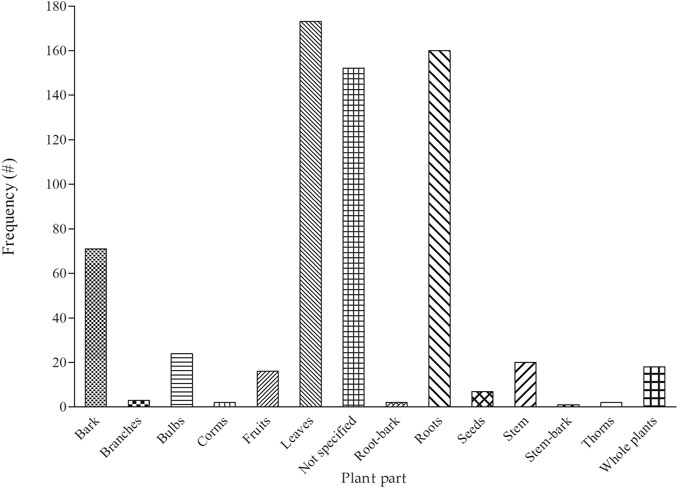

In many instances, more than one part of the 495 recorded plants were used for the treatment of pain and inflammatory-related conditions (Supplementary Table S1). Even though there were significant cases (24%) whereby the authors did not identify plant parts, more than 10 different parts were generated in the current review (Figure 5). Among the identified plant parts, the leaves (27%), roots (25%), and bark (11%) were the most dominant while the use of seeds, branches, corms, stem-bark, root-bark, and thorns was generally limited (<2%). The current observation whereby the leaves were the dominant plant part remains a common pattern as evident in the recent appraisal of ethnobotanical surveys in southern Africa (Semenya and Maroyi 2018; Ndhlovu et al., 2021). Particularly, the leaves were the most frequently used plant part for the treatment of bacterial (Cock and Van Vuuren 2020a) and viral (Cock and Van Vuuren 2020b) respiratory infections across the traditional southern African healing systems. On a global scale, Aumeeruddy and Mahomoodally (2020) identified leaves as the most used plant part in the management of hypertension in traditional medicine. The general popularity of the leaves with respect to other plant parts may be related to ease of access and high abundance in many communities (Maroyi 2017; Aumeeruddy and Mahomoodally 2020). From a conservation perspective (Moyo et al., 2015), the preference of leaves and other aerial parts of the plants for medicinal purposes is advantageous and often strongly recommended. When compared to other plant parts such as roots and bark, the leaves regenerate faster and exert lesser strain on local populations of important medicinal plants (Alebie et al., 2017). As a result, different conservation strategies especially plant-part substitution (e.g., leaves instead of roots and bark) have been often suggested to stakeholders (Lewu et al., 2006; Moyo et al., 2015).

FIGURE 5. Distribution of plant parts indicated as a remedy for pain and inflammatory-related conditions among different ethnic groups in South Africa, # = number of mentions.

Based on the large number (495) of plants recorded, it is evident that their utilization for managing pain and inflammatory-related conditions remains a common practice in South African folk medicine. An estimated 18% (87 of the 495) of the recorded plants are relatively well known given that they were mentioned by three or more sources in South Africa. The recorded plants were utilized among the different ethnic groups for a wide range of conditions especially pains, headache, toothache, and backache. We observed that some of the plants recorded in the current study are strictly prescribed based on gender and age (children versus adults). In some cases, we observed that important information such as the plant part utilized, preparation methods, and recipes for a significant portion of identified plants were missing in the existing literature. This underscores the limited value of the existing fragmented nature of the ethnobotanical surveys in South Africa. In order to mitigate these challenges, adherence to the established guidelines and robust ethnobotanical research methodology remains essential for the development of a holistic inventory relating to remedies used for pain and inflammatory-related conditions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

AOA and SCP were involved with the conceptualization of the study. AOA prepared the draft manuscript with input from SCP. Both authors agree to the submission of the final manuscript.

AOA acknowledges the financial support from the National Research Foundation (NRF Grant no: UID 120488 and UID116343) and the North-West University UCDG: Staff Development–Advancement of Research Profiles: Mobility Grant (NW 1EU0130) for outgoing academic visits. The Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, North-West University, provided the article processing fee.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank the North-West University and the University of KwaZulu-Natal for institutional support.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.758583/full#supplementary-material

Adebayo, S. A., and Amoo, S. O. (2019). South African Botanical Resources: A Gold Mine of Natural Pro-inflammatory Enzyme Inhibitors. South Afr. J. Bot. 123, 214–227. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.03.020

Agyare, C., Obiri, D. D., Boakye, Y. D., and Osafo, N. (2013). “Anti-inflammatory and Analgesic Activities of African Medicinal Plants,” in Medicinal Plant Research in Africa. Editor V. Kuete (Oxford, UK: Elsevier), 725–752. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-405927-6.00019-9

Ahmed, A. U. (2011). An Overview of Inflammation: Mechanism and Consequences. Front. Biol. 6, 274. doi:10.1007/s11515-011-1123-9

Ahmed, S. M., Nordeng, H., Sundby, J., Aragaw, Y. A., and de Boer, H. J. (2018). The Use of Medicinal Plants by Pregnant Women in Africa: A Systematic Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 224, 297–313. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.032

Alamgeer, , Younis, W., Asif, H., Sharif, A., Riaz, H., Bukhari, I. A., et al. (2018). Traditional Medicinal Plants Used for Respiratory Disorders in Pakistan: A Review of the Ethno-Medicinal and Pharmacological Evidence. Chin. Med. 13, 48. doi:10.1186/s13020-018-0204-y

Alebie, G., Urga, B., and Worku, A. (2017). Systematic Review on Traditional Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Malaria in Ethiopia: Trends and Perspectives. Malar. J. 16, 307. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-1953-2

Arnold, H. J., and Gulumian, M. (1984). Pharmacopoeia of Traditional Medicine in Venda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 12, 35–74. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(84)90086-2

Ashley, N. T., Weil, Z. M., and Nelson, R. J. (2012). Inflammation: Mechanisms, Costs, and Natural Variation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43, 385–406. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-040212-092530

Asong, J. A., Ndhlovu, P. T., Khosana, N. S., Aremu, A. O., and Otang-Mbeng, W. (2019). Medicinal Plants Used for Skin-Related Diseases Among the Batswanas in Ngaka Modiri Molema District Municipality, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 126, 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.05.002

Aston Philander, L. (2011). An Ethnobotany of Western Cape Rasta bush Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 138, 578–594. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.004

Aumeeruddy, M. Z., and Mahomoodally, M. F. (2020). Traditional Herbal Therapies for Hypertension: A Systematic Review of Global Ethnobotanical Field Studies. South Afr. J. Bot. 135, 451–464. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2020.09.008

Bernstein, N., Akram, M., Daniyal, M., Koltai, H., Fridlender, M., and Gorelick, J. (2018). “Antiinflammatory Potential of Medicinal Plants: A Source for Therapeutic Secondary Metabolites,” in Advances in Agronomy. Editor D. Sparks (Academic Press). doi:10.1016/bs.agron.2018.02.003

Bhat, R. B., and Jacobs, T. V. (1995). Traditional Herbal Medicine in Transkei. J. Ethnopharmacol. 48, 7–12. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01276-j

Bhat, R. B. (2014). Medicinal Plants and Traditional Practices of Xhosa People in the Transkei Region of Eastern Cape, South Africa. Indian J. Traditional Knowledge 13, 292–298.

Bhat, R. B. (2013). Plants of Xhosa People in the Transkei Region of Eastern Cape (South Africa) with Major Pharmacological and Therapeutic Properties. J. Med. Plants Res. 7, 1474–1480.

Boadu, A. A., and Asase, A. (2017). Documentation of Herbal Medicines Used for the Treatment and Management of Human Diseases by Some Communities in Southern Ghana. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 30430. doi:10.1155/2017/3043061

Bruce, W. (1975). Bruce Chalmers Commended for Materials Research. Phys. Today 28, 57–58. doi:10.1063/1.3069076

Cock, I. E., Selesho, M. I., and Van Vuuren, S. F. (2019). A Review of the Traditional Use of Southern African Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Malaria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 245, 112176. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112176

Cock, I. E., and Van Vuuren, S. F. (2020a). The Traditional Use of Southern African Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Bacterial Respiratory Diseases: A Review of the Ethnobotany and Scientific Evaluations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 263, 113204. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113204

Cock, I. E., and Van Vuuren, S. F. (2020b). The Traditional Use of Southern African Medicinal Plants in the Treatment of Viral Respiratory Diseases: A Review of the Ethnobotany and Scientific Evaluations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 262, 113194. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113194

Coopoosamy, R. M., and Naidoo, K. K. (2012). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Durban, South Africa. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 6.116, 818818–823823. doi:10.5897/ajpp11.700

Corrigan, B. M., Van Wyk, B.-E., Geldenhuys, C. J., and Jardine, J. M. (2011). Ethnobotanical Plant Uses in the KwaNibela Peninsula, St Lucia, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 77, 346–359. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2010.09.017

Cumes, D., Loon, R., and Bester, D. (2009). Healing Trees & Plants of the Lowveld. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Nature.

Daehler, C. C. (1998). The Taxonomic Distribution of Invasive Angiosperm Plants: Ecological Insights and Comparison to Agricultural Weeds. Biol. Conserv. 84, 167–180. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(97)00096-7

Daniyal, M., and Wang, W. (2021). “Molecular Pharmacology of Inflammation: Medicinal Plants as Antiinflammatory Agents,” in Inflammation and Natural Products. Editors S. Gopi, A. Amalraj, A. Kunnumakkara, and S. Thomas (Academic Press), 21–63. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-819218-4.00005-5

De Beer, J. J. J., and Van Wyk, B.-E. (2011). An Ethnobotanical Survey of the Agter-Hantam, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 77, 741–754. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2011.03.013

Iwalewa, E. O., McGaw, L. J., Naidoo, V., and Eloff, J. N. (2007). Inflammation: the Foundation of Diseases and Disorders. A Review of Phytomedicines of South African Origin Used to Treat Pain and Inflammatory Conditions. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 6, 2868–2885. doi:10.5897/ajb2007.000-2457

Elgorashi, E. E., and McGaw, L. J. (2019). African Plants with In Vitro Anti-inflammatory Activities: A Review. South Afr. J. Bot. 126, 142–169. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.06.034

Forbes, V. S. (1986). Carl Peter Thunberg Travels at the Cape of Good Hope 1772–1775. Cape Town, South Africa: Van Riebeeck Society. ISBN: 0620109815.

Gebashe, F., Moyo, M., Aremu, A. O., Finnie, J. F., and Van Staden, J. (2019). Ethnobotanical Survey and Antibacterial Screening of Medicinal Grasses in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 467–474. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.07.027

Gerstner, J. (1941). A Preliminary Check List of Zulu Names of Plants. Bantu Stud. 15, 277–301. doi:10.1080/02561751.1941.9676141

Goldberg, D. S., and McGee, S. J. (2011). Pain as a Global Public Health Priority. BMC Public Health 11, 770. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-770

Hashemzaei, M., Mamoulakis, C., Tsarouhas, K., Georgiadis, G., Lazopoulos, G., Tsatsakis, A., et al. (2020). Crocin: A Fighter against Inflammation and Pain. Food Chem. Toxicol. 143, 111521. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2020.111521

Heinrich, M., Lardos, A., Leonti, M., Weckerle, C., Willcox, M., Applequist, W., et al. (2018). Best Practice in Research: Consensus Statement on Ethnopharmacological Field Studies - ConSEFS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 211, 329–339. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.015

Heinrich, M. (2013). Ethnopharmacology and Drug Discovery. Compr. Nat. Prod. 3, 351–381. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-409547-2.02773-6

Hotamisligil, G. S. (2006). Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders. Nature 444, 860–867. doi:10.1038/nature05485

Hulley, I. M., and Van Wyk, B.-E. (2019). Quantitative Medicinal Ethnobotany of Kannaland (Western Little Karoo, South Africa): Non-homogeneity Amongst Villages. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 225–265. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.03.014

Hutchings, A., Scott, A. H., Lewis, G., and Cunningham, A. (1996). Zulu Medicinal Plants. An Inventory. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press.

James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., et al. (2018). Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990-2017: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Khumalo, G. P., Van Wyk, B. E., Feng, Y., and Cock, I. E. (2021). A Review of the Traditional Use of Southern African Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Inflammation and Inflammatory Pain. J. Ethnopharmacol., 114436. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114436

Kishore, N., Kumar, P., Shanker, K., and Verma, A. K. (2019). Human Disorders Associated with Inflammation and the Evolving Role of Natural Products to Overcome. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 179, 272–309. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.034

Kruger, A. C., and Nxumalo, M. P. (2017). Historical Rainfall Trends in South Africa: 1921-2015. Wsa 43, 285–297. doi:10.4314/wsa.v43i2.12

Kuprash, D. V., and Nedospasov, S. A. (2016). Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Inflammation. Biochemistry (Mosc) 81, 1237–1239. doi:10.1134/S0006297916110018

Lewu, F. B., Grierson, D. S., and Afolayan, A. J. (2006). The Leaves of Pelargonium Sidoides May Substitute for its Roots in the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Biol. Conservation 128, 582–584. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.10.018

Mabogo, D. E. N. (1990). The Ethnobotany of the Vhavenda. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria.

Mahwasane, S. T., Middleton, L., and Boaduo, N. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Indigenous Knowledge on Medicinal Plants Used by the Traditional Healers of the Lwamondo Area, Limpopo Province, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 88, 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2013.05.004

Maroyi, A. (2017). Diversity of Use and Local Knowledge of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 43. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0173-8

Masondo, N. A., Stafford, G. I., Aremu, A. O., and Makunga, N. P. (2019). Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors from Southern African Plants: An Overview of Ethnobotanical, Pharmacological Potential and Phytochemical Research Including and beyond Alzheimer's Disease Treatment. South Afr. J. Bot. 120, 39–64. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.09.011

Mbanjwa, S. G. (2020). A Quantitative Ethnobotanical Survey of the Ixopo Area of KwaZulu-Natal, South. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Johannesburg.

McGaw, L. J., Famuyide, I. M., Khunoana, E. T., and Aremu, A. O. (2020). Ethnoveterinary Botanical Medicine in South Africa: A Review of Research from the Last Decade (2009 to 2019). J. Ethnopharmacol. 257, 112864. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.112864

Medzhitov, R. (2008). Origin and Physiological Roles of Inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435. doi:10.1038/nature07201

Mhlongo, L. S., and Van Wyk, B.-E. (2019). Zulu Medicinal Ethnobotany: New Records from the Amandawe Area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 266–290. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.02.012

Mills, S. E. E., Nicolson, K. P., and Smith, B. H. (2019). Chronic Pain: a Review of its Epidemiology and Associated Factors in Population-Based Studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 123, e273–e283. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023

Mintsa Mi Nzue, A. P. (2009). Use and Conservation Status of Medicinal Plants in the Cape Peninsula, Western Cape Province of South Africa. Stellenbosch, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch.

Mogale, M. M. P., Raimondo, D. C., and Van Wyk, B.-E. (2019). The Ethnobotany of Central Sekhukhuneland, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 90–119. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.01.001

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. PRISMA- P. Group (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 4, 1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Mokganya, M. G., and Tshisikhawe, M. P. (2019). Medicinal Uses of Selected Wild Edible Vegetables Consumed by Vhavenda of the Vhembe District Municipality, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 184–188. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.09.029

Mongalo, N. I., and Makhafola, T. J. (2018). Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Lay People of Blouberg Area (Pedi Tribe), Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 14, 46. doi:10.1186/s13002-018-0245-4

Moteetee, A., and Van Wyk, B. E. (2011). The Medical Ethnobotany of Lesotho: A Review. Bothalia 41, 209–228. doi:10.4102/abc.v41i1.52

Moyo, M., Aremu, A. O., and Van Staden, J. (2015). Medicinal Plants: An Invaluable, Dwindling Resource in Sub-saharan Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 174, 595–606. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.034

Muleba, I., Yessoufou, K., and Rampedi, I. T. (2021). Testing the Non-random Hypothesis of Medicinal Plant Selection Using the Woody flora of the Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 4162–4173. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00763-5

Ndhlovu, P. T., Omotayo, A. O., Otang-Mbeng, W., and Aremu, A. O. (2021). Ethnobotanical Review of Plants Used for the Management and Treatment of Childhood Diseases and Well-Being in South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 137, 197–215. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2020.10.012

Nortje, J. M., and Van Wyk, B. E. (2015). Medicinal Plants of the Kamiesberg, Namaqualand, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 171, 205–222. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.049

Oguntibeju, O. O. (2018). Medicinal Plants with Anti-inflammatory Activities from Selected Countries and Regions of Africa. J. Inflamm. Res. 11, 307–317. doi:10.2147/JIR.S167789

Polori, K. L., Mashele, S. S., Madamombe-Manduna, I., and Semenya, S. S. (2018). Ethno-medical Botany and Some Biological Activities of Ipomoea oblongata Collected in the Free State Province, South Africa. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 441–449.

Pooley, E. (1993). The Complete Field Guide to Trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei. 1st edition. Durban, South Africa: Natal Flora Publications Trust.

Popović, Z., Matić, R., Bojović, S., Stefanović, M., and Vidaković, V. (2016). Ethnobotany and Herbal Medicine in Modern Complementary and Alternative Medicine: An Overview of Publications in the Field of I&C Medicine 2001-2013. J. Ethnopharmacol. 181, 182–192. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.01.034

Pujol, J. (1990). NaturAfrica: The Herbalist Handbook: African Flora, Medicinal Plants. Durban, South Africa: Natural Healers' Foundation.

Rivera, D., Allkin, R., Obón, C., Alcaraz, F., Verpoorte, R., and Heinrich, M. (2014). What is in a Name? the Need for Accurate Scientific Nomenclature for Plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 152, 393–402. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.022

Rocha e Silva, M. (1978). A Brief Survey of the History of Inflammation. Agents Actions 8, 45–49. doi:10.1007/BF01972401

Semenya, S. S., and Maroyi, A. (2018). Data on Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Respiratory Infections and Related Symptoms in South Africa. Data Brief 21, 419–423. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2018.10.012

Shai, K. N., Ncama, K., Ndhlovu, P. T., Struwig, M., and Aremu, A. O. (2020). An Exploratory Study on the Diverse Uses and Benefits of Locally-Sourced Fruit Species in Three Villages of Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Foods 9, 1581. doi:10.3390/foods9111581

Sreekeesoon, D. P., and Mahomoodally, M. F. (2014). Ethnopharmacological Analysis of Medicinal Plants and Animals Used in the Treatment and Management of Pain in Mauritius. J. Ethnopharmacol. 157, 181–200. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030

Stark, T. D., Mtui, D. J., and Balemba, O. B. (2013). Ethnopharmacological Survey of Plants Used in the Traditional Treatment of Gastrointestinal Pain, Inflammation and Diarrhea in Africa: Future Perspectives for Integration into Modern Medicine. Animals (Basel) 3, 158–227. doi:10.3390/ani3010158

Thring, T. S., and Weitz, F. M. (2006). Medicinal Plant Use in the Bredasdorp/Elim Region of the Southern Overberg in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 103, 261–275. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.013

Tshikalange, T. E., Mophuting, B. C., Mahore, J., Winterboer, S., and Lall, N. (2016). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used in Villages under Jongilanga Tribal council, Mpumalanga, South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 13, 83–89. doi:10.21010/ajtcam.v13i6.13

Twilley, D., Rademan, S., and Lall, N. (2020). A Review on Traditionally Used South African Medicinal Plants, Their Secondary Metabolites and Their Potential Development into Anticancer Agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 261, 113101. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113101

Van Staden, J. (2008). Ethnobotany in South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 119, 329–330. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.003

Van Vuuren, S., and Frank, L. (2020). Review: Southern African Medicinal Plants Used as Blood Purifiers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 249, 112434. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112434

Van Wyk, B.-E., de Wet, H., and Van Heerden, F. R. (2008). An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in the southeastern Karoo, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 74, 696–704. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2008.05.001

Van Wyk, B.-E., and Gericke, N. (2000). People's Plants: A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications.

Van Wyk, B.-E. (2011). The Potential of South African Plants in the Development of New Medicinal Products. South Afr. J. Bot. 77, 812–829. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2011.08.011

Van Wyk, B.-E., Van Oudtshoorn, B., and Gericke, N. (1997). Medicinal Plants of South Africa. First edition. Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications.

Van Wyk, B.-E. (2002). A Review of Ethnobotanical Research in Southern Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 68, 1–13. doi:10.1016/s0254-6299(15)30433-6

Van Wyk, B. E. (2020). A Family-Level Floristic Inventory and Analysis of Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional African Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 249, 112351. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112351

Viljoen, A., Sandasi, M., and Vermaak, I. (2019). The Role of the South African Journal of Botany as a Vehicle to Promote Medicinal Plant Research- A Bibliometric Appraisal. South Afr. J. Bot. 122, 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.07.024

Watt, J. M., and Breyer-Brandwijk, M. G. (1962). The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa. 2nd edition. London, UK: Livingstone.

Keywords: ethnobotanical survey, folk medicine, headache, indigenous knowledge, rheumatism

Citation: Aremu AO and Pendota SC (2021) Medicinal Plants for Mitigating Pain and Inflammatory-Related Conditions: An Appraisal of Ethnobotanical Uses and Patterns in South Africa. Front. Pharmacol. 12:758583. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.758583

Received: 14 August 2021; Accepted: 13 September 2021;

Published: 22 October 2021.

Edited by:

Yu Chiang Hung, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, TaiwanReviewed by:

Airy Gras, Instituto Botánico de Barcelona, SpainCopyright © 2021 Aremu and Pendota. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adeyemi O. Aremu, T2xhZGFwby5BcmVtdUBud3UuYWMuemE=, QXJlbXVhQHVrem4uYWMuemE=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.