95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Pharmacol. , 08 October 2021

Sec. Drugs Outcomes Research and Policies

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.755052

Lucia Gozzo1,2*

Lucia Gozzo1,2* Giovanni Luca Romano2

Giovanni Luca Romano2 Francesca Romano2

Francesca Romano2 Serena Brancati1

Serena Brancati1 Laura Longo1

Laura Longo1 Daniela Cristina Vitale1

Daniela Cristina Vitale1 Filippo Drago1,2,3

Filippo Drago1,2,3Even for centrally approved products, each European country is responsible for the effective national market access. This step can result in inequalities in terms of access, due to different opinions about the therapeutic value assessed by health technology assessment (HTA) bodies. Advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) represent a major issue with regard to the HTA in order to make them available at a national level. These products are based on genes, tissues, or cells, commonly developed as one-shot treatment for rare or ultrarare diseases and mandatorily authorized by the EMA with a central procedure. This study aims to provide a comparative analysis of HTA recommendations issued by European countries (France, Germany, and Italy) following EMA approval of ATMPs. We found a low rate of agreement on the therapeutic value (in particular the “added value” compared to the standard of care) of ATMPs. Despite the differences in terms of clinical assessment, the access has been usually guaranteed, even with different timing and limitations. In view of the importance of ATMPs as innovative therapies for unmet needs, it is crucial to understand and act on the causes of disagreement among the HTA. In addition, the adoption of the new EU regulation on HTA would be useful to reduce disparities of medicine’s assessment among European countries.

The centralized procedure adopted by the European Union (EU) and mandatory for some drugs category since 2004 (The Council of the European Communitie, 1993; European Parliament, Council of the European Union, 2001; European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2004) enables a rapid, EU-wide authorization of medicinal products based on a benefit/risk assessment, which requires the evaluation of quality, nonclinical, and clinical data on safety and efficacy submitted by the applicant. Once granted by the EU Commission, the centralized marketing authorization (MA) is valid in all member states. However, despite the unification of the procedures for drug approval, each country is responsible for an effective national market access, which needs the pricing and reimbursement decision to be adopted.

This can result in patient access inequalities among European countries, due to differences in terms of willingness to pay and opinion about the therapeutic value assessed by health technology assessment (HTA) bodies.

Generally, the HTA evaluates the added therapeutic benefits and risks for covering a new technology in the context of local standard of care (van Nooten et al., 2012), based on clinical (efficacy and safety), economic, ethical, and organizational aspects in support of policy decision-making about price and reimbursement decisions (Angelis et al., 2018). The heterogeneity of HTA recommendations, thereafter probably reflected in national reimbursement decisions and pricing agreements, is related to differences in assessment methodologies and health-care systems’ organization but also to the available evidence and, above all, willingness to accept uncertainty (Jommi et al., 2020).

Indeed, MA is increasingly granted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) at earlier stages, especially for a high unmet medical need and/or rare diseases, through an accelerated assessment or conditional marketing authorization (CMA) before complete efficacy and safety data are available, thus potentially leading to limitations of evidence needed for the subsequent HTA process (Akehurst et al., 2017; Richardson and Schlander, 2019).

Acceleration of drug approval might therefore not always translate into positive and rapid patient access due to the uncertainties about the clinical benefits and the expected high impact on the health-care system (Ciani and Jommi, 2014; Akehurst et al., 2017; Allen et al., 2017).

Advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) represent one of the clearest examples of issues for HTA (Drummond et al., 2019; Jönsson et al., 2019). These products are medicines for human use based on genes, tissues, or cells, commonly developed as one-shot treatment for rare or ultrarare diseases. The use of the centrally authorized procedure is compulsory for these innovative medicines. Due to the lack of well-designed clinical trials in terms of the number of patients enrolled, comparator, and long-term clinical data, frequently incomplete evidence is available to determine their value (Hettle et al., 2017).

The uncertainty is enhanced by their high cost which make the pricing and reimbursement decisions challenging (Garrison et al., 2019), with concerns about the affordability of health-care systems (Seoane-Vazquez et al., 2019). Moreover, even ATMP management and administration is complex and requires a clear definition of specialized centers and a proper funding (Ronco et al., 2021).

Several ATMPs have been licensed over the last decade, and the number of ATMPs reaching the market is expected to grow (Quinn et al., 2019), being hundreds in development, across numerous indications.

This study aimed to provide a comparative analysis of HTA recommendations issued by European countries following EMA approval of ATMPs.

The study included the following steps:

1). Identification of approved advanced therapies in Europe between 2015 and 2020;

2). Identification of the reimbursement status and the HTA of ATMPs currently approved in Europe by the EMA performed by EU national authorities (France, Germany, and Italy); selection of countries was based on the availability of assessments for public consultation and on the clear definition of therapeutic values through comparable rating scales;

3). Comparative analysis of national opinions; available HTA reports and official administrative act of the three EU countries have been analyzed to compare ATMP assessments.

ATMPs centrally approved by the EMA have been identified by consulting the agency’s official documents and classified by type (gene therapy, cell therapy, and engineered tissues), according to the orphan drug designation, by type of authorization issued by the EMA (full, conditional, and for exceptional circumstances), and by therapeutic area (rare diseases, oncology, and others).

For each ATMP, pivotal clinical trials were reviewed, analyzing the study design, the number of patients enrolled, the primary and secondary outcomes, and the main study results.

The level of clinical benefit (Service Médical Rendu—SMR) and the added therapeutic value compared to the available therapeutic alternatives (Amélioration du Service Médical Rendu—ASMR) was extracted from the official HTA documentation resulting from the assessment of the Transparency Committee (TC) of the French National Authority (Haute Autorité de santé—HAS) (Santè, 2013; Santè, 2014).

With regard to Germany, we consulted the reports of the competent national bodies (Federal Joint Committee or Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, G-BA and Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, IQWIG) containing a complete HTA on the additional therapeutic benefit of the product compared to recognized standard therapies (Bundesausschuss, 2010).

Finally, we identified the therapeutic need, the added therapeutic value, and the quality of the evidence from the innovation assessment reports published by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) (AIFA, 2017). A direct comparison among national opinions was possible in terms of an “added therapeutic value,” a measure included in all the available assessments (Supplementary Figure S1).

Currently, 12 ATMPs have been authorized in Europe (nine gene therapies, one cell therapy, and two engineered tissues) for 13 therapeutic indications between 2015 and 2020 (Supplementary Table S1). The MA for five additional products has been withdrawn. Ten out of 12 medicines received orphan designation, including three indicated for onco-hematologic diseases and five for genetic rare diseases. Tecartus®, Zolgensma®, Zynteglo®, and Holoclar® received a conditional approval, whereas Tecartus®, Libmeldy®, and Zynteglo® underwent an accelerated assessment (Table 1).

In general, at the time of EMA approval, only data from open-label, single-arm, and phase I/II trials were available (Table 2), whereas data from concluded phase III, randomized, and controlled clinical trials were submitted for Luxturna®, Alofisel®, Spherox®, and Imlygic®. The median number of patients enrolled in these studies was 29 (range 1–436), followed for a median of 36 months (range 12–104).

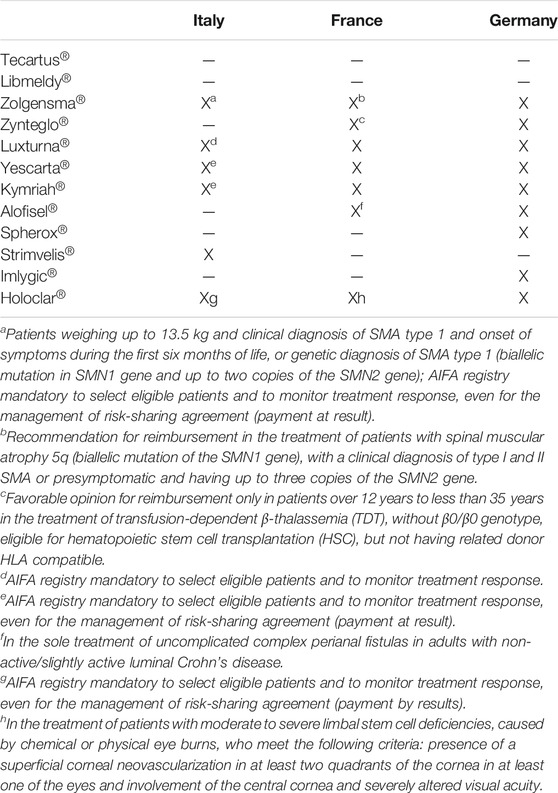

Table 3 reports the reimbursement status of ATMPs. Except for the latest ATMPs approved at the end of 2020, all ATMPs are reimbursed in at least one of the EU countries, and five out of 12 (41%) ATMPs are reimbursed in France, Germany, and Italy.

TABLE 3. Reimbursement status in France, Germany, and Italy of ATMPs approved by the EMA. X = reimbursed; /= not reimbursed or final opinion not available.

A data analysis showed that for eight ATMPs, at least one public HTA evaluation from at least one of the three selected countries is available, and for five of these products, HTA reports have been published by all three countries (Table 4). At the time of the analysis, only the French authorities published opinion about the last ATMPs approved by the EMA in 2020, Tecartus®, and Libmeldy®.

An alignment of the three countries was identified in two out of five cases (16% of the total of 12 ATMPs). In particular, we found an agreement on the value of Luxturna® (“ASMR II” for France; “Significant additional advantage” for Germany; and “Important” for Italy) and Alofisel® (“ASMR IV” for France; “Added benefit not quantifiable” for Germany; and “Poor” for Italy). The assessments were, however, in disagreement for the following medicines: Zolgensma® (“ASMR III/IV” for France; “Evaluation not available” for Germany; and “Important” for Italy), CAR-T Yescarta® (“ASMR III” for France; “Nonquantifiable” for Germany; and “Important” for Italy), and Kymriah® (“ASMR III/IV” for France; “Nonquantifiable” for Germany; and “Important” for Italy).

Patient access to new drugs requires MA from a regulatory authority and reimbursement by a payer. Despite the successful unification of the European procedures for drug approval, each country retains its own jurisdiction over the national market access, pricing, and reimbursement agreements adapted according to national health needs and health-care resources.

At a national level, policy-makers face several challenges when trying to design the most appropriate pharmaceutical policy measures, including the need for ensuring equitable and timely access.

The decision about reimbursement and national access usually needs an HTA appraisal, based on clinical, economic, ethical, and organizational elements. Universally recognized clinical criteria for HTA recommendations include unmet medical needs, relative effectiveness, and safety of the new product compared to the standard of care (if any) (van Nooten et al., 2012).

However, while relying on the evaluation of the same studies, a heterogeneity of the HTA of clinical data has been observed and may be reflected in disparity in terms of national reimbursement decisions and pricing agreements (e.g., coverage or not, treatment restrictions as regard to patients’ eligibility, and risk sharing agreement application).

In this context, a proposal for a regulation by the European Parliament and the Council on health technology assessment amending the Directive 2011/24/EU has been drafted in 2018 and modified in 2021, with the aim to ensure a permanent cooperation on HTA at the EU level, sharing joint clinical assessments, joint scientific consultations, horizon scanning, and voluntary cooperation in nonclinical areas (European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety, n.d.).

Advanced therapies represent an important innovation in the treatment of unmet medical needs, which allows to act on the primary cause of a disease with the possibility of complete recovery in many cases. Indeed, ATMPs may provide significant health benefits generally with a single administration, improving patient outcomes potentially over the long term.

However, due to the high level of both clinical and economic uncertainties, and the need for ensuring a rapid access to a possible curative therapy in patients with no adequate treatment options, ATMPs represent a major issue with regard to the assessment of their value in order to make them available at the national level.

This study shows a low rate of agreement on the therapeutic value (in particular the “added value” compared to the standard of care) of ATMPs approved in Europe to date, having been found only in two cases out of 12 products authorized by the EMA (16%) and out of five ATMPs for which opinions are available in the three countries selected for the analysis (40%). This difference was not related to the choice of different comparators by HTA bodies, due to the lack of alternative therapies in most of the indications, or the availability of one single comparator.

The type of EMA authorization seems not to correlate with the national opinion. CMA, granted before complete efficacy and safety data are available, could potentially lead to limitations of the HTA process. However, even ATMPs approved with CMA (e.g., Tecartus®, Zolgensma®, and Zynteglo®) obtained positive assessment (“important” or “moderate”) with regard to the therapeutic added value.

The assessments issued by AIFA were particularly positive, since the added therapeutic value has been classified as “important” in four cases out of 12 (33%), corresponding to four over five ATMPs for which the evaluation has been made public (80%). On the other hand, the French and German authorities granted an “ASMR II” and a “considerable additional advantage,” respectively, only in the case of one ATMP (Luxturna®) out of 12 (8%), corresponding to one over seven (14%) and one over five ATMPs for which the assessment has been made public to date (20%). This is probably due to the particular attention to rare and ultrarare diseases given by the Italian agency, which explicitly accepts the possibility of having a low quality of evidence in these cases (AIFA, 2017). This results in a different impact on the general value given above all to the lack of a direct comparison with available treatment options, and the low number of patients enrolled. For example, a disagreement has been observed for Zolgensma® assessment, with a score “important” for Italy, “ASMR III/V” for France, and no opinion for Germany. The dossier submitted by the company for MA included two complete trials (CL-303 and CL-101), both open-label and single-arm, and conducted on a few dozen patients (22 and 15, respectively). Even considering all the limitations of the indirect comparison, the Italian report highlighted that patients treated with Zolgensma® obtained better clinical outcome than those treated with the antisense oligonucleotide nusinersen, the only drug available to date (AIFA, 2021). On the contrary, the French institutions considered that the lack of a direct comparison in clinical trials did not allow to define the place in therapy of Zolgensma® with respect to nusinersen (Santè, 2020). Moreover, uncertainties have been raised about maintaining the effect of the treatment. Indeed, long-term data, both with regard to safety and effectiveness, are considered essential to determine the true therapeutic value of these products. The study plan of all ATMPs includes long-term data collection in line with regulatory requirements (The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2007; CHMP CfMPfHU, 2018), but this follow-up is usually still ongoing.

Finally, the German G-BA delayed the assessment of the added therapeutic value of Zolgensma® due to the limited clinical data available so far, and for the first time mandated a company to collect real-world evidence through a registry study in order to close the evidence gaps (Bundesausschuss, 2021). In particular, the G-BA expects a direct comparison of Zolgensma® with nusinersen, and any doctors who want to use the ATMP must take part in the study.

It is noteworthy that on March 2021, the EMA approved a new molecule for the treatment of patients with spinal muscular atrophy, risdiplam, which acts as a splicing modifier that increases and maintains the level of functional protein (EMA Evrysdi, 2021). Even with no direct comparison, it demonstrated a better efficacy and safety profile than nusinersen, as well as an important advantage of administration (oral vs. intrathecal).

Therefore, the availability of the new drug will probably increase the complexity in assessing the therapeutic value of Zolgensma®, also taking into account the high cost of the advanced therapy which has been defined as the most expensive ever.

In France, medicines can be reimbursed only in case the Service Médical Rendu (SMR, absolute clinical value) assessed by the TC of the HAS and is considered sufficient for all ATMPs obtained “important” as the SMR value for the reimbursed indication (Table 3).

However, patient treatment is possible also before the MA (and/or before the decision on the reimbursement of the authorized products), thanks to the Authorization for Temporary Use (ATU; Nominative or Cohort ATU), which allows early access for those with serious or rare diseases without other therapeutic options (ANSM, 2021). Actually, these schemes have been used for targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and ATMPs. For example, Luxturna®, Kymriah®, Yescarta®, and Zolgensma® have been used in France according to the ATU scheme (ANSM, 2019a; ANSM, 2019b; ANSM ATU, 2018; ANSM, 2021).

During the ATU validity, the company can set a free price before the negotiation, but subsequently, the ASMR will be a driver for price negotiation.

In Italy, the AIFA Scientifc Technical Committee (Commissione Tecnico Scientifca, CTS) establishes the reimbursement status of new drugs according to the clinical added value and their place in therapy. In the case of positive opinion, the Price and Reimbursement Committee (Comitato Prezzi e Rimborso, CPR) negotiates with the company the price and any reimbursement agreements.

Moreover, the Law 648/1996 ensures reimbursement and nationwide access to innovative medicinal products authorized in foreign countries but not in Italy, to medicinal products not yet authorized but under clinical trial, and to off-label uses (648 L. Conversione in legge del decreto-legge 21 ottobre 1996 n, 1996; Gozzo et al., 2020a; Gozzo et al., 2020b; Brancati et al., 2021a; Brancati et al., 2021b). For example, the use of Zolgesma® has been granted, thanks to this Italian law before the AIFA reimbursement agreement [(X). Inserimento; (X). Regime di rim].

In Germany, not all ATMPs are assessed as medicines. First of all, the G-BA must categorize the ATMPs as medicines or as medical procedures; subsequently, if considered as medicine, the benefit assessment procedure will be performed. Excluding Spherox® and Holoclar®, all ATMPs have been classified as medicines, and their relative prices have been negotiated taking into account their added therapeutic value (Theidel U von der Schulenburg JM, 2016; Templin et al., 2019; Ronco et al., 2021). Despite the differences in terms of assessment, the access has been usually guaranteed (five over 12 products reimbursed in the three countries at the time of the analysis), even if with various timing and type of restrictions and even with the consequent sustainability issues. This is probably linked to the seriousness of the diseases and/or to the availability of other effective therapeutic treatments. In particular, excluding Tecartus® and Libmeldy®, the two ATMPs most recently approved by the EMA, the three not equally reimbursed are indicated for not life-threatening diseases (cartilage defects or perianal fistulas) or for diseases with other treatment options available (melanoma).

The main limitation of the study is that results are not generalizable to all EU member states. However, countries selected for the analysis are those with a long experience in the HTA and with a clear definition of the therapeutic value through rating scales.

In view of the importance of ATMPs for the treatment of rare and serious unmet needs, it is crucial to understand and act on the causes of disagreement among the HTA, in order to ensure rapid and uniform access to these innovative therapies for all patients eligible for treatment. The adoption of the new regulation on HTA would be useful to harmonize HTA methodologies, hopefully leading to reduced disparities of medicines assessment among European countries.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FD checked and revised the draft manuscript. All authors contributed read, revised, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.755052/full#supplementary-material

648 L. Conversione in legge del decreto-legge 21 ottobre 1996 n (1996). 536, recante misure per il contenimento della spesa farmaceutica e la rideterminazione del tetto di spesa per l’anno. Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1996-12-23&atto.codiceRedazionale=096G0680&elenco30giorni=false (Accessed August, 2021).

AIFA. Regime di rimborsabilità e prezzo del medicinale per uso umano «Zolgensma». (Determina n. DG/277/2021). (21A01554) (GU n.62 del 13-3-2021). Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/stampa/serie_generale/originario.

AIFA (2021). Report innovatività Zolgensma. Det. n. 277 del 10/03/2021 GU Serie Generale n. 62 del 13/03/2021. Available at: https://www.aifa.gov.it/farmaci-innovativi (Accessed march, 2021).

AIFA (2017). Determina dell’agenzia italiana del farmaco, 31 marzoCriteri per la classificazione dei farmaci innovativi e dei farmaci oncologici innovativi ai sensi dell’articolo 1, comma 402, della legge 11 dicembre 2016, 232. Determina n. 519/2017.

AIFA. Inserimento del medicinale Zolgensma (Onasemnogene abeparvovec) nell’elenco dei medicinali erogabili a totale carico del Servizio sanitario nazionale ai sensi della legge 23 dicembre 1996, n. 648, per il trattamento entro i primi sei mesi di vita di pazienti con diagnosi genetica (mutazione biallelica nel gene SMN1 e fino a 2 copie del gene SMN2) o diagnosi clinica di atrofia muscolare spinale di tipo 1 (SMA 1). (Determina n. 126266/2020). (20A06264) (GU n.286 del 17-11-2020). Available at: https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/961234/Determina_AIFA-126266-2020_Zolgensma_Onasemnogene-abeparvovec.pdf (Accessed August, 2021).

Akehurst, R. L., Abadie, E., Renaudin, N., and Sarkozy, F. (2017). Variation in Health Technology Assessment and Reimbursement Processes in Europe. Value Health 20 (1), 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.08.725

Allen, N., Liberti, L., Walker, S. R., and Salek, S. (2017). A Comparison of Reimbursement Recommendations by European HTA Agencies: Is There Opportunity for Further Alignment? Front. Pharmacol. 8, 384. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00384

Angelis, A., Lange, A., and Kanavos, P. (2018). Using Health Technology Assessment to Assess the Value of New Medicines: Results of a Systematic Review and Expert Consultation across Eight European Countries. Eur. J. Health Econ. 19 (1), 123–152. doi:10.1007/s10198-017-0871-0

ANSM (2021). ATU de Cohorte. Protocole d’utilisation therapeutique et de recueil d’informations. Zolgensma. Available at: https://ansm.sante.fr/tableau-atu-rtu/zolgensma-2-x-1013-genomes-de-vecteur-ml-solution-pour-perfusion (Accessed August, 2021).

ANSM ATU (2018). Yescarta. Available at: https://ansm.sante.fr/tableau-atu-rtu/yescarta-1-x-106-2-x-106-cellules-kg-dispersion-pour-perfusion (Accessed August, 2021).

ANSM (2019a). ATU. Kymriah. Available at: https://ansm.sante.fr/tableau-atu-rtu/kymriah-1-2-x-10-6-6-x-10-8-cellules-dispersion-pour-perfusion (Accessed August, 2021).

ANSM (2019b). ATU. Luxturna. Available at: https://ansm.sante.fr/tableau-atu-rtu/luxturna-5-x-10-12-genomes-de-vecteur-ml-solution-a-diluer-injectable (Accessed August, 2021).

ANSM (2021). Règlementation concernant les ATU. Available at: https://ansm.sante.fr/page/reglementation-concernant-les-atu (Accessed August, 2021).

Brancati, S., Gozzo, L., Longo, L., Vitale, D. C., and Drago, F. (2021). Rituximab in Multiple Sclerosis: Are We Ready for Regulatory Approval? Front. Immunol. 12, 661882. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.661882

Brancati, S., Gozzo, L., Longo, L., Vitale, D. C., Russo, G., and Drago, F. (2021). Fertility Preservation in Female Pediatric Patients with Cancer: A Clinical and Regulatory Issue. Front. Oncol. 11, 641450. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.641450

Bundesausschuss, G-B. G. (2021).Resolution of the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) on the Amendment of the Pharmaceuticals Directive (AM-RL): Onasemnogene Abeparvovec (Spinal MuscularAtrophy); Requirement of Routine Data Collection and Evaluationshttps. Available at://www.g-ba.de/downloads/39-1464-4702/2021-02-04_AM-RL-XII_Onasemnogen-Abeparvovec_AADCE_EN.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

Bundesausschuss, G-B. G. (2010). The Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products in Accordance with the German Social Code, Book Five (SGB V), Section 35a. Available at: https://www.g-ba.de/english/benefitassessment/(Accessed march, 2021).

CHMP CfMPfHU (2018). Guideline on Safety and Efficacy Follow-Up and Risk Management of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-safety-efficacy-follow-risk-management-advanced-therapy-medicinal-products-revision_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

Ciani, O., and Jommi, C. (2014). The Role of Health Technology Assessment Bodies in Shaping Drug Development. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 8, 2273–2281. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S49935

Drummond, M. F., Neumann, P. J., Sullivan, S. D., Fricke, F. U., Tunis, S., Dabbous, O., et al. (2019). Analytic Considerations in Applying a General Economic Evaluation Reference Case to Gene Therapy. Value Health 22 (6), 661–668. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2019.03.012

EMA (2017). Assessment Report Alofisel. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/alofisel-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2014). Assessment Report Holoclar. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/holoclar-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2015). Assessment Report Imlygic. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/imlygic-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2018a). Assessment Report Kymriah. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/kymriah-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2018b). Assessment Report Luxturna. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/luxturna-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2016). Assessment Report Strimvelis. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/strimvelis-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2018c). Assessment Report YESCARTA. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/yescarta-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2020). Assessment Report Zolgensma. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/zolgensma-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA (2019). Assessment Report Zynteglo. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/zynteglo-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA CHMPAssessment Report Libmeldy. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/libmeldy-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf. 2020.

EMA. CHMP (2017). Assessment Report Spherox. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/spherox-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA CHMP (2020). Assessment Report Tecartus. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/tecartus-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

EMA. CHMP (2021). Assessment Report Evrysdi. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/evrysdi (Accessed june, 2021).

European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety, . Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Health Technology Assessment and Amending Directive 2011/24/EU - Partial Mandate for Negotiations with the European Parliament. 24 March 2021.

European Parliament, Council of the European Union. (2001). Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use. OJ L 311, 28.11.2001, 67–128.

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2004). Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 Laying Down Community Procedures for the Authorisation and Supervision of Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use and Establishing a European Medicines Agency (Text with EEA Relevance). Official Journal L 136, 30/04/2004, 0001–0033.

Garrison, L. P., Jackson, T., Paul, D., and Kenston, M. (2019). Value-Based Pricing for Emerging Gene Therapies: The Economic Case for a Higher Cost-Effectiveness Threshold. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 25 (7), 793–799. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.18378

Gozzo, L., Longo, L., Vitale, D. C., and Drago, F. (2020). Dexamethasone Treatment for Covid-19, a Curious Precedent Highlighting a Regulatory Gap. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 621934. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.621934

Gozzo, L., Longo, L., Vitale, D. C., and Drago, F. (2020). The Regulatory Challenges for Drug Repurposing during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Italian Experience. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 588132. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.588132

Hettle, R., Corbett, M., Hinde, S., Hodgson, R., Jones-Diette, J., Woolacott, N., et al. (2017). The Assessment and Appraisal of Regenerative Medicines and Cell Therapy Products: an Exploration of Methods for Review, Economic Evaluation and Appraisal. Health Technol. Assess. 21 (7), 1–204. doi:10.3310/hta21070

Jommi, C., Armeni, P., Costa, F., Bertolani, A., and Otto, M. (2020). Implementation of Value-Based Pricing for Medicines. Clin. Ther. 42 (1), 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.11.006

Jönsson, B., Hampson, G., Michaels, J., Towse, A., von der Schulenburg, J. G., and Wong, O. (2019). Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products and Health Technology Assessment Principles and Practices for Value-Based and Sustainable Healthcare. Eur. J. Health Econ. 20 (3), 427–438. doi:10.1007/s10198-018-1007-x

Quinn, C., Young, C., Thomas, J., Trusheim, M., and Group, M. N. F. W. (2019). Estimating the Clinical Pipeline of Cell and Gene Therapies and Their Potential Economic Impact on the US Healthcare System. Value Health 22 (6), 621–626. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2019.03.014

Richardson, J., and Schlander, M. (2019). Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Economic Evaluation: Efficiency or Fairness First. J. Mark Access Health Pol. 7 (1), 1557981. doi:10.1080/20016689.2018.1557981

Ronco, V., Dilecce, M., Lanati, E., Canonico, P. L., and Jommi, C. (2021). Price and Reimbursement of Advanced Therapeutic Medicinal Products in Europe: Are Assessment and Appraisal Diverging from Expert Recommendations? J. Pharm. Pol. Pract 14 (1), 30. doi:10.1186/s40545-021-00311-0

Santè, H-H. Ad. (2013). Le service médical rendu (SMR) et l’amélioration du service médical rendu (ASMR). Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/r_1506267/fr/le-service-medical-rendu-smr-et-l-amelioration-du-service-medical-rendu-asmr (Accessed march, 2021).

Santè, H-H. Ad. (2014). Pricing & Reimbursement of Drugs and HTA Policies in France. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2014-03/pricing_reimbursement_of_drugs_and_hta_policies_in_france.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

Santè, H-H. Ad. (2020). Zolgensma_16122020_AVIS_CT18743. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/evamed/CT-18743_ZOLGENSMA_PIC_INS_AvisDef_CT18743.pdf (Accessed march, 2021).

Seoane-Vazquez, E., Shukla, V., and Rodriguez-Monguio, R. (2019). Innovation and Competition in Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products. EMBO Mol. Med. 11 (3), e9992. doi:10.15252/emmm.201809992

Templin, C. T. K., Rinker, F., and Kulp, W. (2019). Added Benefit Assessment of ATMPs in Germany: Does the Data Basis Meet HTA Requirements? Available at: http://xcenda.de/tl_files/pdf/Poster2019/ADDED%20BENEFIT%20ASSESSMENT%20OF%20ATMPS%20IN%20GERMANY%20-%20DOES%20THE%20DATA%20BASIS%20MEET%20HTA%20REQUIREMENTS.pdf (Accessed August, 2021).

The Council of the European Communities (1993). Council Regulation (EEC) No 2309/93 of 22 July 1993 Laying Down Community Procedures for the Authorization and Supervision of Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use and Establishing a European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. OJ No L 214 of 24. 8. 1993, p. 1.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2007). Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2007 on Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products and Amending Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 (Text with EEA Relevance). OJ L 324, 10.12.2007, 121–137. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2007:324:0121:0137:en:PDF (Accessed march, 2021).

Theidel U von der Schulenburg JM (2016). Benefit Assessment in Germany: Implications for price Discounts. Health Econ. Rev. 6 (1), 33. doi:10.1186/s13561-016-0109-3

van Nooten, F., Holmstrom, S., Green, J., Wiklund, I., Odeyemi, I. A., and Wilcox, T. K. (2012). Health Economics and Outcomes Research within Drug Development: Challenges and Opportunities for Reimbursement and Market Access within Biopharma Research. Drug Discov. Today 17 (11-12), 615–622. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.021

Keywords: advanced medicinal products, health technology assessment, access, added therapeutic value, regulatory issue

Citation: Gozzo L, Romano GL, Romano F, Brancati S, Longo L, Vitale DC and Drago F (2021) Health Technology Assessment of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products: Comparison Among 3 European Countries. Front. Pharmacol. 12:755052. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.755052

Received: 07 August 2021; Accepted: 06 September 2021;

Published: 08 October 2021.

Edited by:

Domenico Criscuolo, Italian Society of Pharmaceutical Medicine, ItalyReviewed by:

Violeta Stoyanova-Beninska, Medicines Evaluation Board, NetherlandsCopyright © 2021 Gozzo, Romano, Romano, Brancati, Longo, Vitale and Drago. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucia Gozzo, bHVjaWFnb3p6bzg2QGljbG91ZC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.