94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 21 January 2022

Sec. Drugs Outcomes Research and Policies

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.750742

This article is part of the Research Topic Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare Disorders View all 20 articles

Background: Nusinersen is an orphan drug intended for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a severe genetic neuromuscular disorder. Considering the very high costs of orphan drugs and the expected market entry of cell and gene therapies, there is increased interest in the use of health technology assessment (HTA) for orphan drugs. This study explores the role of the economic evaluation and budget impact analysis on the reimbursement of nusinersen.

Methods: Appraisal reports for nusinersen were retrieved from reimbursement and HTA agencies in Belgium, Canada, France, England and Wales, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Scotland, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United States. Detailed information was extracted on the economic evaluation, the budget impact, the overall reimbursement decision, and the managed entry agreement (MEA). Costs were adjusted for inflation and currency.

Results: Overall, the reports included limited data on budget impact, excluding information on the sources of data for cost and patient estimates. Only three jurisdictions reported on total budget impact, estimated between 30 and 40 million euros per year. For early-onset SMA, the incremental cost-effectiveness threshold (ICER) ranged from €464,891 to €6,399,097 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained for nusinersen versus standard of care. For later-onset SMA, the ICER varied from €493,756 to €10,611,936 per QALY. Although none of the jurisdictions found nusinersen to be cost-effective, reimbursement was granted in each jurisdiction. Remarkably, only four reports included arguments in favor of reimbursement. However, the majority of the jurisdictions set up an MEA, which may have promoted a positive reimbursement decision.

Conclusion: There is a need for more transparency on the appraisal process and conditions included in the MEA. Additionally, by considering all relevant criteria explicitly during the appraisal process, decision-makers are in a better position to justify their allocation of funds among the rising number of orphan drugs that are coming to the market in the near future.

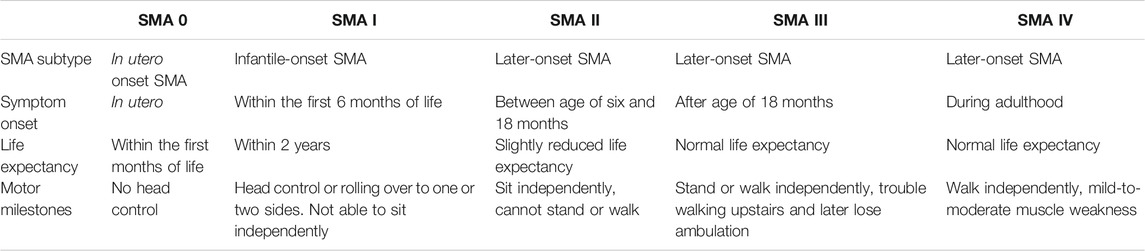

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) linked to chromosome 5q is a rare and life-threatening neuromuscular disorder with an estimated incidence of 1 per 12,000 births (estimated prevalence of 1–2 per 100,000 persons), making it the most frequent genetic cause of child mortality (Pearn, 1980; Verhaart et al., 2017). The disorder is characterized by a loss in alpha motor neurons in the spinal cord and brain stem, which causes progressive weakness of the proximal and respiratory muscles and motor neuron death (Castro and Iannaccone, 2014). This is a result of a deficiency of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is responsible for maintenance of these neurons. Both the SMN1 and SMN2 genes are responsible for encoding the SMN protein. In >90% of the cases, SMA is caused by a deficiency in survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, as a result of either a mutation or deletion (Lefebvre et al., 1995). The severity of the disease is thus inversely correlated by the amount of the remaining SMN2 gene copies and decreases over a spectrum from SMA type 0 to IV, with the index number relating to the maximum motor milestones achieved (see Table 1). SMA types I and II are most common, representing 87% of SMA patients (Unger, 2016).

TABLE 1. The different subcategories of SMA and their characteristics (Pearn, 1980; Munsat and Davies, 1992; Zerres and Rudnik-Schöneborn, 1995; Wijngaarde et al., 2020).

Due to the chronic and progressive character of SMA, patients are dependent on long-term multidisciplinary and supportive care such as orthopedic care for scoliosis and other joint deformities, gastrointestinal and nutritional care, and respiratory management, including assisted ventilation in a palliative stage (Wang et al., 2007; Crawford, 2017). Hence, SMA has a severe impact on the patient’s quality of life (QoL) and life expectancy (Landfeldt et al., 2019). Apart from the clinical burden, SMA also places a significant economic burden, in particular on parents taking care of their child with SMA (Klug et al., 2016; López-Bastida et al., 2017; Belter et al., 2020).

Nusinersen, marketed as Spinraza® by Biogen (Cambridge, MA, United States), was the first disease-modifying orphan drug indicated for the treatment of all patients with 5q SMA. It is an antisense oligonucleotide drug that promotes the expression of the SMN protein, which may lead to significant improvement in patient mobility. It is repeatedly administered intrathecally via a lumbar puncture, with patients receiving six doses within the first year and three doses within each subsequent year for the rest of their lives (Haché et al., 2016). Nusinersen was a first-in-class treatment, which addressed a large unmet need for a rare disease and was thus granted an orphan drug designation by the European Commission and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It gained marketing approval from the FDA and Health Canada in 2016 and 2017, respectively, and from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) under its accelerated assessment program in 2017 (CHMP, 2017). Despite catering to the unmet needs of SMA patients, nusinersen has been criticized for its high price due to various reasons, one of which is the fact that the molecule was discovered at the University of Massachusetts, by researchers financed by CureSMA, which is a nonprofit organization that promotes research on SMA (NYTimes, 2016; Express News, 2017; Prasad, 2018; Metta, 2019; Vandekerckhove and Van Garderen, 2019; Butcher, 2019).

In order to preserve the sustainability of their healthcare systems, decision-makers across jurisdictions evaluate the cost-effectiveness and budget impact as part of a health technology (HTA) assessment. The results are then discussed during the (orphan) drug’s appraisal process, after which a decision is made regarding its reimbursement. Additionally, confidential managed entry agreements (MEAs) are set up between the payer and the pharmaceutical company, allowing reimbursement of a drug for a specified period of time, during which the company provides the treatment at a discounted price (financial-based MEAs) and/or during which additional data on real-world effectiveness may be collected in a dedicated disease or treatment registry (outcome-based MEAs). MEAs are used frequently when data on cost and/or effectiveness are scarce or uncertain, as is often the case for orphan drugs. Several studies have investigated the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen in SMA or SMA subtypes (Zuluaga-Sanchez et al., 2019; Jalali et al., 2020; Thokala et al., 2020). More recently, Dangouloff et al. (2021) performed a systematic review on the economic burden of SMA and the cost-effectiveness of its treatments, such as nusinersen (Dangouloff et al., 2021). However, it is not clear to what extent the results of cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses played a role in the final decision-making regarding its reimbursement. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate how the results of the economic evaluation and budget impact analyses, as part of the HTA, have influenced the decision on the reimbursement of nusinersen across selected jurisdictions. Additionally, we identified which jurisdictions have allowed conditional reimbursement of nusinersen by means of a MEA.

We retrieved HTA and/or appraisal reports for nusinersen from reimbursement and HTA agencies in Belgium, Canada, France, England and Wales, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Scotland, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the US. Countries were chosen depending on the availability of public information. In addition, we have aimed to balance our country selection and reported data from countries that have adopted either a Bismarck or Beveridge model, with either a social or private security system and with an even geographical spread. Reports and relevant publications were translated via Google Translate. Information on economic evaluation was incorporated as submitted by Biogen and presented by HTA or reimbursement agencies. Additionally, in jurisdictions of which HTA reports contained no information on reimbursement decisions and MEAs, a literature search on Google Scholar or PubMed was performed to identify publications, either peer-reviewed or grey literature. These searches included combinations of keywords such as “managed entry agreement” + “France” + “nusinersen” or for instance “reimbursement” + “Italy” + “Spinraza”. We included publications between January 1, 2000, and July 20, 2020.

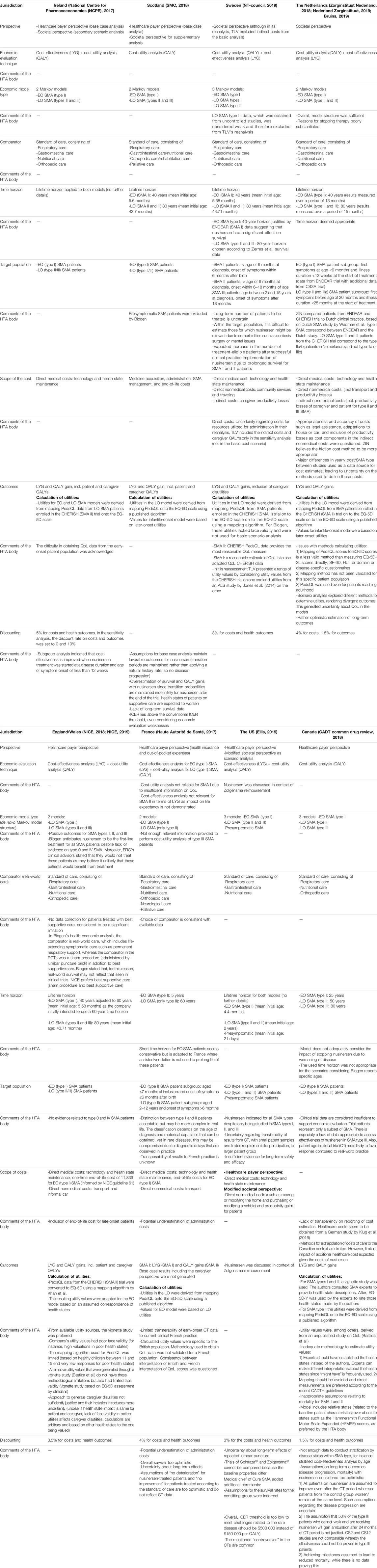

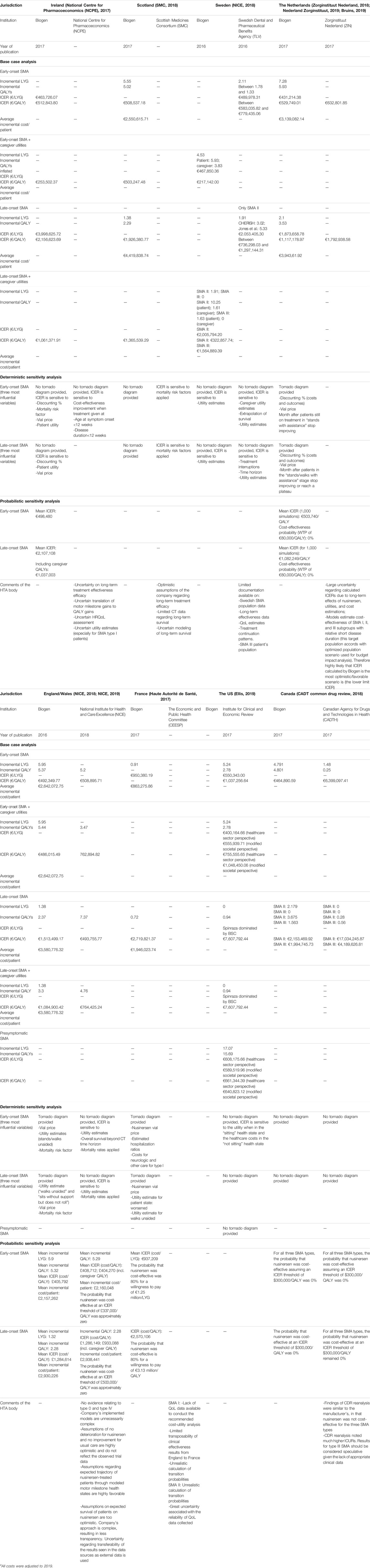

We created two data extraction tables that allowed a systematic data extraction from each HTA or appraisal report. Per jurisdiction, we extracted information on the economic evaluation (study design and results of the base case and sensitivity analysis) (see Table 2 and Table 3) and the budget impact analysis (see Table 4). However, not all jurisdictions are included in each table, as a result of data unavailability. For instance, the jurisdictions England and Wales were not added to Table 4 since budget impact data were not included in the HTA report. Finally, we included information on the overall reimbursement decision, the conditions for reimbursement, and the MEA in the results section.

TABLE 2. Overview of the design of the economic evaluation of nusinersen in six European countries, the US, and Canada.

TABLE 3. Overview of the results of the economic evaluation of nusinersen in six European countries, the US, and Canadaa.

In the base case analysis, all costs were adjusted for inflation and currency changes using the methodology described by Turner et al. (2019). We first inflated costs in the local currency, by using local inflation rates for 2019 for Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, the US (News, 2019), and Sweden (Exchange Rates, 2021). For inflation, we used the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) implicit price deflators which are published annually by the World Bank (The World Bank Group, 2021). Then, local currency values were exchanged. The costs included in the probabilistic sensitivity and budget impact analysis were not adjusted for currency and inflation.

In the following sections, we have summarized, per jurisdiction, several aspects of the economic and budget impact analysis, together with information on the MEA and the reimbursement decision. This is followed by a comparative analysis of the economic evaluation, the budget impact analysis, and reimbursement decision over the different jurisdictions. The full details of the design of the economic analysis, its outcomes, and the budget impact analysis are presented in Tables 2–4, respectively.

The National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE) based its assessment report on nusinersen on the economic evaluation as submitted by Biogen. The economic evaluation included two Markov models, 1) for early-onset (EO) (type I) and 2) late-onset (LO) (types II and III) SMA, comparing nusinersen to the standard of care. Life years gained (LYG), patient’s quality-adjusted life years (QALY), and caregiver QALYs were included for both models and calculated over a lifetime horizon. Direct medical costs (technology and health state maintenance) were included. Biogen obtained utilities for both EO and LO SMA by deriving Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) data from LO SMA patients enrolled in the CHERISH (SMA II) trial. PedsQL is a questionnaire developed to measure the health-related QoL in children and adolescents (Varni et al., 1999). Later, these data were mapped onto the EQ-5D scale. Here, NCPE acknowledged the difficulty of obtaining utilities for EO SMA patients. Discount rates for costs and outcomes were set at 5%. The report presented the results of the base case, sensitivity, and scenario analyses. For the base case analysis, a healthcare payer perspective was adopted, whereas for the scenario analyses, a societal perspective was considered. ICERs were €512,844/QALY and €2,156,624/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. With caregiver utilities included, values dropped to €253,502/QALY and €1,061,37/QALY, respectively. Subgroup analysis indicated that cost-effectiveness could be improved if nusinersen treatment was started when both disease duration and age of symptom onset were less than 12 weeks. Although the report does not present a tornado diagram, the sensitivity analysis indicated a great impact of the discount factor, the nusinersen vial price, and patient utilities for both EO and LO SMA and, for EO SMA additionally, the mortality risk factor. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis resulted in a mean ICER of €498,480 for EO SMA, €2,107,108 for LO SMA, and €1,037,003 for LO SMA with caregiver QALYs included.

Overall, the NCPE concluded nusinersen to be not cost-effective in either EO or LO SMA. They found that a 10- and 20-fold price reduction would be necessary for nusinersen to either approach the €45,000/QALY threshold for EO SMA or fall below the €100,000/QALY threshold for LO SMA, respectively. The total net budget impact for treatment with nusinersen was estimated at €37.88 million, being €19.89 million and €17.99 million for EO and LO SMA, respectively, although the report did not specify whether this includes administration and/or health maintenance costs. Ultimately, the NCPE did not recommend reimbursement of nusinersen at the submitted price, based on its cost-effectiveness and budget impact. Still, nusinersen was granted reimbursement for patients under 18 years old with SMA types I, II, and III after confidential price negotiations were finalized (Ryan, 2019a).

The assessment of the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) was, in part, based on the economic evaluation results for which Biogen submitted two Markov models, for EO and LO SMA, comparing nusinersen to the standard of care. SMC highlighted Biogen’s exclusion of presymptomatic SMA patients from its application. Both models took a lifetime horizon, set at 40 and 80 years for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Biogen obtained LO SMA utilities by mapping PedsQL data, derived from LO SMA patients enrolled in the CHERISH (SMA II) trial, onto the EQ-5D scale. EO SMA utility values were based on those obtained for LO SMA, with minor adaptations as they were regarded as “sufficiently similar” to infants. Discount rates for costs and outcomes were not specified. The report presented results of the base case analysis only, adopting a healthcare payer perspective. ICERs were €508,537/QALY and €1,926,381/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Additionally, Biogen performed a number of scenario analyses, adopting a societal perspective which included caregiver utilities and costs. Compared to the base case, these ICER values dropped to €503,247/QALY and €1,365,539/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Scenario analysis highlighted the ICER’s sensitivity to the mortality risk factor that was adopted in both EO and LO SMA models, although the report did not present a tornado diagram or any other results. Overall, the SMC highlighted several key limitations of the economic evaluation, such as the lack of long-term survival data, optimistic assumptions of overall survival for patients receiving nusinersen and their utility values, especially given the fact that the model assumed that transition probabilities are maintained indefinitely for patients treated with nusinersen while those receiving the standard of care worsen over time.

In its advice, the SMC also considered the views of the Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE) meeting, during which patients shared their experiences on the disease burden for both patients and caregivers and where they highlighted the impact of SMA on patient’s ability to live independently and develop a career.

Biogen proposed an MEA which was deemed acceptable for implementation in Scotland. The SMC added that it wished to report on the cost-effectiveness estimates as obtained under the MEA, yet was unable to do so due to confidentiality reasons. As the budget impact analysis was performed in the context of the MEA, no data were presented on budget impact other than the estimated real-life target population.

For all elements considered, the SMC argued that the ICER values for both EO and LO SMA exceeded conventional ICER thresholds while there was still economic uncertainty. However, nusinersen met certain requirements that acted as decision-modifying criteria, namely, the absence of alternative treatment and the substantial improvement of life expectancy in EO SMA. These disease-modifying criteria allowed the SMC to accept greater economic uncertainty associated with reimbursing nusinersen; thus, access to the treatment was granted for patients with EO SMA. Later, access was extended to patients with LO SMA (SMA News Today, 2019; TreatSMA, 2021).

The Swedish Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency’s (Tandvårds-och läkemedelsförmånsverket, TLV) advice on the reimbursement of nusinersen was partly based on the results of the economic evaluation, comparing nusinersen (and standard treatment) to the standard of care. Biogen submitted results for three Markov models, for EO type I, LO type II, and LO type III SMA. For EO (type I) and LO (type II and III) SMA, both LYG and patient and caregiver QALYs were calculated over a lifetime horizon, set at 40 and 80 years, respectively. Utilities were calculated by mapping PedsQL outcomes onto the EQ-5D scale by using a published algorithm. Both costs and outcomes were discounted at 3%. The base case analysis adopted a societal perspective, including direct medical and nonmedical costs. Additionally, caregiver productivity loss was included as an indirect cost. This resulted in ICERs of €17,142/QALY; €322,858/QALY; and €1,564,889/QALY for EO type I, LO type II, and LO type III, respectively. These ICERs were most sensitive to utility estimates, although a tornado diagram was not provided. TLV excluded caregiver utilities from its base case reanalysis, reporting ICER ranges from €583,035/QALY to €8,251,567/QALY for EO and €736,298/QALY to €1,297,144/QALY for LO type II SMA (depending on utility values used). TLV did not include LO type III SMA outcomes as these data were obtained from noncontrolled studies. ICERs calculated by TLV were higher as its model was based on different assumptions. It tested, for instance, more realistic assumptions regarding disease progression for nusinersen patients, such as a lower probability of death for patients on nusinersen compared to the standard of treatment. Overall, TLV noted uncertainties regarding long-term effectiveness, extrapolation of data, utility estimates and continuation of treatment.

Information on budget impact was limited to the cost/patient/year, amounting to €467,973 in year one and to €233,987 in subsequent years. The number of patients per SMA subgroup was reported although the number of patients eligible for nusinersen treatment was kept confidential. Here, TLV pointed out uncertainties regarding the number of patients eligible for treatment in the long term and the treatment duration. They noted that these numbers are expected to increase in the future after nusinersen prolongs the life of patients with severe SMA.

TLV considered the cost/QALY to be too high in order to provide access according to the European label. They therefore recommended providing access only to patients for whom studies have shown treatment benefit. Hence, access was granted to type I and II SMA patients under 18 years old, and to patients with a subtype of type III (type IIIa) SMA, who are younger than 3 years of age and have a disease pattern comparable to SMA type II (NT-council, 2019; Janusinfo, 2021).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published its report on the single technology appraisal of nusinersen in 2018. In Wales, the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWMSG) excluded nusinersen from assessment and adopted the reimbursement decision made by NICE (AWMSG, 2021). An economic evaluation was included in Biogen’s submission, presenting two Markov models, for EO (type I) and LO (types II and III) SMA, respectively. Incremental LYGs as well as both incremental patient and caregiver QALYs were calculated over a lifetime horizon. The models included direct medical (including a one-time end-of-life cost for SMA I) and nonmedical costs. Utilities in LO SMA were calculated by mapping PedsQL outcomes onto the EQ-5D scale by using a published algorithm. EO SMA utilities were derived from those for LO SMA and based on an assumed correspondence of health states between EO and LO SMA. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3.5%. The base case analysis adopted a healthcare payer perspective, resulting in ICERs of €492,350/QALY and €1,513,499/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. With caregiver utilities included, these values dropped to €486,015/QALY and €1,084,900/QALY, respectively. The tornado diagram showed that, for EO SMA, the factors that influenced the ICER most were the vial price, the utility estimates for the best and worst health states, and the mortality adjustment factor applied to better health states. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis resulted in a mean ICER of £405,792/QALY for EO SMA and £1,284,614 for LO SMA.

NICE noted the fact that there was no evidence submitted that was related to type 0 (in utero onset) and IV (adult onset) SMA. Biogen reportedly stated that SMA type 0 and IV patients were omitted from submission as the clinical evidence available at that time would not meet appraisal requirements. Still, they anticipated nusinersen to be reimbursed and available for first-line treatment of all SMA patients. However, NICE’s clinical advisors stated that they would not treat type 0 SMA patients, except in the context of clinical trials, nor that they would treat type IV SMA patients with nusinersen, as they found it unlikely for these patients to benefit from treatment. Furthermore, the PedsQL mapping algorithm was considered to be limited, for instance, because it was based on healthy school children between age 11 and 15 and because of the few responses of patients in poor health states. Alternative utility values, deducted from a vignette study, were available. Although these also had limited face validity, they did not have the same methodological limitations and thus were considered most appropriate. NICE also noted several shortcomings with the calculations of caregiver disutilities. They criticized Biogen’s assumptions on probabilities of transitioning from one health state to another and on overall survival. For instance, in Biogen’s model, nusinersen patients could not deteriorate, while patients treated with usual care could not improve. These assumptions are inconsistent with trial data that showed a portion of nusinersen patients transitioning to a worse health state, while a proportion of patients receiving usual care improved.

Reanalysis by NICE found ICERs that were higher for EO SMA, yet much lower (one-third) for LO SMA compared to those presented by Biogen. In both EO and LO SMA the inclusion of caregiver QALYs led to an increase of the ICER as calculated by NICE. Overall, ICERs were €508,896/QALY and €493,756/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively, and €762,895/QALY and €764,425/QALY with caregiver QALYs included. The presented ICERs were sensitive to utility estimates and mortality rates in both models and to the overall survival beyond the clinical trial’s time horizon for EO SMA, although the report did not present a tornado diagram. For EO SMA, the probabilistic sensitivity analysis resulted in a mean ICER of £408,712/QALY and £1,286,149 for EO and LO SMA, respectively. With caregiver QALYs included, these values dropped to £404,270/QALY and £933,088, respectively. The results showed a 0% chance for nusinersen to be cost-effective at a threshold of £337,000/QALY for EO and £500,000/QALY for LO SMA. The report did not include information on budget impact.

In order to address long-term uncertainties, Biogen proposed an MEA for a 5-year term and included eligibility and stopping criteria in its draft proposal. Data collection is proposed after 14 months initially and 12 months afterward. The outcomes calculated are survival, ventilation/respiratory events, motor function, and the QoL (for both patients and caregivers). They are collected through the SMART NET registry, including patients who discontinue nusinersen. However, NICE remarked on Biogen’s intention to not include comparative data on patients receiving standard of care, which was considered a significant limitation. They also mentioned the lack of outcome collection for patients with type 0 or IV SMA. NICE concluded that nusinersen was not cost-effective. An MEA was set up, consisting of a price discount combined with coverage with evidence development (CED) agreement (NICE, 2019). After the agreement was reached, NICE recommended nusinersen for reimbursement in presymptomatic and type I, II, and III SMA, for the duration of and within the conditions set out in the MEA (Coyle, 2021).

In France, the value assessment of nusinersen was performed by the Economic and Public Health Evaluation Commission (Commission Evaluation Economique et de Santé Publique, CEESP), which issued an advice to the French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de santé, HAS) and finalized its report on December 12, 2017. The advice included the assessment of the economic evaluation and its results as submitted by Biogen. Two Markov models were presented, for EO (type I) and LO SMA (type II), of which the former calculated LYGs and the latter patient QALYs calculated over a time horizon of 5 and 60 years, respectively. Both direct medical and nonmedical costs were included. Utilities in LO SMA were calculated by mapping PedsQL outcomes onto the EQ-5D scale by using a published algorithm. EO SMA utilities were based on those from LO SMA. Both costs and outcomes were discounted at 4%. The base case analysis adopted a healthcare payer perspective, presenting ICER values of €950,380/QALY and €2,719,821/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. The tornado diagram showed that the nusinersen vial price was the most influential factor for both EO and LO SMA, followed by the estimated hospitalization ratios (nusinersen versus real-world care) and costs for neurologic and other care for EO (type I) SMA and the utility estimate for several health states for LO (type II) SMA. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis resulted in a mean ICER of €937,209/LYG and €2,570,106/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Overall, the models showed an 80% probability for nusinersen to be cost-effective at a threshold of €1.25 million per LYG and €3.13 million per QALY for EO (type I) SMA and LO (type II) SMA, respectively.

CEESP noted limited transferability of EO (type I) SMA trial data to French current practice, as well as of utilities, which were calculated in the British population. Moreover, the method to obtain the utilities was not validated for the French population. The time horizon over which utilities were calculated in EO (type I) SMA was deemed conservative, although it may align to real healthcare practice in France where the life of EO SMA patients is not extended by using assisted ventilation. Overall, CEESP highlighted the lack of data to consider the long-term effects of nusinersen. They found that the estimation of QALYs in EO (type I) SMA was not relevant due to the lack of data on the QoL. Furthermore, they found that the impact of nusinersen on life expectancy in LO (type II) SMA was not demonstrated and therefore considered LYGs irrelevant for this SMA subgroup. Moreover, they stated that the assumptions related to overall survival were too optimistic, in particular the assumption that SMA type II patients on nusinersen will not deteriorate, while those receiving standard of care will not improve. They further noted that the costs for administrating nusinersen were potentially underestimated. In its report, CEESP did not provide a judgment on the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen.

The budget impact analysis adopted a health insurance perspective, and CEESP remarked a potential underestimation of both nusinersen doses administered as well as the total number of patients eligible for treatment. They further noted that 99% of all costs are associated with nusinersen acquisition. Final budget impact data were not presented. When the report was published, nusinersen had a temporary reimbursement status under the conditions of an ATU (temporary authorization of use) plan, which grants exceptional access to medicinal products before a centralized market authorization is granted by EMA (Launet et al., 2004). Ultimately, reimbursement was maintained for patients with EO type I and LO type II and III SMA, although no information is available on the reimbursement conditions that were agreed upon in the MEA.

In the US, a report was issued by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review on April 3, 2019 (updated on May 24), that evaluated nusinersen in the context of the reimbursement of onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma®). At that point, nusinersen was already reimbursed depending on the patient’s insurance provider (Biogen, 2019). The document reports on the results of the economic evaluation as presented by three Markov models, for EO (type I), LO (types II and III), and presymptomatic SMA, each comparing nusinersen to the standard of care. Each model included LYG and QALYs, calculated over a lifetime horizon for each SMA subtype, although no further details were provided. Utility values were derived from multiple sources. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3%. Results of the base case analysis were presented, adopting a healthcare payer perspective, including direct costs. The report presented ICERs of €1,037,257/QALY; €7,607,792/QALY, and €608,176/QALY for EO, LO, and presymptomatic SMA, respectively.

With caregiver utilities included, these values decreased to €755,556/QALY for EO SMA, yet remained the same for LO SMA (€7,607,792/QALY). A number of scenario analyses were performed, one of which adopted a modified societal perspective, including nonmedical costs and productivity gains for patients. The economic evaluation from the healthcare payer perspective and from the modified societal perspective resulted in similar ICERs. The institute did not comment on the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen.

It was noted that, for EO SMA, the ICER was sensitive to the utility when in the “sitting” health state and to the healthcare costs in the “not sitting” health state, although the report did not present a tornado diagram. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review commented on the lack of evidence on long-term safety and efficacy, for instance, on the long-term effects of repeated lumbar puncture for nusinersen administration. Furthermore, the institute questioned whether the small clinical trial patient group and limited requirements to participate in clinical trials allow generalizability of the results to a broader patient group. The report did not show budget impact data on nusinersen treatment compared to the standard of care.

Zorginstituut Netherland (ZIN) issued its final advice on the reimbursement of nusinersen on February 5, 2018. Its advice was based on several appraisal criteria and reported on efficacy, therapeutic need, cost-effectiveness, and budget impact. The data submitted by Biogen included an economic evaluation based on two Markov models, for EO (type I) and LO (type II and III) SMA, comparing nusinersen to the standard of care. Both models included incremental LYGs and patient QALYs, calculated over a lifetime horizon, set at 40 and 80 years for EO and LO SMA, respectively. The target population of the economic evaluation corresponded to the trial population (ENDEAR and CS3A), which represented a subgroup of both EO (type I) and LO (type II and III) SMA. The scope of costs included direct medical, as well as direct and indirect nonmedical costs. Utilities in LO SMA were calculated by mapping PedsQL outcomes onto the EQ-5D scale by using a published algorithm. EO SMA utilities were based on those from LO SMA. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 4 and 1.5%, respectively. Results of the base case analysis were presented, adopting a societal perspective, and reported ICER values of €529,749/QALY and €1,117,179/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Biogen found that these values were most influenced by the discount factor and vial price (for both EO and LO SMA), as well as the month after which a specific motor milestone was reached. Biogen’s probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed a mean ICER of €503,740/QALY and €1,082,249/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. In addition, they estimated a 0% probability that nusinersen is cost-effective at an ICER threshold of €80,000 per QALY in both EO and LO SMA.

Analysis by ZIN concluded that the classification of the EO (type I) SMA subgroup as defined in the model’s target population corresponded to Dutch clinical practice, while the classification of the LO SMA subgroup (types II and III) was found to not correspond to type III patients in Dutch clinical practice. On the other hand, ZIN noted that the data submitted by Biogen represents, per SMA type (I, II, and II), only a subgroup of patients, who had a relatively short disease duration and thus started treatment earlier in comparison to real-world treatment. Therefore, Biogen’s ICER was assumed to reflect the lower limit ICER, hereby representing the most favorable scenario. Reanalysis by ZIN found higher ICER values than those presented by Biogen: €632,802/QALY and €1,792,939/QALY for EO and LO SMA, respectively. Also, ICERs were considered to be highly uncertain due to uncertainties on utilities, long-term outcomes, and (methods for) cost estimations of treatment with nusinersen. With respect to utilities, the applied mapping method was (at that time) not validated in the target population and Biogen was recommended to measure EQ-5D scores either directly or through disease-specific questionnaires. Biogen’s estimation of long-term outcomes was considered to be rather optimistic. ZIN questioned the appropriateness of the methodology used to calculate productivity loss. In addition, it found major differences in cost/year per SMA type between the studies that Biogen used as a source of cost data, which further raised uncertainties on the methods used to define these costs.

Budget impact data were presented for three scenarios, 1) the optimized population scenario (treatment for patients with highest clinical effects), 2) the therapeutic added value scenario (patients for which nusinersen demonstrated added value), and 3) the maximum scenario (treatment for all SMA patients). For each scenario, the budget impact was estimated for the cost of nusinersen alone (thus excluding standard of care) and for costs of nusinersen treatment including drug administration costs (consisting of a lumbar puncture). For the added value scenario, which was preferred by ZIN, the budget impact was estimated at €29.74 million for nusinersen alone and €30.08 million with administration costs included. ZIN remarked the high additional costs of adding nusinersen to the health insurance package, commenting on the uncertainty concerning the total number of eligible patients and the fact that they will need lifelong treatment with nusinersen. Therefore, a pay-for-performance (P4P) agreement was recommended, which provides reimbursement only when treatment is found effective (and thus according to the added value scenario).

Overall, ZIN found nusinersen to be not cost-effective and therefore did not recommend reimbursement unless price negotiations (a price decrease of at least 85%) led to an improvement of the cost-effectiveness. Nevertheless, both the high unmet need and the solidarity principle were arguments that played in favor of reimbursement. However, ZIN pointed out that reimbursement will ultimately threaten the solidarity principle, voicing concern that the combination of a high budget impact with uncertain cost-effectiveness risks displacing other care. Together with Belgium, a joint MEA was set up, linking reimbursement to nusinersen’s performance while reducing the cost through a price discount. Hence, nusinersen was made available for EO SMA type I, LO SMA types II and III, and presymptomatic patients, yet only when an added value in these patients is demonstrated. Meanwhile, the agreement required Biogen to collect additional data on the long-term effectiveness and safety in real-life practice. For patients with SMA who are older than 9.5 years, reimbursement was granted conditionally for 7 years, yet the price was kept confidential (Bruins, 2019).

In January 2018, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) issued its evaluation report on nusinersen. Biogen’s submission was based on three Markov models: one for EO type I, one for LO type II, and one for LO type III SMA, each comparing nusinersen to the standard of care. Each model included LYG and patient QALYs that were calculated over a lifetime horizon, set at 25, 50, and 80 years for EO type I, LO type II, and LO type III SMA, respectively. However, for each subtype, only the cost/QALY was presented. Biogen obtained utilities for LO type II SMA patients by mapping PedsQL data, derived from LO SMA patients enrolled in the CHERISH (SMA II) trial, onto the EQ-5D scale. For EO type I and LO type III SMA, Biogen estimated utilities using a vignette study, where authors asked five SMA experts to describe health states, which they then rated according to the EQ-5D questionnaires. Discount factors for costs and outcomes were set at 1.5%. The report presented the results of the base case analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis, adopting a healthcare payer perspective.

CADTH noted several shortcomings related to the methods applied to calculate utilities and concluded that they were deemed inappropriate, as direct measurements were preferred according to CADTH guidelines. Furthermore, CADTH found Biogen’s assumptions on long-term outcomes too optimistic for patients on nusinersen and noted that overall, the clinical trial data were insufficient to support the economic evaluation, since patients enrolled in the trial presented only a subset of SMA, for whom a more favorable response was more likely when compared to real-life treatment. They also highlighted a lack of data to estimate the cost-effectiveness in LO type III SMA or to conduct stratification by diseases status.

ICERs were €464,891/QALY; €2,153,470/QALY; and €1,994,746/QALY for EO type I, LO type II, and LO type III SMA, respectively. The report did not include a tornado diagram and did not mention the most influential variables affecting the ICER. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed 0% probability for nusinersen to be cost-effective at a $300,000/QALY threshold. The results of the CADTH reanalysis were in line with Biogen’s findings, more specifically, a 0% chance for the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen to be below the $300,000/QALY threshold. Moreover, CADTH found much higher ICERs (€6,399,097/QALY for EO type I SMA; €17,034,246/QALY; and €4,189,627/QALY for LO type II and III SMA, respectively), yet they provided no justification for this discrepancy. They did note that the results for LO type III SMA should be considered speculative due to the lack of appropriate clinical data.

No information on the budget impact analysis was presented other than the drug cost/patient, which was calculated at $708,000 and $354,000 for the first and for each subsequent year, respectively.

Overall, although CADTH concluded that nusinersen was not cost-effective, reimbursement was granted under certain conditions and dependent on the province.

The reimbursement reports of the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV/INAMI) did not include any data on the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen, as reimbursement decisions for orphan drugs in Belgium do not require an economic evaluation. Budget impact data were included, presenting company estimates based on the study population, generating a total cost of nusinersen of €40 million in year 1, and lowering to €25 million and €28 million for the second and third year, respectively. RIZIV/INAMI commented that it expects these estimates to be larger in real-life practice. They noted, for instance, that the percentage of patients who will stop treatment after 14 months remains uncertain. Still, nusinersen was granted reimbursement for patients with type I, II, and III SMA, including presymptomatic patients. A combined financial/outcome-based MEA was set up, involving a price reduction and allowing access to patients for whom an added value was demonstrated. However, the total cost was managed through an absolute cap, which allowed managing uncertainties concerning the total number of eligible patients. Also, it was defined that RIZIV/INAMI would not reimburse costs for nonresponders or all extra costs made during the first year to initiate patients. Additionally, Biogen agreed to collect additional long-term effectiveness and safety data.

The Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) did not assess the cost-effectiveness or budget impact of nusinersen. Rather, reimbursement decisions of medicines in general are based on an assessment of therapeutic need, added therapeutic value and disease rarity. AIFA noted reservations regarding data quality. Based on the overall assessment, nusinersen was granted the status of “therapeutic innovation” and received reimbursement for patients with EO type I and LO type II and III SMA patients, hereby excluding patients with more than four copies of the SMN2 gene (AIFA, 2017a; AIFA, 2017b).

In Germany, reimbursement status depends on a drug’s added benefit, which is de facto considered proven for those with an orphan designation. Additionally, this status is retained as long as the total turnover amounts to a maximum of €50 million within 12 calendar months. Hence, nusinersen was already reimbursed at the time of assessment. However, as the orphan drug’s turnover exceeded €50 million, the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen, IQWiG) did perform an assessment on the extent of the added benefit and issued its final advice to the Federal Joint Committee (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, G-BA) (IQWiG, 2017; G-BA, 2021). IQWiG estimated the cost/patient at €621,354 for the first year and between €310,878 and €310,943 for each subsequent year. They concluded a significant and substantial benefit for EO type I and LO type II SMA, respectively. The added benefit for SMA patients with LO type III and IV was considered nonquantifiable due to the lack of QoL data in these SMA subtypes. Therefore, the final decision was based on other factors such as mortality, morbidity, and risk of adverse events. On these grounds, nusinersen remained reimbursed for the treatment of all SMA patients.

The reimbursement reports for nusinersen in all jurisdictions, with the exception of Belgium, Italy, and Germany, included the results of the economic evaluation. Depending on the jurisdiction of submission, Biogen provided either two or three de novo Markov models, presenting results either for EO type I separately from those for LO type II and III SMA or separately for all three SMA subtypes. HTA bodies in both France and Sweden considered the data on QoL in LO SMA type III to be weak. Additionally, both Scotland and England and Wales reported the lack of data on type 0 and IV SMA. In the US, a third Markov model included presymptomatic SMA, although the report was not based on a file submitted by Biogen.

In each jurisdiction, Biogen calculated costs and outcomes over a lifetime horizon and this choice was considered to be appropriate by the respective HTA bodies. The target population presented by Biogen corresponded to the clinical trial population, where patients were excluded based on their age and other criteria such as co-occurring scoliosis or issues with mental health. Hence, the target population represented only a subgroup of SMA patients, for whom a favorable response with nusinersen treatment is more likely when compared to real-world practice. Furthermore, France, England and Wales, and Sweden questioned the extrapolation of data due to a lack of local data on costs and patient numbers.

Economic evaluations submitted to HTA agencies in France, England and Wales, Canada, Ireland, Scotland, and the US presented base case results from a healthcare payer perspective, whereas those from Sweden and the Netherlands adopted a broader, societal perspective. Additionally, in Ireland, Scotland, and the US, a scenario or secondary analysis was performed in which a societal perspective was adopted. In Ireland and Scotland, the societal perspective included costs for caregivers. The decrease of the ICER was most significant in Ireland, where shifting from a healthcare to a societal perspective lead to a decrease of approximately 50%. In the US, a (modified) societal perspective included direct nonmedical costs (such as costs for moving or modifying the patient's home and for purchasing or modifying a vehicle) and productivity gains for patients. Here, the ICER was the same for both perspectives. In the societal perspective, total costs increased similarly for patients treated with either nusinersen or standard of care, while QALY gains remained the same in both groups (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. ICER values of nusinersen for EO and LO SMA, depending on the chosen perspective, reported by HTA agencies in Ireland, Scotland, and the US. Abbreviations: ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; EO, early-onset; LO, later-onset; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Nearly all HTA agencies highlighted uncertainties regarding utilities and ICER values. These resulted from a lack of data on QoL, in addition to several shortcomings regarding the methodologies used to obtain utilities, through either PedsQL data mapping or a vignette study. Moreover, in Scotland, Canada, the US, the Netherlands, and England and Wales, Biogen’s assumptions on disease progression and hence long-term outcomes and survival rates with nusinersen were considered to be rather optimistic, especially compared to the assumptions made for the comparator group.

Only reports from England and Wales, France, and the Netherlands presented a tornado diagram, illustrating the ICERs sensitivity to mostly the vial price and utility estimates. The reports from the Netherlands, England, Wales, and Canada each reported a 0% chance for nusinersen to be cost-effective at the local willingness-to-pay threshold, whereas HAS-CEESP (France) estimated that nusinersen would have an 80% chance of being cost-effective at a threshold of €3.13 million per QALY.

Only Belgium the Netherlands and Ireland reported the total budget impact of reimbursing nusinersen. For each of these countries, a time horizon of, respectively, three and 5 years was chosen. Whereas the Netherlands provided budget impact data for both nusinersen alone and for nusinersen combined with administration costs, the cost components were not specified in the reports issued by the HTA bodies in the remaining countries. Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada provided the estimated cost per patient per year. None of the reports mentioned sources of data for cost and patient estimates. Overall, HTA bodies cited uncertainties or a potential underestimation regarding the number of patients eligible for nusinersen treatment (Sweden, Belgium, Germany, France, and the Netherlands). Moreover, since nusinersen aims to increase life expectancy in SMA patients, patient numbers are expected to rise in the future.

Despite economic evaluations indicating that nusinersen was generally not cost-effective and despite limited data on budget impact, all countries under study reimbursed nusinersen. Germany, Belgium, and Italy provided the broadest access, by reimbursing nusinersen for all SMA patients, in line with the European label. On the other hand, access in Scotland was most narrow, reimbursing nusinersen only for EO (type I) SMA patients. In the US, access depends on the patient’s health insurance provider. The remaining countries provided access to type I, II, and III SMA patients, either with or without age restrictions. In England and Wales, additionally, presymptomatic patients were covered.

In Ireland, Scotland, Sweden, England and Wales, Belgium, and the Netherlands, reimbursement was granted under the conditions of an MEA. The MEAs in the Netherlands and Belgium are believed to be both financial and outcome-based, whereas, in England and Wales, a CED agreement was made. Overall, little information on these MEAs was available, due to the confidentiality of these agreements and their content.

The goal of this study was to analyze how the economic evaluation and budget impact of nusinersen in selected European jurisdictions influenced its reimbursement. We believe that our results contribute to a better understanding of the efficiency and shortcomings of the HTA in the context of orphan drugs.

The results show that the amount and level of detail of cost-effectiveness data on nusinersen, which was either submitted by Biogen or presented by the HTA agencies, differed highly between jurisdictions. Yet, the reports described similar methodological barriers that may have complicated a proper evaluation and reassessment of the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen from the submitted models. We believe that these barriers are in alignment with those encountered for orphan drugs in general, which are extensively described in the peer-reviewed literature (Lagakos, 2003; McCabe et al., 2006; Drummond et al., 2007; Hughes-Wilson et al., 2012; Augustine et al., 2013; Schlander et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2018; Nestler-Parr et al., 2018; Nicod et al., 2019; Blonda et al., 2021).

First of all, the HTA and reimbursement agencies reported uncertainties in utility values and questioned the added value of nusinersen in SMA subtypes, in type 0, type IV, and even type III SMA. In the past, methodologies to determine utility values have been criticized for being ill-adapted to the needs of younger patients (Eiser and Morse, 2001; Matza et al., 2004; Prosser, 2009; Ungar, 2011; Lim et al., 2014; Montgomery and Kusel, 2016; Gissen et al., 2021). These shortcomings become more impactful considering the fact that 69.9% of rare diseases present themselves in a mainly young patient population, such as in the case of SMA (Nguengang Wakap et al., 2020).

In addition, cost-effectiveness calculations mainly relied on clinical trial data, which included a healthier subgroup of SMA patients, whereas in real life, rare disease patients such as those suffering from SMA represent a heterogenous patient group, who may suffer from various comorbidities such as scoliosis and mental health issues. This heterogeneity complicates the extrapolation of treatment effects of nusinersen on the clinical trial population, to the broader, real-world patient group (Morel et al., 2013; Nicod, 2017).

Also, due to the severity of SMA, the EMA and FDA halted clinical trials early following strong interim results (EMA, 2021; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2016). Indeed, clinical trials for orphan drugs are often stopped early due to a sense of urgency to market therapies for severe rare diseases (Simoens, 2011). However, this also puts an early stop to the collection of data, resulting in companies having to make assumptions as they extrapolate intermediary data to estimate the effectiveness over a horizon of 10–40 or even 80 years when submitting their reimbursement files. Indeed, we found that Biogen’s assumptions on the long-term effectiveness of nusinersen were rather optimistic compared to those of the reimbursement and HTA bodies. Unfortunately, this has further contributed to the uncertainty surrounding cost-effectiveness and budget impact estimates. In addition, this may lead to reimbursement agencies coming to a different conclusion than the regulatory agencies (EMA and FDA) (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2016; EMA, 2021). In fact, for conditionally approved medicines such as nusinersen, differences in evidentiary requirements are claimed to be the main cause for the disparity between the central marketing authorization process on the one hand and the decentralized reimbursement processes on the other (Wang et al., 2018). In these cases, drug developers should initiate an early dialogue of evidentiary requirements and postlicensing commitments with both regulatory and reimbursement agencies (which, since recently, may be facilitated by EUnetHTA) in order to receive a joint scientific advice (EMA and EUnetHTA, 2021). However, we found no evidence that such efforts were made in the case of nusinersen.

Still, there is a need to streamline both the authorization and reimbursement process, as discrepancies may often lead to a duplication of the clinical assessment conducted by the HTA agency, result in delays in market entry, and contribute to uncertainty regarding patient access (Hawlik et al., 2018). This is especially the case for drugs fulfilling an unmet need such as nusinersen. These drugs may receive conditional marketing authorization from a regulatory authority, only to have their reimbursement delayed when the HTA agency does not grant them the same flexibility. Since 2018, the EU Council, together with the Member States have been developing a Proposal for a Regulation on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Amending Directive 2011/24/EU (the latter being known as the Cross-Border Healthcare Directive). This proposal includes the provision of a joint clinical assessment at the time of marketing authorization which, following a nonduplication principle, would mean that evidence submitted in the context of the joint assessment would not be requested again at the level of the Member States. Additionally, the proposal would support joint scientific consultations, allowing drug developers to seek early advice from HTA agencies (European Commission, 2018). Member States finally came to an agreement in March 2021 and are now expected to start negotiations with the European Parliament on a final legislative proposal (European Council, 2021). If legislation is adopted later in 2021, the first joint scientific HTA reports are to be expected in 2024 (IHS Markit, 2021).

Finally, jurisdictions highlighted the lack of local data on cost and patient numbers. We believe that herein lies an opportunity for a joint effort between authorities and the European Reference Networks (ERN). These virtual networks, formed by healthcare providers across Europe, receive funding for activities relating to research and data collection, in order to advance knowledge on rare diseases. However, many barriers are currently limiting them to reach their full potential in supporting data collection and sharing. For example, variabilities in Member State’s legal frameworks raise issues with data protection and, as such, may inhibit efficient data sharing between the Member States. Furthermore, the ERNs lack national funding for services such as maintenance of IT infrastructure dedicated to the collection of data in ERN registries. Meanwhile, the ERNs own regulations on avoiding conflicts of interest limit them from collaborating with industries or participating in research when this is entirely or partially industry-funded (Héon-Klin, 2017; Tumiene et al., 2021). We urge the Member States, together with the ERNs, to develop sustainable and efficient strategies for both internal and external collaboration. More importantly, they should develop a clear and long-term vision towards the collection and management of real-world data for rare diseases and clearly define each of the stakeholder’s role therein. We believe that this way, the ERNs may realize their full potential in their pan-European efforts to address the unmet needs of rare disease patients.

In general, the reports contained little details on the scope and outcome of the budget impact analysis. In the absence of data and, hence, transparency on the budget impact, questions arise regarding the quality of the analysis. For instance, when reporting on the scope of costs (included in the budget impact analysis), the analysis should consider not only drug costs but also costs for drug administration and adverse events. None of the reports clearly defined which costs were included in the analysis. Also, it is advised that a qualitative budget impact analysis includes some testing of assumptions on the estimated target population. From the available information, we found that these assumptions were only tested in the Netherlands. Finally, none of the reports disclosed data sources for either costs or target population estimated, and it is unclear whether budget impact analyses were validated. This accords with recent findings of Abdallah et al. (2021), who concluded that budget impact analyses on orphan drugs are currently of poor quality and do not fully adhere to guidelines of good practice as set up by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).

The differences in methodology and reporting on the cost-effectiveness and budget impact inhibit a proper comparison of the outcomes between the jurisdictions. Such a comparison is further complicated by the fact that countries have implemented different value assessment frameworks, some of which were adapted specifically to allow more flexibility for orphan drugs, such as in Ireland, Scotland, and England and Wales, while others are catered to treatments indicated for a severe disease, such as in Sweden and the Netherlands (Stolk et al., 2004; SMC, 2012; van de Wetering et al., 2013; van de Wetering et al., 2015; Kanters, 2016; NICE, 2017; Pearson et al., 2018; Nicod and Whittal, 2020). Nevertheless, there appears to be no correlation between nusinersen’s cost-effectiveness and the SMA subtypes for which reimbursement was granted. The countries that highlighted weaknesses or scarcity of effectiveness data in either type 0, type IV, or type III SMA still provided reimbursement for patients with these indications, with the exception of Scotland.

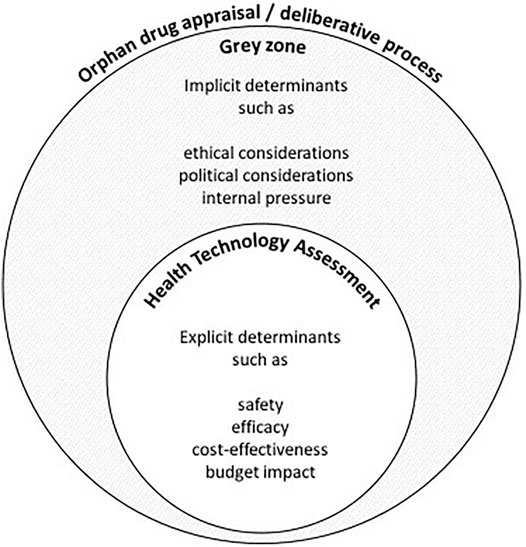

The fact that nusinersen was reimbursed despite reportedly uncertain or unfavorable ICER values and budget impact implies that decision-makers considered other implicit determinants that favored a positive reimbursement decision. This suggests that there exists a grey zone between the assessment and (final) appraisal step of the reimbursement process. Whereas the assessment is detailed in the HTA report, which describes the orphan drug’s performance against mainly clinical (safety and efficacy) and economic (cost-effectiveness and budget impact) criteria, the reports generally do not elaborate on the discussion that took place during the appraisal step. The implicit determinants, hereafter referred to as “grey zone” determinants, which play a role during the appraisal remain vague, and thus, it can be argued that the final decision is poorly substantiated (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. A schematic and nonexhaustive visualization of the deliberative process for the reimbursement of an orphan drug such as nusinersen. Any discrepancy between the assessment and appraisal of an orphan drug may be the result of grey zone determinants that are not adequately described in the final reimbursement report.

For instance, in several countries, political factors and/or pressure from media outlets and disease advocacy organizations may have contributed to a positive reimbursement decision. According to King and Bishop, the “hype” that these stakeholders created around nusinersen may have resulted in an overestimation of the beneficial treatment effects of nusinersen, while the risks were minimized. Moreover, while access to public information grows, it becomes increasingly difficult to admit that certain uncertainties concerning cost and effectiveness data have remained. In addition, a close relationship between the patient organization CureSMA and the nusinersen research team may have skewed information and data (King and Bishop, 2017). The influence of patient organizations was also prominent in Ireland, where SMA Ireland launched a petition after the national health authority, Health Service Executive (HSE), and Biogen failed to come to an agreement on the reimbursed price of nusinersen. Nearly 4 months later, following an intense campaign by both SMA patients and their family members, the HSE granted reimbursement for nusinersen for type I, II, and III SMA patients (Ryan, 2019a; Ryan, 2019b; Ryan, 2021).

As mentioned before, many countries are adapting their standard processes to tailor to the needs of orphan drugs. For instance, in Scotland, reimbursement was initially granted only for type I SMA patients, while type II and III SMA patients were excluded. However, shortly after the initial appraisal, a reimbursement pathway for ultra-orphan drugs was implemented that allowed a broader conditional reimbursement for type II and III SMA patients for a period of 3 years, after which nusinersen will be reassessed based on additional evidence (scheduled for 2022) (SMC, 2021a). However, this “revised” reimbursement decision for type II and III SMA was based on the original HTA report. This implies that during the reassessment different reimbursement criteria were applied or that at least more leniency was granted for nusinersen in types II and III compared to type I SMA. Unfortunately, the arguments in favor of broadening the reimbursement of nusinersen were not publicly specified.

Additionally, we have reason to assume that ethical arguments played a role in the decision-making process. For instance, in its final advice, ZIN underlined the solidarity principle, while both the SMC (Scotland) and ZIN (the Netherlands) mentioned unmet medical need as an important argument in favor of reimbursement. In Scotland, unmet medical need is formally included as a decision modifier, which may allow a higher ICER threshold compared to standard treatments (SMC, 2012). In England and Wales, the report stated that the rarity and severity of SMA were considered, although it did not disclose the extent to which these factors influenced the final decision (NICE, 2019). Meanwhile, TLV concluded its report with a statement that, in general, drug decision-making is based on three principles: 1) human value, 2) need and solidarity, and 3) cost-effectiveness. However, it did not mention to what extent it found that nusinersen met either of these three principles (NT-council, 2019).

Indeed, the fact that decision-makers are increasingly balancing efficiency criteria (such as cost-effectiveness and budget impact) with ethical criteria (such as severity or unmet need), when assessing the value of orphan drugs, is not new (Pinxten et al., 2012; Nicod et al., 2017; Burgart et al., 2018; Nicod et al., 2019; Blonda et al., 2021). However, there is a need for more transparency on the factors that influence decision-making after an HTA guidance is issued, as this is becoming increasingly important in order to substantiate decisions on budget allocation, especially in those cases where there is substantial uncertainty on the cost and/or effectiveness of treatment. Additionally, by disclosing the grey zone determinants, decision-makers facilitate a broader acceptance of the reimbursement decision among the different stakeholders (Youngkong et al., 2012; Iskrov et al., 2017; Schey et al., 2017; Baltussen et al., 2018; Bond et al., 2020; Blonda et al., 2021). In order to increase transparency on the appraisal process, we therefore advise decision-makers to define and formally include these determinants in the reimbursement process and the final reimbursement report. In fact, next to “transparency,” the principle of “inclusivity” and “impartiality” make up the three core principles around which Bond et al. (2020) propose to structure the appraisal or deliberative process of a health technology. The principle of inclusivity aims to ensure that all stakeholders, including patient representatives, are represented during the decision-making process and that their views are genuinely considered. The impartiality principle aims towards a process that is free from both internal and external influences. This could be done, for instance, by describing how a campaign and petition by a patient advocacy organization such as SMA Ireland may have shifted the opinions of the stakeholders involved in decision-making. By structuring the appraisal process according to these three core principles, we believe that decision-makers can minimize the influence of external pressure and/or political considerations on decision-making, especially in the case of innovative yet expensive orphan drugs such as nusinersen.

We assume that the outcomes of the cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses included in the HTA report, together with the grey zone determinants, act as a facilitator and starting point for setting up MEAs. These agreements have become a tool that enables decision-makers to allow reimbursement, albeit conditional, while managing the remaining uncertainties surrounding cost and effectiveness. Still, there are no public data on how confidential rebates have improved the cost-effectiveness of nusinersen or on how data uncertainties are revised after the MEA period (Gerkens et al., 2017). When the real cost-effectiveness and budget impact of nusinersen cannot be assessed, there is no transparency on whether financial resources are fairly allocated across disease areas. Also, there will be no benchmarks to which future orphan drugs may be compared. Still, decision-makers will face similar barriers when deciding on future therapies for rare diseases, such as Risdiplam® and the gene-therapy Zolgensma® for SMA, which are potentially curative but will have a considerably higher price. Providing a high and unjustified price to these innovative drugs may boost the price of future treatments even more, especially those for other rare conditions that are still lacking an adequate reference treatment. In addition, increasing expenditure on orphan drugs risks to disrupt healthcare systems worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and may further contribute to unequal access for SMA patients.

Our study is not without limitations. First of all, reporting on budget impact was incomplete and nontransparent, which made it difficult to draw conclusions on its use in decision-making. Second, we analyzed reimbursement reports from a limited number of jurisdictions, which may have led to selection bias. The inclusion of additional jurisdictions could have led to different conclusions. However, as we selected jurisdictions that were spread throughout the EU, we believe that our findings are generalizable to orphan drugs in general. Third, by using an online translator such as Google Translate, there is a potential risk of misinterpretation of data due to translation errors. Fourth, more thorough information on MEAs could have been retrieved by performing a systematic literature review, including search terms in languages from all respective countries.

This study has analyzed how the economic evaluation and budget impact of nusinersen in selected European jurisdictions influenced its reimbursement. Furthermore, it has contributed to a better understanding of the role of economic criteria on the reimbursement of orphan drugs in general.

The results confirmed that an HTA based on economic criteria alone is not sufficient to define the value of orphan drugs. However, by not being transparent on the “grey zone determinants” in favor of reimbursement, the economic evaluation loses its value as a tool to effectively rank orphan drugs and allocate funds from a limited budget. We suggest that decision-makers provide more transparency on the appraisal process of orphan drugs and on the requirements that are negotiated in the context of an MEA. By formally incorporating all determinants into a reimbursement process that is transparent, inclusive, and impartial, decision-makers contribute to a sustainable environment for orphan drugs and future therapies.

SS developed the idea of the study, outlined the aim and structure of the review and manuscript, and provided guidance. TB collected HTA reports and performed the first analysis of a selected group of countries. AB performed a literature review and analysis of all countries included and wrote the manuscript. SS, TB, and MT have critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This research was funded by the Research Foundation of Flanders (FWO, Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek); the grant number is G0B9819N.

SS has previously conducted research on the market access of orphan drugs sponsored by the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre and by Genzyme (now Sanofi), and he has participated in an orphan drug roundtable sponsored by Celgene. SS is a member of the ISPOR Special Interest Group on Challenges in Research and Health Technology Assessment of Rare Disease Technologies, the International Working Group on Orphan Drugs, and the Innoval Working Group on Ultra-Rare Disorders. MT has previously acted as a consultant for Novartis Gene Therapies. AB and TBL declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdallah, K., Huys, I., Claes, K., and Simoens, S. (2021). Methodological Quality Assessment of Budget Impact Analyses for Orphan Drugs: A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 215. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.630949

AIFA (2017a). “Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA),” in Valutazione Dell’Innovatività - Medicinale SPINRAZA (US: Nusinersen).

AIFA (2017b). “Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA),” in Scheda Spinraza Approvata CTS 28.09 (US: Nusinersen).

Augustine, E. F., Adams, H. R., and Mink, J. W. (2013). Clinical trials in rare disease: challenges and opportunities. J. Child. Neurol. 28 (9), 1142–1150. doi:10.1177/0883073813495959

AWMSG (2021). Nusinersen (Spinraza®). Accessed July 29, https://awmsg.nhs.wales/medicines-appraisals-and-guidance/medicines-appraisals/nusinersen-spinraza/ (Published July 14, 2017).

Baltussen, R., Jansen, M., and Bijlmakers, L. (2018). Stakeholder participation on the path to universal health coverage: the use of evidence-informed deliberative processes. Trop. Med. Int. Health 23 (10), 1071–1074. doi:10.1111/tmi.13138

Belter, L., Cruz, R., Kulas, S., McGinnis, E., Dabbous, O., and Jarecki, J. (2020). Economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy: an analysis of claims data. J. Mark Access Health Pol. 8 (1), 1843277. doi:10.1080/20016689.2020.1843277

Biogen, A. (2019). Guide for Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Their Caregivers Navigating Insurance and Support Programs for Spinraza®. US: Nusinersen.

Blonda, A., Denier, Y., Huys, I., and Simoens, S. (2021). How to Value Orphan Drugs? A Review of European Value Assessment Frameworks. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 695. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.631527

Bond, K., Stiffell, R., and Ollendorf, D. A. (2020). Principles for deliberative processes in health technology assessment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 36, 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0266462320000550

Bruins, B. (2019). Kamerbrief over Voorwaardelijke Toelating Nusinersen. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/kamerstukken/2019/12/11/kamerbrief-over-voorwaardelijke-toelating-nusinersen/kamerbrief-over-voorwaardelijke-toelating-nusinersen.pdf.

Burgart, A. M., Magnus, D., Tabor, H. K., Paquette, E. D., Frader, J., Glover, J. J., et al. (2018). Ethical challenges confronted when providing nusinersen treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Pediatr. 172 (2), 188–192. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4409

Butcher, L. (2019). Two New Treatments for Spinal Muscular Atrophy May Be Clinically Effective, But Are They Cost-Effective? Neurol. Today 19 (8), 48–51. doi:10.1097/01.nt.0000558060.65287.461

Castro, D., and Iannaccone, S. T. (2014). Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Therapeutic Strategies. Curr. Treat. Options. Neurol. 16 (11), 316. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0316-3

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2016). Application Number 209531Orig1s000 Medical Review(S). US: CDER.

CHMP (2017). Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Assessment Report: Spinraza.www.ema.europa.eu/contact (Accessed May 11, 2021).

Coyle, D. “HSE to consider funding Spinraza as NHS approves muscle-wasting therapy,” in The Irish Times. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/health-pharma/hse-to-consider-funding-spinraza-as-nhs-approves-muscle-wasting-therapy-1.3892962 (Published May 15, 2019).

Crawford, T. O. (2017). “Standard of Care for Spinal Muscular Atrophy,” in Disease Mechanisms and Therapy (Baltimore, MD, United States: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine), 43–62.doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803685-3.00003-3 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128036853000033 (Accessed March 25, 2021).

Dangouloff, T., Botty, C., Beaudart, C., Servais, L., and Hiligsmann, M. (2021). Systematic literature review of the economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy and economic evaluations of treatments. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16 (1), 47–16. doi:10.1186/s13023-021-01695-7

Drummond, M. F., Wilson, D. A., Kanavos, P., Ubel, P., and Rovira, J. (2007). Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 23 (3), 36–42. doi:10.1017/S0266462307051550

Eiser, C., and Morse, R. (2001). Can parents rate their child's health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 10 (4), 347–357. doi:10.1023/A:1012253723272

Ellis, A., Mickle, K., and Herron-Smith, S. (2019). Spinraza® and Zolgensma® for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Effectiveness and Value-Final Evidence Report. Available at: https://icer.org/assessment/spinal-muscular-atrophy-2019/.

EMA (2021). EPAR Summary for the Public: Spinraza. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/contact (Accessed March 25, 2021).

European Commission (2018). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Health Technology Assessment and Amending Directive 2011/24/EU COM/2018/051 Final - 2018/018 (COD), 49. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52018PC0051 (Accessed July 6, 2021).

European Council (2021). Health technology Assessment Post 2020 - Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/health-technology-assessment-post-2020/ (Accessed July 29, 2021).

EMA and EUnetHTA (2021). EMA/410962/2017 Rev 4. Guidance on Parallel Consultation. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guidance-parallel-consultation_en.pdf (Accessed July 1, 2021).

Exchange Rates (2021). Euro to Swedish Krona Spot Exchange Rates for 2019. Exchange Rates. https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/EUR-SEK-spot-exchange-rates-history-2019.html (Accessed May 14, 2021).

Express News (2017). Hefty price set on a new drug that can stunt muscle disease. https://www.expressnews.com/business/health-care/article/Hefty-price-set-on-a-new-drug-that-can-stunt-10829208.php (Accessed July 1, 2021).

G-BA (2021). -Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products with New Active Ingredients According to Section 35a SGB V Nusinersen (Exceeding €50 Million Turnover Limit: Spinal Muscular Atrophy. www.g-ba.de (Accessed July 25, 2021).Internal Justification of the Resolution of the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) on an Amendment of the Pharmaceuticals Directive (AM-RL): Annex XII.

Gerkens, S., Neyt, M., San Miguel, L., Vinck, I., and Thiry, N. C. I. (2017). How to Improve the Belgian Process for Managed Entry Agreements? an Analysis of the Belgian and International Experience. www.kce.fgov.be (Accessed February 16, 2021).

Gissen, P., Specchio, N., Olaye, A., Jain, M., Butt, T., Ghosh, W., et al. (2021). Investigating health-related quality of life in rare diseases: a case study in utility value determination for patients with CLN2 disease (neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16 (1), 217. doi:10.1186/s13023-021-01829-x

Haché, M., Swoboda, K. J., Sethna, N., Farrow-Gillespie, A., Khandji, A., Xia, S., et al. (2016). Intrathecal Injections in Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Nusinersen Clinical Trial Experience. J. Child. Neurol. 31 (7), 899–906. doi:10.1177/0883073815627882

Hawlik, K., Rummel, P., and Wild, C. (2018). Analysis of duplication and timing of health technology assessments on medical devices in europe. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 34 (1), 18–26. doi:10.1017/S0266462317001064

Héon-Klin, V. (2017). European Reference networks for rare diseases: what is the conceptual framework? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 12 (1), 137–139. doi:10.1186/S13023-017-0676-3

Hughes-Wilson, W., Palma, A., Schuurman, A., and Simoens, S. (2012). Paying for the Orphan Drug System: break or bend? Is it time for a new evaluation system for payers in Europe to take account of new rare disease treatments? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 7 (1), 74. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-74

IHS Markit (2021). Industry hopes dashed after EU compromises to squeeze through cross border HTA agreement. Published June 29, https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/industry-hopes-dashed-eu-compromises-HTA.html (Accessed July 29, 2021).

IQWiG (2017). “Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG),” in Nusinersen (5q-Assoziierte Spinale Muskelatrophie) – Bewertung Gemäß § 35a Abs. 1 Satz 10 SGB V (US: Nusinersen).

Iskrov, G., Miteva-Katrandzhieva, T., and Stefanov, R. (2017). Health Technology Assessment and Appraisal of Therapies for Rare Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1031, 221–231. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67144-4_13

Jalali, A., Rothwell, E., Botkin, J. R., Anderson, R. A., Butterfield, R. J., and Nelson, R. E. (2020). Cost-Effectiveness of Nusinersen and Universal Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J. Pediatr. 227, 274–e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.07.033