- 1Ganzhou Cancer Hospital, Ganzhou, China

- 2Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, St. John’s University, Queens, NY, United States

- 3Cell Research Center, Shenzhen Bolun Institute of Biotechnology, Shenzhen, China

Since the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan (China) in December 2019, the epidemic has rapidly spread to many countries around the world, posing a huge threat to global public health. In response to the pandemic, a number of clinical studies have been initiated to evaluate the effect of various treatments against COVID-19, combining medical strategies and clinical trial data from around the globe. Herein, we summarize the clinical evaluation about the drugs mentioned in this review for COVID-19 treatment. This review discusses the recent data regarding the efficacy of various treatments in COVID-19 patients, to control and prevent the outbreak.

Introduction

The outbreak of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19), from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019, has now become the first global pandemic caused by the spread of coronavirus. On February 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) gave a name for the novel coronavirus as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 (Bevova et al., 2020). Most recently, several predominate SARS-CoV-2 variants, including, but not limited to, B.1.1.7 (alpha) variant, B.1.351 (beta) variant, P.1 (gamma), and B.1.617.2 (delta) variant, were first detected in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Brazil, and India, and became a novel global concern (Ong et al., 2021; Sanches et al., 2021). The SARS-CoV-2 variants have greater ability of virus infectivity and immune escape, suggesting that the SARS-CoV-2 variants may result in poor treatment efficacy and prognosis for COVID-19 patients. In the past few months, many research teams from around the world have been conducting in vitro and in vivo studies of the virus, seeking effective prevention and control measures to prevent its spread. China is relatively fast and effective in the control of epidemic. We are, therefore, able to comprehensively analyze common domestic treatment methods and combined domestic and foreign research to jointly explore effective treatment programs for COVID-19, to provide guidance for the second wave of the epidemic.

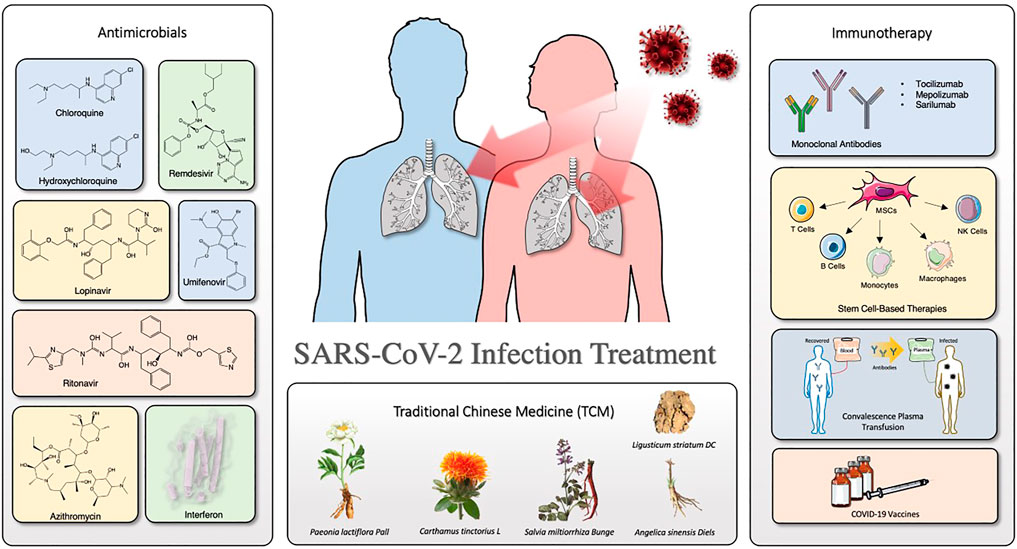

Many products including, but not limited to, traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs), antiviral drugs (e.g., chloroquine phosphate and alpha-interferon) (Wang and Zhu, 2020), monoclonal antibodies (e.g., tozumab combined with adamumab) (Sarkar et al., 2020), convalescence plasma, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Peng et al., 2020) have become the focus of our communication for COVID-19 treatment. The Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) shows a large number of TCM-related drugs studied for the treatment and prevention of COVID-19 (e.g., Lianhuaqingwen capsule, Shuanghuanglian oral liquid, Xuebijing injection, etc.) (Li H. et al., 2020), while Western drugs focus on antiviral drugs and immunotherapy (e.g., stem cell-based therapy, antibodies, etc.) (Ni et al., 2020a; Gulati et al., 2021). In the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7), it mentioned several antiviral drugs such as chloroquine (CQ), alpha-interferon (IFN-α), lopinavir/ritonavir, and umifenovir, and also mentioned immunotherapy, such as tocilizumab (Wei, 2020a; Zhao et al., 2020a; Wei, 2020b). Notably, as the adage, “old drug, new trick,” most of the antiviral drugs used for COVID-19 treatment are existing compounds screened for potential use based on mechanistic similarities to other viruses.

Herein, we summarize the clinical evaluation for COVID-19 treatment about the drugs mentioned in this review. Figure 1 depicts the overview of the organization of this review. Furthermore, we discuss recent representative progresses and considerations in the treatment for COVID-19, especially antimicrobials (antivirals and antibiotics/antibacterial), immunotherapy, and TCMs.

Antimicrobials

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

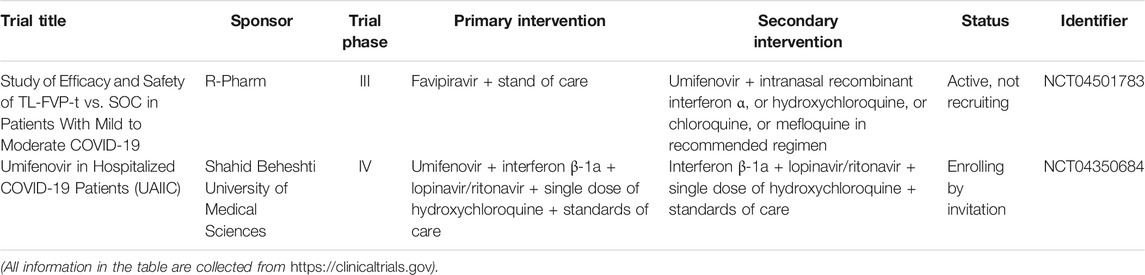

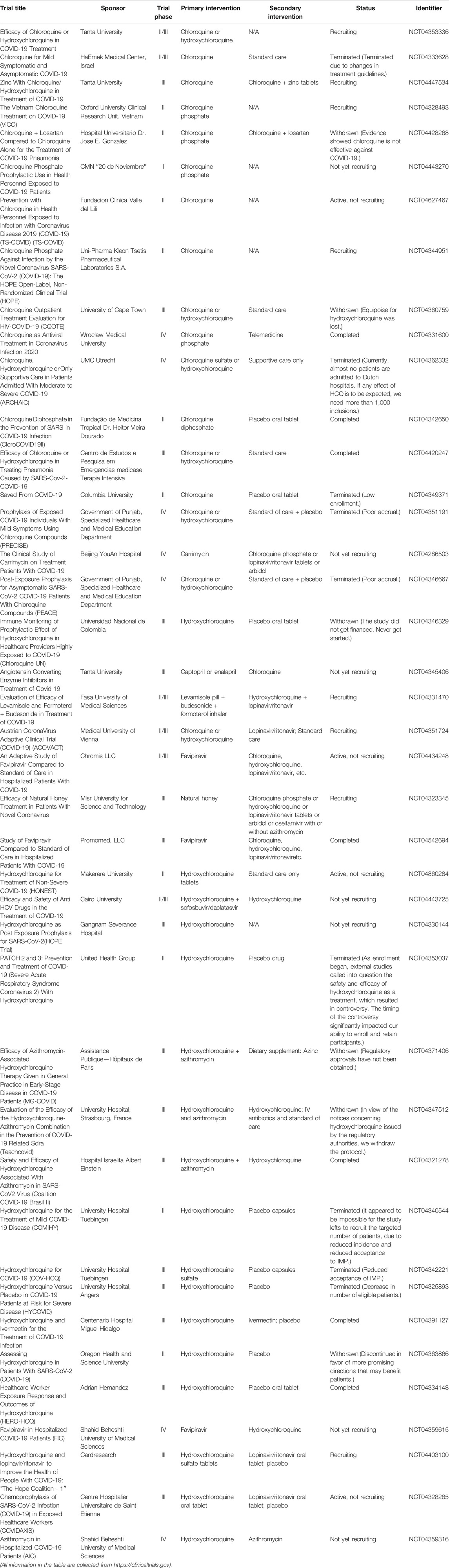

As a widely used antimalarial and immunomodulatory drug, chloroquine (CQ) shows a broad-spectrum antiviral activity. Table 1 summarizes the clinical trials of CQ and HCQ for the treatment of COVID-19. Some researchers indicated that CQ is effective against SARS-CoV-2 virus in early clinical studies (Huang et al., 2020c). Of note, chloroquine phosphate is undergoing some clinical trials regarding prophylactic use in health personnel (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04443270) and against infection by SARS-CoV-2 (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04344951). Evidence from a multicenter prospective observational study indicated that patients in CQ treatment group have shorter median time to achieve an undetectable viral RNA and shorter duration of fever; also, more importantly, no severe side effects were found during CQ treatment (Huang et al., 2020b). Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is an analog of CQ by replacing an ethyl group in CQ with a hydroxyethyl group (Zhou et al., 1878). Nowadays, ChiCTR conducts many clinical trials in China to examine the effectiveness and safety of CQ or HCQ against COVID-19 (Gao et al., 2020). A team from Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University investigated the effects of HCQ among 62 patients suffering from COVID-19 (www.chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR2000029559). As a result, Chen et al. found that HCQ could significantly shorten time to clinical recovery (TTCR) and improve pneumonia.

TABLE 1. Summary of clinical trials of chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) on COVID-19 treatment.

However, the high-quality clinical data showing a clear and reliable benefit of CQ or HCQ remains limited. Also, the CQ or HCQ treatment could induce severe cardiac side effects, imped innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses, and cause some uncertain effects (Meyerowitz et al., 2020). Commonly, QT prolongation and torsade de Pointes (TdP) occur on patients who are administered with CQ or HCQ (Blignaut et al., 2019). Hence, before CQ and HCQ treatment, an initial cardiac evaluation is necessary for COVID-19 patients (Zhou W. et al., 2020). Also, several follow-up evaluations, such as regular ophthalmological examination and cardiac monitor, are suggested for patients with short- or long-term treatment (Knox and Owens, 1966). Thus, using CQ or HCQ as a COVID-19 treatment was controversial, which results from their ocular, cardiac, and neuro toxicities (Oren et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020). Additionally, the certainty of evidence is low. Together, we would like to recommend monitoring the accumulative effect of long-term and/or high-dose CQ or HCQ in clinical settings. Also, researchers are not supposed to overstate or understate the clinical efficacy of CQ and HCQ on COVID-19 treatment.

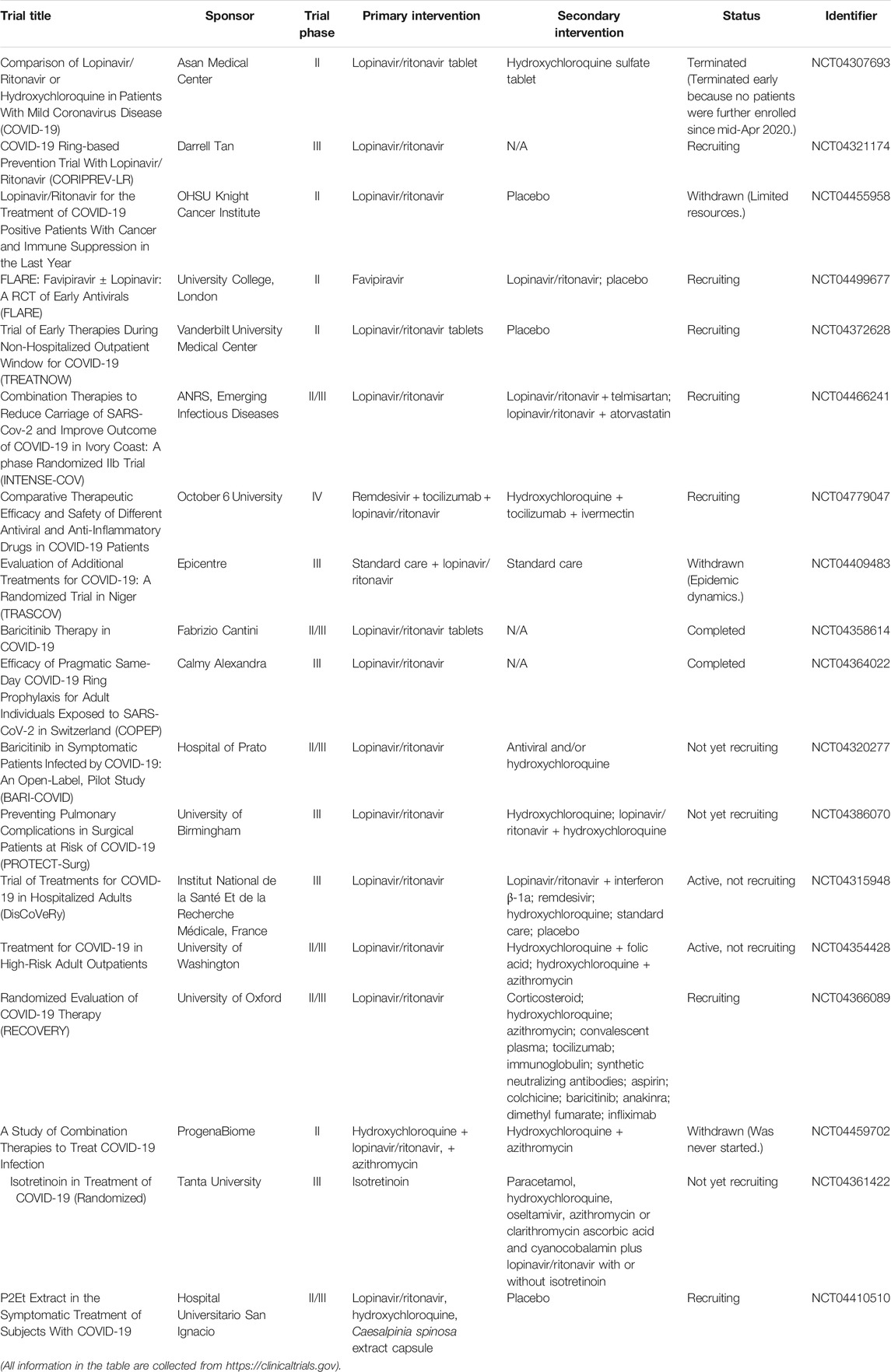

Lopinavir/ritonavir

Lopinavir/ritonavir tablets (brand name: Kaletra) are two structurally related protease inhibitors and works as antiretroviral agents (Cvetkovic and Goa, 2003). Table 2 summarizes the clinical trials of lopinavir/ritonavir on COVID-19 treatment. The mechanism of action of protease inhibitors is block cleavage in Gag and Gag-Pol, and result in producing immature and noninfectious virus particles (Adamson, 2012). Similar to CQ, lopinavir/ritonavir could act as potential antiviral agents against SARS in vitro and in patients with SARS infection (Chu et al., 2004). Also, lopinavir/ritonavir has favorable clinical outcome with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) after MERS reported in 2012 (Mo and Fisher, 2016; Arabi et al., 2018). Evidence from randomized trials indicated that lopinavir/ritonavir might improve outcomes in severe and critical COVID-19 patients, but it may induce mortality (Verdugo-Paiva et al., 2020). Moreover, it is reported that lopinavir/ritonavir could only improve a minority of throat-swab nucleic acid results in hospitals (Liu et al., 2020). Also, Cao et al. revealed that no beneficial response or clinical improvement was observed after treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir in a randomized, controlled, open-label trial with 199 in hospital patients suffering from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, even though improvement was found for some secondary endpoints (Cao et al., 2020; Stower, 2020). Together, the response of COVID-19 patients with lopinavir/ritonavir is not ideal and unfavorable. As the previous study showed, CQ had more potent effects to patients with COVID-19 than the use of lopinavir/ritonavir; hence, an ongoing clinical trial in China would like to access the effectiveness and safety of CQ and lopinavir/ritonavir for patients suffering from mild or general SARS-CoV-2 infection (www.chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR2000029741). Overall, available data on the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of lopinavir/ritonavir are still limited and investigational, thereby the clinical application of lopinavir/ritonavir should be considered and monitored carefully.

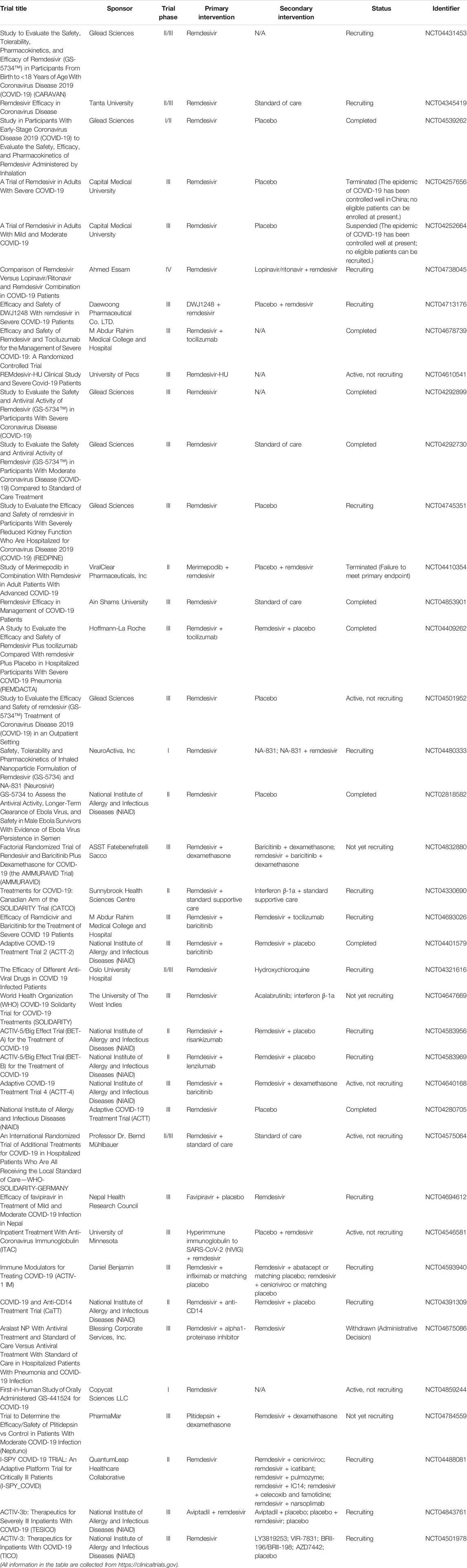

Remdesivir

Remdesivir (GS-5734, brand name: Veklury), as a nucleotide analog prodrug, is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug that acts on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and results in premature termination (Tchesnokov et al., 2019; Lamb, 2020). Table 3 shows the summary of clinical trials of remdesivir on COVID-19 treatment. As previously mentioned, Wang et al. showed that the EC50 value of remdesivir is 1.76 μM in Vero E6 cells, which suggests that remdesivir has high effectiveness in the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (Wang M. et al., 2020). More importantly, the intravenous remdesivir was administrated to the patient who was the first case diagnosed as SARS-CoV-2 infection in the United States (Holshue et al., 2020). No adverse effects were observed in association with the infusion; also, clinical benefits were found in patients. Another case demonstrated that remdesivir could accelerate recovery time by 4 days, which is a meaningful and optimistic progress for patients and medical systems (Jorgensen et al., 2020). Notably, remdesivir is FDA approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19. However, as more and more clinical cases were reported, the outcome of remdesivir treatment sometimes cannot achieve the expected effects on COVID-19 patients. Many researchers (Wang Y. et al., 2020) carried out a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial; as a result, Wang et al. found that remdesivir is not associated with statistically significant clinical improvement, even though some patients in the remdesivir treatment group had numerically faster time to improve than those in the placebo group. More importantly, remdesivir treatment was discontinued early due to the adverse events, including, but not limited to, nausea, constipation, and respiratory failure or acute respiratory distress. Overall, the certainty of evidence remains less. Since Nov. 2020, the WHO has issued a conditional recommendation against the use of remdesivir in COVID-19 patients.

Interferons

The interferons (IFNs) as glycoproteins have broad-spectrum antiviral effects (Lin and Young, 2014). The IFNs can be divided into three types based on the differences in the structures of their respective receptors. In detail, the IFNs are classified into type I IFNs (IFN-α/β), type II IFNs (IFN-γ), and type III IFNs (IFN-λ). Table 4 shows the summary of clinical trials of IFNs on COVID-19 treatment. Mantlo et al. (2020) demonstrated that IFN-α (EC50 = 1.35 IU/ml) and IFN-β (EC50 = 0.76 IU/ml) at clinically achievable concentrations could suppress the replication of SARC-CoV-2 in Vero cells. These findings provide a valuable fundamental for the potential use of IFN-α/β to against COVID-19. Zhou et al. accessed the efficacy of IFN-α2b and arbidol involving 77 hospitalized patients; as a result, researchers revealed that IFN-α2b with or without arbidol could significantly reduce the duration for detectable virus as well as the inflammatory markers (Zhou Q. et al., 2020). Usually, the IFNs are used in combination with other antiviral therapies (Mantlo et al., 2020). Of note, a group from China examined the effectiveness and safety profile of a triple antiviral therapy including IFN-β1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin with 86 patients suffering from mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection (Hung et al., 2020). Their results showed that the triple combination treatment is superior to lopinavir/ritonavir treatment alone with shorter viral shedding duration and hospital stay period.

However, some reports indicated that the application of IFN-λ have more advantages in COVID-19 treatment. The most outstanding profile of IFN-λ over IFN-α/β is the absence of pro-inflammatory effects (Prokunina-Olsson et al., 2020). This is because the response to IFN-λ administration localizes to epithelial cells, which could reduce side effects and inflammatory effects related to the systemic action from IFN-α/β treatment. Also, researchers showed that IFN-λ reduces the presence of virus in the lungs and prevents the induction of cytokine storm; hence, the application of IFN-λ could avoid pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Andreakos and Tsiodras, 2020). Overall, IFN-λ is a promising and potential therapeutic agent for patients suffering from COVID-19. Notably, more clinical study is necessary in the future.

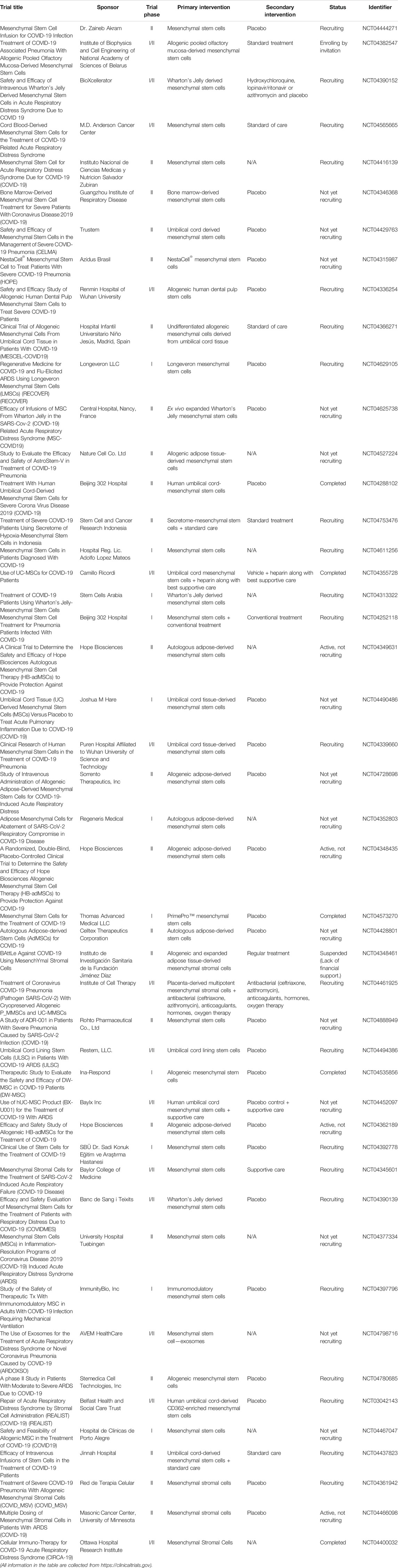

Umifenovir

Umifenovir (brand name: Arbidol, ARB) is an antiviral drug, which has the ability to inhibit the replication of influenza A and B virus through impeding the early membrane fusion event (Leneva et al., 2009). Table 5 indicates the summary of clinical trials of umifenovir for the treatment of COVID-19. Zhu et al. (2020) accessed the efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir and umifenovir involving 50 COVID-19 patients, 34 cases with lopinavir/ritonavir treatment, and 16 cases with umifenovir treatment. From the results, no side effects and developed pneumonia or ARDS were observed in both groups. More importantly, patients with umifenovir treatment have shorter duration of positive RNA test compared with those with lopinavir/ritonavir treatment; thus, the authors indicated that umifenovir may be superior to lopinavir/ritonavir against COVID-19. Similarly, Deng et al. (2020) demonstrated that lopinavir/ritonavir combined with umifenovir had more favorable clinical outcomes compared with lopinavir/ritonavir only in a retrospective cohort study. Furthermore, Nojomi et al. (2020) evaluated HCQ followed by lopinavir/ritonavir or HCQ followed by umifenovir among 100 patients with COVID-19. As a result, the researchers found that patients in the umifenovir group had shorter hospitalized duration and higher peripheral oxygen saturation rate, also had improvements in requiring ICU admissions, and chest CT involvement. Moreover, some studies showed that umifenovir was well-tolerated with mild gastrointestinal tract reaction and related to the lower mortality in COVID-19 cases (Jomah et al., 2020).

However, Lian et al. (2020) indicated that umifenovir is not relative to the improved response in non-ICU COVID-19 patients in a retrospective study. In detail, the study included 81 patients suffering from COVID-19, and evaluated several baseline clinical and laboratory factors. Of note, the patients with umifenovir treatment even had longer hospital stay duration than those patients in the control group. Hence, the authors indicated that umifenovir might not improve prognosis or accelerate SARS-CoV-2 clearance in non-ICU patients with COVID-19.

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic medication. Azithromycin binds to the 50S subunit of ribosome, and thereby prevents the mRNA translation and interferes with protein synthesis (Bakheit et al., 2014). Table 6 summarizes the clinical trials of azithromycin on COVID-19 treatment. Gautret et al. (2020) showed that azithromycin could reinforce the effectiveness of HCQ to clear the COVID-19 virus. Of note, the sample size was small, which only involved 20 cases. Also, researchers revealed that azithromycin combined with HCQ, or with lopinavir/ritonavir, could improve the clinical response and accelerate the COVID-19 virus clearance (Purwati et al., 2021). By contrast, Cavalcanti et al. (2020) reported that no improved clinical outcomes were observed in COVID-19 patients, suffering from mild to moderate COVID-19, treated with HCQ alone or with azithromycin compared with those with standard care in a multicenter, randomized, open-label, three-group, controlled trial involving 667 patients. Also, evidence from retrospective observational studies demonstrated that azithromycin in combination with HCQ did not induce favorable clinical outcomes for COVID-19 patients (Echeverría-Esnal et al., 2021).

Antibacterial/antibiotic drugs

It has been reported that bacterial coinfection happened in 3.5% of COVID-19 patients (Sieswerda et al., 2021). In other words, the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 have risk of bacterial infections. Sieswerda et al. (2021) recommended that the 5-day antibiotic therapy is required for the COVID-19 patients suffering with suspected bacterial respiratory infection after clinical improvements. However, their recommendation needs to be confirmed because unnecessary antibiotic treatment should be prevented. Also, some studies revealed that bacterial and fungal coinfection would occur in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, thereby the antimicrobial treatment regimen and stewardship interventions are necessary to control the exacerbating COVID-19 pandemic (Rawson et al., 2020). More importantly, antimicrobial resistance should be considered as the collateral effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and thus, proper trend for antibiotic stewardship interventions should be analyzed and prescribed in the emergency department (Pulia et al., 2020).

Immunotherapy

Monoclonal antibody

Tocilizumab

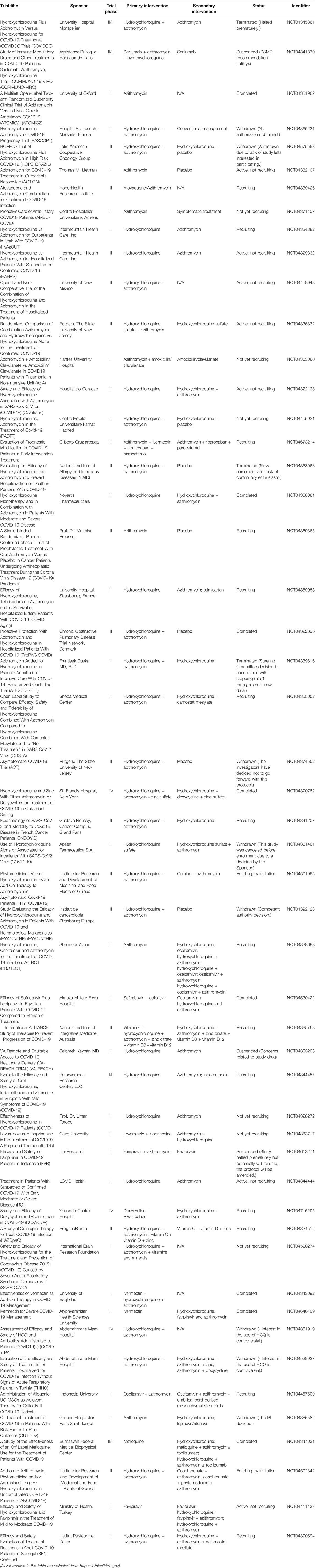

Tocilizumab (TCZ, trade name: Actemra) is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody (Sheppard et al., 2017). TCZ is well-tolerated without significant abnormalities after long-term toxicity tests on animals (Gabay et al., 2013). For the mechanism of action, TCZ specially binds membrane-bound interleukin-6 receptor (mIL-6R) and soluble interleukin-6 receptor (sIL-6R) and inhibits signal transduction (Ibrahim et al., 2020). It has been reported that COVID-19 induces higher plasma levels of cytokines including, but not limited to, IL-6, IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IFN-γ-inducible protein, etc., in ICU patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Chen N. et al., 2020; Huang C. et al., 2020), which refers to a cytokine storm in patients. Furthermore, several studies indicated that TCZ treatment could return the temperature to normal quickly and improve the respiratory function through blocking IL-6 receptors (Fu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Table 7 shows the clinical trials of TCZ on COVID-19 treatment. Luo et al. (2020) examined the efficacy of TCZ, as a recombinant humanized antihuman IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, and found that the serum IL-6 level decreased in 10 patients, while the persistent and dramatic increase in IL-6 was found in four patients who failed in the treatment. In contrast, Xu et al. (2020) recorded the clinical manifestation, computerized tomography (CT) scan image, and laboratory examinations to assess the effectiveness of TCZ in severe COVID-19 patients. Their results showed that TCZ has critical roles in pathogenesis and clinical improvement in patients. Moreover, Klopfenstein et al. (2020) performed a retrospective case-control study involving 20 patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and found that TCZ could reduce the number of ICU admissions and/or mortality compared with the patients without TCZ therapy. It should be noticed that the study performed by Klopfenstein et al. has some limitations, such as the small sample size and the retrospective nature of their work.

Interestingly, Stone et al. (2020) conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04356937) with a larger sample size (243 patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection). The results from the study of Stone et al. demonstrated that TCZ is not effective in preventing intubation or death. However, some benefits, such as fewer serious infections in patients receiving TCZ therapy, cannot be ignored. Most recently, Salama et al. (2021) performed a trial enrolled with 389 COVID-19 patients (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04372186). The results showed that TCZ cannot improve survival rate; it only reduced the possibility of progression to the composite outcome of mechanical ventilation or death for the patients who were not receiving mechanical ventilation. Currently, TCZ undergoes several phase III clinical trials (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04423042, NCT04356937, NCT04403685, etc.) to further understand the TCZ treatment as a supportive care option in alleviating the severe respiratory symptoms correlated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Alzghari and Acuña, 2020). Overall, TCZ appears to be an effective treatment for COVID-19 patients to calm the inflammatory storm and to reduce mortality. Notably, the efficacy of TCZ is controversial and remains to be further determined.

Mepolizumab

Mepolizumab (brand name: Nucala) is a human monoclonal antibody medication used for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma, eosinophilic granulomatosis, and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) (Mukherjee et al., 2014; Ennis et al., 2019). Mepolizumab binds to IL-5 and prevents it from binding to its receptor on the surface of eosinophil white blood cells. Notably, some experts recommended to continue the mepolizumab therapy in COVID-19 patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, but the concern is that eosinopenia, which may serve as a diagnostic indicator for COVID-19 disease, may be a risk factor for worse disease outcomes (Li Q. et al., 2020; Du et al., 2020; Bousquet et al., 2021). In other words, it is a challenge to manage patients with severe eosinophilic asthma infected by SARS-CoV-2. Aksu et al. (2021) reported that no evidence of loss of asthma control was observed during mepolizumab therapy in a woman patient with asthma infected by SARS-CoV-2. In addition, Azim et al. (2021) observed the outcomes from four patients receiving mepolizumab treatment. The researchers found that all four patients had a further reduction in their eosinophil counts within the reference range at the presentation with SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the underlying mechanism is not fully investigated, and subsequently recovered without any immediate evidence of long-term respiratory outcomes. Of note, one of four patients required hospitalization and ventilatory support. They thereby suggested that the mepolizumab therapy should be continued without any changed outcomes in the COVID-19 course. However, evidence from Eger et al. (2020) involved 634 severe asthma patients diagnosed with COVID-19 showed that patients with severe asthma receiving mepolizumab therapy have a more severe course of COVID-19 and an increasing risk of severity of COVID-19 compared with the general population. Overall, because the relevant data are limited, and the guideline is currently absent, maintaining or postponing mepolizumab treatment until the patient recovers from SARS-CoV-2 infection should be a case-by-case based decision for COVID-19 patients with severe asthma.

Sarilumab

Sarilumab (brand name: Kevzara) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptor. In 2017, FDA approved sarilumab for rheumatoid arthritis treatment (Khiali et al., 2021). It has reported that severe COVID-19 disease is characterized by elevated serum levels of C reactive protein (CRP) and cytokines, including, but not limited to, IFN-γ, IL-8, and IL-6 (Conti et al., 2020; Mo et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2020). Hence, this result provides a clue that anti-IL-6 agents have the possibility against SARS-CoV-2 infection. In a retrospective case report involving 15 COVID-19 patients, early intervention with sarilumab could have clinical improvement with decreased CRP level to patients with COVID-19 disease. More importantly, serum levels of CRP could be a potential biomarker for treatment response (Montesarchio et al., 2020). An open-label cohort study assessed the clinical outcome of sarilumab among 28 patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 compared with 28 contemporary patients receiving standard of care alone (Della-Torre et al., 2020). The results indicated that no significant difference was observed between sarilumab and standard of care. Of note, the clinical improvement suggested that sarilumab is relative to faster recovery in a subset of patients showing minor lung consolidation at baseline. In addition, there are several ongoing clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of sarilumab either plus standard of care (Caballero Bermejo et al., 2020) or combined with corticosteroids (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04357808) (Garcia-Vicuña et al., 2020) on COVID-19 disease. To date, the overall evaluation toward sarilumab on COVID-19 disease is much positive, which needs further tracking in the future.

Stem cell-based therapy

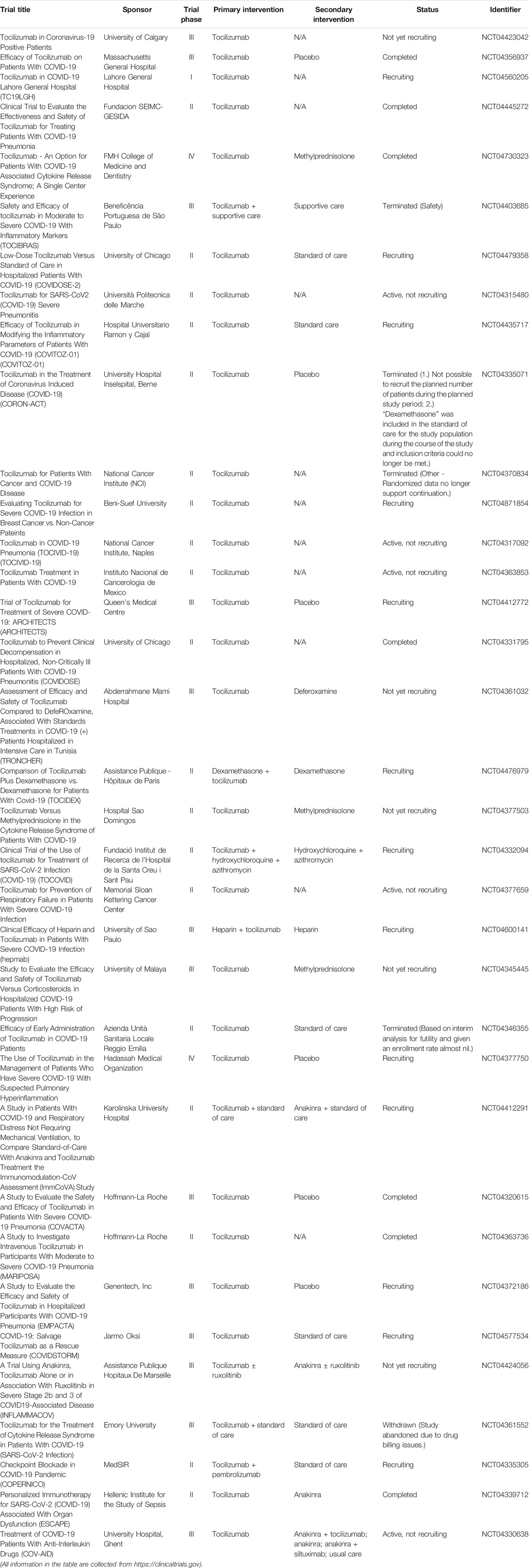

To date, most studies regarding stem-based therapy to SARS-CoV-2 infection have focused on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Choudhery and Harris, 2020). MSC-based therapy has the ability to suppress the cytokine storm by secreting anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptosis, and antifibrosis cytokines. Also, MSCs contribute to antibacterial activity, as well as tissue repair and regeneration (Sadeghi et al., 2020). Table 8 shows clinical trials of MSCs on COVID-19 treatment. For patients suffering from COVID-19, MSCs would repair damaged alveolar epithelial cells and blood vessels, and also prevent pulmonary fibrosis (Chen et al., 2018; Leeman et al., 2019; Zanoni et al., 2019; Afra and Matin, 2020; Li Z. et al., 2020; Golchin et al., 2020). Seven COVID-19 patients who received intravenous transplantation of MSCs had significantly improved pulmonary function in 2 days after transplantation (Leng et al., 2020). Notably, the increased peripheral lymphocytes and IL-10 level, decreased C-reactive protein (CRP) and TNF-α level, and disappeared overactivated cytokine-secreting immune cells were observed within 14 days after MSC injection. Interestingly, Jayaramayya et al. reported that MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) may be an option to improve the clinical response to COVID-19 patients (Jayaramayya et al., 2020). A phase I clinical trial investigated the use of MSC-Exo inhalation to alleviate COVID-19-induced symptoms (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04276987). Moreover, MSC-like derivatives have acceptable safety and efficacy for COVID-19 treatment in preclinical and clinical studies (Li Z. et al., 2020).

However, some limitations remain to be considered (Sadeghi et al., 2020). First, some patients with, including, but not limited to, a history of malignant tumor, coinfections of other respiratory viruses, and pregnant woman are not eligible to evolve in clinical trials. Most clinical trials worldwide remain in phase I and II, and comprehensive results are not clear. Furthermore, it is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of MSC therapy alone when coadministration with other conventional drugs, such as remdesivir or dexamethasone, in many cases. Importantly, the standard therapeutic protocol, such as administration route, dosage, and transplantation frequency, needs to be determined. Nevertheless, the MSC profile on the immune system provides researchers evidence that it may be a good candidate as a combination therapy of infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Overall, MSC-based therapy appears to be a potential and promising therapeutic method to overcome SARS-CoV-2 infection.

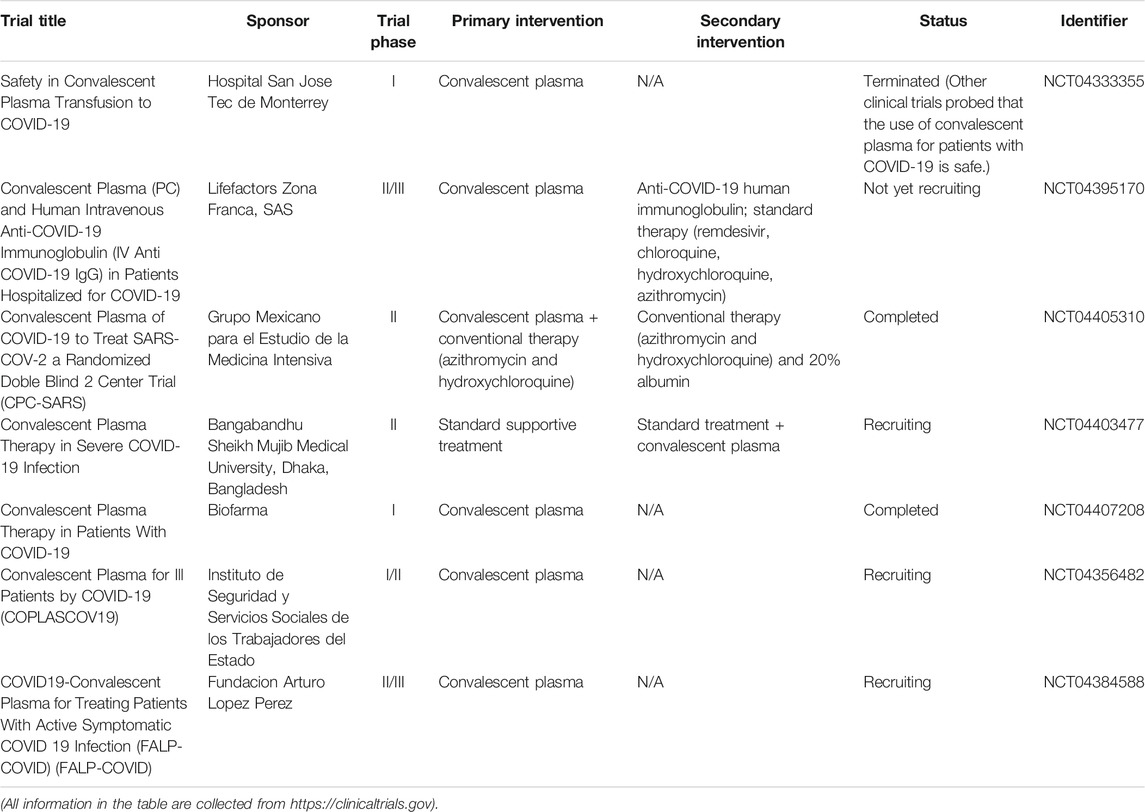

Convalescence plasma transfusion

Convalescent plasma treatment provides immediate immunity by passive polyclonal antibody administration (Mair-Jenkins et al., 2015). The efficacy of convalescent plasma transfusion may result from viremia suppression (Chen L. et al., 2020). It has reported that convalescent plasma treatment can be used to improve the survival rate on patients with severe acute respiratory syndromes of viral etiology (Mair-Jenkins et al., 2015). Several studies indicated that SARS patients who were treated with convalescent plasma had a shorter hospital stay and lower mortality than those who were not treated with convalescent plasma (Soo et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2005; Lai, 2005). Table 9 shows the clinical trials of convalescent plasma transfusion on COVID-19 treatment. Based on the findings from recent studies, initiating treatment no later than 5 days may be the most appropriate (Woelfel et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020b). Tiberghien et al. (2020) recommend that convalescent plasma administration at the early phases of the disease in patients at high risk of deleterious evolution may reduce the frequency of patient deterioration and, thereby, COVID-19 mortality. Also, close monitoring is necessary to detect any unintended side effects. However, a randomized trial (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04383535) evolved in 228 COVID-19 patients to evaluate the clinical status after convalescent plasma intervention was added to standard treatment (Simonovich et al., 2021). Unfortunately, no significant differences were found in clinical outcomes or overall mortality between patients infused with convalescent plasma added to standard treatment and those who received standard treatment alone within 30 days. Similarly, an open-label, multicenter, randomized clinical trial (www.chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR2000029757) was performed in seven medical centers with 103 COVID-19 patients (Li L. et al., 2020). The results showed that convalescent plasma therapy in addition to standard treatment, compared with standard treatment alone, did not result in a significant improvement in time to clinical improvement within 28 days. Of note, it is known that other treatments, including antiviral drugs, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin, have the possibility to affect the relationship between convalescent plasma and antibody level (Luke et al., 2006). Thus, it is controversial whether it is worthwhile to examine the safety and efficacy of convalescent plasma intervention against SARS-CoV-2 infection in further randomized clinical trials.

Vaccines

An efficacious vaccine is critical to prevent morbidity and mortality caused by COVID-19. There are four categories of COVID-19 vaccines under clinical evaluation, including whole-pathogen vaccines (inactivated vaccines), subunit vaccines, and nucleic acid (DNA and mRNA) vaccines. However, defining and assessing an efficacious vaccine is complex. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection, an efficacious vaccine could reduce the likelihood of an infection in an individual, severity of a disease in an individual, or the degree of transmission within a population (Hodgson et al., 2021). The comprehensive understanding of SARS-Cov-2 is unclear and evolving, thereby the outcomes for a COVID-19 vaccine are critically appraised with scientific rigor to understand their generalizability and clinical significance.

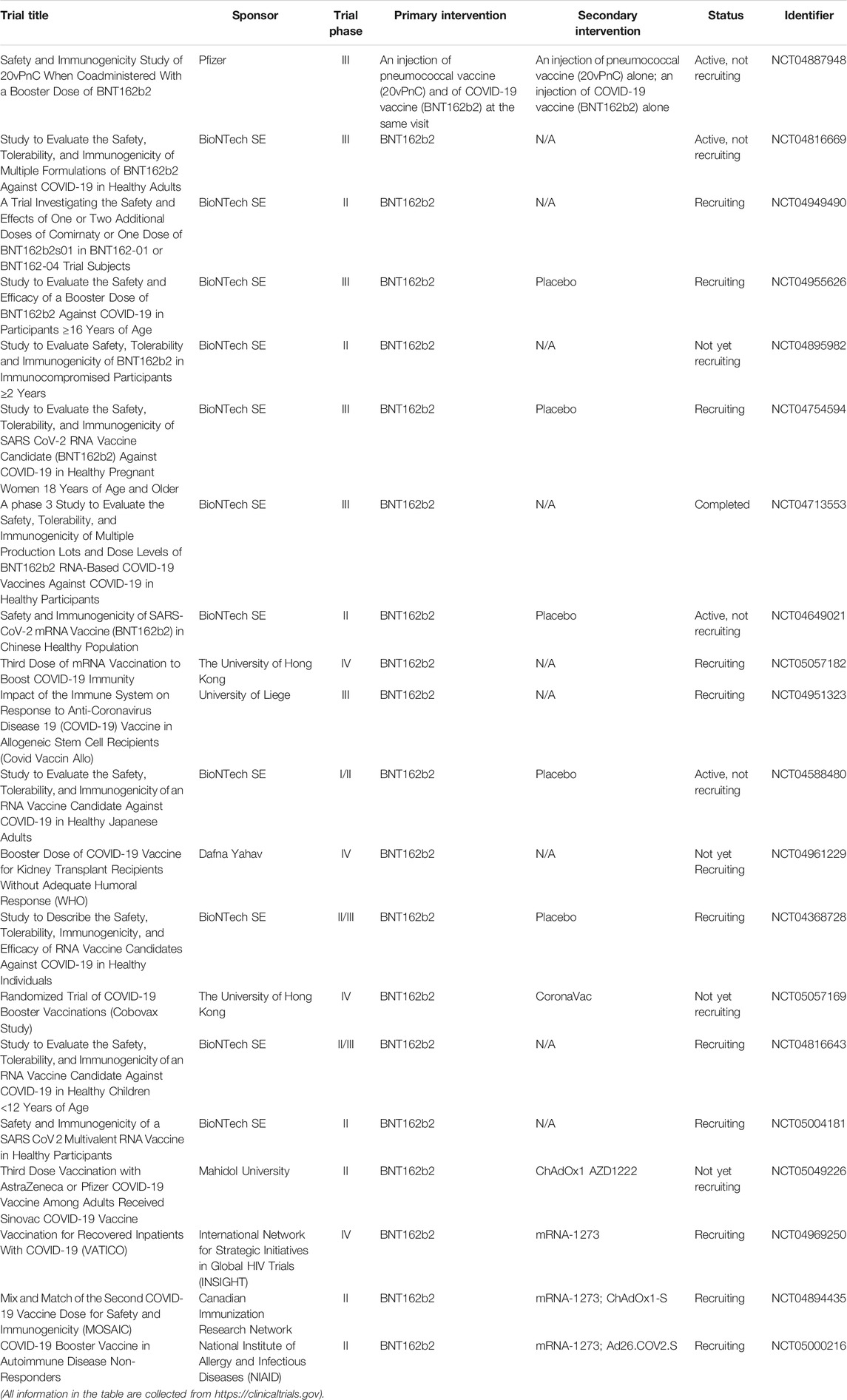

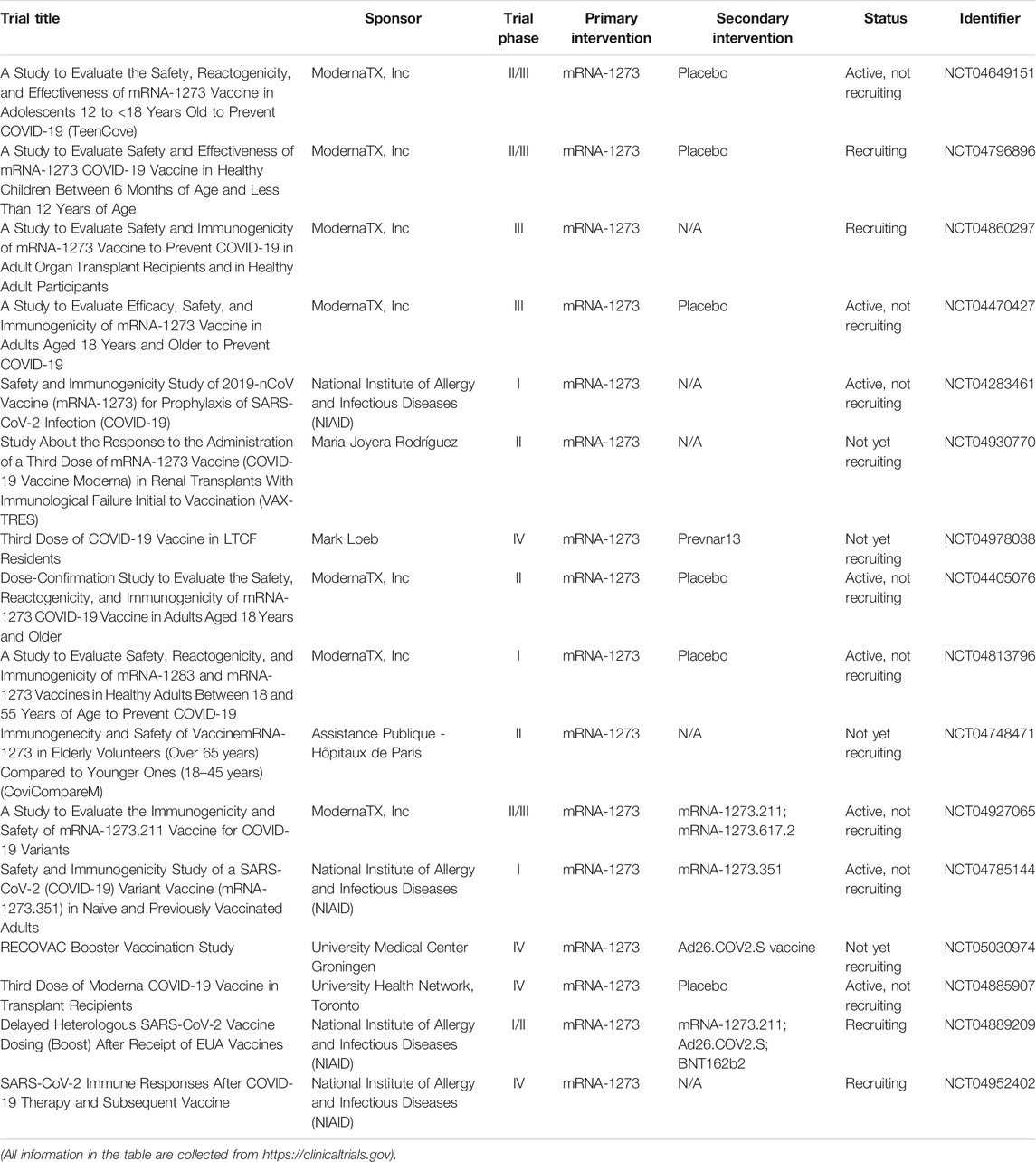

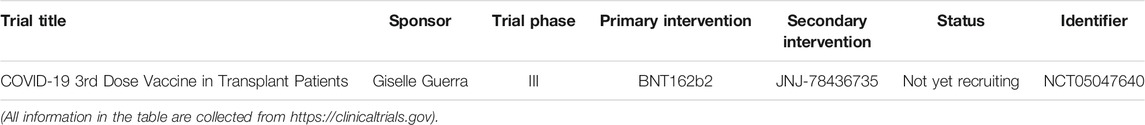

Currently, three vaccines are authorized in the United States: Pfizer-BioNTech (Name: BNT162b2), Moderna (Name: mRNA-1273), and Johnson and Johnson/Janssen (Name: JNJ-78436735). Tables 10–12 summarize the clinical trials of these vaccines for the treatment of COVID-19. Of note, people under 12 years old are not eligible to receive vaccine produced by Pfizer-BioNTech, and people under 18 years old are not eligible to receive vaccines produced by Moderna and Johnson and Johnson/Janssen. Kamidani et al. (2021) indicated that children are supposed to have the opportunity to be included in clinical trials in parallel to ongoing adult phase III clinical trials. It is because the development of a pediatric COVID-19 vaccine could prevent disease and alleviate downstream effects including social isolation and interruption in education, thereby enabling children to re-engage in their world. Considering the SARS-CoV-2 variants, evidence from Polack et al. (2020) proved that BNT162b2 is 95% effective against SARS-CoV-2 infection. A 6 months of follow-up evaluation from Thomas et al. (2021) indicated that BNT162b2 has a favorable safety profile and effectively prevents COVID-19 for up to 6 months including the beta variant even though there is a gradual decline in effectiveness. Bernal et al. (Lopez Bernal et al., 2021) reported that the efficacy of the one-shot BNT162b2 vaccine is 30.7% among individuals with the delta variant, while the efficacy is 48.7% among individuals with the alpha variant. The efficacy of two shots of BNT162b2 vaccine is 88.0% among individuals with the delta variant, while the efficacy is 93.7% among individuals with the alpha variant. In other words, as CDC recommendation, vaccination against COVID-19 is the best way to stop the spread of these predominate COVID-19 strains.

TABLE 10. Summary of clinical trials of BNT162b2 vaccine (produced by Pfizer-BioNTech) on COVID-19 treatment.

TABLE 11. Summary of clinical trials of mRNA-1273 vaccine (produced by Moderna) on COVID-19 treatment.

TABLE 12. Summary of clinical trials of JNJ-78436735 vaccine (produced by Johnson and Johnson/Janssen) on COVID-19 treatment.

Most recently, a COVID-19 vaccine booster emerged to help individuals build enough protection after vaccination. According to the information from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, https://www.cdc.gov), individuals who have received their second dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (produced by either Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna) for 8 months are eligible to get a booster shot. Currently, for individuals who got Johnson and Johnson/Janssen vaccine, there is not enough data to support getting an mRNA vaccine dose.

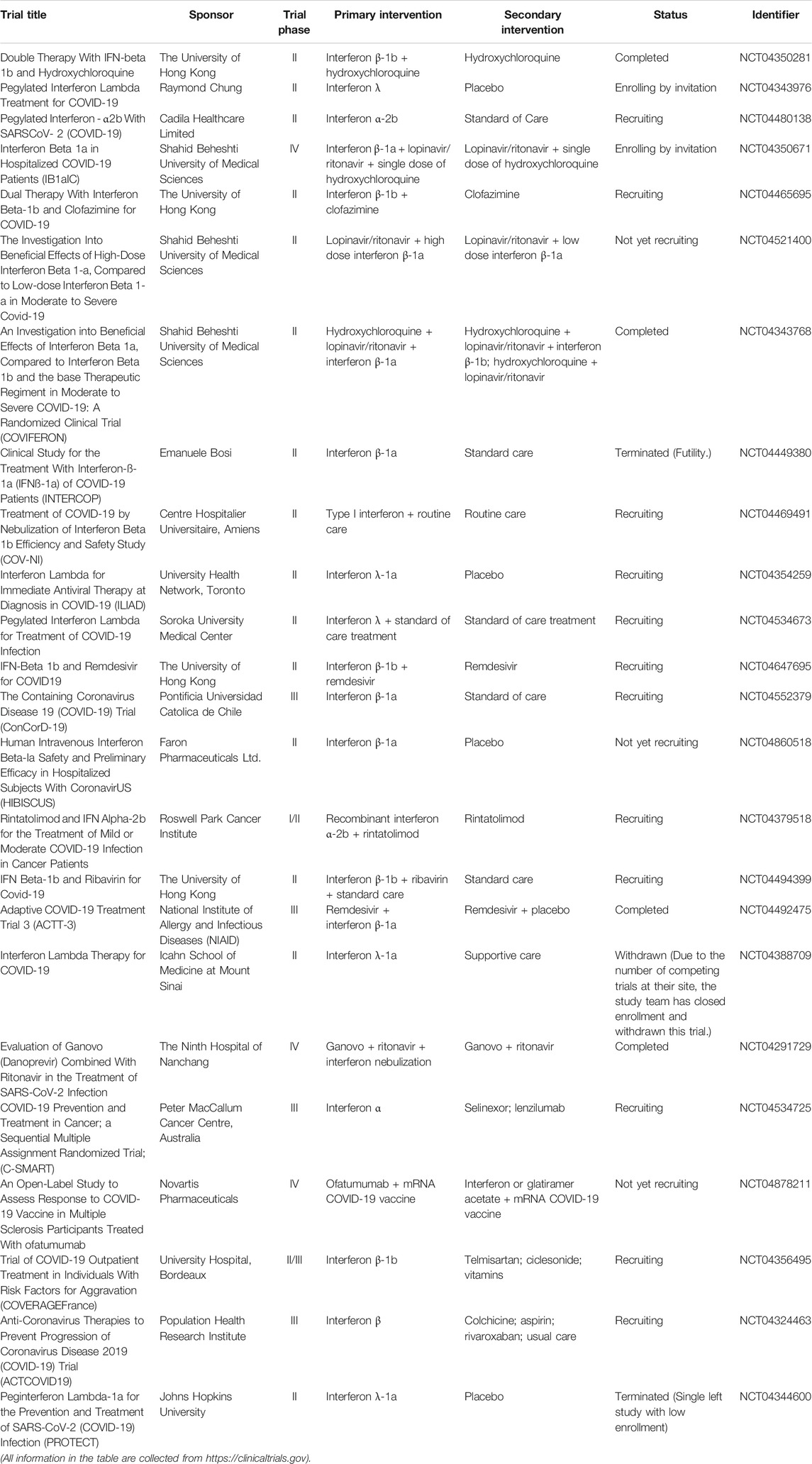

Traditional Chinese medicine

Xuebijing injection (XBJ) consists of Carthamus tinctorius L., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Ligusticum striatum DC., Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, and Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels (Shi et al., 2017). XBJ constructs a “drug-ingredient-target-pathway” effector network to exert its therapeutic effects on COVID-19 prevention and treatment (Zheng et al., 2020). Guo et al. (2020) conducted a retrospective case-control study to determine the efficacy of XBJ on SARS-CoV-2 infection with 42 patients who received routine treatment combined with XBJ (observation group) and 16 patients who received routine treatment alone (control group). The results showed that patients in the observation group had a significant reduction in body temperature, improvement in CT imaging results, and shorter time in a negative nucleic acid test recovery relative to those in the control group. Also, improvement in IL-6 levels was found in the observation group compared with those in the control group, while TNF-α and IL-10 levels did not show significant differences between the two groups. In addition, 284 COVID-19 patients were enrolled in a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of Lianhuaqingwen (LH) capsule (Hu et al., 2021). Compared with patients in the control group (received usual treatment alone), patients with usual treatment in combination with LH capsule treatment had higher recovery rate, shorter median time to symptom recovery, and higher rate of improvements in chest CT manifestations and clinical cure. Hence, both XBJ and LH capsules could be considered to ameliorate clinical symptoms of COVID-19. Moreover, Ni et al. reported that using Western medicine combined with Chinese traditional patent medicine Shuanghuanglian oral liquid (SHL) has expected therapeutic outcomes to COVID-19 patients, and thereby warrants further clinical trials (Ni et al., 2020b).

Concluding remarks

For antimicrobial drugs, the acquired drug resistance should be considered and explored. The use of CQ and HCQ is controversial due to their toxicity and side effects. Moreover, lopinavir/ritonavir, umifenovir, and azithromycin appear to be promising therapeutic drugs even though some studies do not show ideal and unfavorable clinical outcomes on COVID-19 patients. The IFNs are usually used in addition to other antiviral drugs. Also, the application of IFN-λ have more advantages than other types of IFNs in COVID-19 treatment.

TCZ, an antibody, has the ability to improve clinical responses on COVID-19 patients by suppressing inflammatory storm and, thereby, reduces mortality cases. Mepolizumab, as an antibody medication for asthma, may increase the risk of severe COVID-19 and induce a more severe course of COVID-19, particularly for COVID-19 patients with severe asthma receiving mepolizumab therapy. Sarilumab, as an FDA-approved antibody medication for rheumatoid arthritis treatment, shows clinical improvement with decreased CRP level to patients with COVID-19 disease. Furthermore, stem cell-based therapy, especially MSCs, could improve clinical symptoms and repair tissue caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of note, the standard protocol of MSCs therapy needs to be determined. Additionally, COVID-19 patients who received convalescent plasma transfusion in addition to standard treatment shows no clinical differences compared with those who received standard treatment alone. Therefore, it is controversial whether it is worthwhile to assess the safety and efficacy of convalescent plasma intervention against SARS-CoV-2 infection in further randomized clinical trials.

In addition, TCMs play a critical role in ameliorating and alleviating clinical symptoms on COVID-19 patients. Also, it is known that TCMs in combination with Western medicine is a potential therapeutic strategy against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

To date, remdesivir is FDA approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19. Also, several vaccines are authorized and recommended in the United States and other countries. Most treatment regimens against the COVID-19 pandemic are controversial and remain under preclinical and clinical trials. Overall, more comprehensive information regarding each treatment regimen is uncertain and needs to be further explored.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Second Batch of Outstanding Young Medical Talents in Ganzhou City Health System (Jiangxi, China). The author (YY) thanks the support as a teaching fellow from Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, St. John’s University (New York, United States).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yangmin Chen (St. John’s University) for editing the article. Thanks to all the peer reviewers and editors for their opinions and suggestions.

References

Adamson, C. S. (2012). Protease-Mediated Maturation of HIV: Inhibitors of Protease and the Maturation Process. Mol. Biol. Int. 2012, 604261. doi:10.1155/2012/604261

Afra, S., and Matin, M. M. (2020). Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Bioengineered Blood Vessels in Comparison with Other Eligible Cell Sources. Cell Tissue Res 380 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1007/s00441-019-03161-0

Aksu, K., Yesilkaya, S., Topel, M., Turkyilmaz, S., Ercelebi, D. C., Oncul, A., et al. (2021). COVID-19 in a Patient with Severe Asthma Using Mepolizumab. Allergy Asthma Proc. 42 (2), e55–e57. doi:10.2500/aap.2021.42.200125

Alzghari, S. K., and Acuña, V. S. (2020). Supportive Treatment with Tocilizumab for COVID-19: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Virol. 127, 104380. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104380

Andreakos, E., and Tsiodras, S. (2020). COVID-19: Lambda Interferon against Viral Load and Hyperinflammation. EMBO Mol. Med. 12 (6), e12465. doi:10.15252/emmm.202012465

Arabi, Y. M., Alothman, A., Balkhy, H. H., Al-Dawood, A., AlJohani, S., Al Harbi, S., et al. (2018). Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a Combination of Lopinavir-Ritonavir and Interferon-Β1b (MIRACLE Trial): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 19 (1), 81. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0

Azim, A., Pini, L., Khakwani, Z., Kumar, S., and Howarth, P. (2021). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in Those on Mepolizumab Therapy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 126 (4), 438–440. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.01.00610.1097/COH.0000000000000658

Bakheit, A. H., Al-Hadiya, B. M., and Abd-Elgalil, A. A. (2014). Azithromycin. Profiles Drug Subst. Excip Relat. Methodol. 39, 1–40. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800173-8.00001-5

Bevova, M. R., Netesov, S. V., and Aulchenko, Y. S. (2020). The New Coronavirus COVID-19 Infection. Mol. Gen. Microbiol. Virol. 35 (2), 53–60. doi:10.3103/s0891416820020044

Blignaut, M., Espach, Y., van Vuuren, M., Dhanabalan, K., and Huisamen, B. (2019). Revisiting the Cardiotoxic Effect of Chloroquine. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 33 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10557-018-06847-9

Bousquet, J., Jutel, M., Akdis, C. A., Klimek, L., Pfaar, O., Nadeau, K. C., et al. (2021). ARIA-EAACI Statement on Asthma and COVID-19 (June 2, 2020). Allergy 76 (3), 689–697. doi:10.1111/all.14471

Caballero Bermejo, A. F., Ruiz-Antorán, B., Fernández Cruz, A., Diago Sempere, E., Callejas Díaz, A., Múñez Rubio, E., et al. (2020). Sarilumab versus Standard of Care for the Early Treatment of COVID-19 Pneumonia in Hospitalized Patients: SARTRE: a Structured Summary of a Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Trials 21 (1), 794. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04633-3

Cao, B., Wang, Y., Wen, D., Liu, W., Wang, J., Fan, G., et al. (2020). A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (19), 1787–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001282

Cavalcanti, A. B., Zampieri, F. G., Rosa, R. G., Azevedo, L. C. P., Veiga, V. C., Avezum, A., et al. (2020). Hydroxychloroquine with or without Azithromycin in Mild-To-Moderate Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 (21), 2041–2052. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019014

Chen, L., Xiong, J., Bao, L., and Shi, Y. (2020a). Convalescent Plasma as a Potential Therapy for COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20 (4), 398–400. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30141-9

Chen, N., Zhou, M., Dong, X., Qu, J., Gong, F., Han, Y., et al. (2020b). Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 99 Cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a Descriptive Study. Lancet 395 (10223), 507–513. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7

Chen, S., Cui, G., Peng, C., Lavin, M. F., Sun, X., Zhang, E., et al. (2018). Transplantation of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates Pulmonary Fibrosis of Silicosis via Anti-inflammatory and Anti-apoptosis Effects in Rats. Stem Cel Res Ther 9 (1), 110. doi:10.1186/s13287-018-0846-9

Cheng, Y., Wong, R., Soo, Y. O., Wong, W. S., Lee, C. K., Ng, M. H., et al. (2005). Use of Convalescent Plasma Therapy in SARS Patients in Hong Kong. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24 (1), 44–46. doi:10.1007/s10096-004-1271-9

Choudhery, M. S., and Harris, D. T. (2020). Stem Cell Therapy for COVID-19: Possibilities and Challenges. Cell Biol Int 44 (11), 2182–2191. doi:10.1002/cbin.11440

Chu, C. M., Cheng, V. C., Hung, I. F., Wong, M. M., Chan, K. H., Chan, K. S., et al. (2004). Role of Lopinavir/ritonavir in the Treatment of SARS: Initial Virological and Clinical Findings. Thorax 59 (3), 252–256. doi:10.1136/thorax.2003.012658

Conti, P., Ronconi, G., Caraffa, A., Gallenga, C. E., Ross, R., Frydas, I., et al. (2020). Induction of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and Lung Inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): Anti-inflammatory Strategies. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost Agents 34 (2), 327–331. doi:10.23812/conti-e

Cvetkovic, R. S., and Goa, K. L. (2003). Lopinavir/ritonavir: a Review of its Use in the Management of HIV Infection. Drugs 63 (8), 769–802. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363080-00004

Della-Torre, E., Campochiaro, C., Cavalli, G., De Luca, G., Napolitano, A., La Marca, S., et al. (2020). Interleukin-6 Blockade with Sarilumab in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia with Systemic Hyperinflammation: an Open-Label Cohort Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79 (10), 1277–1285. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218122

Deng, L., Li, C., Zeng, Q., Liu, X., Li, X., Zhang, H., et al. (2020). Arbidol Combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r Alone against Corona Virus Disease 2019: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Infect. 81 (1), e1–e5. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.002

Du, Y., Tu, L., Zhu, P., Mu, M., Wang, R., Yang, P., et al. (2020). Clinical Features of 85 Fatal Cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. A Retrospective Observational Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201 (11), 1372–1379. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC

Echeverría-Esnal, D., Martin-Ontiyuelo, C., Navarrete-Rouco, M. E., De-Antonio Cuscó, M., Ferrández, O., Horcajada, J. P., et al. (2021). Azithromycin in the Treatment of COVID-19: a Review. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 19 (2), 147–163. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1813024

Eger, K., Hashimoto, S., Braunstahl, G. J., Brinke, A. T., Patberg, K. W., Beukert, A., et al. (2020). Poor Outcome of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Patients with Severe Asthma on Biologic Therapy. Respir. Med. 177, 106287. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106287

Ennis, D., Lee, J. K., and Pagnoux, C. (2019). Mepolizumab for the Treatment of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 19 (7), 617–630. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1623875

Fu, B., Xu, X., and Wei, H. (2020). Why Tocilizumab Could Be an Effective Treatment for Severe COVID-19. J. Transl Med. 18 (1), 164. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3

Gabay, C., Emery, P., van Vollenhoven, R., Dikranian, A., Alten, R., Pavelka, K., et al. (2013). Tocilizumab Monotherapy versus Adalimumab Monotherapy for Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADACTA): a Randomised, Double-Blind, Controlled Phase 4 Trial. Lancet 381 (9877), 1541–1550. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60250-0

Gao, J., Tian, Z., and Yang, X. (2020). Breakthrough: Chloroquine Phosphate Has Shown Apparent Efficacy in Treatment of COVID-19 Associated Pneumonia in Clinical Studies. Biosci. Trends 14 (1), 72–73. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01047

Garcia-Vicuña, R., Abad-Santos, F., González-Alvaro, I., Ramos-Lima, F., and Sanz, J. S. (2020). Subcutaneous Sarilumab in Hospitalised Patients with Moderate-Severe COVID-19 Infection Compared to the Standard of Care (SARCOVID): a Structured Summary of a Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Trials 21 (1), 772. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04588-5

Gautret, P., Lagier, J. C., Parola, P., Hoang, V. T., Meddeb, L., Mailhe, M., et al. (2020). Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin as a Treatment of COVID-19: Results of an Open-Label Non-randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56 (1), 105949. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949

Golchin, A., Seyedjafari, E., and Ardeshirylajimi, A. (2020). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for COVID-19: Present or Future. Stem Cel Rev Rep 16 (3), 427–433. doi:10.1007/s12015-020-09973-w

Gulati, S., Muddasani, R., Gustavo Bergerot, P., and Pal, S. K. (2021). Systemic Therapy and COVID19: Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy. Urol. Oncol. 39 (4), 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.12.022

Guo, H., Zheng, J., Huang, G., Xiang, Y., Lang, C., Li, B., et al. (2020). Xuebijing Injection in the Treatment of COVID-19: a Retrospective Case-Control Study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 9 (5), 3235–3248. doi:10.21037/apm-20-1478

Hodgson, S. H., Mansatta, K., Mallett, G., Harris, V., Emary, K. R. W., and Pollard, A. J. (2021). What Defines an Efficacious COVID-19 Vaccine? A Review of the Challenges Assessing the Clinical Efficacy of Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21 (2), e26–e35. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30773-8

Holshue, M. L., DeBolt, C., Lindquist, S., Lofy, K. H., Wiesman, J., Bruce, H., et al. (2020). First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (10), 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

Hu, K., Guan, W. J., Bi, Y., Zhang, W., Li, L., Zhang, B., et al. (2021). Efficacy and Safety of Lianhuaqingwen Capsules, a Repurposed Chinese Herb, in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 85, 153242. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153242

Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., et al. (2020a). Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395 (10223), 497–506. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

Huang, M., Li, M., Xiao, F., Pang, P., Liang, J., Tang, T., et al. (2020b). Preliminary Evidence from a Multicenter Prospective Observational Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Chloroquine for the Treatment of COVID-19. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7 (9), 1428–1436. doi:10.1101/2020.04.26.20081059

Huang, M., Tang, T., Pang, P., Li, M., Ma, R., Lu, J., et al. (2020c). Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. J. Mol. Cel Biol 12 (4), 322–325. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjaa014

Hung, I. F., Lung, K. C., Tso, E. Y., Liu, R., Chung, T. W., Chu, M. Y., et al. (2020). Triple Combination of Interferon Beta-1b, Lopinavir-Ritonavir, and Ribavirin in the Treatment of Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19: an Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet 395 (10238), 1695–1704. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31042-4

Ibrahim, Y. F., Moussa, R. A., Bayoumi, A. M. A., and Ahmed, A. F. (2020). Tocilizumab Attenuates Acute Lung and Kidney Injuries and Improves Survival in a Rat Model of Sepsis via Down-Regulation of NF-κB/JNK: a Possible Role of P-Glycoprotein. Inflammopharmacology 28 (1), 215–230. doi:10.1007/s10787-019-00628-y

Jayaramayya, K., Mahalaxmi, I., Subramaniam, M. D., Raj, N., Dayem, A. A., Lim, K. M., et al. (2020). Immunomodulatory Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Mesenchymal Stem-Cell-Derived Exosomes for COVID-19 Treatment. BMB Rep. 53 (8), 400–412. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.8.121

Jomah, S., Asdaq, S. M. B., and Al-Yamani, M. J. (2020). Clinical Efficacy of Antivirals against Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Review. J. Infect. Public Health 13 (9), 1187–1195. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.013

Jorgensen, S. C. J., Kebriaei, R., and Dresser, L. D. (2020). Remdesivir: Review of Pharmacology, Pre-clinical Data, and Emerging Clinical Experience for COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 40 (7), 659–671. doi:10.1002/phar.2429

Kamidani, S., Rostad, C. A., and Anderson, E. J. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Development: a Pediatric Perspective. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 33 (1), 144–151. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000978

Khiali, S., Rezagholizadeh, A., and Entezari-Maleki, T. (2021). A Comprehensive Review on Sarilumab in COVID-19. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 21 (5), 615–626. doi:10.1080/14712598.2021.1847269

Klopfenstein, T., Zayet, S., Lohse, A., Balblanc, J. C., Badie, J., Royer, P. Y., et al. (2020). Tocilizumab Therapy Reduced Intensive Care Unit Admissions And/or Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Med. Mal Infect. 50 (5), 397–400. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2020.05.001

Knox, J. M., and Owens, D. W. (1966). The Chloroquine Mystery. Arch. Dermatol. 94 (2), 205–214. doi:10.1001/archderm.1966.01600260097016

Lai, S. T. (2005). Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24 (9), 583–591. doi:10.1007/s10096-005-0004-z

Lamb, Y. N. (2020). Remdesivir: First Approval. Drugs 80 (13), 1355–1363. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01378-w

Leeman, K. T., Pessina, P., Lee, J. H., and Kim, C. F. (2019). Mesenchymal Stem Cells Increase Alveolar Differentiation in Lung Progenitor Organoid Cultures. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 6479. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42819-1

Leneva, I. A., Russell, R. J., Boriskin, Y. S., and Hay, A. J. (2009). Characteristics of Arbidol-Resistant Mutants of Influenza Virus: Implications for the Mechanism of Anti-influenza Action of Arbidol. Antivir. Res 81 (2), 132–140. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.10.009

Leng, Z., Zhu, R., Hou, W., Feng, Y., Yang, Y., Han, Q., et al. (2020). Transplantation of ACE2(-) Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improves the Outcome of Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Aging Dis. 11 (2), 216–228. doi:10.14336/ad.2020.0228

Li, H., Yang, L., Liu, F. F., Ma, X. N., He, P. L., Tang, W., et al. (2020a). Overview of Therapeutic Drug Research for COVID-19 in China. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 41 (9), 1133–1140. doi:10.1038/s41401-020-0438-y

Li, L., Zhang, W., Hu, Y., Tong, X., Zheng, S., Yang, J., et al. (2020b). Effect of Convalescent Plasma Therapy on Time to Clinical Improvement in Patients with Severe and Life-Threatening COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 324 (5), 460–470. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10044

Li, Q., Ding, X., Xia, G., Chen, H. G., Chen, F., Geng, Z., et al. (2020c). Eosinopenia and Elevated C-Reactive Protein Facilitate Triage of COVID-19 Patients in Fever Clinic: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. EClinicalMedicine 23, 100375. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100375

Li, Z., Niu, S., Guo, B., Gao, T., Wang, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2020d). Stem Cell Therapy for COVID-19, ARDS and Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cell Prolif 53 (12), e12939. doi:10.1111/cpr.12939

Lian, N., Xie, H., Lin, S., Huang, J., Zhao, J., and Lin, Q. (2020). Umifenovir Treatment Is Not Associated with Improved Outcomes in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: a Retrospective Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26 (7), 917–921. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.026

Lin, F. C., and Young, H. A. (2014). Interferons: Success in Anti-viral Immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 25 (4), 369–376. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.015

Liu, X., Chen, H., Shang, Y., Zhu, H., Chen, G., Chen, Y., et al. (2020). Efficacy of Chloroquine versus Lopinavir/ritonavir in Mild/general COVID-19 Infection: a Prospective, Open-Label, Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Clinical Study. Trials 21 (1), 622. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04478-w

Lopez Bernal, J., Andrews, N., Gower, C., Gallagher, E., Simmons, R., Thelwall, S., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 385 (7), 585–594. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2108891

Luke, T. C., Kilbane, E. M., Jackson, J. L., and Hoffman, S. L. (2006). Meta-analysis: Convalescent Blood Products for Spanish Influenza Pneumonia: a Future H5N1 Treatment. Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (8), 599–609. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00139

Luo, P., Liu, Y., Qiu, L., Liu, X., Liu, D., and Li, J. (2020). Tocilizumab Treatment in COVID-19: A Single center Experience. J. Med. Virol. 92 (7), 814–818. doi:10.1002/jmv.25801

Mair-Jenkins, J., Saavedra-Campos, M., Baillie, J. K., Cleary, P., Khaw, F. M., Lim, W. S., et al. (2015). The Effectiveness of Convalescent Plasma and Hyperimmune Immunoglobulin for the Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Infections of Viral Etiology: a Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 211 (1), 80–90. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu396

Mantlo, E., Bukreyeva, N., Maruyama, J., Paessler, S., and Huang, C. (2020). Antiviral Activities of Type I Interferons to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Antivir. Res 179, 104811. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104811

Meyerowitz, E. A., Vannier, A. G. L., Friesen, M. G. N., Schoenfeld, S., Gelfand, J. A., Callahan, M. V., et al. (2020). Rethinking the Role of Hydroxychloroquine in the Treatment of COVID-19. Faseb j 34 (5), 6027–6037. doi:10.1096/fj.202000919

Mo, P., Xing, Y., Xiao, Y., Deng, L., Zhao, Q., Wang, H., et al. (2020). Clinical Characteristics of Refractory COVID-19 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis.. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa270

Mo, Y., and Fisher, D. (2016). A Review of Treatment Modalities for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 (12), 3340–3350. doi:10.1093/jac/dkw338

Montesarchio, V., Parrela, R., Iommelli, C., Bianco, A., Manzillo, E., Fraganza, F., et al. (2020). Outcomes and Biomarker Analyses Among Patients with COVID-19 Treated with Interleukin 6 (IL-6) Receptor Antagonist Sarilumab at a Single Institution in Italy. J. Immunother. Cancer 8 (2). doi:10.1136/jitc-2020-001089

Mukherjee, M., Sehmi, R., and Nair, P. (2014). Anti-IL5 Therapy for Asthma and beyond. World Allergy Organ. J. 7 (1), 32. doi:10.1186/1939-4551-7-32

Ni, L., Chen, L., Huang, X., Han, C., Xu, J., Zhang, H., et al. (2020a). Combating COVID-19 with Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine in China. Acta Pharm. Sin B 10 (7), 1149–1162. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.009

Ni, L., Zhou, L., Zhou, M., Zhao, J., and Wang, D. W. (2020b). Combination of Western Medicine and Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine in Treating a Family Case of COVID-19. Front. Med. 14 (2), 210–214. doi:10.1007/s11684-020-0757-x

Nojomi, M., Yassin, Z., Keyvani, H., Makiani, M. J., Roham, M., Laali, A., et al. (2020). Effect of Arbidol (Umifenovir) on COVID-19: a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 20 (1), 954. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05698-w

Ong, S. W. X., Chiew, C. J., Ang, L. W., Mak, T. M., Cui, L., Toh, M., et al. (2021). Clinical and Virological Features of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern: a Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.315 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin. Infect. Dis.. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab721

Oren, O., Yang, E. H., Gluckman, T. J., Michos, E. D., Blumenthal, R. S., and Gersh, B. J. (2020). Use of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Implications: Understanding Safety Discrepancies to Improve Interpretation and Design of Clinical Trials. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 13 (6), e008688. doi:10.1161/circep.120.008688

Peng, H., Gong, T., Huang, X., Sun, X., Luo, H., Wang, W., et al. (2020). A Synergistic Role of Convalescent Plasma and Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Severely Ill COVID-19 Patients: a Clinical Case Report. Stem Cel Res. Ther. 11 (1), 291. doi:10.1186/s13287-020-01802-8

Polack, F. P., Thomas, S. J., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., et al. (2020). Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 (27), 2603–2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

Prokunina-Olsson, L., Alphonse, N., Dickenson, R. E., Durbin, J. E., Glenn, J. S., Hartmann, R., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and Emerging Viral Infections: The Case for Interferon Lambda. J. Exp. Med. 217 (5). doi:10.1084/jem.20200653

Pulia, M. S., Wolf, I., Schulz, L. T., Pop-Vicas, A., Schwei, R. J., and Lindenauer, P. K. (2020). COVID-19: An Emerging Threat to Antibiotic Stewardship in the Emergency Department. West. J. Emerg. Med. 21 (5), 1283–1286. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48848

Purwati, Budiono., Rachman, B. E., Miatmoko, A., Lardo, S., ,Purnama, Y. S., Laely, M., et al. (2021). A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Clinical Study Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of a Drug Combination of Lopinavir/Ritonavir-Azithromycin, Lopinavir/Ritonavir-Doxycycline, and Azithromycin-Hydroxychloroquine for Patients Diagnosed with Mild to Moderate COVID-19 Infections. Biochem. Res. Int. 2021, 6685921. doi:10.1155/2021/6685921

Qin, C., Zhou, L., Hu, Z., Zhang, S., Yang, S., Tao, Y., et al. (2020). Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. 71(15), 762–768.doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa248

Rawson, T. M., Moore, L. S. P., Zhu, N., Ranganathan, N., Skolimowska, K., Gilchrist, M., et al. (2020). Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals with Coronavirus: A Rapid Review to Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71 (9), 2459–2468. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa530

Sadeghi, S., Soudi, S., Shafiee, A., and Hashemi, S. M. (2020). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies for COVID-19: Current Status and Mechanism of Action. Life Sci. 262, 118493. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118493

Salama, C., Han, J., Yau, L., Reiss, W. G., Kramer, B., Neidhart, J. D., et al. (2021). Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 384 (1), 20–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2030340

Sanches, P. R. S., Charlie-Silva, I., Braz, H. L. B., Bittar, C., Freitas Calmon, M., Rahal, P., et al. (2021). Recent Advances in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and RBD Mutations Comparison between New Variants Alpha (B.1.1.7, United Kingdom), Beta (B.1.351, South Africa), Gamma (P.1, Brazil) and Delta (B.1.617.2, India). J. Virus. Erad 7 (3), 100054. doi:10.1016/j.jve.2021.100054

Sarkar, C., Mondal, M., Torequl Islam, M., Martorell, M., Docea, A. O., Maroyi, A., et al. (2020). Potential Therapeutic Options for COVID-19: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. 11(1428)572870. doi: doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.572870

Sheppard, M., Laskou, F., Stapleton, P. P., Hadavi, S., and Dasgupta, B. (2017). Tocilizumab (Actemra). Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 13 (9), 1972–1988. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1316909

Shi, H., Hong, Y., Qian, J., Cai, X., and Chen, S. (2017). Xuebijing in the Treatment of Patients with Sepsis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 35 (2), 285–291. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.007

Sieswerda, E., de Boer, M. G. J., Bonten, M. M. J., Boersma, W. G., Jonkers, R. E., Aleva, R. M., et al. (2021). Recommendations for Antibacterial Therapy in Adults with COVID-19 - an Evidence Based Guideline. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27 (1), 61–66. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.041

Simonovich, V. A., Burgos Pratx, L. D., Scibona, P., Beruto, M. V., Vallone, M. G., Vázquez, C., et al. (2021). A Randomized Trial of Convalescent Plasma in Covid-19 Severe Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 384 (7), 619–629. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031304

Soo, Y. O., Cheng, Y., Wong, R., Hui, D. S., Lee, C. K., Tsang, K. K., et al. (2004). Retrospective Comparison of Convalescent Plasma with Continuing High-Dose Methylprednisolone Treatment in SARS Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10 (7), 676–678. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00956.x

Stone, J. H., Frigault, M. J., Serling-Boyd, N. J., Fernandes, A. D., Harvey, L., Foulkes, A. S., et al. (2020). Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 (24), 2333–2344. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028836

Stower, H. (2020). Lopinavir–ritonavir in Severe COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26 (4), 465. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0849-9

Tchesnokov, E. P., Feng, J. Y., Porter, D. P., and Götte, M. (2019). Mechanism of Inhibition of Ebola Virus RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase by Remdesivir. Viruses 11 (4). doi:10.3390/v11040326

Thomas, S. J., Moreira, E. D., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., et al. (2021). Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. N. Engl. J. Med.. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2110345

Tiberghien, P., de Lamballerie, X., Morel, P., Gallian, P., Lacombe, K., and Yazdanpanah, Y. (2020). Collecting and Evaluating Convalescent Plasma for COVID-19 Treatment: Why and How. Vox Sang 115 (6), 488–494. doi:10.1111/vox.12926

Verdugo-Paiva, F., Izcovich, A., Ragusa, M., and Rada, G. (2020). Lopinavir-ritonavir for COVID-19: A Living Systematic Review. Medwave 20 (6), e7967. doi:10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7966

Wang, M., Cao, R., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Liu, J., Xu, M., et al. (2020a). Remdesivir and Chloroquine Effectively Inhibit the Recently Emerged Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) In Vitro. Cell Res 30 (3), 269–271. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Du, G., Du, R., Zhao, J., Jin, Y., et al. (2020b). Remdesivir in Adults with Severe COVID-19: a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicentre Trial. Lancet 395 (10236), 1569–1578. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31022-9

Wang, Y., and Zhu, L.-Q. (2020). Pharmaceutical Care Recommendations for Antiviral Treatments in Children with Coronavirus Disease 2019. World J. Pediatr. : WJP 16 (3), 271–274. doi:10.1007/s12519-020-00353-5

Wei, P-F. (2020a). Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7). Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 133 (9), 1087–1095. doi:10.1097/cm9.0000000000000819

Wei, P-F. (2020b). Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7). Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 133 (9), 1087–1095. doi:10.1097/cm9.0000000000000819

Woelfel, R., Corman, V. M., Guggemos, W., Seilmaier, M., Zange, S., Mueller, M. A., et al. (2020). Clinical Presentation and Virological Assessment of Hospitalized Cases of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in a Travel-Associated Transmission Cluster.

Xu, X., Han, M., Li, T., Sun, W., Wang, D., Fu, B., et al. (2020). Effective Treatment of Severe COVID-19 Patients with Tocilizumab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117 (20), 10970–10975. doi:10.1073/pnas.2005615117

Zanoni, M., Cortesi, M., Zamagni, A., and Tesei, A. (2019). The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Radiation-Induced Lung Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (16). doi:10.3390/ijms20163876

Zhang, C., Wu, Z., Li, J. W., Zhao, H., and Wang, G. Q. (2020). Cytokine Release Syndrome in Severe COVID-19: Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonist Tocilizumab May Be the Key to Reduce Mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55 (5), 105954. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954

Zhao, J.-Y., Yan, J.-Y., and Qu, J.-M. (2020a). Interpretations of “Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7)”. 133(11), 1347–1349. doi: doi:10.1097/cm9.0000000000000866

Zhao, J., Yuan, Q., Wang, H., Liu, W., Liao, X., Su, Y., et al. (2020b2019). Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with Novel Coronavirus. disease 71 (16), 2027–2034. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa344

Zheng, W. J., Yan, Q., Ni, Y. S., Zhan, S. F., Yang, L. L., Zhuang, H. F., et al. (2020). Examining the Effector Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection on COVID-19 Based on Network Pharmacology. BioData Min 13, 17. doi:10.1186/s13040-020-00227-6

Zhou, Q., Chen, V., Shannon, C. P., Wei, X. S., Xiang, X., Wang, X., et al. (2020a). Interferon-α2b Treatment for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 11, 1061. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01061

Zhou, W., Wang, H., Yang, Y., Chen, Z. S., Zou, C., and Zhang, J. (1878). Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases, 5832. (Electronic)).

Zhou, W., Wang, H., Yang, Y., Chen, Z. S., Zou, C., and Zhang, J. (2020b). Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases. Drug Discov. Today 25 (11), 2012–2022. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2020.09.010

Zhu, Z., Lu, Z., Xu, T., Chen, C., Yang, G., Zha, T., et al. (2020). Arbidol Monotherapy Is superior to Lopinavir/ritonavir in Treating COVID-19. J. Infect. 81 (1), e21–e23. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.060

Keywords: corona virus disease 2019, corona virus disease 2019 treatment, severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 variants, antimicrobials, immunotherapy, traditional Chinese medicine

Citation: Zou H, Yang Y, Dai H, Xiong Y, Wang J-, Lin L and Chen Z- (2021) Recent Updates in Experimental Research and Clinical Evaluation on Drugs for COVID-19 Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 12:732403. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.732403

Received: 13 July 2021; Accepted: 13 October 2021;

Published: 22 November 2021.

Edited by:

Stephen Rennard, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Ji-Ye Yin, Central South University, ChinaHongtao Xiao, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, China

Yitao Wang, University of Macau, China

Copyright © 2021 Zou, Yang, Dai, Xiong, Wang, Lin and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhe-Sheng Chen, Y2hlbnpAc3Rqb2hucy5lZHU=; Lusheng Lin, Ym9sdW5pbnN0aXR1dGVAaGN6eWdyb3VwLmNvbQ==

†These authors contribute equally to the work.

Houwen Zou

Houwen Zou Yuqi Yang

Yuqi Yang Huiqiang Dai3

Huiqiang Dai3 Jing-Quan Wang

Jing-Quan Wang Zhe-Sheng Chen

Zhe-Sheng Chen