- 1Sichuan Key Medical Laboratory of New Drug Discovery and Drugability Evaluation, Luzhou Key Laboratory of Activity Screening and Druggability Evaluation for Chinese Materia Medica, Key Laboratory of Medical Electrophysiology of Ministry of Education, School of Pharmacy, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China

- 2Department of Anesthesia, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China

- 3Department of Pharmacy, Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China

Neuroinflammation, an inflammatory response within the central nervous system (CNS), is a main hallmark of common neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), among others. The over-activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines, which induces neuronal death and accelerates neurodegeneration. Therefore, inhibition of microglia over-activation and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation has been a promising strategy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Many drugs have shown promising therapeutic effects on microglia and inflammation. However, the blood–brain barrier (BBB)—a natural barrier preventing brain tissue from contact with harmful plasma components—seriously hinders drug delivery to the microglial cells in CNS. As an emerging useful therapeutic tool in CNS-related diseases, nanoparticles (NPs) have been widely applied in biomedical fields for use in diagnosis, biosensing and drug delivery. Recently, many NPs have been reported to be useful vehicles for anti-inflammatory drugs across the BBB to inhibit the over-activation of microglia and neuroinflammation. Therefore, NPs with good biodegradability and biocompatibility have the potential to be developed as an effective and minimally invasive carrier to help other drugs cross the BBB or as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of neuroinflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases. In this review, we summarized various nanoparticles applied in CNS, and their mechanisms and effects in the modulation of inflammation responses in neurodegenerative diseases, providing insights and suggestions for the use of NPs in the treatment of neuroinflammation-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

Neuroinflammation is characterized by the activation of microglia and astrocytes, as well as the release of cytokines and reactive oxygen species. It may cause synaptic dysfunction, the loss of synapses, and neuron damage. Since neuroinflammation is the common mechanism behind various CNS-related diseases, alleviation and inhibition of neuroinflammation has become a research hotspot over recent years. However, most drugs with anti-inflammatory characteristics cannot cross the blood–brain barrier to the target cells such as microglia and astrocytes. The BBB is formed by the brain capillary wall, glial cells and the barrier between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that is formed by the choroid plexus. The BBB is an essential defense mechanism of the CNS that restricts the transit of toxins or pathogens and selectively allows individual molecules to pass. However, the BBB also significantly hinders drug delivery to the CNS (Zhou et al., 2018; Tosi et al., 2020).

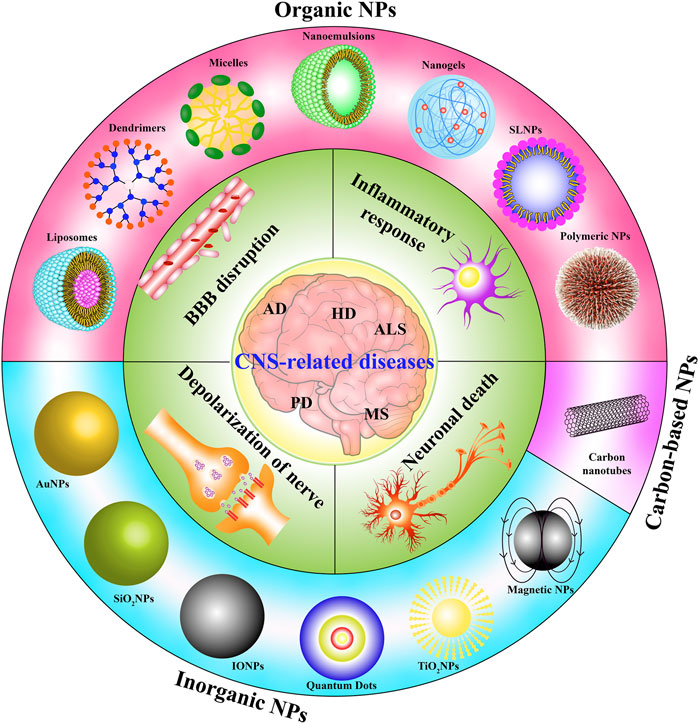

Nanomaterials can make dramatic changes to the treatment of neuroinflammation. Over recent decades, a rising number of nanomaterials have been developed. There is increasing optimism that nanomedicine will continue to develop and could even change the model of the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease (Rodallec et al., 2018; Avasthi et al., 2020). Nanomaterials are made up of engineered materials or devices with the smallest functional organizations in the size range of 1–100 nm (Zielinska et al., 2020). They are mainly classified into two groups: inorganic and organic nanomaterials. Inorganic nanomaterials come in an array of forms, including Au nanoparticles, TiO2 NPs, IONPs and other metal NPs. Organic nanomaterials mainly include lipid NPs (liposomes and solid lipid NPs), nanoemulsions and polymer NPs (polymeric NPs, dendrimers, nanogels, and micelles) (Kumari et al., 2010; Martinez-Lopez et al., 2020).

NPs can encapsulate drugs with relatively high drug loading (Sim et al., 2020), and the surface of NPs can be easily manipulated to achieve drug targeting (Sun et al., 2014). In addition, NPs can control the release of drugs at the site of target cells or tissues, thereby increasing therapeutic efficacy and reducing the side effects of drugs. Drugs that are insoluble or unstable in aqueous phase could be formulated into nano delivery systems, which improves their solubility and extends their pharmacologic effects. Most importantly, NPs systems could provide a variety of choices for the routes of drug administration, including intravenous, nasal, oral, parenteral, intra-ocular, and dermal topical application (Spuch et al., 2012; Carita et al., 2018; He et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2020). In recent years, a number of NPs have been developed as effective and minimally invasive carriers to help other drugs cross the BBB or as the therapeutic agents for the treatment of neuroinflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases (Moura et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019; Tosi et al., 2020).

In this article, we summarize the current knowledge gained from recent advances in nanomaterials, and their key treatment roles in neuroinflammation-related neurodegenerative diseases, which provides more opportunities and prospects for the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases in the future.

Neuroinflammation in CNS-Related Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are the main type of CNS-related diseases and include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington disease (HD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), etc. The pathologies of neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by neuroinflammation, cerebral protein aggregates, synaptic abnormalities, and progressive loss of neurons (Dugger and Dickson, 2017; Vaquer-Alicea and Diamond, 2019). Gradual cognitive and memory impairments and disorder in movements are common clinical symptoms (Katsnelson et al., 2016; Stephenson et al., 2018).

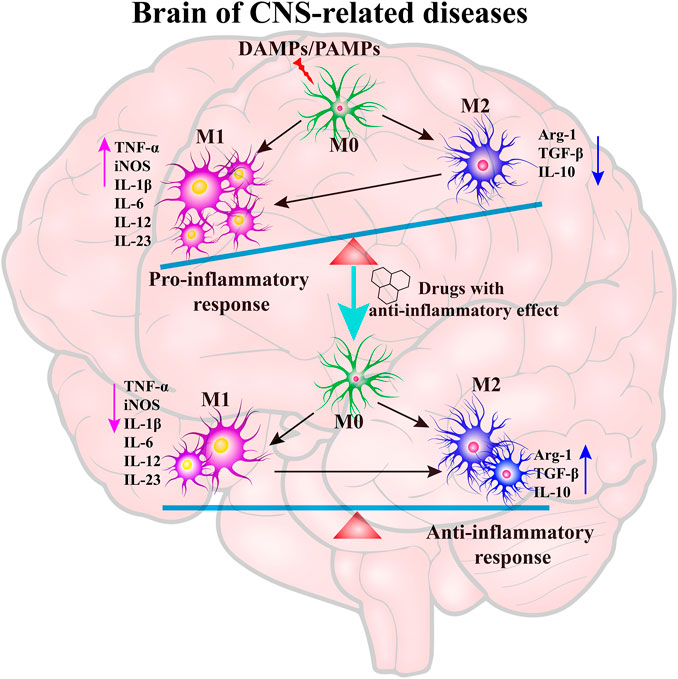

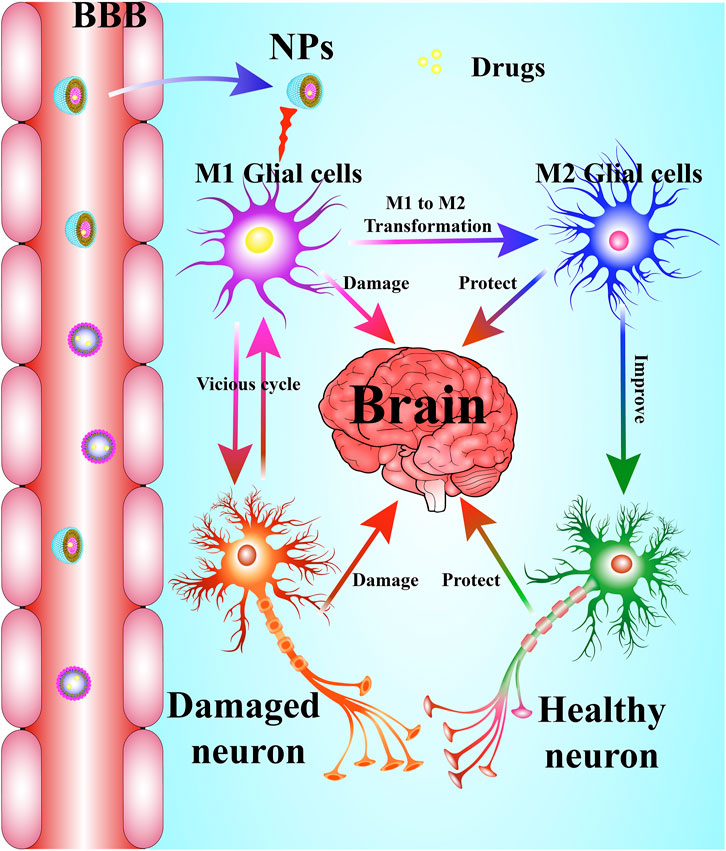

Neuroinflammation generally refers to an inflammatory response within the CNS or activation of the neuroimmune cells, microglia and astrocytes into the state of pro-inflammatory response (Schain and Kreisl, 2017). Emerging evidence indicates that the resting microglia (M0) is over-activated by various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) including particulates, viruses, bacteria, fungi, toxins, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), crystals, silica, and misfolded protein aggregations (Aβ, Tau, α-synuclein, etc.) in neurodegenerative diseases (Agostinho et al., 2010; Allaman et al., 2011; Alcendor et al., 2012; Niranjan, 2014). The transient receptor potential melastatin-related 2 (TRPM2) is a calcium-permeable channel induced by oxidative stress (Alawieyah Syed Mortadza et al., 2018), ultimately causing activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (Koenigsknecht and Landreth, 2004). Microglia and astrocytes are the primary constituents of a dedicated neuroimmune system in CNS. The moderative activation of microglia (M2) can protect brain by defending against harmful materials by releasing many anti-inflammatory cytokines, including Arg-1, TGF-β, and IL-10. However, amplified, exaggerated, or chronically activated microglia (M1) lead to robust pathological changes and neurobehavioral complications, such as depression and cognitive deficits (Norden and Godbout, 2013). The inflammation process is indicated by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), as well as many chemokines, such as C-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CCL1), CCL5, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), and small-molecule messengers, including prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO), and reactive oxygen species (DiSabato et al., 2016). After treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs, the M1-type microglia are converted into M2-type microglia, which is indicated by the decrease of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The key role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. The resting microglia (M0) are over-activated by PAMPs/DAMPs into a pro-inflammatory state (M1), which leads to the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The treatment of anti-inflammatory drugs can inhibit the over-activation of microglia and promote the microglia into an anti-inflammatory state to maintain the balance of M1/M2 type microglia.

Many researchers have recently reported findings about the mechanism of neuroinflammation associated with neurodegenerative disorders (Schain and Kreisl, 2017). Earlier studies identified amyloid β (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau as playing essential roles in the progress of AD (Eftekharzadeh et al., 2018; Nakamura et al., 2018). Many previous studies found that Aβ oligomers are the most toxic forms among all Aβ species, and the smaller oligomers of Aβ have been proved to be stronger stimuli to activate the microglial cells (Yang et al., 2017). The aggregated tau has been considered to induce microglial changes by activating the NLRP3–ASC axis (Ising et al., 2019; Stancu et al., 2019). Numerous studies have shown that Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau induce pro-inflammatory conditions in vitro and vivo (Maezawa et al., 2011; Morales et al., 2013; Asai et al., 2014; Marlatt et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2019). Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that soluble α-synuclein aggregates play a significant role in PD and most of them were found within the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) region of the midbrain (Winner et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2013). Recently, activated microglia were found surrounding Lewy bodies, suggesting that neuroinflammation is a common response to α-synuclein aggregates (Streit and Xue, 2016). In addition, widespread microglial activation was visible by positron emission tomography (PET) in the brain of living ALS patients and SOD1G93A mice, indicating that there is an association between neuroinflammation and ALS (Turner et al., 2004; Corcia et al., 2012; Gargiulo et al., 2016). Therefore, microglia over-activation and the resulting neuroinflammation have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, while the inhibition of neuroinflammation has been considered a promising strategy for the treatment of neuroinflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases.

The Effect of NPs in CNS-Related Diseases

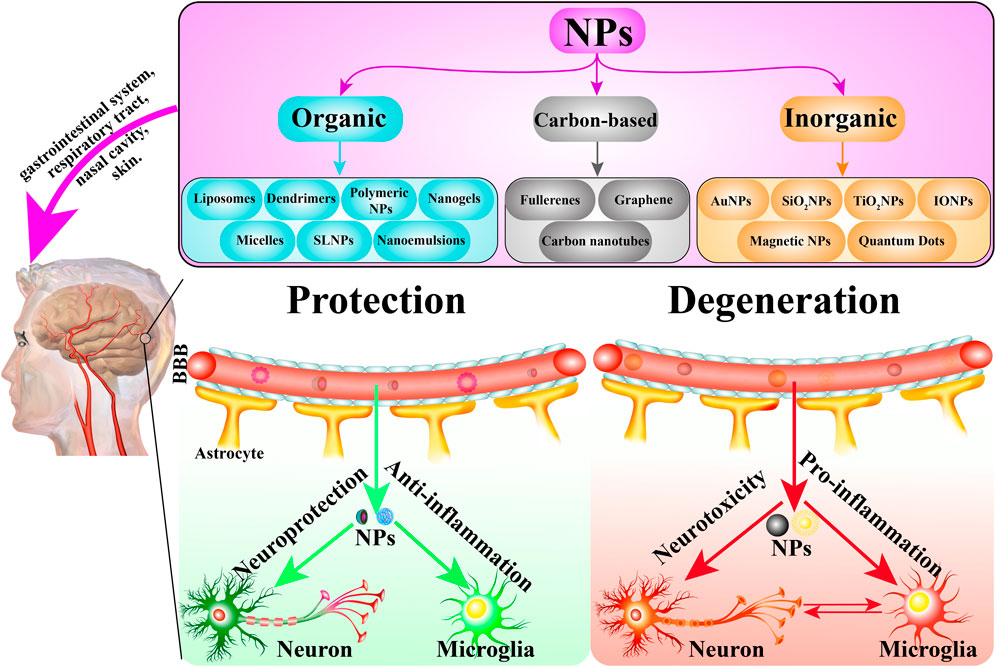

The traditional definition of nanoparticle size is 1–100 nm. Indeed, while most NPs are under 100 nm, the diameter of some composite or drug-loaded NPs are over 100 nm (Suk et al., 2016; Tosi et al., 2020). Furthermore, the generally accepted classification of nanoparticles is based on their organic, inorganic, and carbon-based nature (Figure 2). Particle size is the basic attribute of NPs, which determines the biological fate, toxicity, distribution, and targeting ability of NPs to a certain extent. Generally, smaller NPs are prone to aggregate during dispersion, storage, and transport, and exhibit faster drug release due to their larger surface-to-volume ratio. On the contrary, larger NPs lead to faster polymer degradation and slower drug release (Gupta et al., 2019; Zahin et al., 2020). The shape of NPs contributes to biological functions such as drug delivery, half-life period, endothelial intake, and targeting ability (Petros and DeSimone, 2010; Yoo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015). NPs have varied shapes including rod, spherical, triangular, cube, hexagonal, fivefold star shape and monodisperse cubic dendrites, among others (Lacroix et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2014). Surface charge and hydrophobicity are surface properties of NPs, which may influence their biodistribution, circulation time, and toxicity (Arvizo et al., 2011). Positively charged NPs show better efficacy of imaging, gene transfer, and drug delivery, but they are reported to possess higher cytotoxicity. Hydrophobicity is another important surface property, which plays an important role in plasma protein binding and clearance via the reticuloendothelial system (RES) (Frohlich, 2012; Nam et al., 2013).

FIGURE 2. The classification of NPs and the role of NPs in CNS-related diseases. NPs are mainly classified into three groups: organic, carbon-based, and inorganic NPs. In general, these NPs are administrated via the gastrointestinal system, respiratory tract, nasal cavity, and skin, etc. They cross the BBB into the target brain cells including neurons, microglia and astrocyte to exert protective and degenerative effects.

To date, NPs have been widely used in CNS-related diseases including neurodegenerative disease, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and cerebral tumor. As drug carriers or as therapeutic drugs by themselves, NPs show potential for neuroprotective effects by oxidation resistance, anti-apoptosis, and nerve regeneration (Figure 2). The initial focus of neuroprotective treatment is the neurons, which are considered the most vulnerable cells to hypoxia and excitotoxicity. However, in recent years, concerns have been extended to astrocytes, pericytes, endothelial cells, and other neural cells, targeting antioxidant enzymes, antiapoptotic pathways, and downstream cytokines (Moretti et al., 2015; Chamorro et al., 2021). Polysorbate 80 (PS80) reduced the secondary spread of neuroinflammation and injury in traumatic brain injuries (TBI) by preventing the spread of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Yoo et al., 2017a). Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles, which encapsulated Lexiscan and Nogo-66, improved stroke survival, suggesting the potential therapeutic effect for stroke (Han et al., 2016). Numerous researchers have demonstrated that organic and inorganic NPs might be helpful in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, especially AD and PD. The possible mechanisms include the delivery of a corresponding drug, siRNA transfection, interference with Aβ fibril formation, down-regulating proinflammatory factors, etc. (Tiwari et al., 2014; Karthivashan et al., 2018; Baskin et al., 2020).

NPs can participate in the treatment of neuroinflammation as carriers for therapeutic drugs including curcumin, okadaic acid, quercetin, anthocyanin, and levodopa. With the assistance of NPs, the drugs can cross the BBB to target cells more easily, thereby inhibiting inflammatory pathways and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Besides, magnetic NPs, such as IONPs, have been applied in diagnosis and imaging. Moreover, nanoparticles themselves also have therapeutic effects in neuroinflammation. For example, AuNPs could induce microglia polarization toward the M2 phenotype (Xiao et al., 2020), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can integrate with neurons and enhance neuronal functions (Matsumoto et al., 2007), and rhubaric acid hydrogel inhibits TLRs signaling pathways (Zheng et al., 2019).

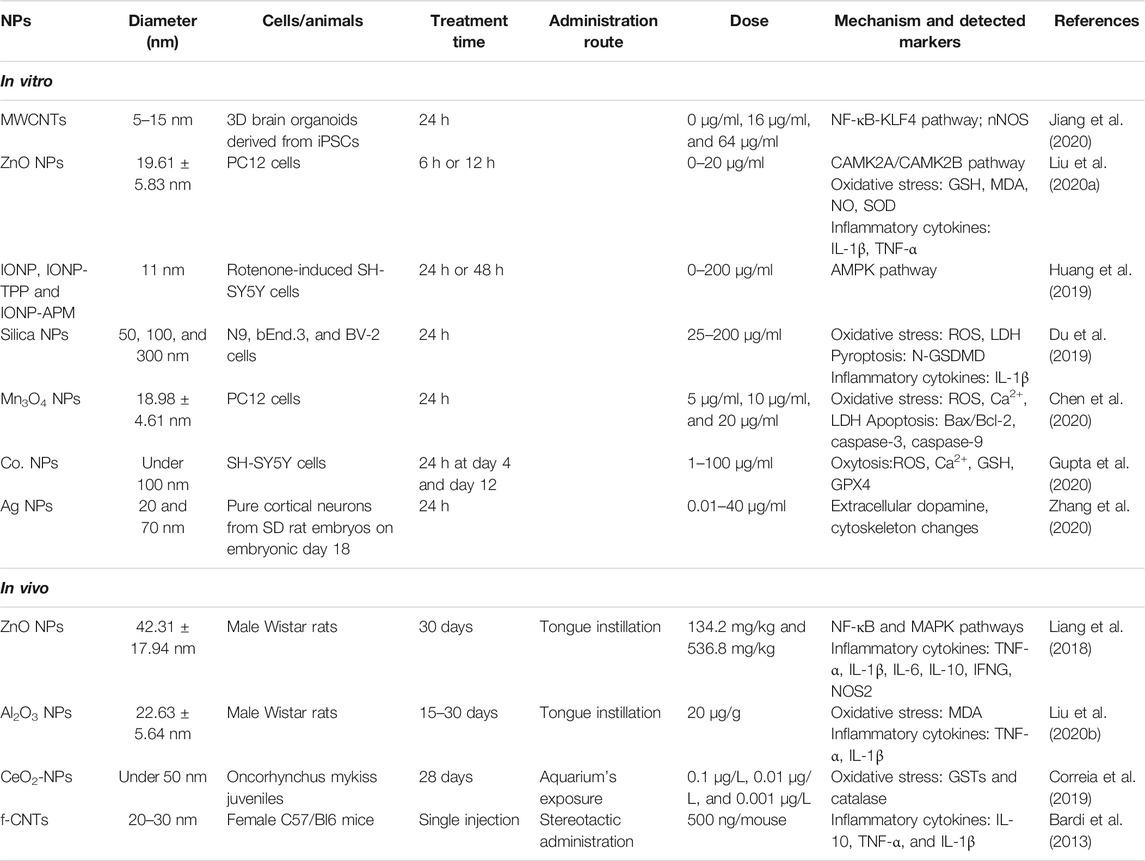

Although NPs exhibit potent neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects, many NPs have been reported to exhibit neurotoxicity and pro-inflammatory responses in some cells and animals with CNS-related diseases (Table 1; Figure 2). For example, copper NPs can cause BBB dysfunction, swelling of astrocytes, and neuronal degeneration once introduced into the bloodstream (Sharma, 2009; Sharma et al., 2009).

Organic NPs

Lipid-based NPs

Liposomes

Liposomes are vesicular drug-delivery systems containing an aqueous inner core enclosed in multi-lamellar phospholipid bilayers. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs can be loaded in the phospholipid bilayers and aqueous core, respectively (Agrawal et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018).

Liposomes have the characteristics of nanoscale, ideal biocompatibility and relative stability. Due to the structural similarity of phospholipid bilayers to the cell membrane, liposomes can be absorbed by vascular endothelial cells more easily, which makes them promising drug-delivery systems to increase the BBB crossing of therapeutics in CNS diseases associated with neuroinflammation (Li et al., 2017; Patel and Patel, 2017; Li et al., 2019a). However, they can easily be degraded and scavenged by macrophages, and their binding to plasma proteins causes non-specific targeting to other tissues and low targeting to the nervous system. To overcome these drawbacks, long-circulation liposomes, specific active targeting liposomes, and other new types of liposomes have been developed over recent years (Gabizon et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019a).

Dopamine-PEGylated immunoliposomes (DA-PILs)—liposomes modified with polyethylene glycol and conjugated with antibodies—were developed as vehicles for dopamine in PD treatment. In a rat model of PD, the uptake of DA-PIL in the brains increased about 8-fold and 3-fold compared with that of DA and encapsulated DA-PEGylated liposomes (DA-PL), respectively (Kang et al., 2016). The physicochemical properties of liposomes can be modified by altering the phospholipids themselves or their ratio. Since dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) was the most pH-stable liposome found, with a sustained drug release at physiological pH (Yaroslavov et al., 2015), DPPC was selected as the carrier of curcumin to explore the therapeutic effect in human fetal astrocyte cell line SVGA model of neuroinflammation and reactive astrogliosis. Compared with free curcumin, LipoCur showed a significant downregulation of glial cell proliferation genes and a lower level of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1β, TGF-β, and TNF-α (Schmitt et al., 2020). In addition, Cyclosporine A (CsA) in liposomal formulation (Lipo-CsA) inhibits the inflammation response, including myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and TNF-α levels, in the model of ischemia reperfusion injury (I/R) cerebral injuries (Partoazar et al., 2017). Therefore, liposomes serving as drug-delivery systems increase the BBB penetration of drugs to improve the anti-inflammatory effect.

Solid Lipid NPs

Manufactured from synthetic or natural lipids, solid lipid NPs (SLNs) have a lipidic core, which enables them to stay in solid state at room and body temperatures (Cupaioli et al., 2014). SLNs are less toxic than cationic liposomes and are generally recognized as safe in humans. Besides, they have been proved to be physiologically tolerated and have higher drug delivery efficiency compared to other types of lipid-based NPs (Banerjee and Pillai, 2019; Raza et al., 2019).

In LPS-induced BV-2 microglial cells, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLCN) dose-dependently inhibited the levels of nitric oxide (NO) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and this was more effective than curcumin alone (Ganesan et al., 2019). Similarly, SLCN provides a superior effect in anti-Aβ, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective outcomes than traditional curcumin in one-year-old 5xFAD AD mouse (Maiti et al., 2018). In addition, sesamol-loaded SLNs were developed and found to significantly alleviate the oxidative stress in intracerebroventricular (ICV)-streptozotocin (STZ)-induced male Wistar rats, suggesting they provide a promising strategy to mitigate neuroinflammation and memory deficits (Sachdeva et al., 2015). SLNs are clearly useful delivery systems to alleviate neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction.

Nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions (NEs) are a colloidal dispersion consisting of two immiscible liquids stabilized by surfactants. A typical NE usually contains water, oil, and an emulsifier at appropriate ratios. NEs show some excellent properties including good biocompatibility, kinetical stability, cell transport by paracellular and transcellular pathways, and prevention of hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation of residues (Nirale et al., 2020). NEs can be administrated through nasal and ocular delivery in addition to the oral and intravenous administrations (Karami et al., 2019a; Karami et al., 2019b; Nirale et al., 2020).

Chitosan-coated rosmarinic acid nanoemulsions (RA CNE) have been shown to offer protection by inhibiting cellular death and repairing the astrocyte redox state in LPS-induced neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in astrocyte cells (Fachel et al., 2020a). Based on these in vitro results, researchers further illustrated the neuroprotective effects of RA CNE on the alleviation of neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and memory deficit in Wistar rats (Fachel et al., 2020b). In LPS-induced rat neuroinflammation models, the brain uptake of siRNA delivered by cationic nanoemulsions was almost five times higher than non-encapsulated siRNA. More importantly, siRNA nanoemulsions significantly reduced the level of TNF-α, a signaling molecule which aggravates inflammation. Therefore, nanoemulsions encapsulated with TNF-α siRNA were suggested to be potential candidates in the treatment of neuroinflammation (Yadav et al., 2016). Ropinirole, a dopamine agonist as combination therapy with levodopa, is widely used in the treatment of PD. However, its efficiency was limited by its low bioavailability and short half-life. After modification, the transdermal delivery of ropinirole NE gel exhibited better drug absorption and less irritation and toxicity for the skin compared to ropinirole alone (Azeem et al., 2012).

Polymer-Based NPs

Polymeric NPs

Polymeric NPs consist of amphiphilic block copolymers with varying hydrophobicities. They can be categorized into two groups: natural and synthetic polymeric NPs. Synthetic polymeric NPs can be manufactured via nanoprecipitation or the double emulsion method. Owning to the core–shell structure, polymeric NPs are able to encapsulate slow-release hydrophobic drugs and prolong circulation time. The surface of polymeric NPs can be decorated with ligands for targeted drug delivery. Therefore, polymeric NPs are considered drug carriers with high biological activity and bioavailability and have a high therapeutic index (Chen et al., 2015; Zielinska et al., 2020).

Natural polymeric macromolecules mainly include chitosan, alginates, dextrane, gelatin, collagen and their derivatives. Chitosan often derives from exoskeletons of crustaceans and cell walls of fungi and is a cationic polymer. As the second most abundant natural polysaccharide, chitosan, together with chitosan oligosaccharide and its derivatives, have been widely applied as the material of nano-carriers for the treatment of neuroinflammation. Besides, chitosan have neuroprotective effects in AD by inhibiting Aβ, acetylcholinesterase (AchE), oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation (Ouyang et al., 2017). Chitosan-coated synergistically engineered nanoemulsion of Ropinirole and nigella oil was suggested as a potential therapeutic strategy for PD by downregulating the NF-κB signaling pathway and inhibiting lipid peroxidation (Nehal et al., 2021). Alginate is an acidic polysaccharide from various marine brown algae. Alginate-derived oligosaccharide (AdO) was reported to significantly reduce the level of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), as well as the secretion of other proinflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, AdO significantly attenuated the overexpression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and NF-κB induced by LPS in BV2 cells (Zhou et al., 2015). In addition, alginate micro-encapsulation of mesenchymal stromal cells could modulate the neuroinflammatory response by decreasing the production of PGE2 in LPS induced astrocytes and microglia (Stucky et al., 2015; Stucky et al., 2017).

Synthetic polymers include polyesters and their copolymers, polyacrylates and polycaprolactones. Compared with natural molecules, their synthesis conditions can be controlled to regulate chain length, composition, and degradation to perform multiple functions (Colmenares and Kuna, 2017). In addition, synthetic polymers have been proved to possess relatively low toxicity profiles. Polymeric surface modification has been used to minimize the uptake by the reticuloendothelial system, thus increasing blood circulation half-life, which is a promising strategy to improve controlled drug release for long periods (Modi et al., 2010). Currently, poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), which is approved by United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human application, is the most commonly studied polymer with good biocompatibility and biodegradability (Pavot et al., 2014; Younas et al., 2019). A novel brain-target nanoparticle, poly (lactide-co-glycolide)-block-poly (ethylene glycol) (PLGA-PEG) conjugated with B6 peptide and loaded with curcumin (PLGA-PEG-B6/Cur) was designed (Fan et al., 2018). Compared with native Cur, PLGA-PEG-B6/Cur significantly improved the spatial learning and memory ability of APP/PS1 mice by increasing the average half-life, decreasing metabolism, and maintaining the release of Cur, which showed potential for use in the treatment of AD. In addition, PEGylated-PLGA nanoparticles of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) were developed to improve drug stability and increase the brain delivery in the treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. Indeed, immunohistochemistry and neurotoxicity studies confirmed reduced neuronal death and neuroinflammation (Cano et al., 2018). NPs also showed a better effect on the reduction of the frequency and intensity of epileptic episodes than EGCG. In some other studies, PLGA NPs were synthesized to transfer superoxide dismutase (SOD) in cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury (IR) injury mouse models, and the results showed that PLGA NPs were effective in reducing apoptosis, inflammatory markers (TNF-a, IL-1β, and TGF-β), and infarct volume (Yun et al., 2013). In addition, Foxp3 plasmid-encapsulated PLGA NPs was found to significantly reduce microglial activity and decrease the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, I L-1β, IL-6, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Shin et al., 2019). The cl PGP-PEG-DGL/CAT-Aco system (cross-linked dendrigraft poly-l-lysine nanoparticles modified with Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP)peptide and catalase (CAT), a neuroprotective enzyme) was developed (Zhang et al., 2017). In this system, leukocytes serve as ‘Trojan horses’ and freight the CAT penetrate across the BBB more effectively. In the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, the cl PGP-PEG-DGL/CAT-Aco system significantly enhanced the delivery of catalase to ischemic subregions and reduced the volume of brain infarct. Therefore, the studies reviewed suggest the effectiveness, drug protection, and long cycle life of synthetic polymers.

Dendrimers

Dendrimers consist of a group of highly ordered macromolecules synthesized through repetitive chemical reactions from a core with a structure (Araujo et al., 2018; Dias et al., 2020). They were first discovered in 1985 and have been extensively studied. Through covalent bonds and ion interactions or adsorption, dendrimers deliver drugs, genes and proteins with molecules loaded inside or bound to their surface to bring them across the BBB (Chauhan, 2018; Sherje et al., 2018).

The advantages of dendrimers include the following: 1) controlled biodistribution and pharmacokinetics; 2) high structural and chemical homogeneity, which facilitates pharmacokinetic reproducibility; 3) the ability to associate with various compounds and/or ligands, improving their solubility and specificity; 4) and numerous surface groups of dendrimers contribute to multifunctionality and/or high drug loads (Lyu et al., 2020; Sandoval-Yanez and Castro Rodriguez, 2020; Yousefi et al., 2020). However, their higher cost of production is a limitation compared to linear polymers. Moreover, the toxicity of dendrimers was reported by some studies. A temporary increase of liver aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels was observed in a macaque model accepting anionic AzaBisPhosphonate groups (ABP dendrimer). Injections of G0-G3 amine-terminated PAMAM dendrimers in a mouse air pouch model caused a significant increase in leukocyte infiltration (Durocher and Girard, 2016).

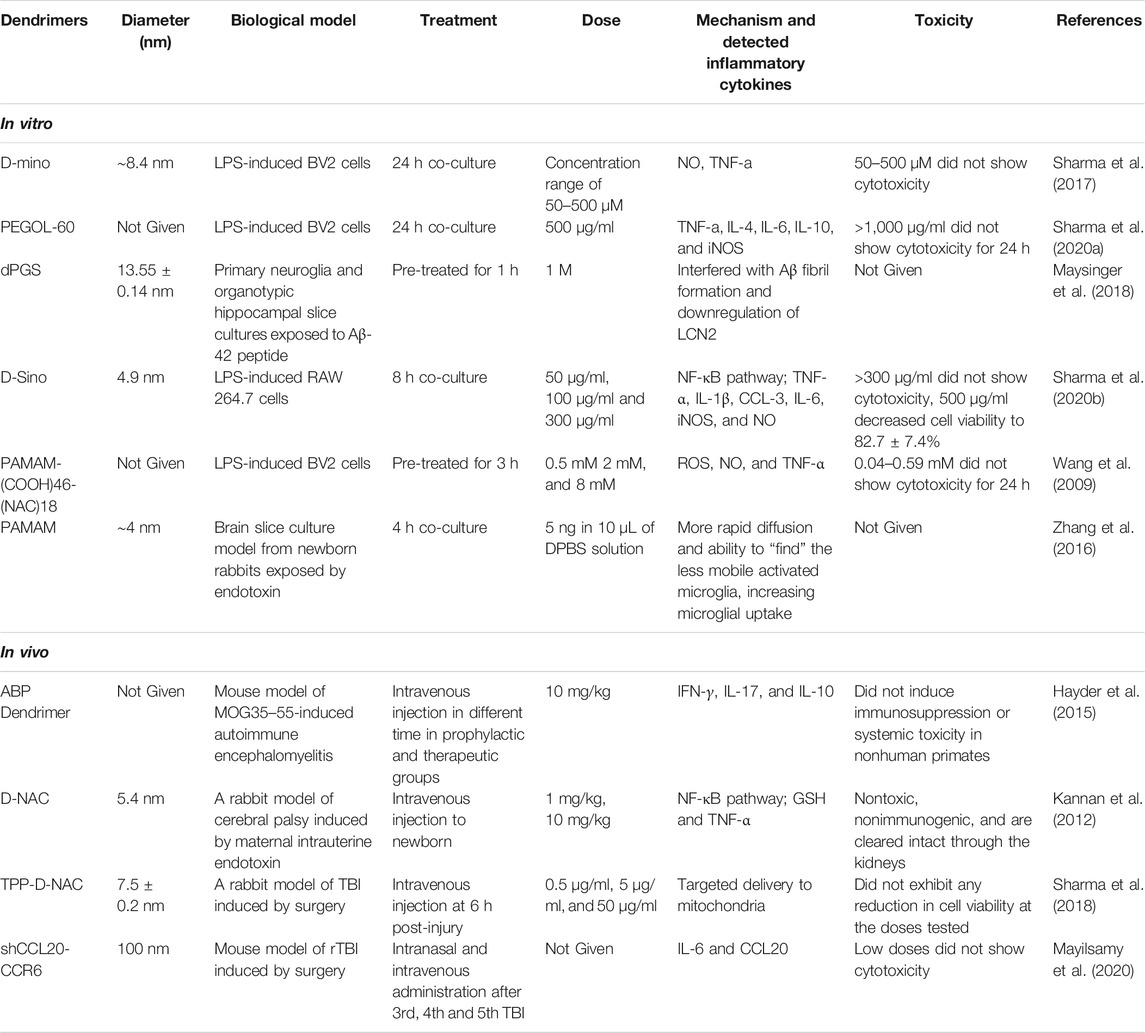

However, other researchers found that dendrimers were beneficial to human health. Dendrimer-based N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) could be a therapy for neuroinflammation and cerebral palsy (CP) using a CP rabbit model induced by maternal intrauterine endotoxin by increasing the concentration of GSH in astrocytes and inhibiting neuroinflammation as indicated in GSH, 4-HNE, NT-3, 8-OHG, NF-kB, and TNF-a. Further study found that dendrimers are nontoxic, nonimmunogenic, and can be cleared completely through the kidneys (Kannan et al., 2012). Dendritic polyglycerol sulfates (dPGS) have been shown to be multivalent inhibitors of inflammation (Dernedde et al., 2010) and potent complement inhibitors (Silberreis et al., 2019). It was reported that dPGS interfered with Aβ fibril formation and reduced the production of the neuroinflammagen lipocalin-2 (LCN2) in astrocytes through its direct binding to Aβ42 and interaction with Aβ42. In addition, dPGS could normalize the impaired neuroglia cell and prevent the loss of dendritic spines at excitatory synapses in the hippocampus (Maysinger et al., 2018). Therefore, dPGS might be helpful in the treatment of neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, fourth-generation poly amidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers were synthesized by Li et al. (Li et al., 2012). Sino, a potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant drug was combined with hydroxyl terminated generation-4 PAMAM dendrimer by Sharma et al. (2020b). D-Sino was demonstrated to be a potential therapy for attenuating inflammation in TBI at early stage through inhibiting the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL-3, and IL-6, reducing the level of iNOS and NO, and inhibiting NF-κB activation and its nuclear translocation (Sharma et al., 2020b). Researchers also demonstrated that NAC, based on G4-OH PAMAM dendrimers (D-NAC), could increase intracellular GSH levels and prevent extracellular glutamate release and excitotoxicity in microglia and astrocytes, compared with NAC alone (Nance et al., 2017). Therefore, dendrimers, especially PAMAM, are considered a promising drug delivery system for CNS disease associated with neuroinflammation (Table 2; Figure 3).

TABLE 2. Dendrimers for the inhibition of neuroinflammation and their mechanisms within in vitro and in vivo models.

FIGURE 3. NPs serve as a drug delivery system in neuroinflammation-mediated CNS-related diseases. NPs delivery systems help drugs cross the BBB to inhibit over-activated microglia and its resultant neuroinflammatory response, which promotes the transformation of M1-type microglia into M2-type microglia and improves neuronal viability.

Nanogels Solid Lipid NPs

Aqueous-based liquids can be used as supporting media for polymer gels by physical/chemical intercrossing. Nanogels are three-dimensional hydrogel particles composed of hydrophilic or amphiphilic polymer chains. Based on their structure, nanogels can be divided into four groups: hollow, multi-layered, core cross-linked, and hairy nanogels (Soni et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Hajebi et al., 2019). Since nanogels have many advantages over other delivery materials including adjustable size, swelling, biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, ease of preparation, and stimulus responsiveness. Thus, they offer a promising prospect for drug, gene, or imaging agents transport. It was found that activin B-loaded hydrogels (ABLH) could provide lasting release of activin B for over five weeks in an MPTP-induced male C57BL/6J mice model of PD. Additionally, ABLH significantly increased the density of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) positive nerve fibers and induced a noticeable reduction in neuroinflammatory responses, suggesting that ABLH may be a promising drug candidate for PD (Li et al., 2016). Self-assembling hydrogels possess superior characteristics without any structural modifications, as they are self-releasing, stable, soluble, injectable, stimuli responsive, and almost nontoxic. As a result, they are considered optimal therapeutic materials. Zheng et al. (2019) reported that rhein hydrogels—natural herbal drug hydrogels—enter the LPS-induced BV2 microglia and bind to TLR4 easily to inhibit the nuclear translocation of p65 in the NF-κB signaling pathway, thus reducing neuroinflammation with a sustained effect. Besides, it showed minimal cytotoxicity compared to rhein alone (Zheng et al., 2019). Therefore, nanogels have been developed in new ways, and their potential as a treatment for neuroinflammation needs to be explored further.

Polymeric Micelles

Micelles are colloidally made from amphiphilic block copolymers which aggregate in aqueous solutions and consist of a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic surface (Zhang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017). The mechanism of acute ischemic stroke includes oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and cerebrovascular injury, which might lead to neuronal death. Lu et al. (2019) encapsulated rapamycin in self-assembled micelles consisting of ROS-responsive and fibrin-binding polymers. They found that the microthrombus-targeting micelles eliminated ROS generation and contributed to micelle polarized M2 microglia repair, thereby enhancing neuroprotection and blood perfusion.

Inorganic NPs

AuNPs

AuNPs are a type of inorganic nanoparticle which play an important role in pharmacology, sensing (Uehara, 2010), and bio-imaging (Kim et al., 2009; Duncan et al., 2010; Hutter and Maysinger, 2011; Yoo et al., 2017b) with a suitable size and shape. Although AuNPs are widely considered to be safe and have low phototoxicity (Li et al., 2019b), they still induce gold toxicity and the hepatobiliary elimination of AuNPs has attracted considerable attention (Bahamonde et al., 2018; Park et al., 2019). In neurodegenerative disease, AuNPs are reported to suppress the pro-inflammatory responses in a microglial cell line by inducing polarization toward the M2 phenotype, which is beneficial for CNS repair and regeneration (Xiao et al., 2020).

Emerging evidence showed that AuNPs regulated inflammatory signaling by inhibiting the TNF-α pathway and downregulating the NF-κB signaling pathway (Xiao et al., 2020). The mice injected intracerebroventricularly with streptozotocin (STZ) exhibited sporadic AD symptoms, activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, and increased secretion of IL-1β, while the treatment of AuNPs significantly inhibited the pro-inflammatory response via the NF-κB pathway (Muller et al., 2017).

Furthermore, there are many AuNPs-modified drugs which are more effective as anti-inflammatories than AuNPs or drugs alone. IL-4 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that can decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) and ameliorate the chronic inflammatory process (Casella et al., 2016). Compared to the AuNPs treatment alone group, the combination of okadaic acid and AuNPs significantly increased the level of IL-4 both in the hippocampus and cortex regions, suggesting that AuNPs together with okadaic acid exert a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect (Dos Santos Tramontin et al., 2020). In BV-2 cells, gold-quercetin NPs were demonstrated to have stronger anti-inflammatory effects than quercetin or AuNPs alone by decreasing the expression of inflammation-producing enzymes (COX-2 and iNOS) at both the transcriptional and translational levels (Ozdal et al., 2019). Ephedra sinica Stapf-AuNPs reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and ROS production by downregulating the IKK-α/β, NF-κB, JAK/STA T, ERK-1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK signaling pathways, upregulating the expression of HO-1 and NQO1, and by activating Nrf2 and AMPK in BV-2 microglial cells. In addition, the combination of AuNPs and n-acetylcysteine (NAC) significantly attenuated sepsis-induced neuroinflammation by decreasing myeloperoxidase activity and proinflammatory cytokines production, as compared with NAC or AuNPs treatment alone (Petronilho et al., 2020). Anthocyanins administered either alone or loaded with PEG-AuNPs reduced Aβ1-42-induced neuroinflammation and inhibited neuronal apoptosis by constraining the p-JNK/NF-κB/p-GSK3β pathway in BV2 cells and Aβ1-42-injected mice; anthocyanins loaded with PEG-AuNPs exhibited a stronger effect than anthocyanins alone (Kim et al., 2017). Moreover, l-DOPA-AuNF, a multi-branched nanoflower-like gold nanoparticles based on l-DOPA, efficiently improved the penetration of l-DOPA across the BBB (Gonzalez-Carter et al., 2019), which provides evidence for the further development of drugs with potent anti-inflammatory effects that cannot cross the BBB. Therefore, AuNPs, and especially AuNP-modified drugs, exhibit powerful anti-inflammatory effects against neurodegenerative disease (Table 3).

Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (IONPs)

IONPs belong to the ferrimagnetic class of magnetic materials, which are widely used in biomedical and bioengineering applications (Figuerola et al., 2010). Magnetic NPs have shown great promise in many fields (Dinali et al., 2017). Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONPs) are applied in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic particle imaging (MPI) and targeted drug delivery (Xu et al., 2011; Du et al., 2013; Khandhar et al., 2013; Jin et al., 2014; Schleich et al., 2015). SPIONPs have been extensively used for diagnosis to visualize tumors and metastases in liver (Choi et al., 2006), and for angiography as a blood pool agent to visualize inflammatory lesions such as atherosclerotic plaques (Neuwelt et al., 2015). In addition, IONPs also suppress the production of IL-1β in LPS-stimulated microglia (Wu et al., 2013). Therefore, IONPs are mainly employed to diagnose and suppress inflammatory lesions in neurodegenerative diseases.

Silica Nanoparticles (SiO2NPs)

SiO2NPs, one of the most broadly exploited nanomaterials, have been utilized in a variety of industries (Vance et al., 2015). SiO2 NPs have been widely applied in the pharmaceutical industry to encapsulate water-insoluble therapeutic agents to improve their dispersal in aqueous media (Durfee et al., 2016; Echazu et al., 2016). Small-sized SiO2 has potential applications in the delivery of diagnostic and therapeutic agents across the BBB and brain imaging (Liu et al., 2014). Importantly, SiO2 exposure does not affect cell viability on different neural cells and does not induce neuroinflammation (Murali et al., 2015; Ducray et al., 2017). However, long-term NPs exposure leads to mood dysfunction and cognitive impairment and alters the synapse by activating MAPKs (You et al., 2018). Therefore, SiO2NPs can pass through the BBB, and their potential in the treatment of neuroinflammation needs to be explored.

Nanocarbon Lipid-Based NPs

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

CNTs are tubular structures made of a layer of graphene rolled into a cylinder (Eatemadi et al., 2014). These NPs are classified as single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) or multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) according to the number of wall sheets in their structure (Salvador-Morales et al., 2006). The potential advantage of CNTs is their capacity to integrate with neurons and enhance neuronal functions as substrates for neuronal growth in different neuron cells (Hu et al., 2004; Matsumoto et al., 2007; Cellot et al., 2009).

After modification by polymers, CNTs can offer additional sites for conjugation of other molecules (Wong et al., 2013). There are some contradictions concerning the effect of CNTs on the nervous system. It was reported that SWCNTs exert an anti-inflammatory effect and protect neurons from ischemic damage in a rat stroke model (Nunes et al., 2012). The release of dexamethasone by polypyrrole/CNTs led to the attenuation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced microglia activation (Luo et al., 2011). Kermanizadeh et al. (2014) demonstrated downregulation of IL-1β after MWCNT exposure, indicating the inhibition of neuroinflammation. Meanwhile, others found an increase in the expression of IL-1β in mice following exposure to MWCNTs (Hamilton et al., 2013; Kido et al., 2014; HelmyAbdou et al., 2019). It has been reported that oxidation-shortened amino-functionalized MWNT and amino-functionalized MWNT induced a transient increase in almost all pro-inflammatory cytokines (Bardi et al., 2013). Rats exposed to MWCNTs showed an increase in the expression of IL-1β compared with a control group, while the rate of TNF-α expression in male albino rats was significantly increased after MWCNT exposure (Kido et al., 2014; HelmyAbdou et al., 2019). However, another study revealed a decrease in the rate of TNF-α expression after MWCNT exposure (Kermanizadeh et al., 2014). In addition, MWCNT exposure resulted in neuroinflammatory responses via BBB impairment in cerebrovascular endothelial cells treated with serum from MWCNT-exposed mice (Aragon et al., 2017). Therefore, most CNTs can be used as an effective drug delivery system for neuroinflammation.

Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs)

GQDs exhibit similar physical and chemical properties to graphene. GQDs are novel 2D nanomaterials composed of graphene nanosheets with a lateral size below 10 nm and ten graphene layers forming the final particle (Ponomarenko et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). GQDs have been considered to alleviate immune-mediated neuroinflammation in a dark agouti (DA) rat model of chronic relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) via the activation of MAPK/Akt signaling and the suppression of the encephalitogenic Th1 immune response, as well as inflammatory cytokine IL-10, IL-17, and IFN-γ (Tosic et al., 2019). In addition, GQDs inhibit fibrillization of α-synuclein, trigger their disaggregation, and rescue neuronal death against PD (Kim et al., 2018b). GQDs have a potential therapeutic effect for AD by inhibiting the aggregation of Aβ1-42 peptides (Mahmoudi et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). Besides this, curcumin-GQDs can be used as a platform to sense APO e4 DNA, which is responsible for AD (Mars et al., 2018). Therefore, GQDs are considered a promising therapeutic strategy for neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease.

Neurotoxicity of Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials have wide applications in neutral inflammation therapy with exciting therapeutic effects. However, some researchers have raised questions about the toxicity of nanoparticles, because at nanoscale many atoms may become very active. Therefore, toxicity, and especially neurotoxicity, of nanoparticles for neuroinflammation therapy must be taken into account.

Neurotoxicity refers to any adverse effect on the structure, function, or chemistry of the nervous system produced by physical or chemical causes (Teleanu et al., 2019). The main mechanisms for neurotoxicity involve the excessive production of reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative stress; the release of cytokines causing neuroinflammation; and dysregulations of apoptosis leading to neuronal death (Teleanu et al., 2018). Neurotoxicity of nanoparticles is closely connected with different parameters of nanoparticles like their shape, dosage, size, surface area, and so on. Among the parameters, the size and surface area are the key determinants of toxicity (Saifi et al., 2018). NPs that are commonly used have been studied for potential neurotoxic effects. For example, AuNPs might cause astrogliosis, which is defined as an increase in the number and size of astrocytes and cognition defects including attention and memory impairment. Astrogliosis is closely connected with hypoxia, ischemia, and seizures in brain diseases, and is commonly observed in AD patients (Saijo et al., 2010; Flora, 2017). A high dose of anatase TiO2NPs significantly increased the IL-6 level in plasma and brain, suggesting that oral intake of anatase TiO2NPs could induce neuroinflammation and neurotoxic effects (Grissa et al., 2016). IONPs exposure may affect synaptic transmission and nerve conduction (Kumari et al., 2012), causing immune cell infiltration and neural inflammation apoptosis (Wu et al., 2010), inducing oxidative damage in the striatum but not in the hippocampus (Kim et al., 2013). A study showed the drug-free liposomes induced neuropathologic changes, specifically neuroinflammation and necrosis (Yuan et al., 2015). Another study showed that the accumulation of Polysorbate 80-modified chitosan nanoparticles induced neuronal apoptosis, a slight inflammatory response and increased oxidative stress (Huo et al., 2012). Generally, inorganic NPs show more frequent and severe toxicity than organic nanoparticles (Mohammadpour et al., 2019). Most NPs exhibit anti-neuroinflammatory effects either alone or by carrying anti-inflammatory drugs; however, some NPs induce neuroinflammation.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Neuroinflammation is an inflammatory response within the CNS that is marked by the activation of microglia and astrocytes and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Neuroinflammation is the common mechanism behind CNS-related diseases including acute brain injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by gradual cognitive or memory impairment and movement disorder. They pose a severe threat to people’s health and lower their quality-of-life, especially affecting the elderly population. The treatment of neuroinflammation is faced with many difficulties owing to the poor BBB penetration of drugs. Nanomaterials, an emerging therapeutic tool, may help overcome this obstacle and improve the effect of drugs on anti-neuroinflammation. NPs are a promising delivery system that can combine with drugs by dissolution, adsorption, encapsulation or covalent bonding and be used in the treatment of CNS disorders. The superiorities of NPs enable them to reduce enzymatic degradation, clearance by endothelial cells, and peripheral side effects, while increasing targeting and bioavailability and helping overcome the obstacle of the BBB.

To date, neurodegenerative diseases have affected millions of people worldwide, placing a serious financial and spiritual burden on societies and families. AD and PD are the most common neurodegenerative diseases. Although some drugs can alleviate their symptoms, there are still no drugs approved for the treatment of AD and PD. The BBB penetration of various drugs with potent neuroprotective effects, such as anti-inflammatory drugs in microglia and anti-apoptosis in neurons, is limited. The development of NPs represents a promising strategy for the improvement of the BBB penetration and neuroprotective effect of these drugs (Figure 4). For example, l-DOPA-AuNF improved the penetration of l-DOPA across the BBB (Gonzalez-Carter et al., 2019). ApoE3 polymeric nanoparticles loaded with donepezil showed an enhanced brain uptake of the drug, binding to amyloid beta with high affinity and accelerating its clearance (Krishna et al., 2019). Therefore, it is important to further develop the NPs with high BBB penetration capacity to encapsulate drugs with potent anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis effects such as galantamine, noferriamine, rivarasmine, risperidone, curcumin, quercetin, and ropinirole (Cao et al., 2016; Agrawal et al., 2018; Dudhipala and Gorre, 2020) for the treatment of AD and PD in the future.

FIGURE 4. The potential therapeutic effect of NPs on the inflammatory response, neuronal death, depolarization of the nerve, and BBB disruption in CNS-diseases including AD, PD, HD, ALS, and MS.

In addition to the inherent characteristics of NPs, a variety of artificial designs have been developed to further improve performance by altering their size, surface area, surface charge, hydrophilicity and lipophilicity for the treatment of neuroinflammation. For example, binding with polyethylene glycol and polysaccharides prolongs the residence time of NPs. Transferrin-conjugated NPs exhibit higher permeability of the BBB. Prednisolone-loaded liposomes, nanoemulsions with oils rich in omega3 PUFA, polyclonal antibodies against brain-specific antigen and insulin-attached micelles, apolipoprotein E attached SLNs, G4HisMal, and D-mino dendrimers have all exhibited increased targeting of brain tissue (Naqvi et al., 2020).

The synthesis of multifunctional NPs is a hot research topic. Each NP has its own merits and drawbacks. In some cases, the properties of NPs are not compatible with drug binding, drug delivery, crossing the BBB, localization, and drug release (Kim et al., 2018a; Habibi et al., 2020). Therefore, by integrating NPs of different sizes, structures, and functions, multicomponent and multifunctional NPs are designed and their superior characteristics, (e.g. specific-targeting and long-circulation time) can be maximized. In recent years, some researchers have reported the application of PEG-cationic bovine serum albumin (Liu et al., 2013a), PEG-PLA NPs (Liu et al., 2013b), PEG–PLGA NPs (Zhang et al., 2014), chitosan-coated nanoemulsions (Fachel et al., 2020a), mSPAM (Rajendrakumar et al., 2018), and CeNC/IONC/MSN-T807 (Chen et al., 2018) as therapeutic strategies for neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease. Multifunctional NPs have extensive application prospects and warrant further exploration.

However, the drawbacks of NPs cannot be ignored. In the last decade, many studies reported that nanomaterials induce pro-inflammatory responses, apoptosis, and excessive oxidative stress of neurons in the brain. In addition, NPs were also demonstrated to accumulate in the liver, kidney and spleen, which may pose a threat to long-term health after administration. Considering these issues, the application of only those organic and degradable NPs with relatively minimal toxicity could be a possible solution. Furthermore, investigations of these nanomaterials in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics are still limited, and their side effects remain to be explored.

NPs are still making their way from bench to clinical application, and many more studies are needed to solve the outstanding problems regarding the treatment of neuroinflammation.

Author Contributions

A-GW and Q-ZF conceived the idea. F-DZ, Y-JH, and LY, wrote the original manuscript. X-GZ, J-MW, and D-LQ revised the manuscript. A-GW and YT draw the figures. F-DZ and Y-JH summarized the tables. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81903829 and 81801398), The Science and Technology Planning Project of Sichuan Province, China (Grant no. 2018JY0474, 2019JDPT0010, 2019YFSY0014, 21RCYJ0021, 2020YJ0494, 202086, and 2021YJ0180), the joint project between Luzhou Municipal People's Government and Southwest Medical University, China (Grant no. 2019LZXNYDJ02, 2018LZXNYD-ZK41, 2018LZXNYD-ZK42, 2018LZXNYD-PT02, 2019LZXNYDJ05, 2020LZXNYDJ37, and 2020LZXNYDJ37), Luzhou Science and Technology Program (No. 2018-JYJ-41), the Foundation of Southwest Medical University (No. 2017-ZRZD-003), and the Collaborative Project of Luzhou TCM Hospital and Southwest Medical University (No. 2017-LH011). Ph.D. Research Startup Foundation of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University (No. 17136).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Agostinho, P., A. Cunha, R., and Oliveira, C. (2010). Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress and the Pathogenesis of Alzheimers Disease. Cpd 16 (25), 2766–2778. doi:10.2174/138161210793176572

Agrawal, M., Saraf, S., Saraf, S., Antimisiaris, S. G., Chougule, M. B., Shoyele, S. A., et al. (2018). Nose-to-brain Drug Delivery: An Update on Clinical Challenges and Progress towards Approval of Anti-alzheimer Drugs. J. Control. Release 281, 139–177. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.05.011

Agrawal, M., Tripathi, D. K., Mourtas, S., Saraf, S., Antimisiaris, S. G., Hammarlund-Udenaes, M., et al. (2017). Recent Advancements in Liposomes Targeting Strategies to Cross Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Control. Release 260, 61–77. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.05.019

Alawieyah Syed Mortadza, S., Sim, J. A., Neubrand, V. E., and Jiang, L. H. (2018). A Critical Role of TRPM2 Channel in Abeta42 -induced Microglial Activation and Generation of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha. Glia 66 (3), 562–575. doi:10.1002/glia.23265

Alcendor, D. J., Charest, A. M., Zhu, W. Q., Vigil, H. E., and Knobel, S. M. (2012). Infection and Upregulation of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Human Brain Vascular Pericytes by Human Cytomegalovirus. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 95. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-9-95

Allaman, I., Belanger, M., and Magistretti, P. J. (2011). Astrocyte-neuron Metabolic Relationships: for Better and for Worse. Trends Neurosci. 34 (2), 76–87. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2010.12.001

Aragon, M. J., Topper, L., Tyler, C. R., Sanchez, B., Zychowski, K., Young, T., et al. (2017). Serum-borne Bioactivity Caused by Pulmonary Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Induces Neuroinflammation via Blood-Brain Barrier Impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114 (10), E1968–E1976. doi:10.1073/pnas.1616070114

Araujo, R. V., Santos, S. D. S., Igne Ferreira, E., and Giarolla, J. (2018). New Advances in General Biomedical Applications of PAMAM Dendrimers. Molecules 23 (11), 2849. doi:10.3390/molecules23112849

Arvizo, R. R., Miranda, O. R., Moyano, D. F., Walden, C. A., Giri, K., Bhattacharya, R., et al. (2011). Modulating Pharmacokinetics, Tumor Uptake and Biodistribution by Engineered Nanoparticles. PLoS One 6 (9), e24374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024374

Asai, H., Ikezu, S., Woodbury, M. E., Yonemoto, G. M., Cui, L., and Ikezu, T. (2014). Accelerated Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation in Transgenic Mice Expressing P301L Tau Mutant and Tau-Tubulin Kinase 1. Am. J. Pathol. 184 (3), 808–818. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.026

Avasthi, A., Caro, C., Pozo-Torres, E., Leal, M., and García-Martín, M. (2020). Magnetic Nanoparticles as MRI Contrast Agents. Top. Curr. Chem. (Cham) 378 (3), 40. doi:10.1007/s41061-020-00302-w

Azeem, A., Talegaonkar, S., Negi, L. M., Ahmad, F. J., Khar, R. K., and Iqbal, Z. (2012). Oil Based Nanocarrier System for Transdermal Delivery of Ropinirole: a Mechanistic, Pharmacokinetic and Biochemical Investigation. Int. J. Pharm. 422 (1-2), 436–444. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.039

Bahamonde, J., Brenseke, B., Chan, M. Y., Kent, R. D., Vikesland, P. J., and Prater, M. R. (2018). Gold Nanoparticle Toxicity in Mice and Rats: Species Differences. Toxicol. Pathol. 46 (4), 431–443. doi:10.1177/0192623318770608

Banerjee, S., and Pillai, J. (2019). Solid Lipid Matrix Mediated Nanoarchitectonics for Improved Oral Bioavailability of Drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 15 (6), 499–515. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1621289

Bardi, G., Nunes, A., Gherardini, L., Bates, K., Al-Jamal, K. T., Gaillard, C., et al. (2013). Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes in the Brain: Cellular Internalization and Neuroinflammatory Responses. PLoS One 8 (11), e80964. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080964

Baskin, J., Jeon, J. E., and Lewis, S. J. G. (2020). Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Parkinson's Disease. J. Neurol. 268, 1981-1994. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10291-x

Cano, A., Ettcheto, M., Espina, M., Auladell, C., Calpena, A. C., Folch, J., et al. (2018). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate Loaded PEGylated-PLGA Nanoparticles: A New Anti-seizure Strategy for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Nanomedicine 14 (4), 1073–1085. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2018.01.019

Cao, X., Hou, D., Wang, L., Li, S., Sun, S., Ping, Q., et al. (2016). Effects and Molecular Mechanism of Chitosan-Coated Levodopa Nanoliposomes on Behavior of Dyskinesia Rats. Biol. Res. 49 (1), 32. doi:10.1186/s40659-016-0093-4

Carita, A. C., Eloy, J. O., Chorilli, M., Lee, R. J., and Leonardi, G. R. (2018). Recent Advances and Perspectives in Liposomes for Cutaneous Drug Delivery. Curr. Med. Chem. 25 (5), 606–635. doi:10.2174/0929867324666171009120154

Casella, G., Garzetti, L., Gatta, A. T., Finardi, A., Maiorino, C., Ruffini, F., et al. (2016). IL4 Induces IL6-producing M2 Macrophages Associated to Inhibition of Neuroinflammation In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Neuroinflammation 13 (1), 139. doi:10.1186/s12974-016-0596-5

Cellot, G., Cilia, E., Cipollone, S., Rancic, V., Sucapane, A., Giordani, S., et al. (2009). Carbon Nanotubes Might Improve Neuronal Performance by Favouring Electrical Shortcuts. Nat. Nanotechnol 4 (2), 126–133. doi:10.1038/nnano.2008.374

Chamorro, A., Lo, E. H., Renu, A., van Leyden, K., and Lyden, P. D. (2021). The Future of Neuroprotection in Stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92 (2), 129–135. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2020-324283

Chauhan, A. S. (2018). Dendrimers for Drug Delivery. Molecules 23 (4), 938. doi:10.3390/molecules23040938

Chen, B., He, X. Y., Yi, X. Q., Zhuo, R. X., and Cheng, S. X. (2015). Dual-peptide-functionalized Albumin-Based Nanoparticles with Ph-dependent Self-Assembly Behavior for Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 7 (28), 15148–15153. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b03866

Chen, Q., Du, Y., Zhang, K., Liang, Z., Li, J., Yu, H., et al. (2018). Tau-Targeted Multifunctional Nanocomposite for Combinational Therapy of Alzheimer's Disease. ACS Nano 12 (2), 1321–1338. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b07625

Chen, X., Wu, G., Zhang, Z., Ma, X., and Liu, L. (2020). Neurotoxicity of Mn3O4 Nanoparticles: Apoptosis and Dopaminergic Neurons Damage Pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ. Saf. 188, 109909. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109909

Choi, B. K., Choi, M. G., Kim, J. Y., Yang, Y., Lai, Y., Kweon, D. H., et al. (2013). Large Alpha-Synuclein Oligomers Inhibit Neuronal SNARE-Mediated Vesicle Docking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110 (10), 4087–4092. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218424110

Choi, J. Y., Kim, M. J., Kim, J. H., Kim, S. H., Ko, H. K., Lim, J. S., et al. (2006). Detection of Hepatic Metastasis: Manganese- and Ferucarbotran-Enhanced MR Imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 60 (1), 84–90. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.06.016

Colmenares, J. C., and Kuna, E. (2017). Photoactive Hybrid Catalysts Based on Natural and Synthetic Polymers: A Comparative Overview. Molecules 22 (5). doi:10.3390/molecules22050790

Corcia, P., Tauber, C., Vercoullie, J., Arlicot, N., Prunier, C., Praline, J., et al. (2012). Molecular Imaging of Microglial Activation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS One 7 (12), e52941. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052941

Correia, A. T., Rebelo, D., Marques, J., and Nunes, B. (2019). Effects of the Chronic Exposure to Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Oncorhynchus mykiss: Assessment of Oxidative Stress, Neurotoxicity and Histological Alterations. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 68, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2019.02.012

Cupaioli, F. A., Zucca, F. A., Boraschi, D., and Zecca, L. (2014). Engineered Nanoparticles. How Brain Friendly Is This New Guest? Prog. Neurobiol. 119-120, 20–38. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.05.002

Dernedde, J., Rausch, A., Weinhart, M., Enders, S., Tauber, R., Licha, K., et al. (2010). Dendritic Polyglycerol Sulfates as Multivalent Inhibitors of Inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107 (46), 19679–19684. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003103107

Dias, A. P., da Silva Santos, S., da Silva, J. V., Parise-Filho, R., Igne Ferreira, E., Seoud, O. E., et al. (2020). Dendrimers in the Context of Nanomedicine. Int. J. Pharm. 573, 118814. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118814

Dinali, R., Ebrahiminezhad, A., Manley-Harris, M., Ghasemi, Y., and Berenjian, A. (2017). Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Modern Microbiology and Biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 43 (4), 493–507. doi:10.1080/1040841X.2016.1267708

DiSabato, D. J., Quan, N., and Godbout, J. P. (2016). Neuroinflammation: the Devil Is in the Details. J. Neurochem. 139 (Suppl. 2), 136–153. doi:10.1111/jnc.13607

Dos Santos Tramontin, N., da Silva, S., Arruda, R., Ugioni, K. S., Canteiro, P. B., de Bem Silveira, G., et al. (2020). Gold Nanoparticles Treatment Reverses Brain Damage in Alzheimer's Disease Model. Mol. Neurobiol. 57 (2), 926–936. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-01780-w

Du, Q., Ge, D., Mirshafiee, V., Chen, C., Li, M., Xue, C., et al. (2019). Assessment of Neurotoxicity Induced by Different-Sized Stober Silica Nanoparticles: Induction of Pyroptosis in Microglia. Nanoscale 11 (27), 12965–12972. doi:10.1039/c9nr03756j

Du, Y., Lai, P. T., Leung, C. H., and Pong, P. W. (2013). Design of Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (9), 18682–18710. doi:10.3390/ijms140918682

Ducray, A. D., Stojiljkovic, A., Moller, A., Stoffel, M. H., Widmer, H. R., Frenz, M., et al. (2017). Uptake of Silica Nanoparticles in the Brain and Effects on Neuronal Differentiation Using Different In Vitro Models. Nanomedicine 13 (3), 1195–1204. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2016.11.001

Dudhipala, N., and Gorre, T. (2020). Neuroprotective Effect of Ropinirole Lipid Nanoparticles Enriched Hydrogel for Parkinson's Disease: In Vitro, Ex Vivo, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation. Pharmaceutics 12 (5), 448. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12050448

Dugger, B. N., and Dickson, D. W. (2017). Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 9 (7). a028035. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a028035

Duncan, B., Kim, C., and Rotello, V. M. (2010). Gold Nanoparticle Platforms as Drug and Biomacromolecule Delivery Systems. J. Control. Release 148 (1), 122–127. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.004

Durfee, P. N., Lin, Y. S., Dunphy, D. R., Muniz, A. J., Butler, K. S., Humphrey, K. R., et al. (2016). Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Supported Lipid Bilayers (Protocells) for Active Targeting and Delivery to Individual Leukemia Cells. ACS Nano 10 (9), 8325–8345. doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b02819

Durocher, I., and Girard, D. (2016). In vivo proinflammatory Activity of Generations 0-3 (G0-G3) Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) Nanoparticles. Inflamm. Res. 65 (9), 745–755. doi:10.1007/s00011-016-0959-5

Eatemadi, A., Daraee, H., Karimkhanloo, H., Kouhi, M., Zarghami, N., Akbarzadeh, A., et al. (2014). Carbon Nanotubes: Properties, Synthesis, Purification, and Medical Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 9 (1), 393. doi:10.1186/1556-276X-9-393

Echazu, M. I. A., Tuttolomondo, M. V., Foglia, M. L., Mebert, A. M., Alvarez, G. S., and Desimone, M. F. (2016). Advances in Collagen, Chitosan and Silica Biomaterials for Oral Tissue Regeneration: from Basics to Clinical Trials. J. Mater. Chem. B 4 (43), 6913–6929. doi:10.1039/c6tb02108e

Eftekharzadeh, B., Daigle, J. G., Kapinos, L. E., Coyne, A., Schiantarelli, J., Carlomagno, Y., et al. (2018). Tau Protein Disrupts Nucleocytoplasmic Transport in Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron 99 (5), 925–940. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.039

Fachel, F. N. S., Dal Pra, M., Azambuja, J. H., Endres, M., Bassani, V. L., Koester, L. S., et al. (2020a). Glioprotective Effect of Chitosan-Coated Rosmarinic Acid Nanoemulsions against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Rat Astrocyte Primary Cultures. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 40 (1), 123–139. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00727-y

Fachel, F. N. S., Michels, L. R., Azambuja, J. H., Lenz, G. S., Gelsleichter, N. E., Endres, M., et al. (2020b). Chitosan-coated Rosmarinic Acid Nanoemulsion Nasal Administration Protects against LPS-Induced Memory Deficit, Neuroinflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Wistar Rats. Neurochem. Int. 141, 104875. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104875

Fan, S., Zheng, Y., Liu, X., Fang, W., Chen, X., Liao, W., et al. (2018). Curcumin-loaded PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles Conjugated with B6 Peptide for Potential Use in Alzheimer's Disease. Drug Deliv. 25 (1), 1091–1102. doi:10.1080/10717544.2018.1461955

Figuerola, A., Di Corato, R., Manna, L., and Pellegrino, T. (2010). From Iron Oxide Nanoparticles towards Advanced Iron-Based Inorganic Materials Designed for Biomedical Applications. Pharmacol. Res. 62 (2), 126–143. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2009.12.012

Flora, S. J. S. (2017). The Applications, Neurotoxicity, and Related Mechanism of Gold Nanoparticles. in Neurotoxicity of Nanomaterials and Nanomedicine (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 179–203. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-804598-5.00008-8

Frohlich, E. (2012). The Role of Surface Charge in Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Medical Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7, 5577–5591. doi:10.2147/IJN.S36111

Gabizon, A. A., Patil, Y., and La-Beck, N. M. (2016). New Insights and Evolving Role of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin in Cancer Therapy. Drug Resist. Updat 29, 90–106. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2016.10.003

Ganesan, P., Kim, B., Ramalaingam, P., Karthivashan, G., Revuri, V., Park, S., et al. (2019). Antineuroinflammatory Activities and Neurotoxicological Assessment of Curcumin Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles on LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia Cell Models. Molecules 24 (6). 1170. doi:10.3390/molecules24061170

Gargiulo, S., Anzilotti, S., Coda, A. R., Gramanzini, M., Greco, A., Panico, M., et al. (2016). Imaging of Brain TSPO Expression in a Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with (18)F-DPA-714 and Micro-PET/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 43 (7), 1348–1359. doi:10.1007/s00259-016-3311-y

Gonzalez-Carter, D. A., Ong, Z. Y., McGilvery, C. M., Dunlop, I. E., Dexter, D. T., and Porter, A. E. (2019). L-DOPA Functionalized, Multi-Branched Gold Nanoparticles as Brain-Targeted Nano-Vehicles. Nanomedicine 15 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2018.08.011

Grissa, I., Guezguez, S., Ezzi, L., Chakroun, S., Sallem, A., Kerkeni, E., et al. (2016). The Effect of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Neuroinflammation Response in Rat Brain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23 (20), 20205–20213. doi:10.1007/s11356-016-7234-8

Gupta, G., Gliga, A., Hedberg, J., Serra, A., Greco, D., Odnevall Wallinder, I., et al. (2020). Cobalt Nanoparticles Trigger Ferroptosis-like Cell Death (Oxytosis) in Neuronal Cells: Potential Implications for Neurodegenerative Disease. FASEB J. 34 (4), 5262–5281. doi:10.1096/fj.201902191RR

Gupta, J., Fatima, M. T., Islam, Z., Khan, R. H., Uversky, V. N., and Salahuddin, P. (2019). Nanoparticle Formulations in the Diagnosis and Therapy of Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 130, 515–526. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.156

Habibi, N., Quevedo, D. F., Gregory, J. V., and Lahann, J. (2020). Emerging Methods in Therapeutics Using Multifunctional Nanoparticles. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 12 (4), e1625. doi:10.1002/wnan.1625

Hajebi, S., Rabiee, N., Bagherzadeh, M., Ahmadi, S., Rabiee, M., Roghani-Mamaqani, H., et al. (2019). Stimulus-responsive Polymeric Nanogels as Smart Drug Delivery Systems. Acta Biomater. 92, 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.018

Hamilton, R. F., Wu, Z., Mitra, S., Shaw, P. K., and Holian, A. (2013). Effect of MWCNT Size, Carboxylation, and Purification on In Vitro and In Vivo Toxicity, Inflammation and Lung Pathology. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 10 (1), 57. doi:10.1186/1743-8977-10-57

Han, L., Cai, Q., Tian, D., Kong, D. K., Gou, X., Chen, Z., et al. (2016). Targeted Drug Delivery to Ischemic Stroke via Chlorotoxin-Anchored, Lexiscan-Loaded Nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 12 (7), 1833–1842. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2016.03.005

Hayder, M., Varilh, M., Turrin, C. O., Saoudi, A., Caminade, A. M., Poupot, R., et al. (2015). Phosphorus-Based Dendrimer ABP Treats Neuroinflammation by Promoting IL-10-Producing CD4(+) T Cells. Biomacromolecules 16 (11), 3425–3433. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00643

He, H., Lu, Y., Qi, J., Zhu, Q., Chen, Z., and Wu, W. (2019). Adapting Liposomes for Oral Drug Delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin B 9 (1), 36–48. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2018.06.005

HelmyAbdou, K. A., Ahmed, R. R., Ibrahim, M. A., and Abdel-Gawad, D. R. I. (2019). The Anti-inflammatory Influence of Cinnamomum Burmannii against Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Induced Liver Injury in Rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 26 (35), 36063–36072. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06707-5

Hu, H., Ni, Y., Montana, V., Haddon, R. C., and Parpura, V. (2004). Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes as Substrates for Neuronal Growth. Nano Lett. 4 (3), 507–511. doi:10.1021/nl035193d

Huang, H., Zhou, M., Ruan, L., Wang, D., Lu, H., Zhang, J., et al. (2019). AMPK Mediates the Neurotoxicity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Retained in Mitochondria or Lysosomes. Metallomics 11 (7), 1200–1206. doi:10.1039/c9mt00103d

Huo, T., Barth, R. F., Yang, W., Nakkula, R. J., Koynova, R., Tenchov, B., et al. (2012). Preparation, Biodistribution and Neurotoxicity of Liposomal Cisplatin Following Convection Enhanced Delivery in Normal and F98 Glioma Bearing Rats. PLoS One 7 (11), e48752. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048752

Hutter, E., and Maysinger, D. (2011). Gold Nanoparticles and Quantum Dots for Bioimaging. Microsc. Res. Tech. 74 (7), 592–604. doi:10.1002/jemt.20928

Ising, C., Venegas, C., Zhang, S., Scheiblich, H., Schmidt, S. V., Vieira-Saecker, A., et al. (2019). NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Drives Tau Pathology. Nature 575 (7784), 669–673. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1769-z

Islam, S. U., Shehzad, A., Ahmed, M. B., and Lee, Y. S. (2020). Intranasal Delivery of Nanoformulations: A Potential Way of Treatment for Neurological Disorders. Molecules 25 (8), 1929. doi:10.3390/molecules25081929

Jiang, Y., Gong, H., Jiang, S., She, C., and Cao, Y. (2020). Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes Decrease Neuronal NO Synthase in 3D Brain Organoids. Sci. Total Environ. 748, 141384. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141384

Jin, R., Lin, B., Li, D., and Ai, H. (2014). Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for MR Imaging and Therapy: Design Considerations and Clinical Applications. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 18, 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2014.08.002

Kang, Y. S., Jung, H. J., Oh, J. S., and Song, D. Y. (2016). Use of PEGylated Immunoliposomes to Deliver Dopamine across the Blood-Brain Barrier in a Rat Model of Parkinson's Disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 22 (10), 817–823. doi:10.1111/cns.12580

Kannan, S., Dai, H., Navath, R. S., Balakrishnan, B., Jyoti, A., Janisse, J., et al. (2012). Dendrimer-based Postnatal Therapy for Neuroinflammation and Cerebral Palsy in a Rabbit Model. Sci. Transl Med. 4 (130), 130ra146. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003162

Karami, Z., Khoshkam, M., and Hamidi, M. (2019a). Optimization of Olive Oil-Based Nanoemulsion Preparation for Intravenous Drug Delivery. Drug Res. (Stuttg) 69 (5), 256–264. doi:10.1055/a-0654-4867

Karami, Z., Saghatchi Zanjani, M. R., and Hamidi, M. (2019b). Nanoemulsions in CNS Drug Delivery: Recent Developments, Impacts and Challenges. Drug Discov. Today 24 (5), 1104–1115. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.021

Karthivashan, G., Ganesan, P., Park, S. Y., Kim, J. S., and Choi, D. K. (2018). Therapeutic Strategies and Nano-Drug Delivery Applications in Management of Ageing Alzheimer's Disease. Drug Deliv. 25 (1), 307–320. doi:10.1080/10717544.2018.1428243

Katsnelson, A., De Strooper, B., and Zoghbi, H. Y. (2016). Neurodegeneration: From Cellular Concepts to Clinical Applications. Sci. Transl Med. 8 (364), 364ps318. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2074

Kermanizadeh, A., Gaiser, B. K., Johnston, H., Brown, D. M., and Stone, V. (2014). Toxicological Effect of Engineered Nanomaterials on the Liver. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171 (17), 3980–3987. doi:10.1111/bph.12421

Khandhar, A. P., Ferguson, R. M., Arami, H., and Krishnan, K. M. (2013). Monodisperse Magnetite Nanoparticle Tracers for In Vivo Magnetic Particle Imaging. Biomaterials 34 (15), 3837–3845. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.087

Kido, T., Tsunoda, M., Kasai, T., Sasaki, T., Umeda, Y., Senoh, H., et al. (2014). The Increases in Relative mRNA Expressions of Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines in Splenic Macrophages from Rats Exposed to Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes by Whole-Body Inhalation for 13 Weeks. Inhal Toxicol. 26 (12), 750–758. doi:10.3109/08958378.2014.953275

Kim, C. K., Ghosh, P., and Rotello, V. M. (2009). Multimodal Drug Delivery Using Gold Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 1 (1), 61–67. doi:10.1039/b9nr00112c

Kim, D., Shin, K., Kwon, S. G., and Hyeon, T. (2018a). Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Multifunctional Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 30 (49), e1802309. doi:10.1002/adma.201802309

Kim, D., Yoo, J. M., Hwang, H., Lee, J., Lee, S. H., Yun, S. P., et al. (2018b). Graphene Quantum Dots Prevent Alpha-Synucleinopathy in Parkinson's Disease. Nat. Nanotechnol 13 (9), 812–818. doi:10.1038/s41565-018-0179-y

Kim, M. J., Rehman, S. U., Amin, F. U., and Kim, M. O. (2017). Enhanced Neuroprotection of Anthocyanin-Loaded PEG-Gold Nanoparticles against Abeta1-42-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration via the NF-KB/JNK/GSK3beta Signaling Pathway. Nanomedicine 13 (8), 2533–2544. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2017.06.022

Kim, Y., Kong, S. D., Chen, L. H., Pisanic, T. R., Jin, S., and Shubayev, V. I. (2013). In vivo nanoneurotoxicity Screening Using Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Paradigms. Nanomedicine 9 (7), 1057–1066. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2013.05.002

Koenigsknecht, J., and Landreth, G. (2004). Microglial Phagocytosis of Fibrillar Beta-Amyloid through a Beta1 Integrin-dependent Mechanism. J. Neurosci. 24 (44), 9838–9846. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-04.2004

Krishna, K. V., Wadhwa, G., Alexander, A., Kanojia, N., Saha, R. N., Kukreti, R., et al. (2019). Design and Biological Evaluation of Lipoprotein-Based Donepezil Nanocarrier for Enhanced Brain Uptake through Oral Delivery. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10 (9), 4124–4135. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00343

Kumari, A., Yadav, S. K., and Yadav, S. C. (2010). Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles Based Drug Delivery Systems. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 75 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.001

Kumari, M., Rajak, S., Singh, S. P., Kumari, S. I., Kumar, P. U., Murty, U. S., et al. (2012). Repeated Oral Dose Toxicity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Biochemical and Histopathological Alterations in Different Tissues of Rats. J. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 12 (3), 2149–2159. doi:10.1166/jnn.2012.5796

Lacroix, L. M., Gatel, C., Arenal, R., Garcia, C., Lachaize, S., Blon, T., et al. (2012). Tuning Complex Shapes in Platinum Nanoparticles: from Cubic Dendrites to Fivefold Stars. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51 (19), 4690–4694. doi:10.1002/anie.201107425

Li, J., Darabi, M., Gu, J., Shi, J., Xue, J., Huang, L., et al. (2016). A Drug Delivery Hydrogel System Based on Activin B for Parkinson's Disease. Biomaterials 102, 72–86. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.016

Li, L., Wu, G., Yang, G., Peng, J., Zhao, J., and Zhu, J. J. (2013). Focusing on Luminescent Graphene Quantum Dots: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Nanoscale 5 (10), 4015–4039. doi:10.1039/c3nr33849e

Li, M., Du, C., Guo, N., Teng, Y., Meng, X., Sun, H., et al. (2019a). Composition Design and Medical Application of Liposomes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 164, 640–653. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.007

Li, T., Cipolla, D., Rades, T., and Boyd, B. J. (2018). Drug Nanocrystallisation within Liposomes. J. Control. Release 288, 96–110. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.09.001

Li, W., Cao, Z., Liu, R., Liu, L., Li, H., Li, X., et al. (2019b). AuNPs as an Important Inorganic Nanoparticle Applied in Drug Carrier Systems. Artif. Cell Nanomed Biotechnol 47 (1), 4222–4233. doi:10.1080/21691401.2019.1687501

Li, X., Tsibouklis, J., Weng, T., Zhang, B., Yin, G., Feng, G., et al. (2017). Nano Carriers for Drug Transport across the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Drug Target. 25 (1), 17–28. doi:10.1080/1061186X.2016.1184272

Li, Y., He, H., Jia, X., Lu, W. L., Lou, J., and Wei, Y. (2012). A Dual-Targeting Nanocarrier Based on Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers Conjugated with Transferrin and Tamoxifen for Treating Brain Gliomas. Biomaterials 33 (15), 3899–3908. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.004

Liang, H., Chen, A., Lai, X., Liu, J., Wu, J., Kang, Y., et al. (2018). Neuroinflammation Is Induced by Tongue-Instilled ZnO Nanoparticles via the Ca(2+)-dependent NF-kappaB and MAPK Pathways. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 15 (1), 39. doi:10.1186/s12989-018-0274-0

Liu, D., Lin, B., Shao, W., Zhu, Z., Ji, T., and Yang, C. (2014). In vitro and In Vivo Studies on the Transport of PEGylated Silica Nanoparticles across the Blood-Brain Barrier. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 6 (3), 2131–2136. doi:10.1021/am405219u

Liu, H., Yang, H., Fang, Y., Li, K., Tian, L., Liu, X., et al. (2020a). Neurotoxicity and Biomarkers of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Main Functional Brain Regions and Dopaminergic Neurons. Sci. Total Environ. 705, 135809. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135809

Liu, H., Zhang, W., Fang, Y., Yang, H., Tian, L., Li, K., et al. (2020b). Neurotoxicity of Aluminum Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Mechanistic Role in Dopaminergic Neuron Injury Involving P53-Related Pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 392, 122312. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122312

Liu, S., Zhen, G., Li, R. C., and Dore, S. (2013a). Acute Bioenergetic Intervention or Pharmacological Preconditioning Protects Neuron against Ischemic Injury. J. Exp. Stroke Transl Med. 6, 7–17. doi:10.4172/1939-067X.1000140

Liu, Y., Xu, L. P., Dai, W., Dong, H., Wen, Y., and Zhang, X. (2015). Graphene Quantum Dots for the Inhibition of Beta Amyloid Aggregation. Nanoscale 7 (45), 19060–19065. doi:10.1039/c5nr06282a

Liu, Z., Gao, X., Kang, T., Jiang, M., Miao, D., Gu, G., et al. (2013b). B6 Peptide-Modified PEG-PLA Nanoparticles for Enhanced Brain Delivery of Neuroprotective Peptide. Bioconjug. Chem. 24 (6), 997–1007. doi:10.1021/bc400055h

Luo, X., Matranga, C., Tan, S., Alba, N., and Cui, X. T. (2011). Carbon Nanotube Nanoreservior for Controlled Release of Anti-inflammatory Dexamethasone. Biomaterials 32 (26), 6316–6323. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.020

Lyu, Z., Ding, L., Tintaru, A., and Peng, L. (2020). Self-Assembling Supramolecular Dendrimers for Biomedical Applications: Lessons Learned from Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Acc. Chem. Res. 53 (12), 2936–2949. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00589

Maezawa, I., Zimin, P. I., Wulff, H., and Jin, L. W. (2011). Amyloid-beta Protein Oligomer at Low Nanomolar Concentrations Activates Microglia and Induces Microglial Neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 286 (5), 3693–3706. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.135244

Mahmoudi, M., Akhavan, O., Ghavami, M., Rezaee, F., and Ghiasi, S. M. (2012). Graphene Oxide Strongly Inhibits Amyloid Beta Fibrillation. Nanoscale 4 (23), 7322–7325. doi:10.1039/c2nr31657a

Maiti, P., Paladugu, L., and Dunbar, G. L. (2018). Solid Lipid Curcumin Particles Provide Greater Anti-amyloid, Anti-inflammatory and Neuroprotective Effects Than Curcumin in the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. BMC Neurosci. 19 (1), 7. doi:10.1186/s12868-018-0406-3

Marlatt, M. W., Bauer, J., Aronica, E., van Haastert, E. S., Hoozemans, J. J., Joels, M., et al. (2014). Proliferation in the Alzheimer hippocampus Is Due to Microglia, Not Astroglia, and Occurs at Sites of Amyloid Deposition. Neural Plast. 2014, 693851. doi:10.1155/2014/693851