- Monash Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VI, Australia

The aim of this study was to understand which factors influence patients’ adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment recommendations in primary care. We adopted a qualitative study design, conducting phone interviews with 31 people with venous leg ulcers in Melbourne, Australia. We conducted 31 semi-structured phone interviews between October and December 2019 with patients with clinically diagnosed venous leg ulcers. Participants recruited to the Aspirin in Venous Leg Ulcer Randomized Control Trial and Cohort study were invited to participate in a qualitative study, which was nested under this trial. We applied the Theoretical Domains Framework to guide the data analysis. The following factors influenced patients’ adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment: understanding the management plan and rationale behind treatment (Knowledge Domain); compression-related body image issues (Social Influences); understanding consequences of not wearing compression (Beliefs about Consequences); feeling overwhelmed because it’s not getting better (Emotions); hot weather and discomfort when wearing compression (Environmental Context and Resources); cost of compression (Environmental Context and Resources); ability to wear compression (Beliefs about Capabilities); patience and persistence (Behavioral Regulation); and remembering self-care instructions (Memory, Attention and Decision Making). The Theoretical Domains Framework was useful for identifying factors that influence patients’ adherence to treatment recommendations for venous leg ulcers management. These factors may inform development of novel interventions to optimize shared decision making and self-care to improve healing outcomes. The findings from this article will be relevant to clinicians involved in management of patients with venous leg ulcers, as their support is crucial to patients’ treatment adherence. Consultation with patients about VLU treatment adherence is an opportunity for clinical practice to be targeted and collaborative. This process may inform guideline development.

Introduction

Venous leg ulcers (VLU) are chronic skin ulcers and are the most common chronic wound of the lower limbs in Australian primary care settings (Pacella et al., 2018). VLU are classified as C6 stage of a chronic venous disorder, as per the updated Clinical (C) version of Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) classification (Lurie et al., 2020). They are caused by chronic venous insufficiency due to persistent high blood pressure in varicose veins (Meulendijks et al., 2019; Weller et al., 2019). Best practice management recommendations for people with VLU are compression, leg elevation, physical exercise and adequate nutrition (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011).

The estimated VLU prevalence globally is between 1 and 3% of people (Graves and Zheng, 2014b; Domingues et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2018). Chronic wounds represent a considerable social and economic burden (KPMG, 2013; Graves and Zheng, 2014a), with an estimated annual cost of AUD $3 billion in Australia (Graves and Zheng, 2014), $32 billion in the United States (Nussbaum et al., 2018) and £50 million in the United Kingdom (Guest et al., 2017). Despite this burden, there is no international consensus on the best strategies for prevention and management of VLU (Franks et al., 2016; Weller et al., 2019). To address this health issue in Australia, the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for the prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011), (herein referred to as VLU CPG) was published in 2011. Despite the development and dissemination of VLU CPG (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011), a significant number of VLU remain unhealed (Franks et al., 2016), warranting further consideration of contributing factors to develop solutions to this silent epidemic (Pacella et al., 2018). The challenges faced when managing people with VLU are not unique to Australia (Franks et al., 2016). Compression use, as an example, has been reported as being problematic across Switzerland (Probst et al., 2020) and the United Kingdom (Guest et al., 2018).

Current best practice recommendations include assessment and diagnostic evaluation of the lower limb to exclude arterial causes prior to compression application (Weller et al., 2018), including venous ultrasound and/or assessment of Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI). Once arterial insufficiency is excluded, below knee multi-layer compression therapy is recommended (Andriessen et al., 2017; O'Meara et al., 2013). In instances where there is unclear aetiology or if the ulcer is not healed after three months of treatment, VLU CPG recommends the patient be referred to a specialized wound clinic (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011). In addition to recommendations surrounding assessment and compression, VLU CPG (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011) distinguishes the importance of preparing the VLU patients sufficiently and enabling them to co-participate and share in decision making in wound management (Ritchie and Taylor, 2018). Patients with VLUs would usually consult their GP in the first place. The support-seeking pathway that VLU patients are supposed to follow includes initial consultation by a GP, who should perform clinical assessment, including vascular assessment to exclude arterial involvement. In absence of arterial involvement, compression therapy should be prescribed and other recommendations provided, including leg elevation, adequate nutrition, pain management and physical exercise, as indicated in the guidelines (Australian Wound Management Association New Zealand Wound Care Society, 2011). In absence of healing improvement over three months, patients should be referred to tertiary clinic for assessment. Clinicians’ limited awareness about these guidelines, reliance on their clinical experience and suggestions from colleagues rather than clinical guidelines, and their limited skills in ABPI measurement and health system organisational issues, including absence of duplex ultrasound in some practices, lead to suboptimal management of patients with VLUs (Weller et al., 2019; Weller et al., 2020).

Optimal VLU treatment is collaborative, with patients tasked with specific self-care actions at home after VLU care tasks are demonstrated by clinicians in the clinical setting. These tasks may include, although will not be limited to compression application. Although patients usually attend regular scheduled review appointments, wound care is often done at home independently (Walburn et al., 2017). Current management of VLU continues to challenge patients and clinicians with reports of suboptimal VLU treatment (Franks et al., 2016). A recent study of data from the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program reported only 2.1% of VLU patients are treated with compression (Gethin et al., 2020). Furthermore, another study reported greater proportion of health professionals were unaware of the VLU CPG (Weller et al., 2020). Australia has limited available means for monitoring patterns and quality of care for people diagnosed with VLU as there is no clinical VLU registry (Weller and Evans, 2014) and, as a result, there is variation in the way VLU is managed in primary care settings. Clinician barriers to using and implementing evidence-based interventions for VLU treatment include limited awareness of the VLU CPG, organisational barriers, and suboptimal knowledge and skills of VLU management (Weller et al., 2019; Weller et al., 2020).

Clinicians reported patient adherence to VLU management plans was a key area of concern (Weller et al., 2020), specifically the application and long term use of compression therapy (Probst et al., 2019; Probst et al., 2020). Compression discomfort or pain (Boxall et al., 2019) can impact on compression adherence. Insufficient understanding of the benefits of compression treatment may contribute to non-adherence (Jull et al., 2004; Probst et al., 2020). The consequences of non-adherence to treatment recommendations include chronicity of VLUs, increased recurrence rate (Finlayson et al., 2018), infection (Bui et al., 2019) and secondary squamous cell carcinoma (Reich-Schupke et al., 2015). Disease progression (Meulendijks et al., 2020) and associated complications exacerbate wound pain (Leren et al., 2020), increase wound exudate, and reduce patients’ mobility, which in turn contributes to disease progression (Meulendijks et al., 2019), leads to premature disability (Mallick et al., 2020), and inadvertently influences patients’ quality of life (Barnsbee et al., 2019). Management of these complications require complex interventions and highlights the need for optimal care for this underestimated condition.

Adherence to evidence-based VLU management is not limited to compression use; education based interventions may improve adherence to leg elevation (Brooks et al., 2004) and therapeutic physical exercises (Kelechi et al., 2014). Despite this, clinician advice and education on VLU management is offered to less than 3.6% of VLU patients who attended primary health settings (Gethin et al., 2020). Few studies have examined the patient experience of adhering to VLU treatment (Weller et al., 2016) and patient education needs have yet to be fully understood (Shanley et al., 2020). Understanding patients’ behavior related to treatment adherence is important in planning and developing effective evidence-based interventions on VLU management (Presseau et al., 2019); and high-quality qualitative studies are required in order to understand patient behavior and to develop successful interventions. The aim of this study was to understand which barriers and enablers influence patients’ adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment recommendations in primary care settings.

Materials and Methods

Aim/s

The aim of this study was to understand barriers and enablers influencing patients’ adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment recommendations in primary care settings.

Design

We adopted a qualitative study design, and conducted 31 semi-structured phone interviews with VLU patients, who had participated in the Aspirin in Venous Leg Ulcer (ASPiVLU) clinical trial (Weller et al., 2016). The ASPiVLU study was a randomized, double-blinded, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial, which investigated if daily oral dose of aspirin (300 mg), as an adjunct to compression, improved time to healing for clinically diagnosed VLU patients (Weller et al., 2016). The study participants were aged 18 years and older with one or more VLUs in the presence of venous insufficiency confirmed by clinical assessment and/or duplex ultrasound. Other eligibility criteria included: 1) the target ulcer, was separated from other VLUs by at least 1 cm; 2) was present for at least six weeks 3) target ulcer area measured by digital planimetry techniques was between ≥1 cm2 to ≤20 cm2; 4) Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) was ≥ 0.7 mmHg or systolic toe pressure ≥ 50 mmHg to exclude arterial insufficiency; 5) the patient was able to provide informed consent (as per the medical practitioner’s clinical judgement). The participants were randomized to receive either aspirin or placebo for 24 weeks, adjuvant to compression. Time to healing within 12 weeks was the primary outcome of this study. Secondary outcomes were ulcer recurrence, wound pain, quality of life and wellbeing, adherence to compression therapy, adherence to study medication, serum inflammatory markers, number of hospitalisations, and adverse events at 24 weeks.

Sample/Participants

Seventy-two participants from the ASPiVLU study, who expressed their interest to participate in other studies, were given a phone call by the trial coordinator and invited to participate in this nested qualitative study. Nine people said that they were no longer interested in research participation without explaining the reason. Seven people declined because they were too busy working and traveling. Nine people said that they would be unable to participate in the phone interview due to hearing problems. Eight people were too sick. Their partners/carers said that their health deteriorated and provided the following main health issues: mental health issues, dementia, and a recent fall. Thirty-nine participants confirmed their interest to participate and agreed to be interviewed. Interviews with all participants that agreed to be interviewed were scheduled at a convenient for them time.

Data saturation was reached on 25th interview, while some voice files were still with transcription services. We considered we reached saturation when subsequent analysis did not generate any new TDF construct. In total, we interviewed 31 participants. Participants were reimbursed with a $25 Coles Myer gift-card for participation. The trial coordinator contacted remaining people who agreed to be interviewed to thank them for their interest in study participation and inform that we were no longer recruiting participants.

Theoretical Framework

To understand patients’ behavior related to VLU management adherence we were guided by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Michie et al., 2005). This framework provides a theory-informed method for analyzing determinants of behavior. The TDF comprises a collection of domains, the product of a consensus strategy to be used in implementation research (Michie et al., 2005). The first version of this framework was developed in 2005 (Atkins et al., 2017), and later appraised and redeveloped in 2017 (Haardörfer, 2019). The 2017 version (Atkins et al., 2017) of the TDF framework includes 14 domains which guided our research. The TDF domains cover Knowledge, Skills, Beliefs about Capabilities, Beliefs about Consequences, Environmental Context and Resources, Social Influences, Behavioral Regulation, Optimism, Emotions, Goals, Social/Professional Role and Identity, Reinforcement, Intentions and Memory, Attention, and Decision Making.

Data Collection

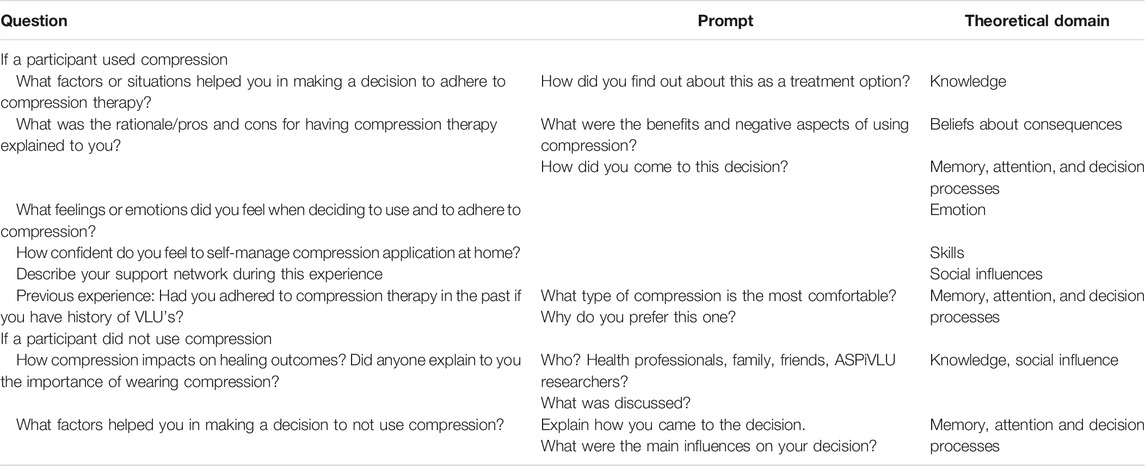

Data were collected, using the interview guide developed by CW and VT, and refined by LT and CW. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions loosely matching the TDF domains (2017 version), and did not cover all 14 TDF domains (Table 1). These questions were followed by a series of prompts that probed barriers and enablers influencing patient adherence or non-adherence to VLU treatment recommendations (Michie et al., 2005). Interview questions were able to be modified by the interviewer depending on the flow of the interview. The interview guide was not piloted.

Data collection took place between October 2019 and December 2019. Phone interviews were conducted by two experienced researchers (LT and CR) from the University office. All interviews were audio recorded, using a handheld recording device. Participant verbal consent was obtained prior to recording. The average interviewing time was 35 min, ranging between 12 and 87 min, depending on the participants availability and their willingness to discuss the details of VLU management. The audio files were transcribed verbatim using a professional transcription service. Transcripts were checked alongside voice files by LT and CR to ensure the accuracy of the transcribed text. The interview transcripts were not sent back for the participants’ verification.

Participant and VLU characteristics data were collected as part of the ASPiVLU RCT study. A comprehensive overview of participant details and wound characteristics enabled a comparison of the VLU participant group of this study and VLU patients in the wider community.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in line with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The University Human Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained for both the main study and a nested qualitative study. Site-specific approvals from the participating tertiary specialist clinics were received from the participating health services ethics committees.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using NVivo Version 12. We adopted a theory-driven conceptual analysis (Haardörfer, 2019) and utilized the TDF domains and constructs to guide our analysis (Atkins et al., 2017). Our coding framework was based on the TDF. CR conducted initial coding of the first three transcripts and developed the coding framework. The coding framework was then reviewed by VT and CW. Technically, utterances were mapped across a coding framework based on the TDF domains and associated constructs. We focused on barriers and enablers that influenced VLU patients’ decision to adhere to treatment recommendations in their care plan, which were then allocated to the relevant domains.

Results

Participant Characteristics

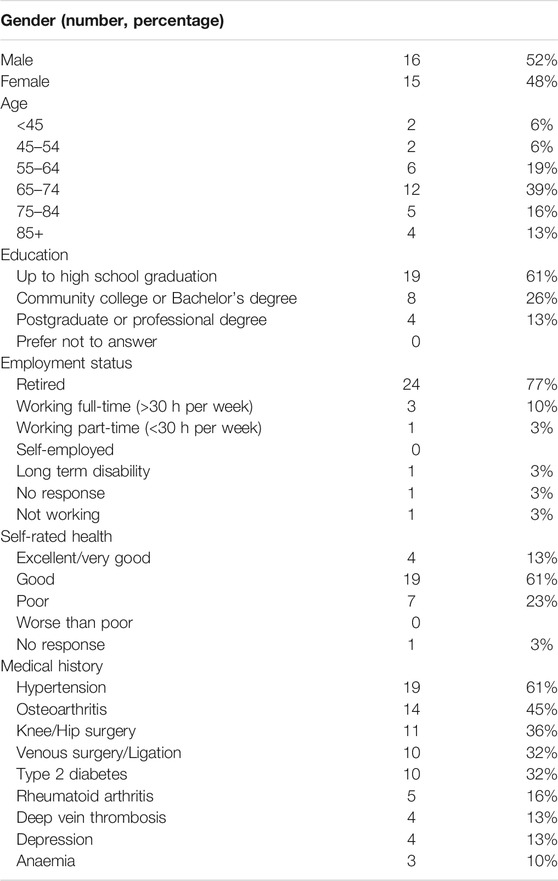

Thirty-one participants were included in this study: Sixteen participants (52%) were male and 15 (48%) were female. The mean age of participants was 64 years, ranging from 39 to 89. Medical history/comorbidities included hypertension (N = 19; 61%), osteoarthritis (N = 14; 45%), knee/hip surgery (N = 11, 35%), venous surgery/ligation (N = 10; 32%), type 2 diabetes (N = 10; 32%), rheumatoid arthritis (N = 5; 16%), deep vein thrombosis (N = 4; 13%), depression (N = 4; 13%), anaemia (N = 3, 10%). Additional socio-demographic details of the participants can be accessed in Table 2.

Summary of the Theoretical Domains Framework Domains

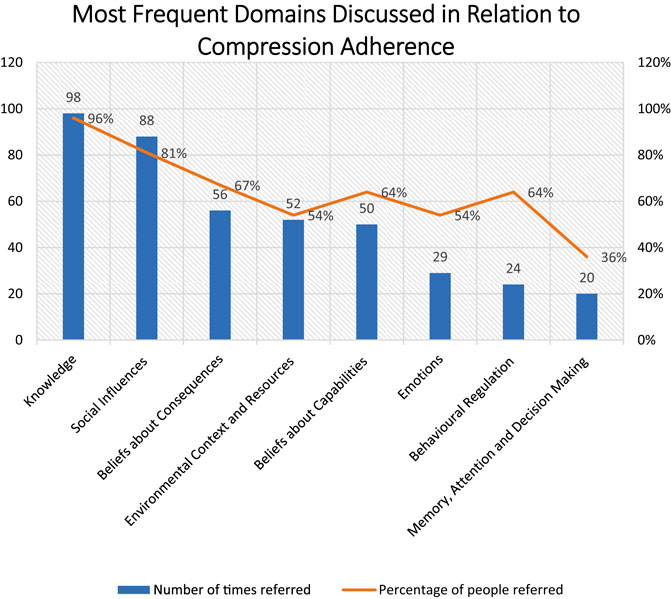

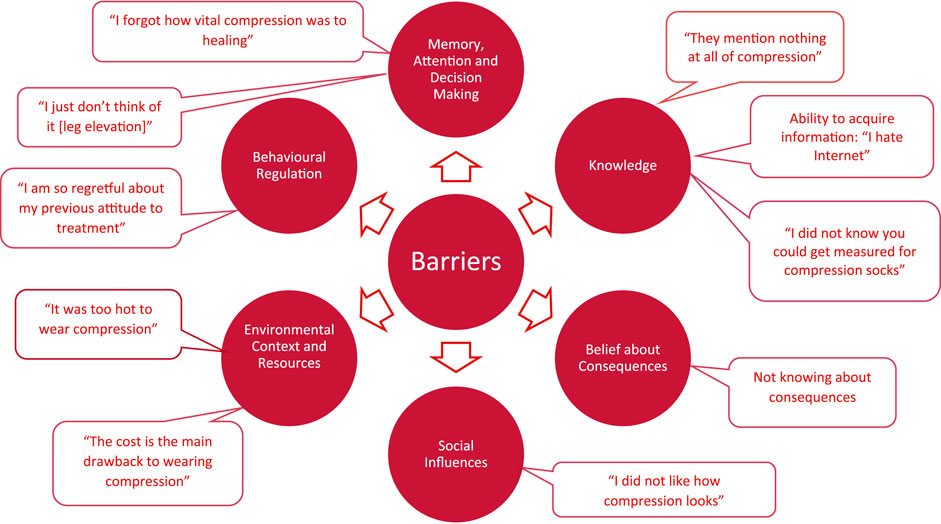

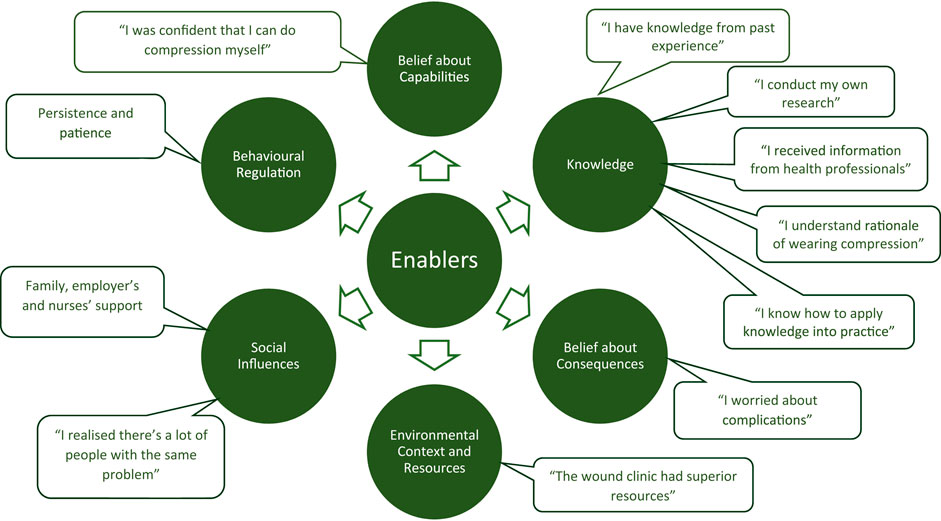

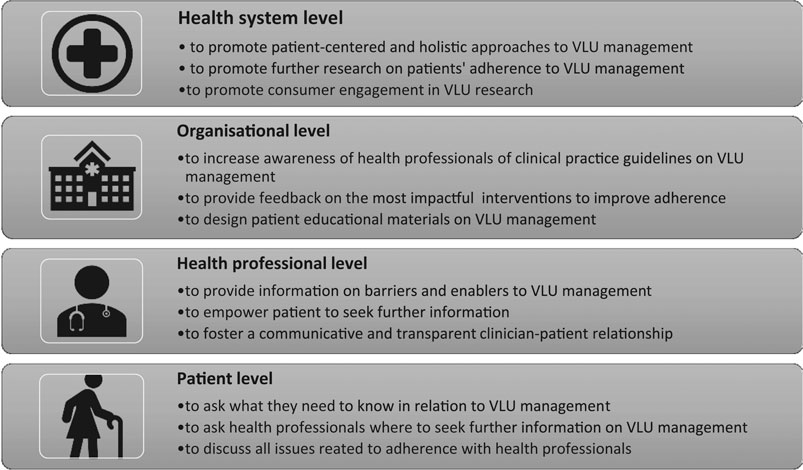

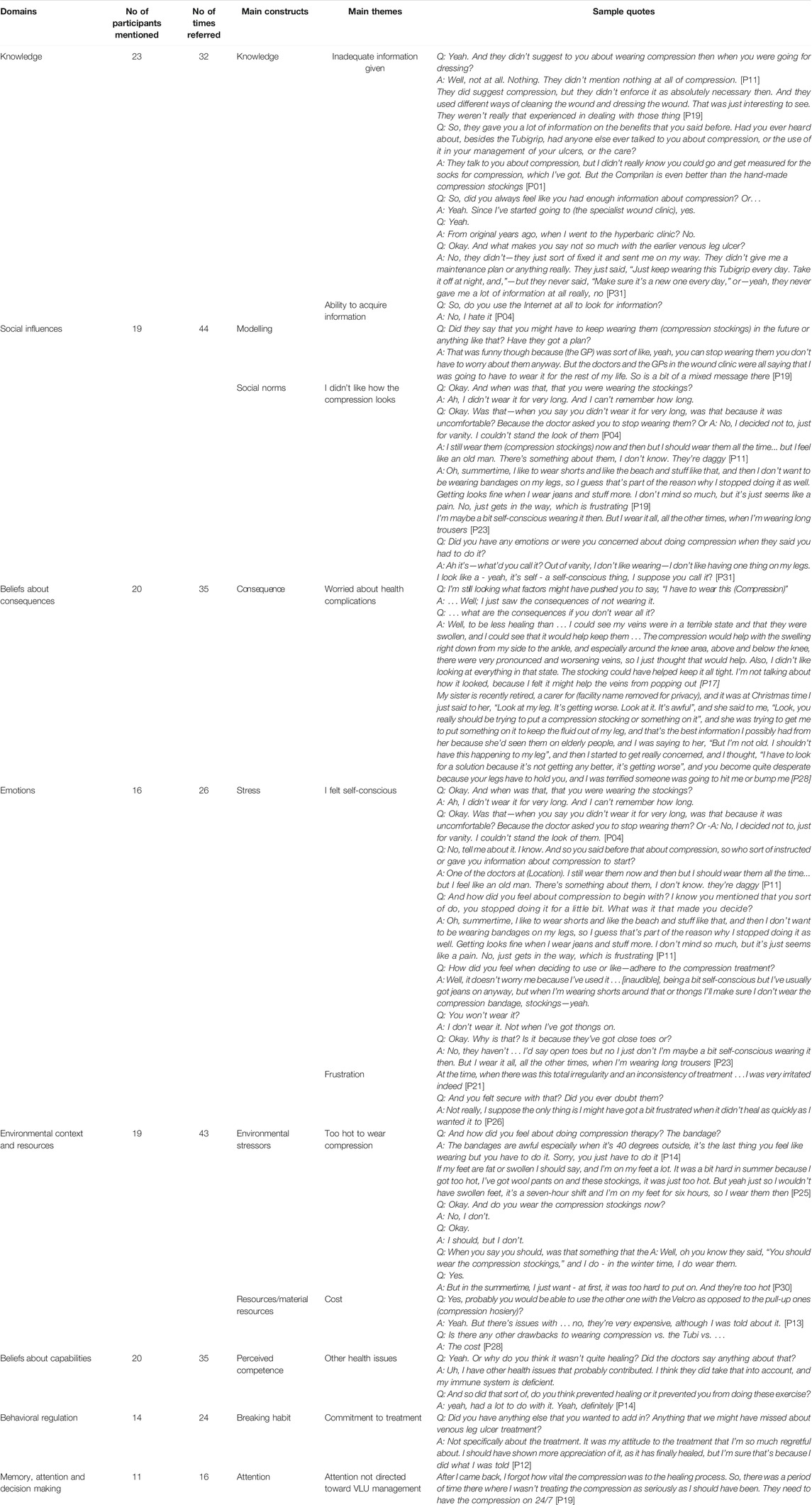

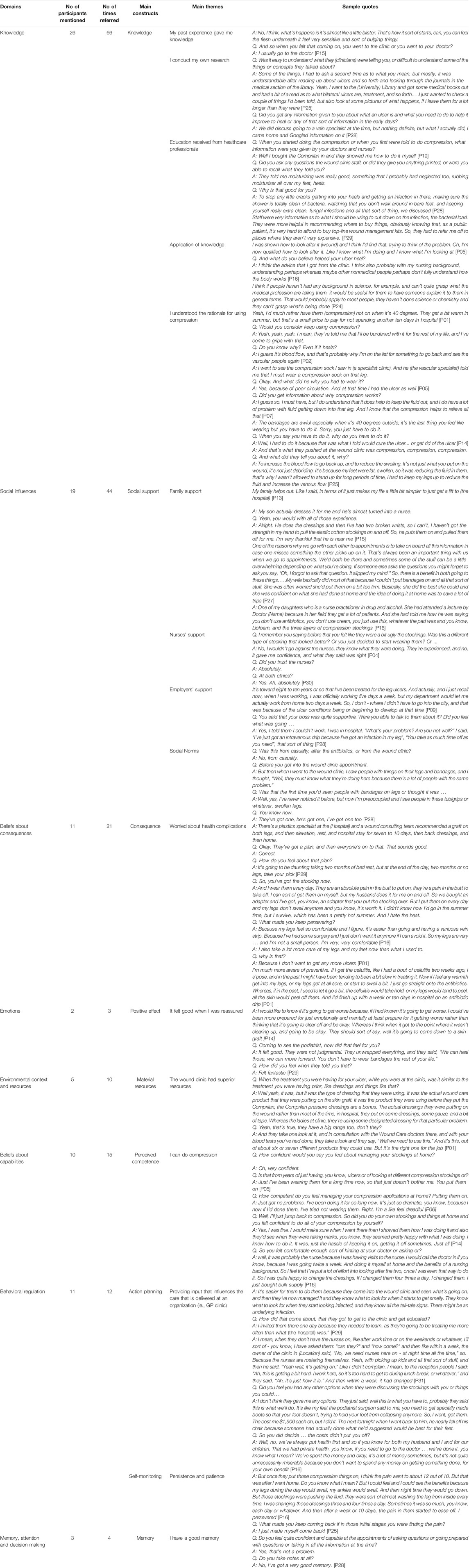

Patients described the key aspects of VLU treatment process, including compression, appointment attendance, health information, leg elevation and nutrition. Of these, compression was the most frequently discussed recommendation: 64 times by 30 participants (Figure 1). The discussed barriers and enablers (Figures 2, 3) to treatment adherence discussed by participants related to the following domains: Knowledge (referred 98 times by 96% of participants), Social Influences (referred 88 times by 81% of participants), Beliefs about Consequences (referred 56 times by 67%), Emotions (referred 29 times by 54%), Environmental Context and Resources (referred 52 times by 54%) and Beliefs about Capabilities (referred 50 times by 64%), Behavioral Regulation (referred 24 times by 64%) and Memory, Attention and Decision Making (referred 20 times by 36%). Reinforcement, Intentions and Optimism, Skills, Goals, and Social/professional Role and Identity domains were not discussed by participants since they were not prompted to do so (Tables 3, 4).

TABLE 3. Barriers to patients’ adherence to the evidence-based guideline recommendations for venous leg ulcer management.

TABLE 4. Enablers to patients’ adherence to the evidence-based guideline recommendations for venous leg ulcer management.

Knowledge

Twenty-six participants (83%) discussed enablers that pertained to knowledge. Key themes included understanding the rationale for treatment, sources of information and ways these enablers were beneficial to treatment adherence. These included three main categories: 1) knowledge from personal experience: “Since my wounds have healed I’ve basically done everything myself. Now I know what goes on … I’ve learnt little bit and pieces” [P11]; 2) information provided by a healthcare professional: “Staff were very informative as to what I should be using to cut down on the infection, the bacterial load.” [P29]; and 3) information from personal search: “I went to a University Library and got some medical books out and had a bit of a read as to what bilateral ulcers are, treatment, and so forth” [P25]. Eighteen participants said that they used Internet to get information on VLUs, while thirteen acknowledged that they relied only on information provided by clinicians as the most trustable source of information. A few participants had limited information technology skills, and perceived this as a barrier to getting information via the Internet.

Twenty-one participants (67%) reported they understood the reason for compression: “I do understand that it does help to keep the fluid out, and I do have a lot of problem with fluid getting down into that leg. And I know that the compression helps to relieve all that” [P07]. For example, one of the participants said that this understanding allowed them to accept compression as a necessary treatment: “I’ll be burdened with it for the rest of my life, and I’ve come to grips with that” [P02].

Knowledge and acceptance optimized participants’ adherence with compression. P13 outlined his acceptance to wear compression for a past health condition and understood the benefit.

I’ve had to use compression stockings in the past for different reasons, including just general swelling in my feet and ankles. So, when they mentioned compression I obviously knew what they were talking about … It’s just when you understand how the venous ulcers work then it like obvious … To me it was like this is probably the best way to heal it. So, they didn’t really have to sell it to me [P13].

Understanding how compression aided healing was a key enabler for participants when deciding whether to adhere to clinician’s treatment suggestions:

Q: And what made you decide to use the compression? A: Well it was the desire of the medicos to increase the vascular flow. The valves are leaking in the veins, that unfortunately prevents all your blood returning to your heart. So, they put the compression on to force the blood back up, as much as possible [P24].

Conversely, participants reported that complex, inconsistent or incorrect information provided by clinicians all served as barriers to VLU treatment. Compression, for example, was a particular area where participants reported confusion. Participants highlighted that sometimes this confusion originated from the clinician who was treating their wound: “I don’t really think the GP (General Practitioner) knew that much about ulcers” [P14]. Participants said they did not conduct research of their own and instead relied on qualified health professionals: “If they said jump, I jumped” [P16]. As such, when P17 was asked why they stopped wearing compression, they reported that it was because they had been told by a vascular surgeon that it was no longer necessary.

When asked about whether there was information or follow up provided about long term prophylactic compression to prevent future ulceration, P17 reported that she’d assumed she didn’t need compression because she was now able to exercise: “Well, the next thing was to go on my walking program, so I just thought that’s the price to pay for not having compression stockings? Because she (clinician) said, to develop the muscles, to strengthen the muscles in my legs, to help your circulation. I just assumed that’s why I didn’t need compression stockings.”

When participants felt that they understood treatment, they were able to troubleshoot barriers. For example, P20 said that the initial stockings suggested by her GP caused her a lot of discomfort. When she went to the wound clinic, however, they provided her with education and explored methods that would prevent the discomfort, leading to compression adherence:

When I first got the compression stocking and the first ulcer healed, I stopped wearing it because it used to rub a bit on my leg. But since the second one, I haven't stopped wearing it. Because when I went back and they said: “Well, you should be wearing it” I said “Well it rubs!” Apparently, I wasn’t told, I was supposed to have something done to it so it wouldn’t rub... just putting it on the leg. So, the second lot of nurses were more informative than the first [P20].

One participant explained that though they understood that clinics were busy, they really appreciated when they were given VLU education: “I know they’re really busy as they are; and I understand that. I think it probably would have helped, if they had explained it a little bit more as to what was actually happening … ” [P14].

Social Influences

Participants discussed social influences as an enabler to adhering to treatment plans under the TDF constructs social support and social norms. Participants reported improved adherence when they saw other people in the wound clinic undergoing similar treatment: “when I went to the wound clinic, I saw people with things on their legs and bandages, and I thought, “Well, they must know what they’re doing here because there’s a lot of people with the same problem” [P28]. This quote could also be interpreted as an expression of trust in health professionals.

Social support was a very important enabler to accessing VLU care. Family members were highlighted as the key members providing social support. The following caregiving activities increased patients’ adherence with the VLU treatment recommendations: assistance with dressing or/and compression application; assistance with computer technology to access health information; explanation of medical information and terminology; taking to medical appointments; helping to make treatment decisions; and encouraging treatment. Social support was also provided by formal carers and (community) nurses who visited patients at home. Participants also relied on supportive work-related environment with employees providing flexible arrangements for the patients to attended frequent medical appointments.

Some participants raised body image concerns related to wearing compression: “Out of vanity, I don’t like wearing (compression)—I don't like having one thing on my legs. I look like a— yeah, it’s self—a self-conscious thing, I suppose you call it” [P25]. One participant acknowledged health professionals’ support, including related to the body image issues: “I said to him, “How am I going to work at a shopping centre with a big, fat thing like this on my leg?” He said, “I was dealing with a lady that sells fur coats in the top end of (Street name), and she could manage it, so you can too” [P28].

Beliefs About Consequences

Understanding the benefits of treatment and consequences for non-adherence were the key factors driving participants’ adherence. In particular, understanding the consequences of not using compression was an important factor influencing participants’ adherence. Participants reported a belief that failure to act quickly would cause their condition to worsen. Those who experienced VLU for the first time explained that they sought out medical advice because they could see that their wound was getting worse, and they feared that an inaction or a delay would lead to serious health consequences: “I have to look for a solution because it’s not getting any better, it’s getting worse”, and you become quite desperate” [P28].

Participants who had experience with VLUs before, knew that VLUs were difficult to heal, necessitating prompt action:

A: I had it (a VLU) when I was 30, so I knew what it was, and—yeah, I wanted to get on top of it as quickly as I could, so. Q: The one that you had when you were 30, what was that one like? A: Yeah, that lasted—ah, for three years. It was terrible. Because I went to GPs over and over and over, and getting dressings and all that sort of stuff [P31].

Another participant commented that they were very meticulous with following self-care instructions provided by their healthcare practitioner; driven by fear that they will develop multiple ulcers: “I’m better now, because I don’t want to get them [VLUs] again, I worry more about what I do. I don’t touch my legs, if they’re feeling puffy, I put them up” [P25].

Emotions

Participants described a range of emotions that influenced VLU treatment adherence. These ranged from feeling daunted or overwhelmed by their diagnosis; to feeling desperate and distressed as their VLU worsened: “I got desperate” [24]. One participant explained that she was very concerned by her wound: “I started to get really concerned, and I thought, ‘I have to look for a solution because it’s not getting any better, it’s getting worse’, and you become quite desperate because your legs have to hold you, and I was terrified someone was going to hit me or bump me.” [P28]. Pain also made participants feel distressed: “I talked about my pain … I couldn’t function before. I was probably yelling at (Name) a lot and was just grumpy, full stop. But once I got that on, I could actually do stuff, I could go places and enjoy life a bit more. It is pretty depressing being in so much pain [P25].

Environmental Context and Resources

Patients reported a number of environmental and financial issues that interfered with VLU management. Transport related issues, such as living a distance from their local practice and/or limited parking spaces were discussed by eight participants: “It is quite a problem getting from here to (the clinic) by public transport” [P12]. Proximity and ability to meet appointment times greatly impacted on the patient’s ability to attend their scheduled appointments. For example, P31 found that he was unable to continue working due to the barriers imposed by managing his wound as his appointments were so frequent, time consuming and disruptive. Other barriers under this domain included hot weather and related discomfort when wearing compression on hot days: “Well, the bad points are that it’s constrictive, and it’s hot in the summer when you’re trying to get to sleep is hard.” [P02].

Lastly financial issues related to VLU management were discussed by all patients. They were related to absence from work due to medical appointments, the cost of transport and parking, and the out of pocket cost of compression hosiery and adjunct therapies: “There’s no comparison of the Comprilan in terms of getting compression. They sell it for like 70 bucks a pair as well. They’re so expensive” [P19].

Beliefs About Capabilities

Participants reported that agency to perform wound care, especially compression, was an enabler to self-care. Some participants were unable to adhere to evidence-based interventions due to limited mobility and physical constraints:

Q: Would you say that your immobility prevents you from doing any sort of exercise or anything that the GP might … (have recommended)?

A: It inhibits that, yes. I’ve got to use crutches, and sometimes I get a bit worn under the arms and so forth. Over the last six months, they’ve recommended that I elevate my leg during the day. So, it’s complicated, because I can only get on and off the bed when there’s a carer present with me. I can’t get either on or off myself, and so I have some limited funds to have carers, and I have them seven days a week, but for two or three hours at a time [P09].

Nine participants reported they could apply compression and wound dressings on their own at home. P19 (Table 4) explained that he was shown how to perform compression and change wound dressings at home. Being capable to perform these procedures on his own, he was not required to attend the clinic as frequently. Other participants also reported beliefs about one’s own capabilities was an enabler for adherence to management plans.

Behavioral Regulation

Participants discussed behaviors that related to their behavioral regulation, under the constructs Generating Alternatives and Self-monitoring. For example, one participant who was in full-time employment had made a request at their primary care to have nurses available afterhours, who would change dressings and apply compression. This example of generating alternatives, meant that participants found it easier to adhere to VLU management and meet their care plan.

Five participants discussed the importance of patience and persistence. For example, when P16 was asked why she persevered with her frequent dressings and compression, she described that though her wound was “a nuisance” and “a frustration,” she was “determined to stick it out.” Furthermore, participants could see the link between persisting with treatment, and subsequent wound healing:

Q: What do you think made your ulcer heal? Or what do you think helped it the most?

A: Well, I think that silver stuff you put on it, I think that's a great thing. I think persistence, and actually doing as I was told with it, to be perfectly honest [P30].

Though care tasks were identified as being arduous, participants believed their wound would heal faster when they demonstrated resilience.

Memory, Attention, and Decision-Making

Older participants reported barriers that pertained to memory, attention and decision making. They found it difficult to recall aspects of their care and VLU management. They forgot who has made their VLU diagnosis, if diagnostic imaging was performed in the initial consultation and what information was provided: “I can’t remember getting any paperwork, but that doesn’t mean anything. I could have reams of it in a place somewhere at home.”—[P30]. The latter presents a barrier for patients to perform self-management of their VLU. When they are unable to recall the specifics of their treatment plan (or the rationale for doing so) then they may be less likely to comply with their care directives.

Some people found it difficult to remember to keep their legs elevated. For example, after explaining key details of needing to elevate her leg, P30 explained that they frequently forgot to do this:

A: (General practitioner) explains “You’re supposed to have your legs up all the time,” but I can’t—I wouldn’t say no … The answer would be yes, but I don’t do it.

Q: Why is that?

A: I don ’t know. I just don’t think of it, I suppose [P30].

One participant described that they often had many self-care tasks prescribed to them that were often monotonous, and thus they found their attention was not directed to their self-care:

I guess, sometimes, when you’re getting ready for bed, if you’re tired and you’ve got about four or five things to do, they seem monotonous. Then I’ll get to bed and, if you are really tired, that seems like a load on your mind. But other times, you might say get them over and done with; and it’s all over in about five minutes [P27].

This participant indicated that a sense of persistence was important for overcoming the feeling of burdensome monotony associated with self-care.

Discussion

We analyzed patients’ experiences, with the aim of identifying the barriers and enablers influencing patients’ adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment recommendations in primary care settings. There is a paucity in the literature examining strategies to enhance health-promoting behaviors in patients with venous disease (Miller et al., 2014). Through utilizing the TDF, however, researchers can explain factors that influence patient adherence or non-adherence to VLU treatment. In this article, we specifically examined patient adherence to the main components of their venous leg ulcer management plan, including compression use, leg elevation, nutrition and exercise. In addition, patients also discussed their experience in scheduling and attending appointments—a key aspect of achieving optimal outcomes for their VLU. Compression adherence was of particular importance, given that current literature reflects that adherence to compression use on daily basis is as low as 28% (Atkin, 2019). We found that the most frequently discussed domains related to VLU patients’ adherence to VLU management plans included Knowledge, Social Influences, Beliefs about Consequences, Emotions, Environmental Context and Resources, Beliefs about Capabilities, Behavioral Regulation and Memory Attention and Decision Making (Tables 3, 4).

Participants often did not understand the significance of continued use of compression; and discontinued compression once healed. This is unsurprizing, as the particular age demographic in our study (older adults) often prefer to acquire health information from a GP or other clinicians (Turner et al., 2018) rather than engage in self-directed inquiry through the use of the Internet (Chaudhuri et al., 2013). A few participants received either incorrect or inconsistent information from their clinicians (a nurse, a doctor and a vascular surgeon) in this regard. In some instances, participants did not get any health information on VLU management at all. This most certainly appears to be a missed opportunity for clinicians to build patients’ agency and provide an opportunity for shared decision making (Weller et al., 2021). Previous studies have examined the relationship between the delivery of health information, the development of greater patient health literacy and improved adherence to health-promoting behaviors (Miller et al., 2014). This is consistent with our findings, as participants explained that once they understood the reason for their treatment, they were more motivated to adhere to treatment (Please refer to Figure 4 for this and other suggestions on how to improve VLU treatment adherence). The proposed topics for health education may include the discussion of the main barriers to wearing compression therapy, body image issues, family support, and consequences of not wearing compression. It is pivotal that a GP, who first diagnoses a patient with a VLU, and the nurse, who changes dressings and applies compression provide a thorough assessment during consultation to empower patients to seek further information.

Other barriers to adherence to the VLU management plans include uncontrolled pain or discomfort; body image issues pertaining to societal norms, inadequate social support and competing commitments. These multiple factors need to be considered in order to change patients’ behavior and improve their adherence to VLU treatment. Fostering a communicative and transparent clinician-patient relationship has been found to be mutually beneficial (Janamian et al., 2016). Clinicians may benefit from feedback on adherence interventions that are most impactful for the patients. Patients benefit from the opportunity having their opinions and experiences considered, and to be able to troubleshoot issues that impede VLU treatment adherence, particularly their adherence to compression (Castro et al., 2016). A patient centred approach may serve to improve the evidence-practice gap in VLU management that exists across primary care (Weller et al., 2020; Weller et al., 2020). A recent study determined that patient centred care in the management of chronic wounds led to greater patient satisfaction, increased patient knowledge, enhanced patients’ adherence to VLU management, and improved quality of life (Gethin et al., 2020). Further research into the role of clinicians in VLU patient centred care may be warranted; as would identifying suitable strategies to foster engagement of patients in research and policy development (Weller et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Our article demonstrates the value in exploring the patient experience of adhering to evidence-based treatment of VLU. Though patient non-adherence has been described as challenging for clinicians, the issue is multifaceted and complex. There is a need to further explore factors that influence VLU patients’ behaviors and provide an opportunity to plan interventions that best support both patients and clinicians in a shared decision-making capacity. The findings from this article will be relevant to clinicians involved in management of patients with venous leg ulcers, as their support is crucial to patients’ treatment adherence. Consultation with patients about VLU treatment adherence is an opportunity for clinical practice to be targeted and collaborative. This process may inform guideline development.

Adequacy of the Selected Theory

The applied TDF (Atkins et al., 2017) was a useful approach to providing a theory-driven analysis to identify barriers and enablers to patients’ adherence to VLU treatment. The identified target behaviors of VLU patients may help to inform future implementation strategies in primary care settings (Phillips et al., 2015). However, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Qualitative approach, including theory-driven analysis aiming to identify barriers and enablers is frequently used in behavior change and implementation research. It is important note that researchers applying this approach may easily overlook the attribution of behavior (Sabini et al., 2001) or failure to behave as expected or prescribed, which may influence trustworthiness (Elo et al., 2014). Consideration should always be given to the attitude-behavior or intention-behavior gap (Godin et al., 2005).

In this study, some of the participants have mentioned that they have complete trust to their clinicians and health information they provide, nevertheless they did not follow their recommendations once compression was prescribed. Further, the participants discussed various factors that they believed had influenced their adherence to treatment. For example, they discussed that they did not use compression because of the body image-related issues, discomfort during hot weather, limited understanding the benefits of wearing compression and consequences of not wearing compression, the lack of family support with wearing compression stockings, and other barriers that fit well with the TDF constructs and domains. However, most of the participants did not wear compression because it was not prescribed to them by their GP, which was a real barrier. After prolonged suboptimal treatment in primary care, which has had no effect on VLU healing, they were referred to the specialist tertiary clinic, where compression was prescribed.

It is important to note that the TDF was developed for understanding the behavior of healthcare professionals related to implementation of evidence-based guidelines in clinical practice (Michie et al., 2005). We utilized this theory to explain patients’ adherence to VLU treatment, aiming to bring patients’ perspective on VLU management and to complement our study on the use of the VLU CPG recommendations in primary health care settings located in Melbourne metropolitan and rural Victoria, Australia (Weller et al., 2020).

As we already mentioned, our interview guide consisted of open-ended questions loosely matching the TDF domains (2017 version), and did not cover all 14 TDF domains. Therefore, the collected data are largely influenced by what questions the participants were asked, limiting the “richness” of data that could have been obtained using the qualitative approach alone (Phillips et al., 2015).

The theory-driven deductive analysis itself may limit the interpretative process, leaving no space for ideas that are not related to the theoretical domains of the TDF to be elicited (McGowan et al., 2020). By using the TDF domains as first-level codes and the TDF constructs as secondary level codes there is a danger that data are forced into the codes, limiting the interpretation.

Although we quantified how often or by how many participants references are made to specific constructs and domains, it is important to note that these numbers are highly influenced by the way the interviews were conducted, e.g., we much more explicitly asked for experiences and thoughts regarding compression adherence rather than the other VLU treatment recommendations; and, this was not identical in all interviews. This, of course, is in accordance with qualitative methodology, but one of the reasons why counting how often or by how many participants references are made to has limited value.

Study Limitations and Recommendations for Research

As patients with VLUs require complex treatment, comprising a number of different evidence-based approaches, it can be expected that barriers and enablers playing an important role in the several measures differ, as what they appeal to or need, indeed, differs. In this study, we focused predominantly on patients’ adherence to compression therapy as it is the mainstay treatment identified by the VLU CPG. Future research about VLU patients’ adherence to exercise, leg elevation and nutrition recommendations would be beneficial. Further studies may also explore individual factors that influence VLU patients’ behaviors related to adherence to compression therapy. For example, VLU patients’ body image issues related to VLUs and wearing compression garments may be an area to be explored in greater depth. Studies that explore patients’ understanding the consequences of not wearing compression and not following other recommendations may also be of value to patients and clinicians to optimize healing outcomes in primary care.

We explored barriers and enablers that influence patients’ adherence to VLU treatment using a qualitative inquiry. Future studies on patient adherence to VLU treatment may identify predictors and extent of patient adherence to the VLU treatment recommendations, using validated questionnaires about patients’ adherence to health recommendations. Findings of these studies may provide information on the effectiveness of patient care management and outcomes, and identify patients with higher risk for poor adherence to inform and evaluate targeted interventions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee and participating health services ethics committees. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CW developed the study proposal and secured the grant. VT and CW designed the interview guide. CR and LT conducted the interviews. VT, CR, and CW developed coding framework. CR coded the interview transcripts. LT was responsible for project administration. All authors contributed to data analysis and article writing. CR and VT prepared the first draft. The final version was approved by all authors. VT designed the infographic.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council NHMRC APP1132444 and NHMRC APP1069329 awarded to Professor CW.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all contributors to both research projects.

References

Andriessen, A., Apelqvist, J., Mosti, G., Partsch, H., Gonska, C., and Abel, M. (2017). Compression Therapy for Venous Leg Ulcers: Risk Factors for Adverse Events and Complications, Contraindications - a Review of Present Guidelines. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 31 (9), 1562–1568. doi:10.1111/jdv.14390

Atkin, L. (2019). Venous Leg Ulcer Prevention 3: Supporting Patients to Self-Manage. Nurs. Times 115 (8), 22–26. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/long-term-conditions/venous-leg-ulcer-prevention-3-supporting-patients-to-self-manage-29-07-2019/

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O'Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., et al. (2017). A Guide to Using the Theoretical Domains Framework of Behaviour Change to Investigate Implementation Problems. Implement Sci. 12 (1), 77. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Australian Wound Management Association, New Zealand Wound Care Society (2011). Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers. Barton, ACT: Cambridge Publishing.

Barnsbee, L., Cheng, Q., Tulleners, R., Lee, X., Brain, D., and Pacella, R. (2019). Measuring Costs and Quality of Life for Venous Leg Ulcers. Int. Wound J. 16 (1), 112–121. doi:10.1111/iwj.13000

Boxall, S., Carville, K., Leslie, G., and Jansen, S. (2019). Compression Bandaging: Identification of Factors Contributing to Non-concordance. Wpr 27 (1), 6–20. doi:10.33235/wpr.27.1.6-20

Brooks, J., Ersser, S. J., Lloyd, A., and Ryan, T. J. (2004). Nurse-led Education Sets Out to Improve Patient Concordance and Prevent Recurrence of Leg Ulcers. J. Wound Care 13 (3), 111–116. doi:10.12968/jowc.2004.13.3.26585

Bui, U. T., Finlayson, K., and Edwards, H. (2019). The Diagnosis of Infection in Chronic Leg Ulcers: A Narrative Review on Clinical Practice. Int. Wound J. 16 (3), 601–620. doi:10.1111/iwj.13069

Castro, E. M., Van Regenmortel, T., Vanhaecht, K., Sermeus, W., and Van Hecke, A. (2016). Patient Empowerment, Patient Participation and Patient-Centeredness in Hospital Care: A Concept Analysis Based on a Literature Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 99 (12), 1923–1939. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026

Chaudhuri, S., Le, T., White, C., Thompson, H., and Demiris, G. (2013). Examining Health Information-Seeking Behaviors of Older Adults. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 31 (11), 547–553. doi:10.1097/01.ncn.0000432131.92020.42

Domingues, E. A. R., Kaizer, U. A. O., and Lima, M. H. M. (2018). Effectiveness of the Strategies of an Orientation Programme for the Lifestyle and Wound-Healing Process in Patients with Venous Ulcer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. Wound J. 15 (5), 798–806. doi:10.1111/iwj.12930

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., and Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 4 (1), 2158244014522633. doi:10.1177/2158244014522633

Finlayson, K. J., Parker, C. N., Miller, C., Gibb, M., Kapp, S., Ogrin, R., et al. (2018). Predicting the Likelihood of Venous Leg Ulcer Recurrence: The Diagnostic Accuracy of a Newly Developed Risk Assessment Tool. Int. Wound J. 15 (5), 686–694. doi:10.1111/iwj.12911

Franks, P. J., Barker, J., Collier, M., Gethin, G., Haesler, E., Jawien, A., et al. (2016). Management of Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers: Challenges and Current Best Practice. J. Wound Care 25 (Suppl. 6), S1–S67. doi:10.12968/jowc.2016.25.sup6.s1

Gethin, G., Probst, S., Stryja, J., Christiansen, N., and Price, P. (2020). Evidence for Person-Centred Care in Chronic Wound Care: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Practice. J. Wound Care 29 (Suppl. 9b), S1–S22. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.sup9b.s1

Godin, G., Conner, M., and Sheeran, P. (2005). Bridging the Intention-Behaviour 'gap': the Role of Moral Norm. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 44 (Pt 4), 497–512. doi:10.1348/014466604x17452

Graves, N., and Zheng, H. (2014a). Modelling the Direct Health Care Costs of Chronic Wounds in Australia. Wound Pract. Res. 22 (120-4), 6–33. doi:10.3316/informit.272218893716909

Graves, N., and Zheng, H. (2014n). The Prevalence and Incidence of Chronic Wounds: A Literature Review. Wound Pract. Res. 22 (1), 4–19. doi:10.3316/informit.272162994803134

Guest, J. F., Ayoub, N., McIlwraith, T., Uchegbu, I., Gerrish, A., Weidlich, D., et al. (2017). Health Economic burden that Different Wound Types Impose on the UK's National Health Service. Int. Wound J. 14 (2), 322–330. doi:10.1111/iwj.12603

Guest, J. F., Fuller, G. W., and Vowden, P. (2018). Venous Leg Ulcer Management in Clinical Practice in the UK: Costs and Outcomes. Int. Wound J. 15 (1), 29–37. doi:10.1111/iwj.12814

Haardörfer, R. (2019). Taking Quantitative Data Analysis Out of the Positivist Era: Calling for Theory-Driven Data-Informed Analysis. Health Educ. Behav. 46 (4), 537–540. doi:10.1177/1090198119853536

Janamian, T., Crossland, L., and Wells, L. (2016). On the Road to Value Co‐creation in Health Care: the Role of Consumers in Defining the Destination, Planning the Journey and Sharing the Drive. Med. J. Aust. 204 (S7), S12–S4. doi:10.5694/mja16.00123

Jull, A. B., Mitchell, N., Aroll, J., Jones, M., Waters, J., Latta, A., et al. (2004). Factors Influencing Concordance with Compression Stockings after Venous Leg Ulcer Healing. J. Wound Care 13 (3), 90–92. doi:10.12968/jowc.2004.13.3.26590

Kelechi, T. J., Mueller, M., Spencer, C., Rinard, B., and Loftis, G. (2014). The Effect of a Nurse-Directed Intervention to Reduce Pain and Improve Behavioral and Physical Outcomes in Patients with Critically Colonized/infected Chronic Leg Ulcers. J. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 41 (2), 111–121. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000009

KPMG (2013). An Economic Evaluation of Compression Therapy for Venous Leg Ulcers. Australian Wound Management Association. Canberra: KPMG at the request of the Australian Wound Management Association.

Leren, L., Johansen, E., Eide, H., Falk, R. S., Juvet, L. K., and Ljoså, T. M. (2020). Pain in Persons with Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Int. Wound J. 17 (2), 466–484. doi:10.1111/iwj.13296

Lurie, F., Passman, M., Meisner, M., Dalsing, M., Masuda, E., Welch, H., et al. (2020). The 2020 Update of the CEAP Classification System and Reporting Standards. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphatic Disord. 8 (3), 342–352. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.12.075

Mallick, S., Sarkar, T., Gayen, T., Naskar, B., Datta, A., and Sarkar, S. (2020). Correlation of Venous Clinical Severity Score and Venous Disability Score with Dermatology Life Quality index in Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Indian J. Dermatol. 65 (6), 489–494. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_485_20

McGowan, L. J., Powell, R., and French, D. P. (2020). How Can Use of the Theoretical Domains Framework Be Optimized in Qualitative Research? A Rapid Systematic Review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 25 (3), 677–694. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12437

Meulendijks, A. M., Franssen, W. M. A., Schoonhoven, L., and Neumann, H. A. M. (2019). A Scoping Review on Chronic Venous Disease and the Development of a Venous Leg Ulcer: The Role of Obesity and Mobility. J. Tissue Viability 29 (3), 190–196. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2019.10.002

Meulendijks, A. M., Welbie, M., Tjin, E. P. M., Schoonhoven, L., and Neumann, H. A. M. (2020). A Qualitative Study on the Patient's Narrative in the Progression of Chronic Venous Disease into a First Venous Leg Ulcer: a Series of Events. Br. J. Dermatol. 183 (2), 332–339. doi:10.1111/bjd.18640

Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., and Walker, A. (2005). Making Psychological Theory Useful for Implementing Evidence Based Practice: A Consensus Approach. Qual. Saf. Health Care 14 (1), 26–33. doi:10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

Miller, C., Kapp, S., and Donohue, L. (2014). Examining Factors that Influence the Adoption of Health-Promoting Behaviours Among People with Venous Disease. Int. Wound J. 11 (2), 138–146. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481x.2012.01050.x

Nussbaum, S. R., Carter, M. J., Fife, C. E., DaVanzo, J., Haught, R., Nusgart, M., et al. (2018). An Economic Evaluation of the Impact, Cost, and Medicare Policy Implications of Chronic Nonhealing Wounds. Value in Health 21 (1), 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.007

O'Meara, S., Cullum, N., Nelson, E. A., and Dumville, J. C. (2013). Compression for Venous Leg Ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, CD000265. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000265.pub3

Pacella, R., Tulleners, R., Cheng, Q., Burkett, E., Edwards, H. S. Y., et al. (2018). Solutions to the Chronic Wounds Problem in Australia: A Call to Action. Wound Pract. Res. 26 (2), 84–98. doi:10.3316/informit.733666000861426

Phillips, C. J., Marshall, A. P., Chaves, N. J., Jankelowitz, S. K., Lin, I. B., Loy, C. T., et al. (2015). Experiences of Using the Theoretical Domains Framework across Diverse Clinical Environments: A Qualitative Study. J. Multidiscip Healthc. 8, 139–146. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S78458

Presseau, J., McCleary, N., Lorencatto, F., Patey, A. M., Grimshaw, J. M., and Francis, J. J. (2019). Action, Actor, Context, Target, Time (AACTT): A Framework for Specifying Behaviour. Implement Sci. 14 (1), 102. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0951-x

Probst, S., Allet, L., Depeyre, J., Colin, S., and Skinner, M. B. (2019). A Targeted Interprofessional Educational Intervention to Address Therapeutic Adherence of Venous Leg Ulcer Persons (TIEIVLU): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 20 (1), 243. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3333-4

Probst, S., Séchaud, L., Bobbink, P., Skinner, M. B., and Weller, C. D. (2020). The Lived Experience of Recurrence Prevention in Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers: An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. J. Tissue Viability 29 (3), 176–179. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2020.01.001

Reich-Schupke, S., Doerler, M., Wollina, U., Dissemond, J., Horn, T., Strölin, A., et al. (2015). Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers. Data of the German Marjolin Registry and Review. JDDG: J. der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 13 (10), 1006–1013. doi:10.1111/ddg.12649

Ritchie, G., and Taylor, H. (2018). Understanding Compression: Part 2 - Holistic Assessment and Clinical Decision-Making in Leg Ulcer Management. J. Community Nurs. 32 (3), 22–29. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Understanding-compression-%3A-part-2-%E2%80%94-holistic-and-Ritchie-Taylor/1b601612434de81974753ebd27111056c3fb0330

Sabini, J., Siepmann, M., and Stein, J. (2001). Target Article: "The Really Fundamental Attribution Error in Social Psychological Research". Psychol. Inq. 12 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1201_01

Shanley, E., Moore, Z., Patton, D., O’Connor, T., Nugent, L., Budri, A. M., et al. (2020). Patient Education for Preventing Recurrence of Venous Leg Ulcers: A Systematic Review. J. Wound Care 29 (2), 79–91. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.2.79

Turner, A. M., Osterhage, K. P., Taylor, J. O., Hartzler, A. L., and Demiris, G. (2018). A Closer Look at Health Information Seeking by Older Adults and Involved Family and Friends: Design Considerations for Health Information Technologies. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 1036–1045. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6371280/

Walburn, J., Weinman, J., Norton, S., Hankins, M., Dawe, K., Banjoko, B., et al. (2017). Stress, Illness Perceptions, Behaviors, and Healing in Venous Leg Ulcers: Findings from a Prospective Observational Study. Psychosom Med. 79 (5), 585–592. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000436

Weller, C., and Evans, S. (2014). Monitoring Patterns and Quality of Care for People Diagnosed with Venous Leg Ulcers: The Argument for a National Venous Leg Ulcer Registry. Wound Pract. Res. 22 (2), 68–73. doi:10.3316/informit.376731229504153

Weller, C., Richards, C., Turnour, L., Green, S., and Team, V. (2019). Vascular Assessment in Venous Leg Ulcer Diagnostics and Management in Australian Primary Care: Clinician Experiences. J. Tissue Viability 29 (3), 184–189. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2019.12.005

Weller, C., Team, V., Ivory, J., Crawford, K., and Gethin, G. (2018). ABPI Reporting and Compression Recommendations in Global Clinical Practice Guidelines on Venous Leg Ulcer Management: A Scoping Review. Int. Wound J. 15 (1), 53–61. doi:10.1111/iwj.13048

Weller, C. D., Barker, A., Darby, I., Haines, T., Underwood, M., Ward, S., et al. (2016). Aspirin in Venous Leg Ulcer Study (ASPiVLU): Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Trials 17, 192. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1314-4

Weller, C. D., Buchbinder, R., and Johnston, R. V. (2016). Interventions for Helping People Adhere to Compression Treatments for Venous Leg Ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD008378. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008378.pub3

Weller, C. D., Bouguettaya, A., Britt, H., and Harrison, C. (2020). Management of People with Venous Leg Ulcers by Australian General Practitioners: An Analysis of the National Patient‐encounter Data. Wound Rep. Reg. 28 (4), 553–560. doi:10.1111/wrr.12820

Weller, C. D., Richards, C., Turnour, L., Patey, A. M., Russell, G., and Team, V. (2020). Barriers and Enablers to the Use of Venous Leg Ulcer Clinical Practice Guidelines in Australian Primary Care: A Qualitative Study Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 103, 103503. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103503

Weller, C. D., Richards, C., Turnour, L., and Team, V. (2020). Rationale for Participation in Venous Leg Ulcer Clinical Research: Patient Interview Study. Int. Wound J. 17 (6), 1624–1633. doi:10.1111/iwj.13438

Weller, C. D., Richards, C., Turnour, L., and Team, V. (2020). Understanding Factors Influencing Venous Leg Ulcer Guideline Implementation in Australian Primary Care. Int. Wound J. 17 (3), 804–818. doi:10.1111/iwj.13334

Weller, C. D., Team, V., Ivory, J. D., Crawford, K., and Gethin, G. (2019). ABPI Reporting and Compression Recommendations in Global Clinical Practice Guidelines on Venous Leg Ulcer Management: A Scoping Review. Int. Wound J. 16 (2), 406–419. doi:10.1111/iwj.13048

Weller, C., Richards, C., Turnour, L., and Team, V. (2021). Venous Leg Ulcer Management in Australian Primary Care: Patient and Clinician Perspectives. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 113, 103774. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103774

Keywords: venous leg ulcer, patient experience, evidence-based guidelines, Theoretical Domains Framework, adherence—compliance—persistance

Citation: Weller CD, Richards C, Turnour L and Team V (2021) Patient Explanation of Adherence and Non-Adherence to Venous Leg Ulcer Treatment: A Qualitative Study. Front. Pharmacol. 12:663570. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.663570

Received: 03 February 2021; Accepted: 19 May 2021;

Published: 03 June 2021.

Edited by:

Luciane Cruz Lopes, University of Sorocaba, BrazilReviewed by:

Tanja Mueller, University of Strathclyde, United KingdomKata Mazalin, MD, Servier, Hungary

Maria Grypdonck, Ghent University, Belgium

Copyright © 2021 Weller, Richards, Turnour and Team. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolina D. Weller, carolina.weller@monash.edu

Carolina D. Weller

Carolina D. Weller Catelyn Richards

Catelyn Richards Louise Turnour

Louise Turnour Victoria Team

Victoria Team