- 1Department of Pharmacy, Cancer Institute, Phase I Clinical Trial Centre, Changsha Central Hospital Affiliated to University of South China, School of Pharmacy, University of South China, Changsha, China

- 2Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Tumor Microenvironment Responsive Drug Research, Hengyang, China

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are two typical neurodegenerative diseases that increased with aging. With the emergence of aging population, the health problem and economic burden caused by the two diseases also increase. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway regulates signal transduction and biological processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism. According to reports, it regulates neurotoxicity and mediates the survival of neurons through different substrates such as forkhead box protein Os (FoxOs), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), and caspase-9. Accumulating evidences indicate that some natural products can play a neuroprotective role by activating PI3K/AKT pathway, providing an effective resource for the discovery of potential therapeutic drugs. This article reviews the relationship between AKT signaling pathway and AD and PD, and discusses the potential natural products based on the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to treat two diseases in recent years, hoping to provide guidance and reference for this field. Further development of Chinese herbal medicine is needed to treat these two diseases.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are a kind of diseases that gradually lose the structure or function of neurons, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and so on. These diseases are characterized by progressive degeneration and neuronal necrosis, resulting in cognitive, emotional and behavioral abnormalities (Hetman et al., 2020). With the acceleration of population ages, the number of people suffering from AD and PD is increasing year by year. Up to now, the current treatment strategies of these diseases aim to alleviate symptoms and/or inhibit disease progression without radical cure, posing a serious threat to the quality of patients’ life, hence becoming a global health problem. The high cost of treatment and nursing not only brings great trouble to patients and their families, but also causes great social and economic burden (Batista and Pereira, 2016), making the development of this kind of new drugs an urgent problem in the field of medicine. In addition, abnormal injuries caused by chemotherapy drugs give rise to different degrees of impact on patients’ physical and mental health and quality of life, which have become the direct cause of dosage restriction or discontinuation of some drugs (Vaz and Silvestre, 2020). A systematic review showed that Chinese herbal medicine and its natural active ingredients are of good safety and tolerance in protecting the central nervous system injury, and so that it gets increasing attention by the medical community (Yang et al., 2017).

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signal pathway has been proved to play an important role in the central nervous system (Matsuda et al., 2019). It has been diffusely studied for its involvement in the physiological processes of central nervous system, such as cell survival, autophagy, neurogenesis, neuronal proliferation and differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. In recent years, a growing number of studies have found that many natural products based on PI3K/AKT signal pathway protect dopaminergic neurons, hippocampal neurons, cortical neurons, and inhibit the activation of microglia, thus playing a role in the prevention and treatment of AD and PD. In this paper, we obtain relevant literature through Pubmed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and other extensive databases. And we systematically summarize the related studies of natural products for the prevention and treatment of AD and PD based on PI3K/AKT signal pathway.

PI3K/AKT Signal Pathway: Overview

PI3K: The Key Component Upstream of the Pathway

PI3Ks, a family of intracellular lipid kinases, are key elements in the upstream of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. PI3Ks are divided into three classes (I-III) according to their structure and substrate selectivity. The most generally studied class I isoforms that are activated by cell surface receptors are heterodimers composed of a regulatory subunit (P85) and a catalytic subunit (P110). The amino terminus of P85 contains a Src Homology 3 (SH3) domain and two proline-rich regions, while the basal terminus contains two SH2 domains and a non-coding region that combine with P110. Besides, class I isoforms are further segmented into class IA (PI3Kα, β and δ) and class IB (PI3Kγ) based on their modes of regulation (Thorpe et al., 2015). Class IA consists of catalytic subunits p110α, β, δ and regulatory subunits p85α, β, γ. Class IB are constituted by a p110γ catalytic subunit coupled with the regulatory isoforms p101 or p87. The differences lie in the way of the activation between the two kinases. PI3Kα, β and δ are activated when extracellular ligands bind to a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) with enzyme activity, while PI3Kγ is activated by G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and Ras family GTP enzymes (Dobbin and Landen, 2013). There are three class II isoforms, PI3KC2α, 2β, 2γ, which may constitutively bind to membranes and require additional activation signals. And the single class III PI3K, vacuolar protein sorting 34 (VPS34), is significant for membrane traffic from the plasma membrane to early endosomes (Sugiyama et al., 2019).

AKT: The Core Site of the Pathway

Protein kinase B (PKB), a serine/threonine kinase, is considered as one of the most important effector kinase downstream of PI3K and the core of PI3K/AKT signal pathway. Different genes encode three highly homologous subtypes of AKT: AKT1/PKBα, AKT2/PKBβ, and AKT3/PKBγ. Each isoform contains a conserved N-terminal plekstrin homology (PH) domain, a central fragment, and a C-terminal regulatory domain (Hemmings et al., 2004). Membrane translocation in AKT activation is mediated by the PH domain, and AKT activity is weakened due to its mutation or deletion. The structure of the catalytic domain includes an ATP binding site and a threonine residue Thr308 (AKT1-Thr308, AKT2-Thr309, AKT3-Thr305), which is the necessary phosphorylation site for AKT activation. The C-terminal regulatory domain consists of 40 amino acids, holding a hydrophobic region, which containing the second phosphorylation site needed to activate AKT, namely the serine residue Ser473 (AKT1-Ser473, AKT2-Ser474, AKT3-Ser472). Although the three AKT subtypes are highly homologous, each exerts unique physiological functions. AKT1 is broadly distributed in all tissues of the body, mainly involved in cell growth, proliferation, angiogenesis and tumor cell invasiveness (Petrik et al., 2016). Found in Mammalian skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue, AKT2 are confirmed participate in cell growth and proliferation, and mediate glucose homeostasis (Garofalo et al., 2003). Relatively little is known about AKT3, it is crucial for brain development and the survival of malignant glioma cells (Ghoneum and Said, 2019).

Signal Regulation of PI3K/AKT Pathway

Activation of PI3K/AKT Pathway

The activation of PI3K/AKT pathway begins with the activation of PI3K by RTK. Numerous cytokines or growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), bind to the plasma membrane receptor RTK in response to stimulation by extracellular ligands, inducing receptor dimerization and cross-phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in intracellular domains. The regulatory subunit P85 binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine residue on the activated receptor through its SH2 domain. The catalytic subunit p110 is then recruited to form a fully active PI3K enzyme. Also, P110 subunit could be recruited independently of p85, like Ras-GTP, even other cohesive molecules as insulin receptor substrate (IRS). Besides, activation of Gα subunit could activate Src-dependent integrin signal transduction in PI3K. By unifying with the signal protein AKT and phosphatidylinositol dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) containing PH domain, Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), the second messenger phosphorylated from Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-disphosphate (PIP2) by P110, recruits inactive AKT and PDK1 from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane, thus enabling PDK1 to obtain catalytic activity. At the same time, the conformational change of AKT structure exposes the phosphorylation sites of Thr308 and Ser473, resulting the phosphorylation of Thr308 residues by PDK1 (Altomare et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2019). And the second phosphorylation at Ser473 at the carboxyl terminal is essential and mainly carried out by mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) (Zeng et al., 2007). Many other kinases are known to phosphorylate AKT at Ser473, including PDK-1, integrin-linked kinase (ILK) or ILK-related kinases, and AKT itself (Memmott and Dennis, 2009). Binding proteins such as actin, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2, heat shock protein (Hsp) 90 or Hsp27 are able to regulate the activity of AKT (Shanu and Komal, 2015). In addition, members of the family of PI3K-associated kinases, including DNA-dependent protein kinases (DNA-PK), can also phosphorylate AKT in Ser473 (Bellacosa et al., 2005).

As a downstream member of AKT, mTOR in turn acts as an activator for AKT activation. mTOR is linked to a regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), and mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8 (mLST8) to form two multiprotein complexes with different functions, namely mTORC1 and mLST8 (Soliman, 2013). mTORC2 directly phosphorylates the hydrophobic motif Ser473 of AKT, and therefore enhances the activity of AKT kinase and promotes the phosphorylation of Thr308 by PDK1 (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012).

Negative Regulation of PI3K/AKT Pathway

Tumor suppressor, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is a specific phosphatase with double activity (Satoru et al., 2018). Inactivation of AKT is mediated by the lipid phosphatase PTEN through dephosphorylation of PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2, and by Src homology domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) due to conversion of PIP3 to PIP2. Negative regulation also be done by PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) and protein phosphatase 2 A (PP2A) which in turn dephosphorylate AKT at Ser473 and Thr308 respectively (Bertacchini, 2015).

Downstream Regulation of PI3K/AKT Pathway

After phosphorylated by the upstream signal, PI3K/AKT executes diverse biological actions by phosphorylating or forming complexes for a range of downstream molecules, such as the FoxO family members, GSK-3β, mTOR, and actin-related protein, among others (Mirdamadi et al., 2017; Matsuo et al., 2018). The activation of this signaling pathway and its downstream regulation are basically illustrated in Supplementary Figures S1 or S2. mTOR is the main downstream target of PI3K/AKT signal transduction and a key regulatory factor of cellular metabolism. AKT affects cell cycle progression by phosphorylating and inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27. And it modulates apoptosis through inhibiting Bcl2-antagonist of cell death (Bad), bcl-2-like protein 11 (BIM), caspase-9 and forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1). Nuclear factor erythrocyte two related factor (Nrf2) is the main regulator of oxidative stress, which can promote the transcription of detoxification enzyme and antioxidant enzyme protein genes. Some drugs have been proved to activate PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 signaling, thereby reducing cognitive impairment and neurological dysfunction (Liang et al., 2018). In simple terms, PI3K/AKT pathway has been implicated in cell proliferation, glucose metabolism, cell survival, cell cycle, protein synthesis, and participates in neuronal morphology and plasticity through adjusting several downstream molecules. Imbalanced expression in solid tumors, immune-mediated diseases, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, nervous system diseases and other diseases, PI3K/AKT pathway arouses the interest of many scholars act as a meaningful therapeutic target, worthy of a further exploration.

Roles of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is a neurodegenerative disease positively concerned with age and associated with memory, cognitive impairment and behavioral changes (Martins et al., 2019). Two chiefly pathological features as following: senile plaque (SP) with amyloid protein (Aβ) as the core and abnormal high phosphorylation of Tau protein in brain nerve cells to form neurofibrillary tangles (NFT). With the aging of the population, the incidence of AD is increasing year by year, which brings a heavy burden to the society and families. Distinctly, the major problem facing researchers is to prevent and treat AD availably.

Although several hypotheses have been proposed after decades of research, the specific pathogenesis of AD is still obscure. The most common amyloid deposition hypothesis proposes that the self-assembly of misfolded amyloid peptides affects the structure and function of neurons, stimulates apoptosis, leading to synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration. It has been found that PI3K/AKT signal pathway is involved in the formation of two special pathological structures in AD (Do et al., 2014), so that activating the PI3K/AKT pathway may conduce to delay the progression of AD (Supplementary Figure S1). The activation of P3IK/AKT signal pathway is capable of protecting neurons against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Various targets downstream of this pathway are closely related to the occurrence and development of the disease. For example, the increase of GSK-3β activity is directly related to the increase of Aβ production and deposition, hyperphosphorylation of tau and the formation of NFT. During AKT phosphorylation, the phosphorylated protein of GSK-3β is inactivated at the Ser9 site, and therefore weakens the hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein, and inhibits the formation of NFT (Kitagishi et al., 2014).

Different from normal people, there is an evidently decrease in the number of neurons in some brain regions of AD patients. These changes were mainly caused by apoptosis induced by oxidative stress response and the excitatory toxicity of glutamate, and eventually lead to the occurrence of nervous system diseases. Studies have shown that cell death in AD is related to the changes in the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL), which play an anti-apoptotic role by stabilizing the permeability of mitochondrial membrane and preventing the release of mitochondrial cytochrome C. Interestingly, the Pl3K/AKT signaling pathway can regulate the expression of mitochondrial membrane permeability protein Bcl-2, Bax and other proteins (Zeng et al., 2011). Other studies have shown that the repression of PI3K/AKT induces neuronal apoptosis through the mediation of P38 activation. In addition, overexpression of PTEN associated with the apoptosis, and the survival or death of neuronal cells may be partly attributed to the variations in PTEN expression (Satoru et al., 2018). Accordingly, the down-regulation of PTEN to promote the activation of AKT might be of great significance in maintaining its neuroprotective effects.

What else, synaptic plasticity of neurons could be adjusted by the PI3K/AKT pathway. In the animal model of AD, inhibition of PTEN is beneficial for preserving normal synaptic function and thereby improving cognition (Cui et al., 2017b). Some studies have confirmed that mTOR protein pathway in PI3K/AKT signaling is also involved in the development of neuronal dendrites and the formation of dendritic spines. The increase in synaptic plasticity is charac terized by long term potentiation (LTP) (Shane et al., 2019), which requires the activation of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, thereby promoting the insertion of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolpropionic acid (AMPA) receptors into the postsynaptic membrane. On the one hand, mTOR increases the expression of LTP-related proteins, and PI3K also binds to AMPA receptors and guides its distribution on the membrane (Parkinson and Hanley, 2018). On the other hand, NMDA receptor activation also promotes PI3K activation. In addition, AKT immobilizes phosphatidylinositol (PI) to the postsynaptic membrane to recruit the docking protein of AMPA receptor and promote the fixation of AMPA receptor in the postsynaptic membrane (Spinelli et al., 2019). As a result, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway regulates neuronal synaptic plasticity at multiple nodes.

Roles of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Parkinson’s Disease

PD is the second largest neurodegenerative disease after AD, also known as idiopathic tremor paralysis. It is characterized by the degeneration and deletion of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra (SN) and the formation of eosinophilic inclusion body (Lewy bodies, LBs), as well as the production of neuroinflammation. For decades, though, there has been a great deal of research on PD, drugs on effectively inhibiting or reversing the development of PD are still an assumption except the treatment of temporary improvement of symptoms, so the treatment of PD is more difficult than it seems. As for the pathogenesis of PD, scientists have successively proposed hypotheses including oxidative stress mitochondrial damage, excitatory amino acid toxicity, inflammatory response, and abnormal deposition of α synuclein. However, most of the pathogenic factors have not been confirmed. At present, the abnormal aggregation of fibrillation and α-synuclein is considered to be the key factor for the cascade of pathological events in PD. LBs is mainly composed of misfolded proteins, such as synuclein, tubulin, and amyloid precursor protein. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) like AKT/ERK, found in cells, participate in the removal of these proteins through phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Intracellular deposition of alpha synuclein leads to neuronal degeneration and apoptosis. Autophagy degrade synuclein and resist the deposition of synuclein in Lewy, so it is usually increased in PD patients (Chen et al., 2017).

The loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SN and striatum caused by apoptosis is an important cause of PD. Scholars manifested that AKT and phosphorylated AKT are significantly reduced in the substantia nigra compacta (SNpc) of PD patients (Luo et al., 2019). GSK-3 is widely expressed in the central nervous system, but abnormally in PD (Zhang et al., 2016b). Caspase-3 plays a key role in apoptosis and as a key effector in all apoptosis pathways. During the pathogenesis of PD, GSK-3 activation up-regulates the content of caspase-3 in the dopaminergic nerve, leading the apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons. Experiments show that AKT could inhibit the activity of GSK-3 by phosphorylating Ser21 of GSK-3α or Ser9 of GSK-3β (Liying et al., 2018). As a downstream pathway of AKT, IKK/IκBα/NF-κB pathway is one of the vital pathways for cell survival (Yan et al., 2019). Consequently, the activation of PI3K/AKT pathway facilitates the survival and growth of dopamine neurons by inhibiting apoptosis. Besides, knockout of PTEN make a contribution to neuroprotection and promotion of the rapid growth of dopaminergic (DA) neurons (Wang et al., 2017).

Oxidative stress, inducing neuronal cell death and apoptosis through intracellular calcium overload lipid peroxidation DNA damage and excitatory toxicity, also contributes to the onset of PD. The PI3K/AKT pathway influences oxidative stress by modulating downstream molecular targets such as GSK-3, mTOR and FoxO3a. Decreasing the mTOR activity may lead to neurodegeneration. The stress response protein regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1 (REDD1) is up-regulated in dopaminergic neurons in PD patients and can modulate the activity of mTOR (Chong et al., 2012). When Parkin (a mutation-prone gene associated with PD) is abnormally expressed, the PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a pathway is blocked, resulting in the imbalance of oxidative stress and ultimately the occurrence of PD (Gong et al., 2018). Additionally the relationship between the above mentioned PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and PD is clearly sorted out in Supplementary Figure S2.

Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease Based on PI3K/AKT Pathawy

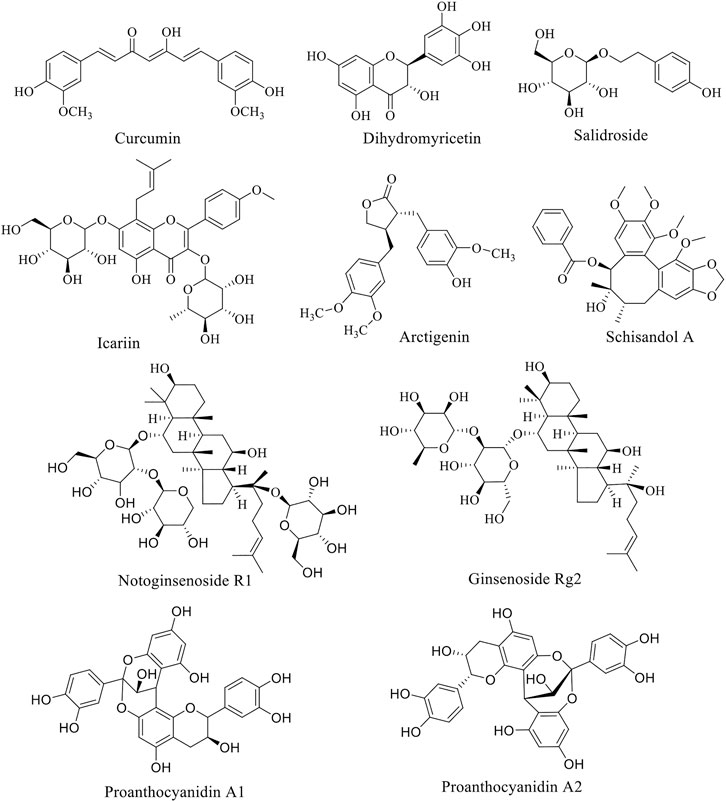

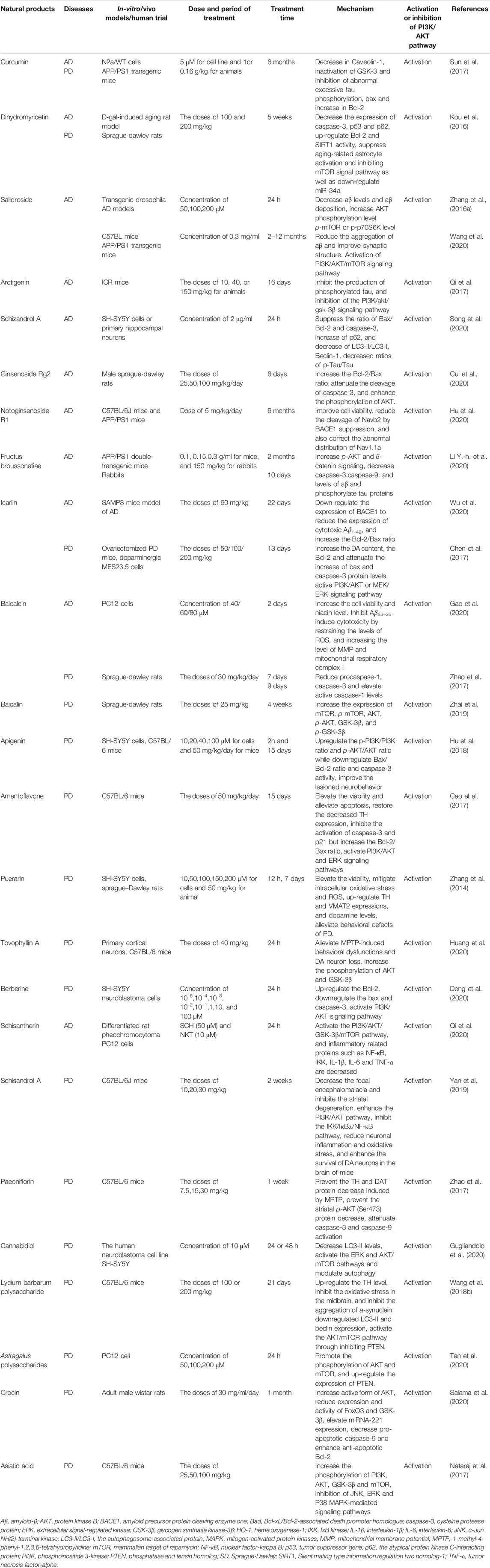

Natural products have attracted the attention of researchers by virtue of their natural advantages such as wide variety, wide source and wide function spectrum. Structurally classified into flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, glycosides, and others, natural products are widely distributed in nature and commonly found in herbs, fruits and vegetables. Interestingly, almost every natural product has a variety of pharmacological properties, covering anti-tumor, antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, hypoglycemic, neuroprotective, etc. Additionally, natural products are generally less toxic and very safe, hence becoming an important alternative source of many types of drugs. Over the years, AD has become the fourth leading cause of death after cardiovascular disease, cancer and stroke. Under the circumstance of poor progress in synthetic drug research, natural product anti-AD therapy has become an attractive direction of exploration. Natural products such as curcumin, dihydromyricetin and salidroside have been found to have eminently preventive and therapeutic effects on AD through PI3K/AKT pathway. These natural products are summarized below, and the structure of natural products is listed (Figure 1). The experimental cell, animals, dose and time used in natural product research were summarized in Table 1, providing reference for readers.

Flavonoids

Curcumin is a rare diketone compound in the plant kingdom, mainly extracted from the rhizomes of some plants in Zingiberaceae and Araceae (Mario et al., 2016). The protective property of curcumin on neuronal degeneration caused by mitochondrial dysfunction and the resulting oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis of nerve cells has been demonstrated. And the neuroprotection pathogenesis of curcumin is mediated by two momentous signaling pathways, PI3K/AKT/GSK-3 or PI3K/AKT/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)/brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Kandezi et al., 2020). By regulating above pathway, curcumin inhibits the glutamate-induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome C, the activation of caspse-3, a key enzyme for cell apoptosis, as well as reduces pro-inflammatory biomarkers (interferon-α (IFN-α), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-8) and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines/compounds (IL-10, IL-1) (Wolkmer et al., 2013). It is noteworthy that the increasing clinical data indicate that curcumin is expected to be a standard candidate for neuroprotective agent (Voulgaropoulou et al., 2019). Yet not all clinical trials are positive. Some clinical studies show that curcumin has a beneficial effect on cognitive improvement of AD (Cox et al., 2015; Small et al., 2018). Whereas another suggest that curcumin has no cognitive-enhancing properties (Ringman et al., 2012). Curcumin reduces Aβ deposition in the brain, which is supported by neuroimaging (Small et al., 2018). While in another clinical trial, the results are misty (Ringman et al., 2012).

Dihydromyricetin (DHM), also called ampelopsin, is a dihydroflavonol compound, has been found to markedly rescued apoptosis of neurons in hippocampus of D-gal-induced brain aging model of rats, improving learning and memory impairment (Kou et al., 2016). It activates hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) in pheochromocytoma 12 (PC 12) cells, and increases the expression of HO-1 or enzyme activity, thus againsts H2O2 and 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. The protection of ampelopsin is link to inhibition of rwactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, expression of poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) and caspase-3, inhibition of p38, MAPK phosphorylation and up-regulation of HO-1 expression. Interestingly, the increase in HO-1 expression is mainly due to increased phosphorylation levels of ERK and AKT (Kou et al., 2012). Based on AKT and ERK1/2 signaling, DHM also dose-dependently attenuated sodium nitroprusside induced PC12 cell damage (Liao et al., 2014). In addition, DHM up-regulates Bcl-2, down-regulates cleaved caspase3 and Bax, increases antioxidant capacity and inhibits apoptosis (Mu et al., 2016). In another study, DMY improves glucose metabolism of PC12 cells stimulated by endogenous toxic compound methylglyoxal through AMPK/glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) signaling pathway, inhibiting oxidative stress, and protecting mitochondria of cells (Jiang et al., 2014a). Moreover, DHM has been confirmed to execute its protective function through GSK-3β/Nrf2/antioxidant response element (ARE) signal pathways (Kou et al., 2015).

Icariin (ICA), a flavonol isolated from Epimedium perralderianum Coss (family Berberidacea, genus Epimedium), is the main active component of Epimedium perralderianum. It had previously been observed that ICA alleviated symptoms in AD model animals, which may be caused by increased expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and BDNF, thereby activating PI3K/AKT pathway, inhibiting production of Aβ and tau protein phosphorylation (Wu et al., 2012). A recent in vivo study suggested that the promotion effect of ICA on proliferation and differentiation of hippocampal neural stem cells in AD model is related to the BDNF-tyrosine kinase B (TrkB)-ERK/AKT signaling pathway (Lu et al., 2020). Moreover, ICA treatment significantly enhanced proteasome-dependent degradation of PTEN and protected SK-N-MC cells from Aβ-induced insulin resistance (Zou et al., 2020). In addition, by down-regulating the expression of β-site amyloid precursor protein (APP) cleavage enzyme 1, icariin could decrease the deposition of β-amyloid peptide (Wu et al., 2020).

Phenylpropanoids

Phenylpropanoid compounds incorporate simple phenylpropanoid, coumarin and lignans. Salidroside (Sal), belonging to phenylpropanoid glycoside, is a bioactive substance mainly extracted from traditional herbs such as Rhodiola coccinea (Royle) Boriss., be of a species in the genus Rhodiola (family Crassulaceae). In recent years, Sal has been reported to exhibit great neuroprotection, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptosis and regulation of multiple signal pathways and key molecules (Fan et al., 2020). Zhang et al., in their study on the therapeutic potential of Sal for AD, pointed out that Sal alleviate pathological progression in AD models by reducing amyloidosis and activating PI3K/AKT signaling, suggesting the potential role of Sal in the prevention and treatment of AD due to its neuroprotective property. In addition, mTOR has been found to be a mammalian target that plays an important role in the formation of AD related memories (Zhang et al., 2016a). In a subsequently study, results are similar to Bei et al. However, the alteration of mTOR might be influenced by different animal models or drug delivery methods, and the exact mechanisms remain to be investigated (Wang et al., 2020). Additionally, Sal reduces inflammation and brain injury after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats via PI3K/PKB/Nrf2/NFκB signaling pathway (Zhang et al., 2019a). In an experiment to test the cognitive effect of Sal on AD mice, the researchers demonstrated that Sal reduced the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine inflammatory factors, improving cognitive function in AD mice. The authors suggested that this protective effect may be related to changes in the level of free radicals in the hippocam pus (Li et al., 2018). But it only limited to the guess rather than further inquiry. Structurally, Sal is linked by a glycosidic group to an aglycon (tyrosol) via a β-glycosidic bond. The polyhydroxyl structure of Sal gives it a strong polarity, thereby limiting its diffusion and absorption through the body (Cheng et al., 2012). In order to overcome the above problems, Yang et al. synthesized twenty-six novel derivatives of Sal and evaluated their cell protective effects in CoCl2-treated PC12 cells (Yang et al., 2021). Among the twenty-six salidroside derivatives, five of them showed stronger cell protective effect than Sal (EC50, 0.30 µM) under the same condition. Among them, pOBz had a more significant protective effect (EC50, 0.038 µM). Although the mechanism studies found that pOBz reduced monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity and played a neuroprotective role after MCAO reperfusion in rats, and also inhibited the expression of C3 protein in the brain after cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury, these studies were obviously insufficient. Whether the action mechanism of pOBz and other derivatives is the same as Sal remain to be further studied, and their molecular targets also need to be further studied.

Arctigenin is a phenylpropanoid dibenzylbutyrolactone lignan compound, naturally found in Arctium lappa L. (family Compositae, genus Arctium). Qi et al. firstly elucidated that arctigenin (10, 40, or 150 mg/kg, orally) attenuates the level of phosphorylated tau protein expression in the hippocampus through PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway in Aβ-induced AD mice, hence successfully providing protection against learning and memory deficits (Qi et al., 2017). However, different routes of administration affect the bioavailability of arctigenin in vivo. Pharmacokinetic investigations have shown that the oral administration of arctigenin will cause large amounts of primary metabolism, which would affect its in vivo and clinical efficacy. So it is suggested that Arctigenin should be administered through the intranasal route for the treatment of central nervous system dysfunction (Gao et al., 2018). This suggests that monitoring pharmacokinetics is crucial for better understanding the role of arctigenin. Due to the few researches, clinical trials of arctigenin are rather limited. Therefore the anti-AD effect of arctigenin has not been clinically confirmed. In brief, sufficient research data is required to justify the need for clinical trials. Schizandrol A (SchA), a type of lignans, is a natural active ingredient extracted from Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. (family Schisandraceae, genus Schisandra), the Chinese herb fruit. In a study of the neuroprotective effects of SchA in AD cell models, researchers demonstrated that SchA swimmingly reduces the decrease of living cells, the increase of the number of apoptotic cells, the expresstion of pro-apoptotic proteins and the changes of oxidative stress markers induced by Aβ1-42. Moreover, SchA inhibited the increase of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3)-II/LC3-I and Beclin-1 and the decrease of p62. It revealed that SchA perhaps to be a new drug for the prevention and treatment of AD (Song et al., 2020). SchA has been shown to inhibit ischemia-induced neuronal autophagy via AMPK/mTOR pathway (Wang et al., 2019). A comparative experiment was carried out that SchA (50 μM) combined with norepinephrine (NE, 10 μM) work better than alone (Qi et al., 2020).

Saponins

Ginsenosides are the main bioactive components of Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. (family Araliaceae, genus Panax) with the functions of eliminating free radicals, anti-oxidation, delaying cell aging, protecting nervous system, and improving memory of the elderly, becoming the hot candidate drugs for the treatment of central nervous system diseases. Investigators have showed that ginsenosides enhance the expression of synaptic-related proteins and synaptic plasticity, up-regulate the expression of CREB and BDNF, reduce apoptosis and AD pathology-like protein expression, scavenge free radicals and protect nerve cells (Lulin et al., 2017). A study on HT22 cells and APPSW SH-SY5Y cells demonstrated that RG1 promoted a-secretase cleavage of APP by activating ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathway (Shi et al., 2012). Li et al. also illustrated via experiments that ginsenosides improve memory and reduce the content of Aβ1-42 and p-tau in AD mice, and the anti-AD effect of ginsenoprotein is mediated by activating PI3K/AKT signal pathway (Li et al., 2016). Other studies have confirmed that ginsenoside Rg2, one of the most important active components of ginsenosides, significantly inhibits the apoptosis of Aβ treated PC12 cells by up-regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which may be caused by the decrease of ROS and intracellular Ca2+ concentration by ginsenoside, the activation of autophagy pathway, the up-regulation of Bcl-2 and the down-regulation of Bax (Cui et al., 2017a). Taken together, ginsenosides are deemed as potential new drugs for the treatment of AD (Cui et al., 2020).

Notoginsenoside R1 also possesses a certain repair effect on AD (Hu et al., 2020). Notoginseng R1 as reported conspicuously improved the cell damage induced via Aβ25–35 by increasing cell activity, inhibiting oxidative stress and the activation of MAPK signaling pathway (Ma, 2014). Meng et al. have found that the neuroprotection of notoginsenoside R1 is related to estrogen receptor dependence, and the up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes is associated to AKT and ERK1/2, as well as Nrf2 pathway (Meng et al., 2014).

Non-flavonoid Polyphenols

Being a naturally occurring stilbene, piceatannol (PT) has been reported to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic and neuroprotective effects (Zhang et al., 2018). In an early study, the effects of PT and pterostilbene (PS) against Aβ-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells were evaluated. The results show that PT and PS have obvious anti-apoptotic activity. PT up-regulates the PI3K/AKT/BAD signaling pathway, further inhibits the expression of Bcl-2/Bax, the cleavage of caspase-9, caspase-3 and PARP. While PS promotes phosphorylation of AKT without affecting other factors (Fu et al., 2016). What’s more, the active fraction derived from Litchi chinensis Sonn. (family Sapindaceae, genus Litchi) seed can improve the cognitive function and behavior of AD model rats through decreasing Aβ fibril formation and Tau hyperphosphorylation. Catechin, proanthocyanidin A1 and proanthocyanidin A2 polyphenols isolated from seed of Litchi chinensis Sonn. inhibit hyperphosphorylated Tau protein by up-regulating IRS-1/PI3K/AKT and down-regulating GSK-3 (Fu et al., 2016).

Others

Being commonly used spices, Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. (Z. bungeanum) (family Rutaceae, genus Zanthoxylum) and its ingredients possess anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and neuroprotective effects (Deng et al., 2019). Zhao et al. demonstrated for the first time that Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim water extract (WEZ) and volatile oil extract (VOZ) inhibit apoptosis and oxidative stress by activating PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 signal pathway, attenuating impairment of d-galactose-induced aging mice. Unfortunately, the specific active ingredients have not been reported (Zhao et al., 2020). Evaluated the functions of Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L'Hér. ex Vent. (family Moraceae, genus Broussonetia) in both mouse and cell models of AD, Li and colleagues found that Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L'Hér. ex Vent. up-regulates AKT and β-catenin signaling pathways in the pretreated PC12 cells (Li Y.-h. et al., 2020). Same as other traditional Chinese herbal medicine with a variety of components, which component plays a critical role in AD is unclear.

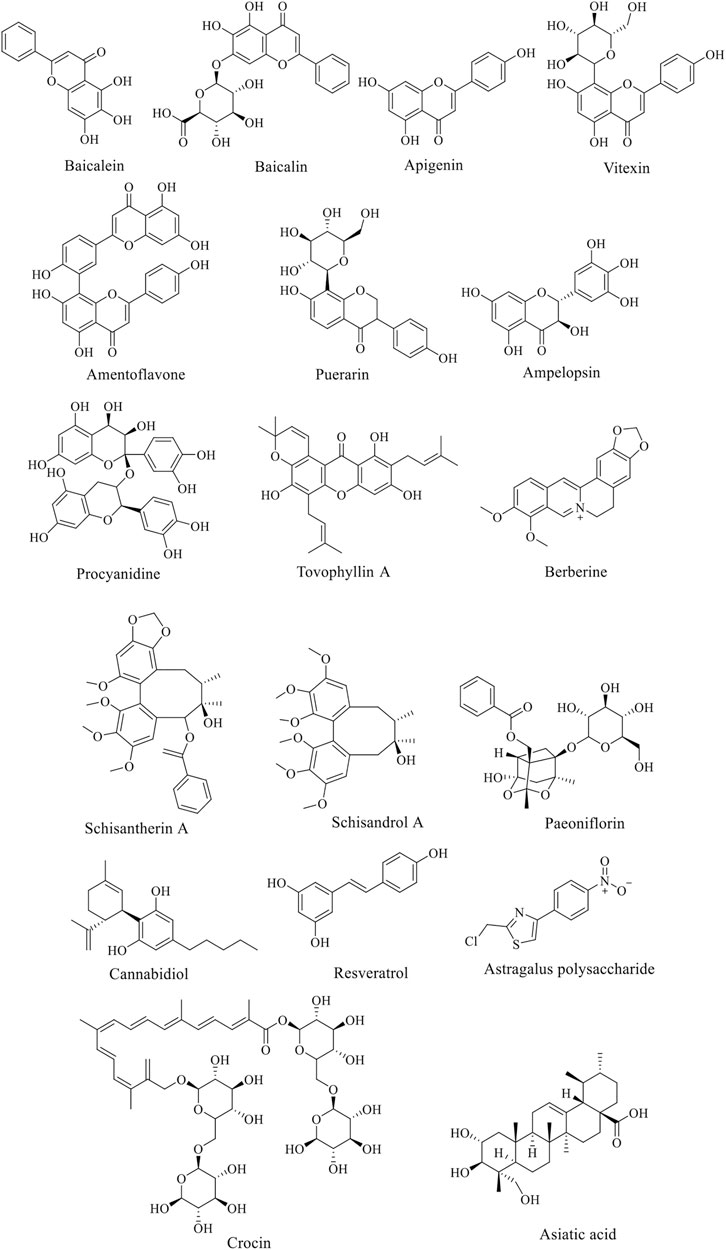

Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease Based on PI3K/AKT Pathawy

Due to the complex pathogenesis of PD, there is no specific drug for it so far. The research and development of anti-PD drugs have attracted great attention from the medical community all over the world. In recent years, with the deepening of the research on neurophysiology, biochemical and pharmacology of the elderly, the research on the development of natural products against PD is in hot progress. Thanks to the efforts of many scholars, many natural products have been proved to have good effects on the treatment of PD. Natural flavonoids products, such as icariin, baicalein, other products like berberine, paeoniflorin, etc. have achieved great success in PD model animals and in vitro cell experiments.

Flavonoids

Baicalein is a bioactive flavonoid monomer compound isolated from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (family Lamiaceae, genus Scutellaria). Evidences suggest that baicalein have neuroprotective functions in addition to antioxidation such as alleviate the symptoms of AD and PD (Li et al., 2017). According to previous studies, baicalein was found to have a neuroprotective effect on acrolein-induced neurotoxicity at multiple levels (Zhao et al., 2017). And baicalein pretreatment significantly inhibited 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2019). Zhang et al. showed that the anti-PD function of baicalein is probably related to the activation of Nrf2/HO-1, protein kinase C (PKC) and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (Zhang et al., 2012). Baicalin has one more glucuronide in the seven hydroxyl group than baicalein (Figure 2), which inhibit 6-OHDA-induced apoptosis of substantia nigra neurons in PD rats through mTOR/AKT/GSK-3β pathway (Zhai et al., 2019). Apigenin has been shown to remarkably reduce the effects of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPP+)-induced apoptosis in experimental models of PD. Furthermore, the glucoside derivative Vitexin of apigenin and several other flavonoid species showed similar protective effects on PD cells and mouse models (Ming et al., 2018).

Amentoflavone (AF) is an effective component of Selaginella tamariscina (P.Beauv.) Spring (family Selaginellaceae, genus Selaginella). In an in vitro of PD model study by Cao et al., AF enhanced PI3K phosphorylation, and reduced the loss of cell viability induced by MPP+, without obvious cytotoxicity. It also inhibits the activation of caspase-3 and p21, but increases the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. In vivo, AF significantly reduces the loss of dopaminergic neurons in SNpc and striatal fibers induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), and enhances the activation of PI3K and AKT and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax in SN (Cao et al., 2017). Similarly, the PD mouse experiment of icariin obtained a similar conclusion as AF (Chen et al., 2017). Puerarin (PUE) is a vital isoflavone compound in traditional Chinese medicine Pueraria lobata. Zhang et al. have shown that PUE could reduce the protection of dopaminergic neurons from rotenone toxicity in PD animal model of PD by activating PI3K/AKT signal pathway, and decrease the overexpression of abnormal proteins in PD animal model (Zhang et al., 2014).

According to the reports, Ampelopsin increases the antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activity of cells through ERK1/2 and AKT signaling pathways, thus protecting neurons (Coria et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020). Likewise, Procyanidine (PC), widely found in Vitis vinifera L. (family Vitaceae, genus Vitis) and other plants, tellingly scavenge free radicals, inhibits neuronal apoptosis and protects mitochondria (Zhang et al., 2019b). In recent years, Tovophyllin A (TA) has been reported to play a useful role in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Some studies have found that TA has significant neuroprotective effects on primary cortical neurons injured by MPP+/paraquat and PD mouse model induced by MPTP. The mechanism is confirmed to be related to the apoptosis signal pathway of AKT/GSK-3 cells, but it still need a further explored (Huang et al., 2020). It has also been reported that curcumin inhibits the activation of astrocytes and microglia (Fu et al., 2015), and protects mitochondrial membrane potential from oxidative damage to dopaminergic neurons (Ma and Guo, 2017). Curcumin could conspicuously improve the oxidative damage of dopaminergic neurons induced by oxidative stress in the compact part of substantia nigra of rats via activating AKT/Nrf2 signal pathway, demonstrating great therapeutic impact on the experimental model of PD (Cui et al., 2016).

Alkaloids

Berberine (BBR), an alkaloid in the medicinal plants such as coptis chinensis Franch. (family Ranunculaceae, genus Coptis) and Phellodendron amurense Rupr. (family Rutaceae, genus Phellodendron), is proved to be of anti-oxidative stress and anti-apoptotic role in central nervous system diseases. The low concentration of BBR can significantly reduce apoptosis induced by Cytomegalovirus in cultured spiral ganglion cells via NMDAR1/Nox3, decreasing mitochondrial ROS generation (Zhuang et al., 2018). It have be reported that BBR inhibits ROS levels, mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial autophagy by PI3K/AKT/mTOR signal pathway, thus protecting PC12 cells from oxidative damage (Zhang et al., 2017). In another research, a new concept emerged that BBR can attenuate the cytotoxicity induced by tert-butyl peroxide (t-BHP) (Deng et al., 2020). Han et al. demonstrated once again that berberine protects SH-SY5Y cells treated with rotenone through antioxidant and activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Li Z. et al., 2020).

Phenylpropanoids

Lignans are natural compounds polymerized from 2-molecular phenylpropanoid derivatives. Schisandra chinensis lignans (SCL) of include Schisandra Ester A, B, C and D. Previous studies have suggested that the protective effect of SCL on cerebral ischemic nerve injury may be achieved through PI3K/AKT pathway. Meso-dihydroguaiaretic acid, schiarisanrin A and heteroclitin D, lignans isolated from the root of Kadsura coccinea (Lem.) A.C.Sm. (family Schisandraceae, genus Kadsura), significantly inhibit LPS-induced neuronal injury through the same signal pathway (Jiang et al., 2014b). Schisantherin A has been reported to enhance antioxidant stress, inhibit the overproduction of nitric oxide and prevent the loss of dopaminergic neurons stimulated by 6-OHDA in zebrafish (Zhang et al., 2015). On the side, schisandrol A, by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, inhibits the IKK/IκBα/NF-κB pathway, reduces neuronal inflammation and oxidative stress, and improves the survival of dopamine neurons in the brain of mice, showing promising prospects in the treatment of PD (Yan et al., 2019). In MPTP-induced PD mice, treatment with high dose of schisandrol A (40 mg/kg) significantly reduce cytokines, such as IL-1β or TNF-α, and inhibit the activity of MDA, but increase SOD, improving antioxidant defences. While low dose of schisandrol A (20 mg/kg) showed no above effect. Additionlly, autophagy-related proteins LC3-II, Beclin1, Parkin, Pink1, and mTOR were expressed after schisandrol A treatment (Zhi et al., 2019).

Glycosides

Paeoniflorin (PF), a bicyclic monoterpene glycoside (Figure 2), is the main active component of Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (family Paeoniaceae, genus Paeonia). In addition to anti-inflammation and anti-oxidation, PF also has neuroprotective effects and can be used in the treatment of cerebral ischemia, epilepsy and PD (Gu et al., 2016). Zheng et al. found that PF plays a neuroprotective role through the Bcl-2/Bax/caspase-3 pathway in vitro cell experiments. In PD mouse models, PF treatment protected dopaminergic neurons by preventing MPTP-induced declines in the levels of striatal and melanotic dopaminergic transporters (DAT) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) proteins and altering dopamine catabolism (Zheng et al., 2017).

Non-flavonoid Polyphenols

Resveratrol is an antitoxin produced by many plants when they are stimulated. The experiment results showed that resveratrol delay the progression of PD symptoms by activating SIRT1/AKT1 and PI3K/AKT signal pathway (Wang et al., 2018a; Huang et al., 2019). As a compound extracted from Cannabis sativa L. (family Cannabaceae, genus Cannabis), Cannabidiol (CBD) has a series of physiological functions, such as blocking breast cancer metastasis, treating epilepsy, anti-insomnia and so on. It also has a good effect on the treatment of nervous system diseases. A study suggested that the prevention and protection of CBD on PD seem to be mediated by activating ERK and AKT/mTOR pathways. This protective effect could be eliminated by AKT1/2 inhibitors and mTOR inhibitors (Gugliandolo et al., 2020). In 2020, a Brazilian team published a paper discussing the biological basis for the potential role of CBD, as well as the team’s preclinical and clinical studies of CBD in Parkinson’s disease. The three clinical studies include open label studies (six patients), case series (four patients), and randomized controlled trials (twenty-one patients) (Zuardi et al., 2009; Chagas et al., 2014; Ferreira-Junior et al., 2020). Although these studies have shown beneficial results, they are limited by the small sample size and short follow-up time, which make the results inconclusive. Recently, a first clinical trial of the efficacy of relatively high doses of CBD (20 mg/kg/day) on PD patients examined the tolerability and effectiveness of a range of doses in the PD population (Leehey et al., 2020). However, the study is limited due to the lack of a placebo arm and a small group of participants. And adverse reactions were found at high doses. Therefore, a large number of studies on CDB are still needed to explore the in-depth mechanism of CDB on PD and its biosafety for patients.

Others

Crocin is a carotenoid found in Crocus sativus L. (family Iridaceae, genus Crocus), which shows beneficial effects on neurodegenerative diseases through anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. However, the exact molecular pathway of the neuroprotective effect of safflower has not been fully elucidated. In rotenone (ROT)-induced rat PD model, crocin visiblystimulated PI3K/AKT pathway and decreased the expression of GSK-3, FoxO3a and downstream caspase-9, presenting a good neuroprotective founction (Salama et al., 2020). Astaxanthin (AST), as a lipid-soluble pigment, inhibits apoptosis and neuronal injury by up-regulating phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT in vivo and vitro, and it is considered for the treatment of AD and PD (Zarneshan et al., 2020). Moreover, asiatic acid (AA), a pentacyclic triterpene obtained from Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (family Apiaceae, genus Centella), has been shown to effectively provide neuroprotection for MPTP-induced neuron cell loss through ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR/GSK-3 pathway (Nataraj et al., 2017). The phosphorylation levels of AKT and mTOR could be increased by both Lycium barbarum polysaccharide (LBP) (Wang et al., 2018b) and Astragalus polysaccharides (APS) (Tan et al., 2020), effectively alleviate the nigral striatal system degeneration and regulation of cell autophagy, thereby affecting the occurrence and development of PD.

Discussion

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis throughout the life cycle. This pathway is triggered by the expression or abnormal regulation of many genes and has been found to be associated with numerous human diseases (Mengqiu et al., 2019). On the one hand, the excessive activation of PI3K/AKT pathway associated with diseases such as cancers and diabetes. On the other hand, deregulating its action might be relevant to cardiovascular diseases, and neurological diseases like AD and PD. Therefore, the study of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and its upstream and downstream molecular mechanisms is of great significance for the prevention and treatment of various diseases. According to existing studies, many natural compounds have shown symptomatic alleviating effects on neurological diseases AD or PD, and such effects have been found to be related to the regulation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. However, it is not certain that whether this pathway plays a key role in this process. In other words, more evidence is needed to determine if this pathway be able to a target for drugs acting on AD or PD. Moreover the complex pathogenesis of these diseases and the multifactorial effects of natural products also bring challenges to explore the synergistic effects of various mechanisms, so that the molecular mechanisms of the neuroprotective effects of natural products also need to be further elucidated.

It is known that numerous natural products with medicinal potential are derived from a wide variety of vegetables, fruits and Chinese herbs, some scholars believe that dietary adjustments might be help for the prevention and treatment of diseases. (Kitagishi et al., 2014). For instance, multiple clinical trials have investigated the effect of curcumin on AD. But in most of these trials, curcumin was used as a dietary supplement, like an ongoing clinical trial in India about the efficacy and safety of curcumin formulation in Alzheimer’s disease (Bhat et al., 2019). Even though there are no clinical reports of true dietary supplements for the treatment of neurological diseases, preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated in some respects that diet still has merit as an adjunct preventive approach.

In reviewing the literature, we found that a variety of common natural polyphenols possess neuroprotective effects, including flavonoids and non-flavonoids, such as curcumin, icariin, baicalein and cannabidiol. However, it is a pity that many natural compounds, including natural flavonoids, are often limited in their application due to bioavailability and other defects. Consequently, using natural products as lead compounds and key pharmacophore targets to develop more effective and safer derivatives with high bioavailability may be a promising strategy for new drug development. For instance, curcumin is eliminated in vivo easily as its hydrophobicity and low bioavailability (Gupta et al., 2012; De Oliveira et al., 2016; Mirzaei et al., 2017), but such problems can be solved by modifying the structure of curcumin and synthesizing a series of derivatives (Bagheri et al., 2020). And the low solubility of baicalein is able to improve by nano-loading, that is, the oral bioavailability of baicalein is improved by nano-emulsion or nano-crystal loaded with baicalein (Liu et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2017). We summarize the natural products mentioned above that have the potential to treat AD and PD, as shown in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. The structure of the active ingredients is show in Figure 1 and Figure 2, and so do some relevant information for reference (Table 1). It can be learned that the treatment of natural products is a relatively long process, and some natural products could exert better effects at lower doses. But some are ineffective at low doses and require high concentrations to be effective. The therapeutic effects are connected with the dosage, time, and mode of administration. For instance, at low concentrations (0.12–16 µM), BBR dramatically recedes 6-OHDAinduced cytotoxicity through the activation of PI3K/AKT/Bcl-2 cell survival and Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidative signaling pathways. However, However, treatment with high concentrations (16 µM) BBR did not show protective effect (Zhang et al., 2017). A study investigated the role of curcumin and erythropoietin in an ICV-STZ rat model (a model for sporadic dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (SDAT)) (Samy et al., 2016). The experimental animals were given vehicle, oral administration of curcumin (80 mg/kg/day), an intraperitoneal injection of erythropoietin (500 IU/kg every other day) as well as combined curcumin and erythropoietin for 3 months. The results showed that curcumin and/or erythropoietin were beneficial in restoring the behavioral, histological, and biochemical changes induced by ICV-STZ. And the long-term adverse effects of curcumin were lower than those of erythropoietin. In contrast, Bassani et al. found no beneficial effect in short-term spatial memory in ICV-STZ rats by evaluating extended oral curcumin (doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg) (Bassani et al., 2017). But improvements were found in short-term cognitive memory. In addition, the combination of natural products with existing drugs is also a direction worth exploring. A report indicates that combination treatment of icariin and L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) are beneficial for the treatment of dopamine neurotoxicity in 6-OHDA injury (Lu et al., 2018).

Each new drug should be clinically tested after developed but before used in humans. Practically, the fact that the results of animal and human are not exactly consistent is worrisome. In animal studies, certain natural products have shown great promise in treating Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive aging, but this has not been observed in all clinical trials. After all, there is no animal model at the moment really reproduces all the symptoms observed in human pathology. In contrast to animal studies, the number of confirmed human studies is limited, and many of the results remain controversial. However, natural products are widely available, relatively safe and easy to obtain, making the research still extraordinary significance. Consequently, it is essential to conduct more long-term studies to assess the possibility of side effects from chronic administration in humans.

Prospect

Scientists have never stopped exploring the complex pathogenesis of AD and PD. It is exciting that great progress has been made in recent years, which supply more possibilities to overcome these diseases. However, we also note that a small number of new drugs have been developed for the treatment of AD and PD over the years, and most of them are still in the stage of basic research. The pathological changes associated with the onset of neurodegenerative diseases are irreversible. When cognitive impairment shows up in patients, the course of the disease are often in the middle or late stage, as a result, the treatment can only slow down rather than reverse the development of the disease. Undoubtedly, it is particularly important for early prevention and diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. Further research into its pathogenesis is needed to develop drugs to reverse the progression of AD and PD. Substantial amounts of studies on natural products with multiple activities have proved to be of positive significance for the treatment of such diseases. In-depth research on natural products will bring more hope for the treatment of diseases, and at the same time promote the development of traditional Chinese herbal medicine. The direction for the continued research of natural products has also been proposed in the previous discussion: (I) the diseases prevention and control mechanisms of natural products are worthy of further investigation; (II) structural modification as a lead compound; (III) application of nanotechnology for decoration; (IV) combination with other drugs. Finally, it should be noted that the key to determining the safety and effectiveness of the final drug lies in conduct extensive clinical trials.

Author Contributions

H-ZL completed the manuscript. YC, Z-WZ, D-DW and H-YL helped in searching for related articles. The revision of the manuscript was collaboratively finished by H-ZL, YC, Z-WZ, H-YL, D-DW and L-CG. All authors contributed to the article and finally the submitted version is approved by L-CG.

Funding

This work was supported by Science and Technology Key Program of Hunan Province Grants (2016SK 2066), Key Projects of Hunan Health Committee (B2017207), Hunan Province Chinese Medicine Research Program Grants (201940), Changsha City Science and Technology Program Grants (kq1801144), Changsha Central Hospital Affiliated to University of South China Foundation of key Program (YNKY201901), Hunan Province Foundation of High-level Health Talent (225 Program), and Science and Technology Key Program of Hunan Provincial Health Committee (20201904).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.648636/full#supplementary-material.

Glossary

6-OHDA 6-hydroxydopamine

AA asiatic acid

AD Alzheimer’s disease

AF amentoflavone

AKT protein kinase B

AMPA α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolpropionic acid

APP amyloid precursor protein

APS astragalus polysaccharides

ARE antioxidant response element

AST astaxanthin

Aβ, amyloid protein

BACE1 β-secretase 1

Bad Bcl2-antagonist of cell death

Bax BCL2-associated X protein

Bcl-2 B-cell lymphoma 2

BDNF Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

BIM Bcl-2-like protein 11

CBD Cannabidiol

CNKI China national knowledge infrastructure

CREB cAMP response element-binding protein

DA Dopaminergic

DAT Dopaminergic transporters

DHM Dihydromyricetin

DNA-PK DNA-dependent protein kinases

ERK Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

FB Fructus broussonetiae

FGF Fibroblast growth factor

FoxO1 Caspase-9 and forkhead box protein

GLUT4 Glucose transporter 4

GPCR G protein coupled receptors

GSK-3β Glycogen synthase kinase-3β

HO-1 Heme oxygenase 1

Hsp Heat shock protein

ICA Icariin

IFN-α Interferon-α; α TrkB, tyrosine kinase B

IGF Insulin-like growth factor

IKK IκB kinase

IL1β Interleukin-1 β

ILK Integrin-linked kinase

IRS Insulin receptor substrate

JNK c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase

LBP Lycium barbarum polysaccharide

l-DOPA L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

LSF Active fraction of lychee seed

LTP Long term potentiation

MAO Monoamine oxidase

mLST8 SEC13 protein 8

MMP Mitochondrial membrane potential

MMP+ 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine

MPTP 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

mTOR Mammalian target of rapamycin

mTORC2 Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2

NE Norepinephrine

NFT Neurofibrillary tangles

NF-κB Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

NMDA N-methyl-d-aspartic acid

Nrf2 Nuclear factor erythrocyte 2-related factor 2

PARP Poly ADP-ribose polymerase

PC Procyanidine

PC12 Pheochromocytoma 12

PD Parkinson’s disease

PDGF Platelet-derived growth factor

PDK1 Phosphatidylinositol dependent protein kinase 1

PF Paeoniflorin

PHLPP PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase

PI3K Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

PIP2 Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-disphosphate

PIP3 Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

PKB Protein kinase B

PKC Protein kinase C

PP2A Protein phosphatase 2 A

PS Pterostilbene

PT Piceatannol

PTEN Phosphatase and tensin homolog

PUE Puerarin

REDD1 DNA damage responses 1

ROS Rwactive oxygen species

ROT Rotenone

RTK Receptor tyrosine kinase

Sal Salidroside

SchA Schizandrol A

SCL Schisandra chinensis lignans

SDAT Sporadic dementia of the Alzheimer’s type

SH Src Homology

SHIP1 Src homology domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase 1

SIRT1 Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog-1

SN Substantia nigra

SNpc Substantia nigra compacta

SP Senile plaque

TA Tovophyllin A

t-BHP| Tert-butyl peroxide

TH Tyrosine hydroxylase

TNF-α Tumor necrosis factor-α

VOZ Zanthoxylum bungeanum volatile oil extract

VPS34 Vacuolar protein sorting 34

WEZ Zanthoxylum bungeanum water extract

References

Altomare, D. A., Testa, J. R., Testa, A., and Joseph, R. (2005). Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 24 (50), 7455–7464. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209085

Bagheri, H., Ghasemi, F., Barreto, G. E., Rafiee, R., Sathyapalan, T., and Sahebkar, A. (2020). Effects of curcumin on mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases. Biofactors. 46 (1), 5–20. doi:10.1002/biof.1566

Bassani, T. B., Turnes, J. M., Moura, E. L. R., Bonato, J. M., Cóppola-Segovia, V., Zanata, S. M., et al. (2017). Effects of curcumin on short-term spatial and recognition memory, adult neurogenesis and neuroinflammation in a streptozotocin-induced rat model of dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Behav. Brain Res. 335, 41–54. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2017.08.014

Batista, P., and Pereira, A. (2016). Quality of life in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosci. 7 (1). doi:10.21767/2171-6625.100074

Bellacosa, A., Kumar, C. C., Cristofano, A. D., and Testa, J. R. (2005). Activation of AKT kinases in cancer: implications for therapeutic targeting. Adv. Cancer Res. 94 (1), 29–86. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(05)94002-5

Bertacchini, J., Heidari, N., Mediani, L., Capitani, S., Shahjahani, M., Ahmadzadeh, A., et al. (2015). Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR network for treatment of leukemia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72 (12), 2337–2347. doi:10.1007/s00018-015-1867-5

Bhat, A., Mahalakshmi, A. M., Ray, B., Tuladhar, S., Hediyal, T. A., Manthiannem, E., et al. (2019). Benefits of curcumin in brain disorders. Biofactors 45 (5), 666–689. doi:10.1002/biof.1533

Cao, Q., Qin, L., Huang, F., Wang, X., Yang, L., Shi, H., et al. (2017). Amentoflavone protects dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model mice through PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 319, 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2017.01.019

Chagas, M. H. N., Zuardi, A. W., Tumas, V., Pena-Pereira, M. A., Sobreira, E. T., Bergamaschi, M. M., et al. (2014). Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 28 (11), 1088–1098. doi:10.1177/0269881114550355

Chen, W.-F., Wu, L., Du, Z.-R., Chen, L., Xu, A.-L., Chen, X.-H., et al. (2017). Neuroprotective properties of icariin in MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: involvement of PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Phytomedicine. 25, 93–99. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2016.12.017

Cheng, Q., Zhang, S., and Ding, F. (2012). Determination of salidroside in rats and its pharmacokinetic profile. Lishizhen Med. Materia Med. Res. 10, 2422–2424.

Chong, Z. Z., Shang, Y. C., Wang, S., and Maiese, K. (2012). A critical kinase cascade in neurological disorders: PI3K, Akt and mTOR. Future Neurol. 7 (6), 733–748. doi:10.2217/fnl.12.72

Coria, H. M., Mendoza Rojas, M. X., Arrieta Cruz, I., and Valdés, H. E. L. (2019). Preclinical research of dihydromyricetin for brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1334. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01334

Cox, K. H., Pipingas, A., and Scholey, A. B. (2015). Investigation of the effects of solid lipid curcumin on cognition and mood in a healthy older population. J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (5), 642–651. doi:10.1177/0269881114552744

Cui, J., Shan, R., Cao, Y., Zhou, Y., Liu, C., and Fan, Y. (2021). Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 against memory impairment and neuronal death induced by Aβ25-35 in rats. J. Ethnopharmacology 266, 113466. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113466

Cui, J., Wang, J., Zheng, M., Gou, D., and Zhou, Y. (2017a). Ginsenoside Rg2 protects PC12 cells against β-amyloid 25-35 -induced apoptosis via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 275, 152-161. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.07.021

Cui, W., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Sun, C., Zhang, Y., et al. (2017b). Inhibition of PTEN attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis via activation of PI3K/AKT pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 42 (11), 3052–3060. doi:10.1007/s11064-017-2338-1

Cui, Q., Li, X., and Zhu, H. (2016). Curcumin ameliorates dopaminergic neuronal oxidative damage via activation of the Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 13 (2), 1381–1388. doi:10.3892/mmr.2015.4657

De Oliveira, M. R., Jardim, F. R., Setzer, W. N., Nabavi, S. M., and Nabavi, S. F. (2016). Curcumin, mitochondrial biogenesis, and mitophagy: exploring recent data and indicating future needs. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 813–826. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.04.004

Deng, H., Jia, Y., Pan, D., and Ma, Z. (2020). Berberine alleviates rotenone-induced cytotoxicity by antioxidation and activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroreport. 31 (1), 41–47. doi:10.1097/WNR.0000000000001365

Deng, S., Rong, H., Tu, H., Zheng, B., Mu, X., Zhu, L., et al. (2019). Molecular basis of neurophysiological and antioxidant roles of Szechuan pepper. Biomed. Pharmacother. 112, 108696. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108696

Do, T. D., Economou, N. J., Chamas, A., Buratto, S. K., Shea, J.-E., Bowers, M. T., et al. (2014). Interactions between amyloid-β and tau fragments promote aberrant aggregates: implications for amyloid toxicity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 118 (38), 11220–11230. doi:10.1021/jp506258g

Dobbin, Z., and Landen, C. (2013). The importance of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway in the progression of ovarian cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 14 (4), 8213–8227. doi:10.3390/ijms14048213

Fan, F., Yang, L., Li, R., Zou, X., Li, N., Meng, X., et al. (2020). Salidroside as a potential neuroprotective agent for ischemic stroke: a review of sources, pharmacokinetics, mechanism and safety. Biomed. Pharmacother. 129, 110458. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110458

Ferreira-Junior, N. C., Campos, A. C., Guimarães, F. S., Del-Bel, E., Zimmermann, P. M. d. R., Brum Junior, L., et al. (2020). Biological bases for a possible effect of cannabidiol in Parkinson’s disease. Braz. J. Psychiatry 42 (2), 218–224. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0460

Fu, W., Zhuang, W., Zhou, S., and Wang, X. (2015). Plant-derived neuroprotective agents in Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Transl Res. 7 (7), 1189–1202.

Fu, Z., Yang, J., Wei, Y., and Li, J. (2016). Effects of piceatannol and pterostilbene against β-amyloid-induced apoptosis on the PI3K/Akt/Bad signaling pathway in PC12 cells. Food Funct. 7 (2), 1014–1023. doi:10.1039/c5fo01124h

Gao, L., Zhou, F., Wang, K.-x., Zhou, Y.-z., Du, G.-h., Qin, X.-m., et al. (2020). Baicalein protects PC12 cells from Aβ25-35-induced cytotoxicity via inhibition of apoptosis and metabolic disorders. Life Sci. 248, 117471. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117471

Gao, Q., Yang, M., and Zuo, Z. (2018). Overview of the anti-inflammatory effects, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacies of arctigenin and arctiin from Arctium lappa L. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39 (5), 787–801. doi:10.1038/aps.2018.32

Garofalo, R. S., Orena, S. J., Rafidi, K., Torchia, A. J., Stock, J. L., Hildebrandt, A. L., et al. (2003). Severe diabetes, age-dependent loss of adipose tissue, and mild growth deficiency in mice lacking Akt2/PKBβ. J. Clin. Invest. 112 (2), 197–208. doi:10.1172/jci16885

Ghoneum, A., and Said, N. (2019). PI3K-AKT-mTOR and NFκB pathways in ovarian cancer: implications for targeted therapeutics. Cancers 11 (7), 949. doi:10.3390/cancers11070949

Gong, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Li, X., Xia, X.-J., Liu, Y.-Y., et al. (2018). Lentiviral vector-mediated SHC3 silencing exacerbates oxidative stress injury in nigral dopamine neurons by regulating the PI3K-AKT-FoxO signaling pathway in rats with Parkinson’s disease. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 49 (3), 971–984. doi:10.1159/000493228

Gu, X.-S., Wang, F., Zhang, C.-Y., Mao, C.-J., Yang, J., Yang, Y.-P., et al. (2016). Neuroprotective effects of paeoniflorin on 6-OHDA-lesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 41 (11), 2923–2936. doi:10.1007/s11064-016-2011-0

Gugliandolo, A., Pollastro, F., Bramanti, P., and Mazzon, E. (2020). Cannabidiol exerts protective effects in an in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease activating AKT/mTOR pathway. Fitoterapia 143, 104553. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104553

Guo, C.-h., Cao, T., Zheng, L.-t., Waddington, J. L., and Zhen, X.-c. (2020). Development and characterization of an inducible Dicer conditional knockout mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: validation of the antiparkinsonian effects of a sigma-1 receptor agonist and dihydromyricetin. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 41 (4), 499–507. doi:10.1038/s41401-020-0379-5

Gupta, S. C., Patchva, S., Koh, W., and Aggarwal, B. B. (2012). Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its miraculous biological activities. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 39 (3), 283–299. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05648.x

Hanada, M., Feng, J., and Hemmings, B. A. (2004). Structure, regulation and function of PKB/AKT--a major therapeutic target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1697 (1), 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.009

Hetman, M., Chen, W. T., Kuo, Y. Y., Lin, G. B., Lu, C. H., Hsu, H. P., et al. (2020). Thermal cycling protects SH-SY5Y cells against hydrogen peroxide and β-amyloid-induced cell injury through stress response mechanisms involving Akt pathway. PLoS One 15 (10), e0240022. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240022

Hu, M., Li, F., and Wang, W. (2018). Vitexin protects dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 12, 565–573. doi:10.2147/dddt.s156920

Hu, T., Li, S., Liang, W.-Q., Li, S.-S., Lu, M.-N., Chen, B., et al. (2020). Notoginsenoside R1-induced neuronal repair in models of alzheimer disease is associated with an alteration in neuronal hyperexcitability, which is regulated by nav. Front. Cel. Neurosci. 14, 280. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.00280

Huang, N., Zhang, Y., Chen, M., Jin, H., Nie, J., Luo, Y., et al. (2019). Resveratrol delays 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Exp. Gerontol. 124, 110653. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2019.110653

Huang, Y., Sun, L., Zhu, S., Xu, L., Liu, S., Yuan, C., et al. (2020). Neuroprotection against Parkinson’s disease through the activation of akt/gsk3β signaling pathway by Tovophyllin A. Front. Neurosci. 14, 723. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00723

Jiang, B., Le, L., Pan, H., Hu, K., Xu, L., Xiao, P., et al. (2014a). Dihydromyricetin ameliorates the oxidative stress response induced by methylglyoxal via the AMPK/GLUT4 signaling pathway in PC12 cells. Brain Res. Bull. 109, 117–126. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.10.010

Jiang, E. P., Wang, S. Q., Wang, Z., Yu, C. R., Chen, J. G., Yu, C. Y., et al. (2014b). [Effect of Schisandra chinensis lignans on neuronal apoptosis and p-AKT expression of rats in cerebral ischemia injury model]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 39 (9), 1680–1684. doi:10.4268/cjcmm20140927

Kandezi, N., Mohammadi, M., Ghaffari, M., Gholami, M., Motaghinejad, M., Safari, S., et al. (2020). Novel insight to neuroprotective potential of curcumin: a mechanistic review of possible involvement of mitochondrial biogenesis and PI3/akt/GSK3 or PI3/akt/CREB/BDNF signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Cel Med. 9 (1), 1–32. doi:10.22088/IJMCM.BUMS.9.1.1

Kitagishi, Y., Nakanishi, A., Ogura, Y., and Matsuda, S. (2014). Dietary regulation of PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 6 (3), 35. doi:10.1186/alzrt265

Kou, X., Li, J., Bian, J., Yang, Y., Yang, X., Fan, J., et al. (2015). Ampelopsin attenuates 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity by regulating GSK-3β/NRF2/ARE signalling. J. Funct. Foods. 19, 765–774. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2015.10.010

Kou, X., Liu, X., Chen, X., Li, J., Yang, X., Fan, J., et al. (2016). Ampelopsin attenuates brain aging of D-gal-induced rats through miR-34a-mediated SIRT1/mTOR signal pathway. Oncotarget. 7 (46), 74484–74495. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.12811

Kou, X., Shen, K., An, Y., Qi, S., Dai, W.-X., Yin, Z., et al. (2012). Ampelopsin inhibits H2 O2 -induced apoptosis by ERK and akt signaling pathways and up-regulation of heme oxygenase-1. Phytother. Res. 26 (7), 988–994. doi:10.1002/ptr.3671

Laplante, M., and Sabatini, D. M. (2012). mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149 (2), 274–293. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017

Leehey, M. A., Liu, Y., Hart, F., Epstein, C., Cook, M., Sillau, S., et al. (2020). Safety and tolerability of cannabidiol in Parkinson disease: an open label, dose-escalation study. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 5 (4), 326–336. doi:10.1089/can.2019.0068

Li, H., Kang, T., Qi, B., Kong, L., Jiao, Y., Cao, Y., et al. (2016). Neuroprotective effects of ginseng protein on PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the hippocampus of D -galactose/AlCl 3 inducing rats model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacology 179, 162–169. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.020

Li, Q., Wang, J., Li, Y., and Xu, X. (2018). Neuroprotective effects of salidroside administration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 17, 7287–7292. doi:10.3892/mmr.2018.8757

Li, Y.-h., , Jin, Y., Wang, X.-s., Chen, X.-l., Chen, H.-b., Xu, J., et al. (2020). Neuroprotective effect of fructus broussonetiae on APP/PS1 mice via upregulation of AKT/β-Catenin signaling. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 27, 115. doi:10.1007/s11655-019-3178-4

Li, Y., Zhao, J., and Hölscher, C. (2017). Therapeutic potential of baicalein in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 31 (8), 639–652. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0451-y

Li, Z., , Jiang, T., Lu, Q., Xu, K., He, J., Xie, L., et al. (2020). Berberine attenuated the cytotoxicity induced by t-BHP via inhibiting oxidative stress and mitochondria dysfunction in PC-12 cells. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 40 (4), 587–602. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00756-7

Liang, J., Wu, Y., Yuan, H., Yang, Y., Xiong, Q., Liang, C., et al. (2019). Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides attenuate learning and memory disabilities via anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules. 126, 414–426. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.230

Liao, S. F., Wang, H. T., Yan, F. X., Zheng, Y. X., Zeng, Z. W., Zheng, W. H., et al. (2014). [Protective effect and mechanisms of dihydromyricetin on PC12 cells induced by oxidative injury]. Zhong Yao Cai 37 (6), 1014–1020.

Liu, W., Zhai, Y., Heng, X., Che, F. Y., Chen, W., Sun, D., et al. (2016). Oral bioavailability of curcumin: problems and advancements. J. Drug Target. 24 (8), 694–702. doi:10.3109/1061186x.2016.1157883

Zhu, Q., Zhuang, X., and Lu, J. (2019). Neuroprotective effects of baicalein in animal models of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review of experimental studies. Phytomedicine. 55, 302–309. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.215

Liying, Y., Hongyan, W., Lijun, L., and Anmu, X. (2018). The role of insulin/IGF-1/PI3K/Akt/GSK3β signaling in Parkinson’s disease dementia. Front. Neurosci. 12, 73. doi:doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00073

Lu, D.-S., Chen, C., Zheng, Y.-X., Li, D.-D., Wang, G.-Q., Liu, J., et al. (2018). Combination treatment of icariin and L-DOPA against 6-OHDA-lesioned dopamine neurotoxicity. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11, 155. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2018.00155

Lu, Q., Zhu, H., Liu, X., and Tang, C. (2020). Icariin sustains the proliferation and differentiation of Aβ25-35-treated hippocampal neural stem cells via the BDNF-TrkB-ERK/Akt signaling pathway. Neurol. Res. 42 (11), 936–945. doi:10.1080/01616412.2020.1792701

Lulin, N., Junxia, X., Honglian, L., Zaijun, Z., Ying, Y., Xinfeng, H., et al. (2017). Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates behavioral abnormalities and modulates the hippocampal proteomic change in triple transgenic mice of Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid Med. Cel Longev. 2017, 1–17. doi:10.1155/2017/6473506

Luo, S., Kang, S. S., Wang, Z.-H., Liu, X., Day, J. X., Wu, Z., et al. (2019). Akt phosphorylates NQO1 and triggers its degradation, abolishing its antioxidative activities in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 39 (37), 7291–7305. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0625-19.2019

Ma, B., Meng, X., Wang, J., Sun, J., Ren, X., Qin, M., et al. (2014). Notoginsenoside R1 attenuates amyloid-β-induced damage in neurons by inhibiting reactive oxygen species and modulating MAPK activation. Int. Immunopharmacology. 22(1), 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2014.06.018

Ma, X.-W., and Guo, R.-Y. (2017). Dose-dependent effect of Curcuma longa for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 13 (5), 1799–1805. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4225

Mario, P. M., Jorge, M. F., Cesar, R. T., and Mcarmen, R. T. (2016). Curcumin and health. Molecules 21 (3), 264. doi:10.3390/molecules21030264

Martins, A. C., Morcillo, P., Ijomone, O. M., Venkataramani, V., Harrison, F. E., Lee, E., et al. (2019). New insights on the role of manganese in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16 (19), 3546. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193546

Matsuda, S., Ikeda, Y., Murakami, M., Nakagawa, Y., Tsuji, A., Kitagishi, Y., et al. (2019). Roles of PI3K/AKT/GSK3 pathway involved in psychiatric illnesses. Diseases. 7 (1), 22. doi:10.3390/diseases7010022

Matsuo, F. S., Andrade, M. F., Loyola, A. M., da Silva, S. J., Silva, M. J. B., Cardoso, S. V., et al. (2018). Pathologic significance of AKT, mTOR, and GSK3β proteins in oral squamous cell carcinoma-affected patients. Virchows Arch. 472, 983. doi:10.1007/s00428-018-2318-0

Memmott, R. M., and Dennis, P. A. (2009). Akt-dependent and -independent mechanisms of mTOR regulation in cancer. Cell Signal. 21 (5), 656–664. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.004

Meng, X., Sun, G., Ye, J., Xu, H., Wang, H., Sun, X., et al. (2014). Notoginsenoside R1-mediated neuroprotection involves estrogen receptor-dependent crosstalk between Akt and ERK1/2 pathways: a novel mechanism of Nrf2/ARE signaling activation. Free Radic. Res. 48 (4), 445. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.885117

Mengqiu, S., Ann, B., Zigang, D., and Mee-Hyun, L (2019). AKT as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cancer Res. 79, 1019. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2738

Ming, H., Fangming, L., and Weidong, W. (2018). Vitexin protects dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 12, 565–573. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S156920

Mirdamadi, Y., Bommhardt, U., Goihl, A., Guttek, K., Zouboulis, C. C., Quist, S., et al. 2017). Insulin and Insulin-like growth factor-1 can activate the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt/FoxO1 pathway in T cells in vitro. Dermato-Endocrinology 9(1), e1356518. doi:10.1080/19381980.2017.1356518

Mirzaei, H., Shakeri, A., Rashidi, B., Jalili, A., Banikazemi, Z., Sahebkar, A., et al. (2017). Phytosomal curcumin: a review of pharmacokinetic, experimental and clinical studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 85, 102–112. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.098

Mu, S., Li, Y., Liu, B., Wang, W., Chen, S., Wu, J., et al. (2016). Dihydromyricetin ameliorates 3NP-induced behavioral deficits and striatal injury in rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 60, 267. doi:10.1007/s12031-016-0801-0

Nataraj, J., Manivasagam, T., Justin Thenmozhi, A., and Essa, M. M. (2017). Neurotrophic effect of asiatic acid, a triterpene of Centella asiatica against chronic 1-methyl 4-phenyl 1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine hydrochloride/probenecid mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: the role of MAPK, PI3K-Akt-GSK3β and mTOR signalling pathways. Neurochem. Res. 42 (5), 1354–1365. doi:10.1007/s11064-017-2183-2

Parkinson, G. T., and Hanley, J. G. (2018). Mechanisms of AMPA receptor endosomal sorting. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2018.00440