94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol., 15 July 2020

Sec. Neuropharmacology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01078

Opioids are the most effective analgesics used in the clinical management of cancer pain or non-cancer pain. However, chronic opioids therapy can cause many side effects including respiratory depression, nausea, sedation, itch, constipation, analgesic tolerance, hyperalgesia, high addictive potential, and abuse liability. Opioids exert their effects through binding to the opioid receptors belonging to the G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) family, including mu opioid receptor (MOR), delta opioid receptor (DOR), and kappa opioid receptor (KOR). Among them, MOR is essential for opioid-induced analgesia and also responsible for adverse effects of opioids. Importantly, MOR can form heterodimers with other opioid receptors and non-opioid receptors in vitro and in vivo, and has distinct pharmacological properties, different binding affinities for ligands, downstream signaling, and receptor trafficking. This mini review summarized recent progress on the function of Mu opioid receptor heterodimers, and we proposed that targeting mu opioid receptor heterodimers may represent an opportunity to develop new therapeutics, especially for chronic pain treatment.

Chronic pain is a distressing and debilitating disease, which affects one-third of the population worldwide (Basbaum et al., 2009). Opioids such as morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, fentanyl, and tramadol, are considered the most effective analgesics used in the clinical management of chronic pain, which are among the most commonly prescribed and frequently abused drugs in the US (Ballantyne and Mao, 2003; Dart et al., 2015; Skolnick, 2018). However, opioids also cause many side effects associated with their acute use (including respiratory depression, nausea, sedation, itch, and constipation) and prolonged use (analgesic tolerance, hyperalgesia, high addictive potential and abuse liability) (Ballantyne and Mao, 2003; Schuckit, 2016). Rewarding and euphoric properties of opioids significantly contribute to their abuse potential (Darcq and Kieffer, 2018). Opioid tolerance is defined as a reduction in effect following prolonged drug administration that results in a loss of drug potency, resulting in the need to increase the opioids dosage to maintain the initial effects (Mao et al., 1995). Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) refers to the development of hypersensitivity to painful stimuli during chronic opioids administration (Mao et al., 1995; Roeckel et al., 2016). Opioid tolerance and OIH are considered to significantly contribute to opioid epidemic worldwide (Skolnick, 2018). These adverse effects of opioid dramatically reduce the quality of life of those patients with chronic pain (Ballantyne and Mao, 2003; Volkow and McLellan, 2016). On the other hand, opioid abuse and opioid overdoses in the US exceed 45,000 deaths per annum, representing the major cause of accidental deaths (Dart et al., 2015; Blendon and Benson, 2018). Although opioid receptor antagonists (such as naltrexone and naloxone) can lessen addictive impulses and facilitate recovery from opioid overdose, opioid antagonists also have severe side effects due to the disruption of endogenous opioid system (Boyer, 2012). Since misuse and/or abuse prescribed opioid drugs reach epidemic levels, designing new effective opioid analgesics without side effects may provide an important strategy against this opioid crisis (Blendon and Benson, 2018).

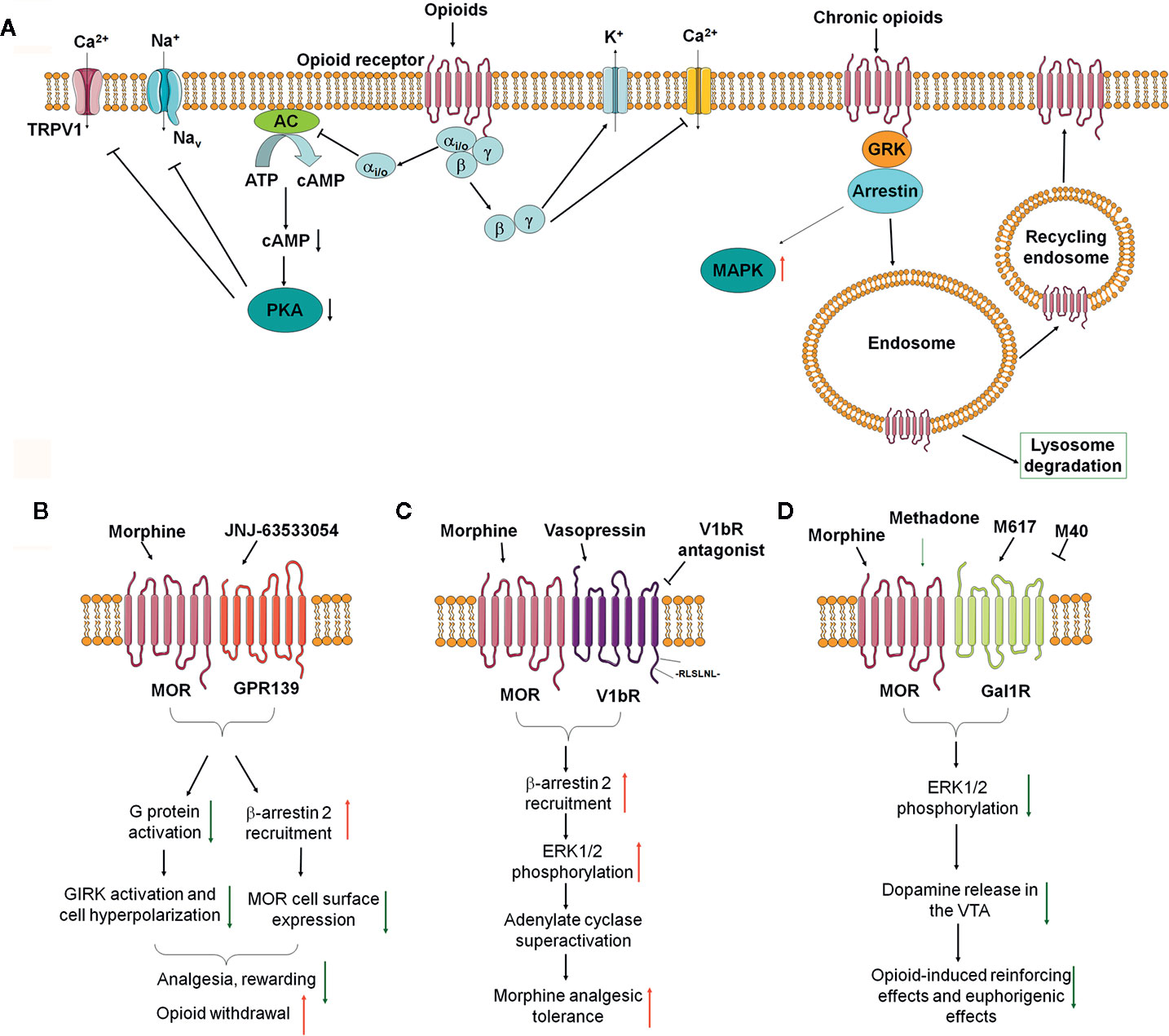

Opioids exert their effects through binding to the opioid receptors belonging to the G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) family, including μ-opioid receptor (MOR), δ-opioid receptor (DOR), and κ-opioid receptor (KOR) (Stein, 2016). After binding of a ligand, opioid receptors activate intracellular pertussis toxin-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi/o protein to dissociate into Gαi/o and Gβγ subunits, which initiate downstream signaling. Gαi/o inhibits adenylyl cyclases and cAMP production, and protein kinase A (PKA), resulting in modulating ion channels in the membrane, such as inhibition of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) and voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) (Machelska and Celik, 2018). Gβγ blocks calcium channels and opening of potassium channels, including G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels and adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) (Figure 1A). Opioids attenuate neuronal excitability and excitatory neurotransmitters release from presynaptic terminals, which contribute to opioid-induced analgesia. Opioid receptors can be phosphorylated by GPCR kinases (GRKs) to promote the binding of β-arrestins, leading to opioid receptors desensitization and receptor internalization through clathrin-dependent pathways, resulting in reduced cell surface expression (Darcq and Kieffer, 2018). Dephosphorylated opioid receptors can then be recycled to the plasma membrane, or targeted into lysosome for degradation (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 The impact of opioid receptor heterodimerization on opioid receptor signaling, trafficking, and behavioral outcomes. (A) Classical opioid receptor signaling pathways. (B–D) Recent identified opioid receptor heterodimers and downstream signaling in the nervous system and their effects on opioid side effects, including MOR-GPR139 (B), MOR-V1bR (C), and MOR-GalR1 (D).

Opioid receptors are expressed by many types of cells, including neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system, neuroendocrine cells, immune cells, and ectodermal cells (Stein, 2016; Machelska and Celik, 2020). Thus, opioid receptors are required and are driver for the production of many adverse effects following prolonged opioid therapy (Darcq and Kieffer, 2018; Machelska and Celik, 2018). For example, MOR is essential for opioid-induced analgesia and also responsible for many adverse effects of opioids, including tolerance, hyperalgesia, respiratory depression, constipation, nausea, and reward/euphoria that may lead to addiction (Darcq and Kieffer, 2018; Kibaly et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). In addition, chronic opioid treatment may cause complex maladaptive responses, including downregulation of the opioid receptors, activation of anti-opioid systems, altering neuronal circuitry, activation of glial cells (including microglia and astrocytes), and even gut microbiota dysbiosis (Hutchinson et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2019).

Many family-A GPCRs are found to be able to form receptor heterodimers, including opioid receptors (Ferré et al., 2014; Ferré, 2015; Gomes et al., 2016). Heterodimers represent another important layer of functional complexity of opioid receptors and provide additional opportunity for modulating the function of opioid receptors (Machelska and Celik, 2018). Opioid receptor heterodimers can form between opioid receptors (Li-Wei et al., 2002) or between opioid receptors and non-opioid receptors (Jordan and Devi, 1999; Costantino et al., 2012). For example, it has been revealed that opioid receptor heterodimers exist in vitro and in vivo, including MOR-MOR homodimers (Li-Wei et al., 2002), MOR-DOR heterodimers (Costantino et al., 2012), MOR-KOR heterodimers (Chakrabarti et al., 2010), and DOR-KOR heterodimer (Jordan and Devi, 1999), MOR1D-Gastrin Releasing Peptide Receptor (GRPR) heterodimer (Liu X. Y. et al., 2011), MOR-cholecystokinin B receptor (CCKBR) heterodimer (Tao et al., 2017), MOR-cannabinoid 1(CB1) heterodimer (Rios et al., 2006), MOR-chemokine receptor 5(CCR5) heterodimer (Suzuki et al., 2002), MOR-α2A adrenergic receptor (α2AAR) heterodimer (Vilardaga et al., 2008), MOR-dopamine D1 heterodimer (Tao et al., 2017), and MOR-nociceptin receptor heterodimer (Costantino et al., 2012). The formation of different types of opioid receptor heterodimers through allosteric mechanisms over the receptor interface may alter pharmacological properties of opioid ligands and may produce additional pharmacological subtypes. In addition, opioid receptor heterodimers may also have dramatic impact on opioid receptor trafficking and downstream signaling. Given opioid receptor heterodimers are often expressed on specific and limited brain regions and involved in many adverse effects induced by chronic opioid therapy, targeting opioid receptor heterodimers and subsequent downstream signaling may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of chronic pain and adverse effects of opioids.

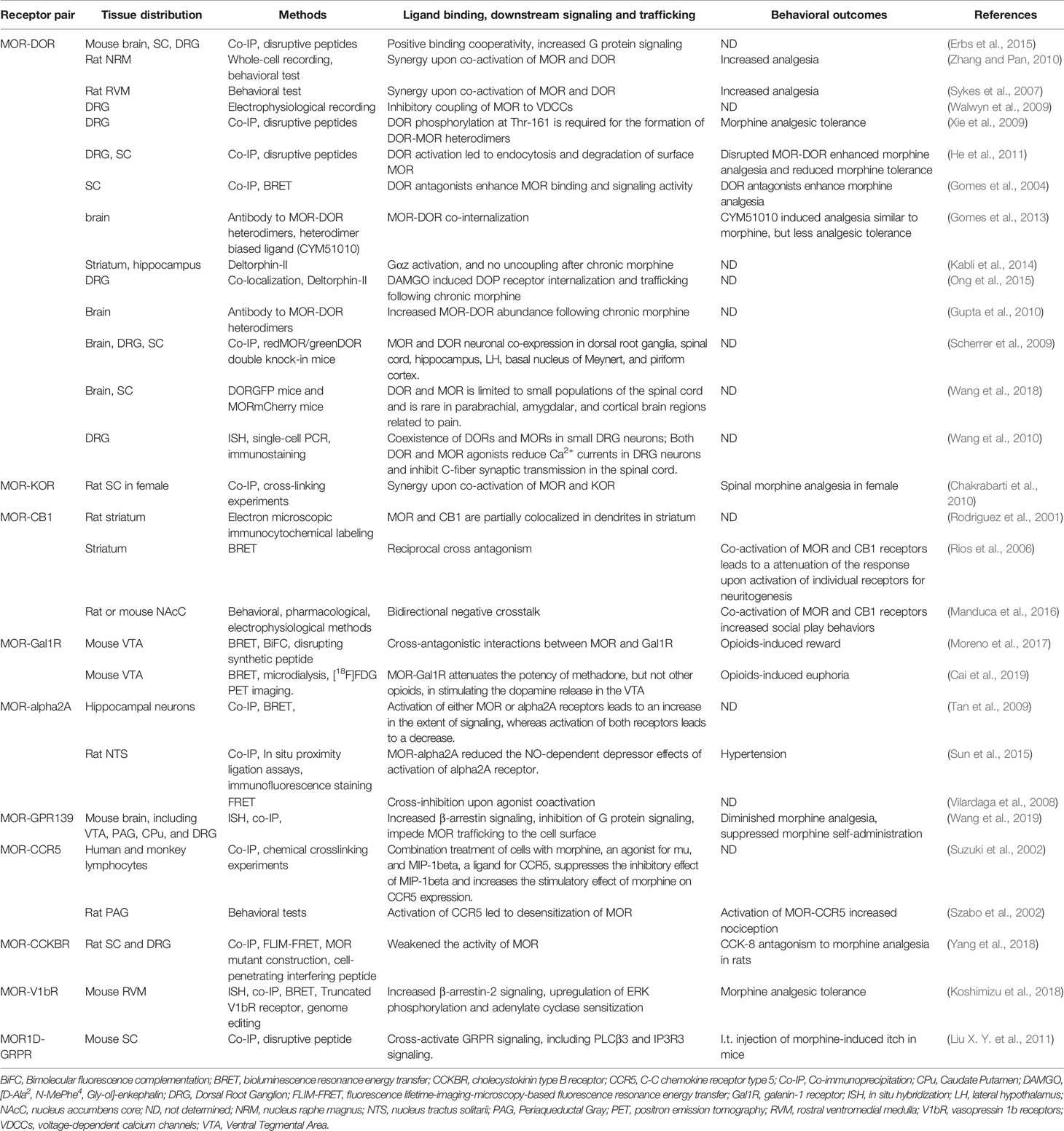

Accumulating evidence demonstrated that mu opioid receptor can form heterodimers with other opioid receptors or non-opioid receptors in vitro and in vivo, which have distinct pharmacological properties, different binding affinities for ligands, distinct downstream signaling, and trafficking (Jordan and Devi, 1999; Gomes et al., 2011; Ugur et al., 2018). In this mini review article, we highlighted the recent identified mu opioid receptor heterodimers, their pharmacological properties, and downstream signaling, and their involvement in pathological conditions (Table 1). We finally discussed the potential therapeutic potentials by targeting these opioid receptor heterodimers, especial for chronic pain management.

Table 1 Identification, downstream signaling, and function of Mu opioid receptor heterodimers in vitro and in vivo.

To date, among all MOR heterodimers, MOR-DOR heterodimer is the most importantly known and proven to exist both in vitro and in vivo. Several agonists and antagonists selective for MOR-DOR heterodimer have been identified and synthesized (Olson et al., 2018). George et al. reported that the MOR and DOR may form heterodimer when they were co-expressed in vitro, and selective agonists for each receptor had reduced potency (George et al., 2000; Gomes et al., 2013). By using co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), it was demonstrated that physical interactions between MOR and DOR upon co-expression in vitro (Gomes et al., 2004; Yekkirala et al., 2012). It was reported that MOR agonist DAMGO activates Gαi/o-mediated signaling in MOR-expressing cells while activates β-arrestin 2 for changing the dynamics of ERK-mediated signaling in MOR-DOR heterodimer-expressing cells (Rozenfeld and Devi, 2007). DOR selective agonist SNC80 induced intracellular calcium release only in MOR-DOR heterodimers expressing cells by using a chimeric G-protein-mediated calcium fluorescence assay (Metcalf et al., 2012). CYM51010, a MOR-DOR heterodimer selective agonist, induced recruitment of β-arrestin 2 and GTPγS binding, which was blocked by a MOR-DOR heterodimer selective antibody (Gomes et al., 2013). The delta opioid receptor (DOR) exerts an antagonistic allosteric influence on MOR function within a MOR-DOR heterodimer. DOR antagonist enhances MOR recognition, Gi/o coupling and inhibition of cAMP levels (Gomes et al., 2004). Thus, these results suggested that MOR-DOR heterodimer affected the pharmacological properties of each receptor.

MOR-DOR heterodimer may also have distinct intracellular trafficking. Previous study showed that MOR and DOR can form heterodimers only when they are present at plasma membrane (Milan-Lobo and Whistler, 2011). In contrast, another study showed that MOR-DOR heterodimers located in the endoplasmic reticulum, where they recruit protein (Hasbi et al., 2007). Some agonists (e.g. DAMGO, Deltorphin II, SNC80, and methadone) can induce MOR-DOR heterodimer endocytosis, but others (e.g. DADPE) cannot do so (Décaillot et al., 2008). In addition, RTP4, a Golgi chaperone, was identified as a key regulator of the levels of MOR-DOR heterodimers at the cell surface (Décaillot et al., 2008). It was also found that treatment with DOR agonists led to endocytosis of both DORs and MORs, further processed for degradation, resulting in a reduction of surface expression of MOR (He et al., 2011). These effects were attenuated by treatment with an interfering peptide that disrupted the MOR-DOR heterodimer formation (He et al., 2011).

MOR-DOR heterodimers are also demonstrated to distribute in central nervous system and play key roles in the regulation of pain and opioid analgesia. RedMOR/greenDOR double knock-in mice were generated to perform dual receptor mapping throughout the whole brain (Erbs et al., 2015). In the forebrain, MOR and DOR are mainly detected in separate population of neurons. In contrast, neuronal co-localization is detected in subcortical networks, which is essential for eating, sexual behaviors or response to aversive stimuli (Erbs et al., 2015). Recently, it was found that MOR and DOR co-expression is limited to small populations of neurons in the spinal cord. MOR and DOR co-expression is rare in parabrachial, amygdala, and cortical brain regions for pain processing (Wang et al., 2018). By using antibodies selective for MOR-DOR heterodimers generated by subtractive immunization strategy, it was found that up-regulation of MOR-DOR heterodimers were induced by chronic morphine treatment (Gupta et al., 2010). Tail-flick assay showed that CYM51010 targeting the MOR-DOR heterodimer demonstrated analgesic activity comparable to morphine, and chronic administration of CYM51010 resulted in less analgesic tolerance (Gomes et al., 2013). Recently, it was found that MOR-DOR heterodimer expression was up-regulated in injured dorsal root ganglia neurons and subcutaneous injection of CYM51010 inhibited neuropathic pain in rats and mice (Tiwari et al., 2020). Intriguingly, the CYM51010-induced analgesia still persisted in morphine-tolerant rats and was abolished in MOR knockout mice (Tiwari et al., 2020). In addition, intrathecal administration of a peptide to disrupt the formation of MOR-DOR heterodimers can enhance morphine analgesia and reduce analgesic tolerance in mice (He et al., 2011). Together, these results indicated that targeting MOR-DOR heterodimers may be a promising strategy to treat chronic pain or to improve therapeutic effects of opioids.

Chakrabarti et al. (2010) found that the expression of MOR-KOR heterodimer was more prevalent in the spinal cord of proestrous vs. diestrous females and vs. males. Spinal morphine anti-nociception in females, but not males, required the concomitant activation of MOR and KOR in the spinal cord. Dynorphine was identified as a ligand for female-specific KOR within the MOR-KOR heterodimer. Co-IP experiments obtained with anti-KOR antibodies on the spinal cord showed that it is elevated in proestrus with high estrogen receptor (ER) levels (Liu N. J. et al., 2011). The gender- and ovarian steroid-dependent recruitment of MOR-KOR heterodimers may provide a way to influence the balance between anti-nociceptive and pro-nociceptive functions of the dynorphin/KOR opioid system in the spinal cord. Impaired formation of MOR-KOR heterodimers could be a biological determinant of various types of chronic pain states that are substantially more common in women than men. Thus, MOR-KOR may be therapeutic target for pain control, especial in women.

Recently, Wang et al. (2019) identified a conserved orphan GPR139 receptor as a novel partner to form MOR-GPR139 heterodimers to negative regulate opioid receptor function and demonstrated that GPR139 can regulate opioid receptor signaling and trafficking. Firstly, Wang et al. (2019) established an ingenious forward genetic platform by using a model organism, C. elegans to screen mutations that affect opioid receptor function and signaling. Following the expression of mammalian MOR in the nervous system of nematodes (tgMOR), administration of morphine and fentanyl decreased locomotion in tgMOR nematodes. Based on the drug sensitivity of behavioral responses, they conducted a large-scale forward genetic screening of the transgenic nematode, and 900 mutants with altered opioid sensitivity were observed. By whole genome sequencing of these mutants, they identified an orphan receptor FRPR-13 (its homologous protein GPR139 in mammals) as a negative regulator of MOR function in vivo.

Wang et al. (2019) further investigated the functional interaction of MOR and GPR139 in transfected HEK cells. In transfected HEK293T cells, MOR activation causes hyperpolarization of membrane potential due to opening of the G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs) and expression of GPR139 inhibited these abovementioned effects. They showed that GPR139 and MOR can be co-immunoprecipitated in artificially overexpressed in a cellular context. When GPR139 is overexpressed at high amounts, they found that cell surface expressed MOR was reduced, suggesting that GPR139 may regulate MOR trafficking to the cell surface or its internalization. In vitro, GPR139 was further found to bind directly to MOR, promote the recruitment of β-arrestin 2, and inhibited the activation of G protein and GIRK channel. In situ hybridization experiments showed that GPR139 and MOR are expressed in the same brain regions, including the medial habenula (MHb) and locus coeruleus (LC). Wang et al. (2019) further provided electrophysiological evidence to support the functional interaction of MOR and GPR139. In cultured brain slices, GPR139 deficiency reduced the basal firing rate of MHb neurons and increased opioid sensitivity of LC neurons. Thus, it was concluded that GPR139 regulates the function of MOR in a cell-autonomous manner.

Wang et al. (2019) finally investigated the role of GPR139 in morphine-induced behavioral changes in mice. They observed that GPR139 knockout (KO) mice had normal baseline learning, nociception, locomotor activities, and motor coordination. However, GPR139 KO mice showed enhanced sensitivity to morphine-induced analgesia and reward effects. Administration of GPR139 agonists JNJ-63533054 inhibited morphine-induced analgesia and morphine-induced reward in mice. GPR139 KO mice also showed significantly diminished opioid withdrawal reactions (Figure 1B). Thus, these data indicate that inhibiting the function of GPR139 enhanced sensitivity to morphine-induced analgesia and reward effects, but diminished morphine withdrawal, while facilitating the function of GPR139 diminished morphine analgesia and rewarding effects. However, the formation and function of MOR-GPR139 heterodimers were only investigated in vitro. The precise localization and function of MOR-GPR139 heterodimers in vivo warrant further validation and investigation. Given GPR139 was identified as a novel anti-opioid system, brain regions selective targeting GPR139 or MOR-GPR139 heterodimers may be useful to improve the safety and efficacy of opioids.

Recently, Koshimizu et al. (2018) identified vasopressin 1b receptor (V1bR) as another partner to form MOR-V1bR heterodimers in promoting AC superactivation and the development of morphine tolerance, which is another excellent example that opioid receptor heterodimers may alter the opioid receptor signaling and function. Arginine-vasopressin (AVP), structurally related to oxytocin, are known to regulate morphine sensitivity and tolerance. However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Koshimizu et al. (2018) first found that V1bR knockout (KO) mice showed enhanced nociceptive thresholds and greater morphine sensitivity. In addition, the development of morphine tolerance was significantly delayed in V1bR KO mice. Next, they found that administration of selective V1bR antagonist SSR149415 (but not V1aR antagonist) into lateral ventricle of mice also reduced the development of morphine tolerance in mice. By using in situ hybridization analysis, they subsequently found that V1bR and MOR are co-localized in the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM). They further examined the functional interaction between V1bR and MOR by using HEK cell co-expressing V1bR and MOR. In a single cell, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) analysis confirmed that V1bR and MOR were located in close proximity (<10 nm). Binding experiments indicate that morphine binding to the MOR is substantially influenced by forming MOR-V1bR heterodimer in the cellular environment. AVP enhanced morphine-induced AC superactivation in the setting of V1bR-MOR heterodimers, which depends on β-arrestin 2 and extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation pathways. A leucine-rich segment in the C-terminal tail of the V1bR is essential for association with β-arrestin 2. Finally, they showed that deletion of the leucine-rich segment in the V1bR C-terminal tail by genome editing increased morphine analgesia and reduced AVP-mediated AC superactivation (Figure 1C). Altogether, it was proposed that targeting MOR-V1bR may be a novel approach for potentiating morphine analgesia with delayed development of morphine tolerance.

Previous studies showed that a neuropeptide galanin counteracts the behavioral effects of MOR agonists in vivo. Moreno et al. (2017) identified the formation of MOR-Gal1R heterodimer in transfected cells and in neurons in rat ventral tegmental area (VTA). MOR-Gal1R heterodimer plays a key role in the function of dopaminergic neurons and mediates the antagonistic interactions between MOR and Gal1R selective ligands (Moreno et al., 2017). Cai et al. (2019) further found an agonist-dependent function of MOR-Gal1R heterodimers and elucidated the mechanisms underlying opioid-induced rewarding, suggesting the formation of opioid receptor heterodimers may alter the pharmacological properties of opioid receptor. It was showed that MOR-GalR1 heterodimers in the rat VTA reduced the potency of methadone, but not other opioids (e.g. morphine and fentanyl), for stimulating dopamine release and producing euphoria (Figure 1D). Thus, these pharmacodynamic differences between methadone and morphine may provide a way to dissociate the euphoric versus therapeutic effects of methadone-like compounds. Consistently, patients on methadone maintenance experienced fewer euphoria compared with those using other opioids (Cai et al., 2019). Thus, these data indicated MOR-GalR1 heterodimers mediate the dopaminergic effects of opioids and novel methadone-like compounds with reduced potency to activate MOR-GalR1 heterodimers may be safer than current opioids. Given the critical role of MOR-GalR1 heterodimers in the determination of the potency of opioid-induced activation of rewarding pathways and restricted distribution of MOR-GalR1 heterodimers in the VTA, MOR-GalR1 heterodimers may be a promising target to develop safer opioid analgesics or even treat opioid addiction.

CB1 receptor is present in the peripheral and central nervous system, including primary sensory neurons in the DRGs, the spinal cord, and some brain regions related to pain processing (Bouchet and Ingram, 2020). Early study showed co-localization of CB1 and MOR in lamina II neurons in the spinal cord (Salio et al., 2001), and synergistic interactions also existed between cannabinoid and opioid analgesia (Raehal and Bohn, 2014). By using biophysical methods, Rios et al. demonstrated that CB1 can form heterodimers with MOR in transfected cells (Rios et al., 2006). Co-activation of MOR-CB1 leads to cross-inhibition of neurite outgrowth involving inhibition of the Src-STAT3 pathway, suggesting antagonistic allosteric interactions in CB1-MOR heterodimers (Rios et al., 2006). Thus, MOR-CB1 heterodimer may be a target to modulate neuronal plasticity.

Previous studies found the antagonism of cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK8) to opioid analgesia (Pu et al., 1994), and studies using L-365,260 (a specific antagonist of CCKBR) showed that CCK-8 inhibited opioid analgesia through CCKBR (Dourish et al., 1990). Recently, Yang et al. (2018) demonstrated that MOR and CCKBR could form heterodimer and MOR-CCKBR heterodimer may underlie the antagonism of CCK8 to opioid analgesia. They first validated the co-localization of MOR and CCKBR in neurons in spinal cord dorsal horn and the DRGs by using double-labeling immunofluorescence staining. By using co-IP and FLIM-FRET methods, they further validated that CCKBR and MOR form heterodimers in transfected HEK293 cells and the transmembrane domain 3 (TM3) domain of MOR play a key role in the formation of MOR-CCKBR heterodimers. Further, the formation of MOR-CCKBR heterodimer leads to decreased MOR affinity and reduced agonist-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in transfected HEK293 cells. They developed a cell-penetrating interfering peptide (TM3MOR-TAT) by adding the TAT sequence (RKKRRQRRR) to the C terminal of the entire TM3, in order to disrupt the formation of MOR-CCKBR heterodimer. Finally, they found that TM3MOR-TAT enhanced MOR signaling in transfected cells and prevented CCK8-induced antagonism against morphine analgesia in rats. Thus, MOR-CCKBR may be a promising therapeutic target for enhancing morphine analgesia.

Previous study showed that there exists a conformational antagonistic crosstalk between α2AAR and MORs in their downstream signaling upon co-activation (Vilardaga et al., 2008). Yang et al. (2018) demonstrated that these receptors, either singly or as a heterodimer, activate common signal transduction pathways mediated through the inhibitory Gαi/o. Using FRET microscopy, they showed that within the MOR-α2AAR heterodimer, the MOR and α2AAR communicate with each other through a cross-conformational switch that permits direct inhibition of one receptor by the other (Vilardaga et al., 2008). It was also found that morphine binding to the MOR triggers a conformational change in the norepinephrine-occupied α2AAR that inhibits its signaling to Gαi and the downstream MAP kinases (Vilardaga et al., 2008). These data highlight a new mechanism in signal transduction whereby a G protein-coupled receptor heterodimer mediates conformational changes that propagate from one receptor to the other and cause the second receptor's rapid inactivation. Thus, these results suggest that activation of MOR-α2AAR heterodimers by combined agonists for each other could play a role in counteracting excessive analgesia.

However, early work indicates that combined agonists acting on α2AAR and opioid receptors have analgesic properties and act synergistically when co-administered in the spinal cord (Stone et al., 1997). Norepinephrine (NE) or clonidine (α2AAR agonists) significantly reduces the evoked release of glutamate from spinal cord synaptosomes (Kamisaki et al., 1993) and the release of substance P (SP) and calcitonin gene related peptides (CGRP) from spinal cord slices (Bourgoin et al., 1993). In addition, immunostaining data showed that both α2AAR and MOR was observed in the superficial layers of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the primary localization of the α2AAR in the rat spinal cord is on the terminals of capsaicin-sensitive, SP-containing primary afferent fibers (Bourgoin et al., 1993). Thus, although α2AAR and MOR may co-localized on these primary afferent fiber terminals, the formation of MOR-α2AAR heterodimer cannot explain the synergy of agonists of MOR and α2AAR in analgesia.

The mouse Oprm gene encodes 16 exons, comprising dozens of spliced isoforms that primarily differ at C terminus (Pasternak and Pan, 2013). Liu X. Y. et al. (2011) demonstrated one MOR isoform MOR1D is co-expressed with GRPR in superficial layers of the spinal cord in mice. Further, MOR1D was shown to be associated with GRPR to form MOR1D-GRPR heterodimer in the spinal cord (Liu X. Y. et al., 2011). Activation of MOR1D unidirectionally cross-activates GRPR and its downstream effectors (such as PLC3β and IP3R3) in neurons of spinal cord. Blocking the formation of MOR1D-GRPR by a disrupted peptide attenuated morphine-induced itch, but did not affect morphine-induced analgesia in mice (Liu X. Y. et al., 2011). Thus, the results indicated that MOR1D-GRPR may be a promising therapeutic target for treating morphine-induced itch, which is a remarkable side effect of morphine.

In order to design new opioid analgesics without side effects, we need to better understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the regulation of MOR function. So far, it is proposed several different strategies to achieve this goal (Machelska and Celik, 2018). For example, one strategy is selective targeting MOR splice variants that are selective involved in analgesia. Another strategy is the biased activation of MOR towards analgesia-associated intracellular signaling pathways. Third strategy is selective targeting MOR at peripheral nervous system though reducing opioid access to the central nervous system. Fourth strategy is selective targeting MOR in peripheral inflamed tissue. Fifth strategy is identification of compounds that specific target opioid receptor heterodimers. Heterodimers are defined as a protein complex composed of two functional receptor units (protomers) and have different biochemical and pharmacological properties than individual units. This research highlight will introduce some recent progress about opioid receptor heterodimers and discussed the abovementioned fifth strategy to design new generation of opioid analgesics with few side effects.

So far, there are several innovation strategies to design new compounds for targeting opioid receptor heterodimers, aiming at improving analgesic and reducing side effects. First, bivalent ligands can be designed for targeting opioid receptor heterodimers, which may be designed through using a 21-22-atom spacer to connect MOR agonist and other receptor antagonist involved in heterodimers. Accordingly, for example, MMG22 was designed to target MOR-mGluR5 heterodimers, which consists oxymorphamine (MOR agonist) and metoxy-2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (mGluR5 antagonist) connected by a 22-atom spacer. Second, monovalent compounds were also developed to target opioid receptor heterodimers. For example, N-naphthoyl-β-naltrexamine (NNTA) with mixed KOR agonist/MOR antagonist was designed to target MOR-KOR heterodimers, which produced analgesia, little tolerance, and little withdrawal signs. Third, multifunctional ligands can also be designed to target opioid receptor heterodimers. For example, TY027 with MOR/DOR agonistic and NK1 receptor antagonistic activities produced analgesia, little tolerance, less reward, less withdrawal signs, no effects on gastrointestinal transit in preclinical animal models. Finally, combination of two compounds for targeting opioid receptor heterodimers is another choice. For example, combination of MOR agonist and V1bR antagonist (SSR149415) to target MOR-V1bR heterodimers produced analgesia with little tolerance. Additionally, combination of Gal1R agonist and MOR agonist may be used to reduce euphoric effects of opioids. Thus, bivalent, monovalent, and multifunctional ligands or combination of two drugs targeting opioid receptor heterodimers may represent next generation of pain killers with reduced side effects.

Although scientists have made great progress in promoting our understanding on the function of opioid receptor heterodimers, there are many questions that remain to be resolved. First, the existence and physiological/pathophysiological function of opioid receptor heterodimers in vivo remains largely unknown, including recent identified MOR-GPR139 heterodimers. Second, the studies on the structure and function of opioid receptor heterodimers is very challenging and more powerful research tools need to be developed. Of note, the current methods heavily rely on the heterologous expressing cells and antibodies, which often have specificity issues. Importantly, the application of x-ray crystallography and/or cryo-electron microscopy may be helpful to provide structural basis for the formation of opioid receptor heterodimers and the interaction between selective ligands and heterodimers. Additionally, the generation of mutant mouse expressing fluorescently tagged MOR and its partners within heterodimers will be useful to explore the distribution of opioid receptor heterodimers in vivo, avoiding the specificity issue of antibodies. Of course, to develop antibodies specific for opioid receptor heterodimers is another way. Third, the expression of opioid receptor heterodimers in an endogenous context may be highly dynamic. Fourth, opioid receptors may form heteromers with ion channels, such as NMDA receptor (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2012) and TRPV1 receptor (Scherer et al., 2017), and these kind of heteromers may have distinct function in physiological and pathophysiological conditions. However, this topic is out of the scope of this review. Together, the expression and the interaction changes of opioid receptor heterodimers in many pathological conditions (including chronic opioid treatment and many pathological pain conditions) warrant further investigation. Finally, in order to identify the compounds with specific target opioid receptor heterodimers, the high-throughput screening assays have to be established.

Opioid receptor heterodimers regulate the opioid receptor function at multiple levels, including pharmacodynamic of ligands, the receptor trafficking, and intracellular downstream signaling pathways. Impressively, the list of opioid receptor heterodimers is growing rapidly. There are also several innovation strategies or high-throughput screen platform to be developed in order to targeting opioid receptor heterodimers. Thus, the identification and characterization of MOR heterodimers may provide valuable therapeutic targets for chronic pain and improving opioid analgesics.

LZ and J-TZ performed literature search and prepared the draft. LH and TL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

TL is supported by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870874), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK20170004 and 2015-JY-029), and Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Neuropsychiatric Diseases (BM2013003). This work was also financed by the Clinical and basic research of encephalopathy (KYC004) and the Social Development Special Fund of Kunshan (KS1931).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ballantyne, J. C., Mao, J. (2003). Opioid therapy for chronic pain. New Engl. J. Med. 349, 1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411

Basbaum, A. I., Bautista, D. M., Scherrer, G., Julius, D. (2009). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139, 267–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028

Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M. (2018). The Public and the Opioid-Abuse Epidemic. New Engl. J. Med. 378, 407–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714529

Bouchet, C. A., Ingram, S. L. (2020). Cannabinoids in the descending pain modulatory circuit: Role in inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 209, 107495. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107495

Bourgoin, S., Pohl, M., Mauborgne, A., Benoliel, J. J., Collin, E., Hamon, M., et al. (1993). Monoaminergic control of the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide- and substance P-like materials from rat spinal cord slices. Neuropharmacology 32, 633–640. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90076-F

Boyer, E. W. (2012). Management of opioid analgesic overdose. New Engl. J. Med. 367, 146–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202561

Cai, N. S., Quiroz, C., Bonaventura, J., Bonifazi, A., Cole, T. O., Purks, J., et al. (2019). Opioid-galanin receptor heteromers mediate the dopaminergic effects of opioids. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 2730–2744. doi: 10.1172/JCI126912

Chakrabarti, S., Liu, N. J., Gintzler, A. R. (2010). Formation of mu-/kappa-opioid receptor heterodimer is sex-dependent and mediates female-specific opioid analgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 20115–20119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009923107

Costantino, C. M., Gomes, I., Stockton, S. D., Lim, M. P., Devi, L. A. (2012). Opioid receptor heteromers in analgesia. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 14, e9. doi: 10.1017/erm.2012.5

Décaillot, F. M., Rozenfeld, R., Gupta, A., Devi, L. A. (2008). Cell surface targeting of mu-delta opioid receptor heterodimers by RTP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 16045–16050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804106105

Darcq, E., Kieffer, B. L. (2018). Opioid receptors: drivers to addiction? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 499–514. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0028-x

Dart, R. C., Surratt, H. L., Cicero, T. J., Parrino, M. W., Severtson, S. G., Bucher-Bartelson, B., et al. (2015). Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. New Engl. J. Med. 372, 241–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143

Dourish, C. T., O'Neill, M. F., Coughlan, J., Kitchener, S. J., Hawley, D., Iversen, S. D. (1990). The selective CCK-B receptor antagonist L-365,260 enhances morphine analgesia and prevents morphine tolerance in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 176, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90129-T

Erbs, E., Faget, L., Scherrer, G., Matifas, A., Filliol, D., Vonesch, J. L., et al. (2015). A mu-delta opioid receptor brain atlas reveals neuronal co-occurrence in subcortical networks. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 677–702. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0717-9

Ferré, S., Casadó, V., Devi, L. A., Filizola, M., Jockers, R., Lohse, M. J., et al. (2014). G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 66, 413–434. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008052

Ferré, S. (2015). The GPCR heterotetramer: challenging classical pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36, 145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.01.002

George, S. R., Fan, T., Xie, Z., Tse, R., Tam, V., Varghese, G., et al. (2000). Oligomerization of mu- and delta-opioid receptors. Generation of novel functional properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26128–26135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000345200

Gomes, I., Gupta, A., Filipovska, J., Szeto, H. H., Pintar, J. E., Devi, L. A. (2004). A role for heterodimerization of mu and delta opiate receptors in enhancing morphine analgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 5135–5139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307601101

Gomes, I., Ijzerman, A. P., Ye, K., Maillet, E. L., Devi, L. A. (2011). G protein-coupled receptor heteromerization: a role in allosteric modulation of ligand binding. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 1044–1052. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.070847

Gomes, I., Fujita, W., Gupta, A., Saldanha, S. A., Negri, A., Pinello, C. E., et al. (2013). Identification of a μ-δ opioid receptor heteromer-biased agonist with antinociceptive activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 12072–12077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222044110

Gomes, I., Ayoub, M. A., Fujita, W., Jaeger, W. C., Pfleger, K. D., Devi, L. A. (2016). G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 56, 403–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135952

Guo, R., Chen, L. H., Xing, C., Liu, T. (2019). Pain regulation by gut microbiota: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Br. J. Anaesth. 123, 637–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.07.026

Gupta, A., Mulder, J., Gomes, I., Rozenfeld, R., Bushlin, I., Ong, E., et al. (2010). Increased abundance of opioid receptor heteromers after chronic morphine administration. Sci. Signaling 3, ra54. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000807

Hasbi, A., Nguyen, T., Fan, T., Cheng, R., Rashid, A., Alijaniaram, M., et al. (2007). Trafficking of preassembled opioid mu-delta heterooligomer-Gz signaling complexes to the plasma membrane: coregulation by agonists. Biochemistry 46, 12997–13009. doi: 10.1021/bi701436w

He, S. Q., Zhang, Z. N., Guan, J. S., Liu, H. R., Zhao, B., Wang, H. B., et al. (2011). Facilitation of μ-opioid receptor activity by preventing δ-opioid receptor-mediated codegradation. Neuron 69, 120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.001

Hutchinson, M. R., Shavit, Y., Grace, P. M., Rice, K. C., Maier, S. F., Watkins, L. R. (2011). Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. PharmacolRev 63, 772–810. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004135

Jordan, B. A., Devi, L. A. (1999). G-protein-coupled receptor heterodimerization modulates receptor function. Nature 399, 697–700. doi: 10.1038/21441

Kabli, N., Fan, T., O'Dowd, B. F., George, S. R., Kabli, N., Nguyen, T., et al. (2014). μ-δ opioid receptor heteromer-specific signaling in the striatum and hippocampus Antidepressant-like and anxiolytic-like effects following activation of the μ-δ opioid receptor heteromer in the nucleus accumbens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 450, 906–911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.099

Kamisaki, Y., Hamada, T., Maeda, K., Ishimura, M., Itoh, T. (1993). Presynaptic alpha 2 adrenoceptors inhibit glutamate release from rat spinal cord synaptosomes. J. Neurochem. 60, 522–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03180.x

Kibaly, C., Xu, C., Cahill, C. M., Evans, C. J., Law, P. Y. (2019). Non-nociceptive roles of opioids in the CNS: opioids' effects on neurogenesis, learning, memory and affect. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 5–18. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0092-2

Koshimizu, T. A., Honda, K., Nagaoka-Uozumi, S., Ichimura, A., Kimura, I., Nakaya, M., et al. (2018). Complex formation between the vasopressin 1b receptor, beta-arrestin-2, and the mu-opioid receptor underlies morphine tolerance. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 820–833. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0144-y

Liu, N. J., Chakrabarti, S., Schnell, S., Wessendorf, M., Gintzler, A. R. (2011). Spinal synthesis of estrogen and concomitant signaling by membrane estrogen receptors regulate spinal κ- and μ-opioid receptor heterodimerization and female-specific spinal morphine antinociception. J. Neurosci. : Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 31, 11836–11845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1901-11.2011

Liu, X. Y., Liu, Z. C., Sun, Y. G., Ross, M., Kim, S., Tsai, F. F., et al. (2011). Unidirectional Cross-Activation of GRPR by MOR1D Uncouples Itch and Analgesia Induced by Opioids. Cell 147, 447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.043

Li-Wei, C., Can, G., De-He, Z., Qiang, W., Xue-Jun, X., Jie, C., et al. (2002). Homodimerization of human mu-opioid receptor overexpressed in Sf9 insect cells. Protein Pept. Lett. 9, 145–152. doi: 10.2174/0929866023408850

Machelska, H., Celik, M. (2018). Advances in Achieving Opioid Analgesia Without Side Effects. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1388. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01388

Machelska, H., Celik, M. (2020). Opioid Receptors in Immune and Glial Cells-Implications for Pain Control. Front. Immunol. 11, 300. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00300

Manduca, A., Lassalle, O., Sepers, M., Campolongo, P., Cuomo, V., Marsicano, G., et al. (2016). Interacting Cannabinoid and Opioid Receptors in the Nucleus Accumbens Core Control Adolescent Social Play. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 211. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00211

Mao, J., Price, D. D., Mayer, D. J. (1995). Mechanisms of hyperalgesia and morphine tolerance: a current view of their possible interactions. Pain 62, 259–274. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00073-2

Metcalf, M. D., Yekkirala, A. S., Powers, M. D., Kitto, K. F., Fairbanks, C. A., Wilcox, G. L., et al. (2012). The δ opioid receptor agonist SNC80 selectively activates heteromeric μ-δ opioid receptors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 3, 505–509. doi: 10.1021/cn3000394

Milan-Lobo, L., Whistler, J. L. (2011). Heteromerization of the μ- and δ-opioid receptors produces ligand-biased antagonism and alters μ-receptor trafficking. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 337, 868–875. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179093

Moreno, E., Quiroz, C., Rea, W., Cai, N. S., Mallol, J., Cortés, A., et al. (2017). Functional μ-Opioid-Galanin Receptor Heteromers in the Ventral Tegmental Area. J. Neurosci. 37, 1176–1186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2442-16.2016

Olson, K. M., Keresztes, A., Tashiro, J. K., Daconta, L. V., Hruby, V. J., Streicher, J. M., et al. (2018). Synthesis and Evaluation of a Novel Bivalent Selective Antagonist for the Mu-Delta Opioid Receptor Heterodimer that Reduces Morphine Withdrawal in Mice Evidence and Function Relevance of Native DOR-MOR Heteromers Heteromers of μ-δ opioid receptors: new pharmacology and novel therapeutic possibilities. J. Med. Chem. 61, 6075–6086. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00403

Ong, E. W., Xue, L., Olmstead, M. C., Cahill, C. M. (2015). Prolonged morphine treatment alters δ opioid receptor post-internalization trafficking. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 615–629. doi: 10.1111/bph.12761

Pasternak, G. W., Pan, Y. X. (2013). Mu opioids and their receptors: evolution of a concept. Pharmacol. Rev. 65, 1257–1317. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138

Pu, S. F., Zhuang, H. X., Han, J. S. (1994). Cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) antagonizes morphine analgesia in nucleus accumbens of the rat via the CCK-B receptor. Brain Res. 657, 159–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90963-6

Raehal, K. M., Bohn, L. M. (2014). β-arrestins: regulatory role and therapeutic potential in opioid and cannabinoid receptor-mediated analgesia. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 219, 427–443. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41199-1_22

Rios, C., Gomes, I., Devi, L. A. (2006). mu opioid and CB1 cannabinoid receptor interactions: reciprocal inhibition of receptor signaling and neuritogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 148, 387–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706757

Rodríguez-Muñoz, M., Sánchez-Blázquez, P., Vicente-Sánchez, A., Berrocoso, E., Garzón, J. (2012). The mu-opioid receptor and the NMDA receptor associate in PAG neurons: implications in pain control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 338–349. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.155

Rodriguez, J. J., Mackie, K., Pickel, V. M. (2001). Ultrastructural localization of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in mu-opioid receptor patches of the rat Caudate putamen nucleus. J. Neurosci. 21, 823–833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00823.2001

Roeckel, L. A., Le Coz, G. M., Gaveriaux-Ruff, C., Simonin, F. (2016). Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Neuroscience 338, 160–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.029

Rozenfeld, R., Devi, L. A. (2007). Receptor heterodimerization leads to a switch in signaling: beta-arrestin2-mediated ERK activation by mu-delta opioid receptor heterodimers. FASEB J. 21, 2455–2465. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7793com

Salio, C., Fischer, J., Franzoni, M. F., Mackie, K., Kaneko, T., Conrath, M. (2001). CB1-cannabinoid and mu-opioid receptor co-localization on postsynaptic target in the rat dorsal horn. Neuroreport 12, 3689–3692. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00017

Scherer, P. C., Zaccor, N. W., Neumann, N. M., Vasavda, C., Barrow, R., Ewald, A. J., et al. (2017). TRPV1 is a physiological regulator of μ-opioid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 13561–13566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717005114

Scherrer, G., Imamachi, N., Cao, Y. Q., Contet, C., Mennicken, F., O'Donnell, D., et al. (2009). Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell 137, 1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019

Schuckit, M. A. (2016). Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders. New Engl. J. Med. 375, 357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1604339

Skolnick, P. (2018). The Opioid Epidemic: Crisis and Solutions. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 58, 143–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052534

Stein, C. (2016). Opioid Receptors. Annu. Rev. Med. 67, 433–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062613-093100

Stone, L. S., MacMillan, L. B., Kitto, K. F., Limbird, L. E., Wilcox, G. L. (1997). The alpha2a adrenergic receptor subtype mediates spinal analgesia evoked by alpha2 agonists and is necessary for spinal adrenergic-opioid synergy. J. Neurosci. 17, 7157–7165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07157.1997

Sun, G. C., Ho, W. Y., Chen, B. R., Cheng, P. W., Cheng, W. H., Hsu, M. C., et al. (2015). GPCR dimerization in brainstem nuclei contributes to the development of hypertension. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 2507–2518. doi: 10.1111/bph.13074

Suzuki, S., Chuang, L. F., Yau, P., Doi, R. H., Chuang, R. Y. (2002). Interactions of opioid and chemokine receptors: oligomerization of mu, kappa, and delta with CCR5 on immune cells. Exp. Cell Res. 280, 192–200. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5638

Sykes, K. T., White, S. R., Hurley, R. W., Mizoguchi, H., Tseng, L. F., Hammond, D. L. (2007). Mechanisms responsible for the enhanced antinociceptive effects of micro-opioid receptor agonists in the rostral ventromedial medulla of male rats with persistent inflammatory pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322, 813–821. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121954

Szabo, I., Chen, X. H., Xin, L., Adler, M. W., Howard, O. M., Oppenheim, J. J., et al. (2002). Heterologous desensitization of opioid receptors by chemokines inhibits chemotaxis and enhances the perception of pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 10276–10281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102327699

Tan, M., Walwyn, W. M., Evans, C. J., Xie, C. W. (2009). p38 MAPK and beta-arrestin 2 mediate functional interactions between endogenous micro-opioid and alpha2A-adrenergic receptors in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6270–6281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806742200

Tao, Y. M., Yu, C., Wang, W. S., Hou, Y. Y., Xu, X. J., Chi, Z. Q., et al. (2017). Heteromers of μ opioid and dopamine D(1) receptors modulate opioid-induced locomotor sensitization in a dopamine-independent manner. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 2842–2861. doi: 10.1111/bph.13908

Tiwari, V., He, S. Q., Huang, Q., Liang, L., Yang, F., Chen, Z., et al. (2020). Activation of µ-δ opioid receptor heteromers inhibits neuropathic pain behavior in rodents. Pain 161, 842–855. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001768

Ugur, M., Derouiche, L., Massotte, D. (2018). Heteromerization Modulates mu Opioid Receptor Functional Properties in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1240. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01240

Vilardaga, J. P., Nikolaev, V. O., Lorenz, K., Ferrandon, S., Zhuang, Z., Lohse, M. J. (2008). Conformational cross-talk between alpha2A-adrenergic and mu-opioid receptors controls cell signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 126–131. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.64

Volkow, N. D., McLellan, A. T. (2016). Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain–Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies. New Engl. J. Med. 374, 1253–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771

Walwyn, W., John, S., Maga, M., Evans, C. J., Hales, T. G. (2009). Delta receptors are required for full inhibitory coupling of mu-receptors to voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 134–143. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055913

Wang, H. B., Zhao, B., Zhong, Y. Q., Li, K. C., Li, Z. Y., Wang, Q., et al. (2010). Coexpression of delta- and mu-opioid receptors in nociceptive sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 13117–13122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008382107

Wang, D., Tawfik, V. L., Corder, G., Low, S. A., François, A., Basbaum, A. I., et al. (2018). Functional Divergence of Delta and Mu Opioid Receptor Organization in CNS Pain Circuits. Neuron 98, 90–108 e105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.002

Wang, D., Stoveken, H. M., Zucca, S., Dao, M., Orlandi, C., Song, C., et al. (2019). Genetic behavioral screen identifies an orphan anti-opioid system. Science 365, 1267–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2078

Williams, J. T., Ingram, S. L., Henderson, G., Chavkin, C., von Zastrow, M., Schulz, S., et al. (2013). Regulation of mu-opioid receptors: desensitization, phosphorylation, internalization, and tolerance. Pharmacol. Rev. 65, 223–254. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005942

Xie, W. Y., He, Y., Yang, Y. R., Li, Y. F., Kang, K., Xing, B. M., et al. (2009). Disruption of Cdk5-associated phosphorylation of residue threonine-161 of the delta-opioid receptor: impaired receptor function and attenuated morphine antinociceptive tolerance. J. Neurosci. 29, 3551–3564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0415-09.2009

Yang, Y., Li, Q., He, Q. H., Han, J. S., Su, L., Wan, Y. (2018). Heteromerization of μ-opioid receptor and cholecystokinin B receptor through the third transmembrane domain of the μ-opioid receptor contributes to the anti-opioid effects of cholecystokinin octapeptide. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–16. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0090-5

Yekkirala, A. S., Banks, M. L., Lunzer, M. M., Negus, S. S., Rice, K. C., Portoghese, P. S. (2012). Clinically employed opioid analgesics produce antinociception via μ-δ opioid receptor heteromers in Rhesus monkeys. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 3, 720–727. doi: 10.1021/cn300049m

Zhang, Z., Pan, Z. Z. (2010). Synaptic mechanism for functional synergism between delta- and mu-opioid receptors. J. Neurosci. 30, 4735–4745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5968-09.2010

Keywords: pain, opioid, opioid receptor, heterodimer, side effect

Citation: Zhang L, Zhang J-T, Hang L and Liu T (2020) Mu Opioid Receptor Heterodimers Emerge as Novel Therapeutic Targets: Recent Progress and Future Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 11:1078. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01078

Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 02 July 2020;

Published: 15 July 2020.

Edited by:

Giacinto Bagetta, University of Calabria, ItalyReviewed by:

Luigi Antonio Morrone, University of Calabria, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Zhang, Zhang, Hang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lihua Hang, empoYW5nbGlodWFAZm94bWFpbC5jb20=; Tong Liu, bGl1dG9uZzgwQHN1ZGEuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.