- 1Section of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

- 2Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

A high percentage of persons with Schizophrenia also uses Cannabis and this may potentially alter the therapeutic benefits of the antipsychotic medications prescribed. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of Cannabis usage on antipsychotic therapy of sleep disturbances in schizophrenia subjects. Male subjects, ≥18 years, admitted to the University Hospital of the West Indies psychiatric ward between October 2015 and October 2016, and diagnosed with schizophrenia were recruited for the study. Following written informed consent to the study, subjects were prescribed either risperidone monotherapy or haloperidol monotherapy orally for 14 days and classified as Cannabis users (CU) or non-users (non-CU), with presence/absence of Cannabis metabolite in urine samples. After 1 week of admission, subjects wore the Actiwatch-2 device, to record sleep data for 7 consecutive nights. Inferential statistical analysis involved non-parametric tests, expressed as median and inter-quartile ranges (IQR), with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Fifty subjects were assessed, with a median (IQR) age of 28 (14) years. Majority (30; 60%) were CU, displaying longer sleep latency (SL) than non-CU when receiving haloperidol; but equivalent SL when receiving risperidone. In comparison to non-CU, the CU also displayed longer time in bed, but shorter durations asleep, awoke more frequently during the nights and for longer durations, whether receiving haloperidol or risperidone. This resulted in lower sleep efficiency for the CU (<85%) compared to the non-CU (≥85%). Over the study period, sleep efficiency was significantly improved for non-CU receiving either risperidone (p = 0.032) or haloperidol (p = 0.010); but was only significantly improved with risperidone for the CU (p = 0.045). It is apparent that the presence of Cannabis may be impacting the therapeutic benefits of antipsychotic drugs on sleep. In schizophrenia subjects with concomitant Cannabis use, risperidone is more beneficial than haloperidol in improving sleep efficiency.

Introduction

The prognosis of schizophrenia is often worsened with Cannabis use (Foti et al., 2010; Manrique-Garcia et al., 2014), mainly through potentiation of the well-established dopamine dysregulations in schizophrenia (Bossong et al., 2009, 2015). High percentages of Cannabis users (CU) report that it promotes sleep (Cousens and DiMascio, 1973; Schofield et al., 2006; Schaub et al., 2008; Goonawardena et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2013); however, polysomnographic sleep assessment show relatively inconsistent sleep-promoting properties of Cannabis (Gates et al., 2014, 2016). Pharmacological intervention in schizophrenia requires long-term administration of antipsychotic drugs (Mercolini et al., 2007; Fumagalli et al., 2009; Uchida et al., 2011), which block the dopaminergic system. In early polysomnographic studies, typical antipsychotic drugs, such as haloperidol (Clarenbach et al., 1978; Taylor et al., 1991; Maixner et al., 1998; Dursun et al., 1999), demonstrate sleep-promoting effects and improve sleep maintenance/continuity, mainly through the reduction of sleep latency (SL) and frequency of awakening, prolongation of sleep time and an increase in sleep efficiency in healthy subjects and schizophrenia patients (Taylor et al., 1991; Benson, 2006; Cohrs, 2008; Anderson and Bradley, 2013). In contrast to typical antipsychotics, the atypical agents, including risperidone, have demonstrated greater improvement of sleep efficiency, due to the higher affinity for serotonin 5-HT2A/2C receptors, which are involved in controlling sleep quality (Dursun et al., 1999; Ichikawa et al., 2001; Miller, 2004; Cohrs, 2008; Anderson and Bradley, 2013). Furthermore, schizophrenia patients treated with risperidone display better sleep quantity, sleep quality, and general functioning compared to patients treated with typical antipsychotic drugs (Dursun et al., 1999; Yamashita et al., 2002; Giménez et al., 2007; Apiquian et al., 2008; Wichniak et al., 2011).

It is possible for Cannabis use to alter the clinical benefits of antipsychotic drugs (Thomas et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2016; Foglia et al., 2017); however, there is a paucity of information evaluating the impact of Cannabis use on the sleep outcomes of schizophrenic patients being treated with antipsychotics. Through actigraphy, this study examined the differences in sleep parameters in schizophrenia patients treated with risperidone vs. haloperidol and the impact of Cannabis use. Sleep quality can be estimated through sleep efficiency percentage, which incorporates the ratio of total sleep time and total time in bed; both of which can be altered by the SL, wake after sleep onset (WASO) duration and number of awakening (Shrivastava et al., 2014; Reed and Sacco, 2016; Sathyanarayana et al., 2016).

Methods and Subjects

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee. Males of at least 18 years of age were recruited from the University Hospital of the West Indies’ psychiatric ward between October 2015 and October 2016, if they met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) criteria for schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder or brief psychotic disorder, as assessed by trained psychiatrists managing each patient. Psychiatric assessments were conducted by three psychiatrists. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject’s relative/guardian on day 1. After consent, urine samples (5 mL) were collected in sterile containers and screened for the possible use of Cannabis, using the SD BIOLINE drug of abuse kit, based on the analysis for 11-nor-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-Carboxylic acid; the main metabolite of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, with a detection limit of 50 ng/mL. Subjects were classified as Cannabis users (CU) or non-users (non-CU), with a positive or negative kit result, respectively. Psychiatrists managing subjects were blinded from the Cannabis result.

Subjects were hospitalized for the 2-weeks study period, and recruited if administered either risperidone or haloperidol, orally at a dose prescribed by the assigned psychiatrists. Therapy could be flexibly adjusted within the therapeutic range as clinically warranted (risperidone, 6–8 mg/day; haloperidol, 10–20 mg/day). In addition, all enrolled subject received daily administrations of benztropine, 2 mg/day. Subjects were excluded from the study if they were receiving any other concomitant medications. Subjects who presented with diagnoses of other central nervous system disorders, mental retardation, somatic diseases, trauma or brain injury and primary sleep disorders were also excluded. Female subjects were excluded to control for the hormone-dependent confounding differences with Cannabis use (Craft et al., 2013; Castelli et al., 2014) and sleep disturbances (Sharkey et al., 2014). Demographic information collected from each subject’s docket included age, ethnicity, marital status, occupational status and educational level. History of psychosis (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or brief psychotic disorder) and previous substances abused (Cannabis, tobacco, alcohol, other), if any, were also recorded upon admission to the psychiatric ward.

After 7 days of antipsychotic therapy, only subjects remaining on monotherapy and confirmed by psychiatrist as displaying mild to moderate symptoms (scores < 53), using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) were then given the Actiwatch-2 device (Respironics, Inc., Murrysville, PA, United States) to wear on the non-dominant wrist. This device recorded sleep data in each subject for seven consecutive nights, 8 h each night, from 10:00 P.M. to 6:00 A.M. Computer scoring of actigraphy-recorded sleep parameters were performed using Respironics Actiware software, version 5.70.0. The software default setting of immobile minutes was used as the sleep interval detection algorithm. Immobility was determined if the activity counts (AC) was <4 in a 1 min epoch. The data were analyzed using medium wake thresholds (40 AC), with 10 min of immobility set for sleep onset and sleep end. Sleep parameters were calculated during the sleep/rest period (when AC was <40 AC threshold), which was set three different ways: (1) automatic scoring of major rest intervals by the software; (2) pre-determined bedtimes and wake-up times for each subject; (3) manual setting based on surrounding activity level. With the manual setting, the start and end of the sleep period were set close to the pre-determined times on the ward, providing that the AC were not >500 for 2 min, or >1,000 for 5 min, at the start. End of sleep was set when the AC increased to >0 for 5 min, without an epoch scored as sleep. A subject was likely scored as sleep when immobile for 3 h or more. While each of these parameters may have been manipulated by the user, sleep/wake analysis was performed automatically by the software. The scorer was blinded to Cannabis status when manually setting the rest intervals. Sleep parameters measured include SL, frequency of awakening, duration of WASO and total sleep time (TST).

Data and Statistical Analysis

Sleep efficiency percentage (SE%) is a good overall descriptor of a night’s sleep, as it reflects the percentage of time in bed actually spent sleeping (Shrivastava et al., 2014; Reed and Sacco, 2016; Sathyanarayana et al., 2016). SE% was calculated as the percentage of the ratio TST/Time spent in bed (TIB); with TIB calculated as the sum of SL, TST, and WASO. Additionally, sleep efficiency scores were classified as good-quality sleep (SE% ≥ 85%) or poor-quality sleep (SE% < 85%) (Reed and Sacco, 2016; Sathyanarayana et al., 2016). The power of the study was calculated using SE% for CU and non-users, prescribed either haloperidol or risperidone. The power for SE% was >80%, which was adequate. Daily drug dosages were converted to chlorpromazine equivalent (CPZE) doses (Danivas and Venkatasubramanian, 2013) to facilitate drug dosage comparisons.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v.20) for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), with the level of significance set at p < 0.05. Demographic data and continuous variables were evaluated using descriptive statistics and expressed as medians and IQR, frequencies (n) and percentages, as appropriate. Subjects were divided into four groups: CU vs. non-CU receiving haloperidol therapy and CU vs. non-CU receiving risperidone therapy. Inferential statistics involved use of Spearman Rho to determine correlations between Cannabis grouping and the actigraphy-measured sleep parameters, Kruskal-Wallis test for comparisons across all four groups, with post hoc analysis between groups using Bonferroni corrections, and Friedman test for the change in SE% over the seven nights.

Results

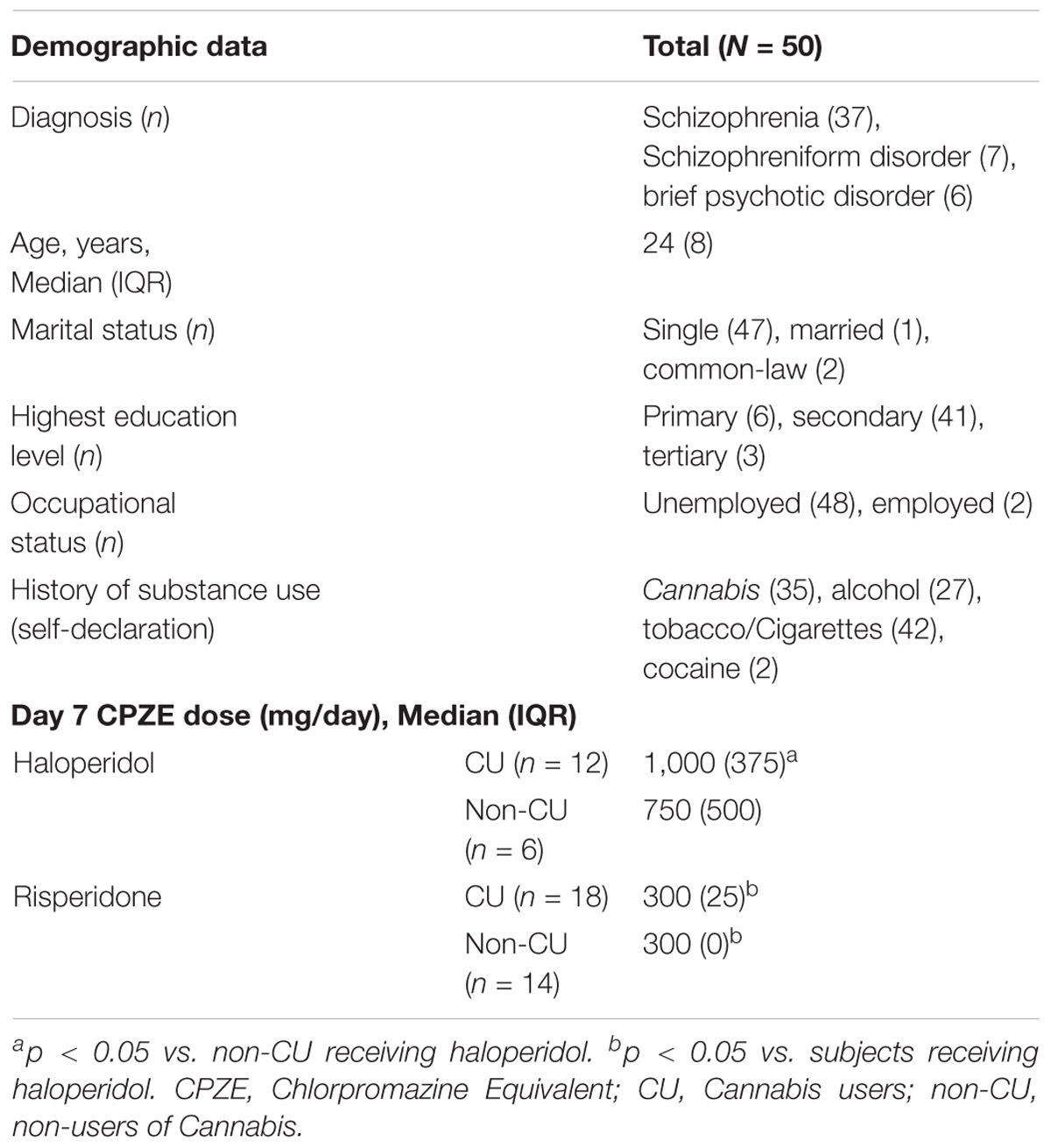

Table 1 gives demographic information of the 50 male subjects of Afro-Caribbean descent who completed the study. The sample population consisted of 30 subjects (60%) presenting with first-time psychotic episodes (acute psychosis/drug-naive). The remaining 20 subjects (40%) had undergone outpatient therapy or had previously been treated in an inpatient setting. Duration of illness was the only variable significantly different between the acute vs. relapse subjects [0 (2) vs. 11 (1); p = 0.024]. Based on self-declaration, initiation of Cannabis use was from a median (IQR) age of 14 (2) years. Majority of subjects (n = 30, 60%) used Cannabis within one week of admission to the psychiatric ward and were classified as CU, with urinalysis. Eighteen CU subjects received risperidone and 12 received haloperidol. The remaining 20 subjects were grouped as non-CU, with 14 receiving risperidone and 6 receiving haloperidol. CU subjects received significantly higher doses of haloperidol compared to non-CU subjects (p = 0.001) and CU subjects receiving risperidone (p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in dose between CU and non-CU receiving risperidone. By day seven of therapy, there was no significant difference in the BPRS score of schizophrenia symptoms between CU and non-CU receiving haloperidol [30 (6) vs. 28 (9); p = 0.335] or risperidone [30 (9) vs. 30 (10); p = 0.722].

According to the rank order by Cohen and Holliday (1996), Spearman Rho analysis showed that for subjects receiving haloperidol, Cannabis use was moderately correlated to SL (r = 0.432, p = 0.017), but showed low correlations with TST (r = −0.335, p = 0.020), WASO duration (r = 0.308, p = 0.031) and frequency of awakening (r = 0.300, p = 0.038). This trend was similar for subjects receiving risperidone, with moderate and negative correlation of Cannabis use to TST (r = −0.433, p = 0.017), moderate and positive correlation to WASO duration (r = 0.412, p = 0.024) and low and positive correlation to frequency of awakening (r = 0.381, p = 0.035); but no correlation with SL (r = 0.336, p = 0.064).

Sleep parameters for CU and non-CU, receiving either haloperidol or risperidone are presented in Figure 1. Analysis across the groups showed significant differences for SL (p = 0.048), TST (p = 0.038), frequency of awakening (p = 0.022) and WASO (p = 0.030). For the subjects receiving haloperidol, CU subjects displayed significantly longer SL than non-CU subjects [14 (15) vs. 4 (7) minutes; p = 0.009] and had significantly less TST [314 (115) vs. 487 (101) minutes; p = 0.015]. During sleep, CU subjects had more frequency of awakening [34 (27) vs. 23 (24); p = 0.004] and longer WASO durations [73 (94) vs. 37 (42) minutes; p = 0.020]. For subjects receiving risperidone, there was no difference in the SL between groups [8 (15) vs. 6 (8) minutes; p = 0.088], but CU subjects had significantly less TST [370 (100) vs. 500 (259) minutes; p = 0.035], more frequency of awakening [28 (28) vs. 22 (18); p = 0.017] and longer WASO durations [53 (75) vs. 34 (21) minutes; p = 0.005] than non-CU subjects.

FIGURE 1. Average Sleep for Seven Consecutive Nights of Actigraphy Recording for CU and Non-CU Receiving either Haloperidol or Risperidone. Box-plots represent median (thick, dark horizontal lines), IQR (boxes), minimum and maximum (whiskers) of each sleep parameter recorded using actigraphy. Circles represents outliers in sleep data. bSignificant differences between CU and non-CU groups. cSignificant difference between CU treatment groups. (A) TST was significantly less for CU than non-CU when receiving either haloperidol (p = 0.015) or risperidone (p = 0.035); there was significantly less TST between CU receiving haloperidol and CU receiving risperidone (p = 0.045). (B) SL was significantly longer for CU than non-CU when receiving haloperidol (p = 0.009), but not when receiving risperidone. (C) Frequency of awakening after sleep onset was significantly more for CU than non-CU when receiving either haloperidol (p = 0.017) or risperidone (p = 0.004). (D) WASO duration was significantly longer for CU than non-CU when receiving either haloperidol (p = 0.005) or risperidone (p = 0.020); there was significantly longer WASO between CU receiving haloperidol and CU receiving risperidone (p = 0.022). CU, Cannabis user; non-CU, non-user of Cannabis; SL, sleep latency; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake after sleep onset.

Sleep parameters were not significantly different between the antipsychotic groups for non-CU subjects. Comparisons between CU groups showed no difference in SL and frequency of awakening; however, CU subjects receiving risperidone had longer TST (p = 0.045) and shorter WASO duration (p = 0.022) than CU subjects receiving haloperidol.

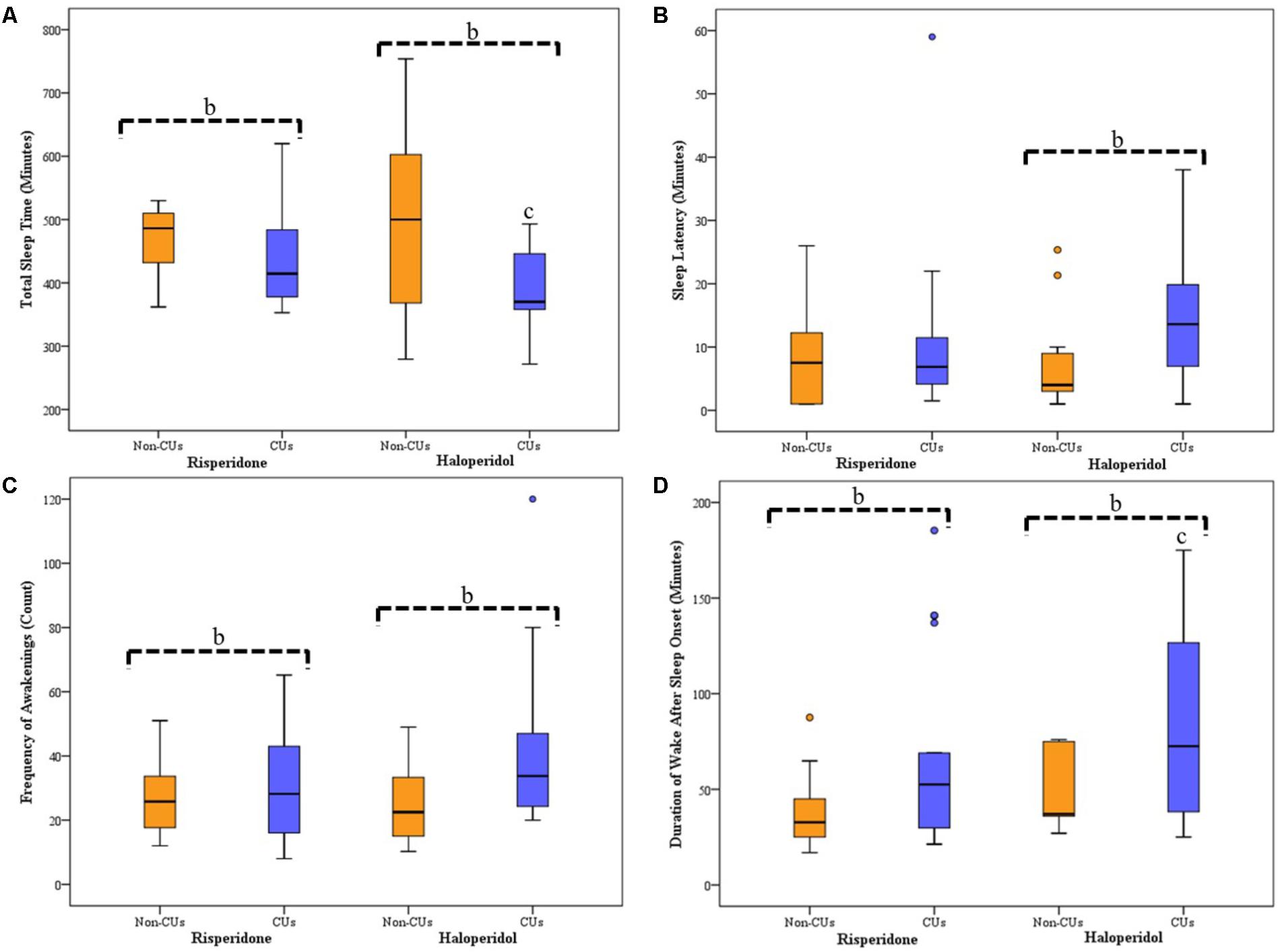

SE% for the seven consecutive nights of actigraphy recording for the CU and non-CU receiving either haloperidol or risperidone are presented in Figure 2. For non-CU subjects, sleep quality was consistently good (≥85%) over the seven nights and Friedman’s analysis showed significant improvements in SE% when receiving haloperidol (n = 6; χ2 = 16.82, p = 0.010, df = 6) or risperidone (n = 14; χ2 = 13.84, p = 0.032, df = 6). Good sleep quality and significant improvement in SE% was also recorded for CU subjects receiving risperidone (n = 18; χ2 = 12.90, p = 0.045, df = 6). Sleep quality was consistently poor for CU subjects receiving haloperidol and there was no improvement recorded over the 7 days (n = 12; χ2 = 2.78, p = 0.180, df = 6).

FIGURE 2. Increase in sleep efficiency percentage for seven consecutive nights for CU and non-CU receiving either haloperidol or risperidone. Each dot represents individual SE% for each subject and the thick horizontal lines indicate the median, on each assessment night. ∗Significant increase in SE% over 7 days of recording. (A) Significant increase in median SE% for non-CU receiving haloperidol (n = 6; χ2 = 16.822, p = 0.010, df = 6). (B) Significant increase in median SE% for non-CU receiving risperidone (n = 14; χ2 = 13.84, p = 0.032, df = 6). (C) No significant increase in median SE% for CU receiving haloperidol (n = 12; χ2 = 2.78, p = 0.180, df = 6). (D) Significant increase in median SE% for CU receiving risperidone (n = 18; χ2 = 12.90, p = 0.045, df = 6). Trend analyses were conducted using Friedman’s tests, with p < 0.05 representing significance. CU, Cannabis User; non-CU, non-user of Cannabis; SE%, Sleep Efficiency Percentage.

Discussions

Risperidone and haloperidol can improve sleep outcomes in schizophrenia patients (Taylor et al., 1991; Wetter et al., 1996; Maixner et al., 1998; Dursun et al., 1999; Haffmans et al., 2001, 2004; Yamashita et al., 2002; Miller, 2004; Monti and Monti, 2004). Similarly, in this study, both risperidone and haloperidol showed improvement in sleep outcomes over the 7 days among schizophrenic subjects not exposed to Cannabis. Contrastingly, subjects exposed to Cannabis use within 1 week of admission, displayed less total sleep time, with more frequent awakening and longer WASO duration, whether being treated with haloperidol or risperidone; thus, suggesting that the presence of Cannabis may be impacting the therapeutic benefits of both drugs on sleep. Converting the antipsychotic doses to CPZEs, our study found haloperidol therapy involved larger doses than risperidone therapy. For subjects exposed to Cannabis, the haloperidol dose requirements were much larger when compared with the dose given to non-users. This was not so for risperidone, as the dose was similar between non-users and subjects exposed to Cannabis.

Since last use of Cannabis by subjects in this study was more than 7 days before actigraphy measurements, the findings may be consistent with signs of Cannabis withdrawal on sleep (Bolla et al., 2008, 2010; Babson and Bonn-Miller, 2014; Gates et al., 2014, 2016; Babson et al., 2017). Sleep disturbance is a prominent Cannabis withdrawal symptom, usually noted after two nights (Bolla et al., 2008), and progresses over the first 2 weeks (Bolla et al., 2010) of abstinence. Budney et al. (2003) examined the impact of Cannabis withdrawal in 18 current users with 12 previous users of Cannabis as controls. Users abstained from smoking (confirmed through urine assay for Cannabis metabolites) and were assessed using Sleep Inventory questionnaires, administered by telephone daily for 50 days. The study reported sleep difficulty with Cannabis use, which peaked 2–6 days after abstinence and remained elevated over a course of 45 days.

Our findings are the first to use actigraphy readings to show that the benefits of haloperidol and risperidone can be significantly impacted by the use of Cannabis. Interestingly, risperidone therapy showed better sleep outcomes with recent use of Cannabis, as SL was equivalent to non-users. Also, CU awoke for longer durations after sleep onset and thus, slept less, with poor sleep quality when treated with haloperidol. Furthermore, only risperidone was successful at increasing the sleep efficiency among these subjects for the 7 days of observation.

Our findings among the subjects involved in this study may have significant implications, as they suggest risperidone may provide better clinical outcomes on sleep in schizophrenic patients who use Cannabis; more so in the Jamaican setting where Cannabis use among schizophrenic patients has been established to be high (Knight, 1976; Thomas et al., 2015). However, the positive confirmatory test for Cannabis is only able to detect acute Cannabis exposure; providing no measure of the history of Cannabis use, as documented by self-report of most subjects in this study. Subjects also provided self-report of using alcohol, tobacco and cocaine, which are possible confounders. Despite the presence of these substances and the time of admission not being assessed, the inpatient setting for the study period prevented access. Additionally, some of the subjects in this study previously received therapy with antipsychotics, which could also be a confounder. An antipsychotic-free control group would provide greater comparisons. However, in this setting, this would be unethical since all subjects were experiencing psychosis when admitted to the ward.

Conclusion

Cannabis use can attenuate the benefits of haloperidol and risperidone therapy on sleep in patients being treated for schizophrenia. The better sleep outcomes of risperidone support further examination of its possible superiority over haloperidol. However, the sample size was small, and a larger sample is recommended to confirm findings.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the University of the West Indies/University Hospital of the West Indies/Faculty of Medical Sciences Ethics committee guidelines for conducting research. The protocol was approved by the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee. Relatives/Guardians of all subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

The study was designed by MG-W, JM, and WA. P-GT-B reviewed the literature and wrote the protocol for the study. JM, CS, and WA aided in the recruitment of the study participants and performed the psychiatric assessments. Patient recruitment and assessments, sample preparations and assays and the data analyses were conducted by P-GT-B, who also made initial interpretations and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors further interpreted and discussed the findings and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer BC and handling Editor declared their shared affiliations.

References

Anderson, K. N., and Bradley, A. J. (2013). Sleep disturbance in mental health problems and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Sci. Sleep 5, 61–75. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S34842

Apiquian, R., Fresan, A., Munoz-Delgado, J., Kiang, M., Ulloa, R. E., and Kapur, S. (2008). Variations of rest-activity rhythm and sleep-wake in schizophrenic patients versus healthy subjects: an actigraphic comparative study. Biol. Rhythm Res. 39, 69–78. doi: 10.1080/09291010701318253

Babson, K. A., and Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2014). Sleep disturbances: implications for cannabis use, cannabis use cessation, and cannabis use treatment. Curr. Addict. Rep. 1, 109–114. doi: 10.1007/s40429-014-0016-9

Babson, K. A., Sottile, J., and Morabito, D. (2017). Cannabis, cannabinoids, and sleep: a review of the literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 4, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0775-9

Benson, K. L. (2006). Sleep in schizophrenia: impairments, correlates, and treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 29, 1033–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.08.002

Bolla, K. I., Lesage, S. R., Gamaldo, C. E., Neubauer, D. N., Funderburk, F. R., Cadet, J. L., et al. (2008). Sleep disturbance in heavy marijuana users. Sleep 31, 901–908. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.901

Bolla, K. I., Lesage, S. R., Gamaldo, C. E., Neubauer, D. N., Wang, N. Y., Funderburk, F. R., et al. (2010). Polysomnogram changes in marijuana users who report sleep disturbances during prior abstinence. Sleep Med. 11, 882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.013

Bossong, M. G., Mehta, M. A., van Berckel, B. N., Howes, O. D., Kahn, R. S., and Stokes, P. R. (2015). Further human evidence for striatal dopamine release induced by administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): selectivity to limbic striatum. Psychopharmacology 232, 2723–2729. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3915-0

Bossong, M. G., van Berckel, B. N., Boellaard, R., Zuurman, L., Schuit, R. C., Windhorst, A. D., et al. (2009). Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol induces dopamine release in the human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 759–766. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.138

Budney, A. J., Moore, B. A., Vandrey, R. G., and Hughes, J. R. (2003). The time course and significance of cannabis withdrawal. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 112, 393–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.393

Castelli, M. P., Fadda, P., Casu, A., Spano, M. S., Casti, A., Fratta, W., et al. (2014). Male and female rats differ in brain cannabinoid CB1 receptor density and function and in behavioural traits predisposing to drug addiction: effect of ovarian hormones. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 2100–2113. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319999043

Clarenbach, P., Prunkl, R., Riegler, M., and Cramer, H. (1978). Effects of haloperidol on afternoon sleep and on the secretion of growth hormone in man. Neuroscience 3, 345–348. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90083-0

Cohen, L., and Holliday, M. (1996). Practical Statistics for Students. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd., 83. doi: 10.4135/9781849209571

Cohrs, S. (2008). Sleep disturbances in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 22, 939–962. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822110-00004

Cousens, K., and DiMascio, A. (1973). (−) Δ9-THC as an hypnotic. Psychopharmacology 33, 355–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00437513

Craft, R. M., Marusich, J. A., and Wiley, J. L. (2013). Sex differences in cannabinoid pharmacology: a reflection of differences in the endocannabinoid system? Life Sci. 92, 476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.06.009

Danivas, V., and Venkatasubramanian, G. (2013). Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: comparing apples and oranges! Indian J. Psychiatry 55:207. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111475

Dursun, S. M., Patel, J. K., Burke, J. G., and Reveley, M. A. (1999). Effects of typical antipsychotic drugs and risperidone on the quality of sleep in patients with schizophrenia: a pilot study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 24, 333–337.

Foglia, E., Schoeler, T., Klamerus, E., Morgan, K., and Bhattacharyya, S. (2017). Cannabis use and adherence to antipsychotic medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000046

Foti, D. J., Kotov, R., Guey, L. T., and Bromet, E. J. (2010). Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalization. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 987–993. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09020189

Fumagalli, F., Frasca, A., Racagni, G., and Riva, M. A. (2009). Cognitive effects of second-generation antipsychotics. CNS Drugs 23, 603–614. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923070-00005

Gates, P. J., Albertella, L., and Copeland, J. (2014). The effects of cannabinoid administration on sleep: a systematic review of human studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 18, 477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.02.005

Gates, P. J., Albertella, L., and Copeland, J. (2016). Cannabis withdrawal and sleep: a systematic review of human studies. Subst. Abuse 37, 255–269. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1023484

Giménez, S., Clos, S., Romero, S., Grasa, E., Morte, A., and Barbanoj, M. J. (2007). Effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on sleep after a single oral morning dose in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 190, 507–516. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0633-7

Goonawardena, A. V., Plano, A., Robinson, L., Platt, B., Hampson, R. E., and Riedel, G. (2012). A pilot study into the effects of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55, 212-2 or the antagonist/inverse agonist AM251 on sleep in rats. Sleep Disord. 2011:178469. doi: 10.1155/2011/178469

Haffmans, P. M. J., Oolders, H. J., Hoencamp, E., and Schreiner, A. (2004). Sleep quality in schizophrenia and the effects of atypical antipsychotic medication. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 16, 281–289. doi: 10.1111/j.0924-2708.2004.00103.x

Haffmans, P. M. J., Oolders, J. M., Hoencamp, E., and Arends, J. B. A. M. (2001). The effect of risperidone versus haloperidol on sleep patterns of schizophrenic patients: results of a double-blind, randomised pilot trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11:S260. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(01)80310-2

Ichikawa, J., Ishii, H., Bonaccorso, S., Fowler, W. L., O’laughlin, I. A., and Meltzer, H. Y. (2001). 5-HT2A and D2 receptor blockade increases cortical DA release via 5-HT1A receptor activation: a possible mechanism of atypical antipsychotic-induced cortical dopamine release. J. Neurochem. 76, 1521–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00154.x

Knight, F. (1976). Role of cannabis in psychiatric disturbance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 282, 64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb49886.x

Maixner, S., Tandon, R., Eiser, A., Taylor, S., DeQuardo, J. R., and Shipley, J. (1998). Effects of antipsychotic treatment on polysomnographic measures in schizophrenia: a replication and extension. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 1600–1602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1600

Manrique-Garcia, E., Zammit, S., Dalman, C., Hemmingsson, T., Andreasson, S., and Allebeck, P. (2014). Prognosis of schizophrenia in persons with and without a history of cannabis use. Psychol. Med. 44, 2513–2521. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000191

Mercolini, L., Grillo, M., Bartoletti, C., Boncompagni, G., and Raggi, M. A. (2007). Simultaneous analysis of classical neuroleptics, atypical antipsychotics and their metabolites in human plasma. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 388, 235–243. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1195-1

Miller, D. D. (2004). Atypical antipsychotics: sleep, sedation, and efficacy. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 6, 3–7.

Monti, J. M., and Monti, D. (2004). Sleep in schizophrenia patients and the effects of antipsychotic drugs. Sleep Med. Rev. 8, 133–148. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(02)00158-2

Patel, R., Wilson, R., Jackson, R., Ball, M., Shetty, H., Broadbent, M., et al. (2016). Association of cannabis use with hospital admission and antipsychotic treatment failure in first episode psychosis: an observational study. BMJ Open 6:e009888. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009888

Reed, D. L., and Sacco, W. P. (2016). Measuring sleep efficiency: what should the denominator be? J. Clin. Sleep Med. 12, 263–266. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5498

Sathyanarayana, A., Joty, S., Fernandez-Luque, L., Ofli, F., Srivastava, J., Elmagarmid, A., et al. (2016). Sleep quality prediction from wearable data using deep learning. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 4:e125. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6562

Schaub, M., Fanghaenel, K., and Stohler, R. (2008). Reasons for cannabis use: patients with schizophrenia versus matched healthy controls. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 42, 1060–1065. doi: 10.1080/00048670802512016

Schofield, D., Tennant, C., Nash, L., Degenhardt, L., Cornish, A., Hobbs, C., et al. (2006). Reasons for cannabis use in psychosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 40, 570–574. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01840.x

Sharkey, K. M., Crawford, S. L., Kim, S., and Joffe, H. (2014). Objective sleep interruption and reproductive hormone dynamics in the menstrual cycle. Sleep Med. 15, 688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.02.003

Shrivastava, D., Jung, S., Saadat, M., Sirohi, R., and Crewson, K. (2014). How to interpret the results of a sleep study. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 4:24983. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v4.24983

Taylor, S. F., Tandon, R., Shipley, J. E., and Eiser, A. S. (1991). Effect of neuroleptic treatment on polysomnographic measures in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 30, 904–912. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90004-6

Thomas, P., Gossell-Williams, M., Sewell, C. A., Abel, W. D., McGrowder, D., and Martin, J. (2015). The impact of cannabis use on the dosage of antipsychotic drugs for patients admitted on the psychiatric ward at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Med. J. 1, 22–26. doi: 10.7727/wimjopen.2014.259

Uchida, H., Suzuki, T., Takeuchi, H., Arenovich, T., and Mamo, D. C. (2011). Low dose vs standard dose of antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 788–799. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp149

Walsh, Z., Callaway, R., Belle-Isle, L., Capler, R., Kay, R., Lucas, P., et al. (2013). Cannabis for therapeutic purposes: patient characteristics, access, and reasons for use. Int. J. Drug Policy 24, 511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.010

Wetter, T. C., Lauer, C. J., Gillich, G., and Pollmächer, T. (1996). The electroencephalographic sleep pattern in schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine or classical antipsychotic drugs. J. Psychiatr. Res. 30, 411–419. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(96)00022-2

Wichniak, A., Skowerska, A., Chojnacka-Wójtowicz, J., Tafliński, T., Wierzbicka, A., Jernajczyk, W., et al. (2011). Actigraphic monitoring of activity and rest in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine or risperidone. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45, 1381–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.05.009

Keywords: Cannabis, risperidone, haloperidol, schizophrenia, actigraphy, sleep

Citation: Thomas-Brown P-GL, Martin JS, Sewell CA, Abel WD and Gossell-Williams MD (2018) Risperidone Provides Better Improvement of Sleep Disturbances Than Haloperidol Therapy in Schizophrenia Patients With Cannabis-Positive Urinalysis. Front. Pharmacol. 9:769. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00769

Received: 21 February 2018; Accepted: 25 June 2018;

Published: 18 July 2018.

Edited by:

Mirko Manchia, Università degli Studi di Cagliari, ItalyReviewed by:

Luc Ver Donck, Janssen Research and Development, BelgiumBernardo Carpiniello, Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Italy

Stefano Comai, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Italy

Copyright © 2018 Thomas-Brown, Martin, Sewell, Abel and Gossell-Williams. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peta-Gaye L. Thomas-Brown, cGV0YWdheWUudGhvbWFzMDJAbXltb25hLnV3aS5lZHU=; dGhvbWFzcGV0YWdheWVAeWFob28uY29t

Peta-Gaye L. Thomas-Brown

Peta-Gaye L. Thomas-Brown Jacqueline S. Martin2

Jacqueline S. Martin2