- Phaneros, São Paulo, Brazil

Mental disorders are rising while development of novel psychiatric medications is declining. This stall in innovation has also been linked with intense debates on the current diagnostics and explanations for mental disorders, together constituting a paradigmatic crisis. A radical innovation is psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP): professionally supervised use of ketamine, MDMA, psilocybin, LSD and ibogaine as part of elaborated psychotherapy programs. Clinical results so far have shown safety and efficacy, even for “treatment resistant” conditions, and thus deserve increasing attention from medical, psychological and psychiatric professionals. But more than novel treatments, the PAP model also has important consequences for the diagnostics and explanation axis of the psychiatric crisis, challenging the discrete nosological entities and advancing novel explanations for mental disorders and their treatment, in a model considerate of social and cultural factors, including adversities, trauma, and the therapeutic potential of some non-ordinary states of consciousness.

The Current Psychiatric Crisis

Mental disorders increasingly contribute to the global burden of disease, with huge socio-economic costs (Catalá-López et al., 2013; Whiteford et al., 2013). However, research and development in psychopharmacology—psychiatry's primary mode of intervention—came to a halt in 2010 (Miller, 2010; Hyman, 2013). Approval of new molecular entities for psychiatric conditions by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fell from 13 in 1996 to one in 2016, with 49 approved between 1996 and 2006 and 22 from 2007 to 20161 In pharmacology conferences in the period, just about 5% of presentations were dedicated to human studies involving drugs with novel mechanisms of action (van Gerven and Cohen, 2011). These occurrences are part of a complex picture clearly dissected as a triple crisis in psychiatry: of therapeutics, diagnostics and explanation (Rose, 2016).

Problems surrounding psychiatric diagnosis also surfaced in 2010, when the UK Medical Research Council published a strategy for mental health and wellbeing (Sahakian et al., 2010) and the US National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) launched its Research Domain Criterion (RDoC). It proposed five domains based on specific neural systems that can be impaired in mental illness, a radical departure from the hundreds of discrete conceptual disorders of the much older Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (Casey et al., 2013; Insel, 2014; Kraemer, 2015). Thus, the RDoC advanced a multidimensional approach to diagnosing mental disorders in a continuous spectra (Adam, 2013). At around the same time, a network psychopathology perspective was conceptualized and empirically assessed with statistical models for psychometrics based on thousands of patient reports' and hundreds of symptoms (Fried et al., 2017).

The treatment and diagnostic axes of the crisis are connected by the explanatory domain: despite huge investment in neuroscience as the ultimate source for understanding mental illness, both classification and diagnosis (Stephan et al., 2016a) as well as knowledge about pathogenesis and etiology still faces many challenges (Stephan et al., 2016b). The explanatory debate about mental disorders is summarized by the contrasting declarations that “mental disorders are brain disorders” (Deacon, 2013; Insel and Cuthbert, 2015) or that psychiatry runs the risk of “losing the psyche” (Parnas, 2014).

Clinical Developments With Psychedelics

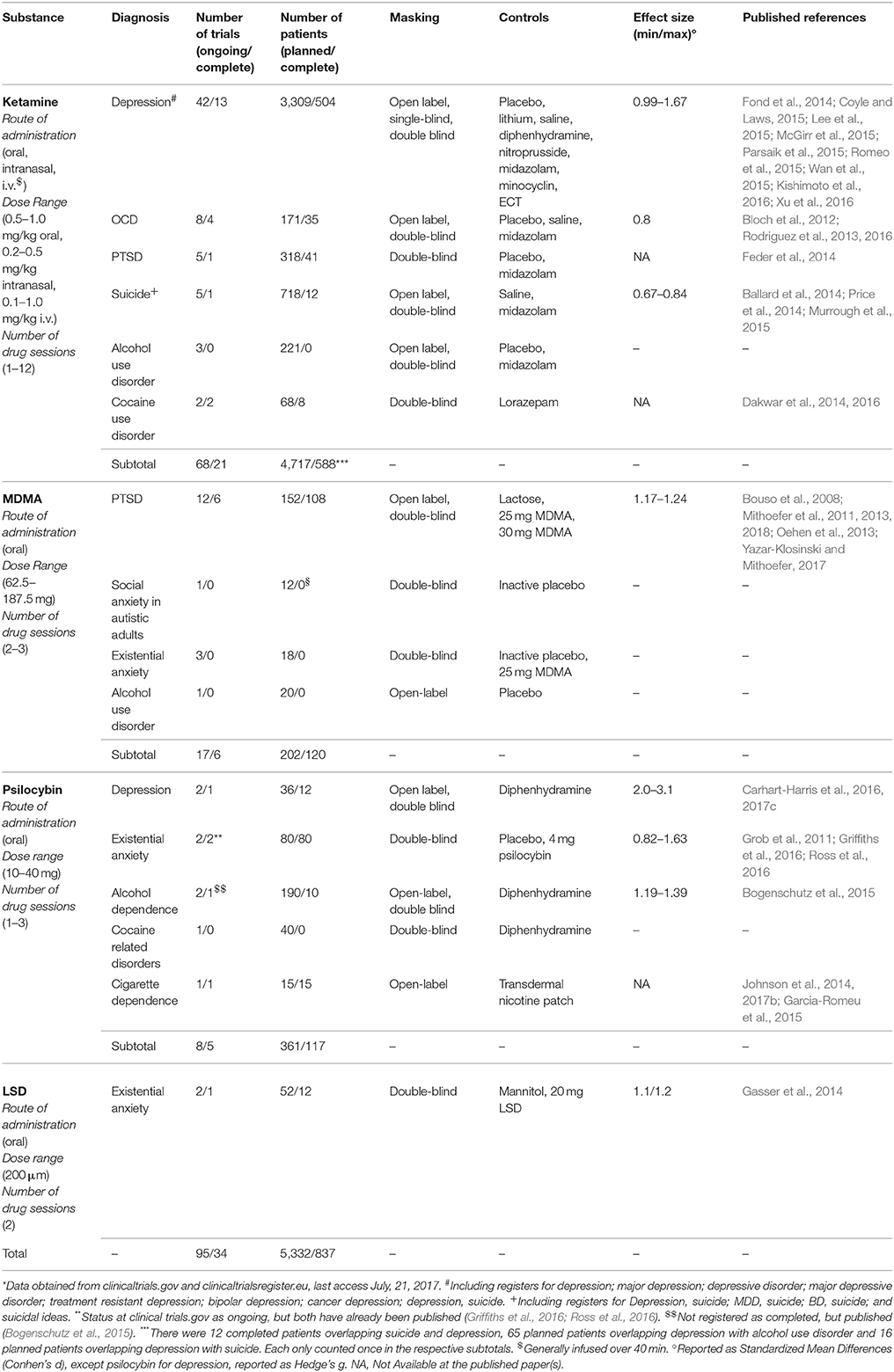

Synthetic substances like Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), 3,4-MethylenodioxyMetamphetamine (MDMA), 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-(methylamino) cyclohexanone (ketamine) and naturally occurring alkaloids including 4-phosphoriloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (psilocybin, present in hundreds of Psilocybe mushroom species) and 12-Methoxyibogamine (ibogaine, from Tabernanthe iboga) have been used in a series of studies (Passie et al., 2008; Brown, 2013; Tylš et al., 2014; Mithoefer et al., 2016; Nichols, 2016; for reviews see Winkelman, 2014; Dos Santos et al., 2016; Johnson and Griffiths, 2017; Nichols et al., 2017) as well as Phase 2 clinical trials (Table 1). These substances are orally active but have different mechanisms of action. LSD and psilocybin effects' critically depend on 5-HT2A agonism, MDMA inhibits monoamine transporters, especially for serotonin, while ketamine is an NMDA antagonist and ibogaine non-specifically binds to many receptors.

The most studied is ketamine, which in higher doses is an anesthetic in use for decades. In lower dosages it temporarily modify consciousness including changes in mood and cognition (Mion, 2017). It is the experimental intervention in almost 70 Phase 2 trials for psychiatric disorders and two Phase 3 trials for depression. Protocols involve single or repeated administrations in different doses, routes of delivery and research designs. Most are for depressive disorders, but is also studied for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), suicide, alcohol, and cocaine use disorders (Table 1). Nine meta-analysis from depression trials (Fond et al., 2014; Coyle and Laws, 2015; Lee et al., 2015; McGirr et al., 2015; Parsaik et al., 2015; Romeo et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2015; Kishimoto et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016) shows low frequency of serious adverse events in the short term (but see Short et al., 2017 for long-term reporting bias), with short-term positive outcomes for a significant proportion of patients.

MDMA is investigated in 17 Phase 2 trials (Table 1) and was designated a breakthrough therapy for PTSD by the FDA, a status that can expedite approval (Kupferschmidt, 2017). Also studied for social anxiety in autistic adults, existential anxiety and alcohol use disorder (Table 1), MDMA is commonly confused with the street drug “ecstasy” (also known as “molly”). However, these illegal products frequently do not contain MDMA, only adulterants (Vogels et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2011; Togni et al., 2015; Saleemi et al., 2017; Vrolijk et al., 2017). This loose terminology creates unfortunate confusion about MDMA's safety (Amoroso, 2016). In research with healthy volunteers, occurrences of hypertension, tachycardia and hyperthermia are below 1/3 of cases, not leading to serious adverse events (Vizeli and Liechti, 2017). In clinical populations, serious adverse events were very rare, with only one brief and self-limiting case of increased ventricular extrasystoles in more than 1,260 sessions (MAPS, 2017). Therapeutic results obtained with severe, treatment-resistant PTSD patients in Phase 2 studies were considered “spectacular” (Frood, 2012), with approximately 70% or more of participants no longer qualifying for the diagnosis after 12 months, while the remainder third had less intense symptoms. Furthermore, the improvements lasted up to 4 years, mostly without additional treatments and without inducing drug abuse or dependence (Mithoefer et al., 2013; Yazar-Klosinski and Mithoefer, 2017). An independent preliminary meta-analysis found MDMA-assisted psychotherapy was superior to prolonged exposure when evaluated by clinician-observed outcomes, by patient self-report outcomes and also by drop-outs (Amoroso and Workman, 2016).

Psilocybin is the third most studied psychedelic substance for clinical applications. It has a very high safety ratio (Gable, 2004; Tylš et al., 2014) and very low risk profile even in unsupervised settings (Nutt et al., 2010; van Amsterdam et al., 2011;)2 It's orally administered in eight trials for major depression, cigarettes, alcohol, and cocaine use disorders and existential anxiety in life-threatening diseases, mostly cancer. Despite moderately increasing blood pressure (Griffiths et al., 2011) and inducing transient headaches (Johnson et al., 2012), it has been safely administered to more than a 100 volunteers in neuroscientific research (Studerus et al., 2011) and another 100 in clinical studies with notable results (Table 1).

LSD, the most potent psychedelic currently administered in clinical trials, has very slow dissociation kinetics at the human 5-HT2A receptor and thus long lasting effects (Wacker et al., 2017). It has a very high safety ratio (Gable, 2004; Passie et al., 2008) and is not associated with major health impairments after unsupervised use (Krebs and Johansen, 2013; Hendricks et al., 2014, 2015; Johansen and Krebs, 2015). It is the active substance in just two recent Phase 2 trials for existential anxiety in the terminally ill (Table 1). This paucity is perhaps due to stigma surrounding large-scale recreational use since the 1960's, with considerable political implications (Dyck, 2005; Nutt et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2014). However, before political turmoil, more than a 1,000 studies including 40,000 patients were done (Grinspoon, 1981), mostly showing positive potentials (Abraham et al., 1996). LSD was thus the prototypical substance in the development of radically new forms of psychotherapy, including psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Pahnke et al., 1970; Grof, 1971, 2008) and another approach based on repeated low doses (10 to 50 μg) to potentiate psychoanalysis, known as psycholytic psychoherapy (Majić et al., 2015). Despite the paucity of recent trials, a recent meta-analysis with rigorous research from 60 years ago confirmed LSD also has important potential for alcohol use disorders (Krebs and Johansen, 2012).

Finally, ibogaine is the less advanced psychedelic in the development pipeline, with no interventional clinical trials executed or registered since the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) cancelled efforts to develop this compound to treat opioid addiction in the 1990's (Alper, 2001). And indeed there are important safety concerns, given ibogaine can prolong QT interval (Koenig and Hilber, 2015), potentially evolving to fatal cardiac arrhythmias (Koenig et al., 2014). This critically differentiates ibogaine's safety profile from other psychedelics. However, given the seriousness of drug addiction and the difficulty to treat these patients, observational and retrospective studies for opioid (Brown and Alper, 2017; Noller et al., 2017) and psychostimulant addiction (Schenberg et al., 2014, 2016, 2017) reporting considerable success suggests Phase 2 trials focusing on cardiac safety should be performed. Given ibogaine is unscheduled in many countries and currently used as an alternative treatment with an unfortunate series of fatalities (Alper et al., 2012), financial support is needed.

Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy (PAP)

Safeguarded important differences regarding safety and mechanisms of action, the grouping of these substances in a prototypical PAP model has important practical and theoretical implications. The main feature is the therapeutic use of a potent psychoactive substance (currently most are scheduled compounds) in very few sessions. These are generally accompanied by drug-free sessions before and/or after drug sessions, usually called preparatory and integrative psychotherapy, respectively. With ketamine positive results were obtained with one to 12 administrations, with MDMA just three and with psilocybin and LSD only two, while ibogaine may be effective after a single administration. During drug effects, patients are continuously monitored and supported by trained mental health professionals following available guidelines (Johnson et al., 2008)3. Generally patients listen to instrumental evocative music (Pahnke et al., 1970; Bonny and Pahnke, 1972; Kaelen et al., 2015; Barrett et al., 2017; Richards, 2017) and are encouraged to stay introspective (with eyeshades) and open to feelings, attentive to thoughts and memories, being free to engage in psychotherapy at any time (Grof, 2008). Frequency and type of psychotherapeutic interventions varied from a minimum in ketamine studies, sometimes including only music during drug effects, to a more intensive protocol with MDMA including 12 non-drug sessions, which follow a detailed manual based on non-directive transpersonal psychology3 (recently, MDMA has also been tested with cognitive behavioral conjoint therapy). Between these two ends of the spectrum are psilocybin, LSD and ibogaine studies, which used a variety of interventions. Psilocybin studies used psychological support comprised of non-directive preparation, support and integration in few non-drug sessions. LSD included three post-drug integrative sessions. Ibogaine, used in different clinics for drug dependence, included a series of more or less standardized psychotherapies for addiction, pre- and post-drug, like 12-steps, individual and group counseling, among others. Increasing focus on types and frequency of psychotherapeutic interventions can arguably help improve outcomes, as exemplified by older ketamine studies with existentially oriented psychotherapy for drug addiction (e.g., Krupitsky and Grinenko, 1997; Krupitsky et al., 2007) and as recently tested with cognitive behavioral therapy for relapse prevention after ketamine for depression (Wilkinson et al., 2017). As results from most trials reliably show, PAP can be more effective and faster than current treatments, even for patients considered “treatment resistant.” And these outcomes were not only statistically significant but had large effect sizes, which is encouraging for Phase 3 trials.

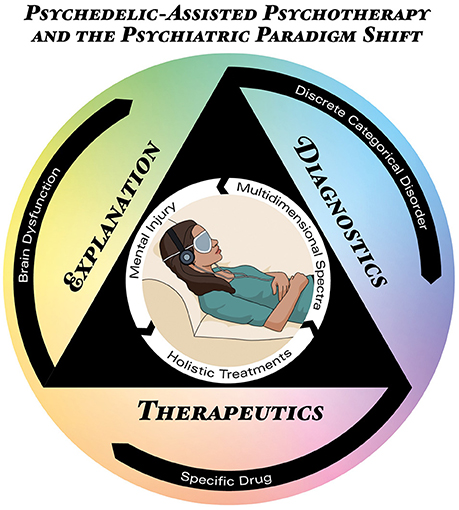

Beyond potential novel treatments, PAP has important practical and theoretical consequences for the three axes of the crisis. The combination of psychotherapy with psychedelics can be conceptualized as the induction of an experience with positive long-term mental health consequences, rather than daily neurochemical corrections in brain dysfunctions (Figure 1). Thus, a comprehensive understanding of PAP suggests a conceptual expansion of “drug efficacy” to “experience efficacy4” Instead of conceiving the drug as correcting functional imbalances in the brain through a specific receptor, PAP is a treatment modality in which specific pharmacological actions temporally induce modifications in brain functioning and conscious experience. When appropriately mediated, these can be deeply meaningful experiences that elicit the emotional, cognitive and behavioral changes reported. Attempts to develop ketamine and ibogaine analogs devoid of the subjective “psychedelic” effects, e.g., lanicemine and 18-MC, will further illuminate this question. However, available therapeutic results for depression with ketamine analogs with less dissociative effects were only modest (Iadarola et al., 2015), while ketamine administration without preparatory psychotherapy and music support recently resulted in an interrupted trial (Gálvez et al., 2018). Furthermore, positive correlations between subjective features like ketamine's dissociative effects (Luckenbaugh et al., 2014) or psilocybin peak-experience with positive treatment outcomes in depression (Roseman et al., 2018) corroborates the notion that the meanings of the psychedelic experience plays an important role in therapeutic outcomes (Grof, 2008; Hartogsohn, 2018). It is thus very hard to strictly reduce PAP to neuropharmacology. In this sense, PAP can benefit from potentially rich interactions with other fields like psychodynamic psychotherapy (Plakun, 2006, 2012). Furthermore, PAP can help solve many pressing safety concerns in current psychopharmacological treatments by bridging a current gap in knowledge between research and clinical practice. This gap is created because psychiatric clinical trials rarely last longer than 6 months (Downing et al., 2014), while the products approved based on these trials are later prescribed for chronic daily use for years, sometimes decades. Many current adverse consequences from the use of psychiatric prescription medications arise from this gap, including decreasing drug adherence over time (Chapman and Horne, 2013; Medic et al., 2013), toxicity from increasing polypharmacy (Mojtabai and Olfson, 2010; Kukreja et al., 2013), addiction to prescribed medications causing severe withdrawal symptoms (Wright et al., 2014; McHugh et al., 2015; Novak et al., 2016), and a plethora of side effects arising after prolonged daily drug use, e.g., weight changes, stomach pains, constipation, mood swings, confusion, abnormal thoughts, delusions, memory loss, restlessness, akathisia, tardive dyskinesia, sexual dysfunction, anxiety, dizziness, sleep problems, and even suicidal ideas5 By administering medications only under supervision, PAP can reduce or even eliminate drug adherence problems and polypharmacy. By administering psychoactive drugs just a few times, PAP can prevent addiction and the development of side effects after chronic use of medications. And by exclusively licensing psychedelics for especially licensed therapists and physicians, rather than prescription and dispensation to patients, PAP can reduce risks of diversion and abuse. Considered together, these PAP features can arguably help reduce psychiatry's alarmingly high-rate of post-market safety events, reported at more than 60% after 10 years (Downing et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy (PAP) mapped onto the triple-axis psychiatric crisis. The icon in the center represents the PAP model, located inside the triangle projecting the three axes of the current psychiatric crisis: therapeutics (bottom), diagnosis (right), and explanation (left). The outermost black circle represents the main conceptual formulation for each axis in current psychiatric theory, i.e., brain dysfunctions diagnosed as discrete categorical disorders treated with specific drugs. The innermost white circle represents the concepts supported by PAP: mental injuries diagnosed as a multidimensional spectra treated holistically.

Besides critical consequences for the therapeutic axis, PAP is also relevant for diagnostic concerns. The fact that ketamine and psilocybin, substances with radically different pharmacological mechanisms of action, can induce positive outcomes in a single disorder, like depression; or that a single substance like psilocybin can be used to treat different disorders, like depression or drug dependence, challenges nosologies which discriminate disorders in mutually-exclusive categories. Thus, PAP supports a multidimensional spectra (Figure 1). However, proposals such as the RDoC were criticized by its biomedical reductionism (Frances, 2014a; Parnas, 2014; Wakefield, 2014), while psychedelic research recognize the concept of set and setting (Eisner, 1997; Hartogsohn, 2016) as crucial for the results obtained with these treatments. Set includes circumstances and factors other than drug and pharmacological targets, including people's beliefs, attitudes, preferences, choices and motivations. Setting refers to environment, context, therapists, supporting team etc. Thus, PAP supports other conceptually richer diagnostic approaches considerate of biopsychosocial factors (Frances, 2014b; Lefèvre et al., 2014; Borsboom, 2017; Johnstone, 2017).

This does not imply that neuroscience is not fundamental to understanding PAP and its consequences for psychiatric research and development. On the contrary. Current limitations of neuroimaging in psychiatry include long-term confounders like smoking, weight and metabolic variations (Linden, 2012; Weinberger and Radulescu, 2016), and low prognostic accuracy and predictive validity (Linden, 2012; Berkman and Falk, 2013; Weinberger and Radulescu, 2016). By developing faster treatments and bridging the gap between research and clinical practice, PAP can allow the use of within-subject designs in shorter time spans (e.g., Carhart-Harris et al., 2017b), reducing the impact of confounders and improving reliability of neuroimaging data. Thus, confidence in translating results from acute psychedelic neuroimaging (Vollenweider and Kometer, 2010; Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2013; Carhart-Harris et al., 2014a,b, 2017b; Tagliazucchi et al., 2014; Kraehenmann et al., 2015; Scheidegger et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2017; Schartner et al., 2017) to clinical applications which will more closely resemble research designs is increased.

Finally, detailed study of the subjective aspects of PAP has enormous consequences for the explanatory axis. Recent qualitative and phenomenological research shows that psychedelic experiences involve meaningful autobiographical and social psychological concerns (Grof, 2008; MacLean et al., 2011; Turton et al., 2014; Baggott et al., 2015; Gasser et al., 2015; Schenberg et al., 2016, 2017; Belser et al., 2017; Liechti et al., 2017; Nour and Carhart-Harris, 2017; Watts et al., 2017). Therefore, PAP can deepen understanding of which psychological contents of the therapeutic experience are most relevant for treatment outcomes (Nour et al., 2016; Preller and Vollenweider, 2016; Schenberg et al., 2016, 2017; Carhart-Harris et al., 2017a). This can not only foster improvements in PAP but corroborates the importance of biopsychosocial aspects in psychiatric explanations. A rich methodological integration can help develop theoretical constructs that are not excessively reductionistic. Thus, PAP can conceptually enrich psychiatric explanations for mental disorders and their treatment. If neglect, trauma, childhood adversities, poverty, abuse, and deprivation—i.e., mental injuries—can have lasting negative consequences for mental health, it is also logically plausible that positive, cathartic experiences, sometimes of the mystical type, reliably achieved in PAP, can induce long lasting positive mental health outcomes. Indeed, in the 1950's and 60's, before drug scheduling and cessation of clinical studies with psychedelics, and before neuroscience took central stage in psychiatric understanding of mental disorders, pioneer psychiatrists like Stanislav Grof and Sidney Cohen already questioned the fundamental theoretical grounds of mental disorders (Grof, 1971, 1998, 2012; Cohen, 1972). Based on theirs' and others' experiences in non-ordinary states of consciousness with positive therapeutic outcomes (termed “holotropic” and “unsane,” respectively), they made radical theoretical proposals that can still be relevant to psychiatry, as it was for psychology (Grob and Bossis, 2017). It is thus possible that instead of brain dysfunctions causing discrete disorders treated with specific drugs, psychiatry can conceptualize mental injuries causing suffering that can be optimally treated with holistic approaches (Figure 1), including those which modulate the state of consciousness. This can greatly contribute to the understanding of how social circumstances and adverse life experiences shape mental health and brain activity, and how meaningful treatment experiences foster resilience.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was funded by Phaneros, a Brazilian startup founded by the author.

Conflict of Interest Statement

As founder of a startup company the author has a potential conflict of interest due to his involvement with the design of clinical trials with psychedelics in Brazil. He has not been directly involved with any of the previous clinical trials cited in the article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Leor Roseman for proofreading and for advancing the notion of experience efficacy, mindthegraph.com for the central icon used in Figure 1 and Raoni Rossi for Figure design.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeutic-area/17/psychiatry-psychology

2. ^See also https://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/

3. ^See MAPS treatment manual http://www.maps.org/research-archive/mdma/MDMA-Assisted-Psychotherapy-Treatment-Manual-Version7-19Aug15-FINAL.pdf

4. ^https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N64ynqSb9hk

5. ^http://www.cchr.org/sites/default/files/The_Side_Effects_of_Common_Psychiatric_Drugs.pdf">http://www.cchr.org/sites/default/files/The_Side_Effects_of_Common_Psychiatric_Drugs.pdf

References

Abraham, H., Aldridge, A. M., and Gogia, P. (1996). The psychopharmacology of hallucinogens. Neuropsychopharmacology 14, 285–298. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00136-2

Alper, K. R. (2001). Ibogaine: a review. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 56, 1–38. doi: 10.1016/S0099-9598(01)56005-8

Alper, K. R., Stajić, M., and Gill, J. R. (2012). Fatalities temporally associated with the ingestion of ibogaine. J. Forensic Sci. 57, 398–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.02008.x

Amoroso, T. (2016). Ecstasy research: will increasing observational data aid our understanding of MDMA? Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30345-5

Amoroso, T., and Workman, M. (2016). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy: a preliminary meta-analysis and comparison to prolonged exposure therapy. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 595–600. doi: 10.1177/0269881116642542

Baggott, M. J., Kirkpatrick, M. G., Bedi, G., and de Wit, H. (2015). Intimate insight: MDMA changes how people talk about significant others. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 669–677. doi: 10.1177/0269881115581962

Ballard, E. D., Ionescu, D. F., Vande Voort, J. L., Niciu, M. J., Richards, E. M., Luckenbaugh, D. A., et al. (2014). Improvement in suicidal ideation after ketamine infusion: relationship to reductions in depression and anxiety. J. Psychiatr. Res. 58, 161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.027

Barrett, F. S., Robbins, H., Smooke, D., Brown, J. L., and Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Qualitative and quantitative features of music reported to support peak mystical experiences during psychedelic therapy sessions. Front. Psychol. 8:1238. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01238

Belser, A. B., Agin-Liebes, G., Swift, T. C., Terrana, S., Devenot, N., Friedman, H. L., et al. (2017). Patient experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Humanist Psychol. 57, 354–388. doi: 10.1177/0022167817706884

Berkman, E. T., and Falk, E. B. (2013). Beyond brain mapping: using neural measures to predict real-world outcomes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 45–50. doi: 10.1177/0963721412469394

Bloch, M. W., Wasylink, S., Landeros-Weisenberger, A., Panza, K. E., Billingslea, E., Leckman, J. F., et al. (2012). Effects of ketamine in treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.028

Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C. R., and Strassman, R. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144

Bonny, H. L., and Pahnke, W. N. (1972). The use of music in psychedelic (LSD) psychotherapy. J. Music Ther. 9, 64–87. doi: 10.1093/jmt/9.2.64

Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 16, 5–13. doi: 10.1002/wps.20375

Bouso, J. C., Doblin, R., Farré, M., Alcázar, M. A., and Gómez-Jarabo, G. (2008). MDMA-assisted psychotherapy using low doses in a small sample of women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychoactive Drugs 40, 225–236. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400637

Brown, T. K. (2013). Ibogaine in the treatment of substance dependence. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 6, 3–16. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990001

Brown, T. K., and Alper, K. (2017). Treatment of opioid use disorder with ibogaine: detoxification and drug use outcomes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 44, 24–36. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1320802

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C. M. J., Rucker, J., Watts, R., Erritzoe, D. E., et al. (2017c). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology 235, 399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., et al. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 619–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Haijen, E., Kaelen, M., and Watts, R. (2017a). Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology 235, 547–550. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4701-y

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Hellyer, P. J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., et al. (2014a). The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:20. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Bolstridge, M., Demetriou, L., Pannekoek, J. N., Wall, M. B., et al. (2017b). Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 7:13187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13282-7

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Wall, M. B., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Ferguson, B., De Meer, I., et al. (2014b). The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD-fMRI responses to favourite and worst autobiographical memories. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 17, 527–540. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001405

Casey, B. J., Craddock, N., Cuthbert, B. N., Hyman, S. E., Lee, F. S., and Ressler, K. J. (2013). DSM-5 and RDoC: progress in psychiatry research? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 810–814. doi: 10.1038/nrn3621

Catalá-López, F., Gènova-Maleras, R., Vieta, E., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., Svensson, M., Jönsson, B., et al. (2013). The increasing burden of mental and neurological disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 1337–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.04.001

Chapman, S. C., and Horne, R. (2013). Medication nonadherence and psychiatry. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 26, 446–452. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283642da4

Coyle, C. M., and Laws, K. R. (2015). The use of ketamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 30, 152–163. doi: 10.1002/hup.2475

Dakwar, E., Hart, C. L., Levin, F. R., Nunes, E. V., and Foltin, R. W. (2016). Cocaine self-administration disrupted by the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist ketamine: a randomized, crossover trial. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 76–81. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.39

Dakwar, E., Levin, F., Foltin, R. W., Nunes, E. V., and Hart, C. L. (2014). The effects of subanesthetic ketamine infusions on motivation to quit and cue-induced craving in cocaine-dependent research volunteers. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.009

Deacon, B. J. (2013). The biomedical model of mental disorder: a critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 846–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007

Dos Santos, R. G., Osório, F. L., Crippa, J. A. S., Riba, J., Zuardi, A. W., and Hallak, J. E. C. (2016). Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 6, 193–213. doi: 10.1177/2045125316638008

Downing, N. S., Aminawung, J. A., Shah, N. D., Krumholz, H. M., and Ross, J. S. (2014). Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005–2012. JAMA 311, 368–377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282034

Downing, N. S., Shah, N. D., Aminawung, J. A., Pease, A. M., Zeitoun, J.-D., Krumholz, H. M., et al. (2017). Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the us food and drug administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA 317, 1854–1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5150

Dyck, E. (2005). Flashback: psychiatric Experimentation with LSD in historical perspective. Can. J. Psychiatry 50, 381–388. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000703

Eisner, B. (1997). Set, setting, and matrix. J. Psychoactive Drugs 29, 213–216. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400190

Feder, A., Parides, M. K., Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Morgan, J. E., Saxena, S., et al. (2014). Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 681–688. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62

Fond, G., Loundou, A., Rabu, C., Macgregor, A., Lançon, C., Brittner, M., et al. (2014). Ketamine administration in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology 231, 3663–3676. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3664-5

Frances, A. (2014a). RDoC is necessary, but very oversold. World Psychiatry 13, 47–49. doi: 10.1002/wps.20102

Frances, A. (2014b). Resuscitating the biopsychosocial model. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 496–497. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00058-3

Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., and Borsboom, D. (2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

Gable, R. S. (2004). Comparison of acute lethal toxicity of commonly abused psychoactive substances. Addiction 99, 686–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00744.x

Gálvez, V., Li, A., Huggins, C., Glue, P., Martin, D., Somogyi, A. A., et al. (2018). Repeated intranasal ketamine for treatment-resistant depression – the way to go? Results from a pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 32, 397–407. doi: 10.1177/0269881118760660

Garcia-Romeu, A., Griffiths, R. R., and Johnson, M. W. (2015). Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 7, 157–164. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107121331

Gasser, P., Holstein, D., Michel, Y., Doblin, R., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Passie, T., et al. (2014). Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 202, 513–520. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000113

Gasser, P., Kirchner, K., and Passie, T. (2015). LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 57–68. doi: 10.1177/0269881114555249

Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. J., Carducci, M. A., Umbricht, A., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., et al. (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1181–1197. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513

Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., McCann, U., and Jesse, R. (2011). Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology 218, 649–665. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2358-5

Grob, C. S., and Bossis, A. (2017). Humanistic psychology, psychedelics, and the transpersonal vision. J. Humanist. Psychol. 57, 315–318. doi: 10.1177/0022167817715960

Grob, C. S., Danforth, A. L., Chopra, G. S., Hagerty, M., McKay, C. R., Halberstadt, A. L., et al. (2011). Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 71–78. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116

Grof, S. (1971). Varieties of transpersonal experiences: observations from LSD psychotherapy. J. Transpers. Psychol. 4, 1–45.

Grof, S. (1998). Human nature and the nature of reality: conceptual challenges from consciousness research. J. Psychoactive Drugs 30, 343–357. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399710

Grof, S. (2008). LSD Psychotherapy. Ben Lomond, CA: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

Grof, S. (2012). Revision and re-enchantment of psychology: legacy of a half a century of consciousness research. J. Transpers. Psychol. 44, 137–163. doi: 10.1002/9781118591277.ch5

Hartogsohn, I. (2016). Set and setting, psychedelics and the placebo response: an extra-pharmacological perspective on psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1259–1267. doi: 10.1177/0269881116677852

Hartogsohn, I. (2018). The meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics and their mediator role in psychedelic therapy, spirituality, and creativity. Front. Neurosci. 12:129. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00129

Hendricks, P. S., Clark, C. B., Johnson, M. W., Fontaine, K. R., and Cropsey, K. L. (2014). Hallucinogen use predicts reduced recidivism among substance-involved offenders under community corrections supervision. J. Psychopharmacol. 28, 62–66. doi: 10.1177/0269881113513851

Hendricks, P. S., Thorne, C. B., Clark, C. B., Coombs, D. W., and Johnson, M. W. (2015). Classic psychedelic use is associated with reduced psychological distress and suicidality in the United States adult population. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 280–288. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565653

Hyman, S. E. (2013). Psychiatric drug development: diagnosing a crisis. Cerebrum 2013:5. Available Online at: http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum/2013/Psychiatric_Drug_Development__Diagnosing_a_Crisis/

Iadarola, N. D., Niciu, M. J., Richards, E. M., Vande Voort, J. L., Ballard, E. D., Lundin, N. B., et al. (2015). Ketamine and other N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in the treatment of depression: a perspective review. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 6, 97–114. doi: 10.1177/2040622315579059

Insel, T. R. (2014). The NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project: precision medicine for psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 395–397. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020138

Insel, T. R., and Cuthbert, B. N. (2015). Brain disorders? Precisely. Science 348, 499–500. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2358

Johansen, P.-Ø., and Krebs, T. S. (2015). Psychedelics not linked to mental health problems or suicidal behavior: a population study. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 270–279. doi: 10.1177/0269881114568039

Johnson, M., Richards, W., and Griffiths, R. (2008). Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J. Psychopharmacol. 22, 603–620. doi: 10.1177/0269881108093587

Johnson, M. W., Andrew Sewell, R., and Griffiths, R. R. (2012). Psilocybin dose-dependently causes delayed, transient headaches in healthy volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 123, 132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.029

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M. P., and Griffiths, R. R. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. 28, 983–992. doi: 10.1177/0269881114548296

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., and Griffiths, R. R. (2017b). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 43, 55–60. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

Johnson, M. W., and Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Potential therapeutic effects of psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics 14, 734–740. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0542-y

Johnstone, L. (2017). Psychological formulation as an alternative to psychiatric diagnosis. J. Humanist. Psychol. 58, 30–46. doi: 10.1177/0022167817722230

Kaelen, M., Barrett, F. S., Roseman, L., Lorenz, R., Family, N., Bolstridge, M., et al. (2015). LSD enhances the emotional response to music. Psychopharmacology 232, 3607–3614. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4014-y

Kishimoto, T., Chawla, J. M., Hagi, K., Zarate, C. A., Kane, J. M., Bauer, M., et al. (2016). Single-dose infusion ketamine and non-ketamine N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists for unipolar and bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of efficacy, safety and time trajectories. Psychol. Med. 46, 1459–1472. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000064

Koenig, X., and Hilber, K. (2015). The anti-addiction drug ibogaine and the heart: a delicate relation. Molecules 20, 2208–2228. doi: 10.3390/molecules20022208

Koenig, X., Kovar, M., Boehm, S., Sandtner, W., and Hilber, K. (2014). Anti-addiction drug ibogaine inhibits hERG channels: a cardiac arrhythmia risk. Addict. Biol. 19, 237–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00447.x

Kraehenmann, R., Preller, K. H., Scheidegger, M., Pokorny, T., Bosch, O. G., Seifritz, E., et al. (2015). Psilocybin-Induced decrease in amygdala reactivity correlates with enhanced positive mood in healthy volunteers. Biol. Psychiatry 78, 572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.010

Kraemer, H. C. (2015). Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) and the iDSM/i —two methodological approaches to mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 1163–1164. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2134

Krebs, T. S., and Johansen, P.-Ø. (2012). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Psychopharmacol. 26, 994–1002. doi: 10.1177/0269881112439253

Krebs, T. S., and Johansen, P.-Ø. (2013). Psychedelics and mental health: a population study. PLoS ONE 8:e63972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063972

Krupitsky, E. M., Burakov, A. M., Dunaevsky, I. V., Romanova, T. N., Slavina, T. Y., and Grinenko, A. Y. (2007). Single versus repeated sessions of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for people with heroin dependence. J. Psychoactive Drugs 39, 13–19. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399860

Krupitsky, E. M., and Grinenko, A. Y. (1997). Ketamine psychedelic therapy (KPT): review of the results of ten years of research. J. Psychoactive Drugs 29, 165–183. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400185

Kukreja, S., Kalra, G., Shah, N., and Shrivastava, A. (2013). Polypharmacy in psychiatry: a review. Mens Sana Monogr. 11, 82–99. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.104497

Kupferschmidt, K. (2017). All clear for the decisive trial of ecstasy in PTSD patients. Science doi: 10.1126/science.aap7739

Lee, E. E., Della Selva, M. P., Liu, A., and Himelhoch, S. (2015). Ketamine as a novel treatment for major depressive disorder and bipolar depression: a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 37, 178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.01.003

Lefèvre, T., Lepresle, A., and Chariot, P. (2014). An alternative to current psychiatric classifications: a psychological landscape hypothesis based on an integrative, dynamical and multidimensional approach. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 9:12. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-9-12

Lewis, C. R., Preller, K. H., Kraehenmann, R., Michels, L., Staempfli, P., and Vollenweider, F. X. (2017). Two dose investigation of the 5-HT-agonist psilocybin on relative and global cerebral blood flow. Neuroimage 159, 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.020

Liechti, M. E., Dolder, P. C., and Schmid, Y. (2017). Alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences after acute LSD in humans. Psychopharmacology 234, 1499–1510. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4453-0

Linden, D. E. (2012). The challenges and promise of neuroimaging in psychiatry. Neuron 73, 8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.014

Luckenbaugh, D. A., Niciu, M. J., Ionescu, D. F., Nolan, N. M., Richards, E. M., Brutsche, N. E., et al. (2014). Do the dissociative side effects of ketamine mediate its antidepressant effects? J. Affect. Disord. 159, 56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.017

MacLean, K. A., Johnson, M. W., and Griffiths, R. R. (2011). Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J. Psychopharmacol. 25, 1453–1461. doi: 10.1177/0269881111420188

Majić, T., Schmidt, T. T., and Gallinat, J. (2015). Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: when and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences? J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 241–253. doi: 10.1177/0269881114568040

McGirr, A., Berlim, M. T., Bond, D. J., Fleck, M. P., Yatham, L. N., and Lam, R. W. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychol. Med. 45, 693–704. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001603

McHugh, R. K., Nielsen, S., and Weiss, R. D. (2015). Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 48, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.004

Medic, G., Higashi, K., Littlewood, K. J., Diez, T., Granström, O., and Kahn, R. S. (2013). Dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 9, 119–131. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S39303

Miller, G. (2010). Is pharma running out of brainy ideas? Science 329, 502–504. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5991.502

Mion, G. (2017). History of anaesthesia: the ketamine story - past, present and future. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 34, 571–575. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000638

Mithoefer, M. C., Grob, C. S., and Brewerton, T. D. (2016). Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: psilocybin and MDMA. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 481–488. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00576-3

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., and Doblin, R. (2011). The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J. Psychopharmacol. 25, 439–452. doi: 10.1177/0269881110378371

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., Martin, S. F., Yazar-Klosinski, B., et al. (2013). Durability of improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and absence of harmful effects or drug dependency after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy: a prospective long-term follow-up study. J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 28–39. doi: 10.1177/0269881112456611

Mithoefer, M. C., Mithoefer, A. T., Feduccia, A. A., Jerome, L., Wymer, J., Holland, J., et al. (2018). 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 486–497. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4

Mojtabai, R., and Olfson, M. (2010). National trends in psychotropic medication polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67:26. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.175

Murrough, J. W., Soleimani, L., DeWilde, K. E., Collins, K. A., Lapidus, K. A., Iacoviello, B. M., et al. (2015). Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 45, 3571–3580. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001506

Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Moran, R. J., Brookes, M. J., Williams, T. M., Errtizoe, D., et al. (2013). Broadband cortical desynchronization underlies the human psychedelic state. J. Neurosci. 33, 15171–15183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-13.2013

Nichols, D. E., Johnson, M. W., and Nichols, C. D. (2017). Psychedelics as medicines: an emerging new paradigm. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 101, 209–219. doi: 10.1002/cpt.557

Noller, G. E., Frampton, C. M., and Yazar-Klosinski, B. (2017). Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 44, 37–46. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1310218

Nour, M. M., and Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2017). Psychedelics and the science of self-experience. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 177–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.194738

Nour, M. M., Evans, L., Nutt, D., and Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2016). Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10:269. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

Novak, S. P., Håkansson, A., Martinez-Raga, J., Reimer, J., Krotki, K., and Varughese, S. (2016). Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the European Union. BMC Psychiatry 16:274. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0909-3

Nutt, D. J., King, L. A., and Nichols, D. E. (2013). Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 577–585. doi: 10.1038/nrn3530

Nutt, D. J., King, L. A., and Phillips, L. D. (2010). Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet 376, 1558–1565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6

Oehen, P., Traber, R., Widmer, V., and Schnyder, U. (2013). A randomized, controlled pilot study of MDMA (± 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of resistant, chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 40–52. doi: 10.1177/0269881112464827

Pahnke, W. N., Kurland, A. A., Unger, S., Savage, C., and Grof, S. (1970). The experimental use of psychedelic (LSD) psychotherapy. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 212, 1856–1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.1970.03170240060010

Parnas, J. (2014). The RDoC program: psychiatry without psyche? World Psychiatry 13, 46–47. doi: 10.1002/wps.20101

Parsaik, A. K., Singh, B., Khosh-Chashm, D., and Mascarenhas, S. S. (2015). Efficacy of ketamine in bipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 21, 427–435. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000106

Passie, T., Halpern, J. H., Stichtenoth, D. O., Emrich, H. M., and Hintzen, A. (2008). The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 14, 295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x

Plakun, E. (2012). Treatment resistance and psychodynamic psychiatry: concepts psychiatry needs from psychoanalysis. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 40, 183–209. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2012.40.2.183

Plakun, E. M. (2006). A view from riggs—treatment resistance and patient authority: i. a psychodynamic perspective on treatment resistance. J. Am. Acad. Psychoanal. Dyn. Psychiatry 34, 349–366. doi: 10.1521/jaap.2006.34.2.349

Preller, K. H., and Vollenweider, F. X. (2016). Phenomenology, structure, and dynamic of psychedelic states. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 36, 221–256. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_459

Price, R. B., Iosifescu, D. V., Murrough, J. W., Chang, L. C., Al Jurdi, R. K., Iqbal, S. Z., et al. (2014). Effects of ketamine on explicit and implicit suicidal cognition: a randomized controlled trial in treatment-resistant depression. Depress. Anxiety 31, 335–343. doi: 10.1002/da.22253

Richards, W. A. (2017). Psychedelic psychotherapy: insights from 25 years of research. J. Humanist. Psychol. 57, 323–337. doi: 10.1177/0022167816670996

Rodriguez, C. I., Kegeles, L. S., Levinson, A., Feng, T., Marcus, S. M., Vermes, D., et al. (2013). randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharm 38, 2475–2483. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.150

Rodriguez, C. I., Wheaton, M., Zwerling, J., Steinman, S. A., Sonnenfeld, D., Galfalvy, H., et al. (2016). Can exposure-based CBT extend the effects of intravenous ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder? An open-label trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 408–409. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15l10138

Romeo, B., Choucha, W., Fossati, P., and Rotge, J.-Y. (2015). Meta-analysis of short- and mid-term efficacy of ketamine in unipolar and bipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 230, 682–688. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.032

Rose, N. (2016). Neuroscience and the future for mental health? Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 25, 95–100. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000621

Roseman, L., Nutt, D. J., and Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front. Pharmacol. 8:974. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00974

Ross, S., Bossis, A., Guss, J., Agin-Liebes, G., Malone, T., Cohen, B., et al. (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1165–1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512

Sahakian, B. J., Malloch, G., and Kennard, C. (2010). A UK strategy for mental health and wellbeing. Lancet 375, 1854–1855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60817-3

Saleemi, S., Pennybaker, S. J., Wooldridge, M., and Johnson, M. W. (2017). Who is “Molly”? MDMA adulterants by product name and the impact of harm-reduction services at raves. J. Psychopharmacol. 31, 1056–1060. doi: 10.1177/0269881117715596

Schartner, M. M., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Barrett, A. B., Seth, A. K., and Muthukumaraswamy, S. D. (2017). Increased spontaneous MEG signal diversity for psychoactive doses of ketamine, LSD and psilocybin. Sci. Rep. 7:46421. doi: 10.1038/srep46421

Scheidegger, M., Henning, A., Walter, M., Lehmann, M., Kraehenmann, R., Boeker, H., et al. (2016). Ketamine administration reduces amygdalo-hippocampal reactivity to emotional stimulation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 1941–1952. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23148

Schenberg, E. E., de Castro Comis, M. A., Alexandre, J. F. M., Chaves, B. D. R., Tófoli, L. F., and Silveria, D. X. (2016). Treating drug dependence with the aid of ibogaine: a qualitative study. J. Psychedelic Stud. 1, 10–19. doi: 10.1177/0269881114552713

Schenberg, E. E., de Castro Comis, M. A., Alexandre, J. F. M., Tófoli, L. F., Chaves, B. D. R., and da Silveira, D. X. (2017). A phenomenological analysis of the subjective experience elicited by ibogaine in the context of a drug dependence treatment. J. Psychedelic Stud. 1, 74–83. doi: 10.1556/2054.01.2017.007

Schenberg, E. E., de Castro Comis, M. A., Chaves, B. R., and da Silveira, D. X. (2014). Treating drug dependence with the aid of ibogaine: a retrospective study. J. Psychopharmacol. 28, 993–1000. doi: 10.1556/2054.01.2016.002

Short, B., Fong, J., Galvez, V., Shelker, W., and Loo, C. K. (2017). Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 65–78. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30272-9

Smith, D. E., Raswyck, G. E., and Dickerson Davidson, L. (2014). From hofmann to the haight ashbury, and into the future: the past and potential of Lysergic Acid Diethlyamide. J. Psychoactive Drugs 46, 3–10. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.873684

Stephan, K. E., Bach, D. R., Fletcher, P. C., Flint, J., Frank, M. J., Friston, K. J., et al. (2016a). Charting the landscape of priority problems in psychiatry, part 1: classification and diagnosis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00361-2

Stephan, K. E., Binder, E. B., Breakspear, M., Dayan, P., Johnstone, E. C., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., et al. (2016b). Charting the landscape of priority problems in psychiatry, part 2: pathogenesis and aetiology. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 84–90. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00360-0

Studerus, E., Kometer, M., Hasler, F., and Vollenweider, F. X. (2011). Acute, subacute and long-term subjective effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of experimental studies. J. Psychopharmacol. 25, 1434–1452. doi: 10.1177/0269881110382466

Tagliazucchi, E., Carhart-Harris, R., Leech, R., Nutt, D., and Chialvo, D. R. (2014). Enhanced repertoire of brain dynamical states during the psychedelic experience. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 5442–5456. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22562

Togni, L. R., Lanaro, R., Resende, R. R., and Costa, J. L. (2015). The variability of ecstasy tablets composition in Brazil. J. Forensic Sci. 60, 147–151. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12584

Turton, S., Nutt, D. J., and Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2014). A qualitative report on the subjective experience of intravenous psilocybin administered in an FMRI environment. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 7, 117–127. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107120930

Tylš, F., Páleníček, T., and Horáček, J. (2014). Psilocybin–summary of knowledge and new perspectives. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24, 342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006

van Amsterdam, J., Opperhuizen, A., and van den Brink, W. (2011). Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 59, 423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006

van Gerven, J., and Cohen, A. (2011). Vanishing clinical psychopharmacology. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 72, 1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04021.x

Vizeli, P., and Liechti, M. E. (2017). Safety pharmacology of acute MDMA administration in healthy subjects. J. Psychopharmacol. 31, 576–588. doi: 10.1177/0269881117691569

Vogels, N., Brunt, T. M., Rigter, S., van Dijk, P., Vervaeke, H., and Niesink, R. J. M. (2009). Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands: 1993–2008. Addiction 104, 2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02707.x

Vollenweider, F. X., and Kometer, M. (2010). The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 642–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn2884

Vrolijk, R. Q., Brunt, T. M., Vreeker, A., and Niesink, R. J. M. (2017). Is online information on ecstasy tablet content safe? Addiction 112, 94–100. doi: 10.1111/add.13559

Wacker, D., Wang, S., McCorvy, J. D., Betz, R. M., Venkatakrishnan, A. J., Levit, A., et al. (2017). Crystal structure of an LSD-bound human serotonin receptor. Cell 168, 377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.033

Wakefield, J. C. (2014). Wittgenstein's nightmare: why the RDoC grid needs a conceptual dimension. World Psychiatry 13, 38–40. doi: 10.1002/wps.20097

Wan, L.-B., Levitch, C. F., Perez, A. M., Brallier, J. W., Iosifescu, D. V., Chang, L. C., et al. (2015). Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 247–252. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08852

Watts, R., Day, C., Krzanowski, J., Nutt, D., and Carhart-Harris, R. (2017). Patients' accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J. Humanist. Psychol. 57, 520–564. doi: 10.1177/0022167817709585

Weinberger, D. R., and Radulescu, E. (2016). Finding the elusive psychiatric “lesion” with 21st-century neuroanatomy: a note of caution. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 27–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060753

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., et al. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 382, 1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

Wilkinson, S. T., Wright, D., Fasula, M. K., Fenton, L., Griepp, M., Ostroff, R. B., et al. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy may sustain antidepressant effects of intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Psychother. Psychosom. 86, 162–167. doi: 10.1159/000457960

Winkelman, M. (2014). Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 7, 101–116. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107120011

Wood, D. M., Stribley, V., Dargan, P. I., Davies, S., Holt, D. W., and Ramsey, J. (2011). Variability in the 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine content of “ecstasy” tablets in the UK. Emerg. Med. J. 28, 764–765. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.092270

Wright, E. R., Kooreman, H. E., Greene, M. S., Chambers, R. A., Banerjee, A., and Wilson, J. (2014). The iatrogenic epidemic of prescription drug abuse: county-level determinants of opioid availability and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 138, 209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.002

Xu, Y., Hackett, M., Carter, G., Loo, C., Gálvez, V., Glozier, N., et al. (2016). Effects of low-dose and very low-dose ketamine among patients with major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 19:pyv124. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv124

Keywords: psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, LSD, MDMA, ibogaine, psilocybin, ketamine, explanation in neuroscience, states of consciousness

Citation: Schenberg EE (2018) Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and Development. Front. Pharmacol. 9:733. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00733

Received: 27 November 2017; Accepted: 18 June 2018;

Published: 05 July 2018.

Edited by:

Ede Frecska, University of Debrecen, HungaryReviewed by:

Giovanni Laviola, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ItalyCsaba Szummer, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, Hungary

Copyright © 2018 Schenberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eduardo Ekman Schenberg, ZWR1YXJkb0BwaGFuZXJvcy5jbw==

Eduardo Ekman Schenberg

Eduardo Ekman Schenberg