- 1Axe Neurosciences, Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec, Québec, QC, Canada

- 2Département de Psychiatrie et Neurosciences, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada

- 3John van Geest Centre for Brain Repair, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

The role of glial cells in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative conditions of the central nervous system (CNS) is now well established (as is discussed in other reviews in this special issue of Frontiers in Neuropharmacology). What is less clear is whether there are changes in these same cells in terms of their behavior and function in response to invasive experimental therapeutic interventions for these diseases. This has, and will continue to become more of an issue as we enter a new era of novel treatments which require the agent to be directly placed/infused into the CNS such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), cell transplants, gene therapies and growth factor infusions. To date, all of these treatments have produced variable outcomes and the reasons for this have been widely debated but the host astrocytic and/or microglial response induced by such invasively delivered agents has not been discussed in any detail. In this review, we have attempted to summarize the limited published data on this, in particular we discuss the small number of human post-mortem studies reported in this field. By so doing, we hope to provide a better description and understanding of the extent and nature of both the astrocytic and microglial response, which in turn could lead to modifications in the way these therapeutic interventions are delivered.

Introduction

Over the last 30 years, there has been a burgeoning of new therapeutic approaches to treat chronic neurodegenerative conditions of the central nervous system (CNS). These approaches have essentially been of two main types:

(i) Better symptomatic agents most notably deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's Disease (PD) as well as gene therapy approaches (e.g., AAV2-GAD; ProSavin®; hAADC gene therapy).

(ii) Restorative agents such as growth factor administration or cell transplants. This has involved either directly infusing growth factors into the CNS (e.g., GDNF in the case of PD) or the use of viral delivery systems (e.g., AAV2-Neurturin). In the case of cell therapies a number of different cell types have been grafted into the diseased brain especially in patients with PD (e.g., adrenal medulla; carotid body; ventral mesencephalon, amongst others) and Huntington's Disease (HD) (fetal striatal cells).

Whilst the efficacy of these approaches has been the subject of many reviews, one area that has received rather less attention is the host response to these therapeutic agents. This involves not only an anticipated and beneficial response (e.g., cell integration, fiber sprouting, synapse formation, and so on) but also a glial reaction to it, involving both astrocytes and microglia. In the adult CNS, astrocytes constitute the predominant glial cell type that function to control the CNS environment by removing excess ions and recycling neurotransmitters, supporting endothelial cells that form the blood-brain-barrier, as well as playing a key role in tissue scarring and repair following injury. In recent years, the importance of cross-communication between astrocytes, as well as between astrocytes and neuronal cells has started to be better understood. Microglial cells, in contrast, have more of a phagocytic function but like astrocytes, are known to release cytokines in inflammatory/infectious conditions. Whilst both astrocytes and microglia react to, and convey messages within their immediate environment, they also can communicate over extended distances through syncytial networks.

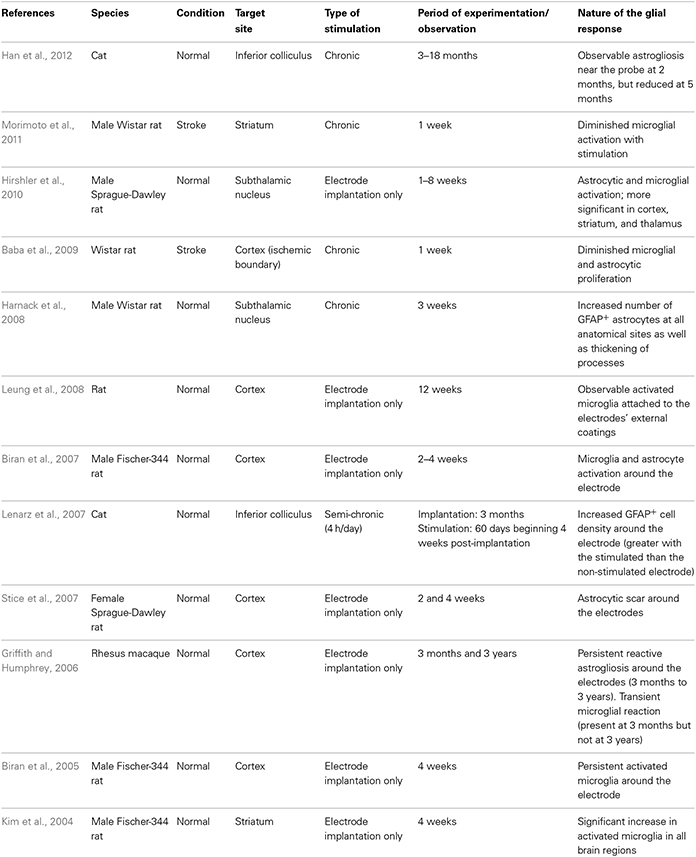

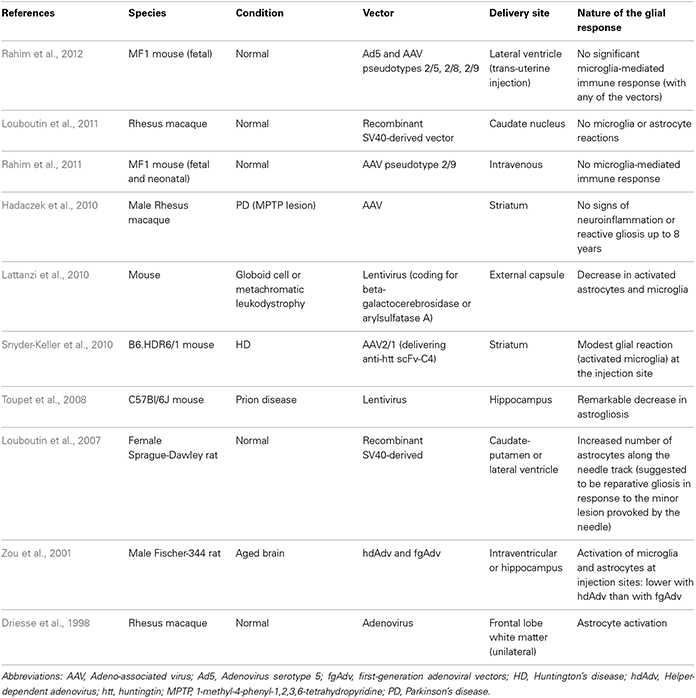

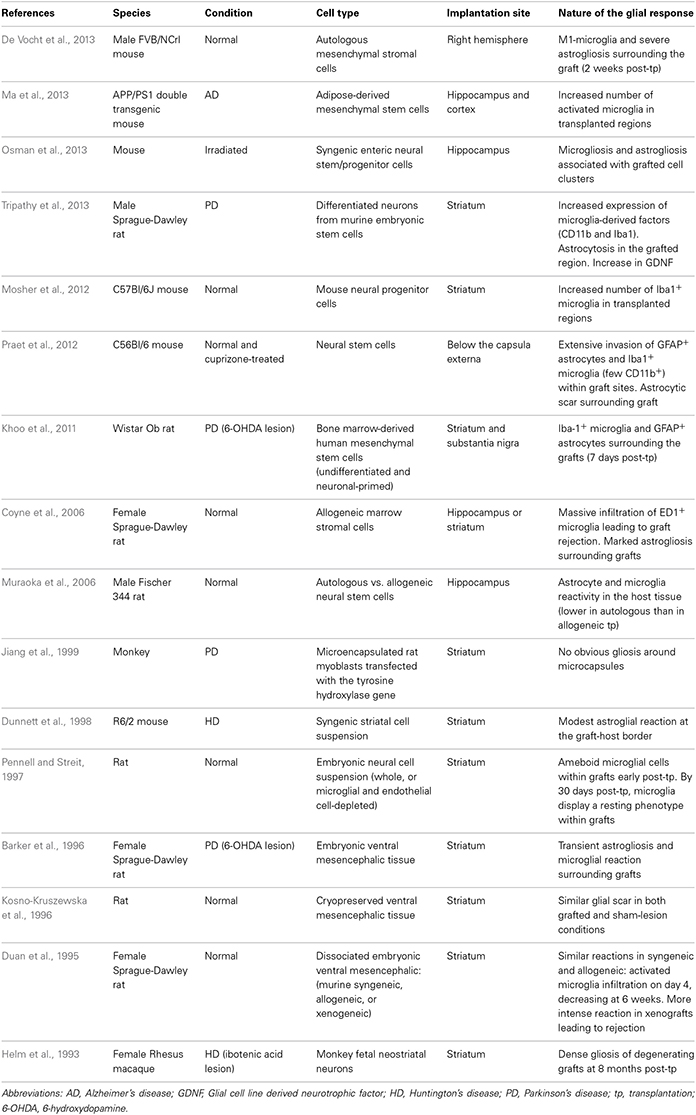

In this review, we will discuss the extent to which the glial response may limit, or possibly augment, the potential effects of intracerebrally delivered therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative disorders. The focus of this mini review will be largely restricted to the astrocytic and microglial responses in human post-mortem studies, as there is no published data on the oligodendroglial response to these types of treatments. However, because of the importance of pre-clinical data in this field, we have also summarized studies that have reported on the nature of the glial response in the context of DBS (Table 1), neurotrophic therapies (Table 2), and neural grafting (Table 3) in vivo.

Deep Brain Stimulation and the Glial Response

In the last 20 years, DBS has been used to treat a range of neurological disorders, most notably in patients with advancing PD and those with essential tremor refractory to medical therapy (Lyons, 2011). DBS involves applying high frequency stimulation (HFS) via implanted electrodes into strategic CNS nuclei which serves to modulate the output of these nuclei with therapeutic benefits in the majority of patients. This benefit persists for many years and has encouraged the adoption of this approach for a whole range of new indications including neuropsychiatric conditions and pain, as well as in earlier stage PD. However, the host CNS glial response to the implantation of this foreign body and the HFS that it delivers has been the subject of only a few reports, especially in the clinical field.

In contrast, there has been a significant amount of experimental work over the years to look at how the CNS reacts to chronically implanted electrodes, although more often in the context of micro-recording than DBS. This is because micro-recording is a well-established method for studying CNS function and DBS has been developed for use primarily in non-human primates and man rather than rodents. Nevertheless, as one would expect, the insertion of a metal electrode into the parenchyma of the brain will induce an astrocytic response (both in terms of the number and degree of astrocytes activated), the magnitude of which may be dependent, in part, on the electrode architecture (Szarowski et al., 2003; Groothuis et al., 2014), and the biomaterial being used (Ereifej et al., 2011). Studies of this type have led some to look at non-metallic electrodes with the hope that this will induce less of a glial response (Ereifej et al., 2011). For example, stainless-steel, as oppose to platinum-iridium or tungsten electrodes, are more prone to electrolytic dissolution which may increase the likelihood of local cell death and a secondary astroglial response (Harnack et al., 2004).

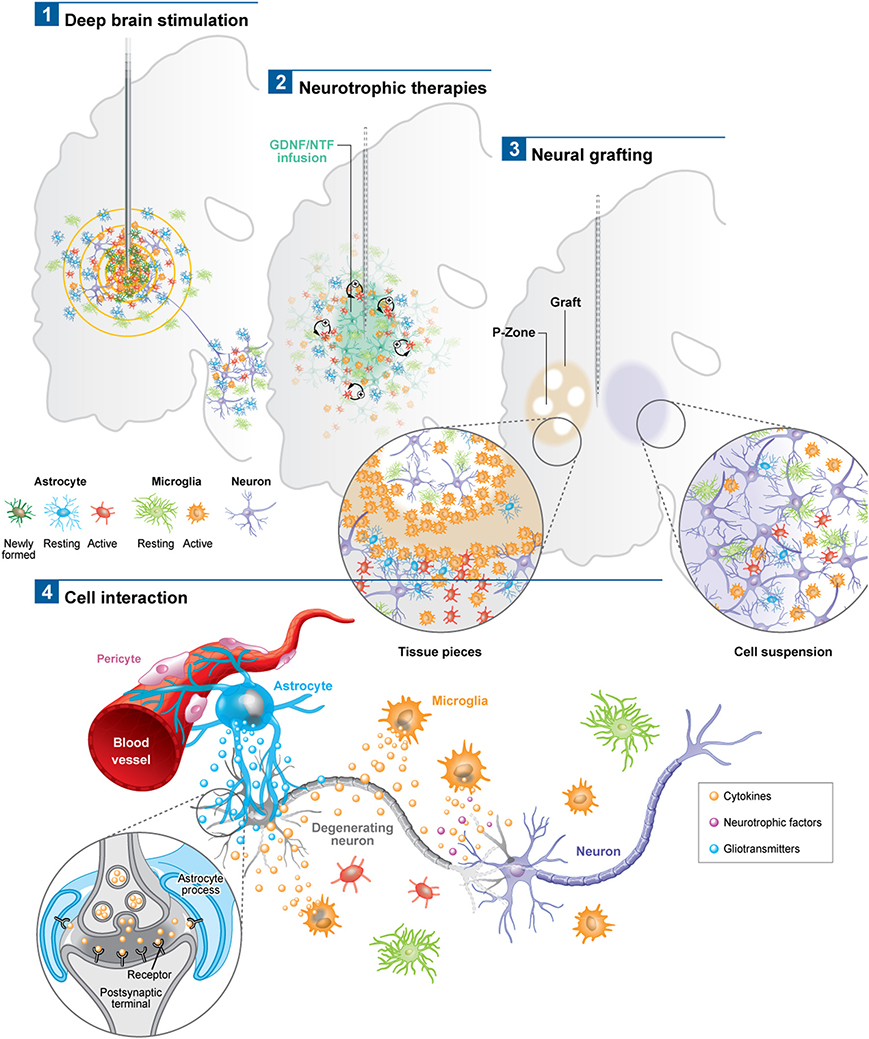

In all cases, the astrocytic and microglial responses—which typically include a change in cell morphology and density of activated cells as well as the release of various pro-inflammatory molecules—are evident soon after implantation (Figure 1.1), persist for years (Jarraya et al., 2003) and seem to occur independently of where the electrode is placed in the brain and the clinical condition for which it is being used (Moss et al., 2004). The extent to which this reactive astroglial and microglial response changes over time is unknown (although see Griffith and Humphrey, 2006), as are the effects that such changes have on the efficacy of current delivered by the stimulating electrode. Nevertheless, a number of experimental studies have shown that these glial reactions could adversely affect electrode impedance and thus efficacy (Spataro et al., 2005; Polikov et al., 2009; Frampton et al., 2010). Indeed, there is even some evidence that chronically implanted electrodes cause sustained local inflammation and neurodegeneration (McConnell et al., 2009). For example, in a study performed in rodents, McConnell et al. demonstrated that heightened levels of chronic inflammation correlated with increased neuronal and dendritic loss, a phenomenon which was more pronounced at 16 weeks than at 8 weeks post-implantation. Remarkably, this local but progressive neurodegeneration was accompanied by axonal pathology, as evidenced by tau phosphorylation, a prominent feature of neurodegenerative conditions. Exactly how this tau pathology arises is unclear but it does suggest that inflammation may be able to induce some forms of proteinopathy.

Figure 1. Schematic depicting the astroglial and microglial responses to a variety of invasive experimental therapeutic approaches being trialed for neurodegenerative disorders (1–3). (4) Potential cell interactions that may further influence the outcome of the therapeutic intervention, or, that could be used to potentiate the effects of these therapies. For example the astrocytic response may lead to the release of trophic factors, the modulation of local blow flow as well as the activation of axonal circuits via tripartite synapses. The microglial response may produce both neuroprotective and neurotoxic products, all of which may impact not only on local neurons but also on local vasculature to influence the efficacy of the delivered therapeutic agent. Note: p-zone refers to areas of the graft expressing markers for striatal cells.

Additionally, in a recent paper by Vedam-Mai et al. they have interestingly shown in patients that there are variable responses to chronic DBS electrodes, ranging from minimal astrocytosis and microglia activation in the majority of cases to the formation of a dense collagenous band at the electrode tip in at least one case (Vedam-Mai et al., 2012b). In this paper, the authors comment on the possibility of gliotic encapsulation altering electrical thresholds of the stimulating electrode and with this its clinical efficacy—although this study would suggest that this is a rare event. Understanding and predicting such tissue responses to the stimulating and recording electrodes, or even just cannula guidewires, is critical as the magnitude of the foreign body response can lead to electrode failure (Groothuis et al., 2014) and suboptimal clinical outcomes. However, in this study, they did not look to see whether the inflammation induced altered the pathology within the brain, which is of course not straightforward in patients with pre-existing neurodegenerative disorders.

Based on data of this type, some experimental studies have sought to minimize this microglial and inflammatory response, or so-called foreign body response, by using agents such as minocycline and steroids in combination with the stimulating electrode (Rennaker et al., 2007; Zhong and Bellamkonda, 2007) as well as nanoparticle delivery systems (Kim and Martin, 2006; Mercanzini et al., 2010). These different strategies are all predicated on the grounds that suppressing the microglial/inflammatory response to DBS will improve the brain-electrode interface in these chronically implanted micro-electrodes and thus maintain efficacy. Whether this is really a problem in patients with DBS is unknown (see above and Vedam-Mai et al., 2012a,b), but one interesting study by Hirshler et al. (2010) (see also Table 1) in rats showed that merely inserting an electrode into the brain could induce widespread and chronic (i.e., over weeks) neuroinflammation which was correlated with deficits in cognitive function—deficits which are also seen in patients who have had DBS (Witt et al., 2008). No such studies using microglia markers and positron emission tomography (PET) have been performed clinically, although a recent study found that in patients with DBS of the pedunculopontine nucleus, there was an improvement in cognition in association with improvements in cortical activity as measured by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET (Stefani et al., 2010). This aspect of DBS, namely its ability to induce widespread inflammation (i.e., not just at the site of implantation of the electrode) across whole neural networks may prove to be much more important in understanding the positive and negative effects on cognition in the large number of conditions for which it is now being used. However, this is clearly complicated by the fact that the stimulation itself will alter the function of neural networks directly, as has been seen in studies looking at cognitive function in patients in receipt of subthalamic DBS (Funkiewiez et al., 2006).

However, more recently, others have argued that the induction of a significant astrocytic response actually enhances any DBS-mediated effects (Fenoy et al., 2014). Fenoy et al. suggest that the inevitable stimulation of astrocytes by DBS can set in motion the release of gliotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, adenosine, and D-serine) that can in turn trigger axonal activation which mediates part of the therapeutic benefits of the stimulation. For example, application of adenosine A1-receptor antagonists abolishes HFS-induced suppression of thalamic neuronal activity. More specifically, adenosine, which results from the conversion of ATP by astrocytes, significantly increases in the electrodes' surroundings, endorsing its role in stimulation-mediated effects on tremor (Bekar et al., 2008). In support of this, the release of glutamate and adenosine both terminate oscillations generated by HFS in thalamic sites (Tawfik et al., 2010).

Astrocytes, which have the capacity to interact with up to 2 million synapses in the human brain, can have a profound effect on synaptic activity as well as other astrocytes across large neural networks (Oberheim et al., 2006). The contact that astrocytes have with blood vessels also uniquely enables them to regulate local blood flow in response to increased neuronal activity, which again may help explain the beneficial effects of DBS (Takano et al., 2006). Using in vivo two-photon imaging and photolysis, the authors elegantly demonstrated the association between increases in Ca2+ levels in astrocytic end feet with vasodilation, a process which more specifically involves COX-1 metabolites. Finally, DBS can also promote the proliferation of “neurogenic astrocytes” which can differentiate into functional neurons (Vedam-Mai et al., 2012a) (Figure 1). Taken together, this data suggests a prominent role for astrocytes in DBS-mediated effects implying that there may be an optimal balance in the astrocytic response, in terms of positive and negative effects on the stimulated neural pathways, which may in part be responsible for determining the clinical success of this treatment.

In summary, DBS electrodes will induce an astrocytic and microglial response (Figure 1.1) although the extent to which this adversely affects their efficacy in patients is unproven. Indeed, recent data may even suggest the opposite (Moro et al., 2010). However, the data is limited and there is therefore a need to collect systemically more information in this area and moves are afoot to do this (Vedam-Mai et al., 2011), with the expectation that this will enable us to better understand this hitherto poorly described effect of DBS (Vedam-Mai et al., 2011).

Neurotrophic Therapies and the Glial Response

Gene Therapy

There are a number of gene therapy trials that have been undertaken in PD which seek to either improve the delivery of dopaminergic stimulation to the striatum; restore to normal the abnormal circuitry of the basal ganglia or promote host repair through rescuing dopaminergic neurons and their striatal innervation (reviewed in Berry and Foltynie, 2011). Other gene therapy trials have targeted HD (Bloch et al., 2004) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Mandel, 2010). In this last respect, Nerve growth Factor (NGF) transfected fibroblasts were used and one patient died shortly after receiving the therapy for unrelated reasons. At post-mortem, the brain showed surviving cells and NGF expression, and although the glial response to the therapy was not explicitly studied, they did comment there was a minimal inflammatory and glial response, as evidenced by the fact that they found a few granulomatous cells only (Tuszynski et al., 2005).

In the PD studies, again only a few patients have come to post-mortem, so any data as to the host response to these virally delivered agents is very limited and most have concentrated on the extent of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) fiber sprouting and the volume of distribution of the therapeutic agent, as well as systemic toxicity and local inflammation (e.g., Herzog et al., 2008, 2009; Bartus et al., 2011). However, there are studies showing that these agents may have a primary effect on the astrocytic compartment and that this is the route by which they actually rescue neurons. For example, Hauck et al. (2006) showed that GDNF works indirectly on photoreceptors to rescue them via Mueller glial cells, and so unlike other invasive therapies, part of their efficacy may actually be enhanced through the host glial compartment.

Overall, evidence to date would suggest that the viral delivery of neuroactive substances to the CNS induces very little glial and inflammatory cell responses, including AAV2-Neurturin (Jeff Kordower; Personal Commun.) (Figure 1.2) as well as pre-clinical reports pertaining to this field (Table 2).

Direct Neurotrophic Factor Infusion

The direct infusion of GDNF into the brain of patients with PD has been the subject of a number of trials. This was initially undertaken using an intraventricular delivery approach that proved ineffective (Nutt et al., 2003), almost certainly because the agent failed to reach the dopaminergic neurons and their projections. This would be consistent with the single post-mortem case from this study showing no evidence of regeneration within the affected nigrostriatal pathway (Kordower et al., 1999). This was then followed by a number of studies in which GDNF was directly infused into the brain parenchyma with variable efficacy—the open label studies showed benefits whilst a double blind placebo controlled study showed no such effects (Gill et al., 2003; Patel et al., 2005; Slevin et al., 2005, 2007; Lang et al., 2006). Although there are various reasons as to why this may have occurred (Barker, 2006), it is of interest to know whether the infusion provoked a glial reaction. This is important not only to see the extent to which chronically implanted catheters delivering neuroactive agents induce a glial response but, given that astrocytes themselves can actually release neurotrophic factors (e.g., Iravani et al., 2012), it is also critical to know whether they may also be capable of enhancing any regenerative response.

In the single post-mortem case looking at intra-parenchymal GDNF delivery in a patient with PD, there was evidence of host TH fiber sprouting around the catheter tip with a low grade astrocytic, microglial and T-cell response (Love et al., 2005). This patient showed a 38% improvement in their contralateral UPDRS (Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale) “off” motor score with a 91% increase in Fluoro-dopa signal in the infused posterior putamen. He died of a myocardial infarction, 3 months after stopping the GDNF therapy that he had been receiving for 43 months. Neuropathologically, there was a slight astrogliosis around the catheter track and tip with a few MHC class II expressing microglia and where this was most intense, there was a reduction in the synaptic protein, synaptophysin. Overall, the glial response to the chronic infusion of GDNF was localized.

Neural Grafting and the Glial Response

The experimental approach of cell transplantation is one in which the glial response has been more specifically addressed. Two distinct types of cell transplantation have been tested in the clinic—cell suspensions, prepared by mechanically dissociating the cells prior to implantation (Lindvall et al., 1990; Mendez et al., 2002; Freeman and Brundin, 2006) and solid grafts, where donor tissue is transplanted as small pieces (Freeman et al., 1995, 2000; Kordower et al., 1997; Olanow et al., 2003; Freeman and Brundin, 2006; Cicchetti et al., 2009). Each of these strategies is associated with a different pattern and intensity of gliosis. In addition, different cell types may induce different host responses, depending on their source of origin, preparation, and mode of implantation (see Table 3).

In PD, various post-mortem analyses conducted in transplanted patients have shown that solid grafts evoke a more robust and durable immune response in comparison to cell suspensions (Kordower et al., 1997; Olanow et al., 2003; Mendez et al., 2005, 2008; Freeman and Brundin, 2006; Cooper et al., 2009), a finding which is further supported by observations collected in grafted animal models of the disease (Leigh et al., 1994; see also Table 3). Few microglial cells are observed around the needle track with only a mild response around the graft deposits themselves. Similarly, the astrocytic response, which accompanies cell suspension grafts, is predominantly confined to the borders of the graft, with the core of the transplant largely devoid of this cell type (Figure 1.3).

Histological analyses in HD patients transplanted with solid embryonic neural grafts show microglial activation, particularly around the transplant and within the grafted areas expressing striatal markers (referred to as p-zones). Importantly, this significant microglial cuffing is still present 12 years following transplantation (Cicchetti et al., 2009). As observed in cell suspension grafts, solid piece transplants induce little astrogliosis although a number of cells of a reactive phenotype are found around the grafted tissue (Cisbani et al., 2013) (Figure 1.3). This pattern of astroglial activation and distribution may have important implications for the survival of the grafts long-term, as astrocytes play not only a critical role in growth factor release but also in glutamate buffering, and thus excitotoxicity (Cicchetti et al., 2011).

Comparing the post-mortem analysis of HD and PD allografted tissue, irrespective of the type of graft implanted, there appears to be a distinctly different glial reaction. In HD, there seems to be a much more aggressive glial (both in terms of the number of activated cells and their phenotype) response whilst in PD, the evidence would suggest that the microglial response is much less obvious. Therefore, transplantation in different diseases may produce different glial responses which in turn may influence the long term survival, integration and outcome of the grafted issue (Cicchetti et al., 2011, 2014).

Furthermore, we have recently shown the presence of mutant huntingtin protein aggregates within genetically unrelated grafted tissue in HD patients. This observation, which is similar to that reported earlier with the discovery of lewy bodies in grafted fetal ventral mesencephalon tissue in PD patients, could also result, at least in part, from oxidative stress and the host inflammatory response induced by the graft (Li et al., 2008; Cicchetti et al., 2014).

Taken together, it is possible that the host response to solid grafts in the absence of immunosuppression (which was restricted to the first 6 months following transplantation in those HD post-mortem cases described above) generates enhanced antigenic stimulation and a stronger immunological/inflammatory response than with suspension grafts (Kordower et al., 1997; Olanow et al., 2003; Mendez et al., 2005, 2008; Freeman and Brundin, 2006; Redmond et al., 2008). Indeed, the type and duration of immunosuppressive treatment is likely to contribute to some of the discrepancies in the immune/glial responses observed using these different transplants. Nevertheless, the accumulating evidence of an attenuated glial response following transplantation of cell suspension grafts favors their use in future clinical cell transplant programs in patients with neurodegenerative disorders (Freeman and Brundin, 2006).

Conclusion

There are now a number of new therapies emerging for the treatment of chronic neurodegenerative disorders of the CNS which are invasive but seek to restore to normal the dysfunctional circuits that underlie these conditions. These approaches have generally used a targeted intracerebral delivery of a neuroactive substance or therapeutic device. To date, these therapies have produced mixed results and many explanations to account for this have been put forward including patient selection, disease stage and subtype, mode of delivery, dose given, trial design, and the nature and timing for the primary end-points. However, another area that requires further investigation is the glial and inflammatory response to the novel therapeutic agent as this may impact on its efficacy. To date there are very few studies looking at this and in this review we have sought to highlight this with reference to the limited literature on the microglial and astrocytic reactions to these therapies. At the present time, such responses seem likely to be less of an issue with growth factor infusions and gene therapies—although this may simply reflect the limited post-mortem analyses on this to date—but may be highly relevant for the short and long term viability of neural transplants as well as DBS efficacy, and to a greater magnitude than originally thought. The only way such information can meaningfully be obtained is through the detailed analyses of the post-mortem cases that can be made available by such trials and which will allow us to understand which cells are affected and to what extent. Indeed, one of the critical questions will be the extent to which each cell type influences the behavior of another, as it is now clear that there is a dialog between the glial cells, neurons, and vasculature (Figure 1.4). An improved understanding of these interactions may ultimately impact on our ability to better treat patients using these novel approaches as well as modifications as to how they are can be optimally delivered.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Francesca Cicchetti is largely funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and is a recipient of a National Researcher career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec en santé (FRSQ) providing salary support and operating funds. Roger A. Barker receives support for his work from a number of sources but especially the NIHR Biomedical research Centre Award to the Addenbrooke's Hospital and University of Cambridge. The authors would like to thank Mr. Gilles Chabot for artwork, Dr. Daniel Skuk for assistance with literature review and Miss. Martine Saint-Pierre for assistance with manuscript handling.

References

Baba, T., Kameda, M., Yasuhara, T., Morimoto, T., Kondo, A., Shingo, T., et al. (2009). Electrical stimulation of the cerebral cortex exerts antiapoptotic, angiogenic, and anti-inflammatory effects in ischemic stroke rats through phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Stroke 40, e598–e605. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.563627

Barker, R. A. (2006). Continuing trials of GDNF in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 5, 285–286. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70386-6

Barker, R. A., Dunnett, S. B., Faissner, A., and Fawcett, J. W. (1996). The time course of loss of dopaminergic neurons and the gliotic reaction surrounding grafts of embryonic mesencephalon to the striatum. Exp. Neurol. 141, 79–93. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0141

Bartus, R. T., Herzog, C. D., Chu, Y., Wilson, A., Brown, L., Siffert, J., et al. (2011). Bioactivity of AAV2-neurturin gene therapy (CERE-120): differences between Parkinson's disease and nonhuman primate brains. Mov. Disord. 26, 27–36. doi: 10.1002/mds.23442

Bekar, L., Libionka, W., Tian, G. F., Xu, Q., Torres, A., Wang, X., et al. (2008). Adenosine is crucial for deep brain stimulation-mediated attenuation of tremor. Nat. Med. 14, 75–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1693

Berry, A. L., and Foltynie, T. (2011). Gene therapy: a viable therapeutic strategy for Parkinson's disease? J. Neurol. 258, 179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5796-9

Biran, R., Martin, D. C., and Tresco, P. A. (2005). Neuronal cell loss accompanies the brain tissue response to chronically implanted silicon microelectrode arrays. Exp. Neurol. 195, 115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.020

Biran, R., Martin, D. C., and Tresco, P. A. (2007). The brain tissue response to implanted silicon microelectrode arrays is increased when the device is tethered to the skull. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 82, 169–178. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31138

Bloch, J., Bachoud-Levi, A. C., Deglon, N., Lefaucheur, J. P., Winkel, L., Palfi, S., et al. (2004). Neuroprotective gene therapy for Huntington's disease, using polymer-encapsulated cells engineered to secrete human ciliary neurotrophic factor: results of a phase I study. Hum. Gene Ther. 15, 968–975. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.968

Cicchetti, F., Lacroix, S., Cisbani, G., Vallieres, N., Saint-Pierre, M., St-Amour, I., et al. (2014). Mutant huntingtin is present in neuronal grafts in Huntington's disease patients. Ann Neurol. doi: 10.1002/ana.24174. [Epub ahead of print].

Cicchetti, F., Saporta, S., Hauser, R. A., Parent, M., Saint-Pierre, M., Sanberg, P. R., et al. (2009). Neural transplants in patients with Huntington's disease undergo disease-like neuronal degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12483–12488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904239106

Cicchetti, F., Soulet, D., and Freeman, T. B. (2011). Neuronal degeneration in striatal transplants and Huntington's disease: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Brain 134, 641–652. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq328

Cisbani, G., Freeman, T. B., Soulet, D., Saint-Pierre, M., Gagnon, D., Parent, M., et al. (2013). Striatal allografts in patients with Huntington's disease: impact of diminished astrocytes and vascularization on graft viability. Brain 136, 433–443. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws359

Cooper, O., Astradsson, A., Hallett, P., Robertson, H., Mendez, I., and Isacson, O. (2009). Lack of functional relevance of isolated cell damage in transplants of Parkinson's disease patients. J. Neurol. 256(Suppl. 3), 310–316. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5242-z

Coyne, T. M., Marcus, A. J., Woodbury, D., and Black, I. B. (2006). Marrow stromal cells transplanted to the adult brain are rejected by an inflammatory response and transfer donor labels to host neurons and glia. Stem Cells 24, 2483–2492. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0174

De Vocht, N., Lin, D., Praet, J., Hoornaert, C., Reekmans, K., Le Blon, D., et al. (2013). Quantitative and phenotypic analysis of mesenchymal stromal cell graft survival and recognition by microglia and astrocytes in mouse brain. Immunobiology 218, 696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.08.266

Driesse, M. J., Vincent, A. J., Sillevis Smitt, P. A., Kros, J. M., Hoogerbrugge, P. M., Avezaat, C. J., et al. (1998). Intracerebral injection of adenovirus harboring the HSVtk gene combined with ganciclovir administration: toxicity study in nonhuman primates. Gene Ther. 5, 1122–1129. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300695

Duan, W. M., Widner, H., and Brundin, P. (1995). Temporal pattern of host responses against intrastriatal grafts of syngeneic, allogeneic or xenogeneic embryonic neuronal tissue in rats. Exp. Brain Res. 104, 227–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00242009

Dunnett, S. B., Carter, R. J., Watts, C., Torres, E. M., Mahal, A., Mangiarini, L., et al. (1998). Striatal transplantation in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Exp. Neurol. 154, 31–40. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6926

Ereifej, E. S., Khan, S., Newaz, G., Zhang, J., Auner, G. W., and VandeVord, P. J. (2011). Characterization of astrocyte reactivity and gene expression on biomaterials for neural electrodes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 99, 141–150. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33170

Fenoy, A. J., Goetz, L., Chabardes, S., and Xia, Y. (2014). Deep brain stimulation: are astrocytes a key driver behind the scene? CNS Neurosci. Ther. 20, 191–201. doi: 10.1111/cns.12223

Frampton, J. P., Hynd, M. R., Shuler, M. L., and Shain, W. (2010). Effects of glial cells on electrode impedance recorded from neuralprosthetic devices in vitro. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 1031–1047. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9911-y

Freeman, T. B., and Brundin, P. (2006). Important Aspects of Surgical Methodology for Transplantation in Parkinson's disease. London: Springer.

Freeman, T. B., Cicchetti, F., Hauser, R. A., Deacon, T. W., Li, X. J., Hersch, S. M., et al. (2000). Transplanted fetal striatum in Huntington's disease: phenotypic development and lack of pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13877–13882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13877

Freeman, T. B., Olanow, C. W., Hauser, R. A., Nauert, G. M., Smith, D. A., Borlongan, C. V., et al. (1995). Bilateral fetal nigral transplantation into the postcommissural putamen in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 38, 379–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380307

Funkiewiez, A., Ardouin, C., Cools, R., Krack, P., Fraix, V., Batir, A., et al. (2006). Effects of levodopa and subthalamic nucleus stimulation on cognitive and affective functioning in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 21, 1656–1662. doi: 10.1002/mds.21029

Gill, S. S., Patel, N. K., Hotton, G. R., O'Sullivan, K., McCarter, R., Bunnage, M., et al. (2003). Direct brain infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson disease. Nat. Med. 9, 589–595. doi: 10.1038/nm850

Griffith, R. W., and Humphrey, D. R. (2006). Long-term gliosis around chronically implanted platinum electrodes in the Rhesus macaque motor cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 406, 81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.018

Groothuis, J., Ramsey, N. F., Ramakers, G. M., and van der Plasse, G. (2014). Physiological challenges for intracortical electrodes. Brain Stimul. 7, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.07.001

Hadaczek, P., Eberling, J. L., Pivirotto, P., Bringas, J., Forsayeth, J., and Bankiewicz, K. S. (2010). Eight years of clinical improvement in MPTP-lesioned primates after gene therapy with AAV2-hAADC. Mol. Ther. 18, 1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.106

Han, M., Manoonkitiwongsa, P. S., Wang, C. X., and McCreery, D. B. (2012). In vivo validation of custom-designed silicon-based microelectrode arrays for long-term neural recording and stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59, 346–354. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2172440

Harnack, D., Meissner, W., Paulat, R., Hilgenfeld, H., Muller, W. D., Winter, C., et al. (2008). Continuous high-frequency stimulation in freely moving rats: development of an implantable microstimulation system. J. Neurosci. Methods 167, 278–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.019

Harnack, D., Winter, C., Meissner, W., Reum, T., Kupsch, A., and Morgenstern, R. (2004). The effects of electrode material, charge density and stimulation duration on the safety of high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in rats. J. Neurosci. Methods 138, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.04.019

Hauck, S. M., Kinkl, N., Deeg, C. A., Swiatek-de Lange, M., Schoffmann, S., and Ueffing, M. (2006). GDNF family ligands trigger indirect neuroprotective signaling in retinal glial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2746–2757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2746-2757.2006

Helm, G. A., Palmer, P. E., Simmons, N. E., diPierro, C. G., and Bennett, J. P. Jr. (1993). Degeneration of long-term fetal neostriatal allografts in the rhesus monkey: an electron microscopic study. Exp. Neurol. 123, 174–180. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1150

Herzog, C. D., Brown, L., Gammon, D., Kruegel, B., Lin, R., Wilson, A., et al. (2009). Expression, bioactivity, and safety 1 year after adeno-associated viral vector type 2-mediated delivery of neurturin to the monkey nigrostriatal system support cere-120 for Parkinson's disease. Neurosurgery 64, 602–612; discussion 612–603. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000340682.06068.01

Herzog, C. D., Dass, B., Gasmi, M., Bakay, R., Stansell, J. E., Tuszynski, M., et al. (2008). Transgene expression, bioactivity, and safety of CERE-120 (AAV2-neurturin) following delivery to the monkey striatum. Mol. Ther. 16, 1737–1744. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.170

Hirshler, Y. K., Polat, U., and Biegon, A. (2010). Intracranial electrode implantation produces regional neuroinflammation and memory deficits in rats. Exp. Neurol. 222, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.006

Iravani, M. M., Sadeghian, M., Leung, C. C., Jenner, P., and Rose, S. (2012). Lipopolysaccharide-induced nigral inflammation leads to increased IL-1β tissue content and expression of astrocytic glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Neurosci. Lett. 510, 138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.022

Jarraya, B., Bonnet, A. M., Duyckaerts, C., Houeto, J. L., Cornu, P., Hauw, J. J., et al. (2003). Parkinson's disease, subthalamic stimulation, and selection of candidates: a pathological study. Mov. Disord. 18, 1517–1520. doi: 10.1002/mds.10607

Jiang, Q., Li, S. Y., Liu, Z. G., Liu, J., Chen, S. D., Zheng, Z. C., et al. (1999). Preliminary study on gene therapy of PD monkey using microcapsulated rat transgenetic myoblasts. Sheng Wu Hua Xue Yu Sheng Wu Wu Li Xue Bao (Shanghai) 31, 155–158.

Khoo, M. L., Tao, H., Meedeniya, A. C., Mackay-Sim, A., and Ma, D. D. (2011). Transplantation of neuronal-primed human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in hemiparkinsonian rodents. PLoS ONE 6:e19025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019025

Kim, D. H., and Martin, D. C. (2006). Sustained release of dexamethasone from hydrophilic matrices using PLGA nanoparticles for neural drug delivery. Biomaterials 15, 3031–3037. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.021

Kim, Y. T., Hitchcock, R. W., Bridge, M. J., and Tresco, P. A. (2004). Chronic response of adult rat brain tissue to implants anchored to the skull. Biomaterials 25, 2229–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.010

Kordower, J. H., Palfi, S., Chen, E. Y., Ma, S. Y., Sendera, T., Cochran, E. J., et al. (1999). Clinicopathological findings following intraventricular glial-derived neurotrophic factor treatment in a patient with Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 46, 419–424.

Kordower, J. H., Styren, S., Clarke, M., DeKosky, S. T., Olanow, C. W., and Freeman, T. B. (1997). Fetal grafting for Parkinson's disease: expression of immune markers in two patients with functional fetal nigral implants. Cell Transplant. 6, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/S0963-6897(97)00019-5

Kosno-Kruszewska, E., Wierzba-Bobrowicz, T., Ilnicki, K., Lechowicz, W., and Dymecki, J. (1996). Evaluation of survival and maturation of cryopreserved dopaminergic fetal cells transplanted into rat striatum and an analysis of the host brain reaction to graft. Folia Neuropathol. 34, 1–6.

Lang, A. E., Gill, S., Patel, N. K., Lozano, A., Nutt, J. G., Penn, R., et al. (2006). Randomized controlled trial of intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor infusion in Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 59, 459–466. doi: 10.1002/ana.20737

Lattanzi, A., Neri, M., Maderna, C., di Girolamo, I., Martino, S., Orlacchio, A., et al. (2010). Widespread enzymatic correction of CNS tissues by a single intracerebral injection of therapeutic lentiviral vector in leukodystrophy mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2208–2227. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq099

Leigh, K., Elisevich, K., and Rogers, K. A. (1994). Vascularization and microvascular permeability in solid versus cell-suspension embryonic neural grafts. J. Neurosurg. 81, 272–283. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0272

Lenarz, M., Lim, H. H., Lenarz, T., Reich, U., Marquardt, N., Klingberg, M. N., et al. (2007). Auditory midbrain implant: histomorphologic effects of long-term implantation and electric stimulation of a new deep brain stimulation array. Otol. Neurotol. 28, 1045–1052. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318159e74f

Leung, B. K., Biran, R., Underwood, C. J., and Tresco, P. A. (2008). Characterization of microglial attachment and cytokine release on biomaterials of differing surface chemistry. Biomaterials 29, 3289–3297. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.045

Li, J. Y., Englund, E., Holton, J. L., Soulet, D., Hagell, P., Lees, A. J., et al. (2008). Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson's disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat. Med. 14, 501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746

Lindvall, O., Brundin, P., Widner, H., Rehncrona, S., Gustavii, B., Frackowiak, R., et al. (1990). Grafts of fetal dopamine neurons survive and improve motor function in Parkinson's disease. Science 247, 574–577. doi: 10.1126/science.2105529

Louboutin, J. P., Marusich, E., Fisher-Perkins, J., Dufour, J. P., Bunnell, B. A., and Strayer, D. S. (2011). Gene transfer to the rhesus monkey brain using SV40-derived vectors is durable and safe. Gene Ther. 18, 682–691. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.13

Louboutin, J. P., Reyes, B. A., Agrawal, L., Van Bockstaele, E., and Strayer, D. S. (2007). Strategies for CNS-directed gene delivery: in vivo gene transfer to the brain using SV40-derived vectors. Gene Ther. 14, 939–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302939

Love, S., Plaha, P., Patel, N. K., Hotton, G. R., Brooks, D. J., and Gill, S. S. (2005). Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor induces neuronal sprouting in human brain. Nat. Med. 11, 703–704. doi: 10.1038/nm0705-703

Lyons, M. K. (2011). Deep brain stimulation: current and future clinical applications. Mayo Clin. Proc. 86, 662–672. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0045

Ma, T., Gong, K., Ao, Q., Yan, Y., Song, B., Huang, H., et al. (2013). Intracerebral transplantation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alternatively activates microglia and ameliorates neuropathological deficits in Alzheimer's disease mice. Cell Transplant. 22(Suppl. 1), S113–S126. doi: 10.3727/096368913X672181

Mandel, R. J. (2010). CERE-110, an adeno-associated virus-based gene delivery vector expressing human nerve growth factor for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 12, 240–247.

McConnell, G. C., Rees, H. D., Levey, A. I., Gutekunst, C. A., Gross, R. E., and Bellamkonda, R. V. (2009). Implanted neural electrodes cause chronic, local inflammation that is correlated with local neurodegeneration. J. Neural Eng. 6:056003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/056003

Mendez, I., Dagher, A., Hong, M., Gaudet, P., Weerasinghe, S., McAlister, V., et al. (2002). Simultaneous intrastriatal and intranigral fetal dopaminergic grafts in patients with Parkinson disease: a pilot study. Report of three cases. J. Neurosurg. 96, 589–596. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.3.0589

Mendez, I., Sanchez-Pernaute, R., Cooper, O., Vinuela, A., Ferrari, D., Bjorklund, L., et al. (2005). Cell type analysis of functional fetal dopamine cell suspension transplants in the striatum and substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain 128, 1498–1510. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh510

Mendez, I., Vinuela, A., Astradsson, A., Mukhida, K., Hallett, P., Robertson, H., et al. (2008). Dopamine neurons implanted into people with Parkinson's disease survive without pathology for 14 years. Nat. Med. 14, 507–509. doi: 10.1038/nm1752

Mercanzini, A., Reddy, S. T., Velluto, D., Colin, P., Maillard, A., Bensadoun, J. C., et al. (2010). Controlled release nanoparticle-embedded coatings reduce the tissue reaction to neuroprostheses. J. Control. Release 145, 196–202. doi: 10.1016/jconrel.2010.04.025

Morimoto, T., Yasuhara, T., Kameda, M., Baba, T., Kuramoto, S., Kondo, A., et al. (2011). Striatal stimulation nurtures endogenous neurogenesis and angiogenesis in chronic-phase ischemic stroke rats. Cell Transplant. 20, 1049–1064. doi: 10.3727/096368910X544915

Moro, E., Lozano, A. M., Pollak, P., Agid, Y., Rehncrona, S., Volkmann, J., et al. (2010). Long-term results of a multicenter study on subthalamic and pallidal stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 25, 578–586. doi: 10.1002/mds.22735

Mosher, K. I., Andres, R. H., Fukuhara, T., Bieri, G., Hasegawa-Moriyama, M., He, Y., et al. (2012). Neural progenitor cells regulate microglia functions and activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1485–1487. doi: 10.1038/nn.3233

Moss, J., Ryder, T., Aziz, T. Z., Graeber, M. B., and Bain, P. G. (2004). Electron microscopy of tissue adherent to explanted electrodes in dystonia and Parkinson's disease. Brain 127, 2755–2763. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh292

Muraoka, K., Shingo, T., Yasuhara, T., Kameda, M., Yuan, W., Hayase, H., et al. (2006). The high integration and differentiation potential of autologous neural stem cell transplantation compared with allogeneic transplantation in adult rat hippocampus. Exp. Neurol. 199, 311–327. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.004

Nutt, J. G., Burchiel, K. J., Comella, C. L., Jankovic, J., Lang, A. E., Laws, E. R., et al. (2003). Randomized, double-blind trial of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in PD. Neurology 60, 69–73. doi: 10.1212/WNL.60.1.69

Oberheim, N. A., Wang, X., Goldman, S., and Nedergaard, M. (2006). Astrocytic complexity distinguishes the human brain. Trends Neurosci. 29, 547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.004

Olanow, C. W., Goetz, C. G., Kordower, J. H., Stoessl, A. J., Sossi, V., Brin, M. F., et al. (2003). A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 54, 403–414. doi: 10.1002/ana.10720

Osman, A. M., Zhou, K., Zhu, C., and Blomgren, K. (2013). Transplantation of enteric neural stem/progenitor cells into the irradiated young mouse hippocampus. Cell Transplant. doi: 10.3727/096368913X674648. [Epub ahead of print].

Patel, N. K., Bunnage, M., Plaha, P., Svendsen, C. N., Heywood, P., and Gill, S. S. (2005). Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in PD: a two-year outcome study. Ann. Neurol. 57, 298–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.20374

Pennell, N. A., and Streit, W. J. (1997). Colonization of neural allografts by host microglial cells: relationship to graft neovascularization. Cell Transplant. 6, 221–230. doi: 10.1016/S0963-6897(97)00030-4

Polikov, V. S., Su, E. C., Ball, M. A., Hong, J. S., and Reichert, W. M. (2009). Control protocol for robust in vitro glial scar formation around microwires: essential roles of bFGF and serum in gliosis. J. Neurosci. Methods 181, 170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.05.002

Praet, J., Reekmans, K., Lin, D., De Vocht, N., Bergwerf, I., Tambuyzer, B., et al. (2012). Cell type-associated differences in migration, survival, and immunogenicity following grafting in CNS tissue. Cell Transplant. 21, 1867–1881. doi: 10.3727/096368912X636920

Rahim, A. A., Wong, A. M., Ahmadi, S., Hoefer, K., Buckley, S. M., Hughes, D. A., et al. (2012). In utero administration of Ad5 and AAV pseudotypes to the fetal brain leads to efficient, widespread and long-term gene expression. Gene Ther. 19, 936–946. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.157

Rahim, A. A., Wong, A. M., Hoefer, K., Buckley, S. M., Mattar, C. N., Cheng, S. H., et al. (2011). Intravenous administration of AAV2/9 to the fetal and neonatal mouse leads to differential targeting of CNS cell types and extensive transduction of the nervous system. FASEB J. 25, 3505–3518. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-182311

Redmond, D. E. Jr., Vinuela, A., Kordower, J. H., and Isacson, O. (2008). Influence of cell preparation and target location on the behavioral recovery after striatal transplantation of fetal dopaminergic neurons in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 29, 103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.08.008

Rennaker, R. L., Miller, J., Tang, H., and Wilson, D. A. (2007). Minocycline increases quality and longevity of chronic neural recordings. J. Neural Eng. 4, L1–L5. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/2/L01

Slevin, J. T., Gash, D. M., Smith, C. D., Gerhardt, G. A., Kryscio, R., Chebrolu, H., et al. (2007). Unilateral intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with Parkinson disease: response to 1 year of treatment and 1 year of withdrawal. J. Neurosurg. 106, 614–620. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.4.614

Slevin, J. T., Gerhardt, G. A., Smith, C. D., Gash, D. M., Kryscio, R., and Young, B. (2005). Improvement of bilateral motor functions in patients with Parkinson disease through the unilateral intraputaminal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurosurg. 102, 216–222. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0216

Snyder-Keller, A., McLear, J. A., Hathorn, T., and Messer, A. (2010). Early or late-stage anti-N-terminal Huntingtin intrabody gene therapy reduces pathological features in B6.HDR6/1 mice. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 69, 1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181f530ec

Spataro, L., Dilgen, J., Retterer, S., Spence, A. J., Isaacson, M., Turner, J. N., et al. (2005). Dexamethasone treatment reduces astroglia responses to inserted neuroprosthetic devices in rat neocortex. Exp. Neurol. 194, 289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.037

Stefani, A., Pierantozzi, M., Ceravolo, R., Brusa, L., Galati, S., and Stanzione, P. (2010). Deep brain stimulation of pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg) promotes cognitive and metabolic changes: a target-specific effect or response to a low-frequency pattern of stimulation? Clin. EEG Neurosci. 41, 82–86. doi: 10.1177/155005941004100207

Stice, P., Gilletti, A., Panitch, A., and Muthuswamy, J. (2007). Thin microelectrodes reduce GFAP expression in the implant site in rodent somatosensory cortex. J. Neural Eng. 4, 42–53. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/2/005

Szarowski, D. H., Andersen, M. D., Retterer, S., Spence, A. J., Isaacson, M., Craighead, H. G., et al. (2003). Brain responses to micro-machined silicon devices. Brain Res. 983, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)03023-3

Takano, T., Tian, G. F., Peng, W., Lou, N., Libionka, W., Han, X., et al. (2006). Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623

Tawfik, V. L., Chang, S. Y., Hitti, F. L., Roberts, D. W., Leiter, J. C., Jovanovic, S., et al. (2010). Deep brain stimulation results in local glutamate and adenosine release: investigation into the role of astrocytes. Neurosurgery 67, 367–375. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000371988.73620.4C

Toupet, K., Compan, V., Crozet, C., Mourton-Gilles, C., Mestre-Frances, N., Ibos, F., et al. (2008). Effective gene therapy in a mouse model of prion diseases. PLoS ONE 3:e2773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002773

Tripathy, D., Haobam, R., Nair, R., and Mohanakumar, K. P. (2013). Engraftment of mouse embryonic stem cells differentiated by default leads to neuroprotection, behaviour revival and astrogliosis in parkinsonian rats. PLoS ONE 8:e72501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072501

Tuszynski, M. H., Thal, L., Pay, M., Salmon, D. P., U, H. S., Bakay, R., et al. (2005). A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 11, 551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm1239

Vedam-Mai, V., Krock, N., Ullman, M., Foote, K. D., Shain, W., Smith, K., et al. (2011). The national DBS brain tissue network pilot study: need for more tissue and more standardization. Cell Tissue Bank. 12, 219–231. doi: 10.1007/s10561-010-9189-1

Vedam-Mai, V., van Battum, E. Y., Kamphuis, W., Feenstra, M. G., Denys, D., Reynolds, B. A., et al. (2012a). Deep brain stimulation and the role of astrocytes. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 124–131, 115. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.61

Vedam-Mai, V., Yachnis, A., Ullman, M., Javedan, S. P., and Okun, M. S. (2012b). Postmortem observation of collagenous lead tip region fibrosis as a rare complication of DBS. Mov. Disord. 27, 565–569. doi: 10.1002/mds.24916

Witt, K., Daniels, C., Reiff, J., Krack, P., Volkmann, J., Pinsker, M. O., et al. (2008). Neuropsychological and psychiatric changes after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 7, 605–614. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70114-5

Zhong, Y., and Bellamkonda, R. V. (2007). Dexamethasone-coated neural probes elicit attenuated inflammatory response and neuronal loss compared to uncoated neural probes. Brain Res. 1148, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.024

Keywords: gene therapy for neurodegenerative diseases, cell transplantation, deep brain stimulation, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, astrocytes, microglia

Citation: Cicchetti F and Barker RA (2014) The glial response to intracerebrally delivered therapies for neurodegenerative disorders: is this a critical issue? Front. Pharmacol. 5:139. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00139

Received: 28 March 2014; Accepted: 24 May 2014;

Published online: 10 July 2014.

Edited by:

Eero Vasar, University of Tartu, EstoniaReviewed by:

Bruno Pierre Guiard, University of Paris XI, FranceMaria-Grazia Martinoli, Université du Québec, Canada

Copyright © 2014 Cicchetti and Barker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesca Cicchetti, Axe Neurosciences, Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec, T2-50, 2705 Boulevard Laurier, Québec, QC G1V 4G2, Canada e-mail:ZnJhbmNlc2NhLmNpY2NoZXR0aUBjcmNodWwudWxhdmFsLmNh;

Roger A. Barker, John van Geest Centre for Brain Repair, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0PY, UK e-mail:cmFiNDZAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Francesca Cicchetti

Francesca Cicchetti Roger A. Barker

Roger A. Barker