94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol., 04 March 2014

Sec. Ethnopharmacology

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2014.00031

This article is part of the Research TopicHerbal Remedies and Phytochemicals: Focus on Safety and Toxicological EvaluationView all 5 articles

This review evaluates the safety of echinacea and elderberry in pregnancy. Both herbs are commonly used to prevent or treat upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and surveys have shown that they are also used by pregnant women. The electronic databases PubMed, ISI Web of Science, AMED, EMBASE, Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, and Cochrane Library were searched from inception to November 2013. Relevant references from the acquired articles were included. No clinical trials concerning safety of either herb in pregnancy were identified. One prospective human study and two small animal studies of safety of echinacea in pregnancy were identified. No animal- or human studies of safety of elderberry in pregnancy were identified. Twenty clinical trials concerning efficacy of various echinacea preparations in various groups of the population were identified between 1995 and 2013. Three clinical trials concerning efficacy of two different elderberry preparations were identified between 1995 and 2013. The results from the human and animal studies of Echinacea sp. are not sufficient to conclude on the safety in pregnancy. The prospective, controlled study in humans found no increase in risk of major malformations. The efficacy of Echinacea sp. is dubious based on the identified studies. Over 2000 persons were given the treatment, but equal amounts of studies of good quality found positive and negative results. All three clinical trials of Elderberry concluded that it is effective against influenza, but only 77 persons were given the treatment. Due to lack of evidence of efficacy and safety, health care personnel should not advice pregnant women to use echinacea or elderberry against upper respiratory tract infection.

This review considers two herbal treatments against upper respiratory tract infection (URTI); Echinacea sp. and Sambucus nigra and the safety of their use by pregnant women. Echinacea sp. are commonly used by pregnant women (Hepner et al., 2002; Nordeng and Havnen, 2004; Holst et al., 2009a; Heitmann et al., 2010), but documentation of safety in pregnancy is sparse. Sambucus nigra is used by pregnant women in Norway (Nordeng and Havnen, 2004) and the USA (Tsui et al., 2001) while no documentation of use in other regions is available to our knowledge. The use of herbal remedies among pregnant women in the western world is common though the documentation of safety and efficacy is lacking (Nordeng and Havnen, 2004; Forster et al., 2006; Lapi et al., 2008; Holst et al., 2009a; Cuzzolin et al., 2010; Facchinetti et al., 2012). Clinical trials of herbs are not common and for ethical reasons pregnant women are so far only included in trials of herbs against pregnancy-specific conditions like nausea and vomiting (NVP) (Pongrojpaw et al., 2007; Ensiyeh and Sakineh, 2008; Ozgoli et al., 2009). Still pregnant women use herbs against many other conditions (Nordeng and Havnen, 2004; Holst et al., 2009a; Heitmann et al., 2010).

Pharmaceuticals are generally not tested in pregnant women, but the drug substances are tested for their teratogenic potential in two animal species before they are approved for human use. Whether this gives a good prediction of teratogenic potential in humans, is controversial, but in many cases it gives an indication to be followed up by pharmacovigilance (Koren and Nordeng, 2013). New teratogenic effects are often first reported as case reports. These can be followed by observational studies of exposed pregnant women compared to healthy pregnant controls or disease matched women. Linking of various registries like a prescription registry with the medical birth registry can give us important information about teratogenicity of pharmaceuticals. Herbal remedies are not prescribed and their use is therefore not registered. Only the user has the information and if she is not asked by health care personnel in antenatal care or does not reveal her herb use, no link between herbs and pregnancy outcome can be made. In large observational studies like the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, 2007) the safety of commonly used herbs can be studied (Heitmann et al., 2013), but even studies like that of more than 100.000 pregnancies may be limited by study power if the frequency of herbal use is low as malformations rarely occur and most teratogens cause only a moderate rise in risk. Heitmann et al. (2013) found that their study had ≥80% statistical power to rule out a doubling or more of the risk of major malformations after consumption of ginger (n = 466 in the first trimester) during early pregnancy.

Herbs can pose various risks in pregnancy (Schaefer et al., 2007). Some herbs like black cohosh (Actaea racemosa L.) or blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides (L.) Michaux) have traditionally been used to stimulate menstruation or provoke abortion. Alkaloid-containing herbs like barberry (Berberis vulgaris L.) are potentially hepatotoxic, but many of them are used by medical herbalists to treat conditions like constipation or heartburn. Laxatives containing anthraquinones from for instance senna (Senna alexandrina Mill.) or cascara (Rhamnus purshiana DC.) are effective stimulants of the bowel peristalsis, but might theoretically also stimulate uterus. Some women might substitute necessary prescribed pharmaceuticals for herbs due to a belief in their safety and will thus not be treated properly for a serious condition. Others might use a herbal product before they become pregnant and just continue the use unconsciously. Some herbal products have been found to be contaminated with heavy metals or deliberately added pharmaceuticals and in some cases misidentified herbs have been included (Schaefer et al., 2007).

A benefit-risk evaluation is essential when a pregnant woman considers using a herbal product. The fact that there is no documentation of safety does not mean that there is a risk—it just means that we don't know. If the benefit is substantial, it might be reasonable to use the product in spite of the sparse safety documentation. This is commonly the case for pharmaceuticals. The use of for instance antiepileptic drugs is essential for the mother and although the drug may pose a risk for the fetus, the benefit in many cases is found to outweigh the risk. As the use of herbal products is hardly essential (at least in the western world) the risk should preferably be documented to be minute before a product is recommended.

Echinacea sp. used for treatment of URTI (mainly cold) are Echinacea purpurea, Echinacea pallida, and Echinacea angustifolia. Used plant parts are “herba” and “radix,” separately or combined. The remedies are manufactured by different extraction methods possibly leading to extraction of different constituents and/or different amounts of the constituents. The herbal remedies are sold as tablets, tincture, or tea. For those reasons it is difficult to compare herbal remedies containing Echinacea sp. The European Medicines Agency, EMA, has developed monographs for Echinacea purpurea herba and radix, Echinacea pallida radix and Echinacea angustifolia radix (European Medicines Agency, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012). In accordance with these legal texts none of the licensed herbal products containing Echinacea sp. should be used during pregnancy or lactation due to lack of sufficient data. The only exception is topical use of Echinacea purpurea herba on other areas than the breast, this because systemic absorption is not expected. The German commission E Monographs on the other hand state that no restrictions on use during pregnancy or lactation are known except from parenteral use of Echinacea purpurea root (Blumenthal et al., 2000), however no references to scientific papers are given.

Sambucus nigra berry is used for treatment of URTI, mainly the flu. The European Medicines Agency, EMA, has worked on a monograph for the berries, but has terminated the work in March 2013 due to lack of information on traditional use with a specified dosage for at least 30 years (including 15 years in the EU) (European Medicines Agency, 2013a,b). Due to lack of information they do not recommend use of the berries during pregnancy or lactation.

Importantly, many trademark products containing echinacea or elderberry will be defined as dietary supplements and thus not be legally bound to follow the recommendations in the official plant monographs.

The aim of this study was to review the literature on safety during pregnancy and efficacy against URTI of Echinacea sp. and Sambucus nigra to help health care personnel to make evidence based decisions about their recommendations and advice.

The electronic databases PubMed, ISI Web of Science, AMED, EMBASE, Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, and Cochrane Library were searched from inception to November 2013 and relevant references from the acquired articles were also included. The applied search words/terms were:

A. Safety/reproductive toxicology AND pregnant/pregnancy AND Echinacea/coneflower

B. Safety/reproductive toxicology AND pregnant/pregnancy AND Sambucus nigra/elderberry

C. Efficacy AND Echinacea/coneflower

D. Efficacy AND Sambucus nigra /elderberry

Echinacea sp. covers Echinacea purpurea, Echinacea pallida, and Echinacea angustifolia.

Acquired references were handled according to PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009). This states four steps:

(1) Identification: number of records identified through database searching and number of additional records identified through other sources

(2) Screening: number of records after duplicates removed leading to number of records screened again leading to number of records excluded and

(3) Eligibility: number of full text articles assessed for eligibility leading to number of full text articles excluded (with reason) and

(4) Included: number of studies included in the qualitative synthesis leading to number of studies included in the quantitative synthesis

This analysis was performed for the searches A–D separately.

Articles excluded:

• other languages than English and the Scandinavian languages

• multi-herbal products

• in vitro studies

• other diagnoses than cold/flu (with respect to efficacy)

• Articles more than 20 years old (from 2013)

• Articles reporting prevalence of drug use

• Reviews

• Conference abstracts, letters, notes, editorials

The quality of the studies was evaluated according to criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins and Green, 2011).

The studies revealed in the literature searches and the selection of studies for the review is illustrated in Figure 1.

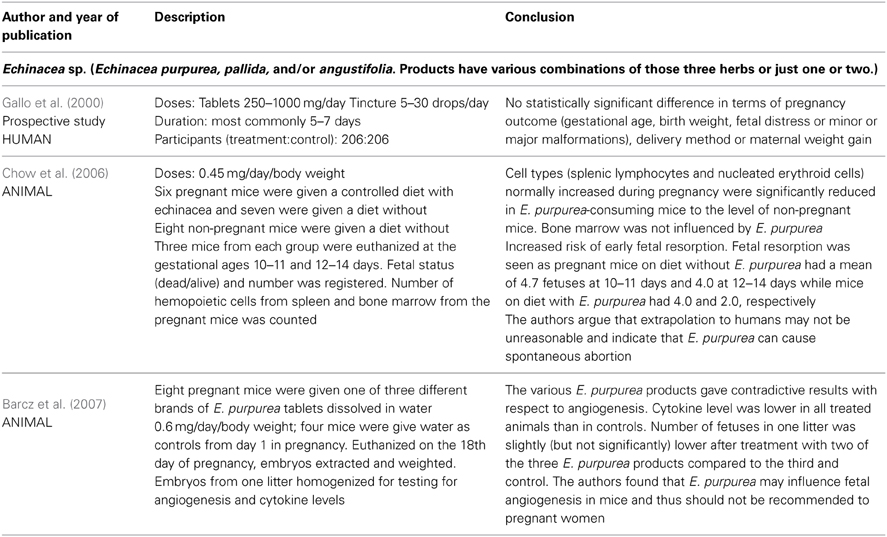

The only available human data on safety of echinacea in pregnancy come from one study of 412 pregnant women whereof 206 had used echinacea as tablets or tincture in various doses and with the most common duration being 5–7 days (Gallo et al., 2000). This cohort was disease-matched to women exposed to non-teratogenic agents by maternal age, alcohol intake and smoking, and rates of major and minor malformations were compared. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups with respect to pregnancy outcome, delivery method, maternal weight gain, gestational age, birth weight, fetal distress, or major malformations. See Table 1. No case reports describing side effects were located.

Table 1. Clinical trials and other human and animal studies of safety of Echinacea sp. in pregnancy.

Two animal studies on reproductivity are also available (Chow et al., 2006; Barcz et al., 2007). See Table 1.

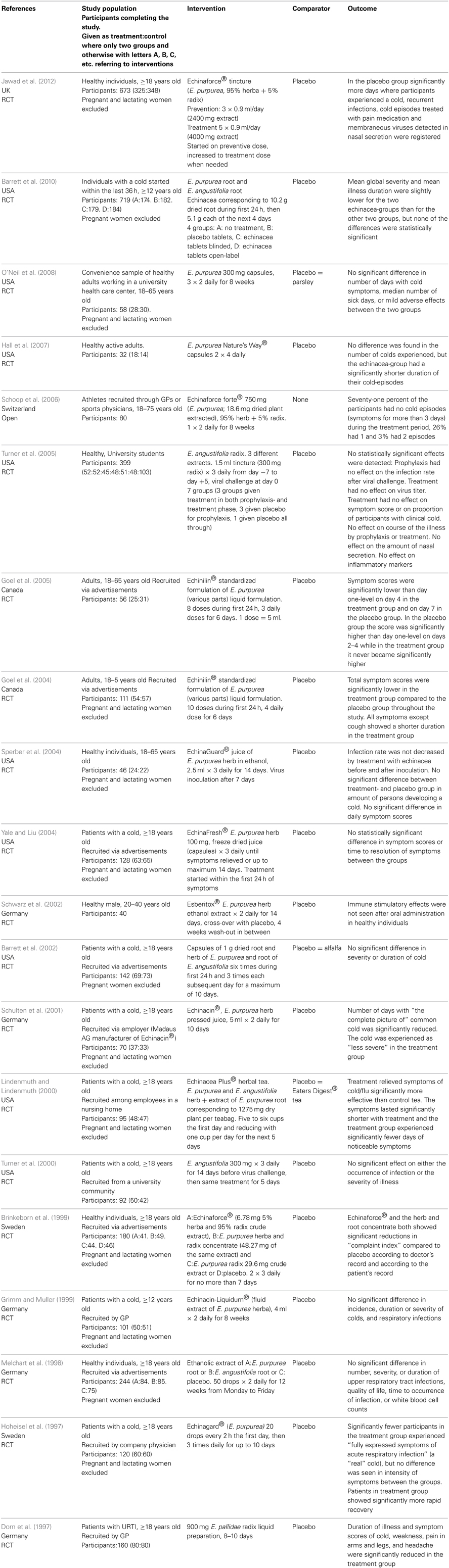

Twenty studies of the efficacy of Echinacea sp. against URTI were identified; see Table 2 (Dorn et al., 1997; Hoheisel et al., 1997; Melchart et al., 1998; Brinkeborn et al., 1999; Grimm and Muller, 1999; Lindenmuth and Lindenmuth, 2000; Turner et al., 2000; Schulten et al., 2001; Barrett et al., 2002, 2010; Schwarz et al., 2002; Goel et al., 2004, 2005; Sperber et al., 2004; Yale and Liu, 2004; Turner et al., 2005; Schoop et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2007; O'Neil et al., 2008; Jawad et al., 2012). Doses are difficult to compare as the formulations vary and are described in mg root/herb, mg extract or as “a standardized formulation.” One study included only men (Schwarz et al., 2002) and 12 studies specifically excluded pregnant women (Hoheisel et al., 1997; Melchart et al., 1998; Grimm and Muller, 1999; Lindenmuth and Lindenmuth, 2000; Schulten et al., 2001; Barrett et al., 2002, 2010; Goel et al., 2004; Sperber et al., 2004; Yale and Liu, 2004; O'Neil et al., 2008; Jawad et al., 2012). One study was open (Schoop et al., 2006), 19 were randomized, controlled trials (Dorn et al., 1997; Hoheisel et al., 1997; Melchart et al., 1998; Brinkeborn et al., 1999; Grimm and Muller, 1999; Lindenmuth and Lindenmuth, 2000; Turner et al., 2000, 2005; Schulten et al., 2001; Barrett et al., 2002, 2010; Schwarz et al., 2002; Goel et al., 2004, 2005; Sperber et al., 2004; Yale and Liu, 2004; Hall et al., 2007; O'Neil et al., 2008; Jawad et al., 2012). Twelve studies considered treatment of URTI (Dorn et al., 1997; Hoheisel et al., 1997; Brinkeborn et al., 1999; Lindenmuth and Lindenmuth, 2000; Schulten et al., 2001; Barrett et al., 2002, 2010; Goel et al., 2004, 2005; Sperber et al., 2004; Yale and Liu, 2004; O'Neil et al., 2008); one considered only prophylaxis (Schwarz et al., 2002) and seven considered both aspects (Melchart et al., 1998; Grimm and Muller, 1999; Turner et al., 2000, 2005; Schoop et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2007; Jawad et al., 2012). Three studies used viral challenge (Turner et al., 2000, 2005; Sperber et al., 2004) while the rest studied naturally occurring disease.

Table 2. Clinical trials and other human studies on the efficacy of Echinacea sp. against upper respiratory tract infections.

Evaluation of the quality of the studies is given in Table 3. “Random sequence generation” and “Allocation concealment” can give an indication of selection bias. Studies with minus or question mark in those columns are at a higher risk of selection bias than those with a plus.

The studies have evaluated the efficacy of Echinacea sp. from one or more of the following criteria:

- Number of episodes of cold or during treatment

- Duration of illness

- Additional painkillers or other pharmaceuticals used

- “symptom score”/severity of illness

- Virus count in nasal secretion

- Infection rate after viral challenge

All criteria had approximately as many positive as negative results, but “Infection rate after viral challenge,” described in three studies had only negative results. It was thus not possible to find a reduction in infection rate after virus challenge in patients taking echinacea prophylactics or for treatment of an induced cold.

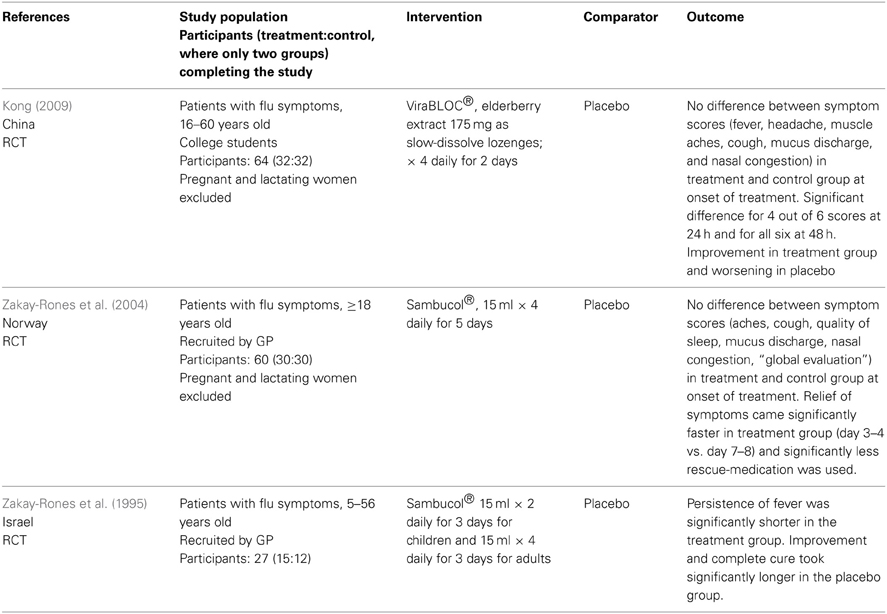

Neither human nor animal studies of the safety of Sambucus nigra in pregnancy were identified. Only three relevant studies on the efficacy of Sambucus nigra against URTI were identified (Zakay-Rones et al., 1995, 2004; Kong, 2009). All were randomized, controlled trials of various sizes; between 15 and 32 persons were treated with S. nigra. See Table 4.

Table 4. Clinical trials and other human studies on the efficacy of Sambucus nigra against upper respiratory tract infections.

Evaluation of the quality of the studies is given in Table 5. One study was slightly unclear about recruitment. In conclusion all studies are small, but apparently well conducted.

The studies have evaluated efficacy from one or more of the following criteria:

- Relief of symptoms

- Duration of illness

- Additional painkillers or other pharmaceuticals used

- Duration of fever

- Serological analyses/virus isolation

All three studies gave a positive result of the use of S. nigra against URTI, in the form of faster recovery.

The results from the human and animal studies of Echinacea sp. are not sufficient to conclude on the safety in pregnancy. The human study (Gallo et al., 2000) was prospective with respect to time of birth but the women had used various echinacea preparations in various doses for various durations. The preparations might contain any or all of the three most common Echinacea species. It is reassuring that no significant differences were found between the two groups in the study with respect to the outcomes studied, however with only 206 participants taking echinacea, less frequent unwanted effects cannot be ruled out. Of the 206 women who had used echinacea, 112 had done so during the first trimester. With an estimated baseline risk of major malformations of 3.5%, a study power ≥80% and an Alpha Error Level of 5% Gallo et al. (Gallo et al., 2000) could exclude a 3.5 times increase in baseline risk of major malformations (DSS Research, 2012). No firm conclusions on the risk of spontaneous abortions can be drawn from the animal studies. The extrapolation of the fetal resorption noticed in mice (Chow et al., 2006) to risk of abortion in humans lacks further documentation and with only three mice in the treatment and three in the control group the study gives a very weak indication of risk. The contradictive results on angiogenesis in only eight mice (Barcz et al., 2007) are difficult to relate to human conditions. The authors recommend that health care personnel omit communicating data from animal studies or other unconfirmed hypothesis to pregnant women.

No documentation is available about the safety of use of Sambucus nigra during pregnancy, and the extent of such use is only reported in Norway (Nordeng and Havnen, 2004). One study (Tsui et al., 2001) from the USA mentions use, but does not quantify it. This apparently limited use might explain the lack of safety data.

A case report is often the first indication of a risk, but none were located on either of the herbs. The lack of case reports can be due to the lack of side effects to report or because health care personnel do not ask pregnant women about herb use (Holst et al., 2009b) or the women do not report it and connections are not made. It is important that doctors or midwives in the antenatal care ask pregnant women about herb use and that they do it in a non-judgmental way. This non-judgmental approach is essential to get a reliable answer, and thereby acquiring more documentation.

To do a benefit-risk evaluation of a treatment there is a need for efficacy-data in addition to safety documentation. A method for benefit-risk analysis evaluation is given in the ICH guideline E2C from the EMA (European Medicines Agency, 2013c).

The studies evaluate efficacy from different criteria making comparison difficult. For echinacea only two criteria; “Virus count in nasal secretion” and “Infection rate after viral challenge” are objective. The others are according to patients' experience. The main findings in the studies are concerned with duration or severity of the cold but no firm conclusions can be drawn. This is in accordance with the latest Cochrane review last edited in 2009 (including articles up to 2005) which concludes that some preparations based on the herb of E. purpurea might be effective in reduction of duration and severity of a cold whereas others do not (Linde et al., 2006). An important disadvantage of the studies is that it is difficult to compare amounts of active substances given in the various studies due to different ways of defining them (see Table 2, column “Intervention”). The quality of the studies is variable (see Table 3). Schoop et al (Schoop et al., 2006) have published an open study, so lack of randomization is obvious, but the paper by Turner et al. from 2000 (Turner et al., 2005) lacks the information needed to evaluate how randomization and blinding is performed. Other studies are unclear with respect to randomization or blinding or both. Schulten et al. (2001) have performed their study with employees of the manufacturer of the study product which could probably bias the result. Of the seven studies with risk of bias, four showed negative results and three positive. The distribution of positive and negative results are also even over time. This indicates that the efficacy of Echinacea sp. is dubious based on the identified studies and combined with the lack of safety documentation the conclusion is that the products should not be recommended to pregnant women.

The documentation of efficacy of Sambucus nigra is also sparse with only three studies. The main criterion for evaluation of efficacy in those is “Relief of symptoms” but various others are included. Only the serological analyses or virus isolation performed in two studies (Zakay-Rones et al., 1995, 2004) are objective. The others are according to patients' experience. The three studies all conclude that the use of Sambucus nigra will lead to faster recovery from influenza. However, only 77 patients were given the treatment, therefore no firm conclusions can be drawn about efficacy. As there is also a lack of safety documentation Sambucus nigra should not be recommended to pregnant women.

It is possible that more studies on efficacy of Echinacea sp. are available in German or French but this review has only taken into consideration studies published in English or in Scandinavian languages (none found). This may be a limitation but there are good reasons to believe that if positive results were discovered, they would be published in English to reach as wide an audience as possible. Of note, we did not have access to the trademark-products used in the studies included in this review and consequently could not evaluate their legal status and their compliment with the official plant monographs (Blumenthal et al., 2000; European Medicines Agency, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012).

Documentation of efficacy against URTI and safety in pregnancy is insufficient to permit a benefit-risk evaluation of Echinacea sp. or Sambucus nigra against URTI in pregnancy. Health care personnel should therefore not advice pregnant women to use those herbs. The lack of data is not in itself an indication of a substantial risk to the fetus. Women who have already used the herbs in pregnancy should be told that the recommendation not to use the herbs is given due to lack of safety data, and not due to data showing adverse effects during pregnancy. This is important to avoid unnecessary anxiety.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank master student Ingebjørg Sandøy Rødahl for her initial work on the project and Ph.D. student Kristine Heitmann for her help with the list of references.

Barcz, E., Sommer, E., Nartowska, J., Balan, B., Chorostowska-Wynimko, J., and Skopinska-Rozewska, E. (2007). Influence of Echinacea purpurea intake during pregnancy on fetal growth and tissue angiogenic activity. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 45(Suppl. 1), S35–S39.

Barrett, B., Brown, R., Rakel, D., Mundt, M., Bone, K., Barlow, S., et al. (2010). Echinacea for treating the common cold a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 153, 769–777. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00003

Barrett, B. P., Brown, R. L., Locken, K., Maberry, R., Bobula, J. A., and D'Alessio, D. (2002). Treatment of the common cold with unrefined echinacea - A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 137, 939–946. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00006

Blumenthal, M., Goldberg, A., and Brinkmann, J. (eds.). (2000). Herbal Medicine. Expanded Comission E Monographs, 1 Edn. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine.

Brinkeborn, R. M., Shah, D. V., and Degenring, F. H. (1999). Echinaforce (R) and other Echinacea fresh plant preparations in the treatment of the common cold - A randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Phytomedicine 6, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(99)80027-0

Chow, G., Johns, T., and Miller, S. C. (2006). Dietary Echinacea purpurea during murine pregnancy: effect on maternal hemopoiesis and fetal growth. Biol. Neonate 89, 133–138. doi: 10.1159/000088795

Cuzzolin, L., Francini-Pesenti, F., Verlato, G., Joppi, M., Baldelli, P., and Benoni, G. (2010). Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 19, 1151–1158. doi: 10.1002/pds.2040

Dorn, M., Knick, E., and Lewith, G. (1997). Placebo-controlled, double-blind study of Echinaceae pallidae radix in upper respiratory tract infections. Complement. Ther. Med. 5, 40–42. doi: 10.1016/S0965-2299(97)80089-1

DSS Research. (2012). Researcher's Tool Kit. Statistical Power Calculator. Two Sample Tests Using Percentage Values. Available online at: https://www.dssresearch.com/KnowledgeCenter/toolkitcalculators/statisticalpowercalculators.aspx

Ensiyeh, J., and Sakineh, M. A. (2008). Comparing ginger and vitamin B6 for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Midwifery doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.10.013

European Medicines Agency. (2008). Community Herbal Monograph on Echinacea pururea (L.) Moench, herba recens. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMEA/HPMC/104945/2006Corr.

European Medicines Agency. (2009). Community Herbal Monograph on Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) Nutt., radix. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMEA/HMPC/332350/2008.

European Medicines Agency. (2010). Community Herbal Monograph on Echinacea pururea (L.) Moench, radix. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMA/HMPC/577784/2008.

European Medicines Agency. (2012). Community Herbal Monograph on Echinacea angustifolia DC., radix. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMA/HMPC/688216/2008.

European Medicines Agency. (2013a). Public Statement on Samucus nigra L., fructus (Draft). Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMA/HMPC/32465/2013.

European Medicines Agency. (2013b). Assessment Report on Sambucus nigra L., fructus (Draft). Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: European Medicines Agency, Contract No.: EMA/HMPC/44208/2012.

European Medicines Agency. (2013c). ICH Guideline E2C (R2) on Periodic Benefit-Risk Evaluation Report (PBRER). Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). London: European Medicines Agency, contract No.: EMA/CHMP/ICH/544553/1998.

Facchinetti, F., Pedrielli, G., Benoni, G., Joppi, M., Verlato, G., Dante, G., et al. (2012). Herbal supplements in pregnancy: unexpected results from a multicentre study. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3161–3167. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des303

Forster, D. A., Denning, A., Wills, G., Bolger, M., and McCarthy, E. (2006). Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-21

Gallo, M., Sarkar, M., Au, W., Pietrzak, K., Comas, B., Smith, M., et al. (2000). Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to echinacea: a prospective controlled study. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 3141–3143. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3141

Goel, V., Lovlin, R., Barton, R., Lyon, M. R., Bauer, R., Lee, T. D. G., et al. (2004). Efficacy of a standardized echinacea preparation (Echinilin (TM)) for the treatment of the common cold: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 29, 75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2003.00542.x

Goel, V., Lovlin, R., Chang, C., Slama, J. V., Barton, R., Gahler, R., et al. (2005). A proprietary extract from the Echinacea plant (Echinacea purpurea) enhances systemic immune response during a common cold. Phytother. Res. 19, 689–694. doi: 10.1002/Ptr.1733

Grimm, W., and Muller, H. H. (1999). A randomized controlled trial of the effect of fluid extract of Echinacea purpurea on the incidence and severity of colds and respiratory infections. Am. J. Med. 106, 138–143. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00406-9

Hall, H., Fahlman, M. M., and Engels, H. J. (2007). Echinacea purpurea and mucosal immunity. Int. J. Sports Med. 28, 792–797. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-964895

Heitmann, K., Holst, L., Nordeng, H., and Haavik, S. (2010). Attitudes to use of herbal medicine during pregnancy. Norsk Farmaceutisk Tidsskrift 118, 16–19. Available online at: http://www.farmatid.no/id/4103.0

Heitmann, K., Nordeng, H., and Holst, L. (2013). Safety of ginger use in pregnancy: results from a large population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69, 269–277. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1331-5

Hepner, D. L., Harnett, M., Segal, S., Camann, W., Bader, A. M., and Tsen, L. C. (2002). Herbal medicine use in parturients. Anesth. Analg. 94, 690–693. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00039

Higgins, J. P. T., and Green, S. (eds.). (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. [Updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available online at: www.cochrane-handbook.org

Hoheisel, O., Sandberg, M., Bertram, S., Bulitta, M., and Schäfer, M. (1997). Echinagard treatment shortens the course of the common cold: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Res. 9, 261–268.

Holst, L., Wright, D., Haavik, S., and Nordeng, H. (2009a). The use and the user of herbal remedies during pregnancy. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 787–792. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0467

Holst, L., Wright, D., Nordeng, H., and Haavik, S. (2009b). Use of herbal preparations during pregnancy: focus group discussion among expectant mothers attending a hospital antenatal clinic in Norwich, UK. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 15, 225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.04.001

Jawad, M., Schoop, R., Suter, A., Klein, P., and Eccles, R. (2012). Safety and efficacy profile of Echinacea purpurea to prevent common cold episodes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012:841315. doi: 10.1155/2012/841315

Kong, F.-K. (2009). Pilot clinical study on a proprietary elderberry extract: efficacy in addressing influenza symptoms. Online J. Pharmacol. Pharmacokin. 5:32.

Koren, G., and Nordeng, H. M. (2013). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and malformations: case closed? Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 18, 19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.004

Lapi, F., Vannacci, A., Moschini, M., Cipollini, F., Morsuillo, M., Gallo, E., et al. (2008). Use, attitudes and knowledge of complementary and alternative drugs (CADs) among pregnant women: a preliminary survey in Tuscany. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 7, 477–486. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen031

Linde, K., Barrett, B., Wolkart, K., Bauer, R., and Melchart, D. (2006). Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD000530. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2

Lindenmuth, G. F., and Lindenmuth, E. B. (2000). The efficacy of echinacea compound herbal tea preparation on the severity and duration of upper respiratory and flu symptoms: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 6, 327–334. doi: 10.1089/10755530050120691

Melchart, D., Walther, E., Linde, K., Brandmaier, R., and Lersch, C. (1998). Echinacea root extracts for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections - A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Arch. Fam. Med. 7, 541–545. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.541

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Nordeng, H., and Havnen, G. C. (2004). Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 13, 371–380. doi: 10.1002/pds.945

Norwegian Institute of Public Health. (2007). What is the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study?: Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Available online at: http://www.fhi.no/artikler/?id=65519

O'Neil, J., Hughes, S., Lourie, A., and Zweifler, J. (2008). Effects of echinacea on the frequency of upper respiratory tract symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 100, 384–388. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60603-5

Ozgoli, G., Goli, M., and Simbar, M. (2009). Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 243–246. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0406

Pongrojpaw, D., Somprasit, C., and Chanthasenanont, A. (2007). A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 90, 1703–1709. Available online at: http://www.medassocthai.org/journal

Schaefer, C., Peters, P., and Miller, R. (eds.). (2007). Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation. London: Elsevier

Schoop, R., Buechi, S., and Suter, A. (2006). Open, multicenter study to evaluate the tolerability and efficacy of Echinaforce Forte tablets in athletes. Adv. Ther. 23, 823–833. doi: 10.1007/Bf02850324

Schulten, B., Bulitta, M., Ballering-Bruhl, B., Koster, U., and Schafer, M. (2001). Efficacy of Echinacea purpurea in patients with a common cold - A placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung 51, 563–568. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300080

Schwarz, E., Metzler, J., Diedrich, J. P., Freudenstein, J., Bode, C., and Bode, J. C. (2002). Oral administration of freshly expressed juice of Echinacea purpurea herbs fail to stimulate the nonspecific immune response in healthy young men: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. J. Immunother. 25, 413–420. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200209000-00005

Sperber, S. J., Shah, L. P., Gilbert, R. D., Ritchey, T. W., and Monto, A. S. (2004). Echinacea purpurea for prevention of experimental rhinovirus colds. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 1367–1371. doi: 10.1086/386324

Tsui, B., Dennehy, C. E., and Tsourounis, C. (2001). A survey of dietary supplement use during pregnancy at an academic medical center. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185, 433–437. Epub 2001/08/24. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116688

Turner, R. B., Bauer, R., Woelkart, K., Hulsey, T. C., and Gangemi, J. D. (2005). An evaluation of Echinacea angustifolia in experimental rhinovirus infections. New Engl. J. Med. 353, 341–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044441

Turner, R. B., Riker, D. K., and Gangemi, J. D. (2000). Ineffectiveness of echinacea for prevention of experimental rhinovirus colds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 1708–1709. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.6.1708-1709.2000

Yale, S. H., and Liu, K. J. (2004). Echinacea purpurea therapy for the treatment of the common cold - A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1237–1241. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1237

Zakay-Rones, Z., Thom, E., Wollan, T., and Wadstein, J. (2004). Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J. Int. Med. Res. 32, 132–140. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200205

Zakay-Rones, Z., Varsano, N., Zlotnik, M., Manor, O., Regev, L., Schlesinger, M., et al. (1995). Inhibition of several strains of influenza virus in vitro and reduction of symptoms by an elderberry extract (Sambucus nigra L.) during an outbreak of influenza B Panama. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 1, 361–369. doi: 10.1089/acm.1995.1.361

Keywords: Echinacea, Elderberry, pregnancy, safety, efficacy, CAM, respiratory infection

Citation: Holst L, Havnen GC and Nordeng H (2014) Echinacea and elderberry—should they be used against upper respiratory tract infections during pregnancy? Front. Pharmacol. 5:31. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00031

Received: 20 December 2013; Paper pending published: 16 January 2014;

Accepted: 17 February 2014; Published online: 04 March 2014.

Edited by:

Abidemi James Akindele, University of Lagos, NigeriaReviewed by:

He-Hui Xie, Second Military Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2014 Holst, Havnen and Nordeng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lone Holst, Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care and Centre for Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Bergen, PO Box 7804, 5020 Bergen, Norway e-mail:bG9uZS5ob2xzdEBmYXJtLnVpYi5ubw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.