95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 11 June 2012

Sec. Neuropharmacology

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2012.00107

This article is part of the Research Topic Potassium channels and calcium signaling in physiology and pathophysiology of the brain View all 8 articles

Calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels are present throughout the central nervous system as well as many peripheral tissues. Activation of KCa channels contribute to maintenance of the neuronal membrane potential and was shown to underlie the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) that regulates action potential firing and limits the firing frequency of repetitive action potentials. Different subtypes of KCa channels were anticipated on the basis of their physiological and pharmacological profiles, and cloning revealed two well defined but phylogenetic distantly related groups of channels. The group subject of this review includes both the small conductance KCa2 channels (KCa2.1, KCa2.2, and KCa2.3) and the intermediate-conductance (KCa3.1) channel. These channels are activated by submicromolar intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and are voltage independent. Of all KCa channels only the KCa2 channels can be potently but differentially blocked by the bee-venom apamin. In the past few years modulation of KCa channel activation revealed new roles for KCa2 channels in controlling dendritic excitability, synaptic functioning, and synaptic plasticity. Furthermore, KCa2 channels appeared to be involved in neurodegeneration, and learning and memory processes. In this review, we focus on the role of KCa2 and KCa3 channels in these latter mechanisms with emphasis on learning and memory, Alzheimer’s disease and on the interplay between neuroinflammation and different neurotransmitters/neuromodulators, their signaling components and KCa channel activation.

It is widely accepted that the trigger for neurotransmitter release is the entry of calcium ions (Ca2+) into the presynaptic terminal (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995). Because of this role of Ca2+ in neurotransmitter release, many neuronal functions are dependent on dynamics of Ca2+ signaling. Resting levels of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) in neurons are maintained at very low levels, but can be increased by influx of extracellular Ca2+ through voltage-, receptor-, or store-operated channels on the plasma membrane or by release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, predominantly the ryanodine receptor and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor dependent endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Most Ca2+ signals are delivered as brief transients with spatial and temporal properties. The frequency of the repetitive transients and the [Ca2+]i obtained encode information to control cellular processes. Also the localization of these events at specific regions of the cell (Ca2+ microdomains), for instance at the plasma membrane or ER, contribute to the regulation of these cellular processes (Berridge, 2006). The regulation of these dynamics of the [Ca2+]i at the Ca2+ microdomain level is critical for proper neuronal activity, because insufficient levels of [Ca2+] can lead to impaired functioning whereas excessive cytosolic [Ca2+] levels can cause overstimulation and ultimately cell death (Berridge et al., 1998).

One way to maintain appropriate intracellular [Ca2+] is repolarization of the membrane potential by initiating K+ efflux from the cell. Increased K+ permeability in response to elevated cytosolic [Ca2+] was first described in human erythrocytes (Gardos, 1958). Slow hyperpolarizing effects observed after stimulation of adrenergic, cholinergic, or purinergic pathways in smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract were caused by such an increase in K+ permeability as detected by the use of apamin (Banks et al., 1979; Maas and Den Hertog, 1979; Shuba and Vladimirova, 1980; Den Hertog, 1982). This neurotoxic polypeptide was isolated from bee-venom and, when injected in rodents in purified form, exerted severe uncoordinated movements of the skeletal musculature increasing to spasms and convulsions of apparently spinal origin after a dose-dependent lag time (Habermann, 1984). Apamin specifically blocks Ca2+-activated K+ channels and turned out to be the archetypical blocker for these channels. Such a specific blockade was demonstrated for the first time in guinea-pig taenia caeci in which changes in membrane potential and muscle contraction were measured using the sucrose-gap method in combination with 42K+ efflux (Den Hertog, 1981) and in differentiating neuroblastoma cells using voltage-clamp electrophysiology (Hugues et al., 1982). Voltage-insensitive Ca2+-activated K+ channels of the small conductance-type (KCa) were later identified to carry these apamin-sensitive currents (Blatz and Magleby, 1986).

Based on their pharmacological and molecular properties a number of different Ca2+-activated K+ channels can be identified. The International Union of Pharmacology has put the Ca2+-activated K+ channels into one family which can be subdivided into two functionally defined, but genetically unrelated groups (Wei et al., 2005). The first group consists of four voltage-insensitive Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Köhler et al., 1996; Ishii et al., 1997; Joiner, 1997) of which KCa3.1 (formerly called Gardos channel or intermediate-conductance channel IK1) has a single channel conductance of 11 pS and is not blocked by apamin. The other three members of this phylogenetic tree, the KCa channels KCa2.1, KCa2.2, and KCa2.3, also known as SK1, SK2, and SK3, with a smaller conductance of 8–10 pS, are specifically blocked by apamin in the nM range (Wei et al., 2005). The other group consists of four members of which the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+channel (KCa1.1, also known as BK channel) is functionally related to the former group. It is voltage-dependent with a single channel conductance of 260 pS. The three other members of this group are structurally related channel-types which are surprisingly not activated by intracellular Ca2+.

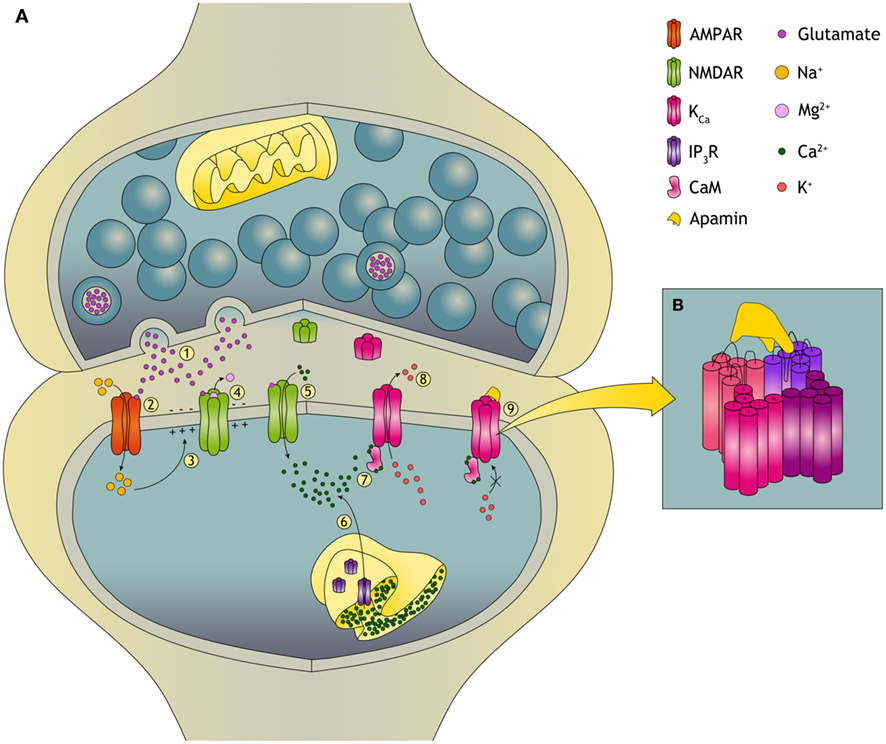

KCa channels resemble the serpentine transmembrane topology of voltage-activated K+ channels consisting of six transmembrane domains and a P loop region between domain S5 and S6, containing the K+-selective filter, and intracellular N and C termini (Faber, 2009). Apamin has different affinities for the KCa2 channel subtypes. The toxin is most potent at KCa2.2 channels (IC50 ∼ 70 pM) followed by KCa2.3 channels (IC50 ∼ 0.63–6 nM) and the human isoform of KCa2.1 channels (IC50 ∼ 1–8 nM; Köhler et al., 1996; Nolting et al., 2007; Lamy et al., 2010; Weatherall et al., 2010). Interestingly, the rat isoform of KCa2.1 channel is apamin insensitive (D’Hoedt et al., 2004). Apamin does not simply obstruct the pore, but blocks by an allosteric mechanism in which outer pore residues are involved (Lamy et al., 2010). However, apamin must bind to both the S3–S4 extracellular loop and the outer pore to block KCa2 channel current by an allosteric mechanism. A three-amino-acid motif in the S3–S4 loop is a crucial determinant of the sensitivity of the apamin blockade. Since the motif SYA in KCa2.2 channels, SYT in KCa2.3 channels and TYA in human KCa2.1 channels is required for binding and block by apamin, this suggests that a change in pore shape underlies the allosteric block (Weatherall et al., 2011). Rat KCa2.1 channels display SLV in the S3–S4 loop that prevents binding of apamin, despite having the same pore sequence as the other isoforms (Weatherall et al., 2011). Functional KCa2 channels assemble as homomeric tetramers (Köhler et al., 1996), but could also co-assemble different subunits into heteromeric channels (Strassmaier et al., 2005; Weatherall et al., 2011). Recently, it was proposed that in heteromeric channels the binding site for apamin is formed by two adjacent subunits, the outer pore region of one and the S3–S4 loop of the other subunit (Weatherall et al., 2011; Figure 1B). The relative abundance of heteromeric or homomeric channel assembly and their physiological relevance for signal transduction is not understood at the moment.

Figure 1. Plasticity in the glutamatergic synapse and the role of KCa channels. (A)(1) During synaptic transmission, glutamate is released from the presynaptic neuron and acts on the two primary excitatory glutamate receptors: AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate) receptors and NMDA (N-Methyl-D-Aspartate) receptors. (2) Na+ flows only through AMPARs and not through NMDARs because the NMDAR is blocked by a voltage-dependent Mg2+ block. (3) Influx of Na+ causes depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron. (4) The depolarization relieves the Mg2+ block of the NMDAR and an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) is induced. (5) This allows, next to Na+, for Ca2+ influx into the dendritic spine. Changes in the dendritic spine Ca2+ concentration can initiate synaptic plasticity. The dynamics of changes in [Ca2+] upon tetanic stimulation determines whether the synapse will undergo long-term potentiation (LTP) or long-term depression (LTD). (6) Ca2+ can also be released from the ER, predominantly dependent on ryanodine receptors and inositol trisphosphate receptors (IP3R). (7) When intracellular levels of Ca2+ increase, KCa channels are activated through calmodulin (CaM). Ca2+ binds to CaM and CaM induces a conformational change that leads to opening of the channel pore. (8) Opening of the KCa channel leads to K+ efflux. KCa channels also facilitate reestablishment of the Mg2+ block of the NMDARs which reduces Ca2+ influx. In this way opening of KCa channels provides a negative feedback on the EPSP through their repolarizing effect. (9) Binding of apamin to the KCa channel blocks the channel and induces an increased EPSP. (B) Apamin does not obstruct the pore of the KCa channel but blocks it by an allosteric mechanism. The binding site for apamin is formed by two adjacent subunits, the S3–S4 extracellular loop of one and the loops of the outer pore of the other, also providing a block on heteromeric channels.

Calmodulin (CaM) is constitutively bound to the C terminus of the channel (Xia et al., 1998; Schumacher et al., 2001). Binding of Ca2+ to CaM leads to a conformational change enabling opening of the channel and K+ efflux (Figure 1A). Direct modulation of the channel can be obtained by phosphorylation, since the protein has multiple predicted phosphorylation sites (Köhler et al., 1996). For example, phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase reduces the plasma membrane localization of KCa2 channels and contributes in this way to long-term potentiation (LTP; Faber et al., 2005; Ren et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2008). Modulation of channel activity can also be achieved by constitutively bound protein kinase CK2 (Casein Kinase 2) and protein phosphatase 2A. CK2 phosphorylates channel-bound CaM in the closed channel state thereby reducing the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. In the open state, dephosphorylation of CaM by protein phosphatase 2A increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel (Allen et al., 2007). Therefore, Ca2+ sensitivity is dependent on the intracellular Ca2+ levels enabling KCa channels to closely follow neuronal activity. Recently, these aspects of KCa channel signaling have been excellently reviewed (Adelman et al., 2012).

KCa2 channels interact with a large number of pharmacological agents (Faber and Sah, 2007; Pedarzani and Stocker, 2008). Apart from apamin, other peptides, like leiurotoxin I and tamapin were found to block the channels at the nanomolar range. Most of the organic blockers and inhibitors are needed in micromolar concentrations to block the channels, except for UCL1684 and UCL1848, which also block at the nanomolar range (Shah and Haylett, 2000; Strobaek et al., 2000; Fanger et al., 2001; Hosseini et al., 2001; Benton et al., 2003). A different set of toxins is available to block KCa3.1 channels of which maurotoxin and charybdotoxin are the most effective (low nanomolar range). In addition, triarylmethane derivatives block KCa3.1 channels at the nanomolar range (Ghanshani et al., 2000; Visan et al., 2004). Enhancers of channel activity are also available. Most of them work at the micromolar range (Pedarzani and Stocker, 2008), like 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone (1-EBIO) which acts on KCa2.1, KCa2.2, and KCa2.3 channels (Lappin et al., 2005) as well as on KCa3.1 channels (Jensen et al., 1998; Lappin et al., 2005). The only enhancer with higher affinity is NS309, acting on these channels at the nanomolar range (Strobaek et al., 2004). The positive modulator CyPPA is selective for KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 channels at the low micromolar range and virtually inactive toward KCa2.1 and KCa3.1 channels (Hougaard et al., 2007).

KCa channels are widely distributed throughout peripheral tissues and in the central nervous system. In the peripheral tissues mRNA of the KCa channels has partially overlapping but clearly distinct distribution patterns. KCa2.1 channels are only found in low quantities in the ovaries and testes. KCa2.2 channels are, next to other areas, present in the adrenal glands, heart, kidneys, liver, prostate, and urinary bladder. KCa2.3 shows distinctive distribution to the small intestine, rectum, omentum, myometrium, and skeletal muscles (Chen et al., 2004). Immunohistochemistry also revealed the presence of KCa2.3 protein in the cell bodies and processes of cultured rat superior cervical ganglion neurons and KCa2.3 protein was identified as a major component of the KCa channels responsible for the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) in these cells (Hosseini et al., 2001). KCa3.1 channels are abundantly distributed in peripheral tissues like lymphocytes (Ghanshani et al., 2000), erythrocytes (Vandorpe et al., 1998), endothelium (Eichler et al., 2003), and smooth muscle cells (Köhler et al., 2003), but they are also present on the placenta, prostate, rectum, salivary glands, trachea, and tonsils (Chen et al., 2004). The different channels have been implicated in various physiological functions like volume regulation of erythrocytes (Brugnara et al., 1996; Vandorpe et al., 1998), vasodilatation (Eichler et al., 2003), and proliferation of lymphocytes (Jensen et al., 1999), proliferation of vascular endothelial (Grgic et al., 2005), and proliferation of smooth muscle cells (Köhler et al., 2003).

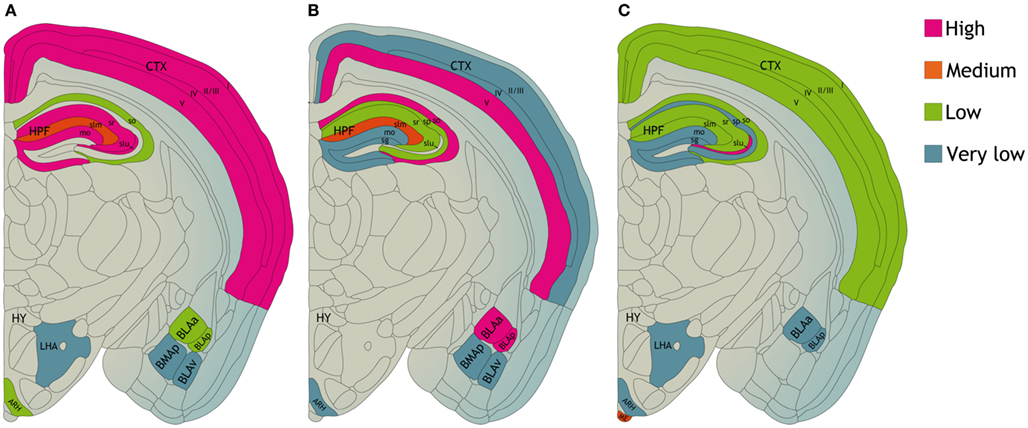

Different subunits of the KCa channels are widely distributed throughout the brain (Figure 2). KCa2.1 and KCa2.2 channels are often expressed in the same neurons, predominantly in the neocortex, hippocampal formation, and cerebellum. In the hippocampal formation KCa2.1 channel immunolabeling is most pronounced in the neuropil of layers CA1–CA3, in particular in the stratum radiatum. KCa2.2 channel labeling is strongest in the CA1–CA2 stratum radiatum and stratum oriens (Sailer et al., 2002, 2004). KCa2.3 subunits are also present in the hippocampal formation, most prominent in the hilus and in the stratum lucidum of CA3. In the rest of the brain KCa2.3 subunits show a complementary distribution to KCa2.1 and KCa2.2 subunits. KCa2.3 subunits are present in subcortical regions like midbrain nuclei (Rimini et al., 2000; Stocker and Pedarzani, 2000; Tacconi et al., 2001; Sailer et al., 2002, 2004; Chen et al., 2004). In dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord of the rat sensory nervous system, all KCa2 channel subtypes are expressed. Co-localization of channel expression with calcitonin gene-related peptide and isolectin B4-labeled neurons provides evidence for their presence in nociceptors (Mongan et al., 2005). Their level of expression, however, was not altered following induction of inflammation or nerve injury, suggesting that channel modulation rather than expression contributes to the changes in neuronal excitability observed under these “pathological” circumstances (Mongan et al., 2005).

Figure 2. Distribution of (A) KCa2.1, (B) KCa2.2, and (C) KCa2.3 proteins in various compartments of the mouse central nervous system. CTX, neocortex. HPF, hippocampal formation CA1–CA3 region; so, stratum oriens; sp, stratum pyramidale; sr, stratum radiatum; slm, stratum lacunosum moleculare; slu, stratum lucidum. Dentate gyrus; mo, molecular layer; sg, granule cell layer. HY, hypothalamus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; ARH, arcuate hypothalamic nucleus; ME, median eminence. BLAa, basolateral amygdalar nucleus, anterior part; BLAp, basolateral amygdalar nucleus, posterior part; BLAv, basolateral amygdalar nucleus, ventral part; BMAp, basomedial amygdalar nucleus, posterior part based on data from Sailer et al. (2004).

Within neurons, KCa2.1 and KCa2.2 channels are primarily found in somatic and dendritic areas. KCa2.2 channels have been shown to be present in hippocampal CA1 dendritic spines (Lin et al., 2008). KCa2.3 channels are associated with fibers extending from layer 5 to layer 1 in the neocortex (Rimini et al., 2000; Stocker and Pedarzani, 2000; Tacconi et al., 2001; Sailer et al., 2002, 2004; Chen et al., 2004). KCa3.1 channels are present in dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord and on cultured microglial cells from rat and mouse brain (Khanna et al., 2001; Schilling et al., 2002; Mongan et al., 2005; Kaushal et al., 2007). In microglial cells, KCa3.1 channels are activated by sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid and play a role in the respiratory bursts of reactive oxygen species generated after activation of microglia (Khanna et al., 2001; Schilling et al., 2002). The properties of the different channels have been reviewed in detail (Pedarzani and Stocker, 2008), and in particular as possible targets for therapeutic interventions because in the past few years the role of KCa channels in disease is becoming more and more clear (Chandy et al., 2004; Wulff and Zhorov, 2008). The distribution of the different KCa channels gives the channels the ability to play a role in many processes like dendritic excitability, contributing to the AHP that follows an action potential, synaptic functioning, and plasticity (Xia et al., 1998; Ngo-Anh et al., 2005) and thereby modulating firing patterns of action potentials, all processes known for their involvement in learning and memory and in neurodegenerative diseases. The main focus of this review is the role of KCa channels in neurodegenerative processes, and in learning and memory. However, to place KCa channel research in a historical perspective first two important peripheral pathways which are under control of KCa channels will be discussed.

KCa channels are important participants in inhibitory neurotransmission in gastrointestinal smooth muscles (Banks et al., 1979; Maas et al., 1980; Shuba and Vladimirova, 1980). Three isoforms of the KCa2 channel family were cloned from murine and canine proximal colon smooth muscle (Ro et al., 2001). The mRNA of each subunit was expressed at different levels in murine colonic smooth muscles in the following sequence: KCa2.2 > KCa2.3 > KCa2.1 channels. In contrast, no mRNA for these channels could be detected in canine colonic smooth muscle. Immunoreactivity against KCa2.3 channels was present at the plasma membrane of circular and longitudinal muscle as well as in myenteric ganglia. Variation in the KCa2 channel expression suggests that they may contribute differentially to inhibitory junction potentials (Ro et al., 2001). A role for KCa2 channels in spontaneous motility of the gastrointestinal tract has been suggested. KCa2.3-immunoreactive cells were positive for c-kit, a marker for the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), but not for glial fibrillary acidic protein in the ileum and stomach. Immunoelectron microscopic analysis indicates that KCa2.3 channels are localized on processes of ICC that are located close to the myenteric plexus between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers and within the muscular layers. Because ICC have been identified as pacemaker cells and are known to play a major role in generating the regular motility of the gastrointestinal tract, these findings suggest that KCa2.3 channels, which are expressed specifically in ICC, play an important role in generating a rhythmic pacemaker current in the gastrointestinal tract (Fujita et al., 2001).

The endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) system is a major vasodilator mechanism (Taylor and Weston, 1988; Félétou and Vanhoutte, 2007, 2009; Edwards et al., 2010). The function of the EDHF system requires activation of endothelial KCa channels (Edwards et al., 2010), e.g., KCa3.1 channels (Ishii et al., 1997) and KCa2.3 channels (Köhler et al., 1996). Contribution of KCa channels has been implicated in endothelial dysfunction in many experimental models of vascular disease (Félétou and Vanhoutte, 2009), among which are coronary microvascular dysfunction (Gschwend et al., 2003; Feng et al., 2008), hypercholesterolemia (Ding et al., 2005; Morikawa et al., 2005), and diabetes (Dalsgaard et al., 2009; Brøndum et al., 2010; Matsumoto et al., 2010). A possible role for these channels in antihypertensive therapy is emerging (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2009). Newly developed activators were shown to potentiate EDHF-mediated dilations of carotid arteries from KCa3.1(+/+) mice but not from KCa3.1(−/−) mice. Administration of these activators lowered mean arterial blood pressure by 4 and 6 mmHg in normotensive mice and by 12 mmHg in angiotensin-II-induced hypertension. These effects were absent in KCa3.1-deficient mice. In addition, changes in arterial blood flow for 24 h modify the function of the endothelial KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels before arterial structural remodeling in rat mesenteric arteries. Reduction of blood flow blunts endothelium-dependent relaxation due to a reduction in the EDHF response. An increase in blood flow leads to an enhanced contribution of KCa3.1 channels to the EDHF relaxation, as indicated by the use of specific blockers (Hilgers et al., 2010). An endothelium-specific antihypertensive therapy based on pharmacological activation of these channels is also supported by recent experiments in dogs showing that activation of KCa2.3/KCa3.1 channels produces endothelial hyperpolarization and lowers arterial blood pressure by an immediate electrical vasodilator mechanism (Damkjaer et al., 2012). Apart from their role in cardiovasculature, KCa3.1, KCa2.2, and KCa2.3 channels are also functional in endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in porcine retinal arterioles (Dalsgaard et al., 2010), and very important in the regulation of contraction mechanisms of brain (micro)vasculature to maintain homeostasis of the brain (Zhou et al., 2010).

KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels are expressed in cerebral blood vessels and play a significant role in the regulation of local blood flow (Marrelli et al., 2003; Faraci et al., 2004; McNeish et al., 2005). The release of K+ through the channels accumulates in the myo-endothelial space between the endothelial cells and myocytes of small arteries, causing an increase in the extracellular K+ concentration (Edwards et al., 2010). This increased extracellular K+ results in hyperpolarization of the myocyte and leads to smooth muscle relaxation and vascular dilation (Weston et al., 2002; Longden et al., 2011). Activity of KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels can play an important role in vascular dynamics under pathophysiological conditions, like cerebral ischemia. An EDHF-mediated relaxation mechanism is present in the carotid artery – together with the vertebral arteries the main feed path for blood supply to the brain – as well as in cerebral parenchymal arterioles (McNeish et al., 2006; Leuranguer et al., 2008; Cipolla et al., 2009; Sankaranarayanan et al., 2009). The EDHF component can activate KCa2 and KCa3.1 channel activity, regulating cerebral blood flow and contributing to the basal tone of cerebral parenchymal arterioles. Activators of KCa3.1 channel activity were shown to potentiate EDHF-mediated dilations of rat middle cerebral arteries (Marrelli et al., 2003), the carotid arteries in mouse (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2009) and in guinea-pig which is mediated by stimulation of both KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels (Leuranguer et al., 2008). Endothelial KCa2 and KCa3 channels regulate rat brain parenchymal arteriolar diameter and basal tone (Cipolla et al., 2009; Hannah et al., 2011) and via these endothelial mechanisms can determine cortical cerebral blood flow as was demonstrated in mice (Hannah et al., 2011). After cerebral ischemia and subsequent reperfusion, EDHF responsiveness was preserved in rat parenchymal arterioles, in contrast to the diminished response to nitric oxide synthase inhibition, providing further support for an important physiological role for KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels under pathophysiological conditions (Cipolla et al., 2009). KCa channels do not only play a role in regulating blood flow to different brain regions, but also in maintenance of the structure of the blood-brain barrier as the activation of KCa2.2 channels is necessary for ATP-induced proliferation of brain capillary endothelial cells (Yamazaki et al., 2006).

In addition to effects on the (micro)vasculature, KCa channels are also involved in the pathogenic mechanisms subsequent to the ischemic event. Cerebral ischemia induced in mice by cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation caused hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuronal cell death associated with delayed and sustained reduction of synaptic KCa2.2 channel activity (Allen et al., 2011b). Treatment of mice with the KCa channel activator 1-EBIO 30 min before cardiac arrest prevented ischemia-induced synaptic channel internalization, restored channel activity, and reduced ischemia-induced cell death (Allen et al., 2011b). The brain infarct area obtained after occlusion of the middle cerebral artery of the rat could be reduced by ±50% by blocking KCa3.1 channels, probably reflecting reduced microglia activity (Chen et al., 2011). During stroke there is strong increase of glutamate release and overstimulation of nerve cells, which goes together with very high calcium levels in neurons and their death. The role of KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels in NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity will be addressed in the section “Neurodegenerative diseases.”

Learning is by definition the result of processes by which experiences produce long-term and lasting changes in the nervous system. Memory formation is derived from those changes (Morgado-Bernal, 2011). Memory formation and persistent memory storage are accompanied by structural changes and synaptic plasticity of dendritic spines. Due to repetitive activation of excitatory glutamatergic synapses, particularly in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, an increase in synaptic strength is established, also known as LTP (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). LTP is a form of plasticity that has been studied extensively in the hippocampus region of the brain. Plasticity is facilitated by phosphorylation of AMPA receptors and NMDA receptors. These receptors are the two primary excitatory glutamate receptors which can be found at the postsynaptic site of excitatory synapses. NMDARs particularly can be found on almost all neurons in the central nervous system and are ligand-gated non-selective cation channels which facilitate the flow of K+, Na+, and Ca2+ (Debanne et al., 2004; Yamin, 2009; Malenka and Malinow, 2011). In hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, changes in dendritic spine Ca2+ concentration can initiate synaptic plasticity via the NMDA receptors (El-Hassar et al., 2011; O’Donnell et al., 2011). KCa2 channels are able to dampen synaptic plasticity, because KCa2 channels have been shown to be present in the hippocampal CA1 synaptic membrane of dendritic spines in the postsynaptic density (PSD), where they are colocalized with NMDA receptors (Lin et al., 2008; Allen et al., 2011b). During an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), Ca2+ enters a neuron through NMDARs and nearby KCa2 channels are activated. Opening of KCa2 channels has a repolarizing effect and the EPSP is reduced, firstly by providing K+ efflux and secondly through modulation of the membrane potential. Opening of KCa2 channels can facilitate reestablishment of the Mg2+ block of the NMDARs which reduces Ca2+ influx (Allen et al., 2011b). By regulating Ca2+ concentrations, KCa2 channels can alter the threshold for the induction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and modulate EPSPs underlying the induction of LTP (Hammond et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2008). In concordance with these results it has been shown that during LTP induction in mouse hippocampus, KCa2 channels are internalized into the dendritic spine due to PKA phosphorylation of three serine residues in the KCa2.2 C-terminal domain. Internalization of KCa2 channels abolishes KCa2 channel activity in the potentiated synapses and this results in increased EPSP (Lin et al., 2008; Figure 1).

Since KCa2 channels reduce synaptic plasticity, it can be expected that inhibition of KCa2 channels improves learning. Indeed, the excitability of rat hippocampal neurons can be enhanced by blocking KCa2 channels with apamin within a nanomolar concentration range (Behnisch and Reymann, 1998). In mice, hippocampal learning and induction of synaptic plasticity can be increased with apamin treatment (Stackman et al., 2002). Blocking KCa2 channels can remove the negative feedback on NMDARs, while LTP induction can be facilitated by NMDAR-dependent Ca2+ signals within dendritic spines in the hippocampal CA1 area (Stackman et al., 2002; Faber et al., 2005; Ngo-Anh et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2011a). The KCa channel subtype KCa2.2 especially appears to be involved in regulating CA1 plasticity and excitability, because genetic deletion of KCa2.2 channels, but not KCa2.1 or KCa2.3, abolishes the effect of apamin (Bond et al., 2004). The KCa2.2 channel has two isoforms, KCa2.2-long (KCa2.2-L) and KCa2.2-short (KCa2.2-S), which are coexpressed in CA1 pyramidal neurons. In mice lacking KCa2.2-L isoform, KCa2.2-S-containing channels are expressed in the extrasynaptic spine plasma membrane but they are specifically excluded from the PSD of dendritic spines. Due to this exclusion, apamin does not increase EPSPs or LTP in these mice. It is suggested that the KCa2.2-L isoform directs synaptic KCa2.2 channel expression and is important for normal synaptic signaling, plasticity, and learning (Allen et al., 2011a).

Many studies on the role of KCa2 channels in learning and memory consolidation have been performed using various kinds of behavioral tasks and paradigms in rodents. Hippocampal-dependent learning and memory can be tested using spatial learning tasks, like radial arm mazes, Y- or T-mazes and water mazes, avoidance test, fear conditioning, eyeblink conditioning, or using novel object-recognition tasks (Geinisman et al., 2001; Borght van der et al., 2005; Havekes et al., 2006; Morgado-Bernal, 2011). It was shown that in the early stages of a spatial learning task KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 mRNA levels were transiently downregulated, suggesting an endogenous regulation of KCa2 channels involved in learning (Mpari et al., 2010). In the hippocampus of aged mice an elevated expression of KCa2.3 channels contributes to an age-related reduction in performance on learning tasks, synaptic plasticity, and LTP (Blank et al., 2003). However, mice lacking KCa2.3 channels show short-term learning and memory deficits in their performance in an alternation arm maze test (Jacobsen et al., 2009). Mice treated with apamin also demonstrate accelerated hippocampal-dependent spatial and non-spatial memory encoding. Apamin-treated mice require fewer trials to learn the location of a hidden platform in the Morris water maze. In mice, and also rats, apamin facilitates the encoding of object memory in an object-recognition task, as assessed by habituation of exploratory activity. Moreover, apamin improves performance on the novel object-recognition task (Deschaux et al., 1997; Stackman et al., 2002). Amygdala-dependent learning or emotional learning is tested with inhibitory avoidance tests, contextual fear memory tests, and with the appetitive motivated response. Blockade of KCa2 channels with systemically administered apamin was shown to facilitate memory processes in conditioning for an appetitively motivated bar-pressing response in mice (Messier et al., 1991). Interestingly, apamin did not alter performance in rats when administered at different time points in a passive avoidance test, which might indicate that acquisition, consolidation and retention are not enhanced by apamin (Deschaux and Bizot, 1997). In a discrimination avoidance task in young chicks, blocking KCa2 channels with apamin resulted even in persistent impairment of retention during the long-term memory stage, which might indicate that KCa2 channels play a role in long-term memory (Baker et al., 2011). Taken together, these studies indicate that blocking KCa2 channels results in an LTP increase and in learning improvement. In hippocampus-dependent tasks, the effect of blocking KCa2 channels is more evident than in amygdala-dependent tasks.

Blocking of KCa2 channel activity by apamin can also be of interest in alcohol and drug addiction which is associated with long-lasting changes in the activity of neuronal networks. Molecular changes in K+ channel function are linked to an enhancement of drug-seeking behavior. In ex vivo rat neurons from the core nucleus accumbens (NAcb), a reduction in KCa channel currents can significantly enhance spike firing after abstinence from alcohol, but not after sucrose abstinence, and facilitates motivation to seek alcohol following protracted abstinence. Inhibition of KCa channels with apamin produces a greater enhancement of firing in neurons from sucrose- versus alcohol-abstinent animals, indeed indicating reduced KCa currents. Activation of KCa channels in NAcb core neurons with the positive modulator 1-EBIO significantly inhibits firing of neurons ex vivo and reduces alcohol seeking after abstinence in vivo. Apamin can fully reverse the effect of 1-EBIO ex vivo, indicating that 1-EBIO depressed firing through KCa channel activation. Also the positive KCa channel modulator chlorzoxazone can inhibit firing in NAcb core neurons ex vivo and significantly and dose-dependently decrease alcohol intake in rats with intermittent access to alcohol compared to rats with continuous access to alcohol (Hopf et al., 2010, 2011a,b). Chronic exposure to alcohol in vitro and in vivo also reduces hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuronal KCa2 channel function and reduces KCa2 expression with concomitant increases in NMDAR specifically at synaptic sites. Apamin potentiated EPSPs in control but not in ethanol-treated neurons, suggesting disruption of the KCa2-NMDAR feedback loop. Increasing channel activity by 1-EBIO decreased alcohol withdrawal hyperexcitability and attenuated ethanol withdrawal neurotoxicity in hippocampus (Mulholland et al., 2011). Endocannabinoid signaling is potentiated by KCa2 channels resulting in an enhanced AHP current and spike-frequency adaptation, shown by examining the endocannabinoid anandamide in cultured rat hippocampal neurons (Wang et al., 2011). Mice with cannabinoid tolerance, such as observed in drug addiction, show impaired endocannabinoid-induced long-term depression (LTD) and the reversal of LTP in the dorsolateral striatum. In vivo modulation of KCa2 channel activity by apamin can potentiate the endocannabinoid signaling and rescue the deficit in LTD and corresponding behavioral alterations. Striking also is the observation that the KCa channel stimulator NS309 has the reversed effect (Nazzaro et al., 2012). Stimulation of KCa2 channels results in a reduction of LTP and learning in both hippocampus- and amygdala-dependent tasks (Hammond et al., 2006). 1-EBIO facilitates KCa2 channel activation by increasing their sensitivity to Ca2+. Systemic administration of 1-EBIO results in impaired motor and cognitive behavior in mice and facilitates object memory encoding but not retrieval. The compound CyPPA, which can selectively activate KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 channels, has the same effect as 1-EBIO (Vick et al., 2010). Next to activation, overexpression of KCa2.2 channels results in deficits in hippocampal contextual memory encoding and synaptic plasticity. However, KCa2 channels constrain, but do not fully prevent hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Stackman et al., 2008).

With increasing age, memory impairments, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease occur more frequent and substantial changes in neuronal signal processing in the hippocampus are observed. Alterations in Ca2+ signaling might be one of the underlying cause of changes in signal processing (Norris et al., 1998; LaFerla, 2002; Stutzmann, 2005). It was hypothesized that during aging Ca2+ levels may slowly increase, affecting critical Ca2+ signaling throughout cells and affecting cellular activity (Toescu et al., 2004; Shetty et al., 2011). Indeed, in neurons from aged rats, elevated levels of [Ca2+]i can lead to a prolonged Ca2+-dependent K+-mediated AHP, resulting in deleterious effects on neurons (Landfield and Pitler, 1984; Norris et al., 1998). Also an immediate abnormal increase in [Ca2+]i and exacerbated activation of glutamate receptor-coupled Ca2+ channels, like NMDA receptors, are established hallmarks of neuronal cell death in acute and chronic neurological diseases (Dolga et al., 2011). Neurons modulate Ca2+ signals by regulating the influx into the cell from the extracellular environment or by its release from internal sources such as the ER via IP3 receptors and ryanodine receptors in the ER membrane (LaFerla, 2002; Stutzmann, 2005). The regulation of the [Ca2+]i is critical, because insufficient levels of [Ca2+] can lead to impaired functioning whereas excessive cytosolic [Ca2+] levels can cause overstimulation and even cell death (Berridge et al., 1998). Several factors can trigger increases in [Ca2+]i in neurons, like exposure to glutamate, which activates NMDA receptors (Randall and Thayer, 1992; Dolga et al., 2011). In physiological conditions, glutamate receptor-coupled Ca2+ channels are responsible for the primary depolarization in glutamate-mediated neurotransmission and changes in dendritic spine Ca2+ concentration play a key role in initiating synaptic plasticity (Santos et al., 2009; El-Hassar et al., 2011; O’Donnell et al., 2011).

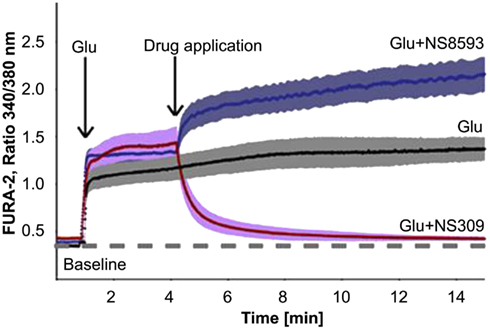

Next to changes in [Ca2+], functional alterations in KCa channels can play a significant role in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in aging and neurodegenerative diseases (LaFerla, 2002). In the hippocampus of aged mice an elevated expression of KCa2.3 channels contributes to an age-related reduction in performance on learning tasks, synaptic plasticity and LTP (Blank et al., 2003). In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), KCa2 channels may significantly contribute to neuroprotection. In MS glutamate receptors are involved in glial activation and pathological changes in axonal processes associated with progressive brain damage. Improvements of symptoms are seen with treatment with riluzole, a neuroprotective agent that inhibits the release of glutamate from nerve terminals, reduces neuronal excitability and activates KCa2 channel activity, indicating a protective role of KCa2 channels (Cao et al., 2002; Geurts et al., 2003; Killestein et al., 2005). Neuroprotection can also be promoted by pharmacological positive modulation of KCa2.2 channels by NS309 in vitro by reducing glutamate- and NMDA-induced delayed Ca2+ deregulation (DCD), which is responsible for apoptotic neuronal death (Figure 3). Glutamate-induced DCD is paralleled by downregulation of KCa2.2 channel expression in a time-dependent manner in primary cortical neurons, which may explain the lack of adaptation to extended glutamate receptor stimulation, and the NS309 therapeutic time window. As shown by Dolga et al. (2011), NS309 mediated neuroprotection only when applied up to 3 h after the onset of [Ca2+]i deregulation, an effect that correlates with the time window of the progressive decline of KCa2.2 channel expression levels upon glutamate damage. These data were substantiated in in vivo stroke studies of middle cerebral artery occlusion and focal ischemia, which cause significant cell loss and reduced KCa2.2 channel activity due to the internalization of synaptic KCa2.2 channels (Allen et al., 2011b). In both studies, pharmacological activation of KCa2 channels with either NS309 or 1-EBIO reduced neuronal death and ischemic brain damage, and restored KCa2.2 channel expression and activity. Thus, the activation of KCa2.2 channels could be used as potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders (Allen et al., 2011b; Dolga et al., 2011).

Figure 3. Effect of a negative modulator (NS8593) and an positive modulator (NS309) of KCa channel activity on the glutamate (Glu)-induced intracellular Ca2+ concentrations of primary cortical neurons, seen as changes in fluorescence intensities of the Ca2+-sensitive dye FURA-2. Single neurons were stimulated with glutamate (20 μM) and then treated with NS309 (50 μM), NS8593 (50 μM; obtained with permission from Dolga et al., 2011).

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD) certain parts of the brain like the hippocampus are especially vulnerable to pathogenic mechanisms. Early degenerative symptoms include significant deficits in the performance of hippocampal-dependent cognitive abilities such as spatial learning and memory (Yamin, 2009). AD has many hallmarks including neuroinflammation and accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and tau pathology (Maezawa et al., 2011). Recent experimental evidence suggests that Aβ oligomers disturb the NMDA receptor-dependent LTP induction in the hippocampal CA1 and DG regions both in vivo and in vitro (Stutzmann, 2005; Yamin, 2009). The disturbance by Aβ and inflammation can lead to a destabilization of Ca2+ signaling, which seems to be central to the pathogenesis of AD (LaFerla, 2002; Santos et al., 2009). However, some forms of Ca2+ dysregulation may represent compensatory mechanisms to modulate neuronal excitability and slow AD pathology in the early stages of the disease (Supnet and Bezprozvanny, 2010). KCa2 channels can provide a negative feedback on Ca2+ signaling through interaction with NMDA receptors, reducing lethal amounts of Ca2+ influx (Allen et al., 2011b).

Recently, KCa3.1 channels have been found to play a role in AD. KCa3.1 channels are present in microglia, which are activated by aggregated forms of Aβ. Aβ oligomers induce a unique pattern of microglia activation that requires the activity of KCa3.1 channels (Maezawa et al., 2011). Suppression of KCa3.1 might be useful for reducing microglia activity in stroke, traumatic brain injury, MS, and Alzheimer’s disease (Chen et al., 2011). In brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid and plasma in AD and in other central nervous system disorders, the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is found to be increased. An increase in TNF-α increases the expression of KCa2.2 channels in cortical neurons (Murthy et al., 2008). TNF-α has been implicated as contributing to both neuroprotection and neurodegeneration, depending on the tissue and experimental paradigm and the increase in KCa2 channels makes neurons more resistant to excitotoxic cell death. In an in vitro model of glutamate-induced cell death of primary cortical neurons, TNF-α was shown to have neuroprotective properties. By blocking KCa2 channels with apamin, the neuroprotective effect of TNF-α against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity was blocked (Dolga et al., 2008). In addition to this results, in cortical tissue from AD patients a significantly higher expression level of a short, inactive form of KCa2.2 mRNA has been found which impairs the negative feedback of KCa2.2 channels on Ca2+ signaling and probably also had a negative effect on the neuroprotective effect of TNF-α (Murthy et al., 2008). Also in mice with KCa2.2-S-containing channels, the channels were excluded from the PSD and EPSPs or LTP were not increased by adding apamin (Allen et al., 2011a). In contrast to this result, in mice with partial hippocampal-lesions, mimicking the pathophysiological hallmark also observed in AD, blocking KCa2 channels by apamin could alleviate the impairment in spatial reference memory and working memory (Ikonen and Riekkinen, 1999). Due to these findings, apamin has been proposed as a therapeutic agent in AD treatment (Romero-Curiel et al., 2011). It is of interest to determine whether KCa2.2 channel protein expression increases with age and whether blocking KCa2.2 channels can limit age-related memory impairment (Stackman et al., 2008).

Three decades of research on KCa channels has revealed a broad range of processes in which these channels are critically involved. The apamin-sensitive KCa2 channels contribute to the AHP and are crucial regulators of neuronal excitability. Several compounds affecting these channels have been synthesized and tested in models for neurological diseases in vitro as well as in vivo. Some of these features are summarized in Table 1. In the nearer future, treatment of neurodegenerative diseases caused by neuronal hyperexcitability, progressive disturbance of Ca2+ homeostasis and excitotoxic neuronal death might benefit from enhancers of KCa2 channel activity, whereas, although less clear, deficiencies in learning and memory might benefit from inhibition of these channels.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adelman, J. P., Maylie, J., and Sah, P. (2012). Small-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels: form and function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 245–269.

Allen, D., Bond, C. T., Lujan, R., Ballesteros-Merino, C., Lin, M. T., Wang, K., Klett, N., Watanabe, M., Shigemoto, R., Stackman, R. W. Jr., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (2011a). The SK2-long isoform directs synaptic localization and function of SK2-containing channels. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 744–749.

Allen, D., Nakayama, S., Kuroiwa, M., Nakano, T., Palmateer, J., Kosaka, Y., Ballesteros, C., Watanabe, M., Bond, C. T., Luján, R., Maylie, J., Adelman, J. P., and Herson, P. S. (2011b). SK2 channels are neuroprotective for ischemia-induced neuronal cell death. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 2302–2312.

Allen, D., Fakler, B., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (2007). Organization and regulation of small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel multiprotein complexes. J. Neurosci. 27, 2369–2376.

Baker, K. D., Edwards, T. M., and Rickard, N. S. (2011). Blocking SK channels impairs long-term memory formation in young chicks. Behav. Brain Res. 216, 458–462.

Banks, B. E., Brown, C., Burgess, G. M., Burnstock, G., Claret, M., Cocks, T. M., and Jenkinson, D. H. (1979). Apamin blocks certain neurotransmitter-induced increases in potassium permeability. Nature 282, 415–417.

Behnisch, T., and Reymann, K. G. (1998). Inhibition of apamin-sensitive calcium dependent potassium channels facilitate the induction of long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 253, 91–94.

Benton, D. C., Monaghan, A. S., Hosseini, R., Bahia, P. K., Haylett, D. G., and Moss, G. W. (2003). Small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels formed by the expression of rat SK1 and SK2 genes in HEK 293 cells. J. Physiol. 553, 13–19.

Berridge, M. J., Bootman, M. D., and Lipp, P. (1998). Calcium – a life and death signal. Nature 395, 645–648.

Blank, T., Nijholt, I., Kye, M. J., Radulovic, J., and Spiess, J. (2003). Small-conductance, Ca2+ activated K+ channel SK3 generates age-related memory and LTP deficits. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 911–912.

Blatz, A. L., and Magleby, K. L. (1986). Single apamin-blocked Ca-activated K+ channels of small conductance in cultured rat skeletal muscle. Nature 323, 718–720.

Bliss, T., and Collingridge, G. (1993). A synaptic model of memory-long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361, 31–39.

Boettger, M. K., Till, S., Chen, M. X., Anand, U., Otto, W. R., Plumpton, C., Trezise, D. J., Tate, S. N., Bountra, C., Coward, K., Birch, R., and Anand, P. (2002). Calcium-activated potassium channel SK1- and IK1-like immunoreactivity in injured human sensory neurones and its regulation by neurotrophic factors. Brain 125, 252–263.

Bond, C. T., Herson, P. S., Strassmaier, T., Hammond, R., Stackman, R., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (2004). Small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel knock-out mice reveal the identity of calcium-dependent after hyperpolarization currents. J. Neurosci. 24, 5301–5306.

Borght van der, K., Wallinga, A. E., Luiten, P. G. M., Eggen, B. J. L., and Zee van der, E. A. (2005). Morris water maze learning in two rat strains increases the expression of the polysialylated form of the neural cell adhesion molecule in the dentate gyrus but has no effect on hippocampal neurogenesis. Behav. Neurosci. 119, 926–932.

Brøndum, E., Kold-Petersen, H., Simonsen, U., and Aalkjaer, C. (2010). NS309 restores EDHF-type relaxation in mesenteric small arteries from type 2 diabetic ZDF rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 154–165.

Brugnara, C., Gee, B., Armsby, C. C., Kurth, S., Sakamoto, M., Rifai, N., Alper, S. L., and Platt, O. S. (1996). Therapy with oral clotrimazole induces inhibition of the Gardos channel and reduction of erythrocyte dehydration in patients with sickle cell disease. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 1227–1234.

Cao, Y.-J., Dreixler, J. C., Couey, J. J., and Houamed, K. M. (2002). Modulation of recombinant and native neuronal SK channels by the neuroprotective drug riluzole. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 449, 47–54.

Chandy, K. G., Wulff, H., Beeton, C., Pennington, M., Gutman, G. A., and Cahalan, M. D. (2004). K+ channels as targets for specific immunomodulation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 280–289.

Chen, M. X., Gorman, S. A., Benson, B., Singh, K., Hieble, J. P., Michel, M. C., Tate, S. N., and Trezise, D. J. (2004). Small and intermediate conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels confer distinctive patterns of distribution in human tissues and differential cellular localisation in the colon and corpus cavernosum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 369, 602–615.

Chen, Y.-J., Raman, G., Bodendiek, S., O’Donnell, M. E., and Wulff, H. (2011). The KCa3.1 blocker TRAM-34 reduces infarction and neurological deficit in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 2363–2374.

Cipolla, M. J., Smith, J., Kohlmeyer, M. M., and Godfrey, J. A. (2009). SKCa and IKCa channels, myogenic tone, and vasodilator responses in middle cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles: effect of ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke 40, 1451–1457.

Dalsgaard, T., Kroigaard, C., Bek, T., and Simonsen, U. (2009). Role of calcium-activated potassium channels with small conductance in bradykinin-induced vasodilation of porcine retinal arterioles. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 3819–3825.

Dalsgaard, T., Kroigaard, C., Misfeldt, M., Bek, T., and Simonsen, U. (2010). Openers of small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels selectively enhance NO-mediated bradykinin vasodilatation in porcine retinal arterioles. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 1496–1508.

Damkjaer, M., Nielsen, G., Bodendiek, S., Staehr, M., Gramsbergen, J.-B., de Wit, C., Jensen, B. L., Simonsen, U., Bie, P., Wulff, H., and Köhler, R. (2012). Pharmacological activation of KCa3.1/KCa2.3 channels produces endothelial hyperpolarisation and lowers blood pressure in conscious dogs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 223–234.

Debanne, D., Daoudal, G., Sourdet, V., and Russier, M. (2004). Brain plasticity and ion channels. J. Physiol. 97, 403–414.

Den Hertog, A. (1981). Calcium and the alpha-action of catecholamines on guinea-pig taenia caeci. J. Physiol. 316, 109–125.

Den Hertog, A. (1982). Calcium and the action of adrenaline, adenosine triphosphate and carbachol on guinea-pig taenia caeci. J. Physiol. 325, 423–439.

Deschaux, O., and Bizot, J. C. (1997). Effect of apamin, a selective blocker of Ca2+ activated K+-channel, on habituation and passive avoidance responses in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 227, 57–60.

Deschaux, O., Bizot, J. C., and Goyffon, M. (1997). Apamin improves learning in an object recognition task in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 222, 159–162.

D’Hoedt, D., Hirzel, K., Pedarzani, P., and Stocker, M. (2004). Domain analysis of the calcium-activated potassium channel SK1 from rat brain. Functional expression and toxin sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12088–12092.

Diness, J. G., Skibsbye, L., Jespersen, T., Bartels, E. D., Sørensen, U. S., Hansen, R. S., and Grunnet, M. (2011). Effects on atrial fibrillation in aged hypertensive rats by Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel inhibition. Hypertension 57, 1129–1135.

Diness, J. G., Sorensen, U. S., Nissen, J. D., Al-Shahib, B., Jespersen, T., Grunnet, M., and Hansen, R. S. (2010). Inhibition of small-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels terminates and protects against atrial fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 3, 380–390.

Ding, H., Hashem, M., Wiehler, W. B., Lau, W., Martin, J., Reid, J., and Triggle, C. (2005). Endothelial dysfunction in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic apoE-deficient mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. 146, 1110–1118.

Dolga, A. M., Granic, I., Blank, T., Knaus, H. G., Spiess, J., Luiten, P. G., Eisel, U. L., and Nijholt, I. M. (2008). TNF-alpha-mediates neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity via NF-kappaB-dependent up-regulation of K2.2 channels. J. Neurochem. 107, 1158–1167.

Dolga, A. M., Terpolilli, N., Kepura, F., Nijholt, I. M., Knaus, H. G., D’Orsi, B., Prehn, J. H., Eisel, U. L., Plant, T., Plesnila, N., and Culmsee, C. (2011). KCa2 channels activation prevents [Ca2+]i deregulation and reduces neuronal death following glutamate toxicity and cerebral ischemia. Cell Death Dis. 2, e147.

Edwards, G., Félétou, M., and Weston, A. H. (2010). Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors and associated pathways: a synopsis. Pflugers Arch. 459, 863–879.

Eichler, I., Wibawa, J., Grgic, I., Knorr, A., Brakemeier, S., Pries, A. R., Hoyer, J., and Köhler, R. (2003). Selective blockade of endothelial Ca2+-activated small- and intermediate-conductance K+-channels suppresses EDHF-mediated vasodilation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 138, 594–601.

El-Hassar, L., Hagenston, A. M., Bertetto, D. L., and Yeckel, M. (2011). MGluRs regulate hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron excitability via Ca2+ wave-dependent activation of SK and TRPC channels. J. Physiol. 589, 3211–3229.

Faber, E. S. (2009). Functions and modulation of neuronal SK channels. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 55, 127–139.

Faber, E. S. L., Delaney, A. J., and Sah, P. (2005). SK channels regulate excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity in the lateral amygdala. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 635–641.

Faber, E. S. L., and Sah, P. (2007). Functions of SK channels in central neurons. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 34, 1077–1083.

Fanger, C. M., Rauer, H., Neben, A. L., Miller, M. J., Wulff, H., Rosa, J. C., Ganellin, C. R., Chandy, K. G., and Cahalan, M. D. (2001). Calcium-activated potassium channels sustain calcium signaling in T lymphocytes. Selective blockers and manipulated channel expression levels. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12249–12256.

Faraci, F. M., Lynch, C., and Lamping, K. G. (2004). Responses of cerebral arterioles to ADP: eNOS-dependent and eNOS-independent mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H2871–H2876.

Félétou, M., and Vanhoutte, P. M. (2007). Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations: past beliefs and present facts. Ann. Med. 39, 495–516.

Feng, J., Liu, Y., Clements, R. T., Sodha, N. R., Khabbaz, K. R., Senthilnathan, V., Nishimura, K. K., Alper, S. L., and Sellke, F. W. (2008). Calcium-activated potassium channels contribute to human coronary microvascular dysfunction after cardioplegic arrest. Circulation 118, S46–S51.

Fujita, A., Takeuchi, T., Saitoh, N., Hanai, J., and Hata, F. (2001). Expression of Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels, SK3, in the interstitial cells of Cajal in the gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C1727–C1733.

Gardos, G. (1958). The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 30, 653–654.

Geinisman, Y., Berry, R. W., Disterhoft, J. F., Power, J. M., and Van der Zee, E. A. (2001). Associative learning elicits the formation of multiple-synapse boutons. J. Neurosci. 21, 5568–5573.

Geurts, J. J. G., Wolswijk, G., Bö, L., van der Valk, P., Polman, C. H., Troost, D., and Aronica, E. (2003). Altered expression patterns of group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptors in multiple sclerosis. Brain 126, 1755–1766.

Ghanshani, S., Wulff, H., Miller, M. J., Rohm, H., Neben, A., Gutman, G. A., Cahalan, M. D., and Chandy, K. G. (2000). Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation. Molecular mechanism and functional consequences. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37137–37149.

Ghosh, A., and Greenberg, M. E. (1995). Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science 268, 239–247.

Grgic, I., Eichler, I., Heinau, P., Si, H., Brakemeier, S., Hoyer, J., and Köhler, R. (2005). Selective blockade of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel suppresses proliferation of microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells and angiogenesis in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 704–709.

Gschwend, S., Henning, R. H., de Zeeuw, D., and Buikema, H. (2003). Coronary myogenic constriction antagonizes EDHF-mediated dilation: role of KCa channels. Hypertension 41, 912–918.

Haddock, R. E., Grayson, T. H., Morris, M. J., Howitt, L., Chadha, P. S., and Sandow, S. L. (2011). Diet-induced obesity impairs endothelium-derived hyperpolarization via altered potassium channel signaling mechanisms. PLoS ONE 6, e16423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016423

Hammond, R. S., Bond, C. T., Strassmaier, T., Ngo-Anh, T. J., Adelman, J. P., Maylie, J., and Stackman, R. W. (2006). Small-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel type 2 (SK2) modulates hippocampal learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 26, 1844–1853.

Hannah, R. M., Dunn, K. M., Bonev, A. D., and Nelson, M. T. (2011). Endothelial SK(Ca) and IK(Ca) channels regulate brain parenchymal arteriolar diameter and cortical cerebral blood flow. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1175–1186.

Havekes, R., Nijholt, I. M., Luiten, P. G. M., and Van der Zee, E. A. (2006). Differential involvement of hippocampal calcineurin during learning and reversal learning in a Y-maze task. Learn. Mem. 13, 753–759.

Hilgers, R. H., Janssen, G. M., Fazzi, G. E., and De Mey, J. G. (2010). Twenty-four-hour exposure to altered blood flow modifies endothelial Ca2+ activated K+ channels in rat mesenteric arteries. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333, 210–217.

Hopf, F. W., Bowers, M. S., Chang, S. J., Chen, B. T., Martin, M., Seif, T., Cho, S. L., Tye, K., and Bonci, A. (2010). Reduced nucleus accumbens SK channel activity enhances alcohol seeking during abstinence. Neuron 65, 682–694.

Hopf, F. W., Seif, T., and Bonci, A. (2011a). The SK channel as a novel target for treating alcohol use disorders. Channels (Austin) 5, 289–292.

Hopf, F. W., Simms, J. A., Chang, S. J., Seif, T., Bartlett, S. E., and Bonci, A. (2011b). Chlorzoxazone, an SK-type potassium channel activator used in humans, reduces excessive alcohol intake in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 69, 618–624.

Hosseini, R., Benton, D. C., Dunn, P. M., Jenkinson, D. H., and Moss, G. W. (2001). SK3 is an important component of K(+) channels mediating the afterhyperpolarization in cultured rat SCG neurones. J. Physiol. 535, 323–334.

Hougaard, C., Eriksen, B. L., Jørgensen, S., Johansen, T. H., Dyhring, T., Madsen, L. S., Strøbaek, D., and Christophersen, P. (2007). Selective positive modulation of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes of small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151, 655–665.

Hugues, M., Romey, G., Duval, D., Vincent, J. P., and Lazdunski, M. (1982). Apamin as a selective blocker of the calcium-dependent potassium channel in neuroblastoma cells: voltage-clamp and biochemical characterization of the toxin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 1308–1312.

Ikonen, S., and Riekkinen, P. (1999). Effects of apamin on memory processing of hippocampal-lesioned mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 382, 151–156.

Ishii, T. M., Silvia, C., Hirschberg, B., Bond, C. T., Adelman, J. P., and Maylie, J. (1997). A human intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11651–11656.

Jacobsen, J. P., Redrobe, J. P., Hansen, H. H., Petersen, S., Bond, C. T., Adelman, J. P., Mikkelsen, J. D., and Mirza, N. R. (2009). Selective cognitive deficits and reduced hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA expression in small-conductance calcium-activated K+ channel deficient mice. Neuroscience 163, 73–81.

Jensen, B. S., Odum, N., Jorgensen, N. K., Christophersen, P., and Olesen, S. P. (1999). Inhibition of T cell proliferation by selective block of Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10917–10921.

Jensen, B. S., Strøbæk, D., Christophersen, P., Jørgensen, T. D., Hansen, C., Silahtaroglu, A., Olesen, S. P., Ahring, P. K., Physiol, A. J., and Liver, G. (1998). Characterization of the cloned human intermediate-conductance Ca 2+-activated K+ channel. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol. 275, C848–C856.

Joiner, W. J. (1997). hSK4, a member of a novel subfamily of calcium-activated potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11013–11018.

Kaushal, V., Koeberle, P. D., Wang, Y., and Schlichter, L. C. (2007). The Ca2+ activated K+ channel KCNN4/KCa3.1 contributes to microglia activation and nitric oxide-dependent neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 27, 234–244.

Khanna, R., Roy, L., Zhu, X., and Schlichter, L. C. (2001). K+ channels and the microglial respiratory burst. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C796–C806.

Killestein, J., Kalkers, N. F., and Polman, C. H. (2005). Glutamate inhibition in MS: the neuroprotective properties of riluzole. J. Neurol. Sci. 233, 113–115.

Köhler, M., Hirschberg, B., Bond, C. T., Kinzie, J. M., Marrion, N. V., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (1996). Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science 273, 1709–1714.

Köhler, R., Wulff, H., Eichler, I., Kneifel, M., Neumann, D., Knorr, A., Grgic, I., Kämpfe, D., Si, H., Wibawa, J., Real, R., Borner, K., Brakemeier, S., Orzechowski, H. D., Reusch, H. P., Paul, M., Chandy, K. G., and Hoyer, J. (2003). Blockade of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel as a new therapeutic strategy for restenosis. Circulation 108, 1119–1125.

LaFerla, F. M. (2002). Calcium dyshomeostasis and intracellular signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 862–872.

Lamy, C., Goodchild, S. J., Weatherall, K. L., Jane, D. E., Liegeois, J. F., Seutin, V., and Marrion, N. V. (2010). Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by apamin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27067–27077.

Landfield, P., and Pitler, T. (1984). Prolonged Ca2+ dependent afterhyperpolarizations in hippocampal neurons of aged rats. Science 226, 1089–1092.

Lappin, S. C., Dale, T. J., Brown, J. T., Trezise, D. J., and Davies, C. H. (2005). Activation of SK channels inhibits epileptiform bursting in hippocampal CA3 neurons. Brain Res. 1065, 37–46.

Leuranguer, V., Gluais, P., Vanhoutte, P. M., Verbeuren, T. J., and Félétou, M. (2008). Openers of calcium-activated potassium channels and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations in the guinea pig carotid artery. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 377, 101–109.

Lin, M. T., Luján, R., Watanabe, M., Adelman, J. P., and Maylie, J. (2008). SK2 channel plasticity contributes to LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 170–177.

Longden, T., Dunn, K., Draheim, H., Nelson, M., Weston, A., and Edwards, G. (2011). Intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels participate in neurovascular coupling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 164, 922–933.

Maas, A. J., Den, H. A., Ras, R., and Van den Akker, J. (1980). The action of apamin on guinea-pig taenia caeci. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 67, 265–274.

Maas, A. J., and Den Hertog, A. (1979). The effect of apamin on the smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig taenia coli. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 58, 151–156.

Maezawa, I., Zimin, P. I., Wulff, H., and Jin, L. W. (2011). Amyloid-beta protein oligomer at low nanomolar concentrations activates microglia and induces microglial neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 3693–3706.

Marrelli, S. P., Eckmann, M. S., and Hunte, M. S. (2003). Role of endothelial intermediate conductance KCa channels in cerebral EDHF-mediated dilations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 285, H1590–H1599.

Matsumoto, T., Ishida, K., Taguchi, K., Kobayashi, T., and Kamata, K. (2010). Losartan normalizes endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated relaxation by activating Ca2+ activated K+ channels in mesenteric artery from type 2 diabetic GK rat. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 112, 299–309.

McNeish, A. J., Dora, K. A., and Garland, C. J. (2005). Possible role for K+ in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-linked dilatation in rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke 36, 1526–1532.

McNeish, A. J., Sandow, S. L., Neylon, C. B., Chen, M. X., Dora, K. A., and Garland, C. J. (2006). Evidence for involvement of both IKCa and SKCa channels in hyperpolarizing responses of the rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke 37, 1277–1282.

Messier, C., Mourre, C., Bontempi, B., Sif, J., Lazdunski, M., and Destrade, C. (1991). Effect of apamin, a toxin that inhibits Ca(2+)-dependent K+ channels, on learning and memory processes. Brain Res. 551, 322–326.

Mongan, L. C., Hill, M. J., Chen, M. X., Tate, S. N., Collins, S. D., Buckby, L., and Grubb, B. D. (2005). The distribution of small and intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in the rat sensory nervous system. Neuroscience 131, 161–175.

Morgado-Bernal, I. (2011). Learning and memory consolidation: linking molecular and behavioral data. Neuroscience 176, 12–19.

Morikawa, K., Matoba, T., Kubota, H., Hatanaka, M., Fujiki, T., Takahashi, S., Takeshita, A., and Shimokawa, H. (2005). Influence of diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and their combination on EDHF-mediated responses in mice. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 45, 485–490.

Mpari, B., Sreng, L., Manrique, C., and Mourre, C. (2010). KCa2 channels transiently downregulated during spatial learning and memory in rats. Hippocampus 20, 352–363.

Mulholland, P. J., Becker, H. C., Woodward, J. J., and Chandler, L. J. (2011). Small conductance calcium-activated potassium type 2 channels regulate alcohol-associated plasticity of glutamatergic synapses. Biol. Psychiatry 69, 625–632.

Murthy, S. R., Teodorescu, G., Nijholt, I. M., Dolga, A. M., Grissmer, S., Spiess, J., and Blank, T. (2008). Identification and characterization of a novel, shorter isoform of the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel SK2. J. Neurochem. 106, 2312–2321.

Nazzaro, C., Greco, B., Cerovic, M., Baxter, P., Rubino, T., Trusel, M., Parolaro, D., Tkatch, T., Benfenati, F., Pedarzani, P., and Tonini, R. (2012). SK channel modulation rescues striatal plasticity and control over habit in cannabinoid tolerance. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 284–293.

Ngo-Anh, T. J., Bloodgood, B. L., Lin, M., Sabatini, B. L., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (2005). SK channels and NMDA receptors form a Ca2+ mediated feedback loop in dendritic spines. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 642–649.

Nolting, A., Ferraro, T., D’Hoedt, D., and Stocker, M. (2007). An amino acid outside the pore region influences apamin sensitivity in small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3478–3486.

Norris, C. M., Halpain, S., and Foster, T. C. (1998). Reversal of age-related alterations in synaptic plasticity by blockade of L-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 18, 3171–3179.

O’Donnell, C., Nolan, M. F., and van Rossum, M. C. W. (2011). Dendritic spine dynamics regulate the long-term stability of synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 31, 16142–16156.

Pedarzani, P., and Stocker, M. (2008). Molecular and cellular basis of small – and intermediate-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel function in the brain. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3196–3217.

Randall, R. D., and Thayer, S. A. (1992). Glutamate-induced calcium transient triggers delayed calcium overload and neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 12, 1882–1895.

Ren, Y., Barnwell, L. F., Alexander, J. C., Lubin, F. D., Adelman, J. P., Pfaffinger, P. J., Schrader, L. A., and Anderson, A. E. (2006). Regulation of surface localization of the small conductance Ca2+ activated potassium channel, Sk2, through direct phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11769–11779.

Rimini, R., Rimland, J. M., and Terstappen, G. C. (2000). Quantitative expression analysis of the small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, SK1, SK2 and SK3, in human brain. Mol. Brain Res. 85, 218–220.

Ro, S., Hatton, W. J., Koh, S. D., and Horowitz, B. (2001). Molecular properties of small-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels expressed in murine colonic smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 281, G964–G973.

Romero-Curiel, A., López-Carpinteyro, D., Gamboa, C., De la Cruz, F., Zamudio, S., and Flores, G. (2011). Apamin induces plastic changes in hippocampal neurons in senile Sprague-Dawley rats. Synapse 65, 1062–1072.

Sailer, C. A., Hu, H., Kaufmann, W. A., Trieb, M., Schwarzer, C., Storm, J. F., and Knaus, H.-G. (2002). Regional differences in distribution and functional expression of small-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 22, 9698–9707.

Sailer, C. A., Kaufmann, W. A., Marksteiner, J., and Knaus, H. G. (2004). Comparative immunohistochemical distribution of three small-conductance Ca2+ activated potassium channel subunits, SK1, SK2, and SK3 in mouse brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26, 458–469.

Sankaranarayanan, A., Raman, G., Busch, C., Schultz, T., Zimin, P. I., Hoyer, J., Kohler, R., and Wulff, H. (2009). Naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-31), a new activator of KCa2 and KCa3.1 potassium channels, potentiates the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor response and lowers blood pressure. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 281–295.

Santos, S. F., Pierrot, N., Morel, N., Gailly, P., Sindic, C., and Octave, J.-N. (2009). Expression of human amyloid precursor protein in rat cortical neurons inhibits calcium oscillations. J. Neurosci. 29, 4708–4718.

Schilling, T., Repp, H., Richter, H., Koschinski, A., Heinemann, U., Dreyer, F., and Eder, C. (2002). Lysophospholipids induce membrane hyperpolarization in microglia by activation of IKCa1 Ca(2+)-dependent K(+) channels. Neuroscience 109, 827–835.

Schumacher, M. A., Rivard, A. F., Bächinger, H. P., and Adelman, J. P. (2001). Structure of the gating domain of a Ca2+ activated K+ channel complexed with Ca2+/calmodulin. Nature 410, 1120–1124.

Shah, M., and Haylett, D. G. (2000). The pharmacology of hSK1 Ca2+-activated K+ channels expressed in mammalian cell lines SPECIAL REPORT. Br. J. Pharmacol. 129, 627–630.

Shakkottai, V. G., Chou, C. H., Oddo, S., Sailer, C. A., Knaus, H. G., Gutman, G. A., Barish, M. E., LaFerla, F. M., and Chandy, K. G. (2004). Enhanced neuronal excitability in the absence of neurodegeneration induces cerebellar ataxia. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 582–590.

Shetty, P. K., Galeffi, F., and Turner, D. A. (2011). Age-induced alterations in hippocampal function and metabolism. Aging Dis. 2, 196–218.

Shuba, M., and Vladimirova, I. (1980). Effect of apamin on the electrical responses of smooth muscle to adenosine 5’-triphosphate and to non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic nerve stimulation. Neuroscience 5, 853–859.

Stackman, R. W., Bond, C. T., and Adelman, J. P. (2008). Contextual memory deficits observed in mice overexpressing small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ type 2 (KCa2.2, SK2) channels are caused by an encoding deficit. Learn. Mem. 15, 208–213.

Stackman, R. W., Hammond, R. S., Linardatos, E., Gerlach, A., Maylie, J., Adelman, J. P., and Tzounopoulos, T. (2002). Small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channels modulate synaptic plasticity and memory encoding. J. Neurosci. 22, 10163–10171.

Stocker, M., and Pedarzani, P. (2000). Differential distribution of three Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel subunits, SK1, SK2, and SK3, in the adult rat central nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 476–493.

Strassmaier, T., Bond, C. T., Sailer, C. A., Knaus, H. G., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (2005). A novel isoform of SK2 assembles with other SK subunits in mouse brain. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21231–21236.

Strobaek, D., Jorgensen, T. D., Christophersen, P., Ahring, P. K., and Olesen, S. P. (2000). Pharmacological characterization of small-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels stably expressed in HEK 293 cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 129, 991–999.

Strobaek, D., Teuber, L., Jorgensen, T. D., Ahring, P. K., Kjaer, K., Hansen, R. S., Olesen, S. P., Christophersen, P., and Skaaning-Jensen, B. (2004). Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1665, 1–5.

Stutzmann, G. E. (2005). Calcium dysregulation, IP3 signaling, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscientist 11, 110–115.

Supnet, C., and Bezprozvanny, I. (2010). The dysregulation of intracellular calcium in Alzheimer disease. Cell Calcium 47, 183–189.

Tacconi, S., Carletti, R., Bunnemann, B., Plumpton, C., Pich, E. M., and Terstappen, G. C. (2001). Distribution of the messenger RNA for the small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel SK3 in the adult rat brain and correlation with immunoreactivity. Neuroscience 102, 209–215.

Taylor, S., and Weston, A. (1988). Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: a new endogenous inhibitor from the vascular endothelium. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 9, 272–274.

Toescu, E. C., Verkhratsky, A., and Landfield, P. W. (2004). Ca2+ regulation and gene expression in normal brain aging. Trends Neurosci. 27, 614–620.

Vandorpe, D. H., Shmukler, B. E., Jiang, L., Lim, B., Maylie, J., Adelman, J. P., de Franceschi, L., Cappellini, M. D., Brugnara, C., and Alper, S. L. (1998). cDNA cloning and functional characterization of the mouse Ca2+-gated K+ channel, mIK1. Roles in regulatory volume decrease and erythroid differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21542–21553.

Vick, K. A., Guidi, M., and Stackman, R. W. Jr. (2010). In vivo pharmacological manipulation of small conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels influences motor behavior, object memory and fear conditioning. Neuropharmacology 58, 650–659.

Visan, V., Sabatier, J.-M., and Grissmer, S. (2004). Block of maurotoxin and charybdotoxin on human intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (hIKCa1). Toxicon 43, 973–980.

Wang, W., Zhang, K., Yan, S., Li, A., Hu, X., Zhang, L., and Liu, C. (2011). Enhancement of apamin-sensitive medium after hyperpolarization current by anandamide and its role in excitability control in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuropharmacology 60, 901–909.

Wang, Y., Zhang, G., Zhou, H., Barakat, A., and Querfurth, H. (2009). Opposite effects of low and high doses of Abeta42 on electrical network and neuronal excitability in the rat prefrontal cortex. PLoS ONE 4, e8366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008366

Weatherall, K. L., Goodchild, S. J., Jane, D. E., and Marrion, N. V. (2010). Small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels: from structure to function. Prog. Neurobiol. 91, 242–255.

Weatherall, K. L., Seutin, V., Liégeois, J.-F., and Marrion, N. V. (2011). Crucial role of a shared extracellular loop in apamin sensitivity and maintenance of pore shape of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18494–18499.

Wei, A. D., Gutman, G. A., Aldrich, R., Chandy, K. G., Grissmer, S., and Wulff, H. (2005). International union of pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 463–472.

Weston, A., Richards, G., Burnham, M., Feletou, M., Vanhoutte, P., and Edwards, G. (2002). K+-induced hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery: identification, localization and role of Na+/K+-ATPases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 136, 918–926.

Wulff, H., and Zhorov, B. S. (2008). K+ channel modulators for the treatment of neurological disorders and autoimmune diseases. Chem. Rev. 108, 1744–1773.

Xia, X. M., Fakler, B., Rivard, A., Wayman, G., Johnson-Pais, T., Keen, J. E., Ishii, T., Hirschberg, B., Bond, C. T., Lutsenko, S., Maylie, J., and Adelman, J. P. (1998). Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 395, 503–507.

Yamazaki, D., Aoyama, M., Ohya, S., Muraki, K., Asai, K., and Imaizumi, Y. (2006). Novel functions of small conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel in enhanced cell proliferation by ATP in brain endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38430–38439.

Yamin, G. (2009). NMDA receptor-dependent signaling pathways that underlie amyloid beta-protein disruption of LTP in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 1729–1736.

Keywords: small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, SK channels, learning and memory, neurodegeneration

Citation: Kuiper EFE, Nelemans A Luiten P Nijholt I Dolga A and Eisel U (2012) KCa2 and KCa3 channels in learning and memory processes, and neurodegeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 3:107. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00107

Received: 09 March 2012; Paper pending published: 11 April 2012;

Accepted: 19 May 2012; Published online: 11 June 2012.

Edited by:

Nick Andrews, Pfizer, UKReviewed by:

Alasdair Gibb, University College London, UKCopyright: © 2012 Kuiper, Nelemans, Luiten, Nijholt, Dolga and Eisel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Ad Nelemans, Department of Molecular Neurobiology, University of Groningen, Antonius Deusinglaan 1, 9713 AV Groningen, Netherlands. e-mail:cy5hLm5lbGVtYW5zQHJ1Zy5ubA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.