- 1Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, and Intermediate Care Unit, Emergency Department, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy

- 2Department of Neurosciences, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics and Maternal and Child Health (DINOGMI), University of Genova, Genova, Italy

- 3Pediatric Infectious Diseases Unit, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy

- 4Centre of Translational and Experimental Myology, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy

- 5Pediatric Neurology and Muscular Diseases Unit, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genova, Italy

- 6Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy

Background: Neuromuscular disorders (NMDs) represent a complex group requiring specialized care, often straddling the needs between general pediatric wards and Intensive Care Units (ICUs). Our research focuses on the role of a newly established pediatric Intermediate Care Unit (IMCU) in this context.

Methods: We conducted a single-center retrospective observational study, encompassing patients with NMDs admitted to the newly established pediatric IMCU at IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, from January 2021 to June 2023. The study assessed demographics, clinical characteristics, therapeutic management, length of stay, and outcomes including mortality 28 days post-discharge.

Results: Sixty-three patients (median age 12, female 58.7%) were included. The majority of admissions were due to neurological issues (39.7%) and respiratory complications (22%), with a significant proportion of patients requiring initiation or potentiation of respiratory support (59%). Factors such as the presence of tracheostomy (p = 0.021), the need for antibiotics (p = 0.025), and parenteral nutrition (p = 0.026) were associated with ICU admissions while steroid treatment (p = 0.047) increased IMCU stay.

Conclusions: The establishment of the IMCU has shown promising results in managing NMDs patients, serving as a crucial step-down unit for ICU patients and a step-up unit for those with worsening conditions in low-intensity care units. It has led to decreased ICU admissions and shorter ICU stays, suggesting potential healthcare costs and patient comfort benefits. The study underscores the importance of pediatric IMCUs in providing specialized care for children with NMDs, balancing the need for intensive monitoring and treatment in a less intensive setting than an ICU.

Introduction

Neuromuscular disorders (NMDs) are a genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by the predominant involvement of the neuromuscular unit including the second motor neuron, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle fiber (1, 2). They comprise acute disorders such as Guillain-Barre syndrome and infant botulism, acute-on-chronic disorders such as myasthenia gravis and periodic paralysis, and progressive disorders such as inherited myopathies and neuropathies, and muscular dystrophies (3). Given their progressive nature, NMDs not only impair motor function but also significantly reduce life expectancy and quality of life, underscoring the critical need for effective management strategies. Although each NMD is a rare or orphan disease, NMDs collectively form a significant bulk of patients with challenging chronic needs, requiring specialized medical care, high levels of healthcare utilization, and substantial care costs (4).

Retrieving reliable data on the epidemiology of NMDs is a complicated challenge and what is found is often incomplete. This is probably due to the rarity and the extensive variability of these disorders, as well as the lack of a univocal classification. Recent analyses have estimated that about 0.2% of the population in Italy is affected by NMDs, amounting to at least 100,000–120,000 individuals (5, 6).

Recent decades have witnessed transformative progress in pediatric NMDs care. Enhanced management techniques and novel therapeutic approaches have not only improved survival rates but also begun to reshape the disease trajectory, widening the range of complications and affections that may determine access to health care. Indeed, although NMDs are reported as an uncommon cause of Emergency Department (ED) admission (1), patients with NMD have a significant risk of developing a range of common conditions (e.g., respiratory infections, heart failure, urgent surgical procedures, bone fractures), which require acute hospitalization and often Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission (7–9). However, in many cases, ICU admission is determined solely by the need for advanced clinical monitoring, by the complexity of therapies and devices (non-invasive ventilation, assisted cough, tracheostomy, gastrostomy etc.), or even because of the concern related to the fragility of the underlying condition that predisposes the patient to significant complications. This may lead to inappropriate hospitalizations, unnecessary costs, wasted resources, ICU overcrowding, and a significant psychological impact on patients and families (10–13). Conversely, the complex care and strict monitoring needed by these patients could be excessive for ordinary wards and require specialized settings with appropriate resources and an adequately trained medical and nursing staff.

To address this nuanced care requirement, Pediatric Intermediate Care Units (IMCU) emerged as a vital bridge in care delivery, filling the gap between intensive and general pediatric care (14).

Although the advances in pediatric medical and surgical care have resulted in increased survival of children with complex chronic diseases potentially requiring admission to pediatric IMCU, this concept is still poorly addressed. Studies in adults suggest that IMCU may also improve patient flow and general patient outcomes, and decrease costs and ICU workload, but the evidence is sparse and challenging to interpret (15–18). Furthermore, research evaluating pediatric IMCUs is even more limited (19). Few studies have evaluated the management and outcome of children with NMDs in ICU (7, 9, 11) and there is currently no study focusing on the management of these patients in a pediatric IMCU setting.

Our study aims to fill the critical gap in pediatric NMD care by evaluating the role and effectiveness of a newly established pediatric IMCU in a tertiary referral children's hospital, providing much-needed insights into patient management, outcomes, and healthcare system impacts.

Materials and methods

This single-center retrospective observational study focused on patients with NMDs admitted to the Pediatric IMCU at IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, from January 1st, 2021, to June 30th, 2023. We specifically selected patients referring to the NMDs classification reported in the recent workshop of the Italian Muscular Dystrophy Association Medical Scientific Committee (2) and identified by the corresponding ICD-9 diagnosis codes, as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Data were meticulously extracted from electronic medical records, including demographic details, clinical characteristics, therapeutic interventions, duration of IMCU stay, and post-discharge outcomes, particularly mortality within 28 days of leaving the IMCU. Furthermore, we analyzed the number of total ICU and IMCU admissions, and the number of ICU and IMCU admissions of patients with NMDs with their corresponding length of stay, analyzing the trends over the years.

Unique to our study, non-pediatric patients, who are regularly followed at our Institute for chronic NMDs beyond the age of 18, were also included, reflecting the ongoing care continuum for these conditions.

The study was set in the IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, a comprehensive tertiary care children's hospital. The hospital is the hub of the Region Liguria for pediatric emergencies. It is equipped with 328 pediatric beds and 18–20 level-IV pediatric ICU beds with critical care transport and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation retrieval capability. Notably, a 12-bed pediatric IMCU, functioning as a critical bridge between ICU and general wards, was established here at the end of 2020, enhancing our patient care capabilities.

The IMCU operates as a stand-alone unit adjacent to the pediatric ICU. Details on the infrastructure, equipment, and organization of the IMCU have already been published (20).

IMCU works as a flexible central component in the hospital, admitting acute patients from the ED, working as a step-down unit for ICU patients, or as a step-up unit for inpatients with worsening conditions admitted to low-intensity pediatrics units.

The Criteria for admission and discharge of NMDs patients were derived from the general criteria for pediatric IMCU developed by a multispecialty team and referred to published guidelines for pediatric IMCUs (14, 21).

In case of clinical deterioration, the IMCU pediatrician and the critical care specialist, with the support of the NMD specialist, agree upon ICU admission. On the other hand, the two pediatricians of the IMCU and ward decide on discharge to the low-intensity unit when the complexity of care is compatible with the policies of the receiving unit (Supplementary Table S2).

We employed descriptive statistics to outline our patient cohort's demographic and clinical profiles. Statistical measures included mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables, median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. To assess outcomes, Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were utilized where appropriate, with further analysis of IMCU stay duration using appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests. For this purpose, we used using Jamovi 2.4, an open-source R graphical frontend (22, 23). The association between discharge destination (home, lower intensity-care unit, or ICU) and different potential explanatory variables was assessed using multivariable logistic models, while IMCU length of stay with linear regression. In the multivariable models, we considered only the variables significant at univariable analysis relevant.

Results

During the study period, the IMCU received 1,722 admissions, with 63 patients (3.6%) diagnosed with NMDs. This subset represents a focused but significant portion of our patient population.

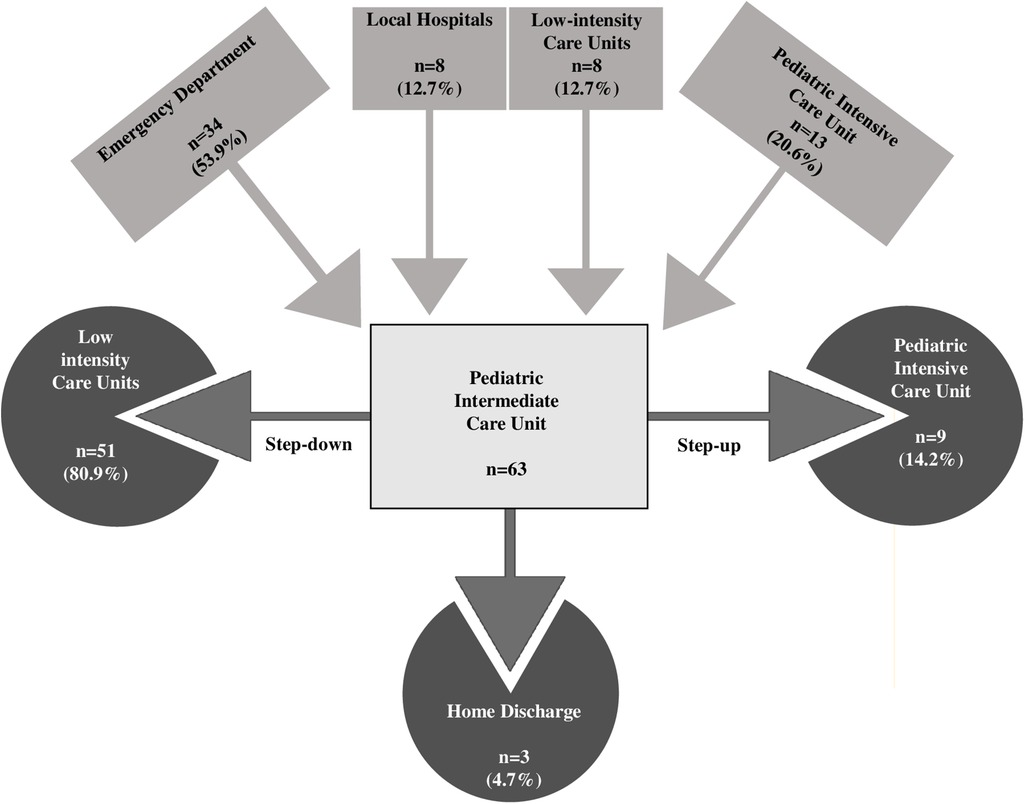

Table 1 summarizes the main demographics, clinical, therapeutic, and outcome data. Patients with NMDs had a median age of 12 years (IQR: 13.5 years, range 1 month-22 years), and females comprised the majority of this group (37 patients, 58.7%). Sixteen patients (25%) were aged >18 years. Admissions originated diversely: 54% from the ED, 20.6% as step-down from ICU, 12.7% from low-intensity care units, and the remaining 12.7% from other local hospitals. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy was the most represented category (20 patients, 31.7%) among the underlying etiologies. Neurological complications were the leading cause of admission (39.7%), closely followed by respiratory issues (34.9%). Of note, 59% of the patients required respiratory support upon admission, which increased to 70% during their IMCU stay. Overall, steroids were administered to 17/63 patients (27%). In 9 cases steroids were administered for respiratory failure, in 4 patients with immune-mediated diseases (myasthenia gravis, peripheral neuropathy) for worsening clinical conditions, and in the remaining 4 patients with mitochondrial disease as part of therapeutic management of disease exacerbation.

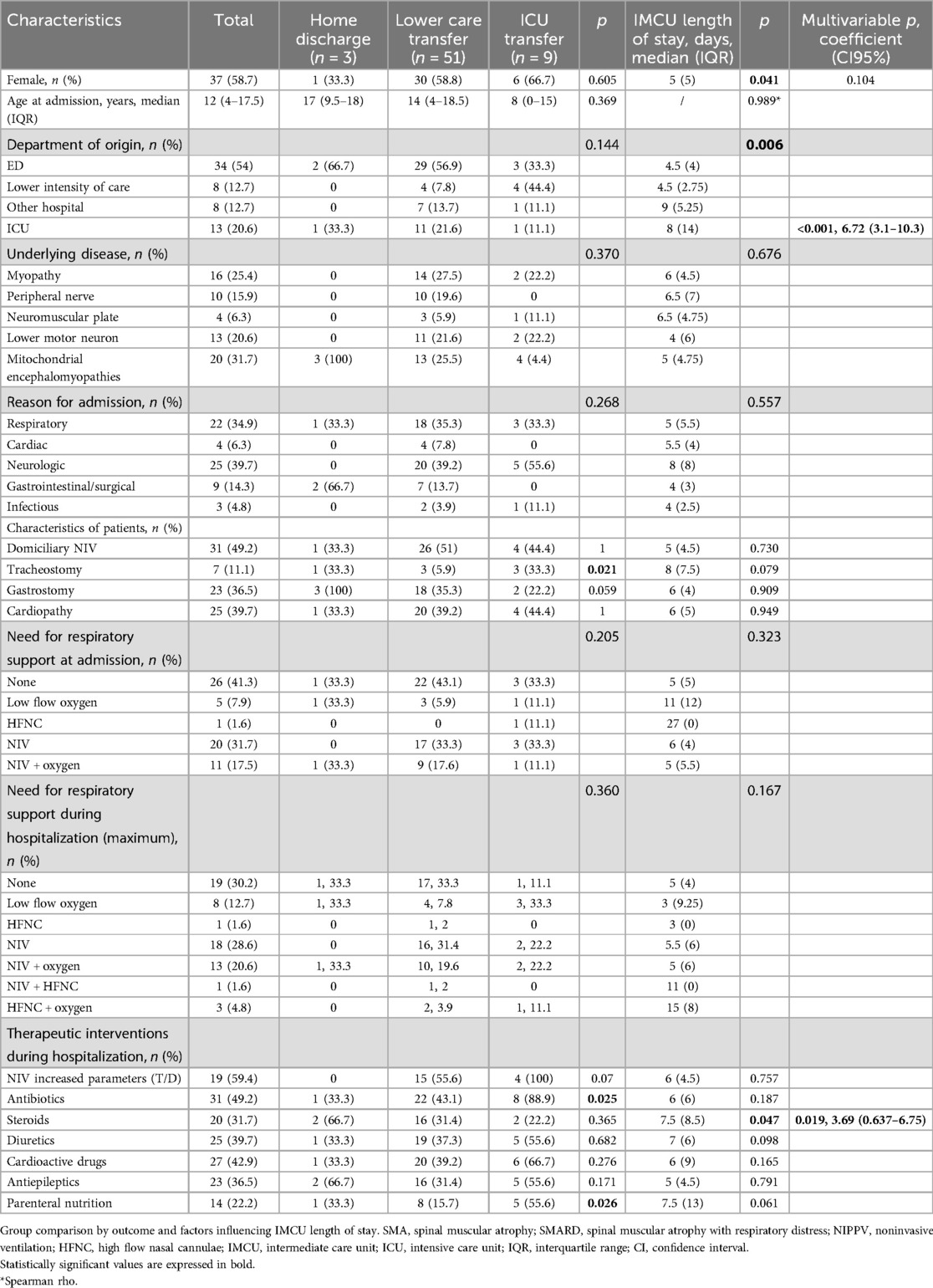

Table 1. Demographical, clinical, therapeutic, and outcome data of patients with NMDs admitted to the pediatric IMCU.

Univariate analysis revealed the presence of tracheostomy (p = 0.021), the need for antibiotics (p = 0.025), and the need for parenteral nutrition (p = 0.026) as factors significantly associated with ICU admission. Moreover, the female gender (p = 0.041), coming from the ICU (p = 0.006), and the use of steroids (p = 0.047) were significantly associated with an increased length of stay in IMCU (Table 1).

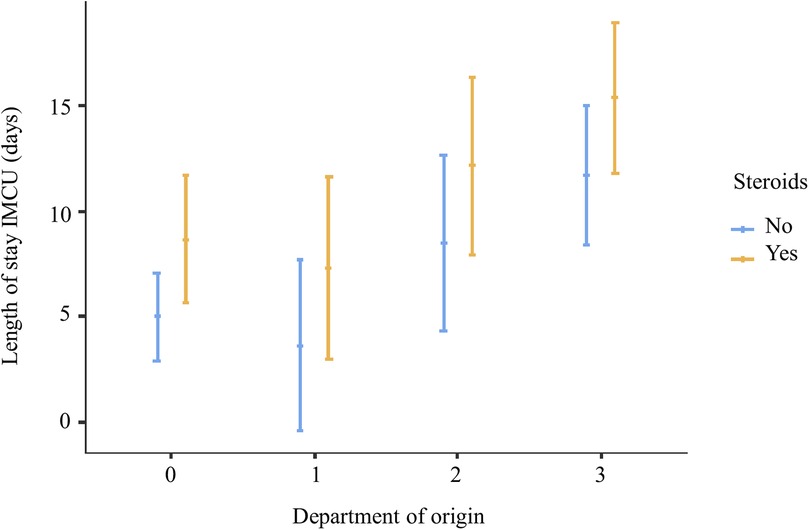

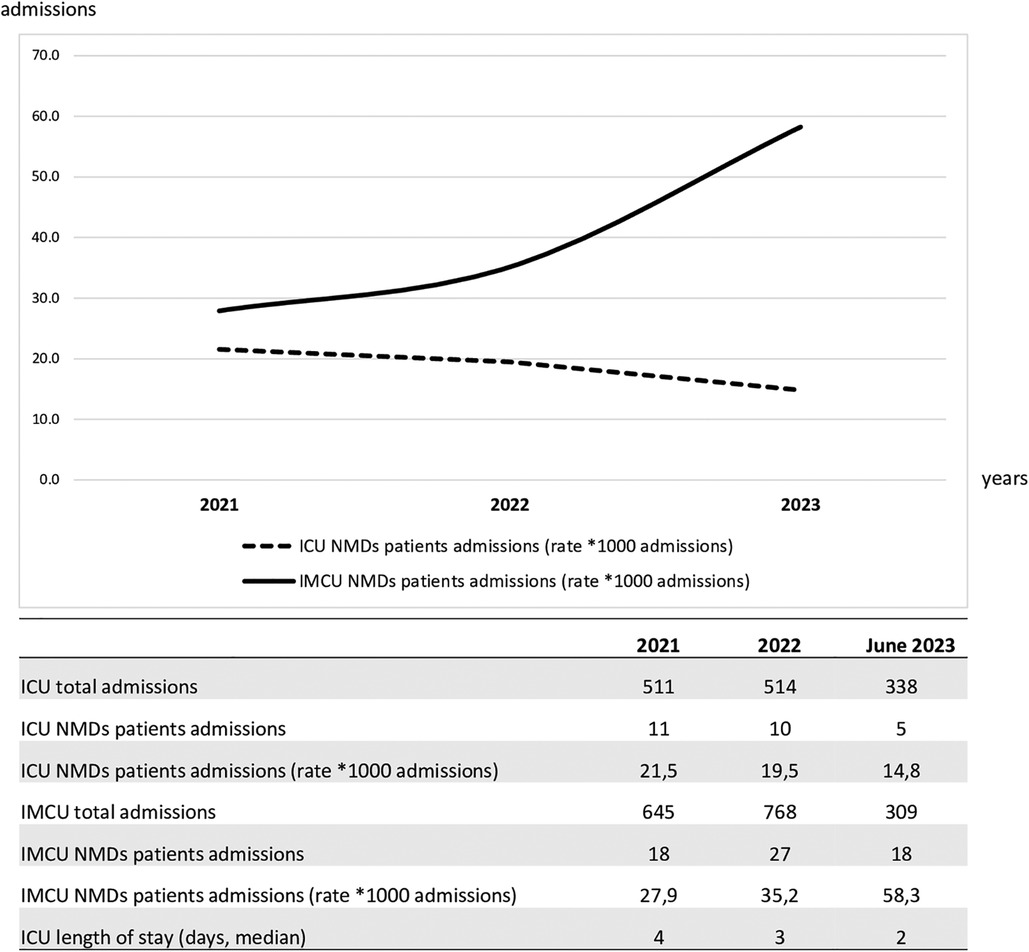

In the multivariable analysis, the transfer from the ICU and the use of steroids was shown to significantly increase the length of IMCU stay of 6.7 days (CI95% 3.1–10.3; p < 0.001) and 3.69 (CI95% 0.637–6.75; p = 0.019; Table 1 and Figure 1). Patients typically spent a median of 5 days in the IMCU (IQR: 5.5 days), reflecting effective management within this setting. Figure 2 shows the flow of patients managed in the IMCU. Most patients (51, 81%) were transferred to a lower-intensity unit following clinical improvement or were directly discharged home (3, 5%). A minority of patients required admission to the ICU (9, 14%) for refractory status epilepticus, need for inotropic support, or respiratory deterioration. Three of them (one 8-year-old girl with myotonic dystrophy type 1, one 3-month-old boy with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, and a 6-month-old girl with Spinal Muscular Atrophy with Respiratory Distress type 1) died during ICU stay. Two other patients died at home within 28 days of discharge from IMCU as part of a palliative care program. As expected, transfer to the ICU significantly increases the risk of death at 28 days. A notable outcome post-IMCU establishment is the marked decrease in ICU admissions for NMD patients, dropping from 21.5 to 14.8 per 1,000 admissions (r = −0.998; p = 0.04). This trend was complemented by an increase in IMCU admissions from 27.9 to 58.3 per 1,000 admissions, highlighting the unit's pivotal role in patient management. In addition, a progressive reduction in the median ICU length of stay of patients with NMDs from 4 to 2 days was noted (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Multivariate analysis showing that steroid treatment and coming from ICU are significantly associated with increased IMCU length of stay 0, emergency department; 1, low-intensity care units; 2, local hospital; 3, intensive care unit.

Figure 3. Trends of intensive care unit and intermediate care unit admissions over the study period of patients with NMDs. ICU, intensive care unit; NMD, neuromuscular disorders; IMCU, intermediate care unit.

Discussion

Our study highlights the central role of a standalone pediatric IMCU in a tertiary Italian children's hospital, specifically in managing patients with NMDs. Although representing a small percentage of total admissions, these patients exhibited an increasing trend over time, underscoring the growing importance of specialized care in this area.

Our data shows how IMCU has proven to be an adequate and functional setting for these children who often do not qualify for pediatric ICU admission but have specific assistance needs and may require levels of care and monitoring that cannot be delivered in ordinary inpatient wards.

The IMCU's integrated multidisciplinary approach, spearheaded by pediatric NMD experts and involving consultants from different specialties (respiratory care, physical and occupational therapy, cardiology, gastroenterology, infectious diseases) with prompt support of critical care physicians when needed, was central to achieving favorable outcomes. This collaborative care model significantly contributed to a low ICU admission rate (14%), although comparisons to other pediatric studies are limited.

We observed that the presence of tracheostomy, the need for antibiotics, and parenteral nutrition were all factors significantly associated with ICU admission. This is easily understandable since these characteristics suggest a more severe course of the disease or a more fragile underlying condition that may result in a need for more frequent access to intensive care. Therefore, close cooperation with intensive care specialists when managing these patients in an IMCU is strongly required to intercept early signs of deterioration.

Particularly, patients with tracheostomy represent a population group that can be well-served by an IMCU. Supporting this, in a national survey of US hospitals, children with tracheostomy and ventilator support, admitted to the hospital for mild non-respiratory infections, were triaged to a pediatric ICU in 65% of hospitals with no IMCU vs. 46% in hospitals with an IMCU (24). Long-term tracheostomy in children is associated with higher complication rates when compared to adults, especially in those who have underlying conditions such as neuromuscular impairment (25). Outcomes of children with a tracheostomy are strongly influenced by other medically complex conditions (feeding pumps, mechanical ventilation, etc.), and complications due to tracheostomies such as ventilator-associated respiratory infections are known to be associated with longer ICU length of stay (26). Confirming this, in our study, 43% of patients with tracheostomy required ICU admission, suggesting that this patient group can be effectively managed in the IMCU but requires specialized care, trained staff, and a higher level of surveillance.

The multivariate analysis revealed that the use of steroids was associated with longer IMCU stays but not with an increase in ICU admission.

Although the evidence for the use of steroids in pediatric critical care is largely extrapolated from research in adult patients, pediatric studies have demonstrated an association between steroid use and poor outcomes (27–29). On the other hand, immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies including corticosteroids are currently recommended for the treatment of immune-mediated neuromuscular diseases. In our series, most patients received steroids due to respiratory failure or worsening clinical conditions in the context of immune-mediated disease. This may explain the association with prolonged stay in IMCU. On the other hand, the IMCU proves to be the appropriate setting of care for these patients as the same population did not have an increased risk of admission to the ICU. Unfortunately, studies focusing on steroid use in acutely ill patients with NMDs as a whole category are not available.

IMCU had a significant role also as a step-down unit. Patients with NMDs often undergo routine surgeries (i.e., scoliosis correction, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, etc.). In these cases, they frequently need to be intubated and mechanically ventilated (30) requiring admission to the ICU. IMCU offers a crucial transition space in these cases, potentially reducing ICU stays, healthcare costs, and enhancing patient comfort.

About one-third of our admissions (about 30%) were due to mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Patients affected by mitochondrial diseases are highly unstable and frequently require critical care. Considering the multisystemic involvement typical of the disease, they often require strict monitoring of neurologic, respiratory, and cardiovascular status as well as metabolic, fluid, and electrolyte balance status (31).

A significant cause of admission to the IMCU was represented by respiratory complications with 59% of patients who needed initiation or increase of respiratory support.

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is increasingly used to manage acute respiratory failure in patients with NMDs and had a tremendous impact on prolonging survival in this population (32–34). An effective treatment of respiratory complications including NIPPV and manual and mechanical mucus clearance techniques is a cornerstone when facing respiratory failure in children with NMDs. However, it requires qualified and skilled staffing with strong interdisciplinary team communication, rigorous monitoring, and frequent reassessment processes.

Pediatric IMCU may be the appropriate setting where patients at nonimmediate risk of requiring intubation can start or potentiate NIPPV. Similar protocols have been successfully implemented in adult IMCUs (16) while pediatric experiences are still limited (35).

Although the short study period reduces the power of our observations, with the establishment of the new IMCU a decreasing trend of ICU admission rates and shorter ICU length of stay has been recorded in patients affected by NMDs. This consequently may result in lower healthcare costs and reduced complications associated with intensive care settings. Furthermore, this may alleviate pressure on the ICU beds and improve appropriate ICU patient care.

In our Institute some patients affected by NMDs aged over 18 years are regularly followed by the Myology Centre. Although this may be considered a limit of the study, they were included in our study to reflect and describe as faithfully as possible the reality of our setting. As survival rates for patients affected by NMDs improve, complexity and criticalness consequently increase with age, along with the need for specialized tertiary care, intense monitoring, and advanced therapies. Reflecting this, in our study population, about 50% of patients older than 18 years had heart disease and tracheostomy.

However, regardless of major complexity, more comorbidities, and chronic therapies, the length of stay of these patients alone was comparable to the whole population and only one adult patient required ICU admission, highlighting the value of IMCU management.

Limitations

Our work has several limitations. We did not conduct a cost analysis, which might have better revealed the importance of the decreased ICU bed use. However, we can preliminarily estimate that a 1-day stay in the IMCU, compared to the ICU, allows for an average saving of 840 euros per patient. We plan to properly evaluate this relevant aspect in a dedicated study. Moreover, the short period included in the study reduces the statistical power of our analysis. We were not able to carry out an adequate comparison with similar studies since research focusing on pediatric IMCU is very limited. In Italy, this likely depends on the lack of specific regulatory legislation which leads to a marked variability in terms of structuring, equipment, and staffing of pediatric IMCUs (36). Following this, the single-center nature of the study may also limit the generalizability of our findings because of site-specific practices and policies, including the availability of staff and equipment, and the hospital organization.

We are also aware that a multicenter study comparing our populations with NMD patients admitted to hospitals without IMCU would be desirable as it would provide even more accurate data on the impact of the introduction of IMCU in a hospital's operation.

Finally, patients with NMDs are affected by different diseases with heterogeneous pathophysiology. Given that, the reasons for hospitalization and the received treatments (i.e., steroids) may vary from one another thus limiting the possibility of drawing definite conclusions.

Multi-center and prospective studies accompanied by the implementation of the development process of pediatric IMCUs and their homogenization may contribute to overcoming these limitations.

Conclusions

While the concept of a pediatric IMCU is still evolving, with variations across healthcare systems, our exploratory findings advocate for its crucial role in the nuanced care of children with NMDs. Future studies should aim to evaluate the broader impacts on hospital costs, pediatric critical care, and both clinical and psychological outcomes for patients.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Regione Liguria Ethical Board (RCR-2022-23682290). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because of the retrospective nature of the study. In any case, consent to completely anonymous use of clinical data for research/epidemiological purposes is requested by the clinical routine at the time of admission/diagnostic procedure in our hospital.

Author contributions

GB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DP: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CF: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation. PS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (NET-2019-12370049).

Acknowledgments

We thank the children and parents who shared their IMCU experience with us. We thank all the nursing staff who support us and make our daily work possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1539540/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

NMD, neuromuscular disorders; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IMCU, intermediate care unit; NIPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation.

References

1. Racca F, Sansone VA, Ricci F, Filosto M, Pedroni S, Mazzone E, et al. Emergencies cards for neuromuscular disorders. 1st consensus meeting from UILDM - Italian muscular dystrophy association. Workshop report. Acta Myol. (2022) 41:135–77. doi: 10.36185/2532-1900-081

2. Darras BT, Jones HR Jr. Neuromuscular problems of the critically ill neonate and child. Semin Pediatr Neurol. (2004) 11(2):147–68. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2004.04.003

3. Harrar DB, Darras BT, Ghosh PS. Acute neuromuscular disorders in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Child Neurol. (2020) 35(1):17–24. doi: 10.1177/0883073819871437

4. Deenen JC, Horlings CG, Verschuuren JJ, Verbeek AL, van Engelen BG. The epidemiology of neuromuscular disorders: a comprehensive overview of the literature. J Neuromuscul Dis. (2015) 2(1):73–85. doi: 10.3233/JND-140045

5. Ricci G, Torri F, Bianchi F, Fontanelli L, Schirinzi E, Gualdani E, et al. Frailties and critical issues in neuromuscular diseases highlighted by SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: how many patients are still “invisible”? Acta Myol. (2022) 41(1):24–9. doi: 10.36185/2532-1900-065

6. Kao WT, Tseng YH, Jong YJ, Chen TH. Emergency room visits and admission rates of children with neuromuscular disorders: a 10-year experience in a medical center in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. (2019) 60(4):405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.09.008

7. Yates K, Festa M, Gillis J, Waters K, North K. Outcome of children with neuromuscular disease admitted to paediatric intensive care. Arch Dis Child. (2004) 89(2):170–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.019562

8. Noritz G, Naprawa J, Apkon SD, Kinnett K, Racca F, Vroom E, et al. Primary care and emergency department management of the patient with duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatrics. (2018) 142(Suppl 2):S90–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0333K

9. Josef F. The spectrum of neuromuscular disorders admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit is broader than anticipated. J Child Neurol. (2020) 35(4):300–1. doi: 10.1177/0883073819894852

10. Simonds AK. Respiratory support for the severely handicapped child with neuromuscular disease: ethics and practicality. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. (2007) 28(3):342–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981655

11. Flandreau G, Bourdin G, Leray V, Bayle F, Wallet F, Delannoy B, et al. Management and long-term outcome of patients with chronic neuromuscular disease admitted to the intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure: a single-center retrospective study. Respir Care. (2011) 56(7):953–60. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00862

12. Ko MSM, Poh PF, Heng KYC, Sultana R, Murphy B, Ng RWL, et al. Assessment of long-term psychological outcomes after pediatric intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176(3):e215767. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5767

13. Pryce P, Gangopadhyay M, Edwards JD. Parental adverse childhood experiences and post-PICU stress in children and parents. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2023) 24(12):1022–32. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000003339

14. Jaimovich DG, Committee on Hospital Care and Section on Critical Care. Admission and discharge guidelines for the pediatric patient requiring intermediate care. Crit Care Med. (2004) 32(5):1215–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000126001.23141.4F

15. Plate JDJ, Leenen LPH, Houwert M, Hietbrink F. Utilisation of intermediate care units: a systematic review. Crit Care Res Pract. (2017) 2017:8038460. doi: 10.1155/2017/8038460

16. Capuzzo M, Volta C, Tassinati T, Moreno R, Valentin A, Guidet B, et al. Hospital mortality of adults admitted to intensive care units in hospitals with and without intermediate care units: a multicentre European cohort study. Crit Care. (2014) 18(5):551. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0551-8

17. Solberg BC, Dirksen CD, Nieman FH, van Merode G, Ramsay G, Roekaerts P, et al. Introducing an integrated intermediate care unit improves ICU utilization: a prospective intervention study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2014) 14:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-76

18. Bertolini G, Confalonieri M, Rossi C, Rossi G, Simini B, Gorini M, et al. Costs of the COPD. Differences between intensive care unit and respiratory intermediate care unit. Respir Med. (2005) 99(7):894–900. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.014

19. Cheng DR, Hui C, Langrish K, Beck CE. Anticipating pediatric patient transfers from intermediate to intensive care. Hosp Pediatr. (2020) 10(4):347–52. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0260

20. Brisca G, Tardini G, Pirlo D, Romanengo M, Buffoni I, Mallamaci M, et al. Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic: IMCU as a more efficient model of pediatric critical care organization. Am J Emerg Med. (2023) 64:169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.12.009

21. Ettinger NA, Hill VL, Russ CM, Rakoczy KJ, Fallat ME, Wright TN, et al. Guidance for structuring a pediatric intermediate care unit. Pediatrics. (2022) 149(5):e2022057009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057009

22. The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 2.4) [Computer Software] (2023). Available online at: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed August 10, 2023).

23. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software] (2022). Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org (R packages retrieved from CRAN snapshot 2023-04-07) (accessed August 10, 2023).

24. Russ CM, Agus M. Triage of intermediate-care patients in pediatric hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. (2015) 5(10):542–7. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0144

25. Fuller C, Wineland AM, Richter GT. Update on pediatric tracheostomy: indications, technique, education, and decannulation. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. (2021) 9(2):188–99. doi: 10.1007/s40136-021-00340-y

26. Volsko TA, Parker SW, Deakins K, Walsh BK, Fedor KL, Valika T, et al. AARC clinical practice guideline: management of pediatric patients with tracheostomy in the acute care setting. Respir Care. (2021) 66(1):144–55. doi: 10.4187/respcare.08137

27. Yehya N, Servaes S, Thomas NJ, Nadkarni VM, Srinivasan V. Corticosteroid exposure in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. (2015) 41(9):1658–66. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3953-4

28. Jacobs A, Derese I, Vander Perre S, Wouters PJ, Verbruggen S, Billen J, et al. Dynamics and prognostic value of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to pediatric critical illness and association with corticosteroid treatment: a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46(1):70–81. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05854-0

29. Menon K, McNally JD, Choong K, Lawson ML, Ramsay T, Hutchison JS, et al. A cohort study of pediatric shock: frequency of corticosteriod use and association with clinical outcomes. Shock. (2015) 44(5):402–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000355.25692259

30. Birnkrant DJ, Pope JF, Eiben RM. Management of the respiratory complications of neuromuscular diseases in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Child Neurol. (1999) 14(3):139–43. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400301

31. Arslan Ş, Yorulmaz A, Sert A, Akin F. Management of acute mitochondriopathy and encephalopathy syndrome in pediatric intensive care unit: a new clinical entity. Acta Neurol Belg. (2020) 120(5):1115–21. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01125-3

32. Gregoretti C, Ottonello G, Chiarini Testa MB, Mastella C, Ravà L, Bignamini E, et al. Survival of patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 1. Pediatrics. (2013) 131(5):e1509–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2278

33. Simonds AK. Home ventilation. Eur Respir J Suppl. (2003) 47:38S–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00029803

34. Khirani S, Bersanini C, Aubertin G, Bachy M, Vialle R, Fauroux B. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to facilitate the post-operative respiratory outcome of spine surgery in neuromuscular children. Eur Spine J. (2014) 23(Suppl 4):S406–11. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3335-6

35. Smith A, Kelly DP, Hurlbut J, Melvin P, Russ CM. Initiation of noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure in a pediatric intermediate care unit. Hosp Pediatr. (2019) 9(7):538–44. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0034

Keywords: pediatric intermediate care unit, neuromuscular disorders, tracheostomy, intensive care unit admission, patient outcome, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation

Citation: Brisca G, Strati MF, Canzoneri F, Mariani M, Pirlo D, Romanengo M, Tardini G, Brolatti N, Buratti S, Pedemonte M, Fiorillo C, Striano P, Bruno C and Moscatelli A (2025) Evaluating treatment and care outcomes for neuromuscular diseases in a pediatric intermediate care setting. Front. Pediatr. 13:1539540. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1539540

Received: 4 December 2024; Accepted: 19 March 2025;

Published: 9 April 2025.

Edited by:

Satinder Aneja, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Associated Hospitals, IndiaReviewed by:

Neha Gupta, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United StatesMahesh Kamate, KLE Univeristy, India

Copyright: © 2025 Brisca, Strati, Canzoneri, Mariani, Pirlo, Romanengo, Tardini, Brolatti, Buratti, Pedemonte, Fiorillo, Striano, Bruno and Moscatelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giacomo Brisca, Z2lhY29tb2JyaXNjYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Giacomo Brisca

Giacomo Brisca Marina F. Strati1,2

Marina F. Strati1,2 Marcello Mariani

Marcello Mariani Marina Pedemonte

Marina Pedemonte Pasquale Striano

Pasquale Striano Claudio Bruno

Claudio Bruno Andrea Moscatelli

Andrea Moscatelli