94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Pediatr., 12 March 2025

Sec. Neonatology

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2025.1491976

This article is part of the Research TopicReviews in Neonatology 2024View all 5 articles

Viraraghavan Vadakkencherry Ramaswamy1

Viraraghavan Vadakkencherry Ramaswamy1 Gunjana Kumar2

Gunjana Kumar2 Abdul Kareem Pullattayil S3

Abdul Kareem Pullattayil S3 Abhishek S. Aradhya4

Abhishek S. Aradhya4 Pradeep Suryawanshi5

Pradeep Suryawanshi5 Mohit Sahni6

Mohit Sahni6 Supreet Khurana7

Supreet Khurana7 Shiv Sajan Saini8

Shiv Sajan Saini8 Ravishankar K9

Ravishankar K9 Shashi Kant Dhir10

Shashi Kant Dhir10 Deepak Chawla7

Deepak Chawla7 Praveen Kumar8

Praveen Kumar8 Kiran More11* on behalf of the National Neonatal Forum, Clinical Practice Guidelines Group, India

Kiran More11* on behalf of the National Neonatal Forum, Clinical Practice Guidelines Group, India

Background: The effect of the timing of initiation of hydrocortisone in neonatal shock has not been evaluated. The objective of this systematic review was to compare the effect of earlier vs. later initiation of hydrocortisone in neonatal shock.

Methods: Medline, Embase, and CENTRAL were searched from inception until 15 May 2024. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs were eligible for inclusion. A random effects meta-analysis was used to synthesize the data. The evidence certainty was evaluated according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). A clinical practice guideline was formulated as recommended by the GRADE group.

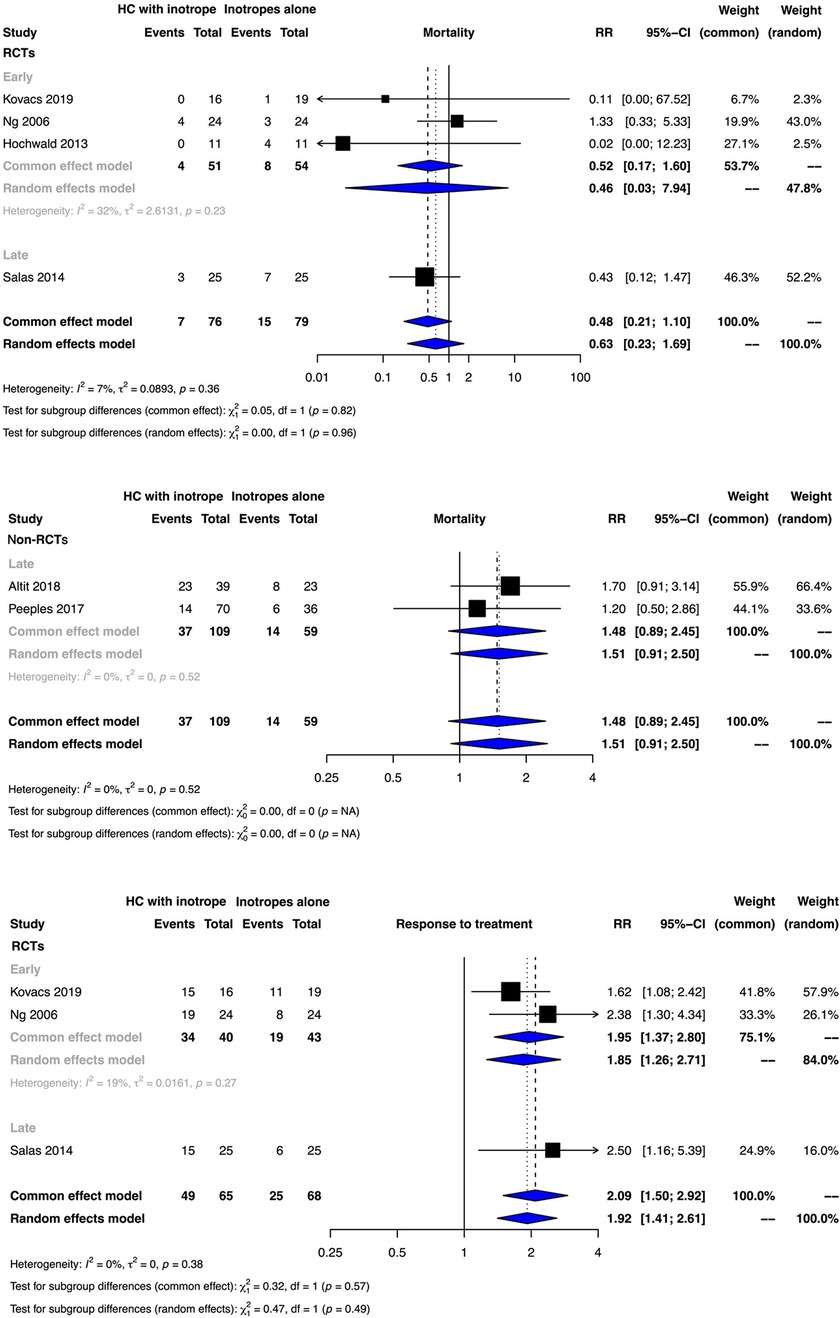

Results: Of the 3,757 titles and abstracts screened, 20 studies were included: 7 RCTs and 13 non-RCTs. While clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for the outcome of mortality from the meta-analysis of the RCTs [early initiation risk ratio (RR): 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.03–7.92; late initiation RR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.12–1.47], the non-RCTs included in the narrative review suggested that late hydrocortisone initiation might be associated with increased risk of mortality. The meta-analysis indicated that early and late hydrocortisone administration may be associated with an increased response to treatment therapy (early initiation RR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.26–2.71; late initiation RR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.16–5.39). Late hydrocortisone initiation may increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) ≥ stage 2 (RR: 2.46, 95% CI: 1.19–5.08). The evidence certainty was very low for most of the outcomes evaluated.

Conclusion: The early use of hydrocortisone in neonates with shock requiring vasopressors is associated with better outcomes and no major adverse effects. Later institution of hydrocortisone therapy in neonatal shock may improve the response to therapy but may be associated with adverse outcomes including mortality and NEC. The results are to be interpreted with caution as the evidence certainty was predominantly very low.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023432169, identifier: CRD42023432169.

The use of hydrocortisone (HC) as an adjunct to inotropes in the treatment of neonatal shock is increasing, especially in extremely low birth weight (ELBW) neonates (1). Hydrocortisone administration in vasopressor-resistant shock has been shown to be associated with improved blood pressure (BP) in neonatal shock (2). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2022) concluded that prophylactic early use of hydrocortisone (≤7 days) is associated with a decreased risk of mortality or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in ELBW infants exposed to chorioamnionitis (3). Similarly, the Canadian Paediatric Society 2020 recommended the use of early hydrocortisone (within 24–48 h) in extremely low gestational age neonates (ELGANs) born at <28 weeks’ gestation or those born through chorioamnionitis (3). There are no specific guidelines for hydrocortisone usage in vasopressor-resistant shock in neonates, especially with relation to its timing of initiation and dosage.

The mechanism of action of hydrocortisone in neonates with vasopressor-resistant shock includes sensitization of the cardiovascular system to catecholamines through the upregulation of adrenergic receptors, inhibition of catecholamine metabolism, and stabilization of capillary integrity (4). Hydrocortisone also facilitates the reuptake of norepinephrine into the sympathetic system and the expression of angiotensin type 2 receptors in the myocardium, thereby stabilizing the cardiovascular system and maintaining its sensitivity to vasopressors (4).

The etiology of adrenal insufficiency differs between term and preterm neonates (2, 5). While very preterm neonates are known to have primary adrenal insufficiency, the etiopathogenesis in both preterm and term neonates with shock could also be attributed to relative adrenal insufficiency (RAI) (6, 7). RAI is presumed to be due to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction (8). In a neonate with shock, the HPA axis may be affected due to reasons such as decreased secretion of cortisol from the adrenal gland secondary to ischemia, resistance of adrenal receptors to adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) due to inflammatory cytokines, and, finally, a lack of corticosteroid reserve in the adrenal gland relative to the increased metabolic demands (2, 4, 9). Unlike in pediatric and adult populations where there are specific cut-off levels to define primary and RAI, the definitions in neonates are contentious (8, 10, 11). Furthermore, studies in neonates with shock have shown conflicting results for the correlation between baseline serum cortisol levels and treatment response of shock or other adverse events with hydrocortisone administration guided by cortisol levels (12–16).

There is a lacuna in the literature as to when hydrocortisone has to be considered in neonates with shock. Hence, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted specifically to evaluate the timing of hydrocortisone initiation in relation to vasopressor therapy. A scoping review of the literature suggested that there was no randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing hydrocortisone administration with respect to the timing of hydrocortisone initiation in relation to vasopressor therapy in neonates with shock. Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing hydrocortisone therapy vs. no hydrocortisone therapy and addressed our objective through sub-group analyses.

Population (P): Preterm and term neonates (of ≤28 days) diagnosed with shock (as defined by the authors) who were treated with volume expansion and/or inotropes.

Intervention (I): Hydrocortisone of any dosage along with the initiation of the first inotrope (dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, or vasopressin). Early vs. late initiation of hydrocortisone was defined as follows:

Early: Initiation of hydrocortisone prior to the initiation of inotropes or along with the addition of the first inotrope or with increasing requirement of inotropes [a cut-off vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) of ≤10 was taken]. VIS is calculated as follows:

VIS = 1 × Dopamine (μg/kg/min) + 1 × Dobutamine (μg/kg/min) + 100 × Epinephrine (μg/kg/min) + 100 × Norepinephrine (μg/kg/min) + 10 × Milrinone (μg/kg/min) + 10,000 × Vasopressin (IU/kg/min).

Late: Initiation of hydrocortisone when high dosages of inotropes were required (VIS of > 10).

Comparator (C): Use of inotropes alone.

Outcomes (O): The primary outcomes were mortality and response to therapy (as defined by the authors) between 6 and 24 hours after hydrocortisone initiation. Secondary outcomes included blood culture-positive sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) ≥ stage 2 (17), major brain injury (MBI) [intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) > grade 2 and/or cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL)] (18, 19), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) requiring intervention (20), BPD [defined as oxygen requirement at 36 weeks’ post-menstrual age (PMA)], patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) requiring intervention (medical or surgical), change in BP, duration of inotropes, invasive mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

Study designs (S): RCTs; observational studies of either prospective, retrospective, or pre-post design; and conference abstracts were eligible for inclusion. There were no language restrictions. Descriptive reviews and systematic reviews were excluded.

Time frame (T): From inception of the searched databases until 15 May 2024.

Medline, Embase, and CENTRAL were searched from their inception until 15 May 2024 (Supplementary Table S1). Title and abstract screening for the inclusion of studies in the systematic review was performed using online software (Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) by two authors blinded to each other (21). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The reference lists of the included studies and other similar systematic reviews were searched for potentially eligible studies.

Two authors extracted data using a pre-specified pro forma. Data synthesis was performed using R software version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (22). A random effects pair-wise meta-analysis was performed using the Mantel–Haenszel method for binary outcomes, and the inverse variance method for continuous outcomes.

The risk of bias assessment was performed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool version 2.0 for RCTs (23) and Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) for non-RCTs (24) by two authors independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Evidence certainty was assessed as per the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines (25). The results of the systematic review and meta-analysis were reported according to modified GRADE recommendations (26, 27) (Supplementary Table S2).

The Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework according to the GRADE working group guidelines was used to arrive at recommendations (28).

For this study design, i.e., a systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline, ethical approval is not required.

Of the 3,757 titles and abstracts screened, 20 studies were included: 7 RCTs and 13 observational studies (1, 4, 12–15, 29–42). Of these, four RCTs (15, 33, 35, 39) and five observational studies (4, 29, 36, 37, 42) were synthesized in a meta-analysis; three RCTs (14, 31, 34) and eight observational studies (1, 12, 13, 30, 32, 38, 40, 41) were described in the narrative review. Amongst the observational studies, only those that had compared neonates with similar baseline characteristics and those that had adjusted for baseline sickness were included in the data synthesis, and the rest were included in the narrative review. The PRISMA flow is provided in Figure 1. The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analyses are given in Tables 1, 2 and those included in the narrative review are provided in Table 3.

Except for two RCTs (14, 34), all the others had a low risk of overall bias. Whilst one had some issues regarding the domain of measurement of the outcome (14), the other had some issues regarding selective reporting (34) (Supplementary Table S3a).

Whilst only two non-RCTs had a moderate risk of overall bias (36, 41), all the other observational studies had a serious risk of overall bias. The predominant reasons for the studies being adjudged as having a serious risk of bias were due to confounding and issues with the classification of interventions (Supplementary Table S3b).

The meta-analyses of RCTs indicated that clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for the outcome of mortality with the use of early or late hydrocortisone along with inotropes when compared to inotropes alone as the effect estimates were statistically non-significant and the certainty of evidence was very low [early initiation risk ratio (RR): 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.03–7.92; late initiation RR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.12–1.47)]. No observational study reported the outcome of mortality for the use of early hydrocortisone (Figure 2, Supplementary Tables S4, S5). The results from non-RCTs were similar to those of RCTs for late hydrocortisone administration (Figure 2, Supplement Table S5).

Figure 2. Forest plots depicting the outcomes of mortality and treatment response from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs.

The very low certainty of evidence suggested that early and late hydrocortisone administration possibly improved the response to inotrope therapy (early initiation RR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.26–2.71; late initiation RR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.16–5.39) (Figure 2, Supplementary Tables S4, S5).

Clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for any of the clinical outcomes from the meta-analyses of RCTs for either early or late hydrocortisone due to statistically non-significant effect estimates and very low to low evidence certainty (Supplementary Figures S1, S2, Tables S4, S5).

The very low certainty of evidence from an observational study indicated that the late hydrocortisone therapy possibly increased the risk of NEC ≥ stage 2 (RR: 2.46, 95% CI: 1.19–5.08) (Supplementary Figure S1, Table S2).

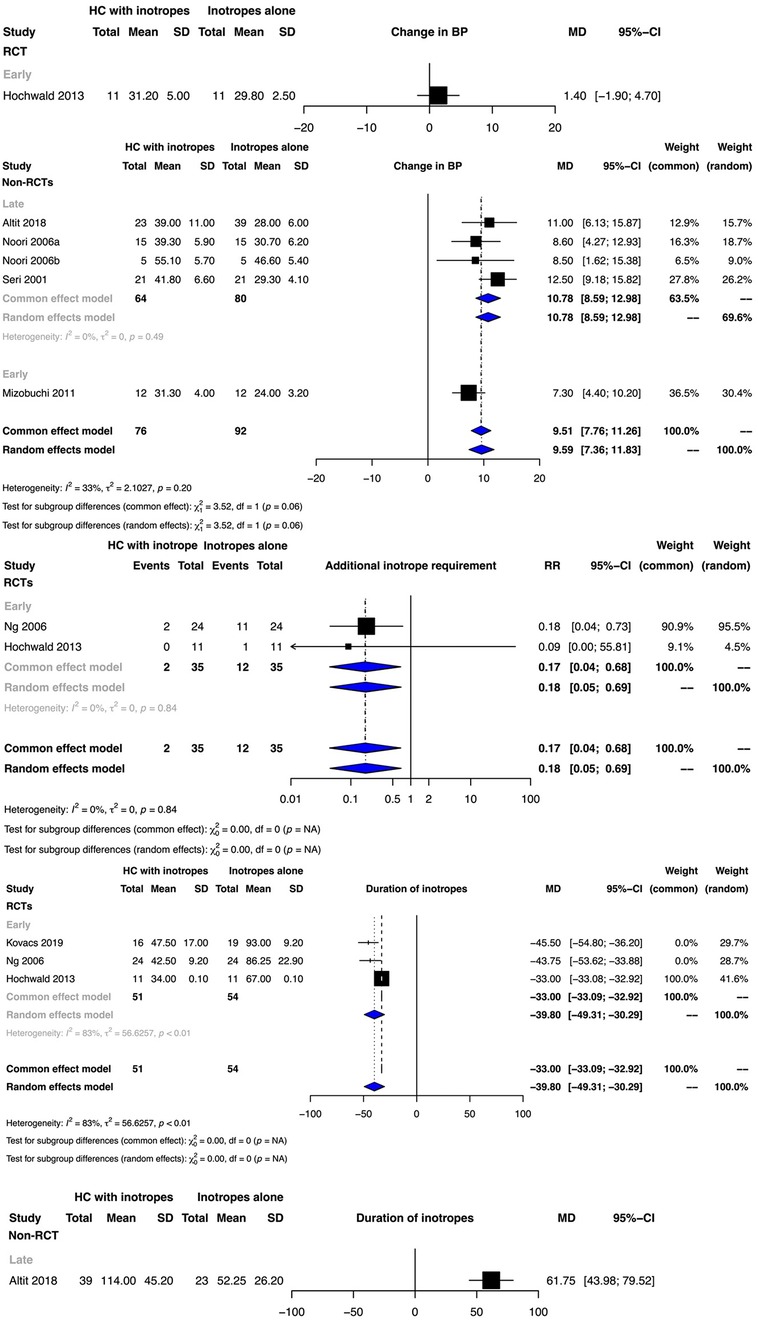

Clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for this outcome for early hydrocortisone therapy as reported from a single RCT (Figure 3). Meta-analyses of non-RCTs indicated that the administration of hydrocortisone in addition to vasopressor therapy either early or late possibly increased the mean BP, with the evidence certainty being very low [early initiation mean difference (MD): 10.78 mm Hg, 95% CI: 4.40–10.20); late initiation MD: 10.78 mm Hg, 95% CI: 8.59–12.98) (Figure 3, Supplementary Tables S4, S5).

Figure 3. Forest plots depicting the outcomes of additional inotrope requirement, change in blood pressure (BP,) and inotrope duration from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs.

The low certainty of evidence suggested that early hydrocortisone therapy possibly decreased the risk of the requirement of additional inotropes (RR: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.05–0.69) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S4).

Whilst early hydrocortisone initiation possibly decreased the duration of inotrope therapy (MD: −39.8, 95% CI: −30.29 to −49.31; very low certainty), late hydrocortisone initiation possibly increased the duration (MD: 61.75 h, 95% CI: 43.98–79.52; low certainty) (Figure 3, Supplementary Tables S4, S5). While clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for the duration of hospitalization for early hydrocortisone therapy from the meta-analysis of two RCTs, one observational study indicated that late hydrocortisone therapy possibly increased the duration of hospitalization (MD: 38.00 days, 95% CI: 12.11–63.89; low certainty) (Supplementary Figure S2, Tables S4, S5).

Clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for the outcome of duration of ventilation for early and late hydrocortisone administration (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Tables S4, S5).

The study by Ng et al. found a higher incidence of glycosuria in the hydrocortisone-treated group (p = 0.03) (35).

Bourchier and Weston reported that there was no correlation between the levels of cortisol (after ACTH stimulation) either at baseline or during therapy and the maximum dopamine dosage (14). However, Kovacs et al. reported that baseline cortisol levels were low (<15 μg/dl) in both the randomized groups (early hydrocortisone initiation with inotropes vs. inotropes alone) and that the levels in the inotropes alone group progressively decreased during treatment (p = 0.02) (15). Three observational studies indicated that late hydrocortisone therapy in neonates with high baseline cortisol levels may be associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse events such as hyperglycemia requiring insulin therapy, hypertension, and mortality (13, 29, 37).

Amongst the eight studies included in the narrative review, all except one had evaluated late hydrocortisone therapy. (Table 3) Of the three RCTs included in the descriptive review (14, 31, 34), two had evaluated early hydrocortisone therapy (14, 31). Most of the studies reported an increase in mean BP and a reduction in inotrope usage after hydrocortisone initiation. Robertson et al. studied the use of late hydrocortisone therapy in neonates diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and reported that after adjusting for baseline sickness, late hydrocortisone therapy was associated with an increased risk of mortality, and that the total duration of hydrocortisone treatment was associated with an increased risk of sepsis (13). Ramanathan et al. concluded that the late administration of hydrocortisone was associated with an increased risk of fungal sepsis (38). Verma et al., in their multivariate analysis, found that late administration of hydrocortisone was associated with an increased risk of IVH in preterm neonates of ≤25 weeks of gestation (40). Helbock et al., who studied late hydrocortisone therapy, reported that four of the six hypotensive ELBW neonates had a baseline cortisol level of <5 μg/dl (12). However, Robertson et al. did not find any statistically significant difference in survival between hypotensive infants with CDH and baseline cortisol levels. The characteristics of the studies included in the narrative review are provided in Table 3.

The EtD framework and the recommendations are provided in Supplementary Tables S6, S7.

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that early hydrocortisone therapy in neonates who require vasopressor therapy was associated with improved outcomes with no major adverse events when compared to the late administration of hydrocortisone.

The results of this meta-analysis indicated that clinical benefit or harm could not be ruled out for the outcome of mortality for either of the interventions. However, Altit et al., Peeples, and Noori et al. indicated that late hydrocortisone therapy possibly increased the risk of mortality (29, 36, 37). The results from these studies could not be pooled and were considered in the EtD framework when we formulated the recommendations. For the outcome of the response to therapy, both early and late hydrocortisone therapy as an adjunct to inotropes were possibly beneficial. Further, late HC therapy was possibly associated with an increased duration of inotrope therapy. Multiple studies in adult populations have reported that prolonged exposure to inotrope therapy is associated with an increased risk of mortality (43–45). We hypothesize that the prolonged exposure to inotropes in the late hydrocortisone group may have contributed to increased mortality. One non-RCT included in our systematic review indicated that late hydrocortisone therapy was possibly associated with an increased risk of NEC ≥ stage 2. Two observational studies included in this systematic review also suggested that late hydrocortisone administration was possibly associated with an increased risk of sepsis (13, 38). Similarly, Hotta et al. also indicated that exposure to dopamine was associated with an increased risk of sepsis in ELGANs, even after adjusting for baseline sickness, which could explain the findings of our systematic review (46).

The results of this systematic review were contentious with respect to baseline cortisol levels and their correlation with response to hydrocortisone therapy or adverse events. Whilst one RCT that had enrolled ELGANs suggested no correlation (14), the other that had included a relatively mature group of infants indicated that the cortisol levels progressively decreased in the placebo group (15). The discrepancy in the results could be attributed to the difficulty in interpreting cortisol levels in neonates as it is complicated by several factors (2). The results from observational studies predominantly suggested that late hydrocortisone therapy in neonates with high baseline cortisol levels was possibly associated with an increased risk of adverse effects including mortality (13, 29, 37). The patient population enrolled in these studies was widely heterogeneous, including ELGANs, infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with therapeutic hypothermia, and those who were diagnosed with CDH. None of the included studies had evaluated long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. However, prophylactic low-dose hydrocortisone therapy in ELGANs at the highest risk of mortality or BPD has been studied extensively (47–50). Some of these studies used hydrocortisone for a prolonged period, even up to 15 days at relatively high cumulative dosages (up to >10 mg/kg) (47, 51). Most of these studies indicated improved long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes with prophylactic hydrocortisone, though the patient population evaluated in these studies differed from ours (52–54). Unlike dexamethasone, which only has glucocorticoid activity, suppresses endogenous cortisol, and, hence downregulates the mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation of neurons through endogenous cortisol, resulting in neuronal apoptosis, hydrocortisone acts similar to endogenous cortisol with the stimulation of both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. This might be one of the possible reasons for better long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes with hydrocortisone when compared to dexamethasone.

After careful consideration of the aspects specified in the EtD framework, the guideline development group suggested that early hydrocortisone may be used in the treatment of neonates with fluid refractory shock as an adjunct to inotropes. We suggest initiating hydrocortisone therapy when there is an increased requirement for inotropes. The most commonly used first-line inotrope included in this systematic review was dopamine, and hydrocortisone therapy may be initiated if the neonate requires a dopamine dosage of ≥10 μg/kg/min, which translates to a VIS of 10. There is insufficient evidence to recommend the timing of the introduction of hydrocortisone in relation to other inotropes such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin, and milrinone when used as a first-line treatment. In such scenarios, dopamine equivalent doses adjudged according to the VIS may be considered. The equivalent doses would be dobutamine ≥10 mcg/kg/min, epinephrine ≥0.1 mcg/kg/min, norepinephrine ≥0.1 mcg/kg/min, vasopressin ≥0.0001 IU/kg/min, and milrinone ≥1 μg/kg/min. This is a weak recommendation with very low evidence certainty.

The dosage of hydrocortisone utilized in the studies varied widely. In preterm neonates, 1 mg/kg followed by 0.5–1 mg/kg every 8–12 h of hydrocortisone may be considered. Whereas in term neonates, a dose of 2 mg/kg followed by 1 mg/kg every 6–8 h may be used. Further, hydrocortisone may be tapered over 2–3 days once the desired effect has been achieved, i.e., when the neonate is being weaned from inotropes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only clinical practice guideline on the timing of instituting hydrocortisone therapy in neonates with shock. There were several limitations to this systematic review. First, it was a pragmatic review with a widely disparate patient population. Second, the dosage of hydrocortisone utilized was different between the included studies. We addressed the first two limitations by downrating the level of evidence for the indirectness related to the patient population domain and the intervention. Finally, we only included published literature.

Earlier use of hydrocortisone in neonates with shock is possibly associated with better outcomes with no significant adverse effects. Later administration of hydrocortisone in neonates with shock may be associated with an increased risk of mortality, NEC, and prolonged duration of inotropes and hospital stay. The recommendations were predominantly based on very low evidence certainty which indicates the need for adequately powered multi-center trials that evaluate the timing of introduction of hydrocortisone in neonatal shock.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

VR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

We acknowledge all the members of the NNF, India CPG group 2023 for their valuable suggestions. This work was undertaken as part of the development of CPGs by NNF, India. The executive summary of the final recommendations will be available on the NNFI website.

The authors declare that this research was done without any financial relationships that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1491976/full#supplementary-material

1. Rios DR, Moffett BS, Kaiser JR. Trends in pharmacotherapy for neonatal hypotension. J Pediatr. (2014) 165(4):697–701.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.009

2. Kumbhat N, Noori S. Corticosteroids for neonatal hypotension. Clin Perinatol. (2020) 47(3):549–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2020.05.015

3. Cummings JJ, Pramanik AK, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Postnatal corticosteroids to prevent or treat chronic lung disease following preterm birth. Pediatrics. (2022):e2022057530. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057530

4. Seri I. Hydrocortisone and vasopressor-resistant shock in preterm neonates. Pediatrics. (2006) 117(2):516–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2057

5. Fernandez E, Schrader R, Watterberg K. Prevalence of low cortisol values in term and near-term infants with vasopressor-resistant hypotension. J Perinatol. (2005) 25(2):114–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211211

6. Ng PC, Lam CW, Lee CH, Ma KC, Fok TF, Chan IH, et al. Reference ranges and factors affecting the human corticotropin- releasing hormone test in preterm, very low birth weight infants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2002) 87(10):4621–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011620

7. Watterberg KL, Scott SM. Evidence of early adrenal insufficiency in babies who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. (1995) 95(1):120–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.95.1.120

8. Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill patients. N Engl J Med. (2003) 348(8):727–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020529

9. Tsao P, von Zastrow M. Downregulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. (2000) 10(3):365–9. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00096-9

10. Aucott SW. The challenge of defining relative adrenal insufficiency. J Perinatol. (2012) 32(6):397–8. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.21

11. Ng PC. Is there a “normal” range of serum cortisol concentration for preterm infants? Pediatrics. (2008) 122(4):873–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0516

12. Helbock HJ, Insoft RM, Conte FA. Glucocorticoid-responsive hypotension in extremely low birth weight newborns. Pediatrics. (1993) 92(5):715–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.92.5.715

13. Robertson JO, Criss CN, Hsieh LB, Matsuko N, Gish JS, Mon RA, et al. Steroid use for refractory hypotension in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg Int. (2017) 33(9):981–7. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4122-3

14. Bourchier D, Weston PJ. Randomised trial of dopamine compared with hydrocortisone for the treatment of hypotensive very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (1997) 76(3):F174–8. doi: 10.1136/fn.76.3.F174

15. Kovacs K, Szakmar E, Meder U, Szakacs L, Cseko A, Vatai B, et al. A randomized controlled study of low-dose hydrocortisone versus placebo in dopamine-treated hypotensive neonates undergoing hypothermia treatment for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. (2019) 211:13–19.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.04.008

16. Renolleau C, Toumazi A, Bourmaud A, Benoist JF, Chevenne D, Mohamed D, et al. Association between baseline cortisol serum concentrations and the effect of prophylactic hydrocortisone in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr. (2021) 234:65–70.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.12.057

17. Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. (1986) 33(1):179–201. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(16)34975-6

18. de Vries LS, Eken P, Groenendaal F, van Haastert IC, Meiners LC. Correlation between the degree of periventricular leukomalacia diagnosed using cranial ultrasound and MRI later in infancy in children with cerebral palsy. Neuropediatrics. (1993) 24(5):263–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071554

19. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. (1978) 92(4):529–34. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80282-0

20. Chiang MF, Quinn GE, Fielder AR, Ostmo SR, Paul Chan RV, Berrocal A, et al. International classification of retinopathy of prematurity, third edition. Ophthalmology. (2021) 128(10):e51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.05.031

21. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at. www.covidence.org (Accessed July 3, 2023).

22. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2020). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed June 3, 2023).

23. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

24. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. (2016) 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

25. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE Guidelines: a new series of articles in the journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64(4):380–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011

26. Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, Garner P, Akl EA, Alper B, et al. GRADE Guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. (2020) 119:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014

27. Ramaswamy VV, de Almeida MF, Dawson JA, Trevisanuto D, Nakwa FL, Kamlin CO, et al. Maintaining normal temperature immediately after birth in late preterm and term infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. (2022) 180:81–98. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.09.014

28. Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE Guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. (2013) 66(7):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013

29. Altit G, Vigny-Pau M, Barrington K, Dorval VG, Lapointe A. Corticosteroid therapy in neonatal septic shock-do we prevent death? Am J Perinatol. (2018) 35(2):146–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606188

30. Baker CF, Barks JD, Engmann C, Vazquez DM, Neal CR Jr, Schumacher RE, et al. Hydrocortisone administration for the treatment of refractory hypotension in critically ill newborns. J Perinatol. (2008) 28(6):412–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.16

31. Batton BJ, Li L, Newman NS, Das A, Watterberg KL, Yoder BA, et al. Feasibility study of early blood pressure management in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr. (2012) 161(1):65–9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.01.014

32. Heckmann M, Pohlandt F. Hydrocortisone in preterm infants. Pediatrics. (2002) 109(6):1184–5. author reply 1184-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1184

33. Hochwald O, Palegra G, Osiovich H. Adding hydrocortisone as 1st line of inotropic treatment for hypotension in very low birth weight infants. Indian J Pediatr. (2014) 81(8):808–10. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1151-3

34. Krediet GT, van der Ent K, Rademaker MAK, van Bel F. Rapid increase of blood pressure after low dose hydrocortison (HC) in low birth weight neonates with hypotension refractory to high doses of cardio-inotropics. Pediatr Res. (1998) 43:38. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199804001-00231

35. Ng PC, Lee CH, Bnur FL, Chan IH, Lee AW, Wong E, et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled study of a “stress dose” of hydrocortisone for rescue treatment of refractory hypotension in preterm infants. Pediatrics. (2006) 117(2):367–75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0869

36. Noori S, Friedlich P, Wong P, Ebrahimi M, Siassi B, Seri I. Hemodynamic changes after low-dosage hydrocortisone administration in vasopressor-treated preterm and term neonates. Pediatrics. (2006) 118(4):1456–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0661

37. Peeples ES. An evaluation of hydrocortisone dosing for neonatal refractory hypotension. J Perinatol. (2017) 37(8):943–6. doi: 10.1038/jp.2017.68

38. Ramanathan R, Siassi B, Sardesai S. Dexamethasone versus hydrocortisone for hypotension refractory to high dose inotropic agents and incidence of Candida infection in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res. (1996) 39(Suppl 4):240. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199604001-01448

39. Salas G, Travaglianti M, Leone A, Couceiro C, Rodríguez S, Fariña D. Hidrocortisona para el tratamiento de hipotensión refractaria: ensayo clínico controlado y aleatorizado [hydrocortisone for the treatment of refractory hypotension: a randomized controlled trial]. An Pediatr (Barc). (2014) 80(6):387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2013.08.004

40. Verma RP, Dasnadi S, Zhao Y, Chen HH. A comparative analysis of ante- and postnatal clinical characteristics of extremely premature neonates suffering from refractory and non-refractory hypotension: is early clinical differentiation possible? Early Hum Dev. (2017) 113:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.07.010

41. Visveshwara N, Peck M, Wells R, Bansal V, Chopra D, Rajani K. Efficacy of hydrocortisone in restoring blood pressure in infants on dopamine therapy. Pediatr Res. (1996) 39:251. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199604001-01512

42. Mizobuchi M, Yoshimoto S, Nakao H. Time-course effect of a single dose of hydrocortisone for refractory hypotension in preterm infants. Pediatr Int. (2011) 53(6):881–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03372.x

43. Abdul Aziz AN, Thomas S, Murthy P, Rabi Y, Soraisham A, Stritzke A, et al. Early inotropes use is associated with higher risk of death and/or severe brain injury in extremely premature infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2020) 33(16):2751–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1560408

44. Francis GS, Bartos JA, Adatya S. Inotropes. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 63(20):2069–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.016

45. VanValkinburgh D, Kerndt CC, Hashmi MF. Inotropes and vasopressors. [updated 2023 Feb 19]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2023). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482411/# (accessed 5 June 2023).

46. Hotta M, Hirata K, Nozaki M, Mochizuki N, Hirano S, Wada K. Association between amount of dopamine and infections in extremely preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. (2020) 179(11):1797–803. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03676-7

47. Baud O, Maury L, Lebail F, Ramful D, El Moussawi F, Nicaise C, et al. Effect of early low-dose hydrocortisone on survival without bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants (PREMILOC): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. (2016) 387(10030):1827–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00202-6

48. Bonsante F, Latorre G, Iacobelli S, Forziati V, Laforgia N, Esposito L, et al. Early low-dose hydrocortisone in very preterm infants: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neonatology. (2007) 91(4):217–21. doi: 10.1159/000098168

49. Efird MM, Heerens AT, Gordon PV, Bose CL, Young DA. A randomized-controlled trial of prophylactic hydrocortisone supplementation for the prevention of hypotension in extremely low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. (2005) 25(2):119–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211193

50. Watterberg KL, Gerdes JS, Gifford KL, Lin HM. Prophylaxis against early adrenal insufficiency to prevent chronic lung disease in premature infants. Pediatrics. (1999) 104(6):1258–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1258

51. Watterberg KL, Gerdes JS, Cole CH, Aucott SW, Thilo EH, Mammel MC, et al. Prophylaxis of early adrenal insufficiency to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a multicenter trial. Pediatrics. (2004) 114(6):1649–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1159

52. Peltoniemi OM, Lano A, Puosi R, Yliherva A, Bonsante F, Kari MA, et al. Trial of early neonatal hydrocortisone: two-year follow-up. Neonatology. (2009) 95(3):240–7. doi: 10.1159/000164150

53. Trousson C, Toumazi A, Bourmaud A, Biran V, Baud O. Neurocognitive outcomes at age 5 years after prophylactic hydrocortisone in infants born extremely preterm. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2023) 65(7):926–32. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15470

Keywords: neonates, hydrocortisone, shock, clinical practical guidelines, meta-analysis, systematic review

Citation: Ramaswamy VV, Kumar G, Pullattayil S AK, Aradhya AS, Suryawanshi P, Sahni M, Khurana S, Saini SS, K R, Dhir SK, Chawla D, Kumar P and More K (2025) Timing of hydrocortisone therapy in neonates with shock: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline. Front. Pediatr. 13:1491976. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1491976

Received: 5 September 2024; Accepted: 6 February 2025;

Published: 12 March 2025.

Edited by:

Domenico Umberto De Rose, Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Roberto Murgas Torrazza, Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, PanamaCopyright: © 2025 Ramaswamy, Kumar, Pullattayil S, Aradhya, Suryawanshi, Sahni, Khurana, Saini, K, Dhir, Chawla, Kumar and More. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kiran More, ZHJraXJhbm1vcmVAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.