94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pediatr., 03 August 2023

Sec. Pediatric Otolaryngology

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1228737

Background: Allergic rhinitis is a chronic and refractory disease that can be affected by a variety of factors. Studies have shown an association between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis.

Methods: The PubMed, Springer, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases were searched to retrieve all studies published from January 2000 to November 2022, focusing on the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. A meta-analysis was conducted to find a correlation between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. A subgroup analysis was performed, considering the region and family history of allergy, after adjusting for confounding factors. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) were calculated, publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot, and heterogeneity between study-specific relative risks was taken into account.

Results: The results showed that cesarean section was significantly associated with an increased risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.20–1.35). Subgroup analysis stratified by region indicated that cesarean section increased the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis, with the highest increase in South America (OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.10–2.52) and the lowest in Europe (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25). The results of the subgroup analysis stratified by family history of allergy indicate that family history of allergy was not associated with the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis.

Conclusion: An association exists between cesarean section as the mode of delivery and the increased risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis, and cesarean section is a risk factor for allergic rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis is a chronic, non-infectious inflammatory response of the nasal mucosa caused by human exposure to allergens, manifested by symptoms such as itchy nose, sneezing, runny nose, and nasal congestion (1). The global average risk of allergic rhinitis has exceeded 20%, in which studies have reported that the proportion of children may be higher than that of adults (2), the majority of patients have symptoms before the age of 20 years, and nearly half of the patients develop symptoms at the age of 5–6 years in some countries (3, 4). Thus, the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis is worthy of further attention. Medical therapy, specific immunotherapy, and surgery are the most commonly used methods for treating allergic rhinitis, while avoiding risk factors has always been the best option. In recent studies on risk factors for allergic rhinitis (3–5), cesarean section has been suggested as a risk factor for allergic rhinitis, and this method of delivery is significantly related to the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. Moreover, studies have shown that the rate of cesarean section is increasing (6–8), and the majority of countries remarkably exceed the reasonable rate of cesarean section presented by the World Health Organization (WHO) (10%–15%) (9). This finding is closely associated with the improvement of the socioeconomic level, the change in maternal health awareness, and the healthcare level (5, 10). The present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to explore the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children, as the global demand for cesarean section has significantly increased. In addition, Cuppari et al. (11) found that cesarean delivery influences the risk of atopy but does not affect the prevalence of immune sensitization and allergic diseases.

Allergic rhinitis is a chronic and refractory disease that can be caused by a variety of factors. Studies have shown an association between C-sections and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children. In this study, systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to investigate the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children. The results may guide pregnant women to choose their delivery methods, suggesting that choosing a natural delivery may reduce the risk of allergic rhinitis in children, especially in high-risk areas.

The protocol of this meta-analysis was prospectively registered at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#recordDetails(CRD42022378094) on 3 December 2022.

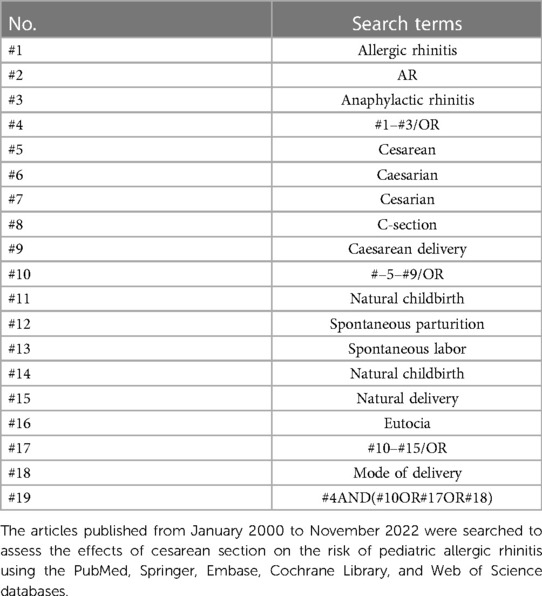

The relationship between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis was explored. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the articles published from January 2000 to November 2022 were searched using the PubMed, Springer, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases to assess the effects of cesarean section on the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. The use of keywords associated with medical subject terms (MeSH) cesarean section and allergic rhinitis was consistent with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Table 1). Specifically, three-word combined strategies were used for conducting the searches: Strategy 1: (cesarean OR caesarian OR cesarian OR C-section OR Caesarean delivery) AND (allergic rhinitis OR AR OR anaphylactic rhinitis); Strategy 2: (natural childbirth OR Spontaneous parturition OR spontaneous labor OR Natural Childbirth OR natural delivery) AND (allergic rhinitis OR AR OR anaphylactic rhinitis); and Strategy 3: Mode of delivery AND (allergic rhinitis OR AR OR anaphylactic rhinitis). Based on the title and abstract of the retrieved articles, their full text was searched if they analyzed the potential association between cesarean section and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children. Their reference lists were checked to search for similar studies before searching using the title and abstract. This process was repeated until no new references could be retrieved. The eligible studies should contain information about relative risk measures [e.g., unadjusted or adjusted odds ratio (aOR)], or information sufficient to calculate such measures (e.g., number of cases and controls based on the mode of delivery).

Table 1. The keywords associated with medical subject terms (MeSH) cesarean section and allergic rhinitis.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) trials of allergic rhinitis in children and diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in accordance with international guidelines; (2) children aged 0–18 years and the availability of detailed statistics of types of childbirth and delivery methods; (3) cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies; (4) data that could be used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effects of air pollutants on allergic rhinitis; and (5) trials published in the English language only, without the need of contacting the authors.

The exclusion criteria included incomplete data and data not accessible from the original author.

Data were initially extracted from the included studies. Then, two reviewers (XH and JW) independently extracted data from those studies, including the first author's name, year of publication, study duration, study type, sample size, diagnostic criteria, outcome evaluation criteria, and study results [data on the relative risk of allergy outcomes, including odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI, if available, and adjusted risk and risk of diagnosis/symptoms]. Discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved after a discussion with a third reviewer (SZ). Furthermore, the data were categorized by region (Asia, Europe, South America, and North America) and whether confounders could be adjusted for subsequent subgroup analysis.

The quality scores used in the meta-analysis were found controversial. Thus, the quality of the included studies and the risk of bias were analyzed. Different assessment scales were used due to the different types of studies included. The included cohort and case–control studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), with a score of 14. Two reviewers (XH and JW) independently assessed the quality of the included cross-sectional studies using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) scaling system (12), with scores of 0–3 indicating low quality, 4–7 moderate quality, and 8–11 high quality. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (SZ). Table 2 presents the results of the evaluation. Of the 21 articles included, one was excluded because of flaws in the study design, and another was excluded due to the large sample size and the serious effect on heterogeneity. Finally, the 19 remaining studies were analyzed, and the sensitivity analysis performed by SPSS software showed that after excluding most of the articles, the pooled results of the remaining studies were statistically significant (95% CI: 1), indicating that the results of the original meta-analysis were not easy to change significantly due to variations in the number of studies, and the results were therefore robust. Two subgroup analyses were also conducted.

The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 software (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK). The OR value of 95% CI was calculated as the effect size. The Cochran Q test and Higgins I2 statistics were used to assess the level of heterogeneity between outcomes. The Q test and I2 statistics were utilized to examine heterogeneity, in which I2 > 50% indicated a significant heterogeneity. A fixed-effects or random-effects model indicated a significant difference in effect size (P < 0.05). The sensitivity analysis of the results and publication bias were evaluated using the leave-one-out and funnel plot techniques, respectively. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart for this meta-analysis. After searching through the proposed search strategy, a total of 1,722 articles were initially retrieved. After removing duplicate studies and reviews, 524 studies were obtained. Next, 481 articles were excluded due to irrelevance after evaluating their titles and abstracts, and the full texts of 43 studies were reviewed. Subsequently, 24 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. As a result, 19 studies were included in the meta-analysis. These 19 studies were published in the English language, including 13 cohort studies and six cross-sectional studies. Among them, 10 studies directly examined the association between cesarean section or different modes of delivery and the risk of allergic rhinitis. Meanwhile, the other nine studies assessed the association between cesarean section or different modes of delivery and allergic disease or asthma, including allergic rhinitis.

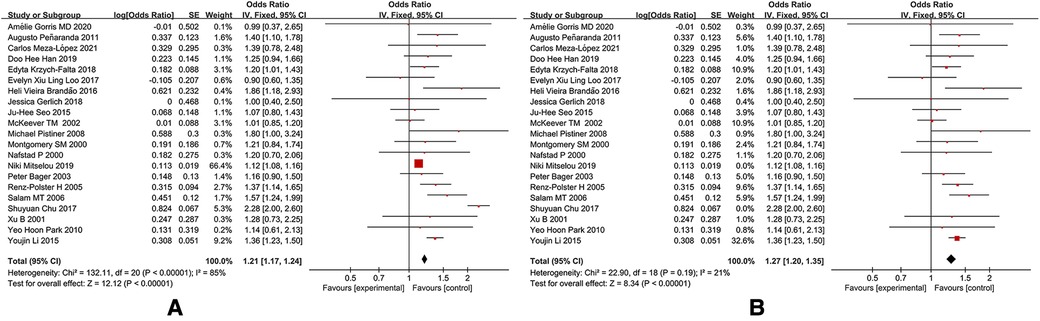

Figure 2 shows the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis in the 19 included studies. Three non-compliant studies were excluded after conducting a quality assessment and sensitivity analysis. The final results showed that cesarean section was significantly associated with the risk of allergic rhinitis in children, and cesarean section was associated with an increased risk of allergic rhinitis in children (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.20–1.35).

Figure 2. A forest plot of cesarean section and AR prevalence in children. (A) Cesarean section and allergic rhinitis in children after 21 articles were included. (B) Cesarean section and allergic rhinitis in children after 2 articles were excluded.

The results of subgroup analysis by region (Asia, Europe, South America, and North America) showed that the risk of allergic rhinitis in children delivered by cesarean section was most increased in South America (13, 14) (OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.10–2.52), followed by North America (15–19) (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.28–1.63), Asia (5, 20–23) (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.18–1.41), and Europe (10, 24–29) (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25), as shown in Figure 3.

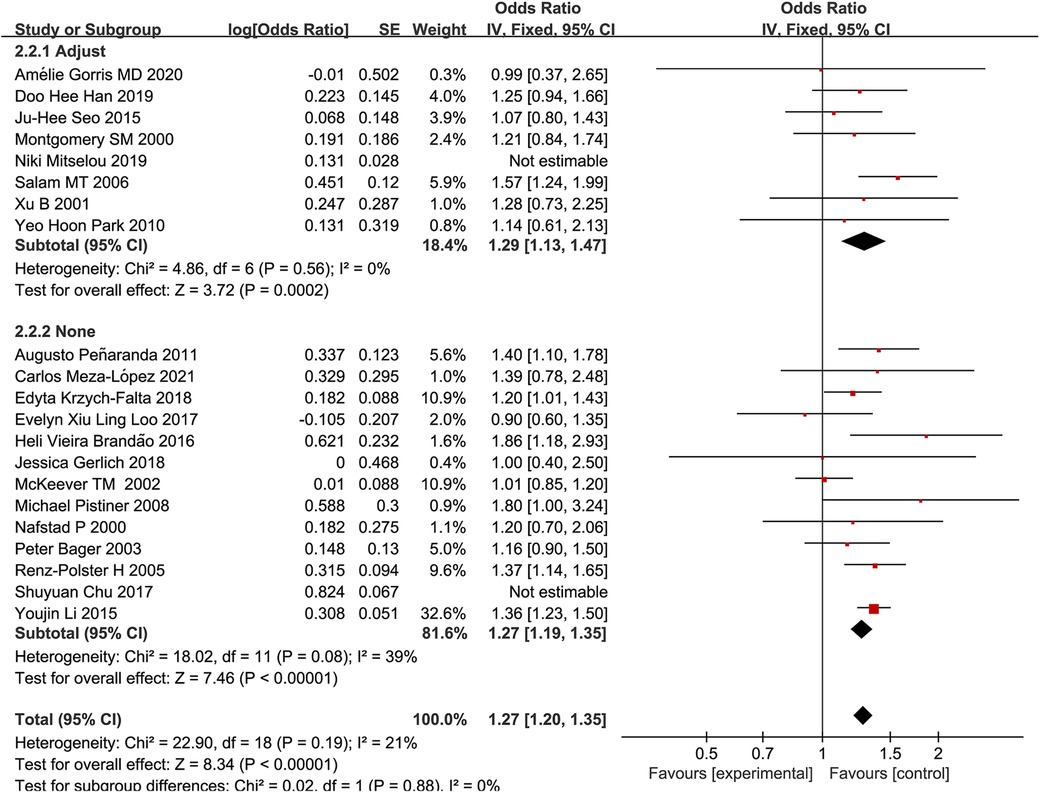

A subgroup analysis based on whether the confounders were adjusted was performed. It was revealed that the overall OR of studies that did not adjust for confounding factors for family history of allergy (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.19–1.35) did not significantly differ from the overall OR of studies that adjusted for confounding factors for family history of allergy (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.13–1.47), as shown in Figure 4, suggesting that there was no significant relationship between family history of allergy and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. This finding contradicts the conclusion in some studies that family history of allergy increased the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis.

Figure 4. A forest plot adjusting for family allergy history confounding factors after cesarean section and the prevalence of AR in children.

We analyzed the publication bias of 19 studies on the relationship between cesarean section and AR risk in children using a funnel plot (Figure 5). The results show that the points are basically symmetric and distributed at the top of the funnel, but one report by McKeever et al. (10) was distributed outside the funnel plot, which may be due to the absence of confounding adjustment or late follow-up.

Allergic rhinitis is a respiratory disease that can be affected by several factors. This meta-analysis examined the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. As a result, the disorder of physiological bacterial colonization in children, especially in the gastrointestinal tract, affects the immune system (30), hinders the transformation of neonatal Th2 to Th1-biased T cell memory (31), and thus causes an increased risk of allergic diseases. Several studies on cesarean section have shown that delivery via cesarean section might increase the risk of allergic diseases, such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, eczema, and food allergies, similar to the results of the present study. However, this was diametrically opposed by the findings of Gorris et al. (13, 21, 32, 33), who demonstrated that no significant relationship exists between delivery via cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. The effect of delivery via cesarean section on allergic rhinitis has remained controversial in recent years, and the differences might be attributed to insufficient sample sizes, dietary differences, weather differences, and exposure levels, indicating the necessity for further research.

The present study analyzed the association between cesarean section delivery patterns and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis after adjusting for confounding factors, such as age, gender, birth weight, passive smoking, feeding patterns in the first 6 months, maternal educational level, household income, and antibiotic exposure. However, due to lacking raw data, adjusting for confounding factors for maternal diseases during pregnancy and family allergy was infeasible. Mitselou et al. (34) categorized the causes of cesarean section into elective labor and emergency delivery and showed that emergency cesarean section increased the risk of allergic rhinitis more than optional cesarean section after adjusting for confounding factors. Emergency cesarean section was mainly associated with maternal morbidity during pregnancy, and some studies have found that pregnancy-associated complications increased the risk of allergic diseases in children and the risk of intrauterine infection (35). Pistiner et al. (17) analyzed study subjects with and without family history of allergy, and the results showed that in children with family history of allergy, cesarean section increased the incidence of allergic rhinitis. In the present study, the included studies were divided into two groups based on whether they adjusted for factors for family history of allergy or not, and a subgroup analysis was performed. It was found that the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis in studies that adjusted for factors for family history of allergy was OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.13–1.47, which was not significantly different from those studies that did not adjust for factors for family history of allergy (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.19–1.35). This result, contrary to recent studies that demonstrated that family history of allergy had an influence on the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis (17, 25, 36), is worthy of further assessment using more research to verify whether allergic genetic predisposition can interact with the effects of cesarean section, making allergic rhinitis more likely to occur in children.

In the present study, subgroup analysis was performed on data stratified by region. For this purpose, four subgroups of Asia, Europe, South America, and North America were considered. The results of subgroup analysis revealed that in Asia (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.18–1.41), Europe (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25), South America (OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.10–2.52), and North America (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.28–1.63), both cesarean delivery methods increased the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis, while OR indicated a different level of risk. The results showed that the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis was the highest in South America and the lowest in Europe. ECRHS reports have also shown that the risk of nasal allergies varies by geographical region (37), which may be related to regional climate and topographic differences, dietary structure, degree of industrialization, etc. (35, 38, 39).

Europe is located in the northeastern hemisphere and has rich fishery resources, and fish has become a very important part of the daily diet. South America is located in the western and southern hemispheres, and due to the climatic and environmental conditions, its animal husbandry is more developed, and the local people mainly consume beef products. Fish has a richer vitamin D content than beef. Previous studies have shown that allergic rhinitis is associated with a reduced vitamin D level (38, 40–42), which can speculate that the European’s preference for eating fish has significantly reduced the risk of allergic pediatric rhinitis. Testa et al. (35) have studied a large number of studies and found that these studies had taken numerous factors into account in a large and representative population, provided that a relationship between dietary nutrition and allergic rhinitis, and improved pediatric eating habits may reduce the risk of allergy symptoms. This study revealed that due to the different dietary patterns in different regions of the world, pediatric intake of nutrients differs, which may result in different incidence rates of allergic rhinitis.

South America is located almost between the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, and its climate is mainly tropical rainforest. Compared with the climate of Europe, the climate of South America is characterized by high temperature, high humidity, and heavy rainfall. Such climatic characteristics have led to differences in mite species and concentrations in different regions, especially in the Andes of Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela, where the prevalence of mites is high (43, 44), and mites are a very important risk factor for allergic rhinitis. Cingi et al. (38) demonstrated that although the overall level of the atopic epidemic did not increase due to climatic factors, climatic changes were related to the variations in the geographical patterns of the atopic epidemic. They also found that the differences in climate between South America and Europe can lead to different effects of cesarean section on the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis.

The risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis from cesarean section is also associated with the degree of industrialization and development of the region. Chou et al. (12) assessed the risk of cesarean section and allergy in children and found a significantly higher risk than that reported in highly industrialized countries. This finding may be related to specific conditions, and the degree of industrialization of a region mainly affects a country's degree of development, economic level, healthcare level, air pollution (45, 46), etc. These factors may influence the maturity of cesarean section, the level of healthcare during production, etc., in the region, resulting in different risk levels in different regions of the world.

The high level of industry in Europe, combined with robust healthcare, a great climate, and a healthy diet containing vitamin D, may explain why cesarean section in Europe is associated with a lower risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis compared with that in other regions.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the few recent meta-analyses that have studied the relationship between cesarean section and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis, and the results were meaningful for both the prevention and selection of delivery methods for pediatric allergic rhinitis. However, the results indicate the necessity of conducting further relevant research. It is noteworthy that the number of relevant studies was limited; thus, additional studies should be performed to clarify the differences in the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis stratified by region. Moreover, the number of research subjects in the included studies remarkably varied. In the present meta-analysis, the majority of the included studies were cross-sectional studies, and patients had recall biases in their memories, demonstrating the necessity of more cohort studies to supplement the findings. At the same time, it is well known that prophylactic antibiotics are usually used to avoid infection after cesarean section, and antibiotic use also exists after some vaginal births. We found that this detail was not documented in the present study, so this factor may influence our analysis results. We need to conduct a long-term cohort study in the future to observe whether using antibiotics after delivery has a certain influence on the early development and health of children.

In summary, the results of the present meta-analysis suggested that the mode of delivery via cesarean section increased the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis after adjusting for confounding factors. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that children in high-risk areas were more affected by cesarean section. In contrast, our experimental results did not support the assumption that family history of allergy increased the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. The results of this study provide some reference value for pregnant women in choosing their delivery method, especially in high-risk areas. However, the final choice of pregnant women is influenced by many factors, and the final mode of delivery should be combined with individual specific circumstances. Further evidence is required to clarify the relationship between family history of allergy and the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis. However, the sample size of the present study was not large enough, it was a retrospective study, and the adjustment of confounding factors was insufficient. Thus, additional studies are required to verify the conclusions.

All the authors conceived the study and drafted the original protocol. XH and JW independently extracted data from studies. XH and JW independently assessed the quality of the included studies. SZ and XH finished writing the original manuscript. QF, QZ, and WP reviewed the overall quality of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was financially supported by Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2022 College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program (Grant No. 202210633023).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

1. Schuler Iv CF, Montejo JM. Allergic rhinitis in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. (2019) 66(5):981–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.06.004

2. Zhang Y, Lan F, Zhang L. Advances and highlights in allergic rhinitis. Allergy. (2021) 76(11):3383–9. doi: 10.1111/all.15044

3. Chu S, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Sun W, Zhu Q, Wang B, et al. Cesarean section without medical indication and risks of childhood allergic disorder, attenuated by breastfeeding. Sci Rep. (2017) 7(1):9762. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10206-3

4. Bager P, Wohlfahrt J, Westergaard T. Caesarean delivery and risk of atopy and allergic disease: meta-analyses. Clin Exp Allergy. (2008) 38(4):634–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02939.x

5. Li Y, Jiang Y, Li S, Shen X, Liu J, Jiang F. Pre- and postnatal risk factors in relation to allergic rhinitis in school-aged children in China. PLoS One. (2015) 10(2):e0114022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114022IF:3.7

6. Ming Y, Li M, Dai F, Huang R, Zhang J, Zhang L, et al. Dissecting the current caesarean section rate in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):2080. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38606-7

7. Lavender T, Hofmeyr GJ, Neilson JP, Kingdon C, Gyte GM. Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) 2012(3):CD004660. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004660

8. Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS One. (2016) 11(2):e0148343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343

9. Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. (2016) 123(5):667–70. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13526

10. McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smith C, Hubbard R. Mode of delivery and risk of developing allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2002) 109(5):800–2. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124046

11. Cuppari C, Manti S, Salpietro A, Alterio T, Arrigo T, Leonardi S, et al. Mode of delivery and atopic phenotypes: old questions new insights? A retrospective study. Immunobiology. (2016) 221(12):1418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.07.003

12. Chou R, Baker WL, Bañez LL, Iyer S, Myers ER, Newberry S, et al. Agency for healthcare research and quality evidence-based practice center methods provide guidance on prioritization and selection of harms in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. (2018) 98:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.007

13. Gorris A, Bustamante G, Mayer KA, Kinaciyan T, Zlabinger GJ. Cesarean section and risk of allergies in Ecuadorian children: a cross-sectional study. Immun Inflamm Dis. (2020) 8(4):763–73. doi: 10.1002/iid3.368

14. Brandão HV, Vieira GO, de Oliveira Vieira T, Camargos PA, de Souza Teles CA, Guimarães AC, et al. Increased risk of allergic rhinitis among children delivered by cesarean section: a cross-sectional study nested in a birth cohort. BMC Pediatr. (2016) 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0594-x

15. Meza-López C, Bedolla-Barajas M, Morales-Romero J, Jiménez-Carrillo CE, Bedolla-Pulido TR, Santos-Valencia EA. Prevalence of allergic diseases and their symptoms in schoolchildren according to the birth mode. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. (2021) 78(2):130–5. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.20000114

16. Penaranda A, Aristizabal G, Garcia E, Vasquez C, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Satizabal CL. Allergic rhinitis and associated factors in schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia. Rhinology. (2012) 50(2):122–8. doi: 10.4193/Rhino11.175

17. Pistiner M, Gold DR, Abdulkerim H, Hoffman E, Celedón JC. Birth by cesarean section, allergic rhinitis, and allergic sensitization among children with a parental history of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2008) 122(2):274–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.007

18. Salam MT, Margolis HG, McConnell R, McGregor JA, Avol EL, Gilliland FD. Mode of delivery is associated with asthma and allergy occurrences in children. Ann Epidemiol. (2006) 16(5):341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.054

19. Renz-Polster H, David MR, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, O’Connor EA, Frazier EA, et al. Caesarean section delivery and the risk of allergic disorders in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. (2005) 35(11):1466–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02356.x

20. Han DH, Shin JM, An S, Kim JS, Kim DY, Moon S, et al. Long-term breastfeeding in the prevention of allergic rhinitis: Allergic Rhinitis Cohort Study for kids (ARCO-kids study). Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. (2019) 12(3):301–7. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2018.01781

21. Loo EXL, Sim JZT, Loy SL, Goh A, Chan YH, Tan KH, et al. Associations between caesarean delivery and allergic outcomes: results from the GUSTO study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2017) 118(5):636–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.02.021

22. Seo JH, Kim HY, Jung YH, Lee E, Yang SI, Yu HS, et al. Interactions between innate immunity genes and early-life risk factors in allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. (2015) 7(3):241–8. doi: 10.4168/aair.2015.7.3.241

23. Park YH, Kim KW, Choi BS, Jee HM, Sohn MH, Kim KE. Relationship between mode of delivery in childbirth and prevalence of allergic diseases in Korean children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. (2010) 2(1):28–33. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.1.28

24. Gerlich J, Benecke N, Peters-Weist AS, Heinrich S, Roller D, Genuneit J, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal conditions and atopic disease prevalence in childhood and adulthood. Allergy. (2018) 73(5):1064–74. doi: 10.1111/all.13372

25. Krzych-Fałta E, Furmańczyk K, Lisiecka-Biełanowicz M, Sybilski A, Tomaszewska A, Raciborski F, et al. The effect of selected risk factors, including the mode of delivery, on the development of allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. (2018) 35(3):267–73. doi: 10.5114/ada.2018.76222

26. Bager P, Melbye M, Rostgaard K, Benn CS, Westergaard T. Mode of delivery and risk of allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2003) 111(1):51–6. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.34

27. Xu B, Pekkanen J, Hartikainen AL, Järvelin MR. Caesarean section and risk of asthma and allergy in adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2001) 107(4):732–3. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.113048

28. Montgomery SM, Wakefield AJ, Morris DL, Pounder RE, Murch SH. The initial care of newborn infants and subsequent hay fever. Allergy. (2000) 55(10):916–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00480.x

29. Nafstad P, Magnus P, Jaakkola JJ. Risk of childhood asthma and allergic rhinitis in relation to pregnancy complications. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2000) 106(5):867–73. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110558

30. Stokholm J, Thorsen J, Chawes BL, Schjørring S, Krogfelt KA, Bønnelykke K, et al. Cesarean section changes neonatal gut colonization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 138(3):881–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.028

31. Björkstén B, Sepp E, Julge K, Voor T, Mikelsaar M. Allergy development and the intestinal microflora during the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2001) 108(4):516–20. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118130

32. Maitra A, Sherriff A, Strachan D, Henderson J. Mode of delivery is not associated with asthma or atopy in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. (2004) 34(9):1349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02048.x

33. Richards M, Ferber J, Li DK, Darrow LA. Cesarean delivery and the risk of allergic rhinitis in children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2020) 125(3):280–6.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.04.028

34. Mitselou N, Hallberg J, Stephansson O, Almqvist C, Melén E, Ludvigsson JF. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk of later allergic rhinitis-nationwide Swedish cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2020) 31(5):471–9. doi: 10.1111/pai.13230

35. Testa D, DI Bari M, Nunziata M, Cristofaro G, Massaro G, Marcuccio G, et al. Allergic rhinitis and asthma assessment of risk factors in pediatric patients: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2020) 129:109759. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109759

36. Baumann LM, Romero KM, Robinson CL, Hansel NN, Gilman RH, Hamilton RG, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for allergic rhinitis in two resource-limited settings in Peru with disparate degrees of urbanization. Clin Exp Allergy. (2015) 45(1):192–9. doi: 10.1111/cea.12379

37. Oliveira TB, Persigo ALK, Ferrazza CC, Ferreira ENN, Veiga ABG. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and pollinosis in a city of Brazil: a monitoring study. Allergol Immunopathol. (2020) 48(6):537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2020.03.010

38. Cingi C, Bayar Muluk N, Scadding GK. Will every child have allergic rhinitis soon? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2019) 118:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.12.019

39. Farrokhi S, Gheybi MK, Movahhed A, Dehdari R, Gooya M, Keshvari S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of asthma and allergic diseases in primary schoolchildren living in Bushehr, Iran: phase I, III ISAAC protocol. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2014) 13(5):348–55.25150076

40. Chen YS, Mirzakhani H, Lu M, Zeiger RS, O'Connor GT, Sandel MT, et al. The association of prenatal vitamin D sufficiency with aeroallergen sensitization and allergic rhinitis in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2021) 9(10):3788–96.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.009

41. Kim YH, Kim KW, Kim MJ, Sol IS, Yoon SH, Ahn HS, et al. Vitamin D levels in allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2016) 27(6):580–90. doi: 10.1111/pai.12599

42. Bhardwaj B, Singh J. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in allergic rhinitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2021) 73(2):152–9. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01907-9

43. Thakur P, Potluri P. Association of serum vitamin D with chronic rhinosinusitis in adults residing at high altitudes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2021) 278(4):1067–74. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06368-y

44. Giraldo-Cadavid LF, Perdomo-Sanchez K, Córdoba-Gravini JL, Escamilla MI, Suarez M, Gelvez N, et al. Allergic rhinitis and OSA in children residing at a high altitude. Chest. (2020) 157(2):384–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.018

45. Zhang Y, Zhang L. Increasing prevalence of allergic rhinitis in China. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. (2019) 11(2):156–69. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.2.156

Keywords: cesarean delivery, pediatric allergic rhinitis, risk factor, meta-analysis, children

Citation: He X, Zhang S, Wu J, Fu Q, Zhang Q and Peng W (2023) The global/local (limited to some regions) effect of cesarean delivery on the risk of pediatric allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 11:1228737. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1228737

Received: 25 May 2023; Accepted: 17 July 2023;

Published: 3 August 2023.

Edited by:

Hideyuki Kawauchi, Shimane University, JapanReviewed by:

Meresa Berwo Mengesha, Adigrat University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ethiopia© 2023 He, Zhang, Wu, Fu, Zhang and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qinxiu Zhang emhxaW54aXVAMTYzLmNvbQ== Wenyu Peng NjQ0ODk0MDk3QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.