95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Pediatr. , 26 July 2023

Sec. Pediatric Oncology

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1212711

Egle Stukaite-Ruibiene1*†

Egle Stukaite-Ruibiene1*† M. E. Madeleine van der Perk2,†

M. E. Madeleine van der Perk2,† Goda Elizabeta Vaitkeviciene1,3

Goda Elizabeta Vaitkeviciene1,3 Annelies M. E. Bos2

Annelies M. E. Bos2 Zana Bumbuliene1,4

Zana Bumbuliene1,4 Marry M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink2,†

Marry M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink2,† Jelena Rascon1,3,†

Jelena Rascon1,3,†

Background: The 5-year survival rate of childhood cancer exceeds 80%, however, many survivors develop late effects including infertility. The aim of this study was to evaluate the current status of oncofertility care at Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos (VULSK) within the framework of the EU-Horizon 2020 TREL project.

Methods: All parents or patients aged 12–17.9 years treated from July 1, 2021 until July 1, 2022 were invited to complete an oncofertility-care-evaluation questionnaire. After completing the questionnaire, patients were triaged to low-risk (LR) or high-risk (HR) of gonadal damage using a risk stratification tool (triage). Data was assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results: Questionnaires were completed by 48 parents and 13 children triaged as 36 (59%) LR and 25 (41%) HR patients. Most HR respondents (21/25, 84%) were not counseled by a fertility specialist. Six boys (4 HR, 2 LR) were counseled, none of the girls was counseled. Three HR boys underwent sperm cryopreservation. Only 17 (27.9%, 9 HR, 8 LR) respondents correctly estimated their risk. All counseled boys (n = 6) agreed the risk for fertility impairment had been mentioned as compared to 49.1% (n = 27) of uncounseled. All counseled respondents agreed they knew enough about fertility (vs. 42%).

Conclusions: Respondents counseled by a fertility specialist were provided more information on fertility than uncounseled. HR patients were not sufficiently counseled by a fertility specialist. Based on the current experience oncofertility care at VULSK will be improved.

Currently, the 5-year survival rate of patients with childhood cancer exceeds 80%, leading to an increase in the number of childhood cancer survivors (CCS) (1, 2). However, cancer treatment can lead to multiple late toxicities, including gonadal damage and fertility impairment (3–5). Female CCS are at risk for premature ovarian insufficiency, follicular atresia, premature menopause, and infertility, especially after treatment such as alkylating agents and radiotherapy (RT) (6, 7). For male CCS, late effects of chemotherapy or RT to the testes or the hypothalamic–pituitary axis can manifest as hypogonadism and impaired spermatogenesis (8, 9). Fertility is a critical component of life in young CCS, and impaired fertility is associated with reduced long-term quality of life (10, 11). Awareness of potential gonadal damage is crucial for shared decision-making to prevent infertility. Thus, appropriate information and counseling of patients and their caregivers become critical to prevent frustration because of the lack of information.

The International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group (IGHG) recommends informing all patients with childhood cancer about their gonadal damage risk and offering fertility counseling to those at risk (12–14). However, implementing these recommendations in clinical practice is challenging. Only a well-established institutional oncofertility care system can ensure timely and adequate counseling of patients with childhood cancer and their caregivers. A five-step oncofertility care plan following IGHG recommendations was developed by the Princess Máxima Center, Netherlands, in 2019 (15). The oncofertility care plan includes the following steps: (1) timely identification of all patients newly diagnosed with childhood cancer, (2) gonadal damage risk stratification using a risk-stratification tool, (3) informing all patients on personal gonadal damage risk (pediatric oncologist or nurse practitioner), (4) counseling the subset at risk (fertility specialist), and (5) offering fertility preservation to children with high gonadal damage risk (HGDR) (15).

The aforementioned oncofertility care plan served as an example to implement IGHG guidelines and improve oncofertility care at the Center for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology of Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos (VULSK, Lithuania) through a twinning exercise with the Princess Máxima Center within an EU-Horizon 2020-funded project “Twinning in Research and Education to Improve Survival in Childhood Solid Tumors in Lithuania (TREL).” The project aims to foster research on different aspects of pediatric cancer including survivorship (https://siope.eu/TREL-project). A previous cross-sectional study revealed that a majority of adult CCS treated at VULSK had limited knowledge about reproductive health and had not received sufficient information regarding fertility (16). These findings mirror the results of other research groups, suggesting that patients with childhood cancer are not always properly counseled about the effects of cancer treatment on reproductive health (17, 18) or even do not know their fertility status (19).

This study aimed to evaluate the quality of informing and counseling before implementing the oncofertility care plan in an independent cohort of patients with childhood cancer treated at VULSK using an amended version of the tools developed by the Princess Máxima Center—the oncofertility-care-evaluation questionnaires and the gonadal damage risk-stratification tool (triage). We pursued to assess the awareness of patients with childhood cancer or their caregivers of their infertility risk and its compliance with the individual gonadal damage risk assessed by the triage. The results of this study will serve as a baseline for future research.

First, the oncofertility-care-evaluation questionnaire developed by the Princess Máxima Center was adapted for Lithuanian patients (20). Two questionnaires were used: one for patients counseled by a fertility specialist, and another for those informed by a pediatric oncologist. The questionnaires used a 5-point Likert scale. The design of both questionnaires had been previously published (20). Briefly, the questionnaires were based on multiple validated questionnaires concerning decision regret, reproduction concern, and evaluation of fertility care in an adult setting (21–24). The questions were translated from Dutch to English and afterward from English to Lithuanian. To validate the Lithuanian translation, the reverse translation from Lithuanian to English was performed. No significant discrepancies between the wordings were found. The Lithuanian version was reviewed by two pediatric oncologists, a gynecologist, two patients, and parents, who were all native Lithuanian speakers and fluent in English. Lastly, the Lithuanian version was compared with the Dutch version with help of the English translation by a native Dutch-speaking author. The respondents received the Lithuanian version (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). The English version of the questionnaires is provided in Supplementary Tables S3, S4.

Second, the original gonadal damage risk-stratification tool (triage) used in the Netherlands was amended by the replacement of the treatment protocols that differed between the two institutions (Supplementary Table S5). All protocols and treatment arms used at VULSK were reviewed and included in the amended version, whereas protocols that were only used at the Princess Maxima Center were removed from the amended tool.

In addition, the gonadal damage risk for boys was added to the amended tool because the original version focused on girls only (15). Gonadal damage risk for boys was defined according to the recently published IGHG guidelines (14). The risk of gonadal damage was assessed according to the Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) originally developed by Green et al. (25). The CED scores were classified as low gonadal damage risk (LGDR) (<4,000 mg/m2) and HGDR (>6,000 mg/m2) for girls (26) and LGDR (<4,000 mg/m2) or HGDR (≥4,000 mg/m2) for boys (26) (Supplementary Table S5). In the original tool, intermediate gonadal damage risk for girls was defined; however, after the amendment, the gonadal damage risk for girls was classified as low or high according to the newest recommendations (13). In addition, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, total body irradiation, and RT to the gonads upgrade toward HGDR for boys and girls (13, 14). Boys aged >12 years and Tanner stage >G2P2 should be offered semen cryopreservation (14). All changes from the original gonadal damage risk-stratification tool are summarized in Supplementary Table S6.

All parents of patients with childhood cancer (irrespective of the child's age) or patients aged 12–17.9 years treated for pediatric cancer (ICD-10-AM C00-96) between July 1, 2021, and July 1, 2022, were invited to participate in the study. Patients were identified in the institutional database. All patients diagnosed within the evaluation period and those diagnosed previously but still undergoing treatment were invited.

Baseline characteristics including the age at diagnosis, time from the date of diagnosis to enrollment, malignancy type, and treatment (protocol and arm) were retrieved from the medical records. As recorded in the patient files, the date of diagnosis was defined as the date of communicating the cancer diagnosis by a pediatric oncologist to the family.

Participants were divided into two groups: a group counseled by a fertility specialist and a group informed by a pediatric oncologist. Before the start of treatment, every patient received written information on potential risk for fertility impairment (without pointing out a specific individual gonadal damage risk) during the provision of information on chemotherapy and its potential side effects. Thus, all participants not counseled by a fertility specialist were considered informed about the risk for infertility by a pediatric oncologist.

Fertility counseling and fertility preservation were both provided before chemotherapy to all patients at the Santaros Fertility Center, a specialized unit at VULSK. Pubescent boys were counseled by an embryologist based on the results of the semen analysis. During the evaluation period, fertility preservation was only allowed for children aged ≥14 years according to the Lithuanian Law for Assisted Reproduction (26). Therefore, prepubescent girls and boys and their parents were not offered fertility preservation. In cases of fertility preservation, sperm samples were obtained by masturbation, and sperm cryopreservation was performed. If fertility preservation is needed in girls, they are counseled by a gynecologist at VULSK.

A cross-sectional survey within the previously specified timeframe was performed. All participants completed the oncofertility-care-evaluation questionnaire. All patients were already receiving treatment when the questionnaire was handed in, no questionnaires were given between diagnosis and treatment initiation. The questionnaire was completed during the inpatient stay or the scheduled outpatient visit. Questionnaires were completed separately by patients or their parents, and no parent–child combinations were included. As mentioned above, two questionnaires were used: one for patients counseled by a fertility specialist (counseled group), and another for those informed by a pediatric oncologist alone (uncounseled group). The responses were evaluated in July 2022. The responses of the counseled group opposed those of the uncounseled group. The responses to each question were analyzed, and the frequencies of the responses were calculated.

The respondents were also asked to self-estimate their specific risk for infertility. Thereafter, each response was compared with the infertility risk assessment provided by the study team using the above-mentioned risk-stratification tool.

After completing the questionnaires, the respondents were retrospectively triaged to LGDR or HGDR using the amended version of the gonadal damage risk-stratification tool. Data were analyzed in September 2022.

Descriptive statistics were used for all quantitative analyses. The normality of the distribution of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test and expressed as medians with interquartile (IQR) and minimal–maximal ranges. SPSS Statistics version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all quantitative analyses.

In total, 126 patients were invited to participate in the study that evaluated the existing oncofertility (Figure 1). Of the 126 patients, 61 (48.4%) signed the informed consent and were included in the study. All respondents (n = 61) completed the oncofertility-care-evaluation questionnaire. More than half of the invited patients (65/126, 51.6%) refused to participate without specifying the reason for refusal. Therefore, their data were not analyzed.

Overall, the questionnaires were completed by 48 parents and 13 children. After completing the questionnaires, the respondents were retrospectively triaged by the study team as 36 LGDR and 25 HGDR. More than half (n = 16, 64%) of all HGDR patients were boys and 9 (36%) were girls. Of all 61 respondents, 6 (9.8%) boys were assigned to the counseled group (Figure 1). They were counseled by a fertility specialist (embryologist) before the initiation of cancer treatment, and all completed the questionnaire themselves. After completing the questionnaire, the counseled boys were retrospectively classified as 4 HGDR and 2 LGDR. In the three counseled HGDR boys, normospermia was observed, and sperm cryopreservation was performed. Three boys (2 LGDR, 1 HGDR) did not manage to collect a sperm sample, probably because of their young age.

Of the 21 HGDR respondents in the uncounseled group, 15 (71.4%) were <14 years old; therefore, fertility preservation was not an option as per the legal framework enforced at the time of the study. However, fertility preservation was not offered to six HGDR respondents aged >14 years. Two of them were diagnosed before this study, and three HGDR boys and one HGDR girl aged ≥14 years were diagnosed during the evaluation period.

In the uncounseled group, 55 respondents (48 parents and 7 children) completed the questionnaire (Figure 1). Of these 55 uncounseled respondents, 21 were retrospectively triaged as HGDR and 34 as LGDR. All 55 uncounseled respondents were informed about a potential risk (without pointing out a specific risk) for infertility when consenting to chemotherapy before treatment initiation.

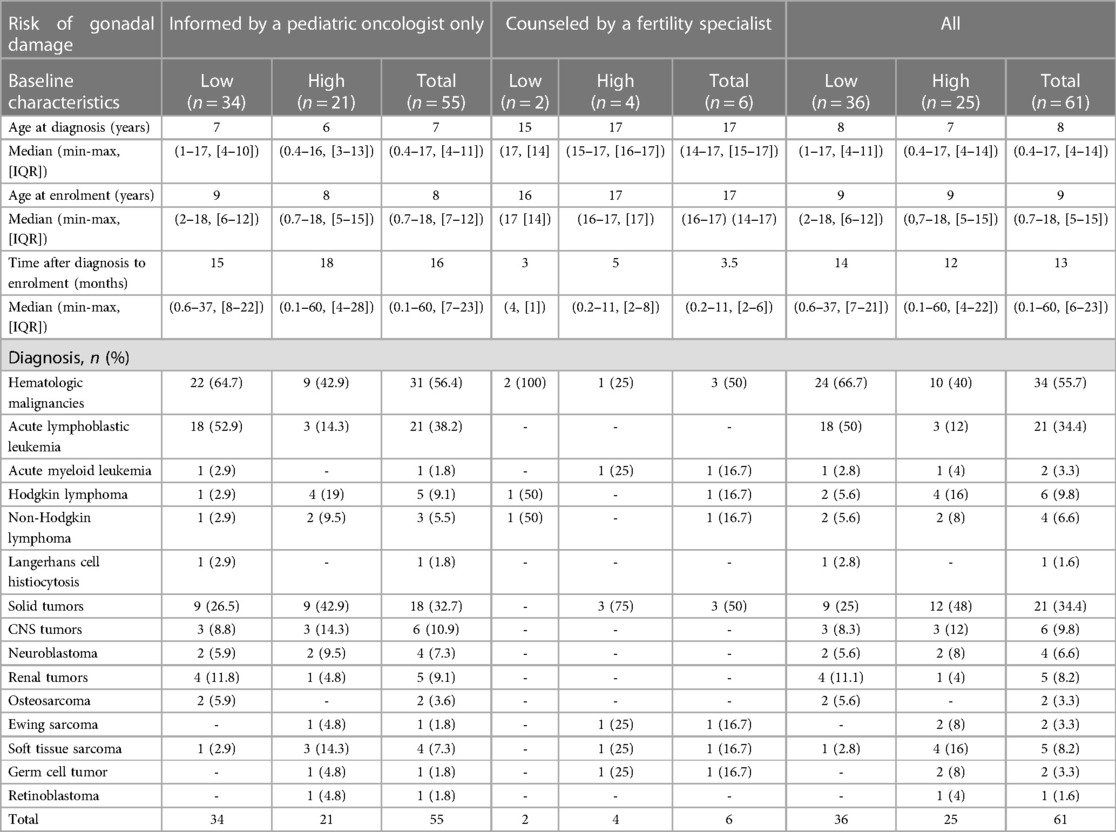

The median age of the respondents at the time of diagnosis was 8 (IQR 4–11) years, which ranged from 3 months to 17 years (Table 1). The median time after diagnosis to enrollment was 16 (IQR 7–23) months in the uncounseled group and 3.5 (IQR 2–6) months in the counseled group. The most common diagnoses were acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in 21 (34.4%) cases, followed by central nervous system (CNS) tumors in 6 (9.8%), and Hodgkin's lymphoma in 6 (9.8%).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants according to gonadal damage risk group and diagnosis.

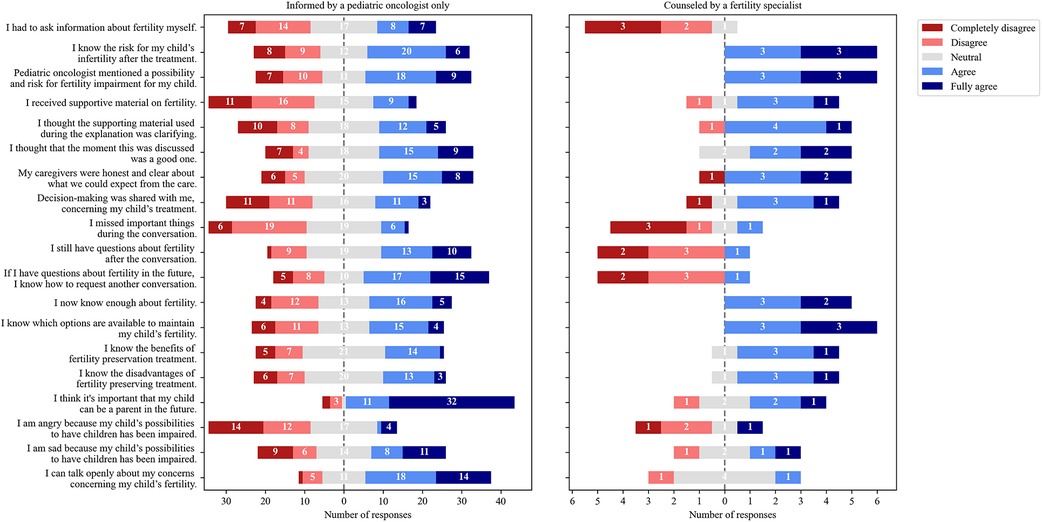

The counseled group (n = 6, 4 HGDR, 2 LGDR) indicated more often that they were provided more information on fertility than the uncounseled group (n = 55, 21 HGDR, 34 LGDR) (Figure 2). All six counseled boys stated that the risk for fertility impairment was mentioned compared with 49.1% of uncounseled respondents (n = 27). The counseled group reported that they now know enough about fertility (vs. n = 21, 42%) and knew options for fertility preservation (vs. n = 19, 38.8%). Only 10/55 (19.2%) of uncounseled respondents received supportive material on fertility (vs. n = 4, 66.7% counseled). All responses of the uncounseled and counseled groups are provided in Supplementary Figures S1, S2.

Figure 2. Distribution of answers of respondents informed by a pediatric oncologist only (n = 55) and those additionally counseled by a fertility specialist (n = 6).

Quite a few (31/61, 50.8%) respondents commented to the open question, “What time do you think is the best time to have a conversation about fertility?” Most respondents (27/31, 87.1%) answered that fertility should be discussed before initiating cancer treatment. Four uncounseled respondents (2 HGDR, 2 LGDR) thought the best time would be after the treatment. Some (17/55, 30.9%) uncounseled respondents stated they never had a conversation about fertility.

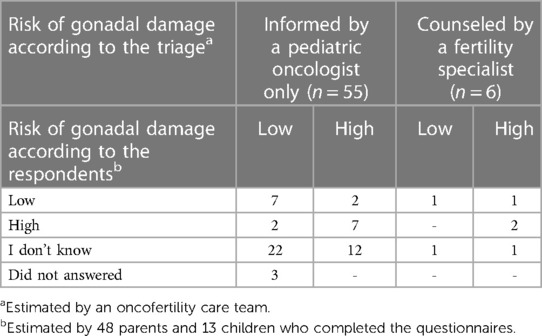

The majority (44/61, 72.2%) of respondents could not correctly self-estimate their specific gonadal damage risk in comparison with the risk allocated by the study team (Table 2). In total, only 17/61 (27.9%) respondents correctly estimated their gonadal damage risk (9 HGDR, 8 LGDR). Of the uncounseled respondents, 22/55 (40%) reported that they do not know their risk, whereas 14/55 (25.5%) correctly estimated their risk. Interestingly, only three counseled boys (2 HGDR, 1 LGDR) correctly estimated their risk.

Table 2. Comparison of the gonadal damage risk estimated by the gonadal damage risk-stratification tool (triage) and gonadal damage risk according to the respondents (self-evaluation).

The increasing number of CCS raises the need for focusing the research on the late effects of cancer treatment and the well-being of CCS. Gonadal damage risk and fertility counseling have beneficial effects on the quality of life of CCS regardless of the decision on fertility preservation (27, 28). Thus, gonadal toxicity must be discussed before the initiation of any therapy (29–32). In our previous cross-sectional study, a majority of adult CCS who were in a long-term remission (age 18+ years as of December 2016) treated at VULSK had limited knowledge about reproductive health and did not receive sufficient information regarding fertility (16). At the time of this previous study patients did not get any information on fertility damage mostly because survival rate was quite low and long-term treatment effects were not a primary concern. Besides, fertility preservation at that time was not possible. From the previous study, we learned that potential azoospermia after high alkylating agents dosages should imply semen preservation before treatment (16). The results prompted the initiation of counseling on fertility damage (6 boys were counseled in this study) and building up the fertility preservation services (performed for 4 boys in this study) (Figure 1). As it was started to provide fertility care, an evaluation of what patients consider appropriate care, including the effect of receiving information and counseling toward fertility preservation, is essential to improve oncofertility care and the quality of life of CCS.

To achieve an essential breakthrough in oncofertility and survivorship care at VULSK, research collaboration with Princess Máxima Center was initiated as part of the EU-funded HORIZON 2020 twinning project TREL. As previously mentioned, a five-step oncofertility care plan launched at the Princess Máxima Center in 2019 served as a model (15). Until recently, fertility information and counseling lacked a systematic approach. Patients were referred to a fertility specialist sporadically when high infertility risk was suspected as there were no tools developed for the evaluation of infertility risk. Moreover, there were no strict selection criteria for referral to a specialist counseling. Therefore, a slightly amended oncofertility care plan was implemented at VULSK in July 2022. Fertility preservation is quite a new topic in Lithuania as the Law for Assisted Reproduction was only adopted in 2017 (26).

During the evaluation of oncofertility care, the most common tumors of the study participants were ALL, CNS tumors, and lymphomas (Table 1), reflecting the international incidence of childhood cancer (33). Boys were more frequently stratified as having HGDR than girls (Figure 1). This is an expected finding because a lower dose of alkylating agents (4,000 mg/m2) leads to HGDR for boys compared with girls (26, 26).

All respondents were triaged retrospectively, i.e., after completing the questionnaire. However, triaging and informing patients about their specific gonadal damage risk are recommended before the start of cancer treatment. However, this is not feasible for some cancer types, e.g., most patients with ALL are assigned to a risk-appropriate treatment arm after the induction therapy (15). The gonadotoxic treatment has already been initiated before the definitive treatment intensity is known. Thus, the application of the timely triage definition to patients with ALL, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in clinical practice is challenging. These patients should be informed about a potential gonadal damage risk before the treatment. However, the definitive triage should be postponed until complete remission or treatment arm allocation because the final intensity of the front-line treatment in hematologic malignancies is assigned after the induction therapy. In patients with renal tumors, delaying the triage after surgery when definitive treatment stratification, including optional RT, will be determined would be beneficial.

In this study, only six (4 HGDR, 2 LGDR) boys were counseled by a fertility specialist (Figure 1). As mentioned above, the counseling and fertility preservation rate was low because, at the time of the evaluation, fertility preservation was only allowed for children aged ≥14 years according to the Lithuanian legislation (26). Fortunately, the legal basis was changed on July 1, 2022, and currently, fertility-preservation options are available to all children irrespective of age. As recommended, we aimed to offer sperm cryopreservation to all postpubertal and pubertal boys aged ≥14 years diagnosed with childhood cancer (26). The procedure is quite simple and non-invasive and does not postpone the cancer treatment (34). In addition, previous reports have shown that sperm cryopreservation in male adolescents with childhood cancer is underused (35). Contrastingly, harvesting testicular tissue for cryopreservation is still considered an experimental technique (26). Moreover, there is a high risk of reintroducing cancer cells during autotransplantation in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma, NHL, ALL, and AML (36, 37). At present, ovarian tissue cryopreservation is considered standard care for prepubertal and peripubertal girls (15, 38). However, future autotransplantation of ovarian tissue from children is still being investigated and considered experimental (39). Oocyte cryopreservation is another established method for fertility preservation in postpubertal girls and young female adults; nevertheless, it could delay the initiation of cancer treatment (26). This was the reason why an HGDR girl aged ≥14 years diagnosed during the evaluation period was not counseled by a gynecologist. However, after the implementation of the oncofertility care plan, all girls at VULSK will be offered the possibility of fertility preservation as recommended (26).

The self-evaluation exercise revealed that the majority (36/61, 59%) of the respondents did not know their specific gonadal damage risk (Table 2). All counseled respondents (n = 6) shared that they know enough about fertility (Figure 2); however, only 3/6 (50%) correctly estimated their risk (Table 2). Results suggest that the gonadal damage risk should be communicated to the patients more clearly and even repeatedly. Of the uncounseled respondents, 27/55 (49.1%) stated that a possibility and risk for fertility impairment was mentioned compared all counseled respondents (Figure 2). Approximately a third of uncounseled respondents stated they did not have a conversation about fertility at all. As mentioned, during this study, all patients received written information on potential side effects of treatment, and gonadal damage was mentioned along with other potential toxicities. The statement that fertility was not mentioned should be interpreted carefully because studies have shown that patients and parents do not remember all the information provided during stressful situations and only 20% of information is possibly retained (40, 41). In addition, the median time after diagnosis to enrollment was longer for the uncounseled respondents than for the counseled ones (16 vs. 3.5 months) (Table 1). Considering that time had elapsed, uncounseled respondents had probably forgotten some information. In addition, results revealed a lack of provision of supportive materials, and only 10/55 (19.2%) uncounseled respondents reported that they received supportive material (Figure 2). Thus, informative leaflets were produced, which will be handed out to every patient.

According to the IGHG guidelines, a pediatric oncologist, endocrinologist, fertility specialist, or a specialized nurse may conduct fertility counseling (26). Our results confirm again that counseling by a fertility specialist differs from informing by a pediatric oncologist, and in high-risk patients, after being informed, counseling by an expert must be considered (Figure 2). However, in this study, counseled respondents included boys only.

The low total number of respondents and counseled respondents could be a major study limitation. The number of study participants reflects the annual patient volume at VULSK, i.e., approximately 50–60 new patients with childhood cancer are diagnosed and treated annually (there are two pediatric oncology centers in Lithuania for the 2.8 million population) (20). Considering the low number of patients, all patients who were treated during the evaluation period were invited to participate, including both new and previously diagnosed patients. On account of the low number of respondents, only a descriptive data analysis was conducted because the results of statistical tests could be misleading. Responses of parents versus patients and boys versus girls were not compared. Only half of the invited patients (61/126, 48.4%) agreed to participate in the study. Therefore, response bias is probably, e.g., patients who were provided enough information regarding reproductive health refused to participate. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzed how patients with childhood cancer and their parents experience fertility care, being a strength of this study.

The results of this study revealed that fertility care for patients with childhood cancer can be quite difficult in clinical practice. Results revealed a need for daily identification, coordination, and documentation of newly diagnosed, timely triaged, and informed patients. Therefore, the oncofertility care plan was implemented at VULSK using an adapted risk-based oncofertility care system, and its systematic evaluation was implemented at the Princess Máxima Center. Therefore, the experience of fertility care from the points of view of the patients and parents could be compared between the two centers.

This study contributed to the awareness of pediatric oncologists of the gonadal damage risk and facilitated referral to a fertility specialist. The study provides insight to further oncofertility care practice, and the results will contribute to the enhancement of fertility care and possibly aid in improving the quality of life of CCS. The oncofertility care at VULSK will be reevaluated after the implementation of the oncofertility care plan. The twinning activities between the two institutions contributed to the reduction of disparities in oncofertility care and research.

The existing system of informing patients on gonadal damage risk, along with all other potential side effects of chemotherapy, must be improved. Counseling of children at HGDR by a fertility specialist is important and appears more efficient than informing by a pediatric oncologist, only providing adequate information. The absence of systematic gonadal damage risk stratification before treatment initiation and former restrictions in the Lithuanian legal framework jeopardized sufficient patient empowerment regarding their fertility-preservation options. These baseline results will be used to compare oncofertility care before and after the implementation of the oncofertility care plan. The oncofertility care plan established by the Princess Máxima Center was adopted and is in the process of implementation at VULSK as a part of the twinning project TREL, which will contribute to the reduction of disparities in oncofertility care and research.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Vilnius Regional Committee of Biomedical Research. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

ES-R, MP, JR, and MH-E designed the study and wrote the manuscript. ZB, GV, and AB made suggestions to improve the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed the final article for intellectual content. In all, this document represents a fully collaborative work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The TREL project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Grant Agreement No 952438. Authors ES-R and JR was also funded by The Research Council of Lithuania, project registration number P-SV-22-252.

We are grateful to the staff from all research centers involved in this study and the TREL project. The Twinning project TREL is a collaborative project, supported by the Horizon 2020 initiative of the European Commission. Funded by H2020-EU.4.b, Grant agreement ID: 952438. The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.com) for the English language review.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2023.1212711/full#supplementary-material

1. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. (2014) 64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219

2. Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007: results of EUROCARE-5–a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. (2014) 15:35–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70548-5

3. Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, Baassiri M, Eissa H, Yeo F, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. Lancet. (2017) 390:2569–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31610-0

4. Mostoufi-Moab S, Seidel K, Leisenring WM, Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Stovall M, et al. Endocrine abnormalities in aging survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:3240–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.6545

5. Overbeek A, van den Berg MH, Kremer LCM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Tissing WJE, Loonen JJ, et al. A nationwide study on reproductive function, ovarian reserve, and risk of premature menopause in female survivors of childhood cancer: design and methodological challenges. BMC Cancer. (2012) 12:363. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-363

6. Anderson RA, Mitchell RT, Kelsey TW, Spears N, Telfer EE, Wallace WHB. Cancer treatment and gonadal function: experimental and established strategies for fertility preservation in children and young adults. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2015) 3:556–67. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00039-X

7. van Dorp W, Haupt R, Anderson RA, Mulder RL, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, et al. Reproductive function and outcomes in female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:2169–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3441

8. Skinner R, Mulder RL, Kremer LC, Hudson MM, Constine LS, Bardi E, et al. Recommendations for gonadotoxicity surveillance in male childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group in collaboration with the PanCareSurFup consortium. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:e75–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30026-8

9. Lee SH, Shin CH. Reduced male fertility in childhood cancer survivors. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (2013) 18:168–72. doi: 10.6065/apem.2013.18.4.168

10. van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJL, van Dam EWCM, Braam KI, Huisman J. Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. (2008) 17:506–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.1274

11. Langeveld NE, Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2002) 10:579–600. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0388-6

12. Mulder RL, Font-Gonzalez A, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Quinn GP, Ginsberg JP, Loeffen EAH, et al. Communication and ethical considerations for fertility preservation for patients with childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: recommendations from the PanCareLIFE consortium and the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:e68–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30595-7

13. Mulder RL, Font-Gonzalez A, Hudson MM, van Santen HM, Loeffen EAH, Burns KC, et al. Fertility preservation for female patients with childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: recommendations from the PanCareLIFE consortium and the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:e45–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30594-5

14. Mulder RL, Font-Gonzalez A, Green DM, Loeffen EAH, Hudson MM, Loonen J, et al. Fertility preservation for male patients with childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: recommendations from the PanCareLIFE consortium and the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:e57–67. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30582-9

15. van der Perk MEM, van der Kooi ALF, van de Wetering MD, IJgosse IM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Broer SL, et al. Oncofertility care for newly diagnosed girls with cancer in a national pediatric oncology setting, the first full year experience from the Princess Máxima center, the PEARL study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0246344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246344. eCollection 202133667234

16. Stukaite-Ruibiene E, Jurkonis M, Adomaitis R, Bumbuliene Z, Gudleviciene Z, Verkauskas G, et al. A crosscut survey on reproductive health in Lithuanian childhood cancer survivors. Ginekol Pol. (2021) 92:262–70. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2021.0027

17. Terenziani M, Spinelli M, Jankovic M, Bardi E, Hjorth L, Haupt R, et al. Practices of pediatric oncology and hematology providers regarding fertility issues: a European survey. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2014) 61:2054–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25163

18. Köhler TS, Kondapalli LA, Shah A, Chan S, Woodruff TK, Brannigan RE. Results from the survey for preservation of adolescent reproduction (SPARE) study: gender disparity in delivery of fertility preservation message to adolescents with cancer. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2011) 28:269–77. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9504-6

19. Lehmann V, Keim MC, Nahata L, Shultz EL, Klosky JL, Tuinman MA, et al. Fertility-related knowledge and reproductive goals in childhood cancer survivors: short communication. Hum Reprod. (2017) 32:2250–3. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex297

20. van der Perk MEM, Stukaitė-Ruibienė E, Bumbulienė Ž, Vaitkevičienė GE, Bos AME, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, et al. Development of a questionnaire to evaluate female fertility care in pediatric oncology, a TREL initiative. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:450. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09450-2

21. Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. (2003) 23:281–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005

22. O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. (1995) 15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105

23. Garvelink MM, ter Kuile MM, Louwé LA, Hilders CGJM, Stiggelbout AM. Validation of a Dutch version of the reproductive concerns scale (RCS) in three populations of women. Health Care Women Int. (2015) 36:1143–59. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.993036

24. van Empel IWH, Aarts JWM, Cohlen BJ, Huppelschoten DA, Laven JSE, Nelen WLDM, et al. Measuring patient-centredness, the neglected outcome in fertility care: a random multicentre validation study. Hum Reprod. (2010) 25:2516–26. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq219

25. Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, Whitton JA, Srivastava D, Leisenring WM, et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure. A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2014) 61:53–67. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24679

26. XII-2608 Lietuvos Respublikos pagalbinio apvaisinimo įstatymas. Available at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/f31c44c27bd711e6a0f68fd135e6f40c (Accessed October 10, 2022).

27. Deshpande NA, Braun IM, Meyer FL. Impact of fertility preservation counseling and treatment on psychological outcomes among women with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. (2015) 121:3938–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29637

28. Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Katz A, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, et al. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer. (2012) 118:1710–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26459

29. Lambertini M, Del Mastro L, Pescio MC, Andersen CY, Azim HA, Peccatori FA, et al. Cancer and fertility preservation: international recommendations from an expert meeting. BMC Med. (2016) 14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0545-7

30. Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 31:2500–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678

31. Peccatori FA, Azim HA, Orecchia R, Hoekstra HJ, Pavlidis N, Kesic V, et al. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:vi160–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt199

32. Martinez F, International Society for Fertility Preservation–ESHRE–ASRM Expert Working Group. Update on fertility preservation from the Barcelona international society for fertility preservation-ESHRE-ASRM 2015 expert meeting: indications, results and future perspectives. Fertil Steril. (2017) 108:407–415.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.024

33. Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, Moreno F, Dolya A, Bray F, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:719–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30186-9

34. Klosky JL, Randolph ME, Navid F, Gamble HL, Spunt SL, Metzger ML, et al. Sperm cryopreservation practices among adolescent cancer patients at risk for infertility. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2009) 26:252–60. doi: 10.1080/08880010902901294

35. Glaser AW, Phelan L, Crawshaw M, Jagdev S, Hale J. Fertility preservation in adolescent males with cancer in the United Kingdom: a survey of practice. Arch Dis Child. (2004) 89:736–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.042036

36. Pacheco F, Oktay K. Current success and efficiency of autologous ovarian transplantation: a meta-analysis. Reprod Sci. (2017) 24:1111–20. doi: 10.1177/1933719117702251

37. Dolmans M-M, Luyckx V, Donnez J, Andersen CY, Greve T. Risk of transferring malignant cells with transplanted frozen-thawed ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. (2013) 99:1514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.027

38. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address:YXNybUBhc3JtLm9yZw==. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. (2019) 112:1022–33. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013

39. Anderson RA, Baird DT. The development of ovarian tissue cryopreservation in Edinburgh: translation from a rodent model through validation in a large mammal and then into clinical practice. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2019) 98:545–9. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13560

40. Houts PS, Bachrach R, Witmer JT, Tringali CA, Bucher JA, Localio RA. Using pictographs to enhance recall of spoken medical instructions. Patient Educ Couns. (1998) 35:83–8. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00065-2

Keywords: childhood cancer, fertility counseling, late effects, questionnaire, twinning

Citation: Stukaite-Ruibiene E, van der Perk MEM, Vaitkeviciene GE, Bos AME, Bumbuliene Z, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM and Rascon J (2023) Evaluation of oncofertility care in childhood cancer patients: the EU-Horizon 2020 twinning project TREL initiative. Front. Pediatr. 11:1212711. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1212711

Received: 26 April 2023; Accepted: 14 July 2023;

Published: 26 July 2023.

Edited by:

Tamara Diesch-Furlanetto, University Children's Hospital Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Valentina Magnani, University of Bologna, Italy© 2023 Stukaite-Ruibiene, van der Perk, Vaitkeviciene, Bos, Bumbuliene, van den Heuvel-Eibrink and Rascon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Egle Stukaite-Ruibiene ZWdsZS5lZ2xhaXRlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Abbreviations ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CED, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; CCS, childhood cancer survivors; HGDR, high gonadal damage risk; IGHG, International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group; LGDR, low gonadal damage risk; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; RT, radiotherapy; TREL, Twinning in Research and Education to Improve Survival in Childhood Solid Tumors in Lithuania; VULSK, Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.