- 1Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, St. Petersburg FL, United States

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore MD, United States

- 3Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 4Division of General Academic Pediatrics, Children's Mercy Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States

- 5Department of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, MO, United States

Introduction: Recent calls to action have urged graduate medical education leaders to develop health equity-focused curricula (HEFC) to redouble efforts to promote pediatric HE and address racism. Despite this call, examples of HEFC for pediatric residents are lacking. Such curricula could catalyze educational innovations to address training gaps.

Objective: To describe the design, content, and delivery of “Leaders in Health Equity (LHE),” an innovative HEFC delivered to categorical pediatric residents using multi-modal, service-free retreats.

Methods: This single institution, longitudinal curriculum study occurred between 2014 and 2020 and reports multi-level outcomes including: (1) impact on trainee's health equity related knowledge, skills and satisfaction, (2) residency impact and (3) institutional impact. Educational approaches used related to design, content and delivery are summarized and detailed.

Results: Trainees (n = 72) demonstrated significant improvements in pre-post knowledge and skills related to HE content. Residents also reported increased desire for advanced HE content over the course of the 6-year study period. Residency impact on operations and resources were sustainable with the opportunity for integration of LHE content in other curricular and training areas noted. Institutional impact included catalyzing organizational HE initiatives and observing an increase in resident-led quality improvement (QI) projects focused on LHE content.

Conclusions: On-going adaptation and growth of LHE content to educate increasingly prepared pediatric trainees is a critical next step and a best practice for educators in this evolving field. Developing HEFC within pediatric training programs using a longitudinal, leadership-centered approach may be an effective educational strategy in addressing pediatric health disparities.

Introduction

Training future generations of pediatricians to deliver culturally appropriate care and promote health equity is a graduate medical education (GME) priority redoubled in the context of COVID-19-related racial/ethnic disparities and the increased recognition of racism as a public health crisis (1). Recently, funding agencies including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have focused on defining key terms by which to catalyze more efforts addressing health disparities, introducing a definition by which we can specify that pediatric health equity reflects a collective goal that “every child has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible…that requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care” (2). In a novel call to action, Siegel et al. urged GME educators “to develop curricula that are accountable to community needs and that more comprehensively address health inequities” (3). This training expectation is further highlighted by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's (ACGME) Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, which assesses trainee connectivity to their institution's health equity efforts. Moreover, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) has similarly emboldened all pediatricians to engage in health equity efforts by launching new entrustable professional activities (EPAs) focused on creating competency among pediatricians towards addressing racism, discrimination, and other contributors to inequities (4). These newly launched training and certification standards highlight the timely need for health equity-focused curricula (HEFC) as a strategy to promote pediatric health equity. Beyond meeting accreditation and curricular requirements, however, integrating HEFC into pediatric graduate medical education broadens pediatric trainees' ability to recognize and address the social determinants of health and promotes a cultural shift to make health equity efforts the responsibility of all pediatricians.

Health equity-focused curricula can be broadly defined as training experiences including courses, rotations and other education providing trainees with the knowledge and skills to identify and ameliorate health disparities in their own patient populations and in the systems in which they work. Early efforts related to HEFC in medical education have demonstrated the value of using retreat-based approaches for engaging emergency medicine trainees in health-equity discussions (5) where residents described being more meaningfully engaged in HE discussions by being briefly relieved of service duties as part of the curriculum design. There is also early evidence of the impact of HEFC on medical student confidence levels and knowledge in working with underserved populations (6). To our knowledge, no prior HEFC have focused on multi-level outcomes among pediatric residents. Innovations related to health equity integration within pediatric GME programs are thus urgently needed to address heightened training expectations and promote systemic health equity strategies to address pediatric racial and ethnic disparities.

Six years ago, we identified a rare opportunity to design and deliver a health equity-focused curriculum while developing a new ACGME-accredited pediatric residency program (Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital). A central component of the pediatric residency program design was a longitudinal leadership-focused curriculum [Leadership Executive Academic Development (LEAD), described elsewhere] (7) embedded into annual 1–2-week service-free retreats. Viewing this training model as an ideal forum to offer health equity-focused training to residents, we nested a novel curriculum titled “Leaders in Health Equity” (LHE) within the LEAD framework.

We reflect here on our experience in creating and delivering LHE and describe early results related to trainees, the residency program, and institutional impact.

Methods

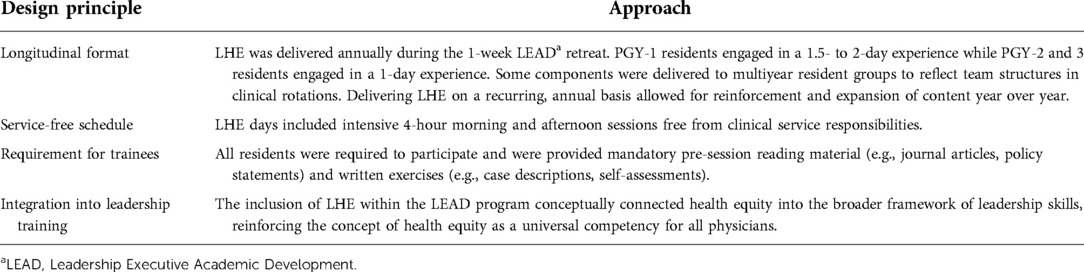

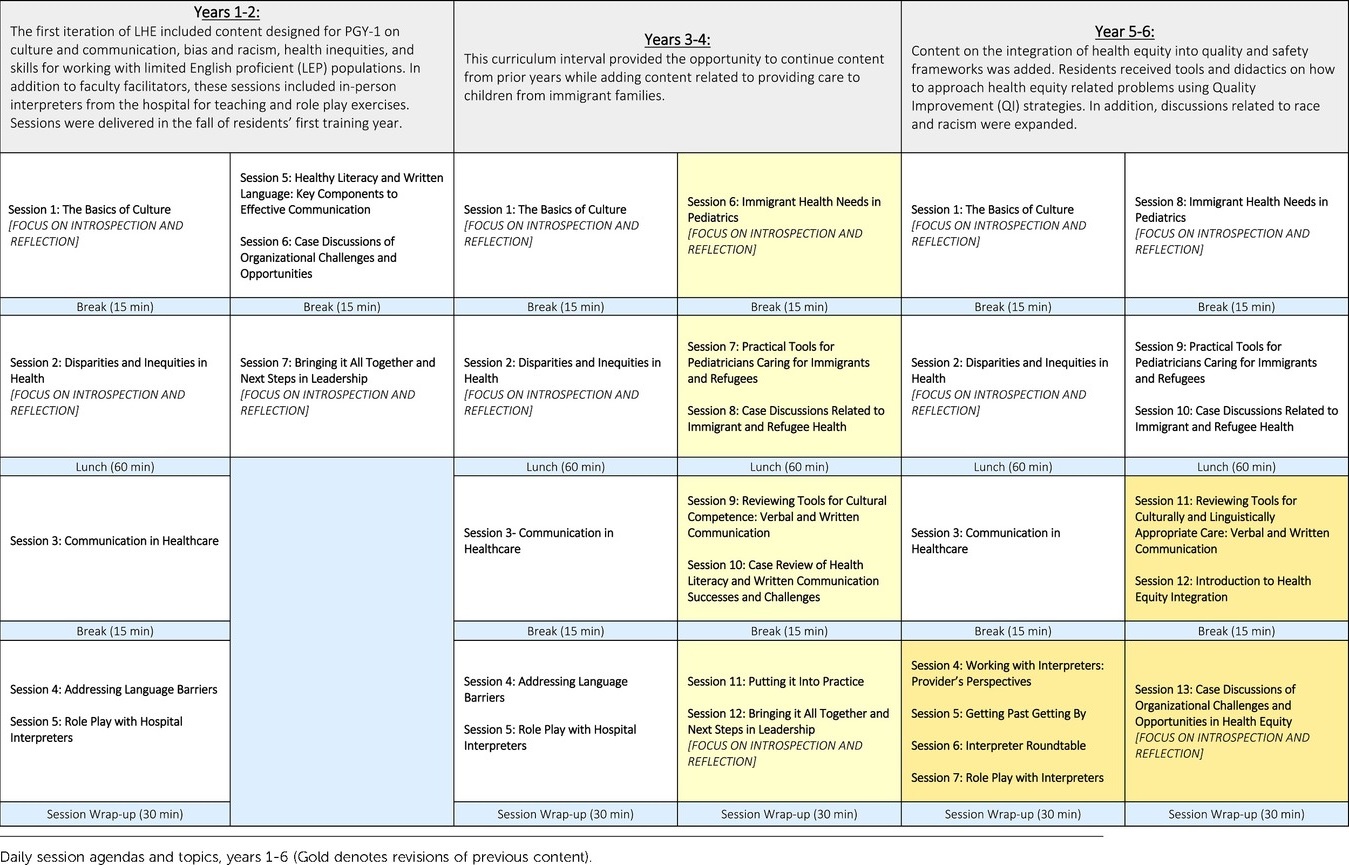

The primary goal of LHE was to provide immersive, longitudinal training that allowed pediatric residents to meaningfully engage in health equity-focused content during service-free retreats. LHE was delivered annually where PGY-1 residents engaged in a 1.5- to 2-day sessions. Key LHE principles and approaches related to curriculum design, content, and delivery included the following (Tables 1A–C):

Design: (1) longitudinal format, (2) service-free schedule, (3) requirement for all residents, and (4) integration into leadership (Table 1A).

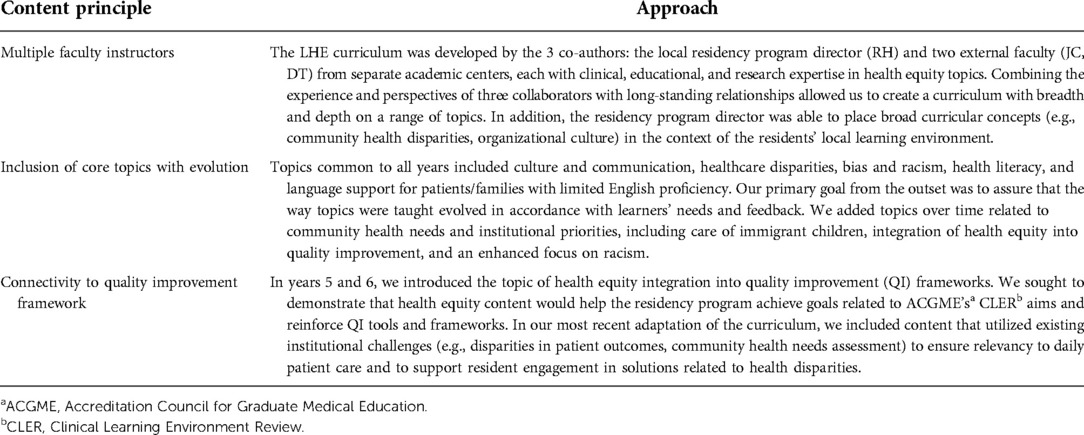

Content: (1) multiple faculty instructors with subject matter expertise, (2) identification of core topics with commitment to evolving content over time, and (3) connectivity of content to quality improvement (QI) frameworks (Table 1B).

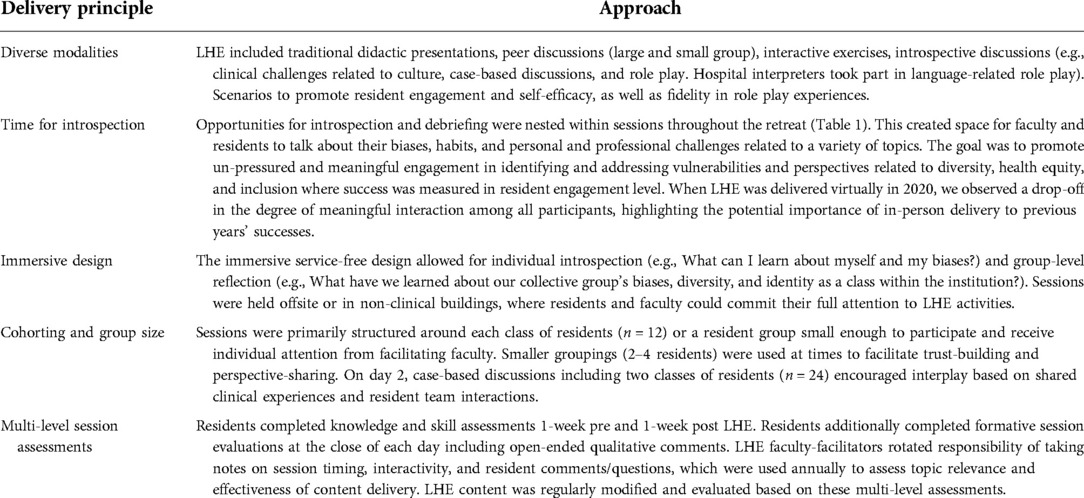

Delivery: (1) use of diverse modalities, (2) time for introspection, (3) immersive design, (4) use of cohorting and small group structure, and (5) multi-level assessments (Table 1C).

Although broad curricular goals remained the same over 6 years, we adapted content and delivery annually (Table 2). Learning objectives for LHE were initially focused around understanding the clinical needs of limited English proficient populations, the role of stereotypes and unconscious bias in clinical care, as well as the role of language in clinical care (Table 3). These learning objectives evolved over the 6-year study period, with new concepts (e.g., the role of system-based biases, use of quality improvement to address disparities, integration of health equity within day-to-day efforts) added over time. Data on trainee knowledge/skills and session feedback were collected and analyzed annually. This study was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analyses

Pre/post scores for survey items were summarized with medians and ranges. Data were first evaluated by year and subsequently pooled across years. Given the non-normal distribution of scores, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test was used to evaluate differences. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE Version 17.1 and accompanying graphs were created using GraphPad Prism Version 8.0.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

1. Trainee Impact

• Over 6 years, 120 pediatric residents participated (increasing from 12 residents/year in years 1 and 2 to 36/year after the program had grown to 3 classes). We report data on PGY-1 residents completing LHE training (n = 72).

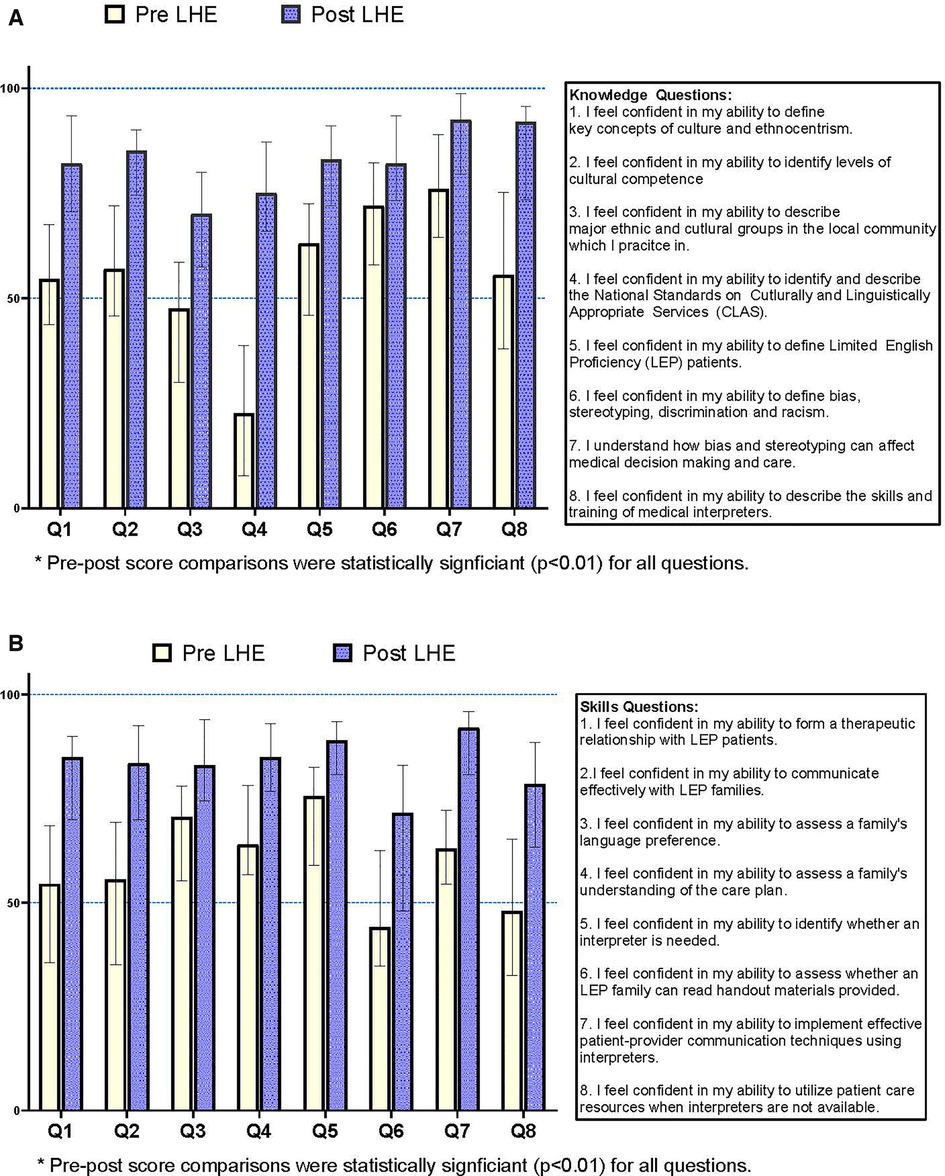

• Knowledge and Skills: We surveyed residents using an electronically based 16-question survey (2014–2017, pre-n = 44 [57% response rate], post n = 28 [39% response rate]). Residents were asked to rate their confidence and knowledge related to key questions using a visual ruler scale (scale: 0%-100%). We analyzed pre-post median responses for a series of 8 health equity-focused questions on knowledge and skills respectively (Figures 1A,B). Statistically significant changes were noted across all knowledge and skills questions with the greatest reported change in confidence noted regarding understanding the skills and training of medical interpreters (knowledge) and being able to identify whether an LEP family can understand written handout materials (skills). A new pre-post question format was introduced in 2018, limiting direct comparisons to prior quantitative data.

• Session feedback: Residents completed free-text survey questions following LHE sessions describing overall satisfaction and areas of potential improvement. In all years, residents gave high ratings to LHE sessions including peer-peer discussions, interactivity and role-play, and a focus on introspection and self-awareness. We noted an evolution in resident preparedness related to health equity, with those in more recent years requesting more advanced content, commenting that multiple health equity topics had been introduced in medical school.

2. Residency Impact

• Operations and resource impact: As a categorical program of 12 residents per class, we were able to deliver this service-free, annual, 1.5- to 2-day retreat using volunteer faculty to cover inpatient units. Costs for LHE curricula included (1) annual honoraria and travel costs for two external faculty, (2) fees for 3–4 interpreters to join session(s) ranging from $50–60/hour/interpreter, (3) catering (breakfast and lunch for 12 residents; $1000/day), and (4) non-clinical spaces (two local hotel conference rooms [$200/day]; on-campus educational space [no cost] in LHE years (5–6).

• Curricular impact: As a result of annual LHE workshops, content on disparities, health equity, and culturally/linguistically appropriate care has been integrated into multiple areas of the residency curriculum allowing residents to repeatedly revisit key concepts throughout training. Experiences include annual standardized patient scenarios focused on social determinants of health, research-based health equity sessions, and completion of a community rotation focused on underserved populations. Additionally, residents revisit LHE topics during quarterly conference sessions where residents lead small groups in reviewing health equity-related cases.

3. Institutional Impact

• Early on, residents outlined concerns regarding their learning environment including inadequate on-site interpreter access, biases observed within patient care, and personal experiences with bias and prejudice. In response, residents and program leadership collectively initiated an institutional effort to submit safety reports related to insufficient in person language support. This reporting prompted a broader language support services assessment (2017–2020) that led to improved in-person language services in the hospital. In addition, the number of resident-led quality improvement projects per year focusing on questions of health equity has grown annually, from 10% to 30% of projects. Finally, 4 trainees achieved language proficiency certification in languages other than English, a resource introduced and promoted through LHE workshops and subsequently offered by the institution to bilingual physicians.

Discussion

Our innovative longitudinal LHE curriculum, demonstrating multi-level impacts, provides an example of how to meet recent calls to action from GME leaders (3) to develop health equity-focused curricula. As GME programs look to increase and improve training in health equity and related concepts, new models are needed that move beyond didactic lectures, single workshops, and other short-term approaches and pediatric trainee programs may be best primed to lead these educational charges for change. Longitudinal integration of health equity content into existing competency goals (such as leadership development and quality improvement) is needed to avoid such content being perceived as “extra work” or “separate” from fundamental professional development. Leadership tenets offered in the LEAD framework such as self-reflection, creating change, and improving the quality of patient care (8), are principles that naturally extend to health equity calls to action. As Wright et al. proposed in their health leadership competency framework, a physician should “become[e] a change agent that models and facilitates the integration of cultural humility and cultural competency… [into daily practice]”(6).

Figure 1. (A) Resident self-reported median confidence score (Interquartile Range): LHE knowledge*. (B) Resident self-reported median confidence score (Interquartile Range): LHE skills*.

A key strength to our curricular approach is integrating health equity content with a leadership training framework and quality improvement approaches. These frameworks inherently promote a focus on trainee self-introspection, life-long learning, problem-solving, and commitment to promoting equity that are necessary components to initiating a health equity mindset that may persist beyond completion of the training experience and be sustained throughout training. In our experience, educational efforts addressing cultural competency, disparities, and health equity often are one-off lectures focused on knowledge and attitudes, lacking the practical skill-building over time that is necessary to advance health equity. Other strengths to our approach include (1) a consistent retreat-based framework housing flexible content that can be adapted year-to-year in response to rapidly changing trainee readiness, (2) multiple instructors offering current examples and experience in practical health equity work (rather than only theoretical concepts), and (3) sustained multi-level impacts from a modest investment of resources.

While the application of our model in a single pediatric residency limits the generalizability of our findings, the key elements to our approach, the combination of topics in our curriculum, and the lessons learned from our integrative model could be instructive for others aiming to make health equity a fundamental part of GME, rather than an add-on or bonus topic. Additionally, core learning objectives reflected the application of essential health equity topics to local circumstances, a tactic central to our integrative approach. The resulting curriculum is unique, making it less applicable in another context without modification, but making it specifically relevant to our learners in a way that “off-the-shelf” curricula are not. We believe that educators in each learning context should consider a similar process, where the essential topics listed in our curriculum might be applied to their own specific circumstances and modified year-over-year to reflect rapid changes in trainees and health equity practice. Our quantitative trainee data is limited by sample size and variable response rates, common challenges in residency training evaluation. However, we could identify trends in learner responses that guided the evolution of our model over 6 years. Finally, knowledge and skills were assessed using an unvalidated program-specific survey. Because the primary intent of the surveys was to provide grounding in trainees’ health equity gaps, they have served their purpose to date. The opportunity to enhance the rigor and validity of LHE outcomes is a focus of our team's next steps.

Based on our experiences with LHE, we offer the following recommendations that reflect our own next steps and provide strategies that may be helpful to others embarking on health equity curriculum development:

1. Routinely engage pediatric trainees in ongoing modification of health equity content development, implementation, and delivery. The effectiveness of LHE programming has relied on our ability to incorporate resident feedback, new developments (e.g. current racial justice movements), and lessons learned from previous years (e.g. organizational health equity efforts). We meet periodically throughout the year to modify and add to the curriculum for the upcoming fall. Early in the COVID pandemic, we discussed improvements to our virtual learning approach and the incorporation of COVID disparities, anti-racism movements, and rapidly-evolving US immigration policies that impact child health. Input from residents has been critical and has reflected progressively increasing interest, comfort, and preparation in areas related to health equity.

2. Seek practical tools and deliberate approaches to move diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts from the abstract to the clinically applicable including quality improvement. The inherent connectivity of health equity and QI was recently highlighted by Ayosla et al., who described how QI aims focused on addressing disparities pose a “win-win” for patients and educators (9). One of the two external LHE faculty (JC) first introduced a checklist-oriented framework for integrating diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) perspectives into QI into the 2018 program. This framework was well received and will be further implemented in future sessions to promote the universal inclusion of DEI in resident QI efforts.

3. Adapt or create methods for directly observing skills taught in health equity curricula. Recognizing that gains in trainee knowledge are not equivalent to behavior change that impacts patient care, we plan to use new evaluation methods (incorporating competency-based assessments) to understand how trainee perceptions, biases, understanding of health disparities, and clinical skills may shift as a consequence of this training. Promising progress has been made in the field using DEI-related simulations and behavior-based evaluation such as objective structured clinical encounters (OSCE's) involving culturally or linguistically challenging scenarios (10). Collaborating with residency program leaders may allow us to use the program's existing competency-based evaluation system to better measure health equity-related behaviors.

Conclusion

Although LHE is custom-designed for our local context, curricular features may be useful for others in the fields of medical education, health disparities, and leadership development. In particular, we propose several tactics that may further drive health equity educational efforts in the GME setting including integration of health equity content into leadership training, creation of structured opportunities for trainee introspection (3), and engaging pediatric trainees in content development. We are hopeful that this description of our approach and its early outcomes might provide insight to others heeding the call to action for enhanced health equity education in GME.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to this original manuscript. RGH was responsible for curriculum development and implementation of the proposed curriculum. She additionally developed the manuscript content, analytic approach and developed the figures and tables. JDC and DAT were responsible for curriculum development and implementation of the proposed curriculum. They additionally contributed to the manuscript content and edited content and data within the submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Paul DW, Knight KR, Campbell A, Aronson L. Beyond a moment - reckoning with our history and embracing antiracism in medicine. New Engl J Med. (2020) 383(15):1404–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021812

2. Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57(4):254–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254

3. Siegel J, Coleman DL, James T. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. (2018) 93(2):159–62. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002054

4. Entrustable Professional Activities American Board of Pediatrics Accessed 8/11/2022, 2022. https://www.abp.org/sites/public/files/pdf/gen_peds_epa_14.pdf

5. Chary A, Molina M, Dadabhoy F, Manchanda E. Addressing racism in medicine through a resident-led health equity retreat. Western J Emerg Med. (2021) 22(1):41–4. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.10.48697

6. Denizard-Thompson N, Palakshappa D, Vallevand A, et al. Association of a health equity curriculum with medical students’ knowledge of social determinants of health and confidence in working with underserved populations. JAMA Network Open. (2021) 4(3):e210297. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0297

7. Hernandez RG, Hopkins A, Dudas RA. The evolution of graduate medical education over the past decade: building a new pediatric residency program in an era of innovation. Med Teach. (2018) 40(6):615–21. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1455969

8. Sadowski B, Cantrell S, Barelski A, O'Malley PG, Hartzell JD. Leadership training in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. (2018) 10(2):134–48. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00194.1

9. Aysola J, Myers JS. Integrating training in quality improvement and health equity in graduate medical education: two curricula for the price of one. Acad Med. (2018) 93(1):31–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002021

Keywords: health equity, health disparities, graduate medical education, curriculum, leadership, quality improvement

Citation: Hernandez RG, Thompson DA and Cowden JD (2022) Responding to a call to action for health equity curriculum development in pediatric graduate medical education: Design, implementation and early results of Leaders in Health Equity (LHE). Front. Pediatr. 10:951353. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.951353

Received: 23 May 2022; Accepted: 20 September 2022;

Published: 25 October 2022.

Edited by:

Anika Hines, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rachel Thornton, Nemours Children's Health, United StatesFrancesca Felicia Operto, University of Salerno, Italy

© 2022 Hernandez, Thompson and Cowden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raquel G. Hernandez UmFxdWVsLmhlcm5hbmRlekBqaG1pLmVkdQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Children and Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

Raquel G. Hernandez

Raquel G. Hernandez Darcy A. Thompson3

Darcy A. Thompson3