94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Pediatr. , 26 April 2022

Sec. General Pediatrics and Pediatric Emergency Care

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.897803

Ruud G. Nijman1,2,3*†

Ruud G. Nijman1,2,3*† Silvia Bressan4†

Silvia Bressan4† Julia Brandenberger5,6,7†

Julia Brandenberger5,6,7† Davi Kaur8

Davi Kaur8 Kristina Keitel7,9†

Kristina Keitel7,9† Ian K. Maconochie1,3†

Ian K. Maconochie1,3† Rianne Oostenbrink10†

Rianne Oostenbrink10† Niccolo Parri11†

Niccolo Parri11† Itai Shavit12†

Itai Shavit12† Ozlem Teksam13†

Ozlem Teksam13† Roberto Velasco14†

Roberto Velasco14† Patrick van de Voorde15†

Patrick van de Voorde15† Liviana Da Dalt4†

Liviana Da Dalt4† Ann De Guchtenaere16†

Ann De Guchtenaere16† Adamos A. Hadjipanayis17†

Adamos A. Hadjipanayis17† Robert Ross Russell18†

Robert Ross Russell18† Stefano del Torso19†

Stefano del Torso19† Zsolt Bognar20†

Zsolt Bognar20† Luigi Titomanlio21,22*†

Luigi Titomanlio21,22*†This joint statement by the European Society for Emergency Paediatrics and European Academy of Paediatrics aims to highlight recommendations for dealing with refugee children and young people fleeing the Ukrainian war when presenting to emergency departments (EDs) across Europe. Children and young people might present, sometimes unaccompanied, with either ongoing complex health needs or illnesses, mental health issues, and injuries related to the war itself and the flight from it. Obstacles to providing urgent and emergency care include lack of clinical guidelines, language barriers, and lack of insight in previous medical history. Children with complex health needs are at high risk for complications and their continued access to specialist healthcare should be prioritized in resettlements programs. Ukraine has one of the lowest vaccination coverages in the Europe, and outbreaks of cholera, measles, diphtheria, poliomyelitis, and COVID-19 should be anticipated. In Ukraine, rates of multidrug resistant tuberculosis are high, making screening for this important. Urgent and emergency care facilities should also prepare for dealing with children with war-related injuries and mental health issues. Ukrainian refugee children and young people should be included in local educational systems and social activities at the earliest opportunity.

The tragic events in Ukraine require an immediate and meaningful response from European societies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to safeguard children and guarantee their health care needs are met.

On the one hand this means pathways need to be established to continue essential medical treatment of children with known underlying disease. Examples of this include ongoing treatment for oncological conditions, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, and cystic fibrosis. Difficulties include differences in treatment regimens and care standards, lack of medical documents, and language barriers. From frontline physicians, this will require a coordinating and facilitating role. On the other, we will also need to anticipate children presenting with illnesses, mental health issues, and injuries related to the war itself and the flight from it. There will be a non-negligible public health risk for spread of communicable diseases, such as COVID-19 and multidrug resistant TB. In time, focus and demands of health care provision will shift as the conflict goes on.

From a European perspective, the war in Ukraine and the stream of refugees resulting from this will be markedly different from other recent global conflicts. Importantly, the proximity of Ukraine on the European continent will lead to an immediate influx of refugees, compared with a delayed influx, often after stays in refugee camps and hazardous journeys, observed with conflicts occurring outside the continent.

It is to be expected that emergency departments (EDs) will function as a first point of access for health systems in many countries, and pediatric emergency clinicians, and other health care professionals looking after acutely unwell children, will need to understand their roles and responsibilities when faced with refugee children and young people from Ukraine. An existing European Academy of Pediatrics (EAP) statement provides extensive and evidence based recommendations for first and follow-up appointments for asymptomatic migrants, including refugee children and young people in Europe (1). In addition, a previous European Society of Emergency Pediatricians (EUSEP) survey explored obstacles and needs for providing emergency care to this vulnerable population (2). This statement builds on this previous work and was written by members of the executive committees and experts of the EUSEP and EAP. The statement highlights recommendations on providing urgent and emergency care to refugee children and young people and inform on ongoing efforts to coordinate and support child health care in response to the Ukrainian war.

Firstly, guidance should be issued at a national level on the financial renumeration when providing healthcare to this group of patients. National pediatric and emergency medicine societies should advocate for an open, and fee free, access to urgent and emergency care services; individual clinicians can contact their representing organizations and stress the importance of this. The EAP will act as the strategic political voice for families and pediatricians within the European Union to convey the advocacy message coming from the national organizations. As pediatric health care professionals we should be able to provide urgent and emergency care to children without financial reservations or constraints. We feel strongly that this should allow for prescription of first line maintenance drugs of existing medical conditions, such as asthma, epilepsy, and diabetes. Similarly, caregivers might use emergency services if they run out of medical devices, such as feeding tubes, and arrangements should be in place to provide supplies. All this should be offered with careful consideration of privacy and General Data Protection Regulation compliant documentation of person identifiable data.

Working together with NGOs and pediatric societies, we have constructed an open access repository for sharing of resources. This includes a channel on the European Society for Emergency Medicine (EUSEM) Academy platform with educational and teaching videos, as well as guidelines and care toolkits in a variety of languages (Table 1). An example template in English/Ukrainian/Russian for registering details of a refugee child or young person presenting at the ED is available in Appendix 1.

EUSEM is also working together with NGOs and national societies in an effort to provide teaching and educational resources to people working in conflict areas in Ukraine and neighboring countries.

Previous survey work found that, traditionally, most refugee children and young people attending EDs had similar medical needs to the local population. Most of these required standard urgent and emergency medicine skills; patients with rare infectious diseases or complex mental health issues represented only a minority of the problems faced (2–5). A recently published review gives a patient-centered summary of key challenges in health care delivery for refugees and migrants, which might aid in preparing local healthcare services (3). Obstacles to providing urgent and emergency care were mostly a lack of clinical guidelines, language barriers, and lack of insight in previous medical history. The latter poses a significant risk for children with complex health needs dependent on continued specialist healthcare and the prescribing of regular medications. Efforts should focus on a coordinated resettlement process for children with acute tertiary healthcare needs, for example by means of expanding the existing United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) resettlement program. The European Children's Hospitals Organisation (ECHO) and European governments are identifying hospitals across Europe that can provide (inpatient) care to pediatric patients with complex medical conditions. During the relocation process refugee children and young people with complex health needs are at high risk of acute complications of their underlying medical disease, likely to result in presentations to EDs. Inherent issues related to displacement, such as traveling, incomplete family structures, stays in refugee camps or other temporary accommodation, malnourishment, and exposure to communicable diseases, will further complicate the health situation of children with complex health needs.

Language barriers and cultural differences have been identified as important barriers to providing urgent and emergency care in EDs (2). This is particularly relevant for consenting and assenting procedures for medical assessments, prescribing of medications or urgent surgical procedures. There will likely be high demand on translation services in the near future, and it might not always be possible to connect to translation services when consulting patients in the ED. Arranging access to certified clinical translators is an important early step for each clinical area providing urgent and emergency care. Information leaflets in Cyrillic are available online (6).

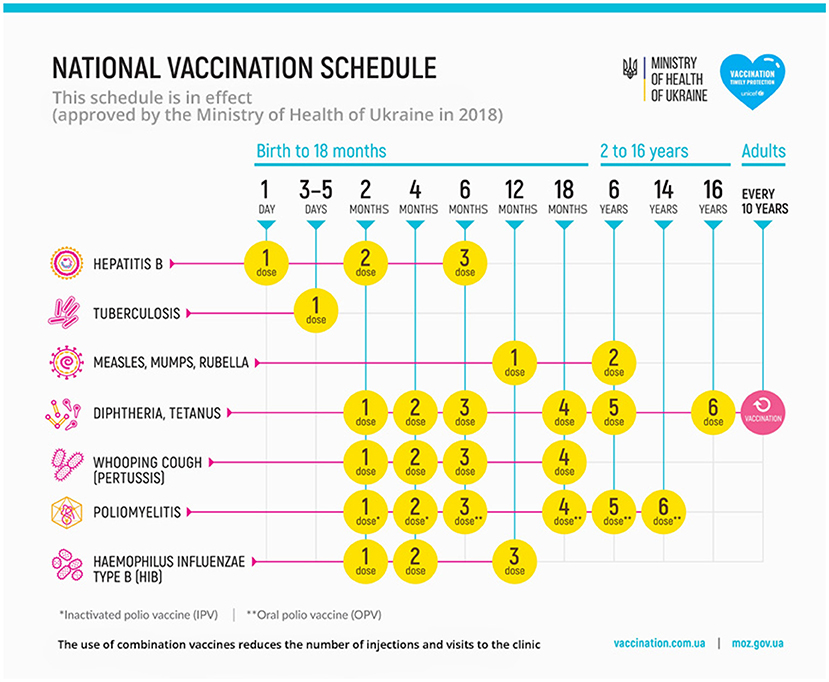

The international community should invest in securing that children receive their routine childhood immunizations in time. The Ukrainian immunization schedule is similar to those used in many other European countries (Figure 1). Notable omissions from the routine schedule include vaccinations for pneumococcus, meningococcus, rotavirus, varicella zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Although immunizations should preferably be offered by public health and primary care organizations, this might not always be possible. When a child presents to the ED, this could be used as an opportunity to offer any catch-up immunizations or signpost to the relevant health organizations. Immunizations should be given according to the schedule of the non-resident country where the child presents, and preferably follow local guidelines. When offering immunizations in the ED, make sure this is accurately documented to prevent duplication or missed vaccinations, and this should be in line with regulations of privacy and data protection. EDs should provide children without an original immunization passport with a replacement immunization record (7). Administered vaccination names might be unfamiliar; translations of common infections in Eastern European languages are available (8).

Figure 1. Immunization schedule of Ukraine. source: https://en.moz.gov.ua/vaccinations (accessed 11-03-2022).

There is a considerable risk for an increase in COVID-19 infections amongst the people fleeing Ukraine. Appropriate personal protection equipment mitigating this risk should be worn by health care providers. Overall, an estimated 34% of the Ukrainian population were fully vaccinated against COVID-19 as per February 20th 2022 (9). Vaccinations were recommended for children aged 12 and over in October 2021 (10). Booster vaccines were recommended for anyone aged 18+ in early January 2022, with, as per February 20th 2022, only 2% of the population having received this. Approved vaccines in Ukraine include Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Janssen, Oxford/AstraZeneca, Covishield, Sinovac (11). Refugees and migrants should be included in any regional or national responses to COVID-19, including access to health information diagnostic testing, and medical care (12). Information on COVID-19 testing services, personal protection equipment, quarantine for close contacts and isolation for positive cases (where in force) should be distributed in Cyrillic at EDs and other healthcare facilities in order to contain infection spread.

Refugee populations are at higher risk for communicable diseases. Often, these are directly related to exposure during their flight, poor sanitation, and crowded temporary accommodations. In addition, Ukraine has one of the lowest vaccination coverage in the WHO European Region and is below target levels for Diphteria—Tetanus—Pertussis [3rd dose], Polio [3rd dose], measles, and Hepatitis B [3rd dose] (9). Measles immunization levels are the lowest in Europe (13). Outbreaks of cholera, measles, diphtheria, and poliomyelitis are anticipated. The incidence of tuberculosis (TB) is higher in Ukraine than in most other European countries with a significant burden of multidrug resistant TB (27% of new TB cases), and children and young people should actively be screened for TB; similarly, HIV remains a public health issue and a priority communicable disease in Ukraine, and this should be screened for with a low threshold (14). Also, blood borne viruses, such as Hepatitis B and C are seen more frequently in refugee populations (15, 16). In the absence of clinical signs and symptoms that would classify them as infectious according to existing local or public health guidelines, these refugee patients do not need isolation upon arrival in the emergency department. However, it might not be needed to screen for helminths and malaria routinely in this population, unless known high risk. In sexually active or abused young people, consider screening for syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections or referring them to appropriate sexual health services. Consider empiric treatment for intestinal parasites with albendazole in children >2 years and >10 kg. Similarly, check for signs of scabies, headlice, and other soft tissue infections and have a low threshold for treating this. In line with international recommendations, we propose the following infectious diseases screening at first opportunity:

- Perform a tuberculosis screening for latent infection (tuberculin skin test/ interferon-gamma release assays) followed by chest x-ray if either test is positive

- HBV-antibodies (Hbs-Ag, anti-Hbs and anti-HBc) and HCV antibodies

- If immune suppressed: Strongyloides serology

- Low threshold for investigating HIV status

Typically, dehydration and malnutrition are frequently encountered medical problems in refugee populations. As the war continues these might become more relevant for children and young people from Ukraine when they visit urgent and emergency care facilities. Consideration should be given to testing for (1) Hemoglobin level to check for anemia and treat iron deficiency; (2) Vitamin D level if at risk for malnutrition and rickets. Mothers with young infants will benefit from easy access to (breast) feeding support teams. All children and young people, and in particular those with dental issues, should be seen by a dentist following their arrival in another European country. Similarly, vision and hearing should be tested in all refugee children and young people, as impairments can heavily impact on quality of life and social and educational integration.

Although European EDs might have some experience in mass casualties following isolated major incidents (17), few, if any, will be familiar with looking after an ongoing stream of acute or delayed presentations of children with war-related injuries. Some of these children will have received rudimentary initial medical or surgical management. It is important to take note of any prior blood transfusions, tetanus vaccination status, and any antibiotics prophylaxis given. Useful resources covering both mass casualty management in the pre-hospital and hospital setting are available via the WHO Academy (18). This also includes information on management of chemical, biological, and nuclear agents. Recent experiences from Israel looking after children with war-related injuries from Syria have shown us that injuries are often complex, needing collaboration of multiple hospital departments. One study described that injury mechanism were most often penetrating injuries, followed by blunt trauma and blast injuries, caused by fragments, blasts, and gunshot wounds. Most common injuries were head trauma and lower extremities injuries (19). Setting up coordinated military-civilian retrieval of severe pediatric warzone trauma in the neighboring countries might improve outcomes (20).

The war and the resulting displacement and separation from friends and family will lead to a surge of mental health issues in young people who fled from Ukraine. Some of these young people will present to EDs with acute mental health issues, such as intoxications, intentional ingestions, self-harm, suicidal ideation, anxiety, sleeping disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For those who pose an acute risk to themselves or to others, usual pathways for mental health conditions should be followed. However, active screening for broader mental health issues will be important, for example by using the internationally recognized HEADSSS (Home, Education/Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sex and relationship, Self harm and depression, Safety and abuse) tool for the assessment of adolescent patients (21) and screening for symptoms of PTSD (Appendix 2). Identifying a local pathway for providing formal mental health assessments away from the ED, and signposting available community services to families are important preparatory steps, recognizing that language barriers will be a major challenge. Of note, screening for symptoms of PTSD in this vulnerable and at risk population is important to decide on the choice of sedative agents when performing procedural sedation in the ED (e.g., avoid ketamine as single sedative agent, and consider additional use of midazolam).

We stress the importance of integrating displaced families in local communities urgently, minimizing time away from education, peer support, and social activities. Clinicians working with children and young people in urgent and emergency care will need to be prepared to liaise with primary care and community pediatricians to arrange ongoing care for displaced families. All these children and young people should undergo appropriate and expedited health checks, and appropriate resources need to be allocated for this. Strategies for continuing care after ED visit, and for performing investigations, such as infection screening, and reporting results back to the family and public health organizations should be tailored to regional health systems. Similarly, clear lines of communication with social services will need to be in place, and caregivers should be given information about the role of social services at a national and regional level and about available support in the local community. We foresee that considerable numbers of young people seeking our help will be unaccompanied. When children and young people are accompanied by adults, efforts should be made to establish if these are the legal guardians of the child or young person. Details of the original family composition and current caregivers should be shared with social services. Accompanying adults should be signposted to appropriate health care facilities for their medical problems or routine health checks. There is clear guidance on appropriateness of diagnostic tests for young people with disputed age and the role of pediatricians for age assessments, and there is no role for bone radiographs or dental X rays for age determination in EDs (22).

Finally, we acknowledge the extremely difficult times our colleague pediatricians from Ukraine are experiencing, whether they are still working in their home country, or have made the difficult decision to leave Ukraine. As international societies, we will need to think about pathways for and empower our Ukrainian colleagues who wish to continue their profession outside their home country.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

All authors are members of the executive committees of the European Society of Emergency Pediatricians and European Academy of Pediatrics, and the statement was written as part of a coordinated response by both international societies. All authors had original input into writing the manuscript and reviewed and approved of the final version as submitted.

RN was funded by NIHR ACL award (2018-021-007).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This article was submitted to General Pediatrics and Pediatric Emergency Care, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics.

The European Society for Emergency Pediatrics is a formal branch society of the European Society for Emergency Medicine.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.897803/full#supplementary-material

1. Schrier L, Wyder C, Del Torso S, Stiris T, von Both U, Brandenberger J, et al. Medical care for migrant children in Europe: a practical recommendation for first and follow-up appointments. Eur J Pediatr. (2019) 178:1449–67. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03405-9

2. Nijman RG, Krone J, Mintegi S, Bidlingmaier C, MacOnochie IK, Lyttle MD, et al. Emergency care provided to refugee children in Europe: RefuNET: a cross-sectional survey study. Emerg Med J. (2021) 38:5–13. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2019-208699

3. Brandenberger J, Tylleskär T, Sontag K, Peterhans B, Ritz N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries - the 3C model. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:755. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x

4. Brandenberger J, Pohl C, Vogt F, Tylleskär T, Ritz N. Health care provided to recent asylum-seeking and non-asylum-seeking pediatric patients in 2016 and 2017 at a Swiss tertiary hospital - a retrospective study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:81. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10082-z

5. Gmünder M, Brandenberger J, Buser S, Pohl C, Ritz N. Reasons for admission in asylum-seeking and non-asylum-seeking patients in a paediatric tertiary care centre. Swiss Med Wkly. (2020) 150:w20252. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20252

6. Ukraine Academy of Paediatric Specialties. Of Course About Children - Website for Parents From the Ukrainian Academy of Pediatric Specialties. Available online at: https://zrozumilo.org (accessed March 11, 2022).

7. World Health Organisation - regional office for Europe. Delivery of Immunization Services for Refugees and Migrants - Technical Guidance. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326924/9789289054270-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed March 11, 2022).

8. Immunization action coalition. Quick Chart of Vaccine-Preventable Disease Terms in Multiple Languages. Available online at: https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p5122.pdf (accessed March 11, 2022).

9. World Health Organisation. Public Health Situation Analyses (PHSA). Available online at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/ukraine-phsa-shortform-030322.pdf (accessed March 11, 2022).

10. Pravda, Ukrayinska,. Children Over 12 Years of Age Can Be Vaccinated Against Covid With All Vaccinations - the Ministry of Health. Available online at: https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2021/10/27/7311841/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

11. VIPER Group COVID19 Vaccine Tracker Team. COVID19 Vaccine Tracker - Ukraine. Available online at: https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/country/ukraine/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

12. Brandenberger J, Baauw A, Kruse A, Ritz N. The global COVID-19 response must include refugees and migrants. Swiss Med Wkly. (2020) 150:w20263. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20263

13. Lancet T. Measles, war, and health-care reforms in Ukraine. Lancet. (2018) 392:711. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31984-6

14. European Centre for Disease Prevention Control. Operational Public Health Considerations for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in the Context of Russia's Aggression Towards Ukraine. Available online at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/prevention-control-infectious-diseases–Russia-aggression.pdf (accessed March 11, 2022).

15. Coppola N, Alessio L, Gualdieri L, Pisaturo M, Sagnelli C, Caprio N, et al. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus infection in undocumented migrants and refugees in southern Italy, january 2012 to june 2013. Eurosurveillance. (2015) 20:30009. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.35.30009

16. Yun K, Matheson J, Payton C, Scott KC, Stone BL, Song L, et al. Health profiles of newly arrived refugee children in the United States, 2006-2012. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:128–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302873

17. Juncken K, Heller AR, Cwojdzinski D, Disch AC, Kleber C. [Distribution of triage categories in terrorist attacks with mass casualties : analysis and evaluation of European results from 1985 to 2017]. Unfallchirurg. (2019) 122:299–−308. doi: 10.1007/s00113-018-0543-2

18. World Health Organisation Academy. Emergency Response Learning & Resource Center. Available online at: https://express.adobe.com/page/XCHiPbrUNNNFC/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

19. Naaman O, Yulevich A, Sweed Y. Syria civil war pediatric casualties treated at a single medical center. J Pediatr Surg. (2020) 55:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.02.022

20. Samuel N, Epstein D, Oren A, Shapira S, Hoffmann Y, Friedman N, et al. Severe pediatric war trauma: a military-civilian collaboration from retrieval to repatriation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2021) 90:e1–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002974

21. Tagg, A,. Mental Health Screening. Available online at: https://dontforgetthebubbles.com/mental-health-screening/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

22. Royal College of Paediatrics Child Health. Refugee and Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children and Young People - Guidance for Paediatricians. Available online at: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/refugee-unaccompanied-asylum-seeking-children-young-people-guidance-paediatricians#age-assessment (accessed March 11, 2022).

Keywords: emergency medicine, pediatrics, refugee, infectious diseases, mental health, social medicine, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder

Citation: Nijman RG, Bressan S, Brandenberger J, Kaur D, Keitel K, Maconochie IK, Oostenbrink R, Parri N, Shavit I, Teksam O, Velasco R, van de Voorde P, Da Dalt L, Guchtenaere AD, Hadjipanayis AA, Ross Russell R, del Torso S, Bognar Z and Titomanlio L (2022) Update on the Coordinated Efforts of Looking After the Health Care Needs of Children and Young People Fleeing the Conflict Zone of Ukraine Presenting to European Emergency Departments—A Joint Statement of the European Society for Emergency Paediatrics and the European Academy of Paediatrics. Front. Pediatr. 10:897803. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.897803

Received: 16 March 2022; Accepted: 31 March 2022;

Published: 26 April 2022.

Edited by:

Jérémie F. Cohen, Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, FranceReviewed by:

Adriana Yock-Corrales, Dr. Carlos Sáenz Herrera National Children's Hospital, Costa RicaCopyright © 2022 Nijman, Bressan, Brandenberger, Kaur, Keitel, Maconochie, Oostenbrink, Parri, Shavit, Teksam, Velasco, van de Voorde, Da Dalt, Guchtenaere, Hadjipanayis, Ross Russell, del Torso, Bognar and Titomanlio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruud G. Nijman, ci5uaWptYW5AaW1wZXJpYWwuYWMudWs=; Luigi Titomanlio, bHVpZ2kudGl0b21hbmxpb0BhcGhwLmZy

†ORCID: Ruud G. Nijman orcid.org/0000-0001-9671-8161

Silvia Bressan orcid.org/0000-0002-6736-5392

Julia Brandenberger orcid.org/0000-0001-7169-8184

Kristina Keitel orcid.org/0000-0002-9663-3843

Ian K. Maconochie orcid.org/0000-0001-6319-8550

Rianne Oostenbrink orcid.org/0000-0001-7919-8934

Niccolo Parri orcid.org/0000-0002-8098-2504

Itai Shavit orcid.org/0000-0003-4493-473X

Ozlem Teksam orcid.org/0000-0003-1856-0500

Roberto Velasco orcid.org/0000-0003-0073-2650

Patrick van de Voorde orcid.org/0000-0001-9053-0475

Liviana Da Dalt orcid.org/0000-0003-2977-3907

Ann De Guchtenaere orcid.org/0000-0002-2723-1437

Adamos A. Hadjipanayis orcid.org/0000-0003-4337-3176

Robert Ross Russell orcid.org/0000-0002-6551-2344

Stefano del Torso orcid.org/0000-0002-1903-7458

Zsolt Bognar orcid.org/0000-0002-2328-3512

Luigi Titomanlio orcid.org/0000-0003-4909-803X

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.