- 1Department of Neonatology, Hunan Children's Hospital, Changsha, China

- 2Department of Nursing, Hunan Children's Hospital, Changsha, China

- 3Department of Nursing, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, China

- 4Department of Clinical Research Center, Hunan Children's Hospital, Changsha, China

- 5Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, United Kingdom

Background: Neonatal death often occurs in tertiary Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs). In China, end-of-life-care (EOLC) does not always involve parents.

Aim: The aim of this study is to evaluate a parent support intervention to integrate parents at the end of life of their infant in the NICU.

Methods: A quasi-experimental study using a non-randomized clinical trial design was conducted between May 2020 and September 2021. Participants were infants in an EOLC pathway in the NICU and their parents. Parents were allocated into a family supportive EOLC intervention group or a standard EOLC group based on their wishes. The primary outcomes depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for mothers; Hamilton Depression rating scale for fathers) and Satisfaction with Care were measured 1 week after infants' death. Student t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test categorical variables were used in the statistical analysis.

Results: In the study period, 62 infants died and 45 infants and 90 parents were enrolled; intervention group 20 infants, standard EOLC group 25 infants. The most common causes of death in both groups were congenital abnormalities (n = 20, 44%). Mean gestational age of infants between the family supportive EOLC group and standard EOLC group was 31.45 vs. 33.8 weeks (p = 0.234). Parents between both groups did not differ in terms of age, delivery of infant, and economic status. In the family support group, higher education levels were observed among mother (p = 0.026) and fathers (p = 0.020). Both mothers and fathers in the family supportive EOLC group had less depression compared to the standard EOLC groups; mothers (mean 6.90 vs. 7.56; p = 0.017) and fathers (mean 20.7 vs. 23.1; p < 0.001). Parents reported higher satisfaction in the family supportive EOLC group (mean 88.9 vs. 86.6; p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Supporting parents in EOLC in Chinese NICUs might decreased their depression and increase satisfaction after the death of their infant. Future research needs to focus on long-term effects and expand on larger populations with different cultural backgrounds.

Clinical Trial Registration: www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT05270915.

Introduction

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that neonatal death within the first 28 days of life reached 17 per 1,000 live births, estimating around 2.4 million neonates (1). In China, neonatal death was 3.5 per 1,000 live births in 2019, which was around 57,000 deaths (2). End-of-life care (EOLC) has been emphasized by the WHO Global Action Plan 2013–2020 (3, 4). The mandate by the WHO highlights the need for improvement in infant's EOLC and the support of parents and family in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

From a historical perspective, the care around death of neonates was first addressed in the United States in the 1980's. In 1982, Silverman described that EOLC has been successfully implemented in hospice settings for newborns (5). Over the years, EOLC has been further progressed in European countries and Northern America leading to a number of national guidelines and clinical practice recommendations (6–8). And recently, palliative care has become a new service in many healthcare settings and EOLC can play an important part in palliative care.

Recent studies have focused on EOLC decisions (9), pain and comfort management (10) and implementation of the palliative care sub-specialty within Neonatology (11). Unfortunately, EOLC received less attention in Asia, specifically in mainland China (12). A literature review investigating the EOLC practices in Asian countries identified only 11 empirical studies from Hong Kong, India, Israel, Japan, Mongolia, Taiwan, and Turkey (13). Studies around EOLC from Taiwan explored the attitudes of NICU staff and identified a number of barriers in delivering high quality of EOLC (14, 15). The most common barriers were insufficient training in communication with parents, staffing shortages and lack of unit policies in supporting palliative care. Compared to European countries and Unite States, less evidence is available from Asian countries in how parents are involved in the care of their infant and specifically how family-centered care (FCC) is included in EOLC.

Since 2010, FCC has gained more attention in China and has been gradually implemented in Chinese NICUs. An FCC program was implemented in our NICU department at Hunan Children's Hospital in Changsha China, and contributed to a wider implementation across Chinese NICUs (16–19). Three trials were conducted to test FCC interventions related to parental empowerment (training of parents and participation of parents in the care of their infant) demonstrating significant improvements in breastfeeding and quality of life. The studies also documented a decrease in parental anxiety and depression as well as an improvement in parent satisfaction (16–18). Despite different beliefs, cultures, attitudes and policy, the EOLC remains unexplored in China without rigorous evidence of supporting parents in end-of-life decisions and care. As parental support is an important component of FCC, the support of parents during EOLC has different perspectives and needs different approaches. However, one cannot deliver poor EOLC while providing excellent FCC. Both practices are interlinked. Therefore, our NICU is translating and implementing FCC into EOLC practices.

In mainland China, parents are mostly the main decision-makers in withdrawing life-sustaining treatments in infants and neonatologists often follow the wishes of the parents. However, there is limited experience in supporting parents after the decision is made to withdraw treatment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a family supportive EOLC intervention and to evaluate parent reported outcome measures related to depression and satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study adopted a non-randomized controlled trial (non-RCT) design because blinding was not possibly due to the nature and delivery of the intervention. The study was registered in clinicalTrials.gov (approval number NCT05270915). The study was conducted between 6th of May 2020 and 20th of September 2021. The guideline ‘Evaluating complex interventions in end of life care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews' was used to report this study (20).

Setting

The study setting was the tertiary NICU at the stand-alone Hunan Children's Hospital in Changsha, China. The 180-bed NICU department serves as a regional tertiary center for all infants above 24 weeks gestational age requiring intensive care treatment. Main causes of mortality in our NICU are congenital malformation, preterm birth and septic shock. In 2020 and 2021, the annual NICU admission rate was around 4,000 infants. The annual mortality rate of the NICU in the past 5 years was between 3 and 5%. Since the introduction of FCC in our NICU, parents are allowed to visit the NICU in daytime (8.00–17.30 h) and participate in basic care of their infant and are supported by medical and nursing staff (17, 20).

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement

Before the study protocol was finalized, we organized a patient and public involvement and engagement meeting with 15 parent couples with previous experience in neonatology. The individual conversations with both mothers and fathers of 15 infants were focused on the proposed study methods, intervention, and outcome measures. Overall, most parents thought that their involvement in EOLC was important to reduce depression during and after the death of their infant. Parents indicated that they would value the support of NICU staff and would welcome a separate room to stay with their baby in the final days of life. Most parents also suggested having a psychologist in the NICU team and having their support at the EOLC. In terms of follow-up, most parents indicated that they did not want a long-term follow-up meeting or complete surveys 1 month after NICU discharge. The suggestions of the parents were amended in the final study protocol.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Inclusion criteria were infants whose treatment was withdrawn at Corrected Gestational Age (CGA) <28 days and their parents. The exclusion criteria were infants with an expected time of death <3 h after NICU admission. Parents were excluded if they had mental illness or language issues that might limit their integration and communication with the healthcare team.

After an end-of-life decision was made, a research nurse informed the parents about the study. Participation was based on the parents' decision and after written consent. The allocation of the infant and parents to the intervention or control group was case-controlled based on the wishes of the parents. If parents wanted to stay in the NICU with their infant during the EOLC pathway, parents were allocated to the intervention group. If parents did not want to stay in the NICU during the EOLC pathway, their infant would stay in our NICU and receive standard EOLC care.

Standard Care and Intervention

The standard EOLC included the international guidance of palliative care and EOLC in neonatology (21–23). In China, parents are often the decision-makers of their infant's treatment and the NICU clinicians usually respect the parent's decision (24). After parents have decided to withdraw treatment, standard EOLC is initiated and includes monitoring of vital signs and withholding or withdrawing rescue procedures such as intubation and intravenous infusion. Unnecessary lines are removed and pain management is provided by analgesia. Comfort care is provided by nurses including basic care such as skin care and oral care. After the infant died, the NICU physician informs the parents by phone.

The intervention “family supportive EOLC” was developed based on the international guidelines of family-centered care (25) with additional aspects of care and support. We designed a separated single-bedded EOLC room for the infant and parents. Other family members, such as grandparents or siblings, were allowed to visit the infant and parents. The design of the room included the option for parents to stay comfortably on a sofa to relax and to play soothing music. Parents were encouraged to stay as long as they want and participate in basic care including physical contact with their infant. The nurses supported the parents in creating commemorative items such as a “Yuan man” box with photos, baby handprint cards, footprint cards, a lock of hair and other precious memory items. A psychologist, in collaboration with our NICU, and a neonatologist supported the parents by individual interviews on a daily basis to listen to the concerns of parents and to provide emotional support. To ensure consistency in delivering the intervention, the medical staff and psychologist were trained in delivering the interviews and EOLC practices.

Outcomes Measures and Data Collection

The primary outcomes were depression and satisfaction as reported by parents at one week after infant's death. Because the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) has not been validated among fathers, we decided to use the Chinese version of the Hamilton Depression rating scale (HAMD) to evaluate depression among fathers. The Chinese version of the EPDS was used to assess depression among mothers (26, 27). The HAMD includes 17 items with a 3 or 5-point Likert answer option scale with a total score of 78 (28). The HAMD has been translated and validated in Chinese. The internal consistency of the Chinese version demonstrated a Cronbach's alpha of 0.646 (29). The EPDS is developed to measure the depression of mothers after NICU (30). The scale includes 10 items with a 4-point Likert answer option scale with a total score of 30. The EPDS has been translated and validated in Chinese among mothers. The internal consistency of the Chinese version has been adequate with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.76 (31).

Parent satisfaction was measured by the hospital standard parent satisfaction survey completed by both parents.The parent satisfaction with care instrument was our hospital standardized parents satisfaction with care questionnaire including 20 items using a 5-point Likert answer option scale with a total score of 100. It included 4 parts of medical treatment, medical staff's negotiation attitude, hospital settings and social service. This scale is used among all parents in our hospital on a weekly basis by an external company.

Basic parent and infant characteristics were collected from the medical charts. Infants' characteristics included prenatal history, diagnoses, on-going therapy at time of withdrawal of treatment. The parental characteristics included age, mode of delivery, education and family income. The parental outcome measures, depression and satisfaction, were collected 1 week after the death of the infants during a face-to-face follow-up meeting in the hospital with the psychologist.

Data Analysis

The statistical software package “IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp” was used for the analysis. The distribution of baseline characteristics for two groups are summarized using descriptive statistical methods. Student t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables were used to analyze the outcomes.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Children's Hospital (HCHLL-2020-23). The study procedures adhered to the International Council for Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice guidance (32) and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (33). Parents were informed about the study objectives, written informed consent was obtained, and parents were able to withdraw from participation at any time.

Result

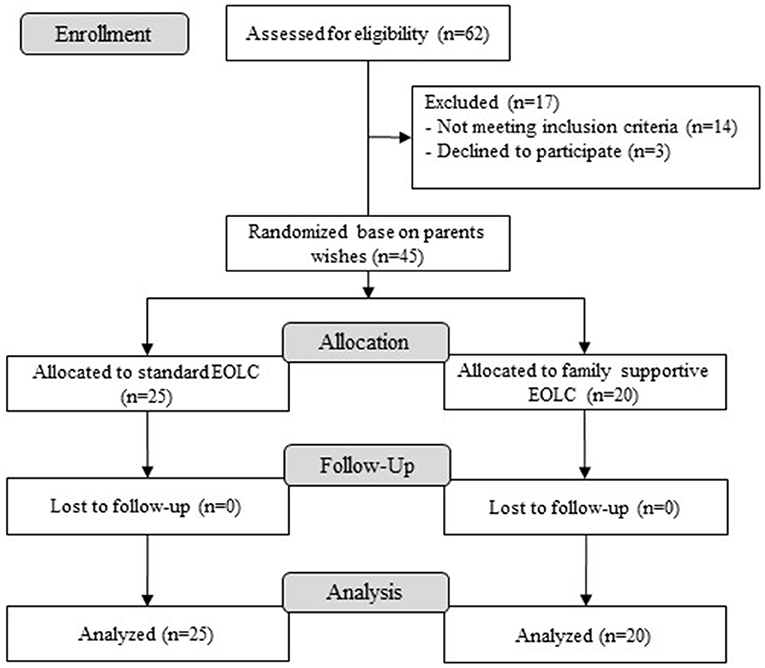

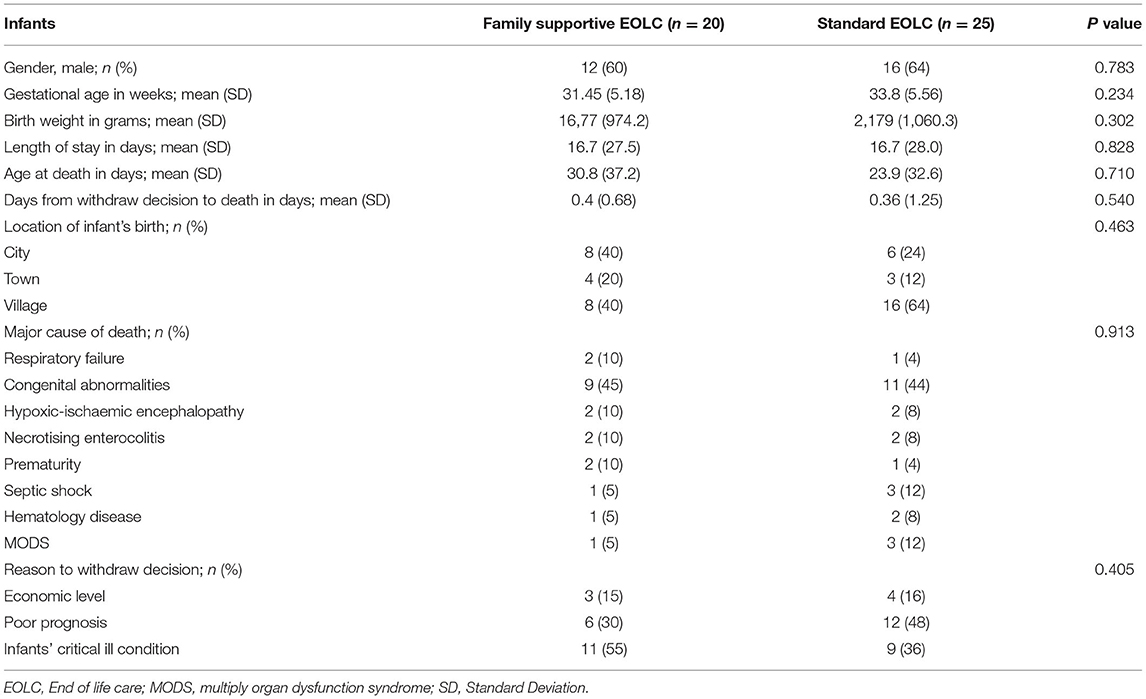

In total, 62 infants died in the NICU during the study period. Of these, 45 infants and 90 parents were screened and enrolled in the study (Figure 1). The infants' average gestational ages were smaller and birth weights were lower in the family supportive EOLC group compared with the standard care group, but no significant differences were observed (Table 1). The infants' gender did not significantly differ between both groups (male: 12 vs 16, p = 0.783). The most common causes of death were congenital abnormalities in both group. The median age of death in the standard care group was lower than in the family supportive EOLC group (Table 1). The main reasons of treatment withdrawal were deficiency in family financial support (not able to pay the additional hospital expenses), poor neurological prognosis and serious condition (Table 1).

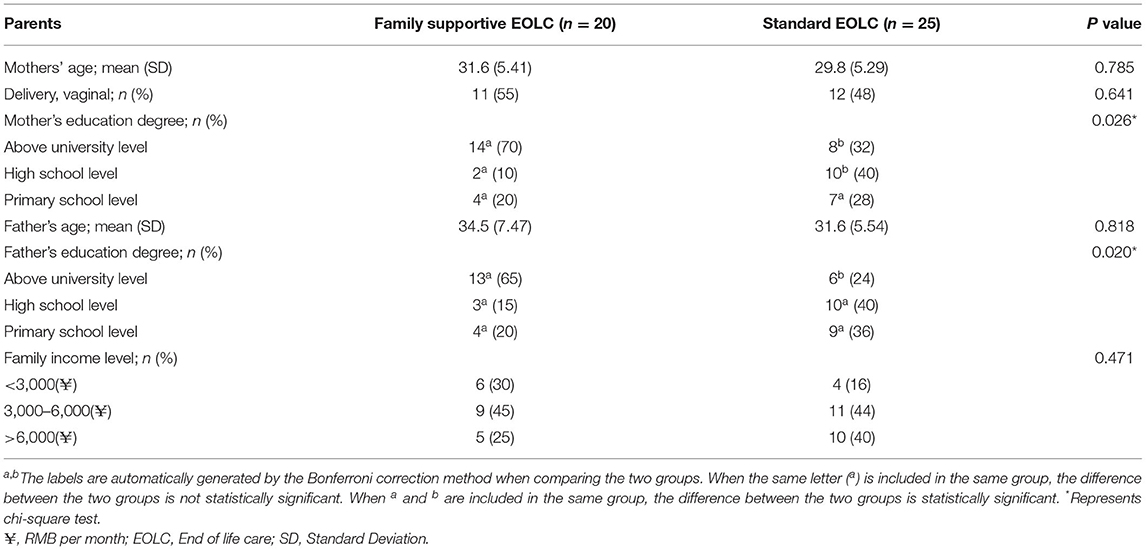

The characteristics of the 90 parents (45 mothers and 45 fathers) are presented in Table 2. There were no differences in parent's age, way of delivery, and economic status. Both the mothers and fathers in the family supportive EOLC groups had significantly higher educational background compared to the parents in the standard EOLC group (Table 2).

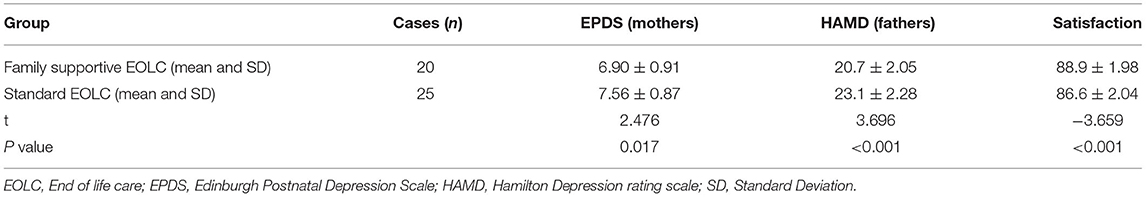

The outcomes of parental depression revealed differences in both mothers and fathers between both groups (Table 3). The post-natal depression in mothers was significant lower in the family supportive EOLC group compared to mothers in the standard EOLC group (mean 6.90 vs. 7.56; p = 0.017). The depression among fathers in the family supportive EOLC group were significantly lower compared to fathers in the standard EOLC group (mean 20.7 vs. 23.1; p = 0.001). The outcomes of parent satisfaction revealed differences in that parents in the family supportive EOLC group showed higher satisfaction rates compare to the standard EOLC group (mean 88.9 vs. 86.6; p = 0.001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to support parents during EOLC in mainland China. The aim of our study was to test a family supportive EOLC intervention to decrease depression among parents and increase parent satisfaction around the death of their infant. The outcome of parent satisfaction with care can be considered an important result. Although no standardized instruments are available to measure satisfaction of EOLC, our hospital questionnaire was sensitive enough to demonstrate differences of overall satisfaction scores between both groups of parents. Further research is needed to develop robust instruments to measure the outcomes of EOLC such as parent satisfaction.

The main cause of death among our included infants was congenital malformations, which is consistent with other studies in China (34, 35). This is in contrast with international studies reporting the main cause of death in neonatology is related to premature birth and infection (36, 37). This difference might be due to the location of our NICU situated in a stand-alone children's hospital. Infants born very premature in other regions of our Hunan province might not have been transferred to our center.

Parental presence during EOLC has been addressed as an important part in neonatal care. The role of the NICU staff in EOLC is to support parents in their mental health and wellbeing as well as empowering parents to take part in the care of their infant during the last days of life (38). The international guideline of FCC in neonatal, pediatric and adult intensive care suggests implementing strategies to improve parental confidence and mental health during and after the NICU (39). In China, the initial steps in implementing FCC in neonatology only started a few years ago (16–18). However, there is limited evidence in FCC practices across the regions in China (40, 41). Our study might contribute to identifying interventions that are feasible and effective in Chinese NICUs who have started recently with FCC practices.

Our study evaluate the family supportive EOLC intervention related to parent depression. In our previous FCC intervention studies we were able to demonstrated improvements in parental depression and anxiety (42, 43). Parents face psychological distress in perinatal and neonatal death with an increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Reports have identified the relationship between perinatal death and the devastating impact on parents, including stress and mental health issues lasting for at least 6 months after the death of their infant (44, 45). During our parent consultation round to discuss our study protocol, parents indicated that they did not want a 6 months follow-up survey. Therefore, we have no follow-up data to inform any long-term support to parents in our community.

In our study, more parents opted for the standard EOLC. Perhaps this can be described to a cultural issue that parents find it difficult in facing the end of life of their infant. A review of Chinese hospice care identified that parents are afraid of staying with their child and experienced more anxiety (46). The perspectives of parents of EOLC in neonatology was explored in a qualitative study among 10 parents (47). These parents indicated that it was extremely important to be able to stay in the NICU regardless the diagnosis on their infant. This “zero separation” has also be addressed as an important issue during the recent two COVID-19 pandemic years (48, 49).

Limitations

A number of limitations of our study needs to be addressed. First, we used a non-RCT design to provide parents the option to participate in the study. We provided parents the option to choose in what study arm they wanted to participate based on the advice of the parent consultation round before the start of the study. Secondly, the study intervention was not blinded which can potentially influence the outcome measures. The third limitation is that the study was performed at a single center with a small sample size limiting the generalizability of the results for clinical practice. Forth, the different instruments to measure depression among fathers and mothers limited the comparison between the parent couples. Finally, our follow-up was 1 week after the infants' death. Further research is needed to explore long-term impact on parents.

Conclusion

Neonatal death is still one of the major problems threatening the global health. Our study indicated that providing a comfortable environment and supportive care to parents during the final days of life of an infant decrease their depression and increases parent satisfaction. The NICUs in mainland China and beyond might consider to involve parents in EOLC by providing a single room, have a dedicated psychologist available and provide supportive commemoration materials for parents such as a “yuan man” box.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Hunan Children's Hospital (HCHLL-2020-23). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

L-hZ, RZ, X-mP, Y-eX, and JML: concept and design. M-hC, NZ, QT, K-lC, and RZ: data collection. QT, NZ, and RZ: statistical analysis. RZ and JML: drafting of the manuscript. L-hZ, X-mP, Y-eX, NZ, and QT: providing revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Chinese Nursing Association (number 202028) and the Hunan Children's Hospital Research Foundation (number 202114) financially supported this work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We express our deep gratitude to the parents for their willingness and cooperation in the study.

References

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2021. Monitoring Health for the SDGs. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf (accessed January 2, 2022).

2. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. China Health Statistics Yearbook 2020. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press. (2021). p. 215–8.

3. World Health Organization. Palliative Care. Key Facts (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed January 2, 2022).

4. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance World Health Organization. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. Connor SR, Bermedo MCS, editors. London, UK. (2014). Available online at: https://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf (accessed January 2, 2022).

5. Silverman WAA. hospice setting for humane neonatal death. Pediatrics. (1982) 69:239. doi: 10.1542/peds.69.2.239

6. Haug S, Dye A, Durrani S. End-of-life care for neonates: assessing and addressing pain and distressing symptoms. Front Pediatr. (2020) 24:574180. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.574180

7. Mcdermott CL, Engelberg RA, Woo C. Novel data linkages to characterize palliative and end-of-life care: challenges and considerations. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2019) 58:851–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.017

8. National Institute for Health Care Excellent (NICE). End of Life Care for Infants, Children and Young People With Life-Limiting Conditions: Planning and Management. NICE guideline. 25 July 2019. Available online at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61 (accessed January 2, 2022).

9. Dombrecht L, Beernaert K, Chambaere K, Cools F, Goossens L, Naulaers G, et al. End-of-life decisions in neonates and infants : a population-level mortality follow-back study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2021). 2022:340–1. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-322108

10. Veldhuijzen ZS, Ferretti E, MacLean G, Daboval T, Lauzon L, Reuvers E. et al. Medications to manage infant pain, distress and end-of-life symptoms in the immediate postpartum period. Expert Opin Pharmacother. (2022) 23:43–8. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2021.1965574

11. Allen JD, Shukla R, Baker R, Slaven JE, Moody K. Improving neonatal intensive care unit providers' perceptions of palliative care through a weekly case-based discussion. Palliat Med Rep. (2021) 2:93–100. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0121

12. Chen X, Li H, Song J, Sun P, Lin B, Zhao J, et al. The resuscitation of apparently stillborn neonates: a peek into the practice in China. Front Pediatr. (2020) 2:231. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00231

13. Kim S, Savage TA, Hershberger PE, Kavanaugh K. End-of-life care in neonatal intensive care units from an Asian perspective: an integrative review of the research literature. J Palliat Med. (2019) 22:848–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0304

14. Chen CH, Huang LC, Liu HL, Lee HY, Wu SY, Chang YC, et al. To explore the neonatal nurses' beliefs and attitudes towards caring for dying neonates in Taiwan. Matern Child Health J. (2013) 17:1793–801. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1199-0

15. Huang LC, Chen CH, Liu HL, Lee HY, Peng NH, Wang TM et al. The attitudes of neonatal professionals towards end-of-life decision-making for dying infants in Taiwan. J Med Ethics. (2013) 39:382–6. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100428

16. Zhang R, Huang RW, Gao XR, Peng XM, Zhu LH, et al. Involvement of Parents in the Care of Preterm Infants: A Pilot Study Evaluating a Family-Centered Care Intervention in a Chinese Neonatal ICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2018) 19:741–7. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001586

17. Lv B, Gao XR, Sun J, Li TT, Liu ZY, Zhu LH, et al. Family-centered care improves clinical outcomes of very-low-birth-weight infants: a quasi-experimental study. Front Pediatr. (2019) 12:138. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00138

18. He SW, Xiong YE, Zhu LH, Lv B, Gao XR, Latour JM. Impact of family integrated care on infants' clinical outcomes in two children's hospitals in China: a pre-post intervention study. Ital J Pediatr. (2018) 44:65. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0506-9

19. Ding X, Zhu L, Zhang R, Wang L, Wang TT, Latour JM. Effects of family-centred care interventions on preterm infants and parents in neonatal intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Aust Crit Care. (2019) 32:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.10.007

20. Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande G, Preston N, Morgan M. MORECare. Evaluating complex interventions in end of life care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med. (2013) 24:111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-111

21. Mancini, A, Uthaya, S, Beardsley, C, Wood, D, Modi, N,. Practical Guidance for the Management of Palliative Care on Neonatal Units. 1st edn. London: Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, 2014. Available online at: https://www.chelwest.nhs.uk/services/childrens-services/neonatal-services/links/Practical-guidance-for-the-management-of-palliative-care-on-neonatal-units-Feb-2014.pdf (accessed January 2, 2022).

22. Cole A, Craig, F, Daly, C, English, S, George, S, Gill, B, . Palliative Care (Supportive End of Life Care): A Framework for Clinical Practice in Perinatal Medicine. London: British Association of Perinatal Medicine. (2010). Available online at: https://hubble-live-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/bapm/file_asset/file/72/Palliative_care_final_version__Aug10.pdf (accessed January 26, 2022).

23. Palliative Care Australia,. Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care for All Australians. Deakin West: Palliative Care Australia. (2005). Available online at: https://palliativecare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Standards-for-providing-quality-palliative-care-for-all-Australians.pdf (accessed January 26, 2022).

24. Li SP, Chen PY. The strategy of treatment abandonment in NICU. Medicine Philosophy. (2007) 6:66–7.

25. Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Kathleen AP, Erin KK. Joanna H, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. (2017) 45:103–28. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169

26. Maurer DM, Raymond TJ, Davis BN. Depression: screening and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. (2018) 98:508–15. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010558.pub2

27. Ijaz S, Davies P, Williams CJ, Kessler D, Lewis G, Wiles N. Psychological therapies for treatment-resistant depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 5:CD010558.

28. Nixon N, Guo B, Garland A, Kaylor-Hughes C, Nixon E, Morriss R. The bi-factor structure of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in persistent major depression; dimensional measurement of outcome. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0241370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241370

29. Li WB, Xu MZ, Gao YL. The validity and reliability of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Chin J Nerv Ment Dis. (2006) 2:118–20.

30. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. (1987) 150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

31. Guo XJ, Wang YQ, Chen J. Study on the efficacy of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in puerperas in Chengdu. Chin J Pract Nurs. (2009) 1:4–6.

32. Good, Clinical Practice Network,. ICH harmonised guideline integrated addendum to ICH E6(R1): Guideline for Good Clinical Practice ICH E6(R2) ICH Consensus Guideline. Available online at: https://ichgcp.net/ (accessed December 19, 2021).

33. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. (2018). Available online at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed December 19, 2021).

34. Dong HF, Li WL, Xu FL, Li DL, Li L, Wang XC, et al. Investigation of in-patient neonatal death at 18 hospitals in Henan Province. Chin J Perinat Med. (2019) 6:412–9.

35. Xu FD, Kong XY, Feng ZC. Mortality rate and cause of death in hospitalized neonates: an analysis of 480 cases. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. (2017) 2:152–8. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2017.02.005

36. Veloso FCS, Kassar LML, Oliveira MJC, Lima THB, Bueno NB, Gurgel RQ, et al. Analysis of neonatal mortality risk factors in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Pediatr (Rio J). (2019) 95:519–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2018.12.014

37. Lona Reyes JC, Pérez Ramírez RO, Llamas Ramos L, Gómez Ruiz LM, Benítez Vázquez EA, Rodríguez Patino V. Neonatal mortality and associated factors in newborn infants admitted to a Neonatal Care Unit. Arch Argent Pediatr. (2018) 116:42–8. doi: 10.5546/aap.2018.eng.42

38. Krishelle LA, Nancy KE. Primary palliative care in neonatal intensive care. Semin Perinatol. (2017) 41:133–9. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2016.11.005

39. McGrath JM, Wool C, Black BP, Leuthner SR, Jones EL, Muñoz-Blanco S, et al. Chapter 15. Attending to pain and suffering in palliative care. In: Limbo R, Wool C, Carter B, editors. Handbook of Perinatal and Neonatal Palliative Care, 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. (2020). p. 234–53.

40. Yi YZ, Su T, Jia YZ, Xue Y, Chen YZ, Zhang QS, et al. Family-centered care management strategies for term and near-term neonates with brief hospitalization in a level III NICU in Shenzhen, China during the time of COVID-19 pandemic. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2021) 22:1–4. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1902499

41. Li XY, Lee S, Yu HF, Ye XY, Warre R, Liu XH, et al. Breaking down barriers: enabling care-by-parent in neonatal intensive care units in China. World J Pediatr. (2017) 13:144–51. doi: 10.1007/s12519-016-0072-4

42. Baughcum AE, Fortney CA, Winning AM, Dunnells ZDO, Humphrey LM, Gerhardt CA. Healthcare satisfaction and unmet needs among bereaved parents in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. (2020) 20:118–26. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000677

43. Lacasse JR, Cacciatore J. Prescribing of psychiatric medication to bereaved parents following perinatal/neonatal death: an observational study. Death Stud. (2014) 38:589–96. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2013.820229

44. Youngblut JM, Brooten D. Comparison of mothers and grandmothers physical and mental health and functioning within 6 months after child NICU/PICU death. Ital J Pediatr. (2018) 44:89. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0531-8

45. Baransel ES, Uçar T. Posttraumatic stress and affecting factors in couples after perinatal loss: a Turkish sample. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2020) 56:112–20. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12390

46. Huang J, Song ZZ. The current situation and progress of hospice care in China. J Mod Med Health. (2020) 2:214–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5519.2020.02.016

47. Currie ER, Christian BJ, Hinds PS, Perna CSJ, Robinson Day S, et al. Parent perspectives of neonatal intensive care at the end-of-life. J Pediatr Nurs. (2016) 31:478–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.03.023

48. Ryan L, Plötz FB, van den Hoogen A, Latour JM, Degtyareva M, Keuning M, et al. Neonates and COVID-19: state of the art : neonatal sepsis series. Pediatr Res. (2022) 91:432–9. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01875-y

Keywords: neonatal death, end-of-life care, infants, parents, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, family-centered care

Citation: Zhang R, Tang Q, Zhu L-h, Peng X-m, Zhang N, Xiong Y-e, Chen M-h, Chen K-l, Luo D, Li X and Latour JM (2022) Testing a Family Supportive End of Life Care Intervention in a Chinese Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Quasi-experimental Study With a Non-randomized Controlled Trial Design. Front. Pediatr. 10:870382. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.870382

Received: 06 February 2022; Accepted: 07 June 2022;

Published: 22 July 2022.

Edited by:

Arjan Te Pas, Leiden University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Katie Gallagher, University College London, United KingdomPia Lundqvist, Lund University, Sweden

Copyright © 2022 Zhang, Tang, Zhu, Peng, Zhang, Xiong, Chen, Chen, Luo, Li and Latour. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li-hui Zhu, MjI4OTY1MTkzQHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Rong Zhang

Rong Zhang Qian Tang2,3†

Qian Tang2,3† Li-hui Zhu

Li-hui Zhu Jos M. Latour

Jos M. Latour