94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Pediatr. , 28 November 2022

Sec. Pediatric Cardiology

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.860394

Orival de Freitas Filho1*

Orival de Freitas Filho1* Evelyn Sue Nakahira1

Evelyn Sue Nakahira1 Aurelino Fernandes Schmidt Junior1

Aurelino Fernandes Schmidt Junior1 Estela Azeka2

Estela Azeka2 Marcelo Biscegli Jatene2

Marcelo Biscegli Jatene2 Paulo Manuel Pego-Fernardes1

Paulo Manuel Pego-Fernardes1

We will report a case of a desmoid tumour (DT), which developed at the surgical site of the pacemaker after a late childhood heart transplant. Patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy followed up in the paediatric cardiology service. It evolved with the dissociation of ventricular rhythm caused by severe heart failure, which led to the implantation of a cardiac resynchronization device prior to heart transplantation. The progression to end-stage heart disease culminated in a heart transplant at 12 years old. One year after the transplant, at the age of 13 years, he presented a progressively growing mass on the generator site of the resynchronization device. The initial decision was to remove the device. During the removal surgery, there was no haematoma or fluid collection. However, there was a progression of the lesion. The lesion was biopsied with the anatomopathological diagnosis of a DT. Resection surgery happened 4 months after the start of the mass growth. At that time, the tumour reached 20 cm in diameter. The lesion infiltrated the pectoralis major muscle and this muscle was resected partially en bloc with the lesion. The defect had primary closure. The patient evolved without postoperative complications and was discharged on the 14th postoperative day. The surgical specimen came with negative circumferential margins. However, the deep margin was microscopically positive. Due to deep involvement, the patient underwent adjuvant radiotherapy. Currently, the patient is under clinical follow-up and has no evidence of tumour recurrence. DT is a rare tumour, with unpredictable courses. Surgery can be considered in the progression of lesions. Treatment is justified by long survival after a heart transplant and in DT patients. DT is a differential diagnosis to be considered in progressive growth lesions.

Heart transplantation is the treatment of choice for children with refractory congenital heart disease and cardiomyopathies. The tumours are transplant-related complications with challenging management.

A desmoid tumour (DT) is a rare type of tumour. DT consists of clonal fibroblastic proliferation from deep fascia or soft tissues. The tumour has unpredictable behaviour: spontaneous regression, maintenance, and growth are possible. DT does not give metastasis. However, local recurrence is frequent (1).

In this paper, we report DT in a heart transplantation patient. To our knowledge, it is the first case of such association. This case had challenging management due to the development and growth phase of adolescence in addition to the post-heart transplant status with the oncologic disease.

A brown male had idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), which required a cardiac resynchronization device implant at 10-year-old due to severe heart failure with ventricular rhythm dissociation. He had no other past medical issues and also no familiar related disease. Due to the progression to end-stage heart disease, the patient had a heart transplant at 12 years old. The anatomopathological report of the explant confirmed idiopathic DCM. He used tacrolimus and mycophenolate for immunosuppression and without graft dysfunction. One year after the transplant, at the age of 13 years, he presented a progressively growing mass on the generator site of the resynchronization device. The initial decision was to remove the device. During the surgical procedure, there was no haematoma or fluid collection.

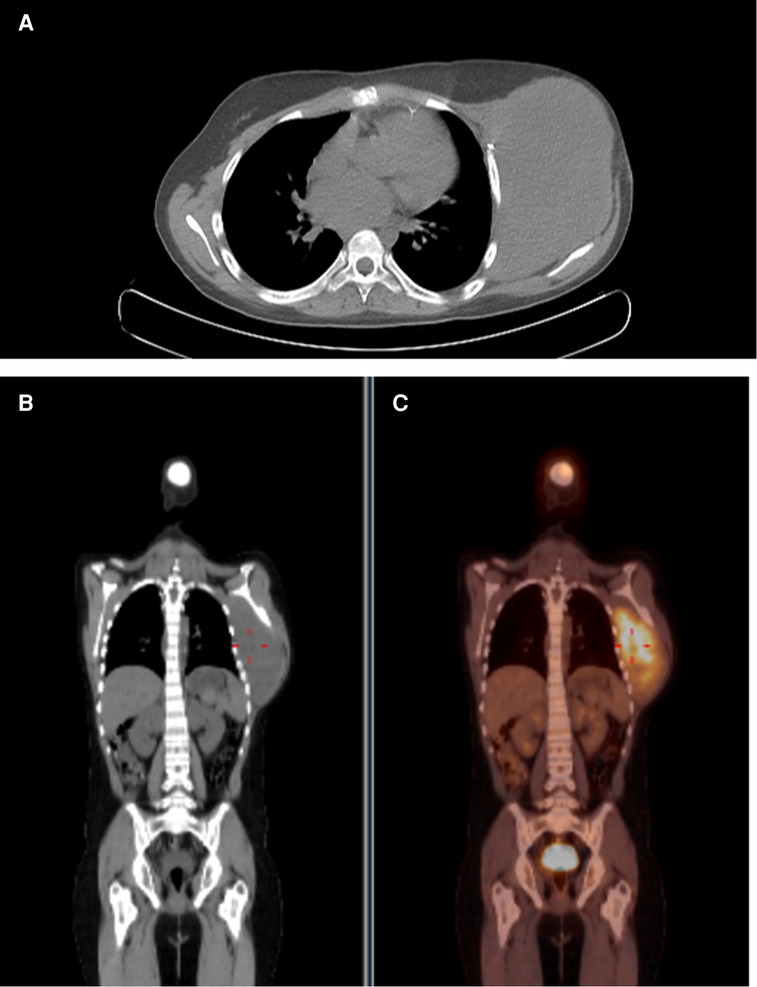

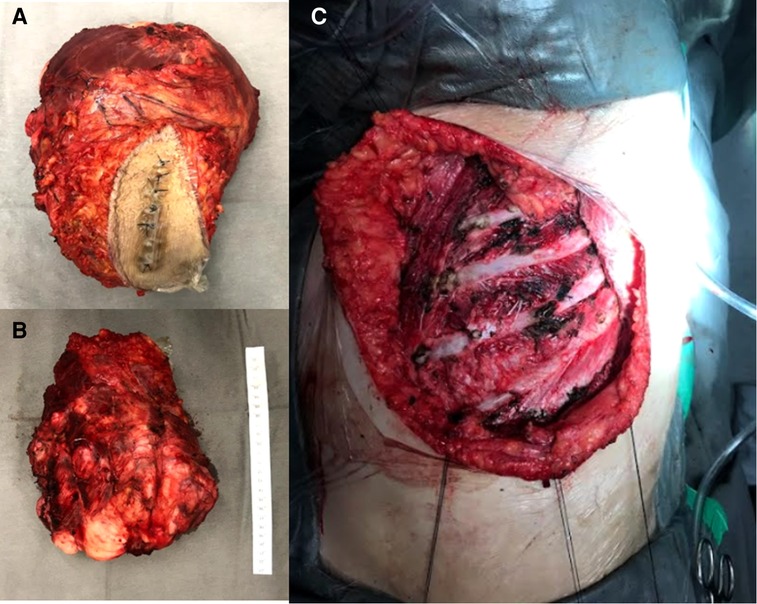

However, there was a progression of the lesion. A PET-CT was performed with the finding of an important uptake lesion at the thoracic wall with SUVmax 7.8. The lesion was biopsied with the anatomopathological diagnosis of a DT. Resection surgery happened 4 months after the start of the mass growth (Figure 1). At that time, the tumour reached 20 cm in diameter. The lesion infiltrated the pectoralis major muscle and microscopically did not invade the intercostal muscles or ribs. The pectoralis major partially was resected en bloc with the lesion (Figure 2). The defect had primary closure. The patient evolved without postoperative complications and was discharged on the 14th postoperative day.

Figure 1. Preoperative PET image. Captant area in thoracic wall with SUVmax: 7.8. (A) Axial image. (B) Coronal image. (C) Coronal fusion image.

Figure 2. Intraoperative images. (A) Superficial side from the specimen. (B) Profound margem. (C) Resected area.

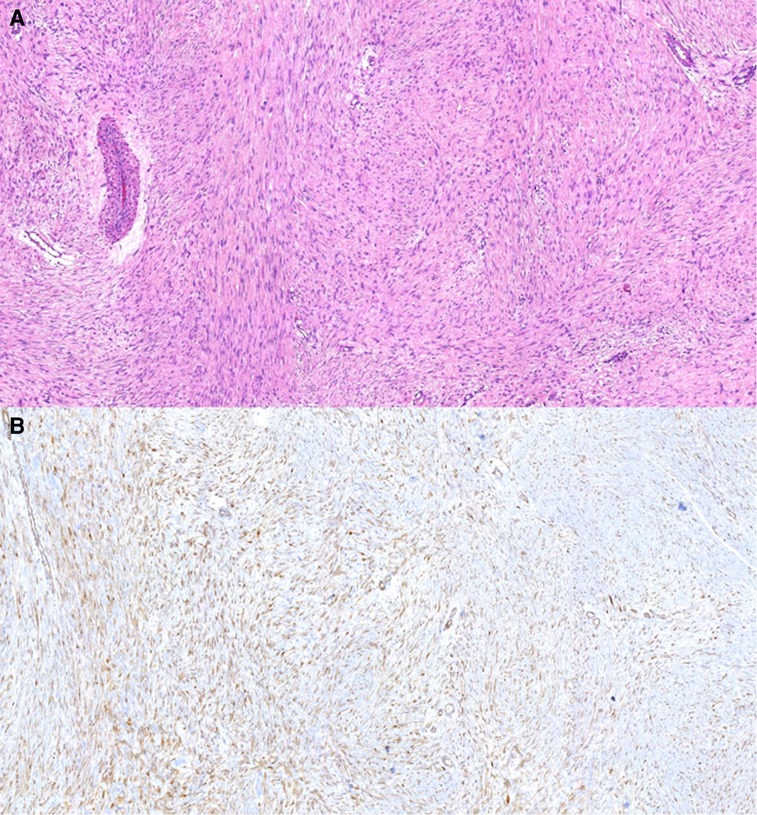

The report from the surgical specimen confirmed that the lesion was a DT (Figure 3). The circumferential margins were negative. The profound margin was microscopically positive. Due to margin compromising, the patient received adjuvant 60 Gray radiotherapy administration 2 months after surgery. There is no evidence of tumour recurrence in a 4-year follow-up.

Figure 3. Pathological findings of the resected specimen. The tumour cells (fibroblasts and myofibroblasts) lack cytological atypia, form long, “sweeping” fascicles, and show nuclear beta-catenin expression. These findings are consistent with desmoid fibromatosis. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin, 100×. (B) Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin, 100×.

DT is associated with mutations in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the majority of cases. There is a hereditary type of disease with germline mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) being part of the familial adenomatous polyposis. There are also sporadic mutations related to DT (2). In the paediatric population, DT is associated with more gene mutations and a higher gene mutation rate than in adult cases, described in the literature the mutation rate of three exons of CTTNNB1 (3). DT can be related to local trauma, and surgery is associated with 28% of DT cases (4). In this case report, DT appeared at the surgical site of a resynchronization device implant, which is a previous site of surgical trauma.

In one study with 192 included patients with DT, 11% of the sample was paediatric. In this subgroup, the median age is 15 years, with female predominance of 64%. The median tumour size was 5.3 cm. In children, all tumour sites were extra-abdominal. Lesions were predominant in the extremities, and only 15% were in the trunk (2).

There is no report of DT after a heart transplant in the literature. There are reports of DT in patients with lung, liver, and renal recipients (5). Transplant patients are at higher risk for developing tumours due to immunosuppressive therapy, particularly non-melanoma skin cancer and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (6). In the literature, 12.1% of heart post-transplant patients had malignancies diagnosed, and in this population, post-transplant lymphoproliferative diseases were the most common (7).

Once a growing mass develops, it should trigger an investigation. DT is diagnosed by an anatomopathological study of the lesion. Active surveillance is the initial approach to DT for asymptomatic patients (1). The unpredictable course of DT can justify this. Moreover, there is no difference in event-free survival between active surveillance and surgery (1). If there is a growing lesion, active treatment (with medical treatment and/or surgery) should be considered (1).

There are some considerations for surgery management. Between R0 and R1, there is no difference in the recurrence outcome. R1 resection is acceptable when the functionality is an issue (1). Based on the same outcome from R0 and R1 surgery, in the paediatric populations that are still at a time of physiological growth, sparing of structures should be considered and the decision is performed after multidisciplinary discussion.

Radiotherapy seems an adjuvant approach for DT, especially after R1 resection. However, the difference between surgery and surgery plus radiotherapy is not statistically significant (1).

DT has a high recurrence rate (24%–76%), despite the 10-year overall survival rate being higher than 90% (8). In paediatric heart transplants, post-operatory survival is 13.1 years for those more than 11 years of age at transplant (9). Long-term survival after transplant or DT justifies intervention in this case.

New lesions after transplantation require investigation and diagnosis, considering immunosuppression. DT is a rare aetiology; however, this disease consists of differential diagnoses for growing lesions. Regarding the heart transplant, there is a good outcome in post-operatory survival, which justifies the treatment of DT. Paediatric patients also have the particularity of developing tissues, and this should be taken into account to decide the therapeutic approach.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Heart Institute of the School of Medicine, University of Sao Paulo. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

OF and ESN designed the study and edited the manuscript. OF, ESN, and EA cared for the patient and contributed sample collection. OF, ESN, EA, AJ, MJ, and PF revised the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Desmoid Tumor Working Group. The management of desmoid tumours: a joint global consensus-based guideline approach for adult and paediatric patients. Eur J Cancer. (2020) 127:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.013

2. Trautmann M, Rehkämper J, Gevensleben H, Becker J, Wardelmann E, Hartmann W, et al. Novel pathogenic alterations in pediatric and adult desmoid-type fibromatosis: a systematic analysis of 204 cases. Sci Rep. (2020) 10(1):3368. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60237-6

3. Ning B, Jian N, Ma R. Clinical prognostic factors for pediatric extra-abdominal desmoid tumor: analyses of 66 patients at a single institution. World J Surg Oncol. (2018) 16(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1536-x

4. Lopez R, Kemalyan N, Moseley HS, Dennis D, Vetto RM. Problems in diagnosis and management of desmoid tumors. Am J Surg. (1990) 159(5):450–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81243-7

5. Fahrenkopf MP, Kelpin JP, Murphy ET, Komorowska Timek E. Chest wall desmoid tumor after double lung transplantation. Ann Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2019) 2(1):1–5. doi: 10.35841/cardiovascular-surgery.2.1.1-5

6. Acuna SA. Etiology of increased cancer incidence after solid organ transplantation. Transplant Rev. (2018) 32(4):218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2018.07.001

7. Chen PL, Chang HH, Chen IM, Lai ST, Shih CC, Weng ZC, et al. Malignancy after heart transplantation. J Chin Med Assoc. (2009) 72(11):588–93. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70434-4

8. Fortunati D, Kaplan J, López Martí J, Ponzone A, Innocenti S, Fiscina S, et al. Desmoid-type fibromatosis in children. Clinical features, treatment response, and long-term follow-up. Medicina. (2020) 80(5):495–504. PMID: 33048794

Keywords: paediatric heart transplantation, desmoid tumour, pacemaker, chest wall tumour, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

Citation: Freitas Filho Orival de, Nakahira ES, Schmidt Junior AF, Azeka E, Jatene MB and Pego-Fernardes PM (2022) Desmoid tumour of the chest wall in paediatric post-operatory of heart transplant. Front. Pediatr. 10:860394. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.860394

Received: 22 January 2022; Accepted: 12 October 2022;

Published: 28 November 2022.

Edited by:

Inga Voges, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, GermanyReviewed by:

Erkki Juhani Tukiainen, University of Helsinki, Finland© 2022 Freitas Filho, Nakahira, Schmidt Junior, Azeka, Jatene and Pego-Fernardes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Orival de Freitas Filho b3JpdmFsLmZyZWl0YXNAaGMuZm0udXNwLmJy

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Pediatric Cardiology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.