- 1Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the SickKids Research and Learning Institutes, The Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Paediatrics and the Wilson Centre, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the SickKids Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Paediatrics and Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3SickKids Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Clinical Dietetics, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 6The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 7SickKids Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Background: Engaging patients and families as research partners increases the relevance, quality, and impact of child health research. However, those interested in research engagement may feel underequipped to meaningfully partner. We sought to co-develop an online learning (e-learning) module, “Research 101,” to support capacity-development in patient-oriented child health research amongst patients and families.

Methods: Module co-development was co-led by a parent and researcher, with guidance from a diverse, multi-stakeholder steering committee. A mixed-methods usability testing approach, with three iterative cycles of semi-structured interviews, observations, and questionnaires, was used to refine and evaluate the e-learning module. Module feedback was collected during testing and a post-module interview, and with the validated System Usability Scale (SUS), and satisfaction, knowledge, and self-efficacy questionnaires. Transcripts and field notes were analyzed through team discussion and thematic coding to inform module revisions.

Results: Thirty participants fully tested Research 101, and another 15 completed confirmatory usability testing (32 caregivers, 6 patients, and 7 clinician-researchers). Module modifications pertaining to learner-centered design, content, aesthetic design, and learner experience were made in each cycle. SUS scores indicated the overall usability of the final version was “excellent.” Participants' knowledge of patient-oriented research and self-efficacy to engage in research improved significantly after completing Research 101 (p < 0.01).

Conclusions: Co-development and usability testing facilitated the creation of an engaging and effective resource to support the scaling up of patient-oriented child health research capacity. The methods and findings of this study may help guide the integration of co-development and usability testing in creating similar resources.

Introduction

Patient engagement in health research, currently a dominant discourse in North America (1, 2) and around the world (3), refers to the involvement of patients and communities as equal research partners, as opposed to participants, in the design and conduct of research. Patient-oriented research in Canada is defined as research that engages patients as equal partners, focuses on patient-identified priorities, and aims to improve patient outcomes (1). There is growing evidence that patient engagement in research encourages equity, improves outcome selection, facilitates participant recruitment and retention, increases the quality, credibility, and applicability of evidence, and facilitates knowledge translation (4–7). In pediatrics, partnering with children and their caregivers in research aligns with the principles of child and family-centered care (8) and can leverage rich insights and expertise about child health that may not otherwise be captured (9–11). For engagement to be successful, training for all stakeholders, based on best practices in education pedagogy, is recommended (5, 12, 13). In particular, patients and families require the knowledge and skills to be authentic research partners, and researchers and healthcare professionals must appreciate the added value of patient partners and understand how to collaborate effectively (14, 15).

Insufficient preparation and training are associated with patient and family partners feeling unable to contribute (16–19), lacking an understanding of research methodology and associated technical language (17, 20–22), and misunderstanding their role (21, 23–25). In the context of research involving adults, patient partners reported improved knowledge of research (24, 26–28) and study content (26, 29) after training. However, training resources and empirical work describing their development and effectiveness are limited. A survey of young persons' advisory groups from 7 countries identified a dearth of appropriate training materials as a major barrier to engagement (30).

To address the need for pediatric-specific education, we created the Patient-Oriented Research Curriculum in Child Health (PORCCH), an open-access online curriculum with specialized modules for different stakeholder groups. The goal of PORCCH is to build capacity in patient-oriented child health research and support meaningful and authentic patient (and other stakeholder) partnership in health research (31). Online learning (e-learning) has several advantages, including wide dissemination, remote and asynchronous learning, and flexibility for learners to customize their education (32–35). Central to the quality and evaluation of e-learning materials is their usability, which refers to the effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction with which users can achieve a specific set of tasks in a particular environment (36). The PORCCH curriculum was co-developed through a sharing of power and responsibility across all stages between clinicians, researchers, patients and families, and other stakeholders. This level of engagement is equivalent to what INVOLVE in the United Kingdom and the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) refer to as co-production and collaboration, respectively (37, 38). The aims of this study were to (1) co-develop, “Research 101,” the PORCCH module intended to strengthen capacity in patient-oriented child health research among patients and families and other stakeholders without a formal background in research, (2) refine module content through iterative usability testing, and (3) evaluate the impact of the module on self-efficacy and knowledge. The PORCCH curriculum also includes two additional modules, namely “Patient Engagement 101” that focuses on engaging patients and families in health research and “Research Ethics 101,” which focuses on general principles of research ethics and ethical issues specific to patient-oriented research.

Methods

Co-development of Research 101

The Ontario Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) SUPPORT Unit—part of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research—put out a call in 2016 for novel online training materials to build capacity in patient-oriented research. Given the dearth of child-focused online curricula on patient-oriented research, a collaborative group of clinicians, researchers, and parents submitted a successful application to this competition for the development of PORCCH. The collaborative group was multi-disciplinary and multi-site, with experience and expertise in child health.

A PORCCH steering committee, comprising two clinician-researchers, two SPOR SUPPORT Unit leads, three parent partners (one recruited from a SPOR research network and two from a hospital family advisory committee), a knowledge translation expert, an educational researcher, and two instructional design experts, was formed to provide support, advice, and guidance to the module co-leads. The parent partners on the steering committee all had lived experience with a child with a long-term health condition. In line with SPOR's guiding principles for patient engagement, a collaborative process was maintained throughout module co-development, whereby all partners worked together from the start to identify educational needs, set objectives, and co-develop the module in a manner that acknowledged and valued each other's expertise and experiential knowledge (14).

Co-development of Research 101 was co-led in equal partnership by a parent (AK) and researcher (CM). The principal aim guiding module co-development was to meet the training needs of stakeholders unfamiliar with health research. The initial process involved bringing together patients and families, clinicians, researchers, and knowledge translation experts from multiple pediatric centers in a series of in-person community consultations to identify relevant health research concepts and content to be included in the module. Next, module co-leads were responsible for collating and reviewing the relevant patient-oriented research literature and pertinent content identified through initial consultations with key stakeholders. This was then reviewed in collaboration with the steering committee to inform module content.

To plan out the module, a storyboard was created, which was iteratively reviewed by the steering committee and revised by the module co-leads six times over 9 months. After the storyboard was finalized, a module prototype was programmed using Storyline 360 (Articulate Global Inc., New York). The prototype was created in accordance with Mayer's principles of multimedia design (39) and best practices in plain language writing, including short sentences, simple words, identification of all acronyms, positive tone, active writing style, and large text (40). Additionally, the readability of the module was targeted at a grade 6 reading level and content was designed to meet the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 Level AA requirements (e.g., captions, minimum visual contrast ratio) designed to ensure web-based content is perceivable, understandable, navigable, and interactive (41). As before, module prototypes were internally reviewed and approved by the steering committee. Module co-leads met monthly in person to discuss, draft, and revise module content and layout. Over a 6-month period, the steering committee met three times with the co-leads to discuss and provide feedback on module content and design. The module co-development process is outlined in Supplementary Appendix 1.

This process culminated in an e-learning module prototype, “Research 101,” that is delivered in two thirty-minute parts. Part 1, “What is Health Research and Who is Involved?” defines patient-oriented research and describes the value of patient engagement in research, the “key players” in health research, and the difference between research participation and research partnership. Part 2, “Timeline of a Research Study,” covers the key phases of a health research study, the impact, challenges, and benefits of patient-oriented research, and how patients and families can engage as partners. Both Parts include interactive tools, video vignettes, assessment exercises, certificates of completion, and links to additional resources for further learning.

Refinement and Evaluation of Research 101

A mixed-methods usability testing approach, with three iterative cycles of semi-structured interviews and observations, along with satisfaction, knowledge, and self-efficacy questionnaires, was used to refine and evaluate the e-learning module prototype. This user-centered design approach, which has been used previously for usability testing of online patient education and electronic healthcare apps (32, 42), is an iterative process of implementing a design, learning from discussion and thematic analysis of feedback, and making subsequent design refinements (43). The study was approved by the SickKids Research Ethics Board. This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) reporting checklist (44).

Participants

English-speaking patients (10–18 years), caregivers of pediatric patients, and child health clinician-researchers were recruited across Canada via email and electronic newsletters from family advisory networks, SPOR SUPPORT Units, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program, and CHILD-BRIGHT. Patients and caregivers, the module's intended end-users, were predominantly recruited as well as a smaller proportion of clinician-researchers, since they work directly with patients and families and may thus provide additional knowledge and perspectives on relevant training needs and issues in patient-oriented research. Individuals who expressed interest in participating were contacted by a research assistant who explained the purpose of the study and answered any questions. Participants were excluded if they had any cognitive, perceptual, or motor limitations that could restrict their ability to explore and interact with the module. Usability testing was conducted with different participants in each round to increase the diversity of perspectives sampled. A maximum variation purposive sampling approach was used to ensure the sample included individuals with diverse perspectives, specifically with respect to a wide range of familiarity with patient-oriented research and variability with respect to education level and geographic location (45, 46). Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants, and assent, or a child's verbal agreement to participate, was provided by all patient participants, in addition to consent from a legal guardian. Participants were compensated for their time with a $25 gift card (47).

Usability Testing

Audiotaped usability testing sessions were carried out between November 2018 and January 2020 by a research assistant (VC). Testing took place either in-person at an academic children's hospital or over the phone, according to participant preference and geographic location. Participants first completed a baseline questionnaire to collect demographic information (Supplementary Appendix 2). They then received brief instructions about the usability testing protocol. They were asked to “think aloud” as they completed the module, commenting on what they liked and disliked, any difficulties they encountered, and questions that arose. To facilitate “loud thought,” participants were asked questions to elicit their understanding of various aspects of the module (e.g., “What is the module asking you to do at this point?”) and to solicit participants' suggestions for improvement (Supplementary Appendix 3). Field notes pertaining to usability and any technical problems encountered were also recorded.

Immediately after completion of Research 101, participants engaged in a one-on-one, semi-structured interview, comprising a series of standardized open-ended questions regarding the module's usability (Supplementary Appendix 4). Probing questions were used to elicit further details. Participants were then asked to complete an e-learning satisfaction questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix 5), which our group developed and used in a similar study (32), as well as the System Usability Scale (SUS), a validated questionnaire for evaluating user satisfaction of technologies (48). The SUS contains 10 statements scored on a five-point strength of agreement scale. Raw scores are adjusted to account for positively and negatively oriented questions, and total SUS scores range from 0 to 100, with associated adjectives from “worst imaginable” to “best imaginable,” respectively (48).

Following the first testing cycle, the module prototype was refined through thematic analysis of the usability testing interviews, field notes, and questionnaires. A second usability testing cycle was then conducted to garner further recommendations for potential changes to the online curriculum. Because of a programming error unintentionally introduced in cycle 2, a third round of confirmatory usability testing, comprising only the quantitative evaluations, was conducted to confirm that all issues related to the error were resolved.

Evaluation of Impact (Knowledge and Self-Efficacy)

To evaluate the impact of the e-learning module on users' self-efficacy, participants completed a questionnaire—developed based on Bandura's framework for constructing self-efficacy scales—before and after viewing the module (Supplementary Appendix 6) (49). Participants also completed a multiple-choice test to measure their baseline understanding of research (Supplementary Appendix 7) and rated their pre-module knowledge of patient-oriented research using a five-point Likert scale. The knowledge test was designed to assess the “knows how” level of Miller's pyramid (50) and was pilot tested on 6 individuals (3 patients/families, 3 researchers/clinicians/trainees) to ensure clarity and readability. After module completion, the knowledge test and self-rating were re-administered to determine knowledge acquisition.

Sample Size

A sample size of 15 participants per usability testing cycle was selected; a sample size considered adequate from a usability testing perspective to ensure thematic saturation (51, 52).

Data Analysis

Usability Testing

Audiotaped usability testing sessions and post-module interviews were transcribed verbatim, de-identified, and imported into Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants; Los Angeles, California), a mixed-methods data analysis program, to facilitate data organization and analysis. Coding was both deductive, with published usability attributes (53–56) informing development of an initial coding scheme, and inductive, to allow other codes not initially anticipated to emerge. After each usability cycle, two coders (GAM, AQHC) individually read the transcripts and field notes to identify preliminary codes with regard to usability (e.g., satisfaction, efficiency, learnability, errors) and then refined them through systematic iterative coding and sorting using the constant comparison method (57, 58). Codes were then grouped into usability-related themes and subthemes (59), using published frameworks from the usability literature (53, 60–62) and a previous e-learning usability study (32) as sensitizing concepts. The final coding framework, presented in Supplementary Appendix 8, was then applied to all transcripts. Disagreements or uncertainties between coders were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third coder (CMW). The study team met regularly to discuss and refine the evolving themes and coding framework, and used their expertise in education, child health, and research to help clarify and critique the findings. Thematic saturation was monitored through the number and novelty of the usability issues raised by subsequent testers, both within and across usability testing cycles (58). To enhance trustworthiness of the findings (63), reflexivity was employed and the team, including parents, clinicians, and non-clinician researchers, questioned and challenged each other's assumptions throughout the analysis. This process, which enabled critical reflection, examination, and exploration of the research process from different positions, informed the team's reflections on patient engagement.

Evaluation of Impact (Knowledge and Self-Efficacy)

Data from the demographic, satisfaction, self-efficacy, and knowledge questionnaires were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and with counts and proportions for discrete variables.

Pre-post changes in self-efficacy and knowledge were evaluated with paired t-tests (α = 0.05, two-sided). Quantitative analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.0 (R Core Team; Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant Characteristics

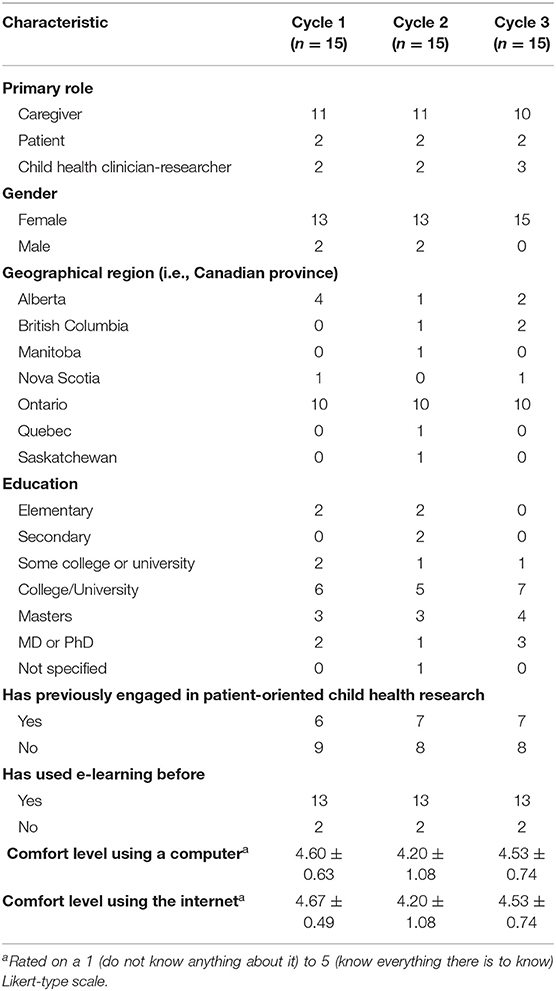

Thirty-two caregivers, 6 patients, and 7 child health clinician-researchers participated (15 in each round), more than half of whom had not previously engaged in patient-oriented child health research. Participant characteristics for each usability round are shown in Table 1. Module completion time (±SD) was similar between usability cycles, with a mean duration of 58 ± 10 min in cycle 1, and 62 ± 17 min in cycle 2.

Research 101 E-Learning Module Usability

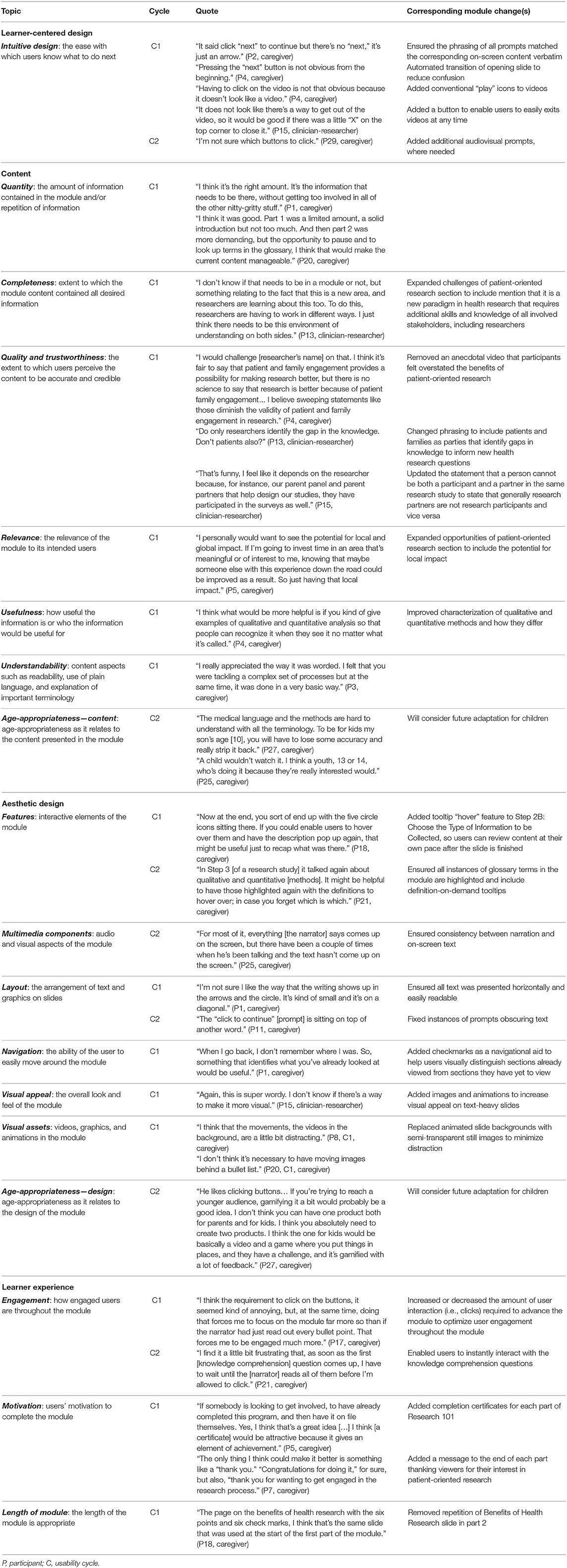

Qualitative analysis of usability testing sessions, used to inform iterative module refinements, centered around four themes: (1) learner-centered design, (2) content, (3) aesthetic design, and (4) learner experience. Themes were consistent across patients, caregivers, and clinician-researchers. All four themes were prevalent in cycle 1, leading to relatively major content and design revisions, whereas aesthetic design and relatively minor changes to ensure consistency in the presentation of the module predominated in cycle 2. Illustrative quotes for each theme and corresponding module changes are described below, with additional quotes and changes in Table 2.

Learner-Centered Design

Learner-centered design was divided into subthemes of ease of use, intuitive design, and learnability. Participants described Research 101 as very user-friendly, and most quickly learned how to use the navigational and audio controls. However, in cycle 1 many did not discover the module's interactive features until Part 2. For example:

“I didn't pick up the first time, in Part 1, that the [interactive] menu actually contained an outline of the entire [module].” (participant (P) 3, cycle (C) 1, caregiver)

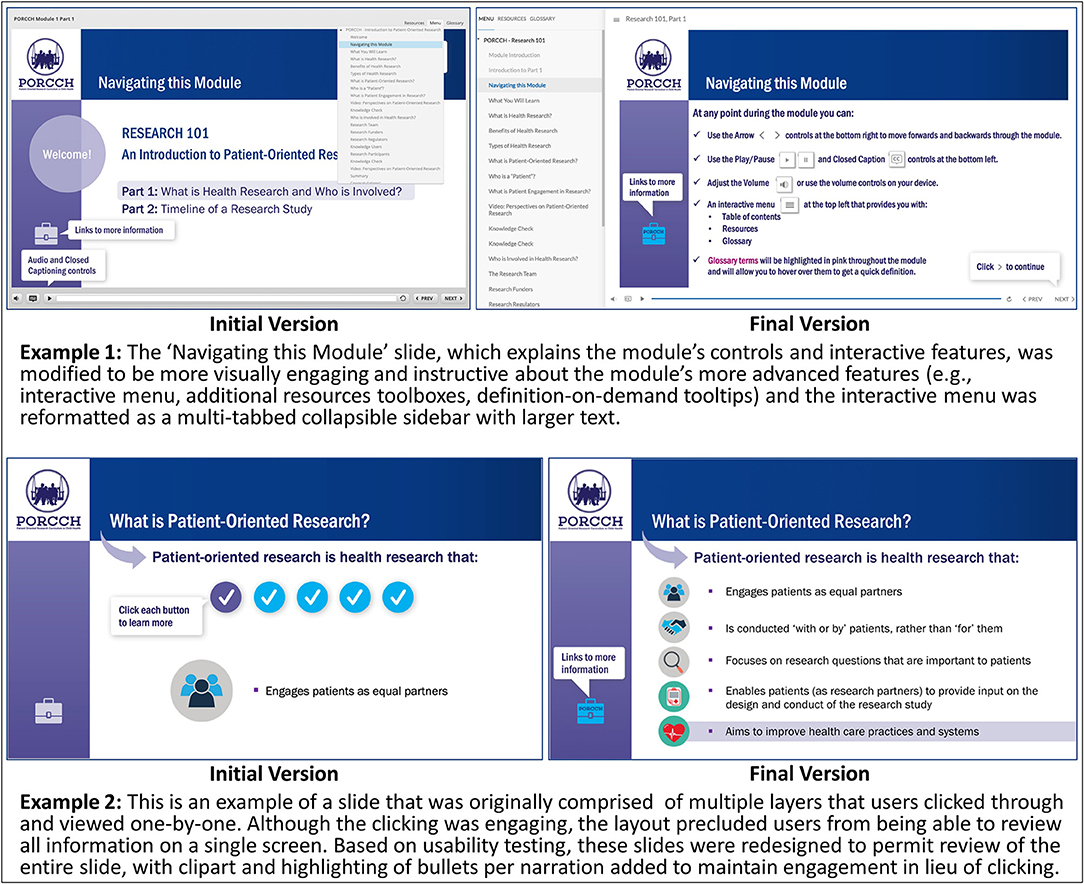

To make these features more salient, the “Navigating this Module” slide was redesigned to be more attention-grabbing and informative (Figure 1). In addition, participants in cycle 1 found the interactive menu, which was originally formatted as a click dropdown list, difficult to use, as the text was small, and the menu was susceptible to clicking errors. To overcome these issues, the interactive menu was reformatted as a multi-tabbed collapsible sidebar with larger text.

Content

Content was evaluated in terms of quantity, completeness, quality and trustworthiness, relevance, usefulness, understandability, and age-appropriateness. Participants across both usability cycles found the information presented in the module to be useful, relevant, and trustworthy:

“I think it does a really good job of two things: encouraging patients and families to get involved because it's emphasizing all the benefits, but it's also being fair about the pitfalls and that there is great potential for delays. So, I thought that was well-balanced.” (P3, C1, caregiver)

Based on feedback in cycle 1, a new slide on potential solutions to the challenges of patient-oriented research was added and positively received by participants in cycle 2. Module sections with poor understandability, because they were too technical, contained undefined terms or concepts, or were considered beyond the scope of an introductory module, were identified in both cycles. To address these issues, instances of jargon were replaced with more common language; key terminology (e.g., authentic partnership) was defined in the glossary; and less relevant sections (e.g., primary versus secondary outcomes) were removed.

Aesthetic Design

Within the theme of aesthetic design, subthemes included interactive features, multimedia components, layout, navigation, visual appeal, visual assets, and age-appropriateness. Although participants appreciated having the glossary, some participants in cycle 1 expressed concern that navigating to the glossary might be disruptive or disincentivizing to learners:

“I think the glossary might be lost in translation. I don't know if users are going to click again [to open it], so I don't know if it's useful.” (P7, C1, caregiver)

To address this, glossary definitions were added as tooltips (i.e., text boxes that display information when the cursor is hovered nearby) to all key terms in the module, creating a definition-on-demand feature, using a uniquely colored text to indicate the interactivity. Also, some slides were designed with multiple sequential layers. Participants in cycle 1 did not like that this design precluded them from simultaneously reviewing all content on a single screen; therefore, these slides were redesigned (Figure 1).

Participants liked the module's aesthetic, describing it as inviting and professional-looking, although a lack of diversity in the stock images was noted in cycle 1. In response, the image set was updated to better represent the variety of cultures, age groups, and types of intellectual and physical abilities of those involved in patient-oriented child health research, and a video featuring a discussion between a parent partner and a researcher was replaced with a video from a youth's perspective on being a research partner.

Learner Experience

Lastly, learner experience included satisfaction, engagement, memorability, motivation, and length of module. In general, participants in both cycles were highly satisfied with Research 101, finding it engaging and educational:

“It's excellent and I think it's going to be hugely helpful in fast-tracking families who want to get involved in research.” (P4, C1, caregiver)

Most participants regarded the anecdotal videos as the most memorable part of the module. Participants felt the module was an appropriate length but advised that future users consider viewing Parts 1 and 2 spaced apart to maximize focus, engagement, and learning.

Errors

Errors identified during testing included navigation, audio, presentation, and language errors. Several minor module errors were identified in testing and subsequently fixed, including audio tracks not initiating, multiple audio tracks playing simultaneously, and video buffering issues. In cycle 2, a programming error was unintentionally introduced that resulted in several “dead ends” in the module that compromised module usability.

System Usability Scale

SUS scores corresponded to ratings of “good” or better in each round. As expected, scores in cycle 2 (75.17 ± 18.14) were lower than cycle 1 (88.33 ± 9.76), given the aforementioned programming error. Cycle 3 scores (87.17 ± 9.95) were consistent with cycle 1, corresponding to an overall usability rating of “excellent.” SUS scores by usability testing cycle and role are presented in Supplementary Appendix 9.

E-Learning Satisfaction

Overall, learner satisfaction with Research 101 was very high across all 3 cycles (cycle 1: 4.53 ± 0.64; cycle 2: 4.40 ± 0.91; cycle 3: 4.47 ± 0.64), indicating users were generally “very satisfied” with the module. E-learning evaluation results are displayed in Supplementary Appendix 10.

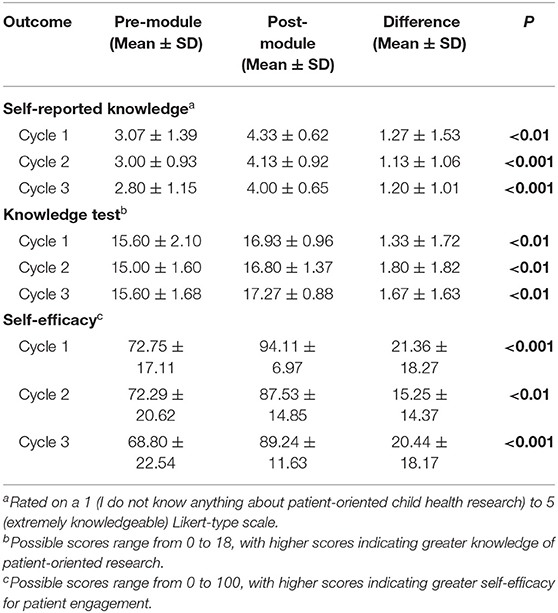

Evaluation of Impact (Knowledge and Self-Efficacy)

In each round, participants' knowledge test scores, self-reported knowledge of patient-oriented research, and self-efficacy to engage in patient-oriented research increased significantly after completing Research 101 (p < 0.01; Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in knowledge of and self-efficacy to engage in patient-oriented research before and after completing Research 101.

Interpretation

This paper describes the co-development and evaluation of an e-learning module, “Research 101,” designed to increase the “patient-oriented child health research readiness” of patients and families and other stakeholders without a formal research background. Research 101 was co-developed at all stages with patients and families so that their perspectives, values, and training needs were captured, and end-user usability testing was employed to maximize the usefulness and quality of the module. In each testing cycle, valuable refinements were identified from qualitative and quantitative module evaluations and subsequently implemented. The overall usability of the final version of Research 101 was “excellent,” and the module was shown to significantly improve participants' knowledge of patient-oriented research and self-efficacy to engage in patient-oriented research. As of December 2021, 1 year after launch, PORCCH has had over 50,000 unique website visitors (www.porcch.ca), with over 350 users enrolled in Research 101.

Capacity-building is a key element of SPOR (13) and other national patient and public involvement frameworks, such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (64) in the United States and INVOLVE in the United Kingdom (12). Training of patient and family partners, however, is often variable (30, 65), and typically provided in-person to prepare partners for a specific project (66, 67). Online resources may be a cost-effective way to scale up patient-oriented research training to build capacity and broaden the dissemination of training materials. For example, the online content of the European Patients' Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) Patient Expert Training Programme is being adapted into a massive open online course (MOOC) format to make it more accessible (68). Another example is KidneyPRO, a web-based training module designed for patients and families to promote patient-oriented kidney research in Canada (69). Although there exists broad consensus that lived experience is the most important quality patient partners bring to a research team, there is disagreement on whether and to what extent patient partners should be “further trained” (15, 70). Patient and family partners should take the lead in determining their training needs within the context of the project, and self-guided resources like Research 101 may be helpful in this regard (15).

Several study limitations should be noted. Although the sample size employed was in accordance with recommendations from the usability testing literature (51, 52), it was too small to assess the impact of participant characteristics on module usability. In addition, the usability testers, who were recruited through established family advisory and pediatric research networks for convenience and their familiarity with patient-oriented research, may not fully represent the intended end-users of Research 101. This is a notable limitation, since design processes that do not meaningfully incorporate the lived experience of underrepresented groups can result in products that create barriers for people with a wide range of abilities and backgrounds (71). Best practice in inclusive, accessible, and diverse design is to design with, rather than for, diverse and often excluded communities (71). The self-report measures employed to evaluate the impact of the module on self-efficacy were selected for pragmatic reasons. Evaluation of longer-term outcomes, such as whether completion of Research 101 is associated with increased or more impactful involvement in research, in a larger and more diverse group of patients and families (e.g., with representation of First Nations and other countries) is needed. Lastly, PORCCH is currently only available in English, although a French translation is underway.

Team Reflections on Patient Engagement

Although the team did not formally collect data to evaluate the process of co-developing Research 101, the team did critically reflect on the processes and outcomes of co-development. General themes that emerged from discussions amongst all team members included the value-add of parent and researcher collaboration, the importance of a broad range of perspectives, the benefits of building relationships and networks, the importance of accessible materials, and the significant time commitment required to ensure authentic partnership. Similar themes have been found in other curriculum-building initiatives (72).

Parents on the steering committee provided valuable input on issues such as accessibility, inclusiveness, and how to achieve authentic and meaningful partnerships. Throughout module testing, they reviewed emerging themes and helped interpret the findings. As noted elsewhere (65, 73), partnering with patients and families was associated with incremental research costs (e.g., compensation for partners) and logistical challenges (e.g., evening meetings to accommodate patient partners). However, the value-add of co-developing the module justified additional budgeting for engagement-related costs. All partners were selected from established children's hospital family advisory networks and were already proficient at collaborating with child health clinicians and researchers. Selection of experienced partners permitted quick initiation of module co-development, but underrepresentation of partners with little or no previous engagement may have contributed in part to an initial module prototype that assumed too much prior knowledge, as revealed by usability testing. To counterbalance this, patients and families with little or no previous engagement were deliberately sought as testers to refine the module and ensure it was targeted appropriately. Having parent and researcher co-leads worked well as perspectives were balanced and the setup provided the parent partner with a dedicated team member for support. The steering committee helped incorporate additional perspectives into the module.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Research 101, part of the open-access online Patient-Oriented Research Curriculum in Child Health (PORCCH; www.porcch.ca), may be of use to a variety of patients and families and other stakeholders looking for an interactive, introductory curriculum on patient-oriented child health research. Additionally, the methods and findings of this study may help inform the integration of co-development and usability testing in creating other capacity-building resources for patient-oriented research.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by SickKids Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by participants, or, where applicable, the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

CW, CM, NJ, and AK: study conception and design. VC and GM: data acquisition. CW, CM, NJ, GM, AK, VC, LP, and AC: analysis, interpretation of data, critical revision, and final manuscript approval. CW, CM, GM, and VC: drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR)—Patient-Oriented Research Collaboration Grant #397481 (matching funds were provided by CHILD-BRIGHT, the BC SUPPORT Unit, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program, the Ontario Child Health SUPPORT Unit, and the SickKids Research Institute). CW holds an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, decision to publish, or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Pathways Training and E-Learning.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.849959/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Canada's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: Improving Health Outcomes Through Evidence-Informed Care. (2011). Available online at: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/44000.html (accessed April 8, 2022).

2. Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, Schrandt S, Frank L. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. (2018) 27:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1581-x

3. Staniszewska S, Denegri S, Matthews R, Minogue V. Reviewing progress in public involvement in NIHR research: developing and implementing a new vision for the future. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e017124. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017124

4. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89

5. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Heal Expect. (2014) 17:637–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x

6. Bird M, Ouellette C, Whitmore C, Li L, Nair K, McGillion MH, et al. Preparing for patient partnership: a scoping review of patient partner engagement and evaluation in research. Health Expect. (2020) 23:523–39. doi: 10.1111/hex.13040

7. Vat LE, Finlay T, Jan Schuitmaker-Warnaar T, Fahy N, Robinson P, Boudes M, et al. Evaluating the “return on patient engagement initiatives” in medicines research and development: a literature review. Health Expect. (2020) 23:5–18. doi: 10.1111/hex.12951

8. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. (2012) 129:394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084

9. Curran JA, Bishop A, Chorney J, MacEachern L, Mackay R. Partnering with parents to advance child health research. Healthc Manag forum. (2018) 31:45–50. doi: 10.1177/0840470417744568

10. Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J. Engaging with children as co-researchers: challenges, counter-challenges and solutions. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2015) 18:161–73. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2013.864589

11. Shen S, Doyle-Thomas KAR, Beesley L, Karmali A, Williams L, Tanel N, et al. How and why should we engage parents as co-researchers in health research? A scoping review of current practices. Heal Expect. (2017) 20:543–54. doi: 10.1111/hex.12490

12. INVOLVE. Developing Training and Support for Public Involvement in Research. (2012). Available online at: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/8774-INVOLVE-Training-Support-WEB2.pdf (accessed April 8, 2022).

13. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: Capacity Development Framework. (2015). Available online at: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49307.html (accessed April 8, 2022).

14. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: Patient Engagement Framework. (2015). Available online at: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html (accessed April 8, 2022).

15. Frisch N, Atherton P, Doyle-Waters MM, MacLeod MLP, Mallidou A, Sheane V, et al. Patient-oriented research competencies in health (PORCH) for researchers, patients, healthcare providers, and decision-makers: results of a scoping review. Res Involv Engagem. (2020) 6:4. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-0180-0

16. Shah SGS, Robinson I, Ghulam S, Shah SGS, Robinson I, Shah SGS, et al. Benefits of and barriers to involving users in medical device technology development and evaluation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2007) 23:131–7. doi: 10.1017/S0266462307051677

17. McCormick S, Brody J, Brown P, Polk R. Public involvement in breast cancer research: an analysis and model for future research. Int J Heal Serv. (2004) 34:625–46. doi: 10.2190/HPXB-9RK8-ETVM-RVEA

18. Rowe A. The effect of involvement in participatory research on parent researchers in a Sure Start programme. Heal Soc Care Community. (2006) 14:465–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00632.x

19. Bryant W, Parsonage J, Tibbs A, Andrews C, Clark J, Franco L. Meeting in the mist: key considerations in a collaborative research partnership with people with mental health issues. Work. (2012) 43:23–31. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1444

20. Morris MC, Nadkarni VM, Ward FR, Nelson RM. Exception from informed consent for pediatric resuscitation research: cardiac arrest. Pediatrics. (2004) 114:776–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0482

21. Oliver S, Milne R, Bradburn J, Buchanan P, Kerridge L, Walley T, et al. Involving consumers in a needs-led research programme: a pilot project. Heal Expect. (2001) 4:18–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00113.x

22. Abma TA. Patient participation in health research: research with and for people with spinal cord injuries. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1310–28. doi: 10.1177/1049732305282382

23. Ong BN, Hooper H. Involving users in low back pain research. Heal Expect. (2003) 6:332–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-7625.2003.00230.x

24. Caldon LJM, Marshall-Cork H, Speed G, Reed MWR, Collins KA. Consumers as researchers - innovative experiences in UK national health service Research. Int J Consum Stud. (2010) 34:547–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00907.x

25. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. (2014) 7:387–95. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0

26. Minogue V, Boness J, Brown A, Girdlestone J. The impact of service user involvement in research. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. (2005) 18:103–12. doi: 10.1108/09526860510588133

27. Plumb M, Price W, Kavanaugh-Lynch MHE. Funding community-based participatory research: lessons learned. J Interprof Care. (2004) 18:428–39. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011792

28. O'Donnell M, Entwistle V. Consumer involvement in decisions about what health-related research is funded. Health Policy. (2004) 70:281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.04.004

29. Ross F, Donovan S, Brearley S, Victor C, Cottee M, Crowther P, et al. Involving older people in research: methodological issues. Heal Soc Care Community. (2005) 13:268–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00560.x

30. Tsang VWL, Chew SY, Junker AK. Facilitators and barriers to the training and maintenance of young persons' advisory groups (YPAGs). Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2020) 7:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.10.002

31. Macarthur C, Walsh CM, Buchanan F, Karoly A, Pires L, McCreath G, et al. Development of the patient-oriented research curriculum in child health (PORCCH). Res Involv Engagem. (2021) 7:27. doi: 10.1186/s40900-021-00276-z

32. Connan V, Marcon MA, Mahmud FH, Assor E, Martincevic I, Bandsma RH, et al. Online education for gluten-free diet teaching: development and usability testing of an e-learning module for children with concurrent celiac disease and type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. (2019) 20:293–303. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12815

33. Stinson J, Wilson R, Gill N, Yamada J, Holt J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. (2009) 34:495–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn115

34. Mulders G, De Wee EM, Vahedi Nikbakht-van de Sande MCVM, Kruip MJHA, Elfrink EJ, Leebeek FWG. E-learning improves knowledge and practical skills in haemophilia patients on home treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Haemophilia. (2012) 18:693–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02786.x

35. De Graaf M, Knol MJ, Totté JEE, Van Os-Medendorp H, Breugem CC, Pasmans SGMA. E-learning enables parents to assess an infantile hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2014) 70:893–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.040

36. Schoeffel R. The concept of product usability. ISO Bull. (2003) 34:6–7. Available online at: https://docbox.etsi.org/stf/Archive/STF285_HF_MobileEservices/STF285%20Work%20area/Setup/Inputs%20to%20consider/ISO20282.pdf

37. INVOLVE. Guidance on Co-Producing a Research Project. (2018). Available online at: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Copro_Guidance_Feb19.pdf (accessed April 8, 2022).

38. International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). Public Participation Spectrum. (2004). Available online at: https://iap2canada.ca/Resources/Documents/0702-Foundations-Spectrum-MW-rev2%20(1).pdf (accessed April 8, 2022).

39. Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning to medical education. Med Educ. (2010) 44:543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03624.x

40. Public Works Government Services Canada. The Canadian Style: Plain Language. (2015). Available online at: https://www.btb.termiumplus.gc.ca/tcdnstyl-chap?lang=eng&lettr=chapsect13&info0=13 (accessed April 8, 2022).

41. World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. (2008). Available online at: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/ (accessed April 8, 2022).

42. Stinson J, Gupta A, Dupuis F, Dick B, Laverdière C, LeMay S, et al. Usability testing of an online self-management program for adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. (2015) 32:70–82. doi: 10.1177/1043454214543021

43. Snodgrass A, Coyne R. Models, metaphors and the hermeneutics of designing. Des Issues. (1992) 9:56–74. doi: 10.2307/1511599

44. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. (2017) 358:j3453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453

45. Lavelle E, Vuk J, Barber C. Twelve tips for getting started using mixed methods in medical education research. Med Teach. (2013) 35:272–6. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.759645

46. Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mix Methods Res. (2007) 1:77–100. doi: 10.1177/1558689806292430

47. TCPS2 TCPS2 Canadian Institutes of Health Research Natural Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council of Canada Social Sciences Humanities Research Council. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. (2018). Available online at: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/documents/tcps2-2018-en-interactive-final.pdf (accessed April 8, 2022).

48. Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Hum Comput Interact. (2008) 24:574–94. doi: 10.1080/10447310802205776

49. Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing (2006). p. 307–37.

50. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. (1990) 65:S63–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045

51. Kushniruk AW, Patel VL. Cognitive and usability engineering methods for the evaluation of clinical information systems. J Biomed Inform. (2004) 37:56–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2004.01.003

52. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. (2018) 52:1893–907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

53. Koohang A, Du Plessis J. Architecting usability properties in the e-learning instructional design process. Int J E-learning. (2004) 3:38–44. Available online at: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/5102/

55. Shackel B. Usability – context, framework, design and evaluation. In: Shackel B, Richardson SJ, editors. Human Factors for Informatics Usability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1991). p. 21–38.

56. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC). ISO/IEC 9126: Software Product Evaluation - Quality Characteristics and Guidelines for Their Use. Geneva: ISO/IEC (1991).

57. Charmaz K. Constructivist grounded theory. J Posit Psychol. (2017) 12:299–300. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262612

58. Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. (2012) 34:850–61. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439

59. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

60. Koohang A, Paliszkiewicz J. E-Learning courseware usability: building a theoretical model. J Comput Inf Syst. (2015) 56:55–61. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2015.11645801

61. Zaharias P Poylymenakou A. Developing a usability evaluation method for e-learning applications: beyond functional usability. Int J Hum-Comput Int. (2009) 25:75–98. doi: 10.1080/10447310802546716

62. Sandars J, Lafferty N. Twelve tips on usability testing to develop effective e-learning in medical education. Med Teach. (2010) 32:956–60. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.507709

63. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

64. Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, Schrandt S, Sheridan S, Gerson J, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. (2015) 24:1033–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3

65. Baxter S, Clowes M, Muir D, Baird W, Broadway-Parkinson A, Bennett C. Supporting public involvement in interview and other panels: a systematic review. Health Expect. (2017) 20:807–17. doi: 10.1111/hex.12491

66. Parkes JH, Pyer M, Wray P, Taylor J. Partners in projects: preparing for public involvement in health and social care research. Health Policy. (2014) 117:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.04.014

67. McGlade A, Taylor BJ, Killick C, Lyttle E, Patton S, Templeton F. Developing service user skills in co-production of research: course development and evaluation. J evidence-based Soc Work. (2020) 17:486–502. doi: 10.1080/26408066.2020.1766622

68. van Rensen A, Voogdt-Pruis HR, Vroonland E. The launch of the European Patients' Academy on Therapeutic Innovation in the Netherlands: a qualitative multi-stakeholder analysis. Front Med. (2020) 7:558. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00558

69. Getchell L, Bernstein E, Fowler E, Franson L, Reich M, Sparkes D, et al. Program report: KidneyPRO, a web-based training module for patient engagement in kidney research. Can J Kidney Heal Dis. (2020) 7:2054358120979255. doi: 10.1177/2054358120979255

70. Dudley L, Gamble C, Allam A, Bell P, Buck D, Goodare H, et al. A little more conversation please? Qualitative study of researchers' and patients' interview accounts of training for patient and public involvement in clinical trials. Trials. (2015) 16:190. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0667-4

71. Microsoft. Inclusive Design Toolkit Manual. (2016). Available online at: https://download.microsoft.com/download/b/0/d/b0d4bf87-09ce-4417-8f28-d60703d672ed/inclusive_toolkit_manual_final.pdf (accessed April 8, 2022).

72. Bell T, Vat LE, McGavin C, Keller M, Getchell L, Rychtera A, et al. Co-building a patient-oriented research curriculum in Canada. Res Involv Engagem. (2019) 5:7. doi: 10.1186/s40900-019-0141-7

Keywords: patient-oriented research, patient engagement, capacity development, child health research, online education

Citation: Walsh CM, Jones NL, McCreath GA, Connan V, Pires L, Chen AQH, Karoly A and Macarthur C (2022) Co-development and Usability Testing of Research 101: A Patient-Oriented Research Curriculum in Child Health (PORCCH) E-Learning Module for Patients and Families. Front. Pediatr. 10:849959. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.849959

Received: 06 January 2022; Accepted: 27 April 2022;

Published: 06 July 2022.

Edited by:

Anping Xie, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jean-Christophe Bélisle-Pipon, Simon Fraser University, CanadaAbigail Wooldridge, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States

Katharina Kovacs Burns, University of Alberta, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Walsh, Jones, McCreath, Connan, Pires, Chen, Karoly and Macarthur. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catharine M. Walsh, Y2F0aGFyaW5lLndhbHNoQHV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Catharine M. Walsh

Catharine M. Walsh Nicola L. Jones

Nicola L. Jones Graham A. McCreath

Graham A. McCreath Veronik Connan4

Veronik Connan4 Colin Macarthur

Colin Macarthur